10.22235/cp.v18i2.3898

Validity evidence for the Family Role Overload Scale

Evidências de validade da Escala de Sobrecarga de Papéis na Família

Pruebas de la validez de la Escala de Sobrecarga del Rol Familiar

Juliana da Silva Sanches Leão1, ORCID 0000-0001-5893-5544

Larissa Maria David Gabardo-Martins2, ORCID 0000-0003-1356-8087

1 Universidade Salgado de Oliveira, Brazil, [email protected]

2 Universidade Salgado de Oliveira, Brazil

Abstract:

Role overload in the family can be understood as a feeling of inability to complete duties that are the individual's responsibility, and this hardship occurs due to the accumulation of tasks in the family, which can cause discomfort. The aim of this study was to obtain valid evidence of Family Role Overload in Brazilian samples. Six hundred and forty Brazilian workers of both genders took part in the study. Confirmatory factor analyses showed that the Brazilian version remained single-factor and had six items. The multi-group analyses showed configural, metric, and scalar invariance between the groups divided in terms of gender and the existence or absence of children. The scale showed positive correlations with perceived family demands and family-work conflict and a negative correlation with perceived social support in the family. It was therefore concluded that the instrument had psychometric properties that recommend its use in future research.

Keywords: role overload; family-work conflict; perceived social support; family demands; factor analysis.

Resumo:

A sobrecarga de papeis na família pode ser compreendida como sentimento de incapacidade em concluir obrigações que são de responsabilidade do indivíduo, e essa dificuldade acontece devido ao acúmulo de tarefas na família, que podem trazer desconforto. O presente trabalho teve por objetivo obter evidências de validade da Sobrecarga de Papéis na Família em amostras brasileiras. Participaram do estudo 640 trabalhadores brasileiros, de ambos os gêneros. As análises fatoriais confirmatórias evidenciaram que a versão brasileira se manteve unifatorial e com seis itens. As análises multigrupo atestaram a invariância configural, métrica e escalar entre os grupos divididos em termos de gênero e sobre a presença ou ausência de filhos. A escala apresentou correlações positivas com demandas percebidas da família e conflito família-trabalho e correlação negativa com suporte social percebido na família. Concluiu-se, assim, que o instrumento apresentou propriedades psicométricas que recomendam seu uso em investigações futuras.

Palavras-chave: sobrecarga de papéis; conflito família-trabalho; suporte social percebido; demandas familiares; análise fatorial.

Resumen:

La sobrecarga de rol en la familia puede ser entendida como un sentimiento de incapacidad para completar las obligaciones que son responsabilidad del individuo, y esta dificultad ocurre debido a la acumulación de tareas en la familia, lo que puede causar malestar. El objetivo de este estudio fue obtener evidencias de la validez de la Escala de Sobrecarga del Rol Familiar en muestras brasileñas. Participaron en el estudio 640 trabajadores brasileños de ambos sexos. Los análisis factoriales confirmatorios mostraron que la versión brasileña se mantuvo monofactorial y con seis ítems. Los análisis multigrupo mostraron invariancia configuracional, métrica y escalar entre los grupos divididos en función del género y de la presencia o ausencia de hijos. La escala mostró correlaciones positivas con las demandas familiares percibidas y el conflicto familia-trabajo y una correlación negativa con el apoyo social percibido en la familia. Por lo tanto, se concluyó que el instrumento posee propiedades psicométricas que recomiendan su uso en futuras investigaciones.

Palabras clave: sobrecarga de rol; conflicto familia-trabajo; apoyo social percibido; demandas familiares; análisis factorial.

Received: 15/02/2024

Accepted: 02/09/2024

Since the 20th century, when women entered the job market, family roles have undergone structural changes. Today, women can be home providers and men can carry out domestic activities. This means that there has been a reversal of roles, with women gaining a greater foothold in the business world and men partly taking on the responsibility of looking after the home and children (Fontgalland, 2021).

The division of tasks does not occur in the same way in all families. Ribeiro et al. (2023) analyzed the perception of working men about the division of household chores, compared to their wives, who also work. The results showed inequality since these men perceived that their wives performed more household chores than they did. Araújo et al. (2019) point out that male participation has increased in terms of household chores, however, they state that these are primarily aimed at meeting their own needs, such as washing their own clothes.

In some families, the father plays little part in caring for the children. In this family model, mothers are mainly responsible for raising and educating their children, referring to the traditional family model. According to Macêdo (2020), women often have to make their working hours more flexible to cope with household chores, which results in feelings of overload.

Regarding this subject, Thiagarajan et al. (2006) pointed out that single parents are more prone to role overload because they need to plan their time and energy to meet all their family and work responsibilities. Based on the aforementioned assertions, it can be said that the feeling of role overload is commonly experienced in contemporary families. This construct can be understood as the feeling of being unable to complete the tasks that are the individual's responsibility. This feeling arises when the demands on time and energy associated with multiple tasks are too overwhelming, making it difficult to carry them out and leaving the individual feeling uncomfortable at not being able to do them.

With regard to measuring role overload, Reilly's Role Overload Scale was developed in 1982 to analyze role overload in women who work double shifts. The study included a sample of 106 married women. The results showed a single-factor version made up of 13 items. The internal consistency index, calculated by Cronbach's alpha, was .88. This instrument's psychometric properties have been tested in different studies on role overload (i.e., Maher et al., 1997; Marks & MacDermid, 1996; Thiagarajan et al., 2006).

Marks and MacDermid's (1996) study involved 65 married female workers with at least one child under the age of 18 living at home in the United Kingdom. The results of the confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) showed a version of eight items and one factor. The internal consistency index (Cronbach's alpha) was .89. Maher et al. (1997) conducted a study with a sample of 155 American female university students. The results of the CFA showed a version of seven items and one factor. The internal consistency index (Cronbach's alpha) was .89. In the study by Thiagarajan et al. (2006), a sample of 535 single parents was used. The CFA showed a version of six items and one factor. The internal consistency index (Cronbach's alpha) was .89.

As can be seen, the empirical studies that used the scale reached contradictory conclusions regarding its internal structure. Considering the principle of parsimony, according to which if there are different alternatives for the same phenomenon, and there is no difference between them, the simplest should be chosen, as it is the one that has the chance of being the most correct (De Andrade & Antunes, 2023), it was decided to adapt and search for evidence of validity of the six-item version by Thiagarajan et al. (2006).

The Role Overload Scale (Reilly, 1982) was developed in the North American setting and, according to a survey carried out in the Scielo and Pepsic databases in July 2023, has not yet been adapted to the Brazilian setting. However, it is an important tool for expanding studies on family role overload and its impact on different life contexts. It can compare role overload among various social actors by characteristics such as gender, race, marital status, and having children. This analysis can further discussions on social issues like sexism and racism, as demonstrated by Mota-Santos et al. (2021), who found that women still bear most domestic responsibilities.

In an organizational context, the instrument helps managers understand employees' family demands, potentially providing a competitive edge. Organizations that address workers' family needs might retain employees seeking a better work-life balance (Moreira et al., 2021). Hence, organizations that understand and address family demands contribute to a more inclusive environment (De Oliveira Rapozo & Vianna Brugni, 2023).

The COVID-19 pandemic significantly impacted workers' daily lives and family experiences (De Santana & Roazzi, 2021), highlighting work-family conflict and its negative effects on health (Dos Santos et al., 2022). Despite the return to in-person work, many organizations maintain remote or hybrid work models. Understanding family role overload can help tailor tasks, improve well-being, and enhance satisfaction and performance (Wang et al., 2021).

Based on these considerations, the aim of this study was to adapt and gather initial evidence of the validity of the Role Overload Scale (Thiagarajan et al., 2006) in the Brazilian scenario. Specifically, it sought to obtain validity evidence based on internal structure, internal consistency, invariance of item parameters, and correlations with related constructs. Considering the structure of scale, the following hypothesis was formulated:

Hypothesis 1: The Brazilian version of the Role Overload Scale will consist of one factor and six items.

The invariance of an instrument is an important technique in the development and use of psychometric instruments, as it allows conclusions to be drawn about the invariance of the instrument's configuration and parameters in different groups, which will enable its future use in those groups (Fischer & Karl, 2019). Two different groups were compared and subdivided according to gender and the existence of children. With regard to gender, it was observed that social changes and the inclusion of women in the labour market have changed both men's and women's routines. As a result, women now have less time to dedicate to the family and men have to dedicate themselves more actively to family life. However, women continue to be primarily responsible for household chores and consequently experience greater stress when performing their roles in the family than men (Garcia & Marcondes, 2022).

As for the existence of children, studies show that people who have children, especially women, have a greater burden on the family due to caring for them (Park, 2021). However, despite these differences, it would be desirable for the parameters of the items in the Role Overload Scale to be stable, i.e., for them to be invariant in these different groups, which would guarantee the use of the scale in them (Fischer & Karl, 2019). That said, the following hypothesis was formulated:

Hypothesis 2: The items on the Role Overload Scale are invariant according to gender and whether or not they have children.

To obtain evidence based on correlations with related constructs, the following constructs were used: perceived family demands, family-work conflict, and perceived social support in the family. Perceived family demands refer to the subject's perception of their level of responsibility in their family (Gabardo-Martins & Ferreira, 2019). Considering that both role overload and perceived family demands can be considered stressors in the family context, it would be expected that these variables would be positively correlated. With this in mind, the following hypothesis was formulated:

Hypothesis 3: Role overload is positively related to the perceived demands of the family.

Family-work conflict, in turn, occurs when family demands are incompatible with work in such a way that participation in work is impaired due to the depletion of the individual's personal resources. When managing family tasks, feelings of overload can emerge (Lemos et al., 2020). The following hypothesis was therefore developed:

Hypothesis 4: Role overload is positively related to family-work conflict.

Perceived social support in the family refers to the perception of the roles played by family members in order to help the individual in certain situations (Ribeiro et al., 2019). In this way, as social support in the family occurs, the individual is helped to cope with the demands of the family, feeling less burdened in terms of family tasks (Felisberto & Soratto, 2023). Therefore, the following hypothesis was formulated:

Hypothesis 5: Role overload is negatively related to perceived social support in the family.

Method

Participants

The convenience sample included 640 Brazilian workers from 25 states and the Federal District, with most from Rio de Janeiro (58.3 %) and São Paulo (15.5 %). The majority were female (78 %). Most participants were married or living as married (60.5 %), followed by single respondents (31.3 %). Educational backgrounds were primarily post-graduate (52.3 %) and complete higher education (27.7%). Work sectors were: private (38.0 %), public (33.2 %), and self-employed (28.8 %). Work modalities included in-person (63.3 %), hybrid (23.9 %), and remote (12.8 %). Most respondents had children (59.5 %) and did not hold management positions (68.6 %). Ages ranged from 18 to 70 (M = 37.4; SD = 10.9). Length of service in the current job ranged from 1 to 38 years (M = 6.7; SD = 7.4) and total length of service from 1 to 50 years (M = 14; SD = 10.6). Inclusion criteria were being employed, over 18, of any gender, and available for the survey.

Instruments

Role overload in the family was assessed using the Role Overload Scale, confirmed by Thiagarajan et al. (2006), adapted to the family context. Thus, the expression "in my family" was inserted into the items. This instrument consists of six items. The items were answered using a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from never (1) to always (7). Example item: "In my family, I have to do things that I don't have the time and energy for". The scale obtained an internal consistency of .89 (Cronbach's Alpha) in the original study. To translate the scale, the translation and retranslation procedure was adopted, which consists of translating the items into Portuguese, then translating this version back into English and comparing the two versions to check for conceptual equivalence (Cruchinho et al., 2024). Following some of these authors' recommendations, the original instrument was first translated from English into Portuguese by a researcher fluent in English. In the second stage, the Portuguese version was translated back into English by an English-speaking teacher. Finally, in the next stage, two researchers in the field of scale adaptation carried out a technical review and assessment of the semantic equivalence of the two English versions.

Family demands were assessed using the family factor of the Perceived Demands of Work and Family Scale (Gabardo-Martins & Ferreira, 2019). This factor consists of four items, which were answered using a five-point Likert scale, ranging from strongly disagree (1) to strongly agree (5). Example item: "My family demands all my attention". The CFA showed that the single-factor structure, with four items, obtained adequate fit indices (χ² (df) = 6.38 (2); CFI = .999; TLI = .998; RMSEA = .059 (.010-.099)), and was therefore chosen to represent the internal structure of the instrument. In this study, the internal consistency indices, Cronbach's Alpha and McDonald's Omega, were equal to .88.

Family-work conflict was measured using the family interference at work dimension of the Work-Family Conflict Scale (Aguiar & Bastos, 2013). This dimension consists of five items, to be answered using a six-point Likert scale, ranging from totally disagree (1) to totally agree (6). Example item: “My family's demands interfere with my work activities". The CFA showed that the single-factor structure, with five items, obtained adequate fit indices (χ² (df) = 24.33 (5); CFI = .992; TLI = .984; RMSEA = .078 (.049-.010)). In the current investigation, the internal consistency indices, Cronbach's Alpha and McDonald's Omega, were .90.

Social support was measured by the family factor of the Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (Gabardo-Martins et al., 2017). This is a factor made up of four items, to be answered using a seven-point Likert scale, ranging from very strongly disagree (1) to very strongly agree (7). Example item: "My family genuinely tries to help me". The CFA showed that the single-factor structure, with four items, obtained adequate fit indices (χ² (df) = 11.90 (2); CFI = .996; TLI = .987; RMSEA = .088 (.044-.0139)). In this study, the internal consistency indices, Cronbach's Alpha and McDonald's Omega, were α = .91 and Ω = .92. In addition, along with the scales, a sociodemographic questionnaire was also administered in order to obtain the sample's characteristics.

Procedures and ethical considerations

Initially, the project was submitted to the authors' institution's Research Ethics Committee. After approval (CAAE no. 59288322.0.0000.5289), the participants were contacted electronically. The application was online, in which they were first given brief explanations about the research objectives, followed by a link that took them directly to the survey's initial screen. Once completed, the respondent's information was stored and made up the survey database. Only respondents who agreed to take part in the survey by signing the Free and Informed Consent Term were accepted. In addition, respondents were informed about the risks and benefits of taking part in the research, as well as the voluntary nature of the research and the anonymity of their responses.

Data analysis procedures

The information collected was tabulated in the Jamovi statistical software (version 2.2.5), followed by analysis using the Lavaan package in the RStudio software. The scale's internal structure was tested using CFA and Structural Equation Modeling. The Weighted Least Square Mean and Variance Adjusted (WLSMV) estimator was used, in which the items were declared as categorical-ordinal variables. The invariance of the item parameters was tested using Multigroup Confirmatory Factor Analyses, models were tested in which the number of items and factors (configural invariance), factor loadings (metric invariance), and intercepts (scalar invariance) were fixed. When the differences in the fit indices (CFI and RMSEA) of these models are less than 0.01, the item parameters are considered invariant (Fischer & Karl, 2019).

The fit indices were assessed in accordance with the recommendations of Goretzko et al. (2024), for whom a model that fits the data well must meet the following indicators: ꭓ²/df < 5; CFI > .95; TLI > .95; RMSEA < .08. To assess the reliability of each scale, the internal consistency indices were calculated using Cronbach's Alpha coefficient and McDonald's Omega. The correlation between the Role Overload Scale and the other related constructs was investigated by calculating factor correlations.

Results

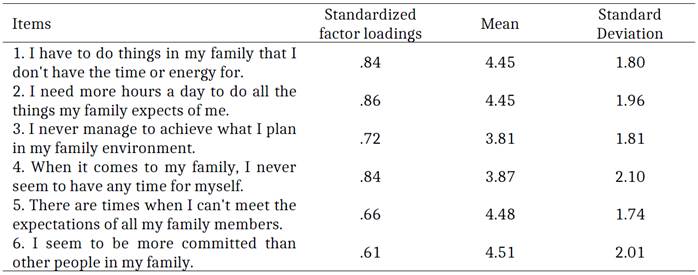

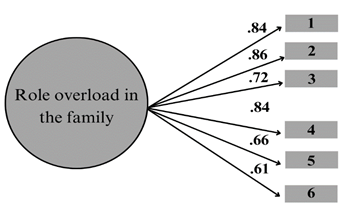

Initially, the single-factor structure of the Family Role Overload Scale was tested using CFA. The results showed that this structure had good fit indices: χ²(df) = 84.94 (9); CFI = .986; TLI = .977; RMSEA = .066 (.044-.091), as well as high standardized factor loadings (.61 to .86). The internal consistency indices were also adequate: .87 (Cronbach's Alpha) and .87 (McDonald's Omega). The results then showed that the Brazilian version of the Family Role Overload Scale remained with the six items from the original version, distributed in one dimension, which corroborates Hypothesis 1. Table 1 shows the description of the items, with their respective standardized factor loadings, mean and standard deviation. Figure 1 shows the graphical representation of the final model of the Family Role Overload Scale.

Table 1: Items and Standardized Factor Loadings, Mean and Standard Deviation of the Family Role Overload Scale

Figure 1: Graphical representation of the final model of the Family Role Overload Scale

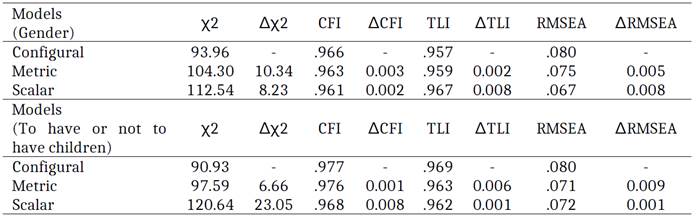

We then tested the invariance of the instrument's parameters in terms of gender (male and female) and whether or not they had children, using the Multigroup Confirmatory Factor Analysis (MCFA). The analysis revealed that the imposition of restrictions resulted in small and practically negligible differences in the indicators analysed (differences in CFI and RMSEA were less than 0.01). These results (Table 2) indicate that, for the one-factor model, the factor loadings, thresholds, and scalars were invariant between the groups analysed (Fischer & Karl, 2019), which allowed Hypothesis 2 to be confirmed.

Table 2: Results of the MCFA

Note: χ2: chi-squared; CFI: Comparative Fix Index; TLI: Tucker–Lewis Index; RMSEA: Root Mean Square Error of Approximation; Δ difference; n men = 141; n women = 499; n having children = 381; n not having children = 259.

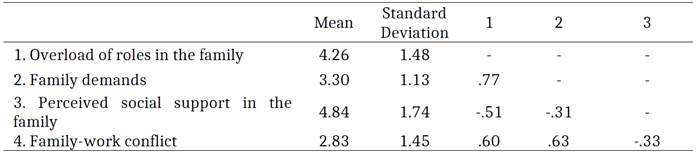

The correlations between the variables were calculated using a measurement model, in which all four variables were inserted as latent variables. The results showed positive and significant correlations between family role overload and family demands and family-work conflict, as well as a negative and significant correlation between family role overload and perceived family social support, which allowed the study's Hypotheses 3, 4, and 5 to be confirmed (Table 3). In addition, this model showed good fit indices (χ²(df) = 761.77 (146); CFI = .973; TLI = .68; RMSEA = .081 (.076-.087)), indicating that the items were being explained by their latent variables.

Table 3: Mean, Standard Deviation, Correlation Between Study Variables

Note: All correlations had a significance level of p < .001.

Because role overload had high correlations (> .50) with the external variables, evidence of discriminant validity was calculated to check whether the constructs, although correlated, were minimally different from each other. To this end, the model obtained was compared with a model in which the correlations were set at 1, to check whether these models were significantly different (p < .05). The results showed evidence of discriminant validity between family role overload and family demands (χ2 diff = 49.03; df diff = 1; p < .001), perceived social support in the family (χ2 diff = 162.35; df diff = 1; p < .001) and work-family conflict (χ2 diff = 120.02; df diff = 1; p < .001), indicating that despite high correlations, these constructs can be considered minimally different.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to adapt and gather initial evidence of the validity of the Family Role Overload Scale in the Brazilian context. The study results showed that the instrument had adequate psychometric properties in terms of internal structure, internal consistency, invariance of item parameters, and the correlation between family role overload and external variables. This study therefore has various theoretical and practical implications.

The CFA showed that the single-factor model obtained adequate fit indices and was therefore chosen to represent the instrument's internal structure. These results are consistent with the construction and validation study of the original instrument (Thiagarajan et al., 2006), in which a single-factor, six-item internal structure was also obtained. Thus, the final Brazilian version of the Family Role Overload Scale was composed of one factor and six items, confirming Hypothesis 1. Therefore, this study adds cross-cultural evidence to the conclusion that the unifactorial model is the most appropriate for describing the instrument.

The scale showed good levels of internal consistency. These results are congruent with those obtained in different studies that have used the instrument (Maher et al., 1997; Marks & MacDermid, 1996; Reilly, 1982; Thiagarajan et al., 2006). These findings indicate that the instrument's score can be estimated with high precision, even with the reduced number of items, in samples of different nationalities. It was therefore possible to verify that the instrument's scores are minimally accurate, i.e., with few measurement errors due to the lack of internal consistency.

With regard to the invariance of the instrument's item parameters, the aim was to analyse whether the factor structure found was invariant with regard to gender, as well as the existence or absence of children. As expected, the results showed that the family role overload scores obtained using the scale are invariant for the different groups analysed. These results confirm Hypothesis 2, in which the instrument behaves in the same way in the different groups, without response bias (Fischer & Karl, 2019).

With regard to the correlation between the scale and external variables, it was observed that role overload in the family showed a strong positive correlation with the perceived demands of the family. This finding confirms Hypothesis 3 and is consistent with the reports by Nogueira et al. (2020) who indicated a positive correlation between excessive demands and feelings of overload. A possible explanation for this finding lies in the fact that when individuals perceive an increase in their tasks in the family environment, they tend to feel more overwhelmed.

In addition, the results showed a positive correlation between family role overload and family-work conflict, corroborating Hypothesis 4. The study by Vatharkar and Aggarwal-Gupta (2020) found a similar result. These results show that workers who feel a greater overload of family roles also experience greater family-work conflicts, i.e. adversities in the family context, which in turn interfere at work. In other words, the multiple tasks of the family wear the individual down and can lead to greater adversity and difficulty in completing work tasks.

There was also a negative correlation between role overload in the family and perceived social support in the family, confirming Hypothesis 5. It is possible to understand this result due to the fact that workers who feel less role overload in the family are those who also have greater social support in their family environment. A study that indicates a similar result is that of Rakap et al. (2023), which points out that individuals who have more social support from their spouses feel less of an impact from the burden of caring for children with special needs. Thus, through the support received, the individual is better able to deal with family tasks without feeling overwhelmed (Felisberto & Soratto, 2023).

The results of the correlations obtained between family role overload and the external variables constitute evidence of the scale's convergent validity. Together with the results on the validity of its internal structure, internal consistency, and invariance, they reaffirm the possibilities of using the instrument to assess role overload in the family environment in Brazil.

This study also makes practical contributions. The use of this scale in clinical psychotherapy can broaden knowledge about this reality, including among the patients themselves. In the clinical context, the psychologist can draw up strategies together with the patient, planning interventions in the way the subject relates to the demands of the family, by understanding how these impacts on their wellbeing and also on their work results. In addition, this scale can be used in family therapies, such as couple's therapy, raising awareness among those involved and promoting equal demands in the family, opening up space for cultural changes in the role of women and men in their families. In the organizational context, the instrument can provide business managers with the opportunity to learn more about the family demands of their employees, which can help seek solutions to assist employees in balancing work and family responsibilities, thereby increasing well-being of worker.

As far as the limitations of this study are concerned, we can mention the fact that the instrument used is a self-report, and therefore there may be differences between the individual's perception and reality as it stands. Another important limitation is that the majority of respondents were concentrated in the Southeast region, more specifically in the Rio-São Paulo axis. As such, it is not possible to generalize the results to the whole of Brazil, since there are important regional differences that could be better explored. In addition, it should be noted that the data was collected completely online, without the presence of the researcher, which may have led to less interest on the part of the respondents with regard to the reliability of the answers.

It is suggested that future studies investigate the difference in family configurations, pointing out individuals who, in addition to their shared responsibilities with other people, also look after their elderly parents or grandparents, or a family member with special needs. Future research could include longitudinal and diary studies, as well as comparative studies across different populations, such as adults vs. adolescents or men vs. women, to explore varying perceptions of role overload in the family. Additionally, investigating how role overload manifests in various family contexts -such as violent environments, single-parent families, recent divorces, distant members, families with young children, or members with special needs- could enhance understanding and reveal ways to address or reduce family role overload.

In short, this study's results indicate that the Family Role Overload Scale showed initial evidence of validity in terms of internal structure, internal consistency, invariance, and relationships with external variables in a Brazilian sample. Therefore, it can be considered an appropriate measure for assessing family role overload. In addition, the use of this instrument can help in research aimed at reducing family-work conflict and family demands and improving quality of life and well-being. Finally, this scale makes it possible to open up new avenues and interventions to improve health and well-being.

Referências:

Aguiar, C. V. V., & Bastos, A. V. B. (2013). Tradução, adaptação e evidências de validade para a medida de conflito trabalho-família. Avaliação Psicológica, 12(2), 203-212.

Araújo, C., Gama, A., Picanço, F., & Cano, I. (2019). Gênero, família e trabalho no Brasil do século XXI: Mudanças e permanências. Gramma Editora.

Cruchinho, P., López-Franco, M. D., Capelas, M. L., Almeida, S., Bennett, P. M., Miranda da Silva, M., Teixeira, G., Nunes, E., Lucas, P., & Gaspar, F. (2024). Translation, cross-cultural adaptation, and validation of measurement instruments: A practical guideline for novice researchers. Journal of Multidisciplinary Healthcare, 17, 2701-2728. https://doi.org/10.2147/jmdh.s419714

Da Silva, M. M. D., Dos Santos, G. G., & Dos Santos, L. G. (2024). O perfil social, demográfico e econômico dos egressos no curso técnico em Mecânica do Instituto Federal de Alagoas, Campus Maceió. Rebena-Revista Brasileira de Ensino e Aprendizagem, 8, 327-341.

De Andrade, F. R., & Antunes, J. L. F. (2023). Tiempo y memoria en el análisis de series temporales. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde, 32(1), e2022867. https://doi.org/10.1590/S2237-96222023000100027

De Oliveira Rapozo, F., & Vianna Brugni, T. (2023). Arranjos flexíveis de trabalho e seus efeitos no equilíbrio trabalho-lar, estresse tecnológico e satisfação com o trabalho durante a pandemia do covid-19. Revista de Educação e Pesquisa em Contabilidade (REPeC), 17(3). https://doi.org/10.17524/repec.v17i3.3251

De Santana, A. N., & Roazzi, A. (2021). Home Office e COVID-19: Investigação meta-analítica dos efeitos de trabalhar de casa. Revista Psicologia Organizações e Trabalho, 21(4), 1731-1738. https://doi.org/10.5935/rpot/2021.4.23198

Dos Santos, D. Y. S., de Almeida, D. M., & Menegazzi, R. B. (2022). Uma análise do home office e dos seus impactos causados no âmbito do conflito trabalho-família. Revista Expectativa, 21(2), 140-155. https://doi.org/10.48075/revex.v21i3.28450

Facchinetti, C., & Carvalho, C. (2019). Loucas ou modernas? Mulheres em revista (1920-1940). Cadernos Pagu, (57), e195707. https://doi.org/10.1590/18094449201900570007

Felisberto, K. K., & Soratto, M. T. (2023). Sobrecarga da família do paciente em sofrimento mental. Inova Saúde, 15(1), 30-43. https://doi.org/10.18616/inova.v15i1.3447

Fischer, R., & Karl, J. A. (2019). A primer to (cross-cultural) multi-group invariance testing possibilities in R. Frontiers in Psychology, 10. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01507

Fontgalland, I. L. (2021). Mulheres como chefes de família: retratos da paraíba, do Nordeste e do Brasil. Editora Amplla. https://doi.org/10.51859/amplla.mcf931.1121-0

Gabardo-Martins, L. M. D., & Ferreira, M. C. (2019). Psychometric properties of perceived work and family demand scale. Avaliação Psicológica, 18(3), 276-284. http://doi.org/10.15689/ap.2019.1803.16152.07

Gabardo-Martins, L. M. D., Ferreira, M. C., & Valentini, F. (2017). Family resources and flourishing at work: The role of core self-evaluations. Paidéia, 27(68), 331-338. https://10.1590/1982-43272768201711

Garcia, B. C., & Marcondes, G. S. (2022). Reproduction inequalities: Men and women in unpaid domestic work. Revista Brasileira de Estudos de População, 39, e0204. https://doi.org/10.20947/S0102-3098a0204

Goretzko, D., Siemund, K., & Sterner, P. (2024). Evaluating model fit of measurement models in confirmatory factor analysis. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 84(1), 123-144. https://doi.org/10.1177/00131644231163813

Lemos, A. H. D. C., Barbosa, A. D. O., & Monzato, P. P. (2020). Mulheres em home office durante a pandemia da covid-19 e as configurações do conflito trabalho-família. Revista de Administração de Empresas, 60(6), 388-399. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0034-759020200603

Macêdo, S. (2020). Being a working woman and mother during a COVID-19 Pandemic: Sewing senses. Revista do NUFEN, 12(2), 187-204. https://doi.org/10.26823/RevistadoNUFEN.vol12.nº02rex.33

Maher, J. K., Marks, L. J., & Grimm, P. E. (1997). Overload, pressure, and convenience: Testing a conceptual model of factors influencing women’s attitudes toward, and use of, shopping channels. Advances in Consumer Research, 24(1), 490-498.

Marks, S. R., & MacDermid, S. M. (1996). Multiple roles and the self: A theory of role balance. Journal of Marriage and the Family, 58(2), 417-432. https://doi.org/10.2307/353506

Moreira, L. M., Oliveira Junior, M., Sadocco, R. R. S., de Faria, D. W., Bassotto, L. C., Pereira, A. L. C., Ferreira, P. A., Da Silva Teodoro, A. J., Diniz, I. R., & Putti, F. F. (2021). Evasão maternal: que políticas as empresas vêm adotando para não perder suas funcionárias para a maternidade? Um estudo multicaso. Research, Society and Development, 10(1), e24010111737. https://doi.org/10.33448/rsd-v10i1.11737

Mota-Santos, C., de Azevedo, A. P., & Lima-Souza, É. (2021). A mulher em tripla jornada: Discussão sobre a divisão das tarefas em relação ao companheiro. Revista Gestão & Conexões, 10(2), 103-121. https://doi.org/10.47456/regec.2317-5087.2021.10.2.34558.103-121

Nogueira, M. T. D., Rusch, F. S., & Alves, G. D. G. S. (2020). Mães de crianças com o transtorno do espectro autista: estresse e sobrecarga. Revista Humanitaris, 2(2), 54-75.

Park, E.-Y. (2021). Validity and reliability of the Caregiving Difficulty Scale in mothers of children with cerebral palsy. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(11), 5689. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18115689

Rakap, S., Vural-Batik, M., & Coleman, H. (2023). Predictors of family burden in families caring for children with special needs. Journal of Childhood, Education & Society, 4(1), 56-71. https://doi.org/10.37291/2717638X.202341245

Reilly, M. D. (1982). Working wives and convenience consumption. Journal of Consumer Research, 8(4), 407-418. https://doi.org/10.1086/208881

Ribeiro, C. M., Salvador, R. V. A., & Carvalho, P. S. (2019). Predictors of quality of life and perceived social support in people with chronic mental disorders: Preliminary study. Revista Portuguesa de Investigação Comportamental e Social, 5(1), 14-24. https://doi.org/10.31211/rpics.2019.5.1.100

Ribeiro, F. F. M. Q., Mora-Santos, C. M., Neto, A. C., & Neto, M. B. G. (2023). Por que os homens participam menos da divisão do trabalho doméstico? Uma discussão a partir de sua própria percepção. Economia e Gestão, 23(64), 25-40. https://doi.org/10.5752/P.1984-6606.2023v23n64p25-40

Thiagarajan, P., Taylor, R. D., & Chakrabarty, S. (2006). A confirmatory factor analysis of Reilly's Role Overload Scale. Educational and Psychological Measurement 66(4), 657-666. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164405282452

Vatharkar, P. S., & Aggarwal-Gupta, M. (2020). Relationship between role overload and the work-family interface. South Asian Journal of Business Studies, 9(3), 305-321. https://doi.org/10.1108/SAJBS-09-2019-0167

Wang, B., Liu, Y., Qian, J., & Parker, S. K. (2021). Achieving effective remote working during the Covid-19 pandemic: A work design perspective. Applied Psychology, 70(1), 16-59. https://doi.org/10.1111/apps.12290

Data availability: The dataset supporting the results of this study are available at Zenodo https://zenodo.org/records/10368434

How to cite: Da Silva Sanches Leão, J., & Gabardo-Martins, L. M. D. (2024). Validity evidence for the Family Role Overload Scale. Ciencias Psicológicas, 18(2), e-3898. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v18i2.3898

Authors’ contribution (CRediT Taxonomy): 1. Conceptualization; 2. Data curation; 3. Formal Analysis; 4. Funding acquisition; 5. Investigation; 6. Methodology; 7. Project administration; 8. Resources; 9. Software; 10. Supervision; 11. Validation; 12. Visualization; 13. Writing: original draft; 14. Writing: review & editing.

J. D. S. L. has contributed in 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 7, 8, 13; L. M. D. G. in 4, 9, 10, 11, 12, 14.

Scientific editor in-charge: Dra. Cecilia Cracco.