10.22235/cp.v18i1.3297

Escala de Forças de Caráter: novas evidências de validade

Character Strengths Scale: new validity evidence

Escala de Fortalezas del Carácter: nuevas evidencias de validez

Rafael Moreton Alves da Rocha1, ORCID 0000-0003-2291-2986

Camila Grillo Santos2, ORCID 0000-0002-2123-9083

Henrique Vazquez Gonzalez3, ORCID 0000-0002-6109-4894

Ana Paula Porto Noronha4, ORCID 0000-0001-6821-0299

1 Programa de Pós-Graduação Stricto Sensu em Psicologia, Universidade São Francisco, Brasil, [email protected]

2 Programa de Pós-Graduação Stricto Sensu em Psicologia, Universidade São Francisco, Brasil

3 Programa de Pós-Graduação Stricto Sensu em Psicologia, Universidade São Francisco, Brasil

4 Programa de Pós-Graduação Stricto Sensu em Psicologia, Universidade São Francisco, Brasil

Resumo:

As forças pessoais são consideradas como

construto da personalidade com aspecto positivo, indicando uma vida

satisfatória e autêntica. A Escala de Forças de Caráter (EFC) é a única que se

tem conhecimento que avalia as forças pessoais dos brasileiros. A literatura

aponta que a estrutura proposta, das 24 forças pessoais divididas em 6

virtudes, não é replicada empiricamente. Estudos tem comparado as forças de

caráter entre homens e mulheres e entre etapas do desenvolvimento, porém,

compreender a equivalência do instrumento entre os grupos deve preceder tais

comparações. Este estudo objetiva testar a estrutura fatorial da EFC encontrada

por Noronha e Batista (2020) e avaliar a invariância do construto entre:

adolescentes e adultos, sexo em adolescentes, sexo em adultos. Para o primeiro

objetivo, empregou-se uma Análise Fatorial Confirmatória (AFC), que corroborou

a estrutura testada. Para o segundo, avaliou-se a invariância dos fatores da

escala entre os grupos a partir da AFC-Multigrupo, que apontou alguns fatores

como equivalentes e outros não. Pode-se concluir que a estrutura fatorial

testada é empiricamente pertinente e que, ao comparar médias das forças entre

os grupos em estudos futuros com a EFC, os autores devem se atentar a quais

forças pertencem a fatores invariantes.

Palavras-chave: avaliação

psicológica; psicometria; psicologia positiva; personalidade.

Abstract:

The aim of the study was to identify instruments used to assess the

Character strengths are considered a positive aspect of personality, indicating

a satisfying and authentic life. The Character Strengths Scale is the only

known measure that evaluates personal strengths of Brazilians. The literature

suggests that the proposed structure of 24 character strengths divided into six

virtues is not empirically replicated. Studies have compared character

strengths between men and women and across stages of development; however,

understanding the equivalence of the instrument across groups should precede

such comparisons. This study aims to test the factor structure of the Character

Strengths Scale found by Noronha and Batista (2020) and evaluate the

construct’s invariance among adolescents and adults, as well as between sexes

in adolescents and adults. For the first objective, Confirmatory Factor

Analysis (CFA) was employed, which supported the tested structure. For the second,

the equivalence of the scale factors between groups was evaluated using

Multi-Group CFA, which identified some factors as equivalent and others as not.

It can be concluded that the tested factor structure is empirically relevant

and that, when comparing strength means between groups in future studies using

the Character Strengths Scale, authors should pay attention to which strengths

belong to invariant factors.

Keywords: psychological assessment; psychometrics; positive psychology;

personality.

Resumen:

Las fortalezas del carácter se consideran

un aspecto positivo de la personalidad que indica una vida satisfactoria y

auténtica. La Escala de Fortalezas del Carácter (EFC) es la única medida

conocida que evalúa las fortalezas personales de los brasileños. La literatura

sugiere que la estructura propuesta de 24 fortalezas divididas en seis virtudes

no se replica empíricamente. Los estudios han comparado las fortalezas del

carácter entre hombres y mujeres, y en diferentes etapas del desarrollo; sin embargo,

comprender la equivalencia del instrumento entre grupos debe preceder a tales

comparaciones. Este estudio tiene como objetivo probar la estructura factorial

de la EFC encontrada por Noronha y Batista (2020) y evaluar la invarianza del

constructo entre: adolescentes y adultos, sexo en adolescentes, sexo en

adultos. Para el primer objetivo, se utilizó el Análisis Factorial

Confirmatorio (CFA) que respaldó la estructura probada. Para el segundo, se

evaluó la equivalencia de los factores de la escala entre grupos utilizando el

CFA Multigrupo, que identificó algunos factores como equivalentes y otros no.

Se puede concluir que la estructura factorial probada es empíricamente

relevante y que, al comparar las medias de las fortalezas entre grupos en

futuros estudios utilizando la EFC, los autores deben prestar atención a qué

fortalezas pertenecen a factores invariantes.

Palabras clave: evaluación

psicológica; psicometría; psicología positiva; personalidad.

Recebido: 21/03/2023

Aceito: 06/03/2024

Dessa maneira, as forças de caráter podem ser entendidas como atributos positivos fundamentais, os traços de personalidade positivos, para que a pessoa tenha uma vida plena e feliz (Noronha & Reppold, 2019). Park (2009) complementa tal definição definindo-as como traços singulares que podem ser expressos por pensamentos, ações, sentimentos. Recentemente, Noronha e Reppold (2021) sugeriram que a tradução mais adequada de character strengths para o português seria forças pessoais. Por esta razão, a partir deste momento, usaremos tal nomenclatura.

As forças pessoais condizem com os aspectos saudáveis da personalidade dos indivíduos sendo crucial a utilização deste construto psicológico na práxis. Elas são estáveis nos sujeitos, mas suscetíveis a serem intensificadas e precisam ser analisadas de acordo com o desenvolvimento da pessoa e o âmbito que está inserida (Reppold et al., 2021). Existem pesquisas de intervenção relacionadas às forças pessoais com resultados satisfatórias. Como na área clínica que elas promovem o aumento da autoestima, felicidade, autoeficácia; na hospitalar observou-se um crescimento da qualidade de vida e adesão ao tratamento; no contexto escolar as forças pessoais auxiliam no aumento do desempenho escolar e diminuição de situações de bullying, bem como ocorrências de sintomas associados a humor deprimido e ansiedade; no âmbito familiar contribui no entendimento das relações familiares e no aprofundamento da conscientização da dinâmica entre seus membros (Noronha & Reppold, 2019; Reppold et al., 2021). Para uma eficácia interventiva em diversos contextos com as forças pessoais se faz necessário um instrumento com qualidade teórica, técnica, científica robusta.

Com a publicação da classificação das forças pessoais, pesquisas foram realizadas com vistas a avançar nas compreensões teóricas e nas comprovações empíricas. Desta feita, instrumentos que acessassem as forças de pessoais foram construídos, sendo que, o mais recorrentemente encontrado na literatura internacional é o Values in Action (VIA; Peterson & Seligman, 2004). O VIA permitiu que pesquisas fossem desenvolvidas em muitos países como África do Sul, Croácia, Israel, Índia, Alemanha, entre outros (Noronha et al., 2015). No contexto brasileiro, com base no VIA, foi desenvolvida por Noronha e Barbosa (2016) a Escala de Forças de Caráter (EFC). Esta é composta por 71 itens que avaliam as 24 forças sendo que a escala conta com 3 itens para cada uma delas, exceto Apreciação do Belo que conta com apenas 2 itens. Cabe reiterar, que a EFC não se trata de uma adaptação do VIA, apenas o teve como referencial.

EFC é a única escala que se tem conhecimento que avalia as forças pessoais de brasileiros. Há uma versão em português do VIA-IS, no entanto, os estudos de validade realizados por Seibel et al. (2015) apontaram para algumas fragilidades. Neste estudo os autores analisaram a estrutura fatorial da versão em português brasileiro do VIA-IS. Primeiramente, usaram como método de retenção de fatores a análise paralela, que apontou para uma solução de três ou quatro fatores. Então, realizaram a Análise Fatorial Exploratória para ambas as possiblidades, agrupando os itens correspondentes a cada força pessoal. Porém, tanto na solução de três quanto na de quatro fatores, várias das forças pessoais apresentaram cargas cruzadas (cargas acima de 0,30 em mais de um fator). Os autores então optaram por considerar a solução proposta pelo método de Hull, que diferentemente da análise paralela, sugeriu a solução unifatorial para a VIA-IS, argumentando que as forças seriam todas interligadas e que, portanto, não deveriam ser divididas em virtudes. Nenhuma das soluções encontradas, acatam a divisão das forças em seis virtudes, conforme proposto originalmente por Peterson e Seligman (2004). Na realidade, os achados apontam para fragilidades psicométricas dos resultados, especialmente, no que tange as soluções multifatoriais para a escala (Seibel et al., 2015).

Em relação à EFC, foram realizadas várias investigações com vistas a buscas de evidências de validade. No tocante às evidências de validade com base na estrutura interna, por exemplo, os autores publicaram três estudos, sendo que os resultados foram distintos entre si. O primeiro deles, por não ter encontrado a estrutura teórica de seis virtudes, propôs uma interpretação unidimensional para a EFC (Noronha et al., 2015). O estudo foi realizado com fatores de segunda ordem, guiando-se por intermédio das 24 forças pessoais. No entanto, com o avanço das pesquisas, ficou elucidado que a interpretação de um escore geral de forças pessoais tinha pouca ou nenhuma utilidade.

Isto posto, os autores testaram em dois outros artigos diferentes estruturas. Noronha e Zanon (2018) em um estudo com amostra composta por 981 universitários apontaram uma solução de três fatores para a EFC (intelecto, intrapessoal e coletivismo e transcendência). Os autores argumentam que, apesar de encontrarem índices de ajuste melhores nas estruturas testadas com maior número de dimensões, a solução com três fatores era a única que fazia sentido e se sustentava do ponto de vista teórico.

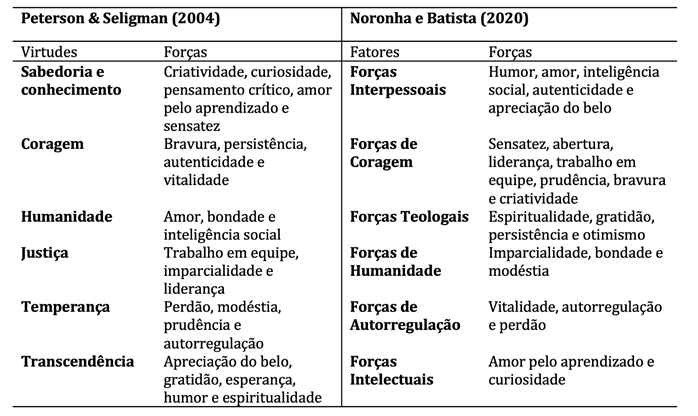

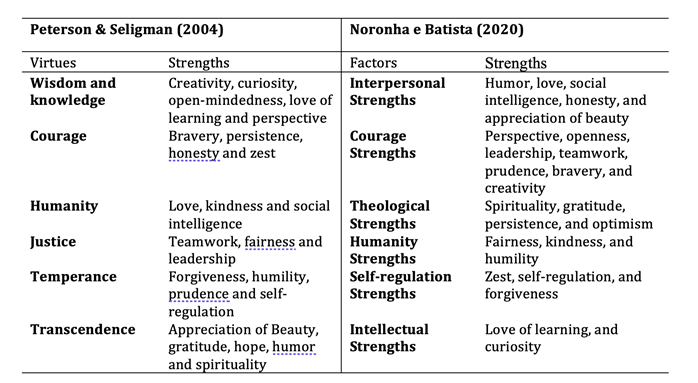

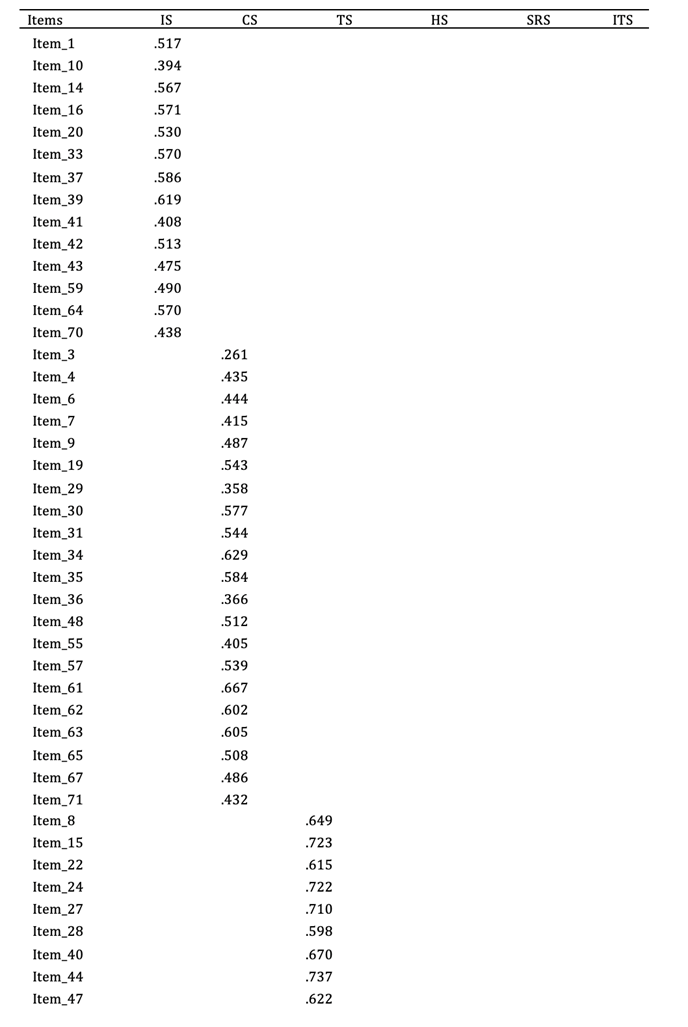

Posteriormente, Noronha e Batista (2020) em um estudo com amostra composta por 1,500 universitários, identificaram, a partir de uma Análise Fatorial Exploratória, uma solução de 6 fatores para o instrumento. No entanto, a classificação teórica de Peterson e Seligman (2004) não foi replicada (ver Tabela 1). No referido estudo, diversos itens obtiveram cargas fatoriais cruzadas, de modo que os autores propuseram a alocação destes nos seus respectivos fatores, não somente a partir da carga fatorial, mas também pautados no aspecto teórico. Os itens foram distribuídos entre os seguintes fatores propostos: Forças Interpessoais (FI); Forças de Coragem (FC); Forças Teologais (FT); Forças de Humanidade (FH); Forças de Autorregulação (FA) e Forças Intelectuais (FINT).

Tabela 1: Distribuição das forças pessoais proposta por Peterson e Seligman (2004) e distribuição encontrada por Noronha e Batista (2020)

Também foram realizados estudos com vistas à busca de evidências de validade com variáveis externas de construtos relacionados como personalidade, estilos parentais e suporte social. Os fatores de personalidade Extroversão e Socialização foram mais explicativas das forças pessoais. Quanto aos estilos parentais, as forças se associam com maiores magnitudes com a responsividade, que interpreta o afeto, envolve sensibilidade, aceitação e compromisso (Noronha & Batista, 2017, 2020; Noronha & Campos, 2018; Noronha & Reppold, 2019).

Temática recente referente às forças pessoais refere-se às diferenças de endosso entre grupos diferentes (e.g. homens e mulheres; adolescentes e adultos). Meta-análises recentes apontam que os achados dos estudos são divergentes sobre quais forças seriam predominantes entre os grupos citados (Heintz et al., 2019; Heintz & Ruch, 2022). Porém, antes de analisar eventuais diferenças, é necessário investigar se o instrumento utilizado para avaliar as forças pessoais mede o mesmo construto entre os grupos. Em outras palavras, se o instrumento é invariante entre eles (Damásio, 2013).

A análise de invariância pode ser realizada a partir de três modelos, quais sejam, (1) Configural, que indica se o número de fatores e o número de itens por fator são adequados para ambos os grupos; (2) Métrica, que indica a equivalência das cargas fatoriais dos itens entre os grupos; (3) Escalar, que indica que os interceptos (nível de traço latente necessário para endossar as categorias dos itens) são equivalentes para os grupos. Assim, caso a invariância não seja evidenciada, por exemplo, ao comparar as médias de homens e mulheres no construto, o pesquisador pode encontrar uma diferença entre os sexos explicada pelo erro de medida e não propriamente por uma diferença real do construto entre eles (Fischer & Karl, 2019; Peixoto & Martins, 2021).

Desta forma, o presente estudo conta com os seguintes objetivos: (1) testar a estrutura fatorial da EFC no modelo de 6 fatores encontrado por Noronha e Batista (2020) a partir de uma AFC, buscando evidências de validade com base na estrutura interna do construto (American Educational Research Association (AERA) et al., 2014); (2) testar a invariância da EFC entre adolescentes e adultos; (3) testar a invariância da EFC entre homens e mulheres adolescentes; (4) testar a invariância da EFC entre homens e mulheres adultos.

Método

Participantes

A amostra deste estudo foi constituída por 4,522 participantes, com idades entre 13 e 65 anos (M = 22,12; DP = 7,623) sendo que 62,7 % reportaram ser do sexo feminino. Posteriormente, para a análise de invariância da escala entre os sexos de adultos e de adolescentes a amostra foi separada em duas subamostras. A subamostra de adultos contou com 3,549 sujeitos, com idades de 18 a 65 anos (M = 23,86; DP = 7,723), sendo que 62,4 % relataram ser do sexo feminino. A subamostra de adolescentes contou com 973 sujeitos, com idades de 13 a 17 anos (M = 15,76: DP = 1,008), sendo que 63,8 % relataram ser do sexo feminino.

Instrumentos

Questionário sociodemográfico: este questionário foi elaborado para o presente estudo visando coletar informações sobre sexo e idade dos participantes.

Escala de Forças de Caráter (EFC; Noronha & Barbosa, 2016). A escala é composta por 71 afirmações com respondidas em escala Likert de cinco pontos (0 = nada a ver comigo; 4 = tudo a ver comigo). O instrumento foi desenvolvido para avaliar 24 forças pessoais, organizadas em seis virtudes, de acordo com a definição de Peterson e Seligman, (2004). Cada força é representada por três itens, exceto a força Apreciação do Belo que conta com apenas dois. O resultado é calculado a partir da soma do valor dos itens respondidos. O modelo de 6 fatores proposto por Noronha e Batista (2020) conta com bons índices de consistência interna: FI (α = 0,89); FC (α = 0,88); FT (α = 0,93; FH (α = 0,91); FA (α = 0,83) e FINT (α = 0,88).

Procedimentos

O projeto foi submetido ao Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa. Após aprovação (Parecer n.º 365.343), foi conduzida a coleta de dados de forma presencial (caneta e papel). As aplicações ocorreram sempre nas dependências das instituições de ensino, sendo que para os menores de idades se deu em escolas e, para os maiores, em universidades. Os participantes maiores de 18 anos assinaram o Termo de Consentimento Livre e Esclarecido (TCLE). Por sua vez, para a coleta nas escolas, após a autorização dos diretores, estabeleceu-se um cronograma, de modo que inicialmente foi explicado o objetivo da pesquisa e foi entregue o TCLE para pais. Após o recebimento dos TCLE assinados, foram marcados os horários da coleta. As aplicações ocorreram nos horários de aula, após a assinatura ao Termo de Assentimento Livre e Esclarecido (TALE). Para todos os participantes, os questionários foram apresentados na seguinte ordem: questionário sociodemográfico e Escala de Forças de Caráter. Estimou-se que o formulário tenha sido concluído em aproximadamente 20 minutos.

Análise de dados

Para avaliar a estrutura fatorial da escala, realizou-se uma AFC conduzida a partir do software R (R Core Team, 2022), por meio do pacote lavaan (Rosseel, 2012), com método de estimação weighted least square mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV; Asparouhov & Muthén, 2010). Para avaliação do ajuste dos modelos foram considerados os índices: χ², graus de liberdade (gl), Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Standardized Root Mean Residual (SRMR), Comparative Fit Index (CFI) e Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI). Estes são considerados adequados quando valores de RMSEA e SRMR < 0,08 e valores de CFI e TLI > 0,90, preferencialmente > 0,95 (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Em seguida, a invariância de medida de cada um dos fatores da EFC entre adultos e adolescentes foi estimada a partir da Análise Fatorial Confirmatória Multigrupo (AFCMG). Optou-se por realizar o teste de invariância fator a fator, considerando cada um deles como um construto unidimensional, justamente por cada um destes ter uma interpretabilidade singular e por possuírem evidências de validade que sustentem.

A análise foi realizada por meio do software estatístico R (R Core Team, 2022) e foi utilizado o método de estimação WLSMV (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2010). A invariância da escala foi avaliada em três modelos: Configural (estrutura fatorial), Métrico (cargas fatoriais) e Escalar (intercepto dos itens). A avaliação da invariância é realizada de forma hierárquica, ou seja, o modelo mais complexo só é avaliado se o seu antecedente for invariante (Peixoto & Martins, 2021).

Para avaliar a invariância no modelo Configural, são considerados os mesmos critérios de índices de ajuste da AFC. Já para avaliação da invariância, nos modelos Métrico e Escalar, é considerada a variabilidade dos índices CFI, RMSEA e SRMR, sendo que pioras de ΔCFI ≤ 0,01, ΔRMSEA ≥ 0,015 e ΔSRMR ≥ 0,01 entre um modelo e o seu antecedente indicam a sua não-invariância. O ΔCFI é indicado como índice mais robusto para avaliação da invariância entre grupos (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002), porém, ΔRMSEA e ΔSRMR podem ser utilizados como índices suplementares (Chen, 2007). Em seguida, conforme já exposto, a amostra foi separada em duas subamostras, uma de adultos e outra adolescentes. A partir disto, utilizando o mesmo procedimento supracitado, foi avaliada invariância entre sexo em ambas as etapas do desenvolvimento.

Resultados

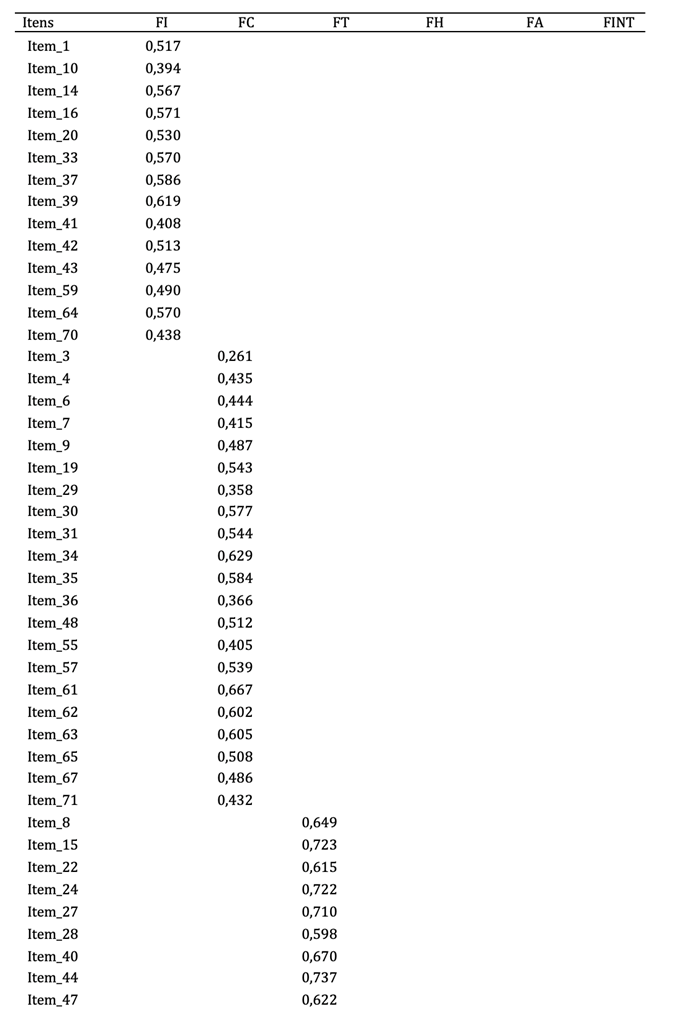

Os resultados da AFC realizada na EFC estão expostos na Tabela 2. Como é possível observar, apenas o item 3 não obteve carga fatorial satisfatória (≥ 0,30) em seu respectivo fator (FC). O item refere-se à força criatividade (Faço as coisas de jeitos diferentes).

Tabela 2: Resultado da AFC na Escala de Forças de Caráter

Nota: FI = Forças Interpessoais; FC = Forças de Coragem; FT = Forças Teologais; FH = Forças de Humanidade; FA = Forças de Autorregulação e FINT = Forças Intelectuais

Os índices de ajuste obtidos na AFC da EFC foram aceitáveis (χ² = 55127,615; gl = 2399; RMSEA = 0,076; SRMR = 0,071; TLI = 0,909; CFI = 0,912). Devido ao item 3 não apresentar carga fatorial satisfatória, foi realizada uma nova CFA excluindo-o, porém não foram encontradas mudanças significativas nos índices de ajuste (χ² = 601118,791; gl = 2415; RMSEA = 0,076 (90 % IC = 0,075-0,076); SRMR = 0,071; TLI = 0,910; CFI = 0,913). Desta forma, optou-se por manter o item 3 para as análises posteriores. A respeito da consistência interna dos fatores, todos obtiveram bons índices de confiabilidade: FI (α = 0,79; ω = 0,82); FC (α = 0,84; ω = 0,86); FT (α = 0,87; ω = 0,89); FH (α = 0,75; ω = 0,78); FA (α = 0,73; ω = 0,80); FINT (α = 0,80; ω = 0,85). Os menores alfas foram encontrados nos fatores FA e FH.

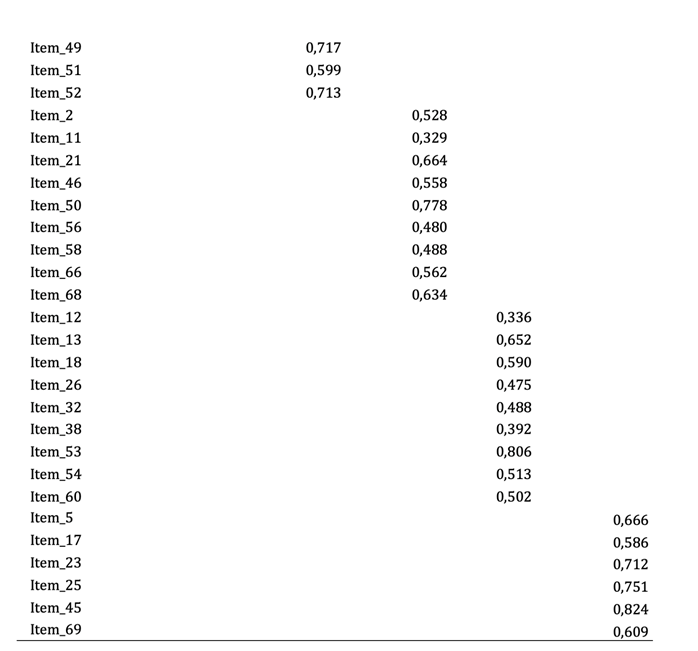

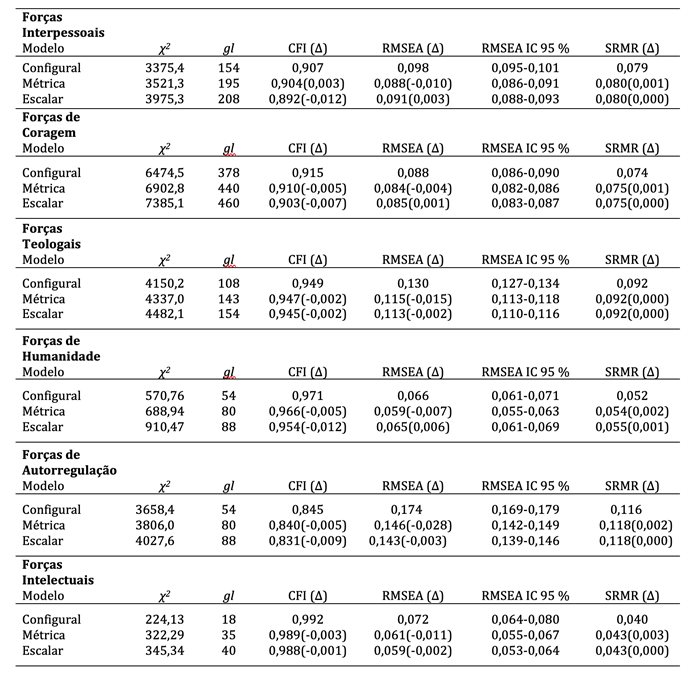

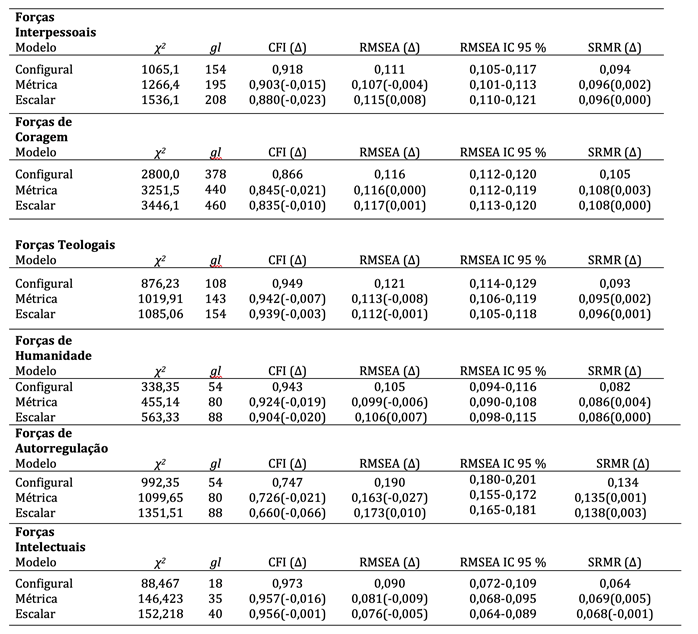

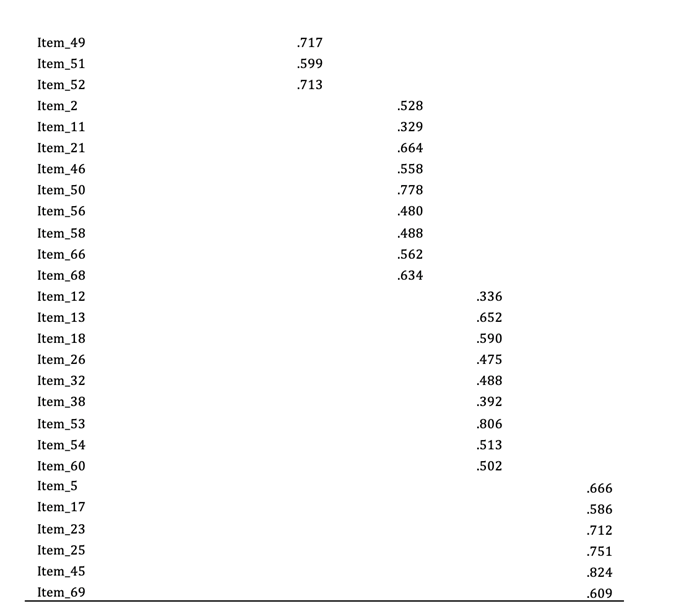

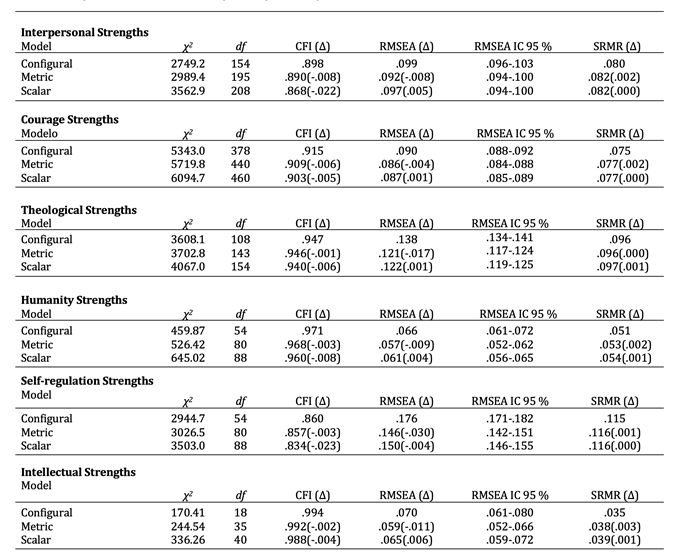

Com vistas a atender ao segundo objetivo deste estudo, os resultados obtidos na análise de invariância entre adolescentes e adultos estão expostos na Tabela 3. Conforme pode ser observado, os resultados indicam, a partir de todos os índices considerados, a invariância configural, métrica e escalar dos fatores FC, FT e FINT, ou seja, estes apresentaram equivalência forte entre os grupos, de modo que adolescentes e adultos respondem de modo similar aos itens destes fatores.

No caso dos fatores FI e FH, estes apresentaram invariância configural e métrica em todos os índices, porém para o modelo Escalar o ΔCFI obtido (-0,012) excedeu o critério proposto (-0,010), enquanto o ΔRMSEA e ΔSRMR foram adequados. Mesmo sendo o ΔCFI o índice considerado mais robusto para avaliação da invariância, este ultrapassou apenas em -0,002 o critério proposto, portanto, é possível considerar que ambos os índices suplementares indicaram a invariância do modelo métrico. Sob esta perspectiva, também se pode considerar estes fatores como tendo equivalência forte entre adolescentes e adultos. Por fim, em relação ao fator FA, este não apresentou índices de ajuste aceitáveis no modelo Configural. Portanto, não pode ser considerado equivalente entre as faixas etárias em nenhum dos modelos.

Tabela 3: Índices de ajuste dos modelos de invariância dos fatores da EFC testados entre adolescentes e adultos

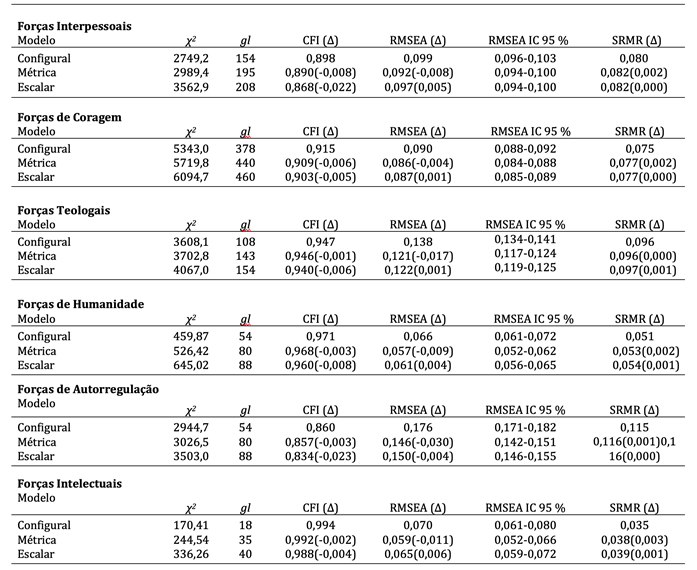

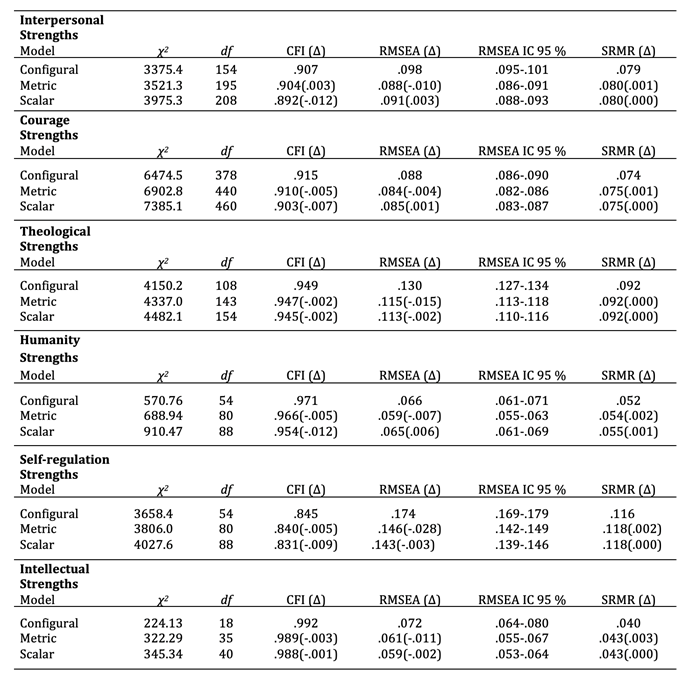

Os resultados obtidos na análise de invariância por sexo na subamostra de adolescentes estão expostos na Tabela 4. Conforme pode ser observado, apenas o fator FT apresentou invariância nos três modelos (Configural, Métrico e Escalar). Os fatores FI, FH e FINT apresentaram invariância configural. Já os fatores FC e FA não apresentaram invariância. Desta forma, pode-se afirmar que apenas o fator Forças Teologais apresenta invariância forte entre homens e mulheres adolescentes.

Tabela 4: Índices de ajuste dos modelos de invariância dos fatores da EFC testados entre sexos em adolescentes

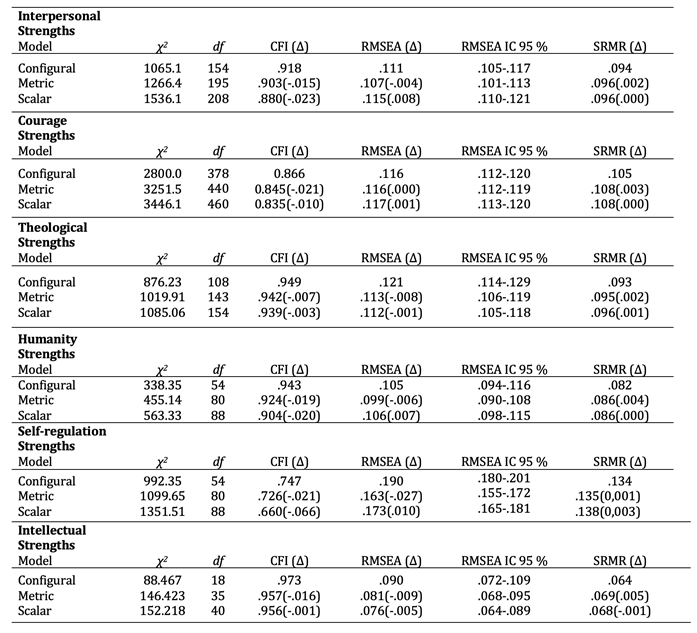

Os resultados da análise de invariância por sexo na subamostra de adultos estão expostos na Tabela 5. Conforme pode ser observado, os fatores FC, FT, FH e FINT, apresentaram invariância nos três modelos (Configural, Métrico e Escalar), ou seja, invariância forte entre os grupos. Em contraste, os fatores FI e FA não apresentaram invariância em quaisquer modelos.

Tabela 5: Índices de ajuste dos modelos de invariância dos fatores da EFC testados entre sexos em adultos

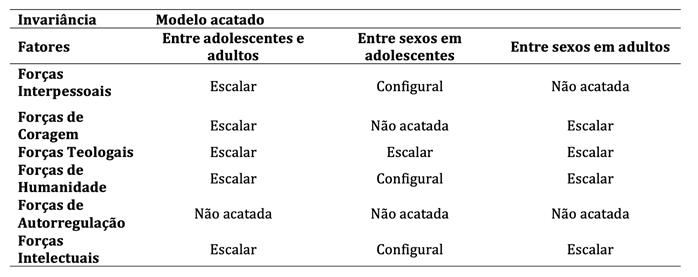

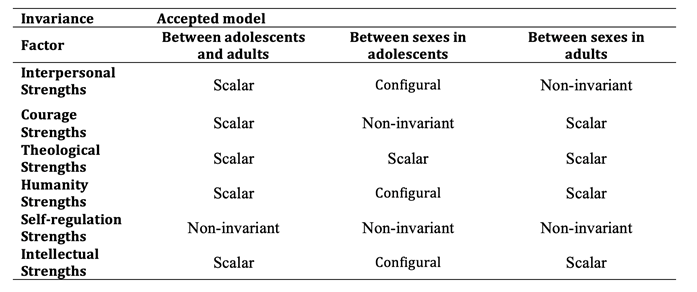

A Tabela 6 apresenta uma síntese dos resultados das análises de invariância dos seis fatores EFC. Nela estão expostos, separadamente, os modelos de invariância acatados para cada um dos fatores da escala nas três situações analisadas (entre adolescentes e adultos, entre sexos em adolescentes e entre sexos em adultos).

Tabela 6: Síntese dos resultados da análise de invariância dos fatores da Escala de Forças de Caráter

Discussão

O presente estudo objetivou replicar a estrutura interna da EFC proposta por Noronha e Batista (2020), visando buscar evidências de validade com base na estrutura interna. Embora o instrumento tenha outros estudos de análise da estrutura interna (Noronha & Batista, 2020; Noronha et al., 2015; Noronha & Zanon, 2018), tal como preconizado por AERA et al. (2014), novas evidências de validade devem ser pesquisadas com amostras distintas. No caso deste estudo, usou-se uma ampla amostra. Além disso, o estudo buscou avaliar se os fatores encontrados, quando considerados como escalas unidimensionais (devido à interpretabilidade de cada um deles e as reiteradas evidências de validade), se demonstravam invariantes entre adolescentes e adultos e entre os sexos destes grupos.

Em relação aos achados da análise da estrutura interna, os índices foram aceitáveis, replicando, portanto, o estudo de Noronha e Batista (2020). Os índices de ajuste ficaram dentro dos parâmetros mínimos sugeridos por Hu e Bentler (1999), sendo que todos os itens, exceto o 3, tiveram carga > 0,30 em seus respectivos fatores. Além disso, todos os fatores do instrumento apresentaram boa consistência interna (Cronbach, 1951). Tais resultados estão em concordância com outros estudos (Littman-Ovadia & Lavy, 2012; McGrath, 2014; Neto et al., 2014; Ng et al., 2016; Noronha & Batista, 2020; Noronha et al., 2015; Noronha & Zanon, 2018; Solano & Cosentino, 2018) que indicam uma distribuição das forças pessoais divergente do modelo teórico proposto por Peterson e Seligman (2004).

Tratando da análise de invariância do instrumento, primeiramente cabe ressaltar a importância deste tipo de procedimento antes de se realizar comparações entre os grupos. Conforme abordado, a literatura aponta divergências entre quais forças pessoais tem maiores e menores médias entre homens e mulheres e entre adolescentes e adultos (Heintz et al., 2019; Heintz & Ruch, 2022). Porém, as diferenças encontradas, podem não refletir diferenças reais nas forças entre os grupos e sim serem decorrentes de erros ou vieses de medida do instrumento. Instrumentos com medidas errôneas ou enviesadas, podem não apenas apontar para diferenças inexistentes, como podem também podem encobrir diferenças existentes entre os grupos. Justamente por ser capaz de trazer luz a esta questão, a avaliação da invariância do instrumento se faz extremamente relevante (Chen, 2008).

No presente estudo realizamos a análise de invariância nos modelos Configural, Métrico e Escalar. A título de compreensão, o modelo Configural avalia se a estrutura do instrumento, ou seja, sua configuração é adequada para ambos os grupos analisados. Quando a invariância não é acatada neste modelo, isto significa que os itens carregam em diferentes fatores para cada grupo. O modelo Métrico avalia se as cargas fatoriais dos itens são estatisticamente iguais para ambos os grupos. Quando este não é acatado, significa que os itens não têm a mesma importância para o instrumento em ambos os grupos, o que indica viés nas respostas aos itens por um dos grupos, portanto qualquer comparação de média estará enviesada. Por fim, o modelo Escalar avalia se o nível de traço latente para responder determinado item, é equivalente entre os grupos. Quando este não é acatado, significa que um dos grupos pode endossar mais facilmente um item do que o outro (Damásio, 2013; Milfont & Fischer, 2010).

Desta forma, conforme a descrição dos modelos, fica evidente que estudos comparativos entre sexos, diferentes faixas etárias e diferentes nacionalidades são capazes de refletir diferenças ou similaridades reais entre os grupos, se o instrumento utilizado for equivalente entre os grupos. Afinal, a invariância acatada no modelo Configural, diz respeito à configuração correta dos itens no modelo e a invariância no modelo métrico, somente indica que as cargas fatoriais são estatisticamente equivalentes, enquanto a invariância no modelo Escalar, indica que os itens realmente avaliam de maneira equivalente o traço latente dos sujeitos pertencentes a ambos os grupos. Portanto, apesar da relevância de cada modelo avaliado, comparações diretas entre os grupos e não enviesadas por erro de medida só são possíveis quando os três níveis de invariância são acatados (Fischer & Karl, 2019; Milfont & Fischer, 2010).

No presente estudo, a equivalência escalar da EFC foi acatada entre adolescentes e adultos nos fatores FI, FC, FT, FH e FINT, entre homens e mulheres adolescentes no fator FT e entre homens e mulheres adultos nos fatores FC, FT, FH e FINT. Conforme explicitado, estes resultados sugerem que comparações de média nas forças pessoais entre os grupos, são possíveis naquelas pertencentes a estes fatores supracitados (e.g. humor entre adolescentes e adultos; espiritualidade entre homens e mulheres adolescentes; sensatez entre homens e mulheres adultos). Desta forma, pode-se afirmar que comparações entre forças de caráter pertencentes aos fatores que não acataram invariância escalar entre os grupos avaliados, não são possíveis, pois não irão refletir diferenças ou similaridades reais, mas sim erros e vieses do instrumento de medida (Damásio, 2013; Fischer & Karl, 2019; Peixoto & Martins, 2021).

É relevante destacar que o fator FA não obteve sequer invariância configural em nenhum dos pares de grupos testados. Ao investigar cuidadosamente os resultados do modelo, foi observado que alguns funcionaram de forma diferente entre os grupos. No caso da comparação entre adolescentes e adultos o item 60 (“Sou uma pessoa cuidadosa”) obteve carga fatorial < 0,30 para ambos. Já os itens 18 (“Sempre tenho muita energia”) e 53 (“Eu me sinto cheio(a) de vida”) obtiveram cargas maiores para os adultos do que para os adolescentes; isso pode indicar que, talvez, para alguns adolescentes estes itens não estejam diretamente relacionados aos demais itens de autorregulação e sim a outras características de sua personalidade. No caso da comparação entre os sexos em adolescentes, os itens 18, 60 e 38 (“Mantenho a calma mesmo em situações difíceis”) carregaram adequadamente no fator apenas para o grupo do sexo feminino. Estudos anteriores demonstraram que meninas adolescentes costumam pontuar mais alto autorregulação do que meninos (Coyne et al., 2015; Sanchis-Sanchis et al., 2020; Tetering et al., 2020), portanto, é possível que a não invariância configural entre os grupos decorra desta diferença. Já para a comparação entre os sexos em adultos, o item 60 teve carga fatorial muito baixa para o grupo do sexo masculino (0,167) e o item 38 teve carga mais alta para mulheres do que para homens. Ambos os itens envolvem questões relacionadas a calma/cuidado e, como aponta a literatura, mulheres tendem a relatar mais estratégias de autorregulação do que homens (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012), o que pode justificar a ausência de invariância deste fator entre os grupos.

O fator FC também não foi invariante sequer no nível configural entre os grupos de adolescentes. Uma observação das cargas fatoriais indicou que os itens 3 (“Faço as coisas de jeitos diferentes”), 6 (“Faço bons julgamentos, mesmo em situações difíceis”), 7 (“Penso em diferentes possibilidades quando tomo uma decisão”), 29 (“Penso muito antes de tomar uma decisão”) e 36 (“Analiso o que as pessoas dizem antes de dar minha opinião”) obtiveram carga < 0,30 para o grupo de adolescentes do sexo masculino. Diferentemente de itens como o 35 (“Enfrento perigos para fazer o bem”) que refletem mais diretamente uma coragem com teor positivo, o conteúdo destes itens envolve algo mais próximo de pensar/refletir antes de agir. Desta forma, é possível que para o grupo de adolescentes do sexo masculino estes itens estejam captando outro tipo de conteúdo como, por exemplo, controle de impulsividade (Weinstein & Dannon, 2015).

Por fim, o fator FI não apresentou invariância configural entre os sexos para adultos. O item 10 (“Não minto para agradar as pessoas”) obteve carga fatorial < 0,30 para homens (0,222), mas também não obteve uma carga muito elevada para mulheres (0,317). Por ser um item positivo (no sentido do traço latente), mas que contém a palavra “não” a interpretação do significado da sentença pelos participantes pode ter sido dificultada o que pode ter penalizado o ajuste do modelo Configural e resultado na não invariância do fator. Porém, o item 33 (“Sou uma pessoa verdadeira”) também apresentou maior carga para as mulheres do que para os homens, o que pode indicar que, de fato, pode haver uma diferença no funcionamento do conteúdo dos itens entre os sexos em adultos para além da questão apontada para o item 10.

Considerações finais

A estrutura encontrada por Noronha e Batista (2020) para a EFC foi replicada no presente estudo. Isto traz um novo indicativo de que esta forma de distribuição das forças pessoais tem sustentação empírica. Apesar de o item 3 não causar grande prejuízo ao ajuste do modelo, talvez sua reformulação pudesse ser considerada, devido à baixa carga fatorial. Em especial, o item refere-se à criatividade (“Faço as coisas de jeitos diferentes”) e é possível que o significado de fazer coisas diferentes tenha variadas interpretações, o que pode ter impactado nos resultados. É ímpar que novos estudos sejam conduzidos, dentre os quais, aplicações adicionais de estudos pilotos.

A respeito da invariância dos fatores, os resultados indicaram apenas o fator FT como tendo invariância escalar em todos as comparações de grupos, porém, ao menos em uma das comparações de grupo, os outros fatores demonstraram invariância completa, exceto o fator FA, que foi não-invariante em todas as comparações de grupo. Isto pode ser um indicativo para a revisão prioritária dos itens que o compõem. O fator FC e o fator FI também merecem atenção em uma futura revisão do instrumento, já que o primeiro não funcionou de forma equivalente em nenhum nível entre os agrupamentos por sexo em adolescentes e ocorreu o mesmo com o segundo em adultos.

Como limitação do presente estudo, pode-se indicar que devido ao número de itens dispostos para cada força de caráter ser menor que quatro, não foi possível avaliar a invariância destas, uma a uma, a partir da AFCMG (Czerwiński & Atroszko, 2023). Recomenda-se que futuros estudos utilizem métodos capazes de avaliar a invariância de cada uma das forças isoladamente.

Referencias

American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, & National Council on Measurement in Education. (2014). Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing: National Council on Measurement in Education. American Educational Research Association.

Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2010). Simple Second Order Chi-Square Correction. https://www.statmodel.com/download/WLSMV_new_chi21.pdf

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of Goodness of Fit Indexes to Lack of Measurement Invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464-504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834

Chen, F. F. (2008). What happens if we compare chopsticks with forks? The impact of making inappropriate comparisons in cross-cultural research. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(5), 1005. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013193

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating Goodness-of-Fit Indexes for Testing Measurement Invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(2), 233-255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

Coyne, M. A., Vaske, J. C., Boisvert, D. L., & Wright, J. P. (2015). Sex differences in the stability of self-regulation across childhood. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, 1(1), 4-20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-015-0001-6

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16, 297-334. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310555

Czerwiński, S. K., & Atroszko, P. A. (2023). A solution for factorial validity testing of three-item scales: An example of tau-equivalent strict measurement invariance of three-item loneliness scale. Current Psychology, 42(2), 1652-1664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01554-5

Damásio, B. F. (2013). Contribuições da Análise Fatorial Confirmatória Multigrupo (AFCMG) na avaliação de invariância de instrumentos psicométricos. Psico-Usf, 18, 211-220. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-82712013000200005

Fischer, R., & Karl, J. A. (2019). A Primer to (Cross-Cultural) Multi-Group Invariance Testing Possibilities in R. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1507. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01507

Heintz, S., Kramm, C., & Ruch, W. (2019). A meta-analysis of gender differences in character strengths and age, nation, and measure as moderators. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 14(1), 103-112. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2017.1414297

Heintz, S., & Ruch, W. (2022). Cross-sectional age differences in 24 character strengths: Five meta-analyses from early adolescence to late adulthood. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 17(3), 356-374. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2021.1871938

Hu, L. T., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Littman-Ovadia, H., & Lavy, S. (2012). Character strengths in Israel Hebrew adaptation of the VIA Inventory of Strengths. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 28(1), 41-50. https://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a00008

McGrath, R. E. (2014). Measurement Invariance in Translations of the VIA Inventory of Strengths. European Journal of Psychological Assessment, 32(3), 187-194. http://doi.org/10.1027/1015-5759/a000248

Milfont, T. L., & Fischer, R. (2010). Testing measurement invariance across groups: Applications in cross-cultural research. International Journal of Psychological Research, 3(1), 111-130. https://doi.org/10.21500/20112084.857

Neto, J., Neto, F., & Furnham, A. (2014). Gender and Psychological Correlates of Self-rated Strengths Among Youth. Social Indicators Research, 118(1), 315-327. http://doi.org/10.1007/s11205-013-0417-5

Ng, V., Cao, M., Marsh, H. W., Tay, L., & Seligman, M. E. P. (2016). The factor structure of the Values in Action Inventory of Strengths (VIA-IS): An item-level Exploratory Structural Equation Modeling (ESEM) bifactor analysis. Psychological Assessment, 29(8). http://doi.org/10.1037/pas0000396

Nolen-Hoeksema, S. (2012). Emotion regulation and psychopathology: The role of gender. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 8(1), 161-187. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032511-143109

Noronha, A. P. P., & Batista, H. H. V. (2017). Escala de Forças e Estilos Parentais: Estudo correlacional. Estudos Interdisciplinares em Psicologia, 8(2), 2-19. https://doi.org/10.5433/2236- 6407.2017v8n2p02

Noronha, A. P. P., & Batista, H. H. V. (2020). Análise da estrutura interna da Escala de Forças de Caráter. Ciencias Psicológicas, 14(1), e-2150. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v14i1.2150

Noronha, A. P. P., & Campos, R. R. F. (2018). Relationship between character strengths and personality traits. Estudos de Psicologia, 35(1), 29-37. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982- 02752018000100004

Noronha, A. P. P., Dellazzana-Zanon, L. L., & Zanon, C. (2015). Internal structure of the Characters Strengths Scale in Brazil. Psico-USF, 20(2), 229-235. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-82712015200204

Noronha, A. P. P., & Reppold, C. T. (2019). Introdução às forças de caráter. Em M. N. Baptista (Ed.), Compêndio de Avaliação Psicológica, (pp. 549-568). Vozes.

Noronha, A. P. P., & Reppold, C. T. (2021). As fortalezas dos indivíduos: o que são forças de caráter? Em M. Rodrigues, & D. da S. Pereira (Eds.), Psicologia Positiva: dos conceitos à aplicação, (Vol. 1, pp. 68–81). Sinopsys.

Noronha, A. P. P., & Zanon, C. (2018). Strenghts of character of personal growth: Structure and relations with the big five in the Brazilian context. Paidéia (ribeirão Preto), 28, e2822 https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-4327e2822

Park, N. (2009). Character Strength. Em S. J. Lopez (Ed.), The encyclopedia of positive psychology, (pp. 135-141). Blackwell.

Peixoto, E. M., & Martins, G. H. (2021). Contribuições da análise fatorial confirmatória para a validade de instrumentos psicológicos. Em C. Faiad, Baptista. M. B., & Primi, R., Tutoriais em análise de dados aplicados à psicometria (pp. 143-160). Vozes.

Peterson, C., & Seligman, M. E. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification (Vol. 1). Oxford University Press.

R Core Team. (2022). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Reppold, C., D’Azevedo, L., & Noronha, A. P. P. (2021). Estratégias de avaliação de forças de caráter. Psicologia, Saúde & Doenças, 22(1), 50-61. https://doi.org/10.15309/21psd220106

Rosseel, Y. (2012). lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling. Journal of Statistical Software, 48(2). https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i02

Seibel, B. L., DeSousa, D., & Koller, S. H. (2015). Adaptação brasileira e estrutura fatorial da escala 240-item VIA Inventory of Strengths. Psico-USF, 20, 371-383. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-82712015200301

Sanchis-Sanchis, A., Grau, M. D., Moliner, A.-R., & Morales-Murillo, C. P. (2020). Effects of age and gender in emotion regulation of children and adolescents. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 946. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2020.00946

Solano, A. C., & Cosentino, A. C. (2018). IVyF abreviado —IVyFabre—: análisis psicométrico y de estructura factorial en Argentina. Avances en Psicología Latinoamericana/Bogotá (Colombia), 36(3), 619-637. https://doi.org/10.12804/revistas.urosario.edu.co/apl/a.4681

Tetering, M. A. J. van, Laan, A. M. van der, Kogel, C. H. de, Groot, R. H. M. de, & Jolles, J. (2020). Sex differences in self-regulation in early, middle and late adolescence: A large-scale cross-sectional study. PLOS ONE, 15(1), e0227607. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0227607

Weinstein, A., & Dannon, P. (2015). Is impulsivity a male trait rather than female trait? Exploring the sex difference in impulsivity. Current Behavioral Neuroscience Reports, 2(1), 9–14. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40473-015-0031-8

Disponibilidade de dados: O conjunto de dados que embasa os resultados deste estudo não está disponível.

Como citar: Rocha, R. M. A. da, Santos, C. G., Gonzalez, H. V., & Noronha, A. P. P. (2024). Escala de Forças de Caráter: novas evidências de validade. Ciencias Psicológicas, 18(1), e-3297. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v18i1.3297

Contribuição de

autores (Taxonomia CRediT): 1. Conceitualização;

2. Curadoria de dados; 3. Análise formal; 4. Aquisição de financiamento;

5. Pesquisa; 6. Metodologia; 7. Administração do projeto; 8. Recursos; 9.

Software; 10. Supervisão; 11. Validação; 12. Visualização; 13. Redação: esboço

original; 14. Redação: revisão e edição.

R. M. A. D. R contribuiu em 1, 2, 3, 6, 12, 13; C. G. S. em 1, 6, 12, 13;

H. V. G. em 1, 6, 12, 13; A. P. P. N. em 1, 6, 7, 10, 12, 13, 14.

Editora científica responsável: Dra. Cecilia Cracco.

10.22235/cp.v18i1.3297

Original Articles

Character Strengths Scale: new validity evidence

Escala de Forças de Caráter: novas evidências de validade

Escala de Fortalezas del Carácter: nuevas evidencias de validez

Rafael Moreton Alves da Rocha1, ORCID 0000-0003-2291-2986

Camila Grillo Santos2, ORCID 0000-0002-2123-9083

Henrique Vazquez Gonzalez3, ORCID 0000-0002-6109-4894

Ana Paula Porto Noronha4, ORCID 0000-0001-6821-0299

1 Programa de Pós-Graduação Stricto Sensu em Psicologia, Universidade São Francisco, Brazil, [email protected]

2 Programa de Pós-Graduação Stricto Sensu em Psicologia, Universidade São Francisco, Brazil

3 Programa de Pós-Graduação Stricto Sensu em Psicologia, Universidade São Francisco, Brazil

4 Programa de Pós-Graduação Stricto Sensu em Psicologia, Universidade São Francisco, Brazil

Abstract:

The aim of the study was to identify instruments used to assess the

Character strengths are considered a positive aspect of personality, indicating

a satisfying and authentic life. The Character Strengths Scale is the only known

measure that evaluates personal strengths of Brazilians. The literature

suggests that the proposed structure of 24 character strengths divided into six

virtues is not empirically replicated. Studies have compared character

strengths between men and women and across stages of development; however,

understanding the equivalence of the instrument across groups should precede

such comparisons. This study aims to test the factor structure of the Character

Strengths Scale found by Noronha and Batista (2020) and evaluate the

construct’s invariance among adolescents and adults, as well as between sexes

in adolescents and adults. For the first objective, Confirmatory Factor

Analysis (CFA) was employed, which supported the tested structure. For the

second, the equivalence of the scale factors between groups was evaluated using

Multi-Group CFA, which identified some factors as equivalent and others as not.

It can be concluded that the tested factor structure is empirically relevant

and that, when comparing strength means between groups in future studies using

the Character Strengths Scale, authors should pay attention to which strengths

belong to invariant factors.

Keywords: psychological assessment; psychometrics; positive psychology;

personality.

Resumo:

As forças pessoais são consideradas como

construto da personalidade com aspecto positivo, indicando uma vida

satisfatória e autêntica. A Escala de Forças de Caráter (EFC) é a única que se

tem conhecimento que avalia as forças pessoais dos brasileiros. A literatura aponta

que a estrutura proposta, das 24 forças pessoais divididas em 6 virtudes, não é

replicada empiricamente. Estudos tem comparado as forças de caráter entre

homens e mulheres e entre etapas do desenvolvimento, porém, compreender a

equivalência do instrumento entre os grupos deve preceder tais comparações.

Este estudo objetiva testar a estrutura fatorial da EFC encontrada por Noronha

e Batista (2020) e avaliar a invariância do construto entre: adolescentes e

adultos, sexo em adolescentes, sexo em adultos. Para o primeiro objetivo,

empregou-se uma Análise Fatorial Confirmatória (AFC), que corroborou a

estrutura testada. Para o segundo, avaliou-se a invariância dos fatores da

escala entre os grupos a partir da AFC-Multigrupo, que apontou alguns fatores

como equivalentes e outros não. Pode-se concluir que a estrutura fatorial

testada é empiricamente pertinente e que, ao comparar médias das forças entre

os grupos em estudos futuros com a EFC, os autores devem se atentar a quais

forças pertencem a fatores invariantes.

Palavras-chave: avaliação

psicológica; psicometria; psicologia positiva; personalidade.

Resumen:

Las fortalezas del carácter se consideran

un aspecto positivo de la personalidad que indica una vida satisfactoria y

auténtica. La Escala de Fortalezas del Carácter (EFC) es la única medida

conocida que evalúa las fortalezas personales de los brasileños. La literatura

sugiere que la estructura propuesta de 24 fortalezas divididas en seis virtudes

no se replica empíricamente. Los estudios han comparado las fortalezas del

carácter entre hombres y mujeres, y en diferentes etapas del desarrollo; sin

embargo, comprender la equivalencia del instrumento entre grupos debe preceder

a tales comparaciones. Este estudio tiene como objetivo probar la estructura

factorial de la EFC encontrada por Noronha y Batista (2020) y evaluar la

invarianza del constructo entre: adolescentes y adultos, sexo en adolescentes,

sexo en adultos. Para el primer objetivo, se utilizó el Análisis Factorial

Confirmatorio (CFA) que respaldó la estructura probada. Para el segundo, se

evaluó la equivalencia de los factores de la escala entre grupos utilizando el

CFA Multigrupo, que identificó algunos factores como equivalentes y otros no.

Se puede concluir que la estructura factorial probada es empíricamente

relevante y que, al comparar las medias de las fortalezas entre grupos en

futuros estudios utilizando la EFC, los autores deben prestar atención a qué

fortalezas pertenecen a factores invariantes.

Palabras clave: evaluación

psicológica; psicometría; psicología positiva; personalidad.

Received: 21/03/2023

Accepted: 06/03/2024

The construct of character strengths has been discussed by Positive Psychology since the 1990s, when a group of researchers organized an initial list of strengths, which formed the basis for a more comprehensive conceptualization of individuals’ positive traits (Noronha & Reppold, 2019; Park, 2009). The researchers employed various resources to obtain the initial list, initially utilizing the retrieval of existing scientific production. Authors Peterson and Seligman (2004), after participating in several conferences and seminars and studying traditions, documents, religious books, and philosophical works, published a comprehensive, internationally recognized material that included 24-character strengths theoretically grouped into six virtues. The book was titled Manual of Sanities, in criticism of the emphasis placed until that moment on the investigation of human pathologies rather than flourishing.

In this way, character strengths can be understood as fundamental positive attributes —positive personality traits— for individuals to lead a fulfilling and happy life (Noronha & Reppold, 2019). Park (2009) further complements this definition by stating them as unique traits that can be expressed through thoughts, actions, and feelings. Recently, Noronha and Reppold (2021) suggested that the most appropriate translation of “character strengths” into Portuguese would be forças pessoais (personal strengths). For this reason, from this moment on, we will use this terminology.

Personal strengths correspond to the healthy aspects of individuals’ personalities, and it is crucial to utilize this psychological construct in practice. They are stable in individuals but susceptible to being intensified and need to be analyzed according to the person’s development and the context in which they are embedded (Reppold et al., 2021). There are intervention research studies related to personal strengths with satisfactory results. In the clinical area, they promote increased self-esteem, happiness, and self-efficacy; in the hospital setting, there has been an improvement in quality of life and treatment adherence; in the school context, personal strengths help improve academic performance and reduce instances of bullying, as well as occurrences of symptoms associated with depressed mood and anxiety; in the family setting, they contribute to understanding family relationships and deepening awareness of the dynamics among its members (Noronha & Reppold, 2019; Reppold et al., 2021). For effective intervention in various contexts with personal strengths, it is necessary to have an instrument with theoretical quality, technical robustness, and scientific validity.

With the publication of the classification of personal strengths, research has been conducted aiming to advance theoretical understandings and empirical evidence of the construct. Consequently, instruments accessing personal strengths were constructed, with the most commonly found in international literature being the Values in Action (VIA; Peterson & Seligman, 2004). The VIA enabled research to be developed in many countries such as South Africa, Croatia, Israel, India, Germany, among others (Noronha et al., 2015). In the Brazilian context, based on the VIA, the Character Strengths Scale (Escala de Forças de Caráter – EFC, in Portuguese) was developed by Noronha and Barbosa (2016). It consists of 71 items that assess the 24 strengths, with the scale containing 3 items for each of them, except for Appreciation of Beauty, which has only 2 items. It is worth noting that the EFC is not an adaptation of the VIA, it’s just used it as a reference.

The EFC is the only scale known to assess personal strengths among Brazilians. There is a Portuguese version of the VIA-IS; however, validity studies conducted by Seibel et al. (2015) identified some weaknesses. In this study, the authors analyzed the factorial structure of the Brazilian Portuguese version of the VIA-IS. Firstly, they used parallel analysis as a method for factor retention, which indicated a solution of three or four factors. Then, they conducted Exploratory Factor Analysis for both possibilities, grouping the items corresponding to each personal strength. However, in both the three-factor and four-factor solutions, several of the personal strengths showed cross-loadings (loadings above .30 on more than one factor). The authors then chose to consider the solution proposed by the Hull method, which, unlike parallel analysis, suggested a unifactorial solution for the VIA-IS, arguing that the strengths would all be interconnected and, therefore, should not be divided into virtues. None of the solutions found support the division of strengths into six virtues, as originally proposed by Peterson and Seligman (2004). In fact, the findings indicate psychometric weaknesses in the results, especially regarding the multifactorial solutions for the scale (Seibel et al., 2015).

Regarding the EFC, several investigations have been conducted to search for validity evidence. Regarding evidence based on internal structure, for example, the authors published three studies, with results differing from one another. The first study, after not finding the theoretical structure of six virtues, proposed a unidimensional interpretation for the EFC (Noronha et al., 2015). The study was conducted with second-order factors, guided by the 24 personal strengths. However, with the advancement of research, it became clear that interpreting a general score of personal strengths had little or no utility. Therefore, the authors tested different structures in two other separate articles. Noronha and Zanon (2018), in a study with a sample of 981 university students, pointed to a three-factor solution for the EFC (Intellect, Intrapersonal, and Collectivism and Transcendence). The authors argued that, despite finding better fit indices in structures tested with a greater number of dimensions, the three-factor solution was the only one that made sense and was theoretically sustainable.

Subsequently, Noronha and Batista (2020), in a study with a sample of 1,500 university students, identified, through Exploratory Factor Analysis, a 6-factor solution for the instrument. However, Peterson and Seligman’s (2004) theoretical classification was not replicated (see Table 1). In this study, several items obtained cross-factor loadings, so the authors proposed allocating them to their respective factors not only based on factor loading but also guided by theoretical aspects. The items were distributed among the following proposed factors: Interpersonal Strengths (IS); Courage Strengths (CS); Theological Strengths (TS); Humanity Strengths (HS); Self-Regulation Strengths (SRS); and Intellectual Strengths (ITS).

Table 1: Distribution of personal strengths proposed by Peterson and Seligman (2004) and distribution found by Noronha and Batista (2020)

Studies were also conducted to search for evidence of validity with external variables related constructs such as personality, parenting styles, and social support. The personality factors of Extroversion and Socialization were more explanatory of personal strengths. Regarding parenting styles, strengths were more strongly associated with responsiveness, which interprets affection, involves sensitivity, acceptance, and commitment (Noronha & Batista, 2017, 2020; Noronha & Campos, 2018; Noronha & Reppold, 2019).

A recent theme concerning personal strengths revolves around differences in endorsement among different groups (e.g., men and women; adolescents and adults). Recent meta-analyses indicate that study findings are divergent regarding which strengths would be predominant among the mentioned groups (Heintz et al., 2019; Heintz & Ruch, 2022). However, before analyzing potential differences, it's necessary to investigate whether the instrument used to assess personal strengths measures the same construct across groups. In other words, if the instrument is invariant among them (Damásio, 2013).

Invariance analysis can be performed using three models, namely, (1) Configural, which indicates whether the number of factors and the number of items per factor are suitable for both groups; (2) Metric, which indicates the equivalence of item factor loadings between groups; (3) Scalar, which indicates that intercepts (the level of latent trait needed to endorse item categories) are equivalent across groups. Thus, if invariance is not accepted, for example, when comparing the means of men and women in the construct, the researcher may find a difference between sexes explained by measurement error rather than a genuine difference in the construct between them (Fischer & Karl, 2019; Peixoto & Martins, 2021).

Thus, the present study has the following objectives: (1) to test the factor structure of the EFC in the 6-factor model found by Noronha and Batista (2020) using CFA, seeking evidence of validity based on the internal structure of the construct (AERA et al., 2014); (2) to test the invariance of the EFC between adolescents and adults; (3) to test the invariance of the EFC between male and female adolescents; (4) to test the invariance of the EFC between men and women.

Method

Participants

The sample of this study consisted of 4,522 participants, aged between 13 and 65 years (M = 22.12; SD = 7.623), with 62.7 % reporting being female. Subsequently, for the invariance analysis of the scale between adult and adolescent genders, the sample was divided into two subsamples. The adult subsample consisted of 3,549 individuals, aged 18 to 65 years (M = 23.86; SD = 7.723), with 62.4 % reporting being female. The adolescent subsample consisted of 973 individuals, aged 13 to 17 years (M = 15.76; SD = 1.008), with 63.8 % reporting being female.

Instruments

Sociodemographic questionnaire. This questionnaire was developed for the current study aiming to collect information about the sex and age of the participants.

Character Strengths Scale (EFC; Noronha & Barbosa, 2016). The scale consists of 71 statements responded to on a five-point Likert scale (0 = not at all like me; 4 = very much like me). The instrument was developed to assess 24 personal strengths, organized into six virtues, according to Peterson and Seligman’s definition (2004). Each strength is represented by three items, except for the Appreciation of Beauty strength, which has only two. The result is calculated by summing the values of the responded items. The 6-factor model proposed by Noronha and Batista (2020) has good internal consistency indices: IS (α = .89); CS (α = .88); TS (α = .93); HS (α = .91); SRS (α = .83), and ITS (α = .88).

Procedures

The project was submitted to the Research Ethics Committee. After approval (No. 365.343), data collection was conducted in person (using pen and paper). The applications always took place on the premises of educational institutions, with minors being surveyed in schools and adults in universities. Participants over 18 years old signed the Informed Consent Form (ICF). For data collection in schools, after obtaining authorization from the principals, a schedule was established. Initially, the research objectives were explained, and the ICF was provided to parents. After receiving signed ICFs, collection times were scheduled. The applications took place during school hours, after obtaining the signed Informed Assent Form (IAF). For all participants, the questionnaires were presented in the following order: sociodemographic questionnaire and Character Strengths Scale. It was estimated that the form could be completed in approximately 20 minutes.

Data analysis

To evaluate the factorial structure of the scale, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) was conducted using R software (R Core Team, 2022), through the Lavaan package (Rosseel, 2012), with the weighted least square mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimation method (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2010). Model fit was assessed using the following indices: χ², degrees of freedom (df), Root Mean Squared Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Standardized Root Mean Residual (SRMR), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI). These indices are considered adequate when RMSEA and SRMR values are < .08 and CFI and TLI values are > .90, preferably > .95 (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Next, the measurement invariance of each of the factors of the EFC between adults and adolescents was estimated using Multi-Group Confirmatory Factor Analysis (MG-CFA). We chose to perform the factor-by-factor invariance test, considering each factor as a unidimensional construct, precisely because each of them has a unique interpretability and has evidence of validity to support it.

The analysis was conducted using the statistical software R (R Core Team, 2022), and the weighted least square mean and variance adjusted (WLSMV) estimation method was employed (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2010). Scale invariance was evaluated in three models: configural (factorial structure), metric (factor loadings), and scalar (item intercepts). The assessment of invariance is conducted hierarchically, meaning that the more complex model is only evaluated if its predecessor is invariant (Peixoto & Martins, 2021).

To assess configural invariance, the same fit indices criteria from the CFA are considered. However, for metric and scalar invariance evaluation, the variability of CFI, RMSEA, and SRMR indices is considered. Worsening of ΔCFI ≤ 0.01, ΔRMSEA ≥ 0.015, and ΔSRMR ≥ 0.01 between a model and its predecessor indicate non-invariance. ΔCFI is considered the most robust index for assessing group invariance (Cheung & Rensvold, 2002); however, ΔRMSEA and ΔSRMR can be used as supplementary indices (Chen, 2007). Then, as previously mentioned, the sample was divided into two subsamples, one comprising adults and the other adolescents. Subsequently, using the same aforementioned procedure, invariance between sexes in both developmental stages was assessed.

Results

The results of the CFA conducted on the EFC are presented in Table 2. As it is possible to observe, only item 3 did not obtain a satisfactory factor loading (≥ .30) on its respective factor (FC). The item relates to the strength of creativity (I do things in different ways).

Table 2: CFA results for the Character Strengths Scale

Note.

IS = Interpersonal Strengths; CS = Courage Strengths;

TS = Theological Strengths; HS = Humanity Strengths;

SRS = Self-Regulation Strengths; ITS = Intellectual

Strengths

Note.

IS = Interpersonal Strengths; CS = Courage Strengths;

TS = Theological Strengths; HS = Humanity Strengths;

SRS = Self-Regulation Strengths; ITS = Intellectual

Strengths

The fit indices obtained in the CFA of the EFC were acceptable (χ² = 55127.615; df = 2399; RMSEA = .076; SRMR = .071; TLI = .909; CFI = .912). Due to item 3 not exhibiting a satisfactory factor loading, a new CFA excluding it was conducted, but no significant changes were found in the fit indices (χ² = 601118.791; df = 2415; RMSEA = .076 (90 % CI = .075-.076); SRMR = .071; TLI = .910; CFI = .913). Therefore, it was decided to retain item 3 for subsequent analyses. Regarding the internal consistency of the factors, all obtained good reliability indices: IS (α = .79; ω = .82); CS (α = .84; ω = .86); TS (α = .87; ω = .89); HS (α = .75; ω = .78); SRS (α = .73; ω = .80); ITS (α = .80; ω = .85). The lower alphas were found in the SRS and HS factors.

In order to address the second objective of this study, the results obtained from the invariance analysis between adolescents and adults are presented in Table 3. As can be observed, the results indicate, based on all considered indices, the configural, metric, and scalar invariance of the CS, TS, and ITS factors. This means that these factors showed strong equivalence between the groups, indicating that adolescents and adults respond similarly to the items of these factors.

In the case of the IS and HS factors, they exhibited configural and metric invariance across all indices. However, for the scalar model, the obtained ΔCFI (-.012) exceeded the proposed criterion (-.010), while the ΔRMSEA and ΔSRMR were acceptable. Although ΔCFI is considered the most robust index for assessing invariance, it exceeded the proposed criterion by only -.002. Therefore, it is possible to consider that both supplementary indices indicated the metric level of invariance. From this perspective, these factors can also be considered to have strong equivalence between adolescents and adults. Lastly, regarding the SRS factor, it did not exhibit acceptable fit indices in the configural model. Therefore, it cannot be considered equivalent across age groups in any of the models.

Table 3: Fit indices of the invariance models for the factors of the EFC tested between adolescents and adults

The results obtained from the sex invariance analysis in the adolescent subsample are presented in Table 4. As observed, only the TS factor exhibited invariance across all three models (Configural, Metric, and Scalar). The IS, HS, and ITS factors showed configural invariance. However, the CS and SRS factors did not exhibit invariance. Thus, it can be concluded that only the Theological Strengths factor demonstrates strong invariance between male and female adolescents.

Table 4: Fit indices of the invariance models for the factors of the EFC tested between sexes in adolescents

The results of the sex invariance analysis in the adult subsample are presented in Table 5. As observed, the CS, TS, HS, and ITS factors exhibited invariance across all three models (Configural, Metric, and Scalar), indicating strong invariance between the groups. In contrast, the IS and SRS factors did not exhibit invariance in any of the models.

Table 5: Fit indices of the invariance models for the factors of the EFC tested between sexes in adults

Table 6 presents a synthesis of the results of the invariance analyses of the six EFC factors. It displays, separately, the accepted invariance models for each of the scale factors in the three analyzed situations (between adolescents and adults, between sexes in adolescents, and between sexes in adults).

Table 6: Summary of the results of the invariance analysis of the factors of the Character Strengths Scale

Discussion

The present study aimed to replicate the internal structure of the Character Strengths Scale proposed by Noronha and Batista (2020), seeking validity evidence based on internal structure. Although the instrument has undergone other studies of internal structure analysis (Noronha & Batista, 2020; Noronha et al., 2015; Noronha & Zanon, 2018), as advocated by AERA et al. (2014), new validity evidence should be sought with distinct samples. In this study, a broad sample was used. Additionally, the study sought to assess whether the factors found, when considered as unidimensional scales (due to the interpretability of each of them and the repeated validity evidence), demonstrated invariance between adolescents and adults and between the sexes within these groups.

Regarding the findings of the internal structure analysis, the indices were acceptable, thus replicating the study by Noronha and Batista (2020). The fit indices remained within the minimum parameters suggested by Hu and Bentler (1999), with all items except item 3 having factor loadings > .30 on their respective factors. Additionally, all factors of the instrument demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach, 1951). These results are consistent with other studies (Littman-Ovadia & Lavy, 2012; McGrath, 2014; Neto et al., 2014; Ng et al., 2016; Noronha & Batista, 2020; Noronha et al., 2015; Noronha & Zanon, 2018; Solano & Cosentino, 2018) indicating a distribution of personal strengths diverging from the theoretical model proposed by Peterson and Seligman (2004).

In discussing the instrument’s invariance analysis, it’s essential to highlight the importance of this type of procedure before making comparisons between groups. As discussed, the literature indicates discrepancies in which personal strengths have higher and lower means between men and women and between adolescents and adults (Heintz et al., 2019; Heintz & Ruch, 2022). However, the differences found may not reflect real differences in strengths between groups but may instead be due to errors or biases in the instrument’s measurement. Instruments with erroneous or biased measurements may not only point to non-existent differences but may also obscure existing differences between groups. precisely because it can shed light on this issue, evaluating the instrument’s invariance is extremely relevant (Chen, 2008).

In the present study, we conducted invariance analysis on the configural, metric, and scalar models. For understanding, the configural model assesses whether the instrument’s structure, i.e., its configuration, is adequate for both analyzed groups. When invariance is not accepted in this model, it means that the items load on different factors for each group. The metric model assesses whether the factor loadings of the items are statistically equal for both groups. When this is not accepted, it means that the items do not have the same importance for the instrument in both groups, indicating bias in responses to the items by one of the groups; hence, any mean comparison will be biased. Lastly, the scalar model assesses whether the latent trait level to respond to a certain item is equivalent between groups. When this is not accepted, it means that one of the groups may endorse an item more easily than the other (Damásio, 2013; Milfont & Fischer, 2010).

Thus, according to the description of the models, it becomes evident that comparative studies between genders, different age groups, and different nationalities are capable of reflecting real differences or similarities between the groups if the instrument used is equivalent across the groups. After all, the invariance accepted in the configural model pertains to the correct configuration of items in the model, and the invariance in the metric model only indicates that the factor loadings are statistically equivalent, while the invariance in the scalar model indicates that the items truly assess the latent trait of individuals belonging to both groups in an equivalent manner. Therefore, despite the relevance of each evaluated model, direct and unbiased comparisons between groups due to measurement error are only possible when all three levels of invariance are accepted (Fischer & Karl, 2019; Milfont & Fischer, 2010).

In the present study, scalar equivalence of the EFC was accepted between adolescents and adults in the IS, CS, TS, HS, and ITS factors, between male and female adolescents in the TS factor, and between men and women in the CS, TS, HS, and ITS factors. As explained, these results suggest that mean comparisons in personal strengths between the groups are possible in those belonging to these aforementioned factors (e.g., humor between adolescents and adults; spirituality between male and female adolescents; prudence between men and women). Therefore, it can be stated that comparisons between character strengths belonging to factors that did not achieve scalar invariance between the evaluated groups are not possible, as they will not reflect real differences or similarities but rather errors and biases in the measurement instrument (Damásio, 2013; Fischer & Karl, 2019; Peixoto & Martins, 2021).

It is relevant to highlight that the SRS factor did not achieve configural invariance in any of the pairs of groups tested. Upon carefully investigating the results of the model, it was observed that some items behaved differently between the groups. In the comparison between adolescents and adults, item 60 (“I am a careful person”) obtained a factor loading < .30 for both groups. However, items 18 (“I always have a lot of energy”) and 53 (“I feel full of life”) had higher loadings for adults than for adolescents; this may indicate that, perhaps, for some adolescents, these items are not directly related to other self-regulation items but to other characteristics of their personality. In the comparison between genders in adolescents, items 18, 60, and 38 (“I remain calm even in difficult situations”) loaded adequately on the factor only for the female group. Previous studies have shown that female adolescents tend to score higher in self-regulation than male adolescents (Coyne et al., 2015; Sanchis-Sanchis et al., 2020; Tetering et al., 2020), so it is possible that the lack of configural invariance between groups is due to this difference. Regarding the comparison between genders in adults, item 60 had a very low factor loading for the male group (.167), and item 38 had a higher loading for women than for men. Both items involve questions related to calmness/care, and as the literature suggests, women tend to report more self-regulation strategies than men (Nolen-Hoeksema, 2012), which may justify the lack of invariance of this factor between groups.

The CS factor was also not invariant even at the configural level between the groups of adolescents. An observation of the factor loadings indicated that items 3 (“I do things in different ways”), 6 (“I make good judgments even in difficult situations”), 7 (“I think about different possibilities when making a decision”), 29 (“I think a lot before making a decision”), and 36 (“I analyze what people say before giving my opinion”) obtained loadings < .30 for the male adolescent group. Unlike items such as 35 (“I face dangers to do good”) which more directly reflect a positively oriented courage, the content of these items involves something closer to thinking/reflecting before acting. Therefore, it is possible that for the male adolescent group, these items are capturing a different type of content such as impulsivity control (Weinstein & Dannon, 2015).

Finally, the IS factor did not exhibit configural invariance between genders for adults. Item 10 (“I do not lie to please people”) obtained a factor loading < .30 for men (.222), but it also did not have a very high loading for women (.317). Because it is a positive item (in terms of the latent trait), but contains the word “not”, participants may have had difficulty interpreting the meaning of the sentence, which may have penalized the fit of the configural model and resulted in the non-invariance of the factor. However, item 33 (“I am a truthful person”) also showed a higher loading for women than for men, which may indicate that there may indeed be a difference in the functioning of item content between genders in adults beyond the issue pointed out for item 10.

Final considerations

The structure found by Noronha and Batista (2020) for EFC was replicated in the present study. This brings a new indication that this distribution of personal forces is empirically supported. Although item 3 did not cause significant harm to the model fit, its reformulation might be considered due to its low factor loading. Specifically, the item refers to creativity (“I do things in different ways”), and it is possible that the meaning of doing things differently has various interpretations, which may have impacted the results. It is unique that further studies be conducted, including additional applications of pilot studies.

Regarding factor invariance, the results indicated that only the TS factor exhibited scalar invariance across all group comparisons. However, in at least one group comparison, the other factors demonstrated complete invariance, except for the SRS factor, which was non-invariant in all group comparisons. This may suggest a prioritized revision of the items composing the SRS factor. The CS and IS factors also warrant attention in a future instrument revision, as the former did not function equivalently at any level between sex groupings in adolescents, and the same occurred with the latter in adults.

As a limitation of the present study, it can be noted that due to the number of items allocated for each character strength being less than four, it was not possible to assess the invariance of these strengths individually through MG-CFA (Czerwiński & Atroszko, 2021). It is recommended that future studies employ methods capable of evaluating the invariance of each strength separately.

References:

American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, & National Council on Measurement in Education. (2014). Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing: National Council on Measurement in Education. American Educational Research Association.

Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. (2010). Simple Second Order Chi-Square Correction. https://www.statmodel.com/download/WLSMV_new_chi21.pdf

Chen, F. F. (2007). Sensitivity of Goodness of Fit Indexes to Lack of Measurement Invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 14(3), 464-504. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705510701301834

Chen, F. F. (2008). What happens if we compare chopsticks with forks? The impact of making inappropriate comparisons in cross-cultural research. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 95(5), 1005. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013193

Cheung, G. W., & Rensvold, R. B. (2002). Evaluating Goodness-of-Fit Indexes for Testing Measurement Invariance. Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 9(2), 233-255. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15328007SEM0902_5

Coyne, M. A., Vaske, J. C., Boisvert, D. L., & Wright, J. P. (2015). Sex differences in the stability of self-regulation across childhood. Journal of Developmental and Life-Course Criminology, 1(1), 4-20. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40865-015-0001-6

Cronbach, L. J. (1951). Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika, 16, 297-334. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02310555

Czerwiński, S. K., & Atroszko, P. A. (2023). A solution for factorial validity testing of three-item scales: An example of tau-equivalent strict measurement invariance of three-item loneliness scale. Current Psychology, 42(2), 1652-1664. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-021-01554-5

Damásio, B. F. (2013). Contribuições da Análise Fatorial Confirmatória Multigrupo (AFCMG) na avaliação de invariância de instrumentos psicométricos. Psico-Usf, 18, 211-220. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-82712013000200005

Fischer, R., & Karl, J. A. (2019). A Primer to (Cross-Cultural) Multi-Group Invariance Testing Possibilities in R. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1507. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01507

Heintz, S., Kramm, C., & Ruch, W. (2019). A meta-analysis of gender differences in character strengths and age, nation, and measure as moderators. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 14(1), 103-112. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2017.1414297

Heintz, S., & Ruch, W. (2022). Cross-sectional age differences in 24 character strengths: Five meta-analyses from early adolescence to late adulthood. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 17(3), 356-374. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2021.1871938