10.22235/cp.v18i2.3385

Habilidades ejecutivas: actualización, cambio entre conjuntos mentales e inhibición en niños no mapuche urbanos, mapuche urbanos y mapuche rurales de La Araucanía, Chile

Executive functions: updating, set-shifting, and inhibition in non-Mapuche urban children, Mapuche urban children, and rural Mapuche children in La Araucanía, Chile

Habilidades executivas: atualização, mudanças entre conjuntos mentais e inibição em crianças não mapuches urbanas, mapuches urbanas e mapuches rurais de La Araucanía, Chile

Rebeca Muñoz Sanhueza1, ORCID 0000-0002-4393-1820

Paula Alonqueo Boudon2, ORCID 0000-0002-4582-1262

1 Universidad Católica de La Santísima Concepción, Chile, [email protected]

2 Universidad de La Frontera, Chile

Resumen:

Las habilidades cognitivas de los niños varían conforme a los contextos de desarrollo cultural en los que se desenvuelven. Asumiendo la variabilidad cultural, este estudio tuvo por objetivo comparar las habilidades ejecutivas en 110 niños, entre 9 y 11 años, pertenecientes a tres grupos: no mapuche urbanos, mapuche urbanos y mapuche rurales, de comunas de la región de La Araucanía, Chile. Se usó un diseño descriptivo y correlacional para contrastar el desempeño de los niños en las variables de interés. La batería de instrumentos estuvo formada por tres pruebas que evaluaron: actualización, cambio entre conjuntos mentales e inhibición, respectivamente. Los resultados indican que no hubo diferencias estadísticamente significativas en actualización y cambio entre conjuntos mentales, pero sí hubo significancia estadística para las diferencias en inhibición; siendo los niños no mapuche quienes tuvieron mayor inhibición respecto de los otros dos grupos. Se discuten los hallazgos según la hipótesis de que el desarrollo de habilidades se relaciona con las prácticas cotidianas, demandas y características sociodemográficas de los contextos en los que los niños se desarrollan.

Palabras clave: contextos culturales; diferencias culturales; habilidades ejecutivas; niños mapuche; cultura; Chile.

Abstract:

Children's cognitive abilities differ according to the cultural development settings in which they are raised. Assuming cultural variability, this study compared the executive functions in 110 children, aged 9 to 11 years, belonging to three groups: urban non-Mapuche, urban Mapuche, and rural Mapuche, from communes in the Araucanía region, Chile. A descriptive and correlational design was used to contrast children's performance on the variables of interest. The battery of instruments comprised three tests that assessed updating, set-shifting, and inhibition, respectively. The results indicate no statistically significant differences in updating and set-shifting, but there was a statistical significance for differences in inhibition, with non-Mapuche children having greater inhibition than the other two groups. The findings are discussed according to the hypothesis that skill development is related to the daily practices, demands, and sociodemographic characteristics of the settings in which children are raised.

Keywords: cultural contexts; cultural differences; executive functions; Mapuche children; culture; Chile.

Resumo:

As habilidades cognitivas das crianças variam conforme os contextos de desenvolvimento cultural em que elas se desenvolvem. Partindo do pressuposto da variabilidade cultural, este estudo teve como objetivo comparar as habilidades executivas de 110 crianças, com idades entre 9 e 11 anos, pertencentes a três grupos: não mapuche urbanas, mapuche urbanas e mapuche rurais, de municípios da região de La Araucanía, Chile. Foi utilizado um desenho descritivo e correlacional para comparar o desempenho das crianças nas variáveis de interesse. A bateria de instrumentos foi composta por três testes que avaliaram: atualização, mudança entre conjuntos mentais e inibição, respectivamente. Os resultados indicam que não houve diferença estatisticamente significativa em atualização e mudança entre conjuntos mentais, mas houve significância estatística para as diferenças em inibição, com as crianças não mapuches apresentando maior inibição do que os outros dois grupos. Os resultados são discutidos de acordo com a hipótese de que o desenvolvimento de habilidades está relacionado às práticas cotidianas, demandas e características sociodemográficas dos contextos em que as crianças se desenvolvem.

Palavras-chave: contextos culturais; diferenças culturais; habilidades executivas; crianças mapuches; cultura; Chile.

Recibido: 28/12/2023

Aceptado: 05/07/2024

El funcionamiento ejecutivo es un constructo multidimensional que engloba una serie de procesos cognitivos de orden superior necesarios para realizar tareas dirigidas hacia una meta (Diamond, 2013; Lehto et al., 2003). Para Lezak (1982) —a quien se le atribuye el término de función ejecutiva (FE)—, el funcionamiento ejecutivo incluye habilidades cognitivas de alto nivel para formular objetivos, planificar cómo alcanzarlos y ejecutarlos eficazmente, lo que impacta en el comportamiento y las habilidades sociales. Las habilidades ejecutivas son dependientes del córtex prefrontal dorsolateral y comienzan a desarrollarse desde los seis meses de edad hasta la adultez (Diamond, 2002). Durante la infancia aumentan el desempeño ejecutivo a medida que el cerebro madura, lo que permite la regulación del pensamiento, acciones y emociones. No obstante, debido a la maduración incompleta de los lóbulos frontales se ven limitadas en esta etapa (Anderson et al., 2001). En la niñez las habilidades ejecutivas transitan de lo fácil a lo complejo para progresivamente alcanzar mayor flexibilidad y adaptación a eventos inesperados y superar las acciones en “piloto automático” (Diamond, 2013). En la adolescencia se alcanza una capacidad ejecutiva similar a la observada en la adultez (García-Molina et al., 2009).

Varias investigaciones han encontrado que la edad (como indicador del grado de maduración) es un factor explicativo del rendimiento ejecutivo: a mayor edad son más altas las puntuaciones en las habilidades ejecutivas (Ardila et al., 2005; Bausela, 2014), aunque el aumento en los puntajes puede depender del tipo de medida utilizada. Por ejemplo, Anderson et al. (2001) en un estudio realizado con 138 niños de 11 a 17 años encontraron que la trayectoria de desarrollo para el funcionamiento ejecutivo fue relativamente plana durante la infancia tardía y la adolescencia temprana. Este estudio muestra la necesidad de evaluar la progresión de las habilidades ejecutivas en diferentes edades por medio de una amplia batería de tareas con un enfoque de variables latentes, en lugar de una única prueba que no precisamente demuestra un nivel de procesamiento cognitivo complejo con cambios más marcados en el rendimiento a lo largo de los años (Anderson et al., 2001; Lehto et al., 2003; Obradovic & Willoughby, 2019).

El conjunto de habilidades que constituye el funcionamiento ejecutivo varía entre diferentes autores, pero existe consenso en que son tres los componentes fundamentales: actualización y seguimiento de las representaciones de la memoria de trabajo (actualización de ahora en adelante), cambio entre conjuntos mentales o tareas e inhibición de respuestas dominantes (control inhibitorio que incluye el autocontrol y el control de interferencia) (Lehto et al., 2003; Miyake et al., 2000). Estas habilidades ejecutivas pueden definirse operativamente de manera más precisa que otras y las tres probablemente estén implicadas en el desempeño de habilidades ejecutivas convencionales más complejas (Diamond, 2013; Miyake et al., 2000). Por ejemplo, el Test de los Cinco Dígitos se sugiere como una prueba que mide el cambio de conjuntos para cambiar entre principios de clasificación, así como de inhibición para suprimir respuestas inapropiadas (Sedó, 2007).

La actualización es la capacidad de retener información con el propósito de cumplir una tarea, siendo una habilidad crítica para el razonamiento (Lehto et al., 2003). Permite reordenar y trabajar con datos mentalmente para actualizarlos mientras se llevan a cabo tareas relacionadas con esos datos (Carpendale & Lewis, 2006; Diamond, 2013). El cambio entre conjuntos mentales o tareas es la capacidad de cambiar una manera de resolver un problema por otra con la finalidad de responder adecuadamente a una situación (Lewis & Carpendale, 2009). Requiere desplazar el foco atencional de una clase de estímulos a otra distinta y alternar entre dos conjuntos cognitivos (van der Linden et al., 2000). Esta habilidad permite generar ideas diferentes, considerar alternativas de comportamientos y responder a situaciones nuevas, por lo que resulta relevante para la regulación de la conducta y si presenta disminución puede producir un comportamiento rígido e inflexible (Diamond, 2002). Por último, la inhibición se define como “la capacidad de inhibir deliberadamente las respuestas dominantes, autónomas o preponderantes” (Miyake et al., 2000, p. 57). Está constituida por el control inhibitorio y el autocontrol: el control inhibitorio posibilita suprimir las reacciones salientes (Lewis & Carpendale, 2009), mientras que el autocontrol permite dominar el propio desempeño para cerciorarse de que la meta se haya alcanzado apropiadamente (Lehto et al., 2003). En suma, la inhibición permite una adecuada autorregulación, motivación para ejecutar acciones y desarrollar el control emocional (García-Molina et al., 2009).

La mayoría de las investigaciones que establecen diferencias en las habilidades ejecutivas infantiles se han desarrollado con poblaciones occidentales de clase media y, además, han utilizado tareas que incluyen una variedad de habilidades de orden inferior (por ejemplo, capacidad de lectura, lenguaje expresivo y receptivo, entre otras), por lo que la inexperiencia en estas capacidades podría provocar una puntuación general baja en las pruebas de funcionamiento ejecutivo en ausencia de déficits cognitivos (Anderson et al., 2001). Esta manera de evaluar las habilidades descuida la importancia de los factores socioculturales que sustentan un desarrollo divergente del funcionamiento ejecutivo (Gaskins & Alcalá, 2023). Los instrumentos, al no evaluar todos los componentes del dominio ejecutivo, pueden carecer de validez ecológica en grupos culturalmente diversos (Gioia et al., 2000; Miller-Cotto et al., 2022).

En consideración de lo anterior, surge como un imperativo conocer las características del contexto de desarrollo del niño para la evaluación de las habilidades ejecutivas, puesto que las prácticas culturales y las demandas sociales-familiares condicionan el desarrollo de las capacidades cognitivas (Carpendale & Lewis, 2006) y, a su vez, potencian ciertas habilidades ejecutivas por sobre otras (Gaskins & Alcalá, 2023; Georgas et al., 2003). Es decir, los procesos psicológicos emergen de la participación en prácticas mediadas y construidas cultural e históricamente (Rogoff et al., 2018).

Esta perspectiva cultural posibilita superar la visión normativa y estándar de las habilidades infantiles (Hein et al., 2015; Rogoff & Mejía-Arauz, 2022). Las diferencias en las habilidades no ocurren por una carencia de rasgos universales, sino por la adaptación de las predisposiciones del desarrollo ejecutivo a las prácticas específicas de los diversos contextos culturales (Keller & Kärtner, 2013; Stucke et al., 2022). De este modo, suponer que la comparación entre niños que viven en entornos culturales extremadamente diversos debería presentar un mismo patrón de desarrollo resulta incongruente (Worthman, 2010).

Según los modelos socioecológicos del desarrollo el ambiente familiar y las características del contexto hogareño son ecologías que impactan directa o indirectamente en el aprendizaje de los niños, lo que propicia el desarrollo de habilidades cognitivas particulares (Bronfenbrenner, 1986; Worthman, 2010). En concordancia con estas ideas, Keller (2015) propuso el modelo del desarrollo ecocultural —formalizado originalmente por Whiting (1994)—, que plantea que las habilidades se desarrollan según las condiciones eco-sociales, los modelos culturales y las estrategias de socialización (Keller & Kärtner, 2013).

Los contextos eco-sociales corresponden a grupos específicos de familias y comunidades que se distinguen en función de su nivel de escolaridad formal, lugar de residencia, tipo de economía familiar y si son o no comunidades de sociedades postindustriales (Keller, 2015). El entramado de estas variables supedita el despliegue de prácticas de aprendizaje y desarrollo de habilidades específicas.

El nivel de escolarización de los cuidadores de los niños produce diferencias entre los contextos eco-sociales. El conocimiento abstracto adquirido en la escuela determina las ocupaciones laborales de los padres, y con ello el nivel socioeconómico familiar, lo que afecta a las prácticas cotidianas de los niños (Greenfield, 1996). En este sentido, las características socioeconómicas de los contextos eco-sociales fomentan prácticas específicas que posibilitan la emergencia de procesos cognitivos que, a su vez, son modulados por las exigencias de los mismos contextos (Lewis & Carpendale, 2009; Rogoff et al., 2018).

Keller (2015) propone tres contextos eco-sociales de desarrollo que en este estudio se asumen como base para distinguir tres grupos diferentes de niños: no mapuche urbano, mapuche urbano y mapuche rural.

El primer contexto está compuesto por familias de clase media occidental, no indígenas, urbanas de países posindustrializados, cuyos cuidadores tienen un nivel alto de escolaridad (12 o más años). Frecuentemente, estos tienen ocupaciones laborales calificadas en una economía de libre mercado. Son familias nucleares con pocos hijos, cuyas interacciones se basan fundamentalmente en asuntos escolares (Keller, 2019; Morelli et al., 2003). Estas familias asumen que un mejor rendimiento escolar en la niñez facilita la obtención de mejores empleos en la vida adulta (Sternberg et al., 2001). Por ello, los niños suelen ocupar su tiempo en actividades “propias de la infancia”, participando en prácticas institucionalizadas que fomentan el desarrollo de habilidades abstractas, la exploración individual, la comunicación expresiva y la conciencia reflexiva del sí mismo (Keller & Kärtner, 2013). Pareciera ser que para estas familias el objetivo final del desarrollo infantil es equivalente al logro de la escolarización (Rogoff et al., 2003).

Las familias de este contexto eco-social valoran las dinámicas escolares de sus hijos, lo que podría impactar en mayor medida en el desempeño ejecutivo de estos niños (Baker et al., 2012). El entrenamiento de estos niños en rutinas escolares podría influir notablemente en los puntajes altos de las pruebas de funcionamiento ejecutivo, especialmente en memoria visual (Ardila et al., 2005; Spiegel et al., 2021); por lo que la familiaridad con actividades escolares facilitaría un mayor rendimiento ejecutivo (Blair & Razza, 2007; Carpendale & Lewis, 2006; Jacob & Parkinson, 2015).

En Chile, los resultados de la encuesta de Actividades de Niños, Niñas y Adolescentes (EANNA) permiten identificar que este contexto eco-social está formado por familias no mapuche urbanas (Ministerio de Desarrollo Social, 2012). La composición familiar suele ser de tipo nuclear y la crianza está a cargo de una acotada red de personas, lo que podría restringir las posibilidades de los niños para participar en actividades colaborativas con otros, según la Tercera Encuesta Longitudinal de la Primera Infancia (ELPI; Ministerio de Desarrollo Social, 2017). Como resultado de un cambio en las creencias parentales que valora la escolarización temprana y el logro de la certificación de la escolaridad secundaria, los niños chilenos han dejado de ayudar en tareas domésticas (Ghiardo Soto & Dávila León, 2016). Las interacciones familiares giran en torno al rendimiento escolar, lo que implica que ellos inviertan mucho tiempo en actividades académicas y en prácticas que propician la independencia y autonomía (Urzúa et al., 2009); mientras que dedican poco tiempo (una hora semanal) para participar en la colaboración doméstica (barrer, limpiar, etc.) (Ministerio de Desarrollo Social, 2012).

Un segundo contexto eco-social de desarrollo lo componen familias urbanas de clase media, no occidentales y con herencia indígena. Esta herencia se entiende como un patrimonio de valores, creencias y prácticas —relacionadas con la identidad indígena de origen— compartidas por personas de distintas generaciones (Rogoff et al., 2003). En estas familias los padres tienen alta escolaridad y viven en ciudades como resultado de procesos migratorios desde zonas rurales, motivados por la necesidad de inserción laboral y acceso al sistema educativo formal (Cárcamo et al., 2015). Se mantiene el sentido de unión familiar, pero a la par se adquiere un sentido del yo individual (Keller, 2019), como resultado de la escolarización, la ausencia de una economía agrícola-ganadera y ocupaciones laborales fuera del hogar (Greenfield, 2009).

En Chile, las familias mapuche urbanas compartirían las características de este segundo contexto. Han migrado desde sectores rurales a causa de la usurpación de tierras por parte del Estado y particulares. La obtención de puestos laborales especializados y el acceso a instituciones escolares han sido otras causas de la migración (Imilan & Álvarez, 2017). Algunas de estas familias mantienen el contacto con sus comunidades de origen en una relación de dependencia socioespiritual entre el campo y la ciudad (Imilan & Álvarez, 2017). Tienen cierto dominio de la lengua mapuche y mantienen su identidad cultural, participando en prácticas que reúnen a la familia extensa (Becerra et al., 2018). No obstante, su rutina diaria se ha adaptado al sistema educativo chileno, que impone un modelo monocultural de adquisición de conocimiento escolar (Quilaqueo et al., 2022). Los niños deben cumplir con obligaciones escolares y, dado que los trabajos adultos no se realizan en el hogar, tienen menos oportunidades para colaborar en la familia. Las actividades diarias de los niños se realizan según la dirección de los padres, que fomentan la rapidez y eficacia de las acciones (Murray et al., 2015). Al no tener el contacto frecuente con la naturaleza, los niños aprenden en contextos simulados, lo que dificulta la exploración y manipulación de elementos en el ambiente natural (Egert & Godoy, 2008).

El último contexto eco-social está representado por familias extendidas con herencia indígena, residentes en zonas rurales, cuyos padres tienen un nivel bajo de escolaridad (ocho o menos años) (Keller & Kärtner, 2013). Esto se corresponde con un escaso contacto con centros urbanos y el mantenimiento de prácticas ancestrales (Rogoff et al., 2018). Los trabajos desempeñados por estas familias no requieren perfeccionamiento académico, pues son oficios aprendidos de generación en generación que incluyen actividades agrícolas, ganaderas y domésticas. En este contexto, los niños interactúan con personas de distintas edades y cooperan progresivamente en tareas de siembra-cosecha, cuidado de animales, confección de tejidos para vender, entre otros (Morelli et al., 2003).

La colaboración infantil se alinea con los intereses y prácticas familiares, donde predomina el logro grupal por sobre el personal (Alcalá et al., 2021). En este contexto los niños desarrollan la autorregulación, la resolución de problemas, la organización y la ejecución de metas; todas habilidades propias del funcionamiento ejecutivo (Gaskins & Paradise, 2010), aunque las mediciones estandarizadas informan que niños de comunidades indígenas obtienen bajos puntajes al recordar listas de objetos (Gauvain & Pérez, 2015). Esto puede suceder porque los reactivos de las tareas no son propios de sus contextos de desarrollo y, probablemente, estos instrumentos presenten sesgos de medición al no considerar la perspectiva contextual (LeCuyer & Zhang, 2015).

Las familias mapuche rurales corresponderían a este contexto eco-social, pues mantienen prácticas ancestrales, un sistema económico agrícola-ganadero y los niveles de escolaridad formal son bajos, en promedio de 8,2 años en La Araucanía (Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas [INE], 2019). Por ello, se puede suponer que las prácticas culturales mapuche no están tan permeadas por el conocimiento escolar. Las prácticas de crianza son compartidas en un sistema de multiparentalidad en la familia extensa, es decir, el niño está a cargo de diversos adultos, quienes respetan su ritmo de aprendizaje, evitan la supervisión constante y la instrucción verbal directa en las actividades (Cárcamo et al., 2015). Los niños mapuche rurales tienen libertad para experimentar y participar de las prácticas domésticas y comunitarias que fomentan el aprendizaje, el contacto físico y la estimulación motora gruesa (Farkas et al., 2017). Dado que el trabajo de los adultos ocurre en el hogar y que la comunidad asume que las experiencias son importantes para todos los miembros, los niños ayudan en las actividades de acuerdo con las capacidades que van adquiriendo al participar de las actividades comunitarias (Alarcón et al., 2021). La interacción con los adultos es horizontal y colaborativa, ya que los niños son considerados participantes legítimos (Alonqueo et al., 2022; Murray & Tizzoni, 2022; Szulc, 2021).

Las prácticas descritas para cada uno de los tres grupos —no mapuche urbano, mapuche urbano y mapuche rural— viabilizan el desarrollo de habilidades cognitivas adaptadas a las necesidades de cada entorno (Lewis & Carpendale, 2009). En este sentido, las habilidades ejecutivas, como proceso psicológico cultural, progresan desde lo externo y social a lo individual e interno (Vygotsky, 1997). Por ello, las habilidades se adquieren en las prácticas culturales y se perfeccionan en los contextos eco-sociales (Leontiev, 1978).

Se desconocen estudios publicados que evalúen el funcionamiento ejecutivo en los tres grupos de niños antes descritos. En general, el análisis del funcionamiento ejecutivo en niños chilenos se centra en las diferencias por el nivel socioeconómico y el nivel de escolaridad de los padres (por ejemplo, Rodríguez et al., 2019). Probablemente, los puntajes bajos de los niños con familias de entornos con poca escolaridad y nivel socioeconómico bajo se deba a que la medición se basa en habilidades potenciadas por la escuela (Blair & Razza, 2007; Georgas et al., 2003). Por esta razón es importante estudiar las habilidades ejecutivas en consideración con las prácticas y contextos de desarrollo eco-social para tener una mayor compresión de las habilidades de los niños (LeCuyer & Zhang, 2015). En este sentido, las diferencias de los tres grupos en el funcionamiento ejecutivo no deben entenderse como un “déficit” en el que se identifica a los grupos más “desfavorecidos” respecto de la carencia de habilidades (Kärtner et al., 2008). Muy por el contrario, se reconocen las diferencias conforme a un modelo teórico que admite que en cada contexto las prácticas culturales posibilitan el desarrollo variado de destrezas (Rogoff, 2014).

La pregunta de investigación que orientó este estudio fue ¿cuáles son las diferencias en las habilidades ejecutivas de niños no mapuche urbanos, mapuche urbanos y mapuche rurales de 9 a 11 años de edad? El objetivo general del estudio fue contrastar las diferencias en las habilidades ejecutivas entre niños no mapuche urbanos, mapuche urbanos y mapuche rurales de 9 a 11 años de edad.

Método

Diseño

Se utilizó un diseño descriptivo y un estudio correlacional, cuyo propósito fue describir y contrastar las habilidades ejecutivas en tres grupos de niños (Howitt & Cramer, 2011).

Participantes

En Chile, el pueblo mapuche es el pueblo indígena más numeroso con una población total superior al millón de habitantes (1.745.147; INE, 2019), de los cuales 471.742 son niños y adolescentes (Defensoría de la Niñez, 2021).

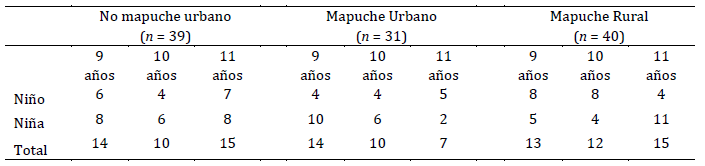

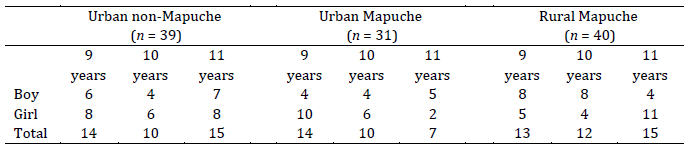

Se realizó un muestreo por conveniencia seleccionando un total de 110 niños de entre 9 y 11 años, perteneciente a tres grupos culturales: 39 niños no mapuche urbanos, 31 niños mapuche urbanos y 40 niños mapuche rurales. Tanto en el grupo rural como en el grupo urbano la pertenencia al pueblo mapuche fue determinada por autoadscripción. Se excluyeron de la muestra a niños que no cumplían con los criterios de pertenencia al pueblo mapuche o de nacionalidad chilena, que estuvieran fuera del rango etario de interés, o que tuvieran algún trastorno del desarrollo, como discapacidad cognitiva o motora. La distribución de los grupos según edad y sexo se presenta en la Tabla 1.

Tabla 1: Distribución de los grupos de participantes según edad y sexo

Instrumentos

Cuestionario sociodemográfico: se registraron datos como la fecha de nacimiento, sexo, grupo cultural, procedencia y nivel de escolaridad de madres y padres.

Los instrumentos para evaluar FE fueron probados previamente y se seleccionaron porque han sido utilizados en estudios con población infantil y no implican una relación fuerte con habilidades de orden inferior, por lo que son más apropiados para evaluar el funcionamiento ejecutivo en participantes de contextos no occidentales, indígenas y rurales (Rosselli & Ardila, 2003; Rossen et al., 2005).

“Perros”: corresponde a una prueba de la Batería Psicopedagógica Evalúa 4 (García, 2016) de origen español, validada en Chile, que evalúa la capacidad de mantener una atención concentrada (observación analítica) y la de actualizar la información a corto plazo en tareas de reconocimiento (García et al., 2004). Consiste en reconocer ítems idénticos a un modelo dentro de un lapso de tres minutos. La prueba constó de 36 ítems, cada uno de los cuales se puntúo como 0: incorrecto (no es idéntico al modelo) y 1: correcto (es idéntico al modelo). El puntaje máximo es de 36 puntos.

Construcción con cubos: subprueba de la Escala de Inteligencia para Niños de Weschler (WISC-III), estandarizada en Chile por Rosas y Ramírez (2009). Esta prueba se encarga de evaluar la capacidad de analizar componentes, la organización perceptual y la reproducción de modelos. Por esto, podría utilizarse para evaluar el cambio entre conjuntos de tareas. Consiste en recrear diseños de colores rojo y blanco según un modelo, utilizando un número específico de cubos. Fueron 12 diseños a realizar, cada uno con un límite de tiempo prefijado para su puntuación. La corrección consideró si los ítems eran una reproducción exacta de los modelos, realizados en el tiempo reglamentario (no se bonificó puntaje por rapidez de ejecución). Se asignó 0 puntos a los diseños realizados fuera del tiempo límite o que no eran correctos y 1 punto a los diseños correctos realizados en el lapso normativo. El puntaje total máximo fue 12 puntos.

Test de los Cinco Dígitos (Sedó, 2007): consiste en la presentación de una lámina con 10 estímulos (números) y la subprueba respectiva con 50 estímulos, distribuidos en 10 filas. Los participantes deben leer los dígitos y en una segunda parte contar los números; es decir, realizar una transcodificación numérica automática que implica mencionar la cantidad de estímulos numéricos al interior del recuadro, inhibiendo su valor (Sedó & DeCristoforo, 2001). El puntaje obtenido en inhibición corresponde a la resta de los tiempos de ejecución en elección menos los tiempos de lectura (inhibición = elección-lectura). Los tiempos más rápidos indicaron un mejor rendimiento dentro de la prueba. Respecto a las evidencias de validez del instrumento, al compararse con el Test de Stroop, ha evidenciado una correlación entre -.57 y -.74 (p < .01) (Sedó & DeCristoforo, 2001).

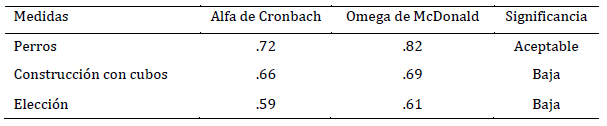

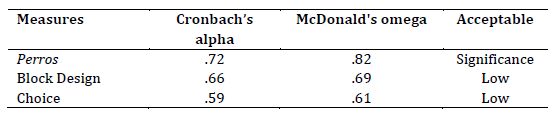

Los instrumentos no cuentan con una confiabilidad previamente definida en grupos de niños mapuche rurales y mapuche urbanos; por lo tanto, se aplicó análisis de consistencia interna con alfa de Cronbach. También se aplicó análisis con omega de McDonald, pues midió la confiabilidad sin depender del número de ítems (Ventura-León & Caycho-Rodríguez, 2017). Si bien la confiabilidad de todos los ítems no fue aceptable, dado el tamaño muestral y que el estudio es incipiente en el contexto nacional la consistencia interna obtenida se puede considerar confiable de acuerdo a la línea exploratoria de este estudio (Tabla 2).

Tabla 2: Estadísticos de confiabilidad por consistencia interna de instrumentos utilizados

Procedimiento

En conjunto con los profesores de los niños participantes del estudio se fijaron los días y horarios para aplicar los instrumentos. Se recabaron datos sociodemográficos de las fichas de información que las escuelas tenían de cada estudiante.

La administración de la batería de instrumentos fue realizada por dos asistentes, quienes aplicaron de manera individual los instrumentos a cada uno de los niños en una sala de la escuela. Antes de la aplicación de los instrumentos se dejó en claro que las evaluaciones no eran calificadas. Se motivó a contestar las mediciones lo más rápido posible.

En la tarea Perros, se explicó al niño que primero debía observar el modelo para luego marcar todos los dibujos que eran exactamente iguales al modelo y que podía borrar si se equivocaba. Para la Construcción con Cubos, la asistente mostró los cubos al niño, dispuso el cuadernillo de estímulos al lado derecho de la mesa y modeló el primer diseño. Mencionó que el trabajo consistía en juntar los cubos para reproducir los modelos. Para la ejecución de cada niño se registró con cronómetro los tiempos de finalización en cada uno de los 12 modelos y se registró si había falla por no ajustarse al modelo o por exceder el límite de tiempo. En cuanto al Test de los Cinco Dígitos, en la primera parte de la prueba (lectura), la asistente mostró al niño un ensayo, señalando que debía leer el número que aparecía en cada recuadro. Luego, aplicó la prueba en la que el niño debía leer en voz alta los números de cada uno de los recuadros. En la segunda parte (elección), se procedió a aplicar el ensayo y la prueba, y se solicitaba que contara cuántos números había en cada recuadro. En ambas partes, la asistente contabilizó errores y cronometró el tiempo total por niño, es decir, el tiempo para la prueba de lectura y para la prueba de elección.

Una vez finalizada la aplicación del conjunto de tareas los niños recibieron un lápiz y una goma de borrar como agradecimiento.

Resguardos éticos

El estudio contó con la aprobación del Comité Ético Científico de la Universidad de La Frontera. El protocolo ético implicó obtener el consentimiento informado tanto de los directivos de las escuelas como de los padres o madres de cada familia. También, se obtuvo el asentimiento informado de los niños participantes, previamente autorizados por sus tutores.

Análisis de datos

Los ítems de los instrumentos presentaron baja varianza, por lo que se seleccionaron solo aquellos con valores correctos e incorrectos entre 20 % y 80 %. Se crearon puntajes mediante el cálculo del promedio de los ítems seleccionados. Como los puntajes se elaboraron por la selección de ítems que tuvieron varianza aceptable, se optó por llamar al puntaje de Perros como actualización (17 ítems) y al puntaje de Construcción con Cubos como cambio entre conjuntos mentales (5 ítems).

Se procedió de manera diferente con el puntaje de inhibición del Test de los Cinco Dígitos, pues se calculó por la sustracción del tiempo en elección menos el tiempo de lectura. Esto implicó que a mayor puntaje hubo menor inhibición (Sedó, 2007). Lectura no tuvo varianza aceptable y elección quedó con 16 ítems. Con las puntuaciones obtenidas se realizó un análisis descriptivo.

Como las variables eran interpretables conjuntamente se aplicó un análisis MANOVA unifactorial intersujetos (tres grupos culturales). Los supuestos asociados a la prueba fueron: Kolmogorov-Smirnov indicó que las medidas no tuvieron normalidad univariada, aunque esto no se ratificó al observar los índices de asimetría y curtosis, pues en todos los puntajes (actualización, cambio entre conjuntos mentales e inhibición) estos indicadores eran < 1.96; por lo tanto, la distribución normal se cumplió. Con los resultados de la prueba Levene se asumió la independencia de la varianza de errores para las tres variables dependientes, pues obtuvieron un p > .05. Por último, las matrices de covarianza en los variables dependientes eran iguales en todos los grupos M de Box F(12)= 7.48, p = .85, con un valor p > .05.

Posteriormente con un ANOVA unifactorial intersujetos se examinaron las diferencias entre las variables dependientes. Para analizar entre qué grupos hubo diferencias se utilizó la prueba a posteriori Games-Howell, estadístico más robusto para el análisis. Adicionalmente, se utilizó ANOVA unifactorial intersujetos para evaluar diferencias respecto a los errores que cometieron los tres grupos en inhibición.

Los análisis de diferencias por sexo se realizaron con prueba t para grupos independientes que comparó actualización, cambio entre conjuntos mentales e inhibición por el factor fijo sexo. Se realizó análisis ANOVA unifactorial intersujetos (edad como factor fijo) para evaluar diferencias por edad.

Resultados

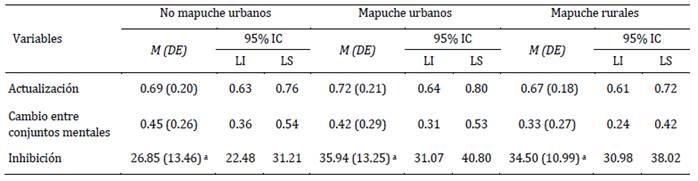

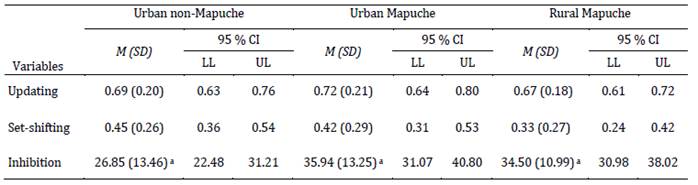

En primer lugar, se hace una presentación del análisis descriptivo de las variables dependientes en los tres grupos de participantes y posteriormente se presentan los resultados de los objetivos de investigación. La Tabla 3 presenta las medias, desviaciones estándar e intervalos de confianza de los puntajes actualización (Perros), cambio entre conjuntos mentales (Construcción con Cubos) e inhibición (Elección - Test de los Cinco Dígitos).

Tabla 3: Estadísticos descriptivos de las medidas de función ejecutiva

Nota: Las letras en superíndice indican diferencias estadísticamente significativas entre las celdas con la misma letra.

En la variable actualización fueron los niños mapuche urbanos quienes tuvieron una media mayor, es decir, estos niños tuvieron más actualización en comparación con los otros dos grupos. Respecto del cambio entre conjuntos mentales, fueron los niños no mapuche quienes tuvieron un mejor desempeño en comparación con los niños mapuche urbanos y los niños mapuche rurales. En inhibición ocurrió una situación similar a la anterior, puesto que los niños no mapuche tuvieron menor puntaje, por lo tanto mayor inhibición, puesto que tardaron menos tiempo en la prueba.

Primeramente, se analizaron las diferencias entre las variables de estudio en función del sexo y la edad. No se observaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en ninguno de los tres grupos culturales. La comparación entre niños y niñas en actualización, cambio entre conjuntos mentales e inhibición [t(108) = 0.626, p = .53; t(108) = 0.608, p = .54; t(108) = -0.387, p = .69, respectivamente], muestra que el desempeño según sexo es similar. Tampoco se observaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas en función de la edad en los tres grupos culturales en actualización, cambio entre conjuntos mentales e inhibición [F(2, 107) = 0.318, p = .72; F(2, 107) = 1.712, p = .18; F(2, 107) = 0.64, p = .52, respectivamente].

Para dar respuesta al objetivo general de investigación se realizó un análisis MANOVA según la significancia asociada a lambda de Wilks = 0.87 que indicó la existencia de diferencias estadísticamente significativas entre los tres grupos de niños [F(6, 210), p = .028 con h²p .07]. Específicamente, hubo un efecto principal significativo solo en la variable de inhibición [F(2, 107) = 5.591, p = .005, h²p .09]. Mientras que en las variables de actualización y de cambio entre conjuntos mentales no hubo diferencias con significancia estadística entre los grupos [F(2, 107) = 0.669, p = .514; y F(2, 107) = 2.019, p = .138, respectivamente].

Las diferencias entre los tres grupos en inhibición se obtuvieron a través de la prueba Games- Howell. Los niños no mapuche urbanos fueron más rápidos (M = 58.21 segundos, DE = 8.22 segundos) en comparación con los niños mapuche rurales (M = 62.38 segundos, DE = 12.54 segundos); en consecuencia, tuvieron una puntuación significativamente mayor en inhibición p = .019, IC 95% [-16.79, -1.39]. La comparación entre los niños no mapuche con los niños mapuche urbanos (M = 66.61 segundos, DE = 15.90 segundos) demostró que los no mapuche presentaron mayor inhibición (p = .017, IC 95 % [1.39, 16.79]). En el caso del grupo mapuche urbano y el grupo mapuche rural no se observaron diferencias estadísticamente significativas (p = .88, IC 95% [-8.52, 5.65]).

También se analizó la cantidad de errores cometidos en inhibición (no mapuche M = 2.97, DE = 2.94; mapuche urbanos M = 4.10, DE = 4.49; mapuche rurales M = 4.68, DE = 4.64). Se obtuvo que las diferencias entre los tres grupos culturales no fueron estadísticamente significativas (F(2, 107) = 1.764, p = .176).

Discusión

Este estudio tuvo como objetivo examinar la existencia de diferencias entre tres grupos culturales en actualización, cambio entre conjuntos mentales e inhibición. En inhibición se observaron diferencias estadísticamente con un tamaño del efecto cercano a grande (Fritz et al., 2012). Si bien, fueron los niños no mapuche quienes presentaron mayor inhibición, es fundamental interpretar este hallazgo a la luz de la naturaleza de esta medición, la que al ser cronometrada individualmente midió la velocidad de ejecución al contar la cantidad de estímulos numéricos en los recuadros, en lugar de decir el valor de los números presentes (Sedó, 2007). Además, es importante notar que la cantidad de errores fue similar en los tres grupos culturales y no hubo diferencias significativas. A su vez, los resultados mostraron que en las variables de actualización y cambio entre conjuntos mentales las diferencias entre los grupos no fueron estadísticamente significativas.

Posiblemente, los niños mapuche rurales demoraron más en la prueba de elección (Test de los Cinco Dígitos) y, por tanto, obtuvieron menores puntajes en inhibición, porque no están tan habituados al formato de evaluaciones que requieren tiempos cronometrados y acotados de ejecución. Tal vez estos niños disponen del tiempo de una manera diferente que al grupo no mapuche porque pueden explorar e interactuar en su entorno natural sin que los adultos aceleren el ritmo del aprendizaje (Becerra et al., 2018; Gaskins & Alcalá, 2023; Murray et al., 2015). A esto se suma que, el nivel de escolaridad de los padres y madres de estos niños, tanto mapuche urbano como mapuche rural, es más bajo en comparación con los no mapuche, cuestión que podría fomentar prácticas culturales que no se relacionan con tareas escolares cronometradas en tiempo límite (Sternberg et al., 2001).

Aun cuando se les indicó que realizaran la prueba lo más rápido posible, los niños mapuche (rurales y urbanos) trabajaron con más detenimiento. Esta manera de abordar las tareas también se ha observado en niños de otros pueblos indígenas, quienes demoran mayor cantidad de tiempo en ejecutar acciones y completar pruebas en comparación con niños estadounidenses (Alcalá et al., 2018; Mejía-Arauz et al., 2018). Probablemente, realizar las actividades sin acelerar la ejecución de las acciones es una manera cultural de aprender y desarrollar habilidades que pueden tener los niños indígenas mapuche rurales (Murray & Tizzoni, 2022).

Los niños mapuche pueden presentar un desempeño más bajo respecto al tiempo, dependiendo de las habilidades específicas que las pruebas miden (Baker et al., 2012; Gioia et al., 2000). Es necesario entender que las diferencias en las pruebas de funcionamiento ejecutivo se relacionan con que los creadores de los instrumentos pertenecen a un grupo cultural con alta escolarización y diseñan mediciones para grupos escolarizados, por eso los niños de entornos con alto nivel de escolaridad obtienen puntajes más altos (Ardila et al., 2005). Por lo tanto, los puntajes de los niños no mapuche, cuyas familias tienen alta escolaridad, no necesariamente revela que tengan más habilidades que los otros grupos. Más bien, podría demostrar que las habilidades ejecutivas del grupo no mapuche se ven reforzadas por la familiaridad con actividades escolares, que priorizan las habilidades cognitivas de orden inferior asociadas al conocimiento académico (Urzúa et al., 2009).

Cabe recordar que, investigaciones sobre el desarrollo de habilidades ejecutivas han basado sus análisis en estudios realizados con niños euroamericanos, primer contexto eco-social, lo que ha tenido como consecuencia que su nivel de rendimiento constituye el parámetro normativo con el que se evalúa a todos los niños independiente de su origen cultural (Morelli et al., 2003). Este estudio es contrario a esta idea, puesto que comprende que en el desarrollo infantil las habilidades ejecutivas son diversas por las prácticas y exigencias propias de los contextos socioculturales en los que crecen los niños (Gaskins & Alcalá, 2023).

Ahora bien, la variable sexo no fue un predictor de diferencias significativas en actualización, cambio entre conjuntos mentales e inhibición lo que concuerda con los hallazgos de Villaseñor et al. (2009). Por otra parte, no se observaron diferencias por edad, resultado que difiere de la idea de que un aumento en el desarrollo del funcionamiento ejecutivo depende trascendentalmente de la edad (Ardila et al., 2005; Lehto et al., 2003). Esto puede haber ocurrido porque el tramo etario era acotado y quizás no fue representativo de una curva de desarrollo gradual ni de los cambios acentuados del funcionamiento ejecutivo (Bausela, 2014).

Se considera que los resultados pueden ser un aporte teórico sobre el desarrollo de las habilidades de actualización, cambio entre conjuntos mentales e inhibición en los niños de contextos diversos, pues visibilizan diferencias entre los tres contextos eco-sociales según sus posibles prácticas. Además, se alienta a desarrollar estudios según la variabilidad intercultural y conforme a una evaluación culturalmente sensible de las habilidades ejecutivas (Carpendale & Lewis, 2006; Rosselli & Ardila 2003). Esto, debido a que las mediciones son dispositivos culturales que operan de manera distinta en cada contexto eco-social, por lo tanto, las diferencias en habilidades ejecutivas que reportan estas mediciones ocurren por las prácticas culturales particulares de los contextos, las que impactan en el desarrollo de las capacidades de los niños (Cole & Packer, 2019). En consecuencia, que un instrumento demuestre que un grupo tiene mejor o peor puntaje no es evidencia de una “falta de habilidades”, sino revela las diferencias culturales del desarrollo de habilidades ejecutivas (Farkas et al., 2017; Gaskins & Alcalá, 2023; Rosselli & Ardila, 2003). Ningún grupo cultural es desfavorecido, sino que simplemente desarrollan de manera diferente sus habilidades conforme a las oportunidades y necesidades de sus contextos (Kärtner et al. 2008; LeCuyer & Zhang, 2015).

Conclusiones

Este estudio obtiene resultados exploratorios, aunque también entrega evidencia empírica para el entendimiento de las habilidades ejecutivas de los niños no mapuche, mapuche urbanos y mapuche rurales. Los hallazgos revelan la importancia de considerar otras formas en que se desarrollan las habilidades de los niños, según los contextos de desarrollo (Keller & Kärtner, 2013). Los resultados obtenidos demuestran la necesidad de contar con instrumentos que evalúen el funcionamiento ejecutivo según las prácticas culturales. De tal modo, es importante entender el contexto cultural en el que el niño aprende para una evaluación exhaustiva en sí misma de los aspectos ejecutivos y culturales (Gioia et al., 2000).

Se sugiere que investigaciones futuras realicen más estudios que consideren las prácticas culturales y las habilidades ejecutivas de los niños en Chile para tener una compresión más acabada del efecto de dichas prácticas en el desarrollo de las habilidades de actualización, cambio entre conjuntos mentales e inhibición. Asimismo, es necesario que estudios futuros consideren que los tiempos de ejecución son diferentes entre los niños de contextos culturalmente diversos (Gaskins & Alcalá, 2023).

Referencias:

Alarcón, A., Astudillo, P., Castro, M., & Perez, S. (2021). Estrategias y prácticas culturales que favorecen el desarrollo de niñas y niños mapuche hasta los 4 años, La Araucanía, Chile. Revista Chilena de Antropología, (43), 80-95. https://doi.org/10.5354/0719-1472.2021.64433

Alcalá, L., Montejano, M. D. C., & Fernández, Y. S. (2021). How Yucatec Maya children learn to help at home. Human Development, 65(4), 191-203. https://doi.org/10.1159/000518457

Alcalá, L., Rogoff, B., & López Fraire, A. (2018). Sophisticated collaboration is common among Mexican-heritage US children. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 115(45), 11377-11384. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1805707115

Alonqueo, P., Alarcón, A. M., Hidalgo, C., & Herrera, V. (2022). Learning with respect: a Mapuche cultural value. Journal for the Study of Education and Development, 45(3), 599-618. https://doi.org/10.1080/02103702.2022.2059946

Anderson, V. A., Anderson, P., Northam, E., Jacobs, R., & Catroppa, C. (2001). Development of executive functions through late childhood and adolescence in an Australian sample. Developmental Neuropsychology, 20(1), 385-406. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15326942DN2001_5

Ardila, A., Rosselli, M., Matute, E., & Guajardo, S. (2005). The influence of the parents' educational level on the development of executive functions. Developmental Neuropsychology, 28(1), 539-560. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326942dn2801_5

Baker, D. P., Salinas, D., & Eslinger, P. J. (2012). An envisioned bridge: schooling as a neurocognitive developmental institution. Developmental Cognitive Neuroscience, 2, 6-17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dcn.2011.12.001

Bausela, E. (2014). Funciones ejecutivas: unidad-diversidad y trayectorias del desarrollo. Acción Psicológica, 11(1), 35-44. http://dx.doi.org/10.5944/ap.1.1.13790

Becerra, S., Merino, M. E., Webb, A., & Larrañaga, D. (2018). Recreated practices by Mapuche women that strengthen place identity in new urban spaces of residence in Santiago, Chile. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 41(7), 1255-1273. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2017.1287416

Blair, C., & Razza, R. P. (2007). Relating effortful control, executive function, and false belief understanding to emerging math and literacy ability in kindergarten. Child Development, 78(2), 647-663. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2007.01019.x

Bronfenbrenner, U. (1986). Ecology of the family as a context for human development: Research perspectives. Developmental Psychology, 22(6), 723. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.22.6.723

Cárcamo, R. A., Vermeer, H. J., van der Veer, R., & van IJzendoorn, M. H. (2015). Childcare in Mapuche and non-Mapuche families in Chile: The importance of socio-economic inequality. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 24(9), 2668-2679. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-014-0069-3

Carpendale, J., & Lewis, C. (2006). How children develop social understanding. Blackwell Publishing.

Cole, M., & Packer, M. (2019). Culture and cognition. Cross‐cultural Psychology, 243-270. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119519348.ch11

Defensoría de la Niñez. (2021). Informe anual. https://www.defensorianinez.cl/informe-anual-2021/wp-content/uploads/2021/11/panorama_estadistico_general.pdf

Diamond, A. (2002). Normal development of prefrontal cortex from birth to young adulthood: Cognitive functions, anatomy, and biochemistry. En D. T. Stuss & R. T. Knight (Eds.), Principles of frontal lobe function (pp. 466-503). Oxford University Press.

Diamond, A. (2013). Executive functions. Annual review of psychology, 64, 135-168. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143750

Egert, M., & Godoy, M. (2008). Semillas, cultivos y recolección al interior de una familia mapuche huilliche en Lumaco, Lanco, Región de los Ríos, Chile. Revista austral de Ciencias Sociales, 14, 51-70. https://doi.org/10.4206/rev.austral.cienc.soc.2008.n14-03

Farkas, C., Olhaberry, M., Santelices, M. P., & Cordella, P. (2017). Interculturality and early attachment: a comparison of urban/non-Mapuche and rural/Mapuche mother-baby dyads in Chile. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 26(1), 205-216. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10826-016-0530-6

Fritz, C. O., Morris, P. E., & Richler, J. J. (2012). Effect size estimates: current use, calculations, and interpretation. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 141, 2-18. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0024338

García, J. (2016). EVALÚA 4. Batería Psicopedagógica. Versión Chilena 2.0. EOS Gabinete de Orientación PS.

García, J., González, D. & García, B. (2004). Batería Psicopedagógica Evalúa-4. Manual Versión 2.0 (Edición adaptada para Chile). EOS.

García-Molina, A., Enseñat-Cantallops, A., Tirapu-Ustárroz, J., & Roig-Rovira, T. (2009). Maduración de la corteza prefrontal y desarrollo de las funciones ejecutivas durante los primeros cinco años de vida. Revista de Neurología, 48(8), 435-440.

Gaskins, S., & Alcalá, L. (2023). Studying executive function in culturally meaningful ways. Journal of Cognition and Development, 24(2), 260-279. https://doi.org/10.1080/15248372.2022.2160722

Gaskins, S., & Paradise, R. (2010). Learning through observation in daily life. En D. F. Lancy, J. Bock & S. Gaskins (Eds.), The anthropology of learning in childhood (pp. 85-118). AltaMira Press.

Gauvain, M., & Perez, S. (2015). Cognitive development and culture. En L. S. Liben, U. Müller, & R. M. Lerner (Eds.), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: Cognitive processes (7a ed., pp. 854–896). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118963418.childpsy220

Georgas, J., Waiss, L., Van de Vijver, F., & Saklofske, D. (2003). Culture and Children’s Intelligence: Cross-cultural analysis of the WISC-III. Academic Press.

Ghiardo Soto, F., & Dávila León, O. (2016). Procesos biográficos de la modernización en Chile. Polis, 15(44), 329-356. http://doi.org/10.4067/S0718-65682016000200015

Gioia, G. A., Isquith, P. K., Guy, S. C., & Kenworthy, L. (2000). Test review behavior rating inventory of executive function. Child Neuropsychology, 6(3), 235-238. https://doi.org/10.1076/chin.6.3.235.3152

Greenfield, P. (2009). Linking social change and developmental change: shifting pathways of human development. Developmental Psychology, 45(2), 401-418. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014726

Greenfield, P. M. (1996). Culture as process: Empirical methods for cultural psychology. En J. W. Berry, Y. H. Poortinga, & J. Pandey (Eds.), Handbook of cross-cultural psychology (pp. 301-346). Allyn & Bacon.

Hein, S., Reich, J., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2015). Cultural manifestation of intelligence in formal and informal learning environments during childhood. En L. A. Jensen (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of human development and culture: An interdisciplinary perspective (pp. 214-229). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199948550.013.14

Howitt, D. & Cramer, D. (2011). Introduction to research methods in psychology. Pearson Education Limited.

Imilan, W. A., & Álvarez, V. (2017). El pan mapuche: un acercamiento a la migración mapuche en la ciudad de Santiago. Revista Austral de Ciencias Sociales, 14, 23-49. https://doi.org/10.4206/rev.austral.cienc.soc.2008.n14-02

Instituto Nacional de Estadísticas. (2019). Radiografía de género. Pueblos originarios en Chile 2017. https://historicoamu.ine.cl/genero/files/estadisticas/pdf/documentos/radiografia-de-genero-pueblos originarios-chile2017.pdf

Jacob, R., & Parkinson, J. (2015). The potential for school-based interventions that target executive function to improve academic achievement: a review. Review of Educational Research, 85(4), 512-552. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654314561338

Kärtner, J., Keller, H., Lamm, B., Abels, M., Yovsi, R. D., Chaudhary, N., & Su, Y. (2008). Similarities and differences in contingency experiences of 3-month-olds across sociocultural contexts. Infant Behavior and Development, 31(3), 488-500. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infbeh.2008.01.001

Keller, H. (2015). Dual and communal parenting: Implications in young adulthood. En L. A. Jensen (Ed.), The Oxford handbook of human development and culture: An interdisciplinary perspective (pp. 586-601). Oxford University Press.

Keller, H. (2019). Culture and development. En D. Cohen & S. Kitayama (Eds.), Handbook of cultural psychology (pp. 397-423). The Guilford Press.

Keller, H., & Kärtner, J. (2013). Development: The cultural solution of universal developmental tasks. En M. J. Gelfand, C. Chiu, & Y. Hong (Eds.), Advances in culture and psychology (pp. 63-116). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199930449.003.0002

LeCuyer, E. A., & Zhang, Y. (2015). An integrative review of ethnic and cultural variation in socialization and children's self‐regulation. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 71(4), 735-750. https://doi.org/10.1111/jan.12526

Lehto, J. E., Juujärvi, P., Kooistra, L., & Pulkkinen, L. (2003). Dimensions of executive functioning: Evidence from children. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 21(1), 59-80. https://doi.org/10.1348/026151003321164627

Leontiev, A. N. (1978). Activity, consciousness, and personality. Prentice Hall.

Lewis, C., & Carpendale, J. I. M. (2009). Introduction: Links between social interaction and executive function. New Directions in Child and Adolescent Development, 123, pp. 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1002/cd.232

Lezak, M. D. (1982). The problem of assessing executive functions. International journal of Psychology, 17(1-4), 281-297. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207598208247445

Mejía-Arauz, R., Rogoff, B., Dayton, A., & Henne-Ochoa, R. (2018). Collaboration or negotiation: two ways of interacting suggest how shared thinking develops. Current Opinion in Psychology, 23, 117-123. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2018.02.017

Miller-Cotto, D., Smith, L, Wang, A., & Ribner, A. (2022). Changing the conversation: A culturally responsive perspective on executive functions, minoritized children and their families. Infant and Child Development, 31(1), e2286. https://doi.org/10.1002/icd.2286

Ministerio de Desarrollo Social, Gobierno de Chile. (2012). Encuesta Nacional sobre actividades de niños, niñas y adolescentes (EANNA). http://observatorio.ministeriodesarrollosocial.gob.cl/layout/doc/eanna/presentacion_EANNA_28junio_final.pdf

Ministerio de Desarrollo Social, Gobierno de Chile. (2017). 3ª Encuesta Longitudinal de Primera Infancia. Centro de Encuestas y Estudios Longitudinales (ELPI). Facultad de Ciencias Sociales, Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile. http://www.creciendoconderechos.gob.cl/docs/ELPI-PRES_Resultados_2017.pdf

Miyake, A., Friedman, N. P., Emerson, M. J., Witzki, A. H., Howerter, A., & Wager, T. D. (2000). The unity and diversity of executive functions and their contributions to complex “frontal lobe” tasks: A latent variable analysis. Cognitive Psychology, 41(1), 49-100. https://doi.org/10.1006/cogp.1999.0734

Morelli, G., Rogoff, B., & Angelillo, C. (2003). Cultural variation in young children’s access to work or involvement in specialized child-focused activities. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 27 (3), 264-274. https://doi.org/10.1080/01650250244000335

Murray, M., & Tizzoni, C. (2022). Personal autonomy, volition and participation during early socialization: a dialogue between the LOPI model and ethnographic findings in a Mapuche context. Journal for the Study of Education and Development, 45(3), 619-635. https://doi.org/10.1080/02103702.2022.2062917

Murray, M., Bowen, S., Segura, N., & Verdugo, M. (2015). Apprehending volition in early socialization: raising “little persons” among rural Mapuche families. Ethos, 43(4), 376-401. https://doi.org/10.1111/etho.12094

Obradovic, J., & Willoughby, M. (2019). Studying executive function skills in young children in low-and-middle- income countries: Progress and directions. Child Development, 13(4), 227-234. https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12349

Quilaqueo, D., Torres, H. & Alvarez-Santullano, P. (2022). Educación familiar mapuche: epistemes para el diálogo con la educación escolar. Pensamiento Educativo, 59(1), 1-12. http://doi.org/10.7764/pel.59.1.2022.1

Rodríguez, M., Rosas, R. & Pizarro, M. (2019). Rendimiento en escala WISC-V en población urbana y rural de Chile. CEDETi UC Papeles de Investigación, 11.

Rogoff, B. (2014). Learning by observing and pitching in to family and community endeavors: An orientation. Human Development, 57(2-3), 69-81. https://doi.org/10.1159/000356757

Rogoff, B., & Mejía-Arauz, R. (2022). The key role of community in learning by observing and pitching in to family and community ventures. Journal for the Study of Education and Development, 45(3), 494-548. https://doi.org/10.1080/02103702.2022.2086770

Rogoff, B., Dahl, A. & Callanan, M. (2018). The importance of understanding children’s lived experience. Developmental Review, 50, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.dr.2018.05.006

Rogoff, B., Paradise, R., Mejía-Arauz, R., Correa-Chávez, M., & Angelillo, C. (2003). Firsthand learning through intent participation. Annual Review of Psychology, 54(1), 175-203. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145118

Rosas, R., & Ramírez, V. (2009). WISC III: Test de inteligencia para niños de Wechsler [Versión estandarizada en Chile]. Ediciones Pontificia Universidad Católica de Chile.

Rosselli, M., & Ardila, A. (2003). The impact of culture and education on non-verbal neuropsychological measurements: A critical review. Brain and Cognition, 52(3), 326-333. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0278-2626(03)00170-2

Rossen, E. A., Shearer, D. K., Penfield, R. D., & Kranzler, J. H. (2005). Validity of the comprehensive test of nonverbal intelligence (CTONI). Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 23(2), 161-172. https://doi.org/10.1177/073428290502300205

Sedó, M. (2007). Five Digit Test (Test de los Cinco Dígitos). TEA Ediciones.

Sedó, M., & DeCristoforo, L. (2001). All-language test free from linguistic barriers, Revista Española de Neuropsicología, 3(3), 68-82.

Spiegel, J. A., Goodrich, J. M., Morris, B. M., Osborne, C. M., & Lonigan, C. J. (2021). Relations between executive functions and academic outcomes in elementary school children: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 147(4), 329-351. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000322

Sternberg, R. J., Nokes, C., Geissler, P. W., Prince, R., Okatcha, F., Bundy, D. A., & Grigorenko, E. L. (2001). The relationship between academic and practical intelligence: A case study in Kenya. Intelligence, 29(5), 401-418. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-2896(01)00065-4

Stucke, N., Stoet, G. & Doebel, S. (2022). What are the kids doing? Exploring young children's activities at home and relations with externally cued executive function and child temperament. Developmental Science, 25(5), e13226. https://doi.org/10.1111/desc.13226

Szulc, A. P. (2021). Más allá de la agencia y las culturas infantiles: reflexiones teóricas a partir de una investigación antropológica con niños y niñas Mapuche en y a partir del sur. En L. Rabello de Castro (Ed.) Infâncias do sul global experiências, pesquisa e teoria desde a Argentina e o Brasil (pp.79-91). Editor da Universidade Federal da Bahia.

Urzúa, A., Cortés, E., Prieto, L., Vega, S., & Tapia, K. (2009). Autoreporte de la calidad de vida en niños y adolescentes escolarizados. Revista Chilena de Pediatría, 80(3), 238-244. http://doi.org/10.4067/S0370-41062009000300005

van der Linden, M., Meulemans, T., Seron, X., Coyette, F., Andres, P., & Prairial, C. (2000). L’évaluation des fonctions exécutives. En X. Seron & M. Van der Linden (Eds.), Traité de Neuropsychologie Clinique (pp. 50-67). Solal.

Ventura-León, J. & Caycho-Rodríguez, T. (2017). El coeficiente omega: un método alternativo para la estimación de la confiabilidad. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 15(1), 625-627.

Villaseñor, E. M., Martín, A. S., Díaz, E. G., Rosselli, M., & Ardila, A. (2009). Influencia del nivel educativo de los padres, el tipo de escuela y el sexo en el desarrollo de la atención y la memoria. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 41(2), 257-276.

Vygotsky, L. S. (1997). The history of the development of higher mental functions. En R. W. Rieber (Ed.), The collected works of L.S. Vygotsky (pp. 1-251). Plenum Press.

Whiting, J. W. (1994). A model for psychocultural research. En E. H. Chasdi (Ed.), Culture and human development: The selected papers of John Whiting (pp. 89-104). Cambridge University Press.

Worthman, C. M. (2010). The ecology of human development: Evolving models for cultural psychology. Journal of Cross-Cultural Psychology, 41(4), 546-562. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022022110362627

Cómo citar: Muñoz Sanhueza, R., & Alonqueo Boudon, P. (2024). Habilidades ejecutivas: actualización, cambio entre conjuntos mentales e inhibición en niños no mapuche urbanos, mapuche urbanos y mapuche rurales de La Araucanía, Chile. Ciencias Psicológicas, 18(2), e-3385. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v18i2.3385

Contribución de los autores (Taxonomía CRediT): 1. Conceptualización; 2. Curación de datos; 3. Análisis formal; 4. Adquisición de fondos; 5. Investigación; 6. Metodología; 7. Administración de proyecto; 8. Recursos; 9. Software; 10. Supervisión; 11. Validación; 12. Visualización; 13. Redacción: borrador original; 14. Redacción: revisión y edición.

R. M. S. ha contribuido en 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14; P. A. B. en 1, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14.

Editora científica responsable: Dra. Cecilia Cracco.

10.22235/cp.v18i2.3385

Original Articles

Executive functions: updating, set-shifting, and inhibition in non-Mapuche urban children, Mapuche urban children, and rural Mapuche children in La Araucanía, Chile

Habilidades ejecutivas: actualización, cambio entre conjuntos mentales e inhibición en niños no mapuche urbanos, mapuche urbanos y mapuche rurales de La Araucanía, Chile

Habilidades executivas: atualização, mudanças entre conjuntos mentais e inibição em crianças não mapuches urbanas, mapuches urbanas e mapuches rurais de La Araucanía, Chile

Rebeca Muñoz Sanhueza1, ORCID 0000-0002-4393-1820

Paula Alonqueo Boudon2, ORCID 0000-0002-4582-1262

1 Universidad Católica de La Santísima Concepción, Chile, [email protected]

2 Universidad de La Frontera, Chile

Abstract:

Children's cognitive abilities differ according to the cultural development settings in which they are raised. Assuming cultural variability, this study compared the executive functions in 110 children, aged 9 to 11 years, belonging to three groups: urban non-Mapuche, urban Mapuche, and rural Mapuche, from communes in the Araucanía region, Chile. A descriptive and correlational design was used to contrast children's performance on the variables of interest. The battery of instruments comprised three tests that assessed updating, set-shifting, and inhibition, respectively. The results indicate no statistically significant differences in updating and set-shifting, but there was a statistical significance for differences in inhibition, with non-Mapuche children having greater inhibition than the other two groups. The findings are discussed according to the hypothesis that skill development is related to the daily practices, demands, and sociodemographic characteristics of the settings in which children are raised.

Keywords: cultural contexts; cultural differences; executive functions; Mapuche children; culture; Chile.

Resumen:

Las habilidades cognitivas de los niños varían conforme a los contextos de desarrollo cultural en los que se desenvuelven. Asumiendo la variabilidad cultural, este estudio tuvo por objetivo comparar las habilidades ejecutivas en 110 niños, entre 9 y 11 años, pertenecientes a tres grupos: no mapuche urbanos, mapuche urbanos y mapuche rurales, de comunas de la región de La Araucanía, Chile. Se usó un diseño descriptivo y correlacional para contrastar el desempeño de los niños en las variables de interés. La batería de instrumentos estuvo formada por tres pruebas que evaluaron: actualización, cambio entre conjuntos mentales e inhibición, respectivamente. Los resultados indican que no hubo diferencias estadísticamente significativas en actualización y cambio entre conjuntos mentales, pero sí hubo significancia estadística para las diferencias en inhibición; siendo los niños no mapuche quienes tuvieron mayor inhibición respecto de los otros dos grupos. Se discuten los hallazgos según la hipótesis de que el desarrollo de habilidades se relaciona con las prácticas cotidianas, demandas y características sociodemográficas de los contextos en los que los niños se desarrollan.

Palabras clave: contextos culturales; diferencias culturales; habilidades ejecutivas; niños mapuche; cultura; Chile.

Resumo:

As habilidades cognitivas das crianças variam conforme os contextos de desenvolvimento cultural em que elas se desenvolvem. Partindo do pressuposto da variabilidade cultural, este estudo teve como objetivo comparar as habilidades executivas de 110 crianças, com idades entre 9 e 11 anos, pertencentes a três grupos: não mapuche urbanas, mapuche urbanas e mapuche rurais, de municípios da região de La Araucanía, Chile. Foi utilizado um desenho descritivo e correlacional para comparar o desempenho das crianças nas variáveis de interesse. A bateria de instrumentos foi composta por três testes que avaliaram: atualização, mudança entre conjuntos mentais e inibição, respectivamente. Os resultados indicam que não houve diferença estatisticamente significativa em atualização e mudança entre conjuntos mentais, mas houve significância estatística para as diferenças em inibição, com as crianças não mapuches apresentando maior inibição do que os outros dois grupos. Os resultados são discutidos de acordo com a hipótese de que o desenvolvimento de habilidades está relacionado às práticas cotidianas, demandas e características sociodemográficas dos contextos em que as crianças se desenvolvem.

Palavras-chave: contextos culturais; diferenças culturais; habilidades executivas; crianças mapuches; cultura; Chile.

Received: 28/12/2023

Accepted: 05/07/2024

Numerous studies have discovered that age, as a measure of maturity, is an explanatory factor for executive function: the older the person, the higher the scores in executive functions (Ardila et al., 2005; Bausela, 2014), although the increase in scores may depend on the type of measure used. For example, Anderson et al. (2001), in a study of 138 children aged 11 to 17 years, found that the developmental trajectory for executive functioning remained largely stable during late childhood and early adolescence. This study shows the need to assess the progression of executive functions at different ages through a broad battery of tasks with a latent variable approach rather than a single test that does not accurately demonstrate a complex cognitive processing level with more marked shifts in performance over the years (Anderson et al., 2001; Lehto et al., 2003; Obradovic & Willoughby, 2019).

The skill set that constitutes executive functioning varies among different authors, but there is consensus that there are three fundamental components: updating and overseeing representations of the working memory (hereafter updating), shifting between mental sets or tasks, and inhibition of dominant responses (inhibitory control including self-monitoring and interference control) (Lehto et al., 2003; Miyake et al., 2000). The operational definition of these executive functions is more accurate than others, and all three are likely involved in the performance of more complex conventional executive functions (Diamond, 2013; Miyake et al., 2000). For example, the Five-Digit Test is proposed as a test that measures set-shifting to switch between classification principles as well as inhibition to suppress inappropriate responses (Sedó, 2007).

Updating is the ability to retain information to fulfill a task and is a critical skill for reasoning (Lehto et al., 2003). It allows reordering and working with data mentally to update them while performing tasks related to those data (Carpendale & Lewis, 2006; Diamond, 2013). Set-shifting is the ability to change one way of solving a problem to another to respond appropriately to a situation (Lewis & Carpendale, 2009). It requires shifting the attentional focus from one class of stimuli to a different one and switching between two cognitive sets (van der Linden et al., 2000). This ability makes it possible to generate different ideas, consider alternative behaviors, and respond to new situations; therefore, it is relevant for regulating behavior, and if reduced, it can produce rigid and inflexible behavior (Diamond, 2002). Finally, inhibition is “ability to deliberately inhibit dominant, automatic, or prepotent responses when necessary” (Miyake et al., 2000, p. 57). It is constituted by inhibitory control and self-control: inhibitory control makes it possible to suppress salient reactions (Lewis & Carpendale, 2009), and self-control allows one to master one's own performance to make sure that the goal has been appropriately achieved (Lehto et al., 2003). In summary, inhibition facilitates effective self-regulation, motivation to execute behaviors, and the acquisition of emotional control (García-Molina et al., 2009).

Most research identifying disparities in children's executive functions has been conducted with middle-class Western populations and has employed tasks incorporating various lower-order skills (e.g., reading proficiency, expressive and receptive language, among others), such that a lack of experience in these skills may lead to low overall scores on executive functioning assessments, despite the absence of cognitive deficits (Anderson et al., 2001). This way of assessing skills neglects the importance of sociocultural factors that support divergent development of executive functioning (Gaskins & Alcalá, 2023). By not assessing all components of the executive domain, the instruments may lack ecological validity in culturally diverse groups (Gioia et al., 2000; Miller-Cotto et al., 2022).

In this light, it is imperative to know the characteristics of the child's developmental context to assess executive functions since cultural practices and socio-familial demands condition the development of cognitive skills (Carpendale & Lewis, 2006), and, in turn, enhance certain executive functions over others (Gaskins & Alcalá, 2023; Georgas et al., 2003). Psychological processes arise from engagement in culturally and historically mediated actions (Rogoff et al., 2018).

This cultural perspective makes it possible to overcome the normative and standard view of children's abilities (Hein et al., 2015; Rogoff & Mejía-Arauz, 2022). Differences in skills do not occur because of a lack of universal traits, but rather because of the adaptation of executive developmental predispositions to the specific practices of varying cultural contexts (Keller & Kärtner, 2013; Stucke et al., 2022). Therefore, it is incongruous to presume that children living in highly diverse cultural settings will exhibit identical developmental patterns (Worthman, 2010).

According to socioecological development models, the family environment and the characteristics of the home setting are ecologies that directly or indirectly impact children's learning, which favors the development of particular cognitive skills (Bronfenbrenner, 1986; Worthman, 2010). In line with these ideas, Keller (2015) proposed the model of ecocultural development - originally formalized by Whiting (1994) - which posits that skills develop according to eco-social conditions, cultural models, and socialization strategies (Keller & Kärtner, 2013).

Eco-social contexts refer to specific groups of families and communities distinguished according to their level of formal schooling, place of residence, type of family economy, and whether they are communities of post-industrial societies (Keller, 2015). The interrelation of these variables influences the implementation of learning practices and the cultivation of specific skills.

The education level of the children's caregivers produces differences among eco-social contexts. The abstract knowledge acquired at school could determine the parents' occupations and, thus, the family's socioeconomic level, which affects children's daily practices (Greenfield, 1996). In this sense, the socioeconomic characteristics of eco-social contexts promote specific practices that enable the emergence of cognitive processes that, in turn, are modulated by the demands of the same settings (Lewis & Carpendale, 2009; Rogoff et al., 2018).

Keller (2015) proposed three eco-social development contexts that in this study are assumed as the basis for distinguishing three different groups of children: urban non-Mapuche, urban Mapuche, and rural Mapuche.

The first context comprises Western middle-class, non-indigenous, urban families from post-industrialized countries whose caregivers have a high education level (12 or more years). They often have skilled labor occupations in a free market economy. These are nuclear families with few children whose interactions are based primarily on school issues (Keller, 2019; Morelli et al., 2003). These families assume that better school performance in childhood facilitates better jobs in adult life (Sternberg et al., 2001). As a result, children often occupy their time in “childhood-like” activities, engaging in institutionalized practices that promote the development of abstract skills, individual exploration, expressive communication, and reflective self-awareness (Keller & Kärtner, 2013). For these families, the ultimate goal of child development is equivalent to scholastic achievement (Rogoff et al., 2003).

Families in this eco-social context value their children’s school dynamics, which could greatly affect the executive performance of these children (Baker et al., 2012). Training these children in school routines could notably influence high scores on executive functioning tests, especially in visual memory (Ardila et al., 2005; Spiegel et al., 2021); thus, familiarity with school activities would facilitate greater executive performance (Blair & Razza, 2007; Carpendale & Lewis, 2006; Jacob & Parkinson, 2015).

In Chile, the results of the Survey of Activities of Children and Adolescents (EANNA) show that this eco-social context is formed by urban non-Mapuche families (Ministerio de Desarrollo Social, 2012). It tends to be a nuclear family, and parenting is carried out by a narrow network of people, which could restrict children's possibilities to participate in collaborative activities with others, according to the Third Longitudinal Survey of Early Childhood (ELPI) (Ministerio de Desarrollo Social, 2017). As a result of a change in parental beliefs that value early education and the achievement of secondary school certification, Chilean children have stopped helping with household chores (Ghiardo Soto & Dávila León, 2016). Family interactions revolve around school performance, which implies that they invest a lot of time in academic activities and practices conducive to independence and autonomy (Urzúa et al., 2009) while they spend little time (one hour per week) participating in the household (sweeping, cleaning, etc.) (Ministerio de Desarrollo Social, 2012).

A second eco-social development context comprises middle-class, non-Western urban families of indigenous heritage. This heritage is perceived as a patrimony of values, beliefs, and practices associated with the indigenous identity of origin, shared among individuals of multiple generations (Rogoff et al., 2003). In these families, parents possess advanced education and reside in urban areas due to migration from rural regions, driven by their need for employment opportunities and access to formal education (Cárcamo et al., 2015). The family bond persists while concurrently fostering a feeling of individual identity (Keller, 2019), attributable to schooling, the decline of an agricultural economy, and employment outside the house (Greenfield, 2009).

In Chile, urban Mapuche families share the characteristics of this second context. They have migrated from rural areas due to land usurpation by the State and private individuals. Obtaining specialized jobs and access to schools have been other causes of migration (Imilan & Álvarez, 2017). Some of these families stay in contact with their communities of origin in a relationship of socio-spiritual dependence between the country and the city (Imilan & Álvarez, 2017). They have some command of the Mapuche language and maintain their cultural identity, participating in practices that bring the extended family together (Becerra et al., 2018). However, their daily routine has adapted to the Chilean education system, which imposes a monocultural model of school knowledge acquisition (Quilaqueo et al., 2022). Children must fulfill school obligations, and since adult jobs are not performed at home, they have fewer opportunities to collaborate in the family. Children's daily activities are carried out according to the direction of parents who encourage speed and efficiency in their actions (Murray et al., 2015). By not having frequent contact with nature, children learn in simulated contexts, making it difficult to explore and manipulate elements in the natural environment (Egert & Godoy, 2008).

The last eco-social context is represented by extended families with indigenous heritage residing in rural areas, whose parents have a low education level (eight years or fewer) (Keller & Kärtner, 2013). This aligns with minimal interaction with urban centers and the preservation of traditional customs (Rogoff et al., 2018). The jobs performed by these families do not require academic training, as they are trades learned from generation to generation that include agricultural, livestock, and domestic activities. In this context, children interact with people of different ages and progressively cooperate in tasks such as planting and harvesting, caring for animals, making textiles to sell, and others (Morelli et al., 2003).