Ciencias Psicológicas; v19(2)

julio-diciembre 2025

10.22235/cp.v19i2.4199

Construcción y evidencias de validez y confiabilidad de una escala de retroalimentación docente percibida

Construction and Evidence of Validity and Reliability of Perceived Teacher Feedback Scale

Construção e evidências de validade e confiabilidade de uma escala de percepção do feedback do professor

Ricardo Navarro Fernández1, ORCID 0000-0002-7069-9780

Diana Alexandra Arizaga Castro2, ORCID 0000-0003-1977-341X

Hugo Bayona Goycochea3, ORCID 0000-0002-2555-4670

1 Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Perú

2 Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Perú, [email protected]

3 Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Perú

Resumen:

La retroalimentación docente es una herramienta importante para el proceso de aprendizaje; sin embargo, la percepción que los estudiantes tienen sobre este fenómeno no es abordada en el contexto educativo, especialmente en el de Educación Superior. El objetivo del presente estudio es diseñar y validar una escala psicométrica que mide la percepción de estudiantes universitarios sobre la retroalimentación docente. La muestra del estudio estuvo conformada por 418 estudiantes universitarios entre 18 y 30 años. Se realizó el análisis de validez de contenido mediante jueces expertos, así como análisis de validez interna mediante el uso de análisis factorial exploratorio. También se reportan los análisis de consistencia interna. Los resultados muestran excelentes índices de ajuste. Los coeficientes de confiabilidad fueron mayores a .87 en todas las dimensiones. Los resultados obtenidos permiten argumentar el uso del instrumento para medir la retroalimentación docente percibida por los estudiantes en la educación superior.

Palabras clave: retroalimentación; psicometría; educación superior; análisis factorial.

Abstract:

Teacher feedback is an important tool for the learning process; however, the perception that students have about this phenomenon is not addressed in the educational context, especially in higher education. Thus, the aim of this study is to design and validate a psychometric scale that measures university students' perception of teacher feedback. The study sample consisted of 418 university students between 18 and 30 years of age. Content validity analysis was carried out by expert judges, as well as internal validity analysis using exploratory factor analysis. Internal consistency analyses are also reported. The results show excellent fit indices. Reliability coefficients were greater than .87 in all dimensions. The results obtained allow arguing the use of the instrument to measure teacher feedback perceived by students in higher education.

Keywords: feedback; psychometry; higher education; factor analysis.

Resumo:

O feedback docente é uma ferramenta importante para o processo de aprendizagem; no entanto, a percepção que os estudantes têm sobre esse fenômeno não é abordada no contexto educativo, especialmente no Ensino Superior. Assim, o objetivo do presente estudo é conceber e validar uma escala psicométrica que mede a percepção de estudantes universitários sobre o feedback docente. A amostra do estudo foi composta por 418 estudantes universitários com idades entre 18 e 30 anos. Realizou-se a análise de validade de conteúdo por meio de juízes especialistas, bem como a análise de validade interna por meio de análise fatorial exploratória. Também são reportadas as análises de consistência interna. Os resultados revelam excelentes índices de ajuste. Os coeficientes de confiabilidade foram superiores a 0,87 em todas as dimensões. Os resultados obtidos permitem sustentar o uso do instrumento para medir o feedback docente percebido pelos estudantes no ensino superior.

Palavras-chave: feedback; psicometria; ensino superior; análise fatorial.

Recibido: 02/08/2024

Aceptado: 27/08/2025

La retroalimentación docente es una práctica pedagógica clave que influye significativamente en el aprendizaje de los estudiantes, ya que orienta, refuerza o reestructura su desempeño a través de información sobre sus tareas, procesos o actitudes (Anijovich, 2018; Clark, 2012; Hattie & Timperley, 2007). Esta puede ser materializada de distintas maneras, pero usualmente es presentada mediante observaciones que sustentan una calificación (Wisniewski et al., 2020). En ese sentido, se espera que las observaciones del docente faciliten que el estudiante identifique sus errores, así como sugerir alternativas de solución, estrategias y metas sobre aquello que fue revisado (Brinko, 1993). Como práctica pedagógica, esta se configura como una herramienta de andamiaje con el fin de facilitar que los estudiantes reflexionen sobre su desempeño y alcancen sus objetivos académicos (Anijovich, 2018; Bazán-Ramírez et al., 2022; Lipnevich & Panadero, 2021).

Sin embargo, no toda retroalimentación tiene efectos iguales. En ocasiones puede facilitar la comprensión y la autorregulación, y en otras ser más bien disfuncional, como cuando se limita a corregir errores sin orientar mejoras (Guo & Wei, 2019). Existen diferentes tipologías de retroalimentación en la literatura (Guo, 2020; Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Lipnevich & Panadero, 2021; Moreno, 2023; Wisniewski et al., 2020). La literatura distingue múltiples tipologías que abarcan desde el foco de la retroalimentación (producto, proceso, autorregulación) hasta su forma (extensión, calidad o tono afectivo) (Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Wisniewski et al., 2020). En los últimos años, autores como Guo (2020) han propuesto una delimitación más compleja que tiene en cuenta la calidad del mensaje brindado al estudiante, así como información relacionada a características complementarias a la actividad académica. Guo (2017, 2020) plantea la retroalimentación como parte del proceso de andamiaje, además de rescatar la importancia de comentarios hacia las características del estudiante.

En base en la literatura revisada, se puede clasificar la retroalimentación docente en cuatro tipos: retroalimentación formativa, retroalimentación ineficaz, elogio hacia el estudiante y crítica hacia el estudiante (Guo, 2020; Guo & Wei, 2019; Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Lipnevich & Panadero, 2021; Wisniewski et al., 2020).

La retroalimentación formativa hace referencia a la información positiva hacia el contenido o a la información que el docente provee sobre los logros y desafíos en que una tarea puede ser mejorada. Esto ocurre, por ejemplo, cuando el docente escribe comentarios, brinda indicaciones claras o formula preguntas acerca de los resultados (Mollo & Deroncele, 2022). De esta forma, la retroalimentación facilita y exhorta a la reflexión en el alumnado asociado a sus objetivos de aprendizaje (Anijovich, 2018; Hernández et al., 2024; Luna et al., 2022).

Por el contrario, la retroalimentación ineficaz hace referencia a una retroalimentación insuficiente hacia el contenido de una actividad presentada por los estudiantes. Así, los comentarios que realiza el docente sobre los trabajos del estudiante sin centrarse en su aprendizaje, como cuando solo se señala el error, se corrige y se otorga una puntuación a la tarea o examen.

En el caso de elogio al estudiante, se hace referencia a la retroalimentación positiva hacia el desempeño del estudiante. Este tipo de retroalimentación abarca los elogios que el docente realiza con el propósito de afectar la autoestima del alumnado y provocar mejoras en sus aprendizajes, tal y como lo propone Guo (2017, 2020). El elogio es una estrategia factible y no intrusiva en el aula que pueden utilizar fácilmente los docentes de diferentes niveles educativos (Criss et al., 2024; Jenkins et al., 2015). De esta manera, el elogio puede ser considerado una estrategia en el aula dependiendo del resultado en la conducta de los estudiantes (Partin et al., 2009), porque, por lo general, hace que los estudiantes se sientan reforzados (Moffat, 2011).

Por último, la crítica hacia el estudiante refiere a la información negativa hacia el desempeño del estudiante. Esta engloba las críticas o comentarios negativos de los profesores a las actitudes, comportamientos o desempeño de aprendizaje de un estudiante a través de expresiones de disgusto, desaprobación o rechazo (Brophy, 1981; Guo et al., 2019; Hyland, 2000 en Hyland & Hyland, 2001). Usualmente, estos se brindan a estudiantes que presentan un bajo desempeño, por lo que es una aproximación de presión, control y dominancia por parte de los docentes (Aelterman et al., 2019). Estas críticas normalmente son por descuido o escaso esfuerzo, o afirmar que son capaces de hacer un mejor trabajo.

En particular, la retroalimentación formativa ha mostrado ser más eficaz que otras formas como la retroalimentación correctiva, los elogios indiscriminados o los castigos, dado que proporciona información útil para mejorar el desempeño futuro (Anijovich, 2018; Burga et al., 2023). En cambio, los elogios, los castigos, las recompensas y la retroalimentación correctiva tienen efectos bajos o bajos a medios en promedio (Anijovich, 2018) y pueden afectar negativamente la motivación, el autoconcepto académico y la experiencia en el aula (Ansari & Usmani, 2018; Brandmo & Gamlem, 2025; Ceccarelli, 2014).

En el Perú, la política educativa prioriza la evaluación del aprendizaje y el logro de la calidad educativa, a través de documentos normativos como el Marco de Buen Desempeño Docente (Ministerio de Educación [Minedu], 2012) y el Currículo Nacional de Educación Básica (Minedu, 2016). Inclusive, en el marco de la evaluación del desempeño docente se evalúa el monitoreo realizado por el docente al trabajo de los estudiantes y la posterior calidad de la retroalimentación brindada (Minedu, 2025a). Sin embargo, evidencia proporcionada por el Monitoreo de Prácticas Escolares (MPE) indica que solo el 1 % de docentes de educación básica se encuentran en un nivel efectivo de evaluación formativa (Minedu, 2025b). Por lo tanto, la gran mayoría de docentes suele brindar retroalimentación superficial, donde solo se señala la respuesta correcta sin proporcionar información sobre cómo mejorar.

Además, a pesar de la importancia dada desde el ámbito regulador, este fenómeno ha sido estudiado casi exclusivamente por tesis de pregrado que evalúan retroalimentación formativa en estudiantes universitarios con cuestionarios de autorreporte para realizar un cruce con variables de desempeño (Altez, 2021; Boyco, 2019; Calvo, 2018; Uchpas, 2020) o artículos de opinión sobre la importancia de la evaluación formativa y la retroalimentación (Beriche Lezama & Medina Zuta, 2021; Bizarro et al., 2019; Espinoza-Freire, 2021). Esto implica una brecha en la generación de conocimiento acerca de la retroalimentación docente en el país.

Cabe señalar que los docentes y los estudiantes no siempre comparten una visión común sobre la retroalimentación ofrecida en el proceso educativo. Estudios previos han demostrado que los docentes tienden a sobreestimar la claridad, utilidad y frecuencia de la retroalimentación que brindan, mientras que los estudiantes a menudo perciben que esta es insuficiente, poco específica u orientadora para su mejora (Benson-Goldberg & Erickson, 2021; Dawson et al., 2019). Esta disonancia en las percepciones representa un obstáculo para el propósito formativo de la retroalimentación, pues lo que realmente impacta en el aprendizaje es la manera en que los estudiantes interpretan, procesan y utilizan la información recibida (Carless & Boud, 2018).

Desde esta perspectiva, evaluar la retroalimentación solo desde la óptica del docente resulta limitado, ya que deja de lado la experiencia de quienes son sus principales destinatarios. Así, se destaca la necesidad de situar al estudiante en el centro del proceso evaluativo, reconociendo su rol activo en la interpretación de los mensajes pedagógicos y en la construcción de significados a partir de ellos (Carless & Boud, 2018; Mollo & Deroncele, 2022). Además, considerar su percepción permite identificar si la retroalimentación realmente cumple con funciones claves como clarificar expectativas, guiar la mejora y fomentar la autorregulación (Hernández et al., 2024; Lipnevich & Panadero, 2021).

Por ello, contar con instrumentos válidos y confiables que recojan de manera sistemática las percepciones estudiantiles sobre los diferentes tipos de retroalimentación docente es crucial para cerrar la brecha entre la intención del docente y el efecto real sobre el aprendizaje. Ante este panorama, el objetivo general del presente estudio fue diseñar y validar un instrumento psicométrico que permita medir la percepción estudiantil sobre los tipos de retroalimentación docente en la educación superior. Este instrumento considera cuatro dimensiones teóricas derivadas de la literatura: retroalimentación formativa, retroalimentación ineficaz, elogios hacia el estudiante y críticas hacia el estudiante (Guo & Wei, 2019; Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Lipnevich & Panadero, 2021).

La contribución principal de este estudio radica en ofrecer una herramienta válida y contextualizada para investigar las prácticas de retroalimentación en el nivel superior desde la perspectiva del estudiantado. A diferencia de investigaciones previas centradas en la retroalimentación docente en contextos escolares o anglosajones, este estudio aporta evidencia empírica y conceptual desde un enfoque universitario y latinoamericano para abordar vacíos en la comprensión de cómo los estudiantes interpretan la retroalimentación que reciben en instituciones de dicha región. Este aporte es relevante para el campo de la investigación educativa, pues permitirá evaluar críticamente las prácticas docentes desde la perspectiva del estudiante, informar procesos de formación docente inicial y continua, y diseñar estrategias pedagógicas más efectivas y equitativas en contextos universitarios.

Método

Participantes

La muestra fue elegida mediante un muestreo intencional no probabilístico y estuvo conformada por 418 estudiantes universitarios, cuyas edades oscilan entre 18 y 30 años (M = 20.87, DE = 2.33), 147 (35.2 %) participantes se identificaron como hombres y 271 (64.8 %), como mujeres. Asimismo, 223 (53.34 %) de los participantes provienen de la ciudad de Lima, mientras que 195 (46.65 %) provienen de la ciudad de Arequipa. Por otro lado, 216 (51.67 %) estudiantes provenían de una universidad privada, mientras que 202 (48.33 %) son de una universidad pública. Se tuvo como criterios de inclusión que los estudiantes sean mayores de edad (18 años o más) y estuviesen matriculados durante el trabajo de campo, así como durante el ciclo previo. También se tuvo en consideración que la totalidad de los cursos que hayan estado llevando sea de modalidad presencial.

Medición

Cuestionario de Percepción de Retroalimentación Docente (CPRD). El instrumento fue creado a partir de los estudios de Guo et al. (2019), Guo (2020), Ramaprasad (1983) y Wisniewski et al. (2020), así como la evidencia psicopedagógica que existe sobre las evaluaciones sumativas y formativas (Anijovich, 2018; Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Ishaq et al., 2020). El instrumento posee 21 ítems, los cuales se responden en una escala tipo Likert de 1 (Completamente en desacuerdo) a 5 (Completamente de acuerdo), con la siguiente consigna: “A continuación, se te presenta una serie de aseveraciones sobre tu experiencia en el salón de clases. No hay respuestas correctas ni incorrectas, por lo que responde de manera sincera”. Los ítems se agrupan en cuatro dimensiones según la evidencia teórica y empírica:

- Retroalimentación formativa: hace referencia a la percepción del participante sobre los comentarios constructivos que el docente provee sobre la calidad de una tarea o actividad realizada. Por ejemplo, el ítem 5 indica “La retroalimentación que da mi profesor(a) permite reflexionar sobre aquello que debo mejorar en mis tareas”. Esta va más allá de la calificación o la verificación de bien o mal, por lo cual el estudiante posee la sensación de andamiaje en su aprendizaje. Está conformada por 6 ítems.

- Retroalimentación ineficaz: se mide la percepción que el estudiante tiene sobre la retroalimentación del docente sobre el contenido evaluado. Por ejemplo, el ítem 13 “Mi profesor(a) solamente coloca el puntaje final en lugar de corregir cada pregunta de una evaluación”. En ese sentido, esta dimensión evalúa si la retroalimentación se basa en críticas que no apoyan al aprendizaje del estudiante, siendo más críticas sin relación con el contenido evaluado. Está conformada por 6 ítems.

- Elogio hacia el estudiante: se aborda la percepción que el participante tiene sobre los comentarios del docente acerca de la calidad de sus habilidades o desempeño. La retroalimentación se da en término de qué tan bien se desempeña su persona en el entorno académico. Por ejemplo, el ítem 10 indica “Mi profesor(a) hace comentarios positivos hacia un estudiante cuando tiene calificaciones sobresalientes.” Está conformada por 5 ítems.

- Crítica hacia el estudiante: se mide la percepción del estudiante tiene sobre la retroalimentación del docente hacia su desempeño. En ese sentido, esta dimensión evalúa si la retroalimentación no está relacionada directamente con la tarea evaluada, siendo más una crítica hacia el estudiante y sus habilidades. Por ejemplo, el ítem 19 “Cuando alguien saca una mala nota en un examen, mi profesor(a) da a entender que era esperable para este estudiante”. Está conformada por 4 ítems.

Procedimiento

A partir de referencias bibliográficas relevantes sobre retroalimentación docente, sobre todo los estudios de Guo et al. (2019), Guo (2020), Wisniewski et al. (2020), Hattie y Timperley (2007), Ishaq et al. (2020) y Anijovich (2018), se diseñaron los ítems del instrumento. Los estudios de Guo et al. (2019), Guo (2020) y Wisniewski et al. (2020) permitieron identificar instrumentos psicométricos previos y su evidencia en contextos educativos universitarios, los cuales suelen ser los más utilizados en el tema de retroalimentación docente actualmente. Mientras que los estudios de Hattie y Timperley (2007), Ishaq et al. (2020) y Anijovich (2018) permitieron delimitar una estructura teórica que es utilizada en otros estudios sobre retroalimentación docente, especialmente en la estructura de las dimensiones planteadas para el presente instrumento. Esto permitió establecer un marco de referencia sobre los tipos de retroalimentación que puede dar el docente, vinculándolo con los conceptos de evaluación sumativa y formativa. Luego, se procedió a diseñar un instrumento basado en la teoría, conformado inicialmente por 25 ítems. Para ello, se contó con la ayuda de especialistas en educación y psicopedagogía, quienes revisaron y apoyaron en el proceso de redacción de ítems.

A continuación, se procedió a realizar la validez de contenido mediante jueces expertos en el tema. Para ello, se consideró evaluar la coherencia de los ítems. Esto requirió contactar con 3 expertos (con al menos 5 años de experiencia en la docencia y en el diseño de evaluaciones formativas y sumativas), quienes revisaron y evaluaron los ítems y respondieron a un cuestionario donde 1 es que acepta el ítem y 0 que no acepta el ítem.

Una vez analizadas las evidencias de validez de contenido, se procedió con el trabajo de campo desde noviembre del 2023 hasta febrero del 2024, realizado de manera virtual, compartiendo el código QR del protocolo de investigación. El protocolo estaba conformado por las siguientes partes: consentimiento informado, datos sociodemográficos y el cuestionario de retroalimentación docente. El participante debía leer el consentimiento informado y, luego, aceptar participar para poder seguir llenando el protocolo. De lo contrario, el protocolo se cerraba automáticamente agradeciendo el apoyo del participante. Asimismo, si el participante tenía menos de 18 años, también se cerraba automáticamente. Finalmente, se procedió con la aplicación del protocolo, donde se le informaba al participante, previo a escanear el código QR, que la participación era voluntaria. La información fue recogida en Google Form y se digitalizó la base de datos en el software estadístico Rstudio.

Análisis de datos

Para la validación de contenido, se recurrió al juicio de tres expertos calificados en el tema de retroalimentación docente. Se utilizó el coeficiente de Kappa y el de Kendall para analizar el acuerdo entre los jueces. Adicionalmente, se consideró el porcentaje de acuerdo entre los jueces para decidir si se eliminaban o aceptaban ítems.

Luego, se analizaron los datos

descriptivos de los ítems del instrumento y se reportaron media, desviación

estándar, asimetría y curtosis. Asimismo, se realizó un análisis factorial

exploratorio (AFE) para identificar la estructura factorial del instrumento

construido. Para este estudio, y guiados por la teoría, se plantea el uso de un

análisis paralelo para identificar posibles dimensiones en las que se agrupan

los ítems, utilizando la función fa.parallel del paquete psych en

Rstudio. Se utilizó Oblimin como método de rotación para el AFE, pues las

dimensiones están relacionadas, y como método de extracción se utilizó el de

Residuos Mínimos (minres). Los índices de ajuste utilizados fueron ![]() <

3, CFI y TLI > .92, RMSEA < .07 (Hair et al., 2009). Para el

presente estudio, se utilizó la propuesta de Hair et al. (2009) para la

interpretación de las cargas factoriales, que propone un punto de corte de .35

para muestras mayores de 250 participantes. Si bien existen autores que

sugieren un punto de corte más grande (e. j., 0.4-0.5), la propuesta de Hair et

al. (2009) suele ser la más utilizada y citada en análisis psicométricos.

<

3, CFI y TLI > .92, RMSEA < .07 (Hair et al., 2009). Para el

presente estudio, se utilizó la propuesta de Hair et al. (2009) para la

interpretación de las cargas factoriales, que propone un punto de corte de .35

para muestras mayores de 250 participantes. Si bien existen autores que

sugieren un punto de corte más grande (e. j., 0.4-0.5), la propuesta de Hair et

al. (2009) suele ser la más utilizada y citada en análisis psicométricos.

Finalmente, se realizó un análisis de confiabilidad (coeficiente omega) para cada dimensión del instrumento. Para ello, se utilizarán los puntos de cortes propuestos por Kalkbrenner (2024), quien sugiere que debe tener valores mayores a .65 para ser considerados aceptables; pero se espera un coeficiente mayor a .90 en instrumentos que evalúan aspectos personales.

Consideraciones éticas

El protocolo de investigación fue aprobado por el Comité de Ética de la Investigación para Ciencias Sociales, Humanas y Artes de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú (063-2023-CEI-CCSSHHyAA/PUC).

Resultados

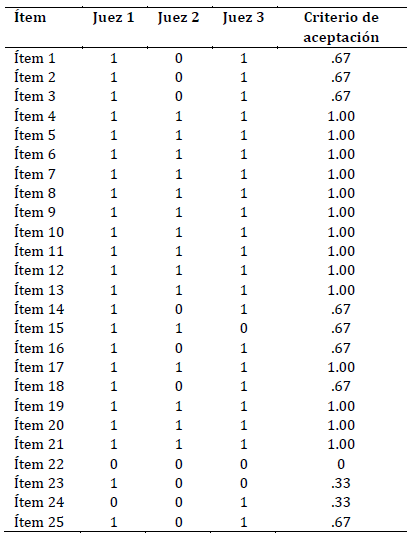

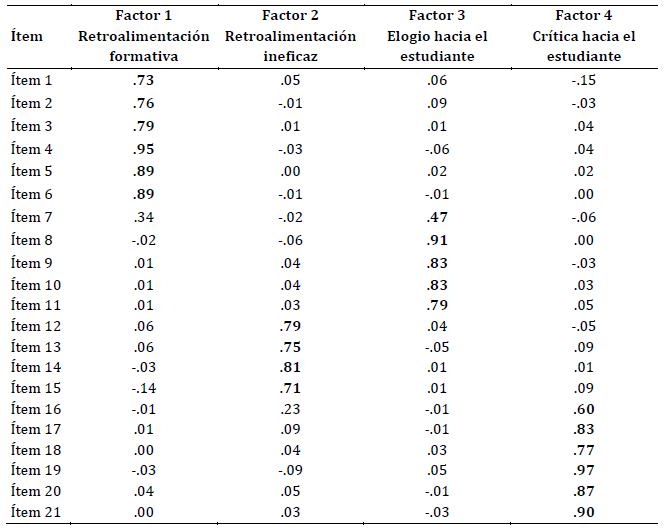

En primer lugar, se reportan los resultados de la validez de jueces para cada ítem. En la Tabla 1 se presentan las respuestas de los jueces, donde 1 es que acepta el ítem y 0 que no acepta el ítem. A partir de los resultados, se aceptan los ítems que son calificados positivamente por al menos dos jueces.

Tabla 1: Validez de contenido en función de la coherencia del ítem

Se observa que la mayoría de los ítems fueron aceptados por los tres jueces. Adicionalmente, se calculó el coeficiente de Kappa para la interpretación de resultados de los jueces, donde se obtuvo un ‑.125, que es un coeficiente por debajo de lo esperado para considerar un acuerdo entre los jueces. También se complementa el análisis con el coeficiente W de Kendall (utilizado para respuestas ordinales), que obtuvo un .248, el cual indica un acuerdo pequeño o leve.

Se identificaron 3 ítems cuyos valores eran muy bajos en la calificación de los jueces, por lo que se decidió eliminarlos, debido a que no eran adecuados ni coherentes con el constructo que se mide. Adicionalmente, el último ítem (“La retroalimentación que brinda mi profesor(a) suele enfocarse en que los estudiantes no son tan inteligentes para sacar mejores notas en su curso”) poseía el acuerdo de 2 de los jueces; sin embargo, uno de los jueces hizo una observación importante sobre el ítem: “Creo que aquí el ítem se enfoca en creencias específicas, lo cual escapa a la definición de la dimensión brindada”, por lo que se decidió eliminarlo también.

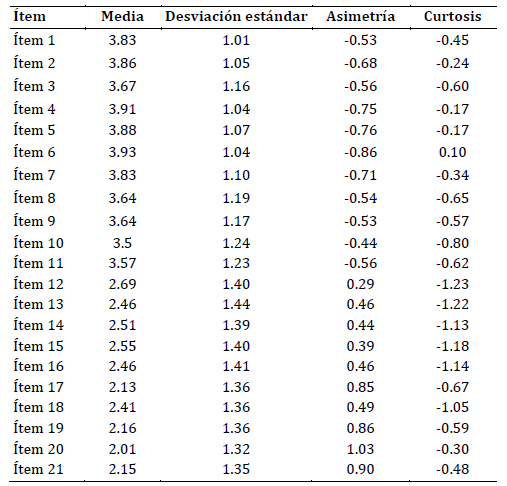

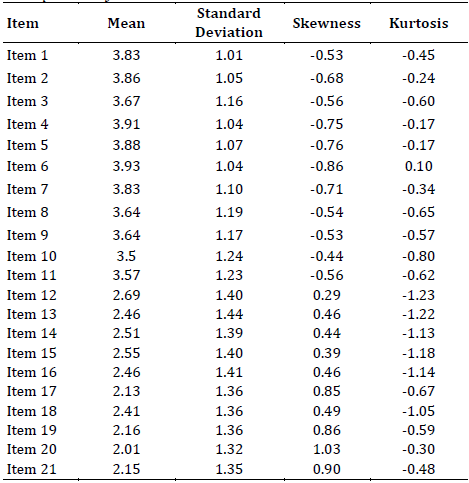

En la Tabla 2 se presentan los resultados descriptivos de los 21 ítems. La normalidad multivariada fue evaluada mediante la prueba de Henze-Zirkler (HZ), la cual mostró resultados significativos (HZ = 3.65, p < .001), lo que indica que los datos no siguen una distribución normal multivariada.

Según los resultados del AFE, el test de esfericidad de Bartlet es significativo (p < .001) y el KMO (0.93) aceptable. Para determinar el número óptimo de factores a retener se realizó un análisis paralelo utilizando 100 simulaciones aleatorias. Se empleó una matriz de correlaciones policóricas debido a la naturaleza ordinal de los ítems.

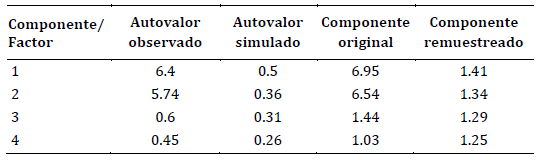

Tabla 2: Análisis descriptivos

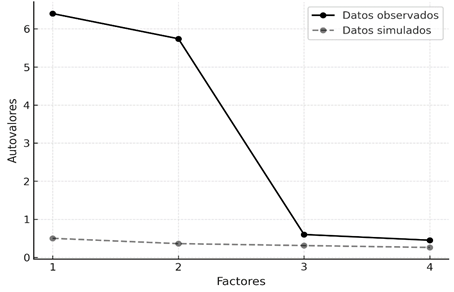

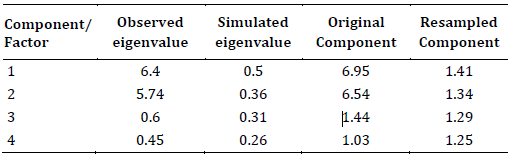

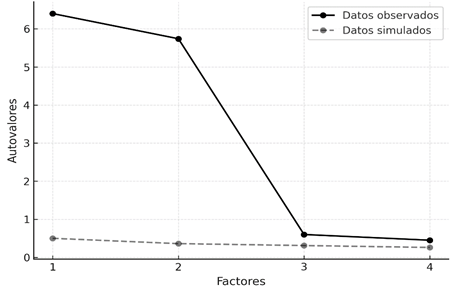

Los resultados indicaron que los cuatro primeros autovalores reales de los factores fueron mayores que los correspondientes autovalores generados aleatoriamente, lo cual sugiere la retención de cuatro factores en el AFE (Tabla 3). Estos hallazgos se complementaron con la inspección del gráfico de sedimentación (Figura 1), que mostró un punto de inflexión después del tercer componente. En base a estos resultados y a la coherencia teórica del instrumento, se decidió continuar con la extracción de cuatro factores. Si bien existe la posibilidad de utilizar dos factores; siguiendo la teoría y el diseño propuesto, se proponen cuatro factores. Adicionalmente, se reportan los índices del modelo con cuatro factores: x2 = 378.173, gl = 183, CFI = .964, TLI = .958, RMSEA = .059.

Tabla 3: Análisis paralelo

Figura 1: Gráfico de sedimentación de análisis paralelo

|

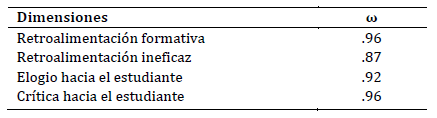

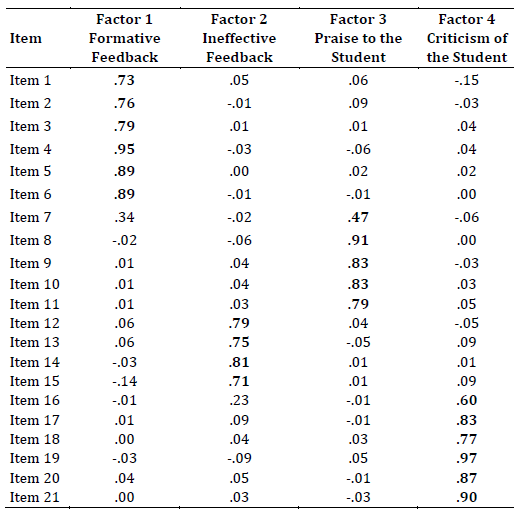

En la Tabla 4 se reportan las cargas factoriales de los resultados del AFE según las dimensiones identificadas en el análisis paralelo, utilizando la rotación Oblimin, dado que los factores se correlacionan entre sí. Los resultados indican que existen 4 dimensiones, las cuales responden a las 4 dimensiones hipotetizadas inicialmente. Asimismo, los ítems poseen cargas factoriales superiores a .40, por lo que se mantienen todos los ítems del instrumento.

Tabla 4: Cargas factoriales de los ítems

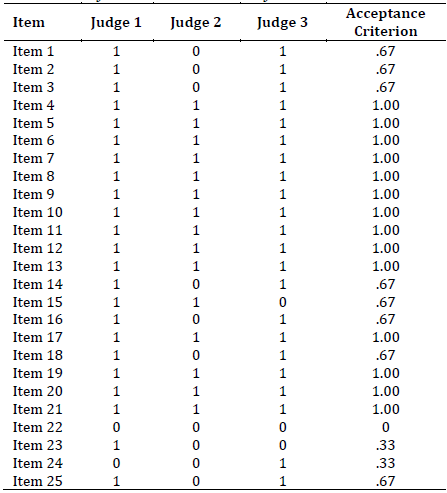

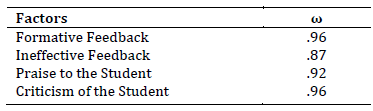

Finalmente, se analizó la consistencia interna de las dimensiones del instrumento. En la Tabla 5 se presentan los coeficientes omegas de McDonald de consistencia interna. Todos los coeficientes poseen puntajes adecuados, por lo que se puede decir que el instrumento es confiable.

Tabla 5: Índices de consistencia interna de las dimensiones del instrumento

Discusión

El objetivo de la presente investigación fue diseñar y validar un instrumento psicométrico que permita medir la percepción estudiantil sobre los tipos de retroalimentación docente en la educación superior. Los resultados obtenidos son relevantes a la teoría que se utilizó para diseñarlos.

La eliminación de cuatro ítems por parte de los jueces se debe a dos consideraciones iniciales. La primera es que la mayoría de los jueces rechazó al ítem como parte del constructo que se medía. La segunda consideración radica en una crítica por parte de uno de los jueces, que argumentaba que la redacción del ítem no permitía que éste sea considerado como parte del constructo que se medía. Esta última crítica es particularmente severa, por lo que se decidió eliminarlo.

Si se revisa el AFE realizado, se pueden identificar cuatro dimensiones en el instrumento, lo que corrobora la presencia de las dimensiones hipotetizadas en el estudio. Los ítems se agrupan de manera adecuada en las dimensiones hipotetizadas, con cargas factoriales por encima de .40. Esto permitió considerar a todos los ítems como parte de la estructura factorial final.

Es importante mencionar que, según los resultados, se podrían considerar solamente dos dimensiones. Sin embargo, no se optó por esta aproximación por dos motivos. En primer lugar, la teoría revisada planteaba una distinción de 4 dimensiones, lo que permitía un análisis más delimitado del constructo. En segundo lugar, si se analizan conceptualmente las dimensiones, se podría argumentar —desde el punto de vista del estudiante— que estas dos dimensiones podrían englobar a las cuatro finales. Eso se debe a que dos de estas dimensiones hablan acerca de la retroalimentación desde un enfoque negativo para el estudiante (retroalimentación ineficaz y crítica hacia el estudiante), mientras que las otras dos dimensiones se enfocan en aspectos positivos (retroalimentación formativa y elogio hacia el estudiante). Se podría considerar explorar esta delimitación para futuras investigaciones con el constructo y corroborar la relevancia de un instrumento de dos dimensiones.

Respecto a la confiabilidad interna, se corrobora la congruencia entre los ítems del cuestionario y las dimensiones propuestas con el coeficiente omega de McDonald, los cuales fueron superiores a .87 en todas sus dimensiones (Hair, 1998; Hair et al., 2009; Ventura-León & Caycho-Rodríguez, 2017). Ello es similar a otras escalas de retroalimentación docente que evalúan diversos aspectos o tipos de retroalimentación, como es la retroalimentación a nivel de la tarea, el proceso, la autorregulación o hacia la persona (Hattie & Timperley, 2007); retroalimentación de refuerzos y castigos, correctiva, y con alto contenido de información (Wisniewski et al. 2020); o retroalimentación de verificación, directa, de andamiaje, elogios o críticas (Guo & Wei, 2019).

La relevancia del instrumento psicométrico recae en que es una variable necesaria en investigaciones dentro del ámbito educativo, especialmente si se evalúa la dinámica de aprendizaje dentro del aula y el desempeño de estudiantes o docentes. Esto se debe a que esta variable influye en la satisfacción y autoconcepto de los estudiantes, el rendimiento académico y la motivación por buscar retroalimentación dentro del curso (Gan et al, 2021; Gentrup et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2022). Es decir, se considera una variable sumamente importante en el estudio del clima de clase y su impacto en el logro académico. Además, en los mismos estudiantes prevalece una percepción de la retroalimentación como una herramienta útil, que facilita la motivación y la autorregulación en el proceso de aprendizaje (Gan et al., 2021; Guo & Wei, 2019; Zheng et al., 2023), inclusive de forma complementaria fuera del aula (Covarrubias & Piña, 2004).

Específicamente, cuando la retroalimentación es hacia el estudiante, como el elogio, este puede mantener un sentido de autoeficacia porque una figura significativa expresa creencias positivas sobre su persona (Bandura, 1997), lo cual también influye en el rendimiento académico. De esta forma, si bien el elogio, como retroalimentación, no es un aspecto formal de un currículo, es necesario considerarlo como parte de este constructo como una práctica que fomenta el diálogo respetuoso y amable (Pendolema et al., 2023). Por este motivo, Ye et al. (2023) sugieren la exploración de los elogios y la crítica docente en el ámbito académico. Asimismo, este instrumento permite corroborar que los estudiantes perciben o disciernen cuando el docente hace una evaluación o crítica del contenido que presentan o a sí mismos. De forma complementaria, se ha identificado que, en algunos casos, sin importar la falta de especificidad en la retroalimentación, los estudiantes pueden usarlo como un recurso para mejorar sus capacidades en los temas de clase (Gentrup et al., 2020).

Respecto a las limitaciones de la presente investigación, se identifica que solo se evaluaron las dos ciudades más pobladas del Perú, Lima y Arequipa, las cuales, por características propias de las metrópolis, puede que no sean representativas de la realidad en otras ciudades del resto del país. Por ello, se exhorta al uso de este instrumento psicométrico en diferentes contextos, no solo de Perú, sino en países hispanohablantes. Es importante considerar que se mide la retroalimentación percibida de los estudiantes, y no desde el punto de vista de los docentes. Otra limitación es que no se pudo optar con más de tres jueces para la validez de contenido, lo que dificultó utilizar el criterio de Aiken. A pesar de ello, se estableció un criterio de validez estricto, requiriendo el consenso total o de al menos dos de los tres jueces para la aprobación de los ítems, lo que garantiza la relevancia del instrumento. Asimismo, si bien se utilizaron el índice de Kappa y el índice de Kendall, los niveles de aceptación de los ítems no eran los más adecuados. Esto también cuenta como una limitación.

A pesar de las limitaciones mencionadas, la escala de retroalimentación docente se considera una herramienta conveniente, válida y confiable para la medición de la percepción de retroalimentación en cualquier escenario académico con educación formal. Esta herramienta constituye un avance crucial para cerrar la brecha existente entre la intención pedagógica del profesorado y el efecto real que la retroalimentación tiene sobre el aprendizaje del estudiantado.

Asimismo, el estudio aporta una mirada contextualizada a un fenómeno que ha sido predominantemente abordado desde enfoques anglosajones o centrados en niveles escolares. Al adaptar el análisis al contexto universitario latinoamericano, se amplía la comprensión del modo en que los estudiantes interpretan la retroalimentación que reciben, incorporando dimensiones relevantes como la retroalimentación formativa, ineficaz, los elogios y las críticas.

Finalmente, los resultados de este estudio pueden ser aprovechados para fortalecer la formación docente, tanto inicial como continua, a través de procesos de autoevaluación y de reflexión informada sobre las propias prácticas de retroalimentación. Asimismo, el instrumento desarrollado puede servir como insumo en procesos de mejora institucional, al brindar evidencia sobre la calidad y el tipo de retroalimentación que experimenta el estudiantado.

Para futuras investigaciones, sería pertinente explorar la relación entre las percepciones estudiantiles sobre la retroalimentación y variables académicas relevantes, como la motivación, el desempeño o la autorregulación del aprendizaje. Una interesante línea de investigación sería la comparación entre percepciones estudiantiles y docentes, lo cual permitiría mapear posibles brechas comunicativas o divergencias en las prácticas de retroalimentación. Finalmente, se recomienda profundizar en estudios cualitativos que den cuenta de las experiencias subjetivas de los estudiantes frente a la retroalimentación recibida para aportar una comprensión más rica y contextualizada del fenómeno en diferentes contextos culturales.

Financiamiento

Proyectos de Investigación 2023 de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

Referencias

Aelterman, N., Vansteenkiste, M., Haerens, L., Soenens, B., Fontaine, J. R., & Reeve, J. (2019). Toward an integrative and fine-grained insight in motivating and demotivating teaching styles: The merits of a circumplex approach. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(3), 497-521. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000293

Altez, E. R. (2020). La Retroalimentación Formativa y la mejora de los aprendizajes en los estudiantes de la I.E. Nº 121 Virgen de Fátima-S.J.L. [Tesis de maestría]. Universidad César Vallejo. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12692/46618

Anijovich, R. (2018). Orientaciones para la Formación Docente y el Trabajo en el aula: Retroalimentación Formativa. Laboratorio de Investigación e Innovación en Educación para América Latina y el Caribe.

Ansari, T., & Usmani, A. (2018). Students perception towards feedback in clinical sciences in an outcome-based integrated curriculum. Pakistan Journal of Medicine Science, 34(3), 702-709. https://doi.org/10.12669/pjms.343.15021

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. Times Books.

Bazán-Ramírez, A., Capa-Luque, W., Bello-Vidal, C., & Quispe-Morales, R. (2022). Influence of teaching and the teacher’s feedback perceived on the didactic performance of Peruvian postgraduate students attending virtual classes during the COVID-19 pandemic. Frontiers in Education, (7), 1-16. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.818209

Benson-Goldberg, S., & Erickson, K. (2021). Praise in education. Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Education. https://doi.org/10.1093/acrefore/9780190264093.013.1645

Beriche Lezama, M. E., & Medina Zuta, P. (2021). Formative evaluation: implementation and main challenges present on schools or higher education. Educación, 27(2), 201-208. https://doi.org/10.33539/educacion.2021.v27n2.2433

Bizarro, W., Sucari, W., & Quispe-Coaquira, A. (2019). Evaluación formativa en el marco del enfoque por competencias. Revista Innova Educación, 1(3), 374-390. https://doi.org/10.35622/j.rie.2019.03.r001

Boyco, A. (2019). La retroalimentación en el proceso de aprendizaje de las matemáticas de alumnas de 5to grado de primaria de un colegio privado de Lima [Tesis de Licenciatura]. Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12404/14051

Brandmo, C., & Gamlem, S. M. (2025). Students’ perceptions and outcome of teacher feedback: a systematic review. Frontiers in Education, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2025.1572950

Brinko, K. (1993). The practice of giving feedback to improve teaching. The Journal of Higher Education, 64(5), 574-593. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.1993.11778449

Brophy, J. (1981). Teacher praise: A functional analysis. Review of Educational Research, 51(1), 5-32. https://doi.org/10.2307/1170249

Burga, V. R., Ortega, M. Y., & Hernández, B. (2023). Retroalimentación formativa en el desempeño docente. Horizontes. Revista de Investigación en Ciencias de la Educación, 7(27), 99-112. https://doi.org/10.33996/revistahorizontes.v7i27.500

Calvo, T. (2018). La retroalimentación formativa y la comprensión lectora de la Institución Educativa N° 88024, Nuevo Chimbote-2018 [Tesis de maestría]. Universidad Cesar Vallejo. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12692/36622

Carless, D., & Boud, D. (2018). The development of student feedback literacy: enabling uptake of feedback. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 43(8), 1315-1325. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1463354

Ceccarelli, J. F. (2014). Feedback en educación clínica. Revista Estomatológica Herediana, 24(2), 127-132. https://doi.org/10.20453/reh.v24i2.2134

Clark, I. (2012). Formative assessment: Assessment is for self-regulated learning. Educational Psychology Review, 24(2), 205-249.

Covarrubias, P., & Piña, M. M. (2004). La interacción maestro-alumno y su relación con el aprendizaje. Revista Latinoamericana de Estudios Educativos, 34(1), 47-84.

Criss, C. J., Konrad, M., Alber-Morgan, S. R. & Brock, M. (2024). A systematic review of goal setting and performance feedback to improve teacher practice. Journal of Behavioral Education, 33, 275-296. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10864-022-09494-1

Dawson, P., Henderson, M., Mahoney, P., Phillips, M., Ryan, T., Boud, D., & Molloy, E. (2019). What makes for effective feedback: staff and student perspectives. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 44(1), 25-36. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602938.2018.1467877

Espinoza-Freire, E. E. (2021). Importancia de la retroalimentación formativa en el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje. Revista Universidad y Sociedad, 13(4), 389-397.

Gan, Z., An, Z., & Liu, F. (2021). Teacher feedback practices, student feedback motivation, and feedback behavior: how are they associated with learning outcomes? Frontiers in psychology, 12, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.697045

Gentrup, S., Lorenz, G., Kristen, C., & Kogan, I. (2020). Self-fulfilling prophecies in the classroom: Teacher expectations, teacher feedback and student achievement. Learning and Instruction, 66, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2019.101296

Guo, W. (2017). The Relationships between Chinese Secondary Teachers' Feedback and Students' Self-Regulated Learning [Tesis de doctorado inédita]. The Chinese University of Hong Kong.

Guo, W. (2020). Grade-level differences in teacher feedback and students’ self-regulated learning. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 1-17. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00783

Guo, W., & Wei, J. (2019). Teacher feedback and students’ self-regulated learning in mathematics: A study of Chinese secondary students. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 28, 265-275. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.679575

Guo, W., Lau, K. L., & Wei, J. (2019). Teacher feedback and students’ self-regulated learning in mathematics: A comparison between a high-achieving and a low- achieving secondary schools. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 63, 48-58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2019.07.001

Hair, J. F. (1998). Multivariate Data Analysis (5a ed.). Prentice Hall.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2009). Multivariate Data Analysis (7a ed.). Prentice Hall.

Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81-112. https://doi.org/10.3102/003465430298487

Hernández, I. Y., López, R. E., & Nieto, A. D. (2024). Hacia una cultura de retroalimentación efectiva en el aula: experiencias, resultados y análisis. Revista Electrónica ANFEI Digital, 11(16), 677-686.

Hyland, F., & Hyland, K. (2001). Sugaring the pill: Praise and criticism in written feedback. Journal of Second Language Writing, 10(3), 185-212. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1060- 3743(01)00038-8

Ishaq, K., Rana, A. M. K., & Zin, N. A. M. (2020). Exploring summative assessment and effects: Primary to higher education. Bulletin of Education and Research, 42(3), 23-50.

Jenkins, L. N., Floress, M. T., & Reinke, W. (2015). Rates and types of teacher praise: A review and future directions. Psychology in the Schools, 52(5), 463-476. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.21835

Kalkbrenner, M. T. (2024). Choosing between Cronbach’s coefficient alpha, McDonald’s coefficient omega, and coefficient H: Confidence intervals and the advantages and drawbacks of interpretive guidelines. Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development, 57(2), 93-105. https://doi.org/10.1080/07481756.2023.2283637

Lipnevich, A. A., & Panadero, E. (2021). A Review of Feedback Models and Theories: Descriptions, Definitions, and Conclusions. Frontiers in Education, 6. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2021.720195

Luna, M. L., Peralta, L. E., Gaona, M. del P., & Dávila, O. M. (2022). La retroalimentación reflexiva y logros de aprendizaje en educación básica: una revisión de la literatura. Ciencia Latina Revista Científica Multidisciplinar, 6(2), 3242-3261. https://doi.org/10.37811/cl_rcm.v6i2.2086

Ma, L., Xiao, L., & Hau, K.

T. (2022). Teacher feedback, disciplinary climate, student self- concept, and

reading achievement: A multilevel moderated mediation model. Learning and

Instruction, 79, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2022.101602![]()

Ministerio de Educación. (2012). Marco del Buen Desempeño Docente. https://cdn.www.gob.pe/uploads/document/file/3425647/Marco%20del%20Buen%20Desempen%CC%83o%20Docente.pdf?v=1658161064

Ministerio de Educación. (2016). Currículo Nacional de Educación Básica. https://www.minedu.gob.pe/curriculo/pdf/curriculo-nacional-de-la-educacion-basica.pdf

Ministerio de Educación. (2025a). Evaluación del desempeño docente Nivel Primaria. https://evaluaciondocente.perueduca.pe/desempenoprimariatramo1/rubricas-de-observacion-de-aula/

Ministerio de Educación. (2025b). Monitoreo de Prácticas Escolares 2024. https://repositorio.minedu.gob.pe/handle/20.500.12799/11564

Moffat, T. K. (2011). Increasing the teacher rate of behaviour specific praise and its effect on a child with aggressive behaviour problems. Kairaranga, 12(1), 51-58. https://doi.org/10.54322/kairaranga.v12i1.152

Mollo, M. E., & Deroncele, A. (2022). Integrate formative feedback model. Revista Universidad y Sociedad, 14(1), 391-401.

Moreno, T. (2023). La retroalimentación de la evaluación formativa en educación superior. Revista Universidad y Sociedad, 15(2), 685-694.

Partin, T. C. M., Robertson, R. E., Maggin, D. M., Oliver, R. M., & Wehby, J. H. (2009). Using teacher praise and opportunities to respond to promote appropriate student behavior. Preventing School Failure: Alternative education for children and youth, 54(3), 172-178. https://doi.org/10.1080/10459880903493179

Pendolema, D. M., Barreto, X. M., Ochoa, N. G., Zambrano, B. A., & Zambrano, W. A. (2023). La retroalimentación docente en la evaluación del aprendizaje. South Florida Journal of Development, 4(9), 3457-3474. https://doi.org/10.46932/sfjdv4n9-009

Ramaprasad, A. (1983). On the definition of feedback. Behavioral Science, 28(1), 4-13. https://doi.org/10.1002/bs.3830280103

Uchpas, J. L. (2020). La retroalimentación en el aprendizaje de los estudiantes de 6 de primaria de la IE 88240–Nuevo Chimbote, 2020 [Tesis de Maestría]. Universidad César Vallejo. https://hdl.handle.net/20.500.12692/52111

Ventura-León, J. L., & Caycho-Rodríguez, T. (2017). El coeficiente Omega: un método alternativo para la estimación de la confiabilidad. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 15(1), 625-627.

Wisniewski, B., Zierer, K., & Hattie, J. (2020). The power of feedback revisited: A meta- analysis of educational feedback research. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.03087

Ye, X., Wang, Q., & Pan, Y. (2023). The impact of head teacher praise and criticism on adolescent non-cognitive skills: Evidence from China. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 1-12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1021032

Zheng, X., Luo, L., & Liu, C. (2023). Facilitating undergraduates’ online self-regulated learning: The role of teacher feedback. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 32, 805-816. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-022-00697-8

Disponibilidad de datos: El conjunto de datos que apoya los resultados de este estudio no se encuentra disponible.

Cómo citar: Navarro Fernández, R., Arizaga Castro, D. A., & Bayona Goycochea, H. (2025). Construcción y evidencias de validez y confiabilidad de una escala de retroalimentación docente percibida. Ciencias Psicológicas, 19(2), e-4199. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v19i2.4199

Contribución de los autores (Taxonomía CRediT): 1. Conceptualización; 2. Curación de datos; 3. Análisis formal; 4. Adquisición de fondos; 5. Investigación; 6. Metodología; 7. Administración de proyecto; 8. Recursos; 9. Software; 10. Supervisión; 11. Validación; 12. Visualización; 13. Redacción: borrador original; 14. Redacción: revisión y edición.

R. N. F. ha contribuido en 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10, 11, 12, 14; D. A. A. C. en 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 12, 14; H. B. G. en 1, 4, 5, 6, 11, 13, 14.

Editora científica responsable: Dra. Cecilia Cracco.

10.22235/cp.v19i2.4199

Original Articles

Construction and Evidence of Validity and Reliability of Perceived Teacher Feedback Scale

Construcción y evidencias de validez y confiabilidad de una escala de retroalimentación docente percibida

Construção e evidências de validade e confiabilidade de uma escala de percepção do feedback do professor

Ricardo Navarro Fernández1, ORCID 0000-0002-7069-9780

Diana Alexandra Arizaga Castro2, ORCID 0000-0003-1977-341X

Hugo Bayona Goycochea3, ORCID 0000-0002-2555-4670

1 Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Peru

2 Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Peru, [email protected]

3 Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Peru

Abstract:

Teacher feedback is an important tool for the learning process; however, the perception that students have about this phenomenon is not addressed in the educational context, especially in higher education. Thus, the aim of this study is to design and validate a psychometric scale that measures university students' perception of teacher feedback. The study sample consisted of 418 university students between 18 and 30 years of age. Content validity analysis was carried out by expert judges, as well as internal validity analysis using exploratory factor analysis. Internal consistency analyses are also reported. The results show excellent fit indices. Reliability coefficients were greater than .87 in all dimensions. The results obtained allow arguing the use of the instrument to measure teacher feedback perceived by students in higher education.

Keywords: feedback; psychometry; higher education; factor analysis.

Resumen:

La retroalimentación docente es una herramienta importante para el proceso de aprendizaje; sin embargo, la percepción que los estudiantes tienen sobre este fenómeno no es abordada en el contexto educativo, especialmente en el de Educación Superior. El objetivo del presente estudio es diseñar y validar una escala psicométrica que mide la percepción de estudiantes universitarios sobre la retroalimentación docente. La muestra del estudio estuvo conformada por 418 estudiantes universitarios entre 18 y 30 años. Se realizó el análisis de validez de contenido mediante jueces expertos, así como análisis de validez interna mediante el uso de análisis factorial exploratorio. También se reportan los análisis de consistencia interna. Los resultados muestran excelentes índices de ajuste. Los coeficientes de confiabilidad fueron mayores a .87 en todas las dimensiones. Los resultados obtenidos permiten argumentar el uso del instrumento para medir la retroalimentación docente percibida por los estudiantes en la educación superior.

Palabras clave: retroalimentación; psicometría; educación superior; análisis factorial.

Resumo:

O feedback docente é uma ferramenta importante para o processo de aprendizagem; no entanto, a percepção que os estudantes têm sobre esse fenômeno não é abordada no contexto educativo, especialmente no Ensino Superior. Assim, o objetivo do presente estudo é conceber e validar uma escala psicométrica que mede a percepção de estudantes universitários sobre o feedback docente. A amostra do estudo foi composta por 418 estudantes universitários com idades entre 18 e 30 anos. Realizou-se a análise de validade de conteúdo por meio de juízes especialistas, bem como a análise de validade interna por meio de análise fatorial exploratória. Também são reportadas as análises de consistência interna. Os resultados revelam excelentes índices de ajuste. Os coeficientes de confiabilidade foram superiores a 0,87 em todas as dimensões. Os resultados obtidos permitem sustentar o uso do instrumento para medir o feedback docente percebido pelos estudantes no ensino superior.

Palavras-chave: feedback; psicometria; ensino superior; análise fatorial.

Received: 02/08/2024

Accepted: 27/08/2025

Teacher feedback is a key pedagogical practice that significantly influences student learning, as it guides, reinforces, or restructures their performance through information about their tasks, processes, or attitudes (Anijovich, 2018; Clark, 2012; Hattie & Timperley, 2007). It can be delivered in different ways but is usually presented through observations that justify a grade (Wisniewski et al., 2020). In this sense, teacher’s feedback is expected to help students identify their mistakes, as well as suggest solutions, strategies, and goals related to what has been reviewed (Brinko, 1993). As a pedagogical practice, feedback functions as a scaffolding tool aimed at encouraging students to reflect on their performance and achieve their academic goals (Anijovich, 2018; Bazán-Ramírez et al., 2022; Lipnevich & Panadero, 2021).

However, not all feedback has the same impact. In some cases, it may facilitate understanding and self-regulation, while in other cases it can be rather dysfunctional, such as when it is limited to correcting mistakes without providing guidance for improvement (Guo & Wei, 2019). Different types of feedback have been proposed in the literature (Guo, 2020; Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Lipnevich & Panadero, 2021; Moreno, 2023; Wisniewski et al., 2020). These can be categorized according to its focus (product, process, or self-regulation) and its characteristics (length, quality, or affective tone) (Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Wisniewski et al., 2020). More recently, authors such as Guo (2020) have proposed a more complex framework that considers both the quality of the message given to students and complementary information related to the academic activity. Thus, Guo (2017, 2020) conceives feedback as part of a scaffolding process and highlights the importance of comments directed at student characteristics.

Based on the reviewed literature, teacher feedback can be classified into four types: Formative Feedback, Ineffective Feedback, Praise to the Student, and Criticism to the Student (Guo, 2020; Guo & Wei, 2019; Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Lipnevich & Panadero, 2021; Wisniewski et al., 2020).

Formative Feedback refers to constructive information about the content or to the guidance that teachers provide regarding the achievements and challenges in which a task can be improved. This occurs, for instance, when the teacher writes comments, gives clear instructions, or asks questions about results (Mollo & Deroncele, 2022). In this way, feedback facilitates and encourages student reflection in connection with their learning goals (Anijovich, 2018; Hernández et al., 2024; Luna et al., 2022).

By contrast, Ineffective Feedback refers to insufficient or unhelpful feedback regarding the content of a student’s work. In such cases, teacher comments are not focused on supporting student learning, as when only errors are marked, corrections are provided, and a grade is assigned without additional guidance.

Praise towards the Student refers to positive feedback directed at student performance. This type of feedback includes compliments with the purpose of enhancing students’ self-esteem and fostering improvements in their learning, as suggested by Guo (2017, 2020). Praise is a feasible and non-intrusive classroom strategy that teachers at different educational levels can easily employ (Criss et al., 2024; Jenkins et al., 2015). As such, praise may be considered a useful strategy depending on its impact on student behavior (Partin et al., 2009), since it generally makes students feel reinforced (Moffat, 2011).

Finally, Criticism to the Student refers to negative feedback regarding student performance. This includes teachers’ negative comments about students’ attitudes, behaviors, or academic performance, expressed through disapproval, rejection, or dissatisfaction (Brophy, 1981; Guo et al., 2019; Hyland, 2000, in Hyland & Hyland, 2001). Such criticism is usually directed at students who perform poorly and tends to be characterized by pressure, control, and dominance on the part of teachers (Aelterman et al., 2019). Criticism often targets perceived carelessness or low effort, or conveys that students are capable of doing better work.

In particular, formative feedback has been shown to be more effective than other forms of feedback, such as corrective feedback, indiscriminate praise, or punishment, as it provides useful information for improving future performance (Anijovich, 2018; Burga et al., 2023). By contrast, praise, punishment, rewards, and corrective feedback generally have small to moderate effects on average (Anijovich, 2018) and can negatively influence motivation, academic self-concept, and classroom experience (Ansari & Usmani, 2018; Brandmo & Gamlem, 2025; Ceccarelli, 2014).

In Peru, education policy prioritizes the assessment of learning and the achievement of educational quality, as reflected in normative documents such as the Marco de Buen Desempeño Docente (Teacher Performance Framework; Ministerio de Educación [Minedu], 2012) and the Currículo Nacional de Educación Básica (National Curriculum for Basic Education; Minedu, 2016). Within teacher performance evaluation, classroom monitoring and the quality of the feedback provided are explicitly assessed (Minedu, 2025a). However, evidence from the Monitoreo de Prácticas Escolares (School Practices Monitoring, MPE) indicates that only 1 % of basic education teachers achieve an effective level of formative assessment (Minedu, 2025b). Consequently, most teachers tend to provide superficial feedback, pointing only to the correct answer without offering information on how to improve.

Despite the regulatory emphasis, research on this phenomenon in Peru has been limited almost exclusively to undergraduate theses evaluating formative feedback in university students through self-report questionnaires correlated with performance variables (Altez, 2021; Boyco, 2019; Calvo, 2018; Uchpas, 2020) or opinion articles discussing the importance of formative assessment and feedback (Beriche & Medina, 2021; Bizarro et al., 2019; Espinoza-Freire, 2021). This indicates a knowledge gap in the study of teacher feedback in the country.

It is worth noting that teachers and students do not always share a common vision regarding feedback in the educational process. Previous studies have shown that teachers tend to overestimate the clarity, usefulness, and frequency of the feedback they provide, while students often perceive it as insufficient, unspecific, or lacking in guidance for improvement (Benson-Goldberg & Erickson, 2021; Dawson et al., 2019). This dissonance in perceptions poses an obstacle to the formative purpose of feedback, since what truly impacts learning is how students interpret, process, and use the information received (Carless & Boud, 2018).

From this perspective, evaluating feedback solely from the teacher’s viewpoint is limited, as it overlooks the experiences of those who are its primary recipients. Hence, it is necessary to place students at the center of the evaluation process, acknowledging their active role in interpreting pedagogical messages and constructing meaning from them (Carless & Boud, 2018; Mollo & Deroncele, 2022). Moreover, considering student perceptions makes it possible to identify whether feedback fulfills key functions such as clarifying expectations, guiding improvement, and fostering self-regulation (Hernández et al., 2024; Lipnevich & Panadero, 2021).

Therefore, having valid and reliable instruments to systematically capture student perceptions of the different types of teacher feedback is crucial to bridging the gap between teacher intentions and the actual impact on learning. In this context, the general objective of the present study was to design and validate a psychometric instrument to measure students’ perceptions of teacher feedback in higher education. This instrument considers four theoretical dimensions derived from the literature: formative feedback, ineffective feedback, praise to the student, and criticism to the student (Guo & Wei, 2019; Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Lipnevich & Panadero, 2021).

The main contribution of this study lies in providing a valid and context-sensitive tool for investigating feedback practices at the higher education level from the students’ perspective. Unlike previous studies that focused on teacher feedback in elementary school or Anglo-Saxon contexts, this study offers empirical and conceptual evidence from a Latin American university perspective. This fills an important gap in understanding how students interpret the feedback they receive in institutions within our region. Such a contribution is relevant to the field of educational research, as it enables critical evaluation of teaching practices from the students’ viewpoint, informs initial and ongoing teacher training processes, and supports the design of more effective and equitable pedagogical strategies in higher education.

Method

Participants

The sample was selected using non-probability sampling and consisted of 418 university students aged between 18 and 30 (M = 20.87, SD = 2.33), with 147 (35.2 %) participants identifying as male and 271 (64.8 %) identifying as female. Likewise, 223 (53.34 %) of the participants came from the city of Lima, while 195 (46.65 %) came from the city of Arequipa. On the other hand, 216 (51.67 %) students came from a private university, while 202 (48.33 %) came from a public university. The inclusion criteria were that students be of legal age (18 years or older) and be enrolled at the university during the fieldwork, as well as during the previous cycle. It was also taken into consideration that all of the courses they had been taking were face-to-face.

Instruments

Perception of Teacher’s Feedback Questionnaire (Cuestionario de Percepción de Retroalimentación Docente, CPRD). The instrument was created based on studies by Guo et al. (2019), Guo (2020), Ramaprasad (1983), and Wisniewski et al. (2020), as well as existing psycho-pedagogical evidence on summative and formative assessments (Anijovich, 2018; Hattie & Timperley, 2007; Ishaq et al., 2020). The instrument has 21 items, which are answered on a Likert scale from 1 (Strongly disagree) to 5 (Strongly agree), with the following instructions: “Below is a series of statements about your experience in the classroom. There are no right or wrong answers, so please answer honestly.” The items are grouped into four dimensions based on theoretical and empirical evidence:

- Formative feedback: refers to the participant's perception of the constructive comments provided by the teacher on the quality of a task or activity performed. For example, item 5 states: “The feedback provided by my teacher allows me to reflect on what I need to improve in my tasks.” This goes beyond grading or checking right or wrong, giving the student a sense of scaffolding in their learning. It consists of 6 items.

- Ineffective feedback: measures the student's perception of the teacher's feedback on the content assessed. For example, item 13 states: “My teacher only gives me a final score instead of correcting each question on an assessment.” In this sense, this dimension assesses whether the feedback is based on criticism that does not support the student's learning, being more critical and unrelated to the content assessed. It consists of 6 items.

- Praise to the student: this addresses the participant's perception of the teacher's comments about the quality of their skills or performance. Feedback is given in terms of how well they perform in the academic environment. For example, item 10 states, “My teacher makes positive comments to a student when they have outstanding grades.” It consists of 5 items.

- Criticism of the student: measures the student's perception of the teacher's feedback on their performance. In this sense, this dimension assesses whether the feedback is not directly related to the task being evaluated, but is more of a criticism of the student and their abilities. For example, item 19 states, “When someone gets a bad grade on a test, my teacher implies that it was to be expected for this student.” It consists of 4 items.

Procedure

The items for the instrument were designed based on relevant bibliographic references on teacher feedback, particularly the studies by Guo et al. (2019), Guo (2020), Wisniewski et al. (2020), Hattie and Timperley (2007), Ishaq et al. (2020), and Anijovich (2018). The studies by Guo et al. (2019), Guo (2020), and Wisniewski et al. (2020) allowed us to identify previous psychometric instruments and their evidence in university educational contexts, which are currently the most widely used in the field of teacher feedback. The studies by Hattie and Timperley (2007), Ishaq et al. (2020), and Anijovich (2018) allowed us to define a theoretical structure proposed for this instrument. This made it possible to establish a frame of reference for the types of feedback that teachers can provide, linking it to the concepts of summative and formative assessment. Thus, an instrument initially consisting of 25 items was designed. To this end, the help of specialists in education and psychopedagogy was enlisted, who reviewed and supported the process of drafting the items.

Next, content validity was assessed by expert judges in the field. To do this, the consistency of the items was evaluated. This required contacting three experts (with at least five years of experience in teaching and designing formative and summative assessments), who reviewed and evaluated the items and responded to a questionnaire where 1 meant they accepted the item and 0 meant they did not accept the item.

Once the evidence of content validity had been analyzed, fieldwork was carried out from November 2023 to February 2024, which was done virtually by sharing the QR code of the research protocol. The protocol consisted of the following parts: informed consent, sociodemographic data, and the teacher feedback questionnaire. Participants had to read the informed consent form and then agree to participate in order to continue filling out the protocol. Otherwise, the protocol closed automatically, thanking the participant for their support. Likewise, if the participant was under 18 years of age, it also closed automatically. Finally, the protocol was applied, and participants were informed, prior to scanning the QR code, that participation was voluntary. The information was collected in a Google Form, and the database was digitized in the statistical software Rstudio.

Data analysis

For content validation, the judgment of three experts qualified in the field of teacher feedback was sought. The Kappa and Kendall coefficients were used to analyze the agreement between the judges. In addition, the percentage of agreement between the judges was considered to decide whether items should be eliminated or accepted.

Next, the descriptive data for the items in the instrument were analyzed, reporting the mean, standard deviation, skewness, and kurtosis.

An exploratory factor analysis (EFA) was also performed to identify the factor structure of the constructed instrument. For this study, and guided by theory, the use of a parallel analysis was proposed to identify possible dimensions in which the items are grouped, using the fa.parallel function of the psych package in Rstudio. The Oblimin method was used as the rotation method for the EFA, as the dimensions are related, and the Minimum Residuals (minres) method was used as the extraction method. The fit indices used were X2/df < 3, CFI and TLI > .92, RMSEA < .07 (Hair et al., 2009). For the present study, the proposal by Hair et al. (2009) will be used for the interpretation of factor loadings, which proposes a cutoff point of .35 for samples larger than 250 participants. Although some authors suggest a higher cutoff point (e.g., 0.4-0.5), the proposal by Hair et al. (2009) is usually the most widely used and cited in psychometric analyses.

Finally, a reliability analysis (omega coefficient) was performed for each dimension of the instrument. To do this, the cut-off points proposed by Kalkbrenner (2024) were used, which suggests that values greater than .65 should be considered acceptable; however, for instruments that assess personal aspects of an individual, a coefficient greater than .90 should be expected.

Ethical considerations

The research protocol was approved by the Research Ethics Committee for Social Sciences, Humanities, and Arts of the Pontifical Catholic University of Peru (063-2023-CEI-CCSSHHyAA/PUC).

Results

First, the results of the judges' validity for each item are reported. Table 1 shows the judges' responses, where 1 means that they accept the item and 0 means that they do not accept the item. Based on the results, items that are rated positively by at least two judges are accepted.

It can be seen that most items were accepted by all three judges. In addition, the Kappa coefficient was calculated for the interpretation of the judges' results, yielding a value of -.125, which is below the coefficient expected to indicate agreement among judges. The analysis is also complemented by Kendall's W coefficient (used for ordinal responses), which obtained a value of .248, indicating a small or slight agreement.

Three items were identified whose values were very low in the judges' ratings, so it was decided to eliminate them because they were not adequate or consistent with the construct being measured. Additionally, the last item (“The feedback my teacher provides tends to focus on the fact that students are not smart enough to get better grades in their course”) had the agreement of two of the judges; However, one of the judges made an important observation about the item: “I think the item here focuses on specific beliefs, which is outside the definition of the dimension provided.” Therefore, it was also decided to eliminate it.

Table 2 presents the descriptive results of the 21 items. Multivariate normality was assessed using the Henze-Zirkler (HZ) test, which showed significant results (HZ = 3.65, p < .001), indicating that the data do not follow a multivariate normal distribution. According to the PCA results, Bartlett's sphericity test is significant (p < .001) and the KMO (0.93) is acceptable. To determine the optimal number of factors to retain, a parallel analysis was performed using 100 random simulations. A polychoric correlation matrix was used due to the ordinal nature of the items.

Table 1: Content validity based on item consistency

Table 2: Descriptive Analysis

The results indicated that the first four real eigenvalues of the factors were greater than the corresponding randomly generated eigenvalues, suggesting the retention of four factors in the EFA (Table 3).

These findings were complemented by the sedimentation plot (Figure 1), which showed an inflection point after the third component. Based on these results and the theoretical consistency of the instrument, it was decided to proceed with the extraction of four factors. Although it is possible to use two factors, following the theory and proposed design, four factors are proposed. In addition, the indices of the four-factor model are reported: X2 = 378.173, df = 183, CFI = .964, TLI = .958, RMSEA = .059.

Table 3: Parallel analysis

Figure 1: Parallel Analysis Sedimentation Chart

|

Table 4 reports the factor loadings of the EFA results according to the dimensions identified in the parallel analysis, using Oblimin rotation since the factors are correlated with each other. The results indicate that there are four dimensions, which correspond to the four dimensions initially hypothesized. Likewise, the items have factor loadings greater than .40, so all items in the instrument are retained.

Table 4: Item factor loading

Finally, the internal consistency of the instrument's dimensions was analyzed. Table 5 shows the McDonald omega coefficients of internal consistency. All coefficients have adequate scores, so it can be said that the instrument is reliable.

Table 5: Internal consistency indices of the instrument dimensions

Discussion

The objective of this research was to design and validate a psychometric instrument to measure student perceptions of teacher feedback in higher education. The results obtained are relevant to the theory used to design them.

Four items were eliminated by the judges due to two initial considerations. The first is that most of the judges rejected the item as part of the construct being measured. The second consideration stems from a criticism by one of the judges, who argued that the wording of the item did not allow it to be considered part of the construct being measured. This latter criticism is particularly severe, so it was decided to eliminate it.

The EFA reveals that four dimensions are recognized in the instrument, corroborating the presence of the dimensions hypothesized in the study. The items are adequately grouped into the hypothesized dimensions, with factor loadings above .40. This allowed all items to be considered part of the final factorial structure.

It is important to mention that, according to the results, two dimensions could be considered; however, this approach was not chosen for two reasons. The first is that the revised theory proposed a distinction of four dimensions, which allowed for a more detailed analysis of the construct.

Secondly, if the dimensions are analyzed conceptually, it could be argued—from the student's point of view—that these two dimensions could encompass all four final dimensions. This is because two of these dimensions refer to feedback from a negative perspective for the student (ineffective feedback and criticism of the student), while the other two dimensions focus on positive aspects (formative feedback and praise to the student). It might be worth exploring this delimitation for future research with the construct and corroborating the relevance of a two-dimensional instrument.

With regard to internal reliability, the consistency between the questionnaire items and the proposed dimensions was verified using McDonald's omega coefficient, which was greater than .87 in all dimensions (Hair, 1998; Hair et al., 2009; Ventura-León & Caycho-Rodríguez, 2017). This is similar to others teacher feedback scales that assess various aspects or types of feedback, such as task-level, process-level, self-regulation, or person-level feedback (Hattie & Timperley, 2007); reinforcement and punishment feedback, corrective feedback, and feedback with a high information content (Wisniewski et al., 2020); or verification feedback, direct feedback, scaffolding feedback, praise or criticism (Guo & Wei, 2019).

The relevance of this questionnaire lies in the fact that it is a necessary variable in educational research, especially when evaluating classroom learning dynamics and student or teacher performance. This is because this variable influences student satisfaction and self-concept, academic performance, and motivation to seek feedback within the course (Gan et al., 2021; Gentrup et al., 2020; Ma et al., 2022). In other words, it is considered an extremely important variable in the study of classroom climate and its impact on academic achievement. Furthermore, students themselves perceive feedback as a useful tool that facilitates motivation and self-regulation in the learning process (Gan et al., 2021; Guo & Wei, 2019; Zheng et al., 2023), including in a complementary way outside the classroom (Covarrubias & Piña, 2004).

Specifically, when feedback is directed toward the student, such as praise, the student can maintain a sense of self-efficacy because a figure of authority expresses positive beliefs about them (Bandura, 1997), which also influences academic performance. Thus, although praise, as feedback, is not a formal aspect of a curriculum, it is necessary to consider it as part of this construct as a practice that encourages respectful and kind dialogue (Pendolema et al., 2023). For this reason, Ye et al. (2023) suggest exploring teacher praise and criticism in the academic setting. Likewise, this instrument allows us to corroborate that students perceive or discern when the teacher evaluates and/or criticizes the content they present or themselves. Complementarily, it has been identified that, in some cases, regardless of the lack of specificity in the feedback, students can use it as a resource to improve their skills in class topics (Gentrup et al., 2020).

Regarding the limitations of this research, it should be noted that only the two most populous cities in Peru (Lima and Arequipa) were evaluated, which due to the characteristics of large cities, may not be representative of the reality in other cities in the country. Therefore, we encourage the use of this psychometric instrument in different contexts, not only in Peru, but also in other Spanish-speaking countries. It is important to consider that the feedback measured is that perceived by students, and not from the teachers' point of view.

Another limitation is that it was not possible to select more than three judges for content validity, which made it difficult to use Aiken's criterion. Despite this, a strict validity criterion was established, requiring total consensus or at least two of the three judges to approve the items, thus ensuring the relevance of the instrument. Although the Kappa index and Kendall's index were used, the levels of acceptance of the items were not the most appropriate. This also counts as a limitation.

Despite the limitations mentioned above, the teaching feedback scale is considered a convenient, valid, and reliable tool for measuring the perception of feedback in any academic setting involving formal education. This tool represents a crucial step forward in closing the gap between teachers' pedagogical intentions and the actual effect that feedback has on student learning.

The study provides a contextualized view of a phenomenon that has been predominantly addressed from Anglo-Saxon contexts or school-level approaches. By adapting the analysis to the Latin American university context, it broadens the understanding of how students interpret the feedback they receive, incorporating relevant dimensions such as formative feedback, ineffective feedback, praise, and criticism.

Finally, the results of this study can be used to strengthen teacher training, both initial and continuing, through processes of self-assessment and informed reflection on one's own feedback practices. Likewise, the instrument developed can serve as input for institutional improvement processes by providing evidence on the quality and type of feedback that student’s experience.

For future research, it is important to explore the relationship between student perceptions of feedback and relevant educational variables, such as motivation, academic performance, or self-regulated learning. An interesting line of research would be to compare student and teacher perceptions, which would allow for the mapping of possible communication gaps or divergences in feedback practices. Finally, it is recommended to conduct more in-depth qualitative studies that account for students' subjective experiences with the feedback they receive, thus providing a richer and more contextualized understanding of the phenomenon in different cultural contexts.

Funding

Research Projects 2023 of the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú.

References

Aelterman, N., Vansteenkiste, M., Haerens, L., Soenens, B., Fontaine, J. R., & Reeve, J. (2019). Toward an integrative and fine-grained insight in motivating and demotivating teaching styles: The merits of a circumplex approach. Journal of Educational Psychology, 111(3), 497-521. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000293