Ciencias Psicológicas, 19(1)

enero-junio 2025

10.22235/cp.v19i1.3956

Rasgos de personalidad y su relación con el uso de videojuegos en gamers argentinos

Personality traits and gaming in Argentinean gamers

Traços de personalidade e sua relação com o uso de videogames em gamers argentinos

Guadalupe de la Iglesia1, ORCID 0000-0002-0420-492X

1 Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (Conicet), Universidad de Palermo, Argentina, [email protected]

Resumen:

Introducción: Se ha postulado que la personalidad influye parcialmente en las conductas de uso de videojuegos. Esta investigación examinó la relación entre la personalidad normal y distintas variables de uso de videojuegos en una muestra de gamers argentinos. Método: Se trabajó con una muestra de 197 gamers y una muestra adicional de 91 no-gamers. Los datos se recolectaron mediante encuestas ad hoc, la Escala de Experiencia Gamer y el Inventario de los Cinco Grandes. Resultados: No se encontraron diferencias en los rasgos de personalidad entre gamers y no-jugadores ni relación entre la personalidad y las horas de uso de videojuegos. Quienes presentaron mayor apertura a la experiencia reportaron un mayor rendimiento autopercibido en el juego, y quienes tenían mayor extraversión interactuaron más con otros jugadores. No se hallaron diferencias en los rasgos de personalidad según la preferencia por juegos hardcore o casuales. Se observó que mayor responsabilidad se asoció con menos experiencias tanto negativas como positivas en el uso de videojuegos, mientras que una mayor apertura a la experiencia se relacionó con más experiencias positivas. Los hallazgos refuerzan la necesidad de controlar estadísticamente variables como género y edad, dado su impacto en los resultados. Conclusiones: Se concluye que no existe un perfil de personalidad distintivo que diferencie a los gamers de los no-jugadores. Además, en contraste con estudios previos, el neuroticismo no emergió como un rasgo clave en las conductas de uso de videojuegos. En cambio, la responsabilidad mostró un papel relevante en la modulación de las experiencias de juego, y la apertura a la experiencia se destacó como el principal predictor de las experiencias positivas y del rendimiento autopercibido en el juego.

Palabras clave: videojuegos; gamers; personalidad; rasgos.

Abstract:

Introduction: It has been proposed that personality partially influences gaming behaviors. This study examined the relationship between normal personality traits and various gaming behaviors and experiences in a sample of Argentine gamers. Method: The study included a sample of 197 gamers and an additional sample of 91 non-gamers. Data were collected using ad hoc surveys, the Gaming Experiences Scale, and the Big Five Inventory. Results: No differences in personality traits were found between gamers and non-gamers, nor was there a relationship between personality and the number of hours spent playing video games. Individuals with higher openness to experience reported greater self-perceived performance in gaming, while those with higher extraversion engaged more with other players. No differences in personality traits were found based on preference for hardcore or casual games. Higher conscientiousness was associated with fewer both negative and positive experiences in gaming, whereas greater openness to experience was related to more positive experiences. The findings highlight the need to statistically control for variables such as gender and age, given their impact on the results. Conclusions: The study concludes that gamers do not have a distinct personality profile that differentiates them from non-gamers. Moreover, contrary to previous research, neuroticism did not emerge as a key trait associated with gaming behaviors. Instead, conscientiousness played a relevant role in shaping gaming experiences, while openness to experience stood out as the strongest predictor of positive gaming experiences and self-perceived gaming performance.

Keywords: videogames; gamers; personality; traits.

Resumo:

Introdução: Tem-se postulado que a personalidade influencia parcialmente os comportamentos relacionados ao uso de videogames. Esta pesquisa examinou a relação entre a personalidade normal e diferentes variáveis de uso de videogames em uma amostra de gamers argentinos. Método: Trabalhou-se com uma amostra de 197 gamers e uma amostra adicional de 91 não-gamers. Os dados foram coletados por meio de questionários ad hoc, da Escala de Experiência Gamer e do Inventário dos Cinco Grandes Fatores de Personalidade. Resultados: Não foram encontradas diferenças nos traços de personalidade entre gamers e não-jogadores, nem relação entre a personalidade e o número de horas de uso de videogames. Aqueles que apresentaram maior abertura à experiência relataram um maior desempenho autopercebido no jogo, e os que tinham maior extroversão interagiram mais com outros jogadores. Não foram observadas diferenças nos traços de personalidade segundo a preferência por jogos hardcore ou casuais. Observou-se que maior responsabilidade se associou a menos experiências tanto negativas quanto positivas no uso de videogames, enquanto maior abertura à experiência esteve relacionada a mais experiências positivas. Os achados reforçam a necessidade de controlar estatisticamente variáveis como gênero e idade, dado o seu impacto nos resultados. Conclusões: Conclui-se que não existe um perfil de personalidade distinto que diferencie os gamers dos não-jogadores. Além disso, em contraste com estudos anteriores, o neuroticismo não emergiu como um traço chave nos comportamentos de uso de videogames. Por sua vez, a responsabilidade mostrou um papel relevante na modulação das experiências de jogo, e a abertura à experiência destacou-se como o principal preditor das experiências positivas e do desempenho autopercebido no jogo.

Palavras-chave: videogames; gamers; personalidade; traços.

Recibido: 18/03/2024

Aceptado: 31/03/2025

Introducción

El análisis de los rasgos de personalidad característicos de quienes juegan videojuegos (gamers) ha cobrado gran relevancia en las últimas décadas. Se ha postulado que la personalidad predetermina, en parte, las conductas de uso de videojuegos (Jeng & Teng, 2008). En teorías clásicas, pero vigentes, como la teoría de los usos y las gratificaciones (Katz et al., 1973), se propone que la personalidad constituye una característica individual que determina los diferentes consumos de medios audiovisuales de comunicación (como los videojuegos) en la búsqueda de la gratificación y satisfacción de necesidades personales (Chory & Goodboy, 2011).

Personalidad y uso de videojuegos

En general, el modelo predilecto para la investigación de la personalidad en gamers ha sido el Five Factor Model (FFM; Costa & McCrae, 1985). Sin embargo, los resultados en cuanto a los rasgos del FFM son sumamente variados y, en muchos casos, contradictorios. Cabe destacar, por ejemplo, una revisión sistemática y metaanálisis realizado por Akbari et al. (2021), que reveló una dispersión de resultados sin un patrón claro que vincule los rasgos del FFM con el uso de videojuegos. El único rasgo que presentaba cierta consistencia entre estudios era responsabilidad, que se asociaba negativamente con el uso de videojuegos. Esta variabilidad puede deberse a diferentes factores: los instrumentos de medición son heterogéneos, las muestras son muy diversas y, en general, las variables género y edad no se controlan estadísticamente. Este último aspecto es de suma importancia, ya que el estado del arte señala que tanto la personalidad como el uso de videojuegos varían según género y edad (e.g., De la Iglesia, 2024a; Jeng & Teng, 2008; Teng et al., 2012), por lo que esas diferencias preexistentes podrían impactar en los resultados observados. Aunque algunos estudios previos se han centrado en las diferencias de edad y género en relación con el uso de videojuegos y los rasgos de personalidad, este trabajo no se enfoca en analizar dichas diferencias. En su lugar, se busca controlar estadísticamente las variables género y edad para poder explorar la magnitud del vínculo entre los rasgos de personalidad y el uso de videojuegos, más allá de las diferencias preexistentes que puedan estar asociadas al género y la edad de los participantes.

Partiendo de estas consideraciones, el objetivo de esta investigación es estudiar los rasgos de personalidad en usuarios de videojuegos. En primera instancia, se pretende comparar los rasgos de personalidad entre gamers y no-jugadores para determinar si existen diferencias entre estos dos grupos. Además, se busca estudiar su relación con diversas variables asociadas al uso de videojuegos, tales como las horas de juego, el videojuego predilecto, el rendimiento autopercibido, la interacción con otros jugadores y las experiencias de juego.

A continuación, se resumen los antecedentes relacionados con los rasgos del FFM y las variables de uso de videojuegos.

Extraversión

Diversas investigaciones han explorado la relación entre extraversión y el uso de videojuegos. Por un lado, algunos estudios sugieren que los gamers presentan más extraversión que los no-jugadores (Estalló Martí, 1994; McClure & Mears, 1986; Teng, 2008). Sin embargo, Braun et al. (2016) encontraron que ésta es mayor en los no-jugadores y los gamers que juegan moderadamente, en contraste con quienes juegan excesivamente. En cuanto a la relación entre extraversión y el tiempo dedicado a los videojuegos, los resultados también son variados. Teng et al. (2012) no hallaron una asociación entre extraversión y horas de juego; Potard et al. (2020) observaron que los jugadores menos extravertidos jugaban menos; y Montag et al. (2021) encontraron una asociación inversa.

En relación al uso problemático de videojuegos (en ocasiones denominado adicción, uso patológico o experiencias negativas en el uso de videojuegos), en general se ha reportado una relación negativa con el rasgo extraversión (Braun et al., 2016; Charlton & Danforth, 2010; Chew, 2022; Dieris-Hirchea et al., 2020; Jeong & Lee, 2015; López-Fernández et al., 2020; Medina-Valdivia & Ponce-Eguren, 2021), o la ausencia de relación (Collins et al., 2012; Şalvarli & Griffiths, 2019). Huh y Bowman (2008), por el contrario, hallaron una relación positiva.

En lo que respecta a las motivaciones de uso, en los extravertidos prepondera la intención de socializar, el logro (rendimiento en el juego), el trabajo en equipo, la aventura y la búsqueda de relajación, y es menor la búsqueda de inmersión (Jeng & Teng, 2008; Park et al., 2011; Winther, 2010). Dentro del juego, los extravertidos suelen tener conductas de socialización, de ayuda y fanatismo por los contenidos del juego (Worth & Book, 2014). Además, en el contexto de World of Warcraft[1] (WOW), Yee et al. (2011) observaron que los jugadores más extravertidos participan más en actividades grupales (mazmorras, guilds o clanes) y menos en actividades individuales (explorar, cocinar, pescar). En cuanto a los géneros de preferencia, Peever et al. (2012) reportaron que a los extravertidos les gustan más los juegos casuales, de fiesta, de música y de estrategia; mientras que López-Fernández et al. (2020) hallaron una asociación con videojuegos etiquetados generalmente como hardcore: juegos de acción, shooters (juegos de disparos) y deportes.

Neuroticismo

En algunas investigaciones no se han reportado diferencias entre jugadores y no-jugadores en el neuroticismo (Teng, 2008). Braun et al. (2016), por el contrario, hallaron que el neuroticismo era mayor entre quienes no jugaban y quienes jugaban excesivamente en contraste con quienes jugaban moderadamente. En cuanto a las horas de juego, se han hallado asociaciones positivas con el neuroticismo (Braun et al., 2016; Jeong & Lee, 2015; Teng et al., 2012), aunque Collins et al. (2012) reportaron ausencia de relación. Respecto al uso problemático, existe una marcada tendencia a reportar asociaciones positivas con el neuroticismo (Akbari et al., 2021; Charlton & Danforth, 2010; Chew, 2022; Dieris-Hirchea et al., 2020; Gervasi et al., 2017; Huh & Bowman, 2008; Medina-Valdivia & Ponce-Eguren, 2021; Şalvarli & Griffiths, 2019) con resultados aislados que reportan ausencia de relación (Gervasi et al., 2017; López-Fernández et al., 2020; Şalvarli & Griffiths, 2019).

Por otro lado, quienes presentan más neuroticismo dicen jugar para socializar y experimentar inmersión (Winther, 2010). Dentro del juego, quienes tienen más neuroticismo tienen más conductas de ayudar a otros y fanatismo por los contenidos del juego (Worth & Book, 2014). En la investigación de Yee et al. (2011) en jugadores de WOW se reportó que quienes presentaban más neuroticismo preferían más actividades de player versus player (jugador contra jugador o PvP). En relación con los géneros de juego, Potard et al. (2020) hallaron que presentaban más neuroticismo quienes preferían juegos de acción.

Responsabilidad

Teng (2008) reportó que los gamers presentan más responsabilidad en comparación con los no-jugadores; mientras que Braun et al. (2016) reportaron lo contrario. Por otro lado, se halló que este rasgo se asocia negativamente con las horas de juego (Montag et al., 2021; Potard et al., 2020; Teng et al., 2012). En varias investigaciones se hallaron asociaciones negativas entre los puntajes de responsabilidad y el uso problemático (Akbari et al., 2021; Braun et al., 2016; Chew, 2022; Dieris-Hirchea et al., 2020; López-Fernández et al., 2020; Medina-Valdivia & Ponce-Eguren, 2021; Wang et al., 2014), mientras que en otras no se encontró relación (Collins et al. 2012; Jeong & Lee, 2015) o esta fue positiva (Lehenbauer-Baum & Fohringer, 2015).

Yee et al. (2011) hallaron que los jugadores de WOW con más responsabilidad suelen coleccionar ítems, tener más mascotas, cocinar más, pescar más y lograr más desafíos. Quienes tienen baja responsabilidad, en oposición, son más temerarios y tienen más posibilidad de que sus personajes mueran por caer de lugares altos. En cuanto a los géneros de juego, quienes tienen más responsabilidad suelen preferir juegos de carreras, de vuelo y de pelea (Peever et al., 2012).

Agradabilidad

Agradabilidad no presenta diferencias entre gamers y no-jugadores (Teng, 2008), y entre los gamers se encontró una relación positiva con la cantidad de horas de juego (Teng et al., 2012). En relación con el uso problemático, algunos estudios hallaron asociaciones negativas (Akbari et al., 2021; Charlton & Danforht, 2010; Chew, 2022; Collins et al., 2012; López-Fernández et al., 2020; Medina-Valdivia & Ponce-Eguren, 2021; Sánchez-Llorens et al., 2023), mientras que otros no encontraron relación (Braun et al., 2016; Dieris-Hirchea et al., 2020; Jeong & Lee, 2015).

Los motivos de uso de quienes tienen alta agradabilidad suelen ser socializar y la aventura (Park et al., 2011). En cuanto a la motivación relacionada al rendimiento al jugar, Park et al. (2011) reportaron una asociación positiva con este rasgo, y Winther (2010) una negativa. Dentro del juego, quienes tenían mayores puntajes de este rasgo solían ayudar a otros jugadores (Worth & Book, 2014). Además, los jugadores de WOW que son altamente agradables prefieren actividades no combativas (explorar, craftear [fabricar], eventos, cocinar, pescar), y quienes presentan baja agradabilidad se interesan más por matar, conseguir mejor equipamiento y actividades PvP (Yee et al., 2011).

Apertura a la experiencia

Finalmente, Teng (2008) encontró que los gamers presentan más apertura a la experiencia que los no-jugadores. Braun et al. (2016) no encontraron diferencias entre gamers y no-jugadores en este rasgo. En algunas investigaciones se encontró una asociación positiva con la cantidad de horas de juego (Teng et al., 2012; Witt et al., 2011), y en otra una negativa (Montag et al., 2021). En cuanto al uso problemático, no se encontró asociación con este rasgo (Dieris-Hirchea et al., 2020; Jeong & Lee, 2015) o la asociación hallada es de tipo negativa (Akbari et al., 2021; Braun et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2014). López-Fernández et al. (2020) reportaron una asociación positiva en el caso de las mujeres.

Con relación a los motivos de uso, quienes presentan más apertura a la experiencia buscan experimentar inmersión, descubrir, el juego de rol y socializar (Jeng & Teng, 2008; Winther, 2010; Worth & Brook, 2014), y dentro del juego suelen ayudar a otros jugadores (Worth & Book, 2014). Los jugadores de WOW con alta apertura a la experiencia suelen tener más personajes, explorar más y participar en actividades no combativas (Yee et al., 2011). En referencia a los géneros de videojuegos quienes tiene más apertura suelen preferir juegos de aventura, de acción, de plataformas, de lógica y de simulación social (López-Fernández et al., 2020; Peever et al., 2012).

Gamers argentinos

En Argentina, la investigación de los aspectos psicológicos ligados al uso de videojuegos tiene un desarrollo incipiente que incluye la validación de escalas para evaluar experiencias en el uso de videojuegos y adicción a los videojuegos, así como el estudio de variables de uso de videojuegos de acuerdo a características sociodemográficas y el vínculo del uso de videojuegos con la salud mental (e.g. De la Iglesia, 2024a, 2024b; González-Caino et al., 2022; Jordan-Muiños & Simkin, 2022). Localmente, se replica la tendencia internacional reportándose que 18.5 millones de argentinos juegan videojuegos (aproximadamente el 40 % de la población) y que el tamaño de la industria de los videojuegos está valuado en USD 72 millones (Gilbert, 2021). Las estadísticas describen un panorama en el que los videojuegos parecen constituir un aspecto de la vida cotidiana de casi la mitad de la población. Es por ello que su estudio resulta relevante tanto localmente, para la generación de conocimiento regional, como a nivel internacional, para contrastar y profundizar los conocimientos globales. De acuerdo a los objetivos expresados al inicio y a los antecedentes presentados, se plantean las siguientes hipótesis:

-H1. La cantidad de horas semanales de juego se asociará positivamente con el neuroticismo, la agradabilidad y la apertura a la experiencia, y negativamente con la responsabilidad.

-H2. Quienes prefieren videojuegos de géneros de tipo hardcore presentarán mayores niveles de neuroticismo y responsabilidad en comparación con quienes prefieren juegos de tipo casuales.

-H3. El rendimiento autopercibido al jugar se asociará positivamente con la extraversión y negativamente con la agradabilidad.

-H4. La interacción con otros jugadores se relacionará positivamente con la extraversión, la agradabilidad, la apertura a la experiencia y el neuroticismo.

-H5. Las experiencias negativas en el uso de videojuegos se asociarán positivamente con el neuroticismo y negativamente con la extraversión, la responsabilidad y la agradabilidad.

Método

Procedimientos

La investigación tuvo un diseño transversal no experimental, y los datos fueron recolectados mediante un muestreo no probabilístico por bola de nieve a través de una encuesta en línea difundida mediante redes sociales, correos electrónicos y plataformas digitales. Los participantes debían cumplir con los siguientes criterios de inclusión: (1) residir en Argentina, (2) tener 18 años o más y (3) jugar al menos una vez por mes algún videojuego —basado en la sugerencia de Eklund (2016) y Kaye (2019) en cuanto a utilizar criterios lo suficientemente amplios que permitan captar la diversidad de jugadores e incrementar la representatividad de quienes juegan videojuegos en la población general—. En el caso de la muestra de no-jugadores los criterios de inclusión eran los mismos a excepción del criterio 3, dado que se buscó no jugaran videojuegos. La muestra de no-jugadores solo se analizó para el primer objetivo de diferencias entre grupos. Asimismo, todos debían haber brindado su consentimiento informado de participación en el estudio en donde se daba información acerca de los objetivos de este, la posibilidad de negarse o interrumpir su participación en cualquier momento y el tratamiento confidencial de la información. No se brindaron incentivos para la participación. Todos los procedimientos respetaban los lineamientos y estándares éticos de la declaración de 1964 de Helsinki y sus enmiendas posteriores y del Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (Conicet). El proyecto fue evaluado y aprobado por el Comité de Ética de la Universidad de Palermo.

Participantes

La muestra se conformó por 197 adultos de población general que indicaron jugar videojuegos. La edad promedio fue 30.2 años (DE = 9.34; Mín = 18; Máx = 70), el 64.97 % dijo ser varón, el 32.99 % ser mujer, el 1.52 % no-binario y el 0.5 % prefirió no reportar su género. En cuanto a las horas de uso, el promedio fue de 13.3 horas por semana (DE = 13.5). De acuerdo a la clasificación de Przybylski (2014), el 47.6 % eran jugadores típicos, el 37 % moderados y el 15.3 % jugadores intensos. En el 75.3 % de los casos el videojuego de preferencia fue categorizado como hardcore, siendo el restante videojuegos casuales. El 29.1 % percibía que su rendimiento al jugar era bajo, 37.6 % que era estándar y 33.3 % que era alto. En referencia a la interacción online con otros jugadores, el 40.7 % dijo no interactuar, 21.2 % interactuar un poco, 17.5 % interactuar bastante y 20.6 % dijo interactuar mucho. Para los dos primeros análisis realizados, se evaluó una muestra adicional de 91 no-jugadores (Medad = 33.4 años; DE = 11.1; Mín = 19; Máx = 66; 87.91 % mujeres).

Materiales

Encuesta sociodemográfica (ad hoc). Elaborada para solicitar a los participantes información sobre sociodemográficos básicos como la edad, el género y el lugar de residencia.

Encuesta de uso de videojuegos (ad hoc). Se elaboró una encuesta con preguntas sobre cantidad de horas de juego semanales, videojuego de preferencia (categorizado en casual o hardcore), rendimiento autopercibido (escala única de rendimiento de seis opciones: 1: soy muy malo jugando a 6: juego espectacular) y frecuencia de interacción con otros jugadores (no, un poco, bastante y mucho).

Escala de Experiencia Gamer (De la Iglesia, 2024a). Este instrumento es una versión corta, y localmente adaptada para población argentina, del Online Gaming Survey (Snodgrass et al., 2017). Consta de 18 ítems que se responden en una Likert de seis opciones (0: no me representa para nada a 5: me representa completamente). Se valoran las experiencias positivas (fortalecer vínculos e incrementar las propias habilidades, la posibilidad de lograr una superación personal y la identidad gamer como forma de vida) y negativas (sensación de pérdida de control, el aislamiento social, la obsesión, la afectividad negativa, la abstinencia, problemas en otras áreas de la vida personal y el agotamiento). De sus análisis psicométricos se obtuvieron evidencias de validez (análisis factoriales exploratorios, confirmatorios, estudios de validez convergente) y confiabilidad (análisis de consistencia interna) que dieron cuenta de lo apropiado de sus puntuaciones compuestas. En la muestra aquí analizada la consistencia interna fue de w = .88 para las experiencias positivas y de w = .85 para las negativas.

Inventario de los Cinco Grandes [Big Five Inventory, BFI] (John et al., 1991). Este instrumento de 44 elementos evalúa los cinco grandes rasgos de personalidad: extraversión (i.e. “...que es sociable”), agradabilidad (i.e. “...a quien le gusta cooperar con los demás”), responsabilidad (i.e. “...que hace las cosas de modo eficiente”), neuroticismo (i.e. “...que es depresivo o triste”), apertura a la experiencia (i.e. “...que es curioso respecto de las cosas”). Utiliza una escala Likert de cinco posiciones de grado de acuerdo (0: completamente en desacuerdo a 4: completamente de acuerdo). Estudios realizados en Argentina verificaron la validez factorial para población adolescente y adulta no consultante y militar (Castro Solano & Casullo, 2001). Para esta muestra se obtuvieron valores de consistencia interna adecuados: extraversión w = .78; agradabilidad w = .69; responsabilidad w = .81; neuroticismo w = .82; apertura a la experiencia w = .81.

Análisis de datos

Los análisis se realizaron con los tamaños originales de los grupos, sin equiparación previa. Los grupos diferían en tamaño y composición de género debido a las características esperables de la población de estudio (Eklund, 2016; Vermeulen et al., 2011). Dado que estas diferencias podían influir en los análisis, la edad y el género fueron incluidos como covariables en todos los modelos estadísticos para controlar su impacto. En el caso de la variable género, esta se codificó como dummy representando la probabilidad de ser mujer. De acuerdo a la cantidad de horas de uso semanal se clasificaron los gamers en típicos (menos de siete horas por semana), moderados (entre 8 y 21 horas por semana) e intensos (más de 21 horas por semana; Przybylski, 2014). Además, se identificó el género y las características de los videojuegos preferidos por cada participante, clasificándolos como hardcore (e. g. shooters, de pelea, de acción/aventura, de supervivencia o de estrategia), es decir, juegos más cargados de contenido, con temáticas y narrativas más profundas y detalladas, que requieren de una mayor cantidad de tiempo de juego tanto para aprender a jugar como para jugarlos, o casuales (e.g. rompecabezas, juegos de palabras) que en general son más fáciles de jugar, con contenidos más livianos y que pueden jugarse intermitentemente sin necesidad de invertir una cantidad grande e ininterrumpida de tiempo de juego. Esta categorización sigue las definiciones propuestas en estudios previos (De Grove et al., 2015; Eklund, 2016; Kaye, 2019). El rendimiento autopercibido como gamer se recategorizó en tres: rendimiento bajo (“soy muy malo jugando”, “juego bastante mal”, “juego más o menos”), rendimiento estándar (“juego bien”), rendimiento alto (“juego muy bien”, “juego espectacular”). En cuanto a las experiencias de juego, se analizaron de acuerdo a las dos categorías (experiencias positivas y negativas) de la Escala de Experiencia Gamer (De la Iglesia, 2024a).

Los análisis estadísticos utilizados fueron r de Pearson, t de Student, ANOVAs one-way y regresiones jerárquicas múltiples. Se evaluó la multicolinealidad a través del Factor de Inflación de la Varianza (VIF). Los valores obtenidos estuvieron por debajo de 5, lo que indica una ausencia significativa de colinealidad entre los predictores (Hair et al., 2010). Además, se calcularon correlaciones r de Pearson parciales y ANCOVAs para controlar estadísticamente las variables de edad y género, las cuales fueron introducidas como covariables (De la Iglesia, 2024a). Se utilizó el software estadístico Jamovi en su versión 2.2.5 (Jamovi, 2022).

Resultados

En primer lugar, se compararon los rasgos de personalidad entre gamers y no-jugadores. Quienes jugaban algún tipo de videojuego tenían niveles más bajos de responsabilidad, t(286) = -4.17, p < .001, MG = 3.33, MNG = 3.69, y menos neuroticismo t(296) = -1.97, p =. 049, MG = 2.99, MNG = 3.20. Al realizar el mismo análisis con un ANCOVA controlado por edad y género, ya no se hallaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas (p > .05), lo que sugiere que el efecto estaba explicado en realidad por esas covariables.

Luego se analizaron las diferencias en los rasgos de acuerdo a la clasificación de Przybylski (2014). Se halló una única diferencia en responsabilidad, F(3,110) = 10.25, p < .001, y de acuerdo a la prueba pos hoc Tukey, la diferencia se daba entre los no-gamers en comparación con los gamers moderados y los gamers intensos, quienes tenían menos de este rasgo (MNG = 3.71 vs. MGM = 3.25 y MGI = 3.03). Al realizar el mismo cálculo con ANCOVAs controlado la edad y el género, los resultados perdieron su significación estadística y no se hallaron diferencias en ninguno de los rasgos (p > .05).

A continuación, se calcularon r de Pearson para estudiar las asociaciones entre los rasgos y la cantidad de horas de juego semanales. El único rasgo que presentó una asociación estadísticamente significativa fue responsabilidad, que se relacionó de manera negativa con la cantidad de horas de juego semanales (r = -.17, p < .05). Sin embargo, al controlar estadísticamente por edad y género, la relación perdía su significancia estadística (p > .05). Además, se puso a prueba un modelo de regresión jerárquica en el que se analizó el rol de los rasgos controlando en el Bloque 1 por edad y género y los cinco rasgos en el Bloque 2. No se observó una presencia significativa de colinealidad (VIF > 5). El modelo del Bloque 1 y 2 fueron estadísticamente significativos (p < .01), pero la inclusión de los rasgos de personalidad no incrementó significativamente la varianza explicada de la variable dependiente (p > .05). En ambos bloques, las únicas variables predictoras fueron edad y género.

Al comparar según el tipo de videojuego de preferencia, se halló que quienes jugaban videojuegos casuales tenían mayor puntaje en el rasgo responsabilidad, t(168) = 2.85, p < .01, MH = 3.25, MC= 3.60. Nuevamente, al controlar por edad y género los resultados perdían significancia estadística (p > .05).

Con relación al rendimiento autopercibido, se encontraron diferencias en neuroticismo F(2,120) = 3.28, p = .041 y apertura a la experiencia F(2,122) = 3.27, p = .041. Quienes reportaron tener un rendimiento alto presentaban menos neuroticismo, en contraste con quienes reportaron un rendimiento estándar, y más apertura a la experiencia que quienes dijeron tener un bajo rendimiento. Al controlar por edad y género, solo se sostuvo la diferencia en apertura a la experiencia, F(2,181) = 4.38, p = .014. Quienes percibían tener un rendimiento alto al jugar tenían mayores niveles de apertura a la experiencia en comparación con quienes tenían un rendimiento bajo (MA = 3.88 vs. MB = 3.59). No se hallaron diferencias en el resto de los rasgos (p > .05).

Además, se compararon los grupos de acuerdo a la frecuencia de interacción con otros usuarios en contexto de videojuegos y no se encontraron diferencias en ninguno de los rasgos (p > .05). Sin embargo, al controlarse por edad y género, se encontró una diferencia en extraversión F(3,180) = 3.22, p = .024. Quienes interactuaban con muchos usuarios eran más extravertidos que quienes no interactuaban con nadie (MM = 3.45 vs. MNO = 3.17). No se hallaron diferencias en el resto de los rasgos (p > .05).

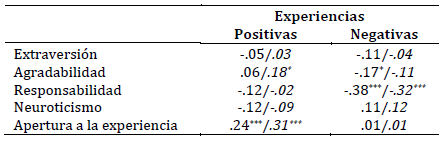

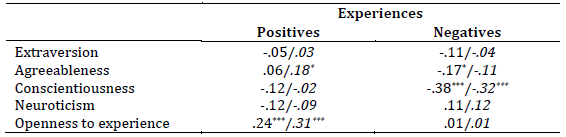

Para explorar la relación entre los rasgos de personalidad y las experiencias de uso de videojuegos se calcularon correlaciones (Tabla 1). Agradabilidad presentó una asociación negativa con las experiencias negativas, responsabilidad una asociación negativa con las experiencias negativas, y apertura a la experiencia una asociación positiva con las experiencias positivas. En las correlaciones parciales controladas por edad y género, agradabilidad presentó una asociación positiva con las experiencias positivas, y apertura a la experiencia mantuvo su significancia estadística. La asociación entre agradabilidad y experiencias negativas perdió su significancia estadística, y la asociación con responsabilidad se mantuvo.

Tabla 1: Asociaciones entre personalidad y experiencias de uso de videojuegos

Nota: En cursiva: correlaciones parciales controladas por edad y género.

*p <. 05; **p <. 01; ***p <. 001

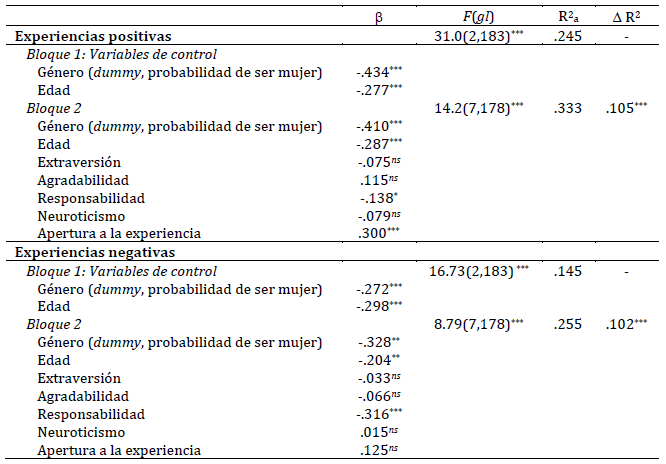

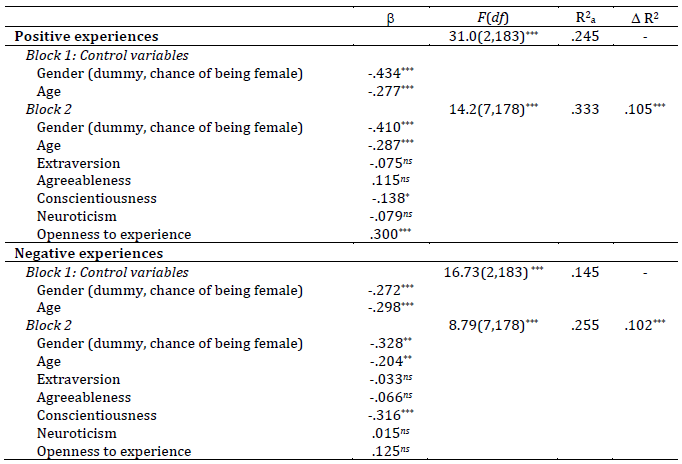

Por último, se pusieron a prueba dos modelos utilizando regresiones jerárquicas en los que analizó el rol de los rasgos controlando en el Bloque 1 por edad y género, y los cinco rasgos en el Bloque 2 (Tabla 2). En ninguno de los casos se observó una presencia significativa de colinealidad (VIF > 5). En cuanto a las experiencias positivas, ambos modelos fueron estadísticamente significativos (p < .001) y la inclusión de los rasgos en el Bloque 2 incrementó significativamente la varianza (p < .001). El modelo explicaba un 33.3 % de la variabilidad de las experiencias positivas. En el Bloque 2 eran predictores la edad, el género, la responsabilidad y la apertura a la experiencia. Con relación a las experiencias negativas, ambos modelos fueron estadísticamente significativos (p < .001) y la inclusión de los rasgos en el Bloque 2 incrementó significativamente la varianza (p < .001). El modelo explicaba el 25.5 % de la variabilidad de las experiencias negativas. En el Bloque 2 eran predictores la edad, el género y responsabilidad.

Tabla 2: Regresiones jerárquicas de predicción de las experiencias de uso de videojuegos

Nota: ns: no estadísticamente significativo

***p < .001; **p < .01; *p < .05

Discusión

Esta investigación tuvo por objetivo profundizar en el estudio del rol de los rasgos de personalidad normal en el uso de videojuegos. En una primera instancia se buscó comparar la personalidad entre gamers y no-jugadores. En el análisis inicial los gamers presentaron menores niveles de neuroticismo y responsabilidad en comparación con quienes no jugaban videojuegos. Sin embargo, al controlar estadísticamente por las variables género y edad, los resultados perdieron su significación estadística. Lo mismo ocurrió al comparar los grupos de acuerdo a la clasificación de Przybylski (2014). En el primer análisis se encontró que quienes no juegan videojuegos presentaban menos responsabilidad que los jugadores moderados y los intensos, pero luego, al controlar por edad y género, se perdió la significancia estadística. Estos hallazgos coinciden con aquellas investigaciones que reportan la ausencia de diferencias en la personalidad entre gamers y no-jugadores, y difieren con aquellos en las que sí se hallaron diferencias (Braun et al., 2016; Teng, 2008). Las diferencias ocasionalmente reportadas en neuroticismo y responsabilidad entre gamers y no-jugadores parecen estar explicadas por la edad y el género, y no por el hecho de jugar videojuegos en sí. Además, si se tiene en consideración que las estadísticas locales y mundiales reportan que casi la mitad de la población utiliza videojuegos (DFC Intelligence, 2020; Gilbert, 2021) resulta esperable que la variabilidad de la personalidad dentro de la población gamer sea similar a aquella presente en población no-jugadora, dado que refleja la diversidad presente en casi la mitad de la población general. Los resultados llevan a concluir que los gamers no tienen un perfil de personalidad diferente a quienes no juegan videojuegos.

La Hipótesis 1 postulaba que la cantidad de horas semanales de juego se asociarían positivamente con el neuroticismo, la agradabilidad y la apertura a la experiencia, y negativamente con la responsabilidad. Como pudo observarse tanto en las correlaciones (comunes y parciales) como en el modelo de regresión no se halló una relación significativa entre los rasgos de personalidad y las horas de uso por lo que la hipótesis debe ser rechazada. Las únicas variables que presentaron significancia estadística eran las sociodemográficas (edad y género). Este hallazgo contradice muchos antecedentes (Braun et al. 2016; Jeong & Lee, 2015; Montag et al., 2021; Teng et al., 2012; Potard et al., 2020; Witt et al., 2011) y esta diferencia posiblemente esté explicada por la ausencia de control estadístico de las variables sociodemográficas en las investigaciones precedentes.

En cuanto al tipo de videojuego predilecto, la Hipótesis 2 postulaba que quienes prefieren videojuegos de géneros de tipo hardcore presentarían mayores niveles de neuroticismo y responsabilidad en comparación con quienes prefieren juegos de tipo casuales. En esta investigación no se encontraron diferencias entre quienes prefieren un videojuego de tipo hardcore en contraste con uno de tipo casual, por lo que no se replican los hallazgos reportados en otras investigaciones (López-Fernández et al., 2020; Peever et al., 2012; Potard et al., 2020) y se rechaza esta hipótesis. Esto puede deberse a que esas diferencias efectivamente no existen o a que la clasificación utilizada (hardcore vs. casuales) resulta demasiado amplia y no capta la tendencia de subgrupos más específicos.

Además, se había hipotetizado que el rendimiento autopercibido dentro del juego se asociaría positivamente con la extraversión y negativamente con la agradabilidad (Hipótesis 3). No se encontraron asociaciones entre rendimiento autopercibido con extraversión ni agradabilidad tal como sugerían los antecedentes (Park et al., 2011; Winther, 2010) por lo que la Hipótesis 3 fue rechazada. Es posible que esta diferencia se deba a que la hipótesis estaba fundamentada en antecedentes que referían al rendimiento como una motivación para jugar (logro) y no al estudio de medidas objetivas o subjetivas de rendimiento. Sin embargo, se halló que tenían mayor rendimiento autopercibido quienes presentaban mayor apertura a la experiencia. Es posible que quienes se caracterizan por mayores puntajes en este rasgo cuenten con una mayor versatilidad y flexibilidad para los desafíos que se presentan en los videojuegos. El pensamiento abstracto, las ideas no convencionales y la curiosidad podrían llegar a favorecer el rendimiento en este entorno.

En relación con la Hipótesis 4, que postulaba que la interacción con otros jugadores se relacionaría positivamente con la extraversión, la agradabilidad y la apertura a la experiencia, se encontró evidencia que la corrobora en cuanto al rasgo extraversión. Los jugadores que dijeron interactuar más frecuentemente con otros jugadores tenían mayores niveles de este rasgo. Este resultado va en línea con los antecedentes y aporta a la idea de que los rasgos de personalidad offline se se podrían replicar en entornos virtuales (Winther, 2010; Worth & Book, 2014; Yee et al., 2011).

Por último, se había postulado una hipótesis referida a las experiencias negativas, dado que se podía hacer un paralelismo teórico con los componentes del uso problemático o desregulado de videojuegos (e.g. De la Iglesia, 2024a; Snodgrass et al., 2017). La Hipótesis 5 planteaba que existiría una relación positiva entre las experiencias negativas y el neuroticismo, y una negativa con la extraversión, la responsabilidad y la agradabilidad. En las asociaciones se halló que (controlándose por edad y género) presentan mayores experiencias positivas quienes tienen más agradabilidad y apertura a la experiencia, y mayores experiencias negativas quienes tienen menos responsabilidad. En los resultados de las regresiones múltiples, estos resultados variaron levemente. En cuanto a las experiencias positivas, agradabilidad perdió su significación estadística y responsabilidad emergió como un predictor negativo. En síntesis, al considerar la variabilidad de todos los rasgos juntos y controlar por edad y género, se observó que quienes tienen más responsabilidad tienen menos experiencias negativas y también menos experiencias positivas, y que quienes tienen más apertura a la experiencia reportan tener más experiencias positivas. De esta manera, la Hipótesis 5 se corrobora parcialmente para el rasgo responsabilidad.

En relación con los antecedentes, y equiparando a las experiencias negativas con el uso problemático (dado que se solapan conceptualmente en algunos aspectos), los resultados aquí obtenidos no replicarían la tendencia a hallar asociaciones negativas con el neuroticismo. pero sí aquellas con el rasgo responsabilidad (e.g. Akbari et al., 2021; Chew, 2022; Dieris-Hirchea et al., 2020). En este punto, el rasgo responsabilidad parece prevenir las experiencias relacionadas al uso problemático en cuanto a la sensación de pérdida de control sobre el uso de videojuegos, la obsesión por jugar, el nerviosismo por no poder jugar y problemas en otras áreas de la vida personal debido al uso de videojuegos. Este hallazgo coincide con una de las conclusiones del metaanálisis realizado por Akbari et al. (2021) en el que se destacó que este rasgo era el único que presentaba resultados consistentes a través de las investigaciones y su rol parece radicar en ser un factor protector del uso problemático o, como se denomina en esta investigación, las experiencias negativas en el uso de videojuegos. Asimismo, al momento de jugar, es posible que quienes se caracterizan por presentar baja responsabilidad y, por ende, en general tienen dificultades en establecer orden, prioridades y actuar planificadamente también presenten dificultades al jugar, dado que a pesar de ser una actividad recreativa, existen pautas y reglas que deben respetarse para lograr objetivos. Puede señalarse también que la ausencia de perseverancia, que es uno de los subaspectos de la responsabilidad y que es necesaria en muchos videojuegos para tener éxito en los objetivos, se asocie también a un incremento de experiencias negativas.

Respecto a las experiencias positivas, no existe un antecedente concreto con el cual comparar estos resultados. En el caso de la asociación positiva con agradabilidad, es posible que quienes presentan este rasgo, caracterizado por el trato cordial hacia los otros, la bondad y la sinceridad, la compasión y el altruismo, repliquen estas conductas dentro del juego y experimenten así interacciones positivas con otros jugadores, vean incrementado su sentido de pertenencia a un grupo, se sientan satisfechos por haber ayudado a otros o incluso por haber logrado objetivos sin recurrir a trampas. Sin embargo, en el análisis que contempló en conjunto la variabilidad de todos los rasgos (regresión jerárquica) esa asociación perdió su significación estadística. La asociación entre agradabilidad y el uso de videojuegos podría estar mediada por interacciones complejas con otros rasgos de personalidad, lo que explicaría la pérdida de significación al considerar todos los factores juntos. En cuanto a responsabilidad, la significancia estadística emergió al momento de contemplar la variabilidad de todos los rasgos juntos. De acuerdo a los antecedentes, la presencia de experiencias positivas y negativas se da de manera simultánea y está relacionada a la cantidad de horas de uso (De la Iglesia, 2024a). Es decir, no es excluyente para los jugadores presentar experiencias positivas o negativas, sino que, por el contrario, vivencian ambas en conjunto. Teniendo esto en consideración, cobra sentido que este rasgo esté relacionado tanto con las experiencias positivas como con las negativas. Debe tenerse en cuenta que la significancia estadística es relativamente límite (cercana al umbral de .05) y que de considerarse un umbral de significancia inferior este resultado debería descartarse. De tomarse en cuenta, se podría pensar que quienes presentan mayor responsabilidad posiblemente tengan dificultades para disfrutar de la actividad implicada en el uso de videojuegos, y experimenten la sensación de estar perdiendo el tiempo o dedicándose a algo improductivo. Finalmente, en cuanto a la asociación positiva con apertura a la experiencia, la cual resultó ser la más fuerte de todas, se podría hipotetizar que quienes tienen mayor nivel de este rasgo caracterizado por una alta curiosidad, interés por lo artístico, el pensamiento abstracto y novedoso, y una amplitud de intereses variada, dentro del terreno de los videojuegos encuentran un lugar en donde se sienten en sintonía con sus intereses y su forma de ser, dado que los videojuegos resultan ser un espacio con gran cantidad de componentes artísticos, de exploración, aventura y en muchos casos de creatividad para el usuario.

Limitaciones y futuras líneas de investigación

Esta investigación presenta algunas limitaciones que deben tenerse en cuenta al momento de considerar los resultados reportados. En principio, la muestra analizada es acotada y no probabilística, lo que impacta en la generalizabilidad de los hallazgos. En cuanto a la muestra, también se podría considerar la disparidad en la distribución de género entre las muestras de gamers (compuesta en gran proporción por hombres) y no-jugadores (sobrerrepresentación de mujeres). No obstante, es importante señalar que el predominio de varones en muestras de gamers y de mujeres en muestras de no-jugadores es habitual cuando los gamers que se estudian se caracterizan por jugar videojuegos hardcore, como ocurre en la mayoría de los jugadores de esta muestra (Eklund, 2016; Vermeulen et al., 2011). Para mitigar el posible impacto de esta disparidad, la variable género fue incluida como covariable en todos los análisis estadísticos realizados. Las medidas de rendimiento dentro del juego y de interacción fueron autorreportes y podrían no reflejar con exactitud los logros y las interacciones reales. Asimismo, la ausencia de resultados significativos al comparar jugadores que preferían videojuegos hardcore o casuales podría deberse a que esta clasificación es demasiado general. Esto podría solventarse con clasificaciones de género o escalas que evalúen este aspecto de manera más específica. Futuras líneas de investigación podrían superar estas limitaciones con muestreos aleatorizados más representativos y con mediciones obtenidas a partir del juego que resulten más precisas. Adicionalmente, se podrían poner a prueba análisis más complejos como el estudio de perfiles de personalidad y modelos explicativos que postulen variables mediadoras o moderadoras para explicar el fenómeno, tales como los modelos analizados por López-Fernández et al. (2021). Esta investigación se centró en los rasgos de personalidad normales, queda pendiente el estudio del uso de videojuegos y su relación con rasgos de personalidad patológicos y positivos.

Conclusiones

Se puede concluir que no existe un perfil de personalidad distintivo que diferencie a los jugadores de videojuegos de quienes no juegan y que los rasgos de personalidad no parecen tener un rol preponderante en cuanto a la cantidad de horas de juego. Sin embargo, sí parecen predeterminar parcialmente la forma en la que se experimenta el jugar. Además, se subraya la necesidad de considerar la heterogeneidad de la población gamer y la importancia de utilizar diseños de investigación que permitan controlar variables demográficas clave.

En cuanto a los rasgos específicos, no se replicó el gran peso atribuido al neuroticismo en estudios previos tanto en la cantidad de horas de juego como en el uso problemático o experiencias negativas. Por otro lado, se observó que un menor puntaje del rasgo responsabilidad se asocia con una menor incidencia de experiencias negativas al jugar, lo que sugiere que este rasgo podría actuar como un factor protector ante dichas experiencias. Este hallazgo abre nuevas líneas de investigación sobre estrategias de prevención del uso problemático de videojuegos. Sin embargo, también se encontró que los jugadores con baja responsabilidad tienden a presentar menos experiencias positivas al jugar, lo cual limitaría los beneficios potenciales asociados a jugar. Este efecto podría mitigarse mediante ajustes en el diseño de los videojuegos, adaptando la experiencia en función del nivel de responsabilidad del jugador. Asimismo, la apertura a la experiencia emergió como un rasgo central en la predicción de experiencias positivas de juego. Esto indica que las personas con mayor apertura tienden a beneficiarse más de los videojuegos en términos de creatividad, exploración y disfrute. En este sentido, fomentar el uso de videojuegos en individuos con alta apertura a la experiencia, pero que no son jugadores habituales, podría tener un impacto positivo.

Este estudio contribuye a una comprensión más matizada de la psicología del jugador. Los hallazgos obtenidos pueden orientar el desarrollo de videojuegos más personalizados, adaptados a distintos perfiles de personalidad, con el fin de optimizar la experiencia del jugador. Además, estos resultados podrían ser relevantes para la gamificación y su aplicación en contextos educativos, laborales y terapéuticos, lo que permitiría el diseño de experiencias más efectivas y ajustadas a los perfiles de personalidad de los usuarios.

Referencias

Akbari, M., Seydavi, M., Spada, M. M., Mohammadkhani, S., Jamshidi, S., Jamaloo, A., & Ayatmehr, F. (2021). The Big Five personality traits and online gaming: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Behavioral Addictions, 10, 611-625. https://doi.org/10.1556/2006.2021.00050

Braun, B., Stopfer, J. M., Müller, K. W., Beutel, M. E., & Egloff, B. (2016). Personality and video gaming: Comparing regular gamers, non-gamers, and gaming addicts and differentiating between game genres. Computers in Human Behavior, 55, 406-412. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.041

Castro Solano, A., & Casullo, M. M. (2001). Rasgos de personalidad, bienestar psicológico y rendimiento académico en adolescentes argentinos. Interdisciplinaria. Revista de Psicología y Ciencias Afines, 18(1), 65-85.

Charlton, J. P., & Danforth, I. D. W. (2010). Validating the distinction between computer addiction and engagement: online game playing and personality. Behaviour & Information Technology, 29(6), 601-613. https://doi.org/10.1080/01449290903401978

Chew, P. K. (2022). A meta-analytic review of Internet gaming disorder and the Big Five personality factors. Addictive Behaviors, 126, 107193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107193

Chory, R. M., & Goodboy, A. K. (2011). Is basic personality related to violent and non-violent video game play and preferences? Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14(4), 191-198. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2010.0076

Collins, E., Freeman, J., & Chamarro-Premuzic, T. (2012). Personality traits associated with problematic and non-problematic massively multiplayer online role playing game use. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(2), 133-138. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.09.015

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1985). The NEO Personality Inventory Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources. https://doi.org/10.1037/t07564-000

De Grove, F., Courtis, C., & Van Looy, J. (2015). How to be a gamer! Exploring personal and social indicators of gamer identity. Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication, 20, 346-361. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcc4.12114

De la Iglesia, G. (2024a). Experiencias en el uso de videojuegos en gamers argentinos. Psykhé, 33(2), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.7764/psykhe.2022.50493

De la Iglesia, G. (2024b). Salud mental en gamers argentinos: ¿juegan porque se sienten bien/mal? ¿se sienten bien/mal porque juegan? Revista de Psicopatología y Psicología Clínica, 29(2), 133-144. https://doi.org/10.5944/rppc.38260

DFC Intelligence. (2020). Global Video Game Consumer Segmentation.

Dieris-Hirchea, J., Pape, M., te Wildt, B. T., Kehyayana, A., Esch, M., Aicha S., Herpertz, S., & Bottel, L. (2020). Problematic gaming behavior and the personality traits of video gamers: A cross-sectional survey. Computers in Human Behavior, 106,106272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2020.106272

Eklund, L. (2016). Who are the casual gamers? Gender tropes and tokenism in game culture. En T. Leaver & M. Willson (Eds.), Social, casual and mobile games: The changing gaming landscape (pp. 15-29). Bloomsbury Academic. https://doi.org/10.5040/9781501310591.ch-002

Estalló Martí, J. A. (1994). Videojuegos, personalidad y conducta. Psicothema, 6(2), 181-190.

Gervasi, A. M., Marca, L. L., Costanzo, A., Pace, U., Guglielmucci, F., & Schimmenti, A. (2017). Personality and Internet gaming disorder: A systematic review of recent literature. Current Addiction Reports, 4(3), 293-307. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40429-017-0159-6

Gilbert, N. (2021). Number of Gamers Worldwide 2020/2021: Demographics, Statistics, and Predictions. https://financesonline.com/number-of-gamers-worldwide/

González-Caino, P., Resett, S., & Rodríguez, G. (2022). Validación de una escala de adicción a los videojuegos en jóvenes adultos argentinos. Psiencia, 14(1), 20-44.

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2010). Multivariate data analysis (7a ed.). Pearson.

Huh, S., & Bowman, N. D. (2008). Perception of and addiction to online games as a function of personality traits. Journal of Media Psychology, 13(2), 1-31.

Jamovi (2022). Jamovi. (Version 2.2.5) [Software]. https://www.jamovi.org.

Jeng, S. P., & Teng, C. I. (2008). Personality and motivations for playing online games. Social Behavior and Personality, 36(8), 1053-1060. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.2008.36.8.1053

Jeong, E. J., & Lee, H. R. (2015). Addictive use due to personality: Focused on Big Five personality traits and game addiction. International Journal of Psychological and Behavioral Sciences, 9(6), 1995-1999.

John, O. P., Donahue, E. M., & Kentle, R. L. (1991). The Big Five Inventory—Versions 4a and 54. University of California, Institute of Personality and Social Research.

Jordan-Muiños, F. M., & Simkin, H. (2022). Evidencias de validez de la versión corta de la Escala de Adicción a Videojuegos (GAS-SF) en una muestra de videojugadores argentinos. Psicodebate, 22(2), 60-75. https://doi.org/10.18682/pd.v22i2.5368

Katz, E., Blumler, J. G., & Gurevitch, M. (1973). Uses and gratification research. The Public Opinion Quarterly, 37(4), 509-523.

Kaye, L. K. (2019). Gaming classifications and player demographics. En A. Attrill-Smith, C. Fullwood, M. Keep & D. J. Kuss (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of cyberpsychology (pp. 609-623). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780198812746.013.1

Lehenbauer-Baum, M., & Fohringer, M. (2015). Towards classification criteria for Internet gaming disorder: Debunking differences between addiction and high engagement in a German sample of World of Warcraft players. Computers in Human Behavior, 45, 345-351. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.11.098

López-Fernández, F. J., Mezquita, L., Griffiths, M. D., Ortet, G., & Ibánez, M. I. (2020). El papel de la personalidad en el juego problemático y en las preferencias de géneros de videojuegos en adolescentes. Adicciones, 33(3), 263-272. https://doi.org/10.20882/adicciones.1370

López-Fernández, F. J., Mezquita, L., Ortet, G., & Ibáñez, M. I. (2021). Mediational role of gaming motives in the associations of the Five Factor Model of personality with weekly and disordered gaming in adolescents. Personality and Individual Differences, 182, 111063. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111063

McClure, R. F., & Mears, F. G. (1986). Videogame playing and psychopathology. Psychological Reports, 59, 59-62. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.1986.59.1.59

Medina-Valdivia, N. A., & Ponce-Eguren, A. (2021). Dependencia a los videojuegos y factores de la personalidad en jóvenes universitarios de la ciudad de Arequipa [Tesis de grado]. Universidad Católica San Pablo https://repositorio.ucsp.edu.pe/items/1c20cfa8-e9c9-44e2-b6de-ef1e6603bb60/full

Montag, C., Kannen, C., Schivinski, B., & Pontes, H. M. (2021). Empirical evidence for robust personality-gaming disorder associations from a large-scale international investigation applying the APA and WHO frameworks. PLOS ONE, 16(12), e0261380. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0261380

Park, J., Song, Y., & Teng, C. I. (2011). Exploring the links between personality traits and motivations to play online games. Cyberpsychology, Behavior, and Social Networking, 14(12), 747-751. https://doi.org/10.1089/cyber.2010.0502

Peever, N., Johnson, D., & Gardner, J. (2012, julio). Personality & video game genre preferences. Proceedings of the 8th Australasian Conference on Interactive Entertainment: Playing the System, 20, 1-3. https://doi.org/10.1145/2336727.2336747

Potard, C., Henry, A., Boudoukha, A. H., Courtois, R., Laurent, A., & Lignier, B. (2020). Video game players’ personality traits: An exploratory cluster approach to identifying gaming preferences. Psychology of Popular Media, 9(4), 499-512. https://doi.org/10.1037/ppm0000245

Przybylski, A. K. (2014). Electronic gaming and psychosocial adjustment. Pediatrics, 134(3), e716-e722. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2013-4021

Şalvarli, S. I., & Griffiths, M. D. (2019). Internet gaming disorder and its associated personality traits: A systematic review using PRISMA guidelines. International Journal of Mental Health and Addiction, 19, 1420-1442. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11469-019-00081-6

Sánchez-Llorens, M., Marí-Sanmillán, M., Benito, A., Rodríguez-Ruiz, F., Castellano-García, F., Almodóvar, I., & Haro, G. (2023). Rasgos de personalidad y psicopatología en adolescentes con adicción a videojuegos. Adicciones, 35(2), 151-164. https://doi.org/10.20882/adicciones.1629

Snodgrass, J. G., Dengah, H. J. F., Lacy, M. G., Bagwell, A., Oostenburg, M. V., & Lende, D. (2017). Online gaming involvement and its positive and negative consequences: A cognitive anthropological “cultural consensus” approach to psychiatric measurement and assessment. Computers in Human Behavior, 66, 291-302. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2016.09.025

Teng, C. I. (2008). Personality differences between online game players and nonplayers in a student sample. Cyberpsychology & Behavior, 11(2), 232-234. https://doi.org/10.1089/cpb.2007.0064

Teng, C. I., Jeng, S. P., Chang, H. K. C., & Wu, S. (2012). Who plays games online? The relationship between gamer personality and online game use. International Journal of E-Business Research, 8(4), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.4018/jebr.2012100101

Vermeulen, L., Van Looy, J., De Grove, F., & Courtois, C. (2011, enero). You Are What You Play? A Quantitative Study into Game Design Preferences across Gender and their Interaction with Gaming Habits [Conferencia]. Proceedings of Digital Games Research Association DiGRA, Netherlands.

Wang, C. W., Ho, R. T. H., Chan, C. L. W., & Tse, S. (2014). Exploring Personality Characteristics of Chinese Adolescents with Internet-Related Addictive Behaviors: Trait Differences for Gaming Addiction and Social Networking Addiction. Addictive Behaviors, 42, 32-35. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.addbeh.2014.10.039

Winther, D. (2010). Blood, gold or marriage – What gets you going? A study of personality traits and in-game behavior. iSCHANNEL, 5, 33-39.

Witt, E. A., Massman, A. J., & Jackson, L. A. (2011). Trends in youth’s videogame playing, overall computer use, and communication technology use: The impact of self-esteem and the Big Five personality factors. Computers in Human Behavior, 27, 763-769. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2010.10.025

Worth, N. C., & Book, A. S. (2014). Personality and behavior in a massively multiplayer online role-playing game. Computers in Human Behavior, 38, 322-330. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.06.009

Yee, N., Ducheneaut, N., Nelson, L., & Likarish, P. (2011, mayo). Introverted elves & conscientious gnomes: the expression of personality in world of warcraft. Proceedings of the SIGCHI conference on human factors in computing systems (pp. 753-762). https://doi.org/10.1145/1978942.1979052

Declaración de conflicto de intereses: Guadalupe de la Iglesia es socia de la Asociación de Desarrolladores de Videojuegos Argentina (ADVA).

Financiamiento: El presente trabajo fue subsidiado mediante el proyecto PICT 2020 SERIE A, Código 0181 de la Agencia Nacional de Promoción de la Investigación, el Desarrollo Tecnológico y la Innovación, y el proyecto PIBAA 2022-2023, Código 28720210100431CO del Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas.

Disponibilidad de datos: El conjunto de datos que apoya los resultados de este estudio no se encuentra disponible.

Cómo citar: De la Iglesia, G. (2025). Rasgos de personalidad y su relación con el uso de videojuegos en gamers argentinos. Ciencias Psicológicas, 19(1), e-3956. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v19i1.3956

Contribución de los autores (Taxonomía CRediT): 1. Conceptualización; 2. Curación de datos; 3. Análisis formal; 4. Adquisición de fondos; 5. Investigación; 6. Metodología; 7. Administración de proyecto; 8. Recursos; 9. Software; 10. Supervisión; 11. Validación; 12. Visualización; 13. Redacción: borrador original; 14. Redacción: revisión y edición.

G. de la I. ha contribuido en 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14.

Editora científica responsable: Dra. Cecilia Cracco.

Ciencias Psicológicas, 19(1)

January-June 2025

10.22235/cp.v19i1.3956

Original Articles

Personality traits and gaming in Argentinean gamers

Rasgos de personalidad y su relación con el uso de videojuegos en gamers argentinos

Traços de personalidade e sua relação com o uso de videogames em gamers argentinos

Guadalupe de la Iglesia1, ORCID 0000-0002-0420-492X

1 Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (Conicet), Universidad de Palermo, Argentina, [email protected]

Abstract:

Introduction: It has been proposed that personality partially influences gaming behaviors. This study examined the relationship between normal personality traits and various gaming behaviors and experiences in a sample of Argentine gamers. Method: The study included a sample of 197 gamers and an additional sample of 91 non-gamers. Data were collected using ad hoc surveys, the Gaming Experiences Scale, and the Big Five Inventory. Results: No differences in personality traits were found between gamers and non-gamers, nor was there a relationship between personality and the number of hours spent playing video games. Individuals with higher openness to experience reported greater self-perceived performance in gaming, while those with higher extraversion engaged more with other players. No differences in personality traits were found based on preference for hardcore or casual games. Higher conscientiousness was associated with fewer both negative and positive experiences in gaming, whereas greater openness to experience was related to more positive experiences. The findings highlight the need to statistically control for variables such as gender and age, given their impact on the results. Conclusions: The study concludes that gamers do not have a distinct personality profile that differentiates them from non-gamers. Moreover, contrary to previous research, neuroticism did not emerge as a key trait associated with gaming behaviors. Instead, conscientiousness played a relevant role in shaping gaming experiences, while openness to experience stood out as the strongest predictor of positive gaming experiences and self-perceived gaming performance.

Keywords: videogames; gamers; personality; traits.

Resumen:

Introducción: Se ha postulado que la personalidad influye parcialmente en las conductas de uso de videojuegos. Esta investigación examinó la relación entre la personalidad normal y distintas variables de uso de videojuegos en una muestra de gamers argentinos. Método: Se trabajó con una muestra de 197 gamers y una muestra adicional de 91 no-gamers. Los datos se recolectaron mediante encuestas ad hoc, la Escala de Experiencia Gamer y el Inventario de los Cinco Grandes. Resultados: No se encontraron diferencias en los rasgos de personalidad entre gamers y no-jugadores ni relación entre la personalidad y las horas de uso de videojuegos. Quienes presentaron mayor apertura a la experiencia reportaron un mayor rendimiento autopercibido en el juego, y quienes tenían mayor extraversión interactuaron más con otros jugadores. No se hallaron diferencias en los rasgos de personalidad según la preferencia por juegos hardcore o casuales. Se observó que mayor responsabilidad se asoció con menos experiencias tanto negativas como positivas en el uso de videojuegos, mientras que una mayor apertura a la experiencia se relacionó con más experiencias positivas. Los hallazgos refuerzan la necesidad de controlar estadísticamente variables como género y edad, dado su impacto en los resultados. Conclusiones: Se concluye que no existe un perfil de personalidad distintivo que diferencie a los gamers de los no-jugadores. Además, en contraste con estudios previos, el neuroticismo no emergió como un rasgo clave en las conductas de uso de videojuegos. En cambio, la responsabilidad mostró un papel relevante en la modulación de las experiencias de juego, y la apertura a la experiencia se destacó como el principal predictor de las experiencias positivas y del rendimiento autopercibido en el juego.

Palabras clave: videojuegos; gamers; personalidad; rasgos.

Resumo:

Introdução: Tem-se postulado que a personalidade influencia parcialmente os comportamentos relacionados ao uso de videogames. Esta pesquisa examinou a relação entre a personalidade normal e diferentes variáveis de uso de videogames em uma amostra de gamers argentinos. Método: Trabalhou-se com uma amostra de 197 gamers e uma amostra adicional de 91 não-gamers. Os dados foram coletados por meio de questionários ad hoc, da Escala de Experiência Gamer e do Inventário dos Cinco Grandes Fatores de Personalidade. Resultados: Não foram encontradas diferenças nos traços de personalidade entre gamers e não-jogadores, nem relação entre a personalidade e o número de horas de uso de videogames. Aqueles que apresentaram maior abertura à experiência relataram um maior desempenho autopercebido no jogo, e os que tinham maior extroversão interagiram mais com outros jogadores. Não foram observadas diferenças nos traços de personalidade segundo a preferência por jogos hardcore ou casuais. Observou-se que maior responsabilidade se associou a menos experiências tanto negativas quanto positivas no uso de videogames, enquanto maior abertura à experiência esteve relacionada a mais experiências positivas. Os achados reforçam a necessidade de controlar estatisticamente variáveis como gênero e idade, dado o seu impacto nos resultados. Conclusões: Conclui-se que não existe um perfil de personalidade distinto que diferencie os gamers dos não-jogadores. Além disso, em contraste com estudos anteriores, o neuroticismo não emergiu como um traço chave nos comportamentos de uso de videogames. Por sua vez, a responsabilidade mostrou um papel relevante na modulação das experiências de jogo, e a abertura à experiência destacou-se como o principal preditor das experiências positivas e do desempenho autopercebido no jogo.

Palavras-chave: videogames; gamers; personalidade; traços.

Received: 18/03/2024

Accepted: 31/03/2025

Introduction

The analysis of personality traits characteristic of gamers has gained considerable relevance in recent decades. It has been proposed that personality partially determines gaming behaviours (Jeng & Teng, 2008). According to classic but still relevant theories such as the Uses and Gratifications Theory (Katz et al., 1973), personality constitutes an individual characteristic that determines different types of consumption of audiovisual communication media (such as video games) in the pursuit of gratification and the fulfilment of personal needs (Chory & Goodboy, 2011).

Personality and Gaming

In general, the preferred model for researching personality in gamers has been the Five Factor Model (FFM; Costa & McCrae, 1985). However, the results regarding FFM traits are highly heterogeneous and, in many cases, contradictory. A systematic review and meta-analysis conducted by Akbari et al. (2021), for instance, revealed a dispersion of results, with no clear pattern linking FFM traits to gaming. The only trait that showed some consistency across studies was conscientiousness, which was negatively associated with gaming. This variability may be due to various factors: measurement instruments are heterogeneous, samples are highly diverse, and gender and age variables are generally not statistically controlled. This last point is particularly important, as the state of the art suggests that both personality and gaming vary according to gender and age (e.g., De la Iglesia, 2024a; Jeng & Teng, 2008; Teng et al., 2012), meaning that these pre-existing differences could affect the observed results. Although some previous studies have focused on age and gender differences in relation to gaming and personality traits, the present work does not aim to analyse those differences. Instead, it seeks to statistically control for gender and age variables in order to explore the strength of the link between personality traits and gaming, beyond any pre-existing differences that may be associated with participants’ gender and age.

Based on these considerations, the aim of this study is to examine personality traits in gamers. Initially, the objective is to compare personality traits between gamers and non-gamers to determine whether differences exist between these two groups. In addition, the study seeks to explore the relationship between personality and several variables associated with gaming, such as hours of gameplay, preferred video game, self-perceived performance, interaction with other players, and gaming experiences.

The following section summarises the background related to FFM traits and variables associated with gaming.

Extraversion

Numerous studies have examined the relationship between extraversion and gaming. Some findings suggest that gamers exhibit higher levels of extraversion compared to non-gamers (Estalló Martí, 1994; McClure & Mears, 1986; Teng, 2008). However, Braun et al. (2016) found that extraversion was higher in non-gamers and in moderate gamers compared to excessive gamers. Regarding the relationship between extraversion and hours of use, results are also mixed. Teng et al. (2012) found no association, Potard et al. (2020) observed that less extraverted individuals played less, and Montag et al. (2021) reported a negative association.

Problematic gaming (sometimes referred to as addiction, pathological use, or negative gaming experiences) generally shows a negative relationship with extraversion (Braun et al., 2016; Charlton & Danforth, 2010; Chew, 2022; Dieris-Hirchea et al., 2020; Jeong & Lee, 2015; López-Fernández et al., 2020; Medina-Valdivia & Ponce-Eguren, 2021), although some studies report no association (Collins et al., 2012; Şalvarli & Griffiths, 2019). Conversely, Huh and Bowman (2008) found a positive relationship.

In terms of motivations for play, extraverts are more inclined to seek socialisation, achievement (performance in the video game), teamwork, adventure, and relaxation, and are less likely to seek immersion (Jeng & Teng, 2008; Park et al., 2011; Winther, 2010). Within games, extraverts tend to engage in social behaviours, help others, and display fandom for game content (Worth & Book, 2014). In the context of World of Warcraft (WOW) [2], Yee et al. (2011) observed that more extraverted gamers participated more in group activities (dungeons, guilds, or clans) and less in solitary activities (exploring, cooking, fishing). Regarding preferred genres, Peever et al. (2012) reported that extraverts prefer casual, party, music, and strategy games, while López-Fernández et al. (2020) found associations with hardcore genres such as action, shooters, and sports.

Neuroticism

In some research, no differences have been reported between gamers and non-gamers in neuroticism (Teng, 2008). Braun et al. (2016), on the contrary, found that neuroticism was higher among non-gamers and those who played excessively in contrast to those who played moderately. Regarding gaming hours, positive associations with neuroticism have been found (Braun et al., 2016; Jeong & Lee, 2015; Teng et al., 2012), although Collins et al. (2012) reported no relationship. As for problematic use, there is a marked tendency to report positive associations with neuroticism (Akbari et al., 2021; Charlton & Danforth, 2010; Chew, 2022; Dieris-Hirchea et al., 2020; Gervasi et al., 2017; Huh & Bowman, 2008; Medina-Valdivia & Ponce-Eguren, 2021; Şalvari & Griffiths, 2019) with isolated results reporting no relationship (Gervasi et al., 2017; López-Fernández et al., 2020; Şalvari & Griffiths, 2019).

On the other hand, those who score higher in neuroticism report playing to socialize and experience immersion (Winther, 2010). Within the game, those with higher neuroticism exhibit more helping behaviors towards others and more fanaticism for game content (Worth & Book, 2014). In the research by Yee et al. (2011) on WOW players, it was reported that those with higher neuroticism preferred more player versus player (PvP) activities. Regarding game genres, Potard et al. (2020) found that those who preferred action games showed higher neuroticism.

Conscientiousness

Teng (2008) reported that gamers show more conscientiousness compared to non-gamers, and Braun et al. (2016) reported the opposite. On the other hand, this trait was found to be negatively associated with gaming hours (Montag et al., 2021; Potard et al., 2020; Teng et al., 2012). Several studies found negative associations between conscientiousness scores and problematic use (Akbari et al., 2021; Braun et al., 2016; Chew, 2022; Dieris-Hirchea et al., 2020; López-Fernández et al., 2020; Medina-Valdivia & Ponce-Eguren, 2021; Wang et al., 2014), while others found no relationship (Collins et al., 2012; Jeong & Lee, 2015) or a positive one (Lehenbauer-Baum & Fohringer, 2015).

Yee et al. (2011) found that WOW players with higher conscientiousness tend to collect items, have more pets, cook more, fish more, and achieve more challenges. Those with low conscientiousness, in contrast, are more reckless and have a higher chance of their characters dying from falling from high places. Regarding game genres, those with higher conscientiousness tend to prefer racing, flying, and fighting games (Peever et al., 2012).

Agreeableness

Agreeableness does not show differences between gamers and non-gamers (Teng, 2008), and among gamers, a positive relationship was found with the number of hours played (Teng et al., 2012). Regarding problematic use, some studies found negative associations (Akbari et al., 2021; Charlton & Danforth, 2010; Chew, 2022; Collins et al., 2012; López-Fernández et al., 2020; Medina-Valdivia & Ponce-Eguren, 2021; Sánchez-Llorens et al., 2023), while others found no relationship (Braun et al., 2016; Dieris-Hirchea et al., 2020; Jeong & Lee, 2015).

Motives for play among those with high agreeableness are often socializing and adventure (Park et al., 2011). Regarding performance-related motivation when playing, Park et al. (2011) reported a positive association with this trait, and Winther (2010) a negative one. Within the game, those with higher scores on this trait tended to help other players (Worth & Book, 2014). Furthermore, WOW players who are highly agreeable prefer non-combative activities (exploring, crafting, events, cooking, fishing), and those with low agreeableness are more interested in killing, getting better equipment, and PvP activities (Yee et al., 2011).

Openness to experience

Finally, Teng (2008) found that gamers show more openness to experience than non-gamers. Braun et al. (2016) found no differences between gamers and non-gamers in this trait. Some research found a positive association with the number of hours played (Teng et al., 2012; Witt et al., 2011), and another found a negative one (Montag et al., 2021). Regarding problematic use, no association was found with this trait (Dieris-Hirchea et al., 2020; Jeong & Lee, 2015), or the association found was negative (Akbari et al., 2021; Braun et al., 2016; Wang et al., 2014). López-Fernández et al. (2020) reported a positive association in the case of women.

In relation to motives for play, those with more openness to experience seek to experience immersion, discovery, role-playing, and socializing (Jeng & Teng, 2008; Winther, 2010; Worth & Brook, 2014), and within the game, they tend to help other players (Worth & Book, 2014). WOW players with high openness to experience tend to have more characters, explore more, and participate in non-combative activities (Yee et al., 2011). Regarding video game genres, those with more openness tend to prefer adventure, action, platform, logic, and social simulation games (López-Fernández et al., 2020; Peever et al., 2012).

Argentine Gamers

In Argentina, research on the psychological aspects linked to gaming is in an early stage of development, which includes the validation of scales to assess gaming experiences and video game addiction, as well as the study of gaming variables according to sociodemographic characteristics and the link between gaming and mental health (e.g., De la Iglesia, 2024a, 2024b; González-Caino et al., 2022; Jordan-Muiños & Simkin, 2022). Locally, the international trend is replicated, with reports indicating that 18.5 million Argentines play video games (approximately 40 % of the population) and that the size of the video game industry is valued at USD 72 million (Gilbert, 2021). These statistics describe a scene in which video games appear to constitute an aspect of daily life for almost half of the population. Therefore, their study is relevant both locally, for the generation of regional knowledge, and internationally, to contrast and deepen global understanding. According to the objectives expressed at the beginning of the introduction and the background research presented, the following hypotheses are proposed:

-H1. The number of weekly gaming hours will be positively associated with neuroticism, agreeableness, and openness to experience, and negatively with conscientiousness.

-H2. Those who prefer hardcore video game genres will present higher levels of neuroticism and conscientiousness compared to those who prefer casual games.

-H3. Self-perceived gaming performance will be positively associated with extraversion and negatively with agreeableness.

-H4. Interaction with other players will be positively related to extraversion, agreeableness, openness to experience, and neuroticism.

-H5. Negative gaming experiences will be positively associated with neuroticism and negatively with extraversion, conscientiousness, and agreeableness.

Method

Procedure