Ciencias Psicológicas; v19(2)

julio-diciembre 2025

10.22235/cp.v19i2.4530

Modelo predictivo del crecimiento postraumático

en padres de pacientes con cardiopatías congénitas

Predictive Model of Posttraumatic Growth in Parents of Pediatric Patients

with Congenital Heart Disease

Modelo preditivo do crescimento pós-traumático em pais de pacientes

com cardiopatias congênitas

Alma Leticia de la Garza Samaniego1 ORCID 0009-0001-1400-1173

Lucía Quezada Berumen2 ORCID 0000-0003-4705-3225

1 Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, México

2 Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, México, [email protected]

Resumen:

El diagnóstico de una cardiopatía congénita en la infancia suele ser una situación compleja para los pacientes y sus padres, que llega a convertirse en una experiencia traumática. El objetivo del presente trabajo fue identificar los predictores del crecimiento postraumático a través de las estrategias de afrontamiento al estrés, los síntomas de estrés postraumático y el apoyo social en padres de pacientes pediátricos con algún diagnóstico de cardiopatía congénita. Fue un estudio transversal, a través de un muestreo no probabilístico, se conformó una muestra de 132 madres y padres de México. Para la evaluación se utilizó el Inventario de Crecimiento Postraumático, la Escala del Impacto del Evento, Escala Multidimensional de Apoyo Social Percibido y el Cuestionario de Afrontamiento del Estrés. Los resultados mostraron que los padres presentan un crecimiento postraumático alto, el cual se explicó en un 33.6 % a través del apoyo social de los amigos, la influencia indirecta de la expresión emocional abierta, la autofocalización negativa, la evitación, el apoyo de la familia, la religión y la búsqueda de apoyo social a través de la reevaluación positiva. En conclusión, un manejo adecuado de las estrategias de afrontamiento desadaptativas en padres de niños con cardiopatías congénitas junto a la presencia de redes de apoyo social se vincula con mayor desarrollo de crecimiento postraumático.

Palabras clave: crecimiento postraumático; apoyo social; afrontamiento; cardiopatías congénitas; padres.

Abstract:

Diagnosis of congenital heart disease in childhood is often a complex situation for patients and their parents and can become a traumatic experience. The objective of this study was to identify predictors of post-traumatic growth through stress coping strategies, post-traumatic stress symptoms, and social support in parents of pediatric patients diagnosed with congenital heart disease. This was a cross-sectional study using non-probabilistic sampling, with a sample of 132 mothers and fathers from Mexico. The Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory, the Impact of Event Scale, the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, and the Stress Coping Questionnaire were used for the evaluation. The results showed that parents exhibited high posttraumatic growth, which was explained in 33.6 % of cases by social support from friends, the indirect influence of open emotional expression, negative self-focus, avoidance, family support, religion, and the search for social support through positive reevaluation. In conclusion, adequate management of maladaptive coping strategies in parents of children with congenital heart disease, together with the presence of social support networks, is linked to greater development of post-traumatic growth.

Keywords: post-traumatic growth; social support; coping; congenital heart disease; parents.

Resumo:

O diagnóstico de uma cardiopatia congênita na infância costuma ser uma situação complexa tanto para os pacientes quanto para seus pais, podendo se tornar uma experiência traumática. O objetivo deste estudo foi identificar os preditores do crescimento pós-traumático a partir das estratégias de enfrentamento do estresse, dos sintomas de estresse pós-traumático e do apoio social em pais de pacientes pediátricos com algum diagnóstico de cardiopatia congênita. Trata-se de um estudo transversal, com amostragem não probabilística, que contou com a participação de 132 mães e pais do México. Para a avaliação, foram utilizados o Inventário de Crescimento Pós-Traumático, a Escala de Impacto do Evento, a Escala Multidimensional de Apoio Social Percebido e o Questionário de Enfrentamento do Estresse. Os resultados mostraram que os pais apresentam um alto nível de crescimento pós-traumático, explicado em 33,6 % pelo apoio social de amigos, pela influência indireta da expressão emocional aberta, pela autofocalização negativa, pela evitação, pelo apoio familiar, pela religiosidade e pela busca de apoio social por meio da reavaliação positiva. Em conclusão, um manejo adequado das estratégias de enfrentamento desadaptativas em pais de crianças com cardiopatias congênitas, aliado à presença de redes de apoio social, está associado a um maior desenvolvimento do crescimento pós-traumático.

Palavras-chave: crescimento pós-traumático; apoio social; enfrentamento; cardiopatias congênitas; pais.

Recibido: 18/03/2025

Aceptado: 04/11/2025

Las cardiopatías congénitas (CC) son una de las principales causas de muerte en la población infantil (Zimmerman et al., 2020). A nivel mundial, su prevalencia en recién nacidos ha aumentado de manera constante (Liu et al., 2019). En México, la Secretaría de Salud (2022) reportó que las CC representan el padecimiento congénito más común, que afectan cada año a entre 12 y 16 mil recién nacidos.

Los niños diagnosticados con CC tienen un riesgo de mortalidad 18 veces mayor que aquellos sin esta condición, siendo los primeros cuatro años de vida el periodo más crítico (Mandalenakis et al., 2020). Sin embargo, el 75 % de los adultos con CC que alcanzan los 18 años pueden llegar a convertirse en sexagenarios (Dellborg et al., 2023). Además, más del 97 % de los niños nacidos con CC tienen probabilidades de llegar a la adultez, aunque con la necesidad de tratamiento médico de por vida, lo que convierte a sus padres en cuidadores de un niño con una enfermedad crónica (Mandalenakis et al., 2020).

El cuidado de un niño con una enfermedad crónica tiene un impacto significativo en la salud mental de sus padres, en comparación con aquellos que cuidan a niños sanos (Cohn et al., 2020). En el caso de los padres de niños con CC, la gestión de la enfermedad de sus hijos representa una fuente intensa de estrés, ya que deben afrontar múltiples intervenciones médicas, hospitalizaciones frecuentes y pronósticos inciertos (Biber et al., 2019).

Para los padres de estos niños la vida se ve alterada desde el momento del diagnóstico. Esta etapa suele estar marcada por miedo, angustia, impotencia e incertidumbre, e incluso algunos pueden experimentar una crisis emocional (Domínguez-Reyes & Torres-Rodríguez, 2021; Nayeri et al., 2021). Además, enfrentan altos niveles de estrés parental y síntomas de estrés postraumático, como preocupación constante, estado de alerta ante cualquier síntoma, falta de sueño, desajustes psicológicos severos y cambios en la dinámica familiar (Bishop et al., 2019; Domínguez-Reyes & Torres-Rodríguez, 2021).

Demianczyk et al. (2022) identificaron que los padres emplean diversas estrategias de afrontamiento, algunas de ellas desadaptativas, en respuesta a los múltiples factores estresantes de la CC. Según Roberts (2021), los padres que adoptan estrategias de afrontamiento basadas en la aceptación tienden a experimentar menores niveles de ansiedad y estrés. Sin embargo, en el mismo estudio no se encontró una relación significativa entre el afrontamiento evitativo y la ansiedad, la depresión o el estrés. De acuerdo con Casey et al. (2024), los padres de niños con CC suelen utilizar estrategias de afrontamiento adaptativas, como lo son las enfocadas en el problema. Tomando en cuenta un afrontamiento adaptativo enfocado en el problema, Eraslan y Tak (2021) señalan que las madres de pacientes pediátricos con CC que suelen afrontar de esa manera la situación de sus hijos presentan menos sintomatología depresiva.

El afrontamiento positivo, junto con el estatus social y el apoyo social, se considera un factor protector frente al estrés postraumático (EPT) o el trastorno de estrés postraumático (TEPT) (Carmassi et al., 2021). Se ha encontrado que ser padre de un niño con una enfermedad crónica aumenta significativamente el riesgo de desarrollar TEPT (Carmassi et al., 2019). En el caso de las CC, McWhorter et al. (2022) reportaron que los padres de niños con esta condición presentan síntomas clínicamente significativos de EPT, siendo las madres quienes experimentan una mayor cantidad de síntomas. Además, Yagiela et al. (2022) mencionan que los síntomas de EPT en padres de niños en cuidados intensivos se asocian con mayores síntomas depresivos y un mayor crecimiento postraumático (CPT).

Experimentar una crisis también puede traer como consecuencia la obtención de cambios positivos, lo que se conoce como el CPT. La teoría del CPT de Tedeschi y Calhoun (2004) plantea que, después de un evento traumático, algunas personas no solo se recuperan, sino que experimentan un cambio positivo en su vida. Este cambio, denominado crecimiento, se manifiesta en cinco áreas principales: mayor apreciación de la vida, relaciones interpersonales más profundas, un incremento en la fortaleza personal, descubrir nuevas posibilidades y un cambio en la espiritualidad o filosofía personal. Sin embargo, este proceso no ocurre de manera automática, pues está influenciado por la manera en que la persona afronta el trauma, por lo que las estrategias de afrontamiento juegan un papel clave en la reconstrucción de significados y en la integración de la experiencia, lo que facilita la transformación personal.

El modelo del CPT destaca la interacción entre la rumiación cognitiva y las estrategias de afrontamiento. Inicialmente, la rumiación es intrusiva y desorganizada, pero con el tiempo puede volverse deliberada, lo que permitie una reinterpretación del trauma. En este proceso, el afrontamiento activo (como la búsqueda de apoyo social, la resolución de problemas, entre otras) puede potenciar el CPT. Estudios han demostrado que estrategias como el apoyo social y la resolución de problemas están fuertemente relacionadas con el CPT, ya que ayudan a la persona a encontrar sentido en la adversidad (Tedeschi et al., 2018).

Asimismo, se han identificado factores mediadores que pueden favorecer el CPT, entre ellos la espiritualidad, el apoyo social, el optimismo y el sentido de pertenencia (Henson et al., 2021). En el caso de padres de niños con enfermedades crónicas, el intento de afrontar la situación (ya sea mediante estrategias adaptativas o desadaptativas) puede relacionarse con resultados positivos como el CPT (He et al., 2024). En particular, el apoyo social ha sido señalado como un predictor relevante del CPT (Ebrahim & Alothman, 2021).

Así, el apoyo social promueve el CPT particularmente en las dimensiones de relaciones interpersonales, fortaleza personal y nuevas posibilidades (Nouzari et al., 2019). En padres de bebés prematuros se ha encontrado que la mayor fuente de apoyo social se ha percibido de familiares y amigos (Xingyanan et al., 2025). De igual manera, se ha encontrado en padres de pacientes con enfermedades crónicas que mientras más conformes se sienten con el apoyo social recibido, más significativo es su CPT (Negri-Schwartz et al., 2024).

Carmassi et al. (2021) señalan que la efectividad de los cuidadores puede verse afectada por la presencia de síntomas de EPT, lo que repercute negativamente en su bienestar y en el de sus hijos, pues la sobreprotección es una estrategia de afrontamiento común entre los padres de niños con CC (Domínguez-Reyes & Torres-Rodríguez, 2021). Además, si bien hay estudios que destacan variables objetivas y sus relaciones con el EPT y el CPT, O’Toole et al. (2022) sugieren que la percepción subjetiva de los padres sobre la gravedad de la enfermedad de sus hijos es un factor que tiene una relación más significativa con el CPT a largo plazo.

Según Biber et al. (2019), los estudios sobre el impacto psicológico de enfermedades graves en los padres suelen centrarse en el cáncer infantil, mientras que las investigaciones sobre enfermedades cardiacas pediátricas y su repercusión en la salud mental de los padres son escasas. Asimismo, en México se han realizado pocos estudios sobre el impacto de las CC y el CPT en los padres de niños con esta condición.

Dado que los padres de niños con CC son altamente vulnerables al estrés psicológico y social en distintas etapas de la enfermedad desde el diagnóstico hasta la infancia, se genera tensión en la dinámica familiar (Lumsden et al., 2019). Por ello, Aftyka et al. (2020) enfatizan la importancia de identificar los predictores del CPT en situaciones traumáticas, como los eventos asociados con la enfermedad y la hospitalización de un niño. Esto permitiría el desarrollo de programas de apoyo psicológico y psicoterapéutico dirigidos a los padres, enfocados en brindar apoyo emocional y promover la reinterpretación positiva de la adversidad. El objetivo del presente estudio es identificar los predictores del CPT, considerando como variables independientes las estrategias de afrontamiento ante el estrés, los síntomas de EPT y el apoyo social en padres de niños con CC.

Método

Diseño

El diseño del presente estudio es no experimental y transversal.

Participantes

De esta manera, la muestra fue conformada por 132 participantes, de los cuales 122 fueron madres y 10 padres. Sobre su residencia, 18 % residía en el Estado de México, 14 % en Nuevo León, 13 % en CDMX, 12 % en Tamaulipas y el 43 % en el resto de los estados de la República mexicana. El total de la muestra contó con una media de edad de 34.37 años (DE = 7.74), teniendo las madres una media en su edad de 33.98 (DE = 7.68) y los padres (n = 10) una media de 39.2 (DE = 7.19).

Sobre las características de los pacientes, estos fueron un total de 132 pacientes pediátricos, quienes tuvieron una media de edad de 5.52 años (DE = 5.47). El 50 % de la muestra total reportó que sus hijos no presentan otra comorbilidad, el 42.4 % reportó que sí presentan otro diagnóstico además de la CC, y el 6.8 % indicó desconocer. Además, el 50 % de los pacientes recibieron cateterismo, 76.5 % se sometieron a cirugía, y 78.8 % llevan su tratamiento con medicamento. En relación con la percepción de la estabilidad de la salud de sus hijos el 52.3 % indicó una salud estable, 42.2 % frecuentemente estable, 3.8 % frecuentemente inestable y el 1.5 % percibió la salud de su hijo como inestable.

Instrumentos

Para el estudio se utilizaron los siguientes instrumentos:

El Inventario de Crecimiento Postraumático (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996), en su versión validada para población mexicana (PTGI-MX) por Quezada-Berumen y González-Ramírez (2020a). El instrumento se conforma de 14 ítems, con una estructura unifactorial, a diferencia de otras versiones. Para responder se utiliza una escala tipo Likert evaluada por en una escala de 6 puntos, dónde 0 corresponde a no experimenté este cambio como resultado de mi crisis y 5 experimenté este cambio en un grado muy grande como resultado de mi crisis, de esta manera, mayor puntuación, mayor cambio percibido. La corrección del instrumento se realiza sumando todos los ítems. En el análisis de confiabilidad, utilizando el α de Cronbach, la escala obtuvo un coeficiente de .94. Estudios han mostrado correlaciones positivas con resiliencia, afectividad positiva y gratitud (Quezada-Berumen & de la Garza-Samaniego, 2024; Quezada-Berumen & González-Ramírez, 2020b). La confiabilidad del instrumento en el presente estudio dio como resultado un Omega de McDonald de .94.

El Cuestionario de Afrontamiento al Estrés (CAE), de Sandín y Chorot (2003), se conforma de 42 afirmaciones en tiempo pasado, utilizando el formato tipo Likert (0 = Nunca y 4 = Casi siempre) para el registro de respuestas. El cuestionario se encuentra organizado en siete subescalas: (1) Búsqueda de apoyo social (BAS, ítems 6, 13, 20, 27, 34, 41), (2) Expresión emocional abierta (EEA, ítems 4, 11, 18, 25, 32, 39), (3) Religión (RLG, ítems 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42), (4) Focalización en la solución de problema (FSP, ítems 1, 8, 15, 22, 29, 36), (5) Evitación (EVT, ítems 5, 12, 19, 26, 33, 40), (6) Autofocalización negativa (AFN, ítems 2, 9, 16, 23, 30, 37) y (7) Reevaluación positiva (REP, ítems 3, 10, 17, 24, 31, 38). La corrección de la prueba se realiza sumando los valores de cada ítem, de acuerdo con las subescalas. En el trabajo de Sandín y Chorot (2003) se obtuvieron los siguientes coeficientes α de Cronbach: BAS .92, EEA .74, RLG .86, FSP .85, EVT .76, AFN .64 y REP .71. Los coeficientes Omega de McDonald con la presente muestra fueron: BAS .88, EEA .75, RLG .86, FSP .82, EVT .75, AFN .61 y REP .70.

La Escala de Impacto de Evento Revisada (EIE-R) presentada por Weiss y Marmar (1997) y validada por Báguena et al. (2001) en adultos jóvenes españoles, que se basa en la Escala de Impacto del Evento (EIE) de Horowitz et al. (1979). La escala se compone de 22 ítems, que miden Intrusión (ítems 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, 16, 20), Evitación (ítems 5, 7, 8, 11, 12, 13, 17, 22) e Hiperactivación (ítems 4, 10, 14, 15, 18, 19, 21), con una escala tipo Likert que evalúa la intensidad de la sintomatología entre 0 = Nada hasta 4 Extremadamente. La confiabilidad fue determinada a través de los coeficientes de consistencia interna, con un coeficiente Alfa de Cronbach de .87 en el factor de evitación, .95 en el factor de intrusión, el de hiperactivación y para el total de la escala. La EIE-R ha mostrado validez convergente al asociarse con indicadores de ansiedad, depresión y afectividad negativa. En el presente estudio, los coeficientes Omega de McDonald fueron .96 para la escala total, .92 para intrusión, .88 para evitación y .91 para hiperactivación.

La Escala Multidimensional de Apoyo Social Percibido (EMASP), de Zimet et al. (1988), es un instrumento de 12 ítems de tipo autoinforme, se compone por tres subescalas: Familia (ítems 3, 4, 8, 11), Amigos (ítems 1, 2, 5, 10) y Otros significativos (ítems 6, 7, 9, 12). Las respuestas se registran en una escala tipo Likert donde 1 es muy en desacuerdo y 7 es muy de acuerdo. Cuanto mayor sea la sumatoria de puntajes, mayor es el apoyo social percibido. En este trabajo se utilizó la versión adaptada al español por Landeta y Calvete (2002), en el que se reportó un Alfa de Cronbach de .90 para Otros significativos, .96 para Familia y .96 para Amigos. Además, el coeficiente Alfa de Cronbach para la escala total fue de .89, lo que indica una buena consistencia interna. La EMASP ha mostrado correlaciones significativas con bienestar psicológico y autoestima, así como asociaciones negativas con síntomas depresivos y de ansiedad, lo que respalda su validez convergente en contextos clínicos y no clínicos. En el presente estudio los coeficientes Omega de McDonald encontrados en este estudio fueron de .95 para familia, .94 para amigos, .96 para otros significativos y de .96 para el total de la escala.

Procedimiento

Para la realización de este proyecto se contó con la aprobación de Subdirección de Investigación de la Facultad de Psicología de la Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, bajo la clave FP-UANL-23-009. Se solicitó autorización a los administradores de un grupo de Facebook de padres de pacientes con CC, llegando a un acuerdo para la difusión del instrumento, apegándose al artículo 130 del Código Ético de la Sociedad Mexicana de Psicología (SMP, 2007). Una vez obtenidos los permisos, la aplicación se realizó a través de formularios de Google, difundiendo el enlace a través del grupo donde a cada persona interesada en participar se le proporcionó un consentimiento informado, y se explicó de forma clara y precisa la naturaleza del estudio, el manejo de los datos y la confidencialidad (artículos 61, 122 y 136, SMP, 2007).

La recolección de datos se realizó del 15 de noviembre de 2023 al 15 de febrero de 2024, se obtuvieron un total de 157 participaciones, de las cuales 25 fueron eliminadas por no cumplir con los criterios de inclusión, así como por dejar incompletos los instrumentos de evaluación.

Análisis de los datos

El nivel de las variables de estudio se determinó con base en el perfil promedio (con fines orientativos), calculado mediante la media aritmética entre el número de preguntas de cada cuestionario. De esta manera, mayores puntuaciones reflejan en los participantes un mayor grado de CPT, estrategias de afrontamiento, sintomatología de EPT y apoyo social en relación con las categorías de respuesta de cada instrumento.

Se verificó el supuesto de normalidad con la prueba de Kolmogorov-Smirnov. El resultado mostró que ninguna de las variables de estudio obtuvo una distribución normal, por lo que se utilizaron técnicas no paramétricas. Así, para evaluar la relación entre las variables, se utilizó Rho de Spearman considerando un valor de p < .05 para ser estadísticamente significativo. Todos los análisis descriptivos y de correlación fueron realizados en IBM SPSS Statistics 26.

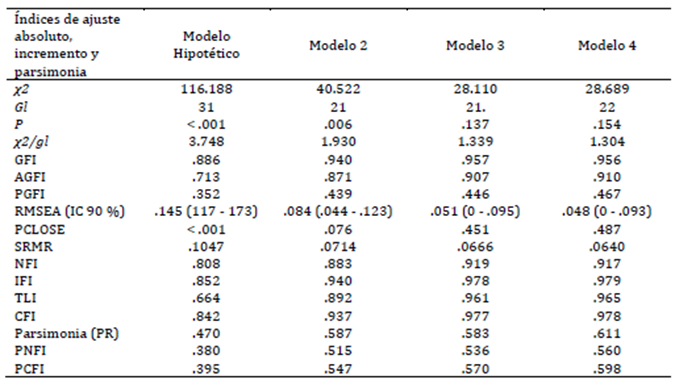

Se realizó el modelamiento de ecuaciones estructurales en SPSS Amos 24 por el método de máxima verosimilitud, ya que proporciona buenos resultados aun en condiciones de distanciamiento del supuesto de normalidad multivariante. Los presentes datos presentan índices de curtosis bajos por lo que puede ser complementado por bootstrap en la estimación de los errores (Kline, 2023; Rodríguez-Ayán & Ruiz-Díaz, 2008). El ajuste de los modelos se evaluó mediante ocho índices diferentes: la chi-cuadrada relativa (χ²/gl), el índice de bondad de ajuste (GFI), el índice de bondad de ajuste corregido (AGFI), el índice normado de ajuste (NFI), el índice comparativo de ajuste (CFI), el índice relativo de ajuste (RFI), el residuo estandarizado cuadrático medio (SRMR) y el error de aproximación cuadrático medio (RMSEA).

Un buen ajuste se considera cuando: χ²/gl es menor o igual a 2, GFI, NFI y CFI son mayores o iguales a .95, AGFI es mayor o igual a .90, y SRMR y RMSEA son menores o iguales a .05. Un ajuste aceptable se da cuando: χ²/gl es menor o igual a 3, GFI, NFI, CFI y RFI son mayores o iguales a .90, AGFI es mayor o igual a .85, y SRMR y RMSEA son menores o iguales a .08 (Arbuckle, 2013; Byrne, 2016).

La parsimonia del modelo se calculó mediante la razón de parsimonia (PR) y tres índices parsimoniosos: índice normado de ajuste parsimonioso (PNFI), índice comparativo de ajuste parsimonioso (PCFI) e índice de bondad de ajuste parsimonioso (PGFI). Una PR mayor de .75 refleja una alta parsimonia, mayor de .50 indica parsimonia media, mayor de .25 señala baja parsimonia, y menor de .25 corresponde a una parsimonia muy baja. Valores de PNFI y PCFI iguales o mayores de .80 y PGFI igual o mayor de .70 indican una buena relación parsimonia-ajuste; PNFI y PCFI iguales o mayores de .60 y PGFI igual o mayor de .50 indican una relación aceptable (Arbuckle, 2013; Mulaik et al., 1989).

Para garantizar la parsimonia y mejorar el ajuste del modelo predictivo, se realizaron pruebas sucesivas en función de criterios estadísticos. Inicialmente, se eliminaron efectos que no alcanzaron significancia estadística (p > .05). Posteriormente, aquellas vías con p > .05 fueron descartadas, lo que llevó a la exclusión de síntomas de estrés postraumático y focalización en la solución de problemas al demostrar independencia respecto al crecimiento postraumático (CPT). Las decisiones en cada iteración se sustentaron en los índices de ajuste del modelo (χ², RMSEA, CFI, TLI, SRMR) y en la mejora de su parsimonia (PNFI y PCFI). Esta refinación permitió desarrollar un modelo final exploratorio con buen ajuste, todas sus covarianzas y varianzas significativas (p < .05) y una capacidad explicativa del CPT del 33.6 %.

Resultados

Los resultados indicaron un nivel alto de CPT y moderado de EPT. Las estrategias FSP, REP y RLG se utilizaron con frecuencia moderada, mientras que las estrategias AFN, EEA, EVT y BAS fueron empleadas de forma poco frecuente. De igual forma, los participantes presentaron un AS moderadamente alto (Tabla 1).

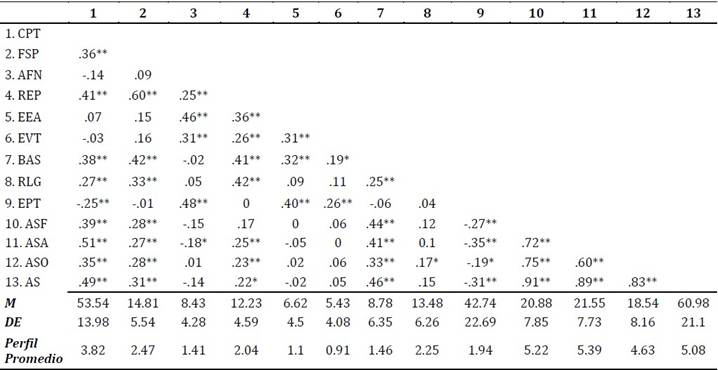

Para determinar las variables a incluir en el modelo explicativo del CPT en padres de pacientes pediátricos con algún diagnóstico de CC, fue necesario evaluar la relación entre las variables del estudio. A partir de la matriz de correlaciones se encontró que el CPT se relacionaba positivamente con la FSP, REP, BAS, RLG y AS. Sin embargo, tuvo una correlación negativa con la Sintomatología de EPT (Tabla 1).

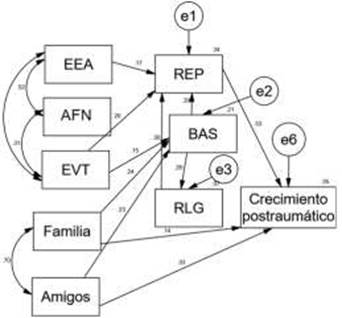

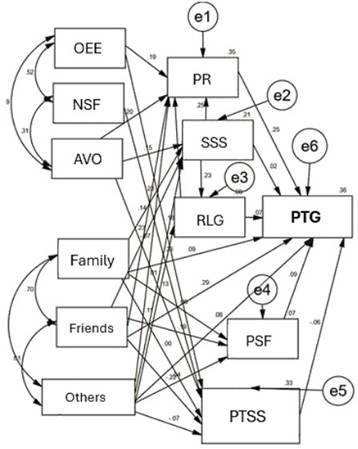

A partir de las correlaciones de la Tabla 1 y de lo mencionado por Stephenson y DeLongis (2020), se diseñó el Modelo hipotético de la Figura 1. Estos autores proponen que el afrontamiento no es un proceso estático, pues una situación estresante puede llevar a las personas a utilizar diferentes estrategias de afrontamiento en distintos momentos, incluso de manera simultánea, siendo posible que una estrategia facilite u obstaculice la eficacia de otras estrategias.

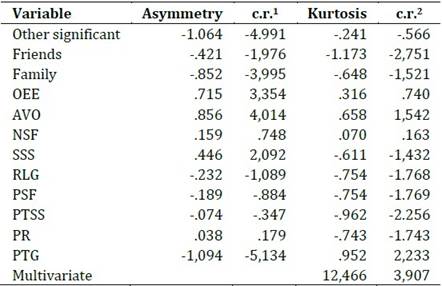

Dicho modelo propone como variables independientes al apoyo social de la familia, amigos y otras personas significativas, así como a las estrategias de afrontamiento de EEA, AFN y EVT, las cuales tienen un efecto directo hacia la sintomatología de estrés postraumático. De igual manera, como variables mediadoras hacia el CPT se proponen a las estrategias de REP, BAS, RLG, FSP y los síntomas de estrés postraumático. Considerando las variables del Modelo hipotético, se analizó la normalidad de los datos, evidenciado falta de normalidad (Tabla 2), por lo cual el cálculo se llevó a cabo con el método de bootstrap.

Tabla 1: Matriz de correlación de Spearman

Nota. 1. Crecimiento Postraumático (CPT); 2. Focalización en la Solución de Problemas (FSP); 3. Autofocalización Negativa (AFN); 4. Reevaluación Positiva (REP); 5. Expresión Emocional Abierta (EEA); 6. Evitación (EVT); 7. Búsqueda de Apoyo Social (BAS); 8. Religión (RLG); 9. Sintomatología de Estrés Postraumático (EPT); 10. Apoyo Social Familia (ASF); 11. Apoyo Social Amigos (ASA); 12. Apoyo Social de Otras Personas Significativas (ASO); 13. Apoyo Social (AS); Media (M); Desviación estándar (DE).

*p < .05; **p < .01

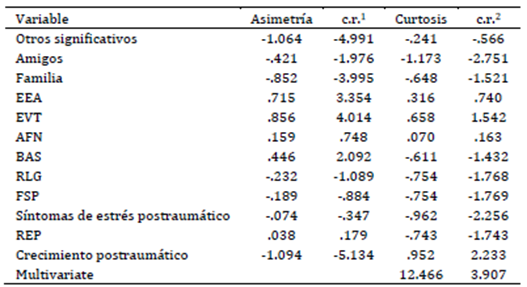

Tabla 2: Evaluación de la normalidad del modelo hipotético

Nota. Cociente entre el coeficiente de asimetría y su error estándar (c.r.1); Cociente entre el exceso de curtosis y su error estándar (c.r.2).

Figura 1: Modelo hipotético para explicar el CPT en padres de niños con CC4

Nota. Focalización en la Solución de Problemas (FSP); Autofocalización Negativa (AFN); Reevaluación Positiva (REP); Expresión Emocional Abierta (EEA); Evitación (EVT); Búsqueda de Apoyo Social (BAS); Religión (RLG); Apoyo Social Familia (Familia); Apoyo Social Amigos (Amigos); Apoyo Social de Otras Personas Significativas (Otros significativos).

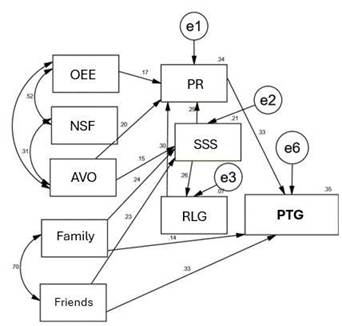

Aunque con covarianzas significativas y explicando el 35.7 % de la varianza de la variable de CPT, el Modelo hipotético mostró mal ajuste y parsimonia (Tabla 3) al igual que varias vías no significativas, por lo que se eliminaron efectos no significativos (p > .05), esto dio lugar a una nueva reestimación y con ello el Modelo 2. El Modelo 2 (Figura 2) con una varianza explicada del CPT de 34.7 % y con todas sus covarianzas y varianzas significativas (p < .05), también mostró un mal ajuste y baja parsimonia (Tabla 3), así como vías no significativas (p > .1). Tras eliminar aquellas vías con p > .05, los síntomas de EPT y la FSP resultaron independientes del CPT. Al ser variables endógenas, fueron eliminadas del modelo, lo que dio lugar a una nueva reestimación.

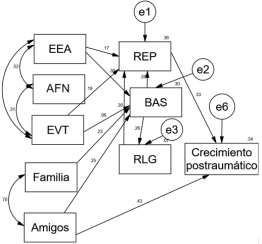

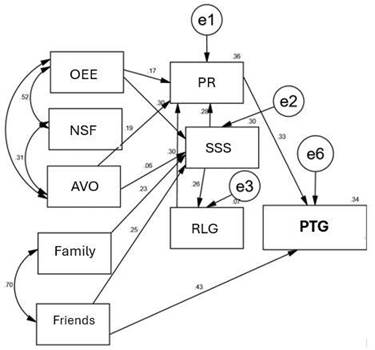

Después de eliminar las variables endógenas y el efecto del apoyo de la familia sobre el CPT, se obtuvo el Modelo 3 (Figura 3), donde los índices de ajuste y parsimonia fueron adecuados (Tabla 3). Todas las covarianzas y varianzas resultaron significativas (p < .05) y el modelo explicó un 33.6 % de la varianza del CPT. Sin embargo, se encontró una vía no significativa desde EVT hacia BAS, al igual que la incorporación de una vía sugerida por los índices de modificación, que conecta EEA con BAS.

Figura 2: Modelo 2 para explicar el CPT en padres de niños con CC

Nota. Focalización en la Solución de Problemas (FSP); Autofocalización Negativa (AFN); Reevaluación Positiva (REP); Expresión Emocional Abierta (EEA); Evitación (EVT); Búsqueda de Apoyo Social (BAS); Religión (RLG); Apoyo Social Familia (Familia); Apoyo Social Amigos (Amigos).

Figura 3: Modelo 3 para explicar el CPT en padres de niños con CC

Nota. Focalización en la Solución de Problemas (FSP); Autofocalización Negativa (AFN); Reevaluación Positiva (REP); Expresión Emocional Abierta (EEA); Evitación (EVT); Búsqueda de Apoyo Social (BAS); Religión (RLG); Apoyo Social Familia (Familia); Apoyo Social Amigos (Amigos).

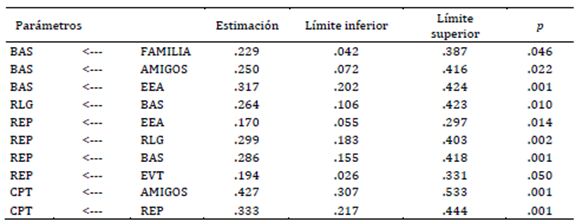

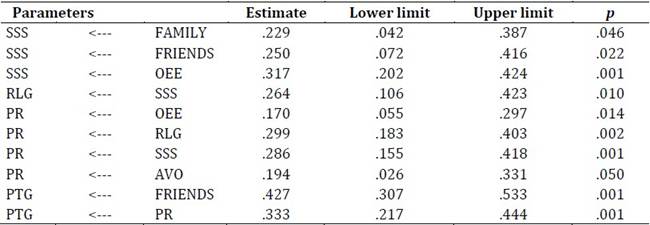

Tabla 3: Pesos estructurales estandarizados y sus intervalos de confianza al 90 % por BCa del Modelo 4

Nota. Método de percentil corregido de sesgo y aceleración (BCA).

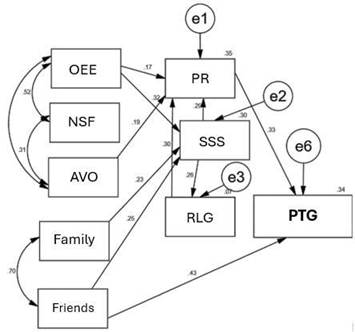

Tras la nueva reestimación, se obtuvo el Modelo 4 (Figura 4), el cual mostró un excelente ajuste (Tabla 5) y presentó indicadores significativos (p < .05), así como covarianzas y varianzas significativas (Tablas 3 y 4). Dado que el Modelo 4 logró un excelente ajuste y un indicador de parsimonia alto, se consideró como el modelo final para explicar el CPT en padres de niños con CC. Es importante destacar que las decisiones basadas en valores de p transforman este análisis en uno meramente exploratorio.

Figura 4: Modelo 4 para explicar el CPT en padres de niños con CC

Nota. Focalización en la Solución de Problemas (FSP); Autofocalización Negativa (AFN); Reevaluación Positiva (REP); Expresión Emocional Abierta (EEA); Evitación (EVT); Búsqueda de Apoyo Social (BAS); Religión (RLG); Apoyo Social Familia (Familia); Apoyo Social Amigos (Amigos).

El Modelo 4 (Figura 4) explicó el 33.6 % de la varianza, donde los principales predictores del CPT fueron el apoyo social de los amigos, el efecto indirecto de EEA, AFN y EVT, el apoyo de la familia, RLG y BAS hacia REP. De esta manera el CPT puede ser explicado por tres vías. La primera y más fuerte a través del apoyo de los amigos; la segunda mediante el efecto indirecto del apoyo de la familia y amigos a través de BAS, RLG y REP; y la tercera vía por medio de las estrategias de afrontamiento de EEA, EVT y AFN a través de REP.

En cuanto a los efectos indirectos de apoyo de la familia (β = .028; p = .020), apoyo de los amigos (β = .030; p = .033), EEA (β = .095; p = .001), EVT (β = .065; p = .032), BAS (β = .122; p = .001) y RLG (β = .100; p = .001) sobre el CPT, estos efectos resultaron significativos pero bajos (p < .05).

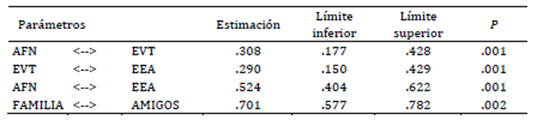

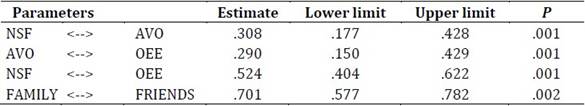

Tabla 4: Correlaciones y sus intervalos de confianza al 90 % por BCa del Modelo 4

Nota. Método de percentil corregido de sesgo y aceleración (BCA).

Tabla 5: Índices de ajuste para los modelos estimados

Discusión

Las CC son consideradas una de las principales causas de muerte infantil a nivel mundial, por lo que los padres de pacientes pediátricos con CC suelen presentar diversas respuestas adaptativas y desadaptativas frente a las complicaciones que se pueden presentar en diferentes momentos de la vida de sus hijos. En este sentido, los resultados del presente estudio indican que los padres de pacientes pediátricos con CC presentan un alto nivel de CPT y una sintomatología de EPT moderada

De manera similar, un estudio realizado en padres de bebés con diagnóstico de CC encontró que, como consecuencia del estrés parental, los padres desarrollaron altos niveles de CPT (Casey et al., 2024). En relación con el EPT, se han identificado diversos niveles en padres de pacientes con CC u otras enfermedades críticas. Por ejemplo, en el estudio de Davey et al. (2023) se menciona que las madres de bebés con CC pueden experimentar una sintomatología de EPT elevada, se destaca que aquellas que no logran adaptarse al diagnóstico suelen presentar los niveles más altos de EPT. No obstante, Yagiela et al. (2022) encontraron que padres de pacientes con enfermedades críticas presentaban en su mayoría de un CPT de moderado a alto y una sintomatología de EPT moderada.

Al evaluar las estrategias de afrontamiento, los padres suelen utilizar con mayor frecuencia estrategias adaptativas, como el afrontamiento enfocado en el problema y el afrontamiento enfocado en la emoción (Casey et al., 2024). De manera similar, las estrategias más empleadas por los padres de la presente muestra fueron REP, FSP y RLG; por el contrario, en pocas ocasiones recurrieron a AFN, EVT y BAS.

Aunque los padres de este estudio emplearon estrategias de afrontamiento positivas (Eraslan & Tak, 2021), se encontró que recurren poco a la BAS. Aunque los padres de esta investigación no recurran activamente a la BAS, Oden y Cam (2021) mencionan que éstos pueden llegar a percibir un gran respaldo tanto de la familia como de los amigos. Estos resultados coinciden con nuestros hallazgos, ya que los padres indicaron percibir altos niveles de apoyo social, especialmente por parte de sus familiares y amigos.

El uso de estrategias de afrontamiento más adaptativas y activas suele asociarse positivamente con niveles más altos de CPT en padres de pacientes pediátricos con CC (Casey et al., 2024; Peters et al., 2021). En este sentido, el uso de estrategias de afrontamiento positivas, como la REP, ayuda a las personas a interpretar los sucesos estresantes de manera más favorable, lo que los orienta hacia la generación de cambios positivos (Henson et al., 2021).

En cuanto a la relación entre los síntomas EPT y el CPT, se ha encontrado que diversas características culturales de la muestra, así como la gravedad y el tipo de evento, pueden influir en la existencia o ausencia de una asociación entre ambas variables (Peters et al., 2021). En padres de niños que estuvieron en cuidados intensivos, generalmente se observa una relación positiva entre CPT y EPT (O’Toole et al., 2022). Sin embargo, los hallazgos de este estudio revelaron una correlación negativa entre ambas variables en los padres de pacientes con CC. Esto podría explicarse, como señalan Fletcher et al. (2023), por un patrón correlacional en el que un nivel bajo de EPT y un nivel alto de CPT están relacionados con un mayor apoyo social.

Al identificar los predictores del CPT, el modelo resultante presentó tres vías principales: (1) a través del apoyo de los amigos, (2) por el efecto indirecto del apoyo de la familia y amigos a través de BAS, RLG y REP, y (3) las estrategias de afrontamiento de EEA, EVT y AFN a través de la REP.

De acuerdo con Henson et al. (2021), el CPT es promovido por diversos factores, como compartir emociones negativas con otros, el uso de estrategias de afrontamiento positivas, y como factor mediador, el apoyo social. La EEA, según el CAE, considera únicamente emociones negativas como ira, hostilidad, irritabilidad, agresión e insultos a otros. De lo anterior se deduce que expresar emociones negativas fomenta altos niveles de CPT, ya que facilita el procesamiento cognitivo (como la rumiación deliberada), lo que ayuda a normalizar tanto la situación individual como los sentimientos sobre la experiencia, lo que resulta en una REP (Dirik & Göcek-Yorulmaz, 2018; Saltzman et al., 2018).

De acuerdo con algunos autores, la EVT, como estrategia de afrontamiento, tiende a reducir la angustia y evitar pensamientos abrumadores, pues, junto con aquellas relacionadas a la aproximación, puede predecir el CPT. Así, el uso flexible de las estrategias de afrontamiento permite a las personas procesar el trauma y promover el CPT (Henson et al., 2021). En padres de niños que han estado en la unidad de cuidados intensivos, la EVT ha favorecido el CPT, ya que evitar pensamientos angustiantes, como aquellos relacionados con la muerte, contribuye a un afrontamiento más efectivo (Lynkins et al., 2007, en O’Toole et al., 2022). No obstante, en los resultados de este estudio el efecto indirecto de la EVT hacia el CPT debe ser tomado con cautela dado los bajos coeficientes.

Al enfrentar situaciones difíciles, las personas pueden experimentar malestar emocional, lo que podría llevarlas a desarrollar una actitud de afrontamiento negativa (AFN). Este enfoque las impulsa a buscar la desconexión del malestar a través de estrategias de evitación (EVT) (Zacher & Rudolph, 2021). Asimismo, la AFN, como la vergüenza, induce a las personas a expresar su enfoque negativo de manera desadaptativa, como la expresión emocional agresiva (EEA), lo que interfiere con una adecuada regulación emocional interpersonal (Swerdlow et al., 2023).

La REP como variable mediadora en este estudio es una estrategia de afrontamiento considerada adaptativa que contribuye al desarrollo del CPT. Buscar obtener algo positivo de las experiencias estresantes puede promover el CPT de manera directa o como consecuencia de una rumiación deliberada (Cárdenas et al., 2019). La REP implica el intento de interpretar los acontecimientos negativos de forma más positiva, lo que a su vez puede propiciar cambios favorables (Henson et al., 2021).

Asimismo, el sentido de pertenencia a un grupo se ha identificado como un factor que promueve la búsqueda de apoyo social, lo que contribuye al desarrollo de altos niveles de CPT (Armstrong et al., 2014). De igual manera, el hecho de que las personas busquen apoyo en grupos religiosos y se sientan parte de ellos les permite adaptarse mejor a la adversidad, llegan incluso a reevaluar la situación para darle un sentido positivo (Toledo et al., 2021). García et al. (2022) resaltan que en países latinoamericanos donde la espiritualidad y la religión forma parte importante de la comunidad, tener cercanía con estos elementos es uno de los predictores más importante del CPT al actuar como una variable mediadora.

El apoyo social percibido, especialmente el de los amigos, contribuye de manera significativa al desarrollo del CPT en las personas, ya que proporciona un entorno de confianza y comodidad que facilita la expresión emocional y el procesamiento cognitivo de experiencias traumáticas. Este respaldo es particularmente valioso en situaciones angustiantes, donde la familia también puede estar afectada, lo que permite a las personas normalizar sus sentimientos y enfrentar el trauma de manera más efectiva (Döveling, 2014; Hakulinen et al., 2016; Hasson-Ohayon et al., 2016; Palmer et al., 2017).

Actualmente, muchos programas de intervención cognitivos y psicológicos para promover el CPT no se basan en modelos teóricos relacionados con este constructo. Bae et al. (2023) recomiendan examinar las vías que facilitan el CPT con el fin de diseñar programas efectivos fundamentados en teorías específicas. En este estudio, se utilizó una teoría del CPT como base, lo que permitió desarrollar un modelo que explica el crecimiento a través de tres vías principales: la primera y más significativa vía se basa en el respaldo proporcionado por los amigos. La segunda ocurre a través del impacto indirecto del apoyo familiar y amistoso, mediado por BAS, RLG y REP. La tercera se desarrolla mediante estrategias de afrontamiento como EEA, EVT y AFN, con REP como mecanismo central.

Intervenciones recientes, basadas en hallazgos similares, han desarrollado programas enfocados en facilitar la rumiación deliberada y promover el CPT, como en el caso de mujeres con cáncer de mama. Estos programas buscan fomentar la autorrevelación y el apoyo social, al tiempo que regulan estrategias de afrontamiento desadaptativas, como la evitación, la expresión emocional abierta y la autofocalización negativa, con el propósito de facilitar una reevaluación positiva de la situación.

Finalmente, los resultados de este estudio indican que los padres de niños con CC experimentan un nivel moderado de CPT, impulsado principalmente por el apoyo social percibido de los amigos, las estrategias de afrontamiento BAS y RLG, así como el apoyo de la familia y amigos a través de la REP. Asimismo, las estrategias de afrontamiento EEA, AFN y EVT interactúan entre sí, lo que facilita una reevaluación positiva de los eventos relacionados con la CC de sus hijos. Además, el apoyo de los amigos desempeña un papel fundamental, ya que no solo contribuye directamente al CPT, sino que también influye en la REP de la enfermedad.

Este estudio presenta varias limitaciones que sugieren recomendaciones para futuras investigaciones. Una de las principales limitaciones fue el uso de un muestreo por conveniencia, lo que reduce la representatividad de los resultados. Lo anterior limita la diversidad y reduce la representatividad de la muestra frente al universo poblacional, esto resulta en relaciones explicativas del modelo poco generalizables o distorsionadas; por ello, se recomienda emplear un muestreo aleatorio en estudios posteriores. Adicionalmente genera un sesgo, ya que existe mayor posibilidad de representar a personas con mayor nivel educativo, ingresos, familiaridad tecnológica y residencia urbana. Lo anterior excluye a grupos con menor conectividad, como personas mayores o de comunidades rurales, afectando la diversidad de la muestra y limitando así su validez, por lo que dichos resultados deben considerar estos aspectos.

Además, el tamaño de la muestra representó otra limitación importante para el tipo de análisis presentado, por lo que incrementar el número de participantes permitiría realizar análisis más robustos. La muestra estuvo compuesta principalmente por mujeres, lo que limita la generalización de los hallazgos a todos los padres. Se sugiere buscar una muestra equilibrada entre hombres y mujeres, dado que padres y madres de niños con CC suelen utilizar estrategias de afrontamiento diferentes, lo que podría influir en el CPT.

Asimismo, no se pudo acceder al historial médico de los hijos, incluyendo información relevante como el tipo de CC y el número de procedimientos médicos, factores que podrían afectar el estrés parental y el CPT. También se recomienda evaluar la percepción subjetiva de los padres sobre la gravedad de la enfermedad de sus hijos, ya que esta ha sido identificada como un predictor del CPT mediado por el apoyo social.

Otra limitación fue no considerar el tiempo transcurrido desde el diagnóstico como variable, a pesar de que eventos estresantes, como la enfermedad de un hijo, pueden influir de manera distinta en las personas a lo largo del tiempo. Incluir esta variable en futuros estudios podría ser relevante, dado que se ha asociado con el CPT.

Así, el apoyo familiar, cuando es mediado por estrategias como BAS y la REP, adquiere una relevancia significativa tanto en el ámbito científico como clínico. Estas estrategias permiten comprender cómo el apoyo social se transforma en recursos psicológicos que fortalecen el CPT y pudieran reducir el uso de estrategias evitativas, como la EEA, EVT y AFN. Aunque los efectos observados sean bajos, la REP destaca como un mecanismo central que modula el impacto del apoyo recibido, lo que aporta profundidad al modelo. Un manejo adecuado de las estrategias de afrontamiento desadaptativas en padres de niños con CC, combinado con el apoyo social, podría promover un mayor desarrollo de CPT.

Referencias:

Aftyka, A., Rozalska, I., & Milanowska, J. (2020). Is post-traumatic growth possible in the parents of former patients of neonatal intensive care units? Annals of Agricultural and Environmental Medicine, 27(1), 106-112. https://doi.org/10.26444/aaem/105800

Arbuckle, J. L. (2013). IBM SPSS Amos 22: User's guide. Amos Development Corporation.

Armstrong, D., Shakespeare‐finch, J., & Shochet, I. (2014). Predicting post‐traumatic growth and post‐traumatic stress in firefighters. Australian Journal of Psychology, 66(1), 38-46. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajpy.12032

Bae, K. R., So, W. Y., & Jang, S. (2023). Effects of a post-traumatic growth program on young Korean breast cancer survivors. Healthcare, 11(1), 140. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11010140

Báguena, M. J., Villarroya, E., Beleña, A., Díaz, A., Roldán, C., & Reig, R. (2001). Propiedades psicométricas de la versión española de la Escala Revisada de Impacto del Estresor (EIE-R). Análisis y Modificación de Conducta, 27(114), 581-604.

Biber, S., Andonian, C., Beckmann, J., Ewert, P., Freilinger, S., Nagdyman, N., Kaemmerer, H., Oberhoffer, R., Pieper, L., & Neidenbach, R. C. (2019). Current research status on the psychological situation of parents of children with congenital heart disease. Cardiovascular Diagnosis and Therapy, 9(2), 369-376. https://doi.org/10.21037/cdt.2019.07.07

Bishop, M. N., Gise, J. E., Donati, M. R., Shneider, C. E., Aylward, B. S., & Cohen, L. L. (2019). Parenting stress, sleep, and psychological adjustment in parents of infants and toddlers with congenital heart disease. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 44(8), 980-987. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jsz026

Byrne, B. M. (2016). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming (3a ed.). Routledge.

Cárdenas Castro, M., Arnoso Martínez, M., & Faúndez Abarca, X. (2019). Deliberate rumination and positive reappraisal as serial mediators between life impact and posttraumatic growth in victims of state terrorism in Chile (1973-1990). Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 34(3), 545-561. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260516642294

Carmassi, C., Corsi, M., Bertelloni, C. A., Pedrinelli, V., Massimetti, G., Peroni, D. G., Bonuccelli, A., Orsini, A., & Dell'Osso, L. (2019). Post-traumatic stress and major depressive disorders in parent caregivers of children with a chronic disorder. Psychiatry Research, 279, 195-200. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2019.02.062

Carmassi, C., Dell’Oste, V., Foghi, C., Bertelloni, C. A., Conti, E., Calderoni, S., Battini, R., & Dell’Osso, L. (2021). Post-traumatic stress reactions in caregivers of children and adolescents/young adults with severe diseases: A systematic review of risk and protective factors. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(1), e189. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18010189

Casey, T., Matthews, C., Lavelle, M., Kenny, D., & Hevey, D. (2024). Exploring relationships between parental stress, coping, and psychological outcomes for parents of infants with CHD. Cardiology in the Young, 34(10), 2189-2200. https://doi.org/10.1017/S104795112402568X

Cohn, L. N., Pechlivanoglou, P., Lee, Y., Mahant, S., Orkin, J., Marson, A., & Cohen, E. (2020). Health outcomes of parents of children with chronic illness: a systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Pediatrics, 218, 166-177. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2019.10.068

Davey, B. T., Lee, J. H., Manchester, A., Gunnlaugsson, S., Ohannessian, C. M., Rodrigues, R., & Popp, J. (2023). Maternal reaction and psychological coping after diagnosis of congenital heart disease. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 27(4), 671-679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-023-03599-3

Dellborg, M., Giang, K. W., Eriksson, P., Liden, H., Fedchenko, M., Ahnfelt, A., Rosengren, A., & Mandalenakis, Z. (2023). Adults with congenital heart disease: Trends in event-free survival past middle age. Circulation, 147(12), 930-938. https://doi.org/10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.122.060834

Demianczyk, A. C., Driscoll, C. F., Karpyn, A., Shillingford, A., Kazak, A. E., & Sood, E. (2022). Coping strategies used by mothers and fathers following diagnosis of congenital heart disease. Child: Care, Health and Development, 48(1), 129-138. https://doi.org/10.1111/cch.12913

Dirik, G., & Göcek-Yorulmaz, E. (2018). Positive sides of the disease: Posttraumatic growth in adults with type 2 diabetes. Behavioral Medicine, 44(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1080/08964289.2016.1173635

Domínguez-Reyes, M. Y., & Torres-Rodríguez, I. L. (2021). Experiencias materno-paternas en el afrontamiento a la cardiopatía congénita infantil. Gaceta Médica Espirituana, 23(3), 50-61.

Döveling, K. (2014). Emotion regulation in bereavement: Searching for and finding emotional support in social network sites. New Review of Hypermedia and Multimedia, 21(1-2), 106-122. https://doi.org/10.1080/13614568.2014.983558

Ebrahim, M. T., & Alothman, A. A. (2021). Resilience and social support as predictors of post-traumatic growth in mothers of children with autism spectrum disorder in Saudi Arabia. Research in Developmental Disabilities, 113, e103943. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ridd.2021.103943

Eraslan, P., & Tak, S. (2021). Coping strategies and relation with depression levels of mothers of children with congenital heart diseases. Turkish Journal of Clinics and Laboratory, 12(4), 391-397. https://doi.org/10.18663/tjcl.973367

Fletcher, S., Mitchell, S., Curran, D., Armour, C., & Hanna, D. (2023). Empirically derived patterns of posttraumatic stress and growth: A systematic review. Trauma, Violence, & Abuse, 24(5), 3132-3150. https://doi.org/10.1177/15248380221129580

García, F. E., Rivera, C., & Garabito, S. R. (2022). Posttraumatic growth in Latin America: What is it, what is known and what is its usefulness? En C. H. García-Cadena (Ed.), Research on Hispanic Psychology (Vol. 2, pp. 11-16). Nova.

Hakulinen, C., Pulkki-Råback, L., Jokela, M., Ferrie, J.E. Aalto, A. Kivimäki, M., Vahtera, J., & Elovainio, M. (2016). Structural and functional aspects of social support as predictors of mental and physical health trajectories: Whitehall II cohort study. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 70(7), 710-715. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2015-206165

Hasson-Ohayon, I., Tuval-Mashiach, R., Goldzweig, G., Levi, R., Pizem, N., & Kaufman, B. (2016). The need for friendships and information: Dimensions of social support and posttraumatic growth among women with breast cancer. Palliative and Supportive Care, 14(4), 387-392. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1478951515001042

He, M., Shi, B., Zheng, Q., Gong, C., & Huang, H. (2024). Posttraumatic growth and its correlates among parents of children with cleft lip and/or palate. The Cleft Palate Craniofacial Journal, 61(1), 110-118. https://doi.org/10.1177/10556656221118425

Henson, C., Truchot, D., & Canevello, A. (2021). What promotes post traumatic growth? A systematic review. European Journal of Trauma & Dissociation, 5(4), e100195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejtd.2020.100195

Horowitz, M., Wilner, N., & Alvarez, W. (1979). Impact of Event Scale: A measure of subjective stress. Biopsychosocial Science and Medicine, 41(3), 209-218. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006842-197905000-00004

Kline, R. B. (2023). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling. Guilford Publications.

Landeta, O., & Calvete, E. (2002). Adaptación y validación de la escala multidimensional de apoyo social percibido. Ansiedad y Estrés, 8(2-3), 173-182.

Liu, Y., Chen, S., Zühlke, L., Black, G. C., Choy, M. K., Li, N., & Keavney, B. D. (2019). Global birth prevalence of congenital heart defects 1970–2017: Updated systematic review and meta-analysis of 260 studies. International Journal of Epidemiology, 48(2), 455-463. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyz009

Lumsden, M. R., Smith, D. M., & Wittkowski, A. (2019). Coping in parents of children with congenital heart disease: A systematic review and meta-synthesis. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 28, 1736-1753. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-019-01406-8

Mandalenakis, Z., Giang, K. W., Eriksson, P., Liden, H., Synnergren, M., Wåhlander, H., Fedchenko, M., Rosengren, A., & Dellborg, M. (2020). Survival in children with congenital heart disease: have we reached a peak at 97%? Journal of the American Heart Association, 9(22), e017704. https://doi.org/10.1161/JAHA.120.017704

McWhorter, L. G., Christofferson, J., Neely, T., Hildenbrand, A. K., Alderfer, M. A., Randall, A., Kazak, A. E., & Sood, E. (2022). Parental post-traumatic stress, overprotective parenting, and emotional and behavioral problems for children with critical congenital heart disease. Cardiology in the Young, 32(5), 738-745. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1047951121002912

Mulaik, S. A., James, L. R., Van Alstine, J., Bennett, N., Lind, S., & Stilwell, C. D. (1989). Evaluation of goodness-of-fit indices for structural equation models. Psychological Bulletin, 105, 430-445. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.105.3.43

Nayeri, N. D., Roddehghan, Z., Mahmoodi, F., & Mahmoodi, P. (2021). Being parent of a child with congenital heart disease, what does it mean? A qualitative research. BMC Psychology, 9, 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-021-00539-0

Negri-Schwartz, O., Lavidor, M., Shilton, T., Gothelf, D., & Hasson-Ohayon, I. (2024). Post-traumatic growth correlates among parents of children with chronic illnesses: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 109, 102409. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2024.102409

Nouzari, R., Najafi, S. S., & Momennasab, M. (2019). Post-traumatic growth among family caregivers of cancer patients and its association with social support and hope. International Journal of Community Based Nursing and Midwifery, 7(4), 319-328. https://doi.org/10.30476/IJCBNM.2019.73959.0

O’Toole, S., Suarez, C., Adair, P., McAleese, A., Willis, S., & McCormack, D. (2022). A systematic review of the factors associated with post-traumatic growth in parents following admission of their child to the intensive care unit. Journal of Clinical Psychology in Medical Settings, 29(3), 509-537. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10880-022-09880-x

Oden, T. N., & Cam, R. (2021). The relationship between hopelessness and perceived social support levels of parents with children with congenital heart disease. Medical Science and Discovery, 8(11), 655-661. https://doi.org/10.36472/msd.v8i11.625

Palmer, E., Murphy, D., & Spencer-Harper, L. (2017). Experience of post-traumatic growth in UK veterans with PTSD: A qualitative study. BMJ Military Health, 163(3), 171-176. https://doi.org/10.1136/jramc-2015-000607

Peters, J., Bellet, B. W., Jones, P. J., Wu, G. W., Wang, L., & McNally, R. J. (2021). Posttraumatic stress or posttraumatic growth? Using network analysis to explore the relationships between coping styles and trauma outcomes. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 78, 102359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102359

Quezada-Berumen, L., & de la Garza-Samaniego, A. (2024). Rumiación, gratitud y afecto positivo y negativo como predictores del crecimiento postraumático en deudos por COVID-19. Ansiedad y Estrés, 30(1), 49 -55. https://doi.org/10.5093/anyes2024a7

Quezada-Berumen, L., & González-Ramírez, M. T. (2020a). Propiedades psicométricas del inventario de crecimiento postraumático en población mexicana. Acción Psicológica, 17(1), 13-28. https://doi.org/10.5944/17.1.25736

Quezada-Berumen, L., & González-Ramírez, M. T. (2020b). Predictores del crecimiento postraumático en hombres y mujeres. Ansiedad y Estrés, 26(2-3), 98-106. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anyes.2020.05.002

Roberts, S. D., Kazazian, V., Ford, M. K., Marini, D., Miller, S. P., Chau, V., Seed, M., Ly, L.G., Williams, T. S., & Sananes, R. (2021). The association between parent stress, coping and mental health, and neurodevelopmental outcomes of infants with congenital heart disease. The Clinical Neuropsychologist, 35(5), 948-972. https://doi.org/10.1080/13854046.2021.1896037

Rodríguez-Ayán, N. M., & Ruiz-Díaz, M. Á. (2008). Atenuación de la asimetría y de la curtosis de las puntuaciones observadas mediante transformaciones de variables: Incidencia sobre la estructura factorial. Psicológica, 29(2), 205-277.

Saltzman, L. Y., Pat-Horenczyk, R., Lombe, M., Weltman, A., Ziv, Y., McNamara, T., Takeuchi, D., & Brom, D. (2018). Post-combat adaptation: Improving social support and reaching constructive growth. Anxiety, Stress, & Coping, 31(4), 418-430. https://doi.org/10.1080/10615806.2018.1454740

Sandín, B., & Chorot, P. (2003). Cuestionario de Afrontamiento del Estrés (CAE): Desarrollo y validación preliminar. Revista de Psicopatología y Psicología Clínica, 8(1), 39-53. https://doi.org/10.5944/rppc.vol.8.num.1.2003.3941

Secretaría de Salud. (2022, 14 de febrero). Al año nacen en México entre 12 mil y 16 mil infantes con afecciones cardiacas. Gobierno de México. https://acortar.link/l7r2de

Sociedad Mexicana de Psicología. (2007). Código ético del Psicólogo. Trillas.

Stephenson, E., & DeLongis, A. (2020). Coping strategies. En K. Sweeny, M. L. Robbins & L. M. Cohen (Eds.), The Wiley Encyclopedia of Health Psychology, (pp. 55-60). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119057840.ch50

Swerdlow, B. A., Sandel, D. B., & Johnson, S. L. (2023). Shame on me for needing you: A multistudy examination of links between receiving interpersonal emotion regulation and experiencing shame. Emotion, 23(3), 737-752. https://doi.org/10.1037/emo0001109

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (1996). The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory: Measuring the positive legacy of trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 9, 455-471. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02103658

Tedeschi, R. G., & Calhoun, L. G. (2004). Posttraumatic growth: Conceptual foundations and empirical evidence. Psychological Inquiry, 15(1), 1-18. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327965pli1501_01

Tedeschi, R. G., Shakespeare-Finch, J., Taku, K., & Calhoun, L. G. (2018). Posttraumatic Growth: Theory, Research, and Applications. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315527451

Toledo, G., Ochoa, C. Y., & Farias, A. J. (2021). Religion and spirituality: Their role in the psychosocial adjustment to breast cancer and subsequent symptom management of adjuvant endocrine therapy. Support Care in Cancer, 29, 3017-3024. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00520-020-05722-4

Weiss, D. S., & Marmar, C. R. (1997). The Impact of Event Scale-Revised. En J. P. Wilson & T. M. Keane (Eds.), Assessing Psychological Trauma and PTSD (pp. 399-411). The Guilford Press.

Xingyanan, W., Yuanhong, L., Yang, L., & Zhitian, X. (2025). A cross-sectional study on posttraumatic growth and influencing factors among parents of premature infants. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 25(1), 26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-025-07137-7

Yagiela, L. M., Edgar, C. M., Harper, F. W., & Meert, K. L. (2022). Parent posttraumatic growth after a child's critical illness. Frontiers in Pediatrics, 10, e989053. https://doi.org/10.3389/fped.2022.989053

Zacher, H. & Rudolph, C. W. (2021). Individual differences and changes in subjective wellbeing during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist, 76(1). https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000702

Zimet, G. D., Dahlem, N. W., Zimet, S. G., & Farley, G. K. (1988). The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support. Journal of Personality Assessment, 52(1), 30-41. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa5201_2

Zimmerman, M. S., Smith, A. G. C., Sable, C. A., Echko, M. M., Wilner, L. B., Olsen, H. E., Atalay, H. T., Awasthi, A., Bhutta, Z. A., Boucher, J. L., Castro, F., Cortesi, P. A., Dubey, M., Fischer, F., Hamidi, S., Hay, S. I., Hoang, C. L., Hugo-Hamman, C. T., Jenkins, K. J., ... & Kassebaum, N. J. (2020). Global, regional, and national burden of congenital heart disease, 1990–2017: A systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. The Lancet Child & Adolescent Health, 4(3), 185-200. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2352-4642(19)30402-X

Financiamiento: La presente investigación fue autofinanciada.

Conflicto de interés: No existen conflictos de interés vinculados a la investigación, la autoría o la publicación de este manuscrito.

Disponibilidad de datos: El conjunto de datos que apoya los resultados de este estudio no se encuentra disponible.

Cómo citar: De la Garza Samaniego, A. L., & Quezada Berumen, L. (2025). Modelo predictivo del crecimiento postraumático en padres de pacientes con cardiopatías congénitas. Ciencias Psicológicas, 19(2), e-4530. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v19i2.4530

Contribución de los autores (Taxonomía CRediT): 1. Conceptualización; 2. Curación de datos; 3. Análisis formal; 4. Adquisición de fondos; 5. Investigación; 6. Metodología; 7. Administración de proyecto; 8. Recursos; 9. Software; 10. Supervisión; 11. Validación; 12. Visualización; 13. Redacción: borrador original; 14. Redacción: revisión y edición.

A. L. de la G. S. ha contribuido en 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 9, 13, 14.; L. Q. B. en 1, 3, 6, 10, 11, 13, 14.

Editora científica responsable: Dra. Cecilia Cracco.

Ciencias Psicológicas; v19(2)

July-December 2025

10.22235/cp.v19i2.4530

Original Articles

Predictive Model of Posttraumatic Growth in Parents of Pediatric Patients

with Congenital Heart Disease

Modelo predictivo del crecimiento postraumático

en padres de pacientes con cardiopatías congénitas

Modelo preditivo do crescimento pós-traumático em pais de pacientes

com cardiopatias congênitas

Alma Leticia de la Garza Samaniego1 ORCID 0009-0001-1400-1173

Lucía Quezada Berumen2 ORCID 0000-0003-4705-3225

1 Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, México

2 Universidad Autónoma de Nuevo León, México, [email protected]

Abstract:

Diagnosis of congenital heart disease in childhood is often a complex situation for patients and their parents and can become a traumatic experience. The objective of this study was to identify predictors of post-traumatic growth through stress coping strategies, post-traumatic stress symptoms, and social support in parents of pediatric patients diagnosed with congenital heart disease. This was a cross-sectional study using non-probabilistic sampling, with a sample of 132 mothers and fathers from Mexico. The Post-Traumatic Growth Inventory, the Impact of Event Scale, the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support, and the Stress Coping Questionnaire were used for the evaluation. The results showed that parents exhibited high posttraumatic growth, which was explained in 33.6 % of cases by social support from friends, the indirect influence of open emotional expression, negative self-focus, avoidance, family support, religion, and the search for social support through positive reevaluation. In conclusion, adequate management of maladaptive coping strategies in parents of children with congenital heart disease, together with the presence of social support networks, is linked to greater development of post-traumatic growth.

Keywords: post-traumatic growth; social support; coping; congenital heart disease; parents.

Resumen:

El diagnóstico de una cardiopatía congénita en la infancia suele ser una situación compleja para los pacientes y sus padres, que llega a convertirse en una experiencia traumática. El objetivo del presente trabajo fue identificar los predictores del crecimiento postraumático a través de las estrategias de afrontamiento al estrés, los síntomas de estrés postraumático y el apoyo social en padres de pacientes pediátricos con algún diagnóstico de cardiopatía congénita. Fue un estudio transversal, a través de un muestreo no probabilístico, se conformó una muestra de 132 madres y padres de México. Para la evaluación se utilizó el Inventario de Crecimiento Postraumático, la Escala del Impacto del Evento, Escala Multidimensional de Apoyo Social Percibido y el Cuestionario de Afrontamiento del Estrés. Los resultados mostraron que los padres presentan un crecimiento postraumático alto, el cual se explicó en un 33.6 % a través del apoyo social de los amigos, la influencia indirecta de la expresión emocional abierta, la autofocalización negativa, la evitación, el apoyo de la familia, la religión y la búsqueda de apoyo social a través de la reevaluación positiva. En conclusión, un manejo adecuado de las estrategias de afrontamiento desadaptativas en padres de niños con cardiopatías congénitas junto a la presencia de redes de apoyo social se vincula con mayor desarrollo de crecimiento postraumático.

Palabras clave: crecimiento postraumático; apoyo social; afrontamiento; cardiopatías congénitas; padres.

Resumo:

O diagnóstico de uma cardiopatia congênita na infância costuma ser uma situação complexa tanto para os pacientes quanto para seus pais, podendo se tornar uma experiência traumática. O objetivo deste estudo foi identificar os preditores do crescimento pós-traumático a partir das estratégias de enfrentamento do estresse, dos sintomas de estresse pós-traumático e do apoio social em pais de pacientes pediátricos com algum diagnóstico de cardiopatia congênita. Trata-se de um estudo transversal, com amostragem não probabilística, que contou com a participação de 132 mães e pais do México. Para a avaliação, foram utilizados o Inventário de Crescimento Pós-Traumático, a Escala de Impacto do Evento, a Escala Multidimensional de Apoio Social Percebido e o Questionário de Enfrentamento do Estresse. Os resultados mostraram que os pais apresentam um alto nível de crescimento pós-traumático, explicado em 33,6 % pelo apoio social de amigos, pela influência indireta da expressão emocional aberta, pela autofocalização negativa, pela evitação, pelo apoio familiar, pela religiosidade e pela busca de apoio social por meio da reavaliação positiva. Em conclusão, um manejo adequado das estratégias de enfrentamento desadaptativas em pais de crianças com cardiopatias congênitas, aliado à presença de redes de apoio social, está associado a um maior desenvolvimento do crescimento pós-traumático.

Palavras-chave: crescimento pós-traumático; apoio social; enfrentamento; cardiopatias congênitas; pais.

Received: 03/18/2025

Accepted: 11/04/2025

Congenital heart disease (CHD) is one of the leading causes of death in children (Zimmerman et al., 2020). Globally, its prevalence in newborns has been steadily increasing (Liu et al., 2019). In Mexico, the Ministry of Health (2022) reported that CHD is the most common congenital condition, affecting between 12,000 and 16,000 newborns each year.

Children diagnosed with CH have an 18 times higher risk of mortality than those without this condition, with the first four years of life being the most critical period (Mandalenakis et al., 2020). However, 75 % of adults with CHD who reach the age of 18 can live to be 60 years old (Dellborg et al., 2023). In addition, more than 97 % of children born with CHD are likely to reach adulthood, although they will require lifelong medical treatment, which makes their parents caregivers of a child with chronic illness (Mandalenakis et al., 2020).

Caring for a child with chronic illness has a significant impact on the mental health of their parents, compared to those who care for healthy children (Cohn et al., 2020). For parents of children with chronic conditions, managing their children's illness is a major source of stress, as they must cope with multiple medical interventions, frequent hospitalizations, and uncertain prognoses (Biber et al., 2019).

For the parents of these children, life is altered from the moment of diagnosis. This stage is often marked by fear, distress, helplessness, and uncertainty, and some may even experience an emotional crisis (Domínguez-Reyes & Torres-Rodríguez, 2021; Nayeri et al., 2021). In addition, they face high levels of parental stress and symptoms of post-traumatic stress, such as constant worry, alertness to any symptoms, lack of sleep, severe psychological maladjustment, and changes in family dynamics (Bishop et al., 2019; Domínguez-Reyes & Torres-Rodríguez, 2021).

Demianczyk et al. (2022) identified that parents use various coping strategies, some of them maladaptive, in response to the multiple stressors of CHD. According to Roberts (2021), parents who adopt acceptance-based coping strategies tend to experience lower levels of anxiety and stress. However, the same study found no significant relationship between avoidant coping and anxiety, depression, or stress. According to Casey et al. (2024), parents of children with CHD often use adaptive coping strategies, such as those focused on the problem. Considering adaptive coping focused on the problem, Eraslan and Tak (2021) point out that mothers of pediatric patients with CHD who tend to cope with their children's situation in this way have fewer depressive symptoms.

Positive coping, along with social status and social support, is considered a protective factor against post-traumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Carmassi et al., 2021). It has been found that being the parent of a child with a chronic illness significantly increases the risk of developing PTSD (Carmassi et al., 2019). In the case of CHD, McWhorter et al. (2022) reported that parents of children with this condition have clinically significant symptoms of PTSD, with mothers experiencing a greater number of symptoms. In addition, Yagiela et al. (2022) mention that PTSD symptoms in parents of children in intensive care are associated with greater depressive symptoms and greater post-traumatic growth (PTG).

Experiencing a crisis can also result in positive changes, known as PTG. Tedeschi and Calhoun's (2004) theory of PTG posits that, after a traumatic event, some people not only recover but experience a positive change in their lives. This change, called growth, manifests itself in five main areas: greater appreciation of life, deeper interpersonal relationships, increased personal strength, discovery of new possibilities, and a change in spirituality or personal philosophy. However, this process does not occur automatically, as it is influenced by the way the person copes with the trauma, so coping strategies play a key role in reconstructing meanings and integrating the experience, facilitating personal transformation.

The PTG model highlights the interaction between cognitive rumination and coping strategies. Initially, rumination is intrusive and disorganized, but over time it can become deliberate, allowing for a reinterpretation of the trauma. In this process, active coping (such as seeking social support, problem solving, among others) can enhance PTG. Studies have shown that strategies such as social support and problem solving are strongly related to PTG, as they help the person find meaning in adversity (Tedeschi et al., 2018).

Mediating factors that can promote PTG have been identified, including spirituality, social support, optimism, and a sense of belonging (Henson et al., 2021). In the case of parents of children with chronic illnesses, attempting to cope with the situation (whether through adaptive or maladaptive strategies) may be related to positive outcomes such as PTG (He et al., 2024). Social support has been identified as a relevant predictor of PTG (Ebrahim & Alothman, 2021).

Thus, social support promotes PTG particularly in the dimensions of interpersonal relationships, personal strength, and new possibilities (Nouzari et al., 2019). In parents of premature babies, it has been found that the greatest source of social support has been perceived to come from family and friends (Xingyanan et al., 2025). Similarly, it has been found in parents of patients with chronic diseases that the more satisfied they feel with the social support received, the more significant their PTG is (Negri-Schwartz et al., 2024).

Carmassi et al. (2021) point out that the effectiveness of caregivers can be affected by the presence of PTSS, which negatively impacts their well-being and that of their children, as overprotection is a common coping strategy among parents of children with CHD (Domínguez-Reyes & Torres-Rodríguez, 2021). Furthermore, while some studies highlight objective variables and their relationship with PTG and PTG, O'Toole et al. (2022) suggest that parents' subjective perception of the severity of their children's illness is a factor that has a more significant relationship with long-term PTG.

According to Biber et al. (2019), studies on the psychological impact of serious illnesses on parents tend to focus on childhood cancer, while research on pediatric heart disease and its impact on parents' mental health is scarce. Likewise, in Mexico, few studies have been conducted on the impact of CHD and PTG on parents of children with this condition.

Given that parents of children with CHD are highly vulnerable to psychological and social stress at different stages of the disease, from diagnosis to childhood, tension is generated in family dynamics (Lumsden et al., 2019). Therefore, Aftyka et al. (2020) emphasize the importance of identifying predictors of PTG in traumatic situations, such as events associated with illness and hospitalization of a child. This would allow for the development of psychological and psychotherapeutic support programs aimed at parents, focused on providing emotional support and promoting positive reinterpretation of adversity. The objective of the present study is to identify predictors of PTG, considering stress coping strategies, PTSS, and social support in parents of children with CHD as independent variables.

Method

Design

The design of this study is non-experimental and cross-sectional.

Participants

A non-probability convenience sample was taken, including mothers and fathers of pediatric patients diagnosed with a CHD at least one month prior to the study. To participate in the study, the inclusion criteria established that parents must be of legal age, reside in Mexico, have literacy skills, and have a mobile device with internet access.

Thus, the sample consisted of 132 participants, of whom 122 were mothers and 10 were fathers. Regarding their place of residence, 18 % lived in the State of Mexico, 14 % in Nuevo León, 13 % in Mexico City, 12 % in Tamaulipas, and 43 % in the rest of the states of the Mexican Republic. The total sample had a mean age of 34.37 years (SD = 7.74), with mothers having a mean age of 33.98 (SD = 7.68) and fathers (n = 10) having a mean age of 39.2 (SD = 7.19).

Regarding the characteristics of the patients, there were a total of 132 pediatric patients, who had a mean age of 5.52 years (SD = 5.47). Fifty percent of the total sample reported that their children had no other comorbidities, 42.4 % reported that they had another diagnosis in addition to CHD, and 6.8 % indicated that they did not know. In addition, 50 % of patients underwent catheterization, 76.5 % underwent surgery, and 78.8 % are undergoing treatment with medication. Regarding the perception of their children's health stability, 52.3 % indicated stable health, 42.2 % frequently stable, 3.8 % frequently unstable, and 1.5 % perceived their child's health as unstable.

Instruments

The following instruments were used for the study:

The Posttraumatic Growth Inventory (Tedeschi & Calhoun, 1996), in its version validated for the Mexican population (PTGI-MX) by Quezada-Berumen and González-Ramírez (2020a). The instrument consists of 14 items, with a unifactorial structure, unlike other versions. Responses are given on a 6-point Likert scale, where 0 corresponds to “I did not experience this change as a result of my crisis” and 5 to “I experienced this change to a very large degree as a result of my crisis.” Thus, a higher score indicates a greater perceived change. The instrument is corrected by adding up all the items. In the reliability analysis, using Cronbach's α, the scale obtained a coefficient of .94. Studies have shown positive correlations with resilience, positive affectivity, and gratitude (Quezada-Berumen & de la Garza-Samaniego, 2024; Quezada-Berumen & González, 2020b). The reliability of the instrument in the present study resulted in a McDonald's Omega of .94.

The Stress Coping Questionnaire (SCQ) by Sandín and Chorot (2003) consists of 42 statements in the past tense, using a Likert-type format (0 = Never and 4 = Almost always) for recording responses. The questionnaire is organized into seven subscales: (1) Social Support Seeking (SSS, items 6, 13, 20, 27, 34, 41), (2) Open emotional expression (OEE, items 4, 11, 18, 25, 32, 39), (3) Religion (RLG, items 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42), (4) Problem-solving focus (PSF, items 1, 8, 15, 22, 29, 36), (5) Avoidance (AVO, items 5, 12, 19, 26, 33, 40), (6) Negative self-focusing (NSF, items 2, 9, 16, 23, 30, 37) and (7) Positive reappraisal (PR, items 3, 10, 17, 24, 31, 38). The test is corrected by adding the values of each item, according to the subscales. In the work of Sandín and Chorot (2003), the following Cronbach's α coefficients were obtained: SSS .92, OEE .74, RLG .86, PSF .85, AVO .76, NSF .64, and PR .71. The McDonald's Omega coefficients with the present sample were: SSS .88, OEE .75, RLG .86, PSF .82, AVO .75, NSF .61, and PR .70.

The Revised Event Impact Scale (EIE-R) presented by Weiss and Marmar (1997) and validated by Báguena et al. (2001) in young Spanish adults, which is based on the Event Impact Scale (EIE) by Horowitz et al. (1979). The scale consists of 22 items, which measure Intrusion (items 1, 2, 3, 6, 9, 16, 20), Avoidance (items 5, 7, 8, 11, 12, 13, 17, 22), and Hyperarousal (items 4, 10, 14, 15, 18, 19, 21), with a Likert-type scale that assesses the intensity of symptoms from 0 (Not at all) to 4 (Extremely). Reliability was determined using internal consistency coefficients, with Cronbach’s alpha coefficient of .87 for the avoidance factor, .95 for the intrusion factor, the hyperarousal factor, and for the total scale. The EIE-R has shown convergent validity by associating with indicators of anxiety, depression, and negative affectivity. In the present study, McDonald's Omega coefficients were .96 for the total scale, .92 for intrusion, .88 for avoidance, and .91 for hyperarousal.

The Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) by Zimet et al. (1988), is a 12-item self-report instrument consisting of three subscales: Family (items 3, 4, 8, 11), Friends (items 1, 2, 5, 10), and Significant Others (items 6, 7, 9, 12). Responses are recorded on a Likert scale where 1 means strongly disagree and 7 strongly agree. The higher the sum of the scores, the greater the perceived social support. This study used the version adapted into Spanish by Landeta and Calvete (2002), which reported a Cronbach's α of .90 for Significant Others, .96 for Family, and .96 for Friends. In addition, Cronbach's alpha coefficient for the total scale was .89, indicating good internal consistency. The MSPSS has shown significant correlations with psychological well-being and self-esteem, as well as negative associations with depressive and anxiety symptoms, supporting its convergent validity in clinical and non-clinical contexts. In the present study, the McDonald's Omega coefficients found in this study were .95 for family, .94 for friends, .96 for significant others, and .96 for the total scale.

Procedure