10.22235/cp.v18i1.3286

Validación de un modelo de rasgos positivos y negativos de personalidad como predictores del bienestar psicológico aplicando algoritmos de machine learning

Validation of a model of positive and negative personality traits as predictors of psychological well-being using machine learning algorithms

Validação de um modelo de traços de personalidade positivos e negativoscomo preditores do bem-estar psicológico aplicando algoritmos de machine learning

Alejandro Castro Solano1, ORCID 0000-0002-4639-3706

María Laura Lupano Perugini2, ORCID 0000-0001-6090-0762

Micaela Ailén Caporiccio Trillo3, ORCID 0009-0006-8730-4008

Alejandro César Cosentino4, ORCID 0000-0002-7786-5470

1 U Universidad de Buenos Aires; Universidad de Palermo; Conicet, Argentina

2 Universidad de Buenos Aires; Universidad de Palermo; Conicet, Argentina, [email protected]

3 Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina

4 Universidad de Buenos Aires; Universidad de Palermo, Argentina

Resumen:

El objetivo de este estudio fue verificar un modelo predictivo de rasgos de personalidad positivos y negativos tomando como criterio el bienestar psicológico mediante la implementación de algoritmos de machine learning. Participaron 2038 sujetos adultos (51.9 % mujeres). Para la recolección de datos se utilizó: Big Five Inventory y Mental Health Continuum-Short Form. Además, para evaluar los rasgos positivos y negativos de personalidad se utilizaron los ítems ya validados de los modelos de rasgos positivos (HFM) y negativos (BAM) de forma conjunta. A partir de los hallazgos encontrados se pudo verificar que la eficacia predictiva del modelo testeado de rasgos positivos y negativos derivados de un enfoque léxico resultó superior a la capacidad predictiva de los rasgos normales de personalidad para la predicción del bienestar.

Palabras clave: rasgos positivos; rasgos negativos; personalidad; bienestar psicológico; algoritmos.

Abstract:

The objective of the study was to verify a predictive model of positive and negative personality traits taking psychological well-being as a criterion through the implementation of machine learning algorithms. 2038 adult subjects (51.9 % women) participated. For data collection were used: Big Five Inventory and Mental Health Continuum-Short Form. In addition, to assess the positive and negative personality traits, the already validated items of the positive (HFM) and negative trait models (BAM), were used jointly. Based on the findings found, it was possible to verify that the predictive efficacy of the tested model of positive and negative traits, derived from a lexical approach, was superior to the predictive capacity of normal personality traits for the prediction of well-being.

Keywords: positive traits; negative traits; personality; psychological well-being; algorithms.

Resumo:

O objetivo do estudo foi verificar um modelo preditivo de traços de personalidade positivos e negativos tendo como critério o bem-estar psicológico por meio da implementação de algoritmos de machine learning. Participaram 2.038 sujeitos adultos (51,9 % mulheres). Para a coleta de dados foram utilizados: Big Five Inventory e Mental Health Continuum-Short Form. Além disso, para avaliar os traços de personalidade positivos e negativos, foram utilizados conjuntamente os itens já validados dos modelos de traços positivos (HFM) e negativos (BAM). Foi possível verificar que a eficácia preditiva do modelo testado de traços positivos e negativos derivados de uma abordagem lexical foi superior à capacidade preditiva de traços normais de personalidade para a predição do bem-estar.

Palavras-chave: traços positivos, traços negativos, personalidade, bem-estar psicológico, algoritmos.

Recibido: 10/03/2023

Aceptado: 30/04/2024

Desde el siglo XX las características positivas y negativas de las personas se volvieron objeto de interés por parte de la psicología (McCullough & Snyder, 2000; Peterson & Seligman, 2004). Históricamente, se abordaron estas temáticas desde diferentes enfoques. Los enfoques empíricos, que se relacionan con el estudio de las características humanas, se pueden clasificar de dos maneras: guiados por las teorías (theory-driven) y guiados por los datos (data-driven). Los enfoques que son guiados por las teorías diseñan a priori un modelo teórico, que luego se intenta corroborar con datos empíricos. Los enfoques guiados por los datos se caracterizan por ser estudios en los que se analizan datos empíricos con el objetivo de identificar agrupaciones de elementos (por ejemplo, características positivas) para encontrar una generalización de estos para conseguir su replicación en diferentes poblaciones (Chow, 2002).

En cuanto a las características positivas, existen varios modelos que exploraron y estudiaron esta temática. La clasificación de virtudes y fortalezas de Peterson y Seligman (2004) se encuentra dentro de la categoría de enfoques guiados por las teorías. Los autores propusieron un listado de 24 fortalezas del carácter, correspondiente con seis virtudes (coraje, justicia, humanidad, sabiduría, templanza y trascendencia). Más recientemente, Kaufman et al. (2019) propusieron un modelo de rasgos positivos denominado Light Triad (por oposición al modelo de rasgos oscuros Dark Triad; Paulhus & Williams, 2002), que incluye tres rasgos: kantianismo (rasgos orientados a tratar a los demás como fines en sí mismos y no como medios para un fin), humanismo (rasgos orientados a respetar la dignidad y valor de cada individuo) y confianza en la humanidad (rasgos orientados a creer y confiar en la bondad de los otros).

En cuanto a enfoques guiados por los datos se pueden citar varios ejemplos. Por un lado, Walker y Pitts (1998) buscaron analizar las concepciones sobre la excelencia moral, solicitando a los participantes que identifiquen atributos que posee una persona con elevada moral. Con esos datos, generaron un conjunto de descriptores morales. Se hallaron seis agrupaciones de atributos: idealista basado en principios, confiable y leal, íntegro, bondadoso, justo y, por último, confidente. Por su parte, Cawley et al. (2000) identificaron 140 palabras del diccionario que tenían correspondencia con las virtudes morales. Con estos adjetivos y sustantivos, y a través de procedimientos de análisis factorial, los autores encontraron cuatro dimensiones de virtudes positivas: empatía, orden, ingenioso y sereno. De Raad y van Oudenhoven (2011), utilizando una aproximación psicoléxica, solicitaron a estudiantes y psicólogos que identificaran palabras que describieran virtudes de una serie de términos del diccionario. De este estudio surgió un modelo seis factores de virtudes: sociabilidad, logro, respeto, vigor, altruismo y prudencia. Otro estudio data-driven fue el realizado por Morales-Vives et al. (2014). Los autores identificaron 209 descriptores de virtudes. Como resultado de este procedimiento se propuso un modelo de siete dimensiones: autoconfianza, reflexión, serenidad, rectitud, perseverancia y esfuerzo, compasión y sociabilidad.

Más recientemente, Cosentino y Castro Solano (2017) exploraron las características positivas humanas también desde un acercamiento psicoléxica. Este tipo de aproximación fue empleada por primera vez por Allport y Odbert (1936), y otorga un lugar fundamental al léxico, como una base con la cual se puede construir una clasificación de las diferencias humanas (De la Iglesia & Castro Solano, 2020). En un primer estudio, Cosentino y Castro Solano (2017) identificaron las características positivas desde el punto de vista de las personas comunes con el objetivo de desarrollar un modelo de factores de rasgos positivos humanos, compartidos socialmente, y que pudiera ser replicable en otras poblaciones. Esta investigación resultó novedosa, debido a que los estudios anteriores se centraron solamente en las características asociadas a rasgos morales, en tanto que los talentos y habilidades habían sido excluidos de manera sistemática. Este modelo incluyó estas características de manera más amplia, abarcando las relacionadas con la performance (como la inteligencia).

Dicha investigación dio como resultado el Modelo de los Cinco Altos o High Five Model (HFM) (Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2017). Se encontraron cinco rasgos presentes de manera relativamente estable, que varían en cada individuo, se pueden medir y, además, incrementar o reducirse por influencias internas o externas. Según los autores, los cinco factores del HFM son: erudición (un rasgo asociado a pensar soluciones, tener deseos de aprender), paz (se asocia a pensar en calma y confiar en que las cosas van a seguir su curso natural), jovialidad (se expresa en deseos de hacer reír a los demás, de divertirse y divertir a los otros), honestidad (se asocia con mostrarse transparente y tener una tendencia a decir la verdad) y tenacidad (se expresa en perseguir metas y buscar cumplir objetivos con esfuerzo).

Por otro lado, también la psicología se interesó por las características negativas de la personalidad humana. Los estudios que proponen modelos de rasgos negativos han utilizado en general un enfoque guiado por las teorías. Un modelo que generó gran interés es el de la Tríada Oscura de Personalidad o Dark Triad (Paulhus & Williams, 2002), que propone tres rasgos negativos, pero no patológicos de la personalidad (maquiavelismo, narcisismo y psicopatía). Este modelo fue ampliado luego de su creación para incluir una nueva dimensión: sadismo (Jones & Paulhus, 2014).

Cosentino y Castro Solano (2023) propusieron un modelo de las características negativas desde la perspectiva de las personas comunes, así como el modelo de rasgos positivos. Utilizando el enfoque psicoléxico, encontraron tres factores que mostraron un buen ajuste de datos. Se denominó a este modelo derivado inductivamente brutalismo, arrogantismo y malignismo (BAM). Los tres factores son: brutalismo (individuos descuidados, inestables, groseros, insoportables), arrogantismo (sujetos arrogantes, engreídos, presumidos y pedantes) y malignismo (personas tramposas, que realizan actos inmorales, mezquinos, rencorosos, etc.). Este modelo es más reciente que el modelo de los rasgos positivos de la personalidad y se encuentra en su fase de validación.

Bienestar y modelos de personalidad positiva y negativa

El estudio del vínculo entre la personalidad y el bienestar ha sido muy estudiado, ya que los rasgos de personalidad se consideran los predictores más conocidos de las experiencias subjetivas (Tkach & Lyubomirsky, 2006). Las investigaciones clásicas que intentaron explicar el bienestar desde las variables de personalidad consideraron mayormente los rasgos de personalidad normal (Anglim et al, 2020), principalmente desde el Five Factor Model (FFM; Costa & McCrae, 1984). Sin embargo, en los últimos años se ha comenzado a prestar atención a la relación con rasgos negativos (Blasco-Belled et al., 2024) y positivos de la personalidad (Kaufman et al., 2019).

En la presente investigación se aborda el bienestar desde la perspectiva de Keyes (2002, 2005), ya que es una de las más empleadas en los estudios internacionales. El autor entiende a la salud mental como un continuo denominado languishing-flourishing en el que los individuos se pueden clasificar en tres grupos: languishing, integrado por sujetos que presentan dificultades en la vida, falta de compromiso, sentimiento de vacío; flourishing, sujetos que tienen un desarrollo óptimo en su vida; y, por último, moderate mental health, que está formado por sujetos que no entran en las dos clasificaciones anteriores, presentando un nivel moderado. Este modelo comprende, entonces, a la salud y a la enfermedad como un continuo a través de la presencia o ausencia, además del grado de bienestar hedónico (emocional) y eudaemónico (bienestar social y psicológico).

En cuanto a la relación entre bienestar y los rasgos del FFM, un meta-análisis reciente (Anglim et al., 2020) reporta que los rasgos que muestran mayor asociación con el bienestar tanto hedónico como eudaemónico son el neuroticismo, la extraversión y la responsabilidad.

Si se considera los rasgos positivos de personalidad, algunos estudios muestran que el modelo de fortalezas del carácter de Peterson y Seligman (2004; Park et al., 2004) permite predecir la satisfacción con la vida, siendo las fortalezas esperanza, gratitud, curiosidad y amor las más asociadas. Asimismo, tomando el modelo más reciente de Kaufman et al. (2019), se halló que los tres rasgos luminosos que correlacionan de forma positiva son la satisfacción con la vida con el bienestar global (Kaufman et al., 2019; Stavraki et al., 2023).

En relación con el modelo de rasgos positivos analizado en esta investigación —el modelo de los Cinco Altos—, los estudios previos demostraron que estos factores de personalidad positiva tenían validez incremental para predecir el bienestar psicológico (hedónico y eudamónico) por sobre el modelo del FFM (Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2017). Además, otro estudio demostró que estos factores se asociaban negativamente con indicadores de sintomatología psicológica, bajo riesgo de contraer enfermedades médicas y con rasgos patológicos de la personalidad (Castro Solano & Cosentino, 2017). Particularmente, los rasgos paz y jovialidad eran los rasgos más fuertemente asociados con el bajo riesgo de contraer tanto enfermedades médicas como psicológicas. En otro estudio realizado con estudiantes universitarios se pudo verificar que los factores altos, además de ser promotores del bienestar psicológico, permitían predecir tanto la adaptación a la vida universitaria como el rendimiento académico de los estudiantes (Castro Solano & Cosentino, 2019). En este caso, la tenacidad y la erudición eran los dos factores de personalidad positivos más fuertemente asociados con la percepción de ajuste a la vida universitaria.

En cuanto a antecedentes que relacionan el bienestar con rasgos de personalidad negativa, estudios realizados con el modelo de la Tríada Oscura dan cuenta de que los rasgos maquiavelismo y psicopatía son los que mejor predicen de forma negativa el bienestar, sobre todo, de carácter eudaemónico (Liu et al., 2021). Un metaanálisis reciente, que incluyó el análisis de 55 estudios que trabajaron con modelos de personalidad negativa, reportó que el antagonismo, la desinhibición y el maquiavelismo se relacionaron con los niveles más bajos de bienestar. Asimismo, mostraron que la edad y el género moderaron algunas de estas asociaciones (Blasco-Belled et al., 2024).

Si se considera el modelo de rasgos negativos analizado en esta investigación —el modelo BAM—, resultados previos mostraron asociaciones negativas con la satisfacción con la vida, y positivas con síntomas psicopatológicos (Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2023).

La presente investigación

El propósito de esta investigación es estudiar de forma conjunta un modelo de rasgos positivos y negativos derivados de un enfoque psicoléxico para la predicción del bienestar psicológico tanto hedónico como eudaemónico. En relación con los rasgos positivos se consideró el modelo de los Cinco Altos (Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2017). En relación con los rasgos negativos de la personalidad se tomó un modelo de características psicoléxicas especialmente diseñado para la población local (Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2023).

De acuerdo con lo expuesto, las razones por las cuales se escogen estos modelos son, por un lado, que los modelos de personalidad más modernos (e.g., rasgos positivos y negativos) agregan variancia adicional para la explicación del bienestar psicológico por sobre los modelos de personalidad clásicos (Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2017; Castro Solano & Cosentino, 2019). Por otro lado, ambos modelos han sido desarrollados localmente, desde un enfoque psicoléxico, lo que disminuye el riesgo de caer en una perspectiva ética-impuesta, dado que la equivalencia cultural de algunos constructos psicológicos (e,g., características positivas) es tema de debate constante (Lopez et al., 2002).

Una novedad de este estudio refiere a la utilización de algoritmos de machine learning (aprendizaje automático). Desde hace algunos años estos algoritmos se han popularizado en psicología, especialmente con propósitos predictivos (Yarkoni & Westfall, 2017), ya que permiten descubrir patrones y desarrollar modelos predictivos en una variedad de circunstancias y campos de aplicación de la psicología, tales como la psicometría, la psicología experimental, el diagnóstico, el tratamiento, el seguimiento y la atención personalizada de los pacientes (Dey, 2016; Dhall et al., 2020; Dwyer et al, 2018; Jacobucci & Grimm, 2020; Koul et al., 2018; Lin et al., 2020; Orrù et al., 2020; Shatte et al., 2019). Por ejemplo, algunas investigaciones que usaron algoritmos de aprendizaje automático permitieron identificar rasgos de personalidad a través de posteos en redes sociales (Bleidorn & Hopwood, 2019; Park et al., 2015), o de la música preferida según los likes en Facebook (Nave et al., 2018). En el ámbito clínico, un estudio reciente, a través de algoritmos de aprendizaje automático, pudo identificar predictores específicos de las experiencias de afrontamiento de un amplio grupo de pacientes que realizaban un tratamiento cognitivo conductual (Gómez Penedo et al., 2022).

Por lo tanto, los aportes de esta investigación recaen, por un lado, en el plano teórico, ya que las investigaciones clásicas que explicaron el bienestar desde las variables de personalidad consideraron mayormente los rasgos de personalidad normal desde el FFM o derivaciones de este (Anglim et al., 2020). En este caso, la contribución principal de este estudio es el aporte de un modelo que incluye otras variables de personalidad no analizadas comúnmente y que han tomado relevancia en el campo de estudio de la personalidad: rasgos negativos y rasgos positivos. Utilizar modelos que consideren nuevas variables de personalidad permite incrementar la predicción del bienestar (mayor variancia explicada frente a los modelos tradicionales). A esto se agrega que se propone probar el funcionamiento integrado de rasgos positivos y negativos en un mismo modelo.

Por otro lado, desde el punto de vista metodológico, el aporte recae en la inclusión de algoritmos de machine learning para la explicación de las variables criterio (bienestar psicológico, emocional y social). Los algoritmos clasificatorios ayudan a mejorar, desde el punto de vista metodológico, la predicción al identificar subgrupos de sujetos específicos. Por su parte, los algoritmos predictivos permiten: a) ejecutar los análisis con menos supuestos estadísticos (e.g. normalidad, homogeneidad de variancia), b) considerar una amplia cantidad de variables sin afectar los resultados (alta dimensionalidad), c) estimar la capacidad de generalización de los resultados mediante técnicas de validación cruzada, técnica muy robusta en la cual se dividen los datos en fases de entrenamiento y en fases de test, siendo en esta última en la que se prueban si los resultados entrenados son válidos en otra muestra diferente (Dwyer et al, 2018). Este último procedimiento y la incorporación de técnicas de regularización (hiperparámetros en las regresiones Lasso y Ridge) resultan muy superiores a la utilización de las regresiones lineales clásicas, ya que permiten mejorar la exactitud y la capacidad de generalización de los resultados (Delgadillo et al., 2020; Zou & Hastie, 2005).

A partir de lo expuesto, los objetivos de este estudio son: (1) Verificar un modelo predictivo de rasgos de la personalidad positivos y negativos tomando como criterio el bienestar psicológico (personal, emocional y social) mediante la implementación de algoritmos de aprendizaje automático (regularización Lasso, Ridge y Random Forest); (2) Verificar la eficacia predictiva del modelo de personalidad de rasgos positivos y negativos por sobre el modelo de los rasgos de personalidad normal, tomando como criterio el bienestar psicológico (personal, emocional y social) mediante la implementación de algoritmos de aprendizaje automático (regularización Lasso, Ridge y Random Forest); (3) Verificar la precisión, la sensibilidad y la especificidad del modelo predictivo de los rasgos de personalidad positivos y negativos para identificar correctamente personas con alto y bajo bienestar psicológico utilizando algoritmos de aprendizaje automático (máquina de vectores de soporte).

Método

Participantes

Los sujetos participaron de forma voluntaria y anónima. Se utilizó como criterio de inclusión que fueran ciudadanos argentinos y mayores de edad (a partir de los 18 años). La muestra final estuvo constituida por un total de 2038 participantes. El 51.9 % (n = 1058) fueron mujeres y el 48.1 % (n = 980) varones. La edad promedio era de 40.4 (DE = 14.7), con edades entre los 18 y los 91 años. En cuanto al estado civil, el 33.2 % (n = 676) estaba soltero, el 16.5 % (n = 336) estaba de novio, el 26.1 % (n = 531) se encontraba casado o unido, el 20.4 % (n = 416) declaró estar divorciado o separado, mientras que el 3.9 % (n = 79) era viudo. En relación a sus ocupaciones, el 53.4 % (n = 1088) eran empleados, el 18.3 % (n = 374) no se encontraba activamente trabajando en el momento de realizar la encuesta, 20.1 % (n = 409) declararon trabajar por su cuenta, el 0.5 % (n = 11) eran trabajadores que no percibían salario, el 2.6 % (n = 54) eran ama/o de casa, mientras que el 5 % (n = 102) eran empleadores. Por último, en relación al nivel socioeconómico, el 2.0 % (n = 40) pertenecía a un nivel bajo, el 14.3 % (n = 292) formaba parte de un nivel medio-bajo, el 63.5 % (n = 1294) a un nivel medio, el 17.8 % (n = 363) declaró pertenecer a un nivel medio alto y el 2.4 % (n = 49) de la muestra pertenecía un nivel socioeconómico alto.

Materiales

Big Five Inventory (BFI; John et al., 1991; adaptación argentina Castro Solano & Casullo, 2001). Consiste en un instrumento de 44 ítems que evalúa los cinco grandes rasgos de personalidad (extraversión, agradabilidad, responsabilidad, neuroticismo, apertura a la experiencia). El autor de la técnica demostró su validez y fiabilidad en grupos de población general adulta norteamericana. Esos estudios verificaron la validez concurrente con otros instrumentos reconocidos que evalúan personalidad. Estudios realizados en Argentina verificaron la validez factorial de los instrumentos para población adolescente, población adulta no consultante y población militar (Castro Solano & Casullo, 2001). En todos los casos se obtuvo un modelo de cinco factores que explicaban alrededor del 50 % de la variancia de las puntuaciones. Para esta muestra se obtuvieron valores de consistencia interna adecuados (ordinal alpha): extraversión = .76; agradabilidad = .79; responsabilidad = .82; neuroticismo = .74; apertura a la experiencia = .69.

Mental Health Continuum- Short Form (MHC-SF; Keyes, 2005; adaptación argentina de Lupano Perugini et al., 2017). Este instrumento de 14 ítems evalúa el grado de: a) bienestar emocional, entendido en términos de afectos positivos y satisfacción con la vida (bienestar hedónico); b) bienestar social (incluye las facetas de aceptación, actualización, contribución social, coherencia e integración social); c) bienestar personal en términos de la teoría de Ryff (1989; autonomía, control, crecimiento personal, relaciones personales, autoaceptación y propósito). El MHC-SF ha mostrado buenas evidencias de consistencia interna (> .70) y validez discriminante en muestras de adultos de diversos países. La estructura de tres factores de la escala (emocional, psicológica y social) ha sido verificada en dichos estudios. Los estudios de validación de este instrumento en Argentina han confirmado la estructura factorial del instrumento y han dado evidencia de una buena validez convergente y consistencia interna en población adulta (Lupano Perugini et al., 2017). La fiabilidad por escala para esta muestra fue (ordinal alpha): bienestar emocional = .80; bienestar social = .74; bienestar personal = .77.

Rasgos positivos y negativos de la personalidad

Para evaluar los rasgos positivos y negativos de la personalidad desde un punto de vista psicoléxico se utilizaron los ítems ya validados de los modelos de rasgos de personalidad positivos (Modelo de los Cinco Altos [HFM], Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2017) y los derivados del modelo de rasgos negativos (BAM; Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2023), de forma conjunta.

Modelo de los Cinco Altos (rasgos positivos; Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2017). Para evaluar los rasgos positivos de la personalidad se tomaron en cuenta el modelo HFM, a través de los ítems de la escala High Factor Inventory (HFI). La escala está compuesta por 23 ítems que evalúan los cinco factores altos: erudición, paz, jovialidad, honestidad y tenacidad. Estos factores fueron obtenidos mediante un procedimiento inductivo que partió del punto de vista de las personas comunes sobre las características humanas positivas. Se pide a las personas que respondan a cada ítem, por ejemplo, “Tengo paciencia” en una escala Likert que va de 1 (nunca) a 7 (siempre). A mayor puntuación de cada subescala, más elevado factor alto. Los estudios sobre el HFI demostraron validez convergente y divergente en relación con la clasificación Values in Action de Peterson y Seligman (2004) e incremental por sobre los factores y facetas del modelo de los cinco grandes de la personalidad para la predicción del bienestar psicológico, emocional y social. Para esta muestra se obtuvieron valores de consistencia interna adecuados (ordinal alpha): erudición = .84, paz =.86, jovialidad =.88, honestidad =.88 y tenacidad =.86.

Modelo BAM (rasgos negativos; Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2023). Para evaluar los rasgos negativos de la personalidad se tomó en cuenta el modelo de rasgos negativos a través de los ítems del inventario BAM (Brutalismo, Arrogantismo, Malignismo). El modelo BAM es un modelo reciente que está compuesto por tres factores obtenidos de forma inductiva y que evalúan características negativas de la personalidad. El procedimiento inductivo siguió un enfoque psicoléxico a través de un corpus de palabras obtenidas a partir de personas comunes que relataban características consideradas “negativas” y que eran compartidas socialmente. El factor brutalismo está definido por un conjunto de rasgos individuales negativos como ser insoportable, descuidado, inestable, ridículo; el factor arrogantismo está definido por un conjunto de características negativas como ser arrogante, engreído, creído, narcisista y presumido; y el factor malignismo está definido por características como ser corrupto, embustero, inmoral, malintencionado y despreciable, entre otras. Se evalúa a los participantes pidiendo que respondan al ítem, por ejemplo, “Soy presumido” en una escala Likert que va de 1 (nunca) a 7 (siempre). En un estudio preliminar (Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2023) el modelo demostró buena validez de constructo y asociaciones positivas con síntomas y rasgos psicopatológicos y asociaciones negativas con la satisfacción de la vida. Asimismo, predijo esas características psicológicas mejor de lo que predice el modelo de la Tríada Oscura (Paulhus & Williams, 2002). Los 22 ítems del modelo se agrupan en 3 factores que fueron confirmados mediante técnicas de análisis factorial confirmatorio que demostraron un buen ajuste del modelo a los datos (estimador de mínimos cuadrados ponderados robusto (DWLS, robusto) χ2 (206) = 323.00, p < .05, estimadores de ajuste CFI = .986, SRMR = .060, RMSEA = .041 (90 % Confidence Interval = .032 - .049). Se decidió incluir este modelo de personalidad como complementario del modelo de rasgos positivos (HFI) con el propósito de seguir estudiando su validez predictiva. Para esta muestra se obtuvieron valores de consistencia interna adecuados (ordinal alpha): brutalismo = .85, arrogantismo =.91 y malignismo =.85.

Procedimiento

Los datos fueron recolectados por pasantes que se encontraban realizando una práctica de investigación en una universidad privada de la ciudad de Buenos Aires, Argentina. Los participantes fueron voluntarios y no recibieron retribución alguna por su colaboración. Los datos fueron recolectados durante el año 2021 y 2022. Los materiales se administraron online mediante la aplicación del servidor de encuestas SurveyMonkey. En la página de inicio de la encuesta se solicitaba el consentimiento del participante, se aseguraba el anonimato de los datos y su uso exclusivo para investigación. La recogida de los datos fue supervisada por uno de los autores de este artículo. La investigación siguió los lineamientos éticos internacionales (APA y NC3R) y del Consejo Nacional de Investigaciones Científicas y Técnicas (Conicet) para el comportamiento ético en las Ciencias Sociales y Humanidades (Resolución n.o 2857, 2006) y cuenta con la aprobación de los comités de ética correspondientes.

Para el análisis de los datos se utilizó el paquete estadístico Jamovi (2022) a través del entorno R, Versión 4.1.2 (R Core Team, 2021) para los cálculos de correlaciones y de regresión logística. Para el cálculo de los algoritmos de aprendizaje automático, se utilizó el software de uso libre R (R Core Team, 2021). Se utilizaron los paquetes caret, glmnet, randomForest y e107.

Análisis de datos

Se utilizaron diferentes algoritmos de aprendizaje automático con el propósito de validar un modelo de rasgos positivos y negativos de la personalidad para la predicción de los diferentes tipos de bienestar psicológico (objetivos de investigación 1 y 2), tomando como punto de partida el modelo de rasgos de personalidad normal.

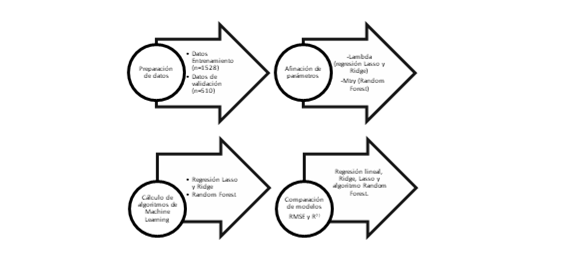

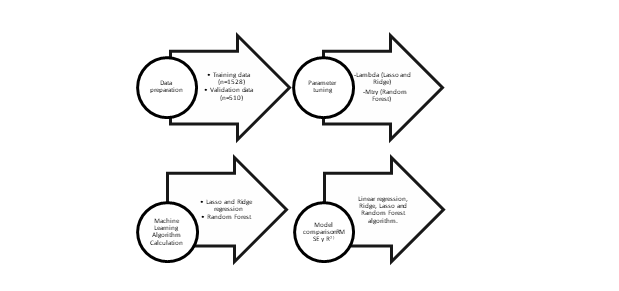

Como primer paso, se dividió aleatoriamente la muestra de participantes en dos subconjuntos. El primero de ellos se denominó conjunto de datos de entrenamiento (2/3 de los participantes, n = 1528), el segundo subconjunto se lo denominó conjunto de datos de validación (1/3 de la muestra, n = 510). Todas las variables continuas se transformaron a puntuaciones z.

Se trabajó con diferentes técnicas de regularización (regresión Lasso y regresión Ridge) para poder verificar la eficacia predictiva de dos modelos de personalidad (rasgos de personalidad normal vs. rasgos negativos y positivos) sobre el bienestar psicológico. Con propósitos de comparación, se llevó a cabo una regresión lineal (mínimos cuadrados ordinarios) en la que se incluyeron todos los predictores de ambos modelos (variables de personalidad) de forma conjunta. Las técnicas de regularización empleadas son extensiones de la regresión de mínimos cuadrados ordinarios e incluyen diferentes tipos de penalidades en los coeficientes de regresión con el propósito de mejorar la interpretación de los modelos (Zou & Hastie, 2005).

La regresión Ridge se utiliza el que caso en que haya multicolinealidad entre los predictores. La ventaja de este tipo de regresión es mantener a todos los predictores en el modelo y la desventaja es no producir modelos parsimoniosos por la razón comentada (Delgadillo et al., 2020; Friedman et al., 2010). La regularización Lasso se utiliza en los casos en que hay varios predictores con coeficientes cercanos a cero y algunos con coeficientes más amplios. Este tipo de regresión selecciona automáticamente los predictores relevantes al modelo y descarta los demás, y produce modelos más parsimoniosos e interpretables (Zou & Hastie, 2005).

Asimismo, se utilizó el algoritmo Random Forest, se trata de una técnica no paramétrica de partición recursiva que combina diferentes árboles de decisión predictores de forma tal que de cada árbol depende un vector aleatorio que se testea de forma independiente. La ventaja de esta metodología es que incorpora aleatoriamente predictores considerados débiles, generalmente ignorados en otros modelos debido a la dominancia de los predictores considerados más fuertes (Garge et al., 2013). Asimismo, esta metodología permite incluir un número más amplio de predictores. Difiere de la regularización Lasso y Ridge, ya que permite trabajar con asociaciones e interacciones complejas y relaciones no lineales. Lasso y Ridge tienen dos parámetros λ (lambda) y α (alfa). α se fija arbitrariamente en 1 para la regresión Lasso y en 0 para Ridge. El parámetro λ se calculó mediante la técnica de la validación cruzada. Para establecerlo se utilizó el paquete glmnet (Friedman, et al., 2010).

En el algoritmo Random Forest el parámetro a estimar es el mtry, que se define por el número de predictores que se asignan aleatoriamente a cada nodo. La afinación del parámetro se realizó mediante el paquete randomForest (Liaw & Wiener, 2002), mediante iteraciones sucesivas, para los modelos predictores seleccionados.

Seguidamente, se entrenaron los modelos utilizando el conjunto de datos de entrenamiento. Luego se compararon los modelos en términos de RMSE (raíz del error cuadrático medio) y el R2 con el propósito de seleccionar el modelo con mejor bondad de ajuste. Una vez realizado esto, se testeó el modelo en el conjunto de datos de validación y se compararon los resultados obtenidos en ambos conjuntos de datos. Se resumen en la Figura 1 los pasos llevados a cabo en el análisis de los datos.

Figura 1: Pasos realizados en el análisis de los datos

Un procedimiento similar se siguió para el objetivo 3. En este caso se trabajó con el algoritmo de máquina de vectores de soporte (Support Vector Machine, SVM). El SVM es un algoritmo de aprendizaje automático supervisado, muy robusto, que permite analizar datos tanto con propósitos de clasificación como de regresión (Gareth et al., 2013). Dado un conjunto de datos de entrenamiento en el que se incluyen una serie de predictores, siendo el criterio a predecir de clasificación binaria, el algoritmo permite establecer predicciones que se testean en una nueva muestra (conjunto de datos de validación o test set). El algoritmo tiene como tarea establecer un hiperplano que separe de la mejor forma posible ambas clases binarias (criterios a predecir, en esta investigación alto y bajo bienestar psicológico). La evaluación del modelo se realiza por la capacidad del algoritmo para poder predecir con mayor precisión la pertenencia a cada clase. El SVM tiene 4 parámetros (Kernel, Regularización – C -, gamma y épsilon) que en este caso fueron estimados mediante el paquete e1071. Con propósitos comparativos se estimó una regresión logística en la que se incluyeron los predictores de ambos modelos de personalidad y como criterio el pertenecer al grupo de alto y bajo bienestar.

Luego se compararon los indicadores de precisión, de sensibilidad y de especificidad obtenidos mediante regresión logística y mediante el SVM. El propósito de este procedimiento era poder establecer la capacidad predictiva de ambos modelos de personalidad sobre el bienestar psicológico.

Resultados

Modelos Predictivos del Bienestar con algoritmos Lasso, Ridge y Random Forest

En primer lugar, se calcularon las correlaciones entre las variables predictoras de ambos modelos (rasgos de personalidad normales, positivos y negativos) y los tres tipos de bienestar (emocional, personal, social y total) en el conjunto de datos de entrenamiento. Todas las correlaciones obtenidas entre las variables predictoras (rasgos de personalidad) y las variables criterio (tipos de bienestar) son significativas al p < .0001.

En segundo lugar, se calcularon los parámetros afinados de los tres algoritmos predictivos (Regresión Lasso, Ridge y Random Forest) del bienestar psicológico en función de los rasgos de personalidad normal y de los rasgos positivos y negativos de la personalidad. Tanto el parámetro λ de los modelos de regresión como el mtry del algoritmo Random Forest fueron afinados mediante la técnica de la validación cruzada.[1]

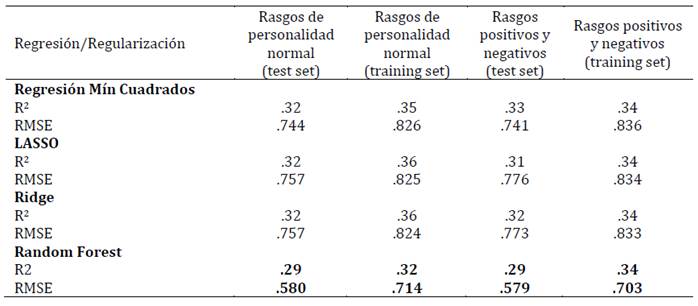

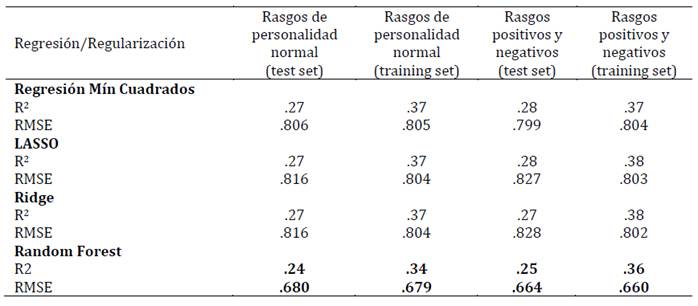

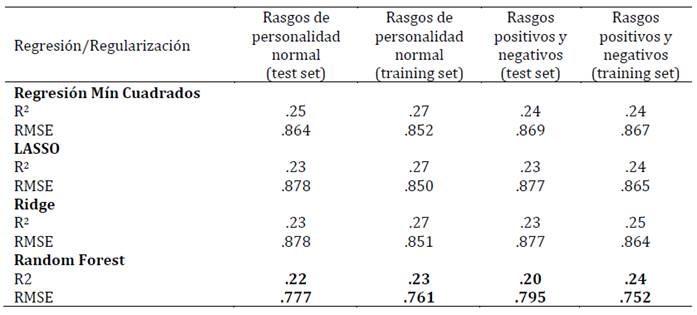

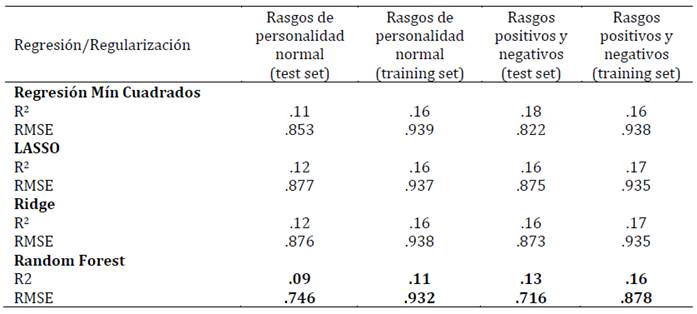

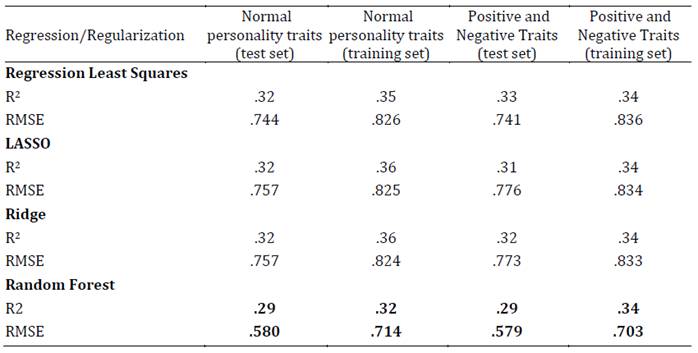

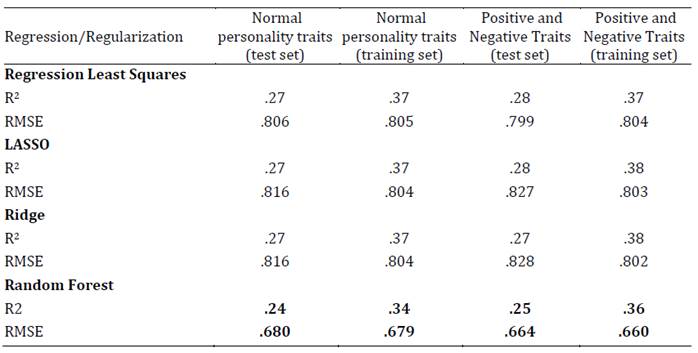

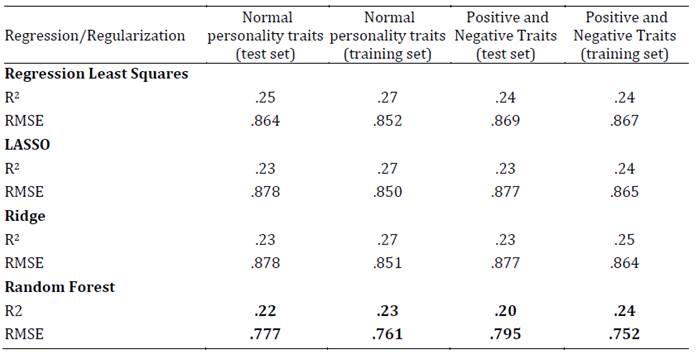

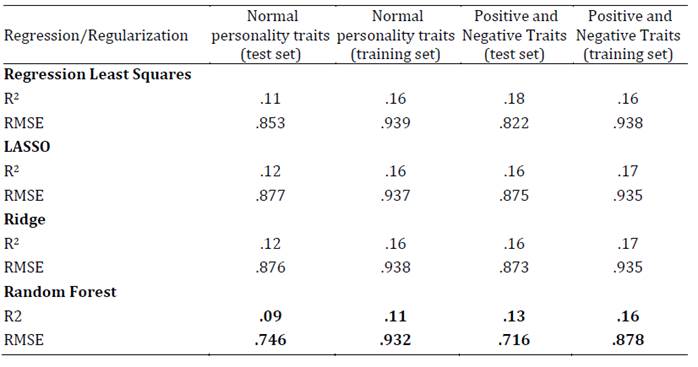

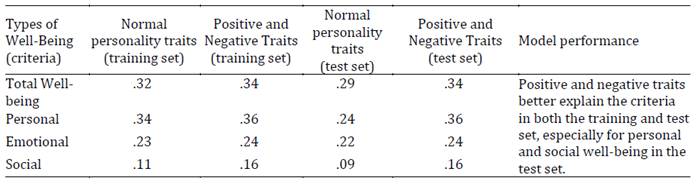

En tercer lugar, se presentan los resultados de los diferentes modelos, incluida la regresión lineal de mínimos cuadrados en términos del RMSE (raíz del error cuadrático medio) y el R2 (Tablas 1-4). Se considera como criterio de selección de modelo el que cuenta con mayor variancia explicada (mayor R2) y menor RMSE. Los resultados demuestran que el mejor modelo predictivo corresponde al algoritmo Random Forest. En el conjunto de datos de entrenamiento, tanto para el modelo de rasgos de personalidad normal (modelo base) como para el modelo de rasgos positivos y negativos (modelo a testear en esta investigación), el algoritmo Random Forest presentó el menor RMSE tanto para la predicción del bienestar total como para el bienestar emocional, personal y social.

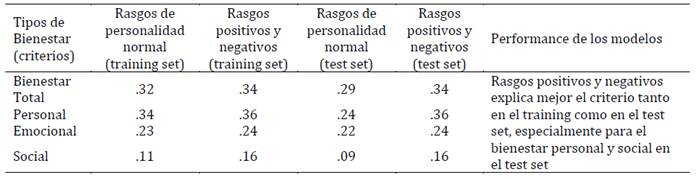

Estos resultados se validaron en otro conjunto de datos (test set) alcanzándose valores similares (validación cruzada). En esta submuestra de validación el algoritmo Random Forest presentó el menor RMSE tanto para la predicción del bienestar total como para el bienestar emocional, personal y social. Siendo, por lo tanto, este algoritmo el que tuvo una mejor performance para explicar el modelo a testear en la investigación (Tabla 5).

Para explorar la contribución de cada dimensión específica de la personalidad (rasgos) dentro de la técnica de Random Forest se calculó la media decreciente de Gini (i.e., IncNodePurity [INP]) para el modelo de rasgos positivos y negativos. Este índice demuestra que, para la predicción del bienestar total, los predictores más importantes resultaron ser la erudición (INP = 48.48) y la tenacidad (INP = 53.68). Los resultados son similares para el bienestar personal: TENACIDAD (INP = 57.40) y erudición (INP = 56.11). Para el bienestar emocional fueron tenacidad (INP = 65.66), paz (INP = 52.34) y malignismo (INP = 51.77), y para el social erudición (INP = 49.59) y paz (INP = 49.38).

Modelos predictivos del alto y bajo bienestar psicológico con el algoritmo de Support Vector Machine

Se utilizó el algoritmo Support Vector Machine (SVM) para predecir el bienestar psicológico tomando como predictores los modelos de personalidad normal y el modelo de rasgos positivos y negativos.

En primer lugar, se calcularon dos regresiones logísticas para ambos modelos tomando como variables predictoras los rasgos de personalidad normal y los rasgos positivos y negativos de personalidad. En ambos casos se consideró como criterio el alto/bajo bienestar. Para conformar esta última variable se convirtió la variable bienestar total en una variable dummy (0 = bajo bienestar; 1 = alto bienestar), tomando en cuenta la media (M = 3.05, DE = .86) en la puntuación de bienestar total para cada participante; por encima de la media se consideró alto bienestar y por debajo de la media se consideró bajo bienestar.

El modelo de los rasgos de personalidad normal (modelo base) fue estadísticamente significativo, χ2 (5, N = 1528) = 431.3.3, p < .001, esto indica que los cinco predictores que componen el modelo en conjunto permiten distinguir entre personas con alto y bajo bienestar psicológico. La varianza explicada era de 24.6 % (R2 de Cox y Snell). La precisión del modelo (porcentaje de predicciones positivas correctas) para identificar los casos de alto bienestar era de 72 %. La sensibilidad (porcentaje de casos de alto bienestar detectados) fue de 74 % y la especificidad (porcentaje de casos de bajo bienestar detectados) de 69 %. Todos los predictores del modelo (rasgos de personalidad) eran significativos (p < .001), siendo la extraversión y el neuroticismo los que registraban valores más elevados.

En segundo lugar, se utilizó el algoritmo SVM para establecer la eficiencia en la predicción de ambos modelos de la personalidad sobre el alto/bajo bienestar psicológico. Los parámetros utilizados fueron SVM del tipo de regresión, Kernel radial, gamma = .125 y épsilon = .01. Los vectores de soporte fueron 138. Los datos del SVM indican que la precisión de ambos modelos de personalidad es similar, así como los indicadores de sensibilidad y especificidad. La sensibilidad (porcentaje de casos de alto bienestar detectados) fue de 75 % y la especificidad (porcentaje de casos de bajo bienestar detectados) de 61 % tanto para el modelo de rasgos de personalidad normal como para el de rasgos positivos y negativos.

Tabla 1: Ajuste de los modelos para la predicción del bienestar total, según los Rasgos de personalidad normales, positivos y negativos (training set: n = 1528 y test set: n = 510)

Tabla 2: Ajuste de los modelos para la predicción del bienestar personal, según los rasgos de personalidad normales, positivos y negativos (training set: n = 1528 y test set: n = 510)

Tabla 3: Ajuste de los modelos para la predicción del bienestar emocional, según los rasgos de personalidad normales, positivos y negativos (training set: n = 1528 y test set: n = 510)

Tabla 4: Ajuste de los modelos para la predicción del bienestar social, según los rasgos de personalidad normales, positivos y negativos (training set: n = 1528 y test set: n = 510)

Tabla 5: Resumen del ajuste de los modelos (r2, random forest) para la predicción de los tipos de bienestar, según los rasgos de personalidad normales, positivos y negativos (training set: n = 1528 y test set: n = 510)

Discusión

Este estudio perseguía como objetivo principal poder verificar un modelo predictivo integrado de rasgos de la personalidad positivos y negativos tomando como criterio el bienestar psicológico (personal, emocional y social) mediante la implementación de algoritmos de aprendizaje automático.

A partir de tres algoritmos predictivos (Regresión Lasso, Ridge y Random Forest) se probó la eficacia predictiva del modelo testeado de rasgos positivos y negativos, derivados de un modelo léxico, que resultó similar e incluso algo superior a la capacidad predictiva del FFM para la predicción tanto del bienestar hedónico como eudaemónico.

En relación con la capacidad predictiva de cada uno de los rasgos positivos y negativos incluidos en el modelo integrado, se observó que todos resultaron predictores significativos a excepción de dos de los rasgos de personalidad negativos (brutalismo y arrogantismo). Como era de esperar, los rasgos positivos resultaron todos predictores significativos, tal como lo muestran los estudios previos realizados con el modelo de los Cincos Altos (HFM; Castro Solano & Cosentino, 2017, 2019; Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2017). Los rasgos que tenían más peso en la predicción del bienestar (total y personal) eran erudición y tenacidad, agregándose paz y malignismo para la predicción del bienestar emocional y personal. En términos generales, los rasgos positivos comentados (erudición y tenacidad) tenían un efecto protector sobre el bienestar psicológico. Este resultado confirma asimismo los hallazgos previos realizado con este mismo modelo de rasgos positivos en ocasión de predecir el ajuste académico a la vida universitaria (Castro Solano & Cosentino, 2019). Malignismo (e.g., corrupto, embusteros, malintencionado) es el rasgo negativo más vinculado conceptualmente con su equivalente maquiavelismo y psicopatía de la Tríada Oscura. Este resultado coincide con los estudios previos en los que estos rasgos negativos son aquellos que predicen mejor las asociaciones negativas con el bienestar, sobre todo, de carácter eudaemónico (e.g., Blasco-Belled et al., 2024; Liu at al., 2021). Finalmente, paz, que sería el opuesto de neuroticismo en el FFM, es el rasgo más asociado con el bienestar emocional y social. Estos hallazgos están en la línea de los estudios previos comentados sobre la relación entre rasgos de la personalidad y el bienestar.

Por otro lado, se utilizó el algoritmo Support Vector Machine para verificar la precisión, sensibilidad y especificidad del modelo predictivo de los rasgos de personalidad positivos y negativos para identificar correctamente personas con alto y bajo bienestar psicológico. Los resultados hallados muestran que, tanto para el modelo base (rasgos normales) como para el modelo testeado (rasgos positivos y negativo integrado), la precisión, la sensibilidad y la especificidad fueron similares. Debe destacarse que, de acuerdo a lo observado, puede inferirse que la especificidad, es decir, la capacidad de estos modelos de detectar casos de bajo bienestar es menor respecto de su sensibilidad y precisión. Esto puede estar influido por la menor capacidad predictiva que han mostrado los rasgos del modelo de rasgos negativos (BAM) —que suelen estar más asociados al bajo bienestar—, respecto del modelo de rasgos positivos (HFM) —más asociados al alto bienestar—. Razón por la cual en futuros estudios se deberá seguir estudiando la validez de contenido del inventario BAM a fin de identificar si los ítems son representativos del constructo evaluado.

La fortaleza del estudio presentado recae en dos aspectos centrales. Por un lado, se verifica un modelo integrado de rasgos positivos y negativos para la predicción del bienestar. Además, este modelo se ha desarrollado desde la aproximación psicoléxica que permite captar las variantes locales (émicas) y singulares de los constructos estudiados en cada cultura particular. Este aspecto no resulta menor dado el debate que se ha generado, principalmente, en cuanto a la universalización de algunos constructos positivos como el modelo de virtudes y fortalezas de Peterson y Seligman (2004) (Lopez et al., 2002). Muchos investigadores han advertido sobre los posibles sesgos etnocéntricos que pueden acarrearse al manejarse con clasificaciones desde una perspectiva ético-impuesta (Christopher & Hickinbotton, 2008; Snyder et al., 2011). Por ello la necesidad de generar modelos locales para la evaluación de este tipo de fenómenos que pueden estar influidos por aspectos culturales. La ventaja de este estudio, por sobre los ya realizados localmente, es que muestra el poder predictivo de estos rasgos en un modelo integrado. Si bien los antecedentes sobre otros modelos de rasgos positivos y negativos dan cuenta de que no se trata de rasgos opuestos o que puedan ser entendidos como un continuum (Kaufman et al., 2019), resulta interesante verificar su poder predictivo de forma conjunta.

Otra de las fortalezas de este estudio es la utilización de una metodología novedosa basada en algoritmos de machine learning con propósitos predictivos (Yarkoni & Westfall, 2017), lo que le aporta objetividad y rigurosidad a la investigación desarrollada. También es de destacar el amplio número de sujetos de la muestra, que permitió realizar técnicas de validación cruzada para seleccionar y estimar los mejores parámetros posibles de los modelos trabajados.

En cuanto a las limitaciones, se debe mencionar que para la recolección de los datos se han usado medidas de autoinforme que pueden estar influidas por una tendencia a responder de una forma socialmente deseable y afectar la validez de los datos y las inferencias realizadas. Otra de las limitaciones del trabajo es la selección de los algoritmos de aprendizaje automático, limitándose a los algoritmos basados en técnicas de regresión y de partición recursiva (Random Forest). Las metodologías actuales en el campo de la inteligencia artificial permiten incluso el uso de algoritmos muy sofisticados con propósitos predictivos que no se incluyeron en el presente estudio.

La inclusión tanto del modelo de rasgos positivos y negativos basados en un enfoque psicoléxico así como del uso de las técnicas de aprendizaje automático permiten avizorar un panorama muy prometedor para el tratamiento de las variables de personalidad como predictoras de una gran variedad de resultados psicológicos. Los instrumentos derivados de este modelo se componen de adjetivos que usan frecuentemente la personas para describirse a sí mismas y los demás, cuentan con validez ecológica y empírica y permiten valorar en pocos minutos importantes características psicológicas. En futuras investigaciones resultará interesante incluir estos predictores para valorar importantes resultados psicológicos en ámbitos aplicados específicos, tales como el laboral (e.g., predecir la satisfacción laboral, el compromiso y el flow en el trabajo), el académico (e.g., satisfacción con la elección vocacional) o incluso en el campo de los tratamientos psicológicos (e.g., satisfacción con la psicoterapia, eficacia de los tratamientos).

Referencias:

Allport, G. W. & Odbert, H. S. (1936). Trait-names: A psycholexical study. Psychological Monographs, 47(1), i-171. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0093360

Anglim, J., Horwood, S., Smillie, L. D., Marrero, R. J., & Wood, J. K. (2020). Predicting psychological and subjective well-being from personality: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 146(4), 279-323. https://doi.org/10.1037/bul0000226

Blasco-Belled, A., Tejada-Gallardo, C., Alsinet, C., & Rogoza, R. (2024). The links of subjective and psychological well-being with the Dark Triad traits: A meta-analysis. Journal of Personality, 92, 584-600. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12853

Bleidorn, W., & Hopwood, C. J. (2019). Using machine learning to advance personality assessment and theory. Personality and Social Psychology Review, 23(2), 190-203. https://doi.org/10.1177/1088868318772990

Castro Solano, A., & Casullo, M. M. (2001). Rasgos de personalidad, bienestar psicológico y rendimiento académico en adolescentes argentinos. Interdisciplinaria 18, 65–85.

Castro Solano, A., & Cosentino, A. (2017). High Five Model: Los factores altos están asociados con bajo riesgo de enfermedades médicas, mentales y de personalidad. Psicodebate. Psicología, Cultura y Sociedad, 17(2), 69-82. https://doi.org/10.18682/pd.v17i2.712

Castro Solano, A., & Cosentino, A. (2019). The High Five Model: Associations of the high factors with complete mental well-being and academic adjustment in university students. Europe’s Journal of Psychology, 15(4), 656–670. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v15i4.1759

Cawley, M. J., Martin, J. E., & Johnson, J. A. (2000). A virtues approach to personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 28(5), 997-1013. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0191-8869(99)00207-x

Chow, S. L. (2002). Methods in psychological research. Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems.

Christopher, J. C., & Hickinbottom, S. (2008). Positive psychology, ethnocentrism, and the disguised ideology of individualism. Theory & Psychology, 18(5), 563-589. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959354308093396

Cosentino, A., & Castro Solano, A. (2017). The High Five: Associations of the five positive factors with the Big Five and well-being. Frontiers in Psychology, 8, e1250. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2017.01250

Cosentino, A., & Castro Solano, A. (2023, en prensa). An Inductively derived Model of Negative Personality Traits. Testing, Psychometrics, Methodology in Applied Psychology.

Costa, P. T., & McCrae, R. R. (1984). The NEO Personality Inventory Manual. Psychological Assessment Resources. https://doi.org/10.1007/springerreference_184625

De la Iglesia, G. & Castro Solano A. (2020). Inventario de los Cinco Continuos de la Personalidad –ICCP-. Evaluación de Rasgos Positivos y Patológicos de la Personalidad. Paidós Informatizados.

De Raad, B., & Van Oudenhoven, J. P. (2011). A psycholexical Study of Virtues in the Dutch Language, and Relations between Virtues and Personality. European Journal of Personality, 25(1), 43-52. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.777

Delgadillo, J., & Gonzalez Salas Duhne, P. (2020). Targeted prescription of cognitive–behavioral therapy versus person-centered counseling for depression using a machine learning approach. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 88(1), 14-24. https://doi.org/10.1037/ccp0000476

Dey, A. (2016). Machine Learning Algorithms: A review. International Journal of Computer Science and Information Technologies, 7(3), 1174-1179.

Dhall, D., Kaur, R., & Juneja, M. (2020). Machine Learning: A review of the algorithms and its applications. En P. Singh, A. Kar, Y. Singh, M. Kolekar, & S. Tanwar (Eds.), Proceedings of ICRIC 2019. Lecture Notes in Electrical Engineering (pp. 47-63). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/9 78-3-030-29407-6_5

Dwyer, D. B., Falkai, P., & Koutsouleris, N. (2018). Machine Learning approaches for clinical psychology and psychiatry. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 14, 91-118. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032816-045037

Friedman, J., Hastie, T., & Tibshirani, R. (2010). Regularization paths for generalized linear models via coordinate descent. Journal of Statistical Software, 33(1), 1-22. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v033.i01

Gareth, J., Daniela, W., Trevor, H., & Robert, T. (2013). An introduction to statistical learning: with applications in R. Spinger. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9868.2005.00503.x

Garge, N. R., Bobashev, G., & Eggleston, B. (2013). Random forest methodology for model-based recursive partitioning: the mobForest package for R. BMC bioinformatics, 14(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2105-14-125

Gómez Penedo, J. M., Schwartz, B., Giesemann, J., Rubel, J. A., Deisenhofer, A. K., & Lutz, W. (2022). For whom should psychotherapy focus on problem coping? A machine learning algorithm for treatment personalization. Psychotherapy Research, 32(2), 151-164. https://doi.org/10.1080/10503307.2021.1930242

Jacobucci, R., & Grimm, K. J. (2020). Machine Learning and psychological research: the unexplored effect of measurement. Perspectives on Psychological Science: a Journal of the Association for Psychological Science, 15(3), 809-816. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691620902467

John, O. P., Donahue, E. M., & Kentle, R. L. (1991). Big Five Inventory (BFI) [Database record]. APA PsycTests. https://doi.org/10.1037/t07550-000

Jones, D. N., & Paulhus, D. L. (2014). Introducing the short dark triad (SD3) a brief measure of dark personality traits. Assessment, 21(1), 28-41. https://doi.org/10.1177/1073191113514105

Kaufman S. B., Yaden D. B., Hyde, E., & Tsukayama, E. (2019). The light vs. dark triad of personality: contrasting two very different profiles of human nature. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, e467. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00467

Keyes, C. L. M. (2002). The mental health continuum: From languishing to flourishing in life. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 43, 207-222. https://doi.org/10.2307/3090197

Keyes, C. L. M. (2005). The subjective well-being of America’s youth: toward a comprehensive assessment. Adolescent and Family Health, 4, 3-11.

Koul, A., Becchio, C., & Cavallo, A. (2018). PredPsych: A toolbox for predictive machine learning-based approach in experimental psychology research. Behavior research methods, 50(4), 1657-1672. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-017-0987-2

Liaw, A., & Wiener, M. (2002). Classification and regression by randomForest. R news, 2(3), 18-22.

Lin, E., Lin, C. H., & Lane, H. Y. (2020). Precision psychiatry applications with pharmacogenomics: artificial intelligence and Machine Learning approaches. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 21(3), 969. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms21030969

Liu, Y., Zhao, N., & Ma, M. (2021). The Dark Triad Traits and the Prediction of Eudaimonic Wellbeing. Frontiers in Psychology, 12, 693778. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.693778

Lopez, S. J., Prosser, E. C., Edwards, L. M., Magyar-Moe, J. L., Neufeld, J. E., & Rasmussen, H. N. (2002). Putting positive psychology in a multicultural context. En C. R. Snyder & S. J. Lopez (Eds.), Handbook of positive psychology (pp. 700–714). Oxford University Press.

Lupano Perugini M. L., de la Iglesia, G., Castro Solano A., & Keyes, C. L. M. (2017). The Mental Health Continuum-Short Form (MHC-SF) in the Argentinean context: confirmatory factor analysis and measurement invariance. Europe Journal of Psychology, 13, 93-108. https://doi.org/10.5964/ejop.v13i1.1163

McCullough, M. E., & Snyder, C. R. (2000). Classical source of human strength: revisiting an old home and building a new one. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 19, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.2000.19.1.1

Morales-Vives, F., De Raad, B., & Vigil-Colet, A. (2014). Psycho-lexically based virtue factors in Spain and their relation with personality traits. The Journal of General Psychology, 141(4), 297-325. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221309.2014.938719

Nave, G., Minxha, J., Greenberg, D. M., Kosinski, M., Stillwell, D., & Rentfrow, J. (2018). Musical preferences predict personality: evidence from active listening and Facebook likes. Psychological Science, 29(7), 1145-1158. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797618761659

Orrù, G., Monaro, M., Conversano, C., Gemignani, A., & Sartori, G. (2020). Machine Learning in psychometrics and psychological research. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 2970. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.02970

Park, G., Schwartz, H. A., Eichstaedt, J. C., Kern, M. L., Kosinski, M., Stillwell, D. J., & Seligman, M. E. (2015). Automatic personality assessment through social media language. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 108(6), 934. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspp0000020

Park, N., Peterson, C. & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Strengths of character and well-being. Journal of Social and Clinical Psychology, 23(5), 603-619. https://doi.org/10.1521/jscp.23.5.603.50748

Paulhus, D. L., & Williams, K. M. (2002). The dark triad of personality: narcissism, machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 36, 556-563. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00505-6

Peterson, C. & Seligman, M. E. P. (2004). Character strengths and virtues: A handbook and classification. Oxford University Press.

Ryff, C. (1989). Happiness is everything, or is it? Explorations on the meaning of psychological well-being. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 57, 1069-1081. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.57.6.1069

Shatte, A., Hutchinson, D. M., & Teague, S. J. (2019). Machine learning in mental health: A scoping review of methods and applications. Psychological Medicine, 49(9), 1426-1448. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291719000151

Snyder, C. R., Lopez, S. J., & Pedrotti, J. T. (2011). Positive Psychology: The Scientific and Practical Explorations of Human Strengths (2a ed.). Sage.

Stavraki, M., Artacho-Mata, E., Bajo, M., Diaz, D. (2023). The dark and light of human nature: Spanish adaptation of the light triad scale and its relationship with psychological well-being. Current Psychology, 42, 26979-26988 https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-022-03732-5

Tkach, C., & Lyubomirsky, S. (2006). How do people pursue happiness? Relating personality, happiness-increasing strategies, and well-being. Journal of Happiness Studies, 7(2), 183-225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10902-005-4754-1

Walker, L. J., & Pitts, R. C. (1998). Naturalistic conceptions of moral maturity. Developmental Psychology, 34(3), 403-419. https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.34.3.403

Yarkoni, T., & Westfall, J. (2017). Choosing prediction over explanation in psychology: Lessons from machine learning. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(6), 1100-1122. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691617693393

Zou, H., & Hastie, T. (2005). Regularization and variable selection via the elastic net. Journal of the Royal Statistical Society: Series B (statistical methodology), 67(2), 301-320. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9868.2005.00503.x

Financiamiento: Realizado mediante el subsidio UBACyT 20020190100045BA "Perfil psicológico del usuario de Internet y de las redes sociales. Análisis de las características de personalidad positivas y negativas desde un enfoque psicoléxico y variables psicológicas mediadoras”.

Disponibilidad de datos: El conjunto de datos que apoya los resultados de este estudio no se encuentra disponible.

Cómo citar: Castro Solano, A., Lupano Perugini, M. L., Caporiccio Trillo, M. A., & Cosentino, A. C. (2024). Validación de un modelo de rasgos positivos y negativos de personalidad como predictores del bienestar psicológico aplicando algoritmos de machine learning. Ciencias Psicológicas, 18(1), e-3286. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v18i1.3286

Contribución de los autores (Taxonomía CRediT): 1. Conceptualización; 2. Curación de datos; 3. Análisis formal; 4. Adquisición de fondos; 5. Investigación; 6. Metodología; 7. Administración de proyecto; 8. Recursos; 9. Software; 10. Supervisión; 11. Validación; 12. Visualización; 13. Redacción: borrador original; 14. Redacción: revisión y edición.

A. C. S. ha contribuido en 1,3,4,6,7,9,10,13,14; M. L. L. P. en 3,6,12,13,14; M. A. C. T. en 13,14; A. C. C. en 1,8,13,14.

Editora científica responsable: Dra. Cecilia Cracco.

10.22235/cp.v18i1.3286

Original Articles

Validation of a model of positive and negative personality traits as predictors of psychological well-being using machine learning algorithms

Validación de un modelo de rasgos positivos y negativos de personalidad como predictores del bienestar psicológico aplicando algoritmos de machine learning

Validação de um modelo de traços de personalidade positivos e negativoscomo preditores do bem-estar psicológico aplicando algoritmos de machine learning

Alejandro Castro Solano1, ORCID 0000-0002-4639-3706

María Laura Lupano Perugini2, ORCID 0000-0001-6090-0762

Micaela Ailén Caporiccio Trillo3, ORCID 0009-0006-8730-4008

Alejandro César Cosentino4, ORCID 0000-0002-7786-5470

1 U Universidad de Buenos Aires; Universidad de Palermo; Conicet, Argentina

2 Universidad de Buenos Aires; Universidad de Palermo; Conicet, Argentina, [email protected]

3 Universidad de Buenos Aires, Argentina

4 Universidad de Buenos Aires; Universidad de Palermo, Argentina

Abstract:

The objective of the study was to verify a predictive model of positive and negative personality traits taking psychological well-being as a criterion through the implementation of machine learning algorithms. 2038 adult subjects (51.9 % women) participated. For data collection were used: Big Five Inventory and Mental Health Continuum-Short Form. In addition, to assess the positive and negative personality traits, the already validated items of the positive (HFM) and negative trait models (BAM), were used jointly. Based on the findings found, it was possible to verify that the predictive efficacy of the tested model of positive and negative traits, derived from a lexical approach, was superior to the predictive capacity of normal personality traits for the prediction of well-being.

Keywords: positive traits; negative traits; personality; psychological well-being; algorithms.

Resumen:

El objetivo de este estudio fue verificar un modelo predictivo de rasgos de personalidad positivos y negativos tomando como criterio el bienestar psicológico mediante la implementación de algoritmos de machine learning. Participaron 2038 sujetos adultos (51.9 % mujeres). Para la recolección de datos se utilizó: Big Five Inventory y Mental Health Continuum-Short Form. Además, para evaluar los rasgos positivos y negativos de personalidad se utilizaron los ítems ya validados de los modelos de rasgos positivos (HFM) y negativos (BAM) de forma conjunta. A partir de los hallazgos encontrados se pudo verificar que la eficacia predictiva del modelo testeado de rasgos positivos y negativos derivados de un enfoque léxico resultó superior a la capacidad predictiva de los rasgos normales de personalidad para la predicción del bienestar.

Palabras clave: rasgos positivos; rasgos negativos; personalidad; bienestar psicológico; algoritmos.

Resumo:

O objetivo do estudo foi verificar um modelo preditivo de traços de personalidade positivos e negativos tendo como critério o bem-estar psicológico por meio da implementação de algoritmos de machine learning. Participaram 2.038 sujeitos adultos (51,9 % mulheres). Para a coleta de dados foram utilizados: Big Five Inventory e Mental Health Continuum-Short Form. Além disso, para avaliar os traços de personalidade positivos e negativos, foram utilizados conjuntamente os itens já validados dos modelos de traços positivos (HFM) e negativos (BAM). Foi possível verificar que a eficácia preditiva do modelo testado de traços positivos e negativos derivados de uma abordagem lexical foi superior à capacidade preditiva de traços normais de personalidade para a predição do bem-estar.

Palavras-chave: traços positivos, traços negativos, personalidade, bem-estar psicológico, algoritmos.

Received: 10/03/2023

Accepted: 30/04/2024

Regarding positive characteristics, there are several models that have explored and studied this topic. Peterson and Seligman's (2004) classification of virtues and strengths falls into the category of theory-driven approaches. The authors proposed a list of 24 character strengths, corresponding to six virtues (Courage, Justice, Humanity, Wisdom, Temperance and Transcendence). More recently, Kaufman et al. (2019) proposed a positive trait model called Light Triad (as opposed to the Dark Triad model —Paulhus & Williams, 2002— which will be further discussed) that includes three traits: Kantianism (traits oriented to treat others as ends in themselves and not as means to an end); Humanism (traits oriented to respect the dignity and value of each individual); Faith in humanity (traits oriented to believe and trust in the goodness of others).

In terms of data-driven approaches, several examples can be cited. On the one hand, Walker and Pitts (1998) sought to analyze conceptions of moral excellence by asking participants to identify attributes that a highly moral person possesses. With these data, they generated a set of moral descriptors. Six clusters of attributes were found: principled idealist, trustworthy and loyal, upright, caring, fair, and finally, confident. Cawley et al. (2000) identified 140 dictionary words that corresponded to moral virtues. With these adjectives and nouns and through factor analysis procedures, the authors found four dimensions of positive virtues: empathetic, orderly, resourceful, and serenity. De Raad and van Oudenhoven (2011), using a psycholexical approach, asked students and psychologists to identify words describing virtues from a series of dictionary terms. From this study emerged a six-factor model of virtues consisting of sociability, achievement, respect, vigor, altruism, and prudence. Another study from the data-driven perspective was conducted by Morales-Vives et al. (2014). The authors identified 209 virtue descriptors. As a result of this procedure, a model of seven dimensions was proposed: self-confidence, reflection, serenity, rectitude, perseverance and effort, compassion, and sociability.

More recently, Cosentino and Castro Solano (2017) explored human positive characteristics, using a psycholexical approach. This type of approach was first employed by Allport and Odbert (1936) and gives a fundamental place to the lexicon, as a basis upon which a classification of human differences can be built (De la Iglesia & Castro Solano, 2020). In a first study, Cosentino y Castro Solano (2017) identified positive characteristics from the point of view of common individuals, with the aim of developing a model of human positive trait factors, socially shared, and that could be replicable in other populations. This research was innovative because previous studies focused only on characteristics associated with moral traits, while talents and abilities had been systematically excluded. This model included these characteristics more broadly, encompassing those related to performance (such as intelligence).

That research resulted in the High Five Model (HFM; Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2017). Five traits were found to be present, to vary in each individual, to be measurable and, moreover, to be increased or reduced by internal and/or external influences. According to the authors, the five HFM factors are: Erudition (a trait associated with thinking solutions, having a desire to learn), Peace (associated with thinking calmly and trusting that things will take their natural course), Joviality (expressed in desires to make others laugh, have fun and amuse others), Honesty (associated with being transparent and having a tendency to tell the truth) and Tenacity (expressed in pursuing goals and seeking to accomplish objectives with effort).

On the other hand, psychology has also been interested in the negative characteristics of human personality. Studies proposing negative trait models have generally used a theory-driven approach. One model that generated great interest is the Dark Triad of Personality (Paulhus & Williams, 2002), which proposes three negatives, but not pathological, personality traits (Machiavellianism, Narcissism and Psychopathy). This model was expanded after its creation to include a new dimension: Sadism (Jones & Paulhus, 2014).

Cosentino y Castro Solano (2023) proposed a model of negative characteristics from the perspective of common individuals, as well as the model of positive traits. Using the psycholexical approach, they found three factors that showed a good data fit. They inductively named this derived model Brutalism, Arrogance, and Malignism (BAM). The three factors are: Brutalism (careless, unstable, rude, unbearable individuals), Arrogance (arrogant, conceited, boastful and pedantic subjects) and Malignism (people who cheat, perform immoral acts, mean, spiteful, etc.). This model is more recent than the model of positive personality traits and is in its validation phase.

Well-being and positive and negative personality models

The study of the link between personality and well-being has been widely studied since personality traits are considered the best known predictors of subjective experiences (Tkach & Lyubomirsky, 2006). Classical research that attempted to explain well-being from personality variables mostly considered normal personality traits (Anglim et al, 2020), mainly from the Five Factor Model (FFM) (Costa & McCrae, 1984). However, in recent years, attention has begun to be paid to the relationship with negative (Blasco-Belled et al., 2024) and positive personality traits (Kaufman et al., 2019).

In the present research well-being was approached from the perspective of Keyes (2002, 2005) since it is one of the most widely used in international studies. The author understands mental health as a continuum called languishing-flourishing, in which individuals can be classified into three groups: languishing, made up of subjects who present difficulties in life, lack of commitment, feeling of emptiness; flourishing, subjects who have an optimal development in their lives; and, finally, moderate mental health, which is made up of subjects who do not fall into the two previous classifications, presenting a moderate level. This model, then, understands health and illness as a continuum, through the presence or absence, in addition to the degree of hedonic (emotional) and eudaemonic (social and psychological well-being) well-being.

Regarding the relationship between well-being and FFM traits, a recent meta-analysis (Anglim et al., 2020) reports that the traits that show the strongest association with both hedonic and eudaemonic well-being are Neuroticism, Extraversion and Conscientiousness.

If the positive personality traits are consider, some studies show that Peterson and Seligman's character strengths model (Peterson & Seligman, 2004; Park et al., 2004) allows predicting life satisfaction, with the strengths of hope, gratitude, curiosity and love being the most associated. Likewise, taking the most recent model of Kaufman et al. (2019), it was found that the three light traits correlate positively with life satisfaction and global well-being (Kaufman et al., 2019; Stavraki et al., 2023).

In relation to the positive trait model analyzed in the present research, the High Five model, previous studies demonstrated that these positive personality factors had incremental validity in predicting psychological well-being (hedonic and eudamonic) over the FFM model (Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2017). In addition, another study showed that these factors were negatively associated with indicators of psychological symptomatology, low risk for medical illness, and pathological personality traits (Castro Solano & Cosentino, 2017). Particularly the traits Peace and Joviality were the traits most strongly associated with low risk of contracting both medical and psychological illnesses. In another study conducted with university students, it was verified that high factors, besides promoting psychological well-being, allowed predicting both adaptation to university life and academic performance of students (Castro Solano & Cosentino, 2019). In this case, Tenacity and Erudition factors were the two positive personality factors most strongly associated with the perception of adjustment to university life.

Regarding antecedents that relate well-being with negative personality traits, studies carried out with the Dark Triad model show that Machiavellianism and Psychopathy are the traits that best predict well-being in a negative way, especially eudaemonic traits (Liu et al., 2021). A recent meta-analysis that included the analysis of 55 studies that worked with negative personality models reported that Antagonism, Disinhibition and Machiavellianism were related to lower levels of well-being. They also showed that age and gender moderated some of these associations (Blasco-Belled et al., 2024).

If the negative trait model analyzed in the present investigation is considered, the BAM model, previous results showed negative associations with life satisfaction and positive associations with psychopathological symptoms (Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2023).

The present research

The purpose of this research is to study a model of positive and negative traits derived from a psycholexical approach for the prediction of both hedonic and eudaemonic psychological well-being. In relation to positive traits the High Five model was considered (Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2017). In relation to negative personality traits, a model of psycholexic characteristics specially designed for local population was taken into account (Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2023).

According to the above, the reasons for choosing these models lie, on the one hand, in the fact that modern personality models (e.g., positive and negative traits) add additional variance for the explanation of psychological well-being over classical personality models (Cosentino & Castro Solano, 2017; Castro Solano & Cosentino, 2019). On the other hand, both models have been developed locally, and from a psycholexical approach, which decreases the risk of falling into an ethic-imposed perspective given that the cultural equivalence of some psychological constructs (e.g., positive traits) is a matter of constant debate (Lopez et al., 2002).

A novelty of this study refers to the use of machine learning algorithms. For some years now these algorithms have become popular in psychology especially for predictive purposes (Yarkoni & Westfall, 2017) as they allow discovering patterns and developing predictive models in a variety of circumstances and application fields of psychology such as psychometrics, experimental psychology, diagnosis, treatment, monitoring and personalized patient care (Dey, 2016; Dhall et al., 2020; Dwyer et al, 2018; Jacobucci & Grimm, 2020; Koul et al, 2018; Lin et al, 2020; Orrù et al, 2020; Shatte et al, 2019). For example, some research using machine learning algorithms allowed identifying personality traits through social media posts (Bleidorn & Hopwood, 2019; Park et al., 2015), or preferred music based on Facebook Likes (Nave et al., 2018). In the clinical setting a recent study, through machine learning algorithms, was able to identify specific predictors of the coping strategies of a large group of patients undergoing cognitive behavioral treatment (Gómez Penedo et al., 2022).

Therefore, the contributions of this research fall, on the one hand, on the theoretical level. Classical research that explained well-being from personality variables considered mostly normal personality traits from the FFM (Anglim et al., 2020). In this case, the main contribution of this study is to present a model that includes other personality variables not commonly analyzed and that have become relevant in the field of personality study: negative traits and positive traits. Using models that consider new personality variables allows to increase the prediction of well-being (greater variance explained compared to traditional models). In addition, it is proposed to test the integrated functioning of positive and negative traits in the same model.

On the other hand, from the methodological point of view, the contribution lies in the inclusion of machine learning algorithms for the explanation of the criterion variables (psychological, emotional and social well-being). The classificatory algorithms help to improve, from a methodological point of view, the prediction by identifying subgroups of specific subjects. For their part, predictive algorithms allow: a) running the analyses with fewer statistical assumptions (e.g. normality, homogeneity of variance), b) considering a large number of variables without affecting the results (high dimensionality), c) estimating the generalizability of the results through cross-validation techniques, a very robust technique in which the data are divided into training and test phases (Dwyer et al, 2018). This last procedure and the incorporation of regularization techniques (hyperparameters in Lasso and Ridge regressions) are far superior to the use of classical linear regressions as they allow improving the accuracy and generalizability of the results (Delgadillo et al., 2020; Zou & Hastie, 2005).

Based on the above, the objectives of this study are: (1) To verify a predictive model of positive and negative personality traits taking into account psychological well-being (personal, emotional and social) as a criterion by implementing machine learning algorithms (Lasso, Ridge and Random Forest regularization); (2) To verify the predictive validity of the personality model of positive and negative traits over the model of normal personality traits, taking psychological well-being (personal, emotional and social) as a criterion by implementing machine learning algorithms (Lasso, Ridge and Random Forest regularization); (3) Verify the accuracy, sensitivity and specificity of the predictive model of positive and negative personality traits to identify people with high and low psychological well-being using machine learning algorithms (support vector machine).

Method

Participants