10.22235/cp.v18i1.3369

Análisis psicométrico de dos versiones del Big Five Inventory-15 en estudiantes universitarios chilenos: estructura interna, invarianza de edición y asociación con bienestar subjetivo

Psychometric analysis of two versions of the Big Five Inventory -15 in Chilean college students: internal structure, measurement invariance and association with subjective well-being

Análise psicométrica de duas versões do Big Five Inventory -15 em estudantes universitários chilenos: estrutura interna, invariância de medição e associação com bem-estar subjetivo

Sergio Dominguez-Lara1, ORCID 0000-0002-2083-4278

Marcos Carmona-Halty2, ORCID 0000-0003-4475-1175

Marion K. Schulmeyer3, ORCID 0000-0002-0707-0656

Sabina N. Valente4, ORCID 0000-0003-2314-3744

Abílio A. Lourenço5, ORCID 0000-0001-6920-0412

1 Universidad de San Martín de Porres, Perú, [email protected]

2 Universidad de Tarapacá, Chile

3 Universidad Privada de Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia

4 Instituto Politécnico de Portalegre; Universidade de Évora, Portugal

5 Universidade do Minho, Portugal

Resumen:

El objetivo de esta investigación fue analizar la estructura interna de dos versiones del Big Five Inventory-15 (BFI-15), invarianza de medición y su relación con el bienestar subjetivo en estudiantes universitarios chilenos. Participaron 1011 estudiantes (mujeres = 54.80 %; Medad = 21.55 años; DEedad = 2.11 años). Los resultados indican que la versión peruana del BFI-15 (BFI-15p) tiene indicadores más consistentes con relación a su estructura interna (e.g., cargas factoriales) en comparación a la versión alemana (BFI-15a), así como una estructura invariante entre hombres y mujeres, y una asociación significativa con las dimensiones del bienestar subjetivo. Finalmente, la confiabilidad del constructo y de las puntuaciones alcanzó magnitudes adecuadas. Se concluye que el BFI-15p presenta propiedades psicométricas adecuadas para su uso en universitarios chilenos.

Palabras clave: personalidad; bienestar subjetivo; validez; confiabilidad.

Abstract:

The purpose of this research was to analyze the internal structure of the Big Five Inventory-15 (BFI-15), measurement invariance and its association with subjective well-being, in Chilean college students. A sample of 1011 college students (female = 54.80%; Mage = 21.55 years; SDage = 2.11 years) was used. Results showed the Peruvian version of BFI-15 (BFI-15p) has more consistent indicators regarding their internal structure (e.g., factor loadings) compared to the German (BFI-15a) version, an invariant structure between men and women, and a significant association with subjective well-being was found. Finally, the construct reliability and scores reliability reached adequate magnitudes. It is concluded that the BFI-15p has adequate psychometric properties for use in Chilean college students.

Keywords: personality; subjective well-being; validity; reliability.

Resumo:

O objetivo desta investigação foi analisar a estrutura interna de duas versões do Big Five Inventory-15 (BFI-15), invariância de medição e a sua relação com o bem-estar subjetivo em estudantes universitários chilenos. Participaram 1011 estudantes universitários (mulheres = 54.80%; Midade = 21.55 anos; DPidade = 2.11 anos). Os resultados indicam que a versão peruana do BFI-15 (BFI-15p) tem indicadores mais consistentes em relação à sua estrutura interna (por exemplo, cargas fatoriais) em comparação com a versão alemã (BFI-15a), bem como uma estrutura invariante entre homens e mulheres, e uma associação significativa com as dimensões do bem-estar subjetivo. Por fim, a confiabilidade do construto e das pontuações atingiram magnitudes adequadas. Conclui-se que o BFI-15p apresenta propriedades psicométricas adequadas para uso em estudantes universitários chilenos.

Palavras-chave: personalidade; bem-estar subjetivo; validade; confiabilidade.

Recibido: 27/05/2023

Aceptado: 15/05/2024

El modelo de los cinco grandes factores

La personalidad normalmente se considera como el conjunto de características que hacen pensar, sentir y actuar de una manera única a una persona (McKnight et al., 2019) y, en un extremo, como un constructo superordinado que engloba diversos elementos tanto cognitivos como no cognitivos (Dangi et al., 2020). Por lo tanto, se refiere a la particularidad del individuo y aquello que lo distingue de todos los demás, así como a un conjunto de características psicológicas estables y duraderas en el tiempo y las situaciones que permiten establecer un estilo característico de interacción con el contexto físico y social (Mõttus et al. 2017). Según Barbachán-Ruales et al. (2018), los estudiantes universitarios poseen una multiplicidad de rasgos intrínsecos a su personalidad; sin embargo, esta se revela eficaz al manifestarse en circunstancias susceptibles de ser interpretadas a la luz del autoconocimiento. En esta línea, se buscan agentes motivacionales que los impulsen a estudiar y a enfrentar los desafíos delineados en el ámbito educativo, lo que le brinda la esperanza de alcanzar sus designios y propósitos.

La personalidad podría concebirse como un sistema determinado por rasgos y procesos dinámicos que intervienen en el proceso psicológico individual. Si bien existen algunos planteamientos que destacan estos elementos, el modelo de los cinco grandes factores (5GF; McCrae & Costa, 1999, 2004) es uno de los más importantes y es la taxonomía más reconocida para evaluar los rasgos de personalidad (Zhang et al., 2019). Durante las últimas décadas, el modelo de los 5GF ha sido reconocido como una representación primordial de los rasgos prominentes y no patológicos de la personalidad, cuya modificación contribuye a la aparición de trastornos de personalidad, como los trastornos antisociales, límite y narcisista (Angelini, 2023).

El modelo de los 5GF indica que los individuos se caracterizan por un patrón de pensamientos, sentimientos y acciones que pueden agruparse en torno a cinco dimensiones: neuroticismo, extroversión, apertura, amabilidad y responsabilidad (McCrae & Costa, 2004). Su validez, universalidad y estabilidad longitudinal han sido respaldadas por la investigación empírica (e.g., McAdams & Pals, 2006), ya que este modelo tiende a ser más fuerte en las culturas occidentales que en las no occidentales, así como con similar nivel educativo y de ingresos (Rammstedt et al., 2013), aunque también se conoce que no se replica en algunos contextos (e.g., Fetvadjiev & van der Vijver, 2015), ya que las modificaciones realizadas a diversas escalas alteran tanto el instrumento como las interpretaciones que se hacen de los ítems (e.g., Fetvadjiev & van der Vijver, 2015), lo que impulsa la creación de otros modelos teóricos de personalidad orientados a determinadas idiosincrasias (e.g., Gurven et al., 2013). Esto sugiere que las diferencias culturales y étnicas pueden influir en la forma en que se expresan y perciben los rasgos de la personalidad. Aunque el modelo 5GF ofrece un marco pertinente para comprender la personalidad humana, es importante reconocer la necesidad de enfoques complementarios en determinadas culturas y etnias.

La primera dimensión, el neuroticismo, se caracteriza por la tendencia a experimentar afecto negativo (tristeza, miedo, ira, culpa, etc.), y se asocia a la estabilidad emocional y a la gestión de las emociones, que se traduce en vulnerabilidad y ansiedad (Zhang et al., 2024). De este modo, puede predecir una menor capacidad para lidiar con eventos adversos (Angelini, 2023; Zuo et al., 2024). La segunda dimensión, extroversión, se asocia a un estado de sociabilidad caracterizado por el asertividad y la confianza, es decir, aquellas personas que aprecian la convivencia con los demás y el trabajo en equipo, que son emocionalmente positivas (Bertoquini & Ribeiro, 2006) y son capaces de impactar individualmente sobre la interacción del grupo de pertenencia (Barry & Friedman, 1998). La tercera dimensión denominada apertura se relaciona con la imaginación, curiosidad, originalidad, con intereses diversificados y no tradicionales, con una actividad intelectual proactiva, y la preferencia por tareas que involucran complejidad cognitiva (McCrae & Costa, 1997). La cuarta dimensión, la amabilidad, está caracterizada por la simpatía, flexibilidad, confianza, tolerancia y preocupación por los demás, con orientación prosocial y con preferencia por el desarrollo de actividades grupales (Costa & McCrae, 1992), lo que facilitaría el establecimiento de relaciones interpersonales positivas. La última dimensión, responsabilidad, se refiere a la organización, autodisciplina, persistencia, prudencia y capacidad de planificación (Kaftan & Freund, 2018) para lograr las metas personales, además de estar asociada a un mayor autocontrol y a un menor nivel de externalización agresiva (McCrae & Costa, 1999).

Conforme con lo expuesto, la evaluación de la personalidad es relevante en el ámbito universitario tanto para labores de investigación como para contextos aplicados, ya sea por su relevancia evolutiva en cuanto a sus diferencias según sexo o edad (e.g., Zhang et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2024), o por su asociación con variables relevantes como el rendimiento académico (responsabilidad; Vedel, 2014), la motivación académica (neuroticismo y responsabilidad; McGeown et al., 2014), la procrastinación (neuroticismo y apertura; Ocansey et al., 2020), la autorregulación motivacional (responsabilidad; Ljubin-Golub et al., 2019), deshonestidad académica (responsabilidad y amabilidad; Giluk & Postlethwaite, 2015), autoeficacia académica (responsabilidad y apertura; McIIloy et al., 2015), apoyo social (extraversión; Barańczuk, 2019), burnout académico (neuroticismo; Prada-Chapoñan et al., 2020; amabilidad y neuroticismo; Araújo, 2024), o el bienestar subjetivo (Nunes et al., 2009).

Personalidad y diferencias según sexo

Las diferencias evolutivas o socioculturales entre hombres y mujeres se evidencian en la manifestación de sus conductas en entornos específicos (Schmitt et al., 2017), por lo que es relevante contar con medidas válidas y confiables para exponer esas diferencias. Por ejemplo, estudios anteriores indican que las diferencias en función del sexo con respecto a los cinco grandes de la personalidad no son concluyentes, ya que si bien las estudiantes universitarias muestran puntuaciones más altas en los cinco grandes rasgos de la personalidad (Bunker et al., 2021; Sander & Fuente, 2020), otros estudios muestran que las mujeres registraron puntuaciones más altas en extraversión, amabilidad y neuroticismo que los hombres (Liu et al., 2024), y para otros autores los hombres puntúan más alto en apertura, extraversión y responsabilidad (Abdel-Khalek, 2021). Por otro lado, en otros estudios se encontró que las mujeres puntúan más alto en extraversión, responsabilidad y apertura, mientras que puntúan de forma similar en amabilidad y neuroticismo (Bunnett, 2020; Dominguez-Lara et al., 2019). Sin embargo, en ocasiones los grupos se comparan sin brindar evidencias de invarianza de medición (Pendergast et al., 2017), lo que podría llevar a cuestionar la legitimidad de las diferencias encontradas dado que se podrían adjudicar a aspectos ajenos al constructo (sesgo).

Personalidad y bienestar subjetivo

El bienestar subjetivo (BS) hace referencia a un conjunto de valoraciones emocionales y cognitivas hechas sobre las distintas áreas de la vida (Diener et al., 2009). Por un lado, la dimensión cognitiva se corresponde con la satisfacción con la vida (SV), aquel proceso de evaluación general de la propia vida (Emmons, 1986) que surge de la comparación entre las circunstancias actuales e ideales de la vida de la persona, aunque considerando elementos importantes como las metas, valores o la cultura (Calleja & Masón, 2020). Por otro lado, la dimensión emocional se constituye por el afecto positivo (AP) y afecto negativo (AN; Diener et al., 2002), los cuales representan los elementos emocionales (placer, felicidad, angustia, etc.). De esta forma, un BS elevado incluye diversas experiencias emocionales positivas, pocas experiencias emocionales negativas (e.g., depresión o ansiedad) y la SV entendida como un todo. Así, se entiende que diferentes trayectorias de vida, rasgos de personalidad, arquitectura cerebral, así como el entorno y la cultura en los que los individuos se encuentran, influencian la perspectiva individual y subjetiva del bienestar (Oguntayo et al., 2024; van Valkengoed et al., 2023).

En este orden de ideas, uno de los predictores más estudiados del BS es la personalidad (Lucas, 2018), específicamente desde el modelo de los 5GF, que proporciona dos explicaciones sobre la asociación entre dichos constructos. En primer lugar, se habla de un modelo temperamental que explica las relaciones directas entre los sistemas fisiológicos subyacentes y las experiencias afectivas que los individuos tienen. En segundo lugar, de un modelo instrumental que entiende el bienestar como un resultado indirecto de las condiciones que los individuos crean en función de sus rasgos de personalidad (Lucas, 2018; McCrae & Costa, 1991).

Entonces, el neuroticismo y la extroversión pueden estar relacionados al BS a través de los mecanismos inherentes a ambos modelos. Por ejemplo, desde el modelo temperamental, el nivel de BS experimentado por personas con elevados neuroticismo y extroversión puede ser parcialmente justificado por sus niveles afectivos básicos y por la intensidad de las respuestas emocionales que los caracterizan (McCrae & Costa, 1991). En cuanto al modelo instrumental, la responsabilidad y apertura se considera como rasgos importantes, aunque no determinantes para el BS (McCrae & Costa, 1991). No obstante, la confianza de los extrovertidos para afrontar la vida, así como la percepción situacional de amenaza y preocupación por eventos potencialmente estresantes vividos por individuos con alto grado de neuroticismo, ayudan a cambiar la percepción del contexto y, en consecuencia, afectan el BS (Margolis & Lyubomirsky, 2018).

Sobre la relación entre personalidad y BS, la evidencia empírica indica que la extraversión se relaciona directamente con el AP y con la SV; la responsabilidad se asocia de forma directa con la SV y con el AP, y tanto la extraversión como la responsabilidad se relacionan inversamente con el AN. El neuroticismo se vincula con niveles elevados de AN, así como con niveles bajos de SV y de AP (Anglim et al., 2020; Carmona-Halty & Rojas-Paz, 2014; Jensen et al., 2020; Kobylińska et al., 2022).

El Big Five Inventory y sus versiones breves

De acuerdo con lo mencionado, es clara la importancia de la personalidad para la predicción del comportamiento del individuo, por lo que es relevante evaluarla con instrumentos que cuenten con evidencias de confiabilidad y validez. Entonces, si bien se usan una diversidad de escalas para tal fin, uno de los instrumentos de libre acceso más conocidos y utilizados es el Big Five Inventory (BFI; John et al., 1991), que posee una versión en español estándar libre de regionalismos, lo que facilita su comprensión en diferentes contextos hispanohablantes (Benet-Martínez & John, 1998), no es demasiado extensa (44 ítems), es de libre acceso (el usuario no debe comprar los derechos de uso) y cuenta con estudios psicométricos en el contexto latinoamericano (Dominguez-Lara et al., 2018; Salgado et al., 2016) y recientemente en universitarios chilenos (Lara et al., 2021).

El BFI evalúa los 5GF de forma dimensional y cuenta con diversas versiones breves que brindan una valoración más comprehensiva de las dimensiones del modelo. Esto resulta de utilidad sobre todo cuando se pretende evaluar más de un constructo en un mismo estudio en el marco de diseños explicativos y se desea maximizar la participación del respondiente, o cuando el tiempo o espacio disponible para evaluar el constructo es bastante corto. Por ejemplo, existen versiones de 10 ítems (Rammstedt & John, 2007) y 15 ítems (Gerlitz & Schupp, 2005; Marcos et al., 2023; Zhang et al., 2019) con dos y tres ítems por dimensión respectivamente, las cuales evidencian resultados aceptables en el contexto europeo occidental (Courtois et al., 2020; Guido et al., 2015; Rammstedt, 2007), aunque su calidad psicométrica disminuye cuando se analizan en contextos distintos (Dominguez-Lara & Merino-Soto, 2018a; Kim et al., 2010; Kunnel et al., 2019).

A partir de esa situación se generó una versión alternativa de 15 ítems (BFI-15p; Dominguez-Lara & Merino-Soto, 2018a) que presenta evidencia psicométrica favorable a nivel de estructura interna en Perú y México (Dominguez-Lara & Merino-Soto, 2018b; Dominguez-Lara et al., 2022). Resulta de interés analizar su adecuación en una muestra chilena considerando la importancia de la personalidad en el ámbito académico (Mammadov, 2022) porque, hasta donde se conoce, no existen instrumentos breves que midan este constructo, lo que también podría contribuir a realizar futuros estudios transnacionales en el ámbito de la personalidad. Además, el análisis de invarianza de medición de acuerdo con el sexo fue una recomendación de estudios previos que, por cuestiones metodológicas, no se pudo ejecutar (Dominguez-Lara & Merino-Soto, 2018b; Dominguez-Lara et al., 2022).

El presente estudio

Las evidencias de validez con relación a la estructura interna son importantes dado que permiten concluir si la configuración de los ítems es coherente con la teoría previa (Steyn & Ndofirepi, 2022), por lo que el estudio analizó si la estructura interna de las dos versiones del BFI-15 (peruana y alemana) es compatible con el modelo de los 5GF en universitarios chilenos, considerando la distribución de ítems y la magnitud de cargas factoriales.

En cuanto a la estructura interna del BFI-15, se espera que el modelo peruano tenga mayor respaldo en la muestra chilena que el modelo alemán, debido a la proximidad geográfica y aspectos culturales en común (Hipótesis 1).

La literatura indica que las dimensiones del modelo de los 5GF se encuentran vinculados teórica y empíricamente (Dominguez-Lara et al., 2018; Jensen et al., 2020; Lara et al., 2021), por lo que se esperan asociaciones positivas entre las dimensiones extraversión, amabilidad, responsabilidad y apertura, y asociación negativa entre estas dimensiones y el neuroticismo (Hipótesis 2). En cuanto a la confiabilidad, se espera que los coeficientes calculados (α y ω) alcancen magnitudes aceptables (> .70; Hipótesis 3), y que la medida con mayor respaldo estructural (BFI-15p o BFI-15a) presente evidencias de invarianza de medición entre hombres y mujeres (Hipótesis 4).

Finalmente, es necesario implementar otros procedimientos para brindar más evidencias de validez, sobre todo aquellos que involucren constructos afines teóricamente con el objetivo de enriquecer los hallazgos iniciales. En ese sentido, se espera que las dimensiones de la personalidad del BFI-15 se asocien significativamente con las dimensiones del BS: SV, AP y AN. Específicamente, la siguiente dirección de las correlaciones: AP y SV presentarán una asociación positiva con extraversión, amabilidad, responsabilidad y apertura, mientras que la asociación de estas dimensiones con AN será negativa. Por su lado, neuroticismo mostrará una asociación positiva con AN, y negativa con AP y SV (Hipótesis 5).

Método

Diseño

Se trata de un estudio instrumental (Ato et al., 2013) orientado al estudio de las propiedades psicométricas de dos versiones del BFI-15 (peruana y alemana), tanto en lo que respecta a la estructura interna como a la asociación con otras variables y la confiabilidad.

Participantes

Utilizando un muestreo no probabilístico y por conveniencia, en el presente estudio participaron voluntariamente 1011 estudiantes universitarios chilenos (54.80 % mujeres) de edades comprendidas entre 18 y 30 años (M = 20.55; DE = 2.11). Los estudiantes se encontraban matriculados en diferentes instituciones de educación superior adscritas al Consorcio de Universidades del Estado de Chile, cursando el primero (23 %), segundo (27 %), tercero (30 %) y cuarto año (20 %) y en diversos planes de estudio: psicología (18 %), trabajo social (12 %), ingeniería (25 %), kinesiología (15 %), enfermería (19 %) y física (11 %). Como criterio de inclusión para participar en el estudio se consideró ser mayor de edad y estar matriculado en alguna institución del Consorcio de Universidades del Estado de Chile.

Instrumentos

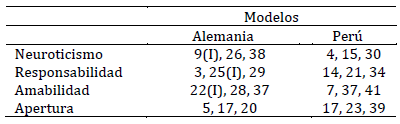

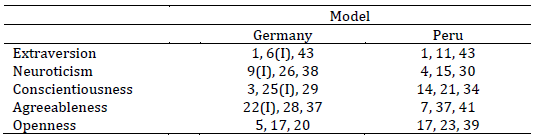

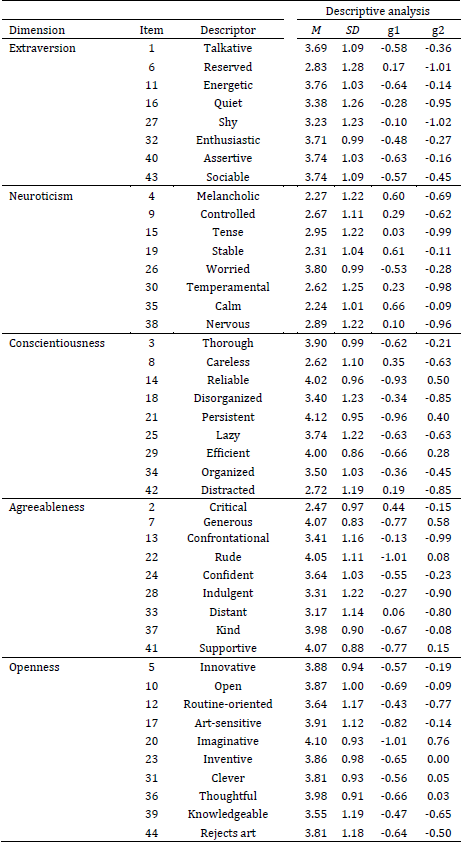

Se utilizó la versión en español del Big Five Inventory (BFI; Benet-Martínez & John, 1998) orientado a la evaluación de la personalidad. El BFI evalúa los 5GF (extraversión, amabilidad, responsabilidad, neuroticismo y apertura) por medio de 44 ítems de cinco opciones de respuesta que van desde Muy en desacuerdo (1) hasta Muy de acuerdo (5). Cabe mencionar que no se usó como base la versión extensa validada en Chile (Lara et al., 2021), ya que no cuenta con algunos ítems necesarios para estructurar las versiones peruana y alemana (ítems 11, 22, 26, 28, 38). De este modo, las versiones de 15 ítems alemana (Gerlitz, & Schupp, 2005) y peruana (Dominguez-Lara & Merino-Soto, 2018a) fueron estructuradas a partir de los ítems del BFI según se muestra en la tabla 1.

Tabla 1: Configuración de cada dimensión según modelo

Nota. I: Ítems inversos.

Además del BFI, se evaluó las tres dimensiones del BS (SV, AP, y AN). Específicamente, se usó la traducción al español de la Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS; Diener et al., 1985) realizada por Atienza et al. (2000). La SWLS evalúa de manera global la satisfacción con la vida a través de cinco ítems con puntuaciones comprendidas entre totalmente en desacuerdo (1) y totalmente de acuerdo (7). En población chilena se han encontrado adecuados indicadores de confiabilidad y validez (Vera-Villarroel et al., 2012).

A su vez, se utilizó la traducción al español del Positive and Negative Affect Schedule (PANAS; Watson et al., 1988) desarrollada por Robles y Paéz (2003). PANAS incluye 20 ítems (10 para afecto negativo y positivo, respectivamente) con opciones de respuesta comprendidas entre muy poco o nada (1) y extremadamente (5). En población chilena se han encontrado adecuados indicadores de confiabilidad y validez (Dufey & Fernández, 2012).

Procedimiento

En primer lugar, con la finalidad de detectar dificultades en la comprensión, se realizó un análisis lingüístico del BFI. En concreto, tres jueces expertos tuvieron la labor de determinar si los ítems del BFI podrían no ser comprendidos por la población objetivo (e.g., estudiantes universitarios chilenos). Durante esta etapa ningún ítem fue objetado ni modificado. En una segunda etapa, a través de los canales institucionales del Consorcio de Universidades del Estado, se envió una invitación a diferentes jefaturas de carrera a participar del estudio. En esta etapa se les envío la documentación relativa a los objetivos y necesidades del estudio a las jefaturas que aceptaron colaborar. En una tercera etapa, el procedimiento incluyó el contacto con los estudiantes en sus respectivas salas de clase, la formalización de su participación a través de un consentimiento escrito que incluía los objetivos y aspectos generales del estudio, y finalmente la aplicación del instrumento de manera individual, anónima y voluntaria, siguiendo un procedimiento de lápiz y papel. Este procedimiento se realizó según los principios de la Declaración de Helsinki (World Medical Association, 1964).

Análisis de datos

En cuanto al análisis descriptivo preliminar, los índices de asimetría y curtosis se consideran aceptables si están alrededor de 2 y 7, respectivamente (Finney & DiStefano, 2006). Con relación al análisis estructural, se implementó un análisis basado en los modelos exploratorios de ecuaciones estructurales (ESEM; Asparouhov & Muthén, 2009) con el método de estimación WLSMV, basado en matrices policóricas, a las dos estructuras propuestas (BFI-15a y BFI-15p). Se usó la rotación target oblicua (ε = .05; Asparouhov & Muthén, 2009), mediante la cual se estimó libremente la carga factorial del ítem del factor principal y las cargas secundarias se especificaron como cercanas a cero (~0).

Los modelos se valoraron con base en sus índices de ajuste, así como por la magnitud de las cargas factoriales (medidas de representatividad del constructo). En este sentido, fueron evaluados el CFI (> .90; Marsh et al., 2004), el RMSEA (< .08; Browne & Cudeck, 1993) y el WRMR (≤ 1.00; DiStefano et al., 2018). Se esperó cargas factoriales cercanas a .60 considerando el número de ítems por dimensión (Dominguez-Lara, 2018). A su vez, en vista que el ESEM provee información de cargas factoriales en los factores secundarios (cargas cruzadas), se calculó el índice de simplicidad factorial (ISF) para valorar la relevancia de estas, de tal manera que un ISF superior a .70 (Fleming & Merino-Soto, 2005) indicarían que el ítem está influido en mayor grado por un solo factor. Para tales fines se usó el programa Mplus versión 7.

La confiabilidad del constructo se estimó con el coeficiente ω (> .70; Hunsley & Marsh, 2008). De forma preliminar al cálculo del coeficiente α se analizó el supuesto de tau-equivalencia (Dunn et al., 2014), o la igualdad estadística de las cargas factoriales dentro de cada dimensión. Así, se consideró la variación del estadístico χ2, en donde una diferencia estadísticamente significativa entre el modelo congenérico y tau-equivalente indica que no se cumple el supuesto. Para este procedimiento se usó el comando DIFFTEST del Mplus (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2006).

En cuanto a la confiabilidad de las puntuaciones, dado el tamaño muestral (> 300) y cantidad de ítems (< 6), se consideró como aceptables magnitudes del coeficiente α de Cronbach por encima de .70 (Ponterotto & Ruckdeschel, 2007). No obstante, en vista de que el coeficiente α es sensible al número de ítems y el cumplimiento de la tau-equivalencia, se implementó el promedio de la correlación entre los ítems (rij > .20; Clark & Watson, 1995).

Posteriormente, se analizó la invarianza de medición de la mejor versión breve entre hombres y mujeres con un análisis factorial multigrupo. Este procedimiento consiste en una restricción gradual de la equivalencia en la estructura interna (invarianza configural), cargas factoriales (invarianza débil), umbrales (invarianza fuerte) y residuales (invarianza estricta) entre los grupos (Pendergast et al., 2017). Así, la invarianza de medición es respaldada según la variación de los índices de ajuste CFI y RMSEA (ΔCFI > -.01, ΔRMSEA < .015; Chen, 2007).

Por último, la asociación entre las dimensiones del BFI-15 y las dimensiones del bienestar subjetivo (satisfacción con la vida, AP y AN) se evaluó con el coeficiente de correlación de Pearson. Se trabajó desde un enfoque de magnitud del efecto y se consideró como significativa una correlación mayor que .20: entre .20 y .50, asociación baja; entre .50 y .80, moderada; por encima de .80, alta (Ferguson, 2009). Cabe mencionar que la asociación entre las dimensiones del BFI-15 se valoró según la magnitud de la correlación interfactorial según los parámetros establecidos anteriormente.

Resultados

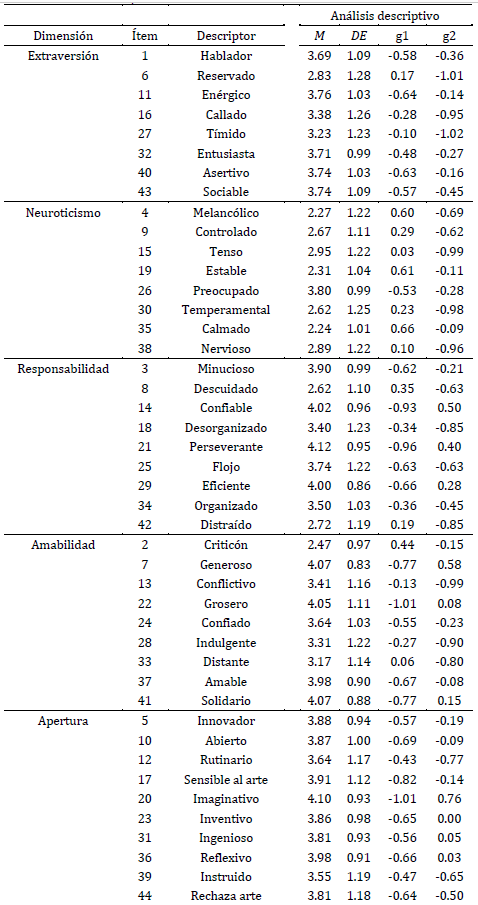

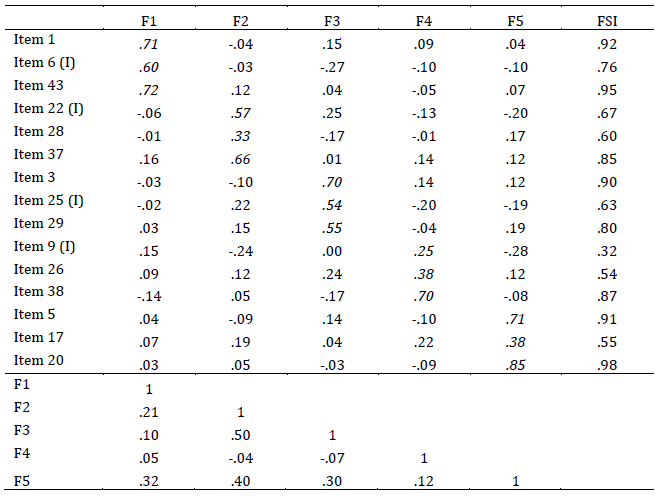

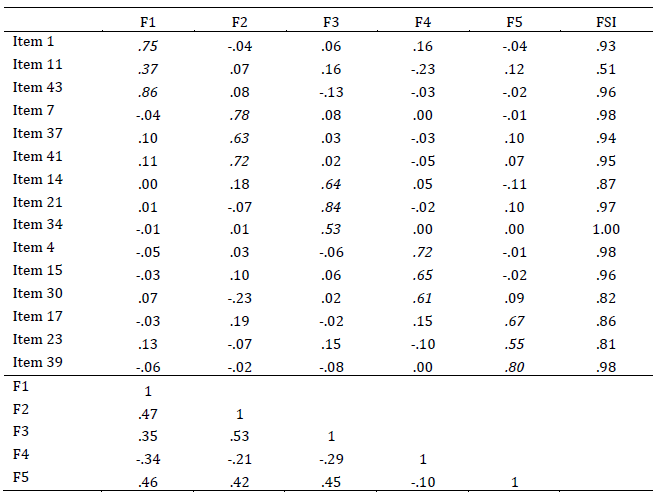

En cuanto al análisis descriptivo, la asimetría y curtosis de todos los ítems fueron aceptables (Tabla 2). En lo que respecta a las evidencias de validez basadas en la estructura interna, tanto el modelo alemán (CFI = .977; RMSEA (90%) = .053 (.044, .062); WRMR = .630) como el peruano (CFI = .995; RMSEA (90%) = .029 (.019, .040); WRMR = .393) tuvieron indicadores aceptables.

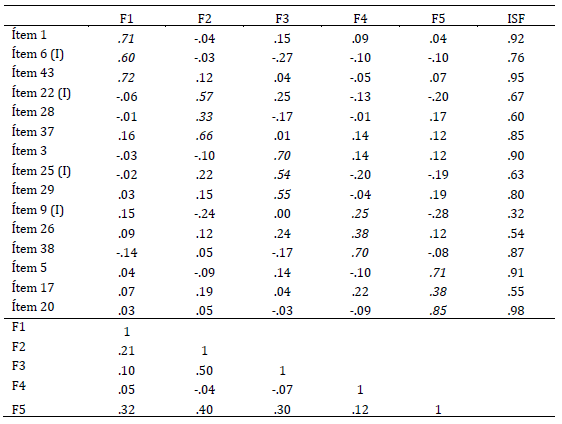

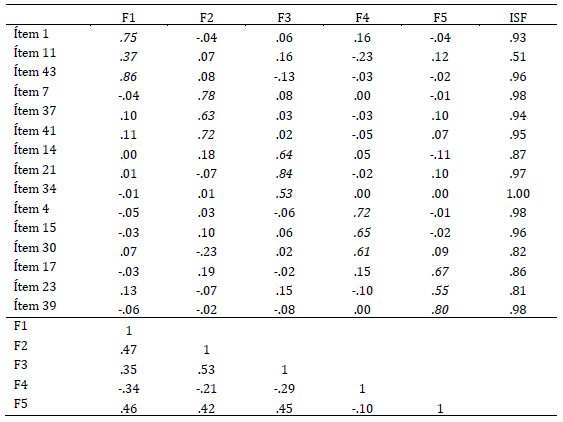

En cuanto a la magnitud de las cargas factoriales, el modelo peruano (Tabla 4) y el alemán (Tabla 3) presentan una y cuatro cargas de magnitud baja (< |.50|), en orden. Por último, el modelo peruano presenta los ítems factorialmente más simples (solo un ítem complejo; Tabla 4), a diferencia del modelo alemán con seis (40 %) ítems complejos (Tabla 3). Si bien la estructura pentafactorial se recupera favorablemente en ambos casos, el modelo más parsimonioso y con mejores parámetros factoriales es el peruano (Hipótesis 1 recibe respaldo).

Por otro lado, en cuanto a las correlaciones interfactoriales, el modelo alemán presentó cinco correlaciones no significativas (< .20), mientras que en el modelo peruano solo se halló una. Por ello, la segunda hipótesis recibe respaldo para el modelo peruano.

Tabla 2: Análisis descriptivo de los ítems

Notas: M: Media; DE: Desviación estándar; g1: asimetría; g2: curtosis.

Tabla 3: Análisis ESEM y simplicidad factorial del BFI-15ª

Notas: (I): Ítem invertido; en cursiva: cargas factoriales en el factor teórico; F1: Extraversión; F2: Amabilidad; F3: Responsabilidad; F4: Neuroticismo; F5: Apertura; ISF: Índice de simplicidad factorial.

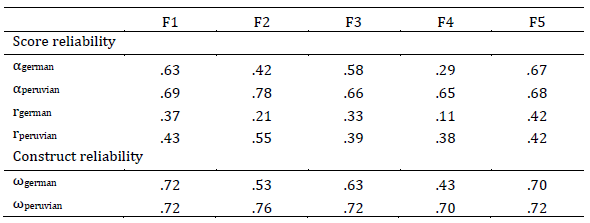

De forma preliminar al análisis de la confiabilidad se analizó la tau-equivalencia, la cual no recibió respaldo en la versión peruana (Δχ2 = 94.47; Δgl = 10; p < .001) ni en la versión alemana (Δχ2 = 138.89; Δgl = 10; p < .001). No obstante, se reporta el coeficiente α para fines descriptivos.

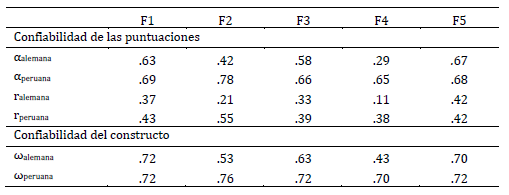

Según la Tabla 5, la versión alemana presenta los indicadores más bajos de confiabilidad del constructo y de puntuaciones. De forma más específica, sobre el coeficiente α, el BFI-15p alcanza magnitudes cercanas al mínimo requerido (≈ .70), aunque la correlación inter-ítem promedio en todos los casos fue aceptable. La versión alemana no llega al mínimo establecido en ambos casos.

Por último, el coeficiente ω alcanza magnitudes aceptables en todas las dimensiones del BFI-15p, y en el BFI-15a solo supera a .70 en dos dimensiones. Entonces, la versión peruana presenta mejores indicadores de confiabilidad del constructo y de puntuaciones (Hipótesis 3).

Tabla 4: Análisis ESEM y simplicidad factorial del BFI-15p

Notas: (I): Ítem invertido; en cursiva: cargas factoriales en el factor teórico; F1: Extraversión; F2: Amabilidad; F3: Responsabilidad; F4: Neuroticismo; F5: Apertura; ISF: Índice de simplicidad factorial.

Tabla 5: Coeficientes de confiabilidad

Notas: F1: Extraversión; F2: Amabilidad; F3: Responsabilidad; F4: Neuroticismo; F5: Apertura; α: coeficiente alfa; r: promedio de la correlación entre ítems; ω: coeficiente omega.

Invarianza de medición según sexo

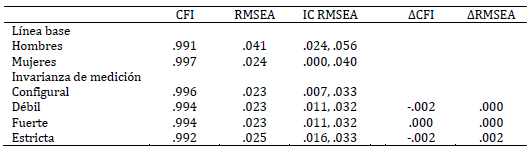

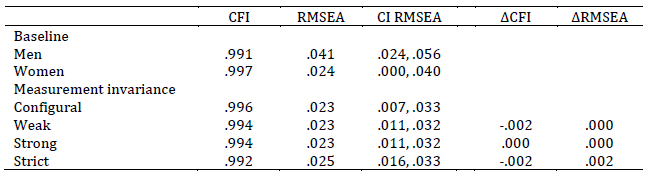

Para esta etapa, solo se consideró la versión peruana, en vista de las características estructurales y de confiabilidad de la versión alemana. De acuerdo con la variación de los índices de ajuste (Tabla 6), existe evidencia de invarianza de medición entre hombres y mujeres (Hipótesis 4).

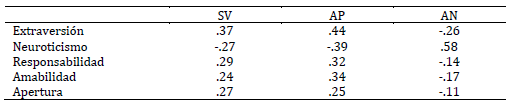

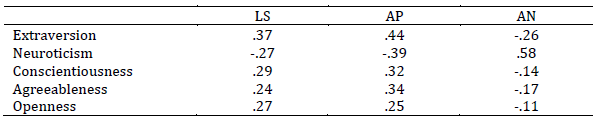

Sobre las evidencias de validez basadas en la relación con otras variables, en términos generales, las dimensiones neuroticismo y responsabilidad muestran un patrón relacional significativo con las dimensiones del BS según lo esperado (Tabla 7). Estos resultados brindan respaldo para la Hipótesis 5.

Tabla 6: Invarianza de medición según sexo y edad

Notas: CFI: Índice de ajuste comparativo; RMSEA: Error de aproximación cuadrático medio; IC: intervalo de confianza; Δ: variación.

Tabla 7: Relación entre bienestar subjetivo y personalidad

Notas: SV: satisfacción con la vida; AP: afecto positivo; AN: afecto negativo.

Discusión

La investigación aquí descrita tuvo como objetivo reunir evidencia de validez basada en la estructura interna de dos versiones del BFI-15 en estudiantes universitarios chilenos, así como su asociación con el BS. Ante las evidencias reportadas, se estima que este objetivo fue alcanzado.

En cuanto al análisis de la estructura interna, aunque la magnitud de los índices de ajuste son un indicio razonable de dimensionalidad, las magnitudes favorables aparecen constantemente en el contexto del análisis ESEM, pero no garantizan una estructura interna sólida debido a la existencia de cargas cruzadas (e.g., Lara et al., 2021). Por ello, es deseable que se valoren otros elementos asociados con la estructura interna, como la magnitud de las cargas factoriales y la simplicidad factorial. Además de garantizar la validez del modelo, los modelos con cargas factoriales inconsistentes o excesivamente complejos pueden indicar problemas con la interpretación de los datos o con la propia estructura del instrumento (Matos & Rodrigues, 2019).

En ese sentido, solo un ítem de la versión peruana del BFI-15 (BFI-15p) muestra una carga baja y es factorialmente complejo en el grupo de participantes chilenos. Pero en la versión alemana (BFI-15a) se observaron más ítems con esas características. Estos resultados coinciden con el estudio realizado en universitarios peruanos (Dominguez-Lara & Merino-Soto, 2018a) en el que la propuesta alemana no prosperó porque los ítems no estaban lo suficientemente asociados para consolidar una dimensión, lo que repercutió tanto en la representatividad del constructo (cargas factoriales por debajo de lo esperado) como en la simplicidad factorial (presencia de ítems factorialmente complejos). Asimismo, los hallazgos son similares a los obtenidos con universitarios mexicanos, en donde la BFI-15p recibió evidencia favorable con respecto a su estructura interna en ese grupo (Dominguez-Lara et al., 2022). Es necesario resaltar que aquellos ítems catalogados como “complejos” en el BFI-15a son los ítems inversos, lo que reafirma la recomendación de minimizar o prescindir de su uso debido a los problemas metodológicos que traen consigo (ver Suárez-Alvarez et al., 2018). Esto se podría explicar por la cercanía cultural (Rammstedt et al., 2013), ya que existen más similitudes de Chile con Perú y México, donde funciona bien el BFI-15p, que con Alemania, donde su versión sí tiene evidencia favorable en países cercanos (e.g., Courtois et al., 2020).

Con relación a la confiabilidad, se destaca el desempeño de la BFI-15p en cuanto a la confiabilidad del constructo (> .70). No obstante, la confiabilidad de las puntuaciones fue determinante, ya que si bien la versión peruana mostró resultados aceptables (≈ .70), no fue el caso de la versión alemana (< .60). Esta situación se torna más compleja si se tiene en cuenta que ninguno de los modelos cumplió la tau-equivalencia, lo que implica que la confiabilidad está infraestimada (Candrinho et al., 2023; Dunn et al., 2014), y dados los valores del coeficiente ω el BFI-15p parece ser el más eficiente. Esto repercute notablemente en la toma de decisiones, ya que se conoce que la magnitud de la confiabilidad de las puntuaciones (coeficiente α) de una variable afecta negativamente los análisis estadísticos posteriores (Merino-Soto, 2020). Además, el coeficiente α depende del número de ítems y del cumplimiento de la tau-equivalencia (Candrinho et al., 2023), por lo que se utilizó de forma complementaria la correlación inter-ítem promedio como medida de confiabilidad de las puntuaciones (Gallego et al., 2024), pero aun en esas circunstancias el BFI-15a tiene mal desempeño en comparación con el BFI-15p.

En ese sentido, solo el BFI-15p presenta un mejor desempeño en la confiabilidad del constructo y puntuaciones. Este panorama se apreció en otros estudios en donde la confiabilidad de las puntuaciones de la versión alemana fue bastante baja (Dominguez-Lara & Merino-Soto, 2018a; Kim et al., 2010; Kunnel et al., 2019), mientras que el BFI-15p presentó coeficientes de mayor magnitud (Dominguez-Lara et al., 2022; Dominguez-Lara & Merino-Soto, 2018a, 2018b).

En vista de estos hallazgos es necesario indicar que la presencia de magnitudes bajas del coeficiente α aun con índices de ajuste aceptables podría asociarse tanto a la brevedad de la escala como a la amplitud del constructo que se evalúa (Stanley & Edwards, 2016). En cualquier caso, se debe tener en cuenta que estas magnitudes no son útiles para la toma de decisiones derivadas del uso individual del instrumento en un entorno profesional, solo es útil para contextos vinculados con la investigación.

Con respecto a la invarianza, se encontró evidencia favorable en hombres y mujeres, por lo que su uso permitirá realizar comparaciones justas. En ese sentido, sería interesante estudiar esas diferencias a futuro, ya que sería un estudio pionero considerando el uso de versiones breves.

La magnitud y dirección de las asociaciones entre las dimensiones del BFI-15p y las dimensiones del BS coinciden con evidencia previa (Anglim et al., 2020; Carmona-Halty & Rojas-Paz, 2014; Jensen et al., 2020; Kobylińska et al., 2022). Esto brinda más evidencias de validez en tanto que un perfil de personalidad caracterizado por bajo neuroticismo, alta extroversión, alta amabilidad y alta responsabilidad facilitaría el desarrollo de perspectivas cognitivas positivas, así como relaciones más estables y satisfactorias (Serrano et al., 2020). Esto es así dado que dependiendo del nivel en determinado rasgo de personalidad, el individuo desarrollará más afectos positivos (o negativos) frente a los diferentes eventos que experimente en su vida, lo que repercutirá directamente en su satisfacción, lo que resulta importante en el contexto universitario.

En cuanto a las implicaciones prácticas de los resultados, el BFI-15p presenta una característica distintiva en comparación con otros instrumentos para este propósito: su cantidad reducida de ítems. Así, su uso reduce la posibilidad de respuestas aleatorias o poco conscientes que podrían afectar los resultados. Además, la parsimonia del BFI-15p reduce la probabilidad de rechazo a participar en encuestas debido a limitaciones de tiempo. Esto es especialmente relevante dado que los investigadores utilizan diversas escalas en los estudios, y el uso de escalas reducidas como el BFI-15p puede minimizar estos problemas. Esto permite, por ejemplo, una aplicación rápida en diversas situaciones, como evaluación psicológica en procesos de selección o investigaciones institucionales para evaluar a sus profesionales. Además, se destaca la importancia de continuar la evaluación de los rasgos de personalidad en el contexto universitario. La especificidad de este contexto requiere una atención especial al bienestar, la calidad de vida y la salud mental de los estudiantes, justificada por las evidencias observadas en los diferentes estudios citados sobre la relación entre estas variables y los rasgos de personalidad. De forma complementaria, resulta de utilidad contar con una versión breve del BFI que presente adecuadas propiedades psicométricas en otros países de la región, ya que ello facilitaría las investigaciones interculturales porque se conoce que, al menos de forma individual, la estructura interna se replica satisfactoriamente. De este modo, de forma conjunta con la validación de la versión extensa en Chile (Lara et al., 2021), se tienen más herramientas a libre disposición para los académicos e investigadores a fin de continuar enriqueciendo el conocimiento acerca del constructo en esta parte del continente dada su relevancia a lo largo de la vida de la persona (Mõttus & Rozgonjuk, 2021).

En cuanto a las fortalezas del estudio, es necesario destacar el tamaño muestral (> 1000), que permitió mayor precisión en las estimaciones. Del mismo modo, debe destacarse el uso del ESEM, ya que actualmente resulta la mejor opción para representar un modelo complejo, como el 5GF, en lugar de un análisis basado en el análisis factorial confirmatorio (e.g., Chiorri et al., 2016). No obstante, también se encontraron limitaciones inherentes al método, como los sesgos asociados a las escalas de autoevaluación, especialmente para este contexto, así como la ausencia de representatividad de los datos con relación a la población universitaria chilena. Si bien el elevado tamaño muestral reduce el error de muestreo, la generalización debe realizarse con cautela.

Se concluye que el BFI-15p es un instrumento que presenta propiedades psicométricas adecuadas para su uso en universitarios chilenos: una estructura interna sólida, indicadores adecuados de confiabilidad, y se asocia coherentemente con las dimensiones del BS, uno de los constructos más importantes y que orienta políticas públicas en países europeos (Calleja & Masón, 2020).

Por último, para futuros estudios de replicación se recomienda el uso de más variables externas para profundizar en el conocimiento sobre la validez de las interpretaciones de los puntajes de esta medida. Además, se pueden emplear otras formas de control de calidad de respuesta para minimizar los sesgos de sobreestimación y subestimación de las características de la personalidad. Sin embargo, considerando el amplio tamaño de la muestra y los procedimientos utilizados en esta investigación, los datos sugieren la adecuación del BFI-15p. Del mismo modo, en futuros estudios se podría utilizar un muestreo de tipo probabilístico, y así realizar un análisis comparativo según el sexo, ya que la argumentación teórica, el análisis del estado del arte y de la evidencia empírica excede los objetivos de este manuscrito. Por último, ayudaría conocer la estabilidad temporal de las dimensiones, así como un análisis de invarianza según país de procedencia debido a la importancia de la personalidad en diferentes contextos (Dash et al., 2019; Thielmann et al., 2020; Zell & Lesick, 2022).

Referencias:

Abdel-Khalek, A. M. (2021). Big-five personality factors and gender differences in Egyptian collge students. Mankind Quarterly, 61(3), 478-496. https://doi.org/10.46469/mq.2021.61.3.6

Angelini, G. (2023). Big fve model personality traits and job burnout: a systematic literature review. BMC Psychology, 11(49), 1-35. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40359-023-01056-y

Anglim, J., Horwood, S., Smillie, L. D., Marrero, R. J., & Wood, J. K. (2020). Predicting psychological and subjective well-being from personality: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 146(4), 279-323. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000226

Araújo, G. R., Ramos, M. C., da Silva, P. G. N., de Melo, C. U., de Araújo, G. O., da Cunha, L. R. L., & de Medeiros, E. D. (2024). Personalidade, variáveis sociodemográficas e cansaço emocional em universitários do nordeste brasileiro. Dedica. Revista de Educação e Humanidades, (22), 1-21. http://doi.org/10.30827/dreh.22.2024.28849

Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2006). Robust chi square difference testing with mean and adjusted test statistics (Mplus Web Notes n.o 10). https://www.statmodel.com/download/webnotes/webnote10.pdf

Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2009). Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 16(3), 397-438. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510903008204

Atienza, F. L., Pons, D., Balaguer, I., & García-Merita, M. L. (2000). Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Satisfacción con la Vida en adolescentes. Psicothema, 12(2), 314-319.

Ato, M., López, J., & Benavente, A. (2013). Un sistema de clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología. Anales de Psicología, 29(3), 1038-1059. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.29.3.178511

Barańczuk, U. (2019). The Five Factor Model of personality and social support: A meta-analysis. Journal of Research in Personality, 81, 38-46. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2019.05.002

Barbachán-Ruales, E. A., Pareja-Pérez, L., Bernardo-Santiago, M., & Solano-Gutiérrez, J. (2018). Preferencias cerebrales, capacidad emprendedora y personalidad eficaz. Una relación necesaria para los estudiantes universitarios de Perú. Investigación y Postgrado, 33(2), 31-49.

Barry, B., & Friedman, R. A. (1998). Bargainer characteristics in distributive and integrative negotiation. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 74(2), 345-359. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.2.345

Benet-Martínez, V., & John, O. P. (1998). Los cinco grandes across cultures and ethnic groups: Multitrait-multimethod analyses of the Big Five in Spanish and English. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 75(3), 729-750. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.75.3.729

Bertoquini, V., & Ribeiro, J. L. P. (2006). Estudo de formas muito reduzidas do Modelo dos Cinco Factores da Personalidade. Psychologica, 43, 193- 210.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. En K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 445-455). Sage.

Bunker, C. J., Saysavanh, S. E., & Kwan, V. S. (2021). Are gender differences in the big five the same on social media as offline? Computers in Human Behavior Reports, 3, 100085. https://doi.org/10.1016/J.CHBR.2021.100085

Bunnett, E. R. (2020). Gender differences in perceived traits of men and women. En The Wiley Encyclopedia of Personality and Individual Differences (pp. 179-184). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119547174.ch207

Calleja, N., & Masón, T. A. (2020). Escala de Bienestar Subjetivo (EBS-20 y EBS-8): construcción y validación. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación – e Avaliação Psicológica, 55(2), 185-201. https://doi.org/10.21865/RIDEP55.2.14

Candrinho, G. C., Almeida, C. S. & Bastos, A. V. B. (2023). Evidências preliminares de validade psicométrica da versão portuguesa do Questionário de Capital Psicológico (PCQ-12) para o contexto moçambicano. Praxis Psy, 39, 1-16. https://doi.org/10.32995/praxispsy.v24i39.223

Carmona-Halty, M. A., & Rojas-Paz, P. P. (2014). Rasgos de personalidad, necesidad de cognición y satisfacción vital en estudiantes universitarios chilenos. Universitas Psychologica, 13(1), 83-93. https://doi.org/10.11144/Javeriana.UPSY13-1.rpnc

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of goodness of fit indexes to lack of measurement invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464-504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834

Chiorri, C., Marsh, H. W., Ubbiali, A., & Donati, D. (2016). Testing the factor structure and measurement invariance across gender of the Big Five Inventory through Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of Personality Assessment, 98(1), 88-99. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2015.1035381

Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1995). Constructing validity: Basic issues in objective scale development. Psychological Assessment, 7(3), 309-319. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.7.3.309

Costa, P., & McCrae, R. (1992). Revised NEO Personality Inventory (NEO-PI-R) and NEO Five-Factor Inventory (NEO-FFI) professional manual. Psychological Assessment Resources.

Courtois, R., Petot, J. M., Plaisant, O., Allibe, B., Lignier, B., Réveillère, C. Lecocq, G., & John, O. (2020). Validation française du Big Five Inventory à 10 items (BFI-10). L'Encéphale, 46(6), 455-462. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.encep.2020.02.006

Dangi, A., Singh, V., & Saini, C. (2020). Different personality affects risk perception differently in online shopping: Investigation of gender impact. Journal of Xian University of Architecture and Technology, 12(2), 414-420.

Dash, G. F., Slutske, W. S., Martin, N. G., Statham, D. J., Agrawal, A., & Lynskey, M. T. (2019). Big Five personality traits and alcohol, nicotine, cannabis, and gambling disorder comorbidity. Psychology of Addictive Behaviors, 33(4), 420-429. https://doi.org/10.1037/adb0000468

Diener, E., Emmons, R., Larsen, J., & Griffin, S. (1985). The Satisfaction with Life Scale. Personality Assessment, 49(1), 71-75. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13

Diener, E., Lucas, R., & Oishi, S. (2002). Subjective well-being: The science of happiness and life satisfaction. En C. Snyder & S. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 63-73). Oxford University Press.

Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Lucas, R. E. (2009). Subjective well-being: the science of happiness and life satisfaction. En C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Oxford Handbook of Positive Psychology (pp. 187-194). Oxford University Press.

DiStefano, C., Liu, J., Jiang, N., & Shi, D. (2018). Examination of the weighted root mean square residual: Evidence for trustworthiness? Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 25(3), 453-466. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2017.1390394

Dominguez-Lara, S. (2018). Propuesta de puntos de corte para cargas factoriales: una perspectiva de fiabilidad de constructo. Enfermería Clínica, 28(6), 401-402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfcli.2018.06.002

Dominguez-Lara, S., & Merino-Soto, C. (2018a). Dos versiones breves del Big Five Inventory en universitarios peruanos: BFI-15p y BFI-10p. Liberabit, 24(1), 81-96. https://doi.org/10.24265/liberabit.2018.v24n1.06

Dominguez-Lara, S., & Merino-Soto, C. (2018b). Estructura interna del BFI-10P y BFI-15P: un estudio complementario con enfoque CFA y ESEM. Revista Argentina de Ciencias del Comportamiento, 10(3), 22-34. https://doi.org/10.32348/1852.4206.v10.n3.21037

Dominguez-Lara, S., Campos-Uscanga, Y., & Valente, S. (2022). Análisis psicométrico de versiones breves del Big Five Inventory en universitarios mexicanos. Avaliação Psicológica, 21(2), 140-149. https://dx.doi.org/10.15689/ap.2022.2102.20163.02

Dominguez-Lara, S., Merino-Soto, C., Zamudio, B., & Guevara-Cordero, C. (2018). Big Five Inventory en universitarios peruanos: Resultados preliminares de su validación. Psykhe, 27(2), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.7764/psykhe.27.2.1052

Dominguez-Lara, S., Prada-Chapoñan, R., & Moreta-Herrera, R. (2019). Diferencias de género en la influencia de la personalidad sobre la procrastinación académica en estudiantes universitarios peruanos. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 22(2), 125-136. https://doi.org/10.14718/acp.2019.22.2.7

Dufey, M., & Fernández, A.M. (2012). Validez y confiabilidad del positive affect and negative affect Schedule (PANAS) en estudiantes universitarios chilenos. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación Psicológica - e Avaliação Psicológica, 34(2), 157-173.

Dunn, T. J., Baguley, T., & Brunsden, V. (2014). From alpha to omega: A practical solution to the pervasive problem of internal consistency estimation. British Journal of Psychology, 105(3), 399-412. https://doi.org/0.1111/bjop.12046

Emmons, R. A. (1986). Personal strivings: An approach to personality and subjective well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 51, 1058-1068. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.51.5.1058

Ferguson, C. J. (2009). An effect size primer: a guide for clinicians and researchers. Professional Psychology: Research and Practice, 40(5), 532-538. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0015808

Fetvadjiev, V., & van der Vijver, F. J. R. (2015). Universality of the five-factor model of personality. En J. D. Wright (Ed.), International Encyclopedia of Social and Behavioral Sciences (pp. 249-253). Elsevier.

Finney, S. J., & DiStefano, C. (2006). Non-normal and categorical data in structural equation modeling. En G. R. Hancock & R. O. Mueller (Eds.), Structural Equation Modeling. A Second Course (pp. 269-314). Information Age Publishing.

Fleming, J., & Merino-Soto, C. (2005). Medidas de simplicidad y ajuste factorial: Un enfoque para la construcción y revisión de escalas derivadas factorialmente. Revista de Psicología, 23(2), 252-266. https://doi.org/10.18800/psico.200502.002

Gallego, F. A., Rojas, C. A., Valencia, O., & Granados, H. (2024). Associations between self-efficacy, mastery, and interest in mathematics technology among university students from Colombia. Formación universitaria, 17(1), 59-68. https://dx.doi.org/10.4067/S0718-50062024000100059

Gerlitz J. Y., & Schupp, J. (2005). Zur Erhebung der Big-Five-basierten Persönlichkeitsmerkmale im SOEP. Dokumentation der Instrumentenentwicklung BFI-S auf Basis des SOEP-Pretests 2005. DIW Research, Notes 4.

Giluk, T. L., & Postlethwaite, B. E. (2015). Big Five personality and academic dishonesty: A meta-analytic review. Personality and Individual Differences, 72, 59-67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.08.027

Guido, G., Peluso, A.M., Capestro, M., & Miglietta, M. (2015). An Italian version of the 10-item Big Five Inventory: An application to hedonic and utilitarian shopping values. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 135-140. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.11.053

Gurven, M., von Rueden, C., Massenkoff, M., Kaplan, H., & Lero Vie, M. (2013). How universal is the Big Five? Testing the five-factor model of personality variation among forager-farmers in the Bolivian Amazon. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(2), 354-370. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0030841

Hunsley, J., & Marsh, E. J. (2008). Developing criteria for evidence-based assessment: An introduction to assessment that work. En J. Hunsley & E. J. Marsh (Eds.), A guide to assessments that work (pp. 3-14). Oxford University Press.

Jensen, R. A. A., Kirkegaard Thomsen, D., O'Connor, M., & Mehlsen, M. Y. (2020). Age differences in life stories and neuroticism mediate age differences in subjective well-being. Applied Cognitive Psychology, 34(1), 3-15. https://doi.org/10.1002/acp.3580

John, O. P., Donahue, E. M., & Kentle, R. L. (1991). The Big Five Inventory–Versions 4a and 54. Institute of Personality and Social Research, University of California, Berkeley.

Kaftan, O. J., & Freund, A. M. (2018). The way is the goal: The role of goal focus for successful goal pursuit and subjective well-being. En E. Diener, S. Oishi, & L. Tay (Eds.), Handbook of Well-Being. DEF Publishers

Kim, S. Y., Kim, J. M., Yoo, J. A., Bae, K. Y., Kim, S. W., Yang, S. J., Shin, I. S., & Yoon, J. S. (2010). Standardization and validation of Big Five Inventory – Korean version (BFI-K) in elders. Korean Journal of Biological Psychiatry, 17(1), 15-25.

Kobylińska, D., Zajenkowski, M., Lewczuk, K., Jankowski, K. S., & Marchlewska, M. (2022). The mediational role of emotion regulation in the relationship between personality and subjective well-being. Current Psychology, 41, 4098-4111. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00861-7

Kunnel, J. R., Xavier, B., Waldmeier, A., Meyer, A., & Gaab, J. (2019) Psychometric Evaluation of the BFI-10 and the NEO-FFI-3 in Indian Adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1057. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01057

Lara, L., Monje, M. F., Fuster-Villaseca, J., & Dominguez-Lara, S. (2021). Adaptación y validación del Big Five Inventory para estudiantes universitarios chilenos. Revista Mexicana de Psicología, 38(2), 83-94.

Liu, W., Li, Z., Ding, C., Wang, X., & Chen, H. (2024). A holistic view of gender traits and personality traits predict human health. Personality and Individual Differences, 222, 112601. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2024.112601

Ljubin-Golub, T., Petričević, E., & Rovan, D. (2019). The role of personality in motivational regulation and academic procrastination. Educational Psychology, 39(4), 550-568. https://doi.org/10.1080/01443410.2018.1537479

Lucas, R. E. (2018). Exploring the associations between personality and subjective well-being. En E. Diener, S. Oishi & L. Tay (Eds.), Handbook of Well-Being (pp. 233-247). DEF Publishers.

Mammadov, S. (2022). Big Five personality traits and academic performance: A meta‐analysis. Journal of Personality, 90(2), 222-255. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12663

Marcos, A. L., Serra, F. A. R., Vils, L & Scafuto, I. C. (2023). Validation of the Big Five Personality Inventory-15 (CBF-PI-15) scale for the Portuguese language and use to assess the project professionals. Revista de Gestão e Projetos (GeP), 14(1), 42-65. https://doi.org/10.5585/gep.v14i1.23210.

Margolis, S., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2018). Cognitive outlooks and well-being. En E. Diener, S. Oishi, & L. Tay (Eds.), Handbook of Well-Being (pp. 129-144). DEF Publishers.

Marsh, H. W., Hau, K. T., & Wen, Z. (2004). In search of golden rules: Comment on hypothesis-testing approaches to setting cutoff values for fit indexes and dangers in overgeneralizing Hu and Bentler’s (1999) findings. Structural Equation Modeling, 11(3), 320-341. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15328007sem1103_2

Matos, D. A. S. & Rodrigues, E. C. (2019). Análise fatorial. Enap.

McAdams, D. P., & Pals, J. L. (2006). A new big five: Fundamental principles for an integrative science of personality. American Psychologist, 61(3), 204-217. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.61.3.204.

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T. (1991). Adding Liebe und Arbeit: The Full Five-Factor Model and Well-being. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 17(2), 227-232. https://doi.org/10.1177/014616729101700217

McCrae, R. R., & Costa, P. T., Jr. (1999). A Five-Factor theory of personality. En L. A. Pervin & O. P. John (Eds.), Handbook of personality: Theory and research (pp. 139-153). Guilford Press.

McCrae, R., & Costa, P. (1997). Personality trait structure as a human universal. American Psychologist, 52, 509-516. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.52.5.509

McCrae, R., & Costa, P. (2004). A contemplated revision of the NEO Five-Factor Inventory. Personality and Individual Differences, 36(3), 587-596. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(03)00118-1

McGeown, S. P., Putwain, D., Simpson, E. G., Boffey, E., Markham, J., & Vince, A. (2014). Predictors of adolescents' academic motivation: Personality, self-efficacy and adolescents' characteristics. Learning and Individual Differences, 32, 278-286. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2014.03.022

McIIloy, D., Poole, K., Ursavas O. M., & Moriarty, A. (2015). Distal and proximal associates of academic performance at secondary level: A mediation model of personality and self-efficacy. Learning and Individual Differences, 38, 1-9. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.lindif.2015.01.004

McKnight, R., Price, J., & Geddes, J. (2019). Personality and its disorders. En R. McKnight, J. Price, & J. Geddes (Eds.), Psychiatry (pp. 465-474). Oxford Academic. https://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198754008.001.0001

Merino-Soto, C. (2020). Consistencia interna del Eysenck Personality Questionnaire - Revised: cuando alfa de Cronbach no es suficiente. Revista Iberoamericana de Diagnóstico y Evaluación – e Avaliação Psicológica, 57(4), 191-203. https://doi.org/10.21865/RIDEP57.4.14

Mõttus, R., & Rozgonjuk, D. (2021). Development is in the details: Age differences in the Big Five domains, facets, and nuances. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 120(4), 1035-1048. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000276

Mõttus, R., Kandler, C., Bleidorn, W., Riemann, R., & McCrae, R. R. (2017). Personality traits below facets: The consensual validity, longitudinal stability, heritability, and utility of personality nuances. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 112(3), 474-490 https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000100

Nunes, C. H., Hutz, C. S., & Giacomoni, C. H. (2009). Associação entre bem-estar subjetivo e personalidade no modelo dos cinco grandes fatores. Avaliação Psicológica, 8(1), 99-108.

Ocansey, G., Addo, C., Onyeaka, H., Andoh-Arthur, J., & Oppong, K. (2020). The influence of personality types on academic procrastination among undergraduate students. International Journal of School & Educational Psychology, 1(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1080/21683603.2020.1841051

Oguntayo, R., Gutiérrez-Vega, M., & Esparza-Del Villar, O. A. (2024). The Psychometric Properties of the Environmental Worry Index. Mental Health: Global Challenges, 7(1), 2-13. https://doi.org/10.56508/mhgcj.v7i1.181

Pendergast, L. L., von der Embse, N., Kilgus, S. P., & Eklund, K. R. (2017). Measurement equivalence: A non-technical primer on categorical multi-group confirmatory factor analysis in school psychology. Journal of School Psychology, 60, 65-82. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2016.11.002

Ponterotto, J. G., & Ruckdeschel, D. E. (2007). An overview of coefficient alpha and a reliability matrix for estimating adequacy of internal consistency coefficients with psychological research measures. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 105(3), 997-1014. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.105.3.997-1014

Prada-Chapoñan, R., Navarro-Loli, J., & Dominguez-Lara, S. (2020). Personalidad y agotamiento emocional académico en estudiantes universitarios peruanos: un estudio predictivo. Revista Digital de Investigación en Docencia Universitaria, 14(2), e1227. https://doi.org/10.19083/ridu.2020.1227

Rammstedt, B. (2007): The 10-Item Big Five Inventory (BFI-10): Norm values and investigation of socio-demographic effects based on a German population representative sample. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 23, 193-201. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759.23.3.193

Rammstedt, B., & John, O.P. (2007). Measuring personality in one minute or less: A 10-item short version of the Big Five Inventory in English and German. Journal of Research in Personality, 41, 203-212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2006.02.001

Rammstedt, B., Kemper, C. J., Klein, M. C., Beierlein, C., & Kovaleva, A. (2013). Eine kurze skala zur messung der fünf dimensionen der persönlichkeit. Methoden, Daten, Analysen, 7(2), 233-249.

Robles, R., & Páez, F. (2003). Estudio sobre la traducción al español y las propiedades psicométricas de las escalas de afecto positivo y negativo (PANAS). Salud Mental, 26(1), 69-75.

Salgado, E., Vargas-Trujillo, E., Schmutzler, J. & Wills-Herrera, E. (2016). Uso del Inventario de los Cinco Grandes en una muestra colombiana. Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana, 34(2), 365-382. http://doi.org/10.12804/apl34.2.2016.10

Sander, P., & Fuente, J. (2020). Undergraduate student gender, personality and academic confidence. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17155567

Schmitt, D. P., Long, A. E., McPhearson, A., O’Brien, K., Remmert, B., & Shah, S. H. (2017). Personality and gender differences in global perspective. International Journal of Psychology, 52(1), 45-56. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12265

Serrano, C., Andreu, Y., & Murgui, S. (2020). The Big Five and subjective wellbeing: The mediating role of optimism. Psicothema, 32(3), 352-358. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2019.392

Stanley, L. M., & Edwards, M. C. (2016). Reliability and Model Fit. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 76(6), 976-985. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164416638900

Steyn, R., & Ndofirepi, T. M. (2022) Structural validity and measurement invariance of the short version of the Big Five Inventory (BFI-10) in selected countries. Cogent Psychology, 9(1), 2095035. https://doi.org/10.1080/23311908.2022.2095035

Suárez-Alvarez, J., Pedrosa, I., Lozano, L.M., García-Cueto, E., Cuesta, M., & Muñiz, J. (2018). Using reversed items in Likert scales: A questionable practice. Psicothema, 30(2), 149-158. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2018.33

Thielmann, I., Spadaro, G., & Balliet, D. (2020). Personality and prosocial behavior: A theoretical framework and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 146(1), 30-90. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000217

van Valkengoed, A. M., Steg, L., & de Jonge, P. (2023). Climate anxiety: A research agenda inspired by emotion research. Emotion Review, 15(4), 258-262. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073923119375

Vedel, A. (2014). The Big Five and tertiary academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 71, 66-76. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.07.011

Vera-Villarroel, P., Urzúa, A., Pavez, P., Celis-Atenas, K., & Silva, J. (2012). Evaluation of subjective well-being: Analysis of the satisfaction with life scale in Chilean population. Universitas Psychologica, 11(3), 719-727.

Watson, D., Clark, L. A., & Tellegen, A. (1988). Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 54(6), 1063-1070. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.54.6.1063

World Medical Association. (1964). Declaration of Helsinki. AMM. http://www.conamed.gob.mx/prof_salud/pdf/helsinki.pdf

Zell, E., & Lesick, T. L. (2022). Big five personality traits and performance: A quantitative synthesis of 50+ meta‐analyses. Journal of Personality, 90(4), 559-573. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12683

Zhang, B., Li, X., Deng, H., Tan, P., He, W., Huang, S., Wang, L., Xu, H., Cao, L., & Nie, G. (2024). The relationship of personality, alexithymia, anxiety symptoms, and odor awareness: a mediation analysis. BMC Psychiatry, 24(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-024-05653-y

Zhang, X., Wang, M-C., He, L., Jie, L., & Deng, J. (2019). The development and psychometric evaluation of the Chinese Big Five Personality Inventory-15. Plos One, 14(8), e0221621. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0221621

Zhao, Y., Niu, J., Huang, J., & Meng, Y. (2024). A bifactor representation of the Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale for children: gender and age invariance and implications for adolescents’ social and academic adjustment. Child Adolescent Psychiatry and Mental Health, 18(27). 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13034-024-00717-z

Zuo, X., Zhao, L., Li, Y., Yu, C., & Wang, Z. (2024). Psychological mechanisms of English academic stress and academic burnout: the mediating role of rumination and moderating effect of neuroticism. Frontiers in Psychology, 15, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2024.1309210

Disponibilidad de datos: El conjunto de datos que apoya los resultados de este estudio no se encuentra disponible.

Cómo citar: Dominguez-Lara, S., Carmona-Halty, M., Schulmeyer, M. K., Valente, S. N., & Lourenço, A. A. (2024). Análisis psicométrico de dos versiones del Big Five Inventory-15 en estudiantes universitarios chilenos: estructura interna, invarianza de medición y asociación con bienestar subjetivo. Ciencias Psicológicas, 18(1), e-3369. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v18i1.3369

Contribución de los autores (Taxonomía CRediT): 1. Conceptualización; 2. Curación de datos; 3. Análisis formal; 4. Adquisición de fondos; 5. Investigación; 6. Metodología; 7. Administración de proyecto; 8. Recursos; 9. Software; 10. Supervisión; 11. Validación; 12. Visualización; 13. Redacción: borrador original; 14. Redacción: revisión y edición.

S. D.-L. ha contribuido en 1, 2, 6, 13; M. C.-H. en 1, 2, 6, 13; M. K. S. en 1, 13; S. N. V. 13, 14; A. A. L. en 13, 14.

Editora científica responsable: Dra. Cecilia Cracco.

10.22235/cp.v18i1.3369

Original Articles

Psychometric analysis of two versions of the Big Five Inventory -15 in Chilean college students: internal structure, measurement invariance and association with subjective well-being

Análisis psicométrico de dos versiones del Big Five Inventory-15 en estudiantes universitarios chilenos: estructura interna, invarianza de edición y asociación con bienestar subjetivo

Análise psicométrica de duas versões do Big Five Inventory -15 em estudantes universitários chilenos: estrutura interna, invariância de medição e associação com bem-estar subjetivo

Sergio Dominguez-Lara1, ORCID 0000-0002-2083-4278

Marcos Carmona-Halty2, ORCID 0000-0003-4475-1175

Marion K. Schulmeyer3, ORCID 0000-0002-0707-0656

Sabina N. Valente4, ORCID 0000-0003-2314-3744

Abílio A. Lourenço5, ORCID 0000-0001-6920-0412

1 Universidad de San Martín de Porres, Peru, [email protected]

2 Universidad de Tarapacá, Chile

3 Universidad Privada de Santa Cruz de la Sierra, Bolivia

4 Instituto Politécnico de Portalegre; Universidade de Évora, Portugal

5 Universidade do Minho, Portugal

Abstract:

The purpose of this research was to analyze the internal structure of the Big Five Inventory-15 (BFI-15), measurement invariance and its association with subjective well-being, in Chilean college students. A sample of 1011 college students (female = 54.80%; Mage = 21.55 years; SDage = 2.11 years) was used. Results showed the Peruvian version of BFI-15 (BFI-15p) has more consistent indicators regarding their internal structure (e.g., factor loadings) compared to the German (BFI-15a) version, an invariant structure between men and women, and a significant association with subjective well-being was found. Finally, the construct reliability and scores reliability reached adequate magnitudes. It is concluded that the BFI-15p has adequate psychometric properties for use in Chilean college students.

Keywords: personality; subjective well-being; validity; reliability.

Resumen:

El objetivo de esta investigación fue analizar la estructura interna de dos versiones del Big Five Inventory-15 (BFI-15), invarianza de medición y su relación con el bienestar subjetivo en estudiantes universitarios chilenos. Participaron 1011 estudiantes (mujeres = 54.80 %; Medad = 21.55 años; DEedad = 2.11 años). Los resultados indican que la versión peruana del BFI-15 (BFI-15p) tiene indicadores más consistentes con relación a su estructura interna (e.g., cargas factoriales) en comparación a la versión alemana (BFI-15a), así como una estructura invariante entre hombres y mujeres, y una asociación significativa con las dimensiones del bienestar subjetivo. Finalmente, la confiabilidad del constructo y de las puntuaciones alcanzó magnitudes adecuadas. Se concluye que el BFI-15p presenta propiedades psicométricas adecuadas para su uso en universitarios chilenos.

Palabras clave: personalidad; bienestar subjetivo; validez; confiabilidad.

Resumo:

O objetivo desta investigação foi analisar a estrutura interna de duas versões do Big Five Inventory-15 (BFI-15), invariância de medição e a sua relação com o bem-estar subjetivo em estudantes universitários chilenos. Participaram 1011 estudantes universitários (mulheres = 54.80%; Midade = 21.55 anos; DPidade = 2.11 anos). Os resultados indicam que a versão peruana do BFI-15 (BFI-15p) tem indicadores mais consistentes em relação à sua estrutura interna (por exemplo, cargas fatoriais) em comparação com a versão alemã (BFI-15a), bem como uma estrutura invariante entre homens e mulheres, e uma associação significativa com as dimensões do bem-estar subjetivo. Por fim, a confiabilidade do construto e das pontuações atingiram magnitudes adequadas. Conclui-se que o BFI-15p apresenta propriedades psicométricas adequadas para uso em estudantes universitários chilenos.

Palavras-chave: personalidade; bem-estar subjetivo; validade; confiabilidade.

Received: 27/05/2023

Accepted: 15/05/2024

The model of the Big Five factors

Personality is typically regarded as the set of characteristics that make an individual think, feel, and act in a unique way (McKnight et al., 2019), and, at its extreme, as a superordinate construct that encompasses various cognitive and non-cognitive elements (Dangi et al., 2020). Therefore, it refers to the individual's particularity and what distinguishes them from everyone else, as well as a set of stable and enduring psychological traits across time and situations, which allows for establishing a characteristic style of interaction with the physical and social context (Mõttus et al., 2017). According to Barbachán-Ruales et al. (2018), university students possess a multitude of traits intrinsic to their personality; however, this are revealed effectively when manifested in circumstances susceptible to being interpreted in the light of self-awareness. In this line, motivational agents are sought to drive them to study and face the challenges outlined in the educational sphere, granting them hope to achieve their aims and purposes.

Personality could be conceived as a system determined by traits and dynamic processes that intervene in the individual psychological process, and although there are some approaches that highlight these elements, the model of the Big Five factors (BFF) (McCrae & Costa, 1999, 2004) is one of the most important and is the most recognized taxonomy for assessing personality traits (Zhang et al., 2019). Over the last decades, the BF model has been acknowledged as a primordial representation of prominent and non-pathological personality traits, whose modification contributes to the emergence of personality disorders, such as antisocial, borderline, and narcissistic disorders (Angelini, 2023).

The BFF model indicates that individuals are characterized by a pattern of thoughts, feelings, and actions that can be grouped around five dimensions: neuroticism, extraversion, openness, agreeableness, and conscientiousness (McCrae & Costa, 2004). Its validity, universality, and longitudinal stability have been supported by empirical research (e.g., McAdams & Pals, 2006), as this model tends to be stronger in Western cultures than in non-Western ones, as well as with similar levels of education and income (Rammstedt et al., 2013). However, it is also known that it does not replicate in some contexts (e.g., Fetvadjiev & van der Vijver, 2015), as modifications made to various scales alter both the instrument and the interpretations of the items (e.g., Fetvadjiev & van der Vijver, 2015), which drives the creation of other theoretical personality models oriented towards specific idiosyncrasies (e.g., Gurven et al., 2013). This suggests that cultural and ethnic differences can influence how personality traits are expressed and perceived. Although the Big Five model provides a relevant framework for understanding human personality, it is important to recognize the need for complementary approaches in certain cultures and ethnicities.

The first dimension, neuroticism, is characterized by the tendency to experience negative affect (sadness, fear, anger, guilt, etc.), being associated with emotional stability and emotion management, which translates into vulnerability and anxiety (Zhang et al., 2024). Thus, it can predict a lower ability to cope with adverse events (Angelini, 2023; Zuo et al., 2024). The second dimension, extraversion, is associated with a sociable state characterized by assertiveness and confidence, meaning those who appreciate socializing with others and teamwork, who are emotionally positive (Bertoquini & Ribeiro, 2006), and are capable of individually impacting the interaction of the belonging group (Barry & Friedman, 1998). The third dimension called openness is related to imagination, curiosity, originality, diversified and non-traditional interests, proactive intellectual activity, and preference for tasks involving cognitive complexity (McCrae & Costa, 1997). The fourth dimension, agreeableness, is characterized by sympathy, flexibility, trust, tolerance, and concern for others, with a prosocial orientation and preference for the development of group activities (Costa & McCrae, 1992), which would facilitate the establishment of positive interpersonal relationships. The last dimension, conscientiousness, refers to organization, self-discipline, persistence, prudence, and planning ability (Kaftan & Freund, 2018) to achieve personal goals, as well as being associated with greater self-control and a lower level of aggressive externalization (McCrae & Costa, 1999).

As previously stated, personality assessment is relevant in the university setting for both research purposes and applied contexts, either due to its evolutionary relevance regarding differences according to sex or age (e.g., Zhang et al., 2024; Zhao et al., 2024), or its association with relevant variables such as academic performance (conscientiousness; Vedel, 2014), academic motivation (neuroticism and conscientiousness; McGeown et al., 2014), procrastination (neuroticism and openness; Ocansey et al., 2020), motivational self-regulation (conscientiousness; Ljubin-Golub et al., 2019), academic dishonesty (conscientiousness and agreeableness; Giluk & Postlethwaite, 2015), academic self-efficacy (conscientiousness and openness; McIIloy et al., 2015), social support (extraversion; Barańczuk, 2019), academic burnout (neuroticism; Prada-Chapoñan et al., 2020; agreeableness and neuroticism; Araújo, 2024), or subjective well-being (Nunes et al., 2009).

Personality and Gender Differences

Evolutionary or sociocultural differences between men and women are evident in the manifestation of their behaviors in specific environments (Schmitt et al., 2017), making it relevant to have valid and reliable measures to expose these differences. For example, previous studies indicate that sex differences with respect to the Big Five personality traits are inconclusive, as while female university students show higher scores in all five personality traits (Bunker et al., 2021; Sander & Fuente, 2020), other studies show that women scored higher in extraversion, agreeableness, and neuroticism than men (Liu et al., 2024), and for other authors, men score higher in openness, extraversion, and conscientiousness (Abdel-Khalek, 2021). On the other hand, in other studies, women were found to score higher in extraversion, conscientiousness, and openness, while scoring similarly in agreeableness and neuroticism (Bunnett, 2020; Dominguez-Lara et al., 2019). However, sometimes groups are compared without providing evidence of measurement invariance (Pendergast et al., 2017), which could lead to questioning the legitimacy of the differences found as they could be attributed to aspects unrelated to the construct (bias).

Personality and subjective well-being

Subjective well-being (SWB) refers to a set of emotional and cognitive assessments made about various areas of life (Diener et al., 2009). On one hand, the cognitive dimension corresponds to life satisfaction (LS), which is the overall evaluation process of one's life (Emmons, 1986) that arises from the comparison between the individual's current and ideal life circumstances, considering important elements such as goals, values, or culture (Calleja & Masón, 2020). On the other hand, the emotional dimension is constituted by positive affect (PA) and negative affect (NA; Diener et al., 2002), which represent emotional elements (pleasure, happiness, distress, etc.). Thus, high SWB includes various positive emotional experiences, few negative emotional experiences (e.g., depression or anxiety), and LS understood as a whole. In this way, it is understood that different life trajectories, personality traits, brain architecture, as well as the environment and culture in which individuals find themselves, influence the individual and subjective perspective of well-being (Oguntayo et al., 2024; van Valkengoed et al., 2023).

In this line of thought, one of the most studied predictors of SWB is personality (Lucas, 2018), specifically from the Big Five model, providing two explanations about the association between these constructs. Firstly, there is talk of a temperamental model, which explains the direct relationships between underlying physiological systems and the affective experiences individuals have, and secondly, an instrumental model that understands well-being as an indirect outcome of the conditions individuals create based on their personality traits (Lucas, 2018; McCrae & Costa, 1991).