Ciencias Psicológicas; v19(2)

July-December 2025

10.22235/cp.v19i2.4488

Original Articles

Fathers’ engagement in parenting programs: A systematic review study

Participación paterna en programas de parentalidad: un estudio de revisión sistemática

Engajamento paterno em programas de parentalidade: um estudo de revisão sistemática

Henrique Lima Reis1, ORCID 0000-0001-7591-2010

Maria Beatriz Martins Linhares2, ORCID 0000-0001-5958-9874

Mauro Luis Vieira3, ORCID 0000-0003-0541-4133

1 Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Brazil, [email protected]

2 Universidade de São Paulo, Brazil

3 Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Brazil

Abstract:

Given the importance of parenting in child development, evidence highlights the effectiveness of parental guidance interventions in promoting healthy family interactions and reducing behavioral problems in children. Despite the benefits, a significant challenge remains in ensuring paternal involvement in these programs. Following PRISMA guidelines, the present study systematically reviewed 11 empirical studies that investigated paternal involvement and participation in parenting intervention programs, focusing on facilitators and barriers to adherence. The results indicated that fathers' participation in parenting programs was positively associated with educational level, household income, and children's emotional problems. The studies also emphasize flexibility in program implementation, father-focused interventions, and the importance of recognizing fathers' caregiving roles. Social support, cultural sensitivity, and personalized approaches are highlighted as key aspects to enhance participation. Barriers such as work conflicts, social stigmas, and gender norms remain significant, requiring culturally adapted solutions. These findings provide a comprehensive overview and discuss best practices to promote greater paternal engagement, as well as barriers that may hinder fathers' participation in parenting programs.

Keywords: parenting intervention; engagement; involvement; fathers.

Resumen:

Dada la importancia de la parentalidad en el desarrollo infantil, la evidencia destaca la eficacia de las intervenciones de orientación parental en la promoción de interacciones familiares saludables y la reducción de problemas de conducta en niños. A pesar de los beneficios, sigue siendo un desafío garantizar la participación paterna en estos programas. Siguiendo las directrices PRISMA, este estudio revisó 11 estudios empíricos sobre la implicación y participación paterna en programas de intervención parental, centrándose en facilitadores y barreras para la adhesión. Los resultados indicaron que la participación paterna se asoció positivamente con el nivel educativo, los ingresos familiares y los problemas emocionales de los niños. Los estudios también enfatizan la flexibilidad en la implementación, las intervenciones centradas en los padres y la importancia del reconocimiento del rol paterno en el cuidado infantil. El apoyo social, la sensibilidad cultural y los enfoques personalizados son claves para aumentar la participación. Sin embargo, barreras como conflictos laborales, estigmas sociales y normas de género requieren soluciones culturalmente adaptadas. Estos hallazgos ofrecen una visión integral y discuten prácticas para fomentar la participación paterna en programas de parentalidad.

Palabras clave: intervención parental; participación; implicación; padres.

Resumo:

Dada a importância da parentalidade no desenvolvimento infantil, as evidências destacam a eficácia das intervenções de orientação parental na promoção de interações familiares saudáveis e na redução de problemas comportamentais em crianças. Apesar dos benefícios, um desafio significativo persiste na garantia do envolvimento paterno nesses programas. Seguindo as diretrizes PRISMA, o presente estudo revisou sistematicamente 11 estudos empíricos que investigaram o envolvimento e a participação paterna em programas de intervenção parental, com foco nos facilitadores e nas barreiras à adesão. Os resultados indicaram que a participação dos pais em programas parentais estava positivamente associada ao nível educacional, à renda familiar e aos problemas emocionais das crianças. Os estudos também enfatizam a flexibilidade na implementação dos programas, intervenções direcionadas aos pais e a importância do reconhecimento do papel paterno no cuidado infantil. Apoio social, sensibilidade cultural e abordagens personalizadas são destacados como aspectos-chave para aumentar a participação. Barreiras como conflitos laborais, estigmas sociais e normas de gênero permanecem significativas, exigindo soluções culturalmente adaptadas. Esses achados fornecem uma visão abrangente e discutem as melhores práticas para promover maior engajamento paterno, além das barreiras que podem dificultar a participação dos pais em programas de parentalidade.

Palavras-chave: intervenção parental; engajamento; envolvimento; pais.

Received: 19/02/2025

Accepted: 30/09/2025

The family is the primary environment in which individuals grow up and socialize, functioning as an essential microsystem for their survival and development (Hyde et al., 2020). Within this dynamic, the relationship between parents and children can function either as a protective or a risk factor, depending on its quality and dynamics (Bornstein, 2019). Empirical and review studies indicate that secure and stable attachment bonds (Jones et al., 2015; Madsen et al., 2024; Reis et al., 2024), monitoring and supervision practices (Rodríguez-Meirinhos et al., 2020), co-parenting, and family cohesion are essential components of healthy child development (Campbell, 2022). Likewise, positive parenting practices (e.g., warmth, emotional support, and responsiveness) have consistently been associated with beneficial outcomes, including reduced emotion dysregulation (Goagoses et al., 2022), improved academic performance (Wilder, 2023), fewer internalizing difficulties (Manuele et al., 2023), and enhanced executive functioning (Valcan et al., 2018).

In contrast, when parent–child interactions are marked by conflict, discouragement (Negrini, 2020), coercive practices (Pinquart, 2017), lack of support for autonomy (Salmin et al., 2021), or limited affection and involvement (Diniz et al., 2021), the likelihood of adverse developmental and behavioral outcomes increases (Voyer-Perron et al., 2024). For example, dysfunctional parenting styles, characterized by harshness, psychological control, or authoritarian, permissive, and neglectful behaviors, are associated with externalizing problems (Pinquart, 2017), heightened emotion dysregulation (Goagoses et al., 2022), lower self-esteem, and more depressive symptoms (Tehrani et al., 2025). Other recent review studies indicate that parental rejection and insecure parent–child attachment are associated with greater reactivity, increased emotional avoidance, and a reduced repertoire of adaptive emotion regulation strategies in children (Obeldobel et al., 2023; Wagner et al., 2025).

Given the significant impact of parenting on children’s developmental trajectories, there is growing scientific evidence on strategies and mechanisms aimed at promoting healthy and affectionate interactions among family members (Lara et al., 2024; Weisenmuller & Hilton, 2021). In this context, parental guidance interventions have emerged as important tools to foster healthier parenting practices, thereby reducing potential behavioral problems (Piotrowska et al., 2017). However, a key challenge lies in engaging and retaining fathers throughout the parenting intervention process (Brown et al., 2024).

Review studies have highlighted the positive effects of increased father involvement in child development, including higher academic performance, lower rates of behavioral and cognitive problems (Diniz et al., 2023; Reis et al., 2025), improved cognitive functioning, enhanced prosocial behavior (Henry et al., 2020; Rollè et al., 2019) and emotion regulation (Puglisi et al., 2024). Involving fathers in parental guidance offers several benefits, such as an increased likelihood of improving the co-parenting relationship (e.g., greater parental support and reduced conflicts) and indirectly enhancing individual parenting practices (Lechowicz et al., 2019).

The participation of both parents in parenting programs provides insight into the dynamics of the marital relationship, which can influence family functioning through conflict resolution strategies (Gonzalez et al., 2023). It also enables a better understanding of individual concerns and challenges. A meta-analytic review indicated that, when comparing groups consisting only of mothers to those including fathers, the latter showed a greater impact on parenting practices and children’s behaviors (Lundahl et al., 2008). Furthermore, other review studies have demonstrated positive outcomes associated with increased paternal involvement in parenting programs, such as greater responsiveness, improved co-parenting relationships, and enhanced emotional regulation and social skills in children (De Santis et al., 2020; Henry et al., 2020).

However, few studies have specifically addressed the particularities of paternal engagement in interventions (e.g., factors that promote or inhibit participation and the consistency of fathers’ involvement) and often do not assess differences between fathers and mothers (Jeong et al., 2023). A systematic review analyzing the levels of fathers’ involvement in intervention programs and strategies to enhance their engagement found that 65 % of the studies did not employ such strategies, and 58 % did not report fathers’ levels of involvement (Gonzalez et al., 2023). Another meta-analytic review evaluating the impact of the Triple P–Positive Parenting Program on parenting practices among fathers and mothers revealed that, among the 4,959 participants included, only 20 % were fathers (Fletcher et al., 2011). Thus, despite evidence supporting the greater effectiveness of interventions when both parents are involved, and the critical role of fathers in children’s development, their participation in these studies remains markedly low (Lechowicz et al., 2019).

One factor that can hinder paternal engagement in interventions is the beliefs held by professional teams, who may perceive fathers as less prepared than mothers to care for their children (Klein et al., 2022; Panter-Brick et al., 2014). This perception can undermine fathers’ self-efficacy and, consequently, their participation in interventions. Additional barriers include difficulties in balancing work responsibilities, differing perceptions of children’s problems compared to mothers, and a culturally ingrained lower likelihood of seeking health services or specialized help (Gonzalez et al., 2023; Klein et al., 2022). A recent review suggested that part of fathers’ resistance to engaging in interventions stems from a lack of familiarity with programs designed specifically for men (Hennigar et al., 2023). This resistance may be related to the historical focus of parenting interventions on mothers, as well as fears of having their parenting judged or their needs overlooked (Gonzalez et al., 2023; Hennigar et al., 2023).

Addressing topics of interest to fathers, adapting interventions to modalities beyond traditional clinical settings (e.g., online platforms, home visits), recognizing paternal competence, and emphasizing the importance of their participation in training programs and their children’s lives can help increase engagement (Gonzalez et al., 2023; Lechowicz et al., 2019; Sawrikar et al., 2023). Further recommendations to strengthen paternal engagement include reinforcing the father’s role in child development as a central figure beyond financial support, encouraging participants to share their experiences and feelings about fatherhood, and promoting the inclusion of men in professional teams, as identification with male professionals may foster greater engagement (Hennigar et al., 2023). In addition, cross-cultural research highlights the need for culturally sensitive adaptations that account for socioeconomic conditions, traditions, and the social meanings of parenting practices and gender roles (Lansford et al., 2022; Schilling et al., 2021). In particular, fathers, especially those from ethnic minority and low-income backgrounds, remain underrepresented in parenting programs (Cabrera, 2022).

Thus, promoting paternal involvement in parenting programs is crucial, given that the primary focus of these programs remains on mothers. The specificities of fathers’ participation must be considered, and training must be adapted to align with their realities and preferences. However, there is a notable gap in the literature evaluating these factors. In this context, the present study aimed to systematically review the literature to identify and critically analyze empirical studies examining paternal involvement and engagement in parenting intervention programs, with a focus on factors that facilitate or hinder their participation. Based on this analysis, we seek to provide a comprehensive overview and to discuss best practices for promoting greater paternal engagement and, consequently, enhancing the positive outcomes of parenting programs on child development.

Method

Search, databases, and keywords

The review followed the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) methodology (Page et al., 2020). The studies were searched in the PubMed, Web of Science, PsycINFO, Scopus, ERIC, Scielo, and LILACS databases. Keywords for the search were defined after reading previous articles related to the subject of this review and were used in English, Spanish, and Portuguese: ('father' OR 'male caregivers') AND ('program for fathers' OR 'parental intervention program') AND ('recruitment' OR 'retention' OR 'engagement' OR 'attendance' OR 'participation'). The first two authors searched independently, and the results were reviewed together afterward. The search was performed in February 2024, covering the past 10 years.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The following inclusion criteria were adopted for the review study: (1) empirical studies that specifically evaluated the involvement/engagement of fathers in parenting programs for parents of children up to 18 years of age, (2) studies that included structured parenting intervention programs, (3) studies published in English, Portuguese or Spanish language, based on the authors' language proficiency, (4) studies employing quantitative and qualitative methodologies. The exclusion criteria, in turn, were as follows: (1) studies that included only mothers, (2) studies in which the involvement and engagement in the parenting programs were not evaluated during or after participation, (3) theoretical or review studies, (4) books and book chapters.

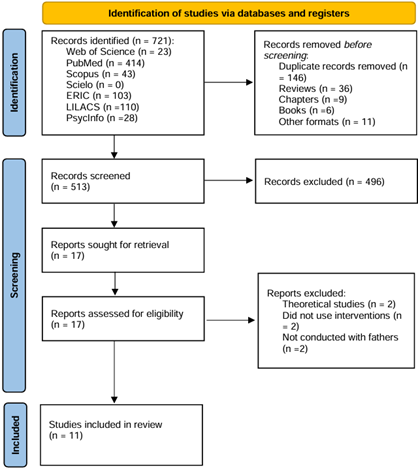

Selection of studies

Rayyan software (Ouzzani et al., 2016) was used as a technological tool to remove duplicate articles across different databases and analyze titles and abstracts. After this preliminary screening, the articles were read in full, and both the first and second authors participated in the final decision regarding inclusion and exclusion based on this reading. Figure 1 shows a flowchart of the studies identified and selected according to the PRISMA guidelines.

Figure 1: PRISMA flow diagram of the search and selection process

Data extraction and categorization

All the articles included in the review were organized in an online spreadsheet, thoroughly read, and analyzed independently by the first two authors. The analysis was based on several categories, including the following data: reference, study sample, instruments and measures of involvement/engagement, characteristics of parenting programs, data analysis, results, recommendations for paternal engagement, barriers to paternal engagement, conclusions, and limitations. The third author reviewed the data after the data extraction and organization.

Results

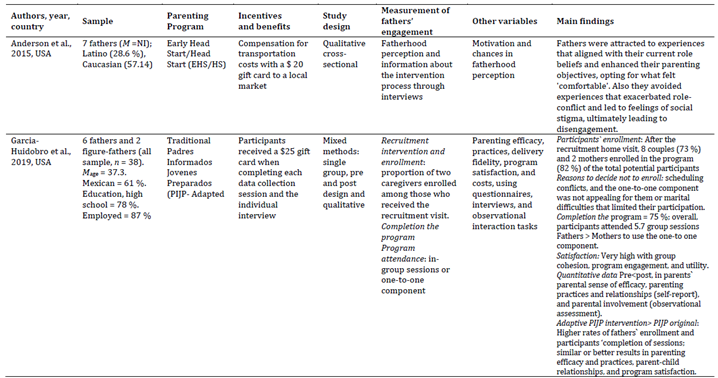

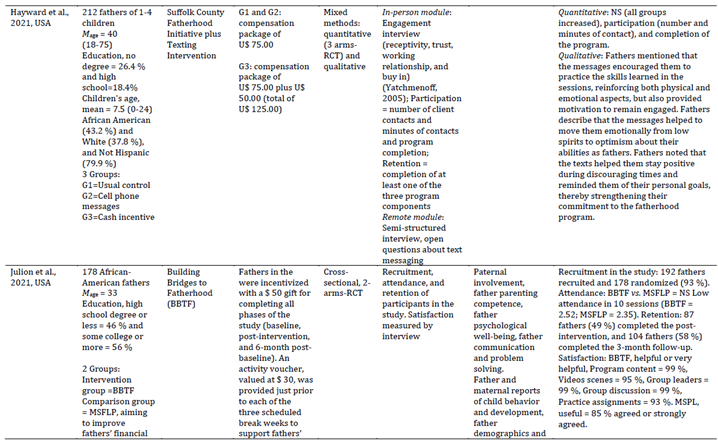

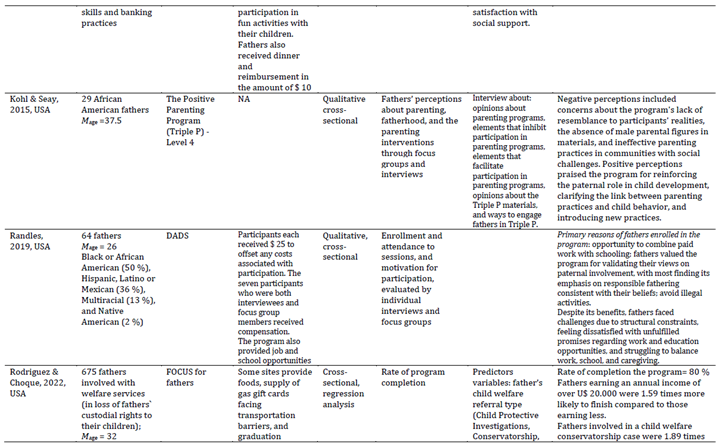

Overview of the studies

The studies reviewed were conducted in three countries. Of the 11 studies, eight were carried out in the United States (73 %), two in Australia (19 %), and one in Sweden (8 %). Sample sizes ranged from 6 to 906 fathers (M = 201.20), with an average age of 33.91 years. The study with the largest sample was conducted by Tully et al. (2019) in Australia, while the smallest was by Garcia-Huidobro et al. (2019) in the United States. Regarding participant characteristics, five studies targeted populations with specific profiles: low-income fathers (Hayward et al., 2020), Latino families (Garcia-Huidobro et al., 2019), African American fathers (Kohl & Seay, 2015), individuals experiencing social vulnerability (Anderson et al., 2015; Rostad et al., 2017), and those referred by judicial programs (Rodriguez & Choque, 2022). In the remaining studies, no participation restrictions were applied. Concerning incentives and compensation, six of the 11 studies offered transportation or meal vouchers ranging from $ 25 to $ 50 (Anderson et al., 2015; Garcia-Huidobro et al., 2019; Hayward et al., 2020; Julion et al., 2021; Randles, 2020; Seymour et al., 2021).

Study designs

Regarding study designs, four studies used quantitative data analysis, four used qualitative analysis, and three employed mixed methods in which fathers’ engagement was examined exclusively in the qualitative component. In the quantitative studies, factors related to fathers’ participation in parenting programs, as well as recruitment and retention rates, were investigated through cross-sectional designs (Rodriguez & Choque, 2022; Tully et al., 2019; Wells et al., 2016) and a two-arm randomized controlled trial (Julion et al., 2021). In the qualitative studies, paternal engagement in parenting programs was assessed through semi-structured interviews (Anderson et al., 2015; Garcia-Huidobro et al., 2019; Rostad et al., 2017; Seymour et al., 2021), focus groups (Kohl & Seay, 2015; Randles, 2020), and online questionnaires (Hayward et al., 2020).

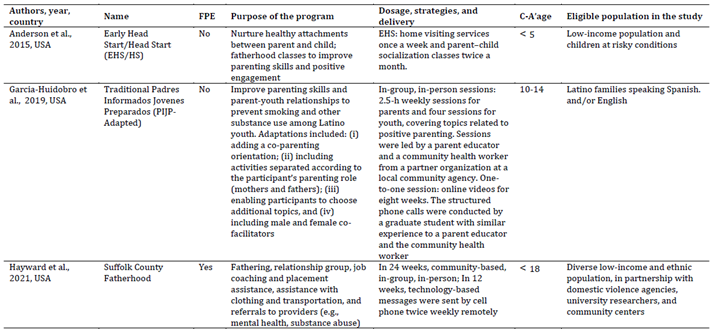

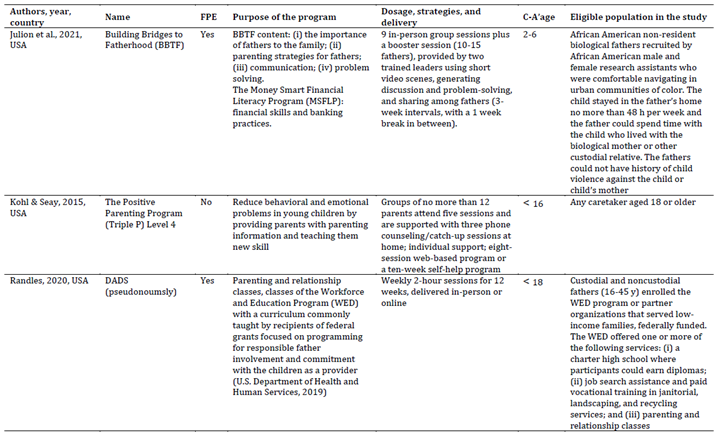

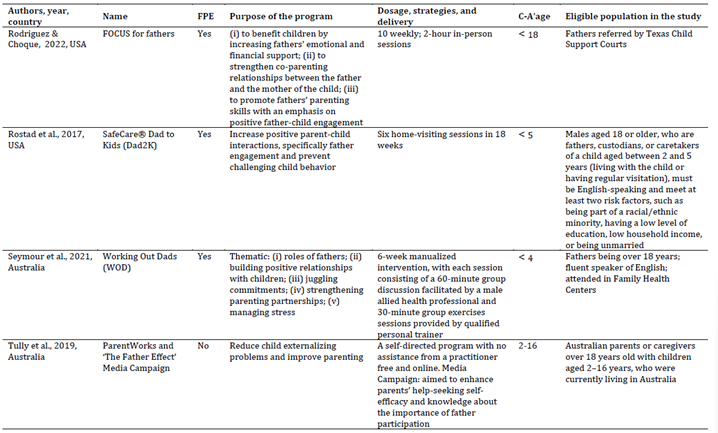

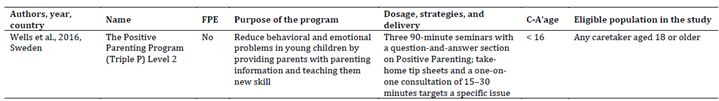

Intervention parenting programs

Table 1 presents the characteristics of the programs delivered for fathers in the studies. Concerning the parenting interventions, we detected nine different parenting programs (Table 1), as follows: Suffolk County Fatherhood Initiative (SCFI), Padres Informados Jovenes Preparados (PIJP), Positive Parenting Program (Triple P), ParentWorks, SafeCare® Dad to Kids (Dad2K), Early Head Start/Head Start (EHS/HS), FOCUS for fathers, Building Bridges to Fatherhood (BBTF), DADS, and Working Out Dads (WOD). Only the Triple P was used in two studies (Kohl & Seay, 2015; Wells et al., 2016). Of those nine programs, exclusively six of them were customized exclusively for fathers, as the following: SCFI (Hayward et al., 2020), FOCUS for fathers (Rodriguez & Choque, 2022), WOD (Seymour et al., 2021), BBTF (Julion et al., 2021), DADS (Randles, 2020), and Dad2K (Rostad et al., 2017).

Main findings of the studies

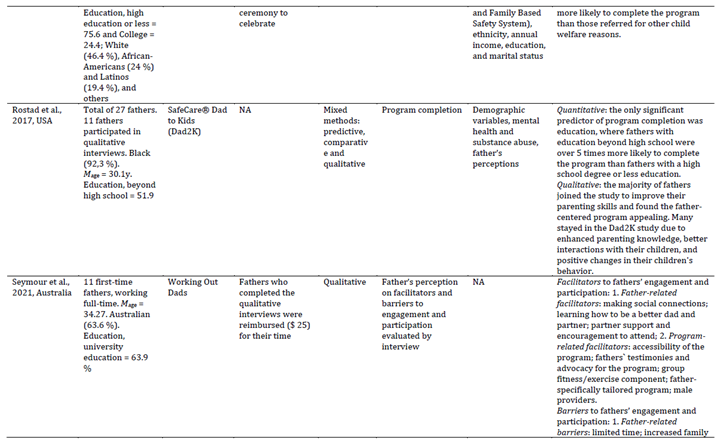

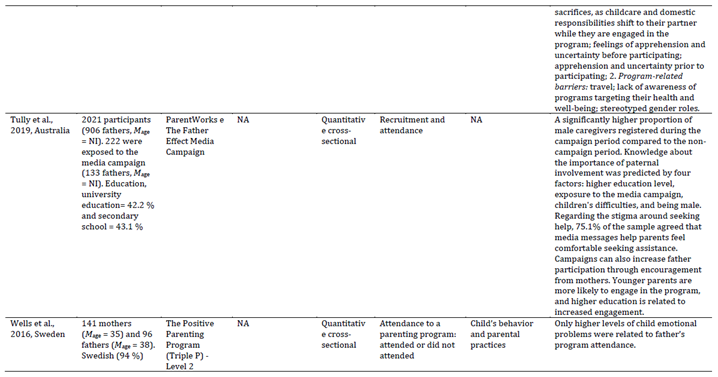

The main findings regarding involvement and engagement were organized into the following three categories: (1) factors associated with fathers' engagement, (2) evaluation of adaptations focused on fathers' engagement, and (3) fathers' perceptions of engagement and interest in parenting programs. Table 2 presents a summary of the main findings of the studies.

Table 1: Characteristics of the programs delivered for fathers in the studies

Note: FPE: Fatherhood program exclusively; C-A’age: Children and adolescent’s age.

Table 2: Overview of the studies: Methodological aspects and main finding

Factors associated with fathers' engagement

Three studies investigated variables associated with paternal engagement in the following parenting intervention programs: Dad2K (Rostad et al., 2017), Triple P – Level 2 (Wells et al., 2016), and FOCUS for Fathers (Rodriguez & Choque, 2022). Factors influencing the completion of a child maltreatment prevention program developed for male caregivers were examined, showing that fathers’ education level was the only significant predictor of program completion (Rostad et al., 2017). Fathers with education beyond high school were more than five times as likely to complete the program as those with a high school degree or less. The qualitative analysis revealed that, when asked about their motivations to participate in the intervention, most fathers expressed a desire either to enhance their existing parenting practices or to acquire new ones. They also found participation in a father-focused parenting program particularly appealing. Regarding the factors that encouraged fathers to remain engaged in the program, many cited the expansion of their parenting knowledge, improved interactions with their children, and observed positive changes in their children’s behavior as key reasons for continued participation.

Additionally, family income was a significant predictor of fathers’ successful completion of a parenting program (Rodriguez & Choque, 2022). Fathers earning over $ 20,000 per year were 1.59 times more likely to complete the program than those with lower incomes. Having a child welfare conservatorship case also predicted program completion, with fathers in such cases being 1.89 times more likely to complete the program than fathers with other types of child welfare referrals. In these instances, participation in intervention programs was court-mandated, and engagement was therefore expected to be higher.

When comparing fathers’ and mothers’ attendance in a parenting program, fathers were less likely than mothers to participate (Wells et al., 2016). No demographic variables were associated with fathers’ attendance; however, their perception of higher levels of child emotional problems was linked to greater engagement. In summary, the main factors associated with fathers’ engagement in parenting programs reflect both individual and contextual characteristics, including educational level, household income, conservatorship cases in child welfare systems, and elevated levels of children’s emotional problems.

Assessment of adaptations focusing on father's engagement

Four studies examined the effectiveness of adjustments made to parenting intervention programs aimed at enhancing paternal involvement. Hayward et al. (2020) evaluated the implementation of text messaging to improve engagement, participation, and retention throughout the Suffolk County Fatherhood program. A key finding was that participants reported text messages reinforced the skills learned during the sessions. Specific messages encouraged displays of affection toward their children and recognition of their accomplishments. Moreover, fathers emphasized that these messages helped them manage emotions during interactions with their children, thereby reinforcing both the physical and emotional aspects taught in the program. Interviews also revealed that the text messages served as a motivating factor for participants to remain committed to their roles as fathers. Fathers shared that these messages boosted their spirits during challenging times and provided additional emotional support beyond in-person program attendance.

In the study by Garcia-Huidobro et al. (2019), home visits were conducted during the recruitment process to provide information about the program directly to both caregivers, allowing them to experience how it worked and to build a relationship with the program team. This effort aimed to enhance paternal engagement in the program. Other adaptations to the intervention included the addition of individual sessions, co-parenting guidance, separate activities tailored to the participant’s parenting role, opportunities to choose additional topics, and the inclusion of both male and female facilitators. Satisfaction was high regarding both the recruitment process and the modifications implemented. Individualized components, such as videos and telephone communication, also received positive feedback, with fathers showing greater engagement with these strategies. Adaptations such as home visits allowed fathers to recognize the program’s benefits from the comfort of their homes—a crucial consideration given that mothers are typically the ones who seek such services. Moreover, individual follow-ups via messages or phone calls enhanced father involvement by fostering a sense of belonging and significance within the program.

The study of Tully et al. (2019) investigated the recruitment of male caregivers, evaluating the effectiveness of a media campaign designed to increase fathers’ participation in an online parenting program (ParentWorks). During the campaign period, enrollment of fathers in the program was four times higher compared to periods without the campaign. However, when analyzing predictors across the entire sample (mothers and fathers), being male significantly predicted higher adherence to the parenting program, alongside higher education level, exposure to the media campaign, and perception of children’s difficulties as severe. Notably, 44 % of those seeking intervention were men, indicating promising potential for greater paternal engagement in parenting programs. Media campaigns may also indirectly enhance father involvement by motivating their partners, particularly mothers. Additionally, younger parents and those with younger children demonstrated higher levels of engagement with the program.

Finally, the study of Julion et al. (2021) did not find significant results when comparing the Dedicated African American Dad program and the Money Smart Financial Literacy Program regarding father involvement in a fatherhood intervention. Attendance among fathers was notably low in both groups. In the Building Bridges to Fatherhood (BBTF) group, average attendance was 2.52 sessions (SD = 3.43), while the Money Smart Financial Literacy Program (MSFLP) group had an average of 2.35 sessions (SD = 3.16). Most participants in both groups attended no sessions, with 57.6 % in the BBTF group and 51.2 % in the MSFLP group reporting zero attendance. No significant differences in attendance rates were observed between the two groups. These findings highlight the need for socio-cultural adjustments and adaptations to effectively engage fathers, including program flexibility and alignment of program content with participants’ needs.

In summary, adaptations aimed at enhancing fathers’ engagement in parenting programs were most successful when individualized components, such as videos, telephone communication, and media campaigns, were incorporated into the recruitment process.

Fathers’ perceptions regarding engagement and interest in parenting programs

Four studies, through interviews, evaluated fathers’ perceptions of engagement and interest in parenting programs. Randles (2020) investigated how fathers’ perceptions of fatherhood influenced their engagement in the parenting guidance program (DADS). Notably, in addition to parenting training, the program offered courses and educational opportunities for fathers, as well as assistance with job searching and professional development, enabling participants to improve their financial conditions. As a result, most fathers identified these factors as the main reasons for their participation and engagement in the program. Another aspect mentioned was the validation provided by professionals, who acknowledged fathers’ efforts and positive behaviors in fatherhood. The program reinforced the importance of both financial and emotional support, helping fathers redefine their roles to include presence and care. Fathers valued the program’s ability to provide stable employment, social support, and practical resources, all of which were essential for sustaining their involvement with their children. These findings highlight the importance of comprehensive support for fathers, particularly those facing socioeconomic challenges, to help them fulfill their roles as responsible and engaged parents.

Seymour et al. (2021) identified two overarching themes associated with factors facilitating fathers’ engagement in the parental program Working Out Dads (WOD): father-related and program-related factors. In the father-related category, making social connections with other fathers experiencing similar challenges was highlighted. Additionally, some fathers reported a desire to learn more about child development and parenting skills, including emotional regulation, which helped them better manage family relationships. Partner support and encouragement for attending the intervention also emerged as an important factor. In the program-related category, fathers emphasized that flexibility and accessibility, such as sessions outside business hours, convenient locations, and consistent schedules, facilitated their participation. Having another father as a facilitator enhanced their sense of connection, making them feel understood and not judged. The active participation of fathers in proposing discussion topics was also frequently mentioned, as it made them feel welcomed. Furthermore, the exclusive focus on male parents reduced the fear of being the only father present, which is common in mixed parenting programs. Lastly, including a component dedicated to fathers’ physical health contributed to maintaining their mental health beyond fatherhood.

Anderson et al. (2015) investigated the impact of fathers’ experiences within an intervention on the development of the paternal role and their involvement in the Early Head Start/Head Start (EHS/HS) program. The interviews underscored the importance of the intervention team considering the individual goals of fathers, including challenges faced in specific aspects of fatherhood. Another notable factor was the professional’s rapport with the partner and child, as a positive relationship contributed to the father’s comfort with the intervention. Additionally, providing access to supplementary health services through the program was identified as a crucial element in enhancing paternal engagement.

In addition to these findings, Kohl and Seay (2015) explored the perspectives of African American fathers regarding a parenting program, identifying two main categories in the focus groups: negative and positive perceptions. On the negative side, participants pointed to a perceived disconnect between program content and real-life experiences, insufficient representation of fathers in program materials, and doubts about the effectiveness of certain parenting practices in communities with higher crime rates or social inequality. However, fathers in the intervention group expressed less negative feedback, underscoring the importance of parental mental well-being for positive parenting outcomes. On the positive side, fathers noted that the program emphasized the significance of the paternal role in child development, the relationship between parenting approaches and child behavior, and the exploration of innovative parenting strategies. Importantly, parents who did not engage in the intervention expressed more negative feedback, suggesting that unfavorable perceptions may influence future decisions to seek support.

In summary, fathers reported that parenting programs offered opportunities to learn about child development, parenting and emotional regulation skills, and to engage in social interaction with other fathers. They also valued the programs’ ability to complement stable employment, social support, practical resources, and attention to both physical and mental health beyond fatherhood.

Discussion

The present review showed that effective strategies to engage fathers in parenting programs encompass a variety of approaches and modalities aimed at increasing their active participation in interventions. It is important to note that procedures to enhance paternal engagement in intervention programs must account for the fact that fathers experience parenthood differently from mothers, due to both socially constructed aspects and biological influences (Tiano & McNeil, 2008). In the current review, the most frequently mentioned strategies were as follows: flexibility in program modality and recruitment (Garcia-Huidobro et al., 2019; Julion et al., 2021; Rostad et al., 2017; Seymour et al., 2021; Tully et al., 2019), exclusive interventions focused on fathers (Rodriguez & Choque, 2022; Rostad et al., 2017; Seymour et al., 2021; Wells et al., 2016), a positive relationship and identification with the intervention team (Anderson et al., 2015; Julion et al., 2021; Rodriguez & Choque, 2022; Wells et al., 2016), appreciation of fathers’ views and their socioeconomic and cultural realities (Anderson et al., 2015; Hayward et al., 2020; Kohl & Seay, 2015; Randles, 2020), and recognition of their efforts as parents and their role in the child’s life (Hayward et al., 2020; Kohl & Seay, 2015; Rodriguez & Choque, 2022).

In line with these studies, Brown et al. (2024) evaluated aspects of a fatherhood intervention program, emphasizing the importance of social support in increasing fathers’ engagement. Support from staff who value fatherhood, identification with other participants, and recognition of fathers as caregivers (and not only financial providers) are important aspects to consider in such programs. Engagement can encompass several stages of the parenting training process, including recruitment, retention, frequency, and level of participation (Piotrowska et al., 2017). In this regard, Tully et al. (2019) underscored the importance of disseminating information about fatherhood programs, emphasizing the role of fathers in child development, and utilizing figures with whom fathers can identify, since many report being unaware of the existence of such programs.

An important aspect to consider is the cultural and social appropriateness of parenting interventions, underscoring the need for culturally sensitive approaches that align with participants’ social contexts in order to avoid alienating fathers. Tailored advertisements and facilitators who share characteristics with the target audience can also improve engagement, once successful implementation requires not only fidelity to core components but also sensitivity to local realities (Kohl & Seay, 2015; Randles, 2020; Salari & Filus, 2017; Seymour et al., 2021; Wells et al., 2016). Although this need is well documented in the literature, recent review studies indicate that most cultural adaptations remain superficial, often restricted to translation and staffing (Lansford et al., 2022; Schilling et al., 2021). In fact, the same parenting practice can assume different meanings and functions depending on cultural scripts, underscoring the importance of contextually grounded interpretations (Lansford, 2022). Cabrera (2022) emphasizes that fathers, particularly those from ethnic minority and low-income backgrounds, remain largely overlooked in cross-cultural research.

The difficulty in engaging parents is also linked to socioeconomic conditions such as racism, inequality, and poverty (Julion et al., 2021; Piotrowska et al., 2017). Within this reality, parents are often required to dedicate more time to seeking and maintaining employment and other sources of income than to participating in parental interventions. Furthermore, implementation science points out that transferring evidence-based programs without adapting them to local systems, workforce capacity, and community involvement frequently undermines effectiveness, particularly in low- and middle-income countries (Lansford et al., 2022). Therefore, training programs must be both culturally sensitive and faithful to the original design to ensure that their effectiveness is not undermined (Pfitzner et al., 2020).

It is worth noting that flexibility in scheduling and formats (e.g., online modalities) is essential, as balancing work responsibilities and travel costs can hinder participation. Implementing diverse formats, such as home visits, group sessions, one-on-one sessions, online sessions, and short-term interventions, may result in higher engagement and satisfaction rates, along with noticeable positive changes in parenting. Home visits, for example, can help fathers better understand the program, promote engagement through personalized interactions, and motivate them to participate actively (Garcia-Huidobro et al., 2019; Rodriguez & Choque, 2022; Rostad et al., 2017). Furthermore, “proxy interactions” between program facilitators and parents are also crucial, and motivational interviews with enrolled participants can reduce the risk of dropout. Despite recruitment and engagement efforts (e.g., outreach and financial assistance), lack of awareness about the program and limited social support may still hinder participation (Gonzalez et al., 2023; Klein et al., 2022).

Interventions focused exclusively on fathers can increase engagement by reducing fears of judgment often associated with joint sessions involving mothers (Rostad et al., 2017). The presence of other fathers who share similar experiences can foster a sense of belonging and, consequently, greater engagement in parenting programs (Lechowicz et al., 2019; Sawrikar et al., 2023). This also involves consideration of fathers’ wishes, desires, and anxieties. Participants should feel important and valued, underscoring the relevance of addressing themes that promote inclusion and demonstrate attentiveness to parental concerns (Hayward et al., 2020).

In a recent study, Novianti et al. (2023) points out that cultural expectations often assign fathers a more peripheral role in daily caregiving, concentrating their responsibilities on financial provision. Such gendered norms may limit paternal engagement in parenting programs unless interventions explicitly address the cultural scripts that shape fatherhood. The father’s active role in child development should therefore be emphasized beyond financial support, highlighting his role as a figure of care and attachment, which reinforces parental self-efficacy and values fatherhood in its entirety (Hennigar et al., 2023; Kohl & Seay, 2015). In this context, interventions may also address co-parenting, emotional regulation strategies, and challenges experienced during parenthood (De Santis et al., 2020; Henry et al., 2020; Randles, 2020).

Therefore, some aspects may hinder paternal engagement in parenting interventions. Anderson et al. (2015), and Seymour et al. (2021) reported difficulties in reconciling program schedules with fathers’ work commitments, noting that weekends were often the only time available to spend with their children, which fathers preferred over attending training sessions. A further limitation is the lack of clarity about program content, which raises questions regarding the relevance of these practices. Additional barriers include travel distance to intervention sites and rigid gender norms that perpetuate the idea that such programs are intended only for mothers (Gonzalez et al., 2023). Reinforcing these aspects, Klein et al. (2022) and Panter-Brick et al. (2014) emphasized that program staff themselves may reinforce stereotypes, perceiving fathers as less prepared for caregiving than mothers, which undermines paternal self-efficacy and reduces their likelihood of engaging in the process.

Financial constraints associated with travel to program sites may be particularly problematic in socially vulnerable populations. Social stigma, including fear of judgment, adherence to masculine ideals discouraging men from seeking help, and maternal mediation, which can either encourage or discourage participation, may also hinders engagement (Hennigar et al., 2023; Tully et al., 2017). The locations where interventions are advertised are also significant, as many fathers remain unaware of their existence; targeted media campaigns and reaching fathers through mothers can help address this issue (Tully et al., 2019). Finally, overlooking fathers’ specific goals and desires, or perceiving them merely as supporting actors in parental care or as financial providers, can further reduce their participation (Gonzalez et al., 2023; Lechowicz et al., 2019; Sawrikar et al., 2023).

Conclusions and limitations

This review identified several factors that can either increase or reduce fathers’ engagement. Our results emphasize flexibility in program modality and recruitment, exclusive interventions focused on the father figure, fostering positive relationships and identification with the intervention team, valuing fathers’ perspectives and their socioeconomic and cultural realities, and recognizing their efforts as caregivers and their role in the child’s life. Furthermore, social support is crucial for increasing paternal engagement in interventions, underscoring the importance of recognizing fathers as caregivers rather than merely financial providers.

Paternal engagement in parenting programs involves different stages, such as recruitment, retention, frequency, and level of participation, as well as strategies such as disseminating information about the relevance of fathers’ roles in child development and using relatable content to increase adherence. In this context, it is important to develop studies that explore the specificities of each stage and identify barriers and facilitators that can enhance fathers’ participation in parenting intervention programs. Another fundamental point to consider is the cultural and social appropriateness of interventions. Cultural sensitivity, that is, taking participants’ social contexts into account, is essential for fathers to feel motivated to participate. Additionally, personalized invitations and facilitators who share characteristics with the target audience can improve engagement. Flexibility in intervention times and formats, such as online sessions and home visits, is also recommended to allow fathers to participate actively, particularly given challenges such as work commitments and travel costs.

Despite progress, several challenges remain in the literature. Difficulties in reconciling work and program schedules, social stigmas, and financial constraints are significant barriers to paternal participation. In addition, the lack of clarity regarding the topics covered in interventions and the perpetuation of gender norms that associate caregiving exclusively with mothers can further reduce fathers’ engagement. Overcoming these challenges requires culturally sensitive interventions that value fatherhood in its entirety, recognizing fathers as figures of care and attachment in child development. Although father-only interventions have demonstrated potential for increasing engagement, more studies are needed to evaluate how these interventions affect paternal well-being, co-parenting relationships, and child development compared to programs targeting both parents. Further research is also needed to examine the influence of gender norms and social stigmas (e.g., the ideal of masculinity that discourages men from seeking help) on paternal engagement. Such investigations could help identify strategies to dismantle these barriers across different social contexts. Maternal mediation is another factor that can either encourage or discourage fathers’ participation in intervention programs.

It is important to note some limitations of the present review, such as the restriction to English-language publications, which may have excluded studies from other countries; the reliance on literature indexed in the selected databases, which excluded gray literature; and the focus on studies published within the past 10 years. Future studies should address new questions. It is recommended that research explores in greater depth which specific adaptations are most effective in different cultural and socioeconomic contexts. This includes evaluating personalized interventions for vulnerable populations, considering race, ethnicity, and social and economic inequality. Furthermore, future research could investigate the comparative impact of different program formats (e.g., in-person, online, home visits, group sessions) on paternal engagement and child development outcomes. Another relevant avenue of research is examining how maternal support or resistance influences fathers’ decisions to participate in interventions.

Another limitation of this review is that we did not examine whether the strategies to promote fathers’ engagement in parenting programs identified in the literature were also applied to mothers, nor whether they would have the same effectiveness. Future studies should directly compare maternal and paternal engagement strategies to better understand similarities and differences in parental roles within intervention programs. Another approach would be to examine the factors that facilitate or hinder the sharing of child care by parents and/or caregivers, whether in same-sex or different-sex parent families.

The heterogeneity in children’s ages constitutes a limitation of the study, as this diversity may impact the generalizability of the findings. Different age groups often necessitate tailored strategies to effectively foster father involvement. In addition, the different expectations and challenges experienced by fathers at each developmental stage may influence the effectiveness of the programs analyzed. To advance the understanding of father engagement across developmental stages, future research should, for example, conduct age-stratified analyses to identify specific patterns of paternal involvement, examine the needs and challenges faced by fathers at different stages of child development and design programs tailored to the characteristics of each age group, thereby optimizing both father engagement and child outcomes.

A further limitation concerns the fact that, due to the diversity of samples and the small number of studies included, it was not possible to explore in depth the practical implications of successful adaptations for different profiles of fathers (e.g., young, vulnerable, or migrant fathers). Future studies should examine how tailoring interventions to these diverse profiles may enhance paternal engagement and program effectiveness. Finally, longitudinal studies are recommended to assess how parental engagement in intervention programs affects child development and the long-term co-parenting relationship, monitoring effects beyond the immediate completion of the program.

Despite the limitations discussed, the findings of this review provide valuable insights into father involvement in parenting programs. By offering a comprehensive overview of both best practices and obstacles, this study contributes to the growing but still limited literature on paternal engagement. These results invite researchers and practitioners to further explore and prioritize fathers’ involvement, ultimately fostering more inclusive and effective parenting programs.

References:

Anderson, S., Aller, T. B., Piercy, K. W., & Roggman, L. A. (2015). Helping us find our own selves: Exploring father-role construction and early childhood programme engagement. Early Child Development and Care, 185(3), 360-376. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2014.924112

Bornstein, M. H. (2019). Handbook of parenting: Being and becoming a parent (3rd ed.). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780429433214

Brown, T. L., Roy, R. N., Dayne, N., Roy, D. R., James, A. G., & Carrichi-Lopez, A. (2024). Promoting father engagement among low-income fathers: Fathers’ narratives on what matters in a fatherhood programme in the western US. Journal of Family Studies, 30(2), 214-232. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2023.2216668

Cabrera, N. J. (2022). Recognizing our similarities and celebrating our differences - parenting across cultures as a lens toward social justice and equity. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, and Allied Disciplines, 63(4), 480-483. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13600

Campbell, C. G. (2022). Two decades of coparenting research: A scoping review. Marriage & Family Review, 59(6), 379-411. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2022.2152520

De Santis, L., De Carvalho, T. R., De Lima Guerra, L. L., Dos Santos Rocha, F., & Barham, E. J. (2020). Supporting fathering: A systematic review of parenting programs that promote father involvement. Trends in Psychology, 28(2), 302-320. https://doi.org/10.9788/s43076-019-00008-z

Diniz, E., Brandão, T., & Veríssimo, M. (2023). Father involvement during early childhood: A systematic review of qualitative studies. Family Relations, 72, 2710-2730. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12858

Diniz, E., Brandão, T., Monteiro, L., & Veríssimo, M. (2021). Father involvement during early childhood: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 13(1), 77-99. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.1241

Fletcher, R., Freeman, E., & Matthey, S. (2011). The impact of behavioural parent training on fathers' parenting: A meta-analysis of the Triple P-Positive Parenting Program. Fathering: A Journal of Theory, Research, and Practice about Men as Fathers, 9(3), 291-312. https://doi.org/10.3149/fth.0903.291

Garcia-Huidobro, D., Diaspro-Higuera, M. O., Palma, D., Palma, R., Ortega, L., Shlafer, R., Wieling, E., Piehler, T., August, G., Svetaz, M. V., Borowsky, I. W., & Allen, M. L. (2019). Adaptive recruitment and parenting interventions for immigrant latino families with adolescents. Prevention Science, 20(1), 56-67. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-018-0898-1

Goagoses, N., Bolz, T., Eilts, J., Schipper, N., Schütz, J., Rademacher, A., Vesterling, C., & Koglin, U. (2022). Parenting dimensions/styles and emotion dysregulation in childhood and adolescence: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Current Psychology, 42(22), 18798-18822. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03037-7

Gonzalez, J., Klein, C., Barnett, M., Schatz, N., Garoosi, T., Chacko, A., & Fabiano, G. (2023). Intervention and implementation characteristics to enhance father engagement: A systematic review of parenting interventions. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 26(3), 445-458. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-023-00430-x

Hayward, R. A., McKillop, A. J., Lee, S. J., Hammock, A. C., Hong, H., & Hou, W. (2020). A text messaging intervention to increase engagement and retention of men in a community-based father involvement program. Journal of Technology in Human Services, 39(2), 144-162. https://doi.org/10.1080/15228835.2020.1841070

Hennigar, A., Avellar, S., Espinoza, A., & Friend, D. (2023). Serving young fathers in Responsible Fatherhood Programs (OPRE Report 2023-279). Office of Planning, Research and Evaluation, Administration for Children and Families, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.

Henry, J. B., Julion, W. A., Bounds, D. T., & Sumo, J. (2020). Fatherhood matters: An integrative review of fatherhood intervention research. The Journal of School Nursing, 36(1), 19-32. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059840519873380

Hyde, L. W., Gard, A. M., Tomlinson, R. C., Burt, S. A., Mitchell, C., & Monk, C. S. (2020). An ecological approach to understanding the developing brain: Examples linking poverty, parenting, neighborhoods, and the brain. The American Psychologist, 75(9), 1245-1259. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000741

Jeong, J., Sullivan, E. F., & McCann, J. K. (2023). Effectiveness of father-inclusive interventions on maternal, paternal, couples, and early child outcomes in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine, 328, 115971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2023.115971

Jones, J. D., Cassidy, J., & Shaver, P. R. (2015). Parents' self-reported attachment styles: A review of links with parenting behaviors, emotions, and cognitions. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 19(1), 44-76. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868314541858

Julion, W., Sumo, J., Schoeny, M. E., Breitenstein, S. M., & Bounds, D. T. (2021). Recruitment, retention, and intervention outcomes from the Dedicated African American Dad (DAAD) study. Journal of Urban Health: Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine, 98(Suppl 2), 133-148. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-021-00549-8

Klein, C. C., Gonzalez, J. C., Tremblay, M., & Barnett, M. L. (2022). Father participation in parent-child interaction therapy: Predictors and therapist perspectives. Evidence-Based Practice in Child and Adolescent Mental Health, 8(3), 393-407. https://doi.org/10.1080/23794925.2022.2051213

Kohl, P. L., & Seay, K. D. (2015). Engaging African American fathers in behavioral parent training: To adapt or not adapt. Best Practices in Mental Health, 11(1), 54-68. https://doi.org/10.70256/835667xsrolp

Lansford J. E. (2022). Annual Research Review: Cross-cultural similarities and differences in parenting. Journal of child psychology and psychiatry, and allied disciplines, 63(4), 466-479. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcpp.13539

Lansford, J. E., Betancourt, T. S., Boller, K., Popp, J., Pisani Altafim, E. R., Attanasio, O., & Raghavan, C. (2022). The future of parenting programs: II implementation. Parenting, 22(3), 235-257. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2022.2086807

Lara, M. D. V., Rubilar Valenzuela, C. P., Zicavo Martínez, N., & Pino Muñoz, M. M. (2024). A caminho de uma nova paternidade: Perspectivas sobre o papel do pai em famílias biparentais chilenas. Ciencias Psicológicas, 18(2), e-3846. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v18i2.3846

Lechowicz, M. E., Jiang, Y., Tully, L. A., Burn, M. T., Collins, D. A. J., Hawes, D. J., Lenroot, R. K., Anderson, V., Doyle, F. L., Piotrowska, P. J., Frick, P. J., Moul, C., Kimonis, E. R., & Dadds, M. R. (2019). Enhancing father engagement in parenting programs: Translating research into practice recommendations. Australian Psychologist, 54(2), 83-89. https://doi.org/10.1111/ap.12361

Lundahl, B. W., Tollefson, D., Risser, H., & Lovejoy, M. C. (2008). A meta-analysis of father involvement in parent training. Research on Social Work Practice, 18(2), 97-106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049731507309828

Madsen, E. B., Egmose, I., Stuart, A. C., Krogh, M. T., Wahl Haase, T., Karstoft, K. I., & Væver, M. S. (2024). Identifying profiles of parental reflective functioning in first-time parents and associations with parental attachment and infant socioemotional adjustment. Parenting, 24(4), 154-181. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2024.2423808

Manuele, S. J., Yap, M. B. H., Lin, S. C., Pozzi, E., & Whittle, S. (2023). Associations between paternal versus maternal parenting behaviors and child and adolescent internalizing problems: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology Review, 105(3), 102339. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2023.102339

Negrini L. S. (2020). Coparenting supports in mitigating the effects of family conflict on infant and young child development. Social Work, 65(3), 278-287. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/swaa027

Novianti, R., Suarman, & Islami, N. (2023). Parenting in cultural perspective: A systematic review of paternal role across cultures. Journal of Ethnic and Cultural Studies, 10(1), 22-44. https://doi.org/10.29333/ejecs/1287

Obeldobel, C. A., Brumariu, L. E., & Kerns, K. A. (2023). Parent–child attachment and dynamic emotion regulation: A systematic review. Emotion Review, 15(1), 28-44. https://doi.org/10.1177/17540739221136895

Ouzzani, M., Hammady, H., Fedorowicz, Z., & Elmagarmid, A. (2016). Rayyan – a web and mobile app for systematic reviews. Systematic Reviews, 5, 210. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13643-016-0384-4

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., McGuinness, L. A., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372(71). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Panter-Brick, C., Burgess, A., Eggerman, M., McAllister, F., Pruett, K., & Leckman, J. F. (2014). Practitioner review: Engaging fathers - Recommendations for a game change in parenting interventions based on a systematic review of the global evidence. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 55(11), 1187-1212. https://doi.org/10. 1111/jcpp.12280

Pfitzner, N., Humphreys, C., & Hegarty, K. (2020). Bringing men in from the margins: Father-inclusive practices for the delivery of parenting interventions. Child & Family Social Work, 25(1), 198-206. https://doi.org/10.1111/cfs.12760

Pinquart M. (2017). Associations of parenting dimensions and styles with externalizing problems of children and adolescents: An updated meta-analysis. Developmental Psychology, 53(5), 873-932. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0000295

Piotrowska, P. J., Tully, L. A., Lenroot, R., Kimonis, E., Hawes, D., Moul, C., Frick, P. J., Anderson, V., & Dadds, M. R. (2017). Mothers, Fathers, and parental systems: A conceptual model of parental engagement in programmes for Child mental health-connect, Attend, Participate, Enact (CAPE). Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 20(2), 146-161. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-016-0219-9

Puglisi, N., Rattaz, V., Favez, N., & Tissot, H. (2024). Father involvement and emotion regulation during early childhood: A systematic review. BMC psychology, 12(1), 675. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-024-02182-x

Randles, J. (2020). The means to and meaning of “Being There” in responsible fatherhood programming with low-income fathers. Family Relation, 69, 7-20. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12376

Reis, H. L., Simionatto, A. P. R., Pivato, J. A., Vieira, M. L., & de Souza, C. D. (2025). Relations between parental gatekeeping and parenting in families with children: A scoping review. Psychological Reports, 0(0). https://doi.org/10.1177/00332941251347251

Reis, L. H., Nogueira, C. K., Manfroi, E. C., & Gonçalves, P. A. (2024). Perceived parental bonding and variables associated with maternal-fetal attachment in high-risk pregnancy. Ciencias Psicológicas, 18(2), e3598. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v18i2.3598

Rodriguez, M. R., & Choque, G. A. H. (2022). Predictors associated with fathers' successful completion of the FOCUS program. Family Relations, 71(3), 1142-1158. https://doi.org/10.1111/fare.12633

Rodríguez-Meirinhos, A., Vansteenkiste, M., Soenens, B., Oliva, A., Brenning, K., & Antolín-Suárez, L. (2020). When is parental monitoring effective? A person-centered analysis of the role of autonomy-supportive and psychologically controlling parenting in referred and non-referred adolescents. Journal of Youth and Adolescence, 49, 352-368. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-019-01151-7

Rollè, L., Gullotta, G., Trombetta, T., Curti, L., Gerino, E., Brustia, P., & Caldarera, A. M. (2019). Father involvement and cognitive development in early and middle childhood: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2405. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02405

Rostad, W. L., Self-Brown, S., Boyd, C., Jr, Osborne, M., & Patterson, A. (2017). Exploration of factors predictive of at-risk fathers' participation in a pilot study of an augmented evidence-based parent training program: A mixed methods approach. Children and Youth Services Review, 79, 485-494. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2017.07.001

Salari, R., & Filus, A. (2017). Using the health belief model to explain mothers' and fathers' intention to participate in universal parenting programs. Prevention Science, 18(1), 83-94. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11121-016-0696-6

Salmin, H. A., Nasrudin, D., Sandi Hidayat, M., & Winarni, W. (2021). The effect of overprotective parental attitudes on children’s development. Jurnal BELAINDIKA (Pembelajaran Dan Inovasi Pendidikan), 3(1), 15-20. https://doi.org/10.52005/belaindika.v3i1.63

Sawrikar, V., Plant, A. L., Andrade, B., Woolgar, M., Scott, S., Gardner, E., Dean, C., Tully, L. A., Hawes, D. J., & Dadds, M. R. (2023). Global workforce development in father engagement competencies for family-based interventions using an online training program: A mixed-method feasibility study. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 54(3), 758-769. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-021-01282-8

Schilling, S., Mebane, A., & Perreira, K. M. (2021). Cultural adaptation of group parenting programs: Review of the literature and recommendations for best practices. Family Process, 60(4), 1134-1151. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12658

Seymour, M., Peace, R., Wood, C. E., Jillard, C., Evans, K., O'Brien, J., Williams, L. A., Brown, S., & Giallo, R. (2021). "We're in the background": Facilitators and barriers to fathers' engagement and participation in a health intervention during the early parenting period. Health Promotion Journal of Australia, 32(Suppl 2), 78-86. https://doi.org/10.1002/hpja.432

Tehrani, H. D., Yamini, S., & Vazsonyi, A. T. (2025). The links between parenting, self-esteem, and depressive symptoms: a meta-analysis. Journal of adolescence, 97(2), 315-332. https://doi.org/10.1002/jad.12435

Tiano, J. D., & McNeil, C. B. (2008). The inclusion of fathers in behavioral parent training: A critical evaluation. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 27(4), 1-28. https://doi.org/10.1300/j019v27n04_01

Tully, L. A., Collins, D. A. J., Piotrowska, P. J., Mairet, K. S., Hawes, D. J., Moul, C., Dadds, M. R. (2017). Examining practitioner competencies, organizational support and barriers to engaging fathers in parenting interventions. Child Psychiatry and Human Development, 49(1), 109-122. https://doi.org/10.1007/S10578-017-0733-0

Tully, L. A., Piotrowska, P. J., Collins, D. A. J., Frick, P. J., Anderson, V., Moul, C., Lenroot, R. K., Kimonis, E. R., Hawes, D., & Dadds, M. R. (2019). Evaluation of 'The Father Effect' media campaign to increase awareness of, and participation in, an online father-inclusive parenting program. Health Communication, 34(12), 1423-1432. https://doi.org/10.1080/10410236.2018.1495160

Valcan, D. S., Davis, H., & Pino-Pasternak, D. (2018). Parental behaviours predicting early childhood executive functions: a meta-analysis. Educational Psychology Review, 30(3), 607-649. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-017-9411-9

Voyer-Perron, P., Matte-Gagné, C., & Levesque, C. (2024). Factors associated with father involvement during infancy: A multifactorial and multidimensional approach. Parenting, 24(2-3), 78-105. https://doi.org/10.1080/15295192.2024.2326441

Wagner, K. N., Johnson, L. N., & Bradford, A. B. (2025). Emotion regulation in parent–child relationships: A decade (2013-2023) review. Contemporary Family Therapy: An International Journal. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10591-025-09742-2

Weisenmuller, C., & Hilton, D. (2021). Barriers to access, implementation, and utilization of parenting interventions: Considerations for research and clinical applications. American Psychologist, 76(1), 104-115. https://doi.org/10.1037/amp0000613

Wells, M. B., Sarkadi, A., & Salari, R. (2016). Mothers' and fathers' attendance in a community-based universally offered parenting program in Sweden. Scandinavian Journal of Public Health, 44(3), 274-280. https://doi.org/10.1177/1403494815618841

Wilder, S. (2023). Effects of parental involvement on academic achievement: A meta-synthesis. In J. Martin, M. Bowl & G. Banks (Eds.), Mapping the Field: 75 Years of Educational Review (Vol. 2, pp. 377-397). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003403722

Funding: The authors declare that they have received the following financial support for the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article: Coordination for the Improvement of Higher Level Personnel (CAPES) - Finance Code 001 (Process 88887.967256/2024-00) (Master’s degree in Psychology) and the Fundação de Amparo a Pesquisa e Inovação do Estado de Santa Catarina (FAPESC) (PhD student in Psychology) for HLReis; National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq, Senior Investigator, number 306132/2023-0) for MBM Linhares; National Council for Scientific and Technological Development (CNPq, Research Productivity Grant, number 306132/2023-0) and Institute for Research on Sociocultural Variations (IPEVSC) for MLVieira.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

How to cite: Reis, H. L., Linhares, M. B. M., & Vieira, M. L. (2025). Fathers’ engagement in parenting programs: A systematic review study. Ciencias Psicológicas, 19(2), e-4488 https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v19i2.4488

Authors’ contribution (CRediT Taxonomy): 1. Conceptualization; 2. Data curation; 3. Formal Analysis; 4. Funding acquisition; 5. Investigation; 6. Methodology; 7. Project administration; 8. Resources; 9. Software; 10. Supervision; 11. Validation; 12. Visualization; 13. Writing: original draft; 14. Writing: review & editing.

H. L. R. has contributed in 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14; M. B. M. L. in 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13; M. L. V. in 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14.

Scientific editor in-charge: Dr. Cecilia Cracco.

Ciencias Psicológicas; v19(2)

July-December 2025

10.22235/cp.v19i2.4488