Ciencias Psicológicas; v20(1)

enero - junio 2026

10.22235/cp.v20i1.4581

Artículos originales

Relación de cibervictimización y victimización con la autolesión severa: rol mediador de la autolesión leve

Relationship between Cybervictimization and Victimization with Severe Self-Injury: Mediating Role of Mild Self-Injury

Relação entre cybervitimização e vitimização com a autolesão severa: Papel mediador da autolesão leve

Karen Guadalupe Duarte Tánori1, ORCID 0000-0003-4676-3161

Daniel Fregoso Borrego2, ORCID 0000-0003-4362-1256

José Ángel Vera Noriega3, ORCID 0000-0003-2764-4431

1 Universidad de Sonora, México, [email protected]

2 Universidad de Sonora, México

3 Universidad de Sonora, México

Resumen:

La autolesión no suicida, entendida como el daño deliberado al propio tejido corporal sin intención suicida, representa una problemática creciente en adolescentes, y se relaciona con diversas formas de victimización, tanto presencial como digital. Este estudio tuvo como objetivo relacionar la conducta de autolesión leve y severa con la victimización y cibervictimización, planteando que estas condicionan la autolesión severa cuando son mediadas por la autolesión leve, siendo la cibervictimización un predictor de mayor peso explicativo. Se obtuvo información de 433 estudiantes de secundaria, quienes completaron cuestionarios que midieron autolesión, victimización y cibervictimización. Se realizaron análisis descriptivos, correlaciones y modelos de mediación. Los resultados revelaron asociaciones positivas y significativas entre todas las variables, entre las que se destaca que la autolesión leve medió la relación entre la victimización presencial y la autolesión severa; mientras que en la cibervictimización se observó una relación directa robusta con la autolesión severa, lo que evidencia un mayor impacto de las agresiones digitales en la intensificación del daño autoinfligido. Estos hallazgos sugieren que la autolesión leve actúa como un eslabón crítico en la progresión hacia conductas graves, esto resalta la necesidad de intervenciones tempranas y específicas para prevenir la escalada del daño y sus relaciones patológicas.

Palabras clave: adolescencia; autolesión no suicida; cibervictimización; mediación; victimización escolar.

Abstract:

Non-suicidal self-injury, understood as the deliberate damage to one's own body tissue without suicidal intent, represents a growing problem among adolescents and has been linked to various forms of victimization, both in-person and digital. The present study aimed to examine the relationship between mild and severe self-injury and victimization and cybervictimization, positing that these forms of victimization condition severe self-injury when mediated by mild self-injury, with cybervictimization serving as a stronger explanatory predictor. Data were collected from 433 secondary school students who completed questionnaires measuring self-injury, in-person victimization, and cybervictimization. Descriptive analyses, correlations, and mediation models were conducted. The results revealed significant positive associations among all variables, highlighting that mild self-injury significantly mediated the relationship between in-person victimization and severe self-injury, while in the case of cybervictimization a robust direct relationship with severe self-injury was observed, evidencing a greater impact of digital aggression on the intensification of self-inflicted harm. These findings suggest that mild self-injury acts as a critical link in the progression toward more severe behaviors, underscoring the need for early and targeted interventions to prevent the escalation of harm and its pathological associations.

Keywords: adolescence; non-suicidal self-injury; cybervictimization; mediation; school victimization.

Resumo:

A autolesão não suicida, entendida como o dano deliberado ao próprio corpo sem intenção suicida, representa uma problemática crescente em adolescentes e se relaciona com diversas formas de vitimização, tanto presencial quanto digital. Este estudo teve como objetivo relacionar comportamentos de autolesão leve e severa com a vitimização e a cybervitimização, propondo que estas condicionam a autolesão severa quando são mediadas pela autolesão leve, sendo a cybervitimização um preditor com maior peso explicativo. Participaram 433 estudantes do ensino fundamental que completaram questionários sobre autolesão, vitimização e cybervitimização. Foram realizadas análises descritivas, correlações e modelos de mediação. Os resultados revelaram associações positivas e significativas entre todas as variáveis, destacando-se que a autolesão leve mediou a relação entre a vitimização presencial e a autolesão severa, enquanto, no caso da cybervitimização, observou-se uma relação direta robusta com a autolesão severa, evidenciando um maior impacto das agressões digitais na intensificação do dano autoinfligido. Esses achados sugerem que a autolesão leve atua como um elo crítico na progressão para condutas graves, ressaltando a necessidade de intervenções precoces e específicas para prevenir a escalada do dano e suas relações patológicas.

Palavras-chave: adolescência; autolesão não suicida; cybervitimização; mediação; vitimização escolar.

Recibido: 1/05/2024

Aceptado: 15/12/2025

La autolesión no suicida definida por Nock (2010) y, en concordancia con Liu et al. (2022), se entiende como la destrucción o daño directo, deliberado y socialmente inaceptable del propio tejido corporal sin intención suicida. Es una problemática asociada a la población clínica; sin embargo, una alta prevalencia en muestras de adolescentes considerados como población general ha sugerido la importancia de definir mejor las características individuales, así como los factores contextuales asociados a esta conducta (Esposito et al., 2019).

La autolesión puede manifestarse en distintos niveles de severidad, desde formas leves hasta formas más graves, que implican un daño significativo al tejido corporal. La autolesión leve se caracteriza por ser menos invasiva y puede incluir comportamientos como rasguños superficiales, pellizcos o golpes que no dejan daños permanentes. A diferencia de la autolesión severa, estas expresiones no siempre cumplen con una función clara de escape o de regulación emocional inmediata, sino que pueden representar una forma incipiente de afrontamiento ante malestar emocional o social (Hooley et al., 2020; Marín, 2013).

La evidencia sugiere que la autolesión leve no es un fenómeno aislado, sino que puede evolucionar progresivamente hacia formas más severas de autolesión, en las cuales sí se observa una clara función de escape ante emociones aversivas o situaciones de alta angustia (John et al., 2017). Este proceso de intensificación podría explicarse en parte por la sensibilización conductual y emocional, donde la repetición de conductas autolesivas genera una disminución de la aversión inicial al dolor y un aprendizaje progresivo de su función como mecanismo de afrontamiento (Santo & Dell’Aglio, 2022).

Es importante comprender que la autolesión se puede manifestar de manera leve y severa, con el fin de entender el fenómeno de manera precisa y poder visualizar su incidencia y prevalencia con menor error. Por ejemplo, el estudio de Duarte y Fregoso (2024) con una muestra no clínica generalizable de estudiantes adolescentes mostró que el 8.08 % realizan conductas de autolesión severa. Aunque puede parecer un porcentaje bajo, entendiendo que la autolesión severa refiere a comportamientos lesivos graves, este porcentaje resulta ser relevante al interpretarlo.

Según Faura-García et al. (2015), las conductas severas de autolesión refieren a aquellas que podrían denominarse como patológicas, y la autolesión leve a un comportamiento que no necesariamente se relaciona de manera directa con una afectación a la cual se necesita escapar. No obstante, aun cuando la autolesión leve podría referir a un comportamiento no relacionado a eventos emocionales negativos, el presentarse de manera regular podrían entenderse como un factor de riesgo para una autolesión severa (Hooley et al., 2020).

En este sentido, la autolesión leve puede actuar como un eslabón en la relación entre experiencias adversas y una autolesión severa al fungir como un elemento intermedio que facilita la transición hacia comportamientos más peligrosos. Por lo tanto, comprender la autolesión leve como un factor de riesgo clave en la progresión hacia la autolesión severa es fundamental (Plener et al., 2015). Esto para comprender el fenómeno en cuestión y así desarrollar estrategias de prevención e intervención dirigidas a detener este proceso antes de que evolucione a formas más graves de daño autoinfligido.

Autores como Klonsky (2007), Nock y Prinstein (2005) y Liu et al. (2022) han encontrado que los individuos realizan conductas autolesivas como estrategia para reducir un estímulo negativo. Por lo tanto, un factor importante para el desarrollo de conductas de autolesión es la victimización entre pares, ya que pueden estar funcionando como un medio de regulación de la angustia generada por dicha experiencia negativa, pues, como mencionan Heilbron y Prinstein (2018), esta es una problemática que genera un gran número de sensaciones y emociones negativas en los jóvenes.

Por su parte, Resett y González (2020) indicaron que la asociación entre la autolesión y la victimización es estadísticamente significativa, y que la victimización escolar por pares predice de manera significativa la autolesión (p < .001; β = .33). También Heilbron y Prinstein (2018) señalaron que la victimización entre pares es un factor de riesgo potencial para el desarrollo de autolesión no suicida y suicidio en adolescentes, al ser citados de forma frecuente los problemas interpersonales como el rechazo entre pares, victimización y aislamiento social, como elementos precipitantes de conductas de violencia autoinfligida. En su estudio, señalaron diferencias significativas entre las personas que no se autolesionan con las que sí lo hacen en función de la victimización por pares, lo que muestra que quienes refirieron ser víctimas se autolesionan.

En el mismo orden de ideas, un elemento que debe tomarse en cuenta como variable importante en el estudio del fenómeno de autolesión no suicida es la interacción dada por medios digitales. Por ejemplo, en el estudio de Duarte et al. (2023a) se planteó que el uso de internet puede ser un factor de riesgo para la autolesión no suicida, esto aumenta la probabilidad en un 237 %.

El internet ha favorecido al desarrollo de los adolescentes a través del desenvolvimiento de la identidad personal, estableciendo relaciones interpersonales, como recurso para obtener apoyo social y acceso a un gran número de posibilidades de entretenimiento y ocio (Davis, 2013). Sin embargo, también ha generado nuevos riesgos como el ciberbullying (Del Rey et al., 2016; Garaigordobil, 2017) y la adicción a internet.

El internet, siendo parte de los instrumentos digitales más presentes y crecientes en la actualidad, ha modificado las relaciones de los adolescentes con las figuras de apego principal, pues se ha transformado en una vía de comunicación importante, que impacta en la manera en la que se establece la comunicación padres-hijos, debido a la brecha digital entre generaciones (Yubero et al., 2018). Esto sugiere que la interacción con pares podría manifestarse con problemáticas interpersonales, como el ciberbullying.

Según el Instituto Federal de Telecomunicaciones (2019), los adolescentes entre 12 y 17 años tienen un 88.3 % de probabilidad de usar internet y los estudiantes tienen un 92.9 % de probabilidad, siendo, según Hernández y Alcoceba (2015), el grupo con mayor acceso a internet.

Autores como Vondrácková y Gabrhelik (2016) indicaron que el acceso a internet que tienen los adolescentes es muy fácil, por tanto, su uso excesivo es más probable, lo que podría provocar afectaciones como trastornos o deterioro emocional y psicológico. Otra afectación podría ser la autolesión no suicida, por lo que la relación entre la autolesión y el uso de internet en adolescentes resulta pertinente de investigarse. El uso de internet no causa de manera intrínseca afectaciones emocionales negativas, pero sí aumenta la probabilidad de tener interacciones que sí lo hagan. Así, las interacciones dadas por medios digitales, como la cibervictimización, la cual es definida por Nocentini et al. (2010) como agresiones entre iguales que se dan a través de internet o del teléfono móvil, agresiones de tipo escrito-verbal, exclusión y suplantación, también cobran relevancia en el estudio de la autolesión no suicida.

Con base en lo anterior, resulta pertinente considerar marcos teóricos que permitan explicar cómo las experiencias de victimización digital pueden traducirse en conductas autolesivas, especialmente cuando estas evolucionan en severidad. En este sentido, el Modelo de Ciberacoso de Barlett y Gentile (BGCM; Barlett et al., 2021) plantea que la exposición repetida a agresiones digitales refuerza creencias como la percepción de anonimato y la irrelevancia del poder físico, lo cual facilita la normalización del entorno hostil en línea. Aunque el BGCM se ha centrado en explicar la perpetración, sus principios de aprendizaje social y sensibilización emocional pueden extrapolarse para entender cómo la cibervictimización sostenida podría erosionar las barreras psicológicas al daño físico, lo que favorece la aparición de autolesiones como estrategia de afrontamiento.

El modelo BGCM (Barlett et al., 2021) es útil para el estudio de la victimización, pues esta radica en que los mecanismos centrales como el aprendizaje social, exposición repetida y normalización de entornos hostiles operan desde la perspectiva de quien recibe la agresión, ya que estar inmerso en estos escenarios de manera continua provoca desensibilización emocional dando la posibilidad de incrementar afectaciones psicológicas. Por ello, extrapolar este modelo a la perspectiva de la víctima resulta teóricamente razonable cuando se explicitan los puentes conceptuales que comparten perpetrador como víctima. Pues es posible visualizar, como lo ha mencionado Fawson et al. (2018), la transición de roles (agresor a víctima o víctima a agresor) y que esta transición referiría a uno de los efectos que tiene dicha agresión, ya que, por ejemplo, la víctima podría pasar a ser agresor como un mecanismo emocional/psicológico para adecuarse a su ambiente.

De esta manera, autores como Liu et al. (2023), Drubina et al. (2023) y Lin et al. (2023), por mencionar algunos ejemplos, han mostrado a través de ecuaciones estructurales que la cibervictimización predice de manera significativa la autolesión no suicida. También, en la revisión sistemática de Predescu et al. (2024), la cual involucró 20 estudios que relacionaron de manera empírica y explicativa la cibervictimización con la autolesión no suicida, se concluyó que la cibervictimización es un factor de riesgo importante al momento de estudiar la autolesión no suicida en jóvenes y adolescentes.

Lo anterior es de suma relevancia, pues el porcentaje de prevalencia en cibervictimización y victimización presencial es preocupante. Por ejemplo, el metaanálisis realizado por Domínguez-Alonso et al. (2023) mostró una prevalencia de cibervictimización del 22.18 % en adolescentes que utilizan internet. Con el mismo tipo de población, Degue et al. (2024) refirieron que la prevalencia de victimización presencial es del 34.6 %. Por su parte, Vega-Cauich (2018) analizó a 18839 jóvenes de entre 12 y 29 años, en donde hallaron que la prevalencia de cibervictimización en estudiantes de nivel preparatoria (adolescentes de 15 a 17 años) es de 26 %. Esto indica una presencia relevante de victimización y cibervictimización en adolescentes.

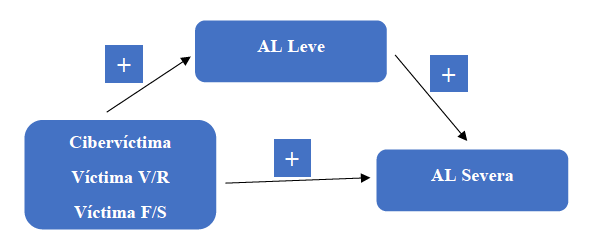

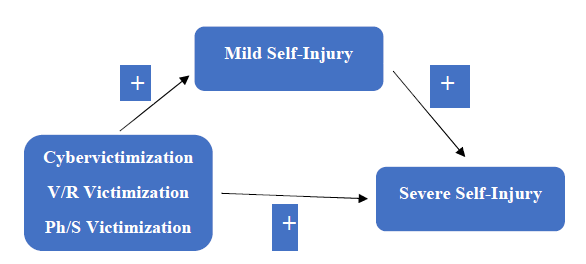

Considerando los antecedentes reseñados, el objetivo de este trabajo apunta a relacionar la conducta de autolesión no suicida con la victimización y la cibervictimización. La hipótesis es que la cibervictimización y la victimización condicionan las conductas de autolesión severa cuando son mediadas por las conductas de autolesión leve. También que la cibervictimización cuenta con un mayor peso explicativo que la victimización presencial sobre las conductas de autolesión (Figura 1).

Figura 1: Modelo conceptual para el análisis de mediación de las variables cibervictimización, víctima V/R y víctima S/F como independientes, donde autolesión leve es la variable mediadora y la autolesión severa la variable dependiente

Método

Participantes

La muestra fue de tipo aleatoria por conglomerados, conformada por 433 jóvenes que cursaban educación secundaria de 19 planteles públicos ubicados en la ciudad de Hermosillo, Sonora. Del total de la muestra 184 (42.5 %) adolescentes se encontraban en segundo grado y 249 (57.5 %) en tercer grado; 211 (48.7 %) eran hombres y 222 (52.3 %) mujeres. En relación con el turno, 358 (82.7 %) cursaban sus estudios en el turno matutino y 75 (17.3 %) en el turno vespertino. Cabe mencionar que los planteles fueron seleccionados al azar hasta alcanzar el 10 % de las escuelas de la región para obtener una muestra representativa, ya que, al 95 % de confianza y 5 % de error se necesitaban 384 estudiantes con un universo conocido de 130,044 estudiantes en la región.

En cuanto a los criterios de inclusión, se trataron de personas que se encontraran en los planteles escolares referidos. Como criterio de exclusión se abordó que no tuviesen algún diagnóstico relacionado a las neurodivergencias, que la muestra haya respondido el inventario de manera incompleta (menos del 90 % de los ítems) y que se hayan detectado patrones de respuesta azarosas.

Instrumentos

Cedula de autolesión (CAL). Es un cuestionario desarrollado por Marín (2013) y se compone de 12 reactivos dirigidos a detectar y medir de manera temporal conductas de autolesión tanto leve como severa. Presenta una escala tipo Likert de cinco opciones de respuesta (cero, 1 vez, 2-4 veces, 5-9 veces y 10 veces o más). Para población sonorense se realizó análisis factorial exploratorio (AFE), el cual obtuvo KMO de 0.93, una varianza total explicada (VTE) de 48.27 %, cargas factoriales de entre .61 y .78 y alfa de Cronbach de .89. Siete reactivos pertenecen a autolesión leve y cinco a autolesión severa. En tanto el análisis factorial confirmatorio (AFC) obtuvo CFI de .93; RMSEA de .07; y SRMR de .04 (Duarte et al., 2023b).

Cyberbulling Test. Escala creada por Garaigordobil (2017) para medir el fenómeno de ciberagresión, compuesta de 45 ítems distribuidos en tres dimensiones. Para este estudio se utilizó la adaptación de Navarro-Rodríguez et al. (2023), y solamente la dimensión de cibervictimización, la cual se compone de 12 ítems. Dicha adaptación se realizó con población de estudiantes de secundaria en Sonora a través de análisis Rasch y AFC, se obtuvo un infit de entre .75 y 1.42; outfit de entre .58 y 1.44; CFI de .94; RMSEA de .04; SRMR de .03 y consistencia interna por alfa de Cronbach de .92. Estos estadísticos refieren a un buen ajuste del instrumento.

Escala de agresores y víctimas. Escala creada por Del Rey y Ortega (2007) para evaluar comportamiento agresivo entre pares. Se compone por las dimensiones de agresión y victimización. Para este estudio se utilizó la versión de González et al. (2017), la cual adecuó el instrumento para población estudiantil de secundaria en Sonora. Se utilizaron las dos dimensiones de victimización (victimización verbal/relacional y victimización física/social) la cuales se componen por siete y cinco ítems respectivamente, que se evalúan en una escala Likert de 5 puntos. Se utilizó análisis Rasch, el cual obtuvo valores de infit de .54 a 1.35 y outfit de .75 a 1.24, y AFC el cual arrojó CFI de .9; RMSEA de .08 y SRMR de .05, lo que indica un ajuste óptimo para medir victimización.

Procedimientos

Con el propósito de recopilar los datos, se obtuvo un permiso emitido por la Secretaría de Educación Pública que permitió el acceso a las instituciones educativas. Seguido de la obtención del permiso, se acudió a los planteles educativos de nivel secundaria y se solicitó el ingreso a los grupos. Dentro de los salones de clases, un encuestador, que era un psicólogo circunscrito a un proyecto de investigación y capacitado de forma previa, hizo entrega de un consentimiento informado para dar a conocer el objetivo del estudio, así como la confidencialidad de los datos y que su nombre no sería revelado, sino que los análisis se realizarían de manera grupal. Asimismo, los planteles educativos se encargaron de informar a los padres y madres de familia de manera previa. También, se encargó de llevar a cabo el levantamiento de datos proporcionando un cuadernillo a los estudiantes para leer las preguntas y opciones de respuesta con una hoja de respuestas donde podían colocar la opción seleccionada, así como de indicarles la forma de contestar y resolver cualquier duda que los jóvenes pudieran tener. El tiempo de aplicación fue de alrededor de 50 minutos por grupo.

Análisis de datos

Primeramente, se realizaron análisis descriptivos univariados para obtener medidas de tendencia central. Posteriormente, se ejecutaron correlaciones de Pearson entre las variables de estudio con el fin de identificar las asociaciones bivariadas relevantes y así aproximarse al modelo propuesto.

Para evaluar el papel mediador de la autolesión leve en la relación entre victimización presencial y cibervictimización con autolesión severa, se llevaron a cabo modelos de mediación utilizando el procedimiento de regresión. En concreto, se utilizó el modelo 4, mediación simple (Hayes, 2022). Este modelo está dedicado a conocer si los efectos de una variable independiente (X) hacia una independiente (Y) se da de manera directa o si dicho efecto es debido a una tercera variable, mediadora (M), es decir, si existe un efecto indirecto. El efecto indirecto refiere al efecto que tiene X sobre Y a través de M. Los estadísticos para determinar la adecuación del modelo se dan a través de las β de X à M, β de M à Y, y β de X à Y (efecto directo); β de X à M * β de M à Y (efecto indirecto); y efecto total. Además, se observa la significancia estadística, que debería ser menor que .05, así como la R² (proporción de varianza explicada). Para aceptar un modelo de mediación es debido obtener un efecto de M à Y mayor que X à M, efecto total mayor que efecto directo y la existencia del efecto indirecto. Todos los efectos deben ser significativos. Además, no es necesario cumplir con normalidad, pues los efectos basados en bootstrapping no requieren dicho supuesto (Hayes, 2022).

Es preciso señalar que antes de realizar el análisis de mediación, se verificaron los supuestos asociados al modelo de regresión. Se comprobó la linealidad entre las variables, pues no se observaron patrones curvilíneos. La independencia de los errores fue evaluada a través del estadístico de Durbin-Watson, cuyo valor se encontró dentro del rango aceptable para cada modelo (1.50-2.50). La ausencia de multicolinealidad se confirmó al obtener valores de VIF inferiores a 5 y tolerancias superiores a .20. Asimismo, se revisó la homocedasticidad mediante análisis de los residuos (Hayes, 2022).

Para llevar a cabo los análisis descritos, se utilizó el software SPSS v.25 con la extensión PROCESS macro v.3.5. También, se utilizó Rstudio v.4.0.3 para los análisis descriptivos y correlacionales.

Resultados

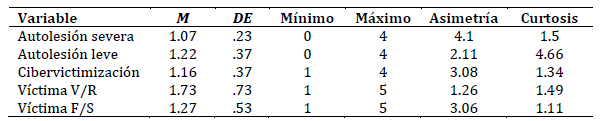

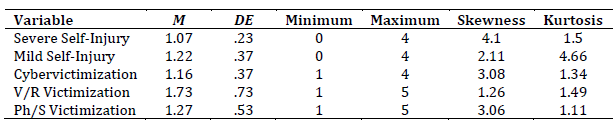

Primeramente, se muestran los análisis descriptivos de las variables de estudio en términos de media (M), desviación estándar (DE), mínimo, máximo, así como asimetría y curtosis. Es importante considerar que, según lo planteado por Kim (2013), las variables son tendientes a la normalidad, pues su asimetría y curtosis no sobrepasa el ± 7 (Tabla 1).

Tabla 1: Análisis descriptivos para las variables de estudio

Nota: N = 433. M = Media; DE = Desviación estándar.

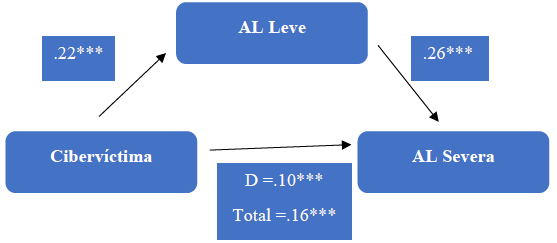

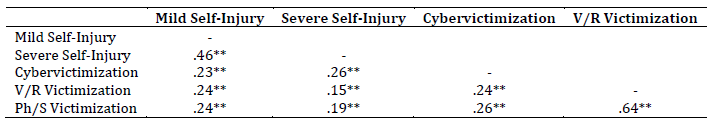

Posteriormente, se realizaron correlaciones entre las variables de estudio (Tabla 2). Los análisis de correlación evidenciaron asociaciones positivas y estadísticamente significativas entre todas las variables examinadas. Destacó la correlación moderada entre autolesión leve y severa (r = .46; p < .01), así como las asociaciones más débiles, aunque consistentes, entre cibervictimización y autolesión leve (r = .23; p < .01) y severa (r = .26; p < .01). La victimización física/social mostró la correlación más elevada con victimización verbal/relacional (r = .64; p < .01), lo que sugiere una superposición entre estas formas de agresión.

Tabla 2: Correlaciones entre las variables de estudio

Nota: N = 433.

**p < .001

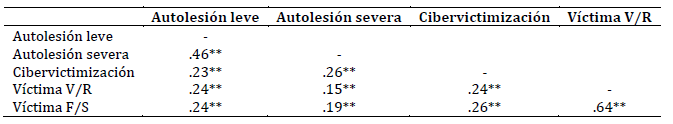

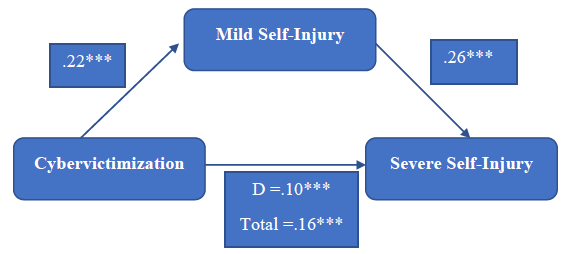

Seguidamente, para dar cumplimiento del objetivo planteado y comprobar las hipótesis postuladas, se procedió a realizar tres análisis de mediación con las diferentes configuraciones, así como se mostró en la Figura 1. La Figura 2 muestra el modelo de mediación de cibervictimización sobre la autolesión severa a través de la autolesión leve. Los resultados mostraron que la cibervictimización tuvo un efecto estadísticamente significativo sobre autolesión leve (β = .22; DE = .04; p < .001; IC (.13 .32)) y que esta, a su vez, tiene un efecto estadísticamente significativo sobre autolesión severa (β = .26; DE = .02 p < .001; IC (.20 .31)). La relación total entre cibervictimización y autolesión severa mediada por autolesión leve fue significativa (β = .16; DE = .02; p < .001 IC (.10 .22)); además, al observar el efecto directo de cibervictimización sobre la autolesión severa es menor (β = .10, DE = .02; p < 001 IC (.05 .15)) que el efecto total. También, el efecto indirecto de la cibervictimización a través de la autolesión leve fue significativo, con un valor β = .06 (DE = .02), 95 % IC (.01 .12). La varianza explicada por el modelo fue R² = .26. Tomando en cuenta el valor del efecto indirecto y del total en comparación al efecto directo, se constata un efecto de mediación.

Figura 2: Modelo de mediación para las variables cibervictimización, autolesión leve y autolesión severa

Nota: AL: Autolesión; D: Efecto directo.

***p <.001

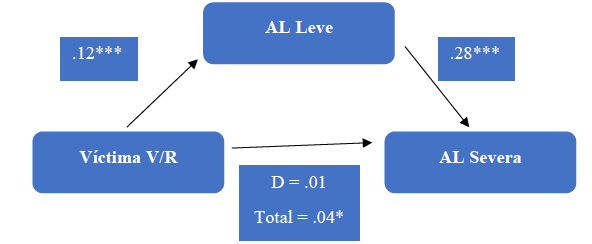

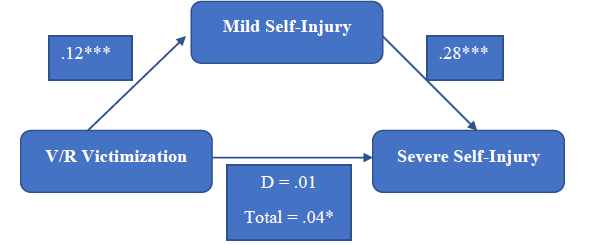

La Figura 3 muestra el modelo de mediación de víctima V/R sobre la autolesión severa a través de la autolesión leve. Los resultados mostraron que la víctima V/R tuvo un efecto estadísticamente significativo sobre autolesión leve (β = .12; DE = .02; p < .001; IC (.07 .16)) y que esta, a su vez, tiene un efecto estadísticamente significativo sobre autolesión severa (β = .28; DE = .02 p < .001; IC (.22 .33)). La relación total entre víctima V/R y autolesión severa mediada por autolesión leve fue significativa (β = .04; DE = .01; p < .05; IC (.02 .07)); además, al observar el efecto directo de víctima V/R sobre la autolesión severa es menor y no es significativo (β = .01, DE = .01; p = .27; IC (-.01 .04)) que el efecto total. También, el efecto indirecto de la víctima V/R a través de la autolesión leve fue significativo, con un valor β = .03 (DE = .01), 95% IC (.01 .06). La varianza explicada del modelo fue R² = .21. Tomando en cuenta el valor del efecto indirecto y del total en comparación al efecto directo, se constata un efecto de mediación, aunque es importante mencionar que, aunque es significativo, la beta del efecto total del modelo no es fuerte.

Figura 3: Modelo de mediación para las variables víctima V/R, autolesión leve y autolesión severa

Nota: AL: Autolesión; D: Efecto Directo; VR: Verbal/Relacional.

***p < .001; *p < .05

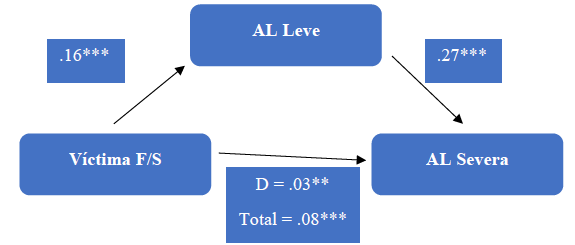

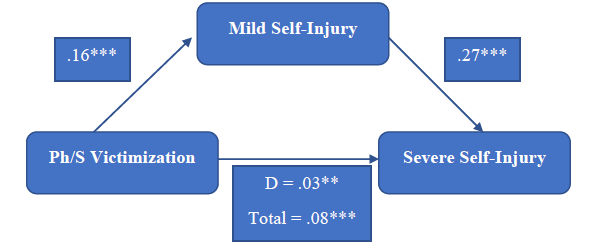

La Figura 4 muestra el modelo de mediación de víctima F/S sobre la autolesión severa a través de la autolesión leve. Los resultados mostraron que la víctima F/S tuvo un efecto estadísticamente significativo sobre autolesión leve (β = .16; DE = .03; p < .001; IC (.10 .23)) y que esta, a su vez, tiene un efecto estadísticamente significativo sobre autolesión severa (β = .27; DE = .02 p < .001; IC (.21 .32)). La relación total entre Víctima F/S y autolesión severa mediada por autolesión leve fue significativa (β = .08; DE = .02; p < .001; IC (.04 .12)); además, al observar el efecto directo de víctima F/S sobre la autolesión severa es menor y es significativo (β = .03, DE = .01; p < .05; IC (.002 .07)) que el efecto total. También, el efecto indirecto de la víctima F/S a través de la autolesión leve fue significativo, con un valor β = .04 (DE = .01), 95% IC (.01 .08). La varianza explicada del modelo fue R² = .21. Tomando en cuenta el valor del efecto indirecto y del total en comparación al efecto directo, se constata un efecto de mediación, aunque es importante mencionar que, aunque es significativo, la beta del efecto total del modelo no es fuerte.

Figura 4: Modelo de mediación para las variables víctima F/S, autolesión leve y autolesión severa

Nota: AL: Autolesión; D: Efecto Directo; F/S: Física/Social.

***p < .001; **p < .01

Discusión

Los resultados obtenidos en este estudio permiten afirmar que se cumple con el objetivo planteado, el cual consistió en analizar la relación entre la conducta de autolesión no suicida y diversas formas de victimización, tanto presencial como digital mediada por la autolesión leve. Asimismo, se logra contrastar y confirmar las dos hipótesis formuladas. Por un lado, los modelos de mediación propuestos evidencian que tanto la victimización presencial (física/social y verbal/relacional) como la cibervictimización se relacionan con conductas de autolesión severa a través de la mediación de la autolesión leve. Por otro lado, se observó que la cibervictimización presentó un mayor peso explicativo sobre las conductas autolesivas severas en comparación con la victimización presencial, lo cual sugiere, en concordancia con Garaigordobil (2017), que los entornos digitales constituyen espacios particularmente significativos en la generación de malestar emocional profundo en la adolescencia.

Estos hallazgos se alinean con los postulados teóricos que conceptualizan la autolesión no suicida como un comportamiento funcional, destinado a regular estados afectivos intensos o aliviar la tensión emocional, tal como lo han sugerido Klonsky (2007), Nock y Prinstein (2005) y Liu et al. (2022). De esta manera, la exposición a experiencias adversas como la victimización entre pares o el acoso digital se convierte en un disparador relevante para este tipo de conductas, especialmente cuando no se cuenta con recursos adaptativos de afrontamiento.

Además, el hecho de que la autolesión leve medie la relación entre la victimización y la autolesión severa brinda apoyo empírico a la noción de que las conductas autolesivas pueden presentarse de forma escalonada, progresiva y funcionalmente diferenciada.

Tal como se argumentó en la introducción, la autolesión leve suele carecer de una función clara de escape o regulación emocional en sus primeras manifestaciones, pero puede representar una etapa inicial en la que el individuo explora conductas que, si bien inicialmente no están dirigidas a calmar el sufrimiento, pueden eventualmente cumplir esa función al ser reforzadas por su efecto sobre el malestar psicológico (Faura-García et al., 2015; Hooley et al., 2020). Este proceso podría explicar cómo la autolesión leve se convierte en un factor mediador hacia la autolesión severa, especialmente cuando el malestar derivado de la victimización se sostiene en el tiempo o intensifica.

De manera empírica, y recuperando lo que Faura-García et al. (2015) refirieron sobre la relación de la autolesión severa con aspectos patológicos, Duarte et al. (2023a) demostraron que variables patológicas como la depresión y la adicción a internet son predictores potentes para la autolesión severa; sin embargo, para la autolesión leve ninguna de estas variables fue significativa.

Desde esta perspectiva, los modelos de mediación propuestos se dirigen a constatar lo mencionado anteriormente, se trata de comprender la autolesión leve como, además de una forma menor de daño físico, un fenómeno relevante que podría advertir sobre trayectorias de mayor riesgo. El hallazgo de que la autolesión leve media consistentemente los efectos de distintas formas de victimización sobre la autolesión severa sugiere que esta puede desempeñar un papel crucial en el proceso de escalamiento de la conducta autolesiva, funcionando como un predictor temprano que requiere atención.

Lo anterior concuerda con lo planteado por Zhou et al. (2024), quienes plantean que la manifestación de eventos estresantes con dificultad sobre la regulación emocional se podría reflejar en autolesiones menores y que estas pueden mostrarse como manifestaciones más graves cuando no se interviene. En este sentido, la incorporación de la autolesión leve como mediador permite capturar ese proceso de escalamiento dinámico, pues opera como mecanismo intermedio que conecta la exposición a victimización con la autolesión severa, esto refuerza la importancia de la detección temprana y el análisis longitudinal de las trayectorias de riesgo.

Adicionalmente, el hallazgo de que la autolesión leve funciona como un mediador abre espacios para intervención preventiva en fases iniciales de deterioro emocional. No trabajar en los factores emocionales que impulsan estas conductas podría escalar hasta ideación suicida (De Neve-Enthoven et al., 2024), de esta manera, la autolesión leve podría incluso funcionar como un marcador clínico de alerta, un punto estratégico de intervención temprana.

En cuanto a las diferencias encontradas entre la victimización presencial y la digital, los datos indican que la cibervictimización tiene un mayor peso en la predicción de la autolesión severa. Es preciso aludir a la naturaleza de la interacción de los adolescentes en los medios digitales, pues sucesos como la cibervictimización podrían amplificar su impacto emocional, al tratarse de situaciones que no se limitan a un entorno físico determinado ni a un horario específico, sino que pueden persistir de forma constante a través de plataformas digitales (Kowalski et al., 2014). Aunado a ello, el anonimato y la rápida difusión del contenido en redes sociales tienden a generar una sensación de indefensión y exposición pública que puede ser particularmente abrumadora en etapas de desarrollo, como la adolescencia, caracterizada por una alta sensibilidad a la aceptación social y la identidad grupal (Zhang, 2023).

Por otra parte, es importante mencionar que en estudios como el de Carvalho (2021) y el de Resett y Gamez-Guadix (2017) se ha demostrado que la cibervictimización se relaciona con comportamientos o afectaciones negativas, como el consumo de sustancias, rechazo social o bienestar. Así, los hallazgos coinciden con investigaciones previas que indican que la cibervictimización puede ser un predictor con mayor relevancia para la problemática de autolesión, la cual se relaciona con las afectaciones negativas, que la victimización presencial o tradicional.

Conclusiones

La tecnología digital, si bien ofrece múltiples oportunidades de interacción, abre nuevas posibilidades para la violencia entre pares que requieren ser abordadas con estrategias específicas de intervención.

Un aspecto importante que considerar en la interpretación de estos resultados es el papel que puede estar desempeñando la disponibilidad de recursos emocionales y sociales en la forma en que los adolescentes enfrentan las experiencias de victimización. Es posible que aquellos con menor acceso a redes de apoyo o con habilidades de regulación emocional más precarias sean más propensos a emplear la autolesión como un mecanismo de afrontamiento ante la angustia.

La función expresiva o comunicativa de la autolesión leve podría ser interpretada como una forma de pedir ayuda o visibilizar el malestar cuando no se dispone de otros canales. Con el tiempo, si estas conductas no son reconocidas e intervenidas, podrían escalar en intensidad hasta convertirse en formas más severas de daño corporal.

En este sentido, la comprensión del proceso mediador observado entre victimización y autolesión severa a través de la autolesión leve tiene implicaciones clínicas y preventivas relevantes. En primer lugar, resalta la importancia de detectar a tiempo conductas autolesivas leves, las cuales suelen pasar desapercibidas o ser minimizadas tanto por adultos como por pares, y que podrían constituir señales tempranas de un proceso de deterioro emocional progresivo. En segundo lugar, enfatiza la necesidad de programas de intervención que no solo trabajen sobre la reducción de las conductas de victimización, sino que también promuevan habilidades emocionales y estrategias alternativas de afrontamiento que impidan el uso de la autolesión como única vía de descarga emocional.

Asimismo, el presente estudio aporta evidencia a la discusión en torno a los diferentes tipos de victimización presencial y su vínculo con la autolesión. La intensidad del efecto fue menor que en el caso de la cibervictimización. Esto podría estar relacionado con la evolución de los entornos sociales en la adolescencia actual, donde las redes sociales digitales tienen un peso creciente en la construcción de la identidad, la pertenencia grupal y la validación personal. En este contexto, la victimización digital podría percibirse como más amenazante, por lo que sus consecuencias emocionales serían más intensas.

Como limitaciones de este estudio es debido considerar que trata de un estudio transversal, por lo que, con los análisis realizados, no se podría comprobar causalidad, así las inferencias sobre la dirección causal deben tomarse con cautela. Otro elemento importante es que no se consideró el solapamiento de victimización, se recomienda que en futuras investigaciones se concrete si los tipos de victimización se solapan. Aunque los efectos obtenidos en los modelos de victimización presencial se diferencian del modelo de cibervictimización, se tendría mayor claridad y menor error si se elimina solapamiento. Asimismo, sería pertinente ahondar en aspectos como la intensidad o duración de las experiencias de acoso, esto podría tener un efecto modulador. Aunado a ello, otras variables que podrían ser relevantes son la edad y el sexo, se sugiere abordarlas en futuras investigaciones como moderadoras, ya que el fenómeno podría variar en función a ello.

Referencias:

Barlett, C. P., Bennardi, C., Williams, S., & Zlupko, T. (2021). Theoretically predicting cyberbullying perpetration in youth with the BGCM: Unique challenges and promising research opportunities. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 708277. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.708277

Carvalho, M., Branquinho, C., & De Matos, M. G. (2021). Cyberbullying and bullying: Impact on psychological symptoms and well-being. Child Indicators Research, 14, 435-452. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12187-020-09756-2

Davis, K. (2013). Young people’s digital lives: The impact of interpersonal relationships and digital media use on adolescents’ sense of identity. Computers in Human Behavior, 29, 2281-2293. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2013.05.022

De Neve-Enthoven, N. G. M., Ringoot, A. P., Jongerling, J., Boersma, N., Berges, L. M., Meijnckens, D., Hoogendijk, W. J., & Grootendorts-Van Mil, N. H. (2024). Adolescent nonsuicidal self-injury and suicidality: A latent class analysis and associations with clinical characteristics in an at-risk cohort. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 53, 1197-1213. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-023-01922-3

Degue, S., Ray, C. M., Bontempo, D., Niolon, P. H., Tracy, A. J., Estefan, L. F., Le, V. D., & Little, T. D. (2023). Prevalence of violence victimization and perpetration during middle and high school in under-resourced, urban communities. Violence and Victims, 38(6), 839-857. https://doi.org/10.1891/VV-2022-0033

Del Rey, R., & Ortega, R. (2007). Violencia escolar: claves para comprenderla y afrontarla. Escuela Abierta, 10(1), 77-89.

Del Rey, R., Lazuras, L., Casas, J. A., Barkoukis, V., Ortega-Ruiz, R., & Tsorbatzoudis, H. (2016). Does empathy predict (cyber) bullying perpetration, and how do age, gender and nationality affect this relationship? Learning and Individual Differences, 45, 275-281. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2015.11.021

Domínguez-Alonso, J., Portela-Pino, I., & Álvarez-García, D. (2023). Incidence and demographic correlates of self-reported cyber-victimization among adolescent respondents. Journal of Technology and Science Education, 13(3), 823-836. https://doi.org/10.3926/jotse.2000

Drubina, B., Kökönyei, G., Várnai, D., & Reinhardt, M. (2023). Online and school bullying roles: are bully-victims more vulnerable in nonsuicidal self-injury and in psychological symptoms than bullies and victims? BMC Psychiatry, 23(1), 945. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-023-05341-3

Duarte, K. G., & Fregoso, D. (2024). Relación entre autolesión no suicida y cibervictimización en adolescents mexicanos. En C. Cruz, A. P. Ruíz, M. L. Pacheco, & N. A. Ruvalcaba (Eds.). Investigación Actual en Psicología Social. (425-435). Universidad de Guadalajara.

Duarte, K. G., Vera, J. A., Fregoso, D., & Bautista, G. (2023a). Autolesiones no suicidas, apego a padres, pares y adicción a internet en adolescentes mexicanos. Pensamiento Psicológico, 20, 1-29. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javerianacali.PPSI21.aiaa

Duarte, K. G., Vera, J. A., Fregoso, D., & Bautista, G. (2023b). Evaluación psicométrica de la escala de autolesión y depression en adolescents mexicanos. Revista de Psicología de la Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México, 11(34), 203-231. https://doi.org/10.36677/rpsicologia.v11i24.18555

Esposito, C., Bacchini, D., & Affuso, G. (2019). Adolescent non-suicidal self-injury and its relationships with school bullying and peer rejection. Psychiatry Research, 274, 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.02.018

Faura-García, J., Orue, I., & Calvete, E. (2021). Cyberbullying victimization and nonsuicidal self-injury in adolescents: The role of maladaptative schems and dispositional mindfulness. Child Abuse & Neglect, 118, 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chiabu.2021.105135

Fawson, P. R., Broce, R., & MacNamara, M. (2018). Victim to Aggressor: The relationship between intimate partner violence victimization, perpetration, and mental health symptoms among teenage girls. Partner Abuse, 9(1), 3-17. https://doi.org/10.1891/1946-6560.9.1.3

Garaigordobil, M. (2017). Psychometric properties of the Cyberbullying Test, a screening instrument to measure cybervictimization, cyberaggression, and cyberobservation. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 32(23), 3556-3576. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260515600165

González, E., Peña, M., & Vera, J. A. (2017). Validación de una escala de roles de víctimas y agresores asociados al acoso escolar. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 15(1), 2224-239. https://doi.org/10.14204/ejrep.41.16009

Hayes, A. F. (2022). Introduction to mediation, moderation and conditional process analysis: A regression-based approach. Guilford Press.

Heilbron, N., & Prinstein, M. (2018). Adolescent peer victimization, peer status, suicidal ideation, and nonsuicidal self-injury: Examining concurrent and longitudinal associations. Merril-Palmer Quarterly, 56(3), 388-419. https://doi.org/10.1353/mpq.0.0049

Hernández, C., & Alcoceba, J. A. (2015). Socialización virtual, multiculturalidad y riesgos de los adolescentes latinoamericanos en España. Icono14, 14(13), 116-141. https://doi.org/10.7195/ri14.v13i2.787

Hooley, J. M., Fox, K. R., & Boccagno, C. (2020). Nonsuicidal self-injury: Diagnostic challenges and current perspectives. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, (16), 101-112. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S198806

Instituto Federal de Telecomunicaciones. (2019). Uso de las TIC y actividades por internet en México: Impacto de las características sociodemográficas de la población.

John, A., Glendenning, A. C., Marchant, A., Montgomery, P., Stewart, A., Wood, S., Lloyd, K., & Hawton, K. (2017). Self-Harm, suicidal behaviours, and cyberbullying in children and young people: systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 20(4), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.9044

Kim, H. Y. (2013). Statistical notes for clinical researchers: Assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restorative Dentistry & Endodontics, 38(1), 52-54. https://doi.org/10.5395/rde.2013.38.1.52

Klonsky, E. D. (2007). The functions of deliberate self-injury: A review of the evidence. Clinica Psychology Review, 27(2) 226-239. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2006.08.002

Kowalski, R. M., Giummetti, G. W., Schroeder, A. N., & Lattanner, M. R. (2014). Bullying in the digital age: a critical review and meta-analysis of cyberbullying research among youth. Psychological Bulletin, 140(4), 1073-1131. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035618

Lin, S., Li, Y., Sheng, J., Wang, L., Han, Y., Yang, X., Yu, Ch., & Chen, J. (2023). Cybervictimization and non-suicidal self-injury among Chinese adolescents: A longitudinal moderated mediation model. Journal of Affective Disorders, 329, 470-476. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2023.02.124

Liu, R., Walsh, R., Sheehan, A., Cheek, S., & Sanzari, C. (2022). Prevalence and correlates of suicide and nonsuicidal self-injury in children. A systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Psychiatry, 79(7), 718-726. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2022.1256

Liu, S., Wu, W., Zou, H., Chen, Y., Xu, L., Zhang, W., Yu, C., & Zhen, S. (2023). Cybervictimization and non-suicidal self-injury among Chinese adolescents: The effect of depression and school connectedness. Frontiers in Public Health, 11, 1-7. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2023.1091959

Marín, M. (2013). Desarrollo y evaluación de una terapia cognitivo conductual para adolescentes que se autolesionan (Tesis de doctorado). Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México. http://www.ciencianueva.unam.mx/handle/123456789/78

Navarro-Rodríguez, D., Bauman, S., Vera, J. A., & Lagarda, A. (2023). Psychometric properties of a cyberaggression measure in mexican students. Behavioral Sciences, 14(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.3390/bs14010019

Nocentini, A., Calmaestra, J., Schultze-Krumbholz, A., Scheithauer, H., Ortega, R., & Menesini, E. (2010). Cyberbullying: Labels, behaviours and definition in three European countries. Australian Journal of Guidance and Couselling, 20(2), 129-142. https://doi.org/10.1375/ajgc.20.2.129

Nock, M. K. (2010). Self-injury. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 6, 339-363. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.clinpsy.121208.131258

Nock, M. K., & Prinstein, M. J. (2005). Contextual features and behavioral functions of self-mutilation among adolescents. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 114(1), https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.114.1.140

Plener, P., Schumacher, T. S., Munz, L. M., & Groschwitz, R. C. (2015). The longitudinal course of non-suicidal self-injury and deliberate self-harm: a systematic review of the literature. Borderline Personality Disorder and Emotion Dysregulation, 2(2), 1-11. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40479-014-0024-3

Predescu, E., Calugar, I., & Sipos, R. (2024). Cyberbullying and non-suicidal self-injury (NSSI) in adolescence: exploring moderators and mediators through a systematic review. Children, 11(4), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.3390/children11040410

Resett, S., & Gamez-Guadix, M. (2017). Traditional bullying and cyberbullying: differences in emotional problems, and personality. Are cyberbullies more machiavellians? Journal of Adolescence, 61, 113-116. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2017.09.013

Resett, S., & González, P. (2020). Predicción de autolesiones e ideación suicida en adolescentes a partir de la victimización de pares. Summa Psicológica UST, 17(1), 20-29. https://doi.org/10.18774/0719-448.x2020.17.453

Santo, M. A., & Dell’Aglio, D. D. (2022). Self-injury in adolescence from the bioecological perspective of human development. Human Development, 24(1), 1-24. https://doi.org/10.5935/1980-6906/ePTPHD13325.en

Vega-Cauich, J. I. (2018). Validación del Cuestionario Breve de Victimización Escolar por Pares en México. Acta de Investigación Psicológica, 8(1), 72-82. https://doi.org/10.22201/fpsi.20074719e.2018.1.07

Vondrácková, P., & Gabrhelík, R. (2016). Prevention of internet addiction: A systematic review. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 5(4), 568-579. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.5.2016.085

Yubero, S., Larrañaga, E., Navarro, R., & Elche, M, (2018). Padres, hijos e internet. Socialización familiar de la red. Universitas Psychologica, 17(2), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.upsy17-2.phis

Zhang, Y. (2023). The influence of internet on adolescent psychological development from the perspective of developmental psychology. Proceedings of the International Conference on Social Psychology and Humanity Studies, 8, 18-23. https://doi.org/10.54254/2753-7048/8/20230010

Zhou, L., Qiao, C., Huang, J., Lin, J., Zhang, H., Xie, J., Yuan, Y., & Hu, C. (2024). The impact of recent life events, internalizing symptoms and emotion regulation on the severity of non-suicidal self-injury in adolescents: A mediation analysis. Neuropsychiatric Disease and Treatment, 20, 415-428. https://doi.org/10.2147/NDT.S444729

Cómo citar: Duarte Tánori, K. G., Fregoso Borrego, D., & Vera Noriega, J. A. (2026). Relación de cibervictimización y victimización con la autolesión severa: rol mediador de la autolesión leve. Ciencias Psicológicas, 20(1), e-4581. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v20i1.4581

Disponibilidad de datos: El conjunto de datos que apoya los resultados de este estudio no se encuentra disponible.

Financiamiento: Se agradece a la Secretaría de Ciencia, Humanidades, Tecnología e Innovación (antes CONACYT) por el apoyo financiero para este estudio.

Conflicto de interés: Los autores declaran no tener ningún conflicto de interés.

Contribución de los autores (Taxonomía CRediT): 1. Conceptualización; 2. Curación de datos; 3. Análisis formal; 4. Adquisición de fondos; 5. Investigación; 6. Metodología; 7. Administración de proyecto; 8. Recursos; 9. Software; 10. Supervisión; 11. Validación; 12. Visualización; 13. Redacción: borrador original; 14. Redacción: revisión y edición.

K. G. D.T. ha contribuido en 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14; D. F. B. en 2, 3, 6, 9, 11, 12, 13; J. A. V. N. en 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 14.

Editora científica responsable: Dr. Cecilia Cracco.

Ciencias Psicológicas; v20(1)

January - June 2026

10.22235/cp.v20i1.4581

Original Articles

Relationship between Cybervictimization and Victimization with Severe Self-Injury: Mediating Role of Mild Self-Injury

Relación de cibervictimización y victimización con la autolesión severa: rol mediador de la autolesión leve

Relação entre cybervitimização e vitimização com a autolesão severa: Papel mediador da autolesão leve

Karen Guadalupe Duarte Tánori1, ORCID 0000-0003-4676-3161

Daniel Fregoso Borrego2, ORCID 0000-0003-4362-1256

José Ángel Vera Noriega3, ORCID 0000-0003-2764-4431

1 Universidad de Sonora, Mexico, [email protected]

2 Universidad de Sonora, Mexico

3 Universidad de Sonora, Mexico

Abstract:

Non-suicidal self-injury, understood as the deliberate damage to one's own body tissue without suicidal intent, represents a growing problem among adolescents and has been linked to various forms of victimization, both in-person and digital. The present study aimed to examine the relationship between mild and severe self-injury and victimization and cybervictimization, positing that these forms of victimization condition severe self-injury when mediated by mild self-injury, with cybervictimization serving as a stronger explanatory predictor. Data were collected from 433 secondary school students who completed questionnaires measuring self-injury, in-person victimization, and cybervictimization. Descriptive analyses, correlations, and mediation models were conducted. The results revealed significant positive associations among all variables, highlighting that mild self-injury significantly mediated the relationship between in-person victimization and severe self-injury, while in the case of cybervictimization a robust direct relationship with severe self-injury was observed, evidencing a greater impact of digital aggression on the intensification of self-inflicted harm. These findings suggest that mild self-injury acts as a critical link in the progression toward more severe behaviors, underscoring the need for early and targeted interventions to prevent the escalation of harm and its pathological associations.

Keywords: adolescence; non-suicidal self-injury; cybervictimization; mediation; school victimization.

Resumen:

La autolesión no suicida, entendida como el daño deliberado al propio tejido corporal sin intención suicida, representa una problemática creciente en adolescentes, y se relaciona con diversas formas de victimización, tanto presencial como digital. Este estudio tuvo como objetivo relacionar la conducta de autolesión leve y severa con la victimización y cibervictimización, planteando que estas condicionan la autolesión severa cuando son mediadas por la autolesión leve, siendo la cibervictimización un predictor de mayor peso explicativo. Se obtuvo información de 433 estudiantes de secundaria, quienes completaron cuestionarios que midieron autolesión, victimización y cibervictimización. Se realizaron análisis descriptivos, correlaciones y modelos de mediación. Los resultados revelaron asociaciones positivas y significativas entre todas las variables, entre las que se destaca que la autolesión leve medió la relación entre la victimización presencial y la autolesión severa; mientras que en la cibervictimización se observó una relación directa robusta con la autolesión severa, lo que evidencia un mayor impacto de las agresiones digitales en la intensificación del daño autoinfligido. Estos hallazgos sugieren que la autolesión leve actúa como un eslabón crítico en la progresión hacia conductas graves, esto resalta la necesidad de intervenciones tempranas y específicas para prevenir la escalada del daño y sus relaciones patológicas.

Palabras clave: adolescencia; autolesión no suicida; cibervictimización; mediación; victimización escolar.

Resumo:

A autolesão não suicida, entendida como o dano deliberado ao próprio corpo sem intenção suicida, representa uma problemática crescente em adolescentes e se relaciona com diversas formas de vitimização, tanto presencial quanto digital. Este estudo teve como objetivo relacionar comportamentos de autolesão leve e severa com a vitimização e a cybervitimização, propondo que estas condicionam a autolesão severa quando são mediadas pela autolesão leve, sendo a cybervitimização um preditor com maior peso explicativo. Participaram 433 estudantes do ensino fundamental que completaram questionários sobre autolesão, vitimização e cybervitimização. Foram realizadas análises descritivas, correlações e modelos de mediação. Os resultados revelaram associações positivas e significativas entre todas as variáveis, destacando-se que a autolesão leve mediou a relação entre a vitimização presencial e a autolesão severa, enquanto, no caso da cybervitimização, observou-se uma relação direta robusta com a autolesão severa, evidenciando um maior impacto das agressões digitais na intensificação do dano autoinfligido. Esses achados sugerem que a autolesão leve atua como um elo crítico na progressão para condutas graves, ressaltando a necessidade de intervenções precoces e específicas para prevenir a escalada do dano e suas relações patológicas.

Palavras-chave: adolescência; autolesão não suicida; cybervitimização; mediação; vitimização escolar.

Received: 1/05/2025

Accepted: 15/12/2025

Non-suicidal self-injury, as defined by Nock (2010) and in accordance with Liu et al. (2022), is understood as the deliberate, direct, and socially unacceptable destruction or damage of one’s own body tissue without suicidal intent. Although it has traditionally been considered a problem associated with clinical populations, its high prevalence in samples of adolescents from the general population has highlighted the need to more precisely define individual characteristics, as well as the contextual factors associated with this behavior (Esposito et al., 2019).

Self-injury can manifest at different levels of severity, ranging from mild forms to more severe forms that involve significant damage to body tissue. Mild self-injury is characterized by being less invasive and may include behaviors such as superficial scratching, pinching, or hitting that do not result in permanent damage. Unlike severe self-injury, these behaviors do not always serve a clear function of escape or immediate emotional regulation but may instead represent an incipient form of coping with emotional or social distress (Hooley et al., 2020; Marín, 2013).

Evidence suggests that mild self-injury is not an isolated phenomenon but rather may progressively evolve into more severe forms of self-injury, in which a clear escape function in response to aversive emotions or highly distressing situations is observed (John et al., 2017). This process of intensification may be partly explained by behavioral and emotional sensitization, whereby the repetition of self-injurious behaviors leads to a reduction in the initial aversion to pain and a gradual learning of its function as a coping mechanism (Santo & Dell’Aglio, 2022).

It is important to recognize that self-injury can manifest in both mild and severe forms, which helps to understand the phenomenon accurately and to estimate its incidence and prevalence with greater precision. For example, the study by Duarte and Fregoso (2024), conducted with a generalizable non-clinical sample of adolescent students, showed that 8.08 % engaged in severe self-injurious behaviors. Although this percentage may appear low, given that severe self-injury refers to serious forms of bodily harm, it represents a meaningful and relevant proportion when properly interpreted.

According to Faura-García et al. (2015), severe self-injurious behaviors are considered pathological, whereas mild self-injury refers to behaviors that are not necessarily linked to an immediate need to escape distress. However, even when mild self-injury is not directly associated with negative emotional events, its repeated occurrence may constitute a risk factor for the development of severe self-injury (Hooley et al., 2020).

In this sense, mild self-injury may act as a link in the relationship between adverse experiences and severe self-injury, functioning as an intermediate element that facilitates the transition toward more dangerous behaviors. Therefore, understanding mild self-injury as a key risk factor in the progression toward severe self-injury is essential (Plener et al., 2015). This perspective is crucial for accurately understanding the phenomenon and for developing prevention and intervention strategies aimed at halting this process before it evolves into more severe forms of self-inflicted harm.

Authors such as Klonsky (2007), Nock and Prinstein (2005), and Liu et al. (2022) have found that individuals engage in self-injurious behaviors as a strategy to reduce negative stimuli. Consequently, peer victimization constitutes an important factor in its development, as such behaviors may function as a means of regulating the distress generated by these negative experiences. As noted by Heilbron and Prinstein (2018), peer victimization is a problem that elicits a wide range of negative sensations and emotions among adolescents.

Resett and González (2020) reported that the association between self-injury and victimization is statistically significant and that peer school victimization significantly predicts self-injury (p < .001; β = .33). Similarly, Heilbron and Prinstein (2018) indicated that peer victimization constitutes a potential risk factor for the development of non-suicidal self-injury and suicide among adolescents, as interpersonal problems, such as peer rejection, and social isolation, are frequently cited as precipitating factors of self-directed violent behaviors. In their study, the authors identified significant differences between individuals who did not engage in self-injury and those who did, as a function of peer victimization, showing that adolescents who reported being victims were more likely to engage in self-injurious behaviors.

Along the same lines, an important variable to consider in the study of non-suicidal self-injury is interaction through digital media. For example, Duarte et al. (2023a) suggested that internet use may constitute a risk factor for non-suicidal self-injury, increasing its likelihood by 237 %.

It is evident that the internet has contributed to adolescent development by fostering personal identity formation, facilitating the establishment of interpersonal relationships, serving as a resource for obtaining social support, and providing access to a wide range of entertainment and leisure opportunities (Davis, 2013). However, it has also generated new risks, such as cyberbullying (Del Rey et al., 2016; Garaigordobil, 2017) and internet addiction.

The internet, as one of the most prevalent and rapidly expanding digital tools today, has transformed adolescents’ relationships with primary attachment figures, as it has become an important channel of communication, affecting the way parent–child communication is established due to the intergenerational digital gap (Yubero et al., 2018). This, in turn, suggests that peer interactions may manifest in interpersonal problems such as cyberbullying.

According to the Instituto Federal de Telecomunicaciones (2019), adolescents aged 12 to 17 have an 88.3 % probability of using the internet, while students have a 92.9 % probability, making them, as noted by Hernández and Alcoceba (2015), the group with the highest level of internet access.

Authors such as Vondrácková and Gabrhelik (2016) have indicated that internet access is widely available among adolescents and, therefore, excessive use is more likely, which may lead to outcomes such as emotional and psychological disorders or impairments. Another potential consequence is non-suicidal self-injury, making the relationship between self-injury and internet use in adolescents particularly relevant for investigation. Internet use does not intrinsically cause negative emotional outcomes; however, it increases the likelihood of engaging in interactions that may do so. Thus, digitally mediated interactions, such as cybervictimization, defined by Nocentini et al. (2010) as peer aggression occurring through the internet or mobile phones, manifested as written-verbal aggression, exclusion, and impersonation, also become highly relevant in the study of non-suicidal self-injury.

Based on the above, it is pertinent to consider theoretical frameworks that help explain how experiences of digital victimization may translate into self-injurious behaviors, particularly as these behaviors increase in severity. In this regard, the Barlett and Gentile Cyberbullying Model (BGCM; Barlett et al., 2021) proposes that repeated exposure to digital aggression reinforces beliefs such as perceived anonymity and the irrelevance of physical power, thereby facilitating the normalization of hostile online environments. Although the BGCM has primarily focused on explaining perpetration, its principles of social learning and emotional sensitization can be extrapolated to understand how sustained cybervictimization may erode psychological barriers to physical harm, promoting the emergence of self-injury as a coping strategy.

The BGCM (Barlett et al., 2021) is useful for the study of victimization, as its core mechanisms, such as social learning, repeated exposure, and the normalization of hostile environments, also operate from the perspective of those who receive aggression. Continuous immersion in such environments can lead to emotional desensitization, thereby increasing the likelihood of psychological impairment. For this reason, extrapolating this model to the victim’s perspective is theoretically reasonable when the shared conceptual bridges between perpetrator and victim are made explicit. As noted by Fawson et al. (2018), it is possible to observe role transitions (from aggressor to victim or from victim to aggressor), with such transitions representing one of the potential effects of aggression; for example, a victim may become an aggressor as an emotional or psychological mechanism to adapt to their environment.

Accordingly, authors such as Liu et al. (2023), Drubina et al. (2023), and Lin et al. (2023), among others, have demonstrated through structural equation modeling that cybervictimization significantly predicts non-suicidal self-injury. In addition, the systematic review conducted by Predescu et al. (2024), which included 20 studies that empirically and explanatorily examined the relationship between cybervictimization and non-suicidal self-injury, concluded that cybervictimization constitutes an important risk factor when studying non-suicidal self-injury among children and adolescents.

These findings are highly relevant, as the prevalence rates of both cybervictimization and in-person victimization are concerning. For example, the meta-analysis conducted by Domínguez-Alonso et al. (2023) reported a cybervictimization prevalence of 22.18 % among adolescents who use the internet. In a similar population, Degue et al. (2024) reported that the prevalence of in-person victimization was 34.6 %. Likewise, Vega-Cauich (2018) analyzed a sample of 18,839 youth aged 12 to 29 years and found that the prevalence of cybervictimization among high school students (adolescents aged 15 to 17 years) was 26 %. Taken together, these figures indicate a substantial presence of victimization and cybervictimization among adolescents.

Considering the reviewed background, the aim of this study is to examine the relationship between non-suicidal self-injury and both in-person victimization and cybervictimization. It is hypothesized that cybervictimization and victimization influence severe self-injurious behaviors when mediated by mild self-injurious behaviors. It is also hypothesized that cybervictimization has greater explanatory power than in-person victimization in predicting self-injurious behaviors (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Conceptual model for the mediation analysis, in which cybervictimization, verbal/relational victimization, and physical/social victimization are specified as independent variables, mild self-injury as the mediating variable, and severe self-injury as the dependent variable

Method

Participants

The sample was selected using

cluster random sampling and consisted of 433 adolescents enrolled in 19 public

secondary schools located in the city of Hermosillo, Sonora. Of the total

sample, 184 adolescents (42.5 %) were in the second grade and 249

(57.5 %) were in the third grade; 211 (48.7 %) were male and 222

(52.3 %) were female. Regarding school shift, 358 students (82.7 %)

attended the morning shift and 75 (17.3 %) attended the afternoon shift.

It should be noted that schools were randomly selected until 10 % of the

schools in the region were included to obtain a representative sample, a minimum

of 384 students were required to achieve a 95 % confidence level and a

5 % margin of error, based on a known population of 130,044 students in

the region.

Regarding inclusion criteria, participants were required to be enrolled in the selected schools. Exclusion criteria included having a diagnosis related to neurodivergence, completing less than 90 % of the questionnaire items, and the presence of random response patterns.

Instruments

Self-Injury Inventory (SII): This questionnaire was developed by Marín (2013) and consists of 12 items designed to detect and temporally measure both mild and severe self-injurious behaviors. Responses are rated on a five-point Likert-type scale (0 = never, 1 = once, 2–4 times, 5–9 times, and 10 times or more). For the population of Sonora, an Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) was conducted, yielding a Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin (KMO) value of .93, a total variance explained (TVE) of 48.27 %, factor loadings ranging from .61 to .78, and a Cronbach’s alpha of .89. Seven items correspond to mild self-injury and five items to severe self-injury. In turn, the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) yielded adequate fit indices (CFI = .93; RMSEA = .07; SRMR = .04) (Duarte et al., 2023b).

Cyberbullying Test: This scale was developed by Garaigordobil (2017) to assess the phenomenon of cyberaggression and consists of 45 items distributed across three dimensions. For the present study, the adaptation by Navarro-Rodríguez et al. (2023) was used, and only the cybervictimization dimension, composed of 12 items, was included. This adaptation was conducted with a sample of secondary school students in Sonora using Rasch analysis and Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA), yielding infit values ranging from .75 to 1.42, outfit values ranging from .58 to 1.44, and adequate model fit indices (CFI = .94; RMSEA = .04; SRMR = .03), as well as high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha = .92). These statistics indicate a good fit of the instrument.

Aggressors and Victims Scale: This scale was developed by Del Rey and Ortega (2007) to assess peer aggressive behavior and comprises two dimensions: aggression and victimization. For the present study, the version adapted by González et al. (2017) was used, which tailored the instrument for secondary school students in Sonora. The two victimization dimensions were included: verbal/relational victimization and physical/social victimization, consisting of seven and five items, respectively, rated on a five-point Likert scale. Rasch analysis yielded infit values ranging from .54 to 1.35 and outfit values ranging from .75 to 1.24, while Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) produced acceptable fit indices (CFI = .90; RMSEA = .08; SRMR = .05), indicating an adequate fit of the instrument for measuring victimization.

Procedures

To collect the data, authorization was obtained from the Ministry of Public Education, which granted access to the participating educational institutions. Following this approval, visits were made to the selected secondary schools, and permission was requested to enter the classrooms. Within the classrooms, a trained survey administrator, who was a psychologist affiliated with a research project, provided informed consent to explain the objectives of the study, ensure data confidentiality, and clarify that participants’ names would not be disclosed, as analyses would be conducted at a group level. Likewise, the educational institutions were responsible for informing parents and guardians in advance. The survey administrator also conducted the data collection by providing students with a booklet containing the questions and response options, along with a separate answer sheet on which participants could indicate their selected responses. Instructions on how to complete the questionnaire were given, and any questions from the students were addressed. The administration time was approximately 50 minutes per group.

Data Analysis

First, univariate descriptive analyses were conducted to obtain measures of central tendency. Subsequently, Pearson correlation analyses were performed among the study variables to identify relevant bivariate associations and to provide an initial approximation to the proposed model.

To evaluate the mediating role of mild self-injury in the relationship between offline victimization and cybervictimization and severe self-injury, mediation models were conducted using a regression-based approach. Specifically, Model 4 (simple mediation) from Hayes (2022) was employed. This model is designed to determine whether the effect of an independent variable (X) on a dependent variable (Y) occurs directly or whether this effect is explained by a third variable, the mediator (M), that is, whether an indirect effect is present. The indirect effect refers to the effect of X on Y through M. Model adequacy was evaluated using the regression coefficients (β) for X à M, M à Y, and X à Y (direct effect); the product β (X à M) * β (M à Y) (indirect effect); and the total effect. Statistical significance (p < .05) and R² (proportion of explained variance) were also examined. A mediation model was considered acceptable when the M à Y effect was larger than the X à M effect, the total effect exceeded the direct effect, and the indirect effect was present. All effects were required to be statistically significant. Additionally, assumptions of normality were not required, as bootstrapping-based estimates do not rely on this assumption (Hayes, 2022).

It is important to note that prior to conducting the mediation analyses, the assumptions associated with regression models were examined. Linearity between the variables was verified, as no curvilinear patterns were observed. Independence of errors was assessed using the Durbin–Watson statistic, which fell within the acceptable range for each model (1.50–2.50). The absence of multicollinearity was confirmed by variance inflation factor (VIF) values below 5 and tolerance values above .20. In addition, homoscedasticity was evaluated through residual analysis (Hayes, 2022).

To conduct the analyses described above, SPSS version 25 with the PROCESS macro version 3.5 was used. Additionally, RStudio version 4.0.3 was employed for the descriptive and correlational analyses.

Results

First, descriptive analyses of the study variables are presented in terms of mean (M), standard deviation (SD), minimum, maximum, as well as skewness and kurtosis. It is important to note that, according to the criteria proposed by Kim (2013), the variables can be considered to approximate normality, as their skewness and kurtosis values do not exceed ±7 (Table 1).

Table 1: Descriptive analyses of the study variables

Note: N = 433. M: Mean; SD: Standard deviation.

Subsequently, correlation analyses were conducted among the study variables (Table 2). The correlation analyses revealed positive and statistically significant associations among all variables examined. A moderate correlation was observed between mild and severe self-injury (r = .46, p < .01), as well as weaker but consistent associations between cybervictimization and mild self-injury (r = .23, p < .01) and severe self-injury (r = .26, p < .01). Physical/social victimization showed the strongest correlation with verbal/relational victimization (r = .64, p < .01), suggesting an overlap between these forms of aggression.

Table 2: Correlations among the study variables

Note: N = 433. **p < .001

Subsequently, in order to fulfill the stated objective and test the proposed hypotheses, three mediation analyses were conducted using the different model configurations, as illustrated in Figure 1. Figure 2 presents the mediation model of cybervictimization on severe self-injury through mild self-injury. The results showed that cybervictimization had a statistically significant effect on mild self-injury (β = .22, SD = .04, p < .001, 95 % CI (.13, .32)), and that mild self-injury, in turn, had a statistically significant effect on severe self-injury (β = .26, SD = .02, p < .001, 95 % CI (.20, .31)). The total effect of cybervictimization on severe self-injury, mediated by mild self-injury, was significant (β = .16, SD = .02, p < .001, 95 % CI (.10, .22)). Moreover, the direct effect of cybervictimization on severe self-injury was smaller (β = .10, SD = .02, p < .001, 95 % CI (.05, .15)) than the total effect. The indirect effect of cybervictimization through mild self-injury was also significant, with β = .06 (SD = .02), 95 % CI (.01, .12). The variance explained by the model was R² = .26. Considering the magnitude of the indirect and total effects relative to the direct effect, the results confirm the presence of a mediation effect.

Figure 2: Mediation model for cybervictimization, mild self-injury, and severe self-injury

Note: SI: Self-Injury; D: Direct effect.

*** p < .001

Figure 3 presents the mediation model of verbal/relational victimization on severe self-injury through mild self-injury. The results showed that verbal/relational victimization had a statistically significant effect on mild self-injury (β = .12, SD = .02, p < .001, 95 % CI (.07, .16)), and that mild self-injury, in turn, had a statistically significant effect on severe self-injury (β = .28, SD = .02, p < .001, 95 % CI (.22, .33)). The total effect of verbal/relational victimization on severe self-injury mediated by mild self-injury was significant (β = .04, SD = .01, p < .05, 95 % CI (.02, .07)). However, the direct effect of verbal/relational victimization on severe self-injury was smaller and non-significant (β = .01, SD = .01, p = .27, 95 % CI (−.01, .04)) compared to the total effect. The indirect effect of verbal/relational victimization through mild self-injury was also significant, with β = .03 (SD = .01), 95 % CI (.01, .06). The variance explained by the model was R² = .21. Considering the magnitude of the indirect and total effects relative to the direct effect, the results indicate the presence of a mediation effect. However, it is important to note that, although statistically significant, the total effect size was small.

Figure 3: Mediation model for verbal/relational victimization, mild self-injury, and severe self-injury

Note: SI: Self-Injury; D: Direct effect; VR: Verbal/Relational. *** p < .001; *p < .05

Figure 4 presents the mediation model of physical/social victimization on severe self-injury through mild self-injury. The results showed that physical/social victimization had a statistically significant effect on mild self-injury (β = .16, SD = .03, p < .001, 95 % CI (.10, .23)), and that mild self-injury, in turn, had a statistically significant effect on severe self-injury (β = .27, SD = .02, p < .001, 95 % CI (.21, .32)). The total effect of physical/social victimization on severe self-injury mediated by mild self-injury was significant (β = .08, SD = .02, p < .001, 95 % CI (.04, .12)). In addition, the direct effect of physical/social victimization on severe self-injury was smaller but statistically significant (β = .03, SD = .01, p < .05, 95 % CI (.002, .07)) compared to the total effect. The indirect effect of physical/social victimization through mild self-injury was also significant, with β = .04 (SD = .01), 95 % CI (.01, .08). The variance explained by the model was R² = .21. Considering the magnitude of the indirect and total effects relative to the direct effect, the results confirm the presence of a mediation effect. However, it should be noted that, although statistically significant, the total effect size of the model was small.