enero-junio 2025

10.22235/cp.v19i1.4122

Artículos Originales

Relación entre factores de personalidad y el conocimiento y la regulación metacognitiva en una muestra de estudiantes universitarios de diferentes países de habla hispana

Relation between Personality and Metacognitive Regulation in a Sample of University Students from Different Countries in Latin America

Relação entre fatores de personalidade e o conhecimento e a regulação metacognitiva em uma amostra de estudantes universitários de diferentes países de língua espanhola

Antonio P. Gutierrez de Blume1, ORCID 0000-0001-6809-1728

Diana Marcela Montoya Londoño2, ORCID 0000-0001-8007-0102

Lilián Daset3, ORCID 0000-0002-5119-324X

Ariel Cuadro4, ORCID 0000-0002-4429-9898

Mauricio Molina Delgado5, ORCID 0000-0003-4335-3095

Olivia Morán Núñez6, ORCID 0009-0007-6206-9619

Sebastián Urquijo7, ORCID 0000-0002-8315-9329

María Florencia Giuliani8, ORCID 0000-0002-5892-4527

1 Georgia Southern University, Estados Unidos, [email protected]

2 Universidad de Caldas; Universidad de Manizales, Colombia

3 Universidad Católica de Uruguay, Uruguay

4 Universidad Católica de Uruguay, Uruguay

5 Universidad de Costa Rica, Costa Rica

6 Universidad de Panamá, Panamá

7 Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, Argentina

8 Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, Argentina

Resumen:

Esta investigación examina la relación entre los factores de personalidad y la metacognición en una muestra de estudiantes de pregrado de Argentina, Colombia, Costa Rica, Panamá y Uruguay. A partir de la naturaleza interdisciplinaria de la ciencia cognitiva, el estudio enfatiza la importancia de las habilidades metacognitivas, consideradas como funciones ejecutivas fundamentales en el desempeño académico. La muestra se conformó por 692 estudiantes, de 20 a 30 años, de diversos programas de pregrado. Los participantes completaron el Inventario de conciencia metacognitiva (MAI) y el Listado de adjetivos para evaluar la personalidad (AEP). En el análisis se utilizó regresión múltiple para examinar la relación entre los cinco grandes factores de personalidad y ocho variables metacognitivas en los cinco países. Los resultados indicaron asociaciones significativas entre los factores de personalidad y los componentes metacognitivos, con la escrupulosidad y la apertura prediciendo consistentemente la regulación y el conocimiento metacognitivo. Estos hallazgos se alinean con estudios previos que sugieren que los factores de personalidad influyen en las habilidades metacognitivas. El estudio contribuye a la comprensión de cómo las diferencias individuales en la personalidad pueden afectar los procesos de aprendizaje, destacando el potencial de intervenciones dirigidas para mejorar las habilidades metacognitivas.

Palabras clave: aprendizaje; metacognición; personalidad; estudiantes universitarios; estudios transculturales.

Abstract:

This research investigates the relationship between personality factors and metacognition in a sample of undergraduate students from Argentina, Colombia, Costa Rica, Panama, and Uruguay. Recognizing the interdisciplinary nature of cognitive science, the study emphasizes the importance of metacognitive abilities—considered executive functions—on academic performance. The sample consisted of 692 students, aged 20 to 30, from various undergraduate programs. Participants completed the Metacognitive Awareness Inventory (MAI) and the Adjective Checklist for Evaluating Personality (AEP). The analysis used multiple regression to examine the relationship between the five major personality factors and eight metacognitive variables across the five countries. Results indicated significant associations between personality traits and metacognitive components, with conscientiousness and openness to new experiences consistently predicting metacognitive regulation and knowledge. These findings align with previous studies suggesting that personality traits influence metacognitive abilities. The study contributes to the understanding of how individual differences in personality can affect learning processes, highlighting the potential for targeted interventions to enhance metacognitive skills.

Keywords: learning; metacognition; personality; university students; cross cultural studies.

Resumo:

Esta pesquisa examina a relação entre os fatores de personalidade e a metacognição em uma amostra de estudantes de graduação da Argentina, Colômbia, Costa Rica, Panamá e Uruguai. Com base na natureza interdisciplinar da ciência cognitiva, o estudo enfatiza a importância das habilidades metacognitivas, consideradas como funções executivas fundamentais no desempenho acadêmico. A amostra foi composta por 692 estudantes, com idades entre 20 e 30 anos, de diversos programas de graduação. Os participantes completaram o Inventário de Consciência Metacognitiva (MAI) e a Lista de Adjetivos para avaliar a Personalidade (AEP). Na análise, utilizou-se regressão múltipla para examinar a relação entre os cinco grandes fatores de personalidade e oito variáveis metacognitivas nos cinco países. Os resultados indicaram associações significativas entre fatores de personalidade e componentes metacognitivos, com a conscienciosidade e a abertura prevendo consistentemente a regulação e o conhecimento metacognitivo. Esses achados se alinham com estudos anteriores que sugerem que os fatores de personalidade influenciam as habilidades metacognitivas. O estudo contribui para a compreensão de como as diferenças individuais de personalidade podem afetar os processos de aprendizagem, destacando o potencial de intervenções direcionadas para melhorar as habilidades metacognitivas.

Palavras-chave: aprendizagem; metacognição; personalidade; estudantes universitários; estudos transculturais.

Recibido: 14/06/2024

Aceptado: 21/04/2025

Introducción

Las ciencias cognitivas, entre las que se encuentran campos de conocimiento tan diversos como la psicología, la lingüística, las neurociencias, la inteligencia artificial, etc., contribuyen con sus desarrollos a posicionar la idea de un estudiante activo que, además de tener un buen desempeño cognitivo y académico, es capaz de aprender de forma autónoma y autorregulada, a partir de su propia capacidad de agencia.

Algunos autores consideran que la metacognición en sí misma es una función ejecutiva (Ardila & Ostrosky-Solís, 2008; Flores-Lázaro et al., 2014; Follmer & Sperling, 2016) que permite a la persona pensar sobre sus propios procesos y productos cognitivos (Flavell, 1979; 1987) o, dicho de otra manera, pensar sobre el pensamiento (Ozturk, 2020; Topping, 2024; Veenman et al., 2006), capacidad de monitoreo que se considera como una habilidad que puede formarse y enseñarse a partir de la instrucción de estrategias (Gutierrez de Blume, 2022; Nobutoshi, 2023; Silver et al., 2023; Zsigmond et al., 2025).

El monitoreo metacognitivo se entiende como la capacidad que tienen las personas para comprender con éxito lo que están aprendiendo y, por lo general, implica una serie de actividades metacognitivas como cuestionamiento, reflexión, inferencias y retroalimentación autogenerada, habilidades que le permiten a la persona reconocer cuánto domina o comprende un tema, o cuándo necesita modificar sus estrategias de aprendizaje a fin de mejorar su desempeño (Gutierrez de Blume, 2022; Zsigmond et al., 2025).

Desde diseños y propuestas muy diferentes de intervención se realizan estudios en los que se señala que la metacognición puede desarrollarse y ejercitarse a partir de un proceso de instrucción adecuada. Sin embargo, algunas de las investigaciones referidas a los efectos de los procesos de intervención sobre el monitoreo metacognitivo siguen siendo poco concluyentes en relación con el reporte sobre las diferencias en los tamaños del efecto de la precisión del monitoreo, con resultados contradictorios, inconsistentes y, esencialmente, muy diferentes entre sí (Bol et al., 2005; Bol & Hacker, 2001; Gutierrez & Schraw, 2015; Nietfeld et al., 2005; Pesout & Nietfeld, 2020; Schraw et al., 2014; Wongdaeng, 2022; Yang et al., 2023).

La alta variabilidad en los resultados de los procesos de intervención y en los tamaños del efecto reportados pueden explicarse por la diversidad de las variables del contexto y personales que entran en juego en el contexto de los procesos de intervención en el monitoreo metacognitivo. En relación con las variables del contexto, se evidencian diferencias como el clima de aula, el estilo de enseñanza, el tipo de estrategias utilizadas, las características del estudio, etc. (Abello et al., 2022; Alonso-Tapia & Ruiz-Díaz, 2022; Bryce et al., 2015; Chiarino et al., 2024; Farrington et al., 2012; Forsberg et al., 2021; Gutierrez de Blume, 2022; Morosanova et al., 2022). De la misma forma, esta diversidad se evidencia en relación con variables personales tales como: las metas de aprendizaje, el perfil cognitivo de la persona que aprende, la emociones positivas y negativas, la persistencia académica, la mentalidad de crecimiento y otros moderadores potenciales entre los que se encuentran los factores de personalidad (Abello et al., 2022; Alonso-Tapia & Ruiz-Díaz, 2022; Bryce et al., 2015; Chiarino et al., 2024; Farrington et al., 2012; Forsberg et al., 2021; Gutierrez de Blume, 2022; Morosanova et al., 2022).

En general, parece existir acuerdo respecto al hecho de que la metacognición general puede enseñarse, así como cada uno de los diferentes subcomponentes de la regulación en diferentes situaciones de aprendizaje, a la vez que se espera que esta macrohabilidad se transfiera a nuevas experiencias de aprendizaje de acuerdo con las diferentes demandas del entorno (Azevedo, 2020; Chew et al., 2018; Chew & Cerbin, 2020; Veenman et al., 2006). En este sentido, se espera que la enseñanza de las habilidades metacognitivas favorezca la formación de estudiantes para los que sea posible el aprendizaje profundo, propósito de formación que requiere que los estudiantes reflexionen sobre su propia comprensión y sobre su propio proceso de aprendizaje (Sawyer, 2019, 2022).

Sin embargo, el hecho de que como habilidad puede enseñarse no significa que necesariamente el estudiante la aprenda o que, incluso, aunque la aprenda, sea realmente consciente de la forma como está aprendiendo y esté dispuesto a usar las habilidades metacognitivas en función de un desempeño más eficiente. De hecho, en diferentes estudios se han señalado en el desempeño metacognitivo, la presencia de los sesgos de subconfianza y exceso de confianza propio de los juicios metacognitivos, así como los reportes sobre las dificultades para discriminar la sensación de saber y no saber en estudiantes que presentan dificultades con su proceso de calibración y, especialmente, en el caso de los estudiantes de bajo desempeño académico (Bol et al., 2005; Chang & Brainerd, 2023; De Bruin et al., 2017; Geraci et al., 2023; Hacker et al., 2000; Kelemen et al. 2007; Kruger & Dunning 1999; Miller & Geraci, 2011; Nietfeld et al., 2006; Zapata-Zapata et al., 2024).

En algunos estudios se ha señalado el exceso de confianza en los juicios predictivos sobre pruebas de desempeño, especialmente, para estudiantes de bajo rendimiento, fenómeno que se ha estudiado como efecto Dunning-Kruger. Por el contrario, los estudiantes de alto rendimiento presentan en su desempeño predicciones más precisas y moderan sus niveles de confianza respecto a su desempeño real efectivo (Bol et al., 2005; Chang & Brainerd, 2023; De Bruin et al., 2017; Geraci et al., 2023; Hacker et al., 2000; Kelemen et al. 2007; Kruger & Dunning 1999; Miller & Geraci, 2011; Nietfeld et al., 2006; Zapata-Zapata et al., 2024).

La asociación entre los factores de personalidad y el desempeño metacognitivo ha sido relativamente poco estudiada. Los primeros antecedentes de estudios en los que se abordó tal relación se registran en las investigaciones lideradas por Wolfe y Grosch (1990), interés que viene fortaleciéndose desde los trabajos de investigadores como Kleitman (2008) y Buratti (2013).

En estudios previos se ha indicado una relación positiva entre rasgos de personalidad como la extraversión y el exceso de confianza (Dahl et al., 2010; Pallier et al., 2002; Schaefer et al., 2004). De manera similar, hay evidencia de una asociación entre el rasgo de narcisismo y el exceso de confianza, posiblemente asociada a la forma como este tipo de personalidades suelen considerarse más inteligentes que lo que reportan las medidas de desempeño objetivas (Buratti et al., 2013; Campbell et al., 2004).

En un sentido contrario, en algunos estudios sobre la asociación entre los componentes del aprendizaje autorregulado y la personalidad se han encontrado altas correlaciones entre las medidas metacognitivas y los factores de personalidad como la escrupulosidad y la apertura a la experiencia, y, a su vez, altas correlaciones entre el desempeño académico y estos mismos factores de personalidad (Dumfart & Neubauer, 2016; Kelly & Donaldson, 2016; Morosanova et al., 2022; O’Connor & Paunonen, 2007).

Una razón que podría explicar ese tipo de resultados y diferencias probablemente trascienda el reconocimiento de lo difuso del constructo, dados sus muchos modelos teóricos y la falta de acuerdo entre los investigadores del campo en relación con sus componentes y metodologías (Dinsmore et al., 2008; Lyons & Zelazo, 2011; Tobias & Everson, 2009; Zohar & Dori, 2012) y se oriente más hacia el desarrollo de una posible explicación a partir del reconocimiento de las diferencias en la persona, como parte del estudio de las diferencias de personalidad, y su posible asociación con el desempeño metacognitivo de quien aprende (Bibi et al., 2022; De Bruin et al., 2017; Gutierrez de Blume & Montoya Londoño, 2023; Kleitman & Stankov, 2001, 2007; Pallier et al., 2002; Stankov et al., 2014).

La mayoría de los estudios que vinculan la importancia de los factores de personalidad en la formulación de juicios metacognitivos han descrito asociaciones entre el desempeño metacognitivo y los rasgos de personalidad de extraversión, narcisismo, necesidad de cognición y exceso de confianza (Campbell et al., 2004; Dahl et al., 2010; Pallier et al., 2002; Ronningstam, 2005; Schaefer et al., 2004; Wolfe & Grosch, 1990).

De igual forma, rasgos como la apertura y el nivel de confianza se han asociado con la proporción de respuestas correctas (Dahl et al., 2010; Kleitman, 2008). Mientras que en el caso del rasgo de neuroticismo versus estabilidad emocional, se ha evidenciado una correlación negativa con los sentimientos de inseguridad y confianza para diferentes tareas de juicio (Mirels et al., 2002; Want & Kleitman, 2006).

En algunos estudios se ha descrito la asociación entre factores como la apertura y la extraversión con el exceso de confianza en la formulación de juicios metacognitivos de primer y segundo orden (Buratti, 2013; Buratti et al., 2013).

Entre los estudios más recientes se encuentra una investigación realizada con 244 estudiantes de pregrado en Lenguas Extranjeras de Turquía, que tuvo como objetivo establecer la relación entre la metacognición y los rasgos de personalidad, y su interacción con el rendimiento en lenguas extranjeras. Los resultados permitieron confirmar que factores como la escrupulosidad, la apertura a la experiencia y la amabilidad explicaron el 20 % del conocimiento metacognitivo, y factores como la escrupulosidad y la apertura a la experiencia explicaron el 16 % de la regulación metacognitiva. En el estudio se confirmó que factores como la escrupulosidad y la extroversión predijeron el desempeño lector, mientras que la escrupulosidad y la apertura a la experiencia fueron predictores significativos del desempeño en el uso de la lengua (Ozturk, 2021).

Otra investigación realizada con 102 estudiantes universitarios que se encontraban cursando varios cursos de psicología en una universidad en la región sureste de los Estados Unidos tuvo como objetivo establecer la correlación entre los factores de personalidad, la comprensión lectora y la precisión de la metacomprensión antes y después de la realización de una prueba. En este estudio se encontró que factores como la apertura a la experiencia correlacionó positivamente con todas las medidas de las evaluaciones de confianza aplicadas en la tarea de comprensión lectora, pero no se correlacionó con el desempeño lector real o con la nota real efectiva, lo que indicó que los participantes evaluados presentaron el sesgo de exceso de confianza sobre su capacidad de desempeño. Asimismo, factores como la extroversión correlacionó negativamente con la autoevaluación del desempeño lector y no predijo el desempeño en lectura real efectivo (Agler et al., 2021).

De forma consistente, con la tradición investigativa de los estudios previos que se presentan en los que se establece relación entre los constructos de metacognición y personalidad, en la presente investigación se buscó establecer la relación entre factores de personalidad y metacognición en una muestra de estudiantes universitarios de diferentes países de Latinoamérica.

Pregunta de investigación

¿Cuál es el valor predictivo de los factores de personalidad sobre el conocimiento y la regulación metacognitiva en una muestra de estudiantes de pregrado de Argentina, Colombia, Costa Rica, Panamá y Uruguay?

Hipótesis

Tomando como referencia el hecho de que los trabajos que evidencian asociación entre estas dos variables han brindado resultados diversos y poco concluyentes (Bidjerano & YunDai, 2007; Blair et al., 2010; De Bruin et al., 2017; Dörrenbächer & Perels, 2016), en la presente investigación se consideró una hipótesis direccional general —no específica—, desde la que se esperaba que algunos factores correlacionaran positivamente con la metacognición, como podría ser la escrupulosidad, y otros de forma negativa, como lo sería el factor de neuroticismo.

Método

Participantes, muestreo y diseño de la investigación

El presente estudio empleó un diseño de investigación cuantitativo transversal no experimental con un enfoque de muestreo por conveniencia no aleatorio (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019). Los participantes fueron 692 estudiantes de diferentes programas de pregrado (la mayoría adscritos a programas de Psicología y Educación) de Argentina, Colombia, Costa Rica, Panamá y Uruguay, que se encontraban cursando su carrera profesional durante el año 2023. La muestra estuvo conformada por 305 hombres y 387 mujeres.

El presente proyecto corresponde a un análisis derivado del estudio inscrito en la Universidad de Manizales, Colombia, bajo la denominación: “Funcionamiento metacognitivo en el desempeño de docentes y estudiantes de diferentes países. Análisis intercultural”, con aval bioético en Colombia, mediante código interno FCSH-202006.

La selección de la muestra se realizó́ de manera intencional, de acuerdo con los criterios de un muestreo por conveniencia. Dado que los participantes estaban cursando su carrera profesional en las universidades en la que trabajan los autores. Primero, estos fueron informados de los objetivos del estudio; luego, con aquellos que se interesaron en el estudio y aceptaron participar de forma voluntaria se realizó la firma del consentimiento informado.

Todos los estudiantes que participaron en el estudio cumplieron con los siguientes criterios de inclusión: edad entre 20 a 30 años; ausencia de alteraciones psicológicas o psiquiátricas o historial de rezago escolar (pregunta que se formuló directamente a los estudiantes de forma individual como parte del registro de los datos sociodemográficos en una reunión para la firma del consentimiento informado).

Materiales e instrumentos

Inventario de conciencia metacognitiva (MAI; Schraw & Dennison, 1994). En su formato clásico, esta prueba es un inventario de 52 ítems, agrupados en 8 subcomponentes para medir el conocimiento y la regulación metacognitiva de los adultos. Las calificaciones de cada ítem son marcadas por una barra vertical de 10 cm en una banda bipolar continua de 0-100, donde 0 equivale a no es verdad para mí mientras que muy cierto para mí está representado por una puntuación de 100. Este esquema de clasificación es superior a una escala ordinal de Likert porque aumenta la fiabilidad del instrumento incrementando la variabilidad de las respuestas (Gutierrez, 2012; Schraw & Dennison, 1994; Weaver, 1990). Las puntuaciones de cada participante en las escalas individuales se obtuvieron sumando todos los ítems de esa escala y tomando el promedio. Por lo tanto, cada participante tuvo ocho resultados compuestos, uno para cada uno de los componentes del conocimiento y la regulación de la metacognición. Los estudios que han utilizado esta herramienta han reportado coeficientes de confiabilidad de consistencia interna alfa de Cronbach que oscilan entre .74 y .91 (Gutierrez de Blume & Montoya Londoño, 2021; Gutierrez de Blume et al., 2023; Gutierrez de Blume et al., 2024; Schraw & Dennison, 1994).

Listado de adjetivos para evaluar la personalidad (AEP; Ledesma et al., 2011; Sánchez & Ledesma, 2007, 2013). Es un instrumento que se estructura a partir del modelo de los cinco grandes factores (Goldberg, 1992, 1993; Goldberg et al., 2006) como un formato compuesto por un listado de 67 adjetivos descriptores de los rasgos de personalidad. El alfa de Cronbach para la prueba oscila entre .75 para el factor de apertura hasta .85 para el factor de neuroticismo (Ledesma et al., 2011; Sánchez & Ledesma, 2013).

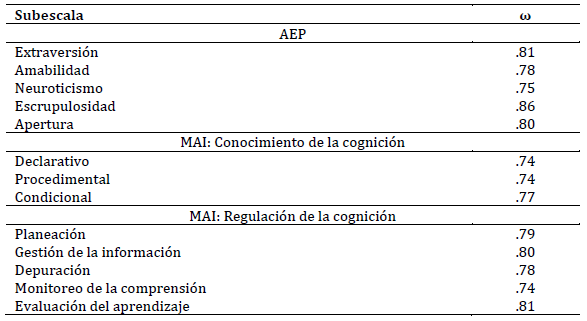

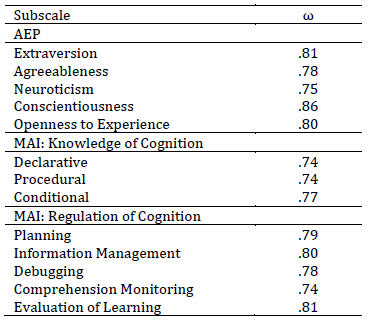

En la Tabla 1 se informan los índices de confiabilidad con la muestra de este estudio. Se utilizó el omega de McDonald en lugar del alfa de Cronbach para todas las medidas de autoinforme porque es un coeficiente de confiabilidad más conservador (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2019).

Tabla 1: Coeficientes de confiabilidad, omega de McDonald, para las ocho subescalas del MAI y los cinco factores de personalidad del AEP (N = 692)

Procedimiento

Para la recolección de información, los estudiantes de los diferentes países participantes fueron convocados en dos momentos diferentes por los investigadores responsables en cada país. Primero, se presentó a los estudiantes los objetivos y fundamentos de la investigación realizada por el equipo de trabajo; posteriormente, los estudiantes que estuvieron interesados firmaron el consentimiento informado para aceptar participar en el estudio, contando en este espacio con el acompañamiento y resolución de preguntas del investigador responsable en cada país. En un segundo momento, los estudiantes diligenciaron en una única sesión el protocolo de tareas compuesto por el MAI (Schraw & Dennison, 1994; Gutierrez de Blume et al., 2023; Gutierrez de Blume et al., 2024) y el AEP (Ledesma et al., 2011; Sánchez & Ledesma, 2013).

La aplicación del protocolo se realizó de manera grupal, por parte de cada uno de los investigadores responsables en el respectivo país, todos con experiencia en la aplicación de este tipo de tareas y con formación a nivel de doctorado. Asimismo, en el proceso de aplicación de las medidas de evaluación, se tuvieron en cuenta normas éticas de cada país y respeto por el anonimato del participante. Más específicamente, se siguieron las normas y directrices de la Declaración de Helsinki y se obtuvo el consentimiento informado de cada participante antes de completar la encuesta.

Análisis de los datos

Los datos se examinaron en busca de valores atípicos mediante el subcomando de regresión (cualquier caso con tres desviaciones estándar o más de las medias del grupo) y se probaron con los supuestos estadísticos requeridos antes del análisis. No se detectaron valores atípicos que de otro modo sesgarían las estimaciones de los parámetros y los datos cumplieron con los supuestos de linealidad, homocedasticidad, normalidad y falta de colinealidad entre los predictores. Por lo tanto, el análisis de los datos se realizó sin hacer ningún ajuste estadístico a los datos.

Para responder a las preguntas de la investigación, los datos se sometieron a una serie de regresiones (múltiples) de mínimos cuadrados ordinarios estándar en las que los cinco factores de personalidad sirvieron como predictores y las ocho variables de conciencia metacognitiva sirvieron como criterio para cada análisis, respectivamente. Este proceso se repitió para cada uno de los cinco países participantes. Como los datos de cada país eran independientes de todos los demás países, el ajuste de Bonferroni a la significancia estadística para evitar la inflación de la tasa de error tipo I familiar solo se controló para los ocho análisis realizados para cada país (el valor p real utilizado para todos los análisis fue p ≤ .01). Se empleó el coeficiente de correlación múltiple al cuadrado, R2, como tamaño del efecto para todos los análisis. Cohen (1988) proporcionó las siguientes pautas interpretativas para R2: .010-.499 como pequeño; .500-.799 como moderado; y ≥ .800 como grande.

Resultados

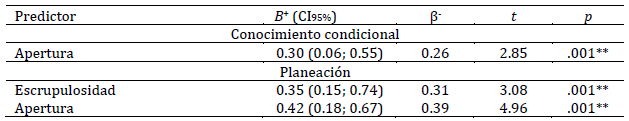

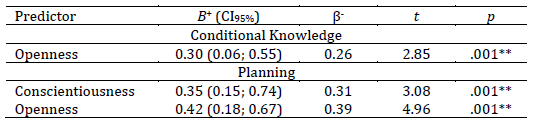

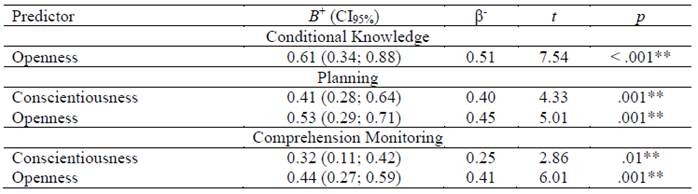

En el caso de la muestra de Argentina, el modelo de regresión ómnibus fue estadísticamente significativo: F(5.54) = 6.53, p = .012, R2 = .315. Los resultados de la regresión revelaron que el factor de personalidad de apertura a nuevas experiencias predice únicamente el conocimiento condicional, y que tanto la apertura como la escrupulosidad predicen únicamente la planeación dentro de las escalas de regulación. A medida que aumenta la percepción de los individuos sobre su apertura, también aumenta su percepción de su conocimiento condicional (es decir, cuándo, dónde y por qué se aplican las estrategias dadas las demandas de la tarea). Asimismo, cuanto más aumentan la apertura y la escrupulosidad de los participantes, se evidencia que mejoran sus habilidades de planeación (Tabla 2).

Tabla 2: Resultados de regresión de mínimos cuadrados ordinarios para variables de personalidad y metacognitivas de la muestra de Argentina

Nota: Solo los resultados estadísticamente significativos se muestran para ser parsimoniosos. N = 60. B+ = Coeficientes de regresión no estandarizados y su intervalo de confianza del 95 % (IC95%). β- = Coeficientes de regresión estandarizados. **p < .01.

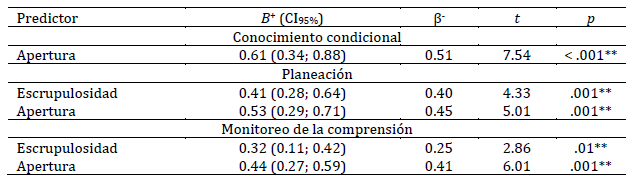

De manera similar, en la muestra colombiana, el modelo de regresión ómnibus fue estadísticamente significativo: F(5.346) = 21.93, p < .001, R2 = .516. Los resultados de la regresión revelaron que la apertura a nuevas experiencias era el único predictor positivo significativo del conocimiento condicional, y que la apertura y la escrupulosidad predicen positivamente de manera significativa la planeación y el monitoreo de la comprensión. Curiosamente, los coeficientes de regresión estandarizados fueron más altos que en la muestra de Argentina en todos los aspectos, excepto en el monitoreo (Tabla 3).

Tabla 3: Resultados de regresión de mínimos cuadrados ordinarios para variables de personalidad y metacognitivas de la muestra de Colombia

Nota: Solo los resultados estadísticamente significativos se muestran para ser parsimoniosos. N = 352. B+ = Coeficientes de regresión no estandarizados y su intervalo de confianza del 95 % (IC95%). β- = Coeficientes de regresión estandarizados. **p ≤ .01.

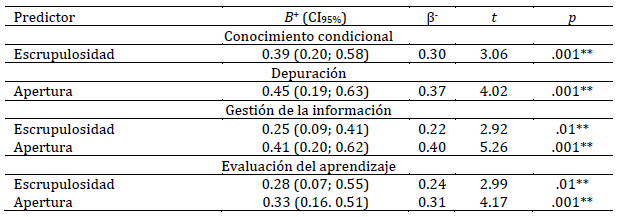

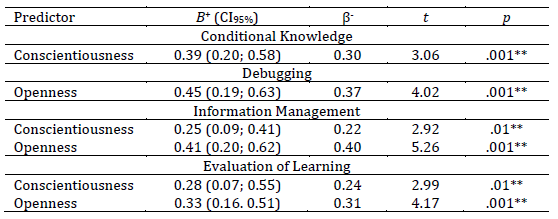

El modelo de regresión ómnibus fue estadísticamente significativo para la muestra costarricense: F(5.95) = 8.35, p < .011, R2 = .448, donde los resultados cambian. Los hallazgos indicaron que la escrupulosidad predijo positivamente el conocimiento condicional, mientras que solo la apertura, predijo positivamente las habilidades de depuración. Sin embargo, tanto la apertura como la escrupulosidad predijeron positivamente la gestión de la información y la evaluación del aprendizaje (Tabla 4).

Tabla 4: Resultados de regresión de mínimos cuadrados ordinarios para variables de personalidad y metacognitivas de la muestra de Costa Rica

Nota: Solo los resultados estadísticamente significativos se muestran para ser parsimoniosos. N = 101. B+ = Coeficientes de regresión no estandarizados y su intervalo de confianza del 95 % (IC95%). β- = Coeficientes de regresión estandarizados. **p ≤ .01.

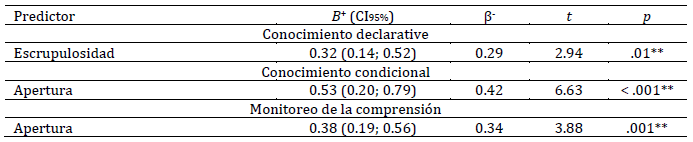

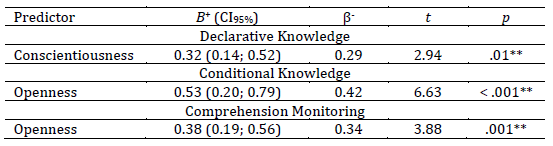

El modelo de regresión ómnibus fue estadísticamente significativo para la muestra panameña: F(5.115) = 7.11, p < .018, R2 = .296. La Tabla 5 informa que la escrupulosidad fue un predictor positivo del conocimiento declarativo y que la apertura predijo positivamente el conocimiento condicional y el monitoreo de la comprensión.

Tabla 5: Resultados de regresión de mínimos cuadrados ordinarios para variables de personalidad y metacognitivas de la muestra de Panamá

Nota: Solo los resultados estadísticamente significativos se muestran para ser parsimoniosos. N = 121. B+ = Coeficientes de regresión no estandarizados y su intervalo de confianza del 95 % (IC95%). β- = Coeficientes de regresión estandarizados. **p ≤ ,01

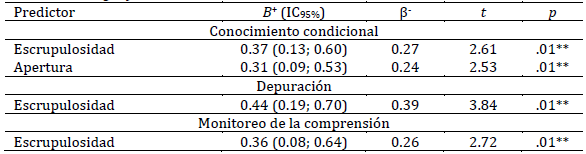

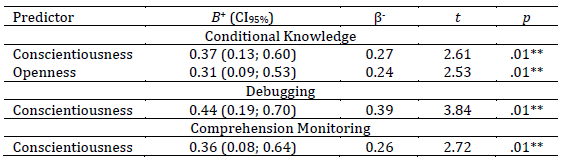

Finalmente, el modelo de regresión ómnibus fue estadísticamente significativo en la muestra de Uruguay: F(5.52) = 5.93, p < .023, R2 = .255. Para esta muestra, los resultados demostraron que la escrupulosidad y la apertura predijeron positivamente el conocimiento condicional, mientras que solo la escrupulosidad predijo positivamente la depuración y el monitoreo (Tabla 6).

Tabla 6: Resultados de regresión de mínimos cuadrados ordinarios para variables de personalidad y metacognitivas de la muestra de Uruguay

Nota: Solo los resultados estadísticamente significativos se muestran para ser parsimoniosos. El análisis de potencia post-hoc del modelo de regresión para este país mostró una potencia observada de 0.841, superior al valor límite inferior comúnmente aceptado de 0.80. N = 58. B+ = Coeficientes de regresión no estandarizados y su intervalo de confianza del 95% (IC95%). β- = Coeficientes de regresión estandarizados. **p ≤ .01.

De estas cinco muestras latinoamericanas se desprende claramente que, a pesar de los matices tanto del lenguaje como de la cultura, la apertura a nuevas experiencias y la escrupulosidad fueron consistentemente los únicos factores de personalidad que predijeron positivamente el conocimiento condicional dentro del conocimiento de la cognición y de los cinco componentes de la regulación de la cognición, aunque este último patrón difería según la cultura.

Discusión

El estudio de la metacognición y su importancia para el estudiante en el logro de un aprendizaje eficiente ha acompañado las investigaciones en el campo de las ciencias del aprendizaje desde los estudios seminales de Flavell (1979, 1987). Sin embargo, en el contexto actual, la metacognición deja de ser un problema casi exclusivo acerca de la forma en la que la persona aprende, conoce y regula sus propios recursos cognitivos, hacia el abordaje de la metacognición como un constructo mucho más social, que involucra otras variables de la persona que aprende, tales como la personalidad, las preferencias en el aprendizaje, los niveles de motivación, el género, las funciones ejecutivas, el autoconcepto y los estilos parentales, etc. (Gutierrez de Blume & Montoya Londoño, 2022, 2023; Gutierrez de Blume et al., 2022; Händel et al., 2020).

En el presente trabajo de investigación el objetivo fue establecer la relación entre factores de personalidad y metacognición en una muestra intercultural de estudiantes de pregrado de diferentes países de Latinoamérica. Se confirmó para el caso de las muestras aportadas desde todos los países participantes la relación existente entre algunos factores de personalidad con los grandes componentes de la metacognición. Esta relación de forma general ya había sido previamente reportada en estudios que han señalado correlaciones moderadas entre la estimación del nivel de confianza y diferentes factores de personalidad, tales como los rasgos de apertura y extraversión (Buratti & Allwood, 2012; Gutierrez de Blume & Montoya Londoño, 2020, 2023; Kleitman & Stankov, 2007; Nietfeld & Schraw, 2002; Šafranj et al., 2021; Stankov, 2000, 2018; Stankov & Crawford, 1996, 1997). Asimismo, se han reportado correlaciones significativas entre estos mismos factores de personalidad, apertura a la experiencia y extraversión, con el conocimiento y la regulación metacognitiva (Öz, 2016), así como diferentes correlaciones entre factores de personalidad y juicios metacognitivos (Händel et al., 2020).

Desde la tradición investigativa propia del campo, se considera la metacognición como el predictor más efectivo de los resultados de aprendizaje (Özçakmak et al., 2021; Swanson et al., 2024; Thiede et al., 2019; Veenman, 2015; Wang et al., 1990). Al respecto, diferentes investigadores han señalado que los estudiantes con un adecuado desempeño metacognitivo frente a los desafíos de aula pueden diferenciar lo que saben de lo que no saben y seleccionar estrategias adecuadas para dominar los aprendizajes que aún no comprenden, desarrollan una conducta de estudio basada en objetivos, establecen planes de estudio, evalúan los resultados y pueden ajustar los planes en función del proceso de evaluación que realizan sobre su proceso. Así puede considerarse que la metacognición le permite a los estudiantes ser más eficientes en su aprendizaje (Bürgler et al., 2022; Celik, 2022; Stanton et al., 2021).

Al respecto, se ha señalado que, dada la relevancia de la metacognición para el desempeño escolar eficiente, los investigadores hacen esfuerzos por aclarar los criterios que deberían considerarse en cualquier proceso de intervención de la metacognición, entre los que se encuentran: 1) incluir la instrucción metacognitiva como parte del contenido de clase, 2) informar a los estudiantes sobre la utilidad y aplicación de las estrategias metacognitivas, 3) prolongar el entrenamiento en el tiempo para garantizar la aplicación fluida y sostenida del desempeño metacognitivo. Sin embargo, estos procesos de intervención e instrucción siguen siendo un tanto inexplorados y aportan, a la vez, resultados poco concluyentes (Azevedo, 2020).

Estudios como el presente representan un aporte en el logro de una mayor explicación de los resultados inconsistentes, derivados de diferentes propuestas de intervención, que parecen explicar el problema del desempeño metacognitivo en el estudiante, mediado por factores de personalidad, que pueden potenciar o limitar las posibilidades para que el estudiante pueda hacer un aprovechamiento más óptimo de los procesos de intervención y de las oportunidades del mismo proceso de reflexión metacognitiva.

En esta perspectiva, en diferentes estudios se ha reconocido, por ejemplo, que la precisión de la calibración puede estar influenciada por un autoconcepto más global de capacidad, asociado a características relativamente estables de personalidad, en lugar de a datos de rendimiento real, lo que puede ser una razón por la cual la calibración parece ser un proceso en ocasiones tan resistente al cambio (Bol et al., 2005; Bol & Hacker, 2001; Dembo & Seli, 2004; Hacker & Bol, 2004; Hacker et al., 2000; Zimmerman & Moylan, 2009).

Asimismo, estudios que se han realizado por fuera del aula, en los que se aborda la relación entre los factores de personalidad (cinco grandes) y la evaluación de los componentes de la metacognición en la vida cotidiana (las creencias metacognitivas, la confianza en la memoria, el juicio de aprendizaje y los juicios de sentimiento de conocimiento) durante tareas de reconocimiento de nombres de caras, se encontró que, las personas evaluadas con rasgos de neuroticismo evidenciaron juicios de aprendizaje y precisión más bajos que las personas que evidenciaron rasgos de extraversión. Se logró establecer que las personas con rasgos de neuroticismo tenían poca confianza en su memoria, y reportaron creencias metacognitivas más negativas que las personas con tendencia a la extraversión (Irak, 2024).

En el presente estudio, a nivel del conocimiento metacognitivo, se encontró relación entre los tipos de conocimiento declarativo y condicional con el factor de apertura a la experiencia para todas las muestras de los países evaluados. Este resultado es interesante, dado que el conocimiento en general se considera la base de regulación metacognitiva de la persona; el conocimiento declarativo le permite al estudiante conocerse a sí mismo como aprendiz, conocer el estado de su conocimiento y el tipo de estrategias con las que cuenta, etc.; mientras que el conocimiento condicional le permite saber cuándo, dónde, por qué y para qué usarlo (Brown, 1987; Gutierrez de Blume et al., 2024; Gunstone & Mitchell, 1998; Jacobs & Paris, 1987; Montoya et al., 2024; Moshman, 2017; Schraw & Moshman, 1995; Soleimani et al., 2018). En este marco, resulta lógico que un factor de personalidad, como la apertura a la experiencia, que implica disposición hacia una imaginación activa, habilidad para reflexionar sobre uno mismo y curiosidad intelectual (Costa & McCrae, 1985, 1992), conduzca a un mayor conocimiento metacognitivo, que implica el conocimiento que la persona posee acerca de la propia cognición o acerca de la cognición en general y, especialmente, acerca de la forma como aprende.

En el mismo sentido, habilidades de regulación metacognitiva, como la planeación y el monitoreo, se relacionaron con el factor de apertura y con el factor de escrupulosidad para el caso de las muestras de estudiantes evaluadas de Argentina, Colombia, Panamá y Uruguay. Al respecto, se considera que la regulación implica el conjunto de habilidades que le permiten a la persona tener un proceso de anticipación, control y juicio sobre el estado del aprendizaje desde algunos subcomponentes básicos entre los que se encuentran la planeación, la gestión de la información, el monitoreo, la depuración y la evaluación (Brown, 1987; Gutierrez de Blume et al., 2024; Jacobs & Paris, 1987; Jiménez & Puente, 2014; Montoya et al., 2024; Moshman, 2017; Schraw & Moshman, 1995; Schraw & Dennison, 1994). Mientras que el factor de personalidad de la escrupulosidad o responsabilidad se ha entendido como la capacidad para tener una conducta autorregulada, para actuar con base en los objetivos y establecer un sistema de metas, que le permite planificar, organizar y llevar a cabo sus proyectos (Genise et al., 2020; Lingjaerde et al., 2001), de ahí que pueda estar muy relacionado con habilidades de regulación implicadas en la planeación y supervisión del proceso de estudio e, incluso, en el ajuste de las metas o el plan de acción en caso de que se requiera.

Se evidenció relación entre otras habilidades de regulación metacognitiva, entre las que se encontraron la depuración, la gestión de la información y la evaluación con los factores de personalidad de apertura y escrupulosidad para el caso de la muestra evaluada de Costa Rica. Esto podría explicarse, probablemente, por el tipo de políticas y lineamientos curriculares dados desde el Ministerio de Educación Pública (MEP, 2023) de dicho país, desde los cuales se impulsa el trabajo docente de la metacognición y en sus últimos lineamientos para las actividades en el aula se señala que mediante la evaluación del aprendizaje en el país se busca que el estudiante autorregule su proceso de aprendizaje de acuerdo con sus características e intereses, de manera tal que se vivencien procesos de autorreflexión y retroalimentación en torno a la construcción de sus conocimientos (MEP, 2023). Lo que parece evidenciarse desde la forma como estos dos factores de personalidad conducen a un mejor desempeño de las habilidades de regulación.

Finalmente, puede señalarse que los factores de personalidad de apertura a la experiencia y escrupulosidad llevan a un mejor desempeño metacognitivo, en especial, en relación con los componentes de conocimiento declarativo y condicional, y las habilidades de regulación, sobre todo a nivel de la planeación y el monitoreo.

Estos resultados son consistentes con investigaciones previas, entre las que se encuentra una investigación realizada con estudiantes de pregrado de la Universidad Estatal de Turquía, en la que se encontró que los factores de apertura a la experiencia y responsabilidad tienen una relación positiva y significativa con la metacognición (Sapancı & Güler, 2021). Asimismo, este resultado es consistente con los hallazgos de un estudio realizado con estudiantes universitarios de una Universidad en Escocia, en el que se encontró que, en los estudiantes evaluados que evidenciaron un alto nivel de escrupulosidad, se estableció que la metacognición fue un predictor adecuado de sus calificaciones académicas (Kelly & Donaldson, 2016).

Estos hallazgos resultan muy pertinentes en cuanto se considera que aspectos como la responsabilidad y la apertura mental podrían influir en la capacidad del estudiante para planear, organizar, evaluar y ajustar su conducta de estudio y para persistir en la búsqueda de un desempeño eficiente. Al respecto, investigadores como Barrick y Mount (1991) y Britwum et al., (2022) han señalado que los estudiantes con alta apertura a la experiencia son aquellos que tienen una actitud positiva hacia experiencias de aprendizaje profundas, complejas y desafiantes, y que suelen tener un mayor éxito en el desempeño académico.

Conclusiones

En el estudio se confirma la relación positiva entre factores de personalidad como la escrupulosidad y la apertura a la experiencia con diferentes tipos de conocimiento metacognitivo, declarativo y condicional, y con diferentes habilidades de regulación metacognitiva, especialmente, a nivel de la planeación y el monitoreo para el caso de la mayoría de los países incluidos en la presente investigación. Por el contrario, no se confirmó la relación negativa entre neuroticismo y desempeño metacognitivo, que también ha sido descrita en la literatura especializada.

Resulta de interés la relación que se encontró entre habilidades metacognitivas de regulación, como la depuración, la gestión de la información y la evaluación, con los factores de personalidad de apertura y escrupulosidad para el caso de la muestra evaluada de Costa Rica. Este resultado probablemente pueda ser el explicado por la promoción de diferentes políticas educativas para el trabajo con propuestas de innovación centradas en la metacognición, que se han implementado en dicho territorio durante los últimos años.

Implicaciones para la teoría, la investigación y la práctica

La investigación sobre las relaciones entre variables cálidas, como la personalidad, y variables frías, como la metacognición, parece contribuir a explicar algunos resultados inconsistentes en muchos programas de intervención metacognitiva. Esta puede ser una línea futura de trabajo para ampliar la explicación actual que se tiene sobre los problemas de calibración y sobre las dificultades en la precisión en el monitoreo, dado que, como se evidencia en el presente estudio, algunos rasgos de personalidad, como la apertura y la responsabilidad, parecen impactar de forma positiva en el desempeño metacognitivo, en especial a nivel del conocimiento declarativo, el conocimiento condicional, la planificación y el monitoreo.

Limitaciones y nuevas avenidas de investigación

Los hallazgos del presente estudio no dejan de ser exploratorios y, aunque el tamaño de la muestra es relativamente grande en comparación con otras investigaciones de la misma naturaleza, la investigación futura debería replicar este estudio con tamaños de muestra más grandes para garantizar que el patrón correlacional y predictivo encontrado sea estable y consistente en múltiples muestras. Los resultados evidencian la necesidad de realizar estudios multiculturales para investigar hasta qué punto los resultados del presente estudio se generalizan en otras culturas, y no solo a nivel de países de Iberoamérica.

Futuras investigaciones podrían continuar explorando las posibles relaciones entre factores de personalidad y otras variables metacognitivas de interés, que podrían incluir la relación entre factores de personalidad y tipos de juicios metacognitivos, en especial, a nivel de los juicios predictivos y postdictivos para establecer posibles diferencias con los tipos de tareas (cognitiva, académica, de la vida cotidiana, etc.), forma de evaluación (en línea, fuera de línea), forma de aplicación (papel y lápiz, virtual) e, incluso, centrar el análisis en las diferencias interculturales, sobre la relación entre la personalidad, la metacognición y el efecto de las variables sociodemográficas, como el género, los años de escolarización, o algunas diferencias en el tipo de políticas educativas que varían de acuerdo con cada país.

Referencias

Abello, D. M., Alonso-Tapia, J., & Panadero, E. (2022). El aula universitaria. La influencia del clima motivacional y el estilo de enseñanza sobre la autorregulación y el desempeño de los estudiantes. Revista Complutense de Educación, 33(3), 399. https://doi.org/10.5209/rced.74455

Agler, L. M. L., Noguchi, K., & Alfsen, L. K. (2021). Personality traits as predictors of reading comprehension and metacomprehension accuracy. Current Psychology, 40(10), 5054-5063.https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-019-00439-y

Alonso-Tapia, J., & Ruiz-Díaz, M. (2022). Student, teacher, and school factors predicting differences in classroom climate: A multilevel analysis. Learning and Individual Differences, 94, 102115. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2022.102115

Ardila, A., & Ostrosky-Solís, F. (2008). Desarrollo histórico de las funciones ejecutivas. Revista de Neuropsicología, Neuropsiquiatría y Neurociencias, 8(1), 1-21.

Azevedo, R. (2020). Reflections on the field of metacognition: issues, challenges, and opportunities. Metacognition and Learning, 15(2), 91-98. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-020-09231-x

Barrick, M. R., & Mount, M. K. (1991). The Big Five personality dimensions and job performance: A meta-analysis. Personnel Psychology, 44(1), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1744-6570.1991.tb00688.x

Bibi, R., Ehsan, N., & Mushtaq, R. (2022). Meta-cognitive learning strategy, personality traits and grit among second language learners. Human Nature Journal of Social Sciences, 3(4), 353-364. https://doi.org/10.71016/hnjss/qe6wqv79

Bidjerano, T., & YunDai, D. (2007). The relationship between the big-five model of personality and self-regulated learning strategies. Learning and Individual Differences (17), 69-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2007.02.001

Blair, C., Calkins, S., & Kopp, L. (2010). Self-regulation as the interface of emotional and cognitive development: Implications for education and academic achievement. En R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Handbook of personality and self-regulation (pp. 64–90). Blackwell Publishing Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781444318111.ch4

Bol, L., & Hacker, D. (2001). A comparison of the effects of practice tests and traditional review on performance and calibration. Journal of Experimental Education, 69(2), 133-151. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220970109600653

Bol, L., Hacker, D., O’Shea, P., & Allen, D. (2005). The influence of overt practice, achievement level, and explanatory style on calibration accuracy and performance. The Journal of Experimental Education, 73(4), 269-290. https://doi.org/10.3200/JEXE.73.4.269-290

Britwum, F., Amoah, S. O., Acheampong, H. Y., Sefah, E. A., Djan, E. T., Jill, B. S., & Aidoo, S. (2022). Do extraversion, agreeableness, openness to experience, conscientiousness and neuroticism relate to students academic achievement: the approach of structural equation model and process macro. International Journal of Scientific Management Research, 05(2), 64-79. https://doi.org/10.37502/IJSMR.2022.5205

Brown, A. (1987). Metacognition, executive control, self-regulation, and other more mysterious mechanisms. En F. Weinert & R. Kluwe (Eds.), Metacognition, motivación and understanding (pp. 65-116). Lawrence Erlbaum.

Bryce, D., Whitebread, D., & Szűcs, D. (2015). The relationships among executive functions, metacognitive skills and educational achievement in 5 and 7 year-old children. Metacognition and Learning, 10(2), 181-198. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-014-9120-4

Buratti, S. (2013). Meta-metacognition: The regulation of confidence realism in episodic and semantic memory. Ineko AB. https://gupea.ub.gu.se/bitstream/handle/2077/32860/gupea_2077_32860_1.pdf?sequence=1

Buratti, S., & Allwood, C. (2012). The accuracy of meta-metacognitive judgments: Regulating the realism of confidence. Cognitive Processing, 13(3), 243-253. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10339-012-0440-5

Buratti, S., Allwood, C. M., & Kleitman, S. (2013). First- and second-order metacognitive judgments of semantic memory reports: The influence of personality traits and cognitive styles. Metacognition and Learning, 8(1), 79-102. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-013-9096-5

Bürgler, S., Kleinke, K., & Hennecke, M. (2022). The metacognition in self-control scale (MISCS). Personality and Individual Differences, 199, 111841. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.111841

Campbell, W. K., Goodie, A. S., & Foster, J. D. (2004). Narcissism, confidence, and risk attitude. Journal of Behavioral Decision Making, 17(4), 297-311. https://doi.org/10.1002/bdm.475

Celik, B. (2022). The effect of metacognitive strategies on self-efficacy, motivation and academic achievement of university students. Canadian Journal of Educational and Social Studies, 2(4), 37-55. https://doi.org/10.53103/cjess.v2i4.49

Chang, M., & Brainerd, C. J. (2023). Changed-goal or cue-strengthening? Examining the reactivity of judgments of learning with the dual-retrieval model. Metacognition and Learning, 18(1), 183-217. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-022-09321-y

Chew, S. L., & Cerbin, W. J. (2020). The cognitive challenges of effective teaching. The Journal of Economic Education, 52(1), 17-40. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220485.2020.1845266

Chew, S. L., Halonen, J. S., McCarthy, M. A., Gurung, R. A. R., Beers, M. J., McEntarffer, R., & Landrum, R. E. (2018). Practice what we teach: Improving teaching and learning in psychology. Teaching of Psychology, 45(3), 239-245. https://doi.org/10.1177/0098628318779264

Chiarino, N., Curione, K., & Huertas, J. A. (2024). Classroom motivational climate in Ibero- American secondary and higher education: a systematic review. Ciencias Psicológicas, 18(2), e-3770. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v18i 2.3770

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical power analysis for the behavioral sciences (2a ed.). Lawrence Earlbaum & Associates. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203771587

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1985). NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI). Psychological Assessment Resources. https://doi.org/10.1037/t07564-000

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1992). Normal personality assessment in clinical practice: The NEO Personality Inventory. Psychological Assessment, 4(1), 5-13. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.4.1.5

Dahl, M., Allwood, C. M., Rennemark, M., & Hagberg, B. (2010). The relation between personality and the realism in confidence judgements in older adults. European Journal of Ageing, 7(4), 283-291. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10433-010-0164-2

De Bruin, A., Kok, E., Lobbestael, J., & De Grip, A. (2017). The impact of an online tool for monitoring and regulating learning at university: overconfidence, learning strategy, and personality. Metacognition Learning, 12(1), 21-43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-016-9159-5

Dembo, M. H., & Seli, H. (2004). Students' Resistance to Change in Learning Strategies Courses. Journal of Developmental Education, 27(3), 2-11.

Dinsmore, D. L., Alexander, P. A., & Loughlin, S. M. (2008). Focusing the conceptual lens on metacognition, self-regulation, and self-regulated learning. Educational Psychology Review, 20(4), 391-409. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-008-9083-6

Dörrenbächer, L., & Perels, F. (2016). Self-regulated learning profiles in college students: Their relationship to achievement, personality, and the effectiveness of an intervention to foster self-regulated learning. Learning and Individual Differences, 51, 229-241. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2016.09.015

Dumfart, B., & Neubauer, A.C. (2016). Conscientiousness is the most powerful noncognitive predictor of school achievement in adolescents. Journal of Individual Differences, 37(1), 8-15. https://doi. org/10.1027/1614-0001/a000182

Farrington, C. A., Roderick, M., Allensworth, E., Nagaoka, J., Keyes, T. S., Johnson, D. W., & Beechum, N. O. (2012). Teaching adolescents to become learners: the role of noncognitive factors in shaping school performance: A critical literature review. Consortium on Chicago School Research.

Flavell, J. (1979). Metacognition and cognitive monitoring. A new area of cognitive-developmental inquiry. American Psychologist, 34(10), 906-911. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066x.34.10.906

Flavell, J. (1987). Speculation about nature and development of metacognition. En F. Weinert & R. Kluwe (Eds.), Metacognition, Motivación and Understanding (pp. 21–29). Hillsdale.

Flores-Lázaro, J. C., Ostrosky-Schejet, F., & Lozano-Gutiérrez, A. (2014). BANFE - 2. Batería neuropsicológica de funciones ejecutivas y lóbulos frontales. Manual Moderno.

Follmer, D. J., & Sperling, R. (2016). The mediating role of metacognition in the relationship between executive function and self-regulated learning. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 86(4), 1-17. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12123

Forsberg, A., Blume, C. L., & Cowan, N. (2021). The development of metacognitive accuracy in working memory across childhood. Developmental Psychology, 57(8), 1297-1317. https://doi.org/10.1037/dev0001213

Genise, G., Ungaretti, J., & Etchezahar, E. (2020). El Inventario de los Cinco Grandes Factores de Personalidad en el contexto argentino: puesta a prueba de los factores de orden superior Diversitas: Perspectivas en Psicología, 16(2), 325-340. https://doi.org/10.15332/22563067.6298

Geraci, L., Kurpad, N., Tirso, R., Gray, K. N., & Wang, Y. (2023). Metacognitive errors in the classroom: The role of variability of past performance on exam prediction accuracy. Metacognition and Learning, 18(1), 219-236. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-022-09326-7

Goldberg, L. (1992). The development of markers for the Big-Five factor structure. Psychological Assessment, (4), 26-42. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.4.1.26

Goldberg, L. (1993). The structure of phenotypic personality traits. American Psychologist, 48, 26-34. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.48.1.26

Goldberg, L., Johnson, J., Eber, H., Hogan, R., Ashton, M., Cloninger, R., & Gough, H. (2006). The international personality item pool and the future of public-domain personality measures. Journal of Research in Personality, 40, 84-96. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2005.08.007

Gunstone, R., & Mitchell, I. (1998). Metacognition and conceptual change. En J. Mintzes, J. Wandersee, & J. Novak (Eds.), Teaching science for understanding (pp. 133–163). Academic Press.

Gutierrez de Blume, A. P. (2022). Calibrating calibration: A meta-analysis of learning strategy interventions to improve metacognitive monitoring accuracy. Journal of Educational Psychology, 114(4), 681-700. https://doi.org/10.1037/edu0000674

Gutierrez de Blume, A. P., & Montoya Londoño, D. M. (2020). Relationship between personality factors and metacognition in a sample of students in the last semester of training in baccalaureate degree programs in education in Colombia. Educación y Humanismo, 22(39), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.17081/eduhum.22.39.4048

Gutierrez de Blume, A. P., & Montoya Londoño, D. M. (2021). Validation and examination of the factor structure of the Metacognitive Awareness Inventory (MAI) in Colombian university students. Psicogente, 24(46), 1-28. https://doi.org/10.17081/psico.24.46.4881

Gutierrez de Blume, A. P., & Montoya Londoño, D. M. (2022). Exploring the relation between executive functions (EFs) and metacognition: Do EFs predict metacognition? Praxis & Saber, 13(33), e12500. https://doi.org/10.19053/22160159.v13.n33.2022.12500

Gutierrez de Blume, A. P., & Montoya Londoño, D. M. (2023). Exploring the relation between metacognition, gender, and personality in Latin-American university students. Psykhe, 32(2), 1-21. https://doi.org/10.7764/psykhe.2021.30793

Gutierrez de Blume, A. P., Montoya Londoño, D. M., Daset, L., Cuadro, A., Molina Delgado, M., Morán Núñez, O., García de la Cadena, C., Beltrán Navarro, M. B., Arias Trejo, N., Ramirez Balmaceda, A., Jiménez Rodríguez, V., Puente Ferreras, A., Urquijo, S., Arias, W. L., Rivera, L. I., Schulmeyer, M., & Rivera-Sanchez, J. (2023). Normative data and standardization of an international protocol for the evaluation of metacognition in Spanish-speaking university students: A cross-cultural analysis. Metacognition and Learning, 18(2), 495-526. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-023-09338-x

Gutierrez de Blume, A. P., Montoya Londoño, D. M., Jiménez Rodríguez, V., Morán Núñez, O., Cuadro, A., Daset, L., Molina Delgado, M., García de la Cadena, C., Beltrán Navarro, M. B., Puente Ferreras, A., Urquijo, S., & Arias, W. L. (2024). Psychometric properties of the metacognitive awareness inventory (mai): Standardization to an international spanish with 12 countries. Metacognition and Learning. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-024-09388-9

Gutierrez de Blume, A. P., Montoya-Londoño, D. M., Landínez-Martínez, D., & Toro-Zuluaga, N. A. (2022). Las variables sociales y la conciencia meta-cognitiva de los jóvenes adultos colombianos. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 20(3), 700-731.https://doi.org/10.11600/rlcsnj.20.3.5379

Gutierrez, A. (2012). Enhancing the calibration accuracy of adult learners: A multifaceted intervention. University Libraries -University of Nevada- Las Vegas. https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations/1568/

Gutierrez, A. P., & Schraw, G. (2015). Effects of strategy training and incentives on students’ performance, confidence, and calibration. Journal of Experimental Education, 83(3), 386-404. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2014.907230

Hacker, D., & Bol, L. (2004). Metacognitive theory: Considering the social-cognitive influences. En D. McInerney & S. Van Etten (Eds.), Research on sociocultural influences on motivation and learning: Big theories revisited (pp. 275-297). Information Age Press.

Hacker, D., Bol, L., Horgan, D. D., & Rakow, E. A. (2000). Test prediction and performance in a classroom context. Journal of Educational Psychology, 92(1), 160-170. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.92.1.160

Händel, M., de Bruin, A. B. H., & Markus Dresel, M. (2020). Individual differences in local and global metacognitive judgments. Metacognition and Learning, 15(1), 51-75. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-020-09220-0

Irak, M. (2024). Effects of personality traits and mood induction on metamemory judgments and metacognitive beliefs. The Journal of General Psychology, 1-32. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.2024.2404396

Jacobs, J. E., & Paris, S. G. (1987). Children’s Metacognition about Reading: Issues in Definition, Measurement, and Instruction. Educational Psychologist, 22, 225-278. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.1987.9653052

Jiménez R., V., & Puente F., A. (2014). Modelo de estrategias metacognitivas. Revista de Investigación Universitaria, 3(1), 11-16.

Kelemen, W. L., Winningham, R. G., & Weaver, C. A. III. (2007). Repeated testing sessions and scholastic aptitude in college students' metacognitive accuracy. European Journal of Cognitive Psychology, 19(4-5), 689-717. https://doi.org/10.1080/09541440701326170

Kelly, D., & Donaldson, D. (2016). Investigating the complexities of academic success: Personality constrains the effects of metacognition. Psychology of Education Review, 40(2), 17-24.

Kleitman, S. (2008). Metacognition in the rationality debate. Self-confidence and its calibration. VDM Verlag Dr. Mueller.

Kleitman, S., & Stankov, L. (2001). Ecological and person-oriented aspects of metacognitive processes in test-taking. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 15(3), 321-341. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.705

Kleitman, S., & Stankov, L. (2007). Self-confidence and metacognitive processes. Learning and Individual Differences, 17(2), 161-173. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2007.03.004

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: How difficulties in recognizing one's own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 77(6), 1121-1134. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.77.6.1121

Ledesma, R., Sánchez, R., & Díaz-Lázaro, C. (2011). Adjective checklist to assess the Big Five personality factors in the Argentine population. Journal of Personality Assessment, 93(1), 46-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2010.513708

Lingjaerde, O., Regine Foreland, A., & Engvik, H. (2001). Personality structure in patients with winter depression, assessed in a depression –free state according to the five– factor model of personality. Journal of Affective Disorders, 62(3), 165-174.

Lyons, K. E., & Zelazo, P. D. (2011). Monitoring, metacognition, and executive function: Elucidating the role of self-reflection in the development of self-regulation. En B. B. Janette (Ed.), Advances in child development and behavior (Vol. 40, pp. 379-412). Elsevier Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-386491-8.00010-4

Miller, T. M., & Geraci, L. (2011). Training metacognition in the classroom: The influence of incentives and feedback on exam predictions. Metacognition and Learning, 6(3), 303-314. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409-011-9083-7

Ministerio de Educación Pública de Costa Rica. (2023). Ruta de la Educación 2022- 2023. Lineamientos técnicos de evaluación para el aprendizaje, 2023. Gobierno de Costa Rica. https://ddc.mep.go.cr/sites/all/files/ddc_mep_go_cr/adjuntos/lineamientos_tecnicos_evaluacion_v1.pdf

Mirels, H. L., Greblo, P., & Dean, J. B. (2002). Judgmental self-doubt: Beliefs about one’s judgmental prowess. Personality and Individual Differences, 33(5), 741-758. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(01)00189-1

Montoya, D. M., Tamayo, O. E., Orrego, M., & Dussan, C (2024). Monitoreo metacognitivo en el aula: Calibración y juicios metacognitivos en el aprendizaje. Universidad de Caldas.

Morosanova, V. I., Bondarenko, I. N., & Fomina, T. G. (2022). Conscious self-regulation, motivational factors, and personality traits as predictors of students’ academic performance: a linear empirical model. Psychology in Russia, 15(4), 170. https://doi.org/10.11621/pir.2022.0411

Moshman, D. (2017). Metacognitive theories revisited. Educational Psychology Review, 30(2), 599-606. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-017-9413-7

Nietfeld, J. L., Cao, L., & Osborne, J. W. (2006). The effect of distributed monitoring exercises and feedback on performance, monitoring accuracy, and self-efficacy. Metacognition and Learning, 1, 159-179. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10409-006-9595-6

Nietfeld, J. L., Cao, L., Osborne, J. W., & Osbourne, J. W. (2005). Metacognitive monitoring accuracy and student performance in the postsecondary classroom. The Journal of Experimental Education, 74(1), 7-28. https://doi.org/10.2307/20157410

Nietfeld, J., & Schraw, G. (2002). The effect of knowledge and strategy training on monitoring accuracy. Journal of Educational Research, 95(3), 131-142. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220670209596583

Nobutoshi, M. (2023). Metacognition and reflective teaching: a synergistic approach to fostering critical thinking skills. Research and Advances in Education, 2(9), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.56397/rae.2023.09.01

O’Connor, M.C., & Paunonen, S. V. (2007). Big Five personality predictors of post-secondary academic performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(5), 971-990. https://doi.org/10.1016/j. paid.2007.03.017

Öz, H. (2016). The importance of personality traits in students' perceptions of metacognitive awareness. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 232, 655-667. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.10.090

Özçakmak, H., Köroglu, M., Korkmaz, C., & Bolat, Y. (2021). The effect of metacognitive awareness on academic success. African Educational Research Journal, 9(2), 434-448. https://doi.org/10.30918/AERJ.92.21.020

Ozturk, N. (2020). An analysis of teachers’ metacognition and personality. Psychology and Education, 57(1), 40-44.

Ozturk, N. (2021). The Relation of metacognition, personality, and foreign language performance. International Journal of Psychology and Educational Studies, 8(3), 103-115. https://doi.org/10.52380/ijpes.2021.8.3.329

Pallier, G., Wilkinson, R., Danthiir, V., Kleitman, S., Knezevic, G., Stankov, L., & Roberts, R. (2002). The role of individual differences in the accuracy of confidence judgments. Journal of General Psychology, 129(3), 257-299. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221300209602099

Pesout, O., & Nietfeld, J. (2020). The impact of cooperation and competition on metacognitive monitoring in classroom context. The Journal of Experimental Education, 89(2), 237-258. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220973.2020.1751577

Ronningstam, E. (2005). Identifying and understanding the narcissistic personality. University Press.

Šafranj, J., Gojkov-Rajić, A., & Katić, M. (2021). Personality traits and students employment of metacognitive strategies in foreign language learning and achievement. Croatian Journal of Education: Hrvatski časopis za odgoj i obrazovanje, 23(2), 511-543. https://doi.org/10.15516/cje.v23i2.3213

Sánchez, R., & Ledesma, R. (2007). Los cinco grandes factores: cómo entender la personalidad y cómo evaluarla. En A. Monjeau (Ed.), Conocimiento para la transformación (Serie Investigación y Desarrollo, pp. 131-160). Ediciones Universidad Atlántida Argentina.

Sánchez, R., & Ledesma, R. (2013). Listado de adjetivos para evaluar la personalidad: Propiedades psicométricas y normas para una población argentina. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, 22(2), 147-160.

Sapancı, A., & Güler, A. (2021). The mediating role of metacognitive processes in the relationship between personality traits and academic achievement of university students. Sakarya University Journal of Education, 11(3), 501-525. https://doi.org/10.19126/suje.974304

Sawyer, R. K. (2019). The creative classroom: Innovative teaching for 21st-century learners. Teachers College Press.

Sawyer, R. K. (2022). An introduction to the learning sciences. En R. K. Sawyer (Ed.), The Cambridge handbook of the learning sciences (3a ed., pp. 1-24). Cambridge University Press.

Schaefer, P. S., Williams, C. C., Goodie, A. S., & Campbell, W. K. (2004). Overconfidence and the Big Five. Journal of Research in Personality, 38(5), 473-480. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2003.09.010

Schraw, G., & Dennison, R. S. (1994). Assessing metacognitive awareness. Contemporany Educational Psychology, 19(4), 460-475. https://doi.org/10.1006/ceps.1994.1033

Schraw, G., & Moshman, D. (1995). Metacognitive theories. Educational Psychology Review, 7(4), 351-371. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02212307

Schraw, G., Kuch, F., Gutierrez, A. P., & Richmond, A. (2014). Exploring a three-level model of calibration accuracy. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106, 1192-1202. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036653

Silver, N., Kaplan, M., LaVaque-Manty, D., & Meizlish, D. (Eds.) (2023). Using reflection and metacognition to improve student learning: Across the disciplines, across the academy. Taylor & Francis.

Soleimani, N., Nagahi, M., Nagahisarchoghaei, M., & Jaradat, R. (2018). The relationship between personality types and the cognitive-metacognitive strategies. Journal of Studies in Education, 8(2), 29-44. https://doi.org/10.5296/jse.v8i2.12767

Stankov, L. (2000). Complexity, metacognition, and fluid intelligence. Intelligence, 28(2), 121-143. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412963848.n110

Stankov, L., & Crawford, J. (1996). Confidence judgments in studies of individual differences. Personality and Individual Differences, 21(6), 971-986. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(96)00130-4

Stankov, L., & Crawford, J. (1997). Self-confidence and performance on tests of cognitive abilities. Intelligence, 25(2), 93-109. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-2896(97)90047-7

Stankov, L., Morony, S., & Lee, Y. P. (2014). Confidence: The best non-cognitive predictor of academic achievement? Educational Psychology, 34(1), 9-28. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2013.814194

Stanton, J. D., Sebesta, A. J., & Dunlosky, J. (2021). Fostering metacognition to support student learning and performance. CBE—Life Sciences Education, 20(2), 20-27. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.20-12-0289

Swanson, H. J., Ojutiku, A., & Dewsbury, B. (2024). The Impacts of an academic intervention based in metacognition on academic performance. Teaching & Learning Inquiry, 12. https://doi.org/10.20343/teachlearninqu.12.12

Tabachnick, B. G., & Fidell, L. S. (2019). Using multivariate statistics (7a ed.). Pearson. https://www.pearson.com/us/higher-education/program/Tabachnick-Using-Multivariate-Statistics-7th-Edition/PGM2458367.html

Thiede, K. W., Oswalt, S., Brendefur, J. L., Carney, M. B., & Osguthorpe, R. D. (2019). Teachers' judgments of student learning of mathematics. En J. Dunlosky & K. A. Rawson (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of cognition and education (pp. 678–695). Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/9781108235631.027

Tobias, S., & Everson, H. (2009). The importance of knowing what you know: A knowledge monitoring framework for studying metacognition in education. En D. J. Hacker, J. Dunlosky, & A. Graesser (Eds.): Handbook of Metacognition in Education (pp. 107–228). Routledge.

Topping, K. J. (2024). Improving thinking about thinking in the classroom: What works for enhancing metacognition. Taylor & Francis.

Veenman, M. V. (2015). Metacognition. En P. Afflerbach (Ed.), Handbook of Individual Differences in Reading. Reader, Text, and Context (pp. 26-40). Routledge.

Veenman, M. V. J., Van Hout-Wolters, B. H. A. M., & Afflerbach, P. (2006). Metacognition and learning: Conceptual and methodological considerations. Metacognition and Learning, 1(1), 3-14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11409- 006-6893-0

Wang, M. C., Haertel, G. D., & Walberg, H. J. (1990). What influences learning? A content analysis of review literature. The Journal of Educational Research, 84(1), 30-43. https://doi.org/10.1080/00220671.1990.10885988

Want, J., & Kleitman, S. (2006). Imposter phenomenon and self-handicapping: Links with parenting styles and self-confidence. Personality and Individual Differences, 40(5), 961-971. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2005.10.005

Weaver, C. A. (1990). Constraining factors in calibration of comprehension. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Learning, Memory, and Cognition, 16(2), 214-222. https://doi.org/10.1037/0278-7393.16.2.214

Wolfe, R. N., & Grosch, J. W. (1990). Personality correlates of confidence in one’s decisions. Journal of Personality, 58(3), 515-534. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.1990.tb00241.x

Wongdaeng, M. (2022). Evaluation of metacognitive and self-regulatory programmes for learning, pedagogy and policy in tertiary EFL contexts (Tesis doctoral inédita). Durham University.

Yang, C., Zhao, W., Yuan, B., Luo, L., & Shanks, D. R. (2023). Mind the gap between comprehension and metacomprehension: Meta-analysis of metacomprehension accuracy and intervention effectiveness. Review of Educational Research, 93(2), 143-194. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543221094083

Zapata-Zapata, A., Vesga Bravo, G. J., Puente Ferreras, A., & Alvarado Izquierdo, J. M. (2024). Juicios metacognitivos en los procesos de aprendizaje en la educación superior: una revisión sistemática 2018-2023. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 56(15), 147-155. https://doi.org/10.14349/rlp.2024.v56.15

Zimmerman, B., & Moylan, A. (2009). Self -regulation: where metacognition and motivation intersect. En D. J. Hacker, J. Dunlosky & A. Grasser (Eds.), Handbook of Metacognition in Education (pp. 239-315). Routledge.

Zohar, A., & Dori, Y. (2012). Metacognition in Science education. Trends in current research. Springer.

Zsigmond, I., Metallidou, P., Misailidi, P., Iordanou, K., & Papaleontiou-Louca, E. (2025). Metacognitive monitoring in written communication: Improving reflective practice. Education Sciences, 15(3), 299. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci15030299

Disponibilidad de datos: El conjunto de datos que apoya los resultados de este estudio no se encuentra disponible.

Financiamiento: Este estudio no recibió ninguna financiación externa ni apoyo financiero.

Conflicto de interés: Los autores declaran no tener ningún conflicto de interés.

Cómo citar: Gutierrez de Blume, A. P., Montoya Londoño, D. M., Daset, L., Cuadro, A., Molina Delgado, M., Morán Núñez, O., Urquijo, S., & Giuliani, M. F. (2025). Relación entre factores de personalidad y el conocimiento y la regulación metacognitiva en una muestra de estudiantes universitarios de diferentes países de habla hispana. Ciencias Psicológicas, 19(1), e-4122. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v19i1.4122

Contribución de los autores (Taxonomía CRediT): 1. Conceptualización; 2. Curación de datos; 3. Análisis formal; 4. Adquisición de fondos; 5. Investigación; 6. Metodología; 7. Administración de proyecto; 8. Recursos; 9. Software; 10. Supervisión; 11. Validación; 12. Visualización; 13. Redacción: borrador original; 14. Redacción: revisión y edición.

A. P. G. de B. ha contribuido en 1, 2, 3, 6, 10, 14; D. M. M. L. en 5, 7, 13, 14; L. D. en 5, 14; A. C. en 5, 14; M. M. D. en 5, 14; O. M. N. en 5, 14; S. U. en 5, 14; M. F. G. en 5, 14.

Editora científica responsable: Dra. Cecilia Cracco.

Ciencias Psicológicas, v19(1)

January-June 2025

10.22235/cp.v19i1.4122

Original Articles

Relation between Personality and Metacognitive Regulation in a Sample of University Students from Different Countries in Latin America

Relación entre factores de personalidad y el conocimiento y la regulación metacognitiva en una muestra de estudiantes universitarios de diferentes países de habla hispana

Relação entre fatores de personalidade e o conhecimento e a regulação metacognitiva em uma amostra de estudantes universitários de diferentes países de língua espanhola

Antonio P. Gutierrez de Blume1, ORCID 0000-0001-6809-1728

Diana Marcela Montoya Londoño2, ORCID 0000-0001-8007-0102

Lilián Daset3, ORCID 0000-0002-5119-324X

Ariel Cuadro4, ORCID 0000-0002-4429-9898

Mauricio Molina Delgado5, ORCID 0000-0003-4335-3095

Olivia Morán Núñez6, ORCID 0009-0007-6206-9619

Sebastián Urquijo7, ORCID 0000-0002-8315-9329

María Florencia Giuliani8, ORCID 0000-0002-5892-4527

1 Georgia Southern University, United States, [email protected]

2 Universidad de Caldas; Universidad de Manizales, Colombia

3 Universidad Católica de Uruguay, Uruguay

4 Universidad Católica de Uruguay, Uruguay

5 Universidad de Costa Rica, Costa Rica

6 Universidad de Panamá, Panama

7 Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, Argentina

8 Universidad Nacional de Mar del Plata, Argentina

Abstract:

This research investigates the relationship between personality factors and metacognition in a sample of undergraduate students from Argentina, Colombia, Costa Rica, Panama, and Uruguay. Recognizing the interdisciplinary nature of cognitive science, the study emphasizes the importance of metacognitive abilities—considered executive functions—on academic performance. The sample consisted of 692 students, aged 20 to 30, from various undergraduate programs. Participants completed the Metacognitive Awareness Inventory (MAI) and the Adjective Checklist for Evaluating Personality (AEP). The analysis used multiple regression to examine the relationship between the five major personality factors and eight metacognitive variables across the five countries. Results indicated significant associations between personality traits and metacognitive components, with conscientiousness and openness to new experiences consistently predicting metacognitive regulation and knowledge. These findings align with previous studies suggesting that personality traits influence metacognitive abilities. The study contributes to the understanding of how individual differences in personality can affect learning processes, highlighting the potential for targeted interventions to enhance metacognitive skills.

Keywords: learning; metacognition; personality; university students; cross cultural studies.

Resumen:

Esta investigación examina la relación entre los factores de personalidad y la metacognición en una muestra de estudiantes de pregrado de Argentina, Colombia, Costa Rica, Panamá y Uruguay. A partir de la naturaleza interdisciplinaria de la ciencia cognitiva, el estudio enfatiza la importancia de las habilidades metacognitivas, consideradas como funciones ejecutivas fundamentales en el desempeño académico. La muestra se conformó por 692 estudiantes, de 20 a 30 años, de diversos programas de pregrado. Los participantes completaron el Inventario de conciencia metacognitiva (MAI) y el Listado de adjetivos para evaluar la personalidad (AEP). En el análisis se utilizó regresión múltiple para examinar la relación entre los cinco grandes factores de personalidad y ocho variables metacognitivas en los cinco países. Los resultados indicaron asociaciones significativas entre los factores de personalidad y los componentes metacognitivos, con la escrupulosidad y la apertura prediciendo consistentemente la regulación y el conocimiento metacognitivo. Estos hallazgos se alinean con estudios previos que sugieren que los factores de personalidad influyen en las habilidades metacognitivas. El estudio contribuye a la comprensión de cómo las diferencias individuales en la personalidad pueden afectar los procesos de aprendizaje, destacando el potencial de intervenciones dirigidas para mejorar las habilidades metacognitivas.

Palabras clave: aprendizaje; metacognición; personalidad; estudiantes universitarios; estudios transculturales.

Resumo: