Ciencias Psicológicas, 18(2)

julio-diciembre 2024

10.22235/cp.v18i2.3756

Relaciones entre perfeccionismo disfuncional y estrés escolar en estudiantes de nivel primario de Posadas (Argentina)

Relationships between dysfunctional perfectionism and school stress in primary school students in Posadas (Argentina)

Relações entre perfeccionismo disfuncional e estresse escolar em estudantes do nível primário de Posadas (Argentina)

Sonia Noemí Chemisquy1, ORCID 0000-0002-3820-3036

Luana Natahela Arévalo2, ORCID 0000-0002-6926-8086

Milagros Mercedes Penz Picaza3, ORCID 0009-0007-7978-8097

1 Universidad Católica de las Misiones, Argentina, [email protected]

2 Universidad Católica de las Misiones, Argentina

3 Universidad Católica de las Misiones, Argentina

Resumen:

Aunque es conocido que el perfeccionismo desadaptativo tiene consecuencias negativas en la vida académica, hasta el momento no se hallaron trabajos científicos que estudien el estrés escolar en relación con las tres dimensiones del perfeccionismo multidimensional (i. e., autorientado, socialmente prescrito y orientado a otros). El objetivo de este trabajo fue analizar el rol predictor del perfeccionismo disfuncional en el estrés escolar de estudiantes de nivel primario y valorar la contribución diferencial de cada una de sus dimensiones. Se realizó un estudio cuantitativo, transversal y correlacional con n = 226 estudiantes de escuelas primarias de la ciudad de Posadas, Argentina. Los resultados sugieren que el perfeccionismo predice el estrés escolar en un 31.9 %, sobre todo en las dimensiones autorientada y socialmente prescrita. En el análisis de regresión multivariada, el perfeccionismo autorientado contribuyó al estrés emocional y a la tensión interpersonal, el perfeccionismo socialmente prescrito predijo las tres dimensiones del estrés escolar, mientras que el perfeccionismo orientado a otros solo predijo la tensión interpersonal. Estos resultados son acordes al modelo teórico de base y aportan información relevante para profundizar el conocimiento de la dinámica del perfeccionismo infantil en el nivel primario de la escuela.

Palabras clave: perfeccionismo; estrés académico; educación primaria; tercera infancia.

Abstract:

Although it is known that maladaptive perfectionism leads to negative consequences in academic life, so far, no scientific work has been found that studies school stress in relation to the three dimensions of multidimensional perfectionism (i. e., self-directed, socially prescribed, and other-oriented). The aim of this paper was to analyze the predictive role of dysfunctional perfectionism in school stress in primary school students and to assess the differential contribution of each of its dimensions. A quantitative, cross-sectional, and correlational study was conducted with n = 226 students from primary schools in the city of Posadas, Argentina. The results suggest that perfectionism predicts school stress by 31.9 %, especially in the self-directed and socially prescribed dimensions. In multivariate regression analysis, self-oriented perfectionism contributed to emotional stress and interpersonal tension, socially prescribed perfectionism predicted all three dimensions of school stress, while other-oriented perfectionism only predicted interpersonal tension. These results are in line with the underlying theoretical model and provide relevant information to deepen the understanding of the dynamics of children's perfectionism at the primary school level.

Keywords: perfectionism; school stress; primary education; middle childhood.

Resumo:

Embora se saiba que o perfeccionismo desadaptativo conduz a consequências negativas na vida acadêmica, até o momento, não foram encontrados trabalhos científicos que estudem o estresse escolar em relação às três dimensões do perfeccionismo multidimensional (i. e., auto-orientado, socialmente prescrito e orientado para os outros). O objetivo deste trabalho foi analisar o papel preditivo do perfeccionismo disfuncional no estresse escolar de estudante do nível primário e avaliar a contribuição diferencial de cada uma de suas dimensões. Foi realizado um estudo quantitativo, transversal e correlacional com n = 226 estudantes de escolas primárias da cidade de Posadas, Argentina. Os resultados sugerem que o perfeccionismo prediz o estresse escolar em 31,9 %, especialmente nas dimensões auto- orientada e socialmente prescrita. Na análise de regressão multivariada, o perfeccionismo auto-orientado contribuiu para o estresse emocional e para a tensão interpessoal; o perfeccionismo socialmente prescrito prediz as três dimensões do estresse escolar, enquanto o perfeccionismo orientado para os outros apenas prediz a tensão interpessoal. Estes resultados estão de acordo com o modelo teórico de base e fornecem informações relevantes para aprofundar o conhecimento da dinâmica do perfeccionismo infantil no nível primário escolar.

Palavras-chave: perfeccionismo; estresse acadêmico; educação primária; terceira infância.

Recibido: 13/11/2024

Aceptado: 21/03/2024

El perfeccionismo es definido por Hewitt y Flett (1991) como la tendencia a establecer y perseguir estándares elevados y poco realistas. Según estos autores, las demandas rígidas de perfección y las preocupaciones por ser o aparentar dicha perfección pueden partir de diversas fuentes y destinarse a distintos objetivos, lo que permite distinguir tres dimensiones: (a) perfeccionismo autorientado, donde la exigencia de perfección parte de y se destina a uno mismo; (b) perfeccionismo socialmente prescrito, que involucra la creencia de que los demás demandan no menos que la perfección; y (c) perfeccionismo orientado a otros, donde la exigencia parte del yo y los destinatarios son los demás (Smith et al., 2022).

Numerosos estudios científicos han abordado las consecuencias del perfeccionismo desadaptativo durante los años infantiles y las evidencias indican que este atributo conduce a problemas en diversas áreas del desarrollo de los niños. En este sentido, por ejemplo, durante la infancia, algunos aspectos del perfeccionismo interpersonal (i. e., autopresentación perfeccionista) se relacionan con el malestar físico (Sánchez-Rodríguez et al., 2021). Por otro lado, aunque también en población infantojuvenil, el perfeccionismo se relaciona con depresión (Asseraf & Vaillancourt, 2015), ansiedad (Ferrer et al., 2018), síntomas asociados a trastornos de la conducta alimentaria (Bills et al., 2023), autolesiones (Gyori & Balazs, 2021), entre otros problemas de salud mental. También se hallaron evidencias que indican que el perfeccionismo aumenta la vulnerabilidad de niños y niñas, convirtiéndose en un factor de riesgo que puede predisponer a la aparición de problemas más graves. En esta línea se encontró que algunos aspectos del perfeccionismo desadaptativo infantil (i. e., un perfil combinado de perfeccionismo autorientado y socialmente prescrito) se relacionan con una mayor presencia de hostilidad, agresión verbal y física, e ira (Vicent et al., 2017), mientras que elevados niveles de perfeccionismo socialmente prescrito llevan a estados emocionales negativos y pensamientos patológicos (Gonzálvez et al., 2015). Específicamente en el área interpersonal, se encontró que las tres dimensiones del perfeccionismo aumentan la soledad con relación a los pares y disminuyen la percepción de apoyo social en niños y niñas (Chemisquy & Oros, 2020).

En este sentido, uno de los modelos que pretende explicar las salidas desadaptativas del perfeccionismo es el de la vulnerabilidad al estrés (Hewitt & Flett, 1993; 2002), que postula que este atributo puede influenciar o interactuar con el estrés para producir o mantener estados psicopatológicos, ya sea porque las personas perfeccionistas experimentan niveles elevados de estrés y/o porque tienen maneras negativas de reaccionar a este. Existen evidencias que apoyan este modelo: por ejemplo, se halló que las dimensiones autorientada y socialmente prescrita se relacionan con una peor salud física por intermedio del estrés percibido (Molnar et al., 2012). De modo similar, se encontró que el vínculo entre perfeccionismo socialmente prescrito y depresión puede estar mediado por una elevada reactividad ante el estrés (Flett, Nepon et al., 2016).

Curiosamente, en lo que refiere a la vida escolar, el perfeccionismo autorientado puede impactar positivamente en el rendimiento académico (Harvey et al., 2017) y en la autoeficacia en matemáticas (Ford et al., 2023). Por otra parte, las evidencias sugieren que los niños perfeccionistas tienden a experimentar una mayor ansiedad escolar que sus pares no perfeccionistas (Inglés et al., 2016), y que aquellos con elevados niveles de perfeccionismo socialmente prescrito pueden incluso experimentar un mayor rechazo escolar (Gonzálvez et al., 2015). Así también se encontró que algunos aspectos del perfeccionismo pueden dar lugar a mayores niveles de estrés en el ámbito escolar y de aprendizaje (Yang & Chen, 2015).

El estrés escolar es definido por Martínez Díaz y Díaz Gómez (2007) como “el malestar que el estudiante presenta debido a factores físicos, emocionales, ya sea de carácter interrelacional o intrarrelacional, o ambientales que pueden ejercer una presión significativa en la competencia individual para afrontar el contexto escolar en términos de rendimiento académico” (p. 14). Acorde con esto, Bringhenti (1996) menciona que el estrés escolar incluye desmotivación, agotamiento emocional, dificultades interpersonales y escasa satisfacción en la escuela.

Investigaciones previas hallaron que el perfeccionismo desadaptativo predice mayores niveles de distrés en estudiantes de los últimos años del nivel medio (Wuthrich et al., 2020) e incluso puede contribuir al desarrollo de algunos aspectos del burnout académico (i. e., cinismo y agotamiento emocional) en adolescentes que cursan dicho nivel educativo (Seong et al., 2021). En cuanto a las facetas del perfeccionismo, se encontró que tanto la autorientada como la socialmente prescrita se asocian al estrés educativo y a algunas de sus dimensiones: presión por estudiar, preocupación por las calificaciones, expectativas elevadas y malestar o abatimiento en relación con el estudio (Flett, Hewitt et al., 2016). Específicamente en población de estudiantes de nivel primario, se encontraron estudios latinoamericanos que indican que el perfeccionismo autorientado aumenta el estrés familiar y escolar (Aguilar Durán, 2019; Barba, 2019).

Un estudio español reciente realizado con estudiantes de nivel secundario encontró que el perfeccionismo autorientado y las expectativas parentales se relacionan con niveles más elevados de estrés escolar en las siguientes dimensiones: estrés por el desempeño escolar, por el temor a la incertidumbre y por el conflicto entre escuela y ocio. Este trabajo también obtuvo evidencias acerca del rol moderador del perfeccionismo autorientado en la relación entre estrés escolar (i. e., conflicto escuela-ocio) y quejas somáticas (Díez et al., 2023).

Como se puede observar en esta breve revisión de antecedentes, la mayoría de los trabajos reseñados abordan el estudio del perfeccionismo autorientado y/o socialmente prescrito, pero hasta el momento no se hallaron trabajos científicos que estudien el estrés escolar en relación con las tres dimensiones propuestas por el modelo de Hewitt y Flett (1991), lo que indica una laguna en la investigación sobre la temática.

En virtud de lo antedicho, este trabajo estuvo destinado a analizar el rol predictor del perfeccionismo disfuncional infantil en el estrés escolar. Profundizar en la dinámica de esta relación y estudiar la contribución diferencial de cada una de las dimensiones del perfeccionismo en el estrés escolar de estudiantes del nivel primario puede ser de gran relevancia a nivel científico y práctico, teniendo en cuenta que los hallazgos recientes indican que el estrés académico es un mediador parcial de la relación entre el perfeccionismo, la ansiedad y la depresión (Gil et al., 2023).

Método

Tipo de estudio

Se realizó un estudio cuantitativo, de corte transversal y alcance correlacional.

Participantes

Se llevó a cabo un muestreo no probabilístico, por conveniencia, de acuerdo con la posibilidad de acceso de las investigadoras a las diversas instituciones escolares. La muestra resultante quedó conformada por n = 226 estudiantes de escuelas primarias de la ciudad de Posadas, Argentina. Del total de la muestra 60.2 % eran niñas, 54 % se encontraba cursando el sexto grado y el resto cursaba séptimo grado. La edad media fue de 11.58 (DE = .67).

Instrumentos

Para evaluar el perfeccionismo autorientado se utilizó la Escala de Perfeccionismo Infantil (Oros, 2003). Este instrumento autoadministrable posee 16 reactivos construidos con un escalamiento tipo Likert, de tres respuestas alternativas (1: no lo pienso/no; 2: lo pienso a veces/a veces; 3: lo pienso/sí), que permiten evaluar la faceta autorientada del perfeccionismo en dos subdimensiones de ocho ítems cada una: autodemandas, destinada a evaluar las exigencias impuestas a uno mismo (por ejemplo: “Necesito ser el mejor”; “Debo ganar siempre”); y reacciones desadaptativas ante el fracaso, que evalúa las formas de responder ante los fracasos percibidos (por ejemplo: “Pienso mucho en las equivocaciones que tuve”; “Me critico mucho a mí mismo”). En este trabajo se utilizó únicamente el valor total de la escala para representar la faceta de perfeccionismo autorientado sin diferenciar sus factores.

Las dimensiones interpersonales del perfeccionismo se evaluaron con la Escala de Perfeccionismo Social Infantil (Oros et al., 2019), que aporta información sobre las dos dimensiones interpersonales del perfeccionismo: el socialmente prescrito, compuesto por nueve ítems que evalúan la creencia de que los demás esperan desempeños perfectos (por ejemplo: “Mi familia quiere que yo sea perfecto”; “Mis maestros no aceptan que yo cometa errores”); y orientado a otros, compuesto por siete ítems que evalúan las demandas de perfección impuestas a los demás (por ejemplo: “Me enojo con mis amigos cuando no quieren sacar notas altas”; “Trato de juntarme con los más inteligentes”). Este cuestionario también es autoadministrable, con formato tipo Likert, y consta de tres opciones de respuesta (1: no, 2: a veces y 3: sí). La escala aporta dos valores que representan cada una de las facetas interpersonales del perfeccionismo; estos valores se consideran de forma independiente sin calcular un puntaje total.

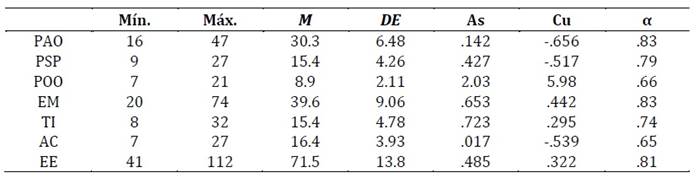

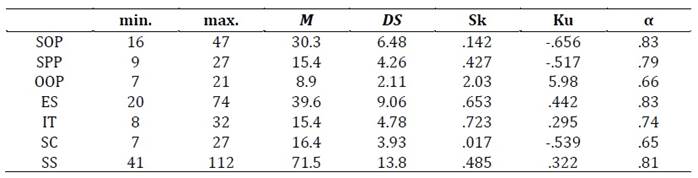

Estas dos escalas evalúan el perfeccionismo con base en el modelo multidimensional propuesto por Hewitt y Flett (1991). Recientemente se estudió el funcionamiento de ambos instrumentos en simultáneo y se obtuvieron propiedades psicométricas adecuadas: el análisis factorial confirmatorio arrojó un buen ajuste al modelo teórico de base, de tres factores (AGFI = .94; CFI = .93; RMSEA .048; SRMR = .039), y la consistencia interna resultó óptima, de acuerdo con los valores de omega de McDonald (perfeccionismo autorientado = .78; socialmente prescrito = .82; y orientado a otros = .71) (Oros et al., 2023). Los valores de alfa de Cronbach en este estudio indican una adecuada consistencia interna, como se observa en la Tabla 1.

Para evaluar el estrés escolar, se utilizó el Cuestionario de Estrés Escolar (QSS por su sigla en inglés) de Bringhenti (1996), que, al igual que los anteriores, es un cuestionario autoadministrable, que se compone de 35 ítems, con formato Likert, con cuatro opciones de respuesta (1: nunca, 2: a veces, 3: casi siempre y 4: siempre). Este instrumento mide el estrés escolar a partir de tres subescalas: (a) escala emocional, compuesta de 20 ítems, que evalúa las manifestaciones relacionadas con el agotamiento emocional, la desmotivación y la insatisfacción vinculados con la escuela, el estudio y los docentes (por ejemplo: “Tengo miedo de que la escuela me interese cada día menos”; “Me siento muy cansado por el trabajo escolar”); (b) escala de tensión interpersonal, formada por ocho ítems que miden las dificultades interpersonales, la sensación de fastidio y la hostilidad en relación con algunos integrantes del grupo-clase (por ejemplo: “Estar entre mis compañeros me pone tenso y nervioso”; “Tengo miedo de que la relación con mis compañeros se vuelva cada día más difícil”); y (c) escala de autoconcepto, con siete ítems que recogen información acerca de aspectos sociales de la autoestima y de la adaptación escolar (por ejemplo: “Me siento a gusto en mi curso y en la escuela”; “Me siento útil al resolver los problemas dados por los maestros”). La escala permite obtener tres puntajes parciales, que representan cada dimensión, y un valor total, que representa el estrés escolar. La consistencia interna de la escala total y de cada una de las subescalas fue muy buena, tal como se observa en la Tabla 1.

Procedimiento de recolección y análisis de datos

Posterior a la evaluación favorable del Comité de Ética de la Provincia de Misiones, se realizó el contacto con los directivos de las diferentes instituciones educativas de nivel primario de la ciudad de Posadas, tanto públicas como privadas, para invitar a los estudiantes de sexto y séptimo grado a participar en esta investigación. Una vez que se logró el aval institucional, se entregaron los consentimientos informados a directivos y/o docentes para ser repartidos a los estudiantes a fin de obtener la aprobación de los tutores legales. A los estudiantes que tenían el consentimiento firmado se les administró los cuestionarios, previa explicación de los objetivos del estudio y de su asentimiento verbal. La recolección de datos se llevó a cabo de manera presencial, grupal y en formato papel, en presencia de los investigadores para minimizar errores de comprensión.

Luego de la recolección, los datos obtenidos fueron cargados en el software estadístico jamovi v. 2.4.8. Para el análisis, se calcularon los puntajes totales de las escalas y subescalas para construir los indicadores de cada variable y la confiabilidad de las escalas a partir de su consistencia interna (alfa de Cronbach). En segundo lugar, se llevaron a cabo análisis estadísticos descriptivos de las escalas y subescalas: medias, desviación estándar, mínimos, máximos, e índices de asimetría y curtosis. Luego se procedió al análisis de correlaciones bivariadas, utilizando el estadístico r de Pearson y valorando el tamaño del efecto de acuerdo con las indicaciones de Funder y Ozer (2019). Estos autores sugieren que valores r de .05 representan un tamaño del efecto muy pequeño para la explicación de acontecimientos, mientras que un r de .10 indicaría un efecto que, aunque puede ser pequeño a nivel de eventos individuales, puede resultar potencialmente más relevante. Asimismo, un valor r de .20 supone un efecto de tamaño medio que puede resultar explicativo y práctico incluso a corto plazo, valores de r de .30 indicarían un tamaño de efecto grande y potencialmente potente, tanto a corto como a largo plazo, y, por último, valores de r de .40 o superiores representan tamaños del efecto muy grandes.

En el siguiente paso se realizó una regresión lineal múltiple, en la que las tres dimensiones del perfeccionismo fueron las variables independientes y el estrés escolar, considerado a partir del puntaje total en el QSS, fue la variable dependiente. Finalmente se llevó a cabo una regresión multivariada por medio de un análisis de path, utilizando el módulo PATH, que se basa en el paquete Lavaan de R (Gallucci, 2021; Rosseel, 2011). Debido a que no se hallaron desviaciones importantes de la normalidad uni y multivariada en los datos, se seleccionó el método de estimación de máxima verosimilitud, y se puso a prueba un modelo en el que se introdujeron las tres dimensiones del perfeccionismo como variables exógenas y las tres subescalas del estrés escolar como variables endógenas. Para valorar el modelo se utilizaron los siguientes criterios: valores de x2/gl ≤ 5.00 (West et al., 2012), CFI y AGFI ≥ .95 (Brown, 2006; Hu & Bentler, 1999), SRMR ≤ .08 (Hooper et al., 2008). En este estudio no se consideró el valor RMSEA, dado que el modelo puesto a prueba posee pocos grados de libertad (Kenny et al., 2014). Los coeficientes de determinación (r2) fueron transformados en f² para contrastar los tamaños de efecto con el criterio de Cohen (1992).

Resultados

Antes de proceder a los análisis se revisaron los datos perdidos y se encontraron únicamente datos faltantes a nivel del ítem que correspondían a omisiones de los participantes. Para abordar este problema se utilizó la estrategia de reemplazar los valores ausentes con la moda del participante en la subescala correspondiente (Cichosz, 2015). El análisis de casos atípicos univariados reveló la presencia de participantes con puntajes Z superiores a ± 3.29 en la dimensión orientada a otros del perfeccionismo (tres casos) y en las dimensiones emocional y tensión interpersonal del estrés escolar (uno y dos casos, respectivamente). Por otra parte, no se hallaron casos atípicos a nivel multivariado por medio del análisis de la distancia de Mahalanobis (p < .001) (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). Los índices de asimetría y curtosis en la mayoría de los casos no superan el valor de ±1, lo que da cuenta de una apropiada normalidad univariada (George & Mallery, 2011). La dimensión orientada a los otros es la única excepción en la que se pueden ver valores aceptables de asimetría, pero la curtosis es muy elevada, aunque este parece ser el comportamiento habitual de la variable (Chemisquy et al., 2019; Oros et al., 2023). El análisis de normalidad multivariada arrojó un valor del coeficiente de Mardia = 12.31, que se puede considerar aceptable y justifica la utilización del método de máxima verosimilitud para estimar los parámetros (Rodríguez Ayán & Ruiz Díaz, 2008).

Los resultados de los análisis estadísticos descriptivos y de consistencia interna de las subescalas pueden ser consultados en la Tabla 1.

Tabla 1: Puntajes mínimos y máximos, media, desviación típica, asimetría, curtosis y alfa de Cronbach para cada dimensión evaluada

Nota: PAO: perfeccionismo autorientado; PSP: perfeccionismo socialmente prescrito; POO: perfeccionismo orientado a otros; EM: estrés emocional; TI: tensión interpersonal; AC: autoconcepto; EE: estrés escolar.

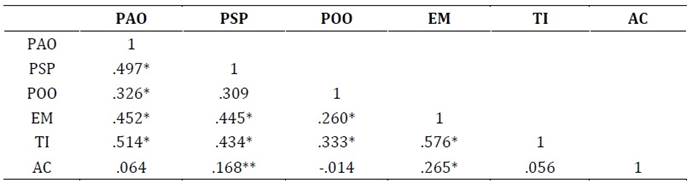

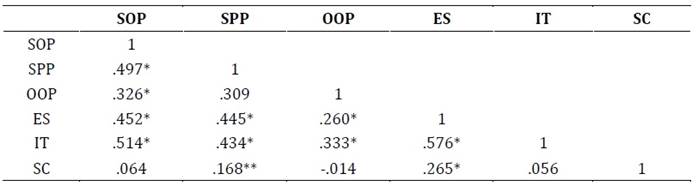

En la Tabla 2 se encuentran los valores del análisis de correlaciones, en los que se halló que las tres dimensiones del perfeccionismo obtuvieron asociaciones estadísticamente significativas y positivas con el estrés escolar considerado en su totalidad. La dimensión autorientada obtuvo una relación de gran tamaño (r = .491; p < .001), al igual que la socialmente prescrita (r = .490; p < .001). Sin embargo, la dimensión del perfeccionismo orientado a otros obtuvo una relación de tamaño medio (r = .281; p < .001). Esto indica que el estrés escolar aumenta a medida que aumenta el perfeccionismo autorientado, socialmente prescrito y/u orientado a los otros, y viceversa.

Por otro lado, el perfeccionismo autorientado y el socialmente prescrito ostentaron relaciones estadísticamente significativas, positivas y de gran tamaño con el estrés emocional. El perfeccionismo orientado a otros también obtuvo una relación estadísticamente significativa y positiva con esta subdimensión del estrés escolar, pero en este caso el tamaño del efecto obtenido fue medio. Las tres dimensiones del perfeccionismo también correlacionaron de manera positiva, estadísticamente significativa y con tamaños del efecto grandes a muy grandes con la dimensión de tensión interpersonal del estrés escolar.

Solo el perfeccionismo socialmente prescrito obtuvo una relación estadísticamente significativa con el estrés basado en el autoconcepto. En este caso, la relación resultó positiva y de tamaño del efecto pequeño, aunque potencialmente relevante.

Cabe destacar que los valores hallados indican que las variables no presentan colinealidad ya que en todos los casos r < .85 (Cupani, 2012).

Tabla 2: Correlaciones bivariadas (r de Pearson) entre las dimensiones de perfeccionismo y las subescalas de estrés escolar

Nota: PAO: perfeccionismo autorientado; PSP: perfeccionismo socialmente prescrito; POO: perfeccionismo orientado a otros; EM: estrés emocional; TI: tensión interpersonal; AC: autoconcepto.

* p < .001; ** p = .011.

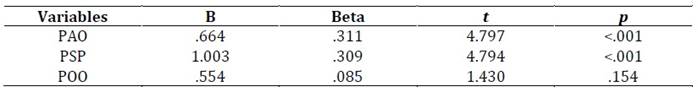

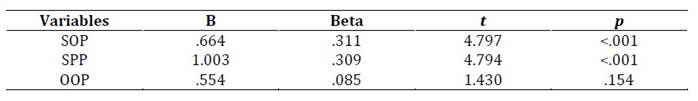

En la regresión lineal múltiple se halló que el perfeccionismo predice el estrés escolar en un 31.9 % (F(3,222) = 36.160; p < .001). Como se observa en la Tabla 3, las contribuciones de las dimensiones autorientada y socialmente prescrita resultaron estadísticamente significativas, en tanto que el perfeccionismo orientado a otros no ostentó significación estadística en este análisis.

Tabla 3: Regresión lineal entre estrés escolar y las dimensiones del perfeccionismo

Nota: PAO: perfeccionismo autorientado; PSP: perfeccionismo socialmente prescrito; POO: perfeccionismo orientado a otros.

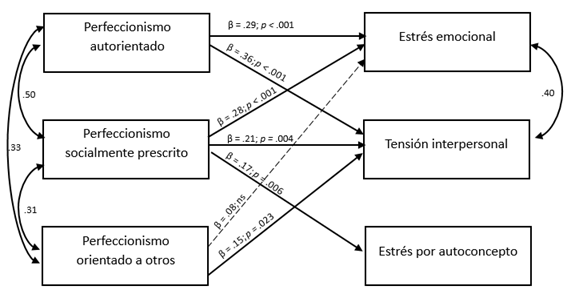

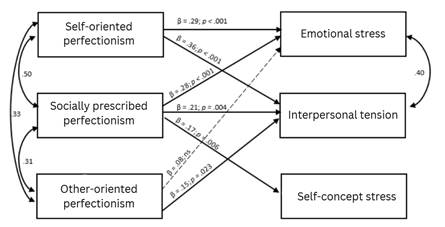

Para finalizar se puso a prueba el modelo de regresiones multivariadas por medio de un análisis de path. Para diseñar el modelo se tomaron en cuenta las asociaciones observadas en las correlaciones y la regresión lineal múltiple, por lo que se establecieron relaciones entre las tres dimensiones del perfeccionismo con el estrés emocional y la tensión interpersonal, mientras que únicamente se estableció una asociación entre el perfeccionismo socialmente prescrito y el estrés por autoconcepto. El modelo obtuvo valores de ajuste y error considerados adecuados (x2 = 17.3; gl = 4; p = .002; x2/gl = 4.32; CFI = .938; AGFI = .990; SRMR = .0039). Explicó un 27.5 % (r2 = .275) del estrés emocional y un 32.7 % (r2 = .327) de la tensión interpersonal, lo que indica tamaños del efecto grandes (f² = .38 y .49, respectivamente). Por otro lado, indicó un 2.8 % (r2 = .028) del estrés relacionado con la autoestima, que se traduce en un tamaño del efecto pequeño (f² = .03).

En la Figura 1 se observan las contribuciones de cada una de las facetas del perfeccionismo sobre las distintas dimensiones del estrés escolar: el perfeccionismo autorientado contribuyó de manera estadísticamente significativa al estrés emocional y a la tensión interpersonal; el perfeccionismo socialmente prescrito contribuyó de manera estadísticamente significativa a las tres dimensiones del estrés escolar; y el perfeccionismo orientado a otros únicamente predijo la tensión interpersonal.

Figura 1: Modelo de regresión multivariada entre las dimensiones del perfeccionismo y las del estrés escolar

Nota: La línea discontinua representa una relación no significativa (p > .05).

Discusión

Esta investigación tuvo como fin analizar el rol predictor del perfeccionismo disfuncional infantil en el estrés escolar, así como valorar las contribuciones diferenciales de cada una de las dimensiones del perfeccionismo, a partir de una muestra de estudiantes de sexto y séptimo grado de la ciudad de Posadas (Argentina).

En el análisis descriptivo se hallaron valores que pueden considerarse esperables dada la naturaleza de las variables. En lo que refiere al perfeccionismo intrapersonal, el baremo disponible para población argentina (Oros & Vargas Rubilar, 2016) indica que valores cercanos a 30-31 puntos representan un nivel moderado de perfeccionismo. No se halló hasta el momento una escala que permita interpretar los datos obtenidos en las dimensiones interpersonales del perfeccionismo, aunque el contraste con los valores mínimos y máximos sugiere que los promedios obtenidos representan niveles bajos de los atributos en la muestra de estudio. De igual manera, los valores promedios de estrés escolar y de cada una de sus dimensiones pueden considerarse moderados a bajos, de acuerdo con los mínimos y máximos posibles.

En el análisis de correlaciones, si bien se encontró que las tres facetas del perfeccionismo se asocian de manera estadísticamente significativa y positiva con el estrés escolar, las correlaciones de gran tamaño se dieron con las dimensiones autorientada y socialmente prescrita. En coincidencia con estos hallazgos, Aguilar Durán (2019) encontró que el perfeccionismo autorientado se asocia a mayores niveles de estrés en estudiantes de nivel primario de Caracas. De la misma forma, Molnar et al. (2012) obtuvieron evidencias de que el perfeccionismo autorientado y el socialmente prescrito se encontraban más asociados al empeoramiento de la salud física, producto del estrés percibido, en una muestra de estudiantes universitarios. En cuanto al perfeccionismo orientado a otros y su relación con el estrés, la literatura científica es exigua, por lo que las evidencias que aporta este trabajo son novedosas y deberían ser puestas a prueba en nuevos estudios.

Puede argüirse, en síntesis, que resulta esperable que las dimensiones autorientada y socialmente prescrita sean las más involucradas en el estrés escolar, teniendo en cuenta que ambas dan lugar a una considerable autodemanda en los estudiantes perfeccionistas, ya sea que provenga de sí mismo o de los demás. Siguiendo esta línea, los niños y niñas perfeccionistas podrían sentirse sobrepasados y sin recursos para hacer frente a las demandas escolares (Richard, 2022).

En lo que refiere a las subdimensiones del estrés escolar, los tres tipos de perfeccionismo se asociaron con el estrés emocional, lo que indica que los estudiantes perfeccionistas tienden a percibir falta de interés, agotamiento y desmotivación en relación con la escuela, los maestros y el propio desempeño. Del mismo modo, un estudio realizado con estudiantes de escuelas medias y secundarias de China reportó que el grupo de perfeccionistas desadaptativos (i. e., elevados estándares y elevada discrepancia) percibía que su nivel académico era más bajo, sentía menor satisfacción y mayor estrés en relación con el aprendizaje (Yang et al., 2016). Así también, las tres facetas del perfeccionismo se relacionaron con el factor de tensión interpersonal: esto sugiere que el perfeccionismo desadaptativo infantil se asocia a mayores experiencias negativas en los vínculos con los pares, lo que genera tensión, ansiedad y/o victimización. Estos resultados son congruentes con el modelo de desconexión social y aportan nuevas evidencias de su validez para comprender la vida social de niños y niñas perfeccionistas (Chemisquy, 2021; Goya Arce & Polo, 2017).

Por último, solo el perfeccionismo socialmente prescrito obtuvo una asociación estadísticamente significativa con el estrés en relación con el autoconcepto. En este sentido, niños y niñas con elevados niveles de esta faceta pueden presentar una autoestima disminuida y experimentar dificultades en la adaptación escolar. Estos resultados coinciden parcialmente con la investigación de Teixeira et al. (2016) realizada con mujeres adolescentes de Portugal, en la que el perfeccionismo autorientado obtuvo una relación no significativa con la autoestima, mientras que el socialmente prescrito correlacionó de forma negativa con esta variable.

En el estudio de regresión lineal múltiple se encontró que el perfeccionismo desadaptativo predice el estrés escolar de los estudiantes de nivel primario. Este resultado es acorde al modelo de generación de estrés, que propone que la relación entre perfeccionismo y estrés contribuye al desarrollo y/o mantenimiento de diversos procesos psicopatológicos (Hewitt & Flett, 2002).

En lo que refiere al rol del perfeccionismo autorientado en la predicción del estrés escolar, la hipótesis de la vulnerabilidad específica al estrés indica que esta dimensión intrapersonal sería la más reactiva a los estresores ligados a los logros (Hewitt & Flett, 1993). En esta línea, algunos autores plantean que este tipo de perfeccionismo puede resultar adaptativo mientras los niveles de estrés a los que se vea sometida la persona resulten manejables (Gaudreau et al., 2018). En relación con esto, parece comprensible que esta faceta del perfeccionismo contribuya al estrés escolar, ya que la escuela es un ambiente en el que los logros, el desempeño, y en ocasiones la competencia, tienen un rol central. Esto puede fomentar en los estudiantes la activación de las creencias desadaptativas ―los must, en palabras de Ellis (2002)―, las conductas de comprobación, la procrastinación y las reacciones negativas ante el fracaso, describiendo el círculo vicioso que señala Oros (2005).

Por otra parte, el rol del perfeccionismo socialmente prescrito en la predicción del estrés es acorde a la evidencia científica: numerosos estudios previos, sintetizados en la revisión de Flett et al. (2022), indican que esta faceta es la menos saludable del constructo. En este sentido, por ejemplo, Chang y Rand (2000) encontraron que los universitarios con elevado nivel de perfeccionismo socialmente prescrito, que, a su vez, están expuestos a elevados niveles de estrés, pueden resultar más proclives al desarrollo de diversos síntomas psicológicos y desesperanza. En una línea similar, Díez et al. (2023) hallaron que las expectativas parentales predicen el estrés por el desempeño escolar, por la incertidumbre y por el conflicto escuela-ocio.

Por último, en este trabajo se encontró que la dimensión orientada a otros no contribuyó al estrés escolar de niños y niñas. Como se mencionó previamente, esta faceta del perfeccionismo es la menos estudiada en población infantil, aunque las evidencias indican que está más relacionada con rasgos del tipo narcisista que con salidas negativas (i. e., desconexión social) (Hewitt et al., 2022), e incluso puede cumplir un rol de amortiguador frente a dichas salidas al aumentar la autoestima y permitir la externalización de la culpa (Chen et al., 2017). De acuerdo con estas premisas, es posible que los niños y niñas con un elevado perfeccionismo orientado a los otros hagan responsables a los demás de algunas dificultades que experimentan en la escuela y terminen, en consecuencia, experimentando menor malestar en ese ámbito.

En la regresión multivariada se encontró que el perfeccionismo autorientado contribuye al estrés emocional y a la tensión interpersonal. En este sentido, la revisión de la literatura científica indica que los estudiantes perfeccionistas tienden a percibir una elevada discrepancia entre las metas que se imponen y sus logros, a desconfiar de sus capacidades, a temer al fracaso y a obtener una escasa satisfacción con sus logros (Accordino et al., 2000; Bong et al., 2014; Lozano et al., 2014; Nounopoulos et al., 2006; Stoeber & Rambow, 2007); todo esto podría promover la aparición de sentimientos de agotamiento y desmotivación en relación con la escuela. El estrés emocional también puede emerger asociado con la ansiedad frente a tareas nuevas y con la evaluación negativa del propio desempeño que caracteriza a estos niños y niñas, que podrían dar lugar a sentimientos de insatisfacción respecto de la vida académica (DiBartolo & Varner, 2012; Schruder et al., 2014). Además, los altos estándares se asocian con un aumento de la angustia de los estudiantes (Wuthrich et al., 2020) y con emociones negativas tales como ira, ansiedad y culpa (Curelaru et al., 2017) que podrían contribuir a la aparición de las manifestaciones del estrés emocional en la escuela.

La faceta autorientada también contribuyó a la tensión interpersonal en la escuela, resultado acorde al modelo de desconexión social de los perfeccionistas (Hewitt et al., 2006). Estudios previos indican que el perfeccionismo intrapersonal puede deteriorar la vida social de los niños y niñas (Chemisquy & Oros, 2020), lo que se explicaría en parte por su tendencia a la competitividad y a sus esfuerzos por destacar. En este sentido, por ejemplo, se halló que los perfeccionistas autorientados pueden resultar más antisociales y menos prosociales con sus pares y oponentes cuando realizan deportes (Mallinson-Howard et al., 2019). Por otra parte, los estudiantes perfeccionistas suelen evitar actividades en las que se consideran en desventaja (Flett & Hewitt, 2013), quedando aislados y al margen de algunas interacciones sociales en las que sus pares se involucran gustosos.

En lo que refiere al perfeccionismo socialmente prescrito, en el análisis de path se verificó que contribuye en las tres dimensiones del estrés escolar evaluadas. Como se mencionó, esta faceta interpersonal suele ser considerada la más desadaptativa, ya que suele relacionarse con diversas salidas psicopatológicas, con lo que resulta esperable que sea la más involucrada en el estrés de los estudiantes en relación con la escuela.

En la literatura científica aún no se encuentra una descripción unívoca de la vivencia emocional de los perfeccionistas socialmente prescritos en la escuela. Por ejemplo, mientras que en una investigación se encontró que el perfeccionismo socialmente prescrito solo resultó predictor de la desesperanza (y no de la ansiedad, ira ni culpa) (Curelaru et al., 2017), en otro estudio se halló que los estudiantes con un elevado nivel de perfeccionismo socialmente prescrito tienden a experimentar mayor afectividad negativa y positiva que los estudiantes con un bajo nivel de este atributo (Vicent et al., 2017). Los resultados obtenidos en el presente trabajo sugieren que los estudiantes con un elevado perfeccionismo socialmente prescrito, al igual que los autorientados, vivencian la escuela como un ámbito de insatisfacción y desmotivación. En esta misma línea, se encontraron evidencias que sugieren que los perfeccionistas socialmente prescritos perciben ineficacia (Çelik et al., 2014) e inferioridad en el ámbito escolar (Lee et al., 2020), lo que podría colaborar a explicar la insatisfacción de estos niños y niñas en la escuela.

Asimismo, el perfeccionismo socialmente prescrito también se relacionó con estrés escolar por la tensión interpersonal. De acuerdo con el modelo de desconexión social, el perfeccionismo impacta de forma negativa en la vida interpersonal, lo que, a su vez, lleva a otros problemas de salud psicoemocional. En este sentido, los perfeccionistas socialmente prescritos pueden sentir desesperanza social (Roxborough et al., 2012), sensibilidad al rechazo, aislamiento social (Magson et al., 2019) y estas dificultades vinculares pueden ser percibidas como generadoras de estrés académico. Una investigación realizada por Gonzálvez et al. (2015) halló que este tipo de perfeccionistas puede avanzar hasta el rechazo escolar con el fin de escapar de la aversión social y de otras situaciones estresantes, tales como el temor a la evaluación o la necesidad de captar la atención de los seres queridos.

Como ya se mencionó, la dimensión socialmente prescrita fue la única que obtuvo una asociación estadísticamente significativa y predijo el estrés escolar relacionado con el autoconcepto. Este resultado es congruente con las evidencias científicas que indican que esta faceta suele asociarse a baja autoestima (Cha, 2016) y a la percepción de ineficacia e inferioridad académica (Çelik et al., 2014; Lee et al., 2020). En síntesis, estos hallazgos dan cuenta de la autovaloración negativa de sí mismos, una característica de estos estudiantes, que, a su vez, puede aumentar el malestar en el ámbito escolar.

Finalmente, el perfeccionismo orientado a otros predijo únicamente el estrés escolar por tensión interpersonal. Como ya se mencionó, es posible que este tipo de perfeccionista logre evitar el estrés escolar debido a su tendencia a culpar a los demás (Chen et al., 2017). Empero, en lo tocante a la vida social, los perfeccionistas orientados a otros han mostrado ser menos amables y, contrariamente, más hostiles y dominantes (Smith et al., 2022), lo que podría conducir a conflictos interpersonales que aumentan el malestar en la escuela. Si bien aún es poco lo que se conoce respecto de esta faceta del perfeccionismo en población infantil, los resultados de este estudio están en línea con los obtenidos por Sherry et al. (2016), que sugieren estudiar sus consecuencias interpersonales en el marco del modelo de desconexión social de los perfeccionistas.

Limitaciones y futuras líneas

Algunas limitaciones del presente estudio están relacionadas con el tipo de muestreo que impide la generalización de los resultados. En este sentido, se identificaron limitaciones asociadas a las características de la muestra, como la distribución desigual de factores sociodemográficos con relación al sexo y la gestión escolar. Esto puede provocar posibles sesgos en los resultados obtenidos. Asimismo, el diseño transversal puede representar una limitación al no contar con información recolectada en más de un tiempo.

Por otra parte, si bien el estudio del perfeccionismo infantil es amplio y variado, aún se desconocen muchos aspectos de su dinámica en la escuela. Los diseños longitudinales pueden ser de gran utilidad para identificar el impacto del perfeccionismo a través del tiempo; así también pueden resultar relevantes los estudios de corte cualitativo, en los que se profundice en la vivencia subjetiva de niños y niñas.

Referencias:

Accordino, D. B., Accordino, M. P., & Slaney, R. B. (2000). An investigation of perfectionism, mental health, achievement, and achievement motivation in adolescents. Psychology in the Schools, 37(6). 535-545. https://doi.org/10.1002/1520-6807(200011)37:6%3C535::AID-PITS6%3E3.0.CO;2-O

Aguilar Durán, L. A. (2019). Perfeccionismo en escolares de Caracas: diferencias en función del sexo, tipo de institución educativa y nivel de estrés. Revista de Psicología Universidad de Antioquia, 11(1), 7-33. https://doi.org/10.17533/udea.rp.v11n1a01

Asseraf, M., & Vaillancourt, T. (2015). Longitudinal links between perfectionism and depression in children. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 43(5), 895-908. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-014-9947-9

Barba, M. J. (2019). Evidencias de validez y confiabilidad de la escala de perfeccionismo infantil en niños del distrito de Chepén. Revista JANG, 8(2), 178-192. https://doi.org/10.18050/jang.v8i2.2252

Bills, E., Greene, D., Stackpole, R., & Egan, S. J. (2023). Perfectionism and eating disorders in children and adolescents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Appetite, 187, 106586. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appet.2023.106586

Bong, M., Hwang, A., Noh, A., & Kim, S. (2014). Perfectionism and motivation of adolescents in academic contexts. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106(3), 711-729. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0035836

Bringhenti, F. (1996). Lo stress scolástico e la sua valutazione. Psicologia e Scuola, 81, 3-13.

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guildford Press.

Çelik, E., Arıcı Özcan, N., & Turan, M. E. (2014). The perception of school inefficacy, social prescribed perfectionism and self-appraisal as predictors of adolescents' life satisfaction. Eğitimde Kuram ve Uygulama / Journal of Theory and Practice in Education, 10(4), 1143-1155.

Cha, M. (2016). The mediation effect of mattering and self-esteem in the relationship between socially prescribed perfectionism and depression: Based on the social disconnection model. Personality and Individual Differences, 88, 148-159. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.09.008

Chang, E. C., & Rand, K. L. (2000). Perfectionism as a predictor of subsequent adjustment: Evidence for a specific diathesis-stress mechanism among college students. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 47(1), 129-137. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0167.47.1.129

Chemisquy, S. (2021). Perfeccionismo, apoyo social percibido, soledad y depresión. Avances sobre el modelo de desconexión social en niños (Tesis doctoral). Universidad Nacional de Córdoba.

Chemisquy, S., & Oros, L. B. (2020). El perfeccionismo desadaptativo como predictor de la soledad y del escaso apoyo social percibido en niños y niñas argentinos. Revista Colombiana de Psicología, 29(2), 105-123. https://doi.org/10.15446/rcp.v29n2.78591

Chemisquy, S., Oros, L. B., Serppe, M., & Ernst, C. (2019). Caracterización del perfeccionismo disfuncional en la niñez tardía. Apuntes Universitarios, 9(2), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.17162/au.v9i2.355

Chen, C., Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (2017). Ethnic variations in other-oriented perfectionism’s associations with depression and suicide behaviour. Personality and Individual Differences, 104, 504-509. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.09.021

Cichosz, P. (2015). Data Mining Algorithms: Explained Using R. John Wiley & Sons.

Cohen, J. (1992). Statistical power analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 1(3). https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep10768783

Cupani, M. (2012). Análisis de Ecuaciones Estructurales: conceptos, etapas de desarrollo y un ejemplo de aplicación. Revista Tesis, 2, 186-199.

Curelaru, V., Diac, G., & Hendreș, D. M. (2017). Perfectionism in high school students, academic emotions, real and perceived academic achievement. En E. Soare, & C. Langa (Eds.), Education Facing Contemporary World Issues (pp. 1170-1178). https://doi.org/10.15405/epsbs.2017.05.02.144

DiBartolo, P. M., & Varner, S. P. (2012). How children's cognitive and affective responses to a novel task relate to the dimensions of perfectionism. Journal of Rational-Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 30, 62-72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10942-011-0130-8

Díez, M., Jiménez-Iglesias, A., Paniagua, C., & García-Moya, I. (2023). The role of perfectionism and parental expectations in the school stress and health complaints of secondary school students. Youth & Society, 56(6), 885-906. https://doi.org/10.1177/0044118X231205929

Ellis, A. (2002). The role of irrational beliefs in perfectionism. En G. L. Flett, & P. L. Hewitt (Eds.), Perfectionism: Theory, research, and treatment (pp. 217-229). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10458-009

Ferrer, L., Martín-Vivar, M., Pineda, D., Sandín, B., & Piqueras, J. A. (2018). Relación de la ansiedad y la depresión en adolescentes con dos mecanismos transdiagnósticos: el perfeccionismo y la rumiación. Psicología Conductual, 26(1), 55-74. https://www.behavioralpsycho.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/09/03.-Ferrer-261-1.pdf

Flett, G. L., & Hewitt, P. L. (2013). Disguised distress in children and adolescents “Flying under the radar”: Why psychological problems are underestimated and how schools must respond. Canadian Journal of School Psychology, 28(1), 12-27. https://doi.org/10.1177/0829573512468845

Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., Besser, A., Su, C., Vaillancourt, T., Boucher, D., Munro, Y., Davidson, L. A., & Gale, O. (2016). The Child-Adolescent Perfectionism Scale: Development, psychometric properties, and associations with stress, distress, and psychiatric symptoms. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 34(7), 634-652. https://doi.org/10.1177/0734282916651381

Flett, G. L., Hewitt, P. L., Nepon, T., Sherry, S. B., & Smith, M. (2022). The destructiveness and public health significance of socially prescribed perfectionism: A review, analysis, and conceptual extension. Clinical Psychology Review, 93, 102130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cpr.2022.102130

Flett, G. L., Nepon, T., Hewitt, P. L., & Fitzgerald, K. (2016). Perfectionism, components of stress reactivity, and depressive symptoms. Journal of Psychopathology and Behavioral Assessment, 38(4), 645-654. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10862-016-9554-x

Ford, C. J., Usher, E. L., Scott, V. L., & Chen, X. Y. (2023). The ‘perfect’ lens: Perfectionism and early adolescents' math self‐efficacy development. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(1), 211-228. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12550

Funder, D. C., & Ozer, D. J. (2019). Evaluating effect size in psychological research: Sense and nonsense. Advances in Methods and Practices in Psychological Science, 2(2), 156-168. https://doi.org/10.1177/2515245919847202

Gallucci, M. (2021). PATHj: jamovi Path Analysis (versión 2.3) (Software). Windows. https://pathj.github.io/help.html

Gaudreau, P., Franche, V., Kljajic, K., & Martinelli, G. (2018). The 2 x 2 model of perfectionism: Assumptions, trends, and potential developments. En J. Stoeber (Ed.), The psychology of perfectionism. Theory, research, applications (pp. 44-67). Routledge/Taylor & Francis Group.

George, D., & Mallery, P. (2011). IBM SPSS Statistics 19. Step by step: A simple guide and reference. Pearson Higher Education.

Gil, T. C., Obando, D., García-Martín, M. B., & Sandoval-Reyes, J. (2023). Perfectionism, academic stress, rumination and worry: A predictive model for anxiety and depressive symptoms in university students from Colombia. Emerging Adulthood, 11(5), 1091-1105. https://doi.org/10.1177/21676968231188759

Gonzálvez, C., Vicent, M., Inglés, C. J., Lagos-San Martín, N., García-Fernández, J. M., & Martínez-Monteagudo, M. C. (2015). Diferencias en el perfeccionismo socialmente prescrito en función del rechazo escolar. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, 1(1), 455-462. https://doi.org/10.17060/ijodaep.2015.n1.v1.47

Goya Arce, A. B., & Polo, A. J. (2017). A test of the perfectionism social disconnection model among ethnic minority youth. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 45(6), 1181-1193. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10802-016-0240-y

Gyori, D., & Balazs, J. (2021). Nonsuicidal self-injury and perfectionism: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychiatry, (12), 691147. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.691147

Harvey, B. C., Moore, A. M., & Koestner, R. (2017). Distinguishing self-oriented perfectionism-striving and self-oriented perfectionism-critical in school-aged children: Divergent patterns of perceived parenting, personal affect and school performance. Personality and Individual Differences, 113, 136-141. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.02.069

Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (1991). Perfectionism in the self and social contexts: Conceptualization, assessment, and association with psychopathology. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 60(3), 456-470. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.60.3.456

Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (1993). Dimensions of perfectionism, daily stress, and depression: A test of the specific vulnerability hypothesis. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 102(1), 58-65. https://doi.org/10.1037/0021-843X.102.1.58

Hewitt, P. L., & Flett, G. L. (2002). Perfectionism and stress processes in psychopathology. En P. L. Hewitt, & G. L. Flett (Eds.), Perfectionism: Theory, research, and treatment (pp. 255-284). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10458-011

Hewitt, P. L., Flett, G. L., Sherry, S. B., & Caelian, C. M. (2006). Trait perfectionism dimensions and suicide behavior. En T. E. Ellis (Ed.), Cognition and suicide. Theory, research and therapy (pp. 215-235). American Psychological Association. https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2006-01745-010

Hewitt, P. L., Smith, M. M., Flett, G. L., Ko, A., Kerns, C., Birch, S., & Peracha, H. (2022). Other-oriented perfectionism in children and adolescents: Development and validation of the Other-Oriented Perfectionism Subscale-junior form (OOPjr). Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 40(3), 327-345. https://doi.org/10.1177/07342829211062009

Hooper, D., Coughlan, J., & Mullen, M. R. (2008). Structural equation modeling: Guidelines for determining model fit. Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 6(1), 53-60.

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 6(1), 1-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Inglés, C. J., García-Fernández, J. M., Vicent, M., Gonzálvez, C., & Sanmartín, R. (2016). Profiles of perfectionism and school anxiety: A review of the 2 × 2 model of dispositional perfectionism in child population. Frontiers in Psychology, 7, 1403. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01403

Kenny, D. A., Kaniskan, B., & McCoach, D. B. (2014). The performance of RMSEA in models with small degrees of freedom. Sociological Methods & Research, 44(3), 486-507. https://doi.org/10.1177/0049124114543236

Lee, Y., Ha, J. H., & Jue, J. (2020). Structural equation modeling and the effect of perceived academic inferiority, socially prescribed perfectionism, and parents’ forced social comparison on adolescents’ depression and aggression. Children and Youth Services Review, 108, 104649. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.childyouth.2019.104649

Lozano, L., Valor-Segura, I., Llanos, A., & Lozano, L. (2014). Efectos del perfeccionismo infantil sobre la inteligencia y el rendimiento académico. En A. Romero, T. Ramiro-Sánchez, & M. Paz (Coords.), Libro de actas del II Congreso Internacional de Ciencias de la Educación y del Desarrollo (p. 178). Asociación Española de Psicología Conductual.

Magson, N. R., Oar, E. L., Fardouly, J., Johnco, C. J., & Rapee, R. M. (2019). The preteen perfectionist: An evaluation of the perfectionism social disconnection model. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 50, 960-974. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-019-00897-2

Mallinson-Howard, S. H., Hill, A. P., & Hall, H. K. (2019). The 2 × 2 model of perfectionism and negative experiences in youth sport. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 45, 101581. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2019.101581

Martínez Díaz, E. S., & Díaz Gómez, D. A. (2007). Una aproximación psicosocial al estrés escolar. Educación y Educadores, 10(2), 11-22. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/834/83410203.pdf

Molnar, D. S., Sadava, S. W., Flett, G. L., & Colautti, J. (2012). Perfectionism and health: A mediational analysis of the roles of stress, social support and health-related behaviors. Psychology & Health, 27(7), 846-864. https://doi.org/10.1080/08870446.2011.630466

Nounopoulos, A., Ashby, J. S., & Gilman, R. (2006). Coping resources, perfectionism, and academic performance among adolescents. Psychology in the Schools, 43(5), 613-622. https://doi.org/10.1002/pits.20167

Oros, L. B. (2003). Medición del perfeccionismo infantil: desarrollo y validación de una escala para niños de 8 a 13 años de edad. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación Psicológica. 16(2), 99-112. https://www.aidep.org/03_ridep/R16/R166.pdf

Oros, L. B. (2005). Implicaciones del perfeccionismo infantil sobre el bienestar psicológico: orientaciones para el diagnóstico y la práctica clínica. Anales de Psicología, 21(2), 294-303. https://revistas.um.es/analesps/article/view/26951

Oros, L. B., Chemisquy, S. N., Serppe, M. D., & Helguera, G. P. (2023). Validación del modelo multidimensional de perfeccionismo en población infantil. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 21(2), 1-25. https://doi.org/10.11600/rlcsnj.21.2.5532

Oros, L., Serppe, M. D., Chemisquy, S. N., & Ventura-León, J. L. (2019). Construction of a scale to assess maladaptive perfectionism in children in its social dimension. Revista Argentina de Clínica Psicológica, 28(4), 385-398. https://doi.org/10.24205/03276716.2019.1108

Oros, L. B., & Vargas-Rubilar, J. (2016). Perfeccionismo infantil: normalización de una escala argentina para su evaluación. Acción Psicológica, 13(2), 117-126. https://doi.org/10.5944/ap.13.2.17822

Richard, M. A. (2022). Perfeccionismo y estrés académico en estudiantes universitarios de la ciudad de Paraná (Trabajo integrador final, Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina). Repositorio Institucional UCA. https://repositorio.uca.edu.ar/handle/123456789/17596

Rodríguez Ayán, N. R., & Ruiz Díaz, M. Á. (2008). Atenuación de la asimetría y de la curtosis de las puntuaciones observadas mediante transformaciones de variables: Incidencia sobre la estructura factorial. Psicológica, 29(2), 205-227.

Rosseel, Y. (2011). lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2), 1-36. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Roxborough, H. M., Hewitt, P. L., Kaldas, J., Flett, G. L., Caelian, C. M., Sherry, S., & Sherry, D. L. (2012). Perfectionistic self‐presentation, socially prescribed perfectionism, and suicide in youth: A test of the perfectionism social disconnection model. Suicide and Life‐Threatening Behavior, 42(2), 217-233. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1943-278X.2012.00084.x

Sánchez-Rodríguez, E., Ferreira-Valente, A., Pathak, A., Solé, E., Sharma, S., Jensen, M. P., & Miró, J. (2021). The role of perfectionistic self-presentation in pediatric pain. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(2), 591. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18020591

Schruder, C. R., Curwen, T., & Sharpe, G. W. B. (2014). Perfectionistic students: Contributing factors, impacts, and teacher strategies. British Journal of Education, Society & Behavioural Science, 4(2), 139-155. https://doi.org/10.9734/BJESBS/2014/5532

Seong, H., Lee, S., & Chang, E. (2021). Perfectionism and academic burnout: Longitudinal extension of the bifactor model of perfectionism. Personality and Individual Differences, 172, 110589. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110589

Sherry, S. B., Mackinnon, S. P., & Gautreau, C. M. (2016). Perfectionists do not play nicely with others: Expanding the social disconnection model. En F. M. Sirois & D. S. Molnar (Eds.), Perfectionism, health, and well-being (pp. 225-243). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-18582-8_10

Smith, M. M., Sherry, S. B., Ge, S. Y., Hewitt, P. L., Flett, G. L., & Baggley, D. L. (2022). Multidimensional perfectionism turns 30: A review of known knowns and known unknowns. Canadian Psychology/Psychologie canadienne, 63(1), 16-31. https://doi.org/10.1037/cap0000288

Stoeber, J., & Rambow, A. (2007). Perfectionism in adolescents school students. Relations with motivation, achievement, and well-being. Personality and Individual Differences, 42(7), 1379-1389. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2006.10.015

Tabachnick, B. G. & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using Multivariate Statistics (6ª ed.). Pearson.

Teixeira, M. D., Pereira, A. T., Marques, M. V., Saraiva, J. M., & Macedo, A. F. D. (2016). Eating behaviors, body image, perfectionism, and self-esteem in a sample of Portuguese girls. Brazilian Journal of Psychiatry, 38(2), 135-140. https://doi.org/10.1590/1516-4446-2015-1723

Vicent, M., Inglés, C. J., Sanmartín, R., Gonzálvez, C., & García-Fernández, J. M. (2017). Perfectionism and aggression: identifying risk profiles in children. Personality and Individual Differences, 112, 106-112. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2017.02.061

Vicent, M., Inglés, C. J., Sanmartín, R., Gonzálvez, C., Granados Alos, L., & García-Fernández, J. M. (2017). Socially prescribed perfectionism and affectivity in Spanish child population. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 7(1), 17-29. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe7010002

West, S. G., Taylor, A. B., & Wu, W. (2012). Model fit and model selection in structural equation modeling. En R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Handbook of structural equation modeling (pp. 209-231). The Guilford Press.

Wuthrich, V. M., Jagiello, T., & Azzi, V. (2020). Academic stress in the final years of school: A systematic literature review. Child Psychiatry & Human Development, 51(6), 986-1015. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10578-020-00981-y

Yang, H., & Chen, J. (2015). Learning perfectionism and learning burnout in a primary school student sample: A test of a learning-stress mediation model. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25, 345-353. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-015-0213-8

Yang, H., Guo, W., Yu, S., Chen, L., Zhang, H., Pan, L., Wang, C., & Chang, E. C. (2016). Personal and family perfectionism in Chinese school students: Relationships with learning stress, learning satisfaction and self-reported academic performance level. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 25(12), 3675-3683. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0524-4

Disponibilidad de datos: El conjunto de datos que apoya los resultados de este estudio no se encuentra disponible.

Cómo citar: Chemisquy, S. N., Arévalo, L. N., & Penz Picaza, M., M. (2024). Relaciones entre perfeccionismo disfuncional y estrés escolar en estudiantes de nivel primario de Posadas (Argentina). Ciencias Psicológicas, 18(2), e-3967. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v18i2.3967

Contribución de los autores (Taxonomía CRediT): 1. Conceptualización; 2. Curación de datos; 3. Análisis formal; 4. Adquisición de fondos; 5. Investigación; 6. Metodología; 7. Administración de proyecto; 8. Recursos; 9. Software; 10. Supervisión; 11. Validación; 12. Visualización; 13. Redacción: borrador original; 14. Redacción: revisión y edición.

S. N. C. ha contribuido en 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14; L. N. A. en 2, 3, 5, 12, 13, 14; y M. M. P. P. en 2, 8, 13, 14.

Editora científica responsable: Dra. Cecilia Cracco.

10.22235/cp.v18i2.3967

Original Articles

Relationships between dysfunctional perfectionism and school stress in primary school students in Posadas (Argentina)

Relaciones entre perfeccionismo disfuncional y estrés escolar en estudiantes de nivel primario de Posadas (Argentina)

Relações entre perfeccionismo disfuncional e estresse escolar em estudantes do nível primário de Posadas (Argentina)

Sonia Noemí Chemisquy1, ORCID 0000-0002-3820-3036

Luana Natahela Arévalo2, ORCID 0000-0002-6926-8086

Milagros Mercedes Penz Picaza3, ORCID 0009-0007-7978-8097

1 Universidad Católica de las Misiones, Argentina, [email protected]

2 Universidad Católica de las Misiones, Argentina

3 Universidad Católica de las Misiones, Argentina

Abstract:

Although it is known that maladaptive perfectionism leads to negative consequences in academic life, so far, no scientific work has been found that studies school stress in relation to the three dimensions of multidimensional perfectionism (i. e., self-directed, socially prescribed, and other-oriented). The aim of this paper was to analyze the predictive role of dysfunctional perfectionism in school stress in primary school students and to assess the differential contribution of each of its dimensions. A quantitative, cross-sectional, and correlational study was conducted with n = 226 students from primary schools in the city of Posadas, Argentina. The results suggest that perfectionism predicts school stress by 31.9 %, especially in the self-directed and socially prescribed dimensions. In multivariate regression analysis, self-oriented perfectionism contributed to emotional stress and interpersonal tension, socially prescribed perfectionism predicted all three dimensions of school stress, while other-oriented perfectionism only predicted interpersonal tension. These results are in line with the underlying theoretical model and provide relevant information to deepen the understanding of the dynamics of children's perfectionism at the primary school level.

Keywords: perfectionism; school stress; primary education; middle childhood.

Resumen:

Aunque es conocido que el perfeccionismo desadaptativo tiene consecuencias negativas en la vida académica, hasta el momento no se hallaron trabajos científicos que estudien el estrés escolar en relación con las tres dimensiones del perfeccionismo multidimensional (i. e., autorientado, socialmente prescrito y orientado a otros). El objetivo de este trabajo fue analizar el rol predictor del perfeccionismo disfuncional en el estrés escolar de estudiantes de nivel primario y valorar la contribución diferencial de cada una de sus dimensiones. Se realizó un estudio cuantitativo, transversal y correlacional con n = 226 estudiantes de escuelas primarias de la ciudad de Posadas, Argentina. Los resultados sugieren que el perfeccionismo predice el estrés escolar en un 31.9 %, sobre todo en las dimensiones autorientada y socialmente prescrita. En el análisis de regresión multivariada, el perfeccionismo autorientado contribuyó al estrés emocional y a la tensión interpersonal, el perfeccionismo socialmente prescrito predijo las tres dimensiones del estrés escolar, mientras que el perfeccionismo orientado a otros solo predijo la tensión interpersonal. Estos resultados son acordes al modelo teórico de base y aportan información relevante para profundizar el conocimiento de la dinámica del perfeccionismo infantil en el nivel primario de la escuela.

Palabras clave: perfeccionismo; estrés académico; educación primaria; tercera infancia.

Resumo:

Embora se saiba que o perfeccionismo desadaptativo conduz a consequências negativas na vida acadêmica, até o momento, não foram encontrados trabalhos científicos que estudem o estresse escolar em relação às três dimensões do perfeccionismo multidimensional (i. e., auto-orientado, socialmente prescrito e orientado para os outros). O objetivo deste trabalho foi analisar o papel preditivo do perfeccionismo disfuncional no estresse escolar de estudante do nível primário e avaliar a contribuição diferencial de cada uma de suas dimensões. Foi realizado um estudo quantitativo, transversal e correlacional com n = 226 estudantes de escolas primárias da cidade de Posadas, Argentina. Os resultados sugerem que o perfeccionismo prediz o estresse escolar em 31,9 %, especialmente nas dimensões auto- orientada e socialmente prescrita. Na análise de regressão multivariada, o perfeccionismo auto-orientado contribuiu para o estresse emocional e para a tensão interpessoal; o perfeccionismo socialmente prescrito prediz as três dimensões do estresse escolar, enquanto o perfeccionismo orientado para os outros apenas prediz a tensão interpessoal. Estes resultados estão de acordo com o modelo teórico de base e fornecem informações relevantes para aprofundar o conhecimento da dinâmica do perfeccionismo infantil no nível primário escolar.

Palavras-chave: perfeccionismo; estresse acadêmico; educação primária; terceira infância.

Received: 13/11/2024

Accepted: 21/03/2024

The term “perfectionism” was defined by Hewitt and Flett (1991) as the tendency to set and pursue high, though often unrealistic, standards. According to these authors, the rigid need for perfection and the concern with being perfect—or appearing perfect—can arise from a number of underlying issues and serve different functions, resulting in three distinct dimensions: (a) self-oriented perfectionism, driven by personal expectations of oneself; (b) socially prescribed perfectionism, which involves the belief that others expect perfection from us; and (c) other-oriented perfectionism, where individuals hold high expectations of others (Smith et al., 2022).

Numerous scientific studies have explored the consequences of maladaptive perfectionism during childhood, with evidence showing that it can lead to different issues across different areas of child development. For instance, certain aspects of interpersonal perfectionism (i. e., perfectionistic self-presentation) in childhood have been associated with physical discomfort (Sánchez & Rodríguez et al., 2021). Moreover, within child and adolescent populations, perfectionism has been linked to depression (Asseraf & Vaillancourt, 2015), anxiety (Ferrer et al., 2018), eating disorders (Bills et al., 2023), self-harm (Gyori & Balazs, 2021), and other mental health issues. Evidence also suggests that perfectionism increases children’s vulnerability, acting as a risk factor that may predispose them to more serious issues. In this context, research indicates that certain aspects of maladaptive childhood perfectionism—specifically a combined profile of self-oriented and socially prescribed perfectionism—are associated with heightened levels of hostility, verbal and physical aggression, and anger (Vicent, Inglés, Sanmartín, Gonzálvez, & García-Fernández, 2017). Furthermore, high levels of socially prescribed perfectionism have been linked to negative emotional states and pathological thoughts (Gonzálvez et al., 2015). Particularly in the interpersonal domain, findings reveal that all three dimensions of perfectionism increase feelings of loneliness and reduce perceptions of social support in children (Chemisquy & Oros, 2020).

In this regard, one model that seeks to explain the maladaptive effects of perfectionism is the stress-vulnerability model (Hewitt & Flett, 1993; 2002), which suggests that perfectionism can influence or interact with stress, leading to or maintaining psychopathological states. This may occur because perfectionists either experience higher levels of stress or respond to stress in maladaptive ways. Evidence supports this model, for instance, the self-oriented and socially prescribed dimensions of perfectionism have been linked to poorer physical health due to perceived stress (Molnar et al., 2012). Additionally, research suggests that the connection between socially prescribed perfectionism and depression may arise from an intensified stress reactivity (Flett, Nepon et al., 2016).

Interestingly, within the school context, self-oriented perfectionism has been found to positively impact academic performance (Harvey et al., 2017) and math self-efficacy (Ford et al., 2023). Conversely, evidence indicates that perfectionistic children tend to experience higher levels of school-related anxiety compared to their non-perfectionistic peers (Inglés et al., 2016). Additionally, those with elevated levels of socially prescribed perfectionism may face greater peer rejection at school (Gonzálvez et al., 2015). Research also suggests that certain facets of perfectionism can contribute to higher stress within the school and learning environment (Yang & Chen, 2015).

School-related stress has been defined by Martínez Díaz and Díaz Gómez (2007) as "the discomfort that students experience due to physical and emotional factors —whether interpersonal or intrapersonal— or environmental factors that place significant pressure on individual competence to cope within the school context, particularly regarding academic performance" (p. 14). Similarly, Bringhenti (1996) states that school stress includes demotivation, emotional exhaustion, interpersonal difficulties, and low satisfaction within the school environment.

Previous research has shown that maladaptive perfectionism can lead to higher levels of distress in senior students (Wuthrich et al., 2020) and may even contribute to certain aspects of academic burnout (i. e., cynicism and emotional exhaustion) in adolescents at this level (Seong et al., 2021). In terms of perfectionism facets, both self-oriented and socially prescribed perfectionism have been associated with school stress and some of its dimensions, including pressure to study, concern about grades, high expectations, and feelings of uneasiness or discouragement toward studying (Flett, Hewitt et al., 2016). Specifically, among primary school students, Latin American studies have shown that self-oriented perfectionism increases the likelihood of both family- and school-related stress (Aguilar Durán, 2019; Barba, 2019).

A recent Spanish study with secondary school students has found that self-oriented perfectionism and high parental expectations can be linked to higher levels of school stress in dimensions such as academic performance, fear of uncertainty, and school-leisure conflict. The study has also provided evidence of the moderating role of self-oriented perfectionism in connection to school stress (i. e., school-leisure conflict) and somatic symptoms (Díez et al., 2023).

As observed in this brief review of background literature, most studies focus on self-oriented and/or socially prescribed perfectionism. However, to date, no scientific studies have examined school stress in relation to all three dimensions proposed by the Hewitt and Flett model (1991), revealing a significant gap in research on this topic.

In light of the above, this study aimed to analyze the predictive role of maladaptive childhood perfectionism in school stress. Exploring the dynamics of this relationship and examining the distinct contribution of each dimension of perfectionism to school stress in primary school students could be highly relevant, both scientifically and practically, given recent findings suggesting that academic stress partially mediates the relationship between perfectionism, anxiety, and depression (Gil et al., 2023).

Method

Type of Study

A quantitative, cross-sectional, correlational study was conducted.

Participants

A non-probability sampling was used based on the researchers' access to different schools. The resulting sample consisted of n = 226 primary school students from the city of Posadas, Argentina. Of the total sample, 60.2 % were girls; 54 % were in the sixth grade, while the remainder were in seventh grade. The mean age was 11.58 (SD = .67).

Instruments

To assess self-oriented perfectionism, the Child Perfectionism Scale (Oros, 2003) was used. This self-administered instrument includes 16 items on a Likert-type scale with three response options (1: I don’t think about it/no; 2: I think about it sometimes/sometimes; 3: I think about it/yes), allowing for the assessment of self-oriented perfectionism across two subdimensions, each with eight items: Self-Demands, which evaluates self-imposed demands (e.g., “I need to be the best”; “I must always win”), and Maladaptive Reactions to Failure, which assesses responses to perceived failures (e.g., “I think a lot about the mistakes I made”; “I criticize myself a lot”). In this study, only the total scale score was used to represent the facet of self-oriented perfectionism facet without differentiating its factors.

The interpersonal dimensions of perfectionism were assessed using the Child Social Perfectionism Scale (Oros et al., 2019), which provides information on the two interpersonal dimensions of perfectionism: Socially prescribed, comprising nine items that assess the belief that others expect perfect performance (e.g., “My family wants me to be perfect”; “My teachers do not accept that I make mistakes”), and Other-oriented, comprising seven items that assess the demands for perfection imposed on others (e.g., “I get angry with my friends when they don’t want to get high grades”; “I hang out with the smartest people”). This questionnaire is also self-administered, using a Likert-type format with three response options (1: no, 2: sometimes, and 3: yes). The scale provides two scores representing each of the interpersonal facets of perfectionism; these scores are considered independently without calculating a total score.

These two scales assess perfectionism based on the multidimensional model proposed by Hewitt and Flett (1991). Recently, the simultaneous functioning of both instruments was studied, demonstrating adequate psychometric properties: the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) showed a good fit to the underlying theoretical model, comprising three factors (AGFI = .94; CFI = .93; RMSEA = .048; SRMR = .039). The internal consistency was found to be optimal, according to McDonald’s omega values (self-oriented perfectionism = .78; socially prescribed perfectionism = .82; other-oriented perfectionism = .71) (Oros et al., 2023). The Cronbach’s alpha values in this study indicate adequate internal consistency, as shown in Table 1.

To assess school stress, the School Stress Questionnaire (SSQ) by Bringhenti (1996) was used. Like the previous instruments, this is a self-administered questionnaire consisting of 35 items with a Likert scale format offering four response options (1: never, 2: sometimes, 3: almost always, and 4: always). This instrument measures school stress across three subscales: (a) Emotional Scale, consisting of twenty items that assess attitudes related to emotional exhaustion, demotivation, and dissatisfaction with school, studying, and teachers (e.g., “I am afraid that school will interest me less and less”; “I am very tired due to schoolwork”); (b) Interpersonal Tension Scale, comprising eight items that measure interpersonal difficulties, feelings of annoyance, and hostility towards certain members of the class group (e.g., “Being among my classmates makes me tense and nervous”; “I am afraid that my relationship with my classmates will become increasingly difficult”); and (c) Self-Concept Scale, with seven items that gather information on social aspects of self-esteem and school adaptation (e.g., “I feel comfortable in my class and at school”; “I feel useful when solving problems given by teachers”). The scale provides three partial scores, representing each dimension, and a total score representing school stress. The internal consistency of the total scale and each subscale was very good, as shown in Table 1.

Data Collection and Analysis Procedure

Following the favorable evaluation by the Ethics Committee of the Province of Misiones, the head teachers of both public and private primary schools in the city of Posadas were contacted to invite sixth and seventh-grade students to participate in this research. Once approval was obtained from each school, informed consent forms were provided to the head teachers and/or teachers for distribution among students to secure the approval of their legal guardians. The questionnaires were administered to the students who had had the consent forms signed, following an explanation of the study’s objectives and obtaining their verbal assent. The data collection was conducted in person, in groups, and on paper, with researchers present to minimize comprehension errors.

After data collection, the data were entered into Jamovi v.2.4.8. For the analysis, the total scores for the scales and subscales were calculated to construct indicators for each variable, and the reliability of the scales was assessed based on internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha). Next, the descriptive statistical analyses of the scales and subscales were conducted, including means, standard deviation, minimums, maximums, and indices of skewness and kurtosis. This was followed by the bivariate correlation analysis using Pearson correlation coefficient, r, with effect sizes evaluated based on the guidelines of Funder and Ozer (2019). Their guidelines suggest that r values of .05 represent a very small effect size for explaining events, while an r of .10 indicates an effect that —although potentially small at the individual event level— may hold greater relevance. Similarly, an r value of .20 suggests a medium effect size that may be both explanatory and practical, even in the short term; r values of .30 indicate a large and potentially strong effect, both in the short and long term; and finally, r values of .40 or higher represent very large effect sizes.