Ciencias Psicológicas, v19(1)

January-June 2025

10.22235/cp.v19i1.4128

Original Articles

The impact of character strengths in well-being and optimism: A latent profile approach

El impacto de las fortalezas de carácter en el bienestar y el optimismo: Un abordaje de perfiles latentes

O impacto das forças de caráter no bem-estar e no otimismo: uma abordagem de perfis latentes

Ana Paula Cavallaro1, ORCID 0000-0002-5482-8028

Rafael Moreton Alves da Rocha2, ORCID 0000-0003-2291-2986

Camila Grillo Santos3, ORCID 0000-0002-2123-9083

Ana Paula Porto Noronha4, ORCID 0000-0001-6821-0299

1 Universidade São Francisco, Brazil, [email protected]

2 Universidade São Francisco, Brazil

3 Universidade São Francisco, Brazil

4 Universidade São Francisco, Brazil

Abstract:

Character strengths are positive traits that are manifested in behaviors, thoughts and actions that can serve as a protective factor. Understanding the latent structure of the character strengths and its relation to other positive inner sources like optimism and subjective wellbeing have important theoretical and practical implications. We aimed to test the latent profiles of the character strengths and its interaction with optimism and subjective wellbeing. A cross-sectional study using convenience sampling was conducted with 433 Brazilian participants ranging from 18 to 79 years old. Latent profile analyses were used to test models ranging from 2 to 5 classes. Latent profile analyses favored a 4-class solution, with those having higher scores on strengths also exhibiting elevated levels of subjective well-being and optimism. It was found that the strength of spirituality generated higher levels of optimism, which did not interfere with other variables such as life satisfaction and affect. Our findings are partially in consonance with studies that were held in other countries. However, when comparing the results of our study to other studies it is important to remind that the instruments that measure character strengths used in the research were not the same.

Keywords: positive psychology; psychometrics; personality; spirituality.

Resumen:

Las fortalezas de carácter son rasgos positivos que se manifiestan en comportamientos, pensamientos y acciones que pueden funcionar como un factor protector. Comprender la estructura latente de las fortalezas de carácter y su relación con otras fuentes internas positivas como el optimismo y el bienestar subjetivo tiene importantes implicaciones teóricas y prácticas. Nuestro objetivo fue probar los perfiles latentes de las fortalezas de carácter y su interacción con el optimismo y el bienestar subjetivo. Se realizó un estudio transversal con un muestreo por conveniencia que incluyó a 433 participantes brasileños, con edades entre 18 y 79 años. Se probaron modelos de 2 a 5 clases a partir de análisis de perfiles latentes. Los análisis de perfiles latentes favorecieron una solución de 4 clases, donde aquellos con puntajes más altos en fortalezas también mostraron niveles elevados de bienestar subjetivo y optimismo. Se encontró que la fortaleza de la espiritualidad generaba niveles más altos de optimismo, que no interferían con otras variables como la satisfacción con la vida y el afecto. Los hallazgos están parcialmente en consonancia con estudios realizados en otros países. Sin embargo, al comparar los resultados de este estudio con otros, es importante recordar que los instrumentos utilizados para medir las fortalezas de carácter en las investigaciones no eran los mismos.

Palabras clave: psicología positiva; psicometría; personalidad; espiritualidad.

Resumo:

As forças de caráter são traços positivos que se manifestam em comportamentos, pensamentos e ações que podem servir como fator de proteção. Compreender a estrutura latente das forças de caráter e a sua relação com outras fontes internas positivas, como o otimismo e o bem-estar subjetivo, tem importantes implicações teóricas e práticas. Nosso objetivo foi testar os perfis latentes das forças de caráter e sua interação com o otimismo e o bem-estar subjetivo. Realizou-se um estudo transversal de amostragem por conveniência com 433 participantes brasileiros variando entre 18 e 79 anos. Foram testados a partir de análises de perfis latentes modelos de 2 até 5 classes. As análises de perfil latente favoreceram uma solução de 4 classes, com aqueles com pontuações mais altas nos pontos fortes também exibindo níveis elevados de bem-estar subjetivo e otimismo. Verificou-se que a força da espiritualidade gerou maiores níveis de otimismo, o que não interferiu em outras variáveis como satisfação com a vida e afeto. Nossos achados estão parcialmente em consonância com estudos realizados em outros países. Porém, ao comparar os resultados do nosso estudo com outros estudos é importante lembrar que os instrumentos que medem as forças características utilizados nas pesquisas não foram os mesmos.

Palavras-chave: psicologia positiva; psicometria; personalidade; espiritualidade.

Received: 20/06/2024

Accepted: 09/05/2025

Different researchers have studied character strengths based on the theoretical classification by Peterson and Seligman (2004). The development of psychological instruments and the estimation of their psychometric properties have contributed to advancements in the field of positive psychology and psychological assessment (e.g., McGrath, 2015; Noronha et al., 2015; Rocha et al., 2024; Seibel et al., 2015). Therefore, the focus of research is on the operationalization of tools for measuring this construct, as they contribute to more accurate assessments and more effective interventions (Dametto & Noronha, 2019; Noronha & Batista, 2020). However, there is still a need for further studies on this construct to gain a deeper comprehension of the impact of strengths in different contexts or populations, as well as to identify heterogeneity in subgroups (Berlin et al., 2014; Weller et al., 2020). Thus, the aim of the present study was to conduct latent profile analyses (LPA) to examine the various subject groups in terms of their strengths and their interaction with the components of affect, subjective well-being, and optimism.

Character strengths are defined as positive personality traits that contribute to the development of adaptive outcomes by enabling individuals to cope with adverse situations, adapt to circumstances (Kamushadze & Martskvishvili, 2021; Wagner et al., 2020), and promote a sense of well-being (Noronha & Reppold, 2019; Yan et al., 2020). These strengths can be nurtured and developed, and they manifest in the form of patterns of thoughts, feelings, and behaviors (Mueller & Cechinel, 2020; Niemiec, 2019; Ruch et al., 2020).

The classification of character strengths, developed by Peterson and Seligman (2004), is known as the Values in Action Inventory of Strengths (VIA-IS), which is the primary and most widely used approach in literature. In this classification, there are 24-character strengths organized into six virtues: wisdom (creativity, curiosity, judgment, love of learning, and perspective), courage (bravery, persistence, honesty, and zest), humanity (love, kindness, and social intelligence), transcendence (appreciation of beauty, gratitude, hope, humor, and spirituality), justice (teamwork, fairness, and leadership), and moderations (forgiveness, modesty, prudence, and self-control).

Advancing studies exploring character strengths in conjunction with other variables enables the development of strategies and interventions focused on positive and healthy outcomes (Niemiec, 2019; Noronha et al., 2023; Ruch et al., 2020; Yan et al., 2020). Mapping the relationships between character strengths and other psychological variables can be done either dimensionally or categorically. In the former, correlations between each of the character strengths and components of other constructs are considered. In the latter, groups of individuals with similar scores in character strengths are identified, and the averages of scores on other variables within each of these groups are mapped. This approach separates subjects in a sample into subgroups based on the similarity in their response patterns, allowing for an understanding of how different combinations of latent trait levels in character strengths impact external variables relevant to the mental health of individuals (Haridas et al., 2017).

Some researchers have sought to investigate latent profiles of character strengths (Duan & Wang, 2018; Duan et al., 2019; Haridas et al., 2017; Kiye & Boysan, 2021; Liu et al., 2016). Liu et al. (2016) conducted a study with 947 Chinese children and adolescents, using the VIA-Youth questionnaire to explore character strengths. Through LPA, they identified three distinct patterns of character strengths: a high strengths group (characterized by elevated scores across most virtues), a moderate-low strengths group (with scores slightly below average), and a low strengths group (showing significantly lower scores). The distribution of these groups did not vary by gender or grade, suggesting that these patterns may reflect broader developmental or cultural influences rather than demographic differences of the sample.

Haridas et al. (2017), using a sample of 595 Australian adults, employed a multidimensional approach to character strengths by considering two dimensions within a circumplex model. In this model, the x-axis represents strengths directed toward the self (e.g., learning, curiosity) versus strengths focused on others (e.g., forgiveness, justice). Meanwhile, the y-axis represents strengths related to emotional expression – heart strengths (e.g., gratitude) versus mind-focused strengths (e.g., learning, prudence). As a result, the authors identified four strength profiles: low, mind, heart, and high. The findings indicated that, in comparison to those with low and mind strengths, the group of individuals with heart and high strengths exhibited higher subjective well-being and life functioning, as well as lower psychological symptomatology.

In a study aiming to identify latent character strength profiles and their associations with mental health outcomes, Duan and Wang (2018) applied LPA to data from 3,536 Chinese adults using the Three-Dimensional Inventory of Character Strengths (TICS), which assesses caring, inquisitiveness, and self-control. The analysis revealed two distinct profiles: an at-strengths group, characterized by high scores across all three dimensions, and an at-risk group, characterized by uniformly low scores. Participants classified in the at-strengths group reported significantly lower levels of negative emotional symptoms and higher levels of psychological well-being compared to those in the at-risk group. These findings provide empirical support for the protective role of character strengths in mental health and highlight the potential utility of person-centered approaches, such as LPA, for identifying subpopulations that may benefit from targeted strength-based interventions.

Another study conducted with a sample of 5,776 Chinese students identified three distinct character strength profiles through LPA: the strength group, the common group, and the risk group (Duan et al., 2019). The strength group exhibited high levels of self-control, inquisitiveness, and caring, and demonstrated the highest levels of strength knowledge and strength use. This group also reported significantly lower levels of anxiety and stress, and higher levels of flourishing compared to the other groups. In contrast, the risk group showed the lowest levels of all three strengths, reported the lowest strength knowledge and strength use, and experienced the highest levels of psychological distress and the lowest flourishing. The common group exhibited moderate levels of strengths and mental health indicators, performing better than the risk group but not as well as the strength group. These findings support the theoretical proposition that character strengths function along a continuum and are meaningfully associated with both mental wellbeing and illbeing.

Lastly, in a latent class analysis with 1138 Turkish adolescents, Kiye and Boysan (2021) identified six distinct profiles based on the co-occurrence of internalizing problems (e.g., depression, anxiety, social withdrawal, and somatic complaints) and externalizing problems (e.g., hostility, aggression, and rule-breaking behavior). The group labeled as externalizing and internalizing problems exhibited the most severe psychological symptoms across all measured domains and reported the lowest levels of character strengths. In contrast, the healthy subjects class demonstrated the highest endorsements of character strengths and the lowest levels of problem behaviors, underscoring the protective role of character strengths in adolescent psychological adjustment.

As indicated, studies on latent profiles of character strengths have identified varying numbers of groupings, such as two (Duan & Wang et al., 2018), three (Duan et al., 2019; Liu et al., 2016), four (Haridas et al., 2017), and six (Kiye & Boysan, 2021). However, all these studies examine profiles considering strengths grouped into higher-level dimensions (e.g., virtues) rather than each strength as an individual dimension of the construct. This limitation hinders the understanding of which specific strengths are most directly involved in their relationships with other variables. In this categorical perspective, only one of the studies (Haridas et al., 2017) investigated the relationship between character strengths and subjective well-being, and none explored the relationship between character strengths and optimism.

Subjective well-being is one of the most extensively studied constructs in Positive Psychology (Geerling et al., 2020; Lim & Tierney, 2023). Its structure is tripartite, consisting of the cognitive dimension (life satisfaction) and the affective dimension, organized into positive and negative affect (Diener et al., 2018; Jebb et al., 2020; Kushlev et al., 2021). The cognitive aspect relates to life satisfaction, which refers to how content an individual is with their own life. The affective aspects encompass positive affect, which relates to how enthusiastic, active, and alert an individual feels, as well as negative affect, which relates to the extent to which an individual experiences aversive mood states such as anger, guilt, disgust, and fear. In contrast, optimism is defined as an individual's expectation that future events will be positive (Carver & Scheier, 2023). It is considered a construct through which individuals can maintain persistence and resilience. Those with a tendency toward optimism continue to believe that their goals will be achieved and persist in their efforts to reach them, even in the face of difficulties and obstacles (Mens et al., 2020).

The investigation of different profiles of character strengths offers a significant contribution to the field of positive psychology. Understanding the existence of latent profiles of character strengths can reveal how different combinations of traits uniquely impact subjective well-being and optimism, providing a more accurate view of how these resources interact to benefit individuals. Furthermore, understanding these nuances can contribute to the development of specific intervention strategies that enhance the strengths that contribute to increasing the latent levels of positive outcome variables from which an individual or a specific group could benefit. Given the context presented, the aim of this study is to investigate latent profiles of character strengths based on the theoretical framework of Peterson and Seligman (2004) and to examine how subjective well-being and optimism differ among these different profiles.

Method

Study design and participants

This is a cross-sectional study conducted using a non-probabilistic convenience sampling method. A total of 433 individuals participated in the study, with ages ranging from 18 to 79 years (M = 44.5; SD = 13.4). Regarding demographics of the participants 85.3 % reported being women and 14.55 % being men; 79.9 % reported being white, and 15.5 % brown; 52.4 % reported being married, 30 % single and 13.1 % divorced; 54.5 % reported to be graduate students or graduated, and 38.1 % being undergraduate students or undergraduate.

Instruments

Sociodemographic Questionnaire. Questionnaire developed for this study to collect information about the participants' gender, age, marital status, and level of education.

Character Strengths Scale - Short Version (EFC-B; Batista & Noronha, 2023). The EFC-B is a self-report scale consisting of 18 items, with each item measuring a character strength, grouped into two factors: intrapersonal strengths (hope, gratitude, spirituality, appreciation of beauty, love of learning, and zest) and intellectual and interpersonal strengths (social intelligence, judgement, creativity, honesty, teamwork, bravery, modesty, leadership, perspective, humor, prudence, fairness). Responses are provided on a Likert scale ranging from 0 (not like me at all) to 4 (very much like me). In the present study, the scale demonstrated adequate fit indices (CFI = .971; TLI = .967; RMSEA = .069 [90% CI .062‑.077]; SRMR = .069) and acceptable internal consistency for both factors (intrapersonal strengths: α = .78 and ω = .84; intellectual and interpersonal strengths: α = .83 and ω = .86).

Revised Life Orientation Test (LOT-R; Scheier et al., 1994). The LOT-R is a self-report scale consisting of 10 items designed to assess dispositional optimism. Three of the items pertain to optimism, 3 to pessimism, and 4 items serve as filters and are not included in the scoring. Responses are provided on a Likert scale ranging from 1 = strongly disagree to 5 = strongly agree. In the present study, the scale demonstrated adequate fit indices for the one-dimensional model (CFI = .994; TLI = .989; RMSEA = .072 [90% CI .043 – .102]; SRMR = .044) and good internal consistency (α = .78 and ω = .82).

Life Satisfaction Scale (LSS; Diener et al., 1985). The LSS is a self-report instrument consisting of 5 items that assess overall life satisfaction. Responses are provided on a Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree). In this study, the scale demonstrated good fit indices (CFI = 1.000; TLI = 1.000; RMSEA = .000 [90% CI .000 – 0.063]; SRMR = .020) and acceptable internal consistency (α = .57 and ω = .79).

Affect Scale (AS; Zanon et al., 2013). The AS is a self-report instrument composed of 20 items that assess the emotions experienced by individuals. Out of these items, 10 evaluate positive affect (PA), and 10 evaluate negative affect (NA). Responses are provided on a Likert scale ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree). In this study, the scale demonstrated adequate fit indices (CFI = .957; TLI = .951; RMSEA = .099 [90% CI .091 – .105]; SRMR = .086) and good internal consistency for both factors (PA: α = .86 and ω = .89; NA: α = .83 and ω = .87).

Procedures

The project was submitted to the Research Ethics Committee, and after approval data collection was conducted in a virtual environment using Google Forms platform. Participants who agreed to the informed consent form were directed to the instruments. The link was shared through the authors' contact networks (emails and WhatsApp) and on social media. The link remained available for 4 months, and participants took approximately 20 minutes to complete the survey. The participants completed the questionnaires in the following order: Sociodemographic Questionnaire, EFC-B, LOT-R, LSS, and AS.

Data analysis

LPA was conducted using Mplus 7.0 software (Muthén & Muthén, 2012) to explore the potential existence of different groups of character strengths profiles. The 18-character strengths from the EFC-B were used as indicator variables. Next, the means (in z-scores) of the factors from the EA, LOT-R, and LSS were compared for each of the identified character strengths profiles to understand how the scores of these variables behave in different latent profiles. The decision regarding the number of retained classes was based on the interpretability of the classes, the lower values of Log Likelihood (LL) and Bayesian Information Criterion (BIC), and the significance of the Bootstrapped Likelihood Ratio Test (BLRT) and Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin Likelihood Ratio Test (VLMR).

Results

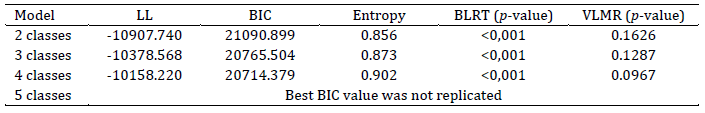

To address the study objective, LPA were performed, starting with two classes. The solution for five classes did not converge; therefore, the maximum limit that could be run with this sample was four classes. The LL and BIC indices favored the solution with four classes (Table 1), and when considering the interpretability of the other models, the three-class and four-class models were considered interpretable.

Table 1: Latent Profile Analyses Results

Note: LL: Log Likelihood; BIC: Bayesian Information Criterion; BLRT: Bootstrap Likelihood Ratio Test; VLMR: Vuong-Lo-Mendell-Rubin Likelihood Ratio Test.

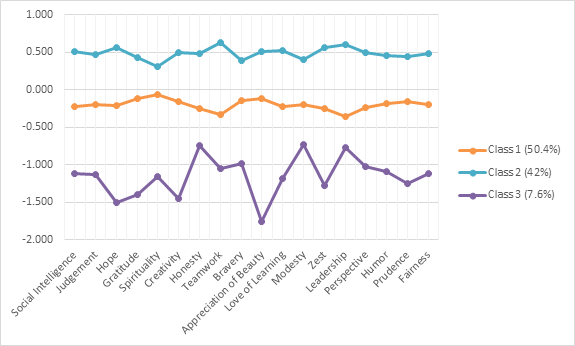

The profiles identified for the three-class solution are shown in Figure 1. Class 2 grouped individuals with higher scores on character strengths, close to half a standard deviation above the mean. Class 1 grouped individuals close to the mean but slightly below it in all character strengths. Class 3 grouped individuals with the lowest scores on character strengths.

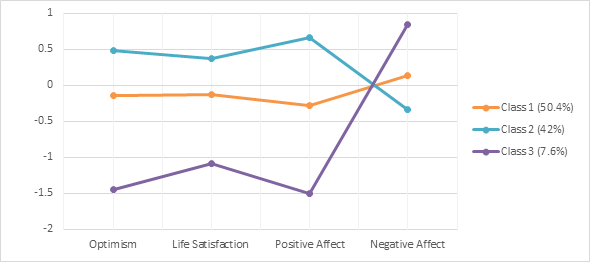

The means of AS, LOT-R, and LSS factors on the character strength profiles are depicted in Figure 2. Classes 1, 2, and 3 grouped individuals with, respectively, average, high, and low scores in optimism, life satisfaction, and positive affect. Class 3 exhibited higher scores for negative affect. It is also noticeable that there was internal variation within the classes concerning positive and negative affect, as the difference between experiences in these two constructs was smaller for Classes 1 and 2, suggesting that individuals in these classes experience both types of affects. In summary, Classes 1 and 2 experienced both positive and negative affect, with negative affect being experienced in a lower degree, while Class 3 experienced negative affect in a higher degree.

Figure 1: Latent Profiles of Character Strengths – Three-Class Model

|

Figure 2: Means of Affect, Optimism, and Life Satisfaction in Latent Character Strength Profiles – Three-Class Model

|

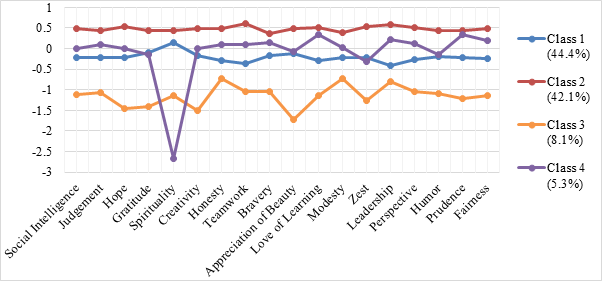

In the four-class solution (Figure 3), Classes 1, 2, and 3 resembled Classes 1, 2, and 3 from the three-class solution. In Class 3, the character strength with the most significant impairment was appreciation of beauty. However, Class 4 exhibited a particularity. Although most individuals had scores close to the mean, this class grouped individuals with the lower scores in spirituality (more than 2.5 standard deviations below the mean). The results indicate a group of individuals who do not have any spiritual or religious beliefs but have average scores in all other character strengths.

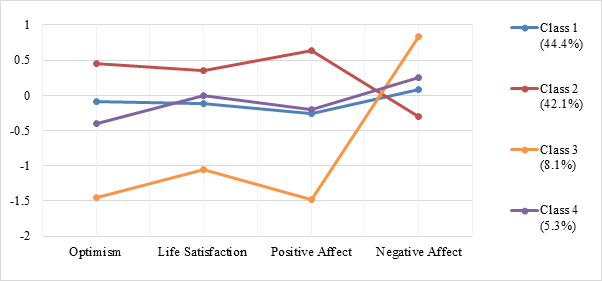

The means of AS, LOT-R, and LSS factors on the character strength profiles are depicted in Figure 4. Classes 2 and 3 had the higher and lower scores, respectively, in terms of optimism, life satisfaction, and positive affect. These results are reversed for negative affect. Classes 1 and 4 had similar means in all variables, with a noticeable difference in optimism, which could be due to the disparity in the spirituality strength between the classes, although this does not seem to substantially impact the other variables.

Figure 3: Latent Profiles of Character Strengths – Four-Class Model

|

Figure 4: Means of Affect, Optimism, and Life Satisfaction in Latent Character Strength Profiles – Four-Class Model

|

Discussion

The main objective of this study was to identify latent profiles among individuals based on their character strengths and to analyze how these profiles relate to affect, optimism, and subjective well-being. We presented results from two models, specifically the three-class model and the four-class model. This underscores the significance of comprehending how individuals group in terms of character strength scores, as endorsing character strengths is closely linked to the utilization of internal resources and positive psychological outcomes (Rashid & Niemiec, 2023).

Regarding the grouping of character strength profiles, it's worth noting that these can be considered interactive and interdependent. In other words, individuals can express combined scores rather than simply scoring a strength as high or low (Niemiec, 2013). In this context, Seligman (2015) posits that character strengths exist on a continuum ranging from mental illness (low level) to mental health (high level), suggesting that the level of character strengths is associated with adaptive behaviors. Some studies have also indicated that a high level of character strengths is significantly related to psychological well-being (Duan, 2016; Duan & Wang, 2018; Hausler et al., 2017), life satisfaction (Baumann et al., 2020), and the reduction of psychological symptoms (Azañedo et al., 2021).

Two perspectives were identified for grouping individuals based on their scores. The first perspective identified three latent classes, categorizing them as low (class 3), average (class 1), and high (class 2) in terms of character strengths. The second perspective separated them into four classes: low (class 3), average (class 1), high (class 2) and non-spiritualized average (class 4). It was observed that the low, average and high classes were similar between the two models and resulted in the same pattern of outcome variables. This is partially in consonance with the results of Liu et al. (2016) study, which identified three groups: an above-average group, consisting of individuals who scored high in all character strengths but endorsed lower interpersonal strengths like leadership; a middle group where respondents scored close to average; and a below-average group, where scores were below the expected values for each strength. However, our results indicate that, in addition to quantitative differences, such as those found between the profiles in the three-class solution, there are also qualitative differences between the different profiles in the four-class solution, since there is now another average profile but without endorsement of spirituality, reflecting individual differences and specific characteristics of this group compared to its counterpart.

Furthermore, the results reveal distinct differences in subjective well-being and optimism across the character strength profiles, with class 3 (low strengths) consistently presenting more negative outcomes, particularly higher levels of negative affect. This finding aligns with the literature, highlighting the crucial role of character strengths in emotional functioning. In both the three- and four-class solutions, the group with low endorsement of strengths showed particularly reduced scores in appreciation of beauty, a strength directly associated with greater positive affect and life satisfaction (Niemiec, 2019). The underuse of such strengths can diminish individuals' capacity to experience well-being, suggesting that lower engagement with appreciation of beauty may further intensify the affective vulnerabilities observed in this class. More broadly, character strengths are understood as internal resources that, when authentically expressed, promote resilience, effective coping with adversities, and adaptive emotional regulation (Noronha & Zanon, 2018). Therefore, the diminished endorsement and likely underutilization of these strengths may compromise the protective mechanisms typically afforded by character strengths, exacerbating negative emotional outcomes and undermining overall psychological flourishing.

An important point to discuss regarding the findings is the very low endorsement of the strength spirituality in class 4 (non-spiritualized average) and its impact on optimism. Spirituality is understood as a personal exploration of guiding questions about life, meaning, and transcendent forces, which may or may not lead to a commitment to specific religious beliefs and practices (Kor et al., 2019; Niemiec et al., 2020). It is possible to hypothesize that less spiritually inclined participants, whether religious or not, might have been less capable of looking beyond challenging moments in their lives, thus fostering a less optimistic perspective on the outcome of the situation.

In contrast, in the latent classes of three or four groups, high levels of optimism were identified in relation to the strengths of spirituality and appreciation of beauty. These findings are in line with studies on spiritual development, which is understood as a dynamic interaction involving three central psychological processes: (1) individuals being aware of their strengths, beauty, and wonder, both within themselves and in the world, in a way that cultivates meaning, identity, and goals; (2) seeking and experiencing meaning and interconnectedness in relationships with others or transcendent figures (God or a higher being); (3) individuals authentically manifesting their values, passions, and identity through tasks, practices, and bonds that provide a sense of integrity and inner peace (Kor et al., 2019).

One of the key features of character strengths is that people can reflect on them, integrate them into their plans through character strength interventions, leading to positive outcomes (Bates-Krakoff et al., 2022; Lavy, 2020; Schutte & Malouff, 2018; Yan et al., 2020). Therefore, it is possible that interventions focusing on the strength of spirituality could increase the endorsement of this strength in individuals such as those in the non-spiritualized average group. This could potentially lead to an increase in the levels of optimism in these individuals, which would have a positive impact on their lives.

Our results have relevant practical implications. The refinement of the understanding of character strength profiles has enabled us to identify both quantitatively and qualitatively different profiles. In the first case, we observe that Class 1 (medium), Class 2 (high), and Class 3 (low) differ in levels of character strengths but display a similar pattern across all strengths. In the second case, we observe Class 4, which, despite being generally like the medium profile, shows a qualitative difference in the latent level of spirituality. These findings suggest the need for interventions not only for profiles with quantitative differences (e.g., increasing strength levels to achieve positive outcomes) but also for profiles with qualitative differences. In the case of our study, we understand that this group (Class 4) did not present significant levels of spirituality. In other words, the group falls into a different category compared to its medium-level counterpart (Class 1), indicating that spirituality may be a categorical variable (some have it, others do not). Therefore, for groups that do not exhibit relevant levels of this variable, interventions aimed at increasing optimism levels should focus on elevating other predictors, since the variable most associated with it in our study (i.e., spirituality) is likely not amenable to development in that group.

The present study has several limitations. First, our sample was predominantly composed of women, which may limit the generalizability of the results. Second, the instrument used to measure character strengths was a brief version, where each item represented a specific strength; in addition, six strengths were not represented in the instrument (curiosity, persistence, love, kindness, forgiveness, and self-control) and might play a role in the mapped external variables. Therefore, using an instrument with multi-item composite indicators may provide additional information for future studies. Third, even though we compared our results with those of previous studies, these comparisons should be interpreted with caution, as the version of the instrument we used differs from those employed in other studies.

Despite the limitations, our results highlight the significant impact of character strengths on positive psychological variables and their role as protective factors against negative outcomes. This study also represents a pioneering effort in investigating latent profiles of character strengths without grouping them under virtues. While direct comparisons with existing literature are challenging due to the use of different measurement instruments and approaches to grouping (or not grouping) character strengths, the profiles identified in this study partially align with the findings of previous research (Duan & Wang, 2018; Duan et al., 2019; Haridas et al., 2017; Kiye & Boysan, 2021; Liu et al., 2016). It is important to emphasize the need for future studies, preferably of a longitudinal design, to deepen our specific understanding of the relationships between character strengths and psychological outcomes.

References

Azañedo, C. M., Artola, T., Sastre, S., & Alvarado, J. M. (2021). Character strengths predict subjective well-being, psychological well-being, and psychopathological symptoms, over and above functional social support. Frontiers in Psychology, 12. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.661278

Bates-Krakoff, J., Parente, A., McGrath, R., Rashid, T., & Niemiec, R. M. (2022). Are character strength-based positive interventions effective for eliciting positive behavioral outcomes? A meta-analytic review. International Journal of Wellbeing, 12(3), 56-80. https://doi.org/10.5502/ijw.v12i3.2111

Batista, H. H. V., & Noronha, A. P. P. (2023). Character Strengths Scale-Brief: initial psychometric studies. Estudos de Psicologia (campinas), 40, e200172. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-0275202340e200172

Baumann, D., Ruch, W., Margelisch, K., Gander, F., & Wagner, L. (2020). Character strengths and life satisfaction in later life: An analysis of different living conditions. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 15(2), 329-347. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9689-x

Berlin, K. S., Williams, N. A., & Parra, G. R. (2014). An introduction to latent variable mixture modeling (part 1): Overview and cross-sectional latent class and latent profile analyses. Journal of Pediatric Psychology, 39(2), 174-187. https://doi.org/10.1093/jpepsy/jst084

Carver, C. S., & Scheier, M. F. (2023). Optimism. In F. Maggino (Ed.), Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research (4849–4854). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-17299-1_2018

Dametto, D. M., & Noronha, A. P. P. (2019). Construção e validação da Escala de Forças de Caráter para adolescentes (EFC-A). Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto), 29. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-4327e2930

Diener, E., Emmons, R. A., Larsen, R. J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71-75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Diener, E., Oishi, S. & Tay, L. (2018). Advances in subjective well-being research. Nature Human Behavior, 2(4), 253-260. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41562-018-0307-6

Duan, W., & Wang, Y. (2018). Latent profile analysis of the three-dimensional model of character strengths to distinguish at-strengths and at-risk populations. Quality of Life Research, 27(11), 2983-2990. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11136-018-1933-1

Duan, W., Qi, B., Sheng, J., & Wang, Y. (2019). Latent character strength profile and grouping effects. Social Indicators Research, 147(1), 345-359. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-019-02105-z

Geerling, B., Kraiss, J. T., Kelders, S. M., Stevens, A. W. M. M., Kupka, R. W., & Bohlmeijer, E. T. (2020). The effect of positive psychology interventions on well-being and psychopathology in patients with severe mental illness: A systematic review and meta-analysis. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(5), 572–587. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1789695

Haridas, S., Bhullar, N., & Dunstan, D. A. (2017). What’s in character strengths? Profiling strengths of the heart and mind in a community sample. Personality and Individual Differences, 113, 32-37. https://doi:10.1016/j.paid.2017.03.006

Hausler, M., Strecker, C., Huber, A., Brenner, M., Höge, T., & Höfer, S. (2017). Distinguishing relational aspects of character strengths with subjective and psychological well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, 1159. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01159

Jebb, A. T., Morrison, M., Tay, L., & Diener, E. (2020). Subjective well-being around the world: Trends and predictors across the life span. Psychological Science, 31(3), 293-305. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797619898826

Kamushadze, T., & Martskvishvili, K. (2021). Character strength at its worst and best: Mediating effect of coping strategies. Trends in Psychology, 29(4), 655-669. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43076-021-00085-z

Kiye, S., & Boysan, M. (2021). Relationships between character strengths, internalising and externalising problems among adolescents: a latent class analysis. British Journal of Guidance & Counselling, 50(2), 303-320. https://doi.org/10.1080/03069885.2021.1872768

Kor, A., Pirutinsky, S., Mikulincer, M., Shoshani, A., & Miller, L. (2019). A longitudinal study of spirituality, character strengths, subjective well-being, and prosociality in middle school adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00377

Kushlev, K., Radosic, N., & Diener, E. (2021). Subjective well-being and prosociality around the globe: Happy people give more of their time and money to others. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 13(4), 849-861. https://doi.org/10.1177/19485506211043379

Lavy, S. (2020). A review of character strengths interventions in Twenty-First-Century schools: their importance and how they can be fostered. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 15(2), 573-596. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9700-6

Lim, W. L., & Tierney, S. (2023). The effectiveness of positive psychology interventions for promoting well-being of adults experiencing depression compared to other active psychological treatments: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 24(1), 249-273. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-022-00598-z

Liu, X., Lv, Y., Ma, Q., Guo, F., Yan, X., & Ji, L. (2016). The basic features and patterns of character strengths among children and adolescents in China. Studies of Psychology & Behavior, 27(5), 536-542.

McGrath, R. E. (2015). Character strengths in 75 nations: An update. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(1), 41-52. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.888580

Mens, M. G., Scheier, M. F., & Carver, C. S. (2020). Optimism and physical health. In K. Sweeny, M. L. Robbins & L. M. Cohen (Eds.), The Wiley Encyclopedia of Health Psychology (385-393). https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119057840.ch88

Mueller, R. R., & Cechinel, A. (2020). A privatização da educação brasileira e a BNCC do Ensino Médio: parceria para as competências socioemocionais. Educação, 45, 1-22. https://doi.org/10.5902/1984644435680

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B. O. (2012). Mplus User’s Guide (7th ed.).

Niemiec, R. M. (2013). VIA character strengths: Research and practice (the first 10 years). In H. H. Knoop & A. Delle Fave (Eds.), Well-being and cultures: Perspectives from positive psychology (pp. 11-29). Springer. https://doi/10.1007/978-94-007-4611-4_2

Niemiec, R. M. (2019). Finding the golden mean: the overuse, underuse, and optimal use of character strengths. Counselling Psychology Quarterly, 32(3–4), 453-471. https://doi.org/10.1080/09515070.2019.1617674

Niemiec, R. M., Russo-Netzer, P., & Pargament, K. I. (2020). The decoding of the human spirit: a synergy of spirituality and character strengths toward wholeness. Frontiers in Psychology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02040

Noronha, A. P. P., & Batista, H. H. V. (2020). Análise da estrutura interna da Escala de Forças de Caráter. Ciencias Psicológicas, 14(1), e2150. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v14i1.2150

Noronha, A. P. P., & Reppold, C. T. (2019). Introdução às forças de caráter. Em M. N. Baptista, M. Muniz, C. T. Reppold, Nunes, C. H. S. S., Carvalho, L. F., Primi, R., A. P. P. Noronha, A. G. Seabra, S. M. Wechsler, C. S. Hutz, & L. Pasquali (Orgs.), Compêndio de Avaliação Psicológica (pp. 549-568). Vozes.

Noronha, A. P. P., & Zanon, C. (2018). Strenghts of character of personal growth: Structure and relations with the Big Five in the Brazilian context. Paidéia (ribeirão Preto), 28, e2822. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-4327e2822

Noronha, A. P. P., Batista, H. H. V. S., & Souza, M. H. de. (2023). Percepção de religiosidade e forças pessoais: Relação entre os construtos em universitários. Interação em Psicologia, 27(1). https://doi.org/10.5380/riep.v27i1.79390

Noronha, A. P. P., Dellazzana-Zanon, L. L., & Zanon, C. (2015). Internal structure of the Characters Strengths Scale in Brazil. Psico-USF, 20(2), 229-235. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413- 82712015200204

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford University Press; American Psychological Association.

Rashid, T., & Niemiec, R. M. (2023). Character strengths. In F. Maggino (ed.), Encyclopedia of Quality of Life and Well-Being Research (723-730). Springer, Cham. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-031-17299-1_309

Rocha, R. M. A., Santos, C. G., Gonzalez, H. V., & Noronha, A. P. P. (2024). Escala de Forças de Caráter: novas evidências de validade. Ciencias Psicológicas. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v18i1.3297

Ruch, W., Niemiec, R. M., McGrath, R. E., Gander, F., & Proyer, R. T. (2020). Character strengths-based interventions: Open questions and ideas for future research. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 15(5), 680-684. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2020.1789700

Scheier, M. F., Carver, C. S., & Bridges, M. W. (1994). Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): A reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67(6), 1063-1078. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.67.6.1063

Schutte, N. S., & Malouff, J. M. (2018). The impact of signature character strengths interventions: A meta-analysis. Journal of Happiness Studies, 20(4), 1179-1196. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-018-9990-2

Seibel, B. L., DeSousa, D., & Koller, S. H. (2015). Adaptação brasileira e estrutura fatorial da escala 240-item VIA Inventory of Strengths. Psico-USF, 20, 371-383. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-82712015200301

Seligman, M. E. P. (2015). Chris Peterson’s unfinished masterwork: The real mental illnesses. Journal of Positive Psychology, 10(1), 3-6. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2014.888582

Wagner, L., Gander, F., Proyer, R. T., & Ruch, W. (2020). Character strengths and PERMA: Investigating the relationships of character strengths with a multidimensional framework of well-being. Applied Research in Quality of Life, 15(2), 307-328. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11482-018-9695-z

Weller, B. E., Bowen, N. K., & Faubert, S. J. (2020). Latent class Analysis: A guide to best practice. Journal of Black Psychology, 46(4), 287-311. https://doi.org/10.1177/0095798420930932

Yan, T., Chan, C. W. H., Chow, K. M., Zheng, W., & Sun, M. (2020). A systematic review of the effects of character strengths-based intervention on the psychological well-being of patients suffering from chronic illnesses. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 76(7), 1567-1580. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.14356

Zanon, C., Bastianello, M. R., Pacico, J. C., & Hutz, C. S. (2013). Desenvolvimento e validação de uma escala de afetos positivos e negativos. Psico-usf, 18(2), 193-201. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-82712013000200003

Data availability: The data set supporting the results of this study is not available.

Conflict of interest: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Funding: Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal de Nível Superior (CAPES).

How to cite: Cavallaro, A. P., Moreton Alves da Rocha, R., Grillo Santos, C., & Porto Noronha, A. P. (2025). The impact of character strengths in well-being and optimism: A latent profile approach. Ciencias Psicológicas, 19(1), e-4128. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v19i1.4128

Authors’ contribution (CRediT Taxonomy): 1. Conceptualization; 2. Data curation; 3. Formal Analysis; 4. Funding acquisition; 5. Investigation; 6. Methodology; 7. Project administration; 8. Resources; 9. Software; 10. Supervision; 11. Validation; 12. Visualization; 13. Writing: original draft; 14. Writing: review & editing.

A. P. O. C. has contributed in 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14; R. M. A. da R. in 2, 3, 5, 6, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14; C. G. S. in 2, 3, 5, 6, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14; A. P. P. N. in 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14.

Scientific editor in-charge: Dr. Cecilia Cracco.

Ciencias Psicológicas, v19(1)

January-June 2025

10.22235/cp.v19i1.4128

Original Articles