Ciencias Psicológicas; v18(2)

Julio-Diciembre 2024

10.22235/cp.v18i2.3849

Efeitos emocionais elicitados por imagens de futebol: Um estudo sobre o fanatismo

Emotional effects elicited by football images: A study on fanaticism

Efectos emocionales desencadenados por imágenes de fútbol: Un estudio sobre el fanatismo

Monick Leonora Inês Kort-Kamp1, ORCID 0000-0001-8019-6215

Thauan Rocha Porto2, ORCID 0000-0002-3360-5271

Roberdson Silveira de Oliveira3, ORCID 0000-0001-9142-8851

Erick Francisco Conde4, ORCID 0000-0002-7130-2888

1 Universidade Federal Fluminense, Brasil

2 Universidade Federal Fluminense, Brasil

3 Universidade Federal Fluminense, Brasil

4 Universidade Federal Fluminense, Brasil, [email protected]

Resumo:

O presente estudo investigou os efeitos da visualização de imagens de times favoritos e rivais nos indicadores de valência e ativação emocional, averiguando possíveis interações com os níveis de fanatismo em torcedores de futebol. Participaram deste experimento 27 voluntários (M = 22 anos; DP = 3,25), que avaliaram a agradabilidade (valência hedônica) e a excitação emocional (ativação) desencadeada por um conjunto de imagens neutras, positivas e negativas do Sistema Internacional de Figuras Afetivas (IAPS), acrescido de 30 imagens experimentais pareadas, sendo 15 do time favorito e 15 do time rival. As avaliações foram realizadas através da escala Self Assessment Manikin (SAM) e da Escala de Fanatismo em Torcedores de Futebol (EFTF). Análises comparativas demonstraram que o nível de fanatismo não influenciou na atribuição da valência hedônica às imagens. Contudo, o grupo com níveis mais altos de fanatismo apresentou maior excitação emocional em resposta a imagens neutras (p < 0,01; d = 0,914), do time favorito (p < 0,01; d = 1,49) e do time rival (p < 0,01; d = 0,83). A análise de dispersão sugeriu o envolvimento dos sistemas motivacionais apetitivo e aversivo em reação às imagens do time favorito e rival, respectivamente. Os resultados do estudo auxiliam na compreensão do fenômeno do fanatismo no futebol.

Palavras-chave: f fanatismo; futebol; valência afetiva; ativação emocional; psicologia do esporte.

Abstract:

The present study investigated the effects of the favorite and rival team visualization on valence and emotional arousal indicators, verifying for possible interactions with the fanaticism level in soccer fans. Twenty-seven volunteers (Mage = 22; SD = 3.25) participated in this experiment, who evaluated the pleasantness (hedonic valence) and the emotional arousal (activation) triggered by a set of neutral, positive and negative images of the International System of Affective Pictures (IAPS) plus 30 experimental images of the favorite and rival team. Evaluations were performed using the Self Assessment Manikin (SAM) scale and the Football Supporter Fanatism Scale (FSFS). Comparative analysis revealed that fanaticism did not influence the assignment of hedonic valence to the images. However, individuals with higher levels of fanaticism exhibited greater arousal in response to neutral (p < .01; d = 0.914), favorite (p < .01; d = 1.49), and rival images (p < .01; d = 0.83). The dispersion analysis suggested the involvement of appetitive and aversive motivational systems in response to images of the favorite and rival teams, respectively. The study findings lead to a better understanding of the fanaticism in soccer.

Keywords: fanaticism; soccer; affective valence; emotional arousal; sport psychology.

Resumen:

El presente estudio investigó los efectos de la visualización de imágenes de equipos favoritos y rivales en los indicadores de valencia y activación emocional para averiguar la interacción con los niveles de fanatismo de los hinchas de fútbol. Veintisiete voluntarios (M = 22 años; DE = 3.25) participaron en este experimento, quienes evaluaron la agradabilidad (valencia hedónica) y la excitación emocional (activación) desencadenada por un conjunto de imágenes neutrales, positivas y negativas del International System of Affective Pictures (IAPS), con más de 30 imágenes experimentales del equipo favorito y el rival. Las evaluaciones se realizaron utilizando la escala Self Assessment Manikin (SAM) y la Escala de Fanatismo en Hinchas de Fútbol (EFHF). Análisis comparativos demostraron que el nivel de fanatismo no influyó en la atribución de la valencia hedónica de las imágenes. Sin embargo, las personas con niveles más altos de fanatismo presentaron una excitación superior ante imágenes neutras (p < .01; d = 0.914), imágenes del equipo favorito (p < .01; d = 1.49) e imágenes del equipo rival (p < .01; d = 0.83). El análisis de dispersión sugirió la implicación de los sistemas motivacionales apetitivos y aversivos en respuesta a las imágenes del equipo favorito y rival, respectivamente. Los resultados del estudio ayudan a comprender el fanatismo en el fútbol.

Palabras clave: fanatismo; fútbol; valencia afectiva; excitación emocional; psicología del deporte.

Recebido: 22/01/2024

Aceito: 17/10/2024

O futebol é um esporte popularizado em todo o mundo, se consolidando como um fenômeno transcultural capaz de gerar impactos relevantes em nossa sociedade (Wann & James, 2018). Para além da dimensão econômica e outros impactos sociais, os conflitos entre torcedores vêm requisitando a adoção de políticas públicas nas áreas de seguridade social e mobilidade urbana, com relevantes implicações socioeconômicas (Louis, 2023). Quando se fala em violência no futebol, pode-se dizer que o Brasil apresenta índices alarmantes. Evidências sugerem que o Brasil pode ser considerado como um dos principais países no mundo onde mais se mata por motivos relacionados ao futebol (Brandão et al., 2020; Murad, 2017). Dados demonstram também uma tendência de aumento no número de julgamentos realizados pelo Supremo Tribunal de Justiça Desportiva referentes a processos relacionados à violência nos estádios (Castro, 2014).

A literatura tem demonstrado que o simples processamento visual de estímulos afetivos já é capaz de influenciar parâmetros como a fisiologia e o comportamento humano (Mulckhuyse, 2018; Polo et al., 2024; Zsidó, 2024). Mas especificamente tratando do futebol, pesquisas já demonstraram que a simples observação de imagens relacionadas a esse esporte é capaz de desencadear a ativação de circuitos emocionais no cérebro de torcedores (Duarte et al., 2017; Kelly et al., 2009; Park et al., 2009). Park et al. (2009) demonstraram que a percepção do time favorito em circunstâncias de vitórias, pode desencadear ativação assimétrica de estruturas límbicas, como a amígdala, predominantemente no hemisfério esquerdo. Para as derrotas, os pesquisadores detectaram um padrão de ativação cerebral indicadora de supressão emocional.

Estudos comportamentais já verificaram que estímulos de futebol também podem modular a cognição e o comportamento motor (Conde et al., 2011; Conde et al., 2018; Oliveira et al., 2021). Através de um protocolo de medida do tempo de reação, conhecido como tarefa de compatibilidade estímulo-resposta, é possível verificar diferenças temporais significativas nas respostas aos times favorito e rival. Mais especificamente, utilizando como estímulos-alvo imagens representando jogadores de futebol dos principais times do Rio de Janeiro, Conde et al. (2011) adaptaram a tarefa atencional de compatibilidade estímulo-resposta para estudar se a variável “preferência” poderia modular os tempos de resposta a estímulos representando o time favorito e o principal rival de cada participante. Os estímulos poderiam aparecer à esquerda ou à direita do ponto de fixação e as respostas deveriam ser realizadas com teclas de resposta posicionadas ipsi ou contralateralmente. De forma balanceada, os participantes foram orientados a responderem com a tecla do mesmo lado em resposta ao time preferido (condição compatível) e com a tecla do lado oposto (condição incompatível) em resposta ao time rival. No segundo bloco realizavam o pareamento oposto. Os pesquisadores reportaram um efeito clássico de compatibilidade espacial para os estímulos do time favorito, sendo as respostas espacialmente correspondentes aos estímulos mais rápidas do que as respostas espacialmente incompatíveis. Enquanto, para o time rival, fora verificado uma inversão do efeito de compatibilidade, sendo as respostas manuais mais rápidas quando pressionadas do lado oposto ao aparecimento do estímulo representando o time rival. Tais resultados foram interpretados como uma evidência de que as respostas aos times favorito e rival eram mediadas por mecanismos de aproximação e afastamento, respectivamente.

Estudos adicionais (Conde et al., 2014; Oliveira et al, 2021; Proctor, 2013) demonstraram que também existem diferenças temporais entre os dois blocos de prática. Mais especificamente, no bloco em que se responde ipsilateralmente às imagens do time preferido e contralateralmente às do time rival, as respostas são mais rápidas do que as respostas ao pareamento oposto (condição incompatível para o time preferido e resposta compatível para o time rival).

Oliveira et al. (2021) adaptaram o protocolo para verificar se os efeitos emocionais desencadeados pelos estímulos de futebol também são capazes de influenciar os padrões de resposta em outro teste atencional, conhecido como tarefa de Simon. Na tarefa de Simon, os participantes precisam selecionar a resposta correta, o mais rápido possível, com base no processamento de um atributo intrínseco ao estímulo (como forma ou cor). Mesmo que a localização do estímulo não seja considerada para seleção da resposta, os códigos espaciais parecem requerer processamento automático, chegando a afetar as respostas motoras. Neste sentido, são observadas respostas mais rápidas na condição espacialmente compatível, em comparação à incompatível. Essa diferença temporal entre as duas condições é denominada efeito Simon. No estudo de Oliveira et al. (2021), fora demonstrado que o efeito Simon varia em função da preferência por times de futebol, sendo maior para o time favorito. Os autores deste trabalho interpretaram os resultados da pesquisa indicando que as valências dos estímulos positivos e negativos provocam facilitações e/ou inibições nas respostas motoras. Também estimaram que o efeito ampliado para o time favorito poderia ser um indicador que a valência afetiva do estímulo facilita a resposta espacialmente correspondente ao time favorito e as respostas contralaterais ao time rival.

Apesar dos estudos supracitados terem oferecido importantes indícios sobre como imagens específicas de futebol podem influenciar o afeto, a cognição e o comportamento de torcedores, outras variáveis precisam de maior compreensão neste contexto, como o fanatismo, por exemplo. Embora existam diferentes perspectivas teóricas e filosóficas sobre o fanatismo (Battaly, 2023; Cassam, 2023; Katsafanas, 2024), este construto tem sido amplamente compreendido como fenômeno psicossocial disfuncional, caracterizado por um envolvimento intenso e devocional a ideologias, instituições, doutrinas, objetos, e/ou até mesmo a outras pessoas (como ídolos ou mártires), que os representem ou que possuam valores/ideais compartilhados (Tietjen, 2023a). Atualmente, o estudo do fanatismo apresenta grande relevância social por este fenômeno ter sido implicado com coercitividade, comportamentos violentos e hostis e até mesmo, com guerras e extremismo, nos mais variados contextos (Tietjen, 2023b).

Especificamente no contexto dos esportes, o fanatismo também tem sido amplamente associado a episódios de agressão, hostilidade, violência generalizada, assassinatos e desordem pública (Bandeira & Ramos, 2020; Conde & Coriolano, 2019; Coriolano & Conde, 2017; Louis, 2023; Zeferino et al., 2021). Diante de inúmeras lacunas ainda existentes para compreensão plena deste fenômeno, o presente estudo se configurou com o objetivo de investigar como a visualização de imagens de times de futebol, com valência afetiva antagônica (favorito e rival) podem influenciar indicadores emocionais. O desenho de pesquisa adotado também se delineou de modo a investigar se os diferentes níveis de fanatismo são capazes de influenciar a pontuação atribuída às dimensões de valência (seja de prazer ou desprazer) e ativação emocional (alertante ou relaxantes), diante imagens apresentadas.

Método

A presente pesquisa pode ser caracterizada como uma abordagem quase experimental, delineada com o controle de variável independente e adotando procedimentos validados para investigar parâmetros emocionais decorrentes da visualização de imagens do time favorito e do time rival. O estudo utilizou como variáveis dependentes, as medidas de valência hedônica e ativação emocional, atribuídas a diferentes categorias de imagens. Adotando uma perspectiva comparativa, foram considerados dois níveis de fanatismo, como variável categórica intergrupos, permitindo a análise das diferenças entre torcedores classificados em alto e baixo fanatismo. As variáveis intragrupos foram estabelecidas em 5 categorias de imagens que englobaram não apenas os times favorito e rival, mas também estímulos do Sistema Internacional de Figuras Afetivas Positivas, Negativas e Neutras, proporcionando parâmetros importantes de valência e ativação na comparação com as imagens experimentais.

Participantes

Participaram deste estudo 27 pessoas, sendo 22 mulheres e 5 homens, (M idade = 22 anos, DP = 3,25). O estudo foi divulgado em redes sociais e através de panfletos dispostos em áreas públicas do Instituto de Ciências da Sociedade e Desenvolvimento Regional (Universidade Federal Fluminense), em Campos dos Goytacazes (Rio de Janeiro, Brasil). As pessoas também foram convidadas presencialmente durante o intervalo das aulas e enquanto transitavam pelo Instituto, caracterizando uma amostragem por conveniência que foi composta por discentes de diferentes períodos e cursos de graduação, bem como prestadores de serviço e servidores do quadro técnico da Universidade. Para as análises, os participantes foram divididos em dois grupos distintos conforme os níveis de fanatismo verificados na escala de Fanatismo de Torcedores de Futebol. Mais especificamente, o grupo de alto fanatismo ficou composto por 13 pessoas (10 mulheres, 3 homens) e o grupo de baixo fanatismo por 14 pessoas (12 mulheres, 2 homens). Os voluntários não receberam remuneração ou vantagem em conceitos acadêmicos pela sua participação. Todos assinaram o Termo de Consentimento Livre e Esclarecido (TCLE). A pesquisa foi aprovada pelo Comitê de ética e Pesquisa da Universidade Federal de Pernambuco (Parecer No 2.140.159).

Instrumentos

Escala de Fanatismo de Torcedores de Futebol (EFTF). O instrumento permite avaliar o nível de fanatismo em torcedores de futebol (Wachelke et al., 2008). Os 11 itens da escala avaliam comportamentos, crenças e situações que podem refletir como a pessoa torce pelo seu time de futebol. O instrumento demonstrou indicadores psicométricos aceitáveis em estudo sobre validade fatorial e consistência interna no Brasil (Wachelke et al., 2008), como KMO = 0,94, teste de esfericidade de Bartlett significativo (𝑝 < 0,001), eigenvalue = 6,14 e alfa de Cronbach (α = 0,91). A escala unidimensional apresenta formato tipo Likert com 7 pontos, variando entre 1 (discordo fortemente) a 7 (concordo fortemente).

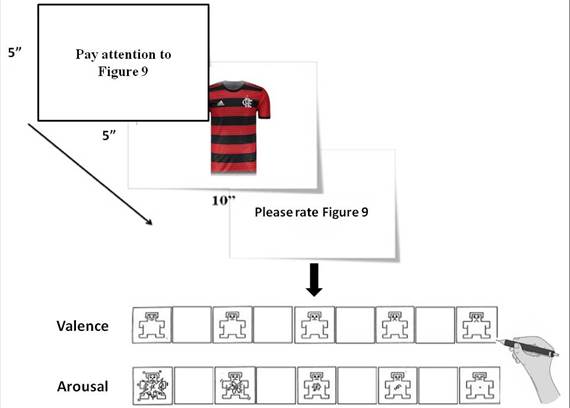

Escala Self Asessement Manekins (SAM). O instrumento utiliza uma perspectiva pictográfica não verbal de fácil e rápida aplicação para avaliar imagens com conteúdo emocional (Bradley & Lang, 1994; Bynion & Feldner, 2020). Com o uso deste instrumento, é possível obter informações sobre duas dimensões emocionais: valência e ativação. A primeira dimensão mede o grau de agradabilidade da figura apresentada, enquanto a segunda indica o nível de alerta, ativação ou excitação emocional, vivenciada pelo voluntário ao observar a imagem apresentada. Na escala, o participante deve assinalar o quanto uma imagem é positiva ou negativa (valência emocional) e qual o nível de excitação psicofisiológica (ativação emocional) desencadeado pela observação das figuras. Para isso, são apresentados manequins organizados horizontalmente, que servem como indicadores gráficos dos estados emocionais, com 9 níveis de respostas (Figura 1). Seguindo as normas para avaliação do IAPS no Brasil (Lasaitis et al., 2008), cada voluntário recebeu um caderno de instruções para classificar as imagens e também recebeu uma caneta para preenchimento. Os participantes devem ser informados que também podem utilizar os espaços entre os manequins e que estes representam opções intermediárias. Desta maneira, os participantes respondem classificando as imagens apresentadas através do SAM, assinalando um X nos cinco manequins ou entre dois destes manequins.

Sistema Internacional de Figuras Afetivas (IAPS) e estímulos experimentais. O banco de imagens utilizado para avaliação foi composto, de forma balanceada, por imagens positivas, negativas e neutras do IAPS. O IAPS é um banco de dados contendo 960 imagens, divididas em 16 conjuntos de 60 itens (Branco et al., 2023). Estas centenas de fotografias possuem alta resolução e representam vários aspectos da vida real (esportes, moda, paisagens, violência etc.) (Lang et al., 2005). Muitos estudos já demonstraram que as imagens do IAPS são capazes de induzir uma gama de estados emocionais que podem ser facilmente apresentados no contexto experimental do laboratório. O presente estudo utilizou 60 imagens do IAPS, sendo sorteadas 15 imagens negativas, igualmente distribuídas entre as subcategorias de mutilação, animais peçonhentos e violência; 15 imagens positivas, igualmente distribuídas entre eróticas, esportivas e relacionamento familiar com bebês; e 30 imagens neutras, igualmente distribuídas entre objetos domésticos, artes abstratas e faces indiferentes. Além das imagens do IAPS, cada bloco de avaliação possuía 30 imagens experimentais pareadas, compostas por 15 do time favorito e 15 do time rival. Foram utilizadas imagens dos quatro principais times de futebol do Rio de Janeiro (Fluminense, Flamengo, Vasco da Gama e Botafogo). As imagens experimentais foram criteriosamente selecionadas da internet considerando a demanda pelo pareamento contextual, das cores de fundo, situacional e simbólico para ambos os times. Logo, as imagens de cada time englobaram, de forma balanceada, as categorias bandeira, mascote, torcida, uniforme, objetos com símbolos dos times e jogadores populares.

Procedimentos

Logo após a assinatura do TCLE, os participantes preencheram um documento com seus dados pessoais, onde foram coletados dados como data de nascimento, identidade de gênero, escolaridade, informações sobre patologias diagnosticadas por médico, uso de drogas e/ou de medicamentos com ação psicotrópica, sobre possíveis alterações oftalmológicas e se ocorre uso de óculos para correção.

Após o preenchimento de informações sociodemográficas, os participantes foram convidados a responderem a EFTF (Wachelke et al., 2008). Os participantes também foram solicitados a realizarem a classificação, em ordem de preferência, dos quatro principais times de futebol do Rio de Janeiro (Fluminense, Flamengo, Vasco da Gama e Botafogo). Este procedimento foi usado para seleção dos estímulos visuais a serem utilizados como condições experimentais, considerando o primeiro e o quarto time como os times preferido e rival, especificamente.

Logo a seguir, as pessoas foram encaminhadas a uma sala com temperatura controlada e iluminação adequada para assistirem a um vídeo com instruções para participação no experimento sendo, logo depois, direcionados para avaliação das figuras e preenchimento do SAM. O vídeo informativo conteve instruções e exemplos sobre como responder a escala SAM, para cada dimensão estudada (valência e ativação). Os participantes também foram instruídos para marcar apenas uma dentre as 9 respostas possíveis para cada figura, em cada uma das dimensões estudadas, começando pela valência e em seguida, ativação. Os participantes também foram orientados a olharem atentamente para as imagens que fossem apresentadas durante todo o tempo em que elas estivessem na tela e que, apenas depois, deveriam marcar suas respostas na escala SAM, indicando como classificariam e como haviam se sentido ao visualizar a imagem anterior. Também tiveram orientações para não falar durante a pesquisa, não copiar respostas de outros voluntários, e foram solicitados a desligarem seus aparelhos eletrônicos.

A seguir, a avaliação começou com a apresentação de um slide que mostrava o número da imagem e informava que esta seria apresentada por 5 segundos. Em seguida, a imagem a ser avaliada era projetada na tela por mais 5 segundos e posteriormente, nenhum slide era projetado por 10 segundos, tempo destinado então para classificação da imagem visualizada nas dimensões estudadas, primeiramente a dimensão valência e posteriormente a ativação (Figura1). Os participantes foram instruídos para avaliar a valência afetiva de cada imagem, considerando que a extremidade esquerda do caderno de respostas, representava a valência positiva máxima (agradável) e na extremidade direita, a valência negativa máxima (desagradável). E para avaliar a ativação, devia-se considerar a extremidade à esquerda como nível máximo de ativação e à direita, o nível mínimo de ativação.

Figura 1: Procedimento de avaliação da imagem nas dimensões de valência e ativação emocional

Nota: Figura ilustrativa. Os espaços em branco na escala SAM também podem ser utilizados, caracterizando 9 níveis possíveis para resposta.

Análise estatística

As respostas obtidas na avaliação de cada imagem (categorias positiva, negativa e neutra do IAPS, bem como imagens experimentais do time favorito e do time rival) foram tabuladas e organizadas para cálculo da média e desvio padrão dos valores atribuídos às duas dimensões mensuradas pelo SAM (ativação e valência emocional). O nível de fanatismo foi estimado através da pontuação obtida na EFTF. Para definir os dois grupos com níveis distintos de fanatismo (alto e baixo) como variável categórica, foi estabelecida a mediana da pontuação obtida na EFTF como ponto de corte. Tal modelo para definição de grupos de fanatismo distintos através da EFTF segue protocolos já adotados anteriormente (Conde et al., 2018; Coriolano & Conde, 2017).

A seguir, os dados foram analisados através de uma análise de variância (ANOVA) com medidas repetidas utilizando o software Statistica® (StatSoft, versão 6.0). O delineamento da ANOVA teve como variável intergrupo o nível de fanatismo (alto e baixo fanatismo) e como intragrupo, as categorias de imagem: (a) do time favorito; (b) do time rival; (c) imagens com valência emocional negativas do IAPS; (d) imagens com valência emocional neutra do IAPS; (e) imagem com valência emocional positiva do IAPS.

Comparações planejadas por contraste foram utilizadas como análises adicionais para minimizar os riscos de erro tipo I na investigação das hipóteses previamente formuladas e também para permitir análises específicas comparando as variáveis de interesse de forma isolada. O valor de significância para as comparações entre os grupos foi estabelecido em p ≤ 0,05. O eta quadrado (n2) foi utilizado para estimar o tamanho do efeito indicado pela ANOVA e o d de Cohen nas comparações planejadas.

Por fim, uma análise de dispersão foi realizada com o objetivo de examinar a disposição dos dados nas dimensões de valência e ativação emocional. Os dados foram organizados de forma a representar a valência hedónica no eixo Y e a ativação emocional no eixo X. Para cada categoria de imagens experimentais, foi ajustada uma linha de regressão linear, de modo a verificar a presença do padrão descrito na literatura como "padrão bumerangue" (Branco et al., 2023; Lemos et al., 2024). Esse padrão é caracterizado pela disposição dos dados em duas direções opostas, refletindo a distribuição não linear entre valência e ativação (Versace et al., 2023). O padrão bumerangue é comumente observado em análises de dispersão com as figuras do IAPS, uma vez que imagens de valência positiva e negativa estão associadas a altos níveis de ativação, enquanto aquelas com valência neutra tendem a apresentar baixos níveis de ativação (Branco et al., 2023; Lemos et al., 2024). Assim, este modelo de análise define um espaço afetivo bidimensional no plano cartesiano, que captura padrões motivacionais organizados em dois ramos principais da distribuição. A partir desse modelo, evidências comportamentais e psicofisiológicas têm permitido identificar e validar quais imagens são capazes de evocar os sistemas motivacionais apetitivo e aversivo, correspondentes às duas hastes do padrão bumerangue (Bradley et al., 2001; Branco et al., 2023; Lemos et al., 2024; Versace et al., 2023).

Resultados

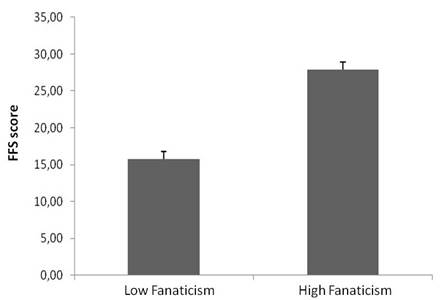

Com os dados da EFTF organizados de forma crescente, foi possível adotar a mediana como ponto de corte para distinção entre os grupos de alto (pontuação média de 27,93, DP = 9,80) e baixo fanatismo (M = 15,77, DP = 3,03), sendo seus escores estatisticamente diferentes entre si (p < 0,001; d = 1,67) (Figura 2).

|

Figura 2: Média dos grupos de alto e baixo fanatismo, considerando a pontuação na escala EFTF

Nota: Barras representam o desvio padrão.

Análise de valência

A ANOVA revelou um efeito significativo para a variável “Imagens” indicando que as categorias (time favorito; time rival; imagens positivas, neutras e negativas do IAPS) distinguiram entre si (F4,104=4,127; p < 0,001; η2=0,746) independentemente do nível de fanatismo. Comparações planejadas adicionais indicaram diferenças significativas para a dimensão entre todas as categorias de imagens, exceto entre as imagens neutras do IAPS e do time rival (p = 0,08; d = 0,34). Os valores obtidos em cada comparação estão especificados na Tabela 1.

Tabela 1: Comparação da valência hedônica entre as diferentes categorias de imagen

Nota: A tabela apresenta média (M) e desvio padrão (DP) das diferentes categorias de imagens, bem como os resultados das comparações estatísticas (p) e tamanhos de efeito (d), * identifica as diferenças estatisticamente significativas.

A ANOVA não apresentou interações significativas entre o nível de fanatismo e as categorias de imagens (F4,104=0,315; p < 0,867; η2=0,003), indicando que a valência atribuída as imagens não variaram em função do nível de fanatismo. Análises planejadas adicionais confirmaram a ausência de diferenças significativas entre os dois grupos (Tabela 2).

Tabela 2: Comparação das valências atribuídas entre as diferentes categorias de imagens

Nota: A tabela apresenta média (M) e desvio padrão (DP) das diferentes categorias de imagens, bem como os resultados das comparações estatísticas (p) e tamanhos de efeito (d) nas comparações entre os grupos de baixo e alto fanatismo.

Análise da ativação

Na análise da ativação emocional, a ANOVA apresentou um efeito significativo para a variável “Imagens” ao revelar que as diferentes categorias (time favorito; time rival; imagens positivas, neutras e negativas do IAPS) distinguiram entre si (F4,104= 27,12; p < 0,01; η2=0,303) quanto à ativação emocional. Comparações planejadas adicionais demonstraram que tais diferenças ocorreram na maioria das comparações, exceto entre imagens do time rival e figuras Neutras do IAPS (p = 0,29; d = 1,84). Os resultados detalhados podem ser observados na Tabela 3.

Tabela 3. Comparação do nível de ativação atribuído às Imagens entre as diferentes categorias de imagens

Nota: A tabela apresenta média (M) e desvio padrão (DP) das diferentes categorias de imagens, bem como os resultados das comparações estatísticas (p) e tamanhos de efeito (d), * identifica as diferenças estatisticamente significativas.

Embora não tenha sido verificada nenhuma interação do nível de fanatismo com a ativação emocional atribuída às categorias de imagem (F4,104=1,92; p = 0,113; η2=0,021), comparações planejadas por contraste revelaram padrões distintos em comparações específicas dentro e entre grupos de alto e baixo fanatismo. Ao analisar os resultados obtidos nas comparações dentro dos grupos, isolando o fator Fanatismo, observou-se que os dois grupos demonstraram que imagens positivas não diferem das negativas quanto à excitação emocional. Tal padrão também fora verificado entre imagens neutras e do time rival. Ainda em ambos os grupos, foi possível identificar que, tanto as imagens positivas quanto as negativas, apresentaram maior ativação quando comparadas às imagens neutras.

Contudo, diferenças importantes também foram identificadas analisando os padrões de resposta dentro dos grupos. De forma mais detalhada, observou-se que, apenas no grupo de alto fanatismo, a excitação emocional desencadeada pelo time favorito se equipara a de figuras positivas e negativas do IAPS, bem como à excitação elicitada por imagens do time rival (Tabela 4).

Tabela 4: Comparação do nível de ativação às diferentes categorias de imagens entre os Grupos de Baixo e Alto Fanatismo

Nota: A tabela apresenta média (M) e desvio padrão (DP) das diferentes categorias de imagens, bem como os resultados das comparações estatísticas (p) e tamanhos de efeito (d) isolando os grupos de alto e baixo fanatismo. * identifica as diferenças estatisticamente significativas.

As análises planejadas também revelaram a existência de diferenças significativas entre os grupos quanto aos níveis de ativação emocional. Mais especificamente, o grupo com alto fanatismo apresentou níveis de ativação superiores às imagens neutras (p < 0,01; d = 0,914), em comparação ao grupo de baixo fanatismo. Também foram encontrados maiores valores de ativação emocional para o grupo de alto fanatismo frente às imagens de ambos os times, rival (p < 0,01; d = 0,83) e favorito (p < 0,01; d = 1,49). As demais comparações entre grupos não demonstraram significância estatística.

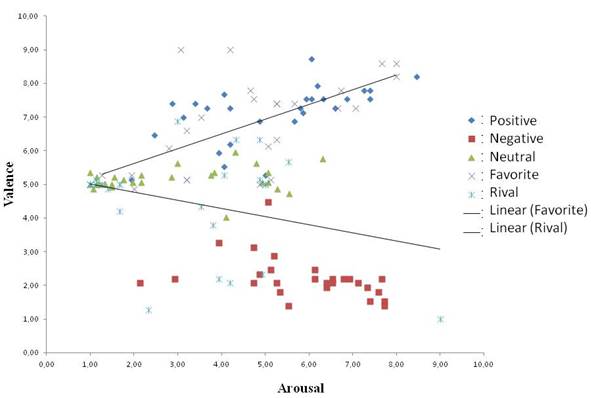

Por fim, a análise de dispersão com a aplicação da regressão linear apresentou um padrão consistente com a teoria dos vetores motivacionais (Figura 3). Esta teoria sugere que as imagens relacionadas ao time favorito seguem um padrão de dispersão semelhante ao dos estímulos altamente apetitivos, enquanto as imagens do time rival se assemelham ao padrão das imagens negativas. O padrão bumerangue foi identificado por meio de uma inspeção visual do gráfico de dispersão, que foi estabelecido com base na valência e ativação das imagens do IAPS.

Figura 3: Dispersão da valência em função da ativação para as diferentes categorias de imagens

Nota: As linhas de tendência representam a regressão linear para os dados atribuídos ao time favorito (acima) e rival (abaixo), independentemente do nível de fanatismo.

Discussão

As emoções são elementos fundamentais para a compreensão dos fenômenos esportivos e dos seus impactos na nossa sociedade. Os processos emocionais não influenciam apenas os atletas e equipes, mas também têm um efeito considerável sobre torcedores e entusiastas (Furley et al., 2023). O contexto da competição parece facilitar a manifestação catártica de emoções intensas e coletivas, obviamente moduladas pela representação simbólica da vitória, da derrota, pela identificação com o time favorito e aversão ao rival. Logo, entender as variáveis psicológicas implicadas com fenômenos psicossociais como o fanatismo, a mobilização em massa e o comportamento de manada nos grandes eventos desportivos se torna um desafio importante para ciências humanas e sociais.

Diante de variadas condições emocionais elicitadas ao torcer por um time, a valência atribuída por torcedores (positiva ou negativa) parece ter implicação com o envolvimento harmonioso ou obsessivo com seu time (Schellenberg et al., 2024). Tais aspectos podem auxiliar na compreensão do comportamento emocional, tanto de celebração quanto de hostilidade entre torcedores (Furley et al., 2023; Schellenberg et al., 2024).

Alguns estudos propõem que a classificação da valência no SAM pode refletir a ativação de sistemas motivacionais básicos, seja de recompensa ou de aversão (Bradley et al., 2001; Versace et al., 2023). Tal modelo se ampara na compreensão de que o comportamento emocional envolve esses dois subsistemas motivacionais básicos (Bradley et al., 2001; Lemos et al., 2014). No presente estudo, as medidas obtidas para valência afetiva nas figuras referências do IAPS, demonstraram padrão compatível com a literatura (Bradley et al., 2001; Branco et al., 2023), tendo sido as imagens positivas avaliadas como agradáveis, neutras e as negativas como desagradáveis, com diferenças significativas entre estas categorias. As figuras do IAPS serviram como referências essenciais para melhor contextualização acerca dos valores indicados para as imagens experimentais dos times favorito e rival. Fora verificado que as imagens do time favorito se destacaram por apresentarem alto índice de agradabilidade, enquanto as imagens do time rival foram avaliadas como desagradáveis.

Modelos de estudo na perspectiva dimensional das emoções consideram que as medidas de excitação emocional complementam indicadores de valência afetiva por representarem o nível de ativação motivacional (Bradley et al., 2001; Branco et al., 2023). Considerando essas duas dimensões emocionais, valência e ativação, seria possível a representação gráfica em plano cartesiano dos vetores motivacionais, variando em intensidade (Lemos et al., 2024; Versace et al., 2023). Os resultados aqui reportados demonstraram o padrão esperado para as imagens padronizadas do IAPS, com altos índices de ativação emocional para as figuras positivas e negativas, em comparação com as neutras (Bradley et al., 2001; Branco et al., 2023; Lemos et al., 2024; Versace et al., 2023). As imagens negativas do IAPS foram emocionalmente ainda mais alertantes do que as positivas. Quanto às imagens experimentais, ainda sem considerar o nível de fanatismo, observou-se que as imagens do time favorito despertaram menor ativação do que as imagens positivas e negativas do IAPS e maior ativação do que as imagens neutras e do time rival. Enquanto as imagens do time rival demonstraram um padrão de ativação semelhante às imagens neutras, sendo menos excitante do que todas as outras categorias.

Contudo, considerando as influências do nível de fanatismo, foram identificados padrões distintos de excitação emocional entre os dois grupos. Mais especificamente, o fato do grupo de alto fanatismo ter apresentado níveis maiores de ativação emocional decorrentes da observação de imagens neutras e das imagens experimentais, seja do time rival ou favorito, pode ser interpretado como uma evidência de que este grupo talvez esteja mais propenso à excitação emocional e/ou tenha menor capacidade de regulação emocional.

Muitas pesquisas têm indicado que estímulos visuais com componentes emocionais ou afetivos podem desencadear aumento significativo da atividade cerebral em circuitos visuais, emocionais e motores (Bradley et al., 2001; Carretié et al., 2022; Lin et al., 2020; Onigata & Bunno, 2020; Pereira et al., 2010; Zsidó, 2024). Nesta linha de raciocínio, os resultados obtidos suscitam a reflexão sobre a possibilidade destes circuitos primitivos, apetitivos e aversivos, atuarem mediando a interação de torcedores com estímulos representando o time favorito e o time rival, respectivamente. Afinal, pode-se observar a ocorrência do padrão bumerangue na análise de dispersão, sendo possível verificar que a linha de tendência estabelecida pela regressão linear para os valores de ativação e valência ao time favorito se estabelece na parte superior do gráfico, na mesma direção dos parâmetros de vetores motivacionais estabelecidos para o sistema apetitivo. Enquanto a linha de regressão linear verificada para as imagens do time rival, se delineou em um vetor motivacional compatível com parâmetros observados para sistema motivacional aversivo. Importante enfatizar que o padrão Bumerangue fica ainda mais definido para torcedores com maiores níveis de fanatismo, devido aos níveis mais altos atribuídos à ativação emocional para as imagens dos times favorito e rival.

Os resultados obtidos nas análises do nível de fanatismo, junto com indicadores de reação emocional às imagens de times favoritos e rivais, reforçam a compreensão de que as pessoas mais fanáticas estão mais propensas à excitação emocional. Na tentativa de compreender as implicações práticas deste estudo, convém considerar evidências complementares que demonstram que o aumento da atividade nos circuitos emocionais compete por recursos de processamento com redes neurais responsáveis pela cognição e comportamentos ditos racionais (Dolcos & Mccarthy, 2006). Tal condição pode ser propícia para desencadear o contágio emocional e o comportamento de manada, ambos fenômenos muito presentes no contexto do esporte competitivo (Neuman, 2024).

Adicionalmente, devemos considerar que imagens dos times favorito e rival ativam regiões límbicas, filogeneticamente antigas, estabelecidas como moduladoras do comportamento afetivo e motivacional e ainda, que o fanatismo se correlaciona positivamente com a ativação desses circuitos (Duarte et al., 2017). Apesar de algumas evidências terem sugerido que a interação com estímulos visuais representando o time favorito e rival recrutam respectivamente os sistemas motivacionais apetitivo e aversivo (Conde et al., 2011; Conde et al., 2018; Oliveira et al., 2021), até o momento tal compreensão não é consensual (Proctor, 2013; Yamaguchi & Chen, 2019). Neste sentido, a caracterização dos vetores motivacionais para as imagens do time favorito e rival no presente estudo serve como mais uma evidência que indica o envolvimento dos sistemas apetitivo e aversivo diante do processamento de estímulos de times de futebol.

Embora a presente investigação propicie contribuições relevantes, é importante analisar cuidadosamente os resultados aqui apresentados, considerando algumas limitações do estudo. Como primeira e principal limitação, deve-se destacar que a amostra foi composta por conveniência, resultando na predominância de mulheres em ambos os grupos. Embora a adoção da mediana para a formação dos grupos de alto e baixo fanatismo encontre algum respaldo na literatura (Conde et al., 2018; Coriolano & Conde, 2017), tal procedimento dificultou a distribuição igualitária de gêneros em cada grupo, o que refletiu em um desequilíbrio ainda mais acentuado no grupo de baixo fanatismo. Embora o delineamento amostral ideal não tenha sido implementado, tal condição não compromete os resultados aqui reportados, uma vez que os objetivos da pesquisa se estabeleceram justamente na comparação de diferentes perfis de fanatismo e não na comparação entre gêneros. Adicionalmente, o estudo de Zeferino et al. (2021) não identificou diferenças entre gêneros quanto ao nível de fanatismo e agressividade em um estudo que avaliou 210 torcedores com a EFTF e com a escala de Agressividade (Buss & Perry, 1992). Ainda assim, se faz importante reconhecer que novos estudos são fundamentais para melhor compreensão das diferenças entre os gêneros quanto aos construtos aqui mensurados, principalmente sobre a atribuição da valência hedônica e ativação emocional diante de imagens de futebol do time favorito e rival. Por fim, o presente estudo também não investigou possíveis efeitos moduladores decorrentes de outras variáveis sociodemográficas, tais como filiação à torcida organizada e idade, as quais também parecem interferir significativamente no comportamento de torcedores (Zeferino et al., 2021).

Conclusões

A torcida tem sido considerada como uma variável importante à sustentação da cultura e da economia do futebol. Grupos conhecidos como “torcidas organizadas” foram historicamente instaurados no Brasil por torcedores com o objetivo de criar e desenvolver laços, comemorar além de fortalecer sentimentos de rivalidade e oposição. Contudo, alguns destes torcedores são apontados, por parte da literatura, como mais propensos a se envolverem em episódios de violência no futebol brasileiro (Louis, 2023; Ribeiro & Fernandes, 2021). Neste contexto, ressalta-se que os impactos do fanatismo por futebol possuem implicações de cunho socioeconômico, à mobilidade urbana, causando impactos na área de segurança pública e em processos psicossociais. Além disso, segundo Brandão et al. (2020), a violência nos estádios se estabelece como fenômeno complexo e multivariado.

Os resultados da pesquisa oferecem uma compreensão pioneira sobre o fanatismo e suas implicações emocionais, sendo os principais achados caracterizados pela identificação de diferenças significativas nos níveis de ativação emocional entre torcedores de alto e baixo fanatismo. Pela primeira vez, fora verificado de que forma imagens de times de futebol, com valência afetiva antagônica, são percebidas por seus torcedores e rivais, principalmente no que se refere à agradabilidade (dimensão da valência) e ativação emocional. Adicionalmente, foram verificados padrões motivacionais que suscitam o envolvimento dos sistemas motivacionais apetitivo e aversivo, em consequência da simples observação de imagens representando o time favorito e o principal rival, respectivamente. Tal verificação garante suporte para melhor entendimento sobre os motivos das competições mobilizarem milhares de pessoas, além de movimentarem elevados valores financeiros (Oliveira et al., 2021). Complementariamente, considerar o envolvimento do sistema emocional aversivo em resposta à representação do time rival parece uma possibilidade plausível para compreender a hostilidade e rivalidade entre times favoritos e rivais.

Tendo em vista os fatos supracitados, o presente estudo sugere que as abordagens de seguridade em jogos de futebol considerem também os processos psicossociais e singularidades da expressão emocional do torcedor na relação que estabelece com o seu time e com seus principais rivais. Neste sentido, observa-se a demanda por novos modelos de planejamento e também pela implementação de políticas públicas para a segurança de torcedores nos estádios de futebol e transeuntes nos arredores das partidas, considerando que as medidas mais adotadas têm se restringido a ações de inteligência policial somadas ao policiamento ostensivo como prevenção durante os jogos (Barbosa & Bueno, 2023; Rodrigues & Santos, 2024). A aplicação da força policial também tem sido verificada em situações de conflitos entre torcedores. Ainda que não existam modelos interventivos validados com efetividade comprovada em condições de conduta agressiva de torcedores, a obra de Neuman (2024) proporciona reflexões e ideias inovadoras que inspiram abordagens comportamentais alternativas para se compreender e lidar com dinâmicas das multidões. Essa abordagem alternativa à policial, talvez possa permitir estratégias mais eficazes de prevenção e gestão de comportamentos violentos. Vislumbra-se, com parcimônia, que através de campanhas psicoeducativas seja possível conscientizar torcedores sobre como o fanatismo se manifesta em suas vidas, tratando de suas implicações emocionais, comportamentais e consequências às interações sociais, bem como para auxiliá-los a desenvolver reações emocionais mais funcionais e comportamentos não violentos nos ambientes esportivos como propõe alguns trabalhos (Galily et al., 2024; Neuman, 2024; Newson et al., 2023). Seria também importante considerar abordagens mais humanizadas, considerando procedimentos como avaliação e atendimento psicológico àqueles que se envolvem em episódios de violência, uma vez que simples estímulos visuais, seja de imagens neutras ou, principalmente, do time rival, parecem capazes de desencadear ativação emocional mais alta em torcedores mais fanáticos. Tal proposição se ampara no fato que a violência entre torcedores não acontece apenas dentro dos estádios, mas também em praças públicas, metrôs, ruas movimentadas, entre muitos outros locais públicos. Por ser um tema multifacetado, novas pesquisas, em perspectiva multidisciplinar, talvez possam ajudar a compreender e complementar o conhecimento que se tem sobre o fanatismo por futebol e suas implicações psicossociais. Os resultados do presente estudo contribuem para ampliar a compreensão sobre como o fanatismo pode influenciar na maneira pela qual se percebe os estímulos emocionais provenientes do contexto do futebol, representando a polaridade afetiva favorito-rival, inerente aos embates esportivos.

Referências:

Bandeira, V. F., & Ramos, D. G. (2020). Aspectos sociodemográficos relacionados à agressividade e ao fanatismo em uma torcida de futebol. Psicologia Revista, 29(1), 246-272. https://doi.org/10.23925/2594-3871.2020v29i1p246-272

Barbosa, D. S., & Bueno, V. L. A. (2023). Inteligência da Polícia Militar do Paraná como ferramenta na diminuição de confrontos violentos entre torcidas organizadas de futebol em estádios paranaenses. Brazilian Journal of Development, 9(1), 4973-4988. https://doi.org/10.34117/bjdv9n1-341

Battaly, H. (2023). Can fanaticism be a liberatory virtue? Synthese, 201(6), 1-27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-023-04174-7

Bradley, M., & Lang, P. (1994). Measuring emotion: The self-assessment manikin and the semantic differential. Journal of Behavioral Therapy and Experimental Psychiatry, 25, 49-59. https://doi.org/10.1016/0005-7916(94)90063-9

Bradley, M., Codispoti, Cuthbert B., & Lang(2001). Emotion and motivation I: defensive and appetitive reactions in picture processing. Emotion, 1, 276-298. https://doi.org/10.1037//1528-3542.1.3.276

Branco, D., Goncalves, O. F., & Badia, S. B. I. (2023). A systematic review of international affective picture system (IAPS) around the world. Sensors, 23(8), 3866. https://doi.org/10.3390/s23083866

Brandão, T., Murad, M., Belmot, R., & Dos Santos, R. (2020). Álcool e violência: Torcidas organizadas de futebol no brasil. Movimento, 26, e26001. https://doi.org/10.22456/1982-8918.90431

Buss, A. H., & Perry, M. (1992). The aggression questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(3), 452-459. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.3.452

Bynion, T. M., & Feldner, M. T. (2020). Self-assessment manikin. Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences, 4654-4656. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-24612-3_77

Carretié, L., Fernández-Folgueiras, U., Álvarez, F., Cipriani, G. A., Tapia, M., & Kessel, D. (2022). Fast unconscious processing of emotional stimuli in early stages of the visual cortex. Cerebral Cortex, 32(19), 4331-4344. https://doi.org/10.1093/cercor/bhab486

Cassam, Q. (2023). Fanaticism: for and against. Em L. Townsend, R. Tietjen, H. Schmid, & M. Staudigl (Eds.), The Philosophy of Fanaticism. Epistemic, Affective, and Political Dimensions (pp. 19-38). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003119371

Castro, C. O. (2014). Morte organizada: os bárbaros. O Globo.

Conde, E. F. Q., Cavallet, M., Torro-Alves, N., Matsushima, E. H., Fraga-Filho, R. S., Jazenko, F., Busatto, G. & Gawryszewski, L. G. (2014). Effects of affective valence on a mixed spatial correspondence task: A reply to Proctor (2013). Psychology & Neuroscience, 7(2), 83. https://doi.org/10.3922/j.psns.2014.021

Conde, E. F. Q., & Coriolano, A. M. (2019). O fanatismo no contexto do esporte. Em K. Rubio & J. Camilo (Orgs.), Psicologia social do esporte (pp. 169-182). Képos.

Conde, E. F. Q., Jazenko, F., Fraga Filho, R. S., Costa, D. H. D., Torro-Alves, N., Cavallet, M., & Gawryszewski, L. G. (2011). Stimulus affective valence reverses spatial compatibility effect. Psychology & Neuroscience, 4, 81-87. https://doi.org/10.3922/j.psns.2011.1.010

Conde, E. F. Q., Lucena, A. O. D. S., da Silva, R. M., Filgueiras, A., Lameira, A. P., Torro-Alves, N., Gawryszewski, L. G., & Machado-Pinheiro, W. (2018). Hemispheric specialization for processing soccer related pictures: The role of supporter fanaticism. Psychology & Neuroscience, 11(4), 329. https://doi.org/10.1037/pne0000147

Coriolano, A. M., & Conde, E. F. Q. (2017). Fanatismo e agressividade em torcedores de futebol. Revista Brasileira de Psicologia do Esporte, 6(2). https://doi.org/10.31501/rbpe.v6i2.7092

Dolcos, F., & Mccarthy, G. (2006). Brain Systems Mediating Cognitive Interference by Emotional Distraction. The Journal of Neuroscience, 26(7), 2072-2079. https://doi.org/10.1523/jneurosci.5042-05.2006

Duarte, I. C., Afonso, S., Jorge, H., Cayolla, R., Ferreira, C., & Castelo-Branco, M. (2017). Tribal love: the neural correlates of passionate engagement in football fans. Social Cognitive and Affective Neuroscience, 12(5), 718-728. https://doi.org/10.1093/scan/nsx003

Furley, P., Laborde, S., Robazza, C., & Lane, A. (2023). Emotions in sport. Em J. Schüler, M. Wegner, H. Plessner, & R. Eklund (Eds.), Sport and exercise psychology: theory and application (pp. 247-279). Springer International Publishing.

Galily, Y., Pack, S., & Tamir, I. (2024). Spectator sport and fan behavior: a sequel. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1414407. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1414407

Katsafanas, P. (2024). What’s so bad about fanaticism? Synthese, 203(6), 205. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11229-024-04647-3

Kelly, K. J., Murray, E., Barrios, V., Gorman, J., Ganis, G., & Keenan, J. P. (2009). The effect of deception on motor cortex excitability. Social Neuroscience, 4(6), 570-574. https://doi.org/10.1080/17470910802424445

Lang, B., Bradley, M., & Cuthbert, B. (2005). International affective picture system (IAPS): Digitized photographs, instruction manual and affective ratings (Technical report N0 A-6). University of Florida, Center for Research in Psychophysiology.

Lasaitis, C., Ribeiro, R. L., & Bueno, O. F. A. (2008). Brazilian norms for the International Affective Picture System (IAPS): comparison of the affective ratings for new stimuli between Brazilian and North-American subjects. Jornal Brasileiro de Psiquiatria, 57, 270-275. https://doi.org/10.1590/s0047-20852008000400008

Lemos, T. C., Silva, L. A., Gaspar, S. D., Coutinho, G. M., Stariolo, J. B., Oliveira, P. G., Conceição, L., Volchan, E., & David, I. A. (2024). Adaptation of the normative rating procedure for the International Affective Picture System to a remote format. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 37(1), 41. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41155-024-00326-x

Lin, H., Müller-Bardorff, M., Gathmann, B., Brieke, J., Mothes-Lasch, M., Bruchmann, M., Miltner, W. H. R. & Straube, T. (2020). Stimulus arousal drives amygdalar responses to emotional expressions across sensory modalities. Scientific Reports, 10(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-020-58839-1

Louis, S. (2023). Football fandom in France and Italy. Em B. Buarque de Hollanda & T. Busset (Eds.), Football Fandom in Europe and Latin America: Culture, Politics, and Violence in the 21st Century (pp. 59-80). Springer International Publishing.

Mulckhuyse, M. (2018). The influence of emotional stimuli on the oculomotor system: A review of the literature. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 18, 411-425. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13415-018-0590-8

Murad, M. (2017). A violência no futebol: novas pesquisas, novas ideias, novas propostas (Rev. ampliada). Selo Benvirá.

Neuman, Y. (2024). Betting Against the Crowd. Springer.

Newson, M., White, F., & Whitehouse, H. (2023). Does loving a group mean hating its rivals? Exploring the relationship between ingroup cohesion and outgroup hostility among soccer fans. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 21(4), 706-724. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197x.2022.2084140

Oliveira, L. F. D., Antunes, F. C. C. S., Jazenko, F., Conde, E. F. Q., Fraga-Filho, R. S., & Gawryszewski, L. (2021). Interaction between affective and spatial polarities: soccer preferences and stimulus-response compatibility. Psicologia em Pesquisa, 15(3), 1-17.

Onigata, C., & Bunno, Y. (2020). Unpleasant visual stimuli increase the excitability of spinal motor neurons. Somatosensory & Motor Research, 37(2), 59-62. https://doi.org/10.1080/08990220.2020.1724087

Park, H. J., Kim, J., Kim, S., Moon, D., Know, M. H., & Kim, W. (2009). Neural correlates of winning and losing while watching soccer matches. International Journal of Neuroscience, 119(1), 76-87. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207450802480069

Pereira, M., Oliveira, L., Erthal, F., Jofilly, M., Mocaiber, I., Volchan, E., & Pessoa, L. (2010). Emotion affects action: Midcingulate cortex as a pivotal node of interaction between negative emotion and motor signals. Cognitive And Affective Behavioral Neuroscience, 1(10), 94-106. https://doi.org/10.3758/CABN.10.1.94

Polo, E. M., Farabbi, A., Mollura, M., Mainardi, L., & Barbieri, R. (2024). Understanding the role of emotion in decision making process: using machine learning to analyze physiological responses to visual, auditory, and combined stimulation. Frontiers in Human Neuroscience, 17, 1286621. https://doi.org/10.3389/fnhum.2023.1286621

Proctor, R. W. (2013). Stimulus affect valence may influence mapping-rule selection but does not reverse the spatial compatibility effect: Reinterpretation of Conde et al. (2011). Psychology & Neuroscience, 6, 3-6. https://doi.org/10.3922/j.psns.2013.1.02

Ribeiro, M. J., & Fernandes, P. H. C. (2021). A violência no futebol brasileiro: da emoção no gol ao luto pelas vítimas. Revista GeoPantanal, 16(30), 245-257.

Rodrigues, J., & Dos Santos, C. P. (2024). Uma revisão de literatura acerca da inteligência da polícia militar no âmbito da violência das torcidas organizadas no futebol profissional. Revista Científica Multidisciplinar, 5(2), e514857. https://doi.org/10.47820/recima21.v5i2.4857

Schellenberg, B. J., Verner-Filion, J., & Gaudreau, P. (2024). How do passionate sport fans feel? An examination using a quadripartite approach. Motivation and Emotion, 48(5), 684-699. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11031-024-10087-w

Tietjen, R. R. (2023a). On the social constitution of fanatical feelings. Em L. Townsend, R. Tietjen, H. Schmid, & M. Staudigl (Eds.), The Philosophy of Fanaticism Epistemic, Affective, and Political Dimensions (pp. 111-129). Routledge.

Tietjen, R. R. (2023b). Fear, fanaticism, and fragile identities. The Journal of Ethics, 27(2), 211-230. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10892-023-09418-9

Versace, F., Sambuco, N., Deweese, M. M., & Cinciripini, P. M. (2023). Electrophysiological normative responses to emotional, neutral, and cigarette-related images. Psychophysiology, 60(3), e14196. https://doi.org/10.1111/psyp.14196

Wachelke, J., Andrade, A., Tavares, L., & Neves, J. (2008). Mensuração da identificação com times de futebol: evidências de validade fatorial e consistência interna de duas escalas. Arquivos Brasileiros de Psicologia, 60(1), 96-111.

Wann, D., & James, J. (2018). Sport fans: The psychology and social impact of fandom. Routledge.

Yamaguchi, M., & Chen, J. (2019). Affective influences without approach-avoidance actions: On the congruence between valence and stimulus-response mappings. Psychonomic Bulletin & Review, 26, 545-551. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13423-018-1547-1

Zeferino, G. G., Silva, M. A., & Alvarenga, M. A. S. (2021). Associations between sociodemographic and behavioural variables, fanaticism and aggressiveness of soccer fans. Ciencias Psicológicas, 15(2), e-2390. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v15i2.2390

Zsidó, A. N. (2024). The effect of emotional arousal on visual attentional performance: A systematic review. Psychological Research, 88(1), 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00426-023-01852-6

Disponibilidade de dados: O conjunto de dados que embasa os resultados deste estudo não está disponível.

Como citar: Kort-Kamp, M. L. I., Rocha Porto, T., Silveira de Oliveira, R., & Conde, E. F. (2024). Efeitos emocionais elicitados por imagens de futebol: Um estudo sobre o fanatismo. Ciencias Psicológicas, 18(2), e-3849. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v18i2.3849

Contribuição de autores (Taxonomia CRediT): 1. Conceitualização; 2. Curadoria de dados; 3. Análise formal; 4. Aquisição de financiamento; 5. Pesquisa; 6. Metodologia; 7. Administração do projeto; 8. Recursos; 9. Software; 10. Supervisão; 11. Validação; 12. Visualização; 13. Redação: esboço original; 14. Redação: revisão e edição.

M. L. I. K. K. contribuiu em 2, 3, 5, 6, 13; T. R. P. em 3, 13, 14; R. S. O. em 1, 2, 3, 5, 6, 9; E. F. C. em 1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14.

Editora científica responsável: Dra. Cecilia Cracco.

Ciencias Psicológicas; v18(2)

Julio-Diciembre 2024

10.22235/cp.v18i2.3849

Original Articles

Emotional effects elicited by football images: A study on fanaticism

Efeitos emocionais elicitados por imagens de futebol: Um estudo sobre o fanatismo

Efectos emocionales desencadenados por imágenes de fútbol: Un estudio sobre el fanatismo

Monick Leonora Inês Kort-Kamp1, ORCID 0000-0001-8019-6215

Thauan Rocha Porto2, ORCID 0000-0002-3360-5271

Roberdson Silveira de Oliveira3, ORCID 0000-0001-9142-8851

Erick Francisco Conde4, ORCID 0000-0002-7130-2888

1 Universidade Federal Fluminense, Brazil

2 Universidade Federal Fluminense, Brazil

3 Universidade Federal Fluminense, Brazil

4 Universidade Federal Fluminense, Brazil, [email protected]

Abstract:

The present study investigated the effects of the favorite and rival team visualization on valence and emotional arousal indicators, verifying for possible interactions with the fanaticism level in soccer fans. Twenty-seven volunteers (Mage = 22; SD = 3.25) participated in this experiment, who evaluated the pleasantness (hedonic valence) and the emotional arousal (activation) triggered by a set of neutral, positive and negative images of the International System of Affective Pictures (IAPS) plus 30 experimental images of the favorite and rival team. Evaluations were performed using the Self Assessment Manikin (SAM) scale and the Football Supporter Fanatism Scale (FSFS). Comparative analysis revealed that fanaticism did not influence the assignment of hedonic valence to the images. However, individuals with higher levels of fanaticism exhibited greater arousal in response to neutral (p < .01; d = 0.914), favorite (p < .01; d = 1.49), and rival images (p < .01; d = 0.83). The dispersion analysis suggested the involvement of appetitive and aversive motivational systems in response to images of the favorite and rival teams, respectively. The study findings lead to a better understanding of the fanaticism in soccer.

Keywords: fanaticism; soccer; affective valence; emotional arousal; sport psychology.

Resumo:

O presente estudo investigou os efeitos da visualização de imagens de times favoritos e rivais nos indicadores de valência e ativação emocional, averiguando possíveis interações com os níveis de fanatismo em torcedores de futebol. Participaram deste experimento 27 voluntários (M = 22 anos; DP = 3,25), que avaliaram a agradabilidade (valência hedônica) e a excitação emocional (ativação) desencadeada por um conjunto de imagens neutras, positivas e negativas do Sistema Internacional de Figuras Afetivas (IAPS), acrescido de 30 imagens experimentais pareadas, sendo 15 do time favorito e 15 do time rival. As avaliações foram realizadas através da escala Self Assessment Manikin (SAM) e da Escala de Fanatismo em Torcedores de Futebol (EFTF). Análises comparativas demonstraram que o nível de fanatismo não influenciou na atribuição da valência hedônica às imagens. Contudo, o grupo com níveis mais altos de fanatismo apresentou maior excitação emocional em resposta a imagens neutras (p < 0,01; d = 0,914), do time favorito (p < 0,01; d = 1,49) e do time rival (p < 0,01; d = 0,83). A análise de dispersão sugeriu o envolvimento dos sistemas motivacionais apetitivo e aversivo em reação às imagens do time favorito e rival, respectivamente. Os resultados do estudo auxiliam na compreensão do fenômeno do fanatismo no futebol.

Palavras-chave: f fanatismo; futebol; valência afetiva; ativação emocional; psicologia do esporte.

Resumen:

El presente estudio investigó los efectos de la visualización de imágenes de equipos favoritos y rivales en los indicadores de valencia y activación emocional para averiguar la interacción con los niveles de fanatismo de los hinchas de fútbol. Veintisiete voluntarios (M = 22 años; DE = 3.25) participaron en este experimento, quienes evaluaron la agradabilidad (valencia hedónica) y la excitación emocional (activación) desencadenada por un conjunto de imágenes neutrales, positivas y negativas del International System of Affective Pictures (IAPS), con más de 30 imágenes experimentales del equipo favorito y el rival. Las evaluaciones se realizaron utilizando la escala Self Assessment Manikin (SAM) y la Escala de Fanatismo en Hinchas de Fútbol (EFHF). Análisis comparativos demostraron que el nivel de fanatismo no influyó en la atribución de la valencia hedónica de las imágenes. Sin embargo, las personas con niveles más altos de fanatismo presentaron una excitación superior ante imágenes neutras (p < .01; d = 0.914), imágenes del equipo favorito (p < .01; d = 1.49) e imágenes del equipo rival (p < .01; d = 0.83). El análisis de dispersión sugirió la implicación de los sistemas motivacionales apetitivos y aversivos en respuesta a las imágenes del equipo favorito y rival, respectivamente. Los resultados del estudio ayudan a comprender el fanatismo en el fútbol.

Palabras clave: fanatismo; fútbol; valencia afectiva; excitación emocional; psicología del deporte.

Received: 22/01/2024

Accepted: 17/10/2024

Football is a globally popular sport, establishing itself as a transcultural phenomenon capable of generating significant impacts on our society (Wann & James, 2018). Beyond the economic dimension and other social impacts, conflicts between fans have required public policies in the areas of social security and urban mobility, with relevant socioeconomic implications (Louis, 2023). When it comes to violence in football, Brazil has alarming rates. Evidence suggests that Brazil may be considered one of the main countries in the world where the most people are killed for soccer-related reasons (Brandão et al., 2020; Murad, 2017). Data also show a trend of increasing trials held by the Supreme Court of Sports Justice regarding cases related to stadium violence (Castro, 2014).

The literature has shown that the mere visual processing of affective stimuli is already capable of influencing parameters such as human physiology and behavior (Mulckhuyse, 2018; Polo et al., 2024; Zsidó, 2024). More specifically regarding the football context, research has demonstrated that simply observing images related to this sport can trigger the activation of emotional circuits in the brains of fans (Duarte et al., 2017; Kelly et al., 2009; Park et al., 2009). Park et al. (2009) demonstrated that the perception of a favorite team in victory circumstances can trigger asymmetrical activation of limbic structures, such as the amygdala, predominantly in the left hemisphere. In defeats, the researchers detected a brain activation pattern indicative of emotional suppression.

Behavioral studies have already found that football stimuli can also modulate cognition and motor behavior (Conde et al., 2011; Conde et al., 2018; Oliveira et al., 2021). Through a reaction time measurement protocol, known as the stimulus-response compatibility task, it is possible to verify significant temporal differences in responses to the favorite and rival teams. More specifically, using images representing soccer players from the main teams in Rio de Janeiro as target stimuli, Conde et al. (2011) adapted the stimulus-response compatibility task to study whether the variable "preference" could modulate the response times to stimuli representing the participant’s favorite and rival teams. The stimuli could appear on either the left or right side of the fixation point, and the responses had to be made with response keys positioned ipsilaterally or contralaterally. In a balanced manner, participants were instructed to respond with the key on the same side for the preferred team (compatible condition) and with the opposite side key (incompatible condition) for the rival team. In the second block, they performed the opposite pairing. The researchers reported a classic spatial compatibility effect for the favorite team stimuli, with spatially corresponding responses being faster than spatially incompatible ones. Meanwhile, for the rival team, an inversion of the compatibility effect was observed, with manual responses being faster when pressed on the opposite side of the appearance of the stimulus representing the rival team. These results were interpreted as evidence that responses to the favorite and rival teams were mediated by approach and avoidance mechanisms, respectively.

Additional studies (Conde et al., 2014; Oliveira et al., 2021; Proctor, 2013) have demonstrated that there are also temporal differences between the two practice blocks. More specifically, in the block where responses are ipsilateral to the preferred team and contralateral to the rival team, responses are faster than those executed to the opposite pairing (incompatible condition for the preferred team and compatible response for the rival team).

Oliveira et al. (2021) adapted the task to verify whether emotional effects triggered by football stimuli could also influence response patterns in another attentional test, known as the Simon task. In the Simon task, participants need to select the correct response as quickly as possible, based on processing an intrinsic attribute of the stimulus (such as shape or color). Even though the stimulus location is not considered for response selection, spatial codes appear to require automatic processing, which can affect motor responses. In this sense, faster responses are observed in the spatially compatible condition compared to the incompatible condition. This temporal difference between the two conditions is called the Simon effect. In Oliveira et al.'s (2021) study, it was shown that the Simon effect varies according to the preference for football teams, being greater for the favorite team. The authors interpreted the research results by indicating that the valence of positive and negative stimuli facilitates and/or inhibits motor responses. They also estimated that the increased effect for the favorite team could be an indicator that the stimulus affective valence facilitates the spatially corresponding response for the favorite team and the contralateral responses for the rival team.

Despite the aforementioned studies providing important insights into how specific football images can influence the affect, cognition, and behavior of fans, other variables need further understanding in this context, such as fanaticism. Although there are different theoretical and philosophical perspectives on fanaticism (Battaly, 2023; Cassam, 2023; Katsafanas, 2024), this construct has been widely understood as a dysfunctional psychosocial phenomenon, characterized by intense and devotional involvement with ideologies, institutions, doctrines, objects, and/or even other people (such as idols or martyrs) who represent them or share their values/ideals (Tietjen, 2023a). Currently, the study of fanaticism holds great social relevance as this phenomenon has been implicated in coercive behavior, violent and hostile actions, and even wars and extremism in various contexts (Tietjen, 2023b).

Specifically in the context of sports, fanaticism has also been widely associated with episodes of aggression, hostility, widespread violence, murders, and public disorder (Bandeira & Ramos, 2020; Conde & Coriolano, 2019; Coriolano & Conde, 2017; Louis, 2023; Zeferino et al., 2021). Given the many gaps still existing in the full understanding of this phenomenon, the present study aimed to investigate how the visualization of football team images, with antagonistic affective valence (favorite and rival), can influence emotional indicators. The research design also aimed to investigate whether different levels of fanaticism can influence the scores attributed to the dimensions of valence (whether of pleasure or displeasure) and emotional arousal (alerting or relaxing) when presented with images.

Methods

The present research can be characterized as a quasi-experimental approach, designed with independent variable control and adopting validated procedures to investigate emotional parameters resulting from the visualization of images of the favorite and rival football teams. The study used as dependent variables the measures of hedonic valence and emotional arousal, attributed to different categories of images. Adopting a comparative perspective, two levels of fanaticism were considered as an intergroup categorical variable, allowing the analysis of differences between fans classified as high and low fanaticism. The intragroup variables were established in five image categories, which included not only the favorite and rival teams but also stimuli from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS), including positive, negative, and neutral images, providing important valence and arousal parameters in comparison with the experimental images.

Participants

This study included 27 participants, 22 women and 5 men (Mage = 22 years, SD = 3.25). The study was advertised on social media and through flyers placed in public areas of the Institute of Social Sciences and Regional Development (Fluminense Federal University) in Campos dos Goytacazes (Rio de Janeiro, Brazil). People were also invited in person during class breaks and while passing through the Institute, characterizing a convenience sample composed of students from various periods and undergraduate courses, as well as service providers and technical staff of the University. For the analysis, participants were divided into two distinct groups based on the levels of fanaticism verified using the Football Fanaticism Scale. More specifically, the high fanaticism group consisted of 13 people (10 women, 3 men), and the low fanaticism group consisted of 14 people (12 women, 2 men). Volunteers did not receive remuneration or academic benefits for their participation. All signed the Free and Informed Consent Form (FICF). The research was approved by the Ethics and Research Committee of the Federal University of Pernambuco (Opinion No. 2.140.159).

Instruments

Football Fanaticism Scale (FFS). This instrument allows the assessment of fanaticism levels in football/soccer fans (Wachelke et al., 2008). The 11 items of the scale evaluate behaviors, beliefs, and situations that may reflect how the person supports their football team. The instrument demonstrated acceptable psychometric indicators in a study on factorial validity and internal consistency in Brazil (Wachelke et al., 2008), such as KMO = 0.94, significant Bartlett’s test of sphericity (p < .001), eigenvalue = 6.14, and Cronbach's alpha (α = .91). The unidimensional scale has a Likert-type format with 7 points, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 7 (strongly agree).

Self-Assessment Manikins Scale (SAM): This instrument uses a non-verbal pictorial perspective that is easy and quick to apply for evaluating images with emotional content (Bradley & Lang, 1994; Bynion & Feldner, 2020). With this instrument, it is possible to obtain information about two emotional dimensions: valence and arousal. The first dimension measures the degree of pleasantness of the figure presented, while the second indicates the level of alertness, arousal, or emotional excitement experienced by the volunteer when observing the image. In the scale, participants must indicate how positive or negative an image is (emotional valence) and the level of psychophysiological arousal (emotional activation) triggered by observing the images. To do so, horizontally arranged manikins are presented as graphical indicators of emotional states, with 9 response levels (Figure 1). Following the evaluation norms of the IAPS in Brazil (Lasaitis et al., 2008), each volunteer received an instruction booklet to classify the images and a pen for completion. Participants were informed that they could also use the spaces between the manikins, representing intermediate options. Thus, participants respond by classifying the images presented through SAM, marking an X on or between the five manikins.

International Affective Picture System (IAPS) and experimental stimuli: The image bank used for evaluation was composed, in a balanced manner, of positive, negative, and neutral images from the IAPS. The IAPS is a database containing 960 images, divided into 16 sets of 60 items (Branco et al., 2023). These hundreds of high-resolution photographs represent various aspects of real life (sports, fashion, landscapes, violence, etc.) (Lang et al., 2005). Many studies have already shown that IAPS images are capable of inducing a wide range of emotional states that can be easily presented in the experimental laboratory context. The present study used 60 IAPS images, with 15 negative images randomly selected, equally distributed among the subcategories of mutilation, venomous animals, and violence; 15 positive images equally distributed among erotic, sports, and family relationship with babies; and 30 neutral images equally distributed among household objects, abstract art, and indifferent faces. In addition to the IAPS images, each evaluation block included 30 paired experimental images, consisting of 15 of the favorite team and 15 of the rival team. Images from the four main football teams in Rio de Janeiro (Fluminense, Flamengo, Vasco da Gama, and Botafogo) were used. The experimental images were carefully selected from the internet considering the demand for contextual pairing, background colors, situational and symbolic for both teams. Thus, the images of each team included, in a balanced manner, categories such as flags, mascots, supporters, uniforms, objects with team symbols, and popular players.

Procedures

After signing the Free and Informed Consent Form (FICF), participants filled out a document with their personal information, where data such as date of birth, gender identity, education level, information on pathologies diagnosed by a doctor, drug and/or psychotropic medication use, possible ophthalmological issues, and whether they used corrective glasses were collected.

After filling out the sociodemographic information, participants were invited to complete the Football Fanaticism Scale (FFS) (Wachelke et al., 2008). They were also asked to rank, in order of preference, the four main football teams from Rio de Janeiro, Brazil (Fluminense, Flamengo, Vasco da Gama, and Botafogo). This procedure was used to select the visual stimuli to be used as experimental conditions, with the first and fourth teams being considered the preferred and rival teams, respectively.

Next, participants were directed to a room with controlled temperature and adequate lighting to watch a video with instructions on how to participate in the experiment. Afterward, they proceeded to the evaluation of the images and the completion of the SAM scale. The instructional video provided directions and examples on how to respond to the SAM scale for each studied dimension (valence and arousal). Participants were instructed to select only one of the nine possible responses for each image, for each of the studied dimensions, starting with valence and then arousal. They were also guided to carefully observe the images presented for the entire time they were displayed on the screen and, only afterward, mark their responses on the SAM scale, indicating how they would classify the image and how they felt while viewing the previous image. Instructions were also given not to speak during the research, not to copy other participants' responses, and to turn off electronic devices.

The evaluation began with the presentation of a slide showing the image number and informing participants that it would be displayed for 5 seconds. The image to be evaluated was then projected onto the screen for another 5 seconds. Subsequently, no slide was projected for 10 seconds, giving participants time to classify the viewed image according to the studied dimensions, starting with valence and then arousal (Figure 1). Participants were instructed to evaluate the affective valence of each image, considering that the left end of the response booklet represented the maximum positive valence (pleasant), and the right end represented the maximum negative valence (unpleasant). For the arousal evaluation, they were told to consider the left end as the maximum level of arousal and the right end as the minimum level of arousal.

Figure 1: Image assessment procedure in the dimensions of valence and emotional arousal

Note.: Illustrative figure. The blank spaces on the SAM scale can also be used, representing 9 possible response levels.

Statistical Analysis

The responses obtained from the evaluation of each image (positive, negative, and neutral categories from the IAPS, as well as experimental images of the favorite and rival teams) were tabulated and organized to calculate the mean and standard deviation of the values assigned to the two dimensions measured by the SAM (emotional arousal and valence). The level of fanaticism was estimated based on the scores obtained on the Football Fanaticism Scale (FFS). To define the two groups with distinct levels of fanaticism (high and low) as a categorical variable, the median score on the FFS was established as the cutoff point. This model for defining different fanaticism groups through the FFS follows protocols previously adopted (Conde et al., 2018; Coriolano & Conde, 2017).

Next, the data were analyzed using repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Statistica® software (StatSoft, version 6.0). The ANOVA design included the level of fanaticism (high and low fanaticism) as the intergroup variable and the image categories as the intragroup variables: (a) favorite team; (b) rival team; (c) IAPS images with negative emotional valence; (d) IAPS images with neutral emotional valence; (e) IAPS images with positive emotional valence.

Planned contrast comparisons were used as additional analyses to minimize the risk of type I error when investigating previously formulated hypotheses, and to allow specific analyses comparing the variables of interest in isolation. The significance level for comparisons between groups was set at p ≤ 0.05. Eta squared (η²) was used to estimate the effect size indicated by the ANOVA, and Cohen's d for planned comparisons.