10.22235/d.v38.3644

Research articles

Strategic Sentiments: The European Commission’s Social Media Response to the Russia-Ukraine Crisis

Sentimientos estratégicos: la respuesta de la Comisión Europea en las redes sociales a la crisis entre Rusia y Ucrania

Sentimentos estratégicos: A resposta da Comissão Europeia na mídia social à crise Rússia-Ucrânia

Tănase Tasențe1 ORCID: 0000-0002-3164-5894

Maria Butacu2 ORCID: 0009-0005-7970-8267

Mihaela Rus1 ORCID: 0000-0002-3436-748X

1 Ovidius University of Constanța, Romania, [email protected]

2 Independent researcher, Romania

3 Ovidius University of Constanța, Romania

Abstract:

The use of online platforms by the European

Commission, particularly during the Russia-Ukraine crisis in the context of the

digital age, offers informative insights about current crisis communication.

Between February 1 and October 26, 2022, this study analysed the Commission’s

activities on the primary platforms, Facebook and Twitter. To carry out this

analysis, the study used RStudio and the SentimentAnalysis package within R.

The Blake & Mouton’s Grid was additionally employed as a reference point to

extract the strategic dimensions. The data revealed distinct usage patterns by

the Commission: Twitter acted as a channel for quick and immediate updates,

making use of its real-time communication capabilities, while Facebook was used

for more detailed conversations with a wider audience. Regarding sentiment,

most of the Commission’s communications had a neutral or positive tone.

Nevertheless, there were cases where certain critical issues prompted the

Commission to take definite positions, providing insight into their strategic

intent and priorities. To summarise, the European Commission’s online

communication during the relevant period showed an informed and

platform-specific methodology. Through comprehending and improving the

platforms' functionalities and audience preferences, the Commission established

a communication structure that can be utilised as a model for entities that

intend to simplify their digital interaction procedures, particularly in the

event of a crisis.

Keywords: crisis communication; digital strategy; European Commission; sentiment analysis; geopolitical events.

Resumen:

El uso de plataformas en línea por parte de la Comisión

Europea, especialmente durante la crisis entre Rusia y Ucrania en el contexto

de la era digital, ofrece perspectivas informativas sobre la comunicación de

crisis actual. Este estudio analizó las actividades de la Comisión en las

principales plataformas, Facebook y Twitter, entre el 1 de febrero y el 26 de

octubre de 2022. Para llevar a cabo este análisis, se utilizó RStudio y el

paquete SentimentAnalysis dentro de R. Además, se empleó Blake & Mouton’s

Grid como punto de referencia para extraer las dimensiones estratégicas. Los

datos revelaron distintos patrones de uso por parte de la Comisión: Twitter

actuó como canal para actualizaciones rápidas e inmediatas, aprovechando sus

capacidades de comunicación en tiempo real, mientras que Facebook se utilizó

para conversaciones más detalladas con un público más amplio. En cuanto al

sentimiento, la mayoría de las comunicaciones de la Comisión tuvieron un tono

neutro o positivo. No obstante, hubo casos en los que determinadas cuestiones

críticas llevaron a la Comisión a adoptar posturas definidas, lo que permitió

conocer su intención estratégica y sus prioridades. En resumen, la comunicación

en línea de la Comisión Europea durante el período en cuestión mostró una

metodología informada y específica para cada plataforma. Al comprender y

mejorar las funcionalidades de las plataformas y las preferencias de la

audiencia, la Comisión estableció una estructura de comunicación que puede

servir de modelo para las entidades que pretendan simplificar sus

procedimientos de interacción digital, especialmente en caso de crisis.

Palabras clave: comunicación de crisis; estrategia digital; Comisión Europea; análisis de sentimientos; acontecimientos geopolíticos.

Resumo:

O uso de plataformas on-line pela Comissão

Europeia, especialmente durante a crise Rússia-Ucrânia no contexto da era

digital, oferece percepções informativas sobre a comunicação de crise atual.

Entre 1º de fevereiro e 26 de outubro de 2022, este estudo analisou as

atividades da Comissão nas principais plataformas, Facebook e Twitter. Para

realizar essa análise, o estudo usou o RStudio e o pacote SentimentAnalysis no

R. A grade de Blake & Mouton também foi empregada como ponto de referência

para extrair as dimensões estratégicas. Os dados revelaram padrões de uso

distintos por parte da Comissão: O Twitter atuou como um canal para

atualizações rápidas e imediatas, fazendo uso de seus recursos de comunicação

em tempo real, enquanto o Facebook foi usado para conversas mais detalhadas com

um público mais amplo. Com relação ao sentimento, a maioria das comunicações da

Comissão teve um tom neutro ou positivo. No entanto, houve casos em que certas

questões críticas levaram a Comissão a tomar posições definidas, fornecendo uma

visão de suas intenções e prioridades estratégicas. Em resumo, a comunicação

on-line da Comissão Europeia durante o período relevante mostrou uma

metodologia informada e específica para a plataforma. Ao compreender e

aprimorar as funcionalidades das plataformas e as preferências do público, a

Comissão estabeleceu uma estrutura de comunicação que pode ser utilizada como

modelo para entidades que pretendem simplificar seus procedimentos de interação

digital, especialmente em caso de crise.

Palavras-chave: comunicação de crise; estratégia digital; Comissão Europeia; análise de sentimentos; eventos geopolíticos.

Recibido: 22/08/2023

Revisado: 23/02/2024

Aceptado: 26/02/2024

Introduction

Originating from Aristotelian philosophy, the word ‘krisis’ comes from the emphasis on ‘crisis’ meaning evaluation and ‘kraten’ for leading (Aristotle). Its etymology reveals its significance: the necessity for decision-making and judgement. Barton (1993) defines that a crisis, lacking the necessity of decision-making, does not exist. Barton describes a crisis as unforeseeable, significant occurrences that may cause negative effects, which may impact an organization’s employees, products, finances, and reputation.

Crises can be classified according to various metrics. Their occurrence results in categories like political, economic, cultural or religious crises. Identifying a resolution and settling the crisis give rise to categories such as development, legitimacy, competence, and honesty crises. Moreover, they can be demarcated regarding their milieu (internal or external) or urgent resolution (immediate, urgent, or prolonged). Additionally, further classifications are based on spatial scales, ranging from local to global.

By using a different perspective, Newsom et al. (2010) distinguish crises into violent and non-violent categories, each comprising three subcategories: natural-induced, intentional human actions, and unintentional human actions.

Pauchant & Mitroff’s (1992) typology merges internal and external human causes with technological, economic, and social factors. Their categorisation recognises crises originating from techno-economic externalities, internal technical and economic disruptions, external societal factors, and internal socio-human issues.

When evaluating crises, a three-phase strategy becomes relevant: pre-crisis, crisis, and post-crisis. The pre-crisis stage encourages a proactive attitude, including detecting warning signals, averting crises, and preparing for potential disruptions. The crisis stage varies among organizations, with the management intricately linked to the organization’s handling strategy. The post-crisis stage assesses the aftermath of the crisis, devises strategies for future situations, and prepares the organization for potential aftershocks. Additionally, it scrutinizes the crisis’s aftermath on the organization’s image and financial condition.

During a crisis, managing internal and external communications becomes essential. Inadequate internal communication can cause employees to react in contrasting ways, leading to hostility towards the organization. Unresolved conflicts, however, can increase risks, further intensifying the crisis and damaging an organization’s reputation (Hăbășescu, 2015). This emphasises the importance of having aligned communication objectives and mechanisms in place during crises. Effective external communication, particularly with the press, plays a crucial role in managing public perceptions and responses. Managing perceptions and responses heavily rely on external communications, especially with the press.

In today’s digital era, the importance of social media in crisis communication is undeniable. These platforms such as Twitter[1], Facebook, and Instagram, among others, have transformed the way crises unfold by moving from conventional channels to primarily online pathways. Efficient crisis management relies on creating suitable communication channels, determining when and whom to inform, selecting the right communicator, and deciding what information to communicate.

Crises on digital platforms, especially on social media, require an immediate and personalised response, as they occur instantaneously. Proficient communicators must understand the situation and use effective communication techniques while showing empathy and concern. Witt & Morgdan (2003) highlighted the significance of exhibiting compassion during crises, stating the media’s influential part in shaping public opinion. Therefore, expertise and readiness are essential for averting and managing crises successfully.

In the field of crisis communication and management, Coombs (2001) presents a comprehensive three-stage plan: pre-crisis, crisis event, and post-crisis. Among them, crisis recognition and response are considered the most vital. Crisis recognition relates to the process whereby a crisis is declared and confirmed by various institutional agents such as business, political, and media representatives based on three factors: crisis dimensions, dominant coalition expertise, and persuasive presentation. Following crisis recognition, the crisis response serves as the precursor to taking concrete actions during the crisis events. Upon receiving the latest information, a crisis management team must keep both internal and external stakeholders informed about the team’s statements, plans and actions. Communication should ideally be prompt, consistent and transparent. The crisis response should involve guidance information to mitigate severe damages and to refine information for reputation management.

Drawing from Image Repair Theory research, Coombs (2021) introduces the Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT). The framework facilitates a more customised public relations approach to the reckoning of reputational threats during crises. While using the SCCT framework, the crisis management team ought to identify the crisis type(s), evaluate crisis history, and be conscious of its previous reputation. Coombs classifies various detailed response strategies into four categories, i.e., denial, diminishment, rebuilding, and bolstering. The strategy of denial involves two primary tactics: attacker rebuttal and scapegoating. The former involves systematically countering the claims made by the other party, while the latter involves attributing blame to external entities or individuals. Diminishment includes excuses and justifications. Making an excuse involves identifying the reasons behind the crisis and behaviours. Rebuilding involves providing compensation and apologies, which requires responsible parties to compensate and apologise for their wrongdoings. Lastly, bolstering, which accentuates the praiseworthy aspects of stakeholders, is divided into remembering, flattering, and pitying.

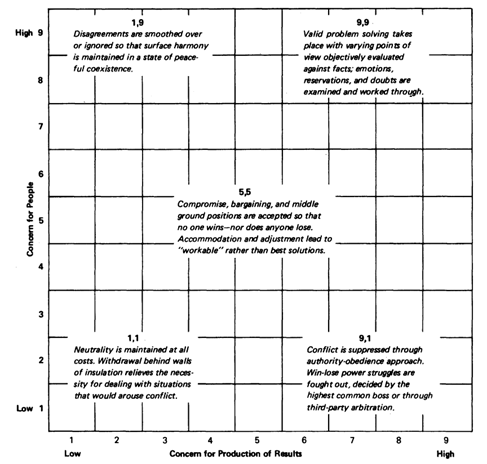

According to Blake & Mouton (1970), a risk assessment grid is put forward, which outlines five communication tactics or methods (Figure 1).

Figure 1: The Conflict Grid

Source: Blake & Mouton (1970)

Avoidance (1,1), as inferred, involves strategies such as withdrawal, silence, and temporary forgetfulness to prevent or resolve conflicts. Other scholars highlight other methods of avoidance, such as approaching a different buyer. Competition, confrontation, or combat (9,1) pursues one’s interests but overlook those of partners. This can take different forms: indirect competition - where rules are covertly manipulated and information is hidden, direct combat - featuring aggressive verbal or physical behaviour, or fair play, where trust prevails, rules are followed, and solutions that benefit everyone are sought.

Compromise (5,5) involves both parties making certain concessions, often giving up less crucial desires to achieve more significant gains. This method relies on negotiations between the two parties, aiming to seek mutual benefits. Adaptation or accommodation (1,9) implies one party conceding ground to the other. This approach is common when relationships are more important than conflicting issues, aiming to maintain harmonious relationships. However, it may delay conflict resolution or create conditions for future conflicts. Collaboration (9,9) aims to solve problems through negotiations to reach a mutually satisfying understanding. Distinguished from compromise, collaboration emphasises creative negotiation to improve the situation instead of merely pleasing the parties involved. It identifies collective and individual goals first and then discusses ways to achieve them without adversely affecting others.

Literature Review

Various communication challenges and responses have arisen due to the complex information environment that surrounds the Russia-Ukraine conflict. Leaders and organizations have used various online platforms, especially Twitter, to frame narratives and influence public perception, which has been a significant aspect of the discourse.

Olivares García et al. (2022) analysed President Volodymyr Zelensky’s use of social media during the initial stages of the Russian invasion of Ukraine. The study highlights the efficacy of these platforms in communicating both within Ukraine and to the international community.

In his analysis of the initial year of the Russian invasion, Nisch (2024) examines the frames and sentiments used by Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelensky when communicating on Twitter. The author reveals that Zelensky’s online rhetoric throughout the conflict period was primarily positive, emphasising dialogue, cooperation, and solidarity, with only minor discourse changes.

Plazas-Olmedo and López-Rabadán (2023) investigate how President Zelensky used Instagram videos to project a ‘spectacular’ image, strategically combining professional and amateur elements to widen the reach and impact of his messages.

Additionally, Lichtenstein & Koerth (2022) demonstrate the framing of the conflict in European media through their study on the German television system. The research shows that the Ukraine crisis was framed differently depending on the TV format. Public service news aligned with the government’s framing, while foreign and infotainment programs contested the legitimacy of German crisis policy. This highlights the presence of multiple narratives that appear simultaneously, influenced by various media conventions.

Providing another perspective, Gurkov & Dahms (2024) highlight the communication strategies that multinational subsidiaries have adopted amid the Russia-Ukraine conflict. The authors, by defining two novel tactics —“shut the door” and “burning bridges”—, extending the Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT), demonstrate the transformation of organizational communication in response to geopolitical disruptions.

Vasile (2023) explores the finer points of prosocial crisis communication, examining how formal, non-formal, and informal entities responded to the arrival of Ukrainian refugees in Romania. By conducting a content analysis of various social media platforms and websites, this author offers insight into the appropriateness, effectiveness, and consistency of communication strategies during social crises.

Manfredi-Sánchez & Smith’s (2022) emphasis on the mediatisation of diplomacy highlights the EU’s evolving public diplomacy strategies throughout various crises, including the Ukraine conflict. The research highlights that the EU has sometimes been successful in restoring confidence, but it still faces challenges in combating disinformation. These findings are in agreement with those of Mir et al. (2023), who, by conducting an evaluation of tweets, illustrate the global opinions about the Russia-Ukraine conflict. The analysis shows that Twitter users mostly express support towards Ukraine, and highlights the significant role of verified Twitter accounts in attracting online attention.

An additional important aspect to consider is how nations react to accusations during crisis situations. In their 2021 study, Fadel Arandas & Yoke Ling’s examine Russia’s communication response following the MH17 tragedy, emphasising their use of image repair tactics. The researchers found that Russia primarily employed denial and shift-the-blame tactics, which effectively repaired their image.

Research methodology

The aim of this investigation is to deliver an extensive analysis of the online communication tactics employed by the European Commission throughout catastrophic incidents. The particular emphasis is given to their use of social media platforms, such as Twitter and Facebook. The study seeks to explain the frequency of posts, the public reaction to them, sharing patterns in social groups, communication direction, and the sentiment orientation of the posts.

Data was procured from the official Facebook and Twitter pages of the European Commission for this study. The data analysis was conducted using the RStudio software. The following are the procedural steps taken during the research:

- Collection of Facebook Data: The FanpageKarma platform was used to aggregate data from Facebook publications.

- Collection of Twitter Data: We utilized the rtweet package (Kearney et al., 2023) in RStudio to collect data on Twitter posts.

- Temporal Limitations: To acquire insightful information, we subjected the data to temporal constraints (01.02.2022 – 26.10.2022) to allow for the examination of pre-crisis, and during crisis times.

- Key Performance Indicators (KPIs): Metrics such as the frequency of posts during the monitoring period, the number of public reactions to each institutional message were visually represented.

- Sentiment analysis: Sentiment analysis of audience feedback was performed using the SentimentAnalysis (Proellochs & Feuerriegel, 2021) package in R. Textual content sentiment is assessed using this package in R. Standard dictionaries such as Harvard IV and financial-specific dictionaries are employed. In addition, this package enables the creation of user-defined dictionaries.

- The communication style utilized in crises was evaluated by analysing Facebook and Twitter posts, using the Risk Evaluation Grid by Blake & Mouton (1970) as the framework. The grid presented earlier (Figure 1) depicts five different communication styles or strategies: avoidance, competition, compromise, accommodation, and collaboration.

The given methodology provides a systematic approach to evaluate the European Commission’s communication effectiveness and image management during crises by using their social media channels, specifically, Facebook and Twitter, as a primary source of data.

Results

Frequency of posts on Facebook and Twitter

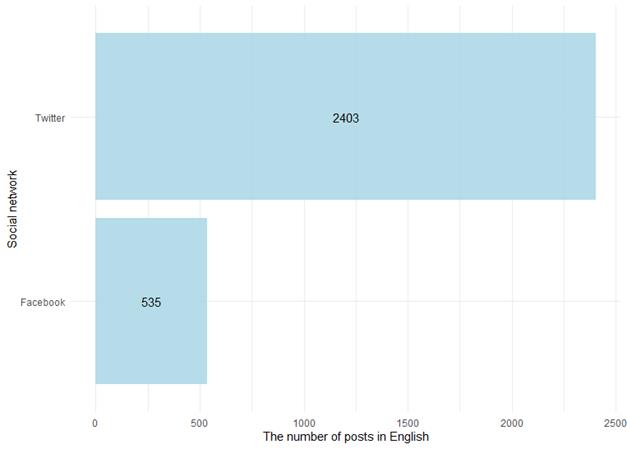

Between 1 February 2022 and 26 October 2022, an analysis of the European Commission’s social media activity indicates a significant inclination towards Twitter over Facebook. During that time, the European Commission published 2,403 tweets on Twitter, in comparison to a significantly lower 535 posts on Facebook (Figure 2).

A difference in the frequency of posts may indicate that the European Commission considers Twitter to be more effective in rapidly disseminating information and engaging with its audience in real-time. Twitter’s design, which favours short and immediate messages, may be better suited to the Commission’s communication requirements during this period.

Conversely, the smaller number of Facebook posts may suggest using this platform for more infrequent but comprehensive updates or discussions. This posting behaviour is probably influenced by the nature of each platform, with Twitter focusing on immediate updates and Facebook providing the ability to make more in-depth posts.

Figure 2: Frequency of posts on Facebook and Twitter

Analysis of reactions during the crisis period

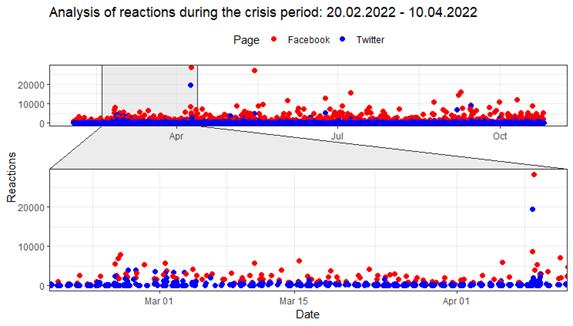

During the observed period of February 20 to April 10, 2022, reactions to the Facebook posts by the European Commission displayed a notable level of activity (Figure 3). On average, every post got 2,491 reactions from Facebook users. One particular post has gathered a significantly increased number of reactions, reaching 28,404 in total. Regarding reactions, the median count of reactions per post was 1,648. The first quartile (Q1) showcased 894 reactions per post, while the third quartile (Q3) peaked at 3,019 reactions per post.

Figure 3: Analysis of reactions during the crisis period

In comparison, over the same period, the European Commission’s Twitter posts received an average of 220.9 reactions per post. A specific post on the platform received 19,422 reactions, pointing to a surge in user engagement. The middle value of reactions per post on Twitter, also known as the median, was 125. The range between the smallest 25% of reactions per post, known as the first quartile, began at a minimum of 50 reactions per post, whilst the largest 25%, known as the third quartile, ended at a maximum of 231 reactions per post.

It is essential to note that there is a considerable difference in the number of reactions between the two platforms, with Facebook amassing a significantly more substantial number of responses. Certain significant events during the observation period can rationalise this discrepancy. The Russian military invasion of Ukraine began on February 24th. This was followed by another significant event, the ‘bombing of the Mariupol maternity hospital’. Both crises received significant attention and provoked strong public reactions.

It can be inferred from this date that, in moments of crisis, the general public demonstrated a preference for Facebook as their primary platform to respond and engage with the European Commission’s updates. Both platforms were mediums for information dissemination, but during critical times, Facebook emerged as the preferred platform for users.

Considering the broader implications of these findings is crucial. The observation that Facebook is being more inclined during crisis events suggests that the platform might have a more extensive reach, engagement, or public trust when it comes to crucial updates. These insights can inform communication strategies of organisations, particularly during moments of high public interest or crisis. Decisions on prioritising content release, structuring engagement campaigns, and understanding where audiences are most active during specific events become critical.

Analysis of the sentiment indicator during the crisis period

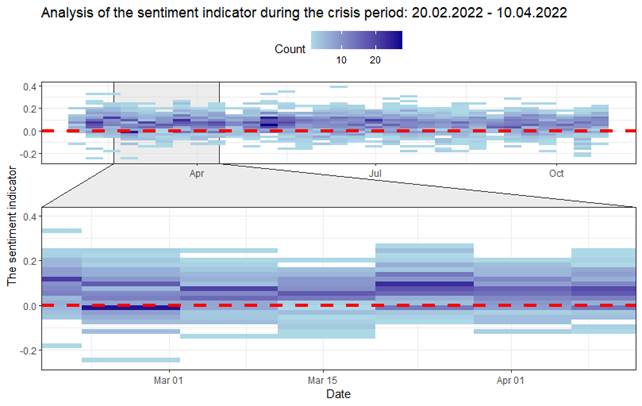

Sentiment analysis is a key tool for comprehending opinions, attitudes, and emotional responses towards specific events or time frames. The period from the 20th of February to the 10th of April in 2022, which we have dubbed ‘the powerful crisis period,’ offers an intriguing context to analyse sentiment metrics, particularly in relation to the communication channels utilised by the European Commission.

Figure 4 provides a numerical representation of sentiment scores across the European Commission’s communication channels, namely Facebook and Twitter. It is worth noting that both these channels portray the same average sentiment score. By the quantitative measures, the score is 0.06, which is within a standardized scale ranging from -1 (meaning an entirely negative sentiment) to +1 (which indicates a wholly positive sentiment). It is essential to understand that a sentiment score around 0 indicates neutrality, a score closer to -1 displays negativity, and a score edging towards +1 represents positivity. Therefore, the recorded value of 0.06 suggests sentiment leaning towards positivity, but it remains relatively neutral.

Figure 4: Analysis of the sentiment indicator during the crisis period

Moreover, after examining the sentiment indicators closely, it’s clear that the crisis period does not differ significantly from the overall monitored period. A sentiment score of 0.06 is consistently observed for both durations. The consistency observed here attests to the stability of the European Commission’s discursive tone during the crisis period, despite exigencies or specific occurrences during that span.

It can be concluded that the European Commission adopted a communicative stance that ranged from neutral to marginally positive during the specified crisis period. It can be inferred that the Commission aimed to project stability, reassurance, and balanced perspective during potentially turbulent times. From a perspective of communication strategy, such a tone may have been intentional to ensure clarity and avoid stirring panic or unnecessary concern among the audience.

To assess the discursive position and crisis management style, we will analyse four posts with the least favourable sentiment indicators.

On February 24, 2022, Ursula von der Leyen, the President of the European Commission, tweeted about the invasion of Ukraine by Russian forces. The content, tone, and specific choice of words reveal her adoption of one particular communication style during this crisis situation: “competition, confrontation, or conflict” as described by Blake & Mouton (1970).

The tweet explicitly states: “Russian forces invaded Ukraine, a free and sovereign country. We condemn this barbaric attack, and the cynical arguments used to justify it. Later today we will present a package of massive, targeted sanctions” (von der Leyen, 2022b). The selection of words such as “barbaric attack”, “invasion”, and “sanctions” inherently carry negative connotations. This language doesn’t suggest a nuanced or negotiated viewpoint but is a clear and assertive stance against Russia’s actions. The mention of “cynical arguments used to justify it” is a direct confrontation of the justifications provided by Russia. By promising a “package of massive, targeted sanctions”, von der Leyen is not just commenting but indicating a proactive, forceful response.

This tweet’s sentiment score of -0.25 underscores the negative sentiment, which is clearly intentional. This sentiment serves to highlight the gravity of the situation and firmly places the European Commission in opposition to the act.

On March 10, 2022, von der Leyen issued a statement on Twitter concerning the distressing event of the bombing in Mariupol: “The bombing of the Mariupol maternity hospital is inhumane, cruel, and tragic. I am convinced that this can be a war crime. We need a full investigation” (von der Leyen, 2022c). The language, tone, and overarching message of this tweet align with the “competition, confrontation, or battle” communication style.

In the tweet, von der Leyen’s choice of words such as “inhumane”, “cruel”, and “tragic” directly and unequivocally condemns the bombing act. This condemnation is further intensified by her assertion “I am convinced that this can be a war crime,” which not only signals a personal belief but also emphasizes the potential gravity of the event in the context of international law. The insistence on a “full investigation” underscores the European Commission’s demand for transparency and accountability regarding the incident.

The sentiment score of -0.13, while moderately low, is consistent with the nature of the event and the language used in the tweet. This score suggests that the tweet was successful in conveying a sense of gravity and negativity, reflective of the severity of the bombing and its implications.

On March 18, 2022, the European Commission disseminated a statement via Twitter that elucidated a policy stance: “Denying Russia’s most-favoured-nation status means that the country may be subject to higher tariffs and import bans” (European Commission, 2022). The composition, tone, and inherent implications of this message resonate with the “competition, confrontation, or battle” style of communication.

The European Commission’s tweet is grounded in its factuality. However, beneath its informational facade lies a firm and confrontational stance against Russia. By addressing the potential ramifications of denying Russia the “most-favoured-nation” status, the European Commission projects a willingness to impose punitive economic measures on Russia, manifesting in the forms of “higher tariffs and import bans”.

A sentiment score of -0.13, while moderately low, conveys the negative undertones of the message. This score, much like in previous instances, reflects the seriousness of the content and the potential adversarial consequences Russia might face. While the tweet doesn’t deploy overtly emotive language, its implications carry significant weight, generating a negative sentiment.

On February 22, 2022, Ursula von der Leyen articulated a definitive stance via Twitter: “Russia’s aggression against Ukraine is illegal and unacceptable. The Union remains united in its support for Ukraine’s sovereignty and territorial integrity. A first package of sanctions will be formally tabled today” (von der Leyen, 2022a). Reflecting upon the essence, tonului, and consequences suggested by this tweet, it aligns primarily with the “competition, confrontation, or battle” style of communication.

The substance of von der Leyen’s tweet unambiguously challenges Russia’s actions by employing terms such as “aggression”, “illegal” and “unacceptable.” Such direct vocabulary, without ambiguity or hedging, speaks to a confrontational disposition. Concurrently, by accentuating the unity of the European Union and its unwavering support for Ukraine, she underscores the collective stance of the EU member states, reinforcing the sentiment of confrontation. The communication reaches its climax with the proclamation of impending sanctions, indicating a tangible, reactive measure against the perceived aggression.

The sentiment score of -0.12, a moderately negative value, aligns well with the confrontational tone of the tweet. This score is emblematic of the serious nature of the content and the inherent repercussions insinuated by the proposed sanctions against Russia. Even in the absence of emotionally charged language, the tweet’s implications are potent, yielding a negative sentiment.

Discussion and conclusions

Based on the empirical findings and analysis, it is apparent that the online communication of the European Commission during the Russia-Ukraine war was strategically planned, data-focused, and responsive to current events.

To begin with, concerning frequency, the European Commission clearly favoured Twitter over Facebook. This preference implies a deliberate choice to use Twitter as the primary platform for prompt news updates and quick interactions, while Facebook was utilised as a forum for extensive involvement and detailed discussions.

Secondly, during the particular period of the crisis, the number of reactions on Facebook was much higher than those on Twitter. This pattern suggests that during times of intense geopolitical tension and international concern, the public was more inclined to turn to Facebook for comprehensive information and engagement. This insight might be useful for public relations and communication professionals who wish to comprehend platform preferences during crises.

Sentiment analysis showed that European Commission communications remained consistently neutral to slightly positive during this chaotic period, as the third point. This tone was notable on both Facebook and Twitter, indicating a strategic decision to maintain a balanced and measured communication approach. This could be interpreted as an effort to project an image of stability, clarity, and resilience, particularly during uncertain times.

Moreover, the comprehensive analysis of the four posts with the lowest sentiment scores presented the European Commission’s proficiency in situational communication. In particular, Ursula von der Leyen’s tweets embodied the communication style of “competition, confrontation, or conflict,” providing a clear and straightforward position against aggressive actions. These messages not only conveyed the seriousness of the situations but also expressed decisive and powerful opposition to alleged violations.

To conclude, the communication strategy of the European Commission during the conflict between Russia and Ukraine demonstrated precision, responsiveness, and adaptability. A noticeable distinction was observed in the usage and function of the two principal platforms, Twitter and Facebook. The former was a key resource for swift updates and prompt communication, while the latter became the primary platform for user engagement during critical periods.

The consistent tone and sentiment in their communications, leaning towards a neutral stance with a slight positive inclination, could be viewed as a tactical choice to uphold public confidence, ensure clarity, and prevent further escalation or panic. The results of this study furnish valuable information for policymakers, PR specialists, and communication strategists, highlighting the significance of customised approaches for different platforms and the need to sustain a consistent, lucid, and impartial communication strategy, particularly in times of crises.

References

Barton, L. (1993). Crisis in organizations: Managing and communicating in the heat of chaos. South-Western Pub.

Blake, R. R., & Mouton, J. S. (1970). The Fifth Achievement. The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science, 6(4), 413-426. https://doi.org/10.1177/002188637000600403

Coombs, W. T. (2021). Ongoing crisis communication: Planning, managing, and responding. Sage.

European Commission (@EU_Commission). (2022, March 18). Denying Russia’s most-favoured-nation status means that the country may be subject to higher tariffs and import bans (Image attached) (Post). X. https://x.com/vonderleyen/status/1496095277811388416

Fadel Arandas, M., & Yoke Ling, L. (2021). The Russian Crisis Communication Response Beyond Mh17 Tragedy. In C. S. Mustaffa, M. K. Ahmad, N. Yusof, M. B. M. H. Othman, & N. Tugiman (Eds.), Breaking the Barriers, Inspiring Tomorrow, vol 110. European Proceedings of Social and Behavioural Sciences (pp. 58-65). European Publisher. https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2021.06.02.8

Gurkov, I., & Dahms, S. (2024). Organizational communication strategies in response to major disruptions: The case of the worsening situation in the Russia-Ukraine conflict. International Journal of Organizational Analysis, 32(6), 1127-1140. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJOA-03-2023-3658

Hăbășescu, M. (2015). Comunicarea de criză, factor indispensabil în consolidarea reputației firmei. In Strategii şi politici de management în economia contemporană (4 ed., pp. 134-138). Departamentul Editorial-Poligrafic al ASEM.

Kearney, M. W., Sancho, L. R., Wickham, H., Heiss, A., Briatte, F., & Sidi, J. (2023). rtweet: Collecting Twitter Data (1.1.0) (Computer software). https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/rtweet/index.html

Lichtenstein, D., & Koerth, K. (2022). Different shows, different stories: How German TV formats challenged the government’s framing of the Ukraine crisis. Media, War & Conflict, 15(2), 125-145. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750635220909977

Manfredi-Sánchez, J.-L., & Smith, N. R. (2022). Public diplomacy in an age of perpetual crisis: Assessing the EU’s strategic narratives through six crises. Journal of Communication Management, 27(2), 241-258. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCOM-04-2022-0037

Mir, A. A., Rathinam, S., Gul, S., & Bhat, S. A. (2023). Exploring the perceived opinion of social media users about the Ukraine–Russia conflict through the naturalistic observation of tweets. Social Network Analysis and Mining, 13(1), 44. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13278-023-01047-2

Newsom, D., VanSlyke Turk, J., & Kruckeberg, D. (2010). Totul despre relațiile publice (2nd Edition). Polirom.

Nisch, S. (2024). Invasion of Ukraine: Frames and sentiments in Zelensky’s Twitter communication. Journal of Contemporary European Studies, 32(1), 110-124. https://doi.org/10.1080/14782804.2023.2198691

Olivares García, F. J., Román San Miguel, A., & Méndez Majuelos, I. (2022). Social networks as a journalistic communication tool. Volodímir Zelenski’s Digital Communication Strategy during the Ukraine war. Visual Review. International Visual Culture Review, 11(2), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.37467/revvisual.v9.3660

Pauchant, T. C., & Mitroff, I. (1992). Transforming the Crisis-Prone Organization: Preventing Individual, Organizational, and Environmental Tragedies. Jossey-Bass.

Plazas-Olmedo, M., & López-Rabadán, P. (2023). Selfies and Speeches of a President at War: Volodymyr Zelensky’s Strategy of Spectacularization on Instagram. Media and Communication, 11(2), 188-202. https://doi.org/10.17645/mac.v11i2.6366

Proellochs, N., & Feuerriegel, S. (2021). SentimentAnalysis: Dictionary-Based Sentiment Analysis (1.3-4) (Computer software). https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/SentimentAnalysis/index.html

Vasile, A. A. (2023). Formal, Non-formal, and Informal Approaches in Prosocial Crisis Communication while Dealing with Refugees from Conflict Areas. BRAIN. Broad Research in Artificial Intelligence and Neuroscience, 14(1), Article 1. https://doi.org/10.18662/brain/14.1/412

von der Leyen, U. (@vonderleyen). (2022a, February 22). Russia's aggression against Ukraine is illegal and unacceptable. The Union remains united in its support for Ukraine's sovereignty and territorial integrity (Thumbnail with link attached) (Post). X. https://x.com/vonderleyen/status/1496095277811388416

von der Leyen, U. (@vonderleyen). (2022b, February 24). Russian forces invaded Ukraine, a free and sovereign country. We condemn this barbaric attack, and the cynical arguments used to (Link attached) (Post). X. https://x.com/vonderleyen/status/1496749941301121027

von der Leyen, U. (@vonderleyen). (2022c, March 10). The bombing of the Mariupol maternity hospital is inhumane, cruel and tragic. I am convinced that this can be a war crime (Image attached) (Post). X. https://x.com/vonderleyen/status/1496095277811388416

Witt, J. L., & Morgdan, J. (2003). Stronger in the Broken Places: Nine Lessons for Turning Crisis into Triumph. Time Books.

Data availability: The dataset supporting the results of this study is not available.

How to cite: Tasențe, T., Butacu, M., & Rus, M. (2024). Strategic Sentiments: The European Commission’s Social Media Response to the Russia-Ukraine Crisis. Dixit, 38, e3644. https://doi.org/10.22235/d.v38.3644

Authors’ contribution (CRediT Taxonomy): 1. Conceptualization; 2. Data curation; 3. Formal Analysis; 4. Funding acquisition; 5. Investigation; 6. Methodology; 7. Project administration; 8. Resources; 9. Software; 10. Supervision; 11. Validation; 12. Visualization; 13. Writing: original draft; 14. Writing: review & editing.

T. T. has contributed in 1, 2, 3, 5, 9, 13, 14; M. B. in 6, 9, 12, 13, 14; M. R. in 1, 6, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14.

Scientific editor in charge: L. D.