10.22235/ech.v13i1.3665

Artigos originais

Experiências de estudantes do curso de licenciatura em enfermagem sobre supervisão clínica em uma universidade de Moçambique

Undergraduate Nursing Students’ Experiences of Clinical Supervision at a University in Mozambique

Experiencias de estudiantes de licenciatura en enfermería sobre la supervisión clínica

en una universidad de Mozambique

Cristina Simão Nota1, ORCID 0000-0002-0441-9816

Francisca Márquez-Doren2, ORCID 0000-0001-8093-4687

Camila Lucchini-Raies3, ORCID 0000-0001-5704-9778

1 Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Chile

2 Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Chile

3 Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Chile, [email protected]

Resumo:

Objetivo: Descrever as experiências dos

estudantes do último ano do Curso de Enfermagem da Universidade Católica de

Moçambique sobre a supervisão clínica prestada pelos técnicos de enfermagem.

Método: Estudo qualitativo-fenomenológico, realizado com estudantes do

último ano do Curso de Enfermagem da Universidade Católica de Moçambique. A

entrevista em profundidade foi a técnica utilizada para recolha de dados,

analisados através da análise de conteúdo.

Resultados: Os resultados foram divididos em quatro categorias

principais que emergiram da análise das entrevistas e dizem respeito 1) à

percepção dos alunos sobre o supervisor acadêmico, destacada pela presença e

ausência de docentes no ambiente clínico; 2) ao supervisor clínico explicitado

pelos supervisores técnicos de enfermagem, com subcategorias sobre o aluno de

nível superior como ameaça ao enfermeiro técnico, tensão na relação entre

supervisores clínicos e alunos, disposição e reação dos supervisores clínicos;

3) ao contexto, representado pela falta de recursos materiais e humanos,

diversidade cultural e pandemia de COVID-19; e 4) à percepção de si mesmos como

alunos, dividida em falta de orientação no ambiente clínico, vivência da

prática clínica como um pesadelo e esperança durante a experiência. Também são

apresentadas algumas propostas de melhorias.

Conclusão: Os resultados deste estudo permitiram descrever o fenômeno em

estudo, revelando a percepção dos estudantes sobre a supervisão clínica e o

efeito do contexto em que esta relação se desenvolve. Estes resultados servirão

para avaliar a forma de melhorar a supervisão clínica através da identificação

de um modelo inovador a seguir. Esta medida é essencial para o desenvolvimento

profissional dos estudantes de enfermagem.

Palavras-chave: educação em enfermagem; preceptoria; estudantes de enfermagem; enfermagem.

Abstract:

Objective: To describe the experiences of final year nursing students at

the Catholic University of Mozambique regarding the clinical supervision done

by nursing technicians.

Method: A qualitative-phenomenological study carried out with final year

nursing students at the Catholic University of Mozambique. The in-depth

interview was the technique used to collect data, which was analyzed using

Content Analysis.

Results: The results were divided into four main categories that emerged

from the analysis of the interviews and are related to 1) the students'

perception of the academic supervisor, highlighted by the presence and absence

of teaching staff in the clinical setting; 2) the clinical supervisor made

explicit by the nursing technical supervisors, with subcategories on the higher

level student as a threat to the technical nurse, tension in the relationship

between clinical supervisors and students, disposition and reaction of clinical

supervisors; 3) the context, represented by the lack of material and human

resources, cultural diversity and the COVID-19 pandemic; and 4) the perception

about themselves as students, divided into lack of orientation in the clinical

setting, living the clinical practice as a nightmare and hope during the

experience. Some proposals for improvement are also presented.

Conclusion: The results of this study have helped to describe the

phenomenon studied, revealing the students’ perception about clinical

supervision and the effect of the context that this relationship develops.

These results will help to evaluate how to improve clinical supervision by

identifying an innovative model to follow. This action is essential for the

professional development of nursing students.

Keywords: nursing education; preceptorship; nursing students; nursing.

Resumen:

Objetivo: Describir las experiencias de los

estudiantes de último año de enfermería de la Universidad Católica de

Mozambique en relación con la supervisión clínica realizada por los técnicos de

enfermería.

Método: Estudio cualitativo-fenomenológico realizado con estudiantes de

último año de enfermería de la Universidad Católica de Mozambique. La

entrevista en profundidad fue la técnica utilizada para la recolección de

datos, que fueron analizados a través del análisis de contenido.

Resultados: Los resultados se dividieron en cuatro categorías

principales que surgieron del análisis de las entrevistas y están relacionadas

con 1) la percepción de los estudiantes sobre el supervisor académico,

destacada por la presencia y ausencia de personal docente en el entorno

clínico; 2) el supervisor clínico explicitado por los supervisores técnicos de

enfermería, con subcategorías sobre el estudiante de nivel superior como

amenaza para el enfermero técnico, tensión en la relación entre supervisores

clínicos y estudiantes, disposición y reacción de los supervisores clínicos; 3)

al contexto, representado por la falta de recursos materiales y humanos, la

diversidad cultural y la pandemia COVID-19; y 4) a la percepción sobre ellos

mismos como estudiantes, dividido en la falta de orientación en el entorno

clínico, el vivir las prácticas clínicas como una pesadilla y la esperanza

durante la experiencia. También se presentan algunas propuestas de mejora.

Conclusión: Los resultados de este estudio han permitido describir el

fenómeno estudiado, revelando la percepción de los estudiantes sobre la

supervisión clínica y el efecto del contexto en el que se desarrolla esta

relación. Estos resultados servirán para evaluar cómo mejorar la supervisión

clínica, identificando un modelo innovador a seguir. Esta medida es esencial

para el desarrollo profesional de los estudiantes de enfermería.

Palabras clave: educación en enfermería; preceptoría; estudiantes de enfermería; enfermería.

Recebido: 06/09/2023

Aceito: 16/03/2024

Introdução

A nível mundial, diversos países têm-se interessado pelo tema de supervisão clínica em enfermagem, que é um apoio profissional aos estudantes. O seu objetivo é de ajudar os estagiários no desenvolvimento de habilidades e confiança profissional, socializá-los no ambiente clínico e, por conseguinte, fomentar a transferência de conhecimentos teóricos para a prática, assegurando assim mais bem cuidados aos pacientes. (1, 2) Afinal, “para que os formandos estejam devidamente preparados, necessitam de ser orientados e supervisionados”. (3) Os enfermeiros desempenham um papel importante nesse processo para o desenvolvimento da competência dos estudantes de enfermagem, atuando como fonte de apoio no contexto da prática clínica para reforçar o seu profissionalismo. (2, 3)

A maior parte das investigações sobre a supervisão clínica em enfermagem a nível internacional tem-se centrado nas experiências dos estudantes e supervisores clínicos, foram encontradas experiências positivas como resultado, por exemplo, o apoio dado aos estudantes pelos supervisores. E também experiências negativas, que funcionam como barreiras à educação e aprendizagem dos estudantes. Estas incluem um ambiente clínico inadequado; abuso de poder (experiências relacionadas com comportamentos abusivos); incompetência dos supervisores; falta de formação continua dos supervisores em competências formativas; falta de implementação de ferramentas estratégicas para facilitar a supervisão clínica (modelos inovadores de supervisão clínica); ausência de supervisores clínicos (falta de disponibilidade de supervisores que ainda não apoiam a aprendizagem); procedimentos de avaliação formativa curtos; e falta de reconhecimento formal dos papéis dos supervisores. A necessidade de implementação de modelos inovadores de supervisão clínica que permitam um processo estruturado e formal é uma preocupação em vários países do mundo. (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9)

A nível mundial, estão a ser elaborados modelos inovadores de supervisão clínica para estudantes de enfermagem e parteiras que consistem na colaboração entre as instituições envolvidas nesse processo (universidade e campo clínico) e a participação da tríade supervisor acadêmico, supervisor clínico e estudante, com a finalidade de promover a aprendizagem bem-sucedida nos estudantes, um ambiente clínico eficaz e compensador para a tríade e melhorar a saúde pública. (1, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16) De entre estes, o Modelo de Participação em Associação (PEM) é o mais experimentado e utilizado em vários países do mundo. Que consiste em cada membro da parceria, a tríade (supervisor acadêmico, supervisor clínico e estudante) ser responsável pela qualidade e eficácia das atividades de aprendizagem clínica, com um compromisso contínuo desde a planificação até à avaliação (15,16). As pesquisas mostram que a utilização dos modelos melhora o ambiente de aprendizagem clínica e a competência do supervisor. (11, 14, 15, 16)

Vários países africanos têm-se preocupado com a questão da supervisão clínica em enfermagem, como Gana, Quénia, Malawi, Uganda e África do Sul, que exploraram a experiência dos estudantes de enfermagem e dos supervisores clínicos em matéria de supervisão clínica. Estes estudos encontraram experiências positivas e negativas que influem na supervisão clínica. As experiências negativas mais frequentemente relatadas nos países africanos não diferem muito de outros países do mundo. No entanto, há questões que, em alguns países africanos, continuam a ser fatores que influenciam negativamente a supervisão clínica, tais como: falta de recursos humanos e falta de remuneração para os supervisores. Tendo em conta o que precede, é necessário procurar estratégias para melhorar a supervisão clínica e o apoio aos estudantes. E os enfermeiros educadores têm de receber formação contínua, planificar a supervisão clínica e o apoio de forma eficaz para promover graduados de enfermagem competente. (2, 3, 17, 18, 19, 20) Há evidências de que a supervisão clínica é uma perspectiva educacional complexa e dinâmica que pode ter tanto aspectos positivos como negativos. (1, 3, 21) Por isso, a experiência do estudante no campo clínico é deveras importante, uma vez que pode ter um impacto significativo na sua aprendizagem.

Moçambique é um país da África Oriental e Austral que se tornou independente em 1975, e em seguida foi devastado por uma guerra civil que terminou em 1992. (22) Depois destes longos períodos de guerras, a maioria dos principais técnicos de saúde deixou o país, resultando numa grave escassez de pessoal para satisfazer as necessidades neste campo. O governo moçambicano definiu como novas estratégias a formação de enfermeiros de níveis elementar e básico. Essas formações duraram por muitos anos. Em 1980, surgiu a necessidade de promoção de cursos complementares e de especialização em diferentes áreas da enfermagem. Ao mesmo tempo, foram estabelecidas carreiras técnico-profissionais de saúde, divididas em quatro níveis: elementar, básico, médio e médio especializado. (23) Em 2003, foi aprovada em Maputo a criação do primeiro Instituto Superior de Ciências de Saúde (ISCISA), com ensino superior em várias áreas de saúde, incluindo enfermagem. (23) Na atualidade, o país conta com três níveis de formação em enfermagem: médio, médio especializado e licenciatura. Para o técnico de enfermagem geral (médio), a duração é de 2 anos e para o técnico especializado (médio especializado) é de 1 ano e 6 meses, ambos com formação baseada em competências (FBC) “saber fazer”. Concentra-se no conhecimento específico, nas atitudes e nas habilidades necessárias para realizar o procedimento ou atividade. E para o grau de enfermeiro licenciado “enfermeiro A”, a formação tem duração de 4 anos e enfatiza a competência no desenvolvimento humano do aluno para o cuidado humanizado; o pensamento crítico do futuro profissional e a capacidade de intervir prontamente com conhecimento científico. (24) Em 2008, a Universidade Católica de Moçambique (UCM) iniciou a formação de enfermeiros de nível superior. O curso tem um período de duração de 4 anos, usando o método de ensino PBL (Problem Based Learning). (24) A supervisão clínica, todavia, é um processo informal, em que a Universidade contacta um técnico de enfermagem de nível médio ou médio especializado, consoante a área de práticas, sem formação contínua em matéria de supervisão e encarrega-o de supervisionar um grupo de estudantes. (24) Os docentes e a direção da Faculdade de Ciências de Saúde (FCS), da UCM, atuam como mentores para controlar o processo. (24) Ademais, em Moçambique há escassez de recursos humanos. Os profissionais de saúde existentes não podem cobrir o grande número dos estudantes que entram no campo clínico. Atualmente, um enfermeiro está para cada 2000 habitantes, (22) e a maioria é técnico.

Como referido no parágrafo anterior, nesta fase embrionária, os estudantes do ensino superior são supervisionados por enfermeiros técnicos. (24) De acordo com a teoria de Patricia Benner “de novato a experto”, a supervisão clínica é necessária para cada fase na formação do enfermeiro, e recomenda-se que os estudantes sejam orientados por enfermeiros competentes, mas não expertos, e guiados por programas de supervisão formal, para melhorar a satisfação dos estudantes e dos pacientes, bem como a qualidade organizacional. (25, 26) Não se encontraram antecedentes de estudos relacionados a este tema em Moçambique. Portanto, é relevante um estudo que explore as experiências dos estudantes de enfermagem em matéria de supervisão clínica no contexto local. O estudo tem como objetivo compreender as experiências dos estudantes do último ano do Curso de Enfermagem da UCM sobre a supervisão clínica prestada pelos técnicos de enfermagem, a fim de melhorar a educação e aprendizagem em enfermagem (supervisão clínica).

Metodología

Tipo de estudo

Neste estudo, utilizou-se o paradigma construtivista-qualitativo, (27) segundo o qual cada participante tem uma percepção subjetiva e um discurso sobre o fenômeno. Como desenho da pesquisa foi utilizada a fenomenologia, que é um método filosófico desenvolvido por Edmund Husserl (1859-1938), (28) que se preocupa com a forma como a coisa ou o fenômeno é vivenciado na perspectiva da primeira pessoa e descreve o significado comum, com o propósito de explicar a estrutura ou a essência da experiência vivida de um fenómeno na perspectiva da unidade de significado que é a identificação da essência de um fenómeno e a sua descrição precisa através da experiência vivida no quotidiano. (27, 29) Trata-se de uma fenomenologia descritiva, que consiste em explorar, analisar e descrever diretamente fenómenos particulares da forma mais livre possível. Os três passos da fenomenologia descritiva foram seguidos: (1) intuir; (2) analisar; e (3) descrever. Quando na primeira etapa, intuir, se imergiu totalmente no fenómeno em estudo, começou-se a conhecer o fenómeno descrito pelos participantes. Evitou-se qualquer crítica, avaliação ou opinião e prestou-se uma atenção rigorosa ao fenómeno em estudo tal como foi descrito; a segunda fase consiste numa análise fenomenológica, que consistiu em identificar a essência do fenómeno em estudo a partir dos dados obtidos e da forma como foram apresentados, à medida que as descrições foram sendo escutadas, começaram a surgir temas ou essências comuns; a terceira fase é a descrição fenomenológica, em que as descrições escritas e verbais do fenómeno foram recolhidas, classificadas e agrupadas. (29) Esta abordagem ajudou a responder à pergunta: quais são as experiências dos estudantes do último ano do Curso de Enfermagem da Universidade Católica de Moçambique sobre a supervisão clínica prestada pelos técnicos de enfermagem? E ao objetivo da pesquisa.

Amostra

Os participantes da pesquisa foram os estudantes do 4.º ano do Curso de Licenciatura em Enfermagem, já que eles iniciam as práticas clínicas no 2.° semestre do 1.° ano, nos setores de Medicina (Fundamentos de Enfermagem) no Hospital Central da Beira (HCB), para colocar em prática as habilidades básicas de enfermagem. E aumenta progressivamente, no 2.º ano os alunos têm estágio durante todo o ano, Primeiro semestre, estágio médico cirúrgico no HCB; segundo semestre, estágio em obstetrícia nos centros de saúde de Macurungo, Manga Mascarenha e Munhava (Beira-Sofala-Moçambique), o que significa que as horas de estágio são mais extensas. No 3.º ano primeiro semestre estágio de pediatria, urgência e psiquiatria no HCB; e no segundo semestre, estágio de saúde comunitária com famílias vulneráveis (que ocorre em um bairro suburbano) e no 4.º ano: o tempo de estágio é maior em um sistema pré-profissional: ou seja, 8 horas por dia e com turnos à noite, também estágio de supervisão onde os estudantes do 4.º ano acompanham os alunos do 1.º ano no estágio de fundamentos de enfermagem. E, portanto, os estudantes do 4.º ano têm mais experiências em supervisão clínica prestada por técnicos de enfermagem. Setenta e cinco por cento (75 %) das práticas é realizado no HCB, que é o segundo maior hospital do país e também está localizado no segundo maior centro populacional do país. (24) Os participantes foram selecionados por amostra intencional ou de conveniência, uma vez que o objetivo era escolher pessoas que vivenciaram o fenômeno em estudo. Já que a investigadora principal não se encontrava em Moçambique, mas teve, a dada altura, contacto com alguns estudantes, a mobilização foi feita por um assistente da investigação, um médico graduado pela UCM que não pertencia ao departamento de enfermagem e não tinha contacto com os estudantes do último ano, o papel do assistente de investigação consistiu apenas em aplicar conhecimentos informados e não tinha competência para compreender o contexto de formação do futuro profissional de enfermagem, tratando-se de um médico de clínica geral. Foram 104 estudantes, dos quais 36 eram do sexo masculino e os restantes do sexo feminino. Desta forma, garantiu-se a voluntariedade e a liberdade de participar no projeto.

A investigadora principal preparou uma apresentação em vídeo na qual relatou em pormenor o objetivo do estudo e as condições de participação totalmente voluntária, incluindo informações sobre o assistente e a investigadora responsável, e enviou para o assistente que de seguida encaminhou para o grupo de WhatsApp da turma. Seguiu a fase de recrutamento que culminou com 14 assinaturas de Consentimentos Informados (CI), aplicados presencialmente pelo assistente. O estudo contou com os seguintes critérios de inclusão: ser estudante do último ano de enfermagem da UCM- FCS; ter concluído o estágio final (estágio integral) e manifestar vontade de participar no estudo, formalizada pela assinatura do consentimento informado. O critério de exclusão consistia em não ter concluído o estágio final (estágio integral). Não se considerou o critério de exclusão, devido à pandemia de COVID-19, houve atraso no programa, todo o grupo, todavia se encontrava no estágio integral, 2.º semestre do 4.º ano, e a sua participação foi voluntária. Sem embargo, foram obtidas 10 entrevistas com saturação de informação. (27)

A recolha de dados foi através de entrevistas em profundidade, entre outubro de 2021 e fevereiro de 2022, com uma única pergunta: (27) Qual tem sido a sua experiência sobre a supervisão clínica prestada pelos técnicos de enfermagem durante a sua formação profissional? A entrevista foi feita em português e conduzida de forma online pela investigadora principal via plataforma Zoom. A conexão dos estudantes na plataforma aconteceu nos estabelecimentos da UCM- FCS, onde havia um tablet com acesso à internet. O assistente conectava o participante na plataforma e deixava-o na sala. Já que não foi a investigadora principal quem aplicou os CI, no início das entrevistas cada participante era solicitado a revisar os termos do formulário de CI assinado para o esclarecimento no caso de dúvidas. A duração das entrevistas variou aproximadamente 40 minutos a 3 horas.

Análise de dados

As 10 entrevistas foram analisadas utilizando as cinco etapas descritas por Colaizzi. Ei-las: 1) para se familiarizar com a informação, as transcrições foram lidas e as gravações foram ouvidas, repetidamente, para se obter uma compreensão profunda da experiência; 2) devolveu-se as transcrições originais, e as declarações significativas foram extraídas; 3) interpretou-se o significado de cada afirmação significativa; 4) significados foram organizados em conjuntos de categorias e subcategorias; e 5) uma descrição abrangente foi escrita. Fez-se bracketing, que segundo Husserl significa suspender ou colocar entre parênteses todo o julgamento do real (experiência do investigador), a fim de se concentrar na experiência descrita pelo participante, para chegar à essência do fenômeno. (27)Adicionalmente, o software Dedoose versão 9.0.46 foi utilizado para esta análise, a fim de garantir a utilização eficiente e rigorosa de toda a informação obtida neste estudo. (29)

Confiabilidade dos dados

Como se trata de um estudo qualitativo, quatro critérios de rigor foram assegurados: credibilidade, fiabilidade, confirmabilidade e transferibilidade. (29) Nesta pesquisa assegurou-se a credibilidade dos resultados do estudo da seguinte forma: após completar a análise e os resultados do discurso, a investigadora principal preparou uma apresentação, compartiu-a com o assistente e em seguida ele encaminhou-a para 9 participantes, e eles sentiram-se identificados com a dinâmica social exposta. (27, 29) Relativamente à fiabilidade, as entrevistas foram gravadas em áudio e vídeo e foram transcritas logo após a sua realização. As categorias e subcategorias emergiram da análise de conteúdo, confirmando assim que os resultados do estudo foram determinados pelas experiências dos entrevistados e não da investigadora. Para este fim, também foram tomadas notas de campo quando fosse necessário ao longo de todo o percurso de recolha de dados. Por último, se os resultados são apropriados ou transferíveis depende de os resultados serem aplicáveis a outro contexto. Por conseguinte, para dar a conhecer a outros autores se os resultados são aplicáveis ao seu contexto, esta investigação fornece descrições pormenorizadas dos participantes e do processo de recolha e análise de dados. (29)

Aspectos éticos

O estudo é uma resposta a uma situação real que atualmente afeta a formação de enfermeiros licenciados da UCM-FCS, daí o seu valor científico e social. O projeto de pesquisa foi aprovado pelo Comitê Ético-científico da Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, ID: 210715007, 2021. Foi solicitada e concedida a autorização do Reitor da UCM, do Director da FCS e da Coordenadora do Departamento de Enfermagem, de onde os participantes provêm. Os estudantes deram o seu CI para a participação voluntária na gravação em áudio e vídeo das entrevistas. Durante as entrevistas, o bem-estar dos participantes foi cuidadosamente monitorizado e acompanhado. Ninguém, exceto a investigadora e as suas supervisoras, teve acesso aos dados, para garantir a confidencialidade. Cada entrevistado foi identificado pela letra “P” (participante) e com um número.

Resultados

Características dos participantes

Os participantes do estudo foram 10 estudantes do último ano do Curso de Enfermagem, com idade entre 22 e 25 anos, todos sem filhos. Sete eram do sexo masculino, 9 eram solteiros, e também 7 eram da região centro do país e dominavam as línguas locais mais faladas no território que são Sena e Ndau, (30) e os outros 3 eram do norte de Moçambique. Nove deles não trabalhavam antes de ingressar na Universidade, e mais da metade não estavam empregados. Por fim, 9 deles não tinham atraso curricular.

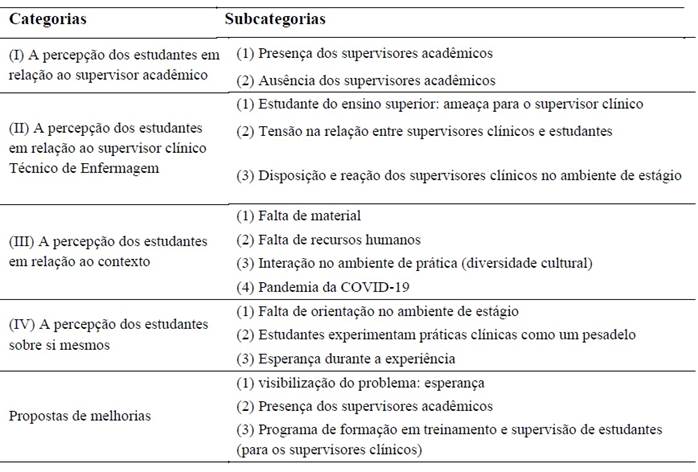

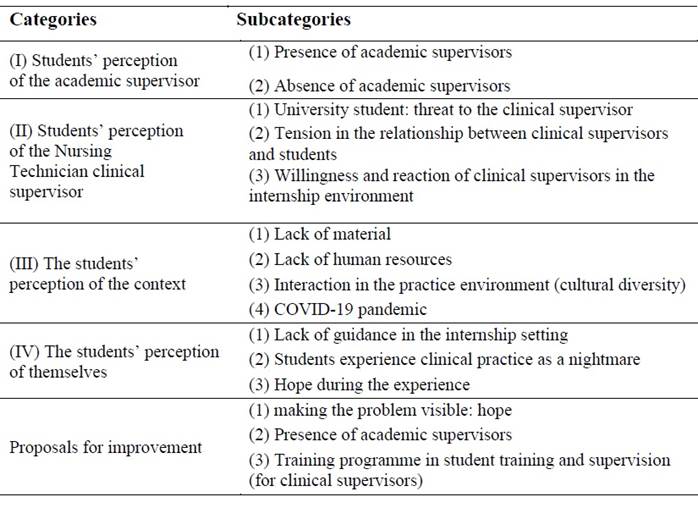

Surgiram da análise das entrevistas quatro grandes categorias, suas respectivas subcategorias e propostas de melhorias, relacionadas com a percepção dos estudantes sobre a supervisão clínica, como se pode observar de forma detalhada na Tabela 1.

Tabela 1: Categorias, subcategorias e propostas melhorias

A percepção dos estudantes em relação ao supervisor acadêmico

O supervisor acadêmico neste estudo, refere-se ao docente empregado na instituição de ensino (Universidade), escolhido para supervisionar e facilitar a aprendizagem dos estagiários na prática clínica. A maioria dos participantes relatou boas experiências sobre o acompanhamento dos supervisores acadêmicos nos primeiros dois anos de formação. A presença dos supervisores acadêmicos foi tida como algo positivo por os supervisores e estudantes serem do mesmo nível, por haver respeito dos profissionais para com os estudantes e por existir enquadramento de conhecimento teórico à prática. Tal como mencionou um dos participantes:

Graças a Deus que no 1º e 2º ano tivemos supervisão (…), independentemente de serem estudantes ou profissionais da UCM, mas ajudou muito porque com as mesmas pessoas falávamos a mesma língua (P5).

Por outro lado, alguns participantes relataram que, a partir do 3° ano, havia ausência dos supervisores acadêmicos e às vezes se faziam presentes somente como mentores. Os entrevistados referiram que a ausência se devia ao menor número de docentes que, como consequência, não conseguia suprir o número cada vez mais elevado de estudantes. No momento do estágio, os estudantes referem sentir-se sozinhos, sem orientação sobre o que vão fazer no terreno, o que significa que não alcançam os objectivos do estágio e, consequentemente, sentem que a qualidade da sua formação é prejudicada pela supervisão. Um dos participantes fez saber que:

A partir do 2.° ou 3.° ano (…) a supervisão por parte dos docentes tem sido um pouco escassa, é normal uma semana só duas vezes (…) e não tem sido a tempo inteiro (…) somente para controlar as presenças, perguntar aos chefes ou enfermeiros que são nossos supervisores, sobre como que vai o estágio (P9).

A percepção dos estudantes em relação ao supervisor clínico

O supervisor clínico técnico de enfermagem de nível superior (TENS) neste estudo, é um enfermeiro técnico profissional empregado na instituição hospitalar (campo clínico), com uma duração de formação de 2 anos para o nível médio e de 1 ano e 6 meses para o médio especializado, que supervisiona o estudante de Licenciatura em Enfermagem num ambiente clínico. Entretanto, há que se destacar que a maioria dos entrevistados disse que porque os supervisores clínicos são TENS, mostraram algumas dificuldades na supervisão dos estudantes de nível superior, tais como a falta de esclarecimento de dúvidas, e sentiam-se ameaçados por os estudantes serem do ensino superior. Um dos participantes disse:

Isto dificultava um pouco, porque é sabido que um técnico para supervisionar um superior tem limitações, por mais experiência que a pessoa tenha na prática, mas tem certa teoria como um superior tem e ele não viu (…) e também eles pensam no sentido de que vocês não sabem nada, agora que estamos a vos supervisionar como básicos depois (…) virão aqui para serem nossos chefes e com o salário mais alto (…) então eu não tenho aquela tendência de poder vos supervisionar (P5).

Isto gerava tensão na relação entre supervisores clínicos e estudantes.

Os participantes relataram ainda que os supervisores clínicos, em retaliação à ameaça, contradiziam o conhecimento teórico que os estudantes traziam da Universidade para aplicar no campo clínico. Ademais, a falta de remuneração dos supervisores clínicos tornava-os desmotivados para acompanhar os estudantes. Os entrevistados também notaram que a má orientação por parte de alguns dos supervisores clínicos se devia à falta de formação contínua em supervisão de estudantes. Como foi referido por um dos participantes:

Eu estava a inserir catéter venoso, falhei (…), mas o meu supervisor não teve a colaboração, paciência de dizer (…), veja como eu vou pegar o catéter e como vou inserir para que, da próxima, faça o mesmo (…) ele ficou zangado comigo e disse que esses estudantes não sabem nada, que vêm aqui passear (P1).

Os entrevistados salientaram que, ainda em resposta à ameaça e à falta de remuneração, os supervisores clínicos mostravam má disposição e reação no ambiente de prática, isto é, comportamentos agressivos e abusivos, como a falta de respeito, exclusão da equipe de trabalho e resistência às iniciativas dos estudantes por serem do ensino superior. Conforme foi mencionado por um dos participantes:

Você um mês num setor obviamente (…) passa um maltrato perigoso, porque conversam entre eles (os supervisores clínicos), então quando não vai com a sua cara conversam com outros colegas (P6).

A percepção dos estudantes em relação ao contexto

O contexto neste estudo, refere-se ao ambiente clínico onde os estudantes podem aprender e desenvolver habilidades clínicas de enfermagem numa situação da vida real, sob a orientação de um profissional experiente (31). Alguns participantes ao relatarem a sua experiência mencionaram a falta de material como uma das razões para o mal atendimento aos pacientes. Notaram também, com desagrado, que os profissionais de saúde já não seguiam as regras de assepsia. Um dos entrevistados revelou:

Em alguns setores, devido à falta de material, as mães tinham de comprar (…), e às vezes compartilhavam seringas, e por falta de condições, catéteres duravam mais de 2 ou 3 semanas, isso pode causar infecção na criança (…), e a pandemia da COVID-19 afetou (…), houve tempo que paramos por mais de 5 meses, ano 2020, quando voltamos no 3°, 4° ano foi tudo às pressas, até estágio. Talvez poderíamos ter a supervisão dos docentes, mas não tinham como (…) há módulos que fazíamos em uma semana (P10).

Outrossim, alguns entrevistados mencionaram a falta de recursos humanos. Há menor número de enfermeiros licenciados e TENS no campo de estágio, que acabam sobrecarregados e, portanto, dando muito trabalho aos estudantes do 3º e 4º anos sob justificativa de que já deveriam ser experientes em alguns procedimentos. Um dos participantes atestou:

Os profissionais próprios de enfermagem são poucos para suprir todos os alunos que entram (…), e acabam por nos pressionar muito, dando-nos toda a carga (…), tipo temos que fazer todas as atividades (P2).

Os participantes relataram tanto experiências positivas como negativas sobre a diversidade cultural no ambiente de prática. Alguns afirmaram que os supervisores clínicos de alguns setores mantinham as suas culturas em reserva, sendo neutros, enquanto outros utilizavam a sua língua materna para criticar os estudantes. Para estudantes poliglotas, foi uma boa experiência. Para outros, não foi fácil estagiar num hospital com profissionais de culturas diferentes e que interagiam melhor e prestavam mais atenção ao estudante que era do mesmo grupo étnico. Alguns entrevistados disseram:

A minha cultura ajudou e ajuda-me muito (…), porque eu entendo, Ndau, Sena, há profissionais que conversam comigo, eu respondo-lhes e depois, se a conversa não é relevante, não é prolongada, eles percebem que eu entendo (P6).

Os supervisores se interessam mais e ficam muito mais próximos daqueles estudantes que são do mesmo grupo étnico, por exemplo falo Guitonga com um paciente, supervisor que é de Inhambane percebe que é conterrâneo, aproxima-se, tornam-se amigos e dão-lhe mais tempo de atenção em comparação com os colegas que são de um grupo étnico diferente (P9).

Por fim, alguns participantes relataram que a pandemia da COVID-19 foi um impacto positivo no seu estágio porque os supervisores clínicos estiveram mais próximos e atenciosos aos estudantes. Por outro lado, alguns relataram experiências negativas porque tiveram pouco tempo nas práticas clínicas. Alguns dos entrevistados asseveraram:

A pandemia da COVID-19 afetou de maneira positiva, porque temos que prestar muita atenção na realização de qualquer atividade (…) e os profissionais supervisores ficaram um pouco mais atenciosos e próximos dos estudantes, (…) esclarecendo as dúvidas, pensavam que talvez poderia chegar a inspeção e os estagiários a realizarem procedimentos sem a presença deles (P9).

Alguns participantes referiram ainda que a forma como os pacientes portadores de VIH são tratados é muito diferente dos outros e que existe muita estigmatização, os procedimentos são malfeitos a estes pacientes, são maltratados e o que pode até levar à morte. Por outro lado, dependendo do seu estatuto social, os pacientes de baixo estatuto são menos respeitados e maltratados, como relataram os entrevistados:

Eu vi uma senhora que tinha 33 anos e que era soropositiva há 5 anos e já estava a fazer TARV (tratamento antirretroviral), (...) e fez uma histerectomia, (...), a sutura em si, é lamentável, e os outros profissionais de saúde acabaram comentando (...), sutura mal feita, abriram demasiado o abdómen, foi desde a sínfise púbica até à região hipogástrica, que é o processo xifoide, abriram o abdómen todo (...). Isso mostra que um paciente soropositivo (...) é tratado de forma muito diferente (P5).

Também me lembro da parte das visitas, (...) quando chega alguém com calças e casaco (classe alta), até às 10 horas pode entrar para visitar o familiar doente, mas quando é qualquer outra pessoa não pode entrar (P7).

A percepção dos estudantes sobre si mesmos

Os estudantes neste estudo, refere-se aos formandos do curso de Licenciatura em Enfermagem da UCM-FCS no campo clínico. Os participantes relataram que se sentiram muito desorientados durante as práticas clínicas, devido à falta de acompanhamento dos supervisores acadêmicos, o que contribui para o não cumprimento dos objetivos do estágio. Para os entrevistados, isso coloca em causa a qualidade da formação dos futuros enfermeiros licenciados graduados pela UCM, bem como por outras instituições. Como alguns dos participantes referiram:

Às vezes os supervisores dos hospitais dão-nos tarefas que não têm haver com enfermagem, enquanto nós estaríamos a aprender técnicas que eles sabem e que poderiam nos ensinar, mas (…) quando não está agente de serviço, estudantes vão limpar chão, carregar água, caixas, onde fazemos tudo isso podem passar duas horas (P10).

Ouvimos dizer que no próximo ano vão introduzir o método clássico, vai ser o pior (...) para a UCM, mesmo com o PBL agora não estão a conseguir controlar os estudantes, a qualidade não é como de antes, mesmo metade de nós, estamos a sair com um pouco daquela qualidade, devido à supervisão que temos, mas a partir do 3.º ano para baixo nada (P6).

Ademais, os estudantes consideraram os momentos de prática clínica como um pesadelo, devido ao tratamento dado pelos supervisores clínicos, que os desmotivava e não os fez usufruir da aprendizagem tanto quanto deveriam. Tal como referido por um dos participantes:

Cada situação no ambiente de estágio é triste, você só fica querendo horas de saída deste setor (…), porque você chega, os enfermeiros entendem te insultam (P6).

Os participantes afirmaram que mesmo que sejam desmotivados e experimentem as práticas clínicas como momentos desagradáveis, eles têm a esperança de um dia se formarem, por isso se dedicavam muito no estágio e, como consequência, ganhavam mais experiência e habilidades nas práticas. Um dos entrevistados revelou:

Temos suportado muito desde o 1.° ano, não é hoje que já estamos no fim, apesar de que dizem que a bagagem pesa muito no final, para descarregá-la é difícil, não há coisas fáceis, por isso às vezes seguramos o coração, vamos ao vestiário choramos e passa (...) é para contar no futuro (P6).

Propostas de melhorias

Algumas propostas de melhorias surgiram dos participantes com vista uma supervisão clínica de qualidade e aprendizagem bem-sucedida dos estudantes de enfermagem. Os participantes sugeriram que tem de haver a presença de supervisores acadêmicos no ambiente de estágio porque eles ensinam a teoria e sabem como acompanhar cada estudante. Um dos participantes afirmou:

Para mim, deveríamos ter um acompanhamento desde o 1.º até ao 4.º ano, os docentes que nos dão as aulas teóricas deveriam ser os mesmos até no nosso campo prático, (...) eles já nos conhecem desde a sala de aula que tal aluno requer muita atenção (P8).

Os participantes propuseram ainda a implementação de algumas estratégias para melhorar o processo de supervisão clínica, como um programa de formação para supervisores clínicos TENS. Além disso, profissionais de saúde e estudantes deveriam informar-se sobre a cultura da comunidade em que irão trabalhar, de modo a ter informação fundamental. Alguns dos entrevistados atestaram:

Dizem que quem educa deve ser um exemplo para motivar o aluno (P7).

Os supervisores deveriam ter formação contínua em termos de supervisão, porque nem todos sabem como supervisionar. Poderiam aprender a ser mais pacientes em relação a esse processo (…) e procurar saber exatamente qual é a língua que lá se fala. Pelo menos para conhecer coisas básicas, isso pode ajudar na relação com os pacientes (P8).

Por fim, as entrevistas permitiram que os participantes desabafassem com relação às suas experiências cotidianas sobre a supervisão durante as práticas clínicas, conforme um dos entrevistados revela:

Depois dessa conversa me sinto um pouco mais aliviado porque ninguém agora aparece para perguntar, (…) como foi o estágio? Desde o início até aqui, tem muita coisa que nós precisamos tirar (…) e você acabou de fazer isso (…) por me escutar (P9).

Discussão

A supervisão clínica é deveras importante na carreira de enfermagem. (1, 2) Existem alguns estudos internacionais que abordam a questão a partir das experiências dos estudantes, bem como dos supervisores clínicos, a nível universitário. (1, 3, 5, 7, 8, 32) Neste estudo, procuramos o diferente, explorando as experiências dos estudantes de nível de licenciatura sobre a supervisão clínica prestada pelos TENS.

A nível mundial há poucas pesquisas sobre as experiências dos enfermeiros auxiliares, em Moçambique conhecidos como técnicos de enfermagem, em supervisão clínica, dado que eles exercem alguma função no processo. Na Austrália, o papel do enfermeiro auxiliar é pertinente, quando o supervisor clínico nomeado pela universidade/campo clínico não faz parte da enfermaria ou quando pacientes são designados aos estagiários. (33) Ambos são continuamente capacitados para tal. Mesmo assim, o enfermeiro auxiliar é considerado educador clínico informal. (33) Solicita-se-lhe feedback formativo sobre o desempenho dos estudantes ao longo do seu turno, mas não participa na avaliação formal deles. (33) Diferente da Austrália, em Moçambique os técnicos de enfermagem desempenham um papel importante nas práticas clínicas dos estudantes, acompanhando-os durante o processo, mas não tem uma formação contínua para tal, o que faz com que o acompanhamento seja insatisfatório para os estudantes. Em Uganda, os enfermeiros não licenciados também participam na supervisão clínica dos estudantes de licenciatura. Um estudo realizado num hospital regional de Uganda sobre as percepções dos enfermeiros em exercício (TENS) acerca da sua preparação para a supervisão clínica de estudantes de licenciatura em enfermagem, mostra que os TENS se sentem preparados para a supervisão clínica de estudantes de licenciatura em enfermagem, sem embargo necessitam de apoio para desempenhar o papel de supervisor clínico de estudantes de licenciatura em enfermagem. (34)

Relativamente à supervisão clínica prestada por enfermeiros licenciados, foi encontrada uma referência a descrever como uma experiência positiva o apoio dos supervisores clínicos aos estudantes, que os ajuda a aliviar o medo por ser o seu primeiro contacto com pacientes. (1) Uma outra referência foi identificada e descrevia a insegurança laboral como a razão da supervisão clínica inadequada, ou seja, os supervisores clínicos sentiam-se ameaçados por serem do mesmo nível dos estudantes e ressentidos pela falta de remuneração. (3) Contudo, neste estudo, a ameaça era o facto de os estudantes serem universitários.

Um estudo constatou uma tensão na relação entre os supervisores clínicos e os estudantes (confusão educativa), em que os supervisores clínicos forçavam os estudantes a cumprir com as suas exigências e, por falta de clareza nos deveres dos estudantes, não clarificavam as dúvidas sobre as práticas clínicas a ser realizadas, ignorando por completo as suas preocupações. (7) É importante referir que, neste estudo, também se obtiveram respostas idênticas, no entanto, por razões diferentes: falta de remuneração e limitações na supervisão de estudantes do ensino superior. No mais, não havia programas de formação contínua em matéria de supervisão clínica.

Um estudo realizado na África do Sul, com o objetivo de “explorar as experiências dos estudantes de licenciatura em enfermagem no âmbito de supervisão clínica” também foram encontradas experiências negativas, tais como comportamentos abusivos, isto é, “abuso de poder” no campo clínico. (1) Outrossim, um estudo realizado no Irão com o objetivo de “explicar as experiências dos estudantes de enfermagem iranianos em relação ao seu ambiente de aprendizagem clínica” também se referiu às dificuldades durante o estágio clínico, como a exclusão dos estudantes da equipa de trabalho. (7) Assim como a resistência às iniciativas dos estudantes, que era um empecilho para o empoderamento dos estudantes nas práticas clínicas.

Também foram encontrados estudos que revelam a comunicação e a coordenação inadequadas entre as Universidades e as instituições de prática, (6) bem como a ausência dos supervisores académicos no ambiente clínico devido ao número inadequado de pessoal. (32) Os relatos apresentados neste estudo demonstraram que, esses aspetos dificultavam o processo de aprendizagem dos estudantes.

Os recursos materiais são importantes para a educação e aprendizagem em enfermagem, porque ajudam os estudantes a tornar-se competentes. A falta destes materiais pode fazer com que os estudantes se sintam perdidos, sem auxílio. (32) Um estudo sobre o ambiente clínico revelou que na falta de recursos materiais, os estudantes sentiram-se desamparados, sem apoio. (18) Ademais, os supervisores clínicos executavam as técnicas de assepsia inadequadamente. Alguns estudos internacionais mostram ainda que existe escassez de recursos humanos no contexto clínico, (3, 32) todavia, há maior número de estagiários, o que pode levar a um acompanhamento menos abrangente e, desta maneira, afetando a aprendizagem dos estudantes. (32, 35, 36)

Na mesma senda, um estudo australiano sobre “fatores que afetam a aprendizagem clínica de estudantes de diferentes origens culturais e linguísticas” (37) revelou que existia discriminação de supervisores contra estudantes. Os supervisores conversavam entre eles na sua língua materna enquanto supervisionavam os estudantes, o que acabava sendo experiências negativas de aprendizagem para os estudantes. (37) O presente estudo revelou que havia boas relações entre supervisores clínicos e estudantes do mesmo grupo étnico, o que configurava exclusão dos estagiários de outras etnias.

A pandemia da COVID-19 teve um impacto notável em todo o mundo, especialmente no setor da saúde. Já que se trata de um tema novo, não há muitos estudos a respeito. Um estudo da Bélgica revelou que a maioria dos participantes se sentia apoiado pelos supervisores acadêmicos e clínicos devido à pandemia. (38) No entanto, neste estudo, a atenção centra-se nos supervisores clínicos TENS em relação aos estudantes. Por outro lado, os estudantes reclamaram do curto tempo da prática clínica causado pela pandemia, o que também contribuiu de forma negativa na sua aprendizagem. De referir, porém, encontrou-se um artigo de discussão que aborda a relevância da colaboração entre ambas as instituições (clínica e educativa) para uma melhor supervisão clínica dos estudantes durante a pandemia da COVID-19. (39)

A falta de acompanhamento dos supervisores acadêmicos durante o estágio pode levar os estudantes a aprender procedimentos inadequadamente e a perder o interesse pela profissão. (3) Um estudo feito em Malawi revelou que alguns estudantes eram obrigados a realizar atividades rotineiras não relacionadas com a enfermagem durante o estágio, o que dificultava o seu processo de aprendizagem. (32) No presente estudo, tais comportamentos fazem com que os estudantes não alcancem as metas desejadas. Fazem-nos também acreditar que a qualidade de formação de enfermeiros licenciados está a diminuir.

O presente estudo também trouxe novos resultados: os estudantes consideraram as práticas clínicas um tormento devido ao ambiente clínico inadequado. Ainda assim, eles tinham a esperança de um dia se formar, por isso se focavam no estágio e em ganhar mais habilidades. Ademais, com este estudo, os entrevistados ficaram esperançosos nas mudanças para estudantes vindouros. Acharam este estudo extremamente importante para o ensino e aprendizagem em enfermagem em Moçambique e sugeriram que os supervisores acadêmicos acompanhassem os estudantes durante os estágios e que os supervisores clínicos TENS fossem capacitados em matéria de supervisão clínica.

Constituiu limitação para esta pesquisa a falta dos pareceres dos supervisores clínicos, dado que a investigadora principal não se encontrava em Moçambique. Portanto, espera-se que as investigações futuras explorem os pontos de vista dos supervisores acadêmicos e clínicos. Ainda neste estudo, os entrevistados relataram que havia discriminação contra pacientes soropositivos com base na classe social no contexto clínico. Os pacientes de classe baixa eram menos respeitados e mal atendidos. Por conseguinte, sugere-se também uma pesquisa futura sobre este tema no âmbito hospitalar.

Conclusão

O objetivo do presente estudo consistiu em: descrever as experiências dos estudantes do último ano do Curso de Enfermagem da Universidade Católica de Moçambique sobre a supervisão clínica prestada pelos técnicos de enfermagem, os resultados revelaram que apesar dos estudantes terem tido uma experiência positiva com a presença de supervisores acadêmicos nos primeiros dois anos de formação e com o apoio de supervisores clínicos durante o estágio, eles passaram por muitos desafios no campo clínico, que a dada altura afetaram negativamente a sua aprendizagem, como a ausência de supervisores acadêmicos durante os últimos dois anos de formação, a má relação com os supervisores clínicos, a falta de recursos humanos e materiais, a diversidade cultural no ambiente de prática e a pandemia da COVID-19. O que demonstra que muitos aspetos no ambiente de aprendizagem clínica têm de ser melhorados. A Faculdade de Ciências de Saúde da Universidade Católica de Moçambique, especialmente o Departamento de Enfermagem, precisa de ter um modelo inovador de supervisão clínica dos estudantes, que implica mais participação dos supervisores acadêmicos no ambiente das práticas clínicas e formação contínua dos supervisores clínicos em matéria de supervisão dos estudantes, apesar da sua enorme experiência no campo.

Referências bibliográficas:

1. Donough G, Van der Heever M. Undergraduate nursing students’ experience of clinical supervision. Curationis. 2018;41(1): a1833. doi: 10.4102/curationis.v41i1.1833

2. Alhassan A, Duke M, Phillips NM. Nursing students’ satisfaction with the quality of clinical placement and their perceptions of preceptors competence: A prospective longitudinal study. Nurse Educ Today. 2024;133:106081. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2023.106081

3. Kaphagawani NC, Useh U. Clinical supervision and support: Exploring pre-registration nursing students’ clinical practice in Malawi. Ann Glob Health. 2018;84(1):100-109. doi: 10.29024/aogh.16

4. Pitkänen S, Kääriäinen M, Oikarainen A, Tuomikoski AM, Elo S, Ruotsalainen H, et al. Healthcare students’ evaluation of the clinical learning environment and supervision – a cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today. 2018;62:143-149. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2018.01.005

5. Kalyani MN, Jamshidi N, Molazem Z, Torabizadeh C, Sharif F. How do nursing students experience the clinical learning environment and respond to their experiences? A qualitative study. BMJ Open. 2019;9:e028052. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2018-028052

6. Celma-Vicente M, López-Morales M, Cano Caballero-Gálvez MD. Analysis of clinical practices in the Nursing Degree: Vision of tutors and students. Enfermería Clínica (English Edition). 2019;29(5):271-279. doi: 10.1016/j.enfcle.2018.04.006

7. Aliafsari Mamaghani E, Rahmani A, Hassankhani H, Zamanzadeh V, Campbell S, Fast O, et al. Experiences of Iranian Nursing Students Regarding Their Clinical Learning Environment. Asian Nurs Res (Korean Soc Nurs Sci). 2018;12(3):216-222. doi: 10.1016/j.anr.2018.08.005

8. Mathisen C, Bjørk IT, Heyn LG, Jacobsen TI, Hansen EH. Practice education facilitators perceptions and experiences of their role in the clinical learning environment for nursing students: a qualitative study. BMC Nurs. 2023;22:165. doi:10.1186/s12912-023-01328-3

9. Donough G. Nursing students’ experiences of clinical assessment at a university in South Africa. Health SA. 2023;28:2161. doi: 10.4102/hsag.v28i0.2161.

10. DeMeester DA, Hendricks S, Stephenson E, Welch JL. Student, preceptor, and faculty perceptions of three clinical learning models. Journal of Nursing Education. 2017;56(5):281-286. doi: 10.3928/01484834-20170421-05

11. Grealish L, van de Mortel T, Brown C, Frommolt V, Grafton E, Havell M, et al. Redesigning clinical education for nursing students and newly qualified nurses: A quality improvement study. Nurse Educ Pract. 2018;33:84-89. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2018.09.005

12. McLeod C, Jokwiro Y, Gong Y, Irvine S, Edvardsson K. Undergraduate nursing student and preceptors’ experiences of clinical placement through an innovative clinical school supervision model. Nurse Educ Pract. 2021;51:102986. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2021.102986

13. Nursing & Midwifery Council. Standards for education and training (Internet). Londres: Nursing & Midwifery Council; 2018. Disponível em: https://www.nmc.org.uk/standards-for-education-and-training/

14. Rusch L, Beiermann T, Schoening AM, Slone C, Flott B, Manz J, et al. Defining Roles and Expectations for Faculty, Nurses, and Students in a Dedicated Education Unit. Nurse Educ. 2018;43(1):14-17. doi: 10.1097/NNE.0000000000000397

15. Schaffer MA, Schoon PM, Brueshoff BL. Creating and sustaining an academic-practice Partnership Engagement Model. Public Health Nurs. 2017;34(6):576-584. doi: 10.1111/phn.12355

16. Tang FWK, Chan AWK. Learning experience of nursing students in a clinical partnership model: An exploratory qualitative analysis. Nurse Educ Today. 2019;75:6-12. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2019.01.003

17. Aryere MT. Assessment of factors influencing the quality of clinical supervision of nursing and midwifery students at the 37 military hospital (Internet). Afribary; 2018. Disponível em: https://afribary.com/works/assessment-of-factors-influencing-the-quality-of-clinical-supervision-of-nursing-and-midwifery-students-at-the-37-military-hospital

18. Hester CdS. The clinical environment: A facilitator of professional socialisation. Health SA. 2019;24:a1188. doi: 10.4102/hsag.v24i0.1188.

19. Kavili JN. The impact of clinical nurse instructor’s practices on clinical performance among bachelor of science in nursing students in Kenya (Tese de graduação). Kenya; 2020. Disponível em: https://repository.kemu.ac.ke/bitstream/handle/123456789/917/JULIAN%20NTHULE%20KAVILI%20THESIS.Pdf?Sequence=1&isallowed=y

20. Mubeezi MP, Gidman J. Mentoring student nurses in Uganda: A phenomenological study of mentors’ perceptions of their own knowledge and skills. Nurse Educ Pract. 2017;26:96-101. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2017.07.010

21. Rojo J, Ramjan LM, Hunt L, Salamonson Y. Nursing students′ clinical performance issues and the facilitator’s perspective: A scoping review. Nurse Education in Practice. 2020;48:102890. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2020.102890

22. Ivo Garrido P. WIDER Working Paper 2020/131-Saúde, desenvolvimento e factores institucionais: o caso de Moçambique. 2020. Disponível em: https://www.wider.unu.edu/sites/default/files/Publications/Working-paper/PDF/wp2020-131-PT.pdf

23. Monjane LJ, Barduchi Ohl RI, Barbieri M. A formação de enfermeiros licenciados em Moçambique. Rev. Iberoam. Educ. Investi. Enferm. 2013;3(4):20-28. Disponível em: https://www.enfermeria21.com/revistas/aladefe/articulo/87

24. Casapía GZ, Vieira MMS. Formação em Enfermagem com Aprendizagem Baseada em Problemas (PBL). O caso da Universidade Católica de Moçambique (Tese de graduação). Porto: Universidade Católica Portuguesa; 2016. Disponível em: https://repositorio.ucp.pt/bitstream/10400.14/24195/1/Tese-GZC-Final%2001.pdf

25. Benner P. From Novice to Expert. The American Journal of Nursing. 1982; 82(3):402-407. Disponível em: https://journals.lww.com/ajnonline/citation/1982/82030/from_novice_to_expert.4.aspx#ContentAccessOptions

26. Howard ED. Fostering Excellence in Professional Practice with Mentorship. Journal of Perinatal and Neonatal Nursing. 2020;34(2):104-105. doi: 10.1097/JPN.0000000000000477

27. Creswell JW. 3ª ed. Qualitative Inquiry & Research Design. Thousand Oaks: SAGE; 2013.

28. Sanguino NC. Fenomenología como método de investigación cualitativa: preguntas desde la practica investigativa. Revista Latinoamericana de Metodología de la Investigación Social. 2021;20(10):7-18. Disponível em: http://www.relmis.com.ar/ojs/index.php/relmis/article/view/fenomenologia_como_metodo

29. Rinaldi Carpenter D. Phenomenology as a Method. En Streubert HJ, Rinaldi Carpenter D, editors. 5ª ed. Qualitative Research in Nursing. Hong Kong: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2011, p. 72-94.

30. Instituto Nacional de Estatística. Estatísticas da Cultura 2018 (Internet). 2018. https://acortar.link/kpXwl3

31. Muthathi IS, Thurling CH, Armstrong SJ. Through the eyes of the student: Best practices in clinical facilitation. Curationis. 2017;40(1):e1-e8. doi: 10.4102/curationis.v40i1.1787.

32. Mbakaya BC, Kalembo FW, Zgambo M, Konyani A, Lungu F, Tveit B, et al. Nursing and midwifery students’ experiences and perception of their clinical learning environment in Malawi: a mixed-method study. BMC Nurs. 2020;19:87. doi: 10.1186/s12912-020-00480-4

33. Rebeiro G, Evans A, Edward K leigh, Chapman R. Registered nurse buddies: Educators by proxy? Nurse Education Today. 2017;55:1-4. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2017.04.019

34. Drasiku A, Gross JL, Jones C, Nyoni CN. Clinical teaching of university-degree nursing students: are the nurses in practice in Uganda ready? BMC Nurs. 2021;20:4. doi: 10.1186/s12912-020-00528-5

35. Abuosi AA, Kwadan AN, Anaba EA, Daniels AA, Dzansi G. Number of students in clinical placement and the quality of the clinical learning environment: A cross-sectional study of nursing and midwifery students. Nurse Educ Today. 2022;108: 105168. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2021.105168

36. Arkan B, Ordin Y, Yılmaz D. Undergraduate nursing students’ experience related to their clinical learning environment and factors affecting to their clinical learning process. Nurse Educ Pract. 2018;29:127-132. doi: 10.1016/j.nepr.2017.12.005

37. Hari R, Geraghty S, Kumar K. Clinical supervisors’ perspectives of factors influencing clinical learning experience of nursing students from culturally and linguistically diverse backgrounds during placement: A qualitative study. Nurse Educ Today. 2021;102:104934. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104934

38. Ulenaers D, Grosemans J, Schrooten W, Bergs J. Clinical placement experience of nursing students during the COVID-19 pandemic: A cross-sectional study. Nurse Educ Today. 2021;99: 104746. doi: 10.1016/j.nedt.2021.104746

39. O’Donnell C, Markey K, Murphy L, Turner J, Doody O. Cultivating support during COVID-19 through clinical supervision: A discussion article. Nurs Open. 2023;10(8):5008-5016. doi: 10.1002/nop2.1800

Disponiblidade de dados: O conjunto de dados que dá suporte aos resultados deste estudo está disponível mediante solicitação ao autor correspondente.

Contribuição de autores (Taxonomia CRediT): 1. Conceitualização; 2. Curadoria de dados; 3. Análise formal; 4. Aquisição de financiamento; 5. Pesquisa; 6. Metodologia; 7. Administração do projeto; 8. Recursos; 9. Software; 10. Supervisão; 11. Validação; 12. Visualização; 13. Redação: esboço original; 14. Redação: revisão e edição.

C. S. N. contribuiu em 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14; F. M. D. em 1, 6, 7, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14; C. L. R. em 1, 6, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14.

Editora científica responsável: Dra. Natalie Figueredo.

10.22235/ech.v13i1.3665

Original Articles

Undergraduate Nursing Students’ Experiences of Clinical Supervision at a University in Mozambique

Experiências de estudantes do curso de licenciatura em enfermagem sobre supervisão clínica em uma universidade de Moçambique

Experiencias de estudiantes de licenciatura en enfermería sobre la supervisión clínica

en una universidad de Mozambique

Cristina Simão Nota1, ORCID 0000-0002-0441-9816

Francisca Márquez-Doren2, ORCID 0000-0001-8093-4687

Camila Lucchini-Raies3, ORCID 0000-0001-5704-9778

1 Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Chile

2 Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Chile

3 Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile, Chile, [email protected]

Abstract:

Objective: To describe the experiences of final year nursing students at

the Catholic University of Mozambique regarding the clinical supervision done

by nursing technicians.

Method: A qualitative-phenomenological study carried out with final year

nursing students at the Catholic University of Mozambique. The in-depth

interview was the technique used to collect data, which was analyzed using

Content Analysis.

Results: The results were divided into four main categories that emerged

from the analysis of the interviews and are related to 1) the students'

perception of the academic supervisor, highlighted by the presence and absence

of teaching staff in the clinical setting; 2) the clinical supervisor made

explicit by the nursing technical supervisors, with subcategories on the higher

level student as a threat to the technical nurse, tension in the relationship

between clinical supervisors and students, disposition and reaction of clinical

supervisors; 3) the context, represented by the lack of material and human

resources, cultural diversity and the COVID-19 pandemic; and 4) the perception

about themselves as students, divided into lack of orientation in the clinical

setting, living the clinical practice as a nightmare and hope during the

experience. Some proposals for improvement are also presented.

Conclusion: The results of this study have helped to describe the

phenomenon studied, revealing the students’ perception about clinical supervision

and the effect of the context that this relationship develops. These results

will help to evaluate how to improve clinical supervision by identifying an

innovative model to follow. This action is essential for the professional

development of nursing students.

Keywords: nursing education; preceptorship; nursing students; nursing.

Resumo:

Objetivo: Descrever as experiências dos

estudantes do último ano do Curso de Enfermagem da Universidade Católica de

Moçambique sobre a supervisão clínica prestada pelos técnicos de enfermagem.

Método: Estudo qualitativo-fenomenológico, realizado com estudantes do último

ano do Curso de Enfermagem da Universidade Católica de Moçambique. A entrevista

em profundidade foi a técnica utilizada para recolha de dados, analisados

através da análise de conteúdo.

Resultados: Os resultados foram divididos em quatro categorias

principais que emergiram da análise das entrevistas e dizem respeito 1) à

percepção dos alunos sobre o supervisor acadêmico, destacada pela presença e

ausência de docentes no ambiente clínico; 2) ao supervisor clínico explicitado

pelos supervisores técnicos de enfermagem, com subcategorias sobre o aluno de

nível superior como ameaça ao enfermeiro técnico, tensão na relação entre

supervisores clínicos e alunos, disposição e reação dos supervisores clínicos;

3) ao contexto, representado pela falta de recursos materiais e humanos,

diversidade cultural e pandemia de COVID-19; e 4) à percepção de si mesmos como

alunos, dividida em falta de orientação no ambiente clínico, vivência da

prática clínica como um pesadelo e esperança durante a experiência. Também são

apresentadas algumas propostas de melhorias.

Conclusão: Os resultados deste estudo permitiram descrever o fenômeno em

estudo, revelando a percepção dos estudantes sobre a supervisão clínica e o

efeito do contexto em que esta relação se desenvolve. Estes resultados servirão

para avaliar a forma de melhorar a supervisão clínica através da identificação

de um modelo inovador a seguir. Esta medida é essencial para o desenvolvimento

profissional dos estudantes de enfermagem.

Palavras-chave: educação em enfermagem; preceptoria; estudantes de enfermagem; enfermagem.

Resumen:

Objetivo: Describir las experiencias de los

estudiantes de último año de enfermería de la Universidad Católica de

Mozambique en relación con la supervisión clínica realizada por los técnicos de

enfermería.

Método: Estudio cualitativo-fenomenológico realizado con estudiantes de

último año de enfermería de la Universidad Católica de Mozambique. La

entrevista en profundidad fue la técnica utilizada para la recolección de

datos, que fueron analizados a través del análisis de contenido.

Resultados: Los resultados se dividieron en cuatro categorías

principales que surgieron del análisis de las entrevistas y están relacionadas

con 1) la percepción de los estudiantes sobre el supervisor académico, destacada

por la presencia y ausencia de personal docente en el entorno clínico; 2) el

supervisor clínico explicitado por los supervisores técnicos de enfermería, con

subcategorías sobre el estudiante de nivel superior como amenaza para el

enfermero técnico, tensión en la relación entre supervisores clínicos y

estudiantes, disposición y reacción de los supervisores clínicos; 3) al

contexto, representado por la falta de recursos materiales y humanos, la

diversidad cultural y la pandemia COVID-19; y 4) a la percepción sobre ellos

mismos como estudiantes, dividido en la falta de orientación en el entorno

clínico, el vivir las prácticas clínicas como una pesadilla y la esperanza

durante la experiencia. También se presentan algunas propuestas de mejora.

Conclusión: Los resultados de este estudio han permitido describir el

fenómeno estudiado, revelando la percepción de los estudiantes sobre la

supervisión clínica y el efecto del contexto en el que se desarrolla esta

relación. Estos resultados servirán para evaluar cómo mejorar la supervisión

clínica, identificando un modelo innovador a seguir. Esta medida es esencial

para el desarrollo profesional de los estudiantes de enfermería.

Palabras clave: educación en enfermería; preceptoría; estudiantes de enfermería; enfermería.

Received: 06/09/2023

Accepted: 16/03/2024

Introduction

Several countries around the world have taken an interest in the subject of clinical supervision in nursing, which is professional support for students. Its aim is to help trainees develop professional skills and confidence, integrate them in the clinical setting and therefore foster the transfer of theoretical knowledge into practice, thus ensuring better patient care. (1, 2) After all, “for trainees to be properly prepared, they need to be guided and supervised”. (3) Nurses play an important role in this process for the development of nursing students’ competence, acting as a source of support in the context of clinical practice to fortify nursing students’ professionalism. (2, 3)

Most research on clinical supervision in nursing has focused on the experiences of students and clinical supervisors, with positive experiences being found as a result, for example, the support given to students by supervisors. There are also negative experiences, which serve as barriers to students’ education and learning. These include an inadequate clinical setting; abuse of power (experiences related to abusive behaviour); supervisors’ incompetence; supervisors’ lack of continuous training in formative skills; lack of implementation of strategic tools to facilitate clinical supervision (innovative models of clinical supervision); clinical supervisors’ absence (lack of availability of supervisors who do not yet support learning); short formative evaluation procedures; and lack of formal recognition of supervisors’ roles. The need to implement innovative models of clinical supervision that allow for a structured and formal process is a concern in several countries around the world. (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9)

Innovative models of clinical supervision for nursing students and midwives are being developed worldwide, consisting of collaboration between the institutions involved in this process (university and clinical field) and the participation of the triad academic supervisor, clinical supervisor and student, with the aim of promoting successful learning in students, an effective and rewarding clinical environment for the triad and improving public health. (1, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16) Among these, the Partnership Participation Model (PEM, acronym in Portuguese) is the most tried and used in several countries around the world and it consists of each member of the partnership, the triad (academic supervisor, clinical supervisor and student), being responsible for the quality and effectiveness of the clinical learning activities, with a continuous commitment from planning to evaluation. (15,16) Studies conducted show that the use of such models improves the clinical learning setting and the supervisor’s competence. (11, 14, 15, 16)

Several African countries, including Ghana, Kenya, Malawi, Uganda, and South Africa, have shown concern regarding clinical supervision in nursing. Studies conducted in these countries have explored the experiences of nursing students and clinical supervisors in terms of clinical supervision, revealing both positive and negative influences on the process. Negative experiences reported in African countries often align with those observed globally. However, there are issues that, in some African countries, continue to be factors that negatively influence clinical supervision, such as lack of human resources and supervisors’ lack of remuneration. In view of this, it is necessary to look for strategies to improve clinical supervision and support for students. Additionally, nurse educators need to receive continuous training, plan clinical supervision and support effectively in order to promote competent nursing students. (2, 3, 17, 18, 19, 20) There is evidence that clinical supervision is a complex and dynamic educational perspective that can have both positive and negative aspects. (1, 3, 21) Therefore, the student’s experience in the clinical field is very important, as it can have a significant impact on their learning.

Mozambique is a country in Eastern and Southern Africa that became independent in 1975, and was then devastated by a civil war that ended in 1992. (22) After these long periods of war, most of the main health technicians left the country, resulting in a serious shortage of personnel to meet the needs in this field. The Mozambican government set out new strategies to train nurses at elementary and basic levels. This training lasted for many years. In 1980, the need arose to promote complementary and specialisation courses in different areas of nursing. At the same time, technical-professional health careers were established, divided into four levels: elementary, basic, middle-level and specialised middle-level. (23) In 2003, Maputo approved the creation of Instituto Superior de Ciências de Saúde (ISCISA), the first higher institute of health sciences, with higher education in various areas of health, including nursing. (23) Currently, the country has three levels of nursing training: middle-level, specialised middle-level and Bachelor’s Degree. For the general nursing technician (middle-level), the duration is 2 years and for the specialised technician (specialised middle level) it is 1 year and 6 months, both with competency-based training (CBT) “knowing how to do”. It focuses on the specific knowledge, attitudes and skills needed to carry out the procedure or activity. And as for the Bachelor’s Degree in Nursing, “nurse A”, the training lasts 4 years and emphasises competence in the student’s human development for humanised care and the future professional’s critical thinking and ability to intervene promptly with scientific knowledge. (24) In 2008, Universidade Católica de Moçambique (Catholic University of Mozambique), UCM in short, began offering Bachelor’s Degree in Nursing. The course lasts four years and uses the PBL (Problem-Based Learning) teaching method. (24) Clinical supervision, however, is an informal process, in which the university contacts a middle-level or middle-skilled nursing technician, depending on the area of practice, with no ongoing training in supervision and assigns them to supervise a group of students. (24) The lecturers and management of the Faculty of Health Sciences (FCS, acronym in Portuguese) at UCM act as mentors to control the process (24). Furthermore, in Mozambique there is a shortage of human resources. Existing health professionals cannot cover the large number of students entering the clinical field. Currently, there is one nurse for every 2,000 inhabitants, (22) and the majority are technicians.

As mentioned in the previous paragraph, at this embryonic stage, university students are supervised by nursing technicians. (24) According to Patricia Benner’s “from novice to expert” theory, clinical supervision is necessary for each stage in nurse training, and it is recommended that students be mentored by competent but not expert nurses, and guided by formal supervision programmes, to improve student and patient satisfaction, as well as organisational quality. (25, 26) No previous studies related to this topic were found in Mozambique. Therefore, a study exploring nursing students’ experiences of clinical supervision in the local context is relevant. The study aims to understand the experiences of final-year nursing students at UCM regarding clinical supervision provided by nursing technicians, in order to improve nursing education and learning (clinical supervision).

Methodology

Type of study

This study used the constructivist-qualitative paradigm, (27) according to which each participant has a subjective perception and discourse about the phenomenon. The research design used phenomenology, which is a philosophical method developed by Edmund Husserl (1859-1938), (28) it is concerned with how things or phenomena are experienced from a first-person perspective and describes common meaning, with the purpose of explaining the structure or essence of the lived experience of a phenomenon from the perspective of the unity of meaning, which is the identification of the essence of a phenomenon and its precise description through everyday lived experience. (27, 29) This is descriptive phenomenology, which consists of directly exploring, analysing and describing particular phenomena as freely as possible. The three steps of descriptive phenomenology were followed: (1) intuit; (2) analyse; and (3) describe. When in the first stage, intuiting, one became totally immersed in the phenomenon under study, one began to get to know the phenomenon described by the participants. Any criticism, evaluation or opinion was avoided and rigorous attention was paid to the phenomenon under study as it was described; the second stage consists of phenomenological analysis, which consisted of identifying the essence of the phenomenon under study from the data obtained and the way it was presented, as the descriptions were listened to, common themes or essences began to emerge; the third stage is phenomenological description, in which the written and verbal descriptions of the phenomenon were collected, classified and grouped. (29) This methodological approach was instrumental in addressing the research question: What are the experiences of final-year nursing students at Universidade Católica de Moçambique regarding the clinical supervision provided by nursing technicians? Additionally, it facilitated the achievement of the research aim.

Sample

The research participants were students in the 4th year of the bachelor’s degree in Nursing, as they begin clinical practice in the 2nd semester of the 1st year, in the Medicine sectors (Fundamentals of Nursing) at Hospital Central da Beira (Beira Central Hospital), HCB in short, to put basic nursing skills into practice. In the 2nd year, students have internships throughout the year. First semester, medical surgical internship at HCB; second semester, obstetrics internship at the health centres of Macurungo, Manga Mascarenha and Munhava (Beira-Sofala-Mozambique), which means that the internship hours are more extensive. In the 3rd year, the first semester is a paediatrics, emergency and psychiatry internship at HCB; and in the second semester, a community health internship with vulnerable families (which takes place in a suburban neighbourhood); and in the 4th year, the internship time is longer in a pre-professional system, that is, 8 hours a day and with night shifts, as well as a supervision internship where the 4th year students accompany the 1st year students in the fundamentals of nursing internship. Therefore, 4th year students have more experience of clinical supervision by nursing technicians. Seventy-five percent (75 %) of the practicals are carried out at HCB, which is the second largest hospital in the country and is also located in the country’s second largest population centre. (24) The participants were selected by purposive or convenience sampling, since the aim was to choose people who had experienced the phenomenon under study. Since the principal investigator was not in Mozambique, but had contact with some of the students at some point, the mobilisation was carried out by a research assistant, a doctor who is UCM alumnus and was not part of the faculty’s nursing department and had no contact with the final-year students. The role of the research assistant consisted only of applying informed knowledge and was not competent to understand the training context of the future nursing professional, as he was a general practitioner. There were 104 students, of whom 36 were male and the rest female. In this way, they were guaranteed voluntary participation and freedom to take part in the project.

The principal investigator prepared a video presentation detailing the purpose of the study and the conditions of completely voluntary participation, including information about the assistant and the researcher in charge, and sent it to the assistant who then forwarded it to the class WhatsApp group. This was followed by the recruitment phase, which culminated in 14 signed Informed Consents (ICs), applied in person by the assistant. The study had the following inclusion criteria: being a final-year nursing student at UCM-FCS; having completed their final internship (full internship) and expressing their willingness to take part in the study, formalised by signing the informed consent form. The exclusion criterion was not having completed the final internship (full internship). The exclusion criterion was not considered because of the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a delay in the programme, the entire group was still in the full internship, 2nd semester of the 4th year, and their participation was voluntary. Ten interviews were obtained with information saturation. (27)

Data was collected through in-depth interviews, between October 2021 and February 2022, with a single question: (27) What has been your experience of the clinical supervision provided by nursing technicians during your professional training? The interview was conducted in Portuguese language and online by the principal investigator via the Zoom platform. The students were connected to the platform at UCM-FCS establishments, where there was a tablet with Internet access. The assistant connected the participant to the platform and left them in the room. Since it was not the principal investigator who applied the ICs, at the beginning of the interviews each participant was asked to review the terms of the signed IC form for clarification in case of doubts. The duration of the interviews varied from approximately 40 minutes to 3 hours.

Data análisis

The ten interviews were analysed using the five steps described by Colaizzi, namely: 1) to become familiar with the information, the transcripts were read and the recordings were listened to, repeatedly, in order to gain a deep understanding of the experience; 2) the original transcripts were returned, and the significant statements were extracted; 3) the meaning of each significant statement was interpreted; 4) meanings were organised into sets of categories and subcategories; and 5) a comprehensive description was written. Bracketing was done, which according to Husserl means suspending or bracketing all judgment of the real (the researcher’s experience) in order to focus on the experience described by the participant, to get to the essence of the phenomenon. (27) In addition, the software Dedoose version 9.0.46 was used for this analysis to ensure the efficient and rigorous use of all the information obtained in this study. (29)

Data reliability