10.22235/cp.v17i2.3207

Validez del cuestionario Engagement to Academic Tasks Questionnaire en universitarios peruanos

Validity of the Engagement to Academic Tasks Questionnaire in Peruvian college students

Validez do questionário Engagement to Academic Tasks Questionnaire em universitários peruanos

Ricardo Navarro1, ORCID 0000-0002-7069-9780

Francisco Morote2, ORCID 0000-0003-2937-0219

Arlis García3, ORCID 0000-0001-6783-4710

Víctor Bernal4, ORCID 0000-0002-9246-8780

Victoria Teran5, ORCID 0000-0002-5716-3308

1 Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Perú, [email protected]

2 Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Perú

3 Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Perú

4 Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Perú

5 Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Perú

Resumen:

El interés e involucramiento de los estudiantes por su propio aprendizaje en virtualidad durante la pandemia por la COVID-19 ha sido una realidad poco estudiada. La manifestación del involucramiento cognitivo, afectivo y conductual ha sido particularmente diferente durante los últimos años, por lo que contar con instrumentos de medición es necesario para la investigación en la educación. Por ello, se buscó adaptar y validar un instrumento de engagement que permita medir el involucramiento de los estudiantes durante la pandemia. Para ello, se aplicó un cuestionario de engagement a 297 estudiantes universitarios. Los resultados indican que la estructura factorial original del modelo se mantiene al adaptarse a la educación en contexto virtual. Asimismo, se pudo identificar que no existen diferencias en el modelo según el sexo del participante, lo que corrobora invarianza factorial. Se ha podido adaptar y validar un instrumento psicométrico que mide el engagement de los estudiantes en virtualidad.

Palabras clave: engagement académico; análisis factorial confirmatorio; universitarios; educación; aprendizaje.

Abstract:

Students’ interest and involvement of students in their e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic has been a little-studied reality. The manifestation of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral involvement has been particularly different in recent years, so having instruments that allow it to be done is necessary for educational research. Therefore, it was sought to adapt and validate an engagement instrument that allows measuring the involvement of students during the pandemic. For this, an engagement questionnaire was applied to 297 university students. The results indicate that the original factorial structure of the model is maintained when adapting to education in a virtual context. Likewise, it was possible to identify that there were no differences in the model according to the gender of the participant, which corroborates a factorial invariance of the model. That is, it has been possible to adapt and validate a psychometric instrument that measures the engagement of students online.

Keywords: academic engagement; confirmatory factor analysis; college students; education; learning.

Resumo:

O interesse e o envolvimento dos estudantes no seu próprio aprendizado virtual durante a pandemia do covid-19 tem sido uma realidade pouco estudada. A manifestação de envolvimento cognitivo, afetivo e comportamental tem sido particularmente diferente nos últimos anos, por isso contar com instrumentos de mensuração é necessário para a pesquisa em educação. Por conseguinte, procurou-se adaptar e validar um instrumento de engagement que permita medir o envolvimento dos estudantes durante a pandemia. Para isso, foi aplicado um questionário de engagement a 297 estudantes universitários. Os resultados indicam que a estrutura fatorial original do modelo é mantida quando adaptada à educação num contexto virtual. Também foi possível identificar que não havia diferenças no modelo segundo o sexo do participante, o que corrobora a invariância fatorial. Foi possível adaptar e validar um instrumento psicométrico que mede o engagement dos estudantes no contexto virtual.

Palavras-chave: engajamento acadêmico; análise fatorial confirmatória; estudantes universitários; educação; aprendizagem.

Recibido: 03/02/2023

Aceptado: 12/10/2023

El engagement es un constructo que inicialmente ha sido estudiado en contextos laborales (Oriol-Granado et al., 2017). En el ámbito de la educación, el engagement ha generado un creciente interés por parte de educadores e investigadores, y se convirtió en un marco conceptual importante a tener en cuenta (Alrashidi et al., 2016). El engagement académico es entendido como el grado de involucramiento que posee un estudiante para cumplir con sus logros académicos (Gutiérrez et al., 2017). En ese sentido, dicho involucramiento implica la manera en que los estudiantes interactúan con sus actividades académicas (da Rocha et al., 2016; Hew et al., 2016), así como los recursos físicos y psicológicos dedicados a la experiencia educativa (Peña et al., 2017).

El engagement académico ha sido medido a través de diversos instrumentos psicométricos; sin embargo, una desventaja a considerar es que la mayoría han sido adaptaciones de escalas del constructo engagement laboral, el cual proviene del sector organizacional. En ese sentido, una de las pruebas más utilizadas y reconocidas es The Engagement Questionnaire UWES (Schaufeli et al., 2006), adaptada en la región como UWES-S9 (Carmona-Halty et al., 2019; Guerra & Jorquera, 2021; Laureano et al., 2020; Matta, 2021). Dentro de las críticas a este cuestionario se menciona que es una prueba que mide el engagement académico de manera unidimensional y, por consiguiente, no presenta mayor profundidad en su definición (Dominguez-Lara et al., 2020), a diferencia de otras aproximaciones psicométricas del engagement. Por lo tanto, es importante que los investigadores tengan en claro cómo definen el engagement y en qué nivel será medido (Fredricks et al., 2016).

Fredricks et al. (2016) señalan que el engagement académico puede abordar diversos aspectos de la experiencia del estudiante, ya que es un constructo flexible que responde a características contextuales y está sujeto al cambio ambiental (Fredricks et al., 2004). El engagement académico permite predecir los resultados de aprendizaje obtenidos por el alumno y evaluar indirectamente las prácticas realizadas por el docente dentro del aula (Shernoff et al., 2016).

Boekaerts (2016) afirma que el engagement académico tiende a incrementarse en las aulas donde los docentes realizan tareas desafiantes y auténticas con oportunidad de elección. Es por ello que altos niveles de engagement pueden conllevar a mejores resultados académicos en el contexto educativo. Esto es respaldado por Lara et al. (2018), quienes indican que un alto grado de engagement académico conduciría a trayectorias educativas exitosas en el sistema educativo. Por su parte, Bae y Han (2019) agregan que en los sistemas educativos existe la cuestión de cómo mejorar la calidad y los estándares educativos en las escuelas y universidades, y enfatizan que es necesario saber y comprender cómo los estudiantes gastan su tiempo y energía durante sus estudios.

Se considera que el engagement es un constructo bastante amplio (Fredricks et al., 2016; Reschly & Christenson, 2012), en el que se puede distinguir dos enfoques o perspectivas teóricas principales. La primera sostiene que el engagement se compone de tres dimensiones: compromiso cognitivo, compromiso conductual y compromiso emocional-afectivo (Alrashidi et al., 2016; Fredricks et al., 2004). La segunda perspectiva sostiene que el engagement se compone de vigor, dedicación y absorción (Alrashidi et al., 2016; Schaufeli et al., 2002). Esta ambivalencia conceptual genera que se produzcan dificultades al momento de establecer parámetros para la medición del constructo (Jimerson et al., 2003). Debido a ello, se han desarrollado distintos instrumentos que han tratado de medir el engagement y, hasta cierto punto, han coincidido en dimensiones similares.

Un ejemplo de ello es la propuesta de Aspeé et al. (2019), cuya estructura teórica se conforma por tres dimensiones: compromiso orientado al desarrollo académico, compromiso orientado al desarrollo personal-integral y compromiso orientado al desarrollo ciudadano. Estas dimensiones abordan los principios teóricos que componen el engagement y el involucramiento de los estudiantes en actividades académicas.

Por otro lado, Lara et al. (2018) propusieron una estructura tridimensional distinta para la medición de engagement académico, en la que se consideró una dimensión cognitiva, una conductual y una afectiva. Esta propuesta teórica incluye aspectos puntuales de la experiencia de engagement, así como la medición del involucramiento de la persona a nivel conductual, cognitivo y afectivo. Adicionalmente, Zapata et al. (2018) diseñaron y validaron un instrumento que asoció el concepto de engagement a indicadores como calidad de las interacciones, estrategias de aprendizaje, apoyo institucional y aprendizaje colaborativo, entre otros. Por otro lado, Parra y Pérez (2010) desarrollaron un instrumento dirigido a estudiantes de psicología, cuya estructura teórica caracterizó el engagement en tres dimensiones: dedicación, vigor y absorción. Sin embargo, sus hallazgos no fueron empíricamente consistentes con el modelo propuesto, dado que se obtuvo una estructura bifactorial.

A partir de ello, se ha optado por estudiar este constructo desde una perspectiva más específica: desde las tareas y actividades que se abordan en el aula. El engagement vinculado a las tareas y actividades del aula se define como un conjunto de comportamientos favorables por parte de los estudiantes, como el esfuerzo, el entusiasmo y la iniciativa (Jang et al., 2016). De esta manera, Yévenes-Márquez et al. (2022) diseñan el instrumento Engagement to Academic Tasks Questionnaire (Comp-TA) con tres dimensiones: cognitiva, conductual y afectiva. En primer lugar, la dimensión cognitiva se entiende como la inversión y el esfuerzo del estudiante en sus estudios. En segundo lugar, la dimensión conductual refiere a la consistencia del esfuerzo, la asistencia, las tareas y los comportamientos académicos deseados (Fredricks et al., 2004; Shernoff et al., 2016). Finalmente, la dimensión afectiva corresponde al vínculo afectivo y emocional, y el entendimiento de cómo los estudiantes enfrentan las actividades académicas (Fredricks et al., 2004). Shernoff et al. (2016) añaden que esta dimensión se refiere a las emociones y afectos de los estudiantes frente a sus tareas en el aula. Si bien el cuestionario de Yévenes-Márquez et al. (2022) fue desarrollado para el ámbito escolar, también es replicable en la educación superior y posee buenas propiedades psicométricas.

Así, el Comp-TA fue elaborado con base en 3 instrumentos: Compromiso escolar (School Engagement; Lara et al., 2018), Involucramiento Académico (Rigo & Donolo, 2018) y la Escala de Compromiso hacia las Tareas Escolares (Peña et al., 2017). El primer instrumento fue validado en estudiantes adolescentes y se compuso de 3 factores con cargas de fiabilidad adecuados (sus alpha oscilan entre .83 y .87). Asimismo, el modelo presentó indicadores de ajuste adecuados (RMSEA = .05; CFI = .94; TLI = .93). El Involucramiento Académico fue validado en estudiantes universitarios y se compuso de 6 factores: apego a la universidad, atención en clase, participación activa, dedicación, focalización en la tarea, integración social. Se corroboró la consistencia interna del instrumento con el coeficiente de alfa de Cronbach (.896) y theta (.91) (Peña et al., 2017). Por último, la Escala de Compromiso hacia las Tareas Académicas se adaptó y validó en estudiantes de nivel primario; esta se subdividió en las 3 dimensiones con coeficientes de confiabilidad adecuados (sus alpha oscilan entre .70 y .76) e indicadores de ajuste adecuados del modelo con GFI = .92; CFI = .93 y RMSEA = .04 (Rigo & Donolo, 2018).

Por otro lado, el género ha demostrado estar relacionado con el engagement académico (Ayub et al., 2017; Dominguez-Lara et al., 2021). La literatura sugiere que las mujeres exhiben niveles más elevados de engagement (Carvajal & Carranza, 2022; Hsieh & Yu, 2023). Esta diferencia podría tener un origen cultural, que se refleja en las tareas académicas (Maluenda et al., 2022; Maunula et al., 2023). Sin embargo, es esencial enfatizar que la mayoría de estos estudios no han tenido en cuenta las implicaciones de la invarianza con el género al realizar análisis de validez (Barghaus et al., 2023). En consecuencia, resulta crítico llevar a cabo un análisis de invarianza como un procedimiento que podría favorecer una medición más objetiva y exenta de sesgos.

Medir el engagement académico en estudiantes universitarios se hace relevante para poder identificar hasta qué punto la experiencia educativa impacta en la formación de futuros profesionales. Por consiguiente, el objetivo general de este estudio fue evaluar las propiedades psicométricas de una adaptación y extensión del cuestionario Comp-TA (Yévenes-Márquez et al., 2022) con una muestra de estudiantes universitarios de Lima Metropolitana. Como objetivo específico, se propuso realizar un análisis de invarianza según el sexo de los participantes.

Método

Participantes

La muestra estuvo conformada por 297 estudiantes universitarios del área metropolitana de Lima, Perú. Las mujeres constituyeron el 58.2 % de la muestra y los hombres el 41.8 %. Las edades de los participantes oscilaron entre los 18 y 32 años (M = 20.87; DE = 2.29). Los participantes se encontraban entre segundo y doceavo ciclo (M = 6; DE = 2.65). Como criterios de inclusión se consideró que todos los participantes fueran mayores de edad, hayan llevado cursos virtuales durante el ciclo académico 2021-2022 y estuvieran matriculados en la universidad.

Para participar en la investigación, los encuestados leyeron un consentimiento informado en el cual se indicó la importancia y motivo del estudio, así como los requerimientos de este. En el marco de la protección de su integridad, se especificó que la participación era voluntaria, anónima y confidencial. Asimismo, se les aseguró que podrían abandonar la investigación en cualquier momento, sin que esto les generase perjuicio alguno.

Medida

El Engagement to Academic Tasks Questionnaire (Comp-TA) fue elaborado por Yévenes-Márquez et al. (2022) y consta de 15 ítems que subyacen a tres factores del engagement académico: conductual (7 ítems), cognitivo (4 ítems) y afectivo (4 ítems). El cuestionario utiliza un formato de respuesta Likert del 1 al 7, en el que 1 es Totalmente de acuerdo, 2: Algo en desacuerdo, 3: En desacuerdo, 4: Ni de acuerdo ni en desacuerdo, 5: De acuerdo, 6: Bastante de acuerdo y 7: Totalmente en acuerdo. En cuanto a la validez del instrumento, en el análisis factorial exploratorio se utilizó el método de extracción de mínimos cuadrados no ponderados y el método de rotación oblicua Promin. Así, la prueba de esfericidad de Barlett fue significativa, obtuvo un KMO = 0.86, lo cual evidenció que la matriz de correlación era adecuada para análisis factorial. Se extrajo una solución de tres factores que explicaron un total del 57 % de la varianza, lo que se considera un porcentaje adecuado (Pérez & Medrano, 2010). Con respecto a las propiedades psicométricas de la escala, se reportaron índices de ajuste del análisis factorial confirmatorio (CFI = .92; TLI = .90; RMSEA = .07) que indican que el instrumento tiene una validez de estructura interna satisfactoria, con tres dimensiones (Kline, 2016).

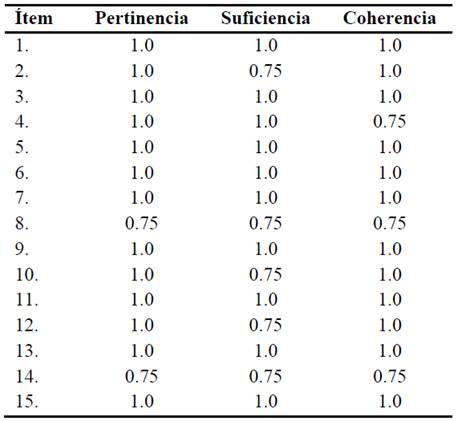

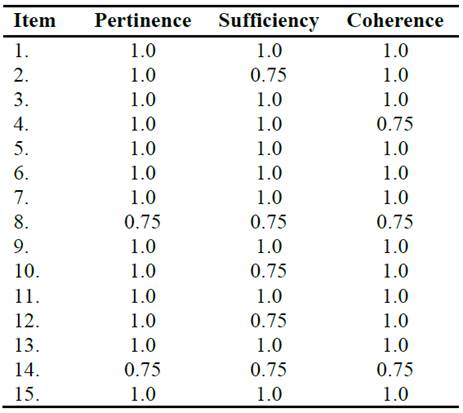

Asimismo, se utilizó un protocolo para jueces, se pidió a especialistas en el tema que evalúen los ítems del instrumento según tres criterios: pertinencia, suficiencia y coherencia. La pertinencia refiere a si el ítem corresponde o no a la dimensión asignada. La suficiencia, a si el ítem es adecuado para medir el efecto o concepto evaluado. Y finalmente, la coherencia alude a si el ítem es coherente en términos de redacción.

Procedimiento

El presente estudio presenta un diseño de investigación instrumental, que busca validar un instrumento mediante el uso de análisis de expertos y análisis psicométricos. Para realizar la adaptación del Comp-TA a una población de universitarios limeños, se solicitó el permiso de los autores del instrumento original para su uso y aplicación. Una vez adquirido dicho permiso, los autores de la presente investigación realizaron la traducción de los ítems al español. Luego, el cuestionario fue sometido a un proceso de validación de contenido con cuatro jueces. Posteriormente, se creó el cuestionario en un Google Forms, en el cual se incluyó el consentimiento informado y la ficha sociodemográfica. De esta manera, se realizó un piloto online del cuestionario con cuatro participantes, en el cual se recogieron comentarios y observaciones. Por último, se aplicó el instrumento de manera virtual.

Análisis de datos

Para el presente estudio, se utilizó el software RStudio en la versión 2022.12.0. Primero se realizaron los análisis descriptivos y el criterio de Aiken. Además, se presentó la confiabilidad interna de las tres dimensiones y el instrumento general con los coeficientes de alfa de Cronbach y el omega de McDonald. Con respecto al objetivo principal, se realizó un análisis factorial confirmatorio (CFA) para identificar si la estructura del modelo original se mantiene con un análisis de este tipo. En ese sentido, se considera revisar el error cuadrático medio de aproximación (RMSEA), el residuo cuadrático medio estandarizado (SRMR), el índice de ajuste comparativo (CFI) y el Índice Tuker-Lewis (TLI). Se debe mencionar que los valores aceptables de estos factores son los siguientes: RMSEA < .06; SRMR < .08; CFI > .95; TLI > .95. Para los análisis de invarianza (métrica y escalar), se parte de los puntos de corte propuesto por Rutkowski y Svetina (2014), que señalan que los valores de los índices de ajuste de la invarianza escalar y métrica deberían ser de la siguiente manera: ΔCFI > -.010; ΔRMSEA < .015.

Resultados

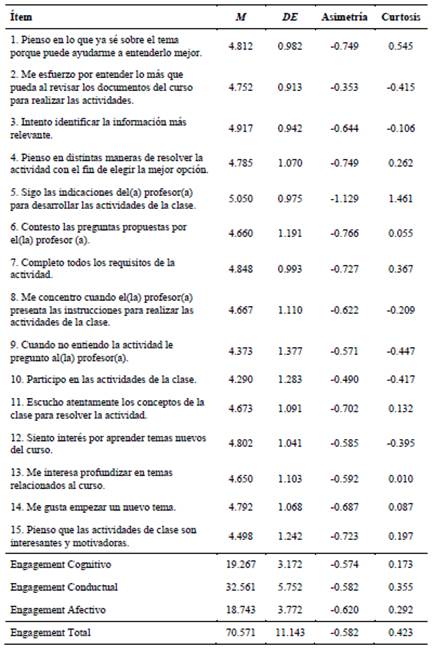

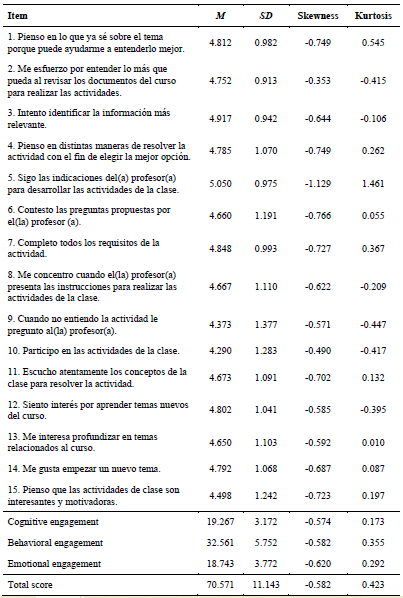

En primer lugar, se reportaron los análisis descriptivos del instrumento por ítem, dimensión y el puntaje total (Tabla 1). En cuanto a la validez de contenido, se reportaron los resultados obtenidos en cada ítem (Tabla 2).

Posteriormente, se realizó un CFA para comprobar que la estructura original de la escala de tres dimensiones se replica en la presente muestra. De esta manera, se verificó el Test de Mardia para comprobar el supuesto para ecuaciones estructurales sobre que las variables observadas sigan, en conjunto, una distribución normal multivariante (Kline, 2016). Al respecto, la prueba de Mardia reveló índices de asimetría (ˆγ1 = 1747.64; p < .05) y de curtosis multivariantes (ˆγ2 = 28.32; p < .05) del conjunto de variables del cuestionario, lo cual indicó que los datos no seguían una distribución normal multivariante.

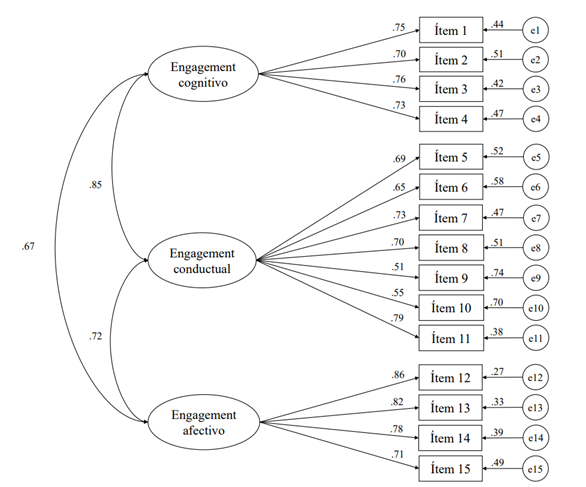

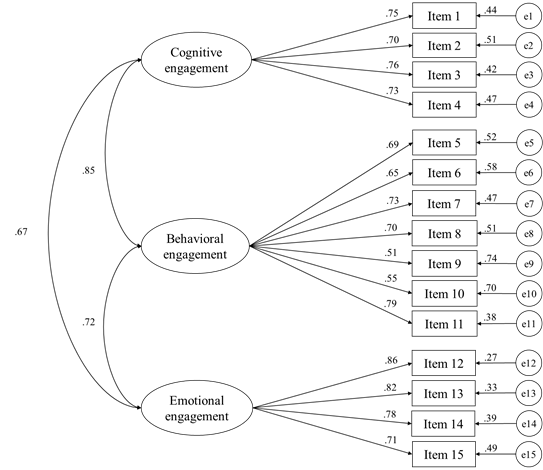

Se realizó un CFA con el método de estimación de máxima verosimilitud y la corrección de Satorra y Bentler (2001), debido a que los datos no cumplen con el supuesto de normalidad multivariada. Este análisis permitió corroborar la estructura factorial de tres dimensiones de la escala adaptada que obtuvo buenos índices de ajuste (χ2(gl) = 202.435(87); p < .001; S-Bχ2 = 1.383; CFI = .924; TLI = .908; RMSEA = .067 (IC = .057-.077); SRMR = .056) en la dimensión de engagement cognitivo (conformada por los ítems 1, 2, 3, 4), la dimensión de engagement conductual (ítems 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10 y 11), la dimensión de engagement afectivo (los ítems 12, 13, 14 y 15). Las cargas factoriales fueron significativas (p < .001) y oscilaron entre .510 y .855. (Figura 1).

Tabla 1: Datos descriptivos de los ítems, dimensiones y el total de la escala de Comp-TA

Tabla 2: Resultados de la validez de jueces

|

Figura 1: Modelado CFA de la Comp-TA

Posteriormente, se examinó la confiabilidad por consistencia interna mediante el coeficiente alfa y omega de los factores del Comp-TA. Se identificó que la escala presenta una confiabilidad general con un omega total (ω) = .93. Por un lado, el factor engagement cognitivo presentó una confiabilidad elevada, dado que α = .82 y ω = .84. Asimismo, el factor engagement conductual presentó una confiabilidad alta de α = .84 y ω = .89. Por último, el factor engagement afectivo también obtuvo un coeficiente alto de α = .87 y ω = .89.

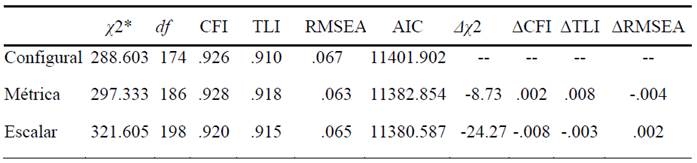

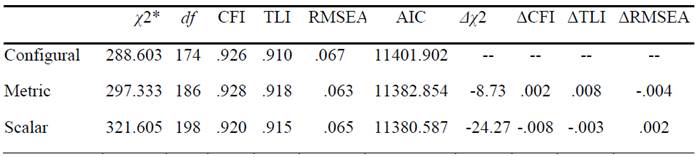

El siguiente paso fue revisar las propiedades de invarianza del instrumento según el sexo reportado de los participantes (Tabla 3). La invariancia se puede analizar en tres niveles: métrico (se centra en los elementos y la carga factorial de las variables observadas), escalar (repasa las variables latentes o factores) y configural (verifica si la estructura factorial es similar entre los grupos; Milfont & Fischer, 2010).

Siguiendo los criterios propuestos por Rutkowski y Svetina (2014), los resultados mostraron que la escala Engagement to Academic Tasks Questionnaire (Comp-TA) presentó una fuerte invarianza según el sexo del participante tanto en la varianza métrica como en la escalar. Estos resultados indican que no existe una variabilidad por el sexo de los participantes y que la estructura del modelo se mantiene entre estos grupos.

Tabla 3: Invarianza del modelo por sexo

*Todos los χ2 tienen un p < .001

Discusión

El objetivo de este estudio fue adaptar la escala Comp-TA al contexto peruano, se recolectó evidencia sobre la validez y la confiabilidad de la escala con estudiantes universitarios. Los resultados indican que el cuestionario adaptado tiene propiedades psicométricas para ser considerado válido y confiable.

En primer lugar, se observa que se encontraron índices de ajuste adecuados. Si bien existe literatura que difiere en los puntos de corte, la evidencia recolectada se encuentra dentro de los parámetros utilizados tanto por Hu y Bentler (1999), Schreiber et al. (2006) y Rutkowski y Svetina (2014). Asimismo, estos resultados son similares a los procesos de validez y confiabilidad realizados por Lara et al. (2018) y Aspeé et al. (2019). Un aspecto importante a tener en cuenta es que los índices de ajuste del análisis de invarianza métrica y escalar cumplen con los parámetros propuestos por Rutkowski y Svetina (2014). Este análisis es importante, pues brinda evidencia de que no existen diferencias significativas relevantes en las cargas factoriales de la muestra. En ese sentido, los resultados señalan que los ítems no responden de manera diferente entre los grupos (sexo), lo que implica que la fuerza de las relaciones entre los ítems de la escala y la construcción del modelo es igual en todos los grupos (Milfont & Fischer, 2010).

Un aspecto importante a resaltar es que no existen muchos estudios que hayan realizado el análisis de invarianza al validar instrumentos psicométricos que miden el engagement, por lo que este estudio brinda evidencia relevante sobre la estructura factorial original. Asimismo, mantener la invariabilidad del modelo según el sexo del participante es relevante para la medición del engagement, pues, debido a variables culturales, podrían existir diferencias entre los grupos. Al no encontrar estas diferencias, se puede concluir que el modelo no se encuentra afectado por el sexo del participante.

Por otro lado, los resultados obtenidos apoyan la estructura factorial original, se identificó un modelo tridimensional similar al propuesto por Yévenes-Márquez et al. (2022), Fredricks et al. (2004) y Tannoubi et al. (2023). Estos resultados reafirman la importancia de estudiar el engagement teniendo en cuenta la interacción de estas dimensiones, pues permiten estudiar el grado de intensidad y la duración que una conducta tendrá en el contexto académico (Freiberg-Hoffmann et al., 2022).

En ese sentido, Yévenes-Márquez et al. (2022) señalan que el engagement en el salón de clase tiene que incluir experiencias afectivas, cognitivas y conductuales que interactúen al enfrentar una actividad académica. Eso implica que las tres dimensiones puedan mantener una relación coherente entre ellas, lo que ha sido evidenciado en el modelo presentado.

Con respecto a la invariancia por sexo, al probar la invariancia configural, métrica y escalar, se encontró que no existe variabilidad con base en el sexo de los participantes. Este análisis prueba si diferentes grupos responden a los ítems de la misma manera, lo que significa que la fuerza de las relaciones entre los ítems de la escala y la construcción subyacente es la misma en todos los grupos (Hirschfeld & von Brachel, 2014; Milfont & Fisher, 2010). En este caso, se pueden comparar las calificaciones de hombres y mujeres, y las diferencias observadas en los elementos del Comp-TA pueden indicar diferencias grupales de engagement académico.

Asimismo, en términos de confiabilidad, los coeficientes de confiabilidad, alfa y omega, obtenidos en las tres dimensiones del Comp-TA fueron superiores al .70, lo cual indica niveles adecuados de consistencia interna de la escala en la muestra estudiada (Hair et al., 1998; Ventura-León & Caycho-Rodríguez, 2017). En ese sentido, los resultados observados son similares al estudio de Yévenes-Márquez et al. (2022) y son suficientes para realizar futuros estudios de investigación con la escala validada.

Por otra parte, entre las fortalezas que presenta el Comp-TA, se resalta que puede ser aplicada de manera fácil y rápida con tres dimensiones que tienen una funcionalidad práctica dentro del salón de clase: afectiva, conductuales y cognitivas. En ese sentido, se puede identificar qué dimensión debe ser abordada por el docente. Asimismo, el uso del Comp-TA permite identificar si el engagement de los estudiantes puede estar siendo afectado positivamente por alguna intervención educativa innovadora.

Con respecto a las limitaciones de este estudio, es importante señalar que en esta investigación no se midieron otros constructos relacionados con el engagement académico. Futuras investigaciones podrían evaluar otras variables psicológicas de la red nomológica de engagement académico con la finalidad de obtener evidencia de validez convergente, discriminante o de criterio. Además, en cuanto a la muestra en estudio, es importante resaltar que los participantes fueron estudiantes de una universidad de Lima, los cuales, por sus características particulares, no representan suficientemente la realidad de estudiantes universitarios del resto del país. En ese sentido, estos resultados no pueden generalizarse al resto de universitarios peruanos. Por lo tanto, se sugiere que en el futuro se pueda extender el estudio de las propiedades psicométricas del Comp-TA a universitarios de otras partes del Perú.

A pesar de las limitaciones, el Comp-TA en su versión en español aplicado a estudiantes universitarios de Lima se considera una herramienta consistente y adecuada para medir el engagement académico en esta población.

Referencias:

Alrashidi, O., Phan, H. P., & Ngu, B. H. (2016). Academic engagement: an overview of its definitions, dimensions, and major conceptualizations. International Education Studies, 9(12), 41-52. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v9n12p41

Aspeé, J., González, J., & Cavieres, E. (2019). Instrumento para medir el compromiso estudiantil integrando el desarrollo ciudadano: una propuesta desde Latinoamérica. Revista Complutense de Educación, 30(2), 399-421. https://doi.org/10.5209/RCED.57518

Ayub, A., Yunus, A., Mahmud, R., Salim, N. & Sulaiman, T. (2017). Differences in students’ mathematics engagement between gender and between rural and urban schools. AIP Conference Proceedings, 1(1795), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4972169

Bae, Y., & Han, S. (2019). Academic Engagement and Learning Outcomes of the Student Experience in the Research University: Construct Validation of the Instrument. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 19(3), 49-64. https://doi.org/10.12738/estp.2019.3.004

Barghaus, K., Henderson, C., Fantuzzo, J., Brumley, B., Coe, K., LeBoeuf, W., & Weiss, E. (2023). Classroom Engagement Scale: validation of a teacher-report assessment used to scale in the kindergarten report card of a large urban school district. Early Education and Development, 34(1), 306-328. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2021.1985047

Boekaerts, M. (2016). Engagement as an inherent aspect of the learning process. Learning and Instruction, 43, 76-83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.02.001

Carmona-Halty, M. A., Schaufeli, W. B., & Salanova, M. (2019). The Utrecht Work Engagement Scale for Students (UWES–9S): Factorial validity, reliability, and measurement invariance in a Chilean sample of undergraduate university students. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1-5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01017

Carvajal, C., & Carranza, R. (2022). Propriedades psicométricas da escala de envolvimento acadêmico em estudantes universitários bolivianos. Horizontes Revista de Investigación en Ciencias de la Educación, 6(26), 2254-2264. https://doi.org/10.33996/revistahorizontes.v6i26.489

Da Rocha Seixas, L., Gomes, A. S., & de Melo Filho, I. J. (2016). Effectiveness of gamification in the engagement of students. Computers in Human Behavior, 58, 48-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.021

Dominguez-Lara, S., Sánchez-Villena, A. R., & Fernández-Arata, M. (2020). Propiedades psicométricas de la UWES-9S en estudiantes universitarios peruanos. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 23(2), 7-23. https://doi.org/10.14718/acp.2020.23.2.2

Dominguez-Lara, S., Fernández-Arata, M., & Seperak-Viera, R. (2021). Análisis psicométrico de una medida ultra-breve para el engagement académico: UWES-3S. Revista Argentina de Ciencias del Comportamiento, 13(1), 25-37. https://doi.org/10.32348/1852.4206.v13.n1.27780

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School Engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59-109. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059

Fredricks, J. A., Filsecker, M., & Lawson, M. A. (2016). Student engagement, context, and adjustment: Addressing definitional, measurement, and methodological issues. Learning and Instruction, 43, 1-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.02.002

Comp-TA -Hoffmann, A., Romero-Medina, A., Curione, K., & Marôco, J. (2022). Adaptación y validación transcultural al español del University Student Engagement Inventory. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 54, 187-195. https://doi.org/10.14349/rlp.2022.v54.21

Guerra, F., & Jorquera, R. (2021). Análisis psicométrico de la Utrecht Work Engagement Scale en las versiones UWES-17S y UWES-9S en universitarios chilenos. Revista Digital de Investigación en Docencia Universitaria, 15(2), 1-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.19083/ridu.2021.1542

Gutiérrez, M., Tomás, J. M., Barrica, J. M., & Romero, I. (2017). Influencia del clima motivacional en clase sobre el compromiso escolar de los adolescentes y su logro académico. Enseñanza & Teaching: Revista Interuniversitaria de Didáctica, 35(1), 21-37. https://doi.org/10.14201/et20173512137

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black W. C. (1998). Multivariate Data Analysis (5ª ed.). Prentice Hall.

Hew, K. F., Huang, B., Chu, K. W. S., & Chiu, D. K. (2016). Engaging Asian students through game mechanics: Findings from two experiment studies. Computers & Education, 92, 221-236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.10.010

Hirschfeld, G., & von Brachel, R. (2014). Improving multiple-group confirmatory factor analysis in R–A tutorial in measurement invariance with continuous and ordinal indicators. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 19(7), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.7275/qazy-2946

Hsieh, T. L., & Yu, P. (2023). Exploring achievement motivation, student engagement, and learning outcomes for STEM college students in Taiwan through the lenses of gender differences and multiple pathways. Research in Science & Technological Education, 41(3), 1072-1087.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Jang, H., Kim, E. J., & Reeve, J. (2016). Why students become more engaged or more disengaged during the semester: A self-determination theory dual-process model. Learning and Instruction, 43, 27-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.01.002

Jimerson, S. R., Campos, E., & Greif, J. L. (2003). Toward an understanding of definitions and measures of school engagement and related terms. Contemporary School Psychologist, 8(1), 7-27. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03340893

Kline, R. (2016). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. The Guilford Press.

Lara, L., Saracostti, M., Navarro, J. J., De-Toro, X., Miranda-Zapata, E., Trigger, J. M., & Fuster, J. (2018). Compromiso escolar: Desarrollo y validación de un instrumento. Revista Mexicana de Psicología, 35(1), 52-62.

Laureano, S. E., Ortiz, D. E., & Valle, L. M. (2020). Validación de la Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES) en personal docente de pre-grado de universidades privadas en Lima Metropolitana [Tesis de Maestría, Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola]. Repositorio Institucional - USIL. https://repositorio.usil.edu.pe/handle/usil/10452

Maluenda, J., Berríos, J., Infante, V., & Lobos, K. (2022). Perceived social support and engagement in first-year students: the mediating role of belonging during COVID-19. Sustainability, 15(1), 597. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010597

Matta, E. P. (2021). Engagement académico y empatía en estudiantes de la Escuela Profesional de Medicina Humana de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos [Tesis de Doctorado, Universidad Nacional de Educación Enrique Guzmán y Valle]. Repositorio Institucional de la Universidad Nacional de Educación. http://repositorio.une.edu.pe/handle/20.500.14039/5685

Maunula, M., Maunumäki, M., Marôco, J., & Harju-Luukkainen, H. (2023). Developing students well-being and engagement in higher education during COVID-19: A case study of web-based learning in Finland. Sustainability, 15(4), 3838. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043838

Milfont, T. L., & Fischer, R. (2010). Testing measurement invariance across groups: Applications in cross-cultural research. International Journal of Psychological Research, 3(1), 111-121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-007-9143-x

Navarro, R., López, R., & Caycho, G. (2021). Retos de los docentes universitarios para el diseño de experiencias virtuales educativas en pandemia. Desde el Sur, 13(2), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.21142/DES-1302-2021-0017

Oriol-Granado, X., Mendoza-Lira, M., Covarrubias-Apablaza, C. G., & Molina-López, V. M. (2017). Emociones positivas, apoyo a la autonomía y rendimiento de estudiantes universitarios: el papel mediador del compromiso académico y la autoeficacia. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 22(1), 45-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1136-1034(17)30043-6

Parra, P., & Pérez, C. (2010). Propiedades psicométricas de la escala de compromiso académico, UWES-S (versión abreviada), en estudiantes de psicología. Revista de Educación en Ciencias de la Salud, 7(2), 128-133.

Peña, G., Cañoto, Y., & Angelucci, L. (2017). Involucramiento académico: una escala. Páginas de Educación, 10(1), 114-136. http://dx.doi.org/10.22235/pe.v10i1.1361

Pérez, E. R., & Medrano, L. A. (2010). Análisis factorial exploratorio: bases conceptuales y metodológicas. Revista Argentina de Ciencias del Comportamiento, 2(1), 58-66. https://doi.org/10.32348/1852.4206.v2.n1.15924

Reschly, A. L., & Christenson, S. L. (2012). Jingle, Jangle, and Conceptual Haziness: Evolution and Future Directions of the Engagement Construct. En S. Christenson, A. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Student Engagement (pp. 3-19). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7_1

Rigo, D. Y., & Donolo, D. (2018). Construcción y validación de la Escala de compromiso hacia las tareas escolares en las clases para los estudiantes del nivel primario de educación. Psicoespacios: Revista virtual de la Institución Universitaria de Envigado, 12(21), 3-22. https://doi.org/10.25057/issn.2145-2776

Rutkowski, L., & Svetina, D. (2014). Assessing the Hypothesis of Measurement Invariance in the Context of Large-Scale International Surveys. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 74(1), 31-57. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0013164413498257

Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. M. (2001). A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika, 66(4), 507-514. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02296192

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The Measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: a cross–national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701-716. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164405282471

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: a two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71-92. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1015630930326

Schreiber, J. B., Nora, A., Stage, F. K., Barlow, E. A., & King, J. (2006). Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. The Journal of Educational Research, 99(6), 323-338. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338

Shernoff, D. J., Kelly, S., Tonks, S. M., Anderson, B., Cavanagh, R. F., Sinha, S., & Abdi, B. (2016). Student engagement as a function of environmental complexity in high school classrooms. Learning and Instruction, 43, 52-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2015.12.003

Tannoubi, A., Quansah, F., Hagan, J., Srem-Sai, M., Bonsaksen, T., Chalghaf, N., Boussayala, G., Azaiez, C., Snani, C., & Azaiez, F. (2023). Adaptation and Validation of the Arabic Version of the University Student Engagement Inventory (A-USEI) among Sport and Physical Education Students. Psych, 5(2), 320-335. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych5020022

Ventura-León, J. L., & Caycho-Rodríguez, T. (2017). El coeficiente Omega: un método alternativo para la estimación de la confiabilidad. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 15(1), 625-627.

Vilela, P., Sánchez, J., & Chau, C. (2021). Desafíos de la educación superior en el Perú durante la pandemia por la covid-19. Desde el Sur, 13(2), 1-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.21142/des-1302-2021-0016

Yévenes-Márquez, J. N., Badilla-Quintana, M. G., & Sandoval-Henríquez, F. J. (2022). Measuring engagement to academic tasks: design and validation of the Comp-TA Questionnaire. Education Research International, 2022, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/4783994

Zapata, G., Leihy, P., & Theurillat, D. (2018). Compromiso estudiantil en educación superior: adaptación y validación de un cuestionario de evaluación en universidades chilenas. Calidad en la educación, (48), 204-250. http://dx.doi.org/10.31619/caledu.n48.482

Disponibilidad de datos: El conjunto de datos que apoya los resultados de este estudio no se encuentra disponible.

Financiamiento: Los datos analizados en este artículo fueron recogidos como parte de un proyecto de investigación financiado por la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, en el marco del Concurso Anual de Proyectos de Investigación (CAP).

Cómo citar: Navarro, R., Morote, F., García, A., Bernal, V., & Teran, V. (2023). Validez del cuestionario Engagement to Academic Tasks Questionnaire en universitarios peruanos. Ciencias Psicológicas, 17(2), e-3207. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i2.3207

Contribución de los autores: a) Concepción y diseño del trabajo; b) Adquisición de datos; c) Análisis e interpretación de datos; d) Redacción del manuscrito; e) revisión crítica del manuscrito.

R. N. ha contribuido con a, b, c, d, e; F. M. con a, b, c, d, e; A. G. con a, b, c, d, e; V. B. con a, b, c, d, e; V. T. con a, d, e.

Editora científica responsable: Dra. Cecilia Cracco.

10.22235/cp.v17i2.3207

Original Articles

Validity of the Engagement to Academic Tasks Questionnaire in Peruvian college students

Validez del cuestionario Engagement to Academic Tasks Questionnaire en universitarios peruanos

Validez do questionário Engagement to Academic Tasks Questionnaire em universitários peruanos

Ricardo Navarro1, ORCID 0000-0002-7069-9780

Francisco Morote2, ORCID 0000-0003-2937-0219

Arlis García3, ORCID 0000-0001-6783-4710

Víctor Bernal4, ORCID 0000-0002-9246-8780

Victoria Teran5, ORCID 0000-0002-5716-3308

1 Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Peru, [email protected]

2 Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Peru

3 Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Peru

4 Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Peru

5 Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, Peru

Abstract:

Students’ interest and involvement of students in their e-learning during the COVID-19 pandemic has been a little-studied reality. The manifestation of cognitive, emotional, and behavioral involvement has been particularly different in recent years, so having instruments that allow it to be done is necessary for educational research. Therefore, it was sought to adapt and validate an engagement instrument that allows measuring the involvement of students during the pandemic. For this, an engagement questionnaire was applied to 297 university students. The results indicate that the original factorial structure of the model is maintained when adapting to education in a virtual context. Likewise, it was possible to identify that there were no differences in the model according to the gender of the participant, which corroborates a factorial invariance of the model. That is, it has been possible to adapt and validate a psychometric instrument that measures the engagement of students online.

Keywords: academic engagement; confirmatory factor analysis; college students; education; learning.

Resumen:

El interés e involucramiento de los estudiantes por su propio aprendizaje en virtualidad durante la pandemia por la COVID-19 ha sido una realidad poco estudiada. La manifestación del involucramiento cognitivo, afectivo y conductual ha sido particularmente diferente durante los últimos años, por lo que contar con instrumentos de medición es necesario para la investigación en la educación. Por ello, se buscó adaptar y validar un instrumento de engagement que permita medir el involucramiento de los estudiantes durante la pandemia. Para ello, se aplicó un cuestionario de engagement a 297 estudiantes universitarios. Los resultados indican que la estructura factorial original del modelo se mantiene al adaptarse a la educación en contexto virtual. Asimismo, se pudo identificar que no existen diferencias en el modelo según el sexo del participante, lo que corrobora invarianza factorial. Se ha podido adaptar y validar un instrumento psicométrico que mide el engagement de los estudiantes en virtualidad.

Palabras clave: engagement académico; análisis factorial confirmatorio; universitarios; educación; aprendizaje.

Resumo:

O interesse e o envolvimento dos estudantes no seu próprio aprendizado virtual durante a pandemia do covid-19 tem sido uma realidade pouco estudada. A manifestação de envolvimento cognitivo, afetivo e comportamental tem sido particularmente diferente nos últimos anos, por isso contar com instrumentos de mensuração é necessário para a pesquisa em educação. Por conseguinte, procurou-se adaptar e validar um instrumento de engagement que permita medir o envolvimento dos estudantes durante a pandemia. Para isso, foi aplicado um questionário de engagement a 297 estudantes universitários. Os resultados indicam que a estrutura fatorial original do modelo é mantida quando adaptada à educação num contexto virtual. Também foi possível identificar que não havia diferenças no modelo segundo o sexo do participante, o que corrobora a invariância fatorial. Foi possível adaptar e validar um instrumento psicométrico que mede o engagement dos estudantes no contexto virtual.

Palavras-chave: engajamento acadêmico; análise fatorial confirmatória; estudantes universitários; educação; aprendizagem.

Received: 03/02/2023

Accepted: 12/10/2023

Due to the COVID-19 pandemic, the educational experience underwent several changes (Navarro et al., 2021; Vilela et al., 2021). This caused the students to experience virtual and hybrid education, modalities with which they were not familiar. Therefore, it is relevant to analyze the impact of virtual education on students’ learning and motivation (Navarro et al., 2021). One of the variables that could be important is engagement and its measurement in the academic context.

Engagement is a construct that has been studied in work-related contexts (Oriol-Granado et al., 2017). In the field of education, engagement has generated growing interest from educators and researchers, becoming an important conceptual framework to consider (Alrashidi et al., 2016). Academic engagement is understood as the degree of involvement that students have in achieving their academic goals (Gutiérrez et al., 2017). Thus, such involvement comprises how students interact with their academic activities (da Rocha et al., 2016; Hew et al., 2016), as well as the physical and psychological resources dedicated to the educational experience (Peña et al., 2017).

Academic engagement has been measured through various psychometric instruments; however, one disadvantage to consider is that most of them have been adaptations of scales from the work-related engagement construct. In this regard, one of the most widely used and recognized tests is The Engagement Questionnaire UWES (Schaufeli et al., 2006), which has been adapted in the region as UWES-S9 (Carmona-Halty et al., 2019; Guerra & Jorquera, 2021; Laureano et al., 2020; Matta, 2021). Among the criticisms of this questionnaire is that it measures academic engagement in a one-dimensional manner and, therefore, lacks depth in its definition (Dominguez-Lara et al., 2020), unlike other psychometric approaches to engagement. Therefore, researchers need to have a clear understanding of how they define engagement and at what level it will be measured (Fredricks et al., 2016).

Fredricks et al. (2016) pointed out that academic engagement can address various aspects of the student’s experience, being a flexible construct that responds to contextual characteristics and is subject to environmental change (Fredricks et al., 2004). Academic engagement allows for predicting the learning outcomes achieved by the student and -indirectly- evaluating the practices carried out by the teacher in the classroom (Shernoff et al., 2016).

Boekaerts (2016) asserts that academic engagement tends to increase when teachers assign challenging tasks, that present opportunities for choice. Therefore, high levels of engagement can lead to better academic outcomes in the educational context. This is supported by Lara et al. (2018), who indicate that a high degree of academic engagement would lead to successful academic outcomes within the educational system. In addition, Bae and Han (2019) note that in educational systems, there is a need to improve the quality and educational standards in schools and universities, emphasizing the necessity to know and understand how students spend their time and energy during their studies.

Engagement is considered a rather broad construct (Fredricks et al., 2016; Reschly & Christenson, 2012), in which two main theoretical perspectives or approaches can be distinguished. The first implies that engagement consists of three dimensions: cognitive engagement, behavioral engagement, and emotional-affective engagement (Alrashidi et al., 2016; Fredricks et al., 2004). The second perspective argues that engagement consists of vigor, dedication, and absorption (Alrashidi et al., 2016; Schaufeli et al., 2002). This conceptual ambivalence leads to practical difficulties in establishing parameters for the measurement of the construct (Jimerson et al., 2003). Consequently, various instruments have been developed to measure engagement, and to some extent, they have coincided in similar dimensions.

An example of this is the proposal by Aspeé et al. (2019), whose theoretical structure is comprised of three dimensions: academic development-oriented engagement, personal-integral development-oriented engagement, and citizen development-oriented engagement. These dimensions address the theoretical principles mentioned earlier that make up the engagement and involvement of students in academic activities.

On the other hand, Lara et al. (2018) proposed a different three-dimensional structure for measuring academic engagement, which includes a cognitive, behavioral, and affective dimension. This theoretical proposal includes specific aspects of the engagement experience, as well as the measurement of a person’s involvement at the behavioral, cognitive, and affective levels. Additionally, Zapata et al. (2018) designed and validated an instrument that linked the concept of engagement to indicators such as the quality of interactions, learning strategies, institutional support, and collaborative learning, among others. Furthermore, Parra and Pérez (2010) developed an instrument for psychology students, whose theoretical structure characterized engagement in three dimensions: dedication, vigor, and absorption. However, their findings were not empirically consistent with the proposed model, as they obtained a bifactorial structure.

Based on this, there has been a preference for studying this construct from a more specific perspective: tasks and activities carried out in the classroom. Engagement in this context is defined as a set of favorable behaviors exhibited by students, such as effort, enthusiasm, and initiative (Jang et al., 2016). In this way, Yévenes-Márquez et al. (2022) designed the Engagement to Academic Tasks Questionnaire (Comp-TA) with three dimensions: cognitive, behavioral, and emotional. Firstly, the cognitive dimension is understood as the student’s investment and effort in their studies. Secondly, the behavioral dimension refers to the consistency of effort, attendance, tasks, and desired academic behaviors (Fredricks et al., 2004; Shernoff et al., 2016). Finally, the emotional dimension corresponds to the affective connection, and understanding of how students approach academic activities (Fredricks et al., 2004). Shernoff et al. (2016) add that this dimension relates to the student’s emotions in response to their classroom tasks. Moreover, while the questionnaire Yévenes-Márquez et al. (2022) developed was for a school context, it is also applicable in higher education and possesses good psychometric properties.

Thus, the Comp-TA was developed based on three instruments: School Engagement (Lara et al., 2018), the Academic Involvement instrument (Rigo & Donolo, 2018), and the School Task Engagement Scale (Peña et al., 2017). The first instrument was validated in adolescent students and consisted of three factors with adequate reliability coefficients (Cronbach’s alpha ranging from .83 to .87). Additionally, the model showed suitable fit indices (RMSEA = .05, CFI = .94, TLI = .93). The second instrument for Academic Involvement was validated in university students and comprised six factors: attachment to the university, classroom attention, active participation, dedication, task focus, and social integration. The internal consistency of the instrument was confirmed with Cronbach’s alpha (.896) and theta (.91) (Peña et al., 2017). Lastly, the School Task Engagement Scale was adapted and validated in elementary school students; it was subdivided into three dimensions with adequate reliability coefficients (Cronbach's alpha ranging between .70 and .76) and suitable fit indices for the model with GFI = .92, CFI = .93, and RMSEA = .04 (Rigo & Donolo, 2018).

On the other hand, gender has been shown to relate to academic engagement (Ayub et al., 2017; Dominguez-Lara et al., 2021). The literature suggests that women exhibit higher levels of engagement (Carvajal & Carranza, 2022; Hsieh & Yu, 2023). This difference may have a cultural origin that is reflected in academic tasks (Maluenda et al., 2022; Maunula et al., 2023). However, it is essential to emphasize that most of these studies have not considered the gender invariance implications when conducting validity analyses (Barghaus et al., 2023). Consequently, it is critical to carry out an invariance analysis as a procedure that could promote more objective and bias-free measurement.

Measuring academic engagement in college students is relevant in identifying to what extent the educational experience impacts the development of future professionals. Therefore, the main objective of this study was to evaluate the psychometric properties of an adaptation and extension of the Comp-TA questionnaire (Yévenes-Márquez et al., 2022) with a sample of college students in Metropolitan Lima. As a specific objective, an invariance analysis based on the participants’ gender, will be carried out.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 297 university students from Lima, Peru. Female students made up 58.2 % of the sample, while male students accounted for 41.8 % of it. The participants’ ages ranged from 18 to 32 years (M = 20.87, SD = 2.29). Additionally, the participants were enrolled in university programs ranging from the second to the twelfth academic term (M = 6, SD = 2.65). Inclusion criteria required that all participants were of legal age, had taken virtual courses during the 2022-1 academic term, and were enrolled in the university.

To participate in the research, the respondents read an informed consent, which outlined the importance and purpose of the study, as well as its requirements. To safeguard their integrity, it was specified that participation was voluntary, anonymous, and confidential. Furthermore, they were assured that they could withdraw from the research at any time without experiencing any negative consequences.

Measures

The Engagement to Academic Tasks Questionnaire (Comp-TA) was developed by Yévenes-Márquez et al. (2022). It consists of 15 items and three underlying factors related to academic engagement: behavioral (7 items), cognitive (4 items), and emotional (4 items). The questionnaire uses a Likert response format ranging from 1 to 7, where 1 was Strongly Disagree, 2: Somewhat Disagree, 3: Disagree, 4: Neither Agree nor Disagree, 5: Agree, 6: Somewhat Agree, and 7: Strongly Agree.

Regarding the instrument’s validity, in the exploratory factor analysis, the Unweighted Least Squares extraction method and the Promin oblique rotation method were used. The Bartlett’s sphericity test was significant, with a KMO of 0.86, indicating that the correlation matrix was suitable for factor analysis. A three-factor solution was extracted, explaining a total of 57 % of the variance, which is considered an adequate percentage (Pérez & Medrano, 2010). Concerning the psychometric properties of the scale, the fit indices obtained in the Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFI = .92, TLI = .90, RMSEA = .07) indicate a satisfactory internal structure validity, comprising three dimensions (Kline, 2016).

Additionally, a protocol was designed, in which experts in the field were asked to evaluate the instrument’s items based on three criteria: Relevance, Sufficiency, and Coherence. Relevance pertains to whether the proposed item corresponds to the assigned dimension. Sufficiency relates to whether the item is suitable for measuring the evaluated concept. Lastly, Coherence assesses whether the item is appropriate in terms of wording.

Procedure

The present research employs a quantitative research design aimed at validating an instrument through expert judgment and psychometric assessments. To adapt the Comp-TA for a population of university students in Lima, permission was obtained from the authors of the original instrument for its use and application. After obtaining this permission, the authors of the current research translated the items into Spanish. Subsequently, the questionnaire underwent a content validation process involving four expert judges. Afterward, the questionnaire was adapted into a digital format using Google Forms and incorporated the informed consent and sociodemographic data sheet. This allowed for an online pilot test of the questionnaire with four participants, during which comments and observations regarding the instrument were collected. Following this, the instrument was administered, and the data collection was conducted virtually.

Data analysis

For the present study, RStudio version 2022.12.0 was used. First, descriptive analyses and the Aiken criterion were performed. Additionally, the internal reliability of the three dimensions and the overall instrument was analyzed using Cronbach’s alpha and McDonald’s omega coefficients. Regarding the aim of the study, a Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) will be conducted to determine if the structure of the original model is maintained through this analysis. In this regard, the Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA), Standardized Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR), Comparative Fit Index (CFI), and Tuker-Lewis Index (TLI) will be reviewed. Acceptable values for these factors are as follows: RMSEA < .06, SRMR < .08, CFI > .95, TLI > .95. For Invariance analyses (metric and scalar), the cutoff points proposed by Rutkowski and Svetina (2014) will be considered, these suggest that the values for scalar and metric invariance fit indices should be as follows: ΔCFI > -.010, ΔRMSEA < .015.

Results

First, descriptive analyses of the instrument (items, dimensions, and total score) are reported (Table 1). Regarding content validity, the results obtained for each item are reported (Table 2).

Subsequently, a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was conducted to verify that the original three-dimensional structure of the scale is replicated in the current sample. The Mardia’s test was performed to check the assumption for structural equations, that the observed variables together follow a multivariate normal distribution (Kline, 2016). The Mardia’s test revealed skewness (ˆγ1 = 1747.64, p < .05) and multivariate kurtosis (ˆγ2 = 28.32, p < .05) indices of the set of questionnaire variables, indicating that the data did not follow a multivariate normal distribution.

CFA was carried out using the maximum likelihood estimation method with Satorra-Bentler correction (2001) due to the data not meeting the assumption of multivariate normality. This analysis confirmed the three-dimensional factorial structure of the adapted scale, yielding good fit indices (χ2(df) = 202.435(87), p < .001; S‑Bχ2 = 1.383, CFI = .924, TLI = .908, RMSEA = .067 (CI = .057-.077), SRMR = .056). The cognitive engagement dimension consisted of items 1, 2, 3, and 4; the behavioral engagement dimension included items 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, and 11; and the emotional engagement dimension comprised items 12, 13, 14, and 15. The factor loadings were significant (p < .001) and ranged from .510 to .855 (Figure 1).

Table 1: Descriptives of the Comp-TA Questionnaire

Table 2: Results from the validation by expert judgment

Figure 1: CFA Model of the Comp-TA Questionnaire

Subsequently, the reliability of internal consistency was examined using the alpha and omega coefficients for the factors of the Comp-TA. It was identified that the scale demonstrates overall good reliability with a total omega (ω) of .93. On one hand, the cognitive engagement factor showed high reliability with α = .82 and ω = .84. Similarly, the behavioral engagement factor also exhibited high reliability with α = .84 and ω = .89. Finally, the emotional engagement factor also achieved a high coefficient of α = .87 and ω = .89.

The next step was to review the instrument’s invariance properties based on the reported gender of the participants (Table 3). Invariance can be analyzed at three levels: metric (focusing on item and factor loading of observed variables), scalar (examining latent variables or factors), and configural (verifying if the factorial structure is similar across groups; Milfont & Fischer, 2010).

Table 3: Invariance across gender

*All the χ2 have a p-value < .001

According to the criteria proposed by Rutkowski and Svetina (2014), the results showed that the Engagement to Academic Tasks Questionnaire (Comp-TA) scale exhibited strong invariance across participant gender in both metric and scalar variance. These results indicate that there is no variability by participant gender, and the model’s structure remains consistent across these groups.

Discussion

The objective of the present study is to adapt the Comp-TA scale to the Peruvian context, gathering evidence of the scale’s validity and reliability with university students. The results indicate that the adapted questionnaire has psychometric properties to be considered valid and reliable.

Firstly, it is observed that adequate fit indices were found. Although there is literature that differs in cutoff points, the evidence collected falls within the parameters used by Hu and Bentler (1999), Schreiber et al. (2006), and Rutkowski and Svetina (2014). These results are also similar to the validity and reliability processes conducted by Lara et al. (2018) and Aspeé et al. (2019). An important aspect to consider is that the fit indices for metric and scalar invariance analysis meet the parameters proposed by Rutkowski and Svetina (2014). This analysis is crucial because it provides evidence that there are no significant relevant differences in the factor loadings across the sample. In this sense, the results indicate that the items do not respond differently between groups (gender), implying that the strength of the relationships between the items on the scale and the underlying model is the same in all groups (Milfont & Fischer, 2010).

An important point to highlight is that there are not many studies that have performed invariance analysis when validating psychometric instruments measuring engagement, making this study provide relevant evidence regarding the original factorial structure. Furthermore, maintaining model invariance based on participant gender is relevant for measuring engagement, as there could be differences between groups due to cultural background. Not finding these differences suggests that the model is not affected by participant gender.

On the other hand, the results support the original factorial structure, identifying a three-dimensional model similar to that proposed by Yévenes-Márquez et al. (2022), Fredricks et al. (2004), and Tannoubi et al. (2023). These results reaffirm the importance of studying engagement, considering the interaction of these dimensions, as it allows the study of the degree of intensity and duration of a behavior in the academic context (Freiberg-Hoffmann et al., 2022).

In this regard, Yevénes-Márquez et al. (2022) point out that engagement in the classroom must include emotional, cognitive, and behavioral experiences that interact when facing an academic activity. This implies that the three dimensions can maintain a coherent relationship among them, as evidenced in the presented model.

Regarding gender invariance, when testing for configural, metric, and scalar invariance, it was found that there is no variability based on participant gender. This analysis tests whether different groups respond to the items in the same way, meaning that the strength of the relationships between the items on the scale and the underlying construction is the same in all groups (Hirschfeld & von Brachel, 2014; Milfont & Fisher, 2010). In this case, it is possible to compare the ratings of male and female students, and observed differences in Comp-TA elements may indicate group differences in academic engagement.

Regarding reliability, the reliability coefficients, alpha, and omega, obtained for the three dimensions of Comp-TA were higher than .70, indicating adequate levels of internal consistency in the studied sample (Hair et al., 1998; Ventura-León, & Caycho-Rodríguez, 2017). In this sense, the observed results are similar to the study by Yévenes-Márquez et al. (2022) and are sufficient for conducting future research studies with the validated scale.

On the other hand, among the strengths of Comp-TA, it is noteworthy that it can be applied easily and quickly, identifying three dimensions that have practical functionality within the classroom: emotional, behavioral, and cognitive. In this sense, it is possible to determine which dimension should be addressed by the teacher. Additionally, using Comp-TA allows the identification of whether students’ engagement is being positively affected by innovative educational interventions.

As for the limitations of this study, it is important to note that other constructs related to academic engagement were not measured in this research. Future research could evaluate other psychological variables in the nomological network of academic engagement to obtain evidence of convergent, discriminant, and/or criterion validity. Moreover, regarding the study sample, it is essential to highlight that the participants were students from a university in Lima, and due to their particular characteristics, they do not sufficiently represent the reality of university students in the rest of the country. It is suggested that in the future, the study of the psychometric properties of Comp-TA can be extended to university students from other regions of Peru.

Despite the limitations, the Spanish version of Comp-TA applied to university students in Lima is considered a consistent and suitable tool for measuring academic engagement in this population.

References:

Alrashidi, O., Phan, H. P., & Ngu, B. H. (2016). Academic engagement: an overview of its definitions, dimensions, and major conceptualizations. International Education Studies, 9(12), 41-52. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v9n12p41

Aspeé, J., González, J., & Cavieres, E. (2019). Instrumento para medir el compromiso estudiantil integrando el desarrollo ciudadano: una propuesta desde Latinoamérica. Revista Complutense de Educación, 30(2), 399-421. https://doi.org/10.5209/RCED.57518

Ayub, A., Yunus, A., Mahmud, R., Salim, N. & Sulaiman, T. (2017). Differences in students’ mathematics engagement between gender and between rural and urban schools. AIP Conference Proceedings, 1(1795), 1-6. https://doi.org/10.1063/1.4972169

Bae, Y., & Han, S. (2019). Academic Engagement and Learning Outcomes of the Student Experience in the Research University: Construct Validation of the Instrument. Educational Sciences: Theory and Practice, 19(3), 49-64. https://doi.org/10.12738/estp.2019.3.004

Barghaus, K., Henderson, C., Fantuzzo, J., Brumley, B., Coe, K., LeBoeuf, W., & Weiss, E. (2023). Classroom Engagement Scale: validation of a teacher-report assessment used to scale in the kindergarten report card of a large urban school district. Early Education and Development, 34(1), 306-328. https://doi.org/10.1080/10409289.2021.1985047

Boekaerts, M. (2016). Engagement as an inherent aspect of the learning process. Learning and Instruction, 43, 76-83. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.02.001

Carmona-Halty, M. A., Schaufeli, W. B., & Salanova, M. (2019). The Utrecht Work Engagement Scale for Students (UWES–9S): Factorial validity, reliability, and measurement invariance in a Chilean sample of undergraduate university students. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1-5. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01017

Carvajal, C., & Carranza, R. (2022). Propriedades psicométricas da escala de envolvimento acadêmico em estudantes universitários bolivianos. Horizontes Revista de Investigación en Ciencias de la Educación, 6(26), 2254-2264. https://doi.org/10.33996/revistahorizontes.v6i26.489

Da Rocha Seixas, L., Gomes, A. S., & de Melo Filho, I. J. (2016). Effectiveness of gamification in the engagement of students. Computers in Human Behavior, 58, 48-63. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.11.021

Dominguez-Lara, S., Sánchez-Villena, A. R., & Fernández-Arata, M. (2020). Propiedades psicométricas de la UWES-9S en estudiantes universitarios peruanos. Acta Colombiana de Psicología, 23(2), 7-23. https://doi.org/10.14718/acp.2020.23.2.2

Dominguez-Lara, S., Fernández-Arata, M., & Seperak-Viera, R. (2021). Análisis psicométrico de una medida ultra-breve para el engagement académico: UWES-3S. Revista Argentina de Ciencias del Comportamiento, 13(1), 25-37. https://doi.org/10.32348/1852.4206.v13.n1.27780

Fredricks, J. A., Blumenfeld, P. C., & Paris, A. H. (2004). School Engagement: Potential of the concept, state of the evidence. Review of Educational Research, 74(1), 59-109. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/00346543074001059

Fredricks, J. A., Filsecker, M., & Lawson, M. A. (2016). Student engagement, context, and adjustment: Addressing definitional, measurement, and methodological issues. Learning and Instruction, 43, 1-4. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.02.002

Comp-TA -Hoffmann, A., Romero-Medina, A., Curione, K., & Marôco, J. (2022). Adaptación y validación transcultural al español del University Student Engagement Inventory. Revista Latinoamericana de Psicología, 54, 187-195. https://doi.org/10.14349/rlp.2022.v54.21

Guerra, F., & Jorquera, R. (2021). Análisis psicométrico de la Utrecht Work Engagement Scale en las versiones UWES-17S y UWES-9S en universitarios chilenos. Revista Digital de Investigación en Docencia Universitaria, 15(2), 1-13. http://dx.doi.org/10.19083/ridu.2021.1542

Gutiérrez, M., Tomás, J. M., Barrica, J. M., & Romero, I. (2017). Influencia del clima motivacional en clase sobre el compromiso escolar de los adolescentes y su logro académico. Enseñanza & Teaching: Revista Interuniversitaria de Didáctica, 35(1), 21-37. https://doi.org/10.14201/et20173512137

Hair, J. F., Anderson, R. E., Tatham, R. L., & Black W. C. (1998). Multivariate Data Analysis (5ª ed.). Prentice Hall.

Hew, K. F., Huang, B., Chu, K. W. S., & Chiu, D. K. (2016). Engaging Asian students through game mechanics: Findings from two experiment studies. Computers & Education, 92, 221-236. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2015.10.010

Hirschfeld, G., & von Brachel, R. (2014). Improving multiple-group confirmatory factor analysis in R–A tutorial in measurement invariance with continuous and ordinal indicators. Practical Assessment, Research, and Evaluation, 19(7), 1-12. https://doi.org/10.7275/qazy-2946

Hsieh, T. L., & Yu, P. (2023). Exploring achievement motivation, student engagement, and learning outcomes for STEM college students in Taiwan through the lenses of gender differences and multiple pathways. Research in Science & Technological Education, 41(3), 1072-1087.

Hu, L., & Bentler, P. M. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6(1), 1-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Jang, H., Kim, E. J., & Reeve, J. (2016). Why students become more engaged or more disengaged during the semester: A self-determination theory dual-process model. Learning and Instruction, 43, 27-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2016.01.002

Jimerson, S. R., Campos, E., & Greif, J. L. (2003). Toward an understanding of definitions and measures of school engagement and related terms. Contemporary School Psychologist, 8(1), 7-27. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF03340893

Kline, R. (2016). Principles and Practice of Structural Equation Modeling. The Guilford Press.

Lara, L., Saracostti, M., Navarro, J. J., De-Toro, X., Miranda-Zapata, E., Trigger, J. M., & Fuster, J. (2018). Compromiso escolar: Desarrollo y validación de un instrumento. Revista Mexicana de Psicología, 35(1), 52-62.

Laureano, S. E., Ortiz, D. E., & Valle, L. M. (2020). Validación de la Utrecht Work Engagement Scale (UWES) en personal docente de pre-grado de universidades privadas en Lima Metropolitana [Master's Dissertation, Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola]. Repositorio Institucional - USIL. https://repositorio.usil.edu.pe/handle/usil/10452

Maluenda, J., Berríos, J., Infante, V., & Lobos, K. (2022). Perceived social support and engagement in first-year students: the mediating role of belonging during COVID-19. Sustainability, 15(1), 597. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15010597

Matta, E. P. (2021). Engagement académico y empatía en estudiantes de la Escuela Profesional de Medicina Humana de la Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos [Doctoral Dissertation, Universidad Nacional de Educación Enrique Guzmán y Valle]. Repositorio Institucional de la Universidad Nacional de Educación. http://repositorio.une.edu.pe/handle/20.500.14039/5685

Maunula, M., Maunumäki, M., Marôco, J., & Harju-Luukkainen, H. (2023). Developing students well-being and engagement in higher education during COVID-19: A case study of web-based learning in Finland. Sustainability, 15(4), 3838. https://doi.org/10.3390/su15043838

Milfont, T. L., & Fischer, R. (2010). Testing measurement invariance across groups: Applications in cross-cultural research. International Journal of Psychological Research, 3(1), 111-121. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-007-9143-x

Navarro, R., López, R., & Caycho, G. (2021). Retos de los docentes universitarios para el diseño de experiencias virtuales educativas en pandemia. Desde el Sur, 13(2), 1-19. https://doi.org/10.21142/DES-1302-2021-0017

Oriol-Granado, X., Mendoza-Lira, M., Covarrubias-Apablaza, C. G., & Molina-López, V. M. (2017). Emociones positivas, apoyo a la autonomía y rendimiento de estudiantes universitarios: el papel mediador del compromiso académico y la autoeficacia. Revista de Psicodidáctica, 22(1), 45-53. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1136-1034(17)30043-6

Parra, P., & Pérez, C. (2010). Propiedades psicométricas de la escala de compromiso académico, UWES-S (versión abreviada), en estudiantes de psicología. Revista de Educación en Ciencias de la Salud, 7(2), 128-133.

Peña, G., Cañoto, Y., & Angelucci, L. (2017). Involucramiento académico: una escala. Páginas de Educación, 10(1), 114-136. http://dx.doi.org/10.22235/pe.v10i1.1361

Pérez, E. R., & Medrano, L. A. (2010). Análisis factorial exploratorio: bases conceptuales y metodológicas. Revista Argentina de Ciencias del Comportamiento, 2(1), 58-66. https://doi.org/10.32348/1852.4206.v2.n1.15924

Reschly, A. L., & Christenson, S. L. (2012). Jingle, Jangle, and Conceptual Haziness: Evolution and Future Directions of the Engagement Construct. In S. Christenson, A. Reschly, & C. Wylie (Eds.), Handbook of Research on Student Engagement (pp. 3-19). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-2018-7_1

Rigo, D. Y., & Donolo, D. (2018). Construcción y validación de la Escala de compromiso hacia las tareas escolares en las clases para los estudiantes del nivel primario de educación. Psicoespacios: Revista virtual de la Institución Universitaria de Envigado, 12(21), 3-22. https://doi.org/10.25057/issn.2145-2776

Rutkowski, L., & Svetina, D. (2014). Assessing the Hypothesis of Measurement Invariance in the Context of Large-Scale International Surveys. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 74(1), 31-57. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0013164413498257

Satorra, A., & Bentler, P. M. (2001). A scaled difference chi-square test statistic for moment structure analysis. Psychometrika, 66(4), 507-514. https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02296192

Schaufeli, W. B., Bakker, A. B., & Salanova, M. (2006). The Measurement of work engagement with a short questionnaire: a cross–national study. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 66(4), 701-716. https://doi.org/10.1177/0013164405282471

Schaufeli, W. B., Salanova, M., González-Romá, V., & Bakker, A. B. (2002). The measurement of engagement and burnout: a two sample confirmatory factor analytic approach. Journal of Happiness Studies, 3(1), 71-92. http://dx.doi.org/10.1023/A:1015630930326

Schreiber, J. B., Nora, A., Stage, F. K., Barlow, E. A., & King, J. (2006). Reporting structural equation modeling and confirmatory factor analysis results: A review. The Journal of Educational Research, 99(6), 323-338. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338

Shernoff, D. J., Kelly, S., Tonks, S. M., Anderson, B., Cavanagh, R. F., Sinha, S., & Abdi, B. (2016). Student engagement as a function of environmental complexity in high school classrooms. Learning and Instruction, 43, 52-60. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2015.12.003

Tannoubi, A., Quansah, F., Hagan, J., Srem-Sai, M., Bonsaksen, T., Chalghaf, N., Boussayala, G., Azaiez, C., Snani, C., & Azaiez, F. (2023). Adaptation and Validation of the Arabic Version of the University Student Engagement Inventory (A-USEI) among Sport and Physical Education Students. Psych, 5(2), 320-335. https://doi.org/10.3390/psych5020022

Ventura-León, J. L., & Caycho-Rodríguez, T. (2017). El coeficiente Omega: un método alternativo para la estimación de la confiabilidad. Revista Latinoamericana de Ciencias Sociales, Niñez y Juventud, 15(1), 625-627.

Vilela, P., Sánchez, J., & Chau, C. (2021). Desafíos de la educación superior en el Perú durante la pandemia por la covid-19. Desde el Sur, 13(2), 1-11. http://dx.doi.org/10.21142/des-1302-2021-0016

Yévenes-Márquez, J. N., Badilla-Quintana, M. G., & Sandoval-Henríquez, F. J. (2022). Measuring engagement to academic tasks: design and validation of the Comp-TA Questionnaire. Education Research International, 2022, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1155/2022/4783994

Zapata, G., Leihy, P., & Theurillat, D. (2018). Compromiso estudiantil en educación superior: adaptación y validación de un cuestionario de evaluación en universidades chilenas. Calidad en la educación, (48), 204-250. http://dx.doi.org/10.31619/caledu.n48.482

Data availability: The dataset supporting the results of this study is not available.

Funding: The data analyzed in this article was collected as part of a research project funded by the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú within the framework of the Annual Research Project Competition (CAP).

How to cite: Navarro, R., Morote, F., García, A., Bernal, V., & Teran, V. (2023). Validity of the Engagement to Academic Tasks Questionnaire in Peruvian college students. Ciencias Psicológicas, 17(2), e-3207. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i2.3207

Authors’ participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript.

R. N. has contributed in a, b, c, d, e; F. M. in a, b, c, d, e; A. G. in a, b, c, d, e; V. B. in a, b, c, d, e; V. T. in a, d, e.

Scientific editor in-charge: Dra. Cecilia Cracco.