10.22235/cp.v18i2.3598

Percepção do vínculo parental e variáveis associadas ao apego materno-fetal na gestação de alto risco

Perceived parental bonding and variables associated with maternal-fetal attachment in high-risk pregnancy

Percepción del vínculo parental y variables asociadas al apego materno-fetal en embarazos de alto riesgo

Henrique Lima Reis1, ORCID 0000-0001-7591-2010

Ketylen Cardoso Nogueira2, ORCID 0009-0003-8980-0564

Edi Cristina Manfroi3, ORCID 0000-0003-2375-1205

André Pereira Gonçalves4, ORCID 0000-0002-2470-4040

1 Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Brasil, [email protected]

2 Universidade Federal da Bahia, Brasil

3 Universidade Federal da Bahia, Brasil

4 Universidade Federal da Bahia, Brasil

Resumo:

Este estudo investigou os efeitos da percepção do vínculo parental, variáveis sociodemográficas e gestacionais na intensidade do apego materno-fetal (AMF) no contexto de gestação de alto risco. Trata-se de um estudo quantitativo e transversal com 119 participantes. Foi aplicado um questionário sociodemográfico, a Escala de Apego Materno-Fetal - Versão Breve e o Parental Bonding Instrument. Os resultados da análise de regressão linear múltipla foram estatisticamente significativos (p < 0,05). O modelo final explicou 28,7 % da variância do AMF e foi composto pelas variáveis de superproteção paterna, cuidado paterno, idade da mulher, idade gestacional e suporte do pai do bebê. Reitera-se que a intensidade do AMF é multideterminada, envolvendo aspectos da história de vida, sociais e situacionais. A percepção da mulher acerca do vínculo paterno durante sua infância e adolescência e o apoio do pai do bebê no período gestacional destacam-se como fatores influentes para a vinculação materno-fetal, indicando a importância do envolvimento paterno ao longo do ciclo vital. São pontuadas implicações para a prática profissional, bem como limitações e recomendações de estudos futuros.

Palavras-chave: relações materno-fetais; gravidez de alto risco; relações familiares; gestação.

Abstract:

This study investigated the effects of perceived parental bonding, sociodemographic and gestational variables on the intensity of maternal-fetal attachment (MFA) in the context of high-risk pregnancies. This is a quantitative, cross-sectional study involving 119 participants. A sociodemographic questionnaire, the Maternal-Fetal Attachment Scale-Brief Version, and the Parental Bonding Instrument were administered. The results of the multiple linear regression analysis were statistically significant (p < .05). The final model explained 28.7 % of the variance in MFA and included the variables of paternal overprotection, paternal care, maternal age, gestational age, and the support from the baby's father. We emphasize that MFA intensity is multidetermined, involving aspects of life history, social, and situational factors. The woman’s perception of paternal bonding during her childhood and adolescence, as well as the support from the baby's father during the gestational period, are highlighted as influential factors for maternal-fetal attachment, indicating the importance of paternal involvement throughout the life cycle. Implications for professional practice, as well as limitations and recommendations for future studies are discussed.

Keywords: maternal-fetal relations; high-risk pregnancy; family relations; pregnancy.

Resumen:

Este estudio investigó los efectos de la percepción del vínculo parental, las variables sociodemográficas y gestacionales en la intensidad del apego materno-fetal (AMF) en el contexto de embarazos de alto riesgo. Se trata de un estudio cuantitativo y transversal con 119 participantes. Se aplicó un cuestionario sociodemográfico, la Escala de Apego Materno-Fetal-Versión Breve y el Instrumento de Vínculo Parental. Los resultados del análisis de regresión lineal múltiple fueron estadísticamente significativos (p < .05). El modelo final explicó el 28.7 % de la varianza del AMF y estuvo compuesto por las variables de sobreprotección paterna, cuidado paterno, edad de la mujer, edad gestacional y apoyo del padre del bebé. Se reitera que la intensidad del AMF es multideterminada, lo que involucra aspectos de la historia de vida, sociales y situacionales. La percepción de la mujer sobre el vínculo paternal durante su infancia y adolescencia, así como el apoyo del padre del bebé durante el período gestacional, destacan como factores influyentes en el apego materno-fetal, lo que indica la importancia de la participación paterna a lo largo del ciclo vital. Se puntualizan implicaciones para la práctica profesional, así como limitaciones y recomendaciones para estudios futuros.

Palabras clave: relación materno-fetal; embarazo de alto riesgo; relaciones familiares; embarazo.

Recebido: 26/07/2023

Aceito: 23/09/2024

Apesar da maior parte das gestações ocorrerem sem maiores intercorrências, no Brasil, cerca de 20 % das mulheres apresentam comorbidades e riscos nesse período (Alves et al., 2021). A gravidez de alto risco ocorre quando o processo de gestação envolve risco à saúde da mãe e/ou do feto e alguns fatores podem aumentar as chances de sua ocorrência (Gadelha et al., 2020). Os fatores de risco estão relacionados às características individuais, condições sociodemográficas desfavoráveis, história reprodutiva anterior, doenças obstétricas na gravidez atual e intercorrências clínicas (Rodrigues et al., 2017). Esses aspectos podem desencadear estresse e prejuízos na saúde mental da gestante, com risco de impactar no processo de vinculação com o bebê e, consequentemente, acarretando prejuízos para seu desenvolvimento bem como para o processo de adaptação à maternidade (Topan et al., 2022).

Considerando a importância da vinculação mãe-bebê para um desenvolvimento saudável, Cranley (1981) definiu o apego/vínculo estabelecido pela mãe em relação ao feto como “apego materno-fetal” (AMF). Ele se caracteriza como a intensidade das atitudes da mulher, no período de gestação, relacionadas ao estabelecimento de vínculo e proximidade com o feto, envolvendo aspectos cognitivos e afetivos, bem como suas atribuições em relação às características físicas e emocionais deste (Suryaningsih et al., 2020; Trombetta et al., 2021). O desenvolvimento do AMF é um importante componente durante o processo de constituição e adaptação à maternidade, podendo influenciar na vivência da gestação e na qualidade relação mãe-filho após o nascimento (Ponti et al., 2021; Sacchi et al., 2021).

Estudos de revisão indicam que o AMF funciona como preditor de um desenvolvimento emocional, comportamental, cognitivo e social saudável da criança na primeira infância e que mães que desenvolveram um AMF mais intenso mostram-se menos autocríticas, mais engajadas em comportamentos saudáveis na gestação e menos vulneráveis a sintomas psicológicos negativos (Rollè et al., 2020; Trombetta et al., 2021). O AMF também apresenta relação com uma maior percepção de competência em relação aos cuidados parentais no puerpério, maior sensibilidade da mãe para identificar as necessidades do recém-nascido e melhor adaptação à maternidade (Çelik & Güneri, 2020; Göbel, 2019).

A formação do apego materno-fetal é multidimensional, com influências de variáveis socioeconômicas, qualidade do relacionamento conjugal, escolaridade da gestante, idade gestacional e apoio social (Cheraghi & Jamshidimanesh 2022; Sacchi et al., 2021; Topan et al., 2022). Estudos de revisão indicam o apoio social (familiar e conjugal) como uma importante variável contextual na determinação da intensidade do AMF, sendo que uma maior percepção deste suporte se relaciona com melhor vinculação materno-fetal e transição para a parentalidade (Cerqueira et al., 2023; Yarcheski et al., 2009). No entanto, outro fator determinante é a própria história de vinculação da gestante com seus cuidadores. Este é um aspecto estruturante da personalidade, que contribui para a formação dos modos de funcionamento interno (representações mentais ou crenças que orientam a percepção e o comportamento do indivíduo) e, consequentemente, para suas atitudes no cuidado parental (Gioia et al., 2023; Rosa et al., 2021).

De acordo com a teoria do apego a qualidade e dinâmica de relacionamento estabelecida com os cuidadores principais, especialmente na infância e adolescência, contribuem para a formação dos modelos internos de funcionamento. Estes se constituem como representações mentais que a criança produz acerca do ambiente, de si mesma e dos relacionamentos (Karantzas et al., 2023). Tais modelos evoluem com o desenvolvimento da criança e passam a funcionar como guias para a interpretação de eventos e relacionamentos ao longo da vida e, com isso, integram sua personalidade (Fraley & Roisman, 2019; Selcuk et al., 2024). Por envolverem aspectos afetivos e cognitivos, tendem a impactar fortemente nas relações interpessoais, nos processos de vinculação, construção do self e no exercício da parentalidade (Richter et al., 2022; Sacchi et al., 2021). Durante o período gravídico, é comum que as lembranças e percepções que a mulher tem da sua vinculação com figuras parentais sejam revisitadas. Esse processo pode influenciar na maneira como ela se percebe enquanto mãe e na sua proximidade com o filho, com a possibilidade de reelaboração e atribuição de novos significados a essas memórias durante a gestação (Balle 2017; Handelzalts et al., 2018; Hinesley et al., 2020).

Apesar de o modelo teórico do apego propor que a qualidade e a intensidade da vinculação primária exercem influência sobre outros vínculos ao longo da vida, ainda são poucos trabalhos empíricos que buscaram avaliar as relações da vinculação primária com o AMF, especialmente em se tratando do contexto de alto risco (Cerqueira et al., 2023; Handelzalts et al., 2018; Sacchi et al., 2021). Cerqueira et al. (2023) realizaram pesquisa de revisão com objetivo de investigar a literatura científica acerca do AMF na gravidez de alto risco e reforçam a necessidade de pesquisas que também considerem a história de vinculação da gestante como um fator influente, ressaltando a ausência de estudos com esse objetivo e com essa população especialmente no contexto brasileiro. Ademais, em levantamento bibliográfico dos últimos 13 anos realizado pelos autores do presente estudo, foram encontradas apenas dez pesquisas relacionando os vínculos primários e o apego materno-fetal. Destes, apenas dois (Balle, 2017; Handelzalts et al., 2018) utilizaram como parte da amostra gestantes de alto risco. Porém, não foram feitas comparações de grupo ou análises distintas considerando o risco gestacional, impossibilitando avaliar se as relações entre as variáveis e os resultados se comportam de maneira semelhante em ambas as condições.

Dois trabalhos encontrados foram realizados no Brasil (Balle, 2017; Rosa et al., 2021). Em pesquisa com 839 gestantes sem risco gestacional, Rosa et al. (2021) investigaram o poder explicativo de variáveis sociodemográficas, gestacionais e de vinculação primária (por meio do Parental Bonding Instrument, PBI) na intensidade do AMF por meio de análises de regressão. As gestantes que estavam no primeiro trimestre de gravidez, não moravam com um parceiro e não se sentiam apoiadas pelo pai do bebê durante a gestação apresentaram escores mais baixos de AMF. No entanto, quando controladas estas variáveis, a superproteção paterna foi um preditor positivo do AMF, enquanto as demais dimensões da vinculação primária (Cuidado Materno e Paterno e Superproteção Materna) não apresentaram relações estatisticamente significativas. Vale pontuar que todas as participantes do estudo apresentaram alta intensidade de AMF, independente da percepção do vínculo parental, indicando que, durante o período gestacional, a mulher pode vincular-se com o bebê, mesmo não tendo lembranças positivas na infância.

Ainda no contexto nacional, Balle (2017) realizou estudo com 364 gestantes, sendo 14 % delas de alto risco, para identificar as relações do AMF com variáveis sociodemográficas, assistência pré-natal e o fator cuidado do PBI. Em análise de correlação, a autora verificou associação positiva, porém fraca, apenas com o cuidado materno. Por meio de análise de regressão, este mesmo fator explicou 5,1 % da variância do AMF. Apesar de não indicar associação significativa entre a gestação de alto risco e o apego materno-fetal, esta variável relacionou-se positivamente com a idade gestacional e negativamente com a idade da gestante.

Em estudo longitudinal com 1301 gestantes sem risco gestacional, Fukui et al. (2021) investigaram as relações entre a vinculação primária (PBI), vinculação materno-fetal e indicadores de saúde mental. Por meio de Path Analysis indicam que a percepção de baixo cuidado materno e paterno prejudicaram a vinculação com o bebê e que esse efeito se manteve após o parto. Os autores, contudo, não discutem os possíveis efeitos de variáveis sociodemográficas (e.g. idade) ou gestacional (e.g. primiparidade e idade gestacional) nestas relações. Em contrapartida, Gioia et al. (2023), com uma amostra de 1177 gestantes e por meio de análises de regressão, indicam que a idade gestacional, primiparidade e percepção dos cuidados paternos e maternos (avaliados por meio do PBI) foram preditores estatisticamente significativos da vinculação materno-fetal. Vale ressaltar que essa relação não foi mediada por indicadores de saúde mental (e.g. ansiedade e depressão), o que indica efeitos diretos. van Bussel et al. (2010) apontam resultados semelhantes a partir de correlações positivas, porém fracas, entre o cuidado paterno e o AMF em uma amostra com 403 gestantes. Não foram encontradas relações significativas com outras variáveis sociodemográficas ou gestacionais.

Sacchi et al. (2021) investigaram a associação entre AMF, saúde mental, relação conjugal e vinculação primária materna com uma amostra de 113 gestantes de baixo risco. Através de análises de correlação e regressão, o cuidado materno mostrou-se positivamente relacionado ao AMF, assim como a qualidade da relação conjugal. Os autores indicam que os relacionamentos passados e atuais da gestante são modelos para as representações maternas da sua relação com o bebê, impactando na vinculação. Em convergência, Handelzalts et al. (2018) também encontraram correlação positiva entre AMF e o cuidado materno em estudo com 341 gestantes, sendo 17,4 % delas em gestação de alto risco. No entanto, quando realizada análise de regressão, as mulheres com altos escores nos fatores Cuidado e Negação de Autonomia da vinculação materna apresentaram também AMF mais forte. Outros fatores relacionados a uma maior intensidade do AMF foram idade mais jovem, baixa escolaridade e menor número de partos anteriores. No estudo, não foram encontradas associações significativas entre a condição de alto risco e o apego materno-fetal.

Em estudo com 101 gestantes, Hinesley et al. (2020) investigaram o impacto da exposição a experiências adversas na infância em variáveis maternas, como vinculação primária, AMF e saúde mental, por meio de Path Analysis. Referente ao AMF, apontaram-se relações diretas positivas somente com cuidado paterno e a idade da gestante. Não foram encontradas associações diretas entre experiências adversas (e.g. negligência e coerção) na infância e o AMF, porém, a baixa percepção de cuidado paterno explicou parte do efeito negativo indireto dessas experiências adversas no AMF. No que se refere à vinculação primária, a alta exposição a eventos adversos na infância associou-se negativamente à percepção de cuidado paterno e materno e foi um preditor significativo da percepção do pai e da mãe como intrusivos e controladores.

O estudo de Teixeira et al. (2016) analisou a relação entre AMF, idade gestacional e memórias de práticas parentais (por meio da Escala de Lembranças sobre Práticas Parentais, EMBU) em 179 gestantes. Através de análises de correlação, verificou-se que a rejeição percebida do pai e da mãe está relacionada com menor AMF, mais especificamente com a menor identificação da gestante como futura mãe. As autoras também relataram associação positiva entre a idade gestacional e o AMF. Por fim, ao analisar a relação entre fatores maternos e apego pré-natal em uma amostra de 32 gestantes, Reed (2014) aponta a combinação entre menor cuidado e maior superproteção do cuidador principal, seja este a mãe ou o pai, como fator de risco para menores índices de apego materno-fetal, especialmente em gestantes com baixa escolaridade. Ademais, utilizando análises de variância (ANOVA), as gestantes que relataram alto apoio social, não possuir religião, baixa ansiedade e baixa dependência nas relações adultas atuais apresentaram maior AMF.

Percebe-se uma diversidade de resultados encontrados nos estudos, indicando a necessidade de futuras investigações. Vale pontuar que são ainda mais escassas pesquisas que utilizaram como amostra gestantes de alto risco, sendo que tais estudos não buscaram investigar a percepção do vínculo parental como um possível preditor, considerando apenas informações gestacionais, conjugais, sociodemográficas e de saúde mental (Cerqueira et al., 2023; Cheraghi & Jamshidimanesh 2022; Soares et al., 2022; Topan et al., 2022). Dessa forma, este estudo buscou investigar os impactos da percepção do vínculo primário, variáveis sociodemográficas e gestacionais na intensidade do AMF no contexto de alto risco.

Método

Trata-se de um estudo quantitativo e transversal com amostragem não probabilística por conveniência. A coleta de dados foi realizada entre os meses de fevereiro e maio de 2023 em um hospital materno-infantil localizado na cidade de Vitória da Conquista, Bahia. O local oferece serviços de média e alta complexidade a gestantes da região sudoeste do estado, bem como atendimento psicológico por profissionais da área.

Participantes

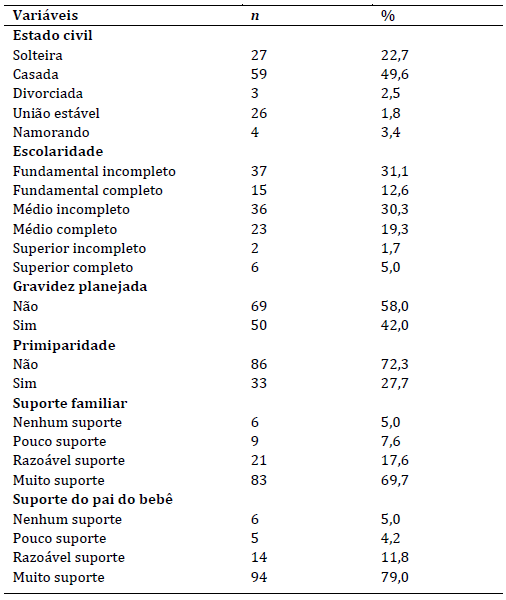

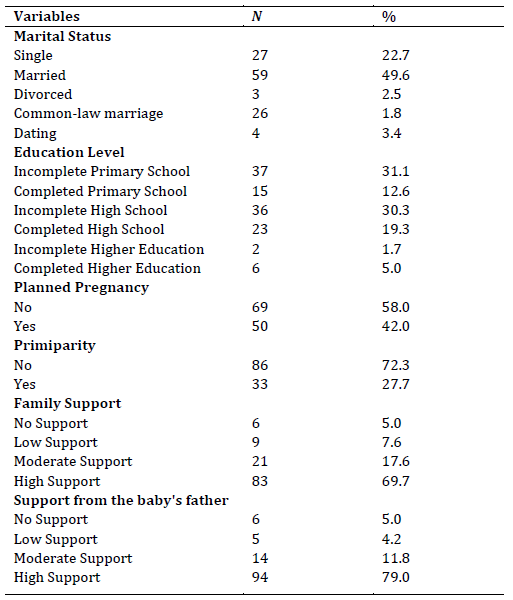

Participaram da pesquisa 119 gestantes com idades entre 18 e 45 anos (M = 30,45; DP = 6,58) e idade gestacional entre 27 e 40 semanas (M = 32,53; DP = 4,03) que estavam em acompanhamento pré-natal de alto risco. Como critérios de inclusão, integraram a amostra mulheres acima de 18 anos com gestação a partir da vigésima sétima semana uma vez que, a partir deste período, a vinculação materno-fetal torna-se mais evidente (Lima et al., 2022; Rosa et al., 2021). Para serem classificadas como “alto risco”, a gestante deveria ter sido diagnosticada por um profissional da medicina que indicasse tal condição. Não foram feitas restrições ou categorizações com relação às diferentes condições (e.g. hipertensão arterial e diabetes gestacional) que pudessem levar ao diagnóstico de risco gestacional. Foram excluídas gestantes com atrasos no desenvolvimento cognitivo, grau moderado/grave de perda auditiva ou afonia (mudez), uma vez que não há adaptação dos instrumentos para as necessidades específicas destas populações. A Tabela 1 apresenta a caracterização das participantes quanto ao estado civil, escolaridade, suporte familiar, suporte do pai do bebê, planejamento da gravidez e primiparidade.

Tabela 1: Características sociodemográficas das participantes

Instrumentos

Questionário Sociodemográfico. Elaborado pelos autores com perguntas a respeito da idade, período gestacional, dentre outras, cujo objetivo foi compreender as condições da gestação e caracterizar a amostra. Foram acrescentadas duas perguntas relacionadas ao suporte social, no qual a participante deveria indicar em uma escala Likert de 0 (Nenhum Suporte) a 3 (Muito Suporte) sua percepção acerca do apoio recebido da sua família (“Como você percebe o nível de suporte que está recebendo dos familiares durante a atual gestação?”) e do pai do bebê (“Como você percebe o nível de suporte que está recebendo do pai do bebê durante a atual gestação?”).

Parental Bonding Instrument (PBI; Teodoro et al., 2010). O instrumento busca investigar a qualidade do vínculo entre pais e filhos na infância e adolescência. O PBI baseia-se na teoria do apego e parte do pressuposto de que as interações primárias com os cuidadores impactam ao longo do ciclo do desenvolvimento do indivíduo. No Brasil, Teodoro et al. (2010) investigaram a validade fatorial e a consistência interna deste. O instrumento possui dois fatores: Cuidado (12 itens) e Superproteção/Controle (13 itens). As respostas são baseadas do tipo Likert (0 até 3 pontos) e são separados entre a versão paterna e materna, sendo a pontuação máxima de 36 pontos para a escala de Cuidado e 39 para a de Superproteção/Controle. Em se tratando da consistência interna, os alphas de Cronbach encontrados foram de 0,91 para Cuidado e 0,87 para Superproteção/Controle na relação materna e de 0,91 e 0,85 na relação paterna, respectivamente.

Escala de Apego Materno-Fetal - Versão Breve (MFAS- Versão Breve; Lima et al., 2022). Criada por Cranley (1981), a escala investiga o vínculo da gestante com o feto e sua versão breve foi adaptada e validada para o Brasil por Lima et al. (2022) em estudo envolvendo 937 gestantes no segundo e terceiro trimestre de gestação. Os valores α de Cronbach = 0,878 e a confiabilidade composta > 0,70 foram apropriados psicometricamente. A escala é composta por 15 itens que são respondidos por meio de uma escala Likert variando entre 1 (Discordo Completamente) e 5 (Concordo Plenamente) e é dividida em três fatores: “Experienciando expectativas”, “Interações com o feto” e “Imaginação e cuidado para com o bebê”. O escore total varia entre 15 e 75, com valores maiores indicando maior intensidade de vinculação. No presente estudo, seguindo recomendações de pesquisas prévias (Gioia et al., 2023; Lima et al., 2022; Rosa et al., 2021; Sacchi et al., 2021), optou-se por utilizar o escore total ao invés dos três fatores da escala.

Procedimentos

Coleta de Dados

As participantes que aguardavam atendimento de pré-natal de alto risco foram convidadas a participar da pesquisa por estagiários e extensionistas vinculados ao Núcleo de Especializado de Estudos em Desenvolvimento Humano (NEEDH) da Universidade Federal da Bahia - Instituto Multidisciplinar em Saúde (UFBA-IMS) previamente orientados por psicólogos contratados do hospital. Todas as gestantes que eram atendidas no hospital possuíam diagnóstico de gestação de alto risco. Não houve critério pré-definido acerca de quais mulheres da sala de espera seriam abordadas. Após o contato inicial, caso as gestantes preenchessem os critérios de inclusão e aceitassem participar do estudo, eram orientadas de que sua contribuição era voluntária e que a recusa no preenchimento dos instrumentos não acarretaria nenhum tipo de prejuízo ao atendimento hospitalar recebido.

O Termo de Consentimento Livre e Esclarecido (TCLE) foi lido antes da aplicação dos instrumentos e apenas participaram do estudo aquelas que concordaram com o referido documento. Durante a leitura do TCLE, as gestantes foram instruídas quanto ao risco de desconforto emocional em função da temática investigada e aquelas que apresentaram tal reação foram acolhidas pelos pesquisadores e encaminhadas para o Serviço de Psicologia do hospital para acompanhamento com as profissionais de referência do serviço. Após consentimento, as gestantes foram entrevistadas pelos pesquisadores de forma individual na sala de espera durante, aproximadamente, 30 minutos.

Análise de Dados

Os dados coletados foram analisados por meio do Statistical Package for the Social Sciences (SPSS) 25. Estatística descritiva foi utilizada para o cálculo de medidas de frequência, média e desvio-padrão. Posteriormente, foi realizada análise de correlação entre as variáveis preditoras, utilizando como base Cohen (1992) para interpretação do coeficiente r. Assim, foram consideradas correlações fracas (r ≤ 0,29), moderada (0,30 ≤ r ≤ 0,49) e fortes (r ≥ 0,50).

Em seguida, para investigar os determinantes do apego materno-fetal (variável de desfecho), foi conduzida análise de regressão linear múltipla utilizando método de entrada backward. Neste método, todas as variáveis preditoras são inseridas em conjunto no modelo de regressão inicial. O programa avalia a significância estatística de cada variável por meio do valor-p e aquelas não significativas são removidas automaticamente para um modelo mais parcimonioso. Este processo é repetido até que todas as variáveis restantes contribuam de maneira estatisticamente significativa para explicação da variável de desfecho.

Para a seleção das variáveis preditoras/explicativas que fizeram parte do modelo de regressão, utilizou-se como base estudos prévios (Cheraghi & Jamshidimanesh, 2022; Gioia et al., 2023; Handelzalts et al., 2018; Rosa et al., 2021; Sacchi et al., 2021; Soares et al., 2022; Topan et al., 2022), sendo inseridos: dados sociodemográficos (escolaridade e idade), dados gestacionais (idade gestacional, primiparidade, planejamento da gravidez, apoio da família, apoio do pai do bebê) e percepção do vínculo parental (Superproteção Materna, Cuidado Materno, Superproteção Paterna e Cuidado Paterno). Foram consideradas significativas relações com p ≤ 0,05. Os seguintes pressupostos da regressão linear múltipla foram verificados: ausência de multicolinearidade entre as variáveis independentes (variance inflation factor, VIF, próximos de 1), normalidade da distribuição dos resíduos (Lilliefors Test com p > 0,05) e independência entre os resíduos (coeficiente de Durbin-Watson entre 1,5 e 2,5) (Mourão et al., 2021).

Considerações Éticas

O estudo obteve parecer favorável no Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa (CEP) da Universidade Federal da Bahia (UFBA) por meio do Parecer Consubstanciado n° 5.732.443 (nº do CAAE: 62798622.3.0000.5556). Todas as informações do Termo de Consentimento Livre e Esclarecido (TCLE) foram lidas para as participantes antes da aplicação dos questionários e somente fizeram parte da pesquisa as gestantes que concordaram e assinaram o referido termo voluntariamente.

Resultados

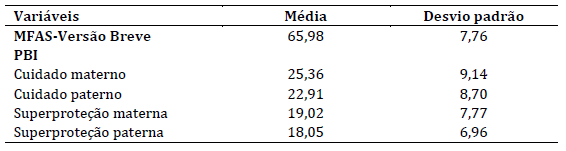

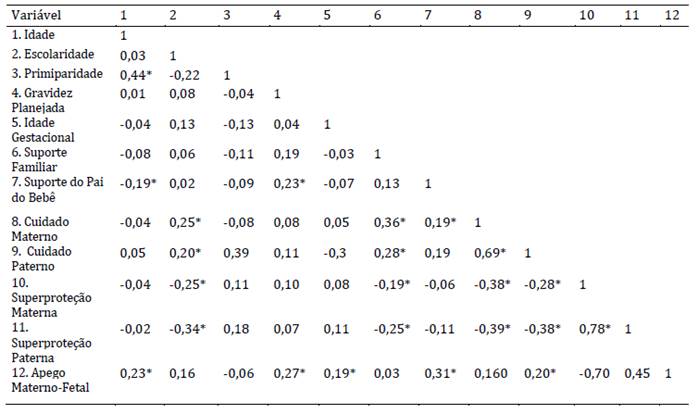

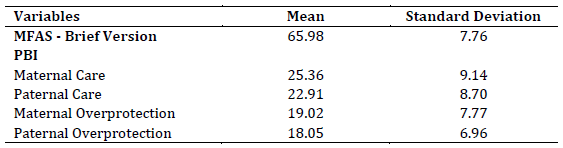

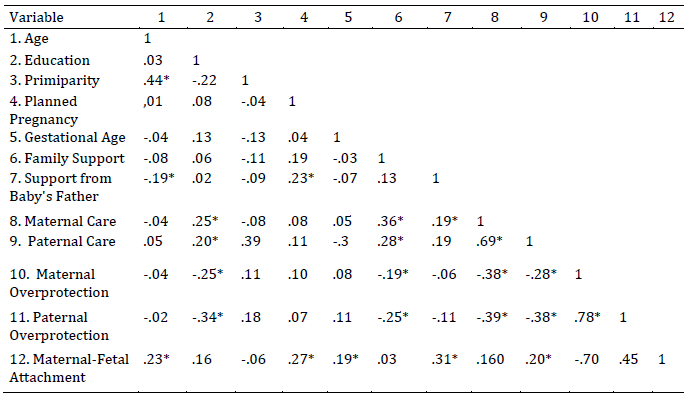

Os primeiros resultados analisados foram as estatísticas descritivas das variáveis apego materno-fetal (MFAS-Versão Breve) e percepção do vínculo parental (PBI). Os valores estão apresentados na Tabela 2. Em seguida, foram realizadas correlações entre as variáveis sociodemográficas, gestacionais, a percepção do vínculo parental e o apego materno-fetal. Os resultados estão apresentados na Tabela 3.

Tabela 2: Estatísticas descritivas do MFAS – Versão Breve e do PBI

Tabela 3: Correlações entre variáveis sociodemográficas, gestacionais, percepção do vínculo parental e apego materno-fetal

*p < 0,05

As análises indicaram correlações fracas e positivas do AMF com a idade, gravidez planejada, idade gestacional e cuidado paterno e correlação moderada e positiva com suporte do pai do bebê. Foram verificadas correlações fortes entre a superproteção materna e a superproteção paterna e entre cuidado materno e cuidado paterno. O suporte familiar correlacionou-se de maneira fraca e negativa com a superproteção materna e paterna e de maneira positiva e forte com o cuidado materno.

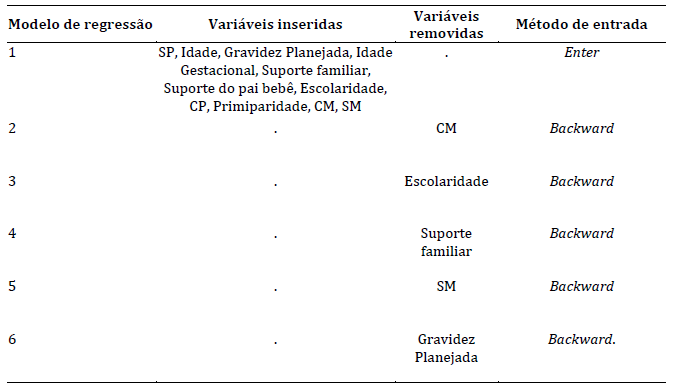

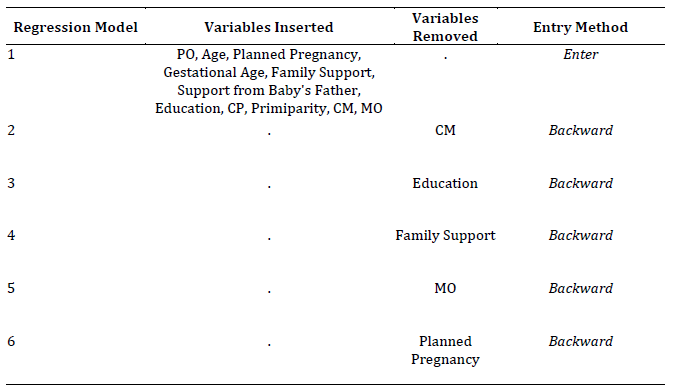

Posteriormente, foi realizada análise de regressão linear múltipla tendo como variável de desfecho o apego materno-fetal. Para realização da análise foi preciso verificar os pressupostos da regressão. O resultado do teste de Kolmogorov-Smirnov (p > 0,05) indicou a normalidade dos resíduos, o coeficiente D (Durbin-Watson) foi igual a 1,993 e valores de VIF variaram entre 1,04 e 1,33, o que indica que os dados preenchem os critérios necessários para que a análise seja conduzida. A Tabela 4 apresenta o processo de inserção e remoção de variáveis a partir do método backward.

Tabela 4: Variáveis inseridas e removidas nos modelos de regressão

Notas: CP: Cuidado Paterno; CM: Cuidado Materno; SP: Superproteção Paterna; SM: Superproteção Materna

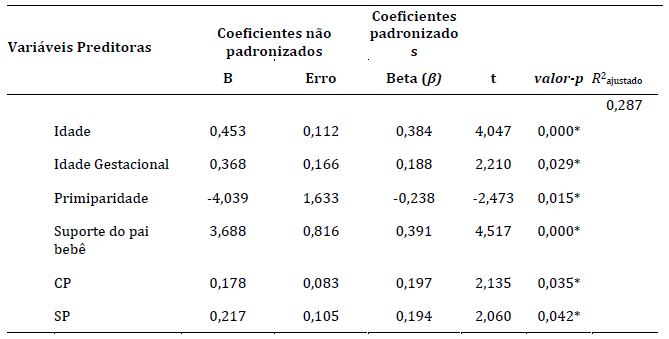

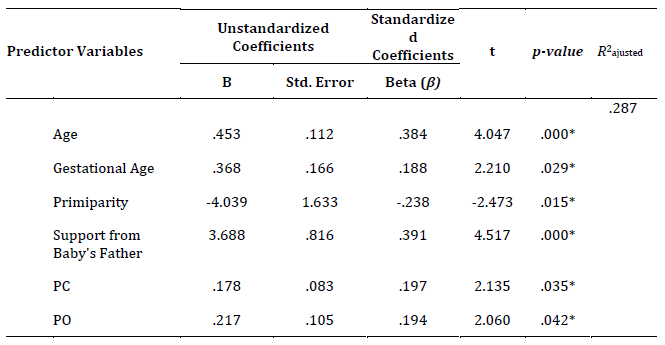

O modelo final (6) da análise de regressão linear múltipla (método backward) tendo como variável de desfecho o AMF apresentou resultado estatisticamente significativo (F (6, 97) = 7,893; p < 0,001; R2ajustado = 0,287), explicando 28,7 % da variância do AMF. As variáveis que compuseram este modelo, em ordem decrescente de contribuição individual (coeficiente padronizado β), foram: suporte do pai do bebê, idade, primiparidade, cuidado paterno, superproteção paterna e idade gestacional. Os coeficientes da análise de regressão que compuseram o modelo final podem ser observados na Tabela 5.

Tabela 5: Modelo final de regressão com o apego materno-fetal como variável de desfecho

Notas: Variável de desfecho: Apego Materno Fetal (MFAS); CP: Cuidado Paterno; CM: Cuidado Materno; SP: Superproteção Paterna; SM: Superproteção Materna. p < 0,05*

Discussão

O objetivo do presente estudo foi avaliar os efeitos da percepção do vínculo primário, variáveis sociodemográficas e gestacionais na intensidade do apego materno-fetal em gestantes de alto risco. Os resultados indicaram que a percepção de superproteção e cuidado paterno na infância e adolescência foram preditores significativos de uma maior intensidade do AMF. Estes resultados reforçam o papel do envolvimento paterno na infância e adolescência com possíveis repercussões no processo de transição para a parentalidade (Diniz et al., 2021). Estudos empíricos sustentam relações positivas entre um maior envolvimento/engajamento paterno e o desenvolvimento infantil como menores índices de problemas comportamentais e psicológicos, melhor funcionamento cognitivo e autoconceito positivo (Diniz et al., 2021; Henry et al., 2020; Rollè et al., 2020). De fato, os resultados deste estudo estão em consonância com outros trabalhos (Fukui et al., 2021; Gioia et al., 2023; Handelzalts et al., 2018; Hinesley et al., 2020; Rosa et al., 2021; van Bussel et al., 2010), embora esses estudos não tenham explorado os motivos ou mecanismos pelos quais as lembranças dos vínculos maternos e paternos afetam diferencialmente a intensidade AMF. Estes resultados também foram encontrados em estudos com gestantes de baixo risco, indicando que o risco gestacional pode não se configurar como variável que afete a relação entre o vínculo primário e o AMF (Cerqueira et al., 2023).

A percepção da gestante sobre o cuidado e a superproteção recebidos do pai pode estar associada a uma maior presença dessa figura em sua vida, contribuindo para a formação de um apego seguro, caracterizado por sentimentos de segurança, proteção e apoio. Essas memórias podem, portanto, fazer com que a gestante se sinta mais preparada para oferecer os mesmos cuidados ao seu filho, refletindo na intensidade do AMF (Rosa et al., 2021). Vale ressaltar que os papeis do pai e da mãe podem ser percebidos e lembrados de maneiras diferentes a depender da cultura e história de vida da gestante. O cuidado e maior envolvimento materno são frequentemente naturalizados, uma vez que as mães são tradicionalmente vistas como as principais cuidadoras e responsáveis pelo bem-estar familiar (Schmidt et al., 2023). Em contrapartida, a participação dos pais (figura paterna) nos cuidados pode ser percebida como um papel de apoio ou complementar ao da mãe, com menores exigências culturais sobre o exercício de sua parentalidade e responsabilidade (Cabrera et al., 2018; Diniz et al., 2021; Grossmann et al., 2008). Dessa forma, quando esta figura paterna assume um papel mais ativo no cuidado e, consequentemente, de maior participação na vida da criança/adolescente, é possível que haja um impacto emocional e afetivo mais profundo, levando a uma maior valorização dessas memórias durante a gestação.

Os fatores de cuidado e superproteção investigados no presente estudo foram descritos inicialmente por Parker et al. (1979) na tentativa de definir mais precisamente o constructo do vínculo parental, propondo que ambos são compostos por dois polos (alto e baixo). O cuidado apresenta-se como a principal dimensão do apego e é caracterizado, no nível alto, por calor emocional, proximidade, carinho, empatia e afeição, enquanto, no extremo baixo, designa frieza emocional, rejeição e indiferença. A superproteção, por sua vez, é definida como controle, vigilância, contato excessivo e infantilização no seu nível alto e, em seu polo baixo, sinaliza o incentivo à independência e autonomia. Apesar de a alta superproteção ser apontada como variável significativa de desfechos problemáticos em esferas do comportamento dos filhos, como habilidades sociais, autoestima e saúde mental (Ferreira, 2016; Martins et al., 2014; Richter et al., 2018; Wendt & Appel-Silva, 2020), ela pode estar relacionada a uma importante tarefa parental: o estabelecimento de regras e limites (Handelzalts et al., 2018). Essa percepção sustenta a influência positiva entre este fator e o AMF mais intenso, conforme encontrada no presente estudo e nas pesquisas de Fukui et al. (2021), Rosa et al. (2021) e Handelzalts et al. (2018).

Outros modelos explicativos das práticas parentais (Baumrind, 1966; Gomide, 2006; Maccoby & Martin, 1983) apontam a alta exigência, a monitoria positiva da conduta e a disciplina consistente como componentes assertivos da parentalidade, influenciando menores níveis de problemas emocionais, bem como índices mais elevados de comportamentos pró-sociais e autoestima (Bhide et al., 2019; Martins et al., 2014; Weber, 2017). Assim, apesar dos possíveis desfechos negativos, a superproteção paterna também pode estar associada a uma percepção positiva de segurança, contribuindo para uma preocupação maior da mulher para com o bebê durante a gestação e, consequentemente, maior intensidade do AMF (Rosa et al., 2021).

Por sua vez, a influência do cuidado paterno no AMF encontrado no presente estudo converge com outros achados da literatura (Fukui et al., 2021; Gioia et al., 2023; van Bussel et al., 2010). A mais recente pesquisa no tema, conduzida por Gioia et al. (2023), indicou que o cuidado ofertado pelo pai foi preditor das dimensões “assumir papel materno” e “atribuir características ao feto” do AMF, apontando ainda a transmissão intergeracional através da epigenética e da observação direta como possível explicação para esse fenômeno. Dessa forma, os mecanismos biológicos, como tendências geneticamente influenciadas (e.g. temperamento), podem ser modulados pelo cuidado parental recebido, amenizando ou potencializando estas características. Além disso, a própria observação dos comportamentos de cuidado dos pais pode funcionar como modelo para o repertório da gestante no seu papel de futura mãe (Provenzi et al., 2020). Tais influências podem ser mais ou menos intensas a depender de outros fatores sociais (e.g. estresse, apoio social), individuais (e.g. afeto negativo) e relacionais (e.g. dinâmica familiar) (Santana & Souza, 2018). Em contrapartida, a percepção de rejeição parental, que pode ser comparada ao polo baixo do cuidado, pode sabotar a adaptação da gestante à maternidade, influenciando um senso de baixa competência para fornecer cuidado neonatal e amamentar (Teixeira et al., 2016).

Assim, indica-se que a relação desenvolvida pela gestante com o cuidador primário na infância e adolescência se estenderá e, consolidando-se ao longo do seu ciclo vital, irá contribuir para a formação e manutenção do modo de funcionamento de futuros vínculos, relacionamentos e estados emocionais, tendendo a se repetir ou impactar na construção e intensidade do AMF (Gioia et al., 2023; Trombetta et al., 2021). Vale destacar que a média do AMF na amostra do presente estudo foi elevada (M = 65,98), indicando que, mesmo quando o vínculo parental percebido com os cuidadores é baixo, é possível que a gestante reformule e atribua novos significados a essas vivências. Portanto, as participantes foram capazes de vincular-se positivamente com o feto e desenvolver uma maior adaptação à maternidade, especialmente com o apoio do pai do bebê, sustentando uma perspectiva não determinista da vinculação primária (Rosa et al., 2021; Topan et al., 2022).

Em estudo de revisão com metanálise, Yarcheski et al. (2009) apontam o suporte do parceiro durante a gestação como importante aspecto a ser considerado, possuindo tamanho de efeito moderado na predição da intensidade do AMF. Além disso, Cuijlits et al. (2019), em pesquisa com 739 gestantes, também identificam o apoio do parceiro como principal fator de proteção durante a gestação e no pós-parto, enquanto Sacchi et al. (2021) e McNamara et al. (2019) indicam a qualidade da relação conjugal associada positivamente a um maior AMF. O suporte do pai do bebê se configura como um tipo específico de suporte social que tende a envolver mais componentes afetivos e emocionais na gestante. Portanto, pode se configurar como importante fator protetivo para o processo de adaptação à maternidade, reduzindo estresse, ansiedade e sentimentos ambivalentes que possam estar presentes, promovendo a autoeficácia da mãe (Campbell, 2022). Em convergência, os resultados do nosso estudo apontaram que a variável “suporte do pai do bebê” foi a que mais impactou no nível do AMF (β = 0,391), reforçando a importância de um maior envolvimento paterno desde a gestação. É possível que a percepção deste suporte por parte da gestante seja maior por conta da gestação de alto risco, a qual, devido ao contexto de maior incerteza e preocupação quanto à saúde do filho, enseja uma necessidade também maior de apoio paterno, indicando uma relação de influência bidirecional (Rocha et al., 2022; Topan et al., 2022; Yarcheski et al., 2009).

A literatura aponta a relevância do papel do pai em uma experiência gravídico-puerperal mais saudável, visto que a aceitação do filho e o apoio durante a gestação associam-se a desfechos significativos no senso de autoeficácia da mãe e em menores índices de sofrimento psíquico materno, que poderiam impactar negativamente no AMF (Papalia & Martorell, 2022). A participação paterna no pré-natal pode gerar benefícios como a melhoria da união familiar (pai-mãe-filho), diminuição da ansiedade e de preocupações sobre o ciclo gravídico e maior clareza e aceitação das transformações ensejadas pela gravidez, na medida em que o parceiro constrói um ambiente seguro e acolhedor que contribui para uma maior interação entre a mãe e o bebê (Vieira & Aguiar, 2021). Em estudo de revisão acerca do AMF no contexto de alto risco, Cerqueira et al. (2023) ressaltam o apoio social como principal fator protetivo para uma vinculação positiva. Assim, a qualidade das relações atuais e suporte recebido podem afetar mais fortemente o processo de relação materno-fetal do que as lembranças sobre o vínculo parental.

Os resultados também indicaram que a idade gestacional impacta positivamente no AMF, corroborando com outros estudos que apontam que os comportamentos de apego se intensificam com o avanço da gestação (Cuijlits et al., 2019; Gioia et al., 2023; Rosa et al., 2021, Yarcheski et al., 2009). Tal efeito se deve especialmente por conta de uma maior interação entre a díade mãe-bebê a partir do movimento intrauterino, maiores experiências corporais/físicas e proximidade do parto, tornando mais real a vivência da gestação e, consequentemente, reforçando o estabelecimento de vínculo. A idade da mãe também se associou com uma maior intensidade do AMF, convergindo com Gioia et al. (2023), McNamara et al. (2019) e Yarcheski et al. (2009), uma vez que gestantes mais novas podem experienciar com maior intensidade sentimentos ambíguos em relação à gravidez, apresentando maior dificuldade no processo de adaptação à maternidade e, consequentemente, na vinculação ao feto, especialmente na gestação de alto risco (Çelik & Güneri, 2020; Cerqueira et al., 2023).

Por fim, o fator de primiparidade também se configurou como explicativo do AMF, constituindo uma relação negativa. Apesar deste achado corroborar com o estudo de revisão feito por McNamara et al. (2019) ao apontar que a multiparidade está relacionada com uma maior intensidade de AMF, Yarcheski et al. (2009) indicam um tamanho de efeito moderado a nulo na relação entre paridade e AMF, o que sustenta o caráter inconclusivo da relação entre essas variáveis (Fukui et al., 2021).

Conclusões

Esta pesquisa apresenta contribuições significativas para uma maior compreensão dos fatores envolvidos no vínculo materno-fetal e para o desenvolvimento de práticas psicológicas. Este é um dos poucos estudos que buscou avaliar os efeitos da vinculação parental e de outras variáveis no AMF considerando a gestação de alto risco, tema ainda pouco explorado na literatura científica nacional e internacional com essa amostra, apesar de sua relevância para a saúde pública. Primeiramente, apesar da maior parte dos estudos focarem na figura materna e no seu impacto durante a gestação, nossos resultados reforçam a importância do papel do pai no desenvolvimento. Sua presença e apoio podem tornar o processo de vinculação mais positivo para a díade mãe-bebê, contribuir para um processo favorável de adaptação à maternidade e, finalmente, para o desenvolvimento saudável da criança. Este suporte pode ser incentivado por profissionais da saúde em todo o fluxo de pré-natal, parto e puerpério através da inclusão dos parceiros como público-alvo das políticas públicas, a exemplo do Programa Pré-Natal do Parceiro, proposto pelo Ministério da Saúde (2016). Tal processo pode englobar a postura acolhedora e inclusiva para com os homens no ambiente dos serviços de saúde (que são maioritariamente frequentados por mulheres), a orientação sobre temas relevantes do processo gravídico e puerperal, atividades educativas de preparação para exercer o papel de pai e a participação no momento do parto, estimulando o seu papel enquanto cuidador e figura de apego.

De forma retrospectiva, o vínculo da mulher com seu próprio pai durante a infância e adolescência também apresenta uma influência significativa no exercício da parentalidade, com repercussões durante todo seu ciclo vital. Nossos resultados destacam o envolvimento paterno como um fator protetivo essencial para o desenvolvimento saudável da criança, sublinhando a importância de criar intervenções que promovam a participação ativa das figuras paternas nos cuidados infantis. Grupos de orientação parental voltados especificamente para homens, intervenções que fortaleçam a relação coparental e estratégias de psicoeducação que sustentem a relevância da participação paterna no desenvolvimento infantil são recomendados como abordagens eficazes (Gonzalez et al., 2023; Nascimento et al., 2022). Pesquisas focadas na relação coparental, particularmente no fenômeno do gatekeeping materno, indicam que o suporte e o encorajamento da mãe são fatores cruciais para o aumento do envolvimento paterno na vida da criança (Altenburger, 2022; Campbell, 2022). Tais práticas podem ser promovidas em consultas e atendimentos pré-natais, bem como em grupos de apoio para gestantes, a partir de psicoeducação, reflexões acerca da maternidade e paternidade e indicação da importância do apoio social para redução da sobrecarga, estresse e aumento da vinculação.

Em relação às limitações deste estudo, destacamos possíveis vieses de memória associados ao PBI, uma vez que o suporte familiar atual e as relações parentais vigentes podem influenciar as lembranças e respostas das participantes. Além disso, devido à impossibilidade de realizar coletas individuais, o contexto de aplicação dos questionários, que ocorreu na sala de espera do pré-natal de alto risco, deve ser considerado, pois algumas gestantes podem ter se sentido constrangidas ou, por conta da desejabilidade social, ter evitado reportar experiências aversivas com seus cuidadores e um possível baixo vínculo materno-fetal. Para futuros estudos, é recomendável que a coleta de dados ocorra em ambientes mais privativos ou seja conduzida por profissionais que já possuam um vínculo estabelecido com os participantes, a fim de minimizar essas limitações.

Recomendamos também que novos estudos incluam amostras compostas por gestantes de alto risco e gestantes saudáveis, com o objetivo de comparar os níveis de suporte paterno em ambos os grupos, bem como o envolvimento dos pais durante a gestação de suas parceiras. A inclusão dos pais dos bebês ou dos parceiros das gestantes como participantes, bem como a investigação de suas percepções sobre o relacionamento com a gestante e a vinculação com o bebê, pode contribuir para uma compreensão mais aprofundada dos determinantes e, consequentemente, incentivo desse apoio durante a gestação. Também sugerimos a utilização de outros instrumentos psicométricos para reduzir vieses de memória e ampliar a compreensão dos fenômenos estudados, como, por exemplo, a avaliação da percepção atual da mulher sobre seus vínculos parentais e a qualidade da relação conjugal. Assim, embora as relações entre a vinculação primária e o AMF tenham sido exploradas, novos estudos devem aprofundar-se nos mecanismos subjacentes por meio dos quais essas relações operam e se mantêm (e.g., crenças, esquemas, apego adulto). Cabe ressaltar que os resultados aqui apresentados devem ser interpretados à luz das características específicas da amostra e do local de coleta e não são generalizáveis para toda a população, conforme discutido anteriormente com base na literatura científica.

Referências:

Altenburger, L. E. (2022). Similarities and differences between coparenting and parental gatekeeping: implications for father involvement research. Journal of Family Studies, 29(3), 1403-1427. https://doi.org/10.1080/13229400.2022.2051725

Alves, T. O., Nunes, R. L. N., de Sena, L. H. A., Alves, F. G., de Souza, A. G. S., Salviano, A. M., Oliveira, B. R. D., Silva, D. I. de S., Lopes, L. M., Silva, V. D., de Almeida, L. P., Oliveira, R. D., de Jesus, E. C. P., Ruas, S. J. S., Santos, M. A., Pereira, Z. A. S., & Dias, J. L. C. (2021). Gestação de alto risco: epidemiologia e cuidados, uma revisão de literatura. Brazilian Journal of Health Review, 4(4), 14860–14872. https://doi.org/10.34119/bjhrv4n4-040

Balle, R. E. (2017). Apego Materno-Fetal e Vínculos Parentais em Gestantes. (Dissertação de Mestrado, Universidade do Vale do Rio dos Sinos). Repositório Digital da Biblioteca da Unisinos. http://www.repositorio.jesuita.org.br/handle/UNISINOS/6832

Baumrind, D. (1966). Effects of authoritative parental control on child behavior. Child Development, 37(4), 887-907. https://doi.org/10.2307/1126611

Bhide, S., Sciberras, E., Anderson, V., Hazell, P., & Nicholson, J. M. (2019). Association between parenting style and socio-emotional and academic functioning in children with and without ADHD: A community-based study. Journal of Attention Disorders, 23(5), 463-474. https://doi.org/10.1177/1087054716661420

Cabrera, N. J., Volling, B. L., & Barr, R. (2018). Fathers are parents, too! Widening the lens on parenting for children’s development. Child Development Perspectives, 12(3), 152-157. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12275

Campbell, C. G. (2022). Two decades of coparenting research: A scoping review. Marriage & Family Review, 59(6), 379-411. https://doi.org/10.1080/01494929.2022.2152520

Çelik, F. P., & Güneri, S. E. (2020). The relationship between adaptation to pregnancy and prenatal attachment in high-risk pregnancies. Psychiatria Danubina, 32(Suppl 4), 568-575. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/33212465/

Cerqueira, S. A., Reis, H. L., Nogueira, K. C., Coelho, T. J., & Manfroi, E. C. (2023). Apego materno-fetal em gestantes de alto risco: uma revisão integrativa. Psicologia Argumento, 41(115). https://doi.org/10.7213/psicolargum.41.115.AO14

Cheraghi, P., & Jamshidimanesh, M. (2022). Relationship between maternal-fetal attachment with anxiety and demographic factors in high-risk pregnancy primipara women. Iran Journal of Nursing, 34(134), 46-59. https://doi.org/10.32598/ijn.34.6.4

Cohen, J. (1992). Statistical power analysis. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 1(3), 98-101. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-8721.ep10768783

Cranley, M. S. (1981). Development of a tool for the measurement of maternal attachment during pregnancy. Nursing Research, 30(5), 281-284. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006199-198109000-00008

Cuijlits, I., van de Wetering, A. P., Endendijk, J. J., van Baar, A. L., Potharst, E. S., & Pop, V. J. M. (2019). Risk and protective factors for pre- and postnatal bonding. Infant Mental Health Journal, 40(6), 768-785. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21811

Diniz, E., Brandão, T., Monteiro, L., & Veríssimo, M. (2021). Father involvement during early childhood: A systematic review of the literature. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 13(1), 77-99. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12410

Ferreira, C. I. M. (2016). Estilos Parentais e Qualidade de Vida em Crianças e Jovens (Dissertação de Mestrado, Escola Superior de Educação de Viseu). Repositório Científico do Instituto Politécnico de Viseu. http://hdl.handle.net/10400.19/4495

Fraley, R. C., & Roisman, G. I. (2019). The development of adult attachment styles: four lessons. Current Opinion in Psychology, 25, 26-30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.02.008

Fukui, N., Motegi, T., Watanabe, Y., Hashijiri, K., Tsuboya, R., Ogawa, M., Sugai, T., Egawa, J., Enomoto, T., & Someya, T. (2021). Perceived parenting before adolescence and parity have direct and indirect effects via depression and anxiety on maternal-infant bonding in the perinatal period. Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences, 75(10), 312-317. https://doi.org/10.1111/pcn.13289

Gadelha, I. P., Aquino, P. S., Balsells, M. M. D., Diniz, F. F., Pinheiro, A. K. B., Ribeiro, S. G., & Castro, R. C. M. B. (2020). Quality of life of high risk pregnant women during prenatal care. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 73(Suppl 5), e20190595. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-7167-2019-0595

Gioia, M. C., Cerasa, A., Muggeo, V. M. R., Tonin, P., Cajiao, J., Aloi, A., Martino, I., Tenuta, F., Costabile, A., & Craig, F. (2023). The relationship between maternal-fetus attachment and perceived parental bonds in pregnant women: Considering a possible mediating role of psychological distress. Frontiers in Psychology, 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.1095030

Göbel, A., Barkmann, C., Arck, P., Hecher, K., Schulte-Markwort, M., Diemert, A., & Mudra, S. (2019). Couples' prenatal bonding to the fetus and the association with one's own and partner's emotional well-being and adult romantic attachment style. Midwifery, 79, 102549. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.midw.2019.102549

Gomide, P. I. C. (2006). Inventário de Estilos Parentais. Modelo teórico: manual de aplicação, apuração e interpretação. Vozes.

Gonzalez, J., Klein, C., Barnett, M., Schatz, N., Garoosi, T., Chacko, A., & Fabiano, G. (2023). Intervention and implementation characteristics to enhance father engagement: A systematic review of parenting interventions. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 26, 3. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-023-00430-x

Grossmann, K., Grossmann, K. E., Kindler, H., & Zimmermann, P. (2008). A wider view of attachment and exploration: The influence of mothers and fathers on the development of psychological security from infancy to young adulthood. Em J. Cassidy & P. R. Shaver (Eds.), Handbook of attachment: Theory, research, and clinical applications (2nd ed., pp. 857–879). The Guilford Press.

Handelzalts, J. E., Preis, H., Rosenbaum, M., Gozlan, M., & Benyamini, Y. (2018). Pregnant women’s recollections of early maternal bonding: Associations with maternal-fetal attachment and birth choices. Infant Mental Health Journal, 39(5), 511-521. https://doi.org/10.1002/imhj.21731

Henry, J. B., Julion, W. A., Bounds, D. T., & Sumo, J. (2020). Fatherhood matters: An integrative review of fatherhood intervention research. The Journal of School Nursing, 36(1), 19-32. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059840519873380

Hinesley, J., Amstadter, A., Sood, A., Perera, R. A., Ramus, R., & Kornstein, S. (2020). Adverse childhood experiences, maternal/fetal attachment, and maternal mental health. Women's Health Reports, 1(1), 550-555. https://doi.org/10.1089/whr.2020.0085

Karantzas, G. C., Younan, R., & Pilkington, P. D. (2023). The associations between early maladaptive schemas and adult attachment styles: A meta-analysis. Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice, 30(1), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1037/cps0000108

Lima, C. de A., Brito, M. F. S. F., Pinho, L. de., Leão, G. M. M. S., Ruas, S. J. S., & Silveira, M. F. (2022). Abbreviated version of the Maternal-Fetal Attachment Scale: Evidence of validity and reliability. Paidéia (Ribeirão Preto), 32, e3233. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-4327e3233

Lucena, A. da S., Ottati, F., & Cunha, F. A. (2019). O apego materno-fetal nos diferentes trimestres da gestação. Psicologia para América Latina, 31, 13-24.

Maccoby, E. E., & Martin, J. A. (1983). Socialization in the Context of the Family: Parent-Child Interaction. In P. H. Mussen, & E. M. Hetherington (Eds.), Handbook of Child Psychology: Vol. 4. Socialization, Personality, and Social Development (pp. 1-101). Wiley.

Martins, R. P. M. P., Nunes, S. A. N., Faraco, A. M. X., Manfroi, E. C., Vieira, M. L., & Rubin, K. H. (2014). Práticas parentais: associações com desempenho escolar e habilidades sociais. Psicologia Argumento, 32(78). https://doi.org/10.7213/psicol.argum.32.078.AO04

McNamara, J., Townsend, M. L., & Herbert, J. S. (2019). A systemic review of maternal wellbeing and its relationship with maternal fetal attachment and early postpartum bonding. PloS one, 14(7), e0220032. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0220032

Ministério da Saúde. (2016). Guia do Pré-Natal do Parceiro para Profissionais de Saúde. Brasil. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde, Departamento de Ações Programáticas Estratégicas, Coordenação Nacional de Saúde do Homem. https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/guia_pre_natal_parceiro_profissionais_saude.pdf

Mourão, L., Ferreira, M. C., & Martins, L. F. (2021). Regressão múltipla linear. Em C. Faiad, M. N. Baptista, & R. Primi (Orgs.), Tutoriais em análises de dados aplicados à psicometria (pp. 102-127). Vozes.

Nascimento, V. M. S., Reis, H. L., & Manfroi, E. C. (2022). Promovendo práticas parentais positivas: avaliação de um modelo interventivo online para pais de adolescentes. Psicologia Argumento, 40(111). https://doi.org/10.7213/psicolargum.40.111.AO07

Papalia, D. E., & Martorell, G. (2022). Desenvolvimento humano (14th ed.). AMGH.

Parker, G., Tupling, H., & Brown, L. B. (1979). A Parental Bonding Instrument. British Journal of Medical Psychology, 52(1), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8341.1979.tb02487.x

Ponti, L., Smorti, M., Ghinassi, S., & Tani, F. (2021). The relationship between romantic and prenatal maternal attachment: The moderating role of social support. International Journal of Psychology, 56(1), 143-150. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12676

Provenzi, L., Brambilla, M., Scotto di Minico, G., Montirosso, R., & Borgatti, R. (2020). Maternal caregiving and DNA methylation in human infants and children: Systematic review. Genes, Brain, and Behavior, 19(3), e12616. https://doi.org/10.1111/gbb.12616

Reed, O. (2014). The effect of maternal factors on prenatal attachment (Tese de honra de graduação, University of Redlands). Institutional Scholarly Publication and Information Repository. https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/217141226.pdf

Richter, M., Schlegel, K., Thomas, P., & Troche, S. J. (2022). Adult attachment and personality as predictors of jealousy in romantic relationships. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 861481. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.861481

Richter, P. do C., Ghedin, D. A. M., & Marin, A. H. (2018). “Por que meu filho reprova?” Estudo sobre o vínculo parental e a reprovação escolar. Educação, 43(3), 499-520. https://doi.org/10.5902/1984644423703

Rocha, A. C., Reis, H. L., Sampaio, M. L., & Manfroi, E. C. (2022). O estar em UTI neonatal: percepções dos pais sobre a vivência da hospitalização e a assistência psicológica recebida na unidade. Contextos Clínicos, 15(3). https://doi.org/10.4013/ctc.2022.153.05

Rodrigues, A. R. M., Dantas, S. L. C., Pereira, A. M. M., Silveira, M. A. M., & Rodrigues, D. P. (2017). Gravidez de alto risco: análise dos determinantes de saúde. SANARE-Revista de Políticas Públicas, 16, 23-28.

Rollè, L., Giordano, M., Santoniccolo, F., & Trombetta, T. (2020). Prenatal attachment and perinatal depression: A systematic review. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(8), 2644. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17082644

Rosa, K. M., Scholl, C. C., Ferreira, L. A., Trettim, J. P., da Cunha, G. K., Rubin, B. B., Martins, R. D. L., Motta, J. V. D. S., Fogaça, T. B., Ghisleni, G., Pinheiro, K. A. T., Pinheiro, R. T., Quevedo, L. A., & de Matos, M. B. (2021). Maternal-fetal attachment and perceived parental bonds of pregnant women. Early Human Development, 154, 105310. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.earlhumdev.2021.105310

Sacchi, C., Miscioscia, M., Visentin, S., & Simonelli, A. (2021). Maternal-fetal attachment in pregnant Italian women: Multidimensional influences and the association with maternal caregiving in the infant’s first year of life. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth, 21(1), 488. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12884-021-03964-6

Santana, C. V. N., & Souza, R. P (2018). Epigenética e desenvolvimento humano. Em D. M. Miranda & L. F. Malloy Diniz (Eds.), O pré-escolar (3rd ed., pp. 23-31). Hogrefe.

Schmidt, E. M., Décieux, F., Zartler, U., & Schnor, C. (2023). What makes a good mother? Two decades of research reflecting social norms of motherhood. Journal of Family Theory & Review, 15(1), 57-77. https://doi.org/10.1111/jftr.12488

Selcuk, E., Ascigil, E., & Gunaydin, G. (2024). A theoretical analysis and empirical agenda for understanding the socioecology of adult attachment. European Review of Social Psychology, 1-34. https://doi.org/10.1080/10463283.2024.2367894

Soares, B., Vivian, A. G. V., & Sommer, J. A. P. (2022). Apego materno-fetal, ansiedade e depressão na gestação de alto risco. Concilium, 22(2), 36-49. https://doi.org/10.53660/CLM-086-108

Suryaningsih, E. K., Gau, M. L., & Wantonoro, W. (2020). Concept analysis of maternal-fetal attachment. Belitung Nursing Journal, 6(5), 157-164. https://doi.org/10.33546/bnj.1194

Teixeira, M., Raimundo, F., & Antunes, C. (2016). Relation between maternal-fetal attachment and gestational age and parental memories. Revista de Enfermagem Referência, IV Série, 85-92. https://doi.org/10.12707/RIV15025

Teodoro, M. L. M., Benetti, S. P. da C., Schwartz, C. B., & Mônego, B. G. (2010). Propriedades psicométricas do Parental Bonding Instrument e associação com funcionamento familiar. Avaliação Psicológica, 9(2), 243-251.

Topan, A., Kuzlu Ayyıldız, T., Sahin, D., Kilci Erciyas, Ş., & Gultekin, F. (2022). Evaluation of mother-infant bonding status of high-risk pregnant women and related factors. Clinical and Experimental Health Sciences, 12(1), 26-31. https://doi.org/10.33808/clinexphealthsci.766888

Trombetta, T., Giordano, M., Santoniccolo, F., Vismara, L., Della Vedova, A. M., & Rollè, L. (2021). Prenatal attachment and parent-to-infant attachment: A systematic review. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 620942. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.620942

van Bussel, J. C., Spitz, B., & Demyttenaere, K. (2010). Reliability and validity of the Dutch version of the maternal antenatal attachment scale. Archives of Women's Mental Health, 13(3), 267-277. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-009-0127-9

Vieira, A. F., & Aguiar, R. S. (2021). Benefícios para a gestante com a participação paterna no pré-natal: Uma revisão integrativa. Saúde Coletiva (Barueri), 11(68), 7375-7386. https://doi.org/10.36489/saudecoletiva.2021v11i68p7375-7386

Weber, L. N. D. (2017). Relações entre práticas educativas parentais percebidas e a autoestima, sinais de depressão e o uso de substâncias por adolescentes. Revista INFAD de Psicología. International Journal of Developmental and Educational Psychology, 2(1), 157-168. https://doi.org/10.17060/ijodaep.2017.n1.v2.928

Wendt, G. W., & Appel-Silva, M. (2020). Práticas parentais e associações com autoestima e depressão em adolescentes. Pensando famílias, 24(1), 224-238.

Yarcheski, A., Mahon, N. E., Yarcheski, T. J., Hanks, M. M., & Cannella, B. L. (2009). A meta-analytic study of predictors of maternal-fetal attachment. International Journal of Nursing Studies, 46(5), 708-715. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijnurstu.2008.10.013

Disponibilidade de dados: O conjunto de dados que embasa os resultados deste estudo não está disponível.

Como citar: Lima Reis, H., Cardoso Nogueira, K., Manfroi, E. C., & Pereira Gonçalves, A. (2024). Percepção do vínculo parental e variáveis associadas ao apego materno-fetal na gestação de alto risco. Ciencias Psicológicas, 18(2), e-3598. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v18i2.3598

Contribuição de autores (Taxonomia CRediT): 1. Conceitualização; 2. Curadoria de dados; 3. Análise formal; 4. Aquisição de financiamento; 5. Pesquisa; 6. Metodologia; 7. Administração do projeto; 8. Recursos; 9. Software; 10. Supervisão; 11. Validação; 12. Visualização; 13. Redação: esboço original; 14. Redação: revisão e edição.

H. L. R. contribuiu em 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14; K. C. N. em 1, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 13, 14; E. C. M. em 1, 3, 4, 6, 7, 8, 10, 12, 14; A. P. G. em 2, 3, 6, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14.

Editora científica responsável: Dra. Cecilia Cracco.

10.22235/cp.v18i2.3598

Original Articles

Perceived parental bonding and variables associated with maternal-fetal attachment in high-risk pregnancy

Percepção do vínculo parental e variáveis associadas ao apego materno-fetal na gestação de alto risco

Percepción del vínculo parental y variables asociadas al apego materno-fetal en embarazos de alto riesgo

Henrique Lima Reis1, ORCID 0000-0001-7591-2010

Ketylen Cardoso Nogueira2, ORCID 0009-0003-8980-0564

Edi Cristina Manfroi3, ORCID 0000-0003-2375-1205

André Pereira Gonçalves4, ORCID 0000-0002-2470-4040

1 Universidade Federal de Santa Catarina, Brazil, [email protected]

2 Universidade Federal da Bahia, Brazil

3 Universidade Federal da Bahia, Brazil

4 Universidade Federal da Bahia, Brazil

Abstract:

This study investigated the effects of perceived parental bonding, sociodemographic and gestational variables on the intensity of maternal-fetal attachment (MFA) in the context of high-risk pregnancies. This is a quantitative, cross-sectional study involving 119 participants. A sociodemographic questionnaire, the Maternal-Fetal Attachment Scale-Brief Version, and the Parental Bonding Instrument were administered. The results of the multiple linear regression analysis were statistically significant (p < .05). The final model explained 28.7 % of the variance in MFA and included the variables of paternal overprotection, paternal care, maternal age, gestational age, and the support from the baby's father. We emphasize that MFA intensity is multidetermined, involving aspects of life history, social, and situational factors. The woman’s perception of paternal bonding during her childhood and adolescence, as well as the support from the baby's father during the gestational period, are highlighted as influential factors for maternal-fetal attachment, indicating the importance of paternal involvement throughout the life cycle. Implications for professional practice, as well as limitations and recommendations for future studies are discussed.

Keywords: maternal-fetal relations; high-risk pregnancy; family relations; pregnancy.

Resumo:

Este estudo investigou os efeitos da percepção do vínculo parental, variáveis sociodemográficas e gestacionais na intensidade do apego materno-fetal (AMF) no contexto de gestação de alto risco. Trata-se de um estudo quantitativo e transversal com 119 participantes. Foi aplicado um questionário sociodemográfico, a Escala de Apego Materno-Fetal - Versão Breve e o Parental Bonding Instrument. Os resultados da análise de regressão linear múltipla foram estatisticamente significativos (p < 0,05). O modelo final explicou 28,7 % da variância do AMF e foi composto pelas variáveis de superproteção paterna, cuidado paterno, idade da mulher, idade gestacional e suporte do pai do bebê. Reitera-se que a intensidade do AMF é multideterminada, envolvendo aspectos da história de vida, sociais e situacionais. A percepção da mulher acerca do vínculo paterno durante sua infância e adolescência e o apoio do pai do bebê no período gestacional destacam-se como fatores influentes para a vinculação materno-fetal, indicando a importância do envolvimento paterno ao longo do ciclo vital. São pontuadas implicações para a prática profissional, bem como limitações e recomendações de estudos futuros.

Palavras-chave: relações materno-fetais; gravidez de alto risco; relações familiares; gestação.

Resumen:

Este estudio investigó los efectos de la percepción del vínculo parental, las variables sociodemográficas y gestacionales en la intensidad del apego materno-fetal (AMF) en el contexto de embarazos de alto riesgo. Se trata de un estudio cuantitativo y transversal con 119 participantes. Se aplicó un cuestionario sociodemográfico, la Escala de Apego Materno-Fetal-Versión Breve y el Instrumento de Vínculo Parental. Los resultados del análisis de regresión lineal múltiple fueron estadísticamente significativos (p < .05). El modelo final explicó el 28.7 % de la varianza del AMF y estuvo compuesto por las variables de sobreprotección paterna, cuidado paterno, edad de la mujer, edad gestacional y apoyo del padre del bebé. Se reitera que la intensidad del AMF es multideterminada, lo que involucra aspectos de la historia de vida, sociales y situacionales. La percepción de la mujer sobre el vínculo paternal durante su infancia y adolescencia, así como el apoyo del padre del bebé durante el período gestacional, destacan como factores influyentes en el apego materno-fetal, lo que indica la importancia de la participación paterna a lo largo del ciclo vital. Se puntualizan implicaciones para la práctica profesional, así como limitaciones y recomendaciones para estudios futuros.

Palabras clave: relación materno-fetal; embarazo de alto riesgo; relaciones familiares; embarazo.

Received: 26/07/2023

Accepted: 23/09/2024

Pregnancy is a natural process of human development that involves physical, hormonal, emotional, and social changes for the pregnant woman, which necessitate a restructuring of identity and an adaptation to new parental roles (Papalia & Martorell, 2022). Beyond attitudes and behaviors evolutionarily selected to ensure the survival of offspring and, ultimately, the species, the mother-baby relationship encompasses particular aspects of her internal world and evokes pre-pregnancy experiences, such as the care received in childhood and parental models (Balle, 2017; Trombetta et al., 2021). This relationship begins during intrauterine life, as throughout the gestational period, the baby is impacted by the external world and the mother's experiences (Lucena et al., 2019; Rosa et al., 2021).

Although most pregnancies occur without major complications, about 20 % of women in Brazil experience comorbidities and risks during this period (Alves et al., 2021). High-risk pregnancy occurs when the gestational process poses risks to the health of the mother and/or the fetus, and certain factors can increase the likelihood of its occurrence (Gadelha et al., 2020). Risk factors are related to individual characteristics, unfavorable sociodemographic conditions, previous reproductive history, obstetric diseases in the current pregnancy, and clinical complications (Rodrigues et al., 2017). These aspects can trigger stress and negatively affect the mental health of the pregnant woman, potentially impacting the bonding process with the baby and consequently leading to impairments in the child's development, as well as difficulties in the process of adapting to motherhood (Topan et al., 2022).

Considering the importance of mother-infant bonding for healthy development, Cranley (1981) defined the attachment/bond established by the mother toward the fetus as "maternal-fetal attachment" (MFA). It is characterized by the intensity of the woman's attitudes during pregnancy related to the establishment of a bond and closeness with the fetus, involving cognitive and affective aspects, as well as her attributions regarding the fetus's physical and emotional characteristics (Suryaningsih et al., 2020; Trombetta et al., 2021). The development of MFA is an important component in the process of forming and adapting to motherhood, potentially influencing the pregnancy experience and the quality of the mother-child relationship after birth (Ponti et al., 2021; Sacchi et al., 2021).

Review studies indicate that MFA functions as a predictor of healthy emotional, behavioral, cognitive, and social development in early childhood, and that mothers who developed stronger MFA tend to be less self-critical, more engaged in healthy behaviors during pregnancy, and less vulnerable to negative psychological symptoms (Rollè et al., 2020; Trombetta et al., 2021). MFA is also associated with a greater perception of competence regarding parental care in the postpartum period, increased maternal sensitivity in identifying the newborn's needs, and better adaptation to motherhood (Çelik & Güneri, 2020; Göbel, 2019).

The development of maternal-fetal attachment is multidimensional, influenced by socioeconomic variables, the quality of the marital relationship, the pregnant woman's education, gestational age, and social support (Cheraghi & Jamshidimanesh, 2022; Sacchi et al., 2021; Topan et al., 2022). Review studies highlight social support (from family and partner) as an important contextual variable in determining the intensity of MFA, with greater perceived support being associated with stronger maternal-fetal bonding and a smoother transition to motherhood (Cerqueira et al., 2023; Yarcheski et al., 2009). However, another determining factor is the pregnant woman's own attachment history with her caregivers. This is a foundational aspect of personality, contributing to the development of internal functioning modes (mental representations or beliefs that guide an individual’s perception and behavior) and to her attitudes toward parental care (Gioia et al., 2023; Rosa et al., 2021).

According to Attachment Theory, the quality and dynamics of the relationship established with primary caregivers, especially during childhood and adolescence, contribute to the formation of internal working models. These are mental representations the child creates about the environment, themselves, and relationships (Karantzas et al., 2023). Such models evolve with the child's development and begin to function as guides for interpreting events and relationships throughout life, thereby integrating into their personality (Fraley & Roisman, 2019; Selcuk et al., 2024). As they involve both affective and cognitive aspects, they tend to have a strong impact on interpersonal relationships, attachment processes, self-construction, and the exercise of parenthood (Richter et al., 2022; Sacchi et al., 2021). During pregnancy, it is common for women to revisit memories and perceptions of their attachment to parental figures. This process may influence how they perceive themselves as mothers and their closeness to the child, with the possibility of reworking and assigning new meanings to these memories during pregnancy (Balle, 2017; Handelzalts et al., 2018; Hinesley et al., 2020).

Although attachment theory proposes that the quality and intensity of primary attachment influence other bonds throughout life, there are still few empirical studies that have sought to evaluate the relationships between primary attachment and MFA, especially in the context of high-risk pregnancies (Cerqueira et al., 2023; Handelzalts et al., 2018; Sacchi et al., 2021). Cerqueira et al. (2023) conducted a review study aimed at investigating the scientific literature on MFA in high-risk pregnancies and emphasized the need for research that also considers the pregnant woman's attachment history as an influential factor, highlighting the absence of studies with this objective and population, particularly in the Brazilian context. Furthermore, in a literature review over the last 13 years conducted by the authors of the present study, only ten studies were found relating primary attachment to maternal-fetal attachment. Of these, only two (Balle, 2017; Handelzalts et al., 2018) included high-risk pregnant women in their sample. However, no group comparisons or distinct analyses considering gestational risk were conducted, making it impossible to assess whether the relationships between variables and outcomes behave similarly in both conditions.

Two studies found were conducted in Brazil (Balle, 2017; Rosa et al., 2021). In a study with 839 pregnant women without gestational risk, Rosa et al. (2021) investigated the explanatory power of sociodemographic, gestational, and primary attachment variables (using the Parental Bonding Instrument, PBI) in the intensity of MFA through regression analyses. Pregnant women in their first trimester, who were not living with a partner and who did not feel supported by the baby’s father during pregnancy showed lower MFA scores. However, after controlling for these variables, paternal overprotection was a positive predictor of MFA, while the other primary attachment dimensions (Maternal and Paternal Care and Maternal Overprotection) did not show statistically significant relationships. It is worth noting that all study participants exhibited high levels of MFA, regardless of their perception of parental attachment, indicating that during pregnancy, a woman may bond with her baby even without positive childhood memories.

Still in the Brazilian context, Balle (2017) conducted a study with 364 pregnant women, of whom 14 % were considered high risk, to identify the relationships between MFA and sociodemographic variables, prenatal care, and the care factor of the PBI. In a correlation analysis, the author found a positive but weak association only with maternal care. Through regression analysis, this same factor explained 5.1% of the variance in MFA. Although it did not indicate a significant association between high-risk pregnancies and maternal-fetal attachment, this variable was positively related to gestational age and negatively related to the mother's age.

In a longitudinal study with 1,301 pregnant women without gestational risk, Fukui et al. (2021) investigated the relationships between primary attachment (PBI), maternal-fetal attachment, and indicators of mental health. Through path analysis, they indicated that the perception of low maternal and paternal care negatively affected the bond with the baby, and this effect persisted after childbirth. However, the authors did not discuss the possible effects of sociodemographic (e.g., age) or gestational variables (e.g., primiparity and gestational age) on these relationships. In contrast, Gioia et al. (2023), using a sample of 1,177 pregnant women and regression analyses, indicated that gestational age, primiparity, and perceptions of paternal and maternal care (assessed through the PBI) were statistically significant predictors of maternal-fetal attachment. It is worth noting that this relationship was not mediated by indicators of mental health (e.g., anxiety and depression), suggesting direct effects. Van Bussel et al. (2010) reported similar results based on positive but weak correlations between paternal care and MFA in a sample of 403 pregnant women. No significant relationships were found with other sociodemographic or gestational variables.

Sacchi et al. (2021) investigated the association between MFA, mental health, marital relationship, and maternal primary attachment using a sample of 113 low-risk pregnant women. Through correlation and regression analyses, maternal care was positively related to MFA, as was the quality of the marital relationship. The authors indicated that the pregnant woman's past and current relationships serve as models for her maternal representations regarding her relationship with the baby, impacting the attachment. In agreement, Handelzalts et al. (2018) also found a positive correlation between MFA and maternal care in a study with 341 pregnant women, 17.4 % of whom were in high-risk pregnancies. However, when regression analysis was conducted, women with high scores in the Care and Denial of Autonomy factors of maternal attachment also exhibited stronger MFA. Other factors associated with greater intensity of MFA included younger age, lower education, and fewer previous births. In the study, no significant associations were found between high-risk conditions and maternal-fetal attachment.

In a study with 101 pregnant women, Hinesley et al. (2020) investigated the impact of exposure to adverse childhood experiences on maternal variables such as primary attachment, MFA, and mental health through path analysis. Regarding MFA, positive direct relationships were identified only with paternal care and the age of the pregnant woman. No direct associations were found between adverse experiences (e.g., neglect and coercion) in childhood and MFA. However, the low perception of paternal care explained part of the negative indirect effect of these adverse experiences on MFA. Concerning primary attachment, high exposure to adverse events in childhood was negatively associated with the perception of paternal and maternal care and was a significant predictor of perceiving both parents as intrusive and controlling.

The study by Teixeira et al. (2016) analyzed the relationship between MFA, gestational age, and memories of parenting practices (using the Memories of Parenting Practices Scale, EMBU) in 179 pregnant women. Through correlation analyses, it was found that perceived rejection by both the father and the mother is associated with lower MFA, specifically with a decreased identification of the pregnant woman as a future mother. The authors also reported a positive association between gestational age and MFA. Finally, in examining the relationship between maternal factors and prenatal attachment in a sample of 32 pregnant women, Reed (2014) identifies the combination of lower care and greater overprotection from the primary caregiver, whether the mother or the father, as a risk factor for lower maternal-fetal attachment, particularly in pregnant women with low educational attainment. Furthermore, using analysis of variance (ANOVA), pregnant women who reported high social support, lack of religious affiliation, low anxiety, and low dependence in current adult relationships demonstrated higher MFA.