Dixit v40

january – december 2026

10.22235/d.v40.4696

Research articles

Institutional Online Communication and Civic Participation in Education Policy: A Literature Review

Comunicación institucional en línea y participación cívica en las políticas educativas: revisión de literatura

Comunicação institucional online e participação cívica nas políticas educativas: revisão de literatura

Mihaela Luminița Sandu1 ORCID: 0009-0003-7531-2738

Tănase Tasențe2 ORCID: 0000-0002-3164-5894

1 Ovidius University of Constanța, Romania

2 Ovidius University of Constanța, Romania, [email protected]

Abstract:

This article offers a comprehensive review of

scholarly literature on the relationship between online institutional

communication and civic participation in education-related public policy.

Drawing on 20 peer-reviewed studies published between 2010 and 2024, it

identifies four thematic pillars: transparency and accountability; opportunities

and inequalities in social-media participation; pedagogies for critical digital

citizenship; and inclusive, arts-based or peer-led models of civic activation.

Evidence from Romania, Indonesia, Spain, and South Africa shows that digital

transparency improves access to information but does not guarantee meaningful

engagement unless institutions adopt dialogic, value-driven communication

practices. The article proposes a conceptual model linking communication

styles, digital affordances, and pedagogical interventions to distinct forms of

civic participation.

Keywords: mass communication; educational policy; information technology; social media; communication policy.

Resumen:

Este artículo presenta una revisión amplia de la

literatura académica sobre la relación entre la comunicación institucional en

línea y la participación cívica en las políticas públicas educativas. Basado en

20 estudios revisados por pares publicados entre 2010 y 2024, identifica cuatro

ejes: transparencia y rendición de cuentas; oportunidades y desigualdades de

participación en redes sociales; pedagogías para una ciudadanía digital

crítica; y modelos inclusivos de activación cívica basados en las artes o el

liderazgo entre pares. La evidencia de Rumania, Indonesia, España y Sudáfrica

muestra que la transparencia digital facilita el acceso a la información, pero

no asegura una participación significativa sin prácticas comunicativas

dialógicas y orientadas por valores. El artículo propone un modelo conceptual

que vincula estilos comunicativos, características digitales e intervenciones

pedagógicas con diversas formas de participación cívica.

Palabras clave: comunicación masiva; política educativa; tecnología de la información; redes sociales; política de comunicación.

Resumo:

Este artigo apresenta uma ampla revisão da

literatura acadêmica sobre a relação entre a comunicação institucional online e

a participação cívica nas políticas públicas educativas. Com base em 20 estudos

revisados por pares publicados entre 2010 e 2024, ele identifica quatro eixos:

transparência e prestação de contas; oportunidades e desigualdades de

participação nas redes sociais; pedagogias para uma cidadania digital crítica;

e modelos inclusivos de ativação cívica baseados nas artes ou na liderança entre

pares. Evidências da Romênia, Indonésia, Espanha e África do Sul mostram que a

transparência digital facilita o acesso à informação, mas não garante uma

participação significativa sem práticas comunicativas dialógicas e orientadas

por valores. O artigo propõe um modelo conceitual que vincula estilos

comunicativos, características digitais e intervenções pedagógicas a diversas

formas de participação cívica.

Palavras-chave: comunicação de massa; política educacional; tecnologia da informação; redes sociais; política de comunicação.

Received: 06/26/2025

Revised: 10/01/2025

Accepted: 11/06/2025

Introduction

The promise that digital communication could democratize public decision-making has deep theoretical roots. Early scholarship on e-government argued that the informational affordances of the Internet reduce monitoring costs, expand the public sphere, and level the participatory playing field for traditionally under-represented groups (Chadwick, 2013). Subsequent work on social media has extended these claims, positing that the horizontal architecture, low entry barriers, and algorithmic connectivity of platforms such as Facebook and Twitter can amplify peripheral voices, create “accidental” exposure to political information (Valeriani & Vaccari, 2016), and thus reduce inequalities in civic engagement. In parallel, research on open government data (OGD) proposed that the release of machine-readable public datasets might enable citizens to track spending, detect corruption, or design innovative public-interest applications (Purwanto et al., 2020). However, optimism was tempered by concerns that digital divides in access, skills and motivation might reproduce existing disparities (Norris, 2001); that institutions would use social media primarily for self-presentation rather than genuine deliberation (Mergel, 2015); and that algorithmic curation could lead to echo-chambers, disinformation and new forms of exclusion (Sunstein, 2018).

The relationship between digital communication and democracy has been increasingly problematized in recent scholarships, especially in light of algorithmic mediation and the rise of artificial intelligence. Recent studies emphasize that online platforms operated by public institutions can foster transparency and accountability but also generate new forms of polarization and exclusion if not properly regulated (Zhuravskaya et al., 2020). At the same time, scholars highlight how algorithmic filtering and AI-driven tools reshape civic engagement, influencing not only the visibility of political content but also the modes of participation available to citizens (Vaccari & Valeriani, 2021). More recent research underlines the dual role of AI in democratic communication: it can enhance participation and deliberation through automated consultation systems, but it also poses risks of surveillance, manipulation, and inequality in access (Sieber et al., 2025). In this sense, institutional online communication in the era of AI requires both normative frameworks and innovative practices that align technological opportunities with democratic values.

Education policy offers a powerful lens for understanding how digital media reshape civic engagement. Schools are not just places of learning, they are central to shaping collective values and democratic participation (Hoskins & Janmaat, 2019; Campbell & Niemi, 2016). In today’s digital context, students, parents, and teachers can more easily express concerns, influence decisions, and hold institutions accountable. The COVID-19 pandemic made these dynamics especially visible, as debates over school closures and remote learning highlighted the need for clear, responsive, and trustworthy communication. Ministries had to manage public expectations while navigating uncertainty, and families turned to online platforms for information, support, and advocacy. These fast-moving interactions have transformed the relationship between education and citizenship, raising important questions about how digital tools influence democratic life.

Against this backdrop, the present review synthesizes 20 recent studies that, taken together, illuminate the nexus between institutional online communication and civic participation in education-related public policy. This corpus[1] spans diverse disciplinary traditions—public administration, communication studies, political science, psychology, education, and community psychology—and employs a wide range of methodologies, from content analysis of thousands of social-media posts (Zeru et al., 2023) and randomized controlled trials of peer-led online communities (Ugarte et al., 2023) to ethnographic case studies of museum-based edu-communication (Rivero et al., 2023) and action-research evaluations of civic engagement curricula for at-risk youth (Balcazar et al., 2024). While heterogeneous in scope, context and epistemic orientation, these studies converge on a set of common concerns: transparency and trust; affordances and limitations of social-media platforms; digital inclusion versus new forms of exclusion; the role of open data; the cultivation of critical, moral and affective dispositions; and the capacity of arts-based and peer-led interventions to translate online engagement into offline participation and policy impact.

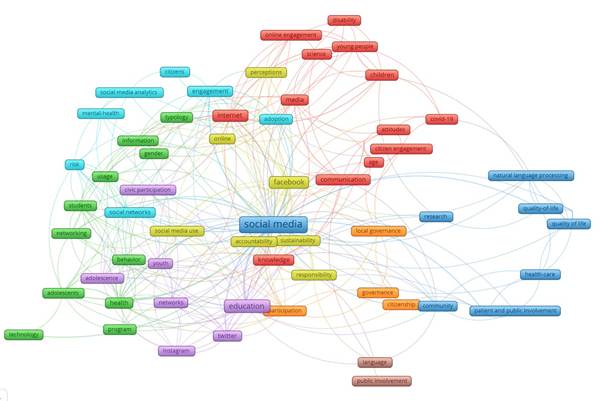

This literature review proceeds in three axes. First, it problematizes the concept of “institutional online communication” by tracing its evolution from one-way information broadcasting to co-creative and dialogic models consistent with open-government and participatory-governance paradigms. Second, it defines “civic participation” in education policy as a multidimensional construct encompassing informational consumption, expressive acts, collective deliberation, and direct advocacy, both online and offline. Third, it articulates the review’s organizing logic: a thematic taxonomy that clusters the 20 studies into four interrelated domains: (1) transparency, open data and accountability; (2) engagement affordances and participation gaps on social media; (3) pedagogies of critical digital citizenship; and (4) inclusive, arts-based and peer-led models of civic activation (Figure 1). Each domain reflects a distinct but overlapping theoretical conversation, enabling a structured yet integrative narrative that moves from macro-level institutional frameworks to micro-level pedagogical practices.

Figure 1: Thematic clusters of co-occurring keywords in the reviewed literature on institutional online communication and civic participation in education policy

Note. Node size reflects frequency, link thickness indicates strength of co-occurrence, and colors represent clusters generated by VOSviewer (Web of Science data).

By examining how these strands of scholarship illuminate the potentials and pitfalls of digital-first institutional communication in education policy, the review aims to accomplish three objectives. It provides a synthetic map of the field to date, highlighting reciprocal insights and unresolved tensions. It develops a conceptual model that links modalities of institutional communication (transparency, dialogue, co-creation) with forms of civic participation (informational, deliberative, co-productive), mediated by digital affordances, socio-cultural contexts, and pedagogical interventions. Finally, it identifies directions for future inquiry, policy innovation, and democratic practice, emphasizing that the legitimacy of education reform in the digital age depends not only on evidence-based content but also on communicative processes that genuinely recognize citizens as partners in shaping pathways of collective learning.

Methodology

This literature review examines the impact of institutional online communication on civic participation in educational public policy. To ensure methodological rigor, we conducted a search in the Web of Science – Core Collection, chosen for its strict inclusion criteria, international recognition, and broad coverage of communication, education, and social sciences. The review was restricted to peer-reviewed journal articles published in English between 2010 and 2024. The starting point of 2010 was selected because it marks the period when public institutions and educational authorities began systematically adopting social media platforms and digital communication channels, generating a new wave of research on digital governance, online transparency, and participatory practices. This cut-off ensured that the review captures the scholarly debate from the moment when digital communication moved from experimental use to institutional mainstreaming. The upper limit of 2024 reflects the most recent research available at the time of the review, ensuring that the synthesis provides both historical depth and contemporary relevance. Inclusion criteria required that articles explicitly address the intersection of three thematic areas: digital public communication, civic or citizen participation, and education policy. Studies were excluded if they were conference proceedings, book chapters, non-peer-reviewed publications, or if they referred to these themes only tangentially. The search query was designed to capture this intersection as accurately as possible. Specifically, we used the following query:

ALL=(("public communication" OR "government communication" OR "digital communication" OR "social media") AND ("citizen engagement" OR "public involvement" OR "civic participation" OR "online engagement") AND ("education" OR "education policy" OR "school policy" OR "educational reform")).

The search yielded a total of 87 articles, from which 56 were initially selected based on their theoretical relevance and empirical contribution to the central theme. The inclusion criteria required that articles explicitly address the relationship between institutional digital communication and civic participation, with direct or indirect implications for the education sector. All selected articles were indexed in SSCI or SCI-Expanded and were imported into Zotero for structured thematic coding and in-depth reading. Following the full-text screening stage, 20 studies met all inclusion criteria and were retained in the final analytical corpus. These articles explicitly addressed the relationship between institutional digital communication and civic participation with direct or indirect implications for the education sector. Studies were excluded when they only mentioned these themes tangentially, lacked empirical grounding, or did not establish a clear link between communication practices and participatory processes in education. The final set of 20 articles therefore represents the most relevant and methodologically consistent contributions available within the defined scope of the review.

We then analyzed the distribution of the 20 studies according to Web of Science Categories (WC) and Subject Categories (SC), identifying the most frequently associated domains. The most prominent WC categories were Education & Educational Research, Communication, Public Administration, Political Science, Social Work, and Government & Law, highlighting the interdisciplinary nature of the topic. In terms of SC classifications, the most relevant areas included Social Sciences – Interdisciplinary, Information Science & Library Science, Sociology, and Health Policy & Services. These subject areas underline the broader societal and policy contexts in which civic engagement through digital means is situated.

Literature review

Transparency, open data, and institutional accountability

Purwanto, Zuiderwijk, and Janssen’s (2020) multilevel framework for citizen engagement through open government data (OGD), grounded in the context of Indonesia’s 2014 presidential election digitization initiative, remains one of the most analytically comprehensive and empirically grounded models in the literature. The authors identify five foundational conditions—legal mandates, fiscal resources, feedback mechanisms, ease of engagement, and citizen motivation—that must be present for OGD initiatives to foster meaningful citizen participation. These prerequisites are complemented by six facilitating factors, such as the presence of a democratic political culture, inter-institutional coordination, public trust, and informal relational networks. Notably, their empirical findings suggest that these conditions do not operate as rigid prerequisites. Instead, they can be flexibly complemented or substituted by emergent, context-specific dynamics—such as a sense of urgency, digital literacy, skill diversity, or intensive social media usage—which can mitigate the absence or weakness of formal enablers. This insight marks a significant departure from linear or deterministic models of digital governance, instead emphasizing the adaptive, contingent nature of participatory infrastructures.

This insight resonates strongly with Rebolledo, Zamora-Medina, and Rodríguez-Virgili’s (2017) comparative study of 394 Spanish municipal websites. Despite robust legal obligations regarding transparency and participation, their research reveals low actual compliance with these mandates. Municipalities often treat transparency as a bureaucratic checkbox rather than an opportunity to reconfigure the communicative relationship between government and citizen. The analysis reveals significant disparities in data accessibility, frequency of updates, and interactivity features. In many cases, the existence of legal requirements does not translate into user-friendly, responsive digital spaces. This reinforces the argument of Purwanto et al. (2020): formal frameworks alone do not guarantee engagement unless they are embedded within broader relational, communicative, and cultural infrastructures. In other words, legal transparency must be translated into practical, usable, and dialogic formats if it is to engender public trust and civic involvement.

Further empirical support for this argument is provided by Zeru, Balaban, and Bârgăoanu (2023), whose large-scale content analysis of Romanian central government Facebook pages illustrates the persistence of top-down, symbolic communication logics. Although ministries such as Education maintain active profiles and publish content regularly, a detailed coding of posts shows that over 70% serve impression-management or image-enhancing purposes. Only 23% of messages convey informative content, and a mere 7% explicitly invite citizen input, discussion, or co-production. Even more telling is the public’s reaction: participatory posts—those which offer opportunities for involvement or deliberation—generate significantly fewer reactions, comments, and shares compared to symbolic or promotional content. This suggests a dual deficit: both in institutional willingness to foster participation and in the public’s responsiveness to such attempts when they do occur. Here, the digital interface becomes a space of missed potential, where architecture may allow for dialogic exchange but the communicative intent and culture do not.

However, this narrative is not entirely pessimistic. Alonso-Cañadas et al. (2023) introduce a counterpoint by examining how Spanish universities use Twitter to communicate about sustainability. Their findings reveal that when messages are normatively framed—i.e., grounded in values such as justice, equity, or intergenerational responsibility—they tend to receive significantly more interaction than generic informational tweets. This suggests that citizens and stakeholders respond not only to content that is informative but to content that resonates with shared moral or ethical commitments. This indicates that transparency should not be understood solely as a procedural requirement, but also as a communicative practice through which institutions can convey and reinforce shared social values. The implication is that public institutions, including those beyond the education sector, may increase engagement by aligning transparency with normative framing and by communicating not only facts, but meanings and values.

On the demand side, Guenther et al. (2022) examine how publics interpret and respond to technological developments in relation to trust, transparency, and democratic accountability. Drawing on a survey of 1,624 South African internet users, their findings indicate a generally high level of trust in science and broad support for public investment in research and development. At the same time, this trust coexists with concerns about the societal implications of emerging technologies, particularly regarding inequality, surveillance, and misinformation. Their analysis further shows that social media use is a significant predictor of both optimism and anxiety, as exposure to diverse information sources appears to foster cognitive complexity—enabling individuals to recognize tensions and hold ambivalent views simultaneously. For institutions operating in the field of education policy, these dynamics present a dual challenge and opportunity: digital transparency must extend beyond the provision of data or policy documents to include attention to affective and ethical dimensions of communication. In contexts where stakeholders seek reassurance, recognition, and value alignment, factual accessibility alone is unlikely to generate genuine trust or sustained civic engagement.

This leads to a deeper philosophical point articulated by D’Olimpio (2021), whose theory of “critical perspectivism” asserts that online moral reasoning requires both analytical clarity and empathic engagement. In her view, digital environments—characterised by speed, anonymity, and algorithmic curation—tend to amplify outrage, polarisation, and superficial judgment. To counter this, she argues for the cultivation of moral imagination: the ability to critically assess diverse perspectives while maintaining a commitment to fairness and compassion. Applied to the field of digital governance, this suggests that communication must go beyond instrumental rationality. It must also foster spaces for ethical reflection, collective storytelling, and mutual recognition.

Taken together, these contributions reveal a recurrent pattern: while the digitization of public communication increases efficiency and expands reach, several studies highlight that it often reproduces existing asymmetries of access and participation. Research shows that legal mandates and technological infrastructure create important enabling conditions, but by themselves they rarely guarantee inclusive or responsive engagement. Empirical findings also point to the role of cultural and relational dynamics in shaping how information is perceived, appropriated, and transformed into meaningful participation. In this light, the digital transformation of governance emerges not only as a technical and procedural shift, but also as a process with political and ethical implications that influence trust, legitimacy, and civic agency.

Engagement affordances and participation gaps on social media

The optimism surrounding social media as a tool for democratizing political participation has been met with a mix of empirical endorsement and theoretical caution. Valeriani and Vaccari’s (2016) tri-national survey provides one of the most compelling data-driven validations of the claim that social media can mitigate traditional participation gaps. Their research indicates that incidental exposure to political content on platforms like Facebook and Twitter—rather than deliberate engagement—has been associated with higher levels of online political participation. Importantly, the effect is stronger among individuals with lower political interest, suggesting that social media has the potential to mobilize otherwise disengaged citizens. This finding supports the thesis that the architecture of digital platforms, particularly their algorithmic capacity to present unexpected content, may serve as a latent equalizer in political engagement by lowering entry thresholds.

However, these participation-enhancing effects are neither universal nor unconditional. Cowling et al. (2025) offer a more cautious interpretation in their investigation of digital safety and wellbeing among pre-teens aged 10 to 13. Their research emphasizes that participation benefits hinge on foundational digital literacy and psychosocial wellbeing. Without adequate instruction in digital navigation, critical thinking, and emotional regulation, the risks of manipulation, anxiety, and exclusion increase. Throuvala et al. (2021), in a qualitative study of teachers' perspectives, reinforce this concern by identifying emotion regulation, metacognitive awareness, and digital resilience as core psychosocial competences that underpin safe and constructive online civic behaviour. These capacities enable young users to not only interpret but also critique and respond to digital content in a way that fosters democratic engagement rather than passive consumption or reactive hostility.

A further complicating factor is the socio-economic stratification of digital participation. Unver et al. (2023), focusing on digital adoption in Turkey, find that income, educational attainment, and digital skills are key predictors of whether citizens engage in online shopping. Although their study does not explicitly address civic engagement, the structural parallels are clear: if commercial digital activity is stratified, civic digital participation is likely similarly fragmented. This suggests that the mere availability of platforms is not sufficient; structural inequalities in access, skill, and motivation continue to shape who participates and how.

In the Romanian context, Zeru, Balaban, and Bârgăoanu (2023) offer a case study in the limits of social media-based public engagement. Despite a high volume of Facebook postings from Romanian ministries, including Education and Health, the content predominantly serves symbolic or promotional functions. There is little evidence of dialogic intent, deliberative framing, or feedback loops. Posts inviting active participation—whether through consultations or comment-based dialogue—receive lower engagement than those affirming institutional authority. This pattern suggests a strategic ambiguity: although institutional posts often display features associated with participation, empirical evidence indicates that these interactions rarely translate into substantive engagement. This aligns with the broader concern that surface-level interactivity—likes, shares, emoticons—should not be confused with genuine deliberative or participatory behavior.

A longitudinal observational study by Tasențe et al. (2023) further nuances this picture. Focusing on Romanian governmental communication throughout and beyond the pandemic, the authors observe a sharp decline in citizen engagement post-crisis. Despite this, governmental actors continued to project messages of reassurance and hope, aimed at maintaining social cohesion and institutional trust. The study’s key insight lies in its attention to tonality and emotional calibration: engagement is not merely a function of technical interactivity or issue salience, but also of how citizens feel they are being addressed—whether as passive recipients or active co-constructors of meaning. The findings imply that affective transparency—that is, the capacity to speak to public emotions—is as vital as procedural openness.

Costa-Sánchez and Míguez-González (2018) similarly highlight the emotional dimension of public interaction through a comparative analysis of two Spanish hospitals’ Facebook pages. Their study reveals that posts incorporating multimedia elements—especially images and videos that address sensitive topics such as terminal illness or patient rights—elicit more substantive interaction. This interaction is not limited to likes or views but extends to meaningful commentary and dialogic engagement. These findings reinforce the importance of content relevance and emotional resonance in driving not just visibility, but authentic engagement. Relevance is not merely topical; it is also experiential—citizens respond when content reflects their values, needs, or concerns.

Echoing this insight, Eger, Egerová, and Kryston (2019) explore how universities' Facebook pages use visual content and interactivity to enhance engagement. Their study finds that photo-rich posts, particularly those featuring real students and faculty, correlate with higher comment depth and long-term page loyalty. The implication is that platforms do not operate in a vacuum; they mediate relationships through visual and narrative cues that humanize institutions and foster identification. Where institutions appear detached or overly formalistic, engagement suffers. But when they signal authenticity and openness, publics are more likely to reciprocate with substantive engagement.

Chu’s (2018) ethnographic case study of Hong Kong secondary schools during the Umbrella Movement introduces a different layer of complexity. It examines how the affordances of WhatsApp and Facebook were associated with students’ rapid mobilization and protest organization. However, these same platforms became sites of institutional control: school authorities depicted digital activism as disruptive and imposed disciplinary measures. This illustrates that institutional gatekeeping remains a powerful force shaping participatory outcomes—even in digital spaces that are nominally open or decentralized. Social media’s potential for civic engagement can thus be undermined by hierarchical structures, particularly in educational settings where obedience and discipline may be prioritized over democratic expression.

Together, these studies caution against deterministic narratives of digital empowerment. While social media platforms do offer new affordances for political and civic engagement, contextual factors—cultural, institutional, economic, and psychological—fundamentally shape their participatory potential. Valeriani and Vaccari’s (2016) optimism is valid but bounded. Accidental exposure can function as a catalyst for civic engagement, yet empirical research shows that its effects are uneven and mediated by factors such as digital literacy, emotional readiness, institutional openness, and socioeconomic background. In the field of education, these dynamics are particularly visible: while digital platforms may lower entry barriers to participation, outcomes often depend on the capacities of students, parents, and teachers to critically interpret information and engage constructively. Studies further indicate that platform design or algorithmic features alone rarely generate sustained participation. Instead, levels of engagement appear to be shaped by complementary conditions, including the availability of training opportunities, the presence of communication practices attentive to emotions, and school or ministry cultures that facilitate inclusive dialogue. In this sense, educational stakeholders are not simply passive recipients of information but actors whose participation is contingent on structural, cultural, and relational factors within the education system.

Pedagogies of critical digital citizenship and moral engagement

In response to concerns identified in the literature about the superficiality, inequity, and emotional volatility of digital engagement, several studies discuss pedagogical frameworks that aim to foster more critical, inclusive, and ethically informed forms of civic participation. At the conceptual core of these approaches lies the recognition that civic behavior in digital contexts is not instinctive or automatic, but must be taught, modeled, and co-produced through education. D’Olimpio’s (2021) theory of critical perspectivism offers a compelling ethical and epistemological foundation for this agenda. Arguing that moral discernment in online environments requires both critical scrutiny and empathic engagement, D’Olimpio posits that media literacy should no longer be limited to fact-checking or platform navigation. Instead, it must explicitly include the ethical dimension of interpretation and response, training learners to evaluate not only what is true or false, but also what is just compassionate, and conducive to mutual understanding. In this way, critical perspectivism reframes civic education as a practice of moral imagination, capable of transforming digital citizens from reactive consumers into reflective co-creators.

Operationalizing these abstract principles, Porto, Golubeva, and Byram (2023) conducted an intercultural telecollaboration between undergraduate students in Argentina and the United States. Using arts-based, multimodal projects—ranging from digital collages to video storytelling—the students were invited to express personal experiences of COVID-19-related discomfort and to reframe them within collective, civic narratives. The digital platforms of choice—Instagram, YouTube, and collaborative editing tools—enabled students to disseminate their creative work beyond classroom boundaries and to invite public dialogue. Survey data and artefact analysis revealed patterns of transformative learning: students moved from expressing individual trauma to articulating a shared sense of responsibility, particularly in relation to mental health, social inequalities, and public messaging. In this context, artistic creation became a medium of civic expression, not merely a therapeutic outlet, reinforcing D’Olimpio’s (2021) thesis that emotional and ethical reflexivity must be integral to digital engagement pedagogies.

This emphasis on co-creative, community-centred learning is further reinforced by Rivero, Jové-Monclús, and Rubio-Navarro’s (2023) autoethnographic analysis of educational communication projects in a Spanish factory-museum. The museum’s approach merges formal learning goals with non-formal, participatory media practices, using digital storytelling to construct “heritage cyber-communities” around intangible cultural memory. Participants—students, educators, artists, and community members—collaborate to produce digital exhibits, video narratives, and online archives that reflect localized identities. The result is a rhizomatic model of civic identity, where learners see themselves not as abstract citizens, but as embedded members of lived, evolving communities. This work highlights the potential of museum-education partnerships to create non-hierarchical, experiential spaces in which civic learning is embedded in affective, historical, and relational dimensions—precisely the kind of complexity often missing from traditional civic education.

Further evidence for the value of participatory pedagogies comes from Faux-Nightingale et al. (2024), whose youth-centered project co-produced Long-COVID communication materials with 66 participants. Guided by the Lundy model—which prioritizes space, voice, audience, and influence—the project engaged young people in iterative design processes. They developed social media videos, illustrated flyers, and digital toolkits aimed at educating their peers about the long-term effects of COVID-19. Crucially, these materials were not simply consumed but were disseminated through schools and the UK’s National Health Service (NHS), giving them institutional visibility and practical impact. Participants reported increased civic confidence, a desire to further engage peers, and a sense of ownership over the message. The project thus exemplifies how youth-led co-production can transform passive recipients of information into empowered communicators, while also challenging adult-centric assumptions about credibility and authorship in public discourse.

This co-productive model finds an important parallel in the fieldwork of Malhotra et al. (2018), who studied marginalized communities in India and the integration of indigenous communication channels with mobile digital technologies. In their case, community members were involved in designing health and social messages using local idioms, storytelling forms, and culturally resonant visuals. The result was a dramatic increase in both message comprehension and behavioral uptake, particularly among low-literacy populations. What Malhotra et al. show is that cultural congruence and co-design are not optional enhancements but necessary conditions for effective digital civic engagement, especially in underserved or structurally excluded populations. By allowing communities to speak in their own symbolic languages, these interventions bridge not only literacy and access gaps, but also epistemic and emotional divides.

Taken together, these studies contribute to a growing body of literature that frames civic pedagogy as multimodal, participatory, and ethically oriented. From D’Olimpio’s (2021) ethical theory to the artistic praxis of Porto et al. (2023), the co-creative heritage projects of Rivero et al. (2023), the institutional outreach examined by Faux-Nightingale et al. (2024), and the culturally embedded activism analyzed by Malhotra et al. (2018), the findings converge on a common point: digital civic engagement in educational contexts is often shaped by situated, relational, and value-based practices. Rather than being captured through metrics such as likes, clicks, or shares, participation is observed where learning environments create opportunities for collaboration, critical reflection, and ethical dialogue.

This literature suggests an important shift in emphasis: from viewing digital literacy primarily as a set of technical skills, toward conceptualizing digital civic learning as an ongoing, reflective process embedded in educational systems. Case studies highlight that schools, universities, and related institutions play a central role in shaping this process, not only by integrating innovative pedagogies but also through the organizational cultures and infrastructures that mediate how learners engage with one another and with broader civic issues.

Inclusive, arts-based, and peer-led models of civic activation

Beyond formal curricula, recent research highlights the role of peer-led and community-based models as mechanisms that can foster digital civic engagement in scalable and sustainable ways. These studies note that top-down institutional initiatives frequently show limited effectiveness in reaching marginalized or less engaged populations, whereas horizontal forms of influence—where peers act as facilitators, role models, or mediators of civic discourse—tend to generate stronger interaction. Ugarte et al.’s (2023) randomized trial of the HOPE intervention on Facebook illustrates this approach: during the COVID-19 pandemic, trained peer leaders were integrated into Facebook groups for anxious adults, and the intervention was associated with measurable increases in help-seeking behavior and online interaction. While the study is not situated directly in the field of education, its findings are relevant for education policy debates, as they suggest that peer-facilitated communication strategies may influence how school communities, including students, teachers, and parents, interact in digital environments. In this perspective, institutional social media channels in education appear most effective when they are not limited to unidirectional information-sharing but embedded within participatory cultures that reflect relational and peer-supported dynamics.

This potential is further substantiated by Balcazar, Garcia, and Venson’s (2024) evaluation of a civic engagement curriculum in an alternative high school setting. The program specifically targeted students with histories of dropout or academic disengagement. Participants were invited to identify social problems relevant to their communities, develop multimedia campaigns, and implement advocacy strategies. The culminating public presentations and longitudinal reflection journals revealed significant increases in political self-efficacy, civic confidence, and a heightened sense of community orientation. What makes this study particularly compelling is that the participants—often labeled as "at-risk"—demonstrated not only competency but leadership in navigating civic spaces, both online and offline. These outcomes confirm that structured yet flexible engagement frameworks, when co-designed with youth and grounded in real-world relevance, can activate democratic capacities even among populations traditionally excluded from policy dialogue.

The affective and therapeutic dimensions of such engagement models should not be underestimated. Both Porto et al. (2023) and Ugarte et al. (2023) underscore how arts-based expression and peer support serve dual functions: they communicate civic or policy-relevant content and simultaneously mitigate emotional distress and promote solidarity. In the Argentine-U.S. telecollaboration led by Porto and colleagues, for instance, students translated personal discomfort into shared civic narratives via Instagram and YouTube, achieving not just awareness-raising but emotional reconciliation. Similarly, Ugarte et al.’s HOPE trial showed that peer interventions lowered anxiety levels while increasing public engagement. These findings resonate with Purwanto et al.’s (2020) multilevel model of open government data (OGD) engagement, which identified citizens' sense of urgency as a key driver of participation. Emotional intensity—whether derived from personal vulnerability, collective crisis, or community identity—emerges as a motivating force that formal structures alone cannot replicate.

Yet, the path to civic activation is not linear. Guenther et al. (2022) offer a cautionary counterpoint in their survey of South African digital users, noting that high generalized trust in institutions or science does not eliminate ambivalence or anxiety about technological futures. Respondents simultaneously supported public investment in technology and expressed concern about issues like inequality, surveillance, and misinformation. This complexity suggests that civic interventions must navigate emotional nuance, rather than presume enthusiasm or compliance. Even the best-designed engagement strategies can falter if they fail to acknowledge citizens' conflicting emotions—hope and fear, trust and skepticism, empowerment and fatigue.

These concerns become particularly salient in the context of adolescent participation, where psychosocial development intersects with digital exposure. Cowling et al. (2025) and Throuvala et al. (2021) jointly emphasize that digital safety and emotional literacy are not ancillary benefits of participation—they are preconditions. Cowling et al. (2025) argue that access to platforms without adequate instruction in digital literacy, critical thinking, or mental wellbeing poses serious risks for pre-teens and early adolescents. Throuvala et al.’s (2021) qualitative research with educators confirms that emotion regulation, digital resilience, and metacognitive awareness are foundational to positive online engagement. Without these, young people may either retreat from civic spaces or engage in ways that are reactive, defensive, or maladaptive. Therefore, institutional strategies aiming to enhance youth participation must embed emotional scaffolding alongside technological affordances.

Discussion

The findings presented in this review converge to form a multidimensional understanding of how institutional online communication shapes civic participation in educational public policies. While the corpus of studies spans diverse geopolitical and cultural contexts, a set of recurring patterns can be identified across actors. Students and teachers frequently appear as the most direct participants in school- or university-based initiatives, while parents and families are often involved through consultation processes or associations such as parent–teacher councils. In other cases, citizens more broadly engage with ministries of education through digital platforms, particularly in discussions of reforms or national policy. Taken together, these cases suggest the emergence of a shared communicative paradigm that transcends national boundaries. At the heart of this paradigm is the recognition that transparency and open data, although foundational, are insufficient on their own to catalyze meaningful engagement unless connected to the concrete experiences of these different stakeholder groups. As the cases of Indonesia (Purwanto et al., 2020) and Spain (Rebolledo et al., 2017) illustrate, legal frameworks and digital infrastructures must be matched by institutional willingness to co-create and engage in dialogue. Moreover, the Romanian context demonstrates how communication styles that incorporate strategic optimism and consistency, particularly during times of crisis, can sustain a sense of institutional legitimacy (Tasențe et al., 2024). Even when direct public engagement declines, as observed post-pandemic, the government's ability to project reassurance and continuity through digital channels can help preserve civic trust and cohesion (Tasențe et al., 2023).

Social media’s participatory affordances—such as comment threads, shares, and multimedia storytelling—represent both opportunities and challenges. On one hand, as demonstrated by Valeriani and Vaccari (2016), accidental exposure to political content can bridge participation gaps by engaging less politically active individuals. On the other hand, studies by Cowling et al. (2025) and Throuvala et al. (2021) highlight that meaningful engagement is not solely a function of access but is also influenced by digital literacy, psychosocial stability, and pedagogical support. This highlights a critical implication: communication strategies must be embedded within broader educational ecosystems that foster the cognitive, emotional, and ethical capacities of users to engage responsibly and effectively.

In this regard, the review also foregrounds the importance of pedagogy and inclusion. Studies exploring critical digital citizenship (D’Olimpio, 2021; Porto et al., 2023) reveal that civic participation flourishes in environments where students are not merely recipients of information but active co-creators of public meaning. The arts-based and peer-led interventions documented by Faux-Nightingale et al. (2024) and Ugarte et al. (2023) illustrate scalable and context-sensitive models of participatory design that extend institutional reach while empowering marginalized groups. These approaches highlight an essential shift: from communicating with citizens to communicating with citizens, and ultimately, through citizens as trusted communicators within their networks.

Another important contribution of the reviewed literature lies in clarifying the ambivalent role of digital platforms. Zeru et al. (2023) document the prevalence of self-promotional content on government Facebook pages, which attracts limited interaction when compared to normatively charged or dialogic content (Alonso-Cañadas et al., 2023). This reinforces the idea that the mere presence of institutional actors on digital platforms does not guarantee engagement. Instead, the structure, tone, and interactivity of messages, as well as the timing and social relevance of content, determine their participatory potential. In educational policy, where stakeholder expectations are often heightened and emotionally charged, institutions must therefore move beyond symbolic visibility to foster substantive deliberation.

Ultimately, the integrative view presented by these studies suggests that future efforts should reframe institutional communication as a form of civic infrastructure. In this shared space, information, affect, and agency intersect. This entails not only investing in technical capacities, but also in relational and ethical competencies, both within institutions and among citizens. Education policy, as a domain deeply embedded in social values, offers a privileged terrain for such innovation. By leveraging participatory tools, transparent practices, and inclusive pedagogies, public institutions can create communication environments that are not only informative but also transformative.

Limitations

Despite its breadth and depth, this review has limitations. First, the article selection process relied exclusively on the Web of Science – Core Collection, which, while ensuring high scholarly quality, may have excluded relevant empirical studies indexed in other databases such as Scopus, ERIC, or ProQuest. As a result, insights from practitioner-led evaluations or grey literature reports may be underrepresented, particularly those emerging from low- and middle-income countries where local initiatives may not reach international publication venues.

Second, although the studies reviewed span multiple methodological approaches, the review did not adopt a meta-analytic or statistical synthesis method. The narrative integration employed here is well-suited to identifying conceptual patterns and theoretical frameworks, but it limits the capacity to quantify the strength or consistency of effects across contexts. Moreover, the heterogeneity of variables—ranging from platform type and demographic group to national policy environment—makes cross-study comparison challenging and may obscure context-specific dynamics.

Third, the conceptualization of “civic participation” remains complex and context-dependent. Some studies equate participation with engagement metrics, such as likes or comments, while others emphasize deliberative quality, behavioral change, or policy outcomes. This definitional variance complicates direct comparisons and may lead to divergent interpretations of what constitutes “successful” civic communication.

Finally, as with all reviews, the synthesis is shaped by the researchers’ interpretive lens. While every effort has been made to maintain analytic neutrality and transparency, the selection and grouping of themes inevitably reflect subjective judgment. Future research would benefit from triangulating this review with empirical stakeholder interviews or participatory mapping exercises to validate the proposed conceptual framework.

Conclusions

This literature review has examined the evolving relationship between institutional online communication and civic participation in the domain of education policy. It reveals that while transparency and digital presence are foundational, they are insufficient unless accompanied by dialogic openness, participatory design, and inclusive pedagogies. Communication strategies that prioritise affective resonance, interactivity, and co-creation—particularly in times of crisis or reform—are more likely to foster sustained engagement and policy legitimacy.

The integration of arts-based, peer-led, and critical pedagogical approaches demonstrates that institutional communication can serve not only informational, but also formative and relational functions. Institutions that embrace this expanded role are better equipped to engage diverse publics, mitigate inequalities, and co-construct educational futures that are democratic, responsive, and inclusive.

To the best of our knowledge, this is the first review to synthesize research across such a wide array of international contexts, institutional settings, and methodological paradigms, encompassing online public communication and education policy. By articulating a coherent conceptual framework that links modes of communication to forms of civic participation, this review lays the groundwork for a more deliberative, participatory, and equitable digital governance of education. Future research and practice must continue to explore how digital communication can not only transmit information but also cultivate a sense of belonging, voice, and collective responsibility within educational communities.

References:

*Alonso-Cañadas, J., Saraite-Sariene, L., Galan-Valdivieso, F., & Caba-Perez, M. del C. (2023). Green tweets or not? The sustainable commitment of higher education institutions. Sage Open, 13(4). https://doi.org/10.1177/21582440231220097

*Balcazar, F. E., Garcia, M., & Venson, S. (2024). Civic engagement training at a school for youth with a history of dropping out. American Journal of Community Psychology, 73(3–4), 461–472. https://doi.org/10.1002/ajcp.12727

Campbell, D., & Niemi, R. (2016). Testing Civics: State-Level Civic Education Requirements and Political Knowledge. American Political Science Association, 110, 495–511.

Chadwick, A. (2013). The Hybrid Media System: Politics and Power. Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199759477.001.0001

*Chu, D. S. C. (2018). Media use and protest mobilization: A case study of umbrella movement within hong kong schools. Social Media + Society, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305118763350

*Costa-Sánchez, C., & Míguez-González, M.-I. (2018). Use of social media for health education and corporate communication of hospitals. Profesional de la Información, 27(5), 1145–1154. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2018.sep.18

*Cowling, M., Sim, K. N., Orlando, J., & Hamra, J. (2025). Untangling digital safety, literacy, and wellbeing in school activities for 10 to 13 year old students. Education and Information Technologies, 30(1), 941–958. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10639-024-13183-z

*D’Olimpio, L. (2021). Critical perspectivism: Educating for a moral response to media. Journal of Moral Education, 50(1, SI), 92–103. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057240.2020.1772213

*Eger, L., Egerova, D., & Kryston, M. (2019). Facebook and public relations in higher education. A case study of selected faculties from the czech republic and slovakia. Romanian Journal of Communication and Public Relations, 21(1), 7–30. https://doi.org/10.21018/rjcpr.2019.1.268

*Faux-Nightingale, A., Somayajula, G., Bradbury, C., Bray, L., Burton, C., Chew-Graham, C. A., Gardner, A., Griffin, A., Twohig, H., & Welsh, V. (2024). Coproducing health information materials with young people: Reflections and lessons learned. Health Expectations, 27(3). https://doi.org/10.1111/hex.14115

*Guenther, L., Reif, A., Taddicken, M., & Weingart, P. (2022). Positive but not uncritical: Perceptions of science and technology amongst South African online users. South African Journal of Science, 118(9–10). https://doi.org/10.17159/sajs.2022/11102

Hoskins, B., & Janmaat, J. G. (2019). Education, democracy and inequalities: Political engagement and citizenship education in Europe. Palgrave Macmillan.

*Malhotra, A., Sharma, R., Srinivasan, R., & Mathew, N. (2018). Widening the arc of indigenous communication: Examining potential for use of ICT in strengthening social and behavior change communication efforts with marginalized communities in India. Electronic Journal of Information Systems in Developing Countries, 84(4). https://doi.org/10.1002/isd2.12032

Mergel, I. (2015). Designing Social Media Strategies and Policies. In J. L. Perry & R. K. Christensen (Eds.), Handbook of Public Administration (3rd edition, pp. 456–468). Jossey-Bass Wiley.

Norris, P. (2001). Digital Divide? Civic Engagement, Information Poverty and the Internet Worldwide. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139164887

*Porto, M., Golubeva, I., & Byram, M. (2023). Channelling discomfort through the arts: A Covid-19 case study through an intercultural telecollaboration project. Language Teaching Research, 27(2, SI), 276–298. https://doi.org/10.1177/13621688211058245

*Purwanto, A., Zuiderwijk, A., & Janssen, M. (2020). Citizen engagement with open government data Lessons learned from Indonesia’s presidential election. Transforming Government - People Process and Policy, 14(1), 1–30. https://doi.org/10.1108/TG-06-2019-0051

*Rebolledo, M., Zamora-Medina, R., & Rodriguez-Virgili, J. (2017). Transparency in citizen participation tools and public information: A comparative study of the spanish city councils’ websites. Profesional de la Información, 26(3), 361–369. https://doi.org/10.3145/epi.2017.may.02

*Rivero, P., Jove-Monclus, G., & Rubio-Navarro, A. (2023). Edu-communication from museums to formal education: Cases around intangible cultural heritage and the co-creative paradigm. Heritage, 6(11), 7067–7082. https://doi.org/10.3390/heritage6110368

Sieber, R., Brandusescu, A., Sangiambut, S., & Adu-Daako, A. (2025). What is civic participation in artificial intelligence? Environment and Planning B: Urban Analytics and City Science, 52(6), 1388–1406. https://doi.org/10.1177/23998083241296200

Sunstein, C. R. (2018). #Republic: Divided Democracy in the Age of Social Media. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv8xnhtd

Tasențe, T., Rus, M., Stan, M.-I., & Sandu, M. L. (2024). Social Media in times of change: A three-period analysis of sentiment and engagement on the romanian ministry of education’s online presence. Mediaciones Sociales, 23, e-91667. https://doi.org/10.5209/meso.91667

* Tasențe, T., Rus, M., & Tanase, G. (2023). From Outbreak to Recovery: An Observational Analysis of the Romanian Government’s Online Communication during and post-COVID-19. Vivat Academia, 157, 1–21. https://doi.org/10.15178/va.2024.157.e1513

*Throuvala, M. A., Griffiths, M. D., Rennoldson, M., & Kuss, D. J. (2021). Psychosocial skills as a protective factor and other teacher recommendations for online harms prevention in schools: A qualitative analysis. Frontiers in Education, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.648512

*Ugarte, D. A., Cumberland, W. G., Singh, P., Saadat, S., Garett, R., & Young, S. D. (2023). A HOPE online community peer support intervention for help seeking: A randomized controlled trial. Psychiatric Services, 74(6), 648–651. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.202000817

*Unver, S., Aydemir, A. F., & Alkan, O. (2023). Predictors of Turkish individuals’ online shopping adoption: An empirical study on regional difference. PLOS ONE, 18(7). https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0288835

Vaccari, C., & Valeriani, A. (2021). Outside the Bubble: Social Media and Political Participation in Western Democracies. Oxford University Press.

*Valeriani, A., & Vaccari, C. (2016). Accidental exposure to politics on social media as online participation equalizer in Germany, Italy, and the United Kingdom. New Media & Society, 18(9), 1857–1874. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444815616223

*Zeru, F., Balaban, D. C., & Bargaoanu, A. (2023). Beyond self-presentation. An analysis of the romanian governmental communications on Facebook. Transylvanian Review of Administrative Sciences, 70E, 156–172. https://doi.org/10.24193/tras.70E.8

Zhuravskaya, E., Petrova, M., & Enikolopov, R. (2020). Political Effects of the Internet and Social Media. Annual Review of Economics, 12, 415–438. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-economics-081919-050239

How to cite: Sandu, M. L., & Tasențe, T. (2026). Institutional Online Communication and Civic Participation in Education Policy: A Literature Review. Dixit, 40, e4696. https://doi.org/10.22235/d.v40.4696

Funding: This study did not receive any external funding or financial support.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Authors’ contribution (CRediT Taxonomy): 1. Conceptualization; 2. Data curation; 3. Formal Analysis; 4. Funding acquisition; 5. Investigation; 6. Methodology; 7. Project administration; 8. Resources; 9. Software; 10. Supervision; 11. Validation; 12. Visualization; 13. Writing: original draft; 14. Writing: review & editing.

M. L. S. has contributed in 1, 5, 6, 9, 10, 11, 13, 14; T. T. in 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 12, 13, 14.

Scientific editor in charge: A. L.

Dixit v40

january – december 2026

10.22235/d.v40.4696