Julho-dezembro 2025

10.22235/cp.v19i2.4477

Gaslighting em relacionamentos íntimos: uma revisão de escopo

Gaslighting in Intimate Relationships: A Scoping Review

Gaslighting en las relaciones íntimas: una revisión de alcance

Mayara de Oliveira Silva Machado1, ORCID 0000-0002-4922-4828

Patrícia Nunes da Fonseca2, ORCID 0000-0002-6322-6336

Anna Dhara Guimarães Tannuss3, ORCID 0000-0001-6945-4041

Dayane Gabrielle do Nascimento Dias4, ORCID 0000-0002-4175-0217

Rayssa Soares Pereira5, ORCID 0000-0002-9102-8951

1 Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Brasil, [email protected]

2 Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Brasil

3 Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Brasil

4 Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Brasil

5 Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Brasil

Resumo:

Este estudo realizou uma revisão de escopo sobre o gaslighting em relacionamentos íntimos, com o objetivo de analisar como a literatura científica tem estudado o fenômeno, em adultos, sem restringir os estudos com base no sexo, identidade de gênero ou tipo de relação afetiva dos parceiros envolvidos. A pesquisa foi conduzida nas bases de dados Scopus, CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycNet, PubMed, PsycInfo e Sage Journals, e uma busca complementar no Google Acadêmico com o objetivo de rastrear estudos nacionais não indexados em periódicos de alto impacto. Os achados resultaram em 14 estudos considerados elegíveis para a inclusão na análise principal. Os resultados demonstraram que o gaslighting em relacionamentos íntimos tem sido investigado sob sete perspectivas principais: fatores de risco e preditores, táticas ou mecanismos, motivações, instrumentos de avaliação, danos causados às vítimas, estratégias de coping e variáveis correlatas do gaslighting. É importante destacar que os artigos selecionados adotaram um delineamento amostral de conveniência, composto predominantemente com amostras do gênero feminino, o que pode influenciar a compreensão deste fenômeno. Em suma, estima-se que os achados desse estudo possam contribuir para o desenvolvimento de novas pesquisas sobre o fenômeno, especialmente em contexto brasileiro e possibilitem uma discussão de estratégias de intervenção que busquem identificar, prevenir e enfrentar essa forma de violência nas relações amorosas, a fim de promover relacionamentos mais saudáveis.

Palavras-chave: gaslighting; relacionamentos íntimos; violência psicológica; revisão de escopo.

Abstract:

This study carried out a scoping review on gaslighting in intimate relationships, with the aim of analyzing how the scientific literature has studied the phenomenon in adults, without restricting the studies according to sex, gender identity or the type of affective relationship of the partners involved. The search was conducted in the databases Scopus, CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycNet, PubMed, PsycInfo and Sage Journals, and a complementary search in Google Scholar with the aim of screening out national studies not indexed in high-impact journals. The findings resulted in 14 studies considered eligible for inclusion in the main analysis. The results showed that gaslighting in intimate relationships has been investigated from seven main perspectives: risk factors and predictors, tactics or mechanisms, motivations, assessment tools, harm caused to victims, coping strategies and correlated variables of gaslighting. It is important to note that the articles selected adopted a convenience sample design, composed predominantly of female samples, which may influence the understanding of this phenomenon. In short, it is hoped that the findings of this study can contribute to the development of new research into the phenomenon, especially in the Brazilian context, and enable a discussion of intervention strategies that seek to identify, prevent and deal with this form of violence in love relationships, in order to promote healthier relationships.

Keywords: gaslighting; intimate relationships; psychological violence; scoping review.

Resumen:

Este estudio realizó una revisión de alcance sobre el gaslighting en las relaciones íntimas, con el objetivo de analizar cómo la literatura científica ha estudiado el fenómeno en adultos, sin restringir los estudios en función del sexo, la identidad de género o el tipo de relación afectiva de los miembros de la pareja implicados. La búsqueda se realizó en las bases de datos Scopus, CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycNet, PubMed, PsycInfo y Sage Journals, y una búsqueda complementaria en Google Scholar con el objetivo de localizar estudios nacionales no indexados en revistas de alto impacto. Los resultados dieron lugar a 14 estudios considerados aptos para su inclusión en el análisis principal. Los resultados mostraron que el gaslighting en las relaciones íntimas ha sido investigado desde siete perspectivas principales: factores de riesgo y predictores, tácticas o mecanismos, motivaciones, herramientas de evaluación, daño causado a las víctimas, estrategias de afrontamiento y variables correlacionadas con el gaslighting. Es importante señalar que los artículos seleccionados adoptaron un diseño muestral de conveniencia, compuesto predominantemente por muestras femeninas, lo que puede influir en la comprensión de este fenómeno. En resumen, se espera que los resultados de este estudio puedan contribuir al desarrollo de nuevas investigaciones sobre el fenómeno, especialmente en el contexto brasileño, y posibilitar la discusión de estrategias de intervención que busquen identificar, prevenir y lidiar con esa forma de violencia en las relaciones amorosas, a fin de promover relaciones más saludables.

Palabras clave: gaslighting; relaciones íntimas; violencia psicológica; revisión de alcance.

Recebido: 13/02/2025

Aceito: 12/08/2025

Nos últimos anos, as discussões sobre violência psicológica cresceram significativamente (Capezza et al., 2021; Keatley et al., 2022; Martínez-González et al., 2021). Um tipo específico desse abuso discreto que tem se destacado em relação a outros e atraído muita atenção é o gaslighting. O termo gaslighting tem se tornado cada vez mais popular e é amplamente utilizado para descrever estratégias abusivas de manipulação em diferentes relações interpessoais (e.g., familiares, amorosas, de trabalho), com objetivo de fazer a vítima duvidar de sua capacidade de julgamento (Gass & Nichols, 1988; Klein et al., 2023; Sweet, 2019).

O crescente interesse da população pelo tema é evidenciado no aumento da busca pela palavra na internet que levou o Merriam-Webster a escolher “gaslighting” como a palavra do ano em 2022 (Merriam-Webster, 2022). Programas de tv, como o reality show britânico Love Island, que tem conquistado audiência de pessoas em todo mundo, inclusive no Brasil, têm fomentado discussões entre os espectadores, nas redes sociais (e.g., X, Instagram, Facebook) sobre a violência entre parceiros íntimos, especificamente acerca do gaslighting. A popularidade do programa, junto a sua visibilidade nas mídias sociais, tem contribuído para a disseminação cultural desse tipo de abuso (Porter & Standing, 2020).

Além disso, o assunto tem despertado interesse de autores e cineastas que utilizam o tema em produções como os filmes Your Reality e Live-Action Captain Marvel (Hammer & Kavanaugh, 2024), onde as protagonistas vivenciam o gaslighting por parte de parceiros íntimos, e em livros de autoajuda como O Efeito Gaslight: como identificar e sobreviver à manipulação velada que os outros usam para controlar sua vida (Stern, 2019) e O Fenômeno Gaslighting: saiba como funciona a estratégia de pessoas manipuladoras para distorcer a verdade e manter você sob controle (Sarkis, 2019). A representação visual e literária dessa forma de violência retratada em filmes, programas de TV e livros têm possibilitado a conscientização da sociedade sobre o gaslighting como uma forma de violência psicológica, auxiliando pessoas a reconhecerem esses comportamentos em suas próprias vidas (Ghaltakhchyan, 2024; Hammer & Kavanaugh, 2024).

Nesse contexto, a crescente atenção e popularidade do fenômeno têm repercutido também nas esferas jurídicas. Segundo Mikhailova (2018, como citado em Sweet, 2019), o gaslighting foi oficialmente incorporado à legislação criminal sobre violência doméstica no Reino Unido em 2015, resultando em mais de 300 pessoas acusadas desse tipo de abuso. No Brasil, embora o termo "gaslighting" ainda não seja mencionado de forma explícita na legislação, o fenômeno é reconhecido juridicamente como uma forma de violência psicológica contra a mulher. Conforme previsto na Lei nº 14.188/2021, especificamente no artigo 147-B do Código Penal, que constitui crime práticas como manipulação, ameaça, ridicularização e isolamento com o objetivo de degradar ou controlar comportamentos, crenças e decisões, causando danos à saúde psicológica e autodeterminação da mulher (Brasil, 2021).

Dados relevantes indicam o gaslighting como característica central da violência entre parceiros íntimos (Bhatti et al., 2023; Hailes & Goodman; 2023; Sweet, 2019), podendo também ocorrer em relacionamentos íntimos que não são considerados abusivos (Klein et al., 2023; Sweet, 2019), o que aumenta a preocupação com os danos à saúde e ao bem-estar das vítimas. A vista disso, diversas evidências sugerem que a violência psicológica pode ser mais prejudicial e ter efeitos mais duradouros do que a violência física (Hester et al., 2017), destacando a urgência de tratá-la como uma questão de saúde pública.

Gaslighting: “quem de nós está louco?”

Atualmente, o gaslighting é amplamente definido como uma forma de violência psicológica em que uma pessoa manipula o julgamento de outra, fazendo-a questionar sua própria capacidade mental para compreender a realidade (Abramson, 2014; Calef & Weinshel, 1981; Sweet, 2019). Esse fenômeno envolve dois agentes: o agressor chamado de “gaslighter”, que utiliza táticas de manipulação como mentir, negar ou esconder, e a vítima conhecida como “gasligthee”, que passa a duvidar de suas próprias habilidades para perceber, julgar e decidir sobre as suas próprias experiências (Calef & Weinshel, 1981; Hailes & Goodman; 2023; Sweet, 2019). No entanto, sua definição nem sempre foi a mesma, e a compreensão desse fenômeno se desenvolveu ao longo do tempo.

O termo “gaslighting” surgiu originalmente do filme Gaslight, produzido por Patrick Hamilton em 1938. A trama narra um relacionamento abusivo no qual uma mulher é levada a acreditar que está enlouquecendo devido às manipulações de seu marido, que planejava interná-la em um hospital psiquiátrico para roubar sua herança de família (Calef & Weinshel, 1981; Kutcher, 1982). Gregory, o marido, se comunicava de forma autoritária e ambígua com sua esposa, Paula, criando situações que a faziam questionar suas próprias percepções da realidade. Uma das maneiras que ele utilizava para confundi-la era alterar o brilho das lâmpadas a gás, de onde vem o título da obra, e negar que a intensidade das luzes estivesse diferente, acusando-a de estar imaginando coisas (Calef & Weinshel, 1981; Sweet, 2019).

A partir dessa representação popular, padrões semelhantes de comportamentos manipulativos foram observados em diferentes contextos sociais o que impulsionou investigações científicas sobre o fenômeno (Calef & Weinshel, 1981; Kutcher, 1982). Os primeiros relatos na literatura foram encontrados entre as décadas de 1960 e 1970 (Barton & Whitehead, 1969; Sheikh, 1979; Smith & Sinanan, 1972), descrevendo o gaslighting como a tentativa de um agressor convencer terceiros, em especial, médicos psiquiatras, de que a vítima possuía distúrbios mentais que a tornava incapaz de conviver socialmente. Essa manipulação era vista como um ato consciente, motivado por ganhos pessoais, financeiros ou como meio de resolver problemas familiares e pouca ou nenhuma atenção foi dada a vítima (Barton & Whitehead, 1969; Sheikh, 1979).

Na década de 1980 houve uma mudança significativa na forma como o gaslighting passou a ser descrito e compreendido. Os estudos passaram a definir o fenômeno como um processo no qual o agressor, não mais tentava convencer terceiros, mas sim à própria vítima de sua incapacidade cognitiva para entender e lidar corretamente com as situações cotidianas (Calef & Weinshel, 1981; Kutcher, 1982), forma como é entendido até hoje. Apesar da mudança conceitual, os comportamentos associados ao gaslighting podem ser observados desde a peça de Hamilton como ações enganosas e insidiosas de manipulação que incluem, a negação de fatos nos quais a vítima tem razão de acreditar, distorção da realidade, culpabilização indevida e insultos verbais que desafiam o estado mental da vítima (Hailes & Goodman; 2023; Klein et al., 2023; Sweet, 2019).

Embora mulheres também possam usar dessas táticas abusivas contra homens (Graves & Samp, 2021; Stern, 2007; Tager-Shafrir et al., 2024), o gaslighting é frequentemente associado à violência de gênero, com a maioria dos estudos descrevendo homens como agressores e mulheres como vítimas (Abramson, 2014; Bhatti et al., 2023; Sweet, 2019). Os primeiros estudos sobre o tema relataram casos em que maridos com relacionamentos extraconjugais usavam estratégias como mentiras e acusações para confundir suas esposas, empregando estereótipos sexistas como “mulheres são exageradas”, “ciumentas”, e “emocionais”, para negar a validade dos sentimentos e percepções das mulheres (Calef & Weinshel, 1981; Gass & Nichols, 1988).

Nesse contexto, pesquisas enfatizam que o gaslighting está enraizado em estereótipos de gênero. Por isso, insultos verbais como, “vadia” “louca”, e “histérica" são frequentemente utilizados para deslegitimar as crenças, julgamentos e comportamentos das mulheres (Boring, 2020; Sweet, 2019). Apesar do gaslighting compartilhar características de violência psicológica e controle coercitivo, ele se distingue por ter como objetivo principal minar autoconfiança das vítimas para que aceitem a realidade imposta pelo agressor (Abramson, 2014; Sweet, 2019).

Dado os diversos impactos que esse comportamento pode gerar, alguns estudos buscaram investigar as motivações dos agressores e as consequências para as vítimas do gaslighting (Calef & Weinshel, 1981; Klein et al., 2023). Embora, seja difícil identificar a intenção por trás dos comportamentos, diferentes pesquisas mostram que a motivação do agressor pode ser de natureza consciente, orientada por ganhos pessoais, como por exemplo, financeiro, e inconsciente, resultante de transtornos psicológicos, necessidade de controle do parceiro, ou para evitar a responsabilização de suas ações (Bashford & Leschziner, 2015; Calef & Weinshel, 1981; Klein et al., 2023). Nesse sentido, a literatura tem apontado que traços de personalidade aversivos como o psicotiscimo, sadismo, maquiavelismo e narcisismo podem estar relacionados a comportamentos de gaslighting (March et al., 2023; Miano et al., 2021).

As vítimas dessa violência relatam danos emocionais duradouros, com impactos negativos na saúde e bem-estar mesmo após o término dos relacionamentos abusivos (Hailes & Goodman; 2023; Klein et al., 2023). Estudos destacam perda de autoconfiança, sentimentos de confusão, dúvidas sobre memória e capacidade de compreensão da realidade, além de perceberem-se como ‘loucas”. Enquanto algumas vítimas relatam conseguirem superar o trauma após o término, para outras, a recuperação é mais lenta, com prejuízos emocionais (e.g., sentimentos de tristeza, culpa, incapacidade), e sociais (e.g., dificuldade para confiar em outras pessoas, isolamento, menor qualidade de relacionamentos), mais duradouros (Hailes & Goodman; 2023; Klein et al., 2023).

Diante de notável atenção popular e crescente interesse acadêmico acerca do gaslighting, torna-se importante conhecer como os estudos científicos têm abordado o tema, especialmente nas relações amorosas, onde são particularmente comuns (Akdeniz & Cihan, 2023; Stern, 2007). Assim, este estudo teve como objetivo geral analisar como a literatura científica tem estudado o gaslighting em relacionamentos íntimos. Especificamente, pretende-se: 1) identificar preditores do gaslighting, 2) averiguar táticas ou mecanismos do gaslighting, 3) explorar as motivações para a perpetração do gaslighting, 4) identificar instrumentos de avaliação do gaslighting, 5) verificar as estratégias de coping adotadas pelas vítimas do gaslighting, e por fim, 6) conhecer variáveis correlatas do gaslighting.

Método

Este estudo, de natureza exploratória, realiza uma revisão de escopo das publicações nacionais e internacionais sobre o fenômeno do gaslighting em relacionamentos íntimos. A revisão de escopo é um método rigoroso e transparente, que visa mapear a literatura existente em uma área específica, permitindo tanto a análise das características das pesquisas quanto a identificação de lacunas na literatura disponível (Munn et al., 2018). Vale ressaltar que esse tipo de revisão não contempla a avaliação da qualidade das publicações analisadas (Pham et al., 2014). A revisão de escopo conduzida neste estudo seguiu as diretrizes metodológicas propostas pelo Instituto Joanna Briggs (Aromataris et al., 2020) e o checklist Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR, Page et al., 2021; Tricco et al., 2018). A presente revisão também foi registrada na plataforma Open Science Framework podendo ser acessado por meio do DOI https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/Z7RCW.

Estratégia de busca

Esta revisão busca responder à seguinte pergunta: “Como a literatura científica tem estudado o gaslighting em relacionamentos íntimos?” Para responder o problema de pesquisa, utilizou-se o acrônimo PCC (População, Conceito e Contexto). A população de interesse foi composta por indivíduos com 18 anos ou mais, o conceito se referiu a estudos que investigam o fenômeno do gaslighting e o contexto foi delimitado para incluir indivíduos envolvidos em relacionamentos íntimos.

Por se tratar de uma revisão de escopo, optou-se metodologicamente por não restringir os estudos analisados com base no sexo, identidade de gênero ou tipo de relação afetiva dos parceiros envolvidos. Essa decisão se fundamenta na natureza exploratória das revisões de escopo (Peters et al., 2020). Essa estratégia visa oferecer um panorama mais abrangente sobre como o gaslighting tem sido conceituado, investigado e discutido na literatura científica, possibilitando a identificação de lacunas no conhecimento e subsidiando futuras pesquisas com escopos mais específicos.

A estratégia de busca abrangeu o período de setembro de 2023 a agosto de 2024, com a seleção das bases de dados Scopus, CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycNet, PubMed, PsycInfo e Sage Journals. Não houve delimitação do período de publicação, com o objetivo de abranger toda a produção científica disponível sobre o fenômeno do gaslighting em relacionamentos íntimos. As técnicas de busca foram desenvolvidas para serem aplicáveis a qualquer banco de dados científico, utilizando as palavras-chave fornecidas. Assim, foi adotada seguinte estratégia de busca (relationships OR “intimate relationships” OR “interpessonal relationships” OR “romantic relationship” AND “gasli*” OR “gaslight” OR “gaslighted” OR “gaslit” OR “gaslights” OR “gaslighting”), considerando resumos e títulos.

Critérios de elegibilidade

Os critérios de inclusão para a seleção dos estudos foram: artigos científicos empíricos que 1) abrangessem pesquisas, intervenções, estudos de caso e relatos de experiência, 2) publicados em qualquer período, 3) tratassem do gaslighting em relacionamentos íntimos, 4) com amostras compostas por indivíduos com 18 anos ou mais, 5) disponíveis em acesso aberto ou fechado, 6) escritos em qualquer idioma, e 7) realizados em qualquer país.

Os critérios de exclusão foram documentos que atendiam a pelo menos uma das seguintes condições: 1) o título, resumo ou texto completo não estivessem relacionados ao gaslighting em relacionamentos íntimos, 2) fossem publicados na forma de capítulos de livros, revisões, teses, dissertações e estudos teóricos, 3) incluíssem amostras com participantes menores de 18 anos, e 4) cujo texto completo não estivesse disponível.

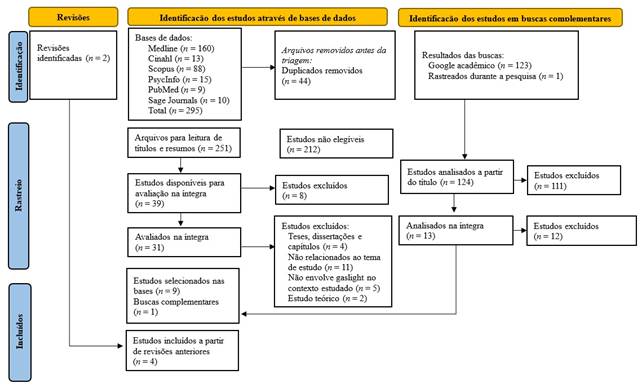

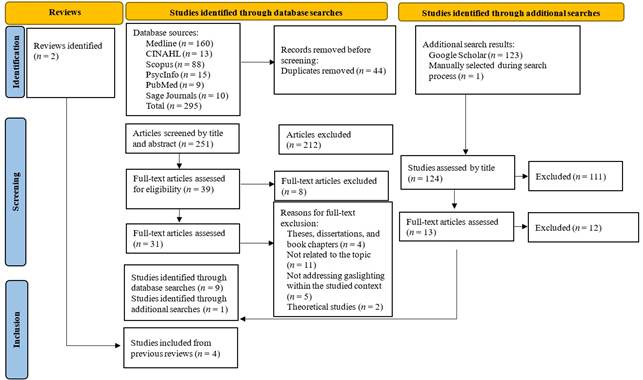

Extração e síntese dos dados

A presente revisão de escopo foi realizada com base no protocolo Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta‐Analyses (PRISMA). O fluxograma PRISMA, que detalha o processo de seleção dos artigos, é apresentada na Figura 1. Os metadados dos artigos identificados nas bases de dados mencionadas foram extraídos no formato Referência de Pesquisa Intercambiável (RIS). Para garantir uma busca ampla, revisões anteriores sobre o tema também foram consultadas e foram aplicadas as estratégias de backward e forward (Haddaway et al., 2022). Além disso, uma busca complementar foi realizada no Google Acadêmico com o objetivo de rastrear estudos nacionais não indexados em periódicos de alto impacto.

Todos os metadados foram exportados para o software Rayyan, desenvolvido pelo Qatar Computing Research Institute, no qual estudos duplicados foram removidos e foi estabelecido. A seleção e triagem dos estudos foram conduzidas de forma independente por dois juízes, abrangendo as etapas de triagem, elegibilidade e inclusão. Em casos de discordância entre as avaliações, foram realizadas reuniões de alinhamento e, se necessário, a colaboração de um terceiro pesquisador foi solicitada para assegurar a imparcialidade e a validade do processo de seleção. Os artigos considerados relevantes foram submetidos a uma análise completa de seu conteúdo textual.

Resultados

Resultados da seleção dos estudos

A busca inicial nas bases de dados Medline, Cinahl, Scopus, PsycInfo, PsycNet, PubMed e Sage Journals recuperou um total de 295 arquivos (Figura 1). Após a remoção da duplicadas, restaram 251 arquivos. Destes, 212 estudos foram considerados não elegíveis e 8 foram excluídos por não atenderem aos critérios de inclusão. Dos 31 estudos restantes que foram avaliados na íntegra, nove foram selecionados. Adicionalmente, os achados de revisões anteriores identificaram quatro novos estudos. As buscas complementares realizadas durante o processo geraram 125 resultados, dos quais 13 estudos foram analisados íntegra, com 12 sendo excluídos. Esse processo resultou na inclusão final de 14 estudos considerados elegíveis para a inclusão na análise principal.

Figura 1: Fluxograma de rastreio dos estudos incluídos

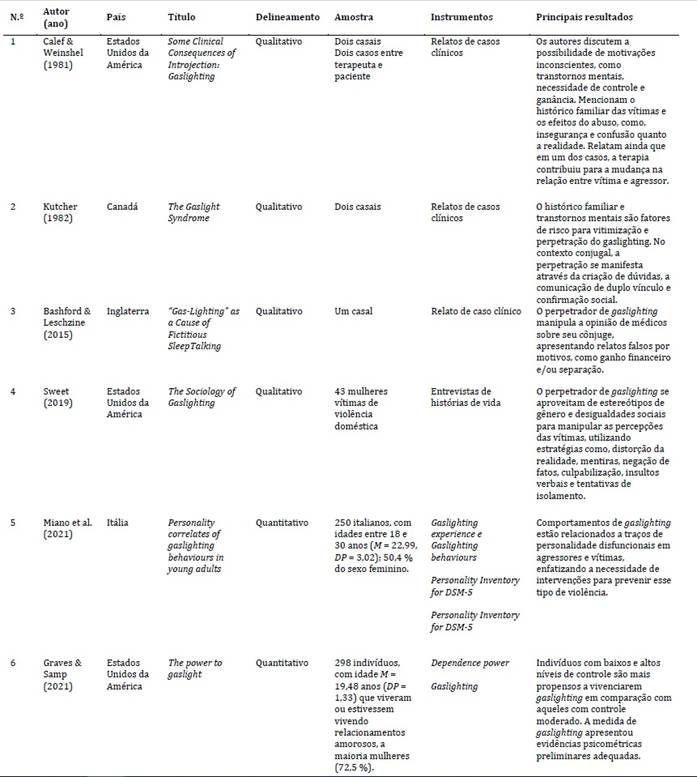

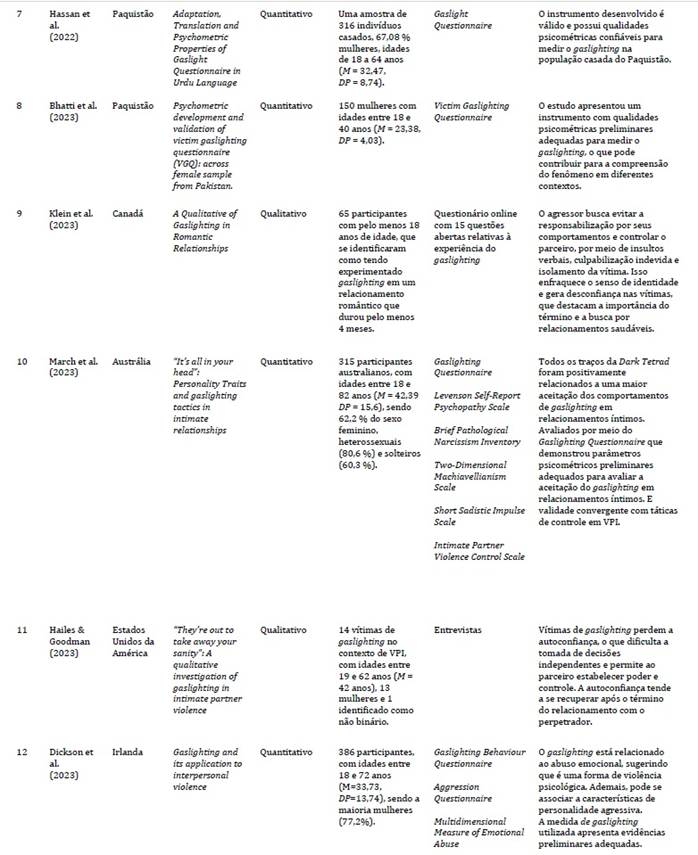

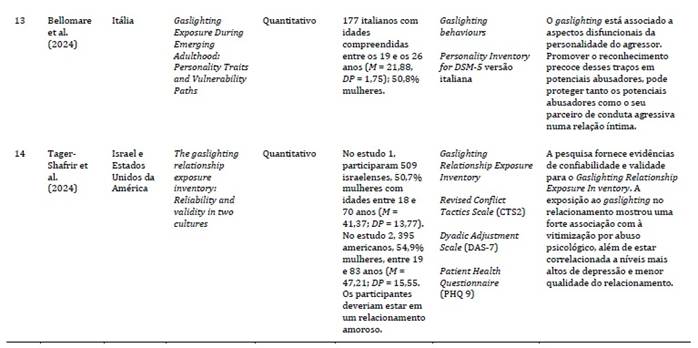

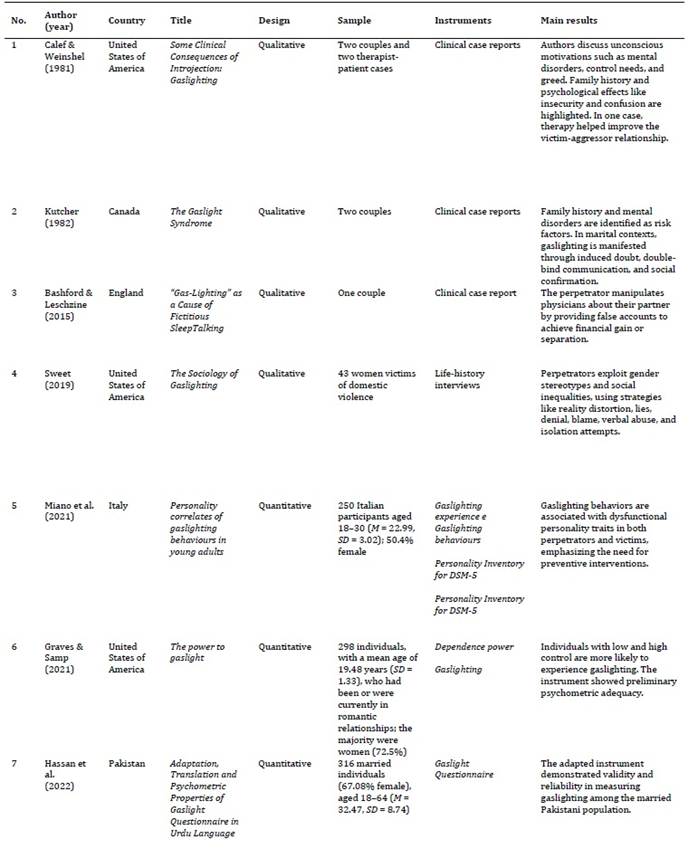

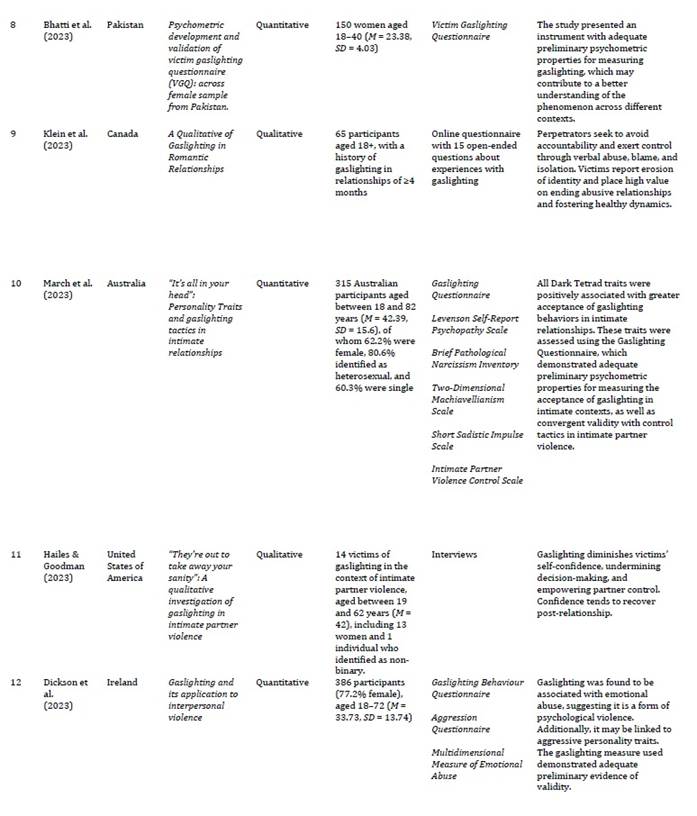

Resultado das características dos estudos

No recorte temporal desta revisão, 2023 destacou-se com o maior número de publicações, totalizando quatro artigos. Em seguida, o ano de 2021 contribui com três artigos e 2024 com duas publicações. Os anos de 1981, 1982, 2015, 2019 e 2022 apresentaram apenas um estudo cada. Não foram encontradas publicações que atendessem aos critérios de seleção entre os anos de 1983 e 2014 e nos anos de 2016, 2017 e 2018.

Em termos de origem geográfica, a maioria dos artigos provém dos Estados Unidos (n = 5). Também foram encontradas contribuições do Canadá (n = 2), Itália (n = 2), Paquistão (n = 2), Inglaterra (n = 1), Irlanda (n = 1), Israel (n = 1) e Austrália (n = 1). Destaca-se que um estudo (Tager-Shafrir et al., 2024), foi realizado em dois países simultaneamente, Israel e Estados Unidos.

No que tange ao tipo de produção científica, todos os artigos selecionados foram publicados em inglês e adotaram um delineamento amostral de conveniência, predominantemente com amostras do gênero feminino. A maioria dos estudos utilizou um desenho transversal. Sete estudos empregaram metodologias qualitativas, utilizando como instrumentos relatos de casos (n = 4), entrevistas (n = 2) e questionário com perguntas abertas (n = 1). Em contrapartida, oito estudos aplicaram métodos quantitativos, utilizando instrumentos de autorrelato (e.g., Revised Conflict Tactics Scale, Aggression Questionnaire, Multidimensional Measure of Emotional Abuse) para analisar a relação de variáveis antecedentes e consequentes do gaslighting. Dentre esses, cinco estudos realizaram análises psicométricas para validar medidas específicas para avaliar o gaslighting, como Victim Gaslighting Questionnaire (VGQ; Bhatti et al., 2023), Gaslight Questionnaire (Stern, 2007) adaptado por Hassan et al. (2022), Gaslighting Behaviour Questionnaire (GBQ; Dickson et al., 2023). Gaslighting Questionnaire (March et al., 2023), e Gaslighting Relationship Exposure Inventory (GREI; Tager-Shafrir et al., 2024).

Síntese das fontes de evidência elegidas

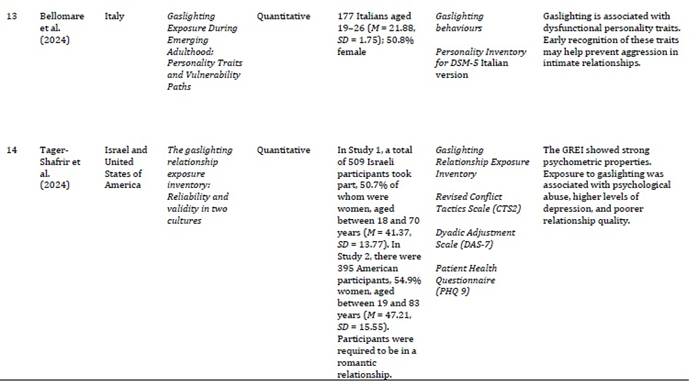

A Tabela 1 apresenta a síntese dos estudos mapeados, conforme os objetivos da revisão.

Tabela 1: Síntese dos estudos

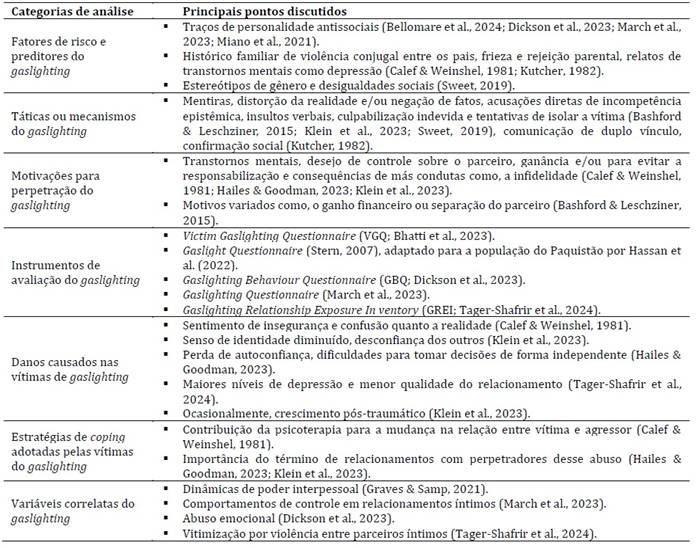

Conteúdos analizados

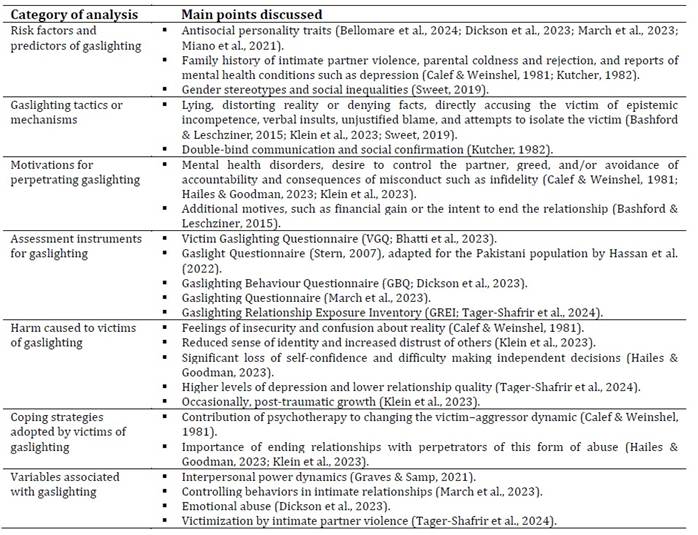

Com base nos resultados dos estudos selecionados, foram identificadas as seguintes categorias de análise: (1) fatores de risco e preditores do gaslighting, (2) táticas ou mecanismos do gaslighting, (3) motivações para perpetração do gaslighting, (4) instrumentos de avaliação do gaslighting, (5) danos causados nas vítimas de gaslighting, (6) estratégias de coping adotadas pelas vítimas do gaslighting, e (7) variáveis correlatas ao gaslighting. Vale ressaltar que alguns artigos foram incluídos em mais de uma categoria de análise, conforme detalhado na Tabela 2.

Fatores de risco e preditores do gaslighting. Essa categoria abrange sete artigos que investigam os fatores que influenciam a probabilidade de perpetração e vitimização do gaslighting. Os estudos indicam os traços de personalidade antissociais (e.g., narcisismo, maquiavelismo, sadismo, psicopatia), como prevalentes tanto em perpetradores quanto nas vítimas (Bellomare et al., 2024; Dickson et al., 2023; March et al., 2023; Miano et al., 2021). O histórico familiar também é destacado como um aspecto relevante nos casos de gaslighting, sendo especificado vivencias semelhantes de violência conjugal entre os pais da vítima, frieza e rejeição parental, além de transtornos mentais como a depressão na família da vítima (Calef & Weinshel, 1981; Kutcher, 1982). Ademais, estereótipos de gênero e desigualdades sociais são considerados mecanismos que facilitam a prática dessa forma de violência (Sweet, 2019).

Táticas ou mecanismos do gaslighting. Essa categoria inclui quatro artigos que descrevem os comportamentos prevalentes neste tipo de violência. Os estudos identificam práticas como mentiras, distorção da realidade e/ou negação de fatos, acusações diretas de incompetência epistêmica, insultos verbais, culpabilização indevida e tentativas de isolar a vítima (Bashford & Leschziner, 2015; Klein et al., 2023; Sweet, 2019). Adicionalmente, são abordadas táticas como comunicação de duplo vínculo e confirmação social (Kutcher, 1982).

Motivações para perpetração do gaslighting. Essa categoria abrange quatro artigos que investigam as motivações subjacentes à prática de gaslighting em seus relacionamentos íntimos. Os achados sugerem que essas motivações podem ser tanto conscientes quanto inconscientes. Entre os motivos identificados estão transtornos mentais, desejo de controle sobre o parceiro, ganância, tentativa de evitar a responsabilização e as consequências de comportamentos indesejados (Calef & Weinshel, 1981; Hailes & Goodman, 2023; Klein et al., 2023). Ademais, o gaslighting pode ser motivado por ganhos financeiros e a tentativa de provocar a separação do parceiro (Bashford & Leschziner, 2015).

Instrumentos de avaliação do gaslighting. Essa categoria abrange cinco artigos focados na validação psicométrica de instrumentos para avaliar o gaslighting em relacionamentos íntimos. Os estudos demostraram que as medidas possuem evidências preliminares de validade e precisão adequadas, sendo todos os instrumentos de autorrelato: Victim Gaslighting Questionnaire (VGQ; Bhatti et al., 2021), Gaslight Questionnaire (Stern, 2007) adaptado para a população do Paquistão por Hassan et al. (2022), Gaslighting Behaviour Questionnaire (GBQ; Dickson et al., 2023), Gaslighting Relationship Exposure In ventory (GREI; Tager-Shafrir et al., 2024), e Gaslighting Questionnaire (March et al., 2023).

Danos causados nas vítimas de gaslighting. Essa categoria contempla quatro artigos que detalham os danos causados nas vítimas de gaslighting. Os estudos relataram uma série de consequências negativas, incluindo sentimento de insegurança e confusão sobre a realidade (Calef & Weinshel, 1981), redução do senso de identidade, desconfiança dos outros (Klein et al., 2023), perda significativa de autoconfiança e dificuldades em tomar decisões de forma independente (Hailes & Goodman, 2023). Adicionalmente, relata-se maiores níveis de depressão e menor qualidade do relacionamento (Tager-Shafrir et al., 2024). Em alguns casos, após a superação dessa violência, algumas vítimas experimentaram crescimento pós-traumático (Klein et al., 2023).

Estratégias de coping adotadas pelas vítimas do gaslighting. Essa categoria inclui três artigos que exploram maneiras para a recuperação da vitimização pela violência supracitada. Um estudo destaca a eficácia da psicoterapia na promoção de mudanças significativas na relação entre vítima e agressor (Calef & Weinshel, 1981). Outros estudos enfatizam a importância de terminar relacionamentos com perpetradores de gaslighting como uma estratégia para superar a violência sofrida e recuperar a autoconfiança (Hailes & Goodman, 2023; Klein et al., 2023).

Variáveis correlatas do gaslighting. Essa categoria reúne quatro artigos que buscaram conhecer a relação do gaslighting com variáveis psicossociais. Os estudos identificaram a relação do gaslighting com dinâmicas de poder interpessoal (Graves & Samp, 2021), comportamentos de controle em relacionamentos íntimos (March et al., 2023), abuso emocional (Dickson et al., 2023) e vitimização por violência entre parceiros íntimos (Tager-Shafrir et al., 2024).

Tabela 2: Categorias de análise obtidas a partir dos resultados dos estudos

Discussão

A presente revisão de escopo analisou estudos acerca do gaslighting em relacionamentos íntimos, investigando como a literatura científica tem estudado o fenômeno. Observou-se que o maior número de publicações sobre o tema ocorreu em 2023, o que reflete a recente popularização do tema, evidenciada pelo aumento nas buscas do termo na internet, levando o Merriam-Webster a eleger “gaslighting” como a palavra do ano em 2022 (Merriam-Webster, 2022). Essa visibilidade tem atraído a atenção de pesquisadores para investigações científicas recentes. No entanto, apesar do interesse crescente, ainda há uma quantidade limitada de literatura científica sobre o tema, indicando a necessidade de mais estudos (Hailes & Goodman, 2023; Tager-Shafrir et al., 2024).

Além disso, verificou-se uma lacuna de mais de trinta anos nas publicações sobre tema, entre os primeiros estudos selecionados da década de 1980 ao ano de 2015. Esse fato pode estar relacionado as mudanças na compreensão do fenômeno, que passou inicialmente, de uma tentativa de convencer terceiros, especialmente médicos psiquiatras, sobre a incompetência epistêmica do parceiro (Barton & Whitehead, 1969; Smith & Sinanan, 1972), ao convencimento da própria vítima de sua incapacidade mental (Calef & Weinshel, 1981; Gass & Nichols, 1988). Essa mudança pode ter sido influenciada pelo fechamento de hospitais psiquiátricos em várias partes do mundo durante esse período, tornando inviável a estratégia de institucionalizar alguém, o que contribuiu para a mudança na definição e compreensão do gaslighting (Klein et al., 2023).

As análises revelaram ainda, uma maior concentração da produção científica sobre o tema nos Estados Unidos da América, seguido de outros países de língua inglesa como Canadá (Klein et al., 2023; Kutcher, 1982), Reino Unido (Bashford & Leschziner, 2015; Dickson et al., 2023) e Austrália (March et al., 2023). Isso pode ser explicado pelo uso do termo em inglês para descrever o fenômeno e todos os artigos estarem disponíveis nessa língua. Observa-se, porém, um aumento no empréstimo de termos em inglês para outras línguas como, português e espanhol, sendo incorporado ao vocabulário brasileiro diferentes fenômenos psicossociais como stalking, cyberstalking e bullying, além do gaslighting. Esse aspecto é evidenciado devido aos avanços das tecnologias da comunicação e das mídias sociais (e.g., Facebook, Instagram, WhatsApp), que permitem a disseminação de uma língua em contexto global (García & Bove, 2022). Diante desse aspecto da globalização, considera-se que a nomenclatura do termo em inglês não deve limitar a expansão do conhecimento sobre um fenômeno presente em diferentes contextos socioculturais.

A análise de conteúdo dos estudos revisados revelou a influência de aspectos individuais (i.e., gênero, traços de personalidade) e sociais (e.g., histórico familiar, estereótipos de gênero, desigualdades sociais) na perpetração e vitimização do gaslighting. Quanto ao gênero, os achados apontam a predominância das mulheres como vítimas e dos homens como perpetradores dessa violência (Bhatti et al., 2023; Hailes & Goodman, 2023; Klein et al., 2023; Sweet, 2019). No entanto, é importante considerar que a compreensão deste fenômeno pode ter sido influenciada pelas especificidades das amostras de conveniência, que foram predominantemente compostas por mulheres. Nessa direção, alguns estudos sugerem não haver diferença entre os gêneros na exposição ao gaslighting (Miano et al., 2021), e um estudo recente realizado em diferentes culturas encontrou que os homens estão mais sujeitos a essa forma de violência (Tager-Shafrir et al., 2024).

Pesquisadores argumentam que o gaslighting se torna mais eficaz quando estereótipos de gênero e desigualdades sociais são utilizados para manipular a realidades das vítimas (Abramson, 2014; Gass & Nichols, 1988; Sweet, 2019). Desqualificar o julgamento de mulheres e grupos sociais desfavorecidos com discursos como “mulheres são loucas”, “exageradas” e “emocionalmente instáveis”, é uma prática antiga na construção da racionalidade baseada em gênero e poder social. Por isso, esse aspecto deve ser considerado por estudiosos do tema na discussão de políticas públicas que explorem a prevenção, a educação e a sensibilização sobre violências entre parceiros íntimos, especificamente sobre o gaslighting (Sweet, 2019).

Traços de personalidade também são apontados como importantes preditores do gaslighting. Os estudos demonstram que pessoas com altos níveis de traços antissociais são mais propensas a vivenciar o gaslighting, tanto como vítimas quanto como perpetradores (Bellomare et al., 2024; March et al., 2023; Miano et al., 2021). Esses achados corroboram pesquisas anteriores que apontaram a relação entre traços disfuncionais de personalidade e um maior risco de se envolver em relacionamentos abusivos (Kasowski & Anderson, 2019). Características de impulsividade, agressividade, frieza emocional, busca por sensações e comportamentos antissociais podem levar esses indivíduos a subestimarem seus próprios comportamentos agressivos e a negar comportamentos abusivos do parceiro (Asen & Fongagy, 2017; Tetreault et al., 2021), aumentando a probabilidade de envolvimento e manutenção de relacionamentos violentos.

O histórico familiar também parece exercer influência sobre vítimas e perpetradores do gaslighting. Aspectos como violência conjugal entre os pais, frieza e rejeição parental e relatos de transtornos mentais, como depressão, são indicados como características relevantes (Calef & Weinshel, 1981; Kutcher, 1982). Esses achados estão de acordo com diferentes evidências que indicam que pessoas que crescem em ambientes expostos à violência familiar, com abusos, negligências agressões e/ou abandono, tendem a replicar esses padrões em seus relacionamentos íntimos, pois acreditam equivocadamente que a perpetração dessas violências é uma forma de resolver os conflitos (Borges & Dell’Aglio, 2020; Zhu et al., 2023).

Em relação as táticas ou mecanismos utilizados por perpetradores do gaslighting, são comumente mencionadas estratégias de confusão, como mentiras, distorção da realidade e/ou negação de fatos, acusações diretas de incompetência epistêmica, insultos verbais, culpabilização indevida, tentativas de isolar a vítima (Bashford & Leschziner, 2015; Klein et al., 2023; Sweet, 2019), comunicação de duplo vínculo e confirmação social (Kutcher, 1982). Essas estratégias são insidiosas e difícil de reconhecer. A invisibilidade dessa violência a torna especialmente prejudicial, pois isola às vítimas de apoio e proteção, o que pode levá-las a se tornarem dependentes de seus agressores. Isso causa danos profundos e duradouros, considerados tão graves quanto, ou até mais graves do que a violência física (Sweet, 2019).

Quanto às motivações para perpetração do gaslighting, observa-se que essa forma de abuso, foi inicialmente descrita como uma manipulação consciente com motivações, sobretudo, externas, como ganho financeiro ou separação do parceiro (Bashford & Leschziner, 2015). Posteriormente, identificou-se que os perpetradores podem não ter plena consciência de suas próprias motivações, que são, muitas vezes, de natureza emocional ou psicopatológicas, como transtornos mentais, necessidade de controle, ganância ou para evitar a responsabilização de más condutas, como a infidelidade (Calef & Weinshel, 1981; Hailes & Goodman, 2023; Klein et al., 2023).

As consequências dessa violência podem abranger esferas de saúde, sociais e jurídicas. Os estudos sugerem graves danos psicológicos para as vítimas do gaslighting, que experienciam sentimento de insegurança e confusão quanto à sua realidade (Calef & Weinshel, 1981), senso de identidade diminuído e desconfiança dos outros (Klein et al., 2023), profunda perda de autoconfiança, dificuldades para tomar decisões de forma independente (Hailes & Goodman, 2023). Além de maiores níveis de depressão e menor qualidade do relacionamento (Tager-Shafrir et al., 2024). Esses resultados estão em consonância com diferentes pesquisas sobre violência psicológica, que revelam um profundo impacto na saúde e bem-estar das vítimas, com o desenvolvimento de transtornos, como ansiedade e depressão, além de danos à sua autonomia pois, devido ao isolamento social, que muitas vezes vivem. No Brasil, tais efeitos podem ter implicações jurídicas, uma vez que a violência psicológica é tipificada como crime (Brasil, 2021; Capezza et al., 2021; Martínez-González et al., 2021).

No que tange às estratégias de coping adotadas pelas vítimas do gaslighting, os estudos sugerem a importância de terminar esses relacionamentos abusivos para promover a recuperação das vítimas (Hailes & Goodman, 2023; Klein et al., 2023). A psicoterapia é mencionada como uma ferramenta relevante, auxiliando as vítimas a identificarem e responder de maneira mais eficaz aos padrões de comportamento abusivo de seus parceiros, além de encorajá-las a priorizar relacionamentos mais saudáveis (Calef & Weinshel, 1981), favorecendo o desenvolvimento de um crescimento pós-traumático após a superação dos danos sofridos (Klein et al., 2023). Esses achados estão de acordo com diferentes pesquisas que indicam a relevância da terapia e do término das relações abusivas para a saúde e o bem-estar das vítimas de violência entre parceiros íntimos (Augustin & Bandeira, 2020).

Por fim, foi possível identificar a relação do gaslighting com diferentes construtos psicossociais como, dinâmicas de poder interpessoal (Graves & Samp, 2021), táticas de controle em relacionamentos íntimos (March et al., 2023), abuso emocional (Dickson et al., 2023) e vitimização por violência entre parceiros íntimos (Tager-Shafrir et al., 2024). Isso sugere a importância de se considerar variáveis individuais e sociais para uma melhor compreensão acerca do fenômeno. Nesse sentido, considera-se pertinente que estudos futuros busquem averiguar em diferentes contextos, a relação de variáveis previamente estabelecidas, como personalidade e gênero e investiguem outros construtos psicossociais, como atitudes e valores humanos, uma vez que estes contribuem para a tomada de decisões e comportamentos sociais, sendo importantes variáveis no estudo da psicologia social.

Conclusões

O gaslighting em relacionamentos íntimos é um fenômeno complexo e crescente, constituindo um grave problema social. Esta revisão sistemática apresenta um panorama acerca de como o tema tem sido estudado até o momento, de modo a suprir a escassez de estudos desse tipo na literatura, sobretudo em língua portuguesa. Trata-se de uma contribuição relevante, sendo a primeira revisão a mapear especificamente pesquisas sobre o gaslighting nos relacionamentos íntimos. As duas anteriores abrangem outros contextos, como política, relações parentais e ambientes de trabalho. Os estudos selecionados são relevantes para o estudo da psicologia social, abordando a influência de variáveis psicossociais como, traços de personalidade, estereótipos de gênero, desigualdades sociais e histórico familiar violento.

Apesar das evidências favoráveis, a pesquisa está sujeita a algumas limitações, como: (1) a definição estrita dos critérios de inclusão e exclusão pode ter levado à omissão de estudos que, embora não se enquadrassem perfeitamente nos critérios estabelecidos, poderiam oferecer contribuições significativas para o entendimento do construto de gaslighting em relacionamentos íntimos, (2) a delimitação dos descritores pode ter excluído estudos relevantes que tratam do gaslighting de forma implícita ou vinculada a outras formas de abuso psicológico. Sugerimos que futuras revisões considerem a inclusão de descritores mais amplos, como “violência psicológica” ou “abuso emocional”, de modo a capturar uma gama mais extensa de investigações relacionadas ao tema, (3) ausência de amostras com participantes brasileiros nos estudos selecionados, o que restringe a aplicação dos resultados à realidade nacional, e (4) as amostras foram predominantemente compostas por mulheres o que pode influenciar a forma como o fenômeno é compreendido.

Diante do exposto, sugere-se a realização de estudos comparativos em países que não falam inglês para investigar diferenças culturais e sociais na percepção do gaslighting, ampliando a visão sobre o fenômeno. Além disso, é importante conhecer como a evolução do gaslighting e as mudanças sociais nas últimas décadas impactaram a prática e as estratégias de prevenção, como por exemplo a ascensão das redes sociais. Ademais, seria interessante desenvolver pesquisas que incluam amostras mais diversas, por exemplo, com uma quantidade maior de homens, para revelar aspectos que podem ter sido negligenciados em estudos anteriores.

Por fim, é importante analisar o impacto jurídico e político do gaslighting, especialmente no contexto brasileiro. Compreender como o gaslighting está sendo tratado legalmente e quais são suas implicações para a justiça pode ajudar a identificar lacunas na proteção das vítimas e melhorar políticas públicas. Essas direções para estudos futuros podem contribuir para uma compreensão mais profunda do gaslighting em relacionamentos íntimos e suas implicações, enriquecendo tanto a literatura acadêmica quanto as práticas de intervenção e prevenção.

Referências

Abramson, K. (2014). Turning up the Lights on Gaslighting. Philosophical Perspectives, 28(1), 1-30. https://doi.org/10.1111/phpe.12046

Akdeniz, B., & Cihan, H. (2023). Gaslighting and interpersonal relationships: Systematic review. Psikivatride Güncel Yaklaslmlar-Current Approaches in Psychiatry, 16(1), 146-158. https://doi.org/10.18863/pgy.1281632

Aromataris, E., Lockwood, C., Porritt, K., Pilla, B., & Jordan, Z. (Eds.) (2020). JBI manual for evidence synthesis. JBI. https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-24-01

Asen, E., & Fonagy, P. (2017). Mentalizing family violence Part 2: Techniques and interventions. Family Process, 56(1), 22-44. https://doi.org/10.1111/famp.12276

Augustin, L. W., & Bandeira, C. C. de A. (2020). Postura e intervenções do gestalt-terapeuta frente à violência psicológica contra a mulher por parceiro íntimo. Revista da Abordagem Gestáltica, 26(SPE), 449-459. https://doi.org/10.18065/2020v26ne.9

Barton, R., & Whitehead, J. A. (1969). The Gas-light phenomenon. The Lancet, 293(7608), 1258-1260. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(69)92133-3

Bashford, J., & Leschziner, G. (2015). Bed partner “Gas-Lighting” as a cause of fictitious sleep-talking. Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine: JCSM: Official Publication of the American Academy of Sleep Medicine, 11(10), 1237-1238. https://doi.org/10.5664/jcsm.5102

Bellomare, M., Genova, V. G., & Miano, P. (2024). Gaslighting exposure during emerging adulthood: Personality traits and vulnerability paths. International Journal of Psychological Research, 17(1), 29-39. https://doi.org/10.21500/20112084.6306

Bhatti, M. M., Shuja, K. H., Aqeel, M., Bokhari, Z., Gulzar, S. N., Fatima, T., & Sama, M. (2023). Psychometric development and validation of victim gaslighting questionnaire (VGQ): Across female sample from Pakistan. International Journal of Human Rights in Healthcare, 16(1), 4-18. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJHRH-12-2020-0119

Borges, J. L., & Dell'Aglio, D. D. (2020). Early maladaptive schemas as predictors symptomatology among victims and non-victims of dating violence. Contextos Clínicos, 13(2), 424-450. https://doi.org/10.4013/ctc.2020.132.04

Boring, R. L. (2020). Implications of narcissistic personality disorder on organizational resilience. Em P. Arezes, & R. Boring (Eds.), Advances in Safety Management and Human Performance (pp. 259-266). Springer.

Brasil. (2021). Lei nº 14.188, de 28 de julho de 2021. Dispõe sobre o programa de cooperação Sinal Vermelho contra a Violência Doméstica como uma das medidas de enfrentamento da violência doméstica e familiar contra a mulher. Brasília, DF.

Calef, V., & Weinshel, E. M. (1981). Some clinical consequences of introjection: Gaslighting. The Psychoanalytic Quarterly, 50(1), 44-66. https://doi.org/10.1080/21674086.1981.11926942

Capezza, N. M., D’Intino, L. A., Flynn, M. A., & Arriaga, X. B. (2021). Perceptions of psychological abuse: The role of perpetrator gender, victim’s response, and sexism. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(3–4), 1414-1436. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260517741215

Dickson, P., Ireland, J., & Birch, P. (2023). Gaslighting and its application to interpersonal violence. Journal of Criminological Research, Policy and Practice, 9(1), 31-46. https://doi.org/10.1108/JCRPP-07-2022-0029

García, I. R., & Bove, K. P. (2022). Ghosting, Breadcrumbing, Catfishing: A corpus analysis of English borrowings in the Spanish speaking world. Languages, 7(2), 119. https://doi.org/10.3390/languages7020119

Gass, G. Z., & Nichols, W. C. (1988). Gaslighting: A marital syndrome. Contemporary Family Therapy, 10(1), 3-16. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF0092242

Ghaltakhchyan, S. (2024). Linguistic portrayal of gaslighting in interpersonal relationships. Armenian Folia Anglistika, 20(1 (29)), 61-79. https://doi.org/10.46991/AFA/2024.20.1.61

Graves, C. G., & Samp, J. A. (2021). The power to gaslight. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 38(11), 3378-3386. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075211026975

Haddaway, N., Grainger, M., & Gray, C. (2022). Citationchaser: A tool for transparent and efficient forward and backward citation chasing in systematic searching. Research Synthesis Methods, 13(4), 533-545. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1563

Hailes, H., & Goodman, L. (2023). “They’re out to take away your sanity”: A qualitative investigation of gaslighting in intimate partner violence. Journal of Family Violence, 40, 269–282. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-023-00652-1

Hammer, T. R., & Kavanaugh, K. E. (2024). A relational exploration of Captain Marvel as a therapeutic tool to understand gaslighting. Journal of Creativity in Mental Health, 19(2), 244-250. https://doi.org/10.1080/15401383.2023.2166185

Hassan, A., Iqbal, N., & Hassan, B. (2022). Adaptation, translation and psychometric properties of Gaslight Questionnaire in Urdu language. Journal of Professional & Applied Psychology, 3, 417-427. https://doi.org/10.52053/jpap.v3i4.146

Hester, M., Jones, C., Williamson, E., Fahmy, E., & Feder, G. (2017). Is it coercive controlling violence? A cross-sectional domestic violence and abuse survey of men attending general practice in England. Psychology of Violence, 7(3), 417-427. https://doi.org/10.1037/vio0000107

Kasowski, A. E., & Anderson, J. L. (2020). The association between sexually aggressive cognitions and pathological personality traits in men. Violence Against Women, 26(12–13), 1636-1655. https://doi.org/10.1177/1077801219873436

Keatley, D. A., Quinn-Evans, L., Joyce, T., & Richards, L. (2022). Behavior sequence analysis of victims’ accounts of intimate partner violence. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 37(21-22), NP19290-NP19309. https://doi.org/10.1177/08862605211043587

Klein, W., Wood, S., & Li, S. (2023). A qualitative analysis of gaslighting in romantic relationships. Personal Relationships, 30, 1316-1340 https://doi.org/10.31234/osf.io/cjrpq

Kutcher, S. P. (1982). The gaslight syndrome. Canadian Journal of Psychiatry. Revue Canadienne De Psychiatrie, 27(3), 224-227. https://doi.org/10.1177/070674378202700310

March, E., Kay, C. S., Dinić, B. M., Wagstaff, D., Grabovac, B., & Jonason, P. K. (2023). “It’s all in your head”: Personality traits and gaslighting tactics in intimate relationships. Journal of Family Violence, 40(2), 259-268. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10896-023-00582-y

Martínez-González, M. B., Pérez-Pedraza, D. C., Alfaro-Álvarez, J., Reyes-Cervantes, C., González-Malabet, M., & Clemente-Suárez, V. J. (2021). Women facing psychological abuse: How do they respond to maternal identity humiliation and body shaming? International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(12), 6627. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18126627

Merriam-Webster. (2022). Word of the Year: Gaslight. https://www.merriamwebster.com/words-at-play/word-of-the-year

Miano, P., Bellomare, M., & Genova, V. G. (2021). Personality correlates of gaslighting behaviours in young adults. Journal of Sexual Aggression, 27(3), 285-298. https://doi.org/10.1080/13552600.2020.1850893

Munn, Z., Peters, M. D. J., Stern, C., Tufanaru, C., McArthur, A., & Aromataris, E. (2018). Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Medical Research Methodology, 18(1), 143. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0611-x

Page, M. J., McKenzie, J. E., Bossuyt, P. M., Boutron, I., Hoffmann, T. C., Mulrow, C. D., Shamseer, L., Tetzlaff, J. M., Akl, E. A., Brennan, S. E., Chou, R., Glanville, J., Grimshaw, J. M., Hróbjartsson, A., Lalu, M. M., Li, T., Loder, E. W., Mayo-Wilson, E., McDonald, S., … Moher, D. (2021). The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ, 372(71). https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.n71

Peters, M. D. J., Godfrey, C. M., McInerney, P., Munn, Z., Tricco, A. C., & Khalil, H. (2020). Scoping reviews (2020 version). Em E. Aromataris & Z. Munn (Eds.), JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis. Joanna Briggs Institute (pp. 407-452). https://doi.org/10.46658/JBIMES-20-12

Pham, M. T., Rajić, A., Greig, J. D., Sargeant, J. M., Papadopoulos, A., & McEwen, S. A. (2014). A scoping review of scoping reviews: Advancing the approach and enhancing the consistency. Research Synthesis Methods, 5(4), 371-385. https://doi.org/10.1002/jrsm.1123

Porter, J., & Standing, K. (2020). Love island and relationship education. Frontiers in Sociology, 4, 79. https://doi.org/10.3389/fsoc.2019.00079

Sarkis, S. (2019). O Fenômeno Gaslighting: Saiba como funciona a estratégia de pessoas manipuladoras para distorcer a verdade e manter você sob controle. Editora Cultrix.

Sheikh, I. H. (1979). The misuse of psychiatry: The “Gas Light” phenomenon. The International Journal of Social Psychiatry, 25(2), 131-132. https://doi.org/10.1177/002076407902500209

Smith, C. G., & Sinanan, K. (1972). The ‘Gaslight Phenomenon’ reappears: A modification of the Ganser Syndrome. British Journal of Psychiatry, 120(559), 685-686. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.120.559.685

Stern, R. (2007). The Gaslight Effect: How to spot and survive the hidden manipulations other people use to control your life. Morgan Road Books.

Stern, R. (2019). O Efeito Gaslight: como identificar e sobreviver à manipulação velada que os outros usam para controlar sua vida. Alta Books.

Sweet, P. L. (2019). The sociology of gaslighting. American Sociological Review, 84(5), 851-875. https://doi.org/10.1177/0003122419874843

Tager-Shafrir, T., Szepsenwol, O., Dvir, M., & Zamir, O. (2024). The gaslighting relationship exposure inventory: Reliability and validity in two cultures. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 41(10), 3123-3146. https://doi.org/10.1177/02654075241266942

Tetreault, C., Bates, E. A., & Bolam, L. T. (2021). How dark personalities perpetrate partner and general aggression in Sweden and the United Kingdom. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 36(9–10), NP4743-NP4767. https://doi.org/10.1177/0886260518793992

Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467-473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850

Zhu, J., Exner-Cortens, D., Dobson, K., Wells, L., Noel, M., & Madigan, S. (2023). Adverse childhood experiences and intimate partner violence: A meta-analysis. Development and Psychopathology, 36(2), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579423000196

Como citar: Machado, M., Nunes da Fonseca, P., Guimarães Tannuss, A. D., Nascimento Dias, D. G., & Soares Pereira, R. (2025). Gaslighting em relacionamentos íntimos: uma revisão de escopo. Ciencias Psicológicas, 19(2), e-4477. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v19i2.4477

Contribuição de autores (Taxonomia CRediT): 1. Conceitualização; 2. Curadoria de dados; 3. Análise formal; 4. Aquisição de financiamento; 5. Pesquisa; 6. Metodologia; 7. Administração do projeto; 8. Recursos; 9. Software; 10. Supervisão; 11. Validação; 12. Visualização; 13. Redação: esboço original; 14. Redação: revisão e edição.

M. O. S. M. contribuiu em 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 12, 14; P. N. F. em 1, 3, 7, 10, 12, 14; A. D. G. T. em 5, 6, 12, 14; D. G. N. D. em 11, 12, 14; R. S. P. em 11, 12, 14.

Editora científica responsável: Dra. Cecilia Cracco.

10.22235/cp.v19i2.4477

Original Articles

Gaslighting in Intimate Relationships: A Scoping Review

Gaslighting em relacionamentos íntimos: uma revisão de escopo

Gaslighting en las relaciones íntimas: una revisión de alcance

Mayara de Oliveira Silva Machado1, ORCID 0000-0002-4922-4828

Patrícia Nunes da Fonseca2, ORCID 0000-0002-6322-6336

Anna Dhara Guimarães Tannuss3, ORCID 0000-0001-6945-4041

Dayane Gabrielle do Nascimento Dias4, ORCID 0000-0002-4175-0217

Rayssa Soares Pereira5, ORCID 0000-0002-9102-8951

1 Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Brazil, [email protected]

2 Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Brazil

3 Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Brazil

4 Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Brazil

5 Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Brazil

Abstract:

This study carried out a scoping review on gaslighting in intimate relationships, with the aim of analyzing how the scientific literature has studied the phenomenon in adults, without restricting the studies according to sex, gender identity or the type of affective relationship of the partners involved. The search was conducted in the databases Scopus, CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycNet, PubMed, PsycInfo and Sage Journals, and a complementary search in Google Scholar with the aim of screening out national studies not indexed in high-impact journals. The findings resulted in 14 studies considered eligible for inclusion in the main analysis. The results showed that gaslighting in intimate relationships has been investigated from seven main perspectives: risk factors and predictors, tactics or mechanisms, motivations, assessment tools, harm caused to victims, coping strategies and correlated variables of gaslighting. It is important to note that the articles selected adopted a convenience sample design, composed predominantly of female samples, which may influence the understanding of this phenomenon. In short, it is hoped that the findings of this study can contribute to the development of new research into the phenomenon, especially in the Brazilian context, and enable a discussion of intervention strategies that seek to identify, prevent and deal with this form of violence in love relationships, in order to promote healthier relationships.

Keywords: gaslighting; intimate relationships; psychological violence; scoping review.

Resumo:

Este estudo realizou uma revisão de escopo sobre o gaslighting em relacionamentos íntimos, com o objetivo de analisar como a literatura científica tem estudado o fenômeno, em adultos, sem restringir os estudos com base no sexo, identidade de gênero ou tipo de relação afetiva dos parceiros envolvidos. A pesquisa foi conduzida nas bases de dados Scopus, CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycNet, PubMed, PsycInfo e Sage Journals, e uma busca complementar no Google Acadêmico com o objetivo de rastrear estudos nacionais não indexados em periódicos de alto impacto. Os achados resultaram em 14 estudos considerados elegíveis para a inclusão na análise principal. Os resultados demonstraram que o gaslighting em relacionamentos íntimos tem sido investigado sob sete perspectivas principais: fatores de risco e preditores, táticas ou mecanismos, motivações, instrumentos de avaliação, danos causados às vítimas, estratégias de coping e variáveis correlatas do gaslighting. É importante destacar que os artigos selecionados adotaram um delineamento amostral de conveniência, composto predominantemente com amostras do gênero feminino, o que pode influenciar a compreensão deste fenômeno. Em suma, estima-se que os achados desse estudo possam contribuir para o desenvolvimento de novas pesquisas sobre o fenômeno, especialmente em contexto brasileiro e possibilitem uma discussão de estratégias de intervenção que busquem identificar, prevenir e enfrentar essa forma de violência nas relações amorosas, a fim de promover relacionamentos mais saudáveis.

Palavras-chave: gaslighting; relacionamentos íntimos; violência psicológica; revisão de escopo.

Resumen:

Este estudio realizó una revisión de alcance sobre el gaslighting en las relaciones íntimas, con el objetivo de analizar cómo la literatura científica ha estudiado el fenómeno en adultos, sin restringir los estudios en función del sexo, la identidad de género o el tipo de relación afectiva de los miembros de la pareja implicados. La búsqueda se realizó en las bases de datos Scopus, CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycNet, PubMed, PsycInfo y Sage Journals, y una búsqueda complementaria en Google Scholar con el objetivo de localizar estudios nacionales no indexados en revistas de alto impacto. Los resultados dieron lugar a 14 estudios considerados aptos para su inclusión en el análisis principal. Los resultados mostraron que el gaslighting en las relaciones íntimas ha sido investigado desde siete perspectivas principales: factores de riesgo y predictores, tácticas o mecanismos, motivaciones, herramientas de evaluación, daño causado a las víctimas, estrategias de afrontamiento y variables correlacionadas con el gaslighting. Es importante señalar que los artículos seleccionados adoptaron un diseño muestral de conveniencia, compuesto predominantemente por muestras femeninas, lo que puede influir en la comprensión de este fenómeno. En resumen, se espera que los resultados de este estudio puedan contribuir al desarrollo de nuevas investigaciones sobre el fenómeno, especialmente en el contexto brasileño, y posibilitar la discusión de estrategias de intervención que busquen identificar, prevenir y lidiar con esa forma de violencia en las relaciones amorosas, a fin de promover relaciones más saludables.

Palabras clave: gaslighting; relaciones íntimas; violencia psicológica; revisión de alcance.

Received: 13/02/2025

Accepted: 12/08/2025

In recent years, discussions about psychological violence have grown significantly (Capezza et al., 2021; Keatley et al., 2022; Martínez-González et al., 2021). A specific type of this subtle form of abuse that has stood out from others and attracted considerable attention is gaslighting. The term gaslighting has become increasingly popular and is widely used to describe abusive manipulation strategies in various interpersonal relationships (e.g., familial, romantic, or workplace), with the aim of making the victim doubt their own judgment (Gass & Nichols, 1988; Klein et al., 2023; Sweet, 2019).

The growing public interest in the topic is evidenced by the increasing number of online searches for the term, which led Merriam-Webster to select “gaslighting” as its 2022 Word of the Year (Merriam-Webster, 2022). Television programs such as the British reality show Love Island have attracted a global audience, including viewers in Brazil, have sparked online discussions (e.g., on X, Instagram, and Facebook) about intimate partner violence, specifically focusing on gaslighting. The show’s popularity, combined with its social media visibility, has contributed to the cultural dissemination of this type of abuse (Porter & Standing, 2020).

Furthermore, the subject has attracted the attention of authors and filmmakers, who have explored the topic in productions such as the films Your Reality and Captain Marvel (Hammer & Kavanaugh, 2024), in which the female protagonists experience gaslighting by their intimate partners. The theme also appears in self-help books such as The Gaslight Effect: How to Spot and Survive the Hidden Manipulation Others Use to Control Your Life (Stern, 2019) and Gaslighting: Recognize Manipulative and Emotionally Abusive People—and Break Free (Sarkis, 2019). These visual and literary representations of violence featured in films, television shows, and books have helped raise public awareness of gaslighting as a form of psychological abuse, enabling individuals to recognize these behaviors in their own lives (Ghaltakhchyan, 2024; Hammer & Kavanaugh, 2024).

In this context, the growing attention and popularity surrounding the phenomenon have also had repercussions in the legal sphere. According to Mikhailova (2018, as cited in Sweet, 2019), gaslighting was officially incorporated into domestic violence legislation in the United Kingdom in 2015, resulting in more than 300 individuals being charged with this type of abuse. In Brazil, although the term gaslighting is not yet explicitly mentioned in the legislation, the phenomenon is legally recognized as a form of psychological violence against women. As established in Law No. 14,188/2021, specifically Article 147-B of the Penal Code, criminal behaviors include manipulation, threats, ridicule, and isolation with the intent to degrade or control a woman’s behaviors, beliefs, and decisions, thereby harming her mental health and self-determination (Brazil, 2021).

Relevant data indicate that gaslighting is a central characteristic of intimate partner violence (Bhatti et al., 2023; Hailes & Goodman, 2023; Sweet, 2019), although it may also occur in intimate relationships that are not considered abusive (Klein et al., 2023; Sweet, 2019). This expands concern about the potential impact on victims’ health and well-being. Moreover, evidence suggests that psychological violence may be more harmful and have longer-lasting effects than physical violence (Hester et al., 2017), highlighting the urgency of addressing it as a public health issue.

Given the relevance of the topic, it is essential to conduct studies that contribute to a deeper understanding of the phenomenon, particularly in the context of romantic relationships, which are often reported as the most common interpersonal setting in which this type of abuse occurs (Akdeniz & Cihan, 2023; Stern, 2007).

Gaslighting: “Which One of Us is Crazy?”

Gaslighting is currently defined as a form of psychological abuse in which one person manipulates another’s judgment, causing them to question their mental capacity to perceive reality (Abramson, 2014; Calef & Weinshel, 1981; Sweet, 2019). This phenomenon involves two agents: the perpetrator, referred to as the gaslighter, who employs tactics such as lying, denial, and concealment; and the victim, often called the gaslightee, who begins to doubt their own ability to perceive, judge, and make decisions about their experiences (Calef & Weinshel, 1981; Hailes & Goodman, 2023; Sweet, 2019). However, the concept has not always been defined this way, and its understanding has evolved over time.

The term gaslighting originated from the 1938 play and subsequent film Gaslight, written by Patrick Hamilton. The story portrays an abusive relationship in which a woman is led to believe she is going insane due to manipulations by her husband, who plans to have her institutionalized in order to steal her inheritance (Calef & Weinshel, 1981; Kutcher, 1982). Gregory, the husband, communicates with his wife Paula in a controlling and ambiguous manner, creating situations that lead her to question her own perceptions of reality. One of the methods he uses to confuse her involves dimming the gaslights, hence the title of the work, and denying any change in the lighting, accusing her of imagining things (Calef & Weinshel, 1981; Sweet, 2019).

Following this popular portrayal, similar patterns of manipulative behavior began to be observed in various social contexts, prompting scientific investigations into the phenomenon (Calef & Weinshel, 1981; Kutcher, 1982). The earliest accounts in the literature appeared in the 1960s and 1970s (Barton & Whitehead, 1969; Sheikh, 1979; Smith & Sinanan, 1972), describing gaslighting as the perpetrator’s attempt to convince third parties, especially psychiatrists, that the victim had mental disorders that rendered them unfit for social life. At the time, gaslighting was viewed as a deliberate act motivated by personal or financial gain or as a way to resolve family problems, and little to no attention was given to the victim (Barton & Whitehead, 1969; Sheikh, 1979).

In the 1980s, a significant shift occurred in how gaslighting was described and understood. Researchers began to define it as a process in which the perpetrator no longer sought to deceive others, but rather the victim themselves, convincing them of their cognitive inability to comprehend and deal with everyday situations (Calef & Weinshel, 1981; Kutcher, 1982), which remains the dominant understanding today. Despite this conceptual shift, behaviors associated with gaslighting have been present since Hamilton’s play, including deceptive and insidious acts of manipulation such as denying facts the victim has reason to believe, distorting reality, assigning undue blame, and using verbal insults to undermine the victim’s mental state (Hailes & Goodman, 2023; Klein et al., 2023; Sweet, 2019).

Although women can also employ abusive gaslighting tactics against men (Graves & Samp, 2021; Stern, 2007; Tager-Shafrir et al., 2024), gaslighting is frequently associated with gender-based violence, with most studies portraying men as perpetrators and women as victims (Abramson, 2014; Bhatti et al., 2023; Sweet, 2019). Early studies reported cases in which husbands with extramarital affairs used tactics such as lies and accusations to confuse their wives, often relying on sexist stereotypes, e.g., “women are overreactive,” “jealous,” and “emotional,” to invalidate women’s feelings and perceptions (Calef & Weinshel, 1981; Gass & Nichols, 1988).

In this context, research has emphasized that gaslighting is rooted in gender stereotypes. As a result, verbal insults such as “slut,” “crazy,” and “hysterical” are frequently used to delegitimize women’s beliefs, judgments, and behaviors (Boring, 2020; Sweet, 2019). Although gaslighting shares characteristics with psychological violence and coercive control, it is distinguished by its primary goal: to undermine the victim’s self-confidence so they accept the reality imposed by the perpetrator (Abramson, 2014; Sweet, 2019).

Given the various impacts this behavior can produce, some studies have sought to investigate the motivations of perpetrators and the consequences for gaslighting victims (Calef & Weinshel, 1981; Klein et al., 2023). Although it can be difficult to determine the intention behind these actions, different studies show that the perpetrator’s motivation may be either conscious, driven by personal or financial gain, or unconscious, stemming from psychological disorders, a need to control the partner, or a desire to avoid accountability for their actions (Bashford & Leschziner, 2015; Calef & Weinshel, 1981; Klein et al., 2023). In this regard, the literature suggests that aversive personality traits, such as psychoticism, sadism, Machiavellianism, and narcissism, may be linked to gaslighting behaviors (March et al., 2023; Miano et al., 2021).

Victims of gaslighting report long-lasting emotional harm, with negative impacts on health and well-being that persist even after the end of the abusive relationship (Hailes & Goodman, 2023; Klein et al., 2023). Studies highlight loss of self-confidence, feelings of confusion, doubt about memory and perception of reality, and self-perceptions of being “crazy.” While some victims report being able to overcome the trauma after the relationship ends, others experience a slower recovery, with emotional consequences (e.g., sadness, guilt, a sense of helplessness) and social consequences (e.g., difficulty trusting others, isolation, and lower relationship quality) that may persist over time (Hailes & Goodman, 2023; Klein et al., 2023).

Given the notable public attention and growing academic interest in gaslighting, it is important to understand how scientific studies have addressed the topic, especially in romantic relationships, where such abuse is particularly common (Akdeniz & Cihan, 2023; Stern, 2007). Thus, the general objective of this study was to analyze how the scientific literature has examined gaslighting in intimate relationships. Specifically, the study aims to: (1) identify predictors of gaslighting; (2) examine gaslighting tactics or mechanisms; (3) explore the motivations behind the perpetration of gaslighting; (4) identify instruments used to assess gaslighting; (5) investigate coping strategies adopted by victims of gaslighting; and finally, (6) identify variables associated with gaslighting.

Method

This exploratory study conducted a scoping review of national and international publications on the phenomenon of gaslighting in intimate relationships. A scoping review is a rigorous and transparent method that aims to map the existing literature in a specific area, allowing for both the analysis of research characteristics and the identification of gaps in the available literature (Munn et al., 2018). It is important to note that this type of review does not include the assessment of the methodological quality of the studies analyzed (Pham et al., 2014). The scoping review conducted in this study followed the methodological guidelines proposed by the Joanna Briggs Institute (Aromataris et al., 2020) and the checklist Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR; Page et al., 2021; Tricco et al., 2018). This review was also registered on the Open Science Framework platform and can be accessed via the following DOI https://doi.org/10.17605/OSF.IO/Z7RCW.

Search Strategy

This review aimed to answer the following question: How has the scientific literature addressed gaslighting in intimate relationships? To guide the research process, the PCC framework (Population, Concept, and Context) was applied. The population comprised individuals aged 18 and older; the concept focused on studies examining the phenomenon of gaslighting; and the context was restricted to intimate relationships.

As this was a scoping review, no restrictions were applied regarding participants’ sex, gender identity, or type of romantic relationship. This decision was based on the exploratory nature of scoping reviews (Peters et al., 2020). This strategy aimed to provide a broader overview of how gaslighting has been conceptualized, studied, and discussed in the scientific literature, enabling the identification of knowledge gaps and informing future studies with more specific scopes.

The search strategy covered the period from September 2023 to August 2024 and included the following databases: Scopus, CINAHL, MEDLINE, PsycNet, PubMed, PsycInfo, and Sage Journals. No publication date restrictions were applied, in order to capture the full body of scientific literature available on gaslighting in intimate relationships. Search techniques were developed to be applicable across all databases, using the following keyword strategy: (relationships OR "intimate relationships" OR "interpersonal relationships" OR "romantic relationship") AND ("gasli" OR "gaslight" OR "gaslighted" OR "gaslit" OR "gaslights" OR "gaslighting")*, considering both abstracts and titles.

Eligibility Criteria

The inclusion criteria for selecting studies were as follows: empirical scientific articles that (1) involved research studies, interventions, case reports, or experiential accounts; (2) were published at any time; (3) addressed gaslighting in intimate relationships; (4) included samples composed of individuals aged 18 or older; (5) were available via open or restricted access; (6) were written in any language; and (7) were conducted in any country.

Exclusion criteria included documents meeting at least one of the following conditions: (1) titles, abstracts, or full texts unrelated to gaslighting in intimate relationships; (2) publications in the form of book chapters, reviews, theses, dissertations, or theoretical studies; (3) samples including participants under 18 years of age; and (4) full texts not available.

Data Extraction and Synthesis

This scoping review was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) guidelines. The PRISMA flowchart detailing the article selection process is presented in Figure 1. Metadata from the articles identified in the selected databases were exported in Research Information Systems (RIS) format. To ensure comprehensive coverage, previous reviews on the topic were also consulted, and backward and forward citation tracking strategies were applied (Haddaway et al., 2022). Additionally, a supplementary search was conducted on Google Scholar to identify non-indexed national studies.

All metadata were imported into Rayyan, a software developed by the Qatar Computing Research Institute, where duplicate records were removed. Study selection and screening were independently conducted by two reviewers across the stages of title and abstract screening, eligibility assessment, and final inclusion. In cases of disagreement, alignment meetings were held, and, when necessary, a third reviewer was consulted to ensure impartiality and rigor. Articles deemed relevant were subjected to full-text content analysis.

Results

Study Selection Results

The initial search across the Medline, CINAHL, Scopus, PsycInfo, PsycNet, PubMed, and Sage Journals databases yielded 295 records (Figure 1). After removing duplicates, 251 records remained. Of these, 212 were excluded based on title and abstract screening, and 8 were excluded for not meeting the inclusion criteria. Among the remaining 31 full-text articles assessed, 9 were included in the final review. Additionally, findings from previous reviews identified four more studies. The complementary searches conducted during the review process generated 125 results, from which 13 studies were fully assessed, and 12 were excluded. This process resulted in a final inclusion of 14 studies considered eligible for the main analysis.

Figure 1: Flowchart of Study Screening and Inclusion

Characteristics of the Studies

In terms of time frame, the year 2023 stood out with the highest number of publications, totaling four articles. This was followed by 2021 with three articles and 2024 with two publications. The years 1981, 1982, 2015, 2019, and 2022 each had only one study. No eligible publications were found between 1983 and 2014 or in the years 2016, 2017, and 2018.

Regarding geographic origin, most of the articles were from the United States (n = 5). Other contributions came from Canada (n = 2), Italy (n = 2), Pakistan (n = 2), England (n = 1), Ireland (n = 1), Israel (n = 1), and Australia (n = 1). Notably, one study (Tager-Shafrir et al., 2024) was conducted simultaneously in two countries, Israel and the United States.

As for the type of scientific production, all selected articles were published in English and adopted convenience sampling, predominantly with female participants. Most studies used a cross-sectional design. Seven studies employed qualitative methodologies, using instruments such as case reports (n = 4), interviews (n = 2), and questionnaires with open-ended questions (n = 1). In contrast, eight studies used quantitative methods, relying on self-report instruments (e.g., Revised Conflict Tactics Scale, Aggression Questionnaire, Multidimensional Measure of Emotional Abuse) to analyze antecedent and consequent variables associated with gaslighting. Among these, five studies conducted psychometric analyses to validate specific instruments for assessing gaslighting, including the Victim Gaslighting Questionnaire (VGQ; Bhatti et al., 2023), the Gaslight Questionnaire (Stern, 2007) adapted by Hassan et al. (2022), the Gaslighting Behaviour Questionnaire (GBQ; Dickson et al., 2023), the Gaslighting Questionnaire (March et al., 2023), and the Gaslighting Relationship Exposure Inventory (GREI; Tager-Shafrir et al., 2024).

Summary of the Selected Evidence Sources

Table 1 presents a synthesis of the studies mapped according to the objectives of this scoping review.

Table 1: Summary of the Studies

Analyzed Content

Based on the findings of the selected studies, the following categories of analysis were identified: (1) risk factors and predictors of gaslighting, (2) gaslighting tactics or mechanisms, (3) motivations for perpetrating gaslighting, (4) assessment instruments for gaslighting, (5) harm caused to victims of gaslighting, (6) coping strategies adopted by victims of gaslighting, and (7) variables associated with gaslighting. It is important to note that some articles were included in more than one category of analysis, as detailed in Table 2.