Ciencias Psicológicas; v19(2)

Julio-diciembre 2025

10.22235/cp.v19i2.4543

Trolling en redes sociales. Bienestar psicológico y personalidad normal, patológica y positiva

Trolling on Social Media. Psychological Well-being and Normal, Pathological, and Positive Personality

Trolling nas redes sociais. Bem-estar psicológico e personalidade normal, patológica e positiva

Alejandro Castro Solano1, ORCID 0000-0002-4639-3706

María Laura Lupano Perugini2, ORCID 0000-0001-6090-0762

1 Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas; Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina, [email protected]

2 Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas; Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina

Resumen:

Objetivo. Este estudio examinó la relación entre la recepción de comentarios negativos en redes sociales, el bienestar psicológico y los rasgos de personalidad normales, patológicos y positivos. Método. Participaron 799 usuarios de redes sociales residentes en Argentina (338 varones, 461 mujeres; M = 39.7 años, DE = 13.84). Se emplearon los instrumentos: Big Five Inventory, Mental Health Continuum-Short Form, Inventario de los Cinco Continuos de la Personalidad - versión breve y una encuesta ad hoc sobre recepción de comentarios negativos en redes sociales. El diseño fue transversal, no experimental y correlacional. Resultados. La frecuencia de comentarios negativos fue inferior al 10 % en todas las redes sociales analizadas. El grado de malestar autopercibido se asoció significativamente con el uso activo de redes sociales (r = .24, p < .001) y con niveles más bajos de bienestar psicológico (r = -.30, p < .001). Los rasgos de personalidad normal explicaron el 9 % de la varianza del grado de malestar y, al incorporar los rasgos patológicos y positivos, adicionaron en total 10 %. Conclusiones. El malestar debido a la recepción de comentarios negativos en redes sociales está asociado con un menor bienestar y con un perfil de personalidad vinculado con el neuroticismo y el afecto negativo. La inclusión de rasgos patológicos y positivos mejora la explicación del malestar más allá de los rasgos normales.

Palabras clave: trolling; rasgos positivos; rasgos patológicos; rasgos normales; bienestar psicológico.

Abstract:

Objective. This study examined the relationships among the reception of negative comments on social media; psychological well-being; and normal, pathological, and positive personality traits. Method. A total of 799 social media users residing in Argentina participated (338 men, 461 women; M = 39.7 years, SD = 13.84). The following instruments were used: the Big Five Inventory, the Mental Health Continuum–Short Form, the Inventory of the Five Personality Continuums–Short Version, and an ad hoc survey on the reception of negative comments on social media. The design was cross-sectional, nonexperimental, and correlational. The results. The frequency of negative comments was less than 10 % across all analyzed social media platforms. The degree of self-perceived distress was significantly associated with active use of social media (r = .24, p < .001) and with lower levels of psychological well-being (r = -.30, p < .001). Normal personality traits explained 9 % of the variance in the level of distress; when pathological and positive traits were added, they accounted for an additional 10 % of the total. Conclusions. Distress associated with the reception of negative comments on social media is linked to lower well-being and to a personality profile characterized by neuroticism and negative affect. The inclusion of pathological and positive traits improves the explanation of distress beyond normal traits.

Keywords: trolling; positive personality traits; pathological personality traits; normal personality traits; psychological well-being.

Resumo:

Objetivo. Este estudo examinou a relação entre a recepção de comentários negativos nas redes sociais, o bem-estar psicológico e os traços de personalidade normais, patológicos e positivos. Método. Participaram 799 usuários de redes sociais residentes na Argentina (338 homens, 461 mulheres; M = 39,7 anos, DP = 13,84). Foram utilizados os instrumentos: Big Five Inventory, Mental Health Continuum-Short Form, Inventário dos Cinco Contínuos da Personalidade- versão breve, e um questionário ad hoc sobre a recepção de comentários negativos em redes sociais. O delineamento foi transversal, não experimental e correlacional. Resultados. A frequência de comentários negativos foi inferior a 10 % em todas as redes sociais analisadas. O grau de mal-estar autopercebido associou-se significativamente ao uso ativo de redes sociais (r = 0,24, p < 0,001) e a níveis mais baixos de bem-estar psicológico (r = -0,30, p < 0,001). Os traços de personalidade normal explicaram 9 % da variância do grau de mal-estar; ao incorporar os traços patológicos e positivos, adicionaram no total 10 %. Conclusões. O mal-estar vinculado à recepção de comentários negativos nas redes sociais está associado a menor bem-estar e a um perfil de personalidade marcado pelo neuroticismo e pelo afeto negativo. A inclusão de traços patológicos e positivos melhora a explicação do mal-estar para além dos traços normais.

Palavras-chave: trolling; traços positivos; traços patológicos; traços normais; bem-estar psicológico.

Recibido: 26/03/2025

Aceptado: 12/09/2025

La comunicación por medio de redes sociales se impuso como una modalidad desde hace ya varios años. A pesar de las ventajas que esto pueda conllevar, las investigaciones muestran que el uso de redes sociales tiene su lado oscuro (Sands et al., 2020). En esta investigación haremos referencia al fenómeno conocido como trolling, que puede entenderse, no solo como una conducta disruptiva, sino como una forma de ocio oscuro en tanto implica una actividad recreativa que, aunque transgresora, se realiza por placer y entretenimiento (Scriven, 2025).

No existe una definición precisa sobre el término trolling y se observan discrepancias a la hora de definirlo que, incluso, pueden diferir de la opinión general que tienen las personas sobre lo que significa (Ortiz, 2020). Sin embargo, la mayoría de los autores consideran que es un término global que abarca un espectro de conductas y motivaciones multicausales que resultan antagónicas, antisociales o desviadas en cuanto al comportamiento online (Buckels et al., 2014; Buckels et al., 2018, Hardaker, 2010; Phillips, 2015; Sanfilippo et al., 2018). Estas conductas se ven potenciadas por el anonimato con el que se pueden realizar estas intervenciones (Nitschinsk et al., 2023; Suler, 2004). En general, los trolls no suelen presentar una intencionalidad bien definida, solo buscan molestar y generar interferencias en la comunicación (Hardaker, 2010). Por lo tanto, si los usuarios responden a los comentarios y posteos hechos por trolls, lo más probable es que entren en una espiral de comentarios no constructivos (Paakki et al., 2021).

De acuerdo con algunos investigadores, este tipo de conductas disruptivas online representan solo una forma de trolling denominada kudos trolling. Sin embargo, el trolling ha evolucionado desde provocar a otros por el disfrute y el entretenimiento mutuos hasta un comportamiento más abusivo, agresivo y reactivo que no pretende ser gracioso, llamado flame trolling (Bishop, 2014; Komaç & Çağıltay, 2019; March & Marrington, 2019). Asimismo, existe otro tipo de usuarios, llamados silent trolls, que se caracterizan por no ejercer comportamientos de trolling, pero sí ser espectadores de ese tipo de conductas. Incluso los llamados supportive trolls no solo observan, sino que pueden dar likes a conductas de trolling ejercidas por otros, fomentando indirectamente que estos comportamientos sigan proliferando (Brubaker et al., 2021; Montez & Kim, 2025; Ubaradka & Khanganba, 2024).

En el ámbito de la política, son conocidas las trolls farms —granjas de trolls—, que tienen como función manipular a los votantes mediante posteos o comentarios en redes sociales (Denter & Ginzburg, 2021). Investigaciones recientes incluyen el análisis de conductas troll colectivas, impulsadas por el anonimato y cuya repetición masiva de comportamientos disruptivos (por ejemplo, comentarios, posteos) contra un individuo o grupo incrementa la intensidad del perjuicio provocado (Flores-Saviaga et al., 2018; Sun & Fichman, 2019; Truong & Chen, 2024).

También debe considerarse que el tipo de conducta troll que se ejerza puede variar según el tipo de red social o comunidad a la que pertenezca el usuario que las perpetra (Fichman & Sanfilippo, 2016). Por lo general, el trolling es más usual en posteos o publicaciones que involucren a la política o a acontecimientos de actualidad (Jatmiko, 2024; Seigfried-Spellar & Chowdhury, 2017). Por lo tanto, muchas veces el contexto de la discusión online puede favorecer que muchos usuarios muestren conductas troll más allá de sus características personales (Bentley & Cowan, 2021).

Hay evidencia de que las figuras públicas (por ejemplo, políticos, artistas, etcétera) corren un mayor riesgo de ser amenazadas y acosadas (Akhtar & Morrison, 2019; Hoffmann & Sheridan, 2008a; 2008b; James et al., 2016). Sin embargo, cualquier usuario puede ser víctima de estas intervenciones agresivas. De acuerdo con algunas cifras internacionales, el 41 % de los usuarios de internet ha sufrido personalmente algún tipo de hostigamiento online que va desde insultos hasta distintas formas de acoso (Pew Research Center, 2021). Al analizar los perfiles de las figuras públicas, esa cifra crece exponencialmente. Por ejemplo, en una investigación con miembros del Parlamento en Reino Unido se halló que el 100 % de los encuestados había recibido agresiones de parte de trolls, siendo las cuentas de usuarios hombres las más atacadas. En cambio, las mujeres sufrían más agresiones con connotación sexual (Akhtar & Morrison, 2019). En una encuesta reciente realizada en Argentina a partir de una muestra de 877 mujeres, el 33 % respondió haber sufrido algún tipo de agresión por medio de redes sociales, especialmente con connotación sexual (por ejemplo, recibir contenido inadecuado o burlas y agresiones) (Defensoría del Pueblo de la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, 2024).

Diversas investigaciones a nivel internacional intentan explicar las causas y consecuencias de este fenómeno. Existen variados aspectos que pueden hacer que un usuario se convierta en un troll. Uno de estos puede vincularse con factores de personalidad. En cuanto a rasgos normales de la personalidad, el Five Factor Model (FFM; Costa & McCrae, 1985) es tomado por la mayoría de las investigaciones vinculadas con la psicología de internet. En relación con el fenómeno del trolling, investigaciones internacionales muestran correlaciones negativas con los rasgos de la responsabilidad y la amabilidad, lo que da cuenta de que se trata de usuarios poco confiables y negligentes (Buckels et al., 2014; March et al., 2023). En Argentina se encontró el mismo tipo de relación (Lupano Perugini & Castro Solano, 2021, 2023).

Para el abordaje de rasgos positivos y patológicos, en investigaciones realizadas en Argentina se utilizó un modelo desarrollado localmente: Positive Personality Model (PPM; De la Iglesia & Castro Solano, 2018). Este representa un intento de integración con los rasgos psicopatológicos propuestos en la sección III del DSM-5 (Afecto Negativo, Desapego, Antagonismo, Desinhibición y Psicoticismo), e incorpora versiones positivas de estos rasgos. Los rasgos positivos son: Serenidad, Humanidad, Integridad, Moderación y Vivacidad y foco. Estos cinco se ubican en el continuum de salud-enfermedad y constituyen un polo adicional ubicado más allá de la normalidad: el polo positivo. Las investigaciones hallaron correlaciones negativas entre estos rasgos y la conducta troll. En tanto que, de los rasgos patológicos, Desinhibición es el que mostró mayor injerencia (Lupano Perugini & Castro Solano, 2021, 2023).

En este estudio se presenta como novedad analizar los perfiles de la personalidad de los usuarios que son víctimas de trolling y cómo perciben que esto impacta en su bienestar psicológico. En relación con el impacto emocional, los resultados de las investigaciones suelen ser contrapuestos (por ejemplo, Frison & Eggermont, 2015; Kraut et al., 2002; Lup et al., 2015; Nie et al., 2015). Es bien conocido el efecto llamado Internet Paradox, planteado por Kraut et al. (1998), que sostiene que la tecnología diseñada para favorecer la comunicación interpersonal termina generando el efecto contrario cuando se la usa excesivamente. Sin embargo, un estudio posterior de seguimiento mostró que este efecto se disipaba (Kraut et al., 2002) y que el uso de internet tiene diferentes efectos en función de los rasgos de la personalidad de los usuarios. Es por esta razón que es importante el estudio conjunto de ambos tipos de variables. Si bien los hallazgos son contradictorios, las investigaciones tienden a coincidir en que usar excesivamente las redes sociales se asocia con una mayor presencia de sintomatología depresiva y de ansiedad social (por ejemplo, Blease, 2015; Lupano Perugini & Castro Solano, 2019; Shaw et al., 2015; Stover et al., 2023). Una revisión reciente realizada por Zubair et al. (2023) confirma la vinculación entre el uso excesivo y la tendencia a experimentar síntomas psicopatológicos, y aporta que la pandemia por covid-19 intensificó aún más el uso de los medios digitales de comunicación propiciando el desarrollo de estos síntomas.

El efecto psicológico que puede ocasionar sufrir agresiones online fue estudiado principalmente en víctimas de ciberbullying —niños— y cibermobbing —adultos—. El problema con las agresiones online es que se diseminan de forma más rápida, masiva, y el contenido agresivo puede permanecer mucho tiempo en el ciberespacio generando un perjuicio aún mayor (Mathew et al., 2019). Las investigaciones muestran que las víctimas pueden sufrir depresión, ansiedad, pensamientos suicidas, baja estima, entre otras consecuencias (Kowalski et al., 2017; Laboy-Vélez et al., 2021; Pacheco, 2022; Tristão et al., 2022). En el caso del trolling, los victimarios solo buscan gratificación personal, sin importar la angustia que pueden ocasionar en sus víctimas (Craker & March 2016; Golf-Papez & Veer, 2017). Sin embargo, el trolling puede tener graves consecuencias para las víctimas, quienes reportan un aumento de ideas suicidas y conductas de autolesión (Coles & West, 2016).

En este estudio se analiza la relación entre el bienestar psicológico y la recepción de los comentarios negativos en las redes sociales, así como el papel que desempeñan los rasgos de la personalidad en esta relación. En los objetivos se utiliza la expresión comentarios negativos, ya que es la forma en la que se consultó a los participantes si eran víctimas de conducta troll, dado que es probable que muchos no identificaran el término o no le dieran el significado que se le adjudica en las investigaciones sobre la temática, tal como sostiene Ortiz (2020). Por lo tanto, adoptamos una definición amplia del término trolling que puede incluir tanto burlas como comentarios agresivos.

Lo aquí estudiado resulta novedoso, ya que, como se mencionó, las investigaciones previas han analizado este aspecto principalmente en víctimas de ciberbullying que son conocidas por sus agresores y hay una clara intención de generar daño (Sest & March, 2017). En cambio, las víctimas de trolling, si bien pueden ser personas públicas, también pueden ser usuarios anónimos, en los que no existe un conocimiento previo de ninguna de las partes (víctima-perpetrador) (Fichman & Sanfilippo, 2016).

Por otro lado, en los últimos años se comenzaron a estudiar aspectos vinculados con el uso de internet y las redes sociales mediante el empleo de metodologías novedosas como el natural language processing y el machine learning. Por ejemplo, Machova et al. (2022) usaron métodos de aprendizaje automático para generar modelos de detección para discriminar entre usuarios trolls y usuarios comunes. Asimismo, emplearon métodos de sentiment analysis para reconocer el sentimiento típico de los comentarios de un troll. En otra investigación, Shekhar et al. (2021) usaron la técnica HLSTM —Self-Learning Hierarchical LSTM Technique—, inspirada en los modelos de aprendizaje neuronal, para clasificar comentarios de odio y trolling en redes sociales.

En esta investigación se utiliza el análisis automático de textos para examinar las respuestas a preguntas abiertas brindadas por participantes que indicaron ser usuarios de redes sociales. Estas respuestas fueron recolectadas mediante una encuesta administrada específicamente en el marco de esta investigación. Esta metodología se encuadra dentro de las herramientas de análisis de textos automáticos denominadas abiertas que emplean algoritmos especializados de machine learning para dar sentido a una gran cantidad de datos de naturaleza inestructurada (Iliev et al., 2015). Su uso comenzó a popularizarse en psicología y se lo emplea especialmente con propósitos predictivos (Yarkoni & Westfall, 2017), por ejemplo, para identificar rasgos de personalidad a través de los posteos en las redes (Bleidorn & Hopwood, 2019; Park et al., 2015). Clásicamente, en psicología, para extraer los temas latentes derivados de las respuestas textuales abiertas provistas por los usuarios, se utilizaba el análisis temático. Esta metodología tiene la dificultad de reposar sobre el criterio subjetivo de jueces expertos y no resulta demasiado útil cuando el investigador tiene la necesidad de analizar una gran cantidad de datos. Los algoritmos informáticos comentados permiten analizar de modo más objetivo la información aportada por los participantes, y maximizan el ahorro de tiempo y dinero en el procesamiento de la información (Lamba & Madhusudhan, 2019).

El aporte de esta investigación recae, entonces, en tres puntos principales: en primer lugar, analizar cómo reaccionan los usuarios que son víctimas de comentarios asociados con conductas troll, en contraste con el ciberbullying, que ha recibido mayor atención en la literatura; en segundo lugar, examinar el rol de los rasgos de la personalidad menos explorados —tanto positivos como negativos— en la percepción del impacto sobre el bienestar en comparación con los rasgos más tradicionales; y, en tercer lugar, incorporar el análisis automático de textos como una herramienta metodológica innovadora.

En virtud de lo expuesto, se plantearon los siguientes objetivos: (1) analizar la frecuencia de los comentarios negativos recibidos por los usuarios de las redes sociales según la red social utilizada, el origen y el tipo de comentario; (2) indagar los motivos por los que los participantes perciben que reciben comentarios negativos, qué acción personal realizan y qué opinión tienen sobre estos; (3) examinar la relación entre la intensidad de los comentarios negativos recibidos y el bienestar psicológico percibido (personal, emocional y social); y (4) examinar la capacidad predictiva de las variables de la personalidad (rasgos normales, patológicos y positivos) sobre el grado de impacto percibido por los usuarios respecto de los comentarios negativos recibidos.

Método

El presente estudio se enmarca en un diseño cuantitativo, no experimental y transversal, con un alcance descriptivo-correlacional.

Participantes

Se trata de una muestra de conveniencia compuesta por 799 personas usuarias de redes sociales (338 hombres, 42.3 % y 461 mujeres, 57.7 %) con un promedio de 39.7 años (DE = 13.84). El 7.1 % (n = 57) de la muestra son extranjeros residentes en Argentina. En su mayor parte, trabajadores (n = 629, 78.8 %). En cuanto al nivel de estudios, el 38 % (n = 303) refiere tener estudios universitarios o terciarios completos. Entre ellos, el 12.5 % (n = 38) tiene estudios de posgrado completos. El 14 % (n = 112) indica tener el secundario completo. La mayoría de los participantes se autodescribe con un nivel socioeconómico medio (n = 474; 59.4 %) y medio-alto (n = 138; 17.3 %).

Asimismo, se encuestó sobre la cantidad de horas al día en las que realizan actividades que requieren conexión (1: No uso internet; 2: Menos de una hora; 3: 1 hora; 4: 2 horas, y así sucesivamente hasta 24 horas). El tiempo promedio de conexión fue de 8.12 horas (DE = 4.75).

Materiales

Encuesta comentarios negativos en redes sociales. Encuesta de elaboración propia, basada en los contenidos y el formato de una encuesta sobre comentarios negativos y experiencias de trolling (Akhtar & Morrison, 2019), que fue adaptada a la población local en cuanto a la terminología y los ejemplos de las redes sociales de uso frecuente. Dado que el cuestionario incluye tanto preguntas cerradas como abiertas orientadas a relevar experiencias específicas, no se trata de una escala estandarizada de medición de constructos latentes. Por esta razón, no cuenta con estudios de fiabilidad y validez, ni en su versión original ni en la presente adaptación, ya que su propósito es exploratorio y descriptivo, centrado en la obtención de información factual autorreportada sobre el uso de redes y la recepción de comentarios negativos. La primera parte de la encuesta exploraba acerca del tipo de red social utilizada, el tiempo de uso y la acción mayormente llevada a cabo en cada red social, seguido, finalmente, de los comentarios negativos recibidos en cada una de ellas. Se optó por individualizar cada red, ya que la mayor parte de los estudios dan cuenta del uso específico de alguna en particular, en especial Facebook (por ejemplo, Ellison et al., 2007). En cada una de las redes sociales listadas se les solicitó a los participantes que indicaran en un formato de respuesta Likert el tiempo de uso (1: No la uso a 8: La uso más de 4 horas al día); si recibían comentarios negativos (1: Nunca recibo a 5: Recibo todo el tiempo); si realizaban transmisiones en vivo, historias, reels (1: Nunca a 7: Casi todo el tiempo); el impacto negativo que percibían que tenían los comentarios negativos recibidos por esa actividad (1: No me impacta nada a 5: Me impacta mucho); si posteaban en cuentas de otras personas (1: Nunca a 5: Siempre); y el impacto percibido de recibir comentarios negativos en esos posteos (1: No me impacta nada a 5: Me impacta mucho). Finalmente, se encuestó sobre el impacto general percibido respecto de haber recibido comentarios negativos en las redes sociales (1: No me impacta nada a 5: Me impacta mucho). En la segunda parte, se consultaba si el comentario negativo procedía de una cuenta identificable o no, el contenido del comentario (por ejemplo, información falsa, político, aspecto físico, racial, sexual) y la acción mayormente realizada respecto de este (por ejemplo, lo leo y no lo respondo; lo leo y a veces respondo; lo leo completo; lo leo y lo respondo siempre). En la tercera parte se hicieron tres preguntas con formato de respuesta libre con el propósito de indagar, en primer lugar, por qué les parecía que recibían comentarios negativos, en segundo lugar, qué acción realizan una vez recibidos esos comentarios y, en tercer lugar, se les daba la opción de hacer un comentario libre sobre la temática. Finalmente, se solicitaban datos sociodemográficos (por ejemplo, género, edad, lugar de residencia, nivel de estudios, ocupación y nivel socioeconómico).

Big Five Inventory (BFI; John et al., 1991; adaptación argentina: Castro Solano & Casullo, 2001). Consiste en un instrumento de 44 ítems, que se responden con una escala Likert de cinco opciones (1: Totalmente en desacuerdo a 5: Totalmente de acuerdo). Evalúa los cinco grandes rasgos de la personalidad (extraversión, agradabilidad, responsabilidad, neuroticismo, apertura a la experiencia). Los autores de la técnica demostraron su validez y fiabilidad en grupos de población general adulta norteamericana. Esos estudios verificaron la validez concurrente con otros instrumentos reconocidos que evalúan la personalidad. Estudios en Argentina verificaron la validez factorial de los instrumentos para población adolescente, población adulta no consultante y población militar (Castro Solano & Casullo, 2001). En todos los casos se obtuvo un modelo de cinco factores que explicaban alrededor del 50 % de la variancia de las puntuaciones. Para esta muestra se obtuvieron valores de consistencia interna: extraversión: α = .79, ω = .79; agradabilidad: α = .70, ω = .72; responsabilidad: α = .81, ω = .82; neuroticismo: α = .85, ω = .83; apertura a la experiencia: α = .79, ω = .82.

Inventario de los Cinco Continuos de la Personalidad - versión corta (ICCP-SF; De la Iglesia & Castro Solano, 2023). Este instrumento fue construido para su uso en población argentina y es una operacionalización del Modelo Dual de la Personalidad con el que se miden cinco rasgos positivos (serenidad, humanidad, integridad, moderación y vivacidad y foco) y cinco rasgos patológicos (afecto negativo, desapego, antagonismo, desinhibición y psicoticismo). Cuenta con 55 elementos que se responden con una escala Likert de grado de acuerdo a seis opciones (0: Totalmente en desacuerdo a 5: Totalmente de acuerdo). Sus estudios psicométricos incluyeron análisis factoriales exploratorios y confirmatorios, análisis de consistencia interna (mediante alfas de Cronbach y omegas de McDonalds), estudio de validez convergente con medidas de rasgos positivos, patológicos y normales, y análisis de validez externa con indicadores relevantes (bienestar y sintomatología psicológica). Para esta muestra, los valores de α para las escalas de rasgos oscilaron entre .76 y .90, y los de ω, entre .87 y .93.

Mental Health Continuum - Short Form (MHC-SF; Keyes, 2005; adaptación argentina: Lupano Perugini et al., 2017). Este instrumento de 14 ítems evalúa el grado de: a) Bienestar emocional entendido en términos de afectos positivos y satisfacción con la vida (bienestar hedónico); b) Bienestar social (incluye las facetas de aceptación, actualización, contribución social, coherencia e integración social); c) Bienestar personal en términos de la teoría de Ryff (1989) (autonomía, control, crecimiento personal, relaciones personales, autoaceptación y propósito). Los ítems indagan con qué frecuencia ha experimentado ciertas emociones en una Likert que va de 0: Nunca a 5: Todos los días. Los estudios de validación de este instrumento en Argentina han confirmado la estructura de tres factores y su invarianza por sexo y edad. Además, se obtuvieron evidencias de validez convergente y divergente (Lupano Perugini et al., 2017). La fiabilidad por escala para esta muestra fue: bienestar emocional: α = .84, ω = .85; bienestar social: α = .75, ω = .77; bienestar personal: α = .85, ω = .85.

Procedimiento

Los datos fueron recolectados por estudiantes avanzados que se encontraban realizando una práctica de investigación en una universidad privada de la ciudad de Buenos Aires, Argentina. Los participantes fueron voluntarios y no recibieron retribución alguna por su colaboración. Las encuestas se administraron online mediante la aplicación SurveyMonkey. En la página de inicio de la encuesta se solicitaba el consentimiento del participante, se aseguraba el anonimato de los datos y su uso exclusivo para la investigación. La recogida de los datos fue supervisada por un docente investigador. La investigación siguió los lineamientos éticos internacionales (APA y NC3R) y del Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (Conicet) para el comportamiento ético en las Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades (Resolución N.° 2857/2006).

Análisis de datos

Se calcularon estadísticos descriptivos y correlaciones de Spearman para examinar las asociaciones entre variables, además de pruebas z con corrección de Holm–Bonferroni para comparar proporciones. La capacidad predictiva de los rasgos de la personalidad normales, patológicos y positivos sobre el impacto percibido se evaluó mediante regresiones múltiples jerárquicas, verificando los supuestos estadísticos básicos. Las respuestas abiertas se procesaron con técnicas de preprocesamiento y análisis de frecuencia léxica.

Se empleó el programa Jamovi, versión 2.2.5 solid, que trabaja a través del entorno R, para el cálculo de descriptivos, frecuencias, cálculo de correlaciones y análisis de regresiones.

Para el análisis automático de textos se utilizó el paquete Quanteda (versión 3.3.0) en el entorno R (versión 4.3.2) por medio de RStudio (versión 2024.04.2+764). El preprocesamiento incluyó la conversión a minúsculas, la eliminación de stopwords en español (diccionario de stopwords de Quanteda), la eliminación de signos de puntuación, números y caracteres especiales, así como la normalización léxica y la lematización. También se realizó stemming para agrupar variantes morfológicas de una misma palabra y se crearon tokens unigrama, excluyendo n-gramas de mayor orden. No se aplicó un umbral mínimo de frecuencia de tokens más allá del procesamiento de textos comentado. No se empleó validación intercodificador debido a que el análisis fue automatizado.

Resultados

Análisis de los comentarios negativos recibidos, según red utilizada, tipo de comentario y acción realizada

En primer lugar, se calculó la frecuencia de los comentarios negativos recibidos según la red social, el origen del comentario (cuentas identificables/no identificables), el tipo de comentario (por ejemplo, político, aspecto físico, sexuales) y la acción mayormente realizada con este.

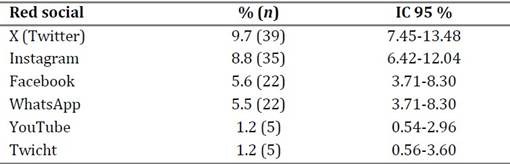

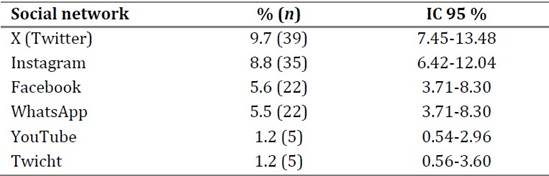

En la Tabla 1 se presenta la proporción de usuarios que reportaron haber recibido comentarios negativos en cada red social, en orden decreciente, junto con su correspondiente intervalo de confianza al 95 %. Se decidió informar únicamente los porcentajes e intervalos de confianza de este grupo, dado que constituye la población de interés para los análisis posteriores. En general, la frecuencia fue baja en todas las plataformas, con tasas más elevadas en X (Twitter) e Instagram, seguidas de Facebook y WhatsApp, y niveles cercanos al 1 % en YouTube y Twitch.

Tabla 1: Recepción de comentarios negativos según red social

La Tabla 2 muestra las comparaciones pareadas mediante la prueba z para diferencia de proporciones, aplicando la corrección de Holm–Bonferroni para comparaciones múltiples. Los resultados indican que X presentó porcentajes significativamente más altos que Facebook y WhatsApp, pero no difirió de Instagram. A su vez, Instagram registró valores superiores a YouTube y a Twitch, sin diferencias con Facebook o Whatsapp. Tanto Facebook como WhatsApp mostraron proporciones mayores que YouTube y Twitch, sin diferencias entre sí. YouTube y Twitch no difirieron significativamente.

Tabla 2: Pruebas z para la diferencia de proporciones de recepción de comentarios negativos entre redes sociales

Nota. Entre paréntesis significación exacta.

En cuanto a las fuentes de los comentarios recibidos, estas se distribuyeron de forma similar entre cuentas identificables (n = 368; 53.48 % (IC95 %: 49.68-57.24)) y no identificables (n = 321; 46.52 % (IC95 %: 42.76-50.32)), sin diferencias estadísticamente significativas (Prueba diferencia de proporciones: z = 1,15, gl = 1, p > .05).

Respecto del tipo de contenido, más de la mitad de los participantes que indicaron haber recibido comentarios negativos señalaron que estos estaban relacionados con información falsa y/o contenido político. Cabe aclarar que las categorías de contenido no son excluyentes, por lo que una misma persona pudo haber recibido más de un tipo de comentario. Asimismo, una parte importante de los participantes no recibió comentarios negativos. Respecto de la acción realizada frente a estos comentarios, de los 319 participantes que respondieron esta pregunta, el 53.3 % indicó que suele leerlos y no responderlos, mientras que el 33.2 % afirmó que los lee y a veces responde. El resto de los participantes refirió otras acciones con menor frecuencia.

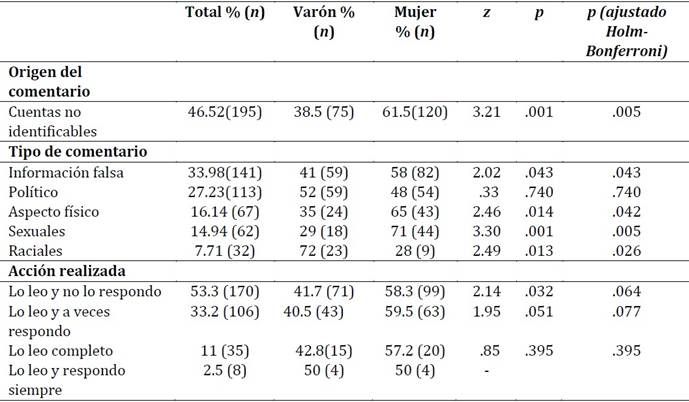

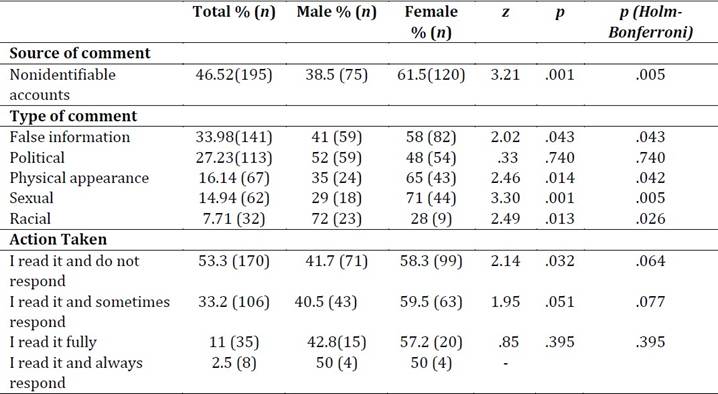

En la Tabla 3 pueden visualizarse las comparaciones según género. En comparación con los varones, la proporción de mujeres que reciben comentarios provenientes de cuentas no identificables es significativamente mayor. Además, las mujeres tienden a recibir con mayor frecuencia comentarios negativos relacionados con información falsa, y aspectos sexuales o físicos, mientras que los varones son más propensos a recibir comentarios negativos vinculados con aspectos raciales. En cuanto a las acciones desencadenadas por los comentarios negativos, se observa que las mujeres tienden a leerlos sin responder en mayor proporción que los varones. No se hallaron diferencias significativas entre géneros en los otros tipos de acción.

Tabla 3: Origen, tipo de comentario y acción realizada, según género

Análisis automático de textos de los comentarios negativos

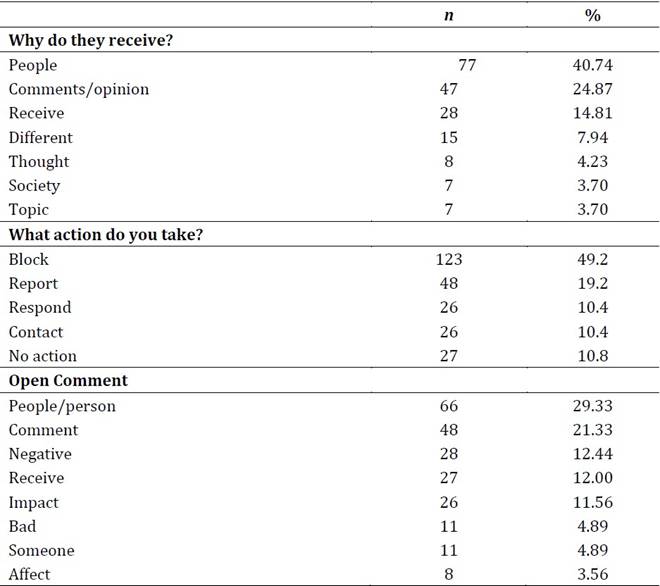

Se realizaron tres preguntas a los participantes con formato de respuesta libre con el propósito de indagar, en primer lugar, por qué les parecía que recibían comentarios negativos, en segundo lugar, qué acción realizaban una vez recibidos esos comentarios y, en tercer lugar, se les dio la opción de hacer un comentario libre sobre la temática. Los datos se presentan en la Tabla 4. Con los textos de los participantes se hizo un análisis de contenido. En primer lugar, se convirtieron las frases en tokens (palabras, unidades de significado), luego se realizó un preprocesamiento de los datos, que incluyó normalización léxica, eliminación de stopwords y agrupamiento semántico de términos similares. Si dos palabras tenían un significado similar (por ejemplo, ignorar, no responder), se agruparon en una misma categoría. Con los tokens resultantes se calcularon las frecuencias de las palabras. Se hizo el mismo procedimiento para las tres preguntas con formato de respuesta libre.

Cabe destacar que un mismo participante pudo haber aportado múltiples tokens dentro de una misma respuesta, por lo que los porcentajes que se presentan en la Tabla 4 corresponden a la frecuencia de aparición relativa de cada token o categoría léxica sobre el total de tokens identificados, y no al número de participantes. Las categorías fueron construidas agrupando tokens que comparten significados cercanos.

En cuanto al por qué las personas recibían este tipo de comentarios, el análisis de las palabras frecuentes nos permite inferir que es por tener opiniones, pensamientos diferentes sobre las personas, la sociedad o temas puntuales(por ejemplo, por discriminación, por intentar molestar al otro, por opiniones distintas, porque molesta lo que escribo). En segundo lugar, a la pregunta de qué acción realizaban frecuentemente cuando recibían comentarios negativos en las redes sociales, el 70 % consisten en bloquear y denunciar (por ejemplo, bloquear, denunciar, eliminar). El 20 % respondía y/o contactaba y el 10 % restante no realizaba ninguna acción. Finalmente, en los comentarios libres, si bien las palabras son menos interpretables que las anteriores, indican que los comentarios impactan, afectan o hacen mal a las personas (por ejemplo, me enojan, me dan bronca e impotencia, trato de no entrar en una pelea ridícula, me afectan cuando son agresivos o violentos).

Tabla 4: Análisis de contenido de las respuestas libres sobre comentarios negativos recibidos

Relación entre la intensidad de los

comentarios negativos,

las variables de uso de internet y el bienestar psicológico

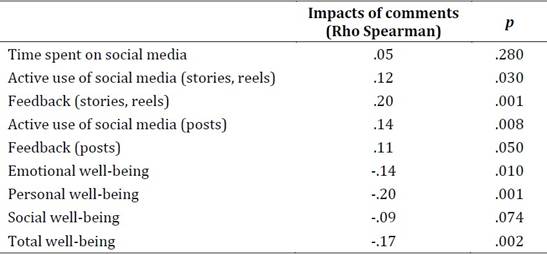

Se calcularon las correlaciones para analizar la relación entre el grado de impacto percibido respecto de los comentarios negativos, el tiempo y el tipo de uso de las redes sociales y el bienestar psicológico.

Como se observa en la Tabla 5, el grado de impacto percibido respecto de los comentarios negativos recibidos está vinculado con el uso activo de las redes sociales y no meramente con su uso en general, aunque la magnitud de estas asociaciones es modesta. En la medida en que se reciben más comentarios negativos respecto de la actividad en las redes vinculadas con transmisiones, historias y reels, mayor el grado de impacto percibido. El impacto de los comentarios tiende a disminuir en la medida en que aumenta el bienestar psicológico personal y en menor medida el emocional.

Tabla 5: Correlaciones entre el grado de impacto percibido respecto de los comentarios, las variables de uso de internet y el bienestar psicológico

Nota. En negrita, correlaciones significativas con tamaño del efecto pequeño.

Relación entre el impacto percibido

respecto de los comentarios negativos

y rasgos de personalidad (normal, patológico y positivos)

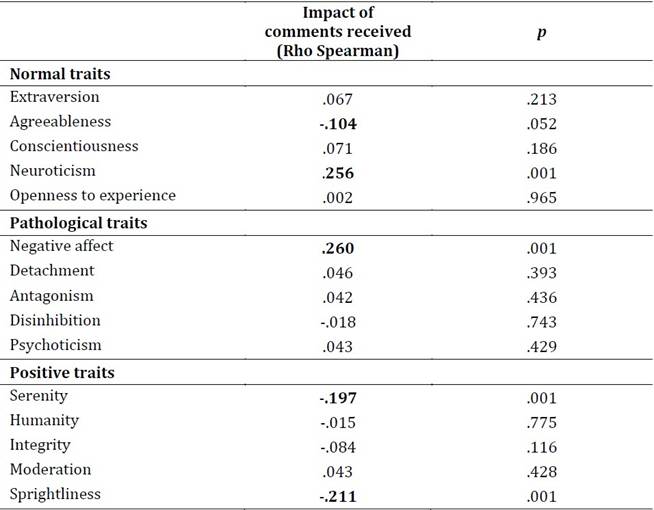

En primer lugar, se encontraron asociaciones positivas y significativas con los rasgos de la personalidad neuroticismo y afecto negativo. Asimismo, se encontraron asociaciones negativas significativas con los rasgos agradabilidad, serenidad y vivacidad (Tabla 6).

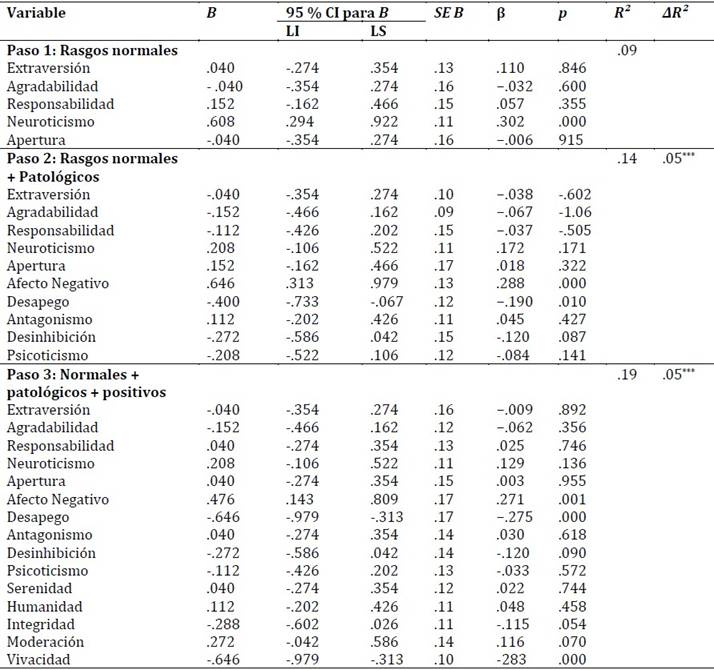

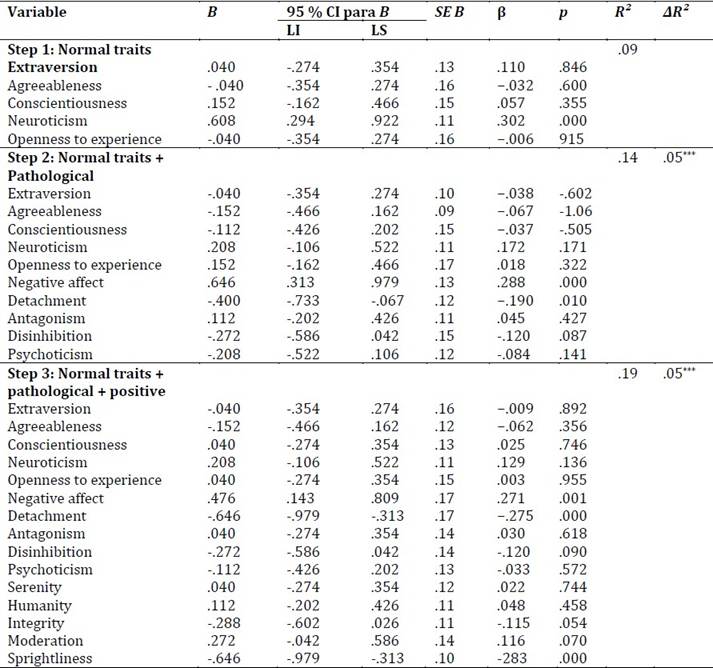

A continuación, se realizó un análisis de regresión múltiple jerárquica con el objetivo de verificar si las variables de la personalidad (normal, patológica y positiva) aportan varianza explicada respecto del impacto percibido de los comentarios negativos recibidos (Tabla 7). Las variables de la personalidad normal se incluyeron en el primer paso, en el segundo se adicionaron las variables referidas a rasgos patológicos y en el tercero las correspondientes a rasgos de personalidad positivos. No se incluyeron variables de control en los pasos anteriores.

Antes de la interpretación de los modelos, se evaluó el cumplimiento de los supuestos estadísticos. La inspección gráfica de los residuos estandarizados y las pruebas de normalidad indicaron una distribución aproximadamente normal, sin sesgos relevantes. Asimismo, el análisis de homocedasticidad mostró que la varianza de los residuos se mantuvo constante a lo largo de los valores predichos. En cada modelo se verificó la ausencia de multicolinealidad mediante el examen de los factores de inflación de la varianza (VIF), la tolerancia, los autovalores, el índice de condición y las proporciones de varianza. En ninguno de los modelos se observaron VIF superiores a 5, tolerancias inferiores a .10, ni índices de condición mayores a 30, acompañados de proporciones de varianza elevadas (> .50) en más de dos predictores, lo que indica una independencia estadística entre las variables.

En conjunto, las variables de la personalidad explican el 19 % de la varianza del impacto percibido de los comentarios negativos recibidos. La comparación de los modelos mostró que incluir variables patológicas y positivas en la explicación del impacto mejora la predicción realizada por los rasgos de la personalidad normal, que explican solamente un 9 %. Las variables de personalidad patológica y positiva adicionan en total 10 % (5 % cada una).

Tabla 6: Correlaciones entre grado de impacto

percibido de los comentarios

y variables de personalidad

Nota. En negrita, correlaciones significativas con tamaño del efecto pequeño.

Tabla 7: Regresión jerárquica múltiple para predecir el

impacto

de los comentarios negativos percibidos

Nota. IC: intervalo de confianza; LI: límite

inferior; LS: límite superior.

Los valores de β representan coeficientes estandarizados.

*p < .05. **p < .01. ***p < .001.

Discusión

Este estudio examinó la relación entre la recepción de comentarios negativos en las redes sociales, el bienestar psicológico y los rasgos de personalidad normales, patológicos y positivos.

En primer lugar, se exploró la frecuencia de los comentarios negativos recibidos según la red social utilizada, el origen (cuentas identificables/no identificables) y el tipo de comentario (por ejemplo, político, aspecto físico, sexuales) (objetivo 1). De acuerdo con los resultados obtenidos, la frecuencia de los comentarios negativos recibidos fue baja (menor al 10 %). Esta cifra resulta menor que las informadas por el Pew Research Center (2021) que da cuenta de que alrededor del 41 % de los usuarios reciben algún tipo de hostigamiento mediante medios digitales. Puede pensarse en diferencias culturales que podrían estar influyendo, por lo que sería interesante comparar muestras de países distantes culturalmente con el fin de identificar si algunos contextos favorecen este tipo de conductas online.

Un aspecto a destacar, como sostienen Zubair et al. (2023), es que el atravesamiento de la pandemia por covid-19 implicó que muchas personas que no usaban redes sociales pasaran a hacerlo, lo que aumentó el riesgo de sobreexposición y provocó que una mayor cantidad de usuarios queden expuestos a ser víctimas de trolling. Durante ese período, las redes sociales y otros medios digitales fueron fuente de desinformación y campañas maliciosas, razón por la que se comenzó a trabajar en sistemas que permitan detectar trolling (por ejemplo, TrollHunter; Jachim et al., 2020).

Los comentarios negativos recibidos por los usuarios de la muestra analizada eran en redes como X e Instagram y, en menor medida, Facebook y WhatsApp. Más de la mitad de los comentarios eran relativos a información falsa y comentarios políticos. Estos datos también son coincidentes con los relevados a nivel internacional (Fichman & Sanfilippo, 2016; Seigfried-Spellar & Chowdhury, 2017). Por un lado, X tiende a ser la red más usada para volcar agravios que tengan tinte político (Bishop, 2014; Komaç & Çağıltay, 2019) y, como se mencionó, suele usarse para divulgar información falsa (Jachim et al., 2020). Akhtar y Morrison (2019) comprobaron que cuando se analizan cuentas de políticos, el 100 % de los usuarios han sido víctimas de trolling alguna vez en esta red. En el caso de los usuarios comunes, recibir este tipo de comentarios negativos en general se vincula con respuestas a posteos que hayan realizado.

Otro aspecto importante a analizar respecto del fenómeno del trolling es que muchas veces es realizado desde cuentas falsas o bots (Jiang et al., 2016), principalmente en relación con cuestiones políticas, como ocurre, por ejemplo, en contextos electorales con las trolls farms (Denter & Ginzburg, 2021). Por esta razón, las últimas investigaciones han puesto el foco en el diseño de técnicas basadas en machine learning para detectar cuentas trolls y diferenciar entre cuentas falsas y verdaderas (Machova et al., 2021). En el presente estudio, se halló que la mitad de los comentarios negativos provenían de cuentas no identificables, lo que sugiere que puede que se traten de cuentas falsas, sobre todo si se relacionan con temas políticos.

En la muestra analizada se observó que las mujeres reciben la mayor cantidad de comentarios de fuentes no identificables. Además, en cuanto al tipo de contenido, suelen recibir comentarios referidos a información falsa y a aspectos sexuales o físicos. En cambio, los hombres son más propensos a recibir comentarios negativos vinculados con aspectos raciales. Estos datos coinciden con antecedentes a nivel internacional (Akhtar & Morrison, 2019) y local (Defensoría del Pueblo de la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, 2024).

También se indagaron los motivos por los que los participantes perciben que reciben comentarios negativos, qué acción personal realizan y qué opinión tienen sobre estos (objetivo 2). El análisis sobre las respuestas abiertas de los participantes de la muestra analizada dio cuenta de que las personas creen que reciben comentarios ofensivos por tener opiniones y pensamientos diferentes sobre la sociedad o temas de actualidad, como por ejemplo, políticos. Esta percepción de los participantes coincide con lo que revelan las investigaciones internacionales respecto de los motivos frecuentes asociados con las conductas de trolling y otros comportamientos antisociales online (Jatmiko, 2024; Seigfried-Spellar & Chowdhury, 2017).

En cuanto al tipo de acción que los usuarios hacen frente a los comentarios negativos, las mujeres tienden a leerlos y no responder, a diferencia de los varones que sí lo hacen. Como ha sido descrito, la conducta troll se caracteriza por ser provocadora, no tiene una finalidad objetiva más que generar disrupción en la comunicación (Hardaker, 2010), hecho que se ve favorecido por el anonimato (Nitschinsk et al., 2023; Suler, 2004). Por lo tanto, tal como sostienen Paakki et al. (2021), si los usuarios que se sienten agraviados responden, lo más probable es que entren en un juego que no lleve a ningún consenso. En la muestra analizada solo el 20 % admitió que respondía a los comentarios negativos recibidos.

El tercer objetivo de esta investigación consistía en examinar la relación entre la intensidad de los comentarios negativos recibidos y el bienestar psicológico percibido. Este aspecto resulta novedoso, ya que los estudios previos han analizado, principalmente, los efectos que provocan ser víctima de hostigamiento online cuando existe un conocimiento previo entre víctima y victimario, lo que no sucede en el caso del trolling (Fichman & Sanfilippo, 2016). En la muestra analizada se encontró que hay una relación inversa entre los niveles de bienestar y la intensidad de los comentarios recibidos. Además, en las respuestas abiertas se pudo deducir que los participantes tienden a creer que recibir estos comentarios les hace mal o les afecta negativamente. Asimismo, se observó que el grado de impacto percibido es mayor cuando los usuarios hacen un uso activo de las redes y pasan bastante tiempo posteando, subiendo historias o reels. Recibir comentarios negativos cuando hay un interés en subir contenidos, se vincula a menores niveles de bienestar percibido. Si bien estos resultados contradicen, en parte, las investigaciones previas, que mostraban que en general el impacto psicológico negativo es mayor en aquellos usuarios que hacen un uso pasivo de las redes (Verduyn et al., 2015), coinciden con otros estudios que dan cuenta de que un uso excesivo se asocia con bajos niveles de bienestar (por ejemplo, Blease, 2015; Lupano Perugini & Castro Solano, 2019; Shaw et al., 2015; Zubair et al., 2023).

Tal como se mencionó, los estudios de los efectos sobre el bienestar que genera internet y el uso de las redes suelen ser contradictorios (por ejemplo, Frison & Eggermont, 2015; Kraut et al., 2002; Lup et al., 2015; Nie et al., 2015). Esto lleva a pensar que otras variables pueden estar relacionadas. Por tal motivo, como parte del último objetivo de este estudio se analizó la relación de variables de personalidad (rasgos normales, patológicos y positivos) sobre el grado de impacto percibido respecto de los comentarios negativos recibidos. Este aspecto también resulta novedoso, ya que la mayor parte de los estudios previos han analizado las características de personalidad de los usuarios que ejercen trolling y no de quienes son víctimas (por ejemplo, Buckels et al., 2014; March et al., 2023; Lupano Perugini & Castro Solano, 2021, 2023).

A partir de los datos analizados, se halló que el grado de impacto percibido respecto de los comentarios negativos recibidos se asocia positivamente con el rasgo normal neuroticismo y el rasgo patológico afecto negativo. Asimismo, se asocia negativamente con el rasgo normal agradabilidad y los rasgos positivos serenidad y vivacidad. De esto se puede concluir que aquellas personas que se sienten más afectadas por recibir comentarios negativos son usuarios que tienen una tendencia a experimentar emociones negativas (por ejemplo, ansiedad, preocupación) y una baja capacidad de manejar estas emociones. Además, se perciben con dificultades para interrelacionar con otros y tener metas y objetivos claros. Por último, a partir del análisis de regresión efectuado, se destaca la necesidad de analizar rasgos patológicos y positivos, y no solo normales, ya que agregan varianza a la explicación del impacto de los comentarios negativos recibidos.

Limitaciones, futuras líneas de

investigación e implicancias prácticas

de los hallazgos

En primer lugar, la limitación de este estudio recae en que se analizaron de forma general las conductas de trolling a partir de indagar sobre comentarios que los usuarios perciben como negativos. No se hizo una diferenciación entre tipos de conducta troll, ya sea que apunten más a la simple obtención de diversión por quien las propina o que, en cambio, tengan una connotación más agresiva. Futuros estudios podrán focalizar en los diferentes tipos de conductas troll, sus características y consecuencias.

Otra limitación se relaciona con la representatividad de la muestra utilizada, no solo en cuanto al n sino en relación con que es una muestra de sujetos residentes más que nada en los centros urbanos de Buenos Aires, siendo baja la participación de otros sectores del país. También se trata de una muestra altamente formada en términos académicos, lo que puede influir en la forma que interpretan el recibir comentarios negativos en las redes sociales.

En cuanto a los instrumentos de recolección de datos, en su mayor parte se trató de inventarios autodescriptivos que pueden ocasionar que las personas tiendan a orientar sus respuestas de acuerdo con lo que es deseable socialmente y evitar exponer que han sido víctimas de ataques o burlas por medio de las redes.

Los aspectos mencionados pueden afectar la generalización de los resultados, por lo que sería deseable replicar los análisis con muestras diversas y más amplias.

Como futuras líneas de investigación, sería interesante realizar estudios comparativos a nivel internacional, ya que, hasta el momento, se han analizado variables individuales o que hacen a las características de los entornos virtuales, pero no se ha profundizado si el trolling tiene la misma prevalencia e impacto en distintos contextos socioculturales. Por otro lado, puede resultar atinado analizar la frecuencia y el impacto diferenciando tipo de red social (por ejemplo, X, Instagram, TikTok, etc.), tipo de usuario (por ejemplo, político, artista, influencer, usuario común, etc.) o tipo de contenido sobre el que se pronuncian los comentarios agresivos (por ejemplo, posteo político, artístico, social, etc.).

Además, en futuros estudios sería interesante analizar la relación entre los rasgos de personalidad y los aspectos analizados en los primeros objetivos. De esta manera, podría estudiarse si los usuarios con ciertas características de personalidad tienden a percibir que son víctimas de trolling en mayor medida que otros perfiles y de qué forma tienden a responder y reaccionar a estos ataques. Vinculado con esto, también resulta relevante analizar el papel que pueden jugar las variables mediadoras o moderadoras en la relación entre los factores de personalidad y los efectos sobre el bienestar que genera tanto ser víctima de conductas de trolling como ejercer esas conductas. Por ejemplo, variables como el tiempo de exposición (Alavi et al., 2025) o el nivel de autoestima pueden jugar un papel importante en esta relación (Zhou et al., 2023).

Los diferentes hallazgos permiten pensar en insumos que pueden ser tenidos en cuenta para delinear algunas implicancias prácticas destinadas a diferentes niveles y agentes intervinientes. Desde el plano individual, parece importante trabajar en el fortalecimiento de los factores que pueden ser protectores de este tipo de conductas disruptivas online, como la autorregulación, la moderación y la claridad en los objetivos y las metas. Para ello, es importante el desarrollo de campañas informativas, ya sea en entornos educativos como comunitarios, que informen tanto de los beneficios como de los perjuicios a los que los usuarios de internet y redes sociales están expuestos y, de esta manera, saber cómo actuar si se es víctima de trolling y otro tipo de conducta antisocial online (por ejemplo, no responder, bloquear, etc.).

De esta manera, se intenta fomentar lo que algunos autores denominan bienestar digital, entendido como un estado en el que se preserva el bienestar subjetivo en un entorno marcado por una abundante comunicación digital (Vanden Abeele & Nguyen, 2022). Se intenta lograr que las personas sean capaces de utilizar los medios digitales de manera que se fomente una sensación de comodidad, seguridad, satisfacción y realización personal. Por último, desde el plano tecnológico y de políticas públicas, resulta importante seguir trabajando en el refinamiento de las herramientas que permitan detectar cuentas troll a fin de tomar las medidas que correspondan de acuerdo con los perjuicios que puedan generar en los usuarios. En síntesis, es necesario trabajar en el desarrollo de entornos virtuales saludables que sirvan a que las personas puedan acceder a contenidos e interactuar de manera positiva con otros, lo que fue la finalidad inicial del desarrollo de internet.

Referencias:

Alavi, M., Garg, A., & Wanigatunga, N. (2025). The relationships between Dark Tetrad traits and adolescent cyberbullying and cybertrolling with online time and life satisfaction as moderators. Discover Psychology, 5(1), 29. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44202-025-00351-6

Akhtar, S., & Morrison C. M. (2019). The prevalence and impact of online trolling of UK members of parliament. Computers in Human Behavior, 99, 322-327. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2019.05.015

Bentley, L. A., & Cowan, D. G. (2021). The socially dominant troll: Acceptance attitudes towards trolling. Personality and Individual Differences, 173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110628

Bishop, J. (2014). Representations of ‘trolls’ in mass media communication: A review of media-texts and moral panics relating to internet trolling. International Journal of Web Based Communities, 10(10), 7-24. https://doi.org/10.1504/ijwbc.2014.058384

Blease, C. R. (2015). Too many ‘Friends,’ Too few ‘Likes’? Evolutionary psychology and ‘Facebook Depression’. Review of General Psychology, 19(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1037/gpr0000030

Bleidorn, W., & Hopwood, C. J. (2019). Using machine learning to advance personality assessment and theory. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 23(2), 190-203. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868318772990

Buckels, E. E., Trapnell, P. D., Andjelovic, T., & Paulhus, D. L. (2018). Internet trolling and everyday sadism: Parallel effects on pain perception and moral judgment. Journal of Personality, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12393

Buckels, E. E., Trapnell, P., & Paulhus, D. L. (2014). Trolls just want to have fun. Personality and Individual Differences, 67, 97-102. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.01.016

Brubaker, P. J., Montez, D., & Church, S. H. (2021). The power of schadenfreude: Predicting behaviors and perceptions of trolling among Reddit users. Social Media + Society, 7(2), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F20563051211021382

Castro Solano, A., & Casullo, M. M. (2001). Rasgos de personalidad, bienestar psicológico y rendimiento académico en adolescentes argentinos. Interdisciplinaria, 18, 65-85.

Coles, B. A., & West, M. (2016). Trolling the trolls: Online forum users constructions of the nature and properties of trolling. Computers in Human Behavior, 60, 233-244. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.02.070

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1985). The NEO Personality Inventory Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources. https://doi.org/10.1037/t07564-000

Craker, N., & March, E. (2016). The dark side of Facebook®: The Dark Tetrad, negative social potency, and trolling behaviours. Personality and Individual Differences, 102, 79-84. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.06.043

Defensoría del Pueblo de la Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires. (2024). Estudio exploratorio sobre la violencia digital con perspectiva de género. Instituto de Investigaciones Gino Germani, Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, UBA; Iniciativa Spotlight; ONU Mujeres; UNFPA. https://argentina.unfpa.org/sites/default/files/pub-pdf/2024-12/Informe%20-%20versi%C3%B3n%20final.pdf

De la Iglesia, G., & Castro Solano, A. (2018). The Positive Personality Model (PPM): Exploring a new conceptual framework for personality assessment. Frontiers in Psychology, 9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02027

De la Iglesia, G., & Castro Solano, A. (2023). Análisis psicométricos del Inventario de Continuos de la Personalidad, Forma Corta (ICCP-SF). Interdisciplinaria, 40(1), 99-114. https://doi.org/10.16888/interd.2023.40.1.6

Denter, P., & Ginzburg, B. (2021). Troll Farms and Voter Disinformation. SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.3919032

Ellison, N. B., Steinfield, C., & Lampe, C. (2007). The benefits of Facebook “friends:” Social capital and college students’ use of online social network sites. Journal of computer‐mediated communication, 12(4), 1143-1168. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2007.00367.x

Fichman, P., & Sanfilippo, M. R. (2016). Online trolling and its perpetrators: Under the cyberbridge. Rowman & Littlefield.

Flores-Saviaga, C., Keegan, B., & Savage, S. (2018). Mobilizing the Trump train: Understanding collective action in a political trolling community. En Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media. https://doi.org/10.1609/icwsm.v12i1.15024

Frison, E., & Eggermont, S. (2015). Exploring the relationships between different types of Facebook use, perceived online social support, and adolescents’ depressed mood. Social Science Computer Review, 34, 153-171. https://doi.org/10.1177/0894439314567449

Golf-Papez, M., & Veer, E. (2017). Don’t feed the trolling: rethinking how online trolling is being defined and combated. Journal of Marketing Management, 33(15–16), 1336-1354. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267257X.2017.1383298

Hardaker, C. (2010). Trolling in asynchronous computer mediated communication: From user discussions to academic definitions. Journal of Politeness Research, 6(2), 215-242. https://doi.org/10.1515/JPLR.2010.011

Hoffmann, J., & Sheridan, L. (2008a). Stalking, threatening, and attacking corporate figures. En M. Reid, L. Sheridan, & J. Hoffmann (Eds.), Stalking, Threatening, and Attacking Public Figures: A Psychological and Behavioral Analysis (pp. 123-142). Oxford Academic.

Hoffmann, J., & Sheridan, L. (2008b). Celebrities as victims of stalking. En M. Reid, L. Sheridan, & J. Hoffmann (Eds.), Stalking, Threatening, and Attacking Public Figures: A Psychological and Behavioral Analysis (pp. 195-213). Oxford Academic.

Iliev, R., Dehghani, M., & Sagi, E. (2015). Automated text analysis in psychology: Methods, applications, and future developments. Language and Cognition, 7(2), 265-290. https://doi.org/10.1017/langcog.2014.30

Jachim, P., Sharevski, F., & Treebridge, P. (2020). TrollHunter (Evader): Automated Detection (Evasion) of Twitter Trolls During the COVID-19 Pandemic. New Security Paradigms Workshop, 2020, 59-75. https://doi.org/10.1145/3442167.3442169

James, D. V., Farnham, F. R., Sukhwal, S., Jones, K., Carlisle, J., & Henley, S. (2016). Aggressive/intrusive behaviours, harassment and stalking of members of the United Kingdom parliament: A prevalence study and cross-national comparison. Journal of Forensic Psychiatry and Psychology, 27(2), 177-197. https://doi.org/10.1080/14789949.2015.1124908

Jatmiko, M. I. (2024). Book review: Trolling Ourselves to Death: Democracy in the Age of Social Media, by Jason Hannan. Television & New Media, 25(7), 753-756. https://doi.org/10.1177/15274764241261069

Jiang, M., Cui, P., & Faloutsos, C. (2016). Suspicious Behavior Detection: Current Trends and Future Directions. IEEE Intelligent Systems, 31(1), 31-39. https://doi.org/10.1109/mis.2016.5

John, O. P., Donahue, E. M., & Kentle, R. L. (1991). The Big Five Inventory–Versions 4a and 54. University of California, Berkeley, Institute of Personality and Social Research. https://doi.org/10.1037/t07550-000

Keyes, C. L. M. (2005). The subjective well-being of America’s youth: toward a comprehensive assessment. Adolescent & Family Health, 4(1), 3-11.

Komaç, G., & Çağıltay, K. (2019). An overview of trolling behavior in online spaces and gaming context. En 2019 1st International Informatics and Software Engineering Conference (UBMYK). https://10.1109/UBMYK48245.2019.8965625

Kowalski, R. M., Toth, A., & Morgan, M. (2017). Bullying and cyberbullying in adulthood and the workplace. The Journal of Social Psychology, 158(1), 64-81. https://doi.org/10.1080/00224545.2017.1302402

Kraut, R., Kiesler, S., Boneva, B., Cummings, J., Helgeson, V., & Crawford, A. (2002). Internet paradox revisited. Journal of Social Issues, 58, 49-74. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4560.00248

Kraut, R., Patterson, M., Lundmark, V., Kiesler, S., Mukopadhyay, T., & Scherlis, W. (1998). Internet paradox: A social technology that reduces social involvement and psychological well-being? American Psychologist, 53, 1017-1031. https://doi.org/10.1037//0003-066x.53.9.1017

Laboy-Vélez, L., Ríos-Steiner, A. I., & Flores- Suárez, W. (2021). La violencia digital como amenaza a un ambiente laboral seguro. Fórum Empresarial, 26(1), 99-112. https://doi.org/10.33801/fe.v26i1.19494

Lamba, M., & Madhusudhan, M. (2019). Mapping of topics in DESIDOC Journal of Library and Information Technology, India: a study. Scientometrics, 120(2), 477-505. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11192-019-03137-5

Lup, K., Trub, L., & Rosenthal, L. (2015). Instagram #Instasad?: Exploring associations among Instagram use, depressive symptoms, negative social comparison, and strangers followed. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 18, 247-252. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2014.0560

Lupano Perugini, M. L., & Castro Solano, A. (2019). Características psicológicas diferenciales entre usuarios de redes sociales de alta exposición vs. no usuarios. Acta Psiquiátrica y Psicológica de América Latina, 65(1), 5-16.

Lupano Perugini, M. L., & Castro Solano, A. (2021). Rasgos de personalidad, bienestar y malestar psicológico en usuarios de redes sociales que presentan conductas disruptivas online. Interdisciplinaria, 38(2), 7-23. https://doi.org/10.16888/interd.2021.38.2.1

Lupano Perugini, M. L., de la Iglesia, G., Castro Solano, A., & Keyes, C. L. M. (2017). The Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF) in the Argentinean context: confirmatory factor analysis and measurement invariance. Europe´s. Journal of Psychology, 13, 93-108. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v13i1.1163

Machova, K., Mach, M., & Vasilko, M. (2022). Comparison of machine learning and sentiment analysis in detection of suspicious online reviewers on different type of Data. Sensors, 22. https://doi.org/10.3390/s22010155

March, E., & Marrington, J. (2019). A qualitative analysis of internet trolling. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 22(3), 192-197. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2018.0210

March, E., McDonald, L. & Forsyth, L. (2023). Personality and internet trolling: a validation study of a representative sample. Current Psychology, 43(6), 4815-4818. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-023-04586-1

Mathew, B., Dutt, R., Goyal, P., & Mukherjee, A. (2019). Spread of hate speech in online social media. En Proceedings of the 10th ACM conference on web science (pp. 173-182).

Montez, D., & Kim, D. H. (2025). How do silent trolls become overt trolls? Fear of punishment and online disinhibition moderate the trolling path. Social Media + Society, 11(1), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1177/20563051251320437

Nie, P., Sousa-Poza, A., & Nimrod, G. (2015). Internet use and subjective well-being in China. Social Indicators Research, 132, 489-516. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-015-1227- 8

Nitschinsk, L., Tobin, S. J., & Vanman, E. J. (2023). A functionalist approach to online trolling. Frontiers in Psychology, 14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2023.1211023

Ortiz, S. M. (2020). Trolling as a collective form of harassment: An inductive study of how online users understand trolling. Social Media + Society, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1177/2056305120928512

Paakki, H., Vepsäläinen, H., & Salovaara, A. (2021). Disruptive online communication: How asymmetric trolling-like response strategies steer conversation off the track. Computer Supported Cooperative Work, 30(3), 425-461. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10606-021-09397-1

Pacheco, J. (2022). Variables asociadas al fenómeno del ciberbullying en adolescentes colombianos. Revista de Psicología, 41(1), 219-239. https://doi.org/10.18800/psico.202301.009

Park, G., Schwartz, H. A., Eichstaedt, J. C., Kern, M. L., Kosinski, M., Stillwell, D. J., & Seligman, M. E. (2015). Automatic personality assessment through social media language. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(6), 934. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000020

Pew Research Center (2021). Online Harassment. https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2021/01/13/the-state-of-online-harassment/pi_2021-01-13_online-harrasment_0-01-1-png/

Phillips, W. (2015). This is why we can’t have nice things: Mapping the relationship between online trolling and mainstream culture. MIT Press.

Sands, S., Campbell, C., Ferraro, C., & Mavrommatis, A. (2020). Seeing light in the dark: Investigating the dark side of social media and user response strategies. European Management Journal, 38(1), 45-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.emj.2019.10.001

Sanfilippo, M. R., Fichman, P., & Yang, S. (2018). Multidimensionality of online trolling behaviors. The Information Society, 34(1), 27-39. https://doi.org/10.1080/01972243.2017.1391911

Scriven, P. (2025). Online trolling as a dark leisure activity. Annals of Leisure Research, 28(2), 283-301. https://doi.org/10.1080/11745398.2024.2358764

Seigfried-Spellar, K. C., & Chowdhury, S. S. (2017). Death and Lulz: Understanding the personality characteristics of RIP trolls. First Monday, 22(11). https://doi.org/10.5210/fm.v22i11.7861

Sest, N., & March, E. (2017). Constructing the cyber-troll: Psychopathy, sadism, and empathy. Personality and Individual Differences, 119, 69-72. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.06.038

Shaw, A. M., Timpano, K. R., Tran, T. B., & Joormann, J. (2015). Correlates of Facebook usage patterns: the relationship between passive Facebook use, social anxiety symptoms, and brooding. Computers in Human Behavior, 48, 575-580. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.02.003

Shekhar, S., Garg, H., Agrawal, R., Shivani, R., & Sharma, B. (2021). Hatred and trolling detection transliteration framework using hierarchical LSTM in code-mixed social media text. Complex & Intelligent Systems, 9, 2813-2826. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40747-021-00487-7

Stover, J. B., Fernández Liporace, M. M., & Castro Solano, A. (2023). Escala de Uso Problemático Generalizado del Internet 2: Adaptación para adultos de Buenos Aires. Revista de Psicología, 41(2), 1127-1151. https://doi.org/10.18800/psico.202302.017

Suler, J. (2004). The online disinhibition effect. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 7(3), 321-326. https://doi.org/10.1089/1094931041291295

Sun, L. H., & Fichman, P. (2019). The collective trolling lifecycle. Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology, 71(7), 770-783. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24296

Tristão, L. A., Iossi Silva, M. A., De Oliveira, W. A., Dos Santos, D., & Da Silva, J. L. (2022). Bullying y cyberbullying: intervenciones realizadas en el contexto escolar. Revista de Psicología, 40(2), 1047-1073. https://doi.org/10.18800/psico.202202.015

Truong, D.-H., & Chen, J. V. (2024). Understanding the we-intention to participate in collective trolling on social networking sites: The online disinhibition perspective. PACIS 2024 Proceedings, 17.

Ubaradka, A., & Khanganba, S. P. (2024). The differential effect of psychopathy on active and bystander trolling behaviors: The role of dark tetrad traits and lower agreeableness. Scientific Reports, 14(1), 9905. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-024-60203-6

Vanden Abeele, M. M. P., & Nguyen, M. H. (2022). Digital well-being in an age of mobile connectivity: An introduction to the Special Issue. Mobile Media & Communication, 10(2), 174-189. https://doi.org/10.1177/20501579221080899

Verduyn, P., Lee, D. S., Park, J., Shablack, H., Orvell, A., Bayer, J., & Kross, E. (2015). Passive Facebook usage undermines affective wellbeing: Experimental and longitudinal evidence. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 144, 480-488. https://doi.org/10.1037/xge0000057

Yarkoni, T., & Westfall, J. (2017). Choosing prediction over explanation in psychology: Lessons from machine learning. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(6), 1100-1122. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617693393

Zhou, Y., Li, F., Wang, Q., & Gao, J. (2023). Sense of power and online trolling among college students: Mediating effects of self-esteem and moral disengagement. Journal of Psychology in Africa, 33(4), 378-383. https://doi.org/10.1080/14330237.2023.2219527

Zubair, U., Khan, M. K., & Albashari, M. (2023). Link between excessive social media use and psychiatric disorders. Annals of Medicine and Surgery, 85(4), 875-878. https://doi.org/10.1097/MS9.0000000000000112

Financiamiento: Proyecto UBACyT 20020190100045BA: “Perfil psicológico de los usuarios de internet y redes sociales. Análisis de rasgos de personalidad positivos y negativos desde un enfoque psicoléxico y variables psicológicas mediadoras”, de la Universidad de Buenos Aires.

Conflicto de interés: Los autores declaran que no tienen conflictos de intereses.

Disponibilidad de datos: El conjunto de datos que apoya los resultados de este estudio se encuentra disponible en https://osf.io/wxp47/?view_only=daed2672d9174f2685905fb3819bfec3

Cómo citar: Castro Solano, A., & Lupano Perugini, M. L. (2025). Trolling en redes sociales. Bienestar psicológico y personalidad normal, patológica y positiva. Ciencias Psicológicas, 19(2), e-4543. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v19i2.4543

Contribución de los autores (Taxonomía CRediT): 1. Conceptualización; 2. Curación de datos; 3. Análisis formal; 4. Adquisición de fondos; 5. Investigación; 6. Metodología; 7. Administración de proyecto; 8. Recursos; 9. Software; 10. Supervisión; 11. Validación; 12. Visualización; 13. Redacción: borrador original; 14. Redacción: revisión y edición.

A. C. S. ha contribuido en 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13; M. L. L. P. en 1, 5, 6, 12, 13, 14.

Editora científica responsable: Dra. Cecilia Cracco.

Ciencias Psicológicas; v19(2)

Julho-dezembro 2025

10.22235/cp.v19i2.4543

Original Articles

Trolling on Social Media. Psychological Well-being

and Normal, Pathological, and Positive Personality

Trolling en redes sociales. Bienestar psicológico y personalidad normal, patológica y positiva

Trolling nas redes sociais. Bem-estar psicológico e personalidade normal, patológica e positiva

Alejandro Castro Solano1, ORCID 0000-0002-4639-3706

María Laura Lupano Perugini2, ORCID 0000-0001-6090-0762

1 Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas; Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina, [email protected]

2 Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas; Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina

Abstract:

Objective. This study examined the relationships among the reception of negative comments on social media; psychological well-being; and normal, pathological, and positive personality traits. Method. A total of 799 social media users residing in Argentina participated (338 men, 461 women; M = 39.7 years, SD = 13.84). The following instruments were used: the Big Five Inventory, the Mental Health Continuum–Short Form, the Inventory of the Five Personality Continuums–Short Version, and an ad hoc survey on the reception of negative comments on social media. The design was cross-sectional, nonexperimental, and correlational. The results. The frequency of negative comments was less than 10 % across all analyzed social media platforms. The degree of self-perceived distress was significantly associated with active use of social media (r = .24, p < .001) and with lower levels of psychological well-being (r = -.30, p < .001). Normal personality traits explained 9 % of the variance in the level of distress; when pathological and positive traits were added, they accounted for an additional 10 % of the total. Conclusions. Distress associated with the reception of negative comments on social media is linked to lower well-being and to a personality profile characterized by neuroticism and negative affect. The inclusion of pathological and positive traits improves the explanation of distress beyond normal traits.

Keywords: trolling; positive personality traits; pathological personality traits; normal personality traits; psychological well-being.

Resumen:

Objetivo. Este estudio examinó la relación entre la recepción de comentarios negativos en redes sociales, el bienestar psicológico y los rasgos de personalidad normales, patológicos y positivos. Método. Participaron 799 usuarios de redes sociales residentes en Argentina (338 varones, 461 mujeres; M = 39.7 años, DE = 13.84). Se emplearon los instrumentos: Big Five Inventory, Mental Health Continuum-Short Form, Inventario de los Cinco Continuos de la Personalidad - versión breve y una encuesta ad hoc sobre recepción de comentarios negativos en redes sociales. El diseño fue transversal, no experimental y correlacional. Resultados. La frecuencia de comentarios negativos fue inferior al 10 % en todas las redes sociales analizadas. El grado de malestar autopercibido se asoció significativamente con el uso activo de redes sociales (r = .24, p < .001) y con niveles más bajos de bienestar psicológico (r = -.30, p < .001). Los rasgos de personalidad normal explicaron el 9 % de la varianza del grado de malestar y, al incorporar los rasgos patológicos y positivos, adicionaron en total 10 %. Conclusiones. El malestar debido a la recepción de comentarios negativos en redes sociales está asociado con un menor bienestar y con un perfil de personalidad vinculado con el neuroticismo y el afecto negativo. La inclusión de rasgos patológicos y positivos mejora la explicación del malestar más allá de los rasgos normales.

Palabras clave: trolling; rasgos positivos; rasgos patológicos; rasgos normales; bienestar psicológico.

Resumo:

Objetivo. Este estudo examinou a relação entre a recepção de comentários negativos nas redes sociais, o bem-estar psicológico e os traços de personalidade normais, patológicos e positivos. Método. Participaram 799 usuários de redes sociais residentes na Argentina (338 homens, 461 mulheres; M = 39,7 anos, DP = 13,84). Foram utilizados os instrumentos: Big Five Inventory, Mental Health Continuum-Short Form, Inventário dos Cinco Contínuos da Personalidade- versão breve, e um questionário ad hoc sobre a recepção de comentários negativos em redes sociais. O delineamento foi transversal, não experimental e correlacional. Resultados. A frequência de comentários negativos foi inferior a 10 % em todas as redes sociais analisadas. O grau de mal-estar autopercebido associou-se significativamente ao uso ativo de redes sociais (r = 0,24, p < 0,001) e a níveis mais baixos de bem-estar psicológico (r = -0,30, p < 0,001). Os traços de personalidade normal explicaram 9 % da variância do grau de mal-estar; ao incorporar os traços patológicos e positivos, adicionaram no total 10 %. Conclusões. O mal-estar vinculado à recepção de comentários negativos nas redes sociais está associado a menor bem-estar e a um perfil de personalidade marcado pelo neuroticismo e pelo afeto negativo. A inclusão de traços patológicos e positivos melhora a explicação do mal-estar para além dos traços normais.

Palavras-chave: trolling; traços positivos; traços patológicos; traços normais; bem-estar psicológico.

Received: 03/26/2025

Accepted: 09/12/2025

For several years, communication through social media has established itself as a dominant mode. Despite the advantages it may entail, research shows that the use of social media has a darker side (Sands et al., 2020). In this study, we refer to the phenomenon known as trolling, which can be understood not only as disruptive behavior but also as a form of dark leisure, insofar as it involves recreational activity that, although transgressive, is carried out for pleasure and entertainment (Scriven, 2025).

There is no precise definition of the term trolling, and discrepancies can be observed when attempting to define it, sometimes even differing from the general understanding people have of what it means (Ortiz, 2020). Nevertheless, most authors consider it a global term encompassing a spectrum of behaviors and multicausal motivations that are antagonistic, antisocial, or deviant in the context of online behavior (Buckels et al., 2014; Buckels et al., 2018; Hardaker, 2010; Phillips, 2015; Sanfilippo et al., 2018). These behaviors are amplified by the anonymity under which such interventions can occur (Nitschinsk et al., 2023; Suler, 2004). In general, trolls often lack a well-defined intention; their primary goal is merely to annoy and generate interference in communication (Hardaker, 2010). Therefore, if users respond to comments and posts made by trolls, it is highly likely that they will enter into a spiral of unconstructive exchanges (Paakki et al., 2021).

According to some researchers, these kinds of disruptive online behaviors represent only one form of trolling, known as kudos trolling. However, trolling has evolved from provoking others for mutual enjoyment and entertainment to a more abusive, aggressive, and reactive form of behavior that is not intended to be humorous, called flame trolling (Bishop, 2014; Komaç & Çağıltay, 2019; March & Marrington, 2019). There are also other types of users known as silent trolls, who do not engage directly in trolling behavior but instead act as spectators of such online conduct. Similarly, so-called supportive trolls not only observe but also “like” trolling behaviors carried out by others, indirectly encouraging the proliferation of these behaviors (Brubaker et al., 2021; Montez & Kim, 2025; Ubaradka & Khanganba, 2024).

In the political arena, troll farms are well known; these entities function to manipulate voters through posts or comments on social media (Denter & Ginzburg, 2021). Recent research has included the analysis of collective trolling behaviors, driven by anonymity, where the mass repetition of disruptive behaviors (e.g., comments, posts) directed at an individual or group increases the intensity of the harm inflicted (Flores-Saviaga et al., 2018; Sun & Fichman, 2019; Truong & Chen, 2024).

The type of trolling behavior may also vary depending on the social network or community to which the perpetrating user belongs (Fichman & Sanfilippo, 2016). In general, trolling is more frequent in posts or publications that involve politics or current events (Jatmiko, 2024; Seigfried-Spellar & Chowdhury, 2017). Thus, the context of an online discussion often promotes trolling behavior, regardless of users’ personal characteristics (Bentley & Cowan, 2021).