10.22235/cp.v17i2.3193

Satisfacción con la enseñanza online en estudiantes universitarios: análisis estructural de una escala

Satisfaction with online teaching in university students: Structural analysis of a scale

Satisfação com o ensino online em universitários: Análise estrutural de uma escala

Denisse Manrique-Millones1, ORCID 0000-0003-4602-5396

Susana K. Lingán-Huamán2, ORCID 0000-0003-4587-7853

Sergio Dominguez-Lara3, ORCID 0000-0002-2083-4278

1 Universidad Científica del Sur, Perú

2 Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola, Perú

3 Universidad Privada Norbert Wiener, Perú, [email protected]

Resumen:

El objetivo de esta investigación fue analizar la estructura interna y confiabilidad de la Student Satisfaction Survey (SSS) en estudiantes universitarios peruanos. Participaron 458 estudiantes (mujeres = 69.9 %; Medad = 27.76 años; DEedad = 4.41 años). La SSS se estudió bajo el análisis factorial confirmatorio (AFC) y el modelamiento exploratorio de ecuaciones estructurales (ESEM). Respecto a los resultados, el modelo original de cinco dimensiones obtuvo índices de ajuste favorables con ESEM, pero las dimensiones interacciones alumno-profesor e interacciones alumno-alumno se superponen entre sí, por lo que se valoró un modelo de cuatro dimensiones que presentó mejores evidencias psicométricas. La confiabilidad de las puntuaciones y de constructo presenta magnitudes aceptables. Se concluye que el SSS cuenta con propiedades psicométricas adecuadas.

Palabras clave: internacionalización; movilidad estudiantil; adultez emergente; identidad profesional.

Abstract:

The aim of this research study was to analyze the internal structure and reliability of the Student Satisfaction Survey (SSS) in Peruvian university students. A total of 458 students participated (women = 69.9 %; Mage = 27.76 years; SDage = 4.41 years). The SSS was studied under confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM). Regard the results, the original five-dimensional model obtained favorable fit indexes with ESEM, but the dimensions student-teacher interactions and student-student interactions overlap each other, so it was valued as a four-dimensional model that presented better psychometric evidence. Regarding reliability, an acceptable order of magnitudes was observed, both at the level of scores and construct. It can be concluded that the SSS has adequate psychometric properties.

Keywords: satisfaction with online teaching; higher education; distance education; validity; reliability.

Resumo:

O objetivo deste estudo foi analisar a estrutura interna e a confiabilidade da Student Satisfaction Survey (SSS) em estudantes universitários peruanos. Participaram 458 estudantes (mulheres = 69,9 %; Midade = 27,76 anos; DPidade = 4,41 anos). O SSS foi estudado por meio de análise fatorial confirmatória (CFA) e modelação exploratória de equações estruturais (ESEM). Quanto aos resultados, o modelo original de cinco dimensões obteve índices de ajuste favoráveis com ESEM, mas as interações entre as dimensões aluno-professor e aluno-aluno se sobrepõem, por isso, foi analisado um modelo quatro dimensões que apresentou melhor evidência psicométrica. A confiabilidade das pontuações e de construto apresentaram magnitudes aceitáveis. Conclui-se que o SSS possui propriedades psicométricas adequadas.

Palavras-chave: satisfação com ensino online; ensino superior; educação a distância; validade; confiabilidade.

Recibido: 31/01/2023

Aceptado: 04/10/2023

Antes de la pandemia, la enseñanza online cobraba gradualmente mayor protagonismo en el panorama de la educación superior peruana, acorde con las nuevas tendencias pedagógicas vinculadas con la integración de las tecnologías de la información y las comunicaciones (TIC; Dominguez-Lara et al., 2022). Sin embargo, las dudas sobre la calidad de los procesos formativos en la enseñanza online se manifestaron mediante los resultados del proceso de licenciamiento y la acreditación de la calidad educativa a cargo de la Superintendencia Nacional de Educación Superior (Sunedu), que es el órgano rector de evaluación de las universidades en el marco de la reforma universitaria en Perú. Como producto del proceso mencionado, se negó la licencia de funcionamiento a 48 de las 140 universidades que se presentaron al proceso de evaluación porque no lograron evidenciar el cumplimiento de condiciones básicas de calidad (Benites, 2021), y muchas de estas universidades brindaban programas de enseñanza online. De esta forma, los efectos de la pandemia en el ámbito educativo peruano emergieron en un contexto en el que la reforma universitaria estaba encaminada y había puesto en evidencia una serie de problemas institucionales, donde la enseñanza online no era prioritaria para las casas de educación superior.

En este panorama, las universidades enfrentaron muchos desafíos para el desarrollo de la educación online durante el estado de emergencia sanitario y posterior a este. Así, algunos de los obstáculos se relacionaron con la falta de acceso a dispositivos tecnológicos o a una conexión de internet estable por parte de estudiantes y profesores (Álvarez et al., 2020), mientras que otras limitaciones se asociaron con las habilidades exigidas a los actores educativos. De un lado, se requería que el estudiante asumiera un rol más activo y autónomo en su propio proceso de aprendizaje, lo que, aunado al estrés propio de un contexto pandémico, lo hacía emocionalmente más vulnerable (Moreta-Herrera et al., 2022); y, por otro lado, los profesores estaban forzados a usar y dominar las TIC rápidamente e integrarlas a sus actividades instruccionales luego de una breve capacitación, y en ocasiones de forma intuitiva.

A pesar de estos inconvenientes, los efectos de la pandemia posibilitaron la reflexión en torno al replanteamiento de nuevas formas de aprender y enseñar, en consonancia con el avance tecnológico, y permitieron identificar una valiosa oportunidad para la reinvención pedagógica y la modernización de la universidad (Watermeyer et al., 2020). Todo ello debido a que muchos estudiantes universitarios prefieren la educación online motivados por las facilidades que ofrece al articular la vida académica, laboral y familiar (Waters & Russell, 2016), siendo un mecanismo eficaz para acortar las brechas de acceso a la educación superior (Kong et al., 2017). Por tanto, las universidades deben generar propuestas de educación online de calidad y preparar a los estudiantes y a sus profesores para un mundo integrado con la tecnología (Sánchez-González & Castro-Higueras, 2022), dado que el blended learning (b-learning) combina ambos aspectos, es decir, actividades presenciales y online (Eryilmaz, 2015).

En este escenario es importante conocer la perspectiva del estudiante universitario, puesto que se ha demostrado que el éxito de un programa de educación online está asociado con su satisfacción (Kang & Park, 2022; Pham et al., 2019; Teo, 2010). Este aspecto es crucial para un aprendizaje efectivo y está directamente relacionado con el rendimiento académico, la retención, la motivación y el compromiso con el aprendizaje (Basith et al., 2020; Pham et al., 2019; Teo, 2010; Ye et al., 2022), aspectos que, a su vez, están asociados con una mayor autonomía del estudiante (Vergara-Morales et al., 2022). Por lo mencionado, los gestores educativos tienen la obligación de evaluar de forma sistemática la satisfacción de los alumnos con los procesos educativos, ya que se sabe que la universidad es un entorno que genera diversos desafíos para el estudiante, ya sea a nivel académico, social, emocional e institucional (Gravini-Donado et al., 2021).

Desde una perspectiva clásica, la satisfacción del usuario es definida como un indicador de la distancia existente entre un estándar de comparación y el rendimiento percibido del bien o servicio que se está evaluando (Oliver, 1980). En el ámbito académico, la satisfacción del estudiante se refiere al juicio de valor sobre el cumplimiento de sus expectativas, necesidades y demandas durante su experiencia educativa (Bernard et al., 2009), aunque también se la ha definido como la actitud a corto plazo que se produce por la evaluación de su experiencia con el servicio educativo recibido (Onditi & Wechuli, 2017).

Por lo expuesto, el estudio de la satisfacción del estudiante en entornos de aprendizaje online es de creciente interés porque influye en la eficacia de la enseñanza y en el desarrollo de materiales de instrucción (Khan & Iqbal, 2016), principalmente porque su dinámica es distinta a la del aprendizaje presencial y se debe valorar según esas características. Considerar esto permitirá contar con información útil para diseñar nuevas asignaturas online y orientar la mejora del desempeño docente, así como los contenidos de aprendizaje y la calidad general de los programas académicos. Esto es relevante porque pese a las ventajas de la enseñanza online (eliminación de distancias físicas, flexibilidad horaria, etc.), se identificaron algunas limitaciones (problemas de comunicación interpersonal, escasa cooperación de los profesores o tutores virtuales, ausencia de contacto directo, etc.) que dificultan la adaptación de los estudiantes (Díaz et al., 2013) y, en consecuencia, perjudican el rendimiento académico y propician el abandono.

La educación online, de forma similar a la presencial, tiene sus bases en los procesos interactivos entre los participantes. Es así que Moore y Kearsley (2005) señalan que la efectividad de la enseñanza-aprendizaje dependerá de la naturaleza de esta interacción y de cómo se podría favorecer mediante un medio tecnológico (Moore, 2007). De este modo, Moore (1993, 1997) describe un conjunto de relaciones que también aparecen en la educación online cuando los estudiantes y profesores están distanciados por el espacio y por el tiempo, donde resalta tres tipos de interacciones para un aprendizaje efectivo.

La primera interacción es la de alumno-contenido, referida a las relaciones de los estudiantes con los contenidos de los módulos o unidades de aprendizaje, las lecciones y actividades de aprendizaje de las asignaturas, incluyendo lecturas, proyectos, videos, sitios web, etc. que conducen a cambios en la comprensión, la percepción y la estructura cognitiva e influyen significativamente sobre la satisfacción con la enseñanza online (Kuo, 2014).

La segunda interacción es la de alumno-profesor, que implica una relación bidireccional entre el estudiante y el instructor, que tiene por función recibir y dar retroalimentación, aclarando contenidos y despejando dudas a través de una comunicación fluida que facilita y motiva el aprendizaje (Yılmaz & Karataş, 2017). Este es un predictor significativo de la satisfacción en clases sincrónicas (Kuo et al., 2014).

La tercera interacción es la de alumno-alumno, que refiere a la relación bidireccional entre los estudiantes con el fin de compartir y aprender cooperativamente por distintos medios, como los foros de discusión, correos electrónicos o redes sociales, lo que crea una colaboración entre pares (Moore, 1993). Esta interacción es de naturaleza cognitivo y social, y es importante porque crea un sentido de comunidad (Shackelford & Maxwell, 2012) y potencia el aprendizaje.

Un cuarto tipo de interacción es la denominada interacción alumno-tecnología, propuesta de forma posterior a los tres originales (Hanna et al., 2000; Palloff & Pratt, 2001). Este alude a la comunicación entre el estudiante y el entorno virtual de aprendizaje, lo que implica saber utilizar las herramientas virtuales, así como tener las habilidades tecnológicas adecuadas. Este tipo de interacción se enfoca en la relación del estudiante con los medios y dispositivos tecnológicos necesarios para desarrollar el programa educativo y considera aspectos como la comodidad y funcionalidad de las herramientas (ordenadores, internet, software o plataformas educativas, etc.; Strachota, 2003).

La evidencia disponible indica que estos tipos de interacción son relevantes para la satisfacción y el rendimiento de los estudiantes (Alqurashi, 2019; Basith et al., 2020; Kuo et al., 2013), se destacan algunos aspectos asociados con la enseñanza online, tales como el diseño y los contenidos de las asignaturas, la accesibilidad de la información en la plataforma virtual, la facilidad de la interacción con el profesor (Martín-Rodríguez et al., 2015), las interacciones entre los estudiantes, la gestión administrativa y las actividades académicas relacionadas con los contenidos procedimentales de las asignaturas (Nortvig et al., 2018). Además, distintas investigaciones enfatizan en la preferencia de los estudiantes por la modalidad sincrónica del dictado de clases, que brindan la oportunidad de formular preguntas, debatir y reflexionar en tiempo real, complementada con un acceso asíncrono a la información de la asignatura y a las grabaciones de las clases (Amir et al., 2020; Chung et al., 2020; Ramo et al., 2021).

De acuerdo con el panorama planteado, la evaluación de las interacciones en entornos de aprendizaje online y la satisfacción con estas es importante, aunque los instrumentos de medida a disposición presentan algunas falencias o limitaciones metodológicas que impiden un uso válido y confiable en determinados aspectos. Por ejemplo, algunos instrumentos presentan solo reportes de confiabilidad (e.g., Baturay, 2011) y en otros trabajos este indicador se complementa únicamente con opinión de expertos (e.g., Wei et al., 2015), pero no cuentan con un análisis de la estructura interna del instrumento que permita diferenciar los constructos desde una perspectiva analítico-factorial.

Existen otros instrumentos que no presentan las omisiones procedimentales de los estudios mencionados previamente. Por ejemplo, una escala creada recientemente (Yılmaz & Karataş, 2017) fundamenta su estructura interna hipotética en el enfoque de Moore (1993), pero las decisiones metodológicas en su construcción resultan cuestionables, ya que el uso del análisis de componentes principales sobreestima la magnitud de las cargas factoriales y decidir el número de factores mediante el criterio de valor Eigen mayor que la unidad sugiere extraer una cantidad de factores mayor a la óptima (Lloret-Segura et al., 2014). Además, el uso de la misma muestra tanto para el análisis exploratorio como para el confirmatorio es una práctica no recomendada debido a que brinda resultados poco concluyentes (Pérez-Gil et al., 2000).

Otro instrumento disponible es la Student Satisfaction Survey (SSS; Strachota, 2003, 2006), que evalúa los componentes dialógicos de las interacciones en el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje con base en los planteamientos de Moore y Kearsley (2005), complementados con la interacción entre el alumno y la tecnología y una dimensión de satisfacción general. Entre las ventajas que ofrece el uso de la SSS se encuentra que puede ser aplicable a todos los niveles formativos de la educación superior desde una perspectiva teórica multidimensional sin incluir un gran número de ítems. La SSS presenta adecuadas propiedades psicométricas, incluyendo evidencias de validez de contenido de los ítems y un análisis de su estructura interna mediante análisis factorial, aunque bajo un enfoque exploratorio.

Numerosos trabajos han usado la SSS para medir directamente interacciones dialógicas en función de la satisfacción de los estudiantes, tanto en entornos de aprendizaje online como en entornos mixtos (Mbwesa, 2014; Mohamed, 2021; Torrado & Blanca, 2022). Por ejemplo, en una investigación realizada con población universitaria en modalidad online y semipresencial se midió cómo las interacciones en entornos de aprendizaje combinados y online afectaron los resultados de aprendizaje medidos mediante la satisfacción de los estudiantes y sus calificaciones. Los hallazgos arrojaron que la interacción que afectó los resultados de aprendizaje fue la díada alumno-contenido, y además se resaltó la importancia de la interacción alumno-profesor y alumno-alumno en ambientes de aprendizaje online (Ekwunife-Orakwue & Teng, 2014). En otro estudio se investigó las relaciones entre la autoeficacia académica, la autoeficacia informática, la experiencia previa y la satisfacción con el aprendizaje online, y se encontró una relación directa y significativa entre autoeficacia académica y satisfacción con el aprendizaje online (Jan, 2015). Por otra parte, se analizó la influencia de la interacción dialógica transaccional en la satisfacción de los alumnos en un entorno de aprendizaje mixto multiinstitucional, y se encontraron efectos significativamente positivos de la interacción transaccional sobre la satisfacción en entorno de aprendizaje mixto (Best & Conceição, 2017).

El objetivo del presente trabajo fue analizar las propiedades psicométricas de la SSS en estudiantes universitarios peruanos en un contexto de enseñanza online. Por un lado, se examinó la estructura interna mediante el uso de modelamiento exploratorio de ecuaciones estructurales (ESEM, por sus siglas en inglés) y, por otro lado, se estudió la consistencia interna de la escala. Este estudio se justifica a nivel teórico porque ayuda a comprender la estructura de la satisfacción con la enseñanza online en estudiantes peruanos, dado que el abordaje de este constructo es emergente en Perú, y a pesar de que existen algunos estudios pre-pandemia (e.g., Vásquez-Pajuelo, 2019), no se presentan de forma clara las propiedades psicométricas de los instrumentos empleados, lo que no permite obtener conclusiones satisfactorias. Asimismo, a nivel práctico, se proveerá a las instituciones de un instrumento que evalúe las interacciones dialógicas implicadas en el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje online y que proporcione información útil sobre las áreas que se necesiten mejorar mediante el diseño de entornos de aprendizaje que permitan aprovechar los recursos disponibles (Hanson et al., 2016; Magadán-Díaz & Rivas-García, 2022).

Por último, a nivel metodológico, aunque las evidencias de validez obtenidas en los estudios pioneros bajo un enfoque exploratorio representan un buen punto de partida (Strachota, 2003, 2006), es necesario analizar la escala bajo enfoques contemporáneos y que brinden mayor información como el ESEM (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2009). El ESEM provee los índices de ajuste habituales para valorar el modelo de forma similar al análisis factorial confirmatorio, pero también otorga una estimación completa de las cargas factoriales (principales y secundarias) de la misma forma que el análisis factorial exploratorio, además de realizar una estimación más precisa de las correlaciones interfactoriales (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2009), lo que mejoraría la comprensión del constructo. No obstante, si bien algunos trabajos emplean el análisis confirmatorio (e.g., Yılmaz & Karataş, 2017), este enfoque asume que los ítems solo reciben influencia de su factor teórico y dejan de lado a los otros factores involucrados en el modelo de medición, lo que representaría un inconveniente al momento de realizar los análisis (Marsh et al., 2014), ya que las medidas de constructos complejos (como la satisfacción) suelen tener ítems con cargas cruzadas en otros factores, y si no se especifican, incluso cargas factoriales insignificantes (≈ .10) afectarán negativamente el modelo (Asparouhov et al., 2015).

Método

Diseño

Se trata de diseño instrumental (Ato et al., 2013) orientado al análisis de las propiedades psicométricas de la Student Satisfaction Survey (Strachota, 2006).

Participantes

Participaron 458 estudiantes universitarios (69.9 % mujeres; 31.1 % varones) peruanos de diversas carreras profesionales de instituciones privadas. La edad osciló entre 17 y 56 años (M = 27.76; DE = 4.41), en su mayoría solteros (90.6 %) y más de la mitad usaba internet más de 20 horas a la semana (52.2 %), mientras que solo un 4.4 % lo hacía menos de cinco horas a la semana. El tipo de muestreo empleado fue por conveniencia, ya que se consideró la accesibilidad y disponibilidad en un momento dado o la voluntad de participar (Etikan, 2016), dadas las restricciones vigentes en Perú debido al confinamiento por la emergencia sanitaria.

Instrumento

Student Satisfaction Survey (SSS; Strachota, 2006). Se trata de una escala de autorreporte de 25 ítems, con cuatro opciones de respuesta (de totalmente en desacuerdo hasta totalmente de acuerdo). Evalúa la satisfacción general con la enseñanza online (e.g., “Me gustaría tomar otros cursos con el mismo ambiente de aprendizaje”), así como con diferentes dimensiones de la interacción dentro ese contexto de enseñanza tales como las interacciones alumno-contenido (e.g., “Los trabajos o proyectos en esos cursos han facilitado mi aprendizaje”), interacciones alumno-profesor (e.g., “He recibido comentarios oportunos de mis profesores”), interacciones alumno-alumno (e.g., “En los cursos he podido compartir mi punto de vista con otros estudiantes”), e interacciones alumno-tecnología (e.g., “Las computadoras son una buena ayuda para el aprendizaje”).

Procedimiento

Los datos se recolectaron en el marco de un proyecto enfocado en la satisfacción con la educación online durante la pandemia por la COVID-19 y se desarrolló según las recomendaciones éticas de la American Psychological Association y de la Declaración de Helsinki.

Se solicitó la autorización de la creadora para traducir el instrumento, lo cual se realizó con base en la literatura especializada (Muñiz et al., 2013). La primera etapa consistió en la traducción del inglés al español. Luego se entregó a diez estudiantes de Psicología quienes valoraron la claridad de los ítems y no hubo inconvenientes para comprender su contenido.

Un enlace de Google Forms fue enviado a los estudiantes entre los meses de junio y agosto del 2021. El formulario contenía el consentimiento informado, que tenía el título y la descripción del estudio, así como el carácter voluntario y anónimo de la participación, que podrían retirarse cuando quisieran, y el tratamiento confidencial de los datos.

Análisis de datos

Se analizó la estructura original de cinco factores mediante el análisis factorial confirmatorio (AFC) y el ESEM (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2009), porque no existen estudios que brinden otros modelos de medición. El análisis se ejecutó con el programa Mplus versión 7 (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2015).

Los valores de asimetría y curtosis, entre -2 y +2, indicarían una distribución aproximada a la normal univariada de los ítems (Gravetter & Wallnau, 2014), y la normalidad multivariada con el coeficiente de Mardia (G2 < 70). En cuanto al análisis estructural, se empleó el método de estimación WLSMV, dado que está orientado a ítems ordinales (Li, 2016a, 2016b), y con base en la matriz de correlaciones policóricas. El modelo analizado con AFC y ESEM se valoró con el CFI (> .90; McDonald & Ho, 2002), el RMSEA (< .08; Browne & Cudeck, 1993), considerando además el límite superior de su intervalo de confianza (< .10; West et al., 2012), y la WRMR (< 1; DiStefano et al., 2018). De la misma manera, tanto en el AFC como en el ESEM se analizó la validez interna convergente con la varianza media extraída (VME > .37; Rubia, 2019) y con la magnitud de las cargas factoriales (λ > .60; Dominguez-Lara, 2018a), así como la validez interna discriminante si la raíz cuadrada de la VME (√VME) es mayor que la correlación interfactorial (ϕ) entre dos dimensiones.

En cuanto al AFC, las correlaciones interfactoriales mayores que .90 sugieren redundancia factorial (Brown, 2015). Con relación al ESEM, se usó la rotación target oblicua (ε = .05; Asparouhov & Muthén, 2009), que estima libremente las cargas factoriales principales y secundarias, las cuales se especificaron como cercanas a cero (~0), para finalmente calcular el índice de simplicidad factorial (ISF) para valorar su relevancia. En ese sentido, se espera un ISF por encima de .70, lo que significa que el ítem recibe influencia de un solo factor (Lara et al., 2021).

Por otro lado, se estimó la confiabilidad de las puntuaciones (α > .70; Ponterotto & Charter, 2009) y del constructo (ω > .70; Hunsley & Marsh, 2008), y si la diferencia entre coeficientes es menor que |.06| (Δω-α) no se considera significativa (Gignac et al., 2007). De este modo, y en vista de que es deseable que los resultados de la SSS se configuren como perfil, se analizó la confiabilidad de la diferencia entre dos puntuaciones (ρd), que examina el grado en que la diferencia entre dos puntuaciones se explica más por la varianza verdadera que por la varianza del error, por lo que valores aceptables (> .70) informarían que la configuración del perfil brinda información relevante (Dominguez-Lara, 2018b; Muñiz, 2003).

Resultados

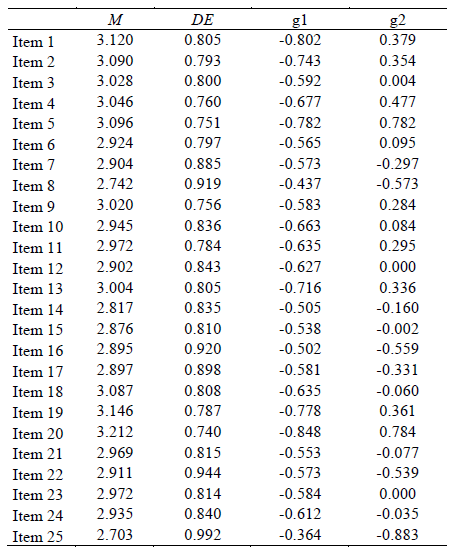

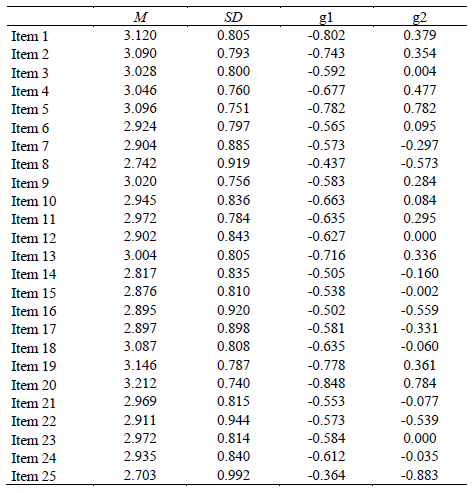

Los ítems presentan una magnitud de asimetría y curtosis que permiten una aproximación razonable a la normalidad univariada (Tabla 1), pero no a la normalidad multivariada (G2 = 291.775).

Tabla 1: Estadísticos descriptivos de los ítems de la Student Satisfaction Survey

Nota: M: Media; DE: Desviación estándar; g1: asimetría; g2: curtosis.

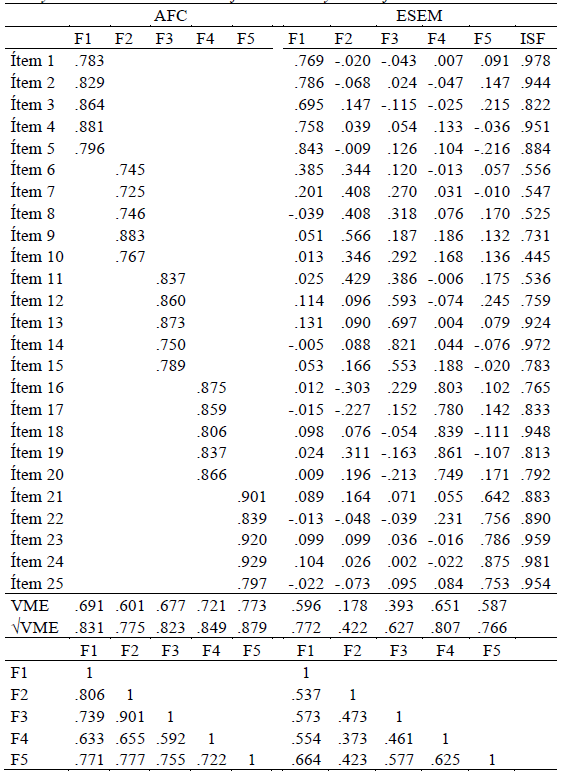

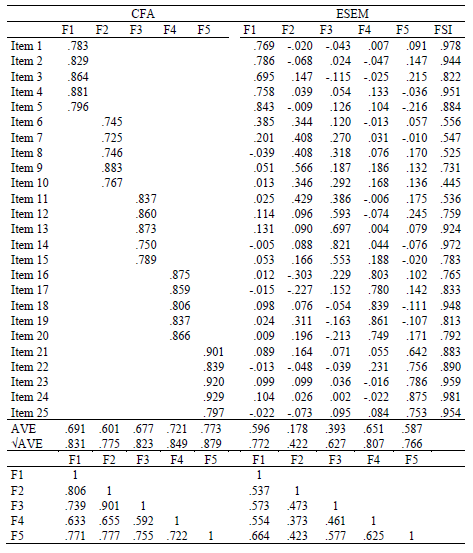

La evaluación del modelo de cinco factores brinda índices de ajuste favorables, tanto para el enfoque AFC (CFI = .959; RMSEA = .074; IC90 % .069, .079; WRMR = 1.217) como para el ESEM (CFI = .977; RMSEA = .067; IC90 % .061, .073; WRMR = 0.672), así como cargas factoriales adecuadas en su mayoría (> .50). No obstante, en el AFC se observa una elevada correlación interfactorial entre las dimensiones interacciones alumno-profesor e interacciones alumno-alumno (> .90), la que a su vez supera a la raíz de la VME de los dos factores, lo que indica ausencia de validez interna discriminante. Esta situación resalta en el análisis con el enfoque ESEM en el que cuatro de los cinco ítems de la dimensión interacciones alumno-profesor presentan complejidad factorial, ya que la dimensión interacciones alumno-alumno también los influye significativamente, y el ítem seis (“En los cursos, los profesores han sido miembros activos de los grupos de discusión que ofrecen dirección a nuestras discusiones”) tiene complejidad factorial con la dimensión interacciones alumno-contenido (Tabla 2). En ese caso, se fusionaron las dimensiones implicadas y se analizaron nuevamente mediante ESEM.

Tabla 2: AFC y ESEM de la Student Satisfaction Survey: cinco factores

Nota: F1: interacciones alumno-contenido; F2: interacciones alumno-profesor; F3: interacciones alumno-alumno; F4: interacciones alumno-tecnología; F5: satisfacción general; ISF: Índice de Simplicidad Factorial; VME: Varianza media extraída.

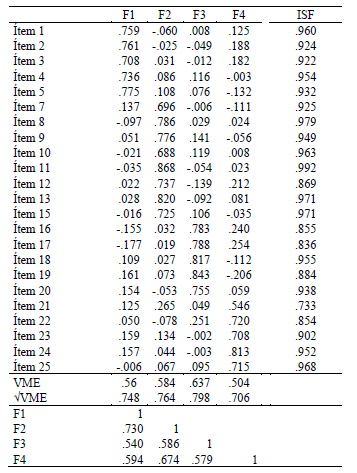

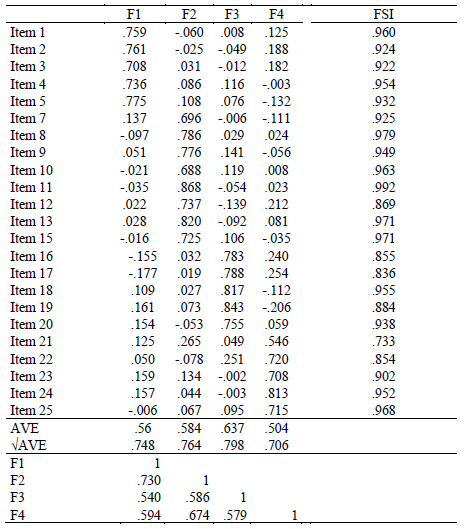

De este modo, el ajuste del modelo de cuatro dimensiones fue adecuado (CFI = .962; RMSEA = .081; IC90 % .075, .087; WRMR = 0.895), aunque el ítem 6 mantuvo la complejidad con la dimensión interacciones alumno-contenido, y el ítem 14 (“En los cursos he recibido comentarios oportunos de otros estudiantes”) se constituyó como un caso Heywood (λ > 1). Al eliminar los dos ítems mencionados el ajuste mejoró (CFI = .968; RMSEA = .081, IC90 % .075, .088; WRMR = 0.849), se observaron cargas factoriales adecuadas (λ > .60), simplicidad factorial suficiente (ISF > .70), validez interna convergente (VME > .50) y validez interna discriminante (√VME > ϕ) (Tabla 3).

Tabla 3: ESEM y confiabilidad de la Student Satisfaction Survey: cuatro factores

Nota: F1: interacciones alumno-contenido (ítems 1-5); F2: interacciones con alumnos y profesores (ítems 7-13, 15); F3: interacciones alumno-tecnología (ítems 16-20); F4: satisfacción general (ítems 21-25); ISF: Índice de Simplicidad Factorial; VME: Varianza media extraída.

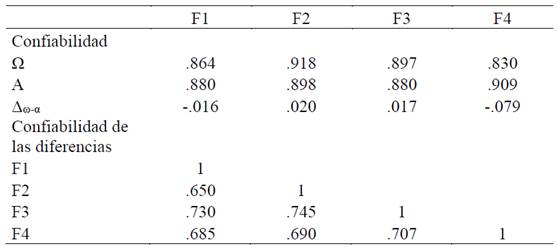

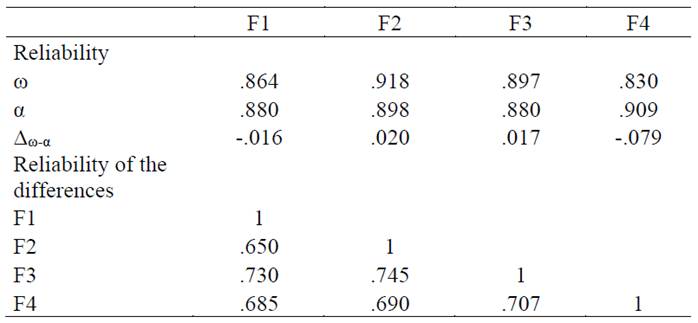

En cuanto a la confiabilidad, se aprecian magnitudes aceptables (> .80), mientras que la confiabilidad de las diferencias indica que el perfil resultante de la evaluación con la SSS es interpretable (Tabla 4).

Tabla 4: Confiabilidad de la Student Satisfaction Survey: cuatro factores

Nota: F1: interacciones alumno-contenido; F2: interacciones con alumnos y profesores; F3: interacciones alumno-tecnología; F4: satisfacción general; ω: coeficiente omega; α: coeficiente alfa.

Discusión

Considerando que la enseñanza online en el entorno universitario es cada vez más frecuente, la medición de la satisfacción del estudiante surge como una tarea prioritaria para valorar la efectividad de estos procesos formativos, ya que se trata de un constructo complejo que involucra muchos factores, como la comunicación, la participación de los estudiantes en debates online, la flexibilidad, la carga de trabajo, el apoyo tecnológico, las habilidades pedagógicas del profesor, etc. Por tanto, es crucial contar con instrumentos de medida adecuados a cada contexto cultural para medirlo. Por ello el objetivo de esta investigación fue analizar la estructura interna y confiabilidad de la Student Satisfaction Survey en estudiantes universitarios peruanos.

Si bien el análisis realizado a la estructura interna de la SSS indica que la mayoría de las dimensiones son robustas, se sugiere una superposición entre las dimensiones originales denominadas interacciones alumno-profesor e interacciones alumno-alumno, tanto con el AFC, al presentar una correlación interfactorial elevada, como con el ESEM, debido a la elevada complejidad factorial observada. Esto implica que las interacciones con los docentes y con los estudiantes se perciben como parte de la misma situación, es decir, como una interacción dentro del contexto de la clase, lo cual apoya una experiencia satisfactoria con los contenidos (Kuo et al., 2014), así un sentido de comunidad entre los estudiantes (Shackelford & Maxwell, 2012), debido a la importancia de la interacción entre los actores de la clase (alumnos y profesor) en las clases en línea (Ekwunife-Orakwue & Teng, 2014).

A pesar de la escasez de estudios que exploren las propiedades psicométricas de la SSS en países de habla hispana, los resultados hallados son comparables con los de Torrado y Blanca (2022), en el que se encontró evidencia favorable para el modelo de cinco factores, aunque no se reportan algunos indicadores importantes que informan sobre la diferenciación de los factores, como los valores de las correlaciones interfactoriales y los valores de las VME. En todo caso, los hallazgos del presente estudio se corresponden con la forma en cómo se manifiestan los tipos de interacción en la educación online síncrona y pueden ser interpretados desde la teoría de la distancia transaccional (Moore, 1993, 1997, 2007). En efecto, la interacción que ocurre entre los estudiantes en la enseñanza online es distinta de la que ocurre en la presencial (Thurmond & Wambach, 2004), sobre todo, en la modalidad sincrónica, en la que dicha interacción depende en gran medida de la interacción alumno-profesor; ya que el trabajo en equipo se llevará a cabo siempre que el docente desarrolle una metodología didáctica que promueva el aprendizaje colaborativo, que brinde oportunidades para que los estudiantes intercambien información para la realización de tareas académicas y fomentando un sentido de comunidad de aprendizaje (Alqurashi, 2019; Basith et al., 2020; Shackelford & Maxwell, 2012; Thurmond & Wambach, 2004). Por otro lado, a diferencia de lo que sucede en un aula presencial, la interacción alumno-profesor en el entorno virtual deja de ser el centro del escenario y el instructor se convierte en un facilitador del aprendizaje, de ahí que las interacciones entre los estudiantes y la interacción con el instructor sean percibidas como parte de un mismo componente. Estudios previos ya han señalado como estos dos tipos de interacción se diferencian de otros porque fortalecen significativamente el sentido de pertenencia de los alumnos con su comunidad de aprendizaje (Luo et al., 2017).

Asimismo, durante el proceso de análisis de la estructura interna de la SSS se eliminaron dos ítems. El primero fue el ítem 6 (“En los cursos, los profesores han sido miembros activos de los grupos de discusión que ofrecen dirección a nuestras discusiones”), probablemente porque debido a la migración a los entornos virtuales y la predominancia de las clases online, el número de estudiantes por aula se duplicó o triplicó lo que habría impedido una atención más personalizada por parte de los docentes. Por su parte, el ítem 14 (“En los cursos he recibido comentarios oportunos de otros estudiantes”) probablemente no sea representativo debido a que actualmente existen otros medios para comunicarse con los demás estudiantes (e.g., redes sociales), a diferencia del tiempo en el que se creó la escala en el que la comunicación entre estudiantes se enfocaba en la plataforma empleada por la institución o la clase sincrónica.

Sobre la confiabilidad, los coeficientes alfa y omega alcanzaron valores adecuados (Hunsley & Marsh, 2008; Ponterotto & Charter, 2009), por lo que se sugiere que la SSS es un instrumento confiable, tal como fue reportado en estudios previos que evalúan la satisfacción con la enseñanza online (Strachota, 2006; Torrado & Blanca, 2022). Además, la confiabilidad de la diferencia entre dos puntuaciones brinda evidencias de que la SSS puede configurar un perfil integrado de valoración de la satisfacción con la enseñanza y no solo informar de forma separada sobre cada dimensión del constructo (Dominguez-Lara, 2018b).

En cuanto a las implicancias prácticas del estudio, la SSS puede usarse para la medición de la satisfacción de los estudiantes que cursan estudios en modalidad online y con base en los resultados se puede contar con información útil sobre las fortalezas y debilidades de dichos programas formativos, de manera tal que se puedan implementar pautas y estrategias de mejora que propicien un entorno óptimo de aprendizaje. De la misma forma, los puntajes derivados de la SSS podrán ser considerados como indicadores de la efectividad de los cursos online, brindando mayor información para la toma de decisiones de los gestores educativos (Chen & Tat Yao, 2016; Palmer & Holt, 2009).

Con todo, a pesar de las implicancias y fortalezas del presente estudio, no está exento de algunas limitaciones. En primer lugar, el tipo de muestreo fue por conveniencia, por ello los resultados pueden no ser representativos de toda la población. En segundo lugar, el estudio se limitó a la respuesta de la escala autoinforme, lo que podría plantear problemas potenciales relacionados con el sesgo de deseabilidad social, pero al tratarse de una evaluación anónima y online, es probable que dicho sesgo se atenúe (Larson, 2018). En tercer lugar, el escalamiento de los ítems en cuatro opciones de respuesta podría ser revisado en estudios posteriores, dado que en ocasiones podría afectar las propiedades psicométricas (Donnellan et al., 2023). Finalmente, no se evaluó la validez convergente y predictiva de la escala. A pesar de estas limitaciones, el estudio proporciona una base psicométrica respecto a la estructura interna de la SSS para una adecuada medición de la satisfacción con la enseñanza online.

De este modo, se recomienda replicar el estudio para explorar si las dimensiones originales que reflejan la interacción entre alumnos y profesores realmente son redundantes, y analizar si el número de opciones propuesto por la autora original (cuatro) brinda mejores parámetros psicométricos que otro número de alternativas. Asimismo, se recomienda que futuras investigaciones utilicen técnicas de muestreo probabilístico para obtener una estimación más precisa. Estudios futuros deben examinar la asociación de la SSS con otras variables con el objetivo de ampliar las evidencias de validez.

Se concluye que la SSS presenta una estructura de cuatro dimensiones e indicadores adecuados de confiabilidad.

Referencias:

Alqurashi, E. (2019). Predicting student satisfaction and perceived learning within online learning environments. Distance Education, 40(1), 133-148. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2018.1553562

Álvarez, M., Gardyn, N., Iardelevsky, A., & Rebello, G. (2020). Segregación educativa en tiempos de pandemia: Balance de las acciones iniciales durante el aislamiento social por el Covid-19 en Argentina. Revista Internacional de Educación para la Justicia Social, 9(3), 25-43.

Amir, L. R., Tanti, I., Maharani, D. A., Wimardhani, Y. S., Julia, V., Sulijaya, B., & Puspitawati, R. (2020). Student perspective of classroom and distance learning during COVID-19 pandemic in the undergraduate dental study program Universitas Indonesia. BMC Medical Education, 20(1), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-020-02312-0

Asparouhov, T., & Muthén, B. O. (2009). Exploratory structural equation modeling. Structural Equation Modeling, 16(3), 397-438. http://doi.org/10.1080/10705510903008204

Asparouhov, T., Muthen, B., & Morin, A. J. S. (2015). Bayesian structural equation modeling with cross-loadings and residual covariances. Journal of Management, 41(6), 1561-1577. http://doi.org/10.1177/0149206315591075

Ato, M., López-García, J. J., & Benavente, A. (2013). Un sistema de clasificación de los diseños de investigación en psicología. Anales de Psicología, 29(3), 1038-1059. https://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.29.3.178511

Basith, A., Rosmaiyadi, R., Triani, S. N., & Fitri, F. (2020). Investigation of online learning satisfaction during COVID 19: In relation to academic achievement. Journal of Educational Science and Technology, 6, 265-275. https://doi.org/10.26858/est.v1i1.14803

Baturay, M. H. (2011). Relationships among sense of classroom community, perceived cognitive learning and satisfaction of students at an e-learning course. Interactive Learning Environments, 19(5), 563-575. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494821003644029

Benites, R. (2021). La educación superior universitaria en el Perú post-pandemia. Políticas y Debates públicos. https://repositorio.pucp.edu.pe/index/handle/123456789/176597

Bernard, R. M., Abrami, P. C., Borokhovski, E., Wade, C. A., Tamim, R. M., Surkes, M. A., & Bethel, E. C. (2009). A meta-analysis of three types of interaction treatments in distance education. Review of Educational Research, 79(3), 1243-1289. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654309333844

Best, B., & Conceição, S. C. O. (2017). Transactional distance dialogic interactions and student satisfaction in a multi-institutional blended learning environment. European Journal of Open, Distance and e-Learning, 20(1), 138-152.

Brown, T. A. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research (2a ed.). Guilford Press.

Browne, M. W., & Cudeck, R. (1993). Alternative ways of assessing model fit. En K. A. Bollen & J. S. Long (Eds.), Testing structural equation models (pp. 445-455). Sage.

Chen, W. S., & Tat Yao, A. Y. (2016). An empirical evaluation of critical factors influencing learner satisfaction in blended learning: a pilot study. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 4(7), 1667-1671. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2016.040719

Chung, E., Subramaniam, G., & Dass, L. C. (2020). Online learning readiness among university students in Malaysia amidst COVID19. Asian Journal of University Education, 16(2), 46-58.

Díaz, V. M., Urbano, E. R., & Berea, G. M. (2013). Ventajas e inconvenientes de la formación online. Revista Digital de Investigación en Docencia Universitaria, 7(1), 33-43. https://doi.org/10.19083/ridu.7.185

DiStefano, C., Liu, J., Jiang, N., & Shi, D. (2018). Examination of the weighted root mean square residual: Evidence for trustworthiness? Structural Equation Modeling: A Multidisciplinary Journal, 25(3), 453-466. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705511.2017.1390394

Dominguez-Lara, S. (2018a). Propuesta de puntos de corte para cargas factoriales: una perspectiva de confiabilidad de constructo. Enfermería Clínica, 28(6), 401-402. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.enfcli.2018.06.002

Dominguez-Lara, S. (2018b). Reporte de las diferencias confiables en el perfil del ACE-III. Neurología, 33(2), 138-139. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.nrl.2016.02.022

Dominguez-Lara, S., Gravini-Donado, M., Moreta-Herrera, R., Quistgaard-Alvarez, A., Barboza-Zelada, L. A., & De Taboada, L. (2022). Propiedades psicométricas del Student Adaptation to College Questionnaire - Educación Remota en estudiantes universitarios de primer año durante la pandemia. Campus Virtuales, 11(1), 81-93. https://doi.org/10.54988/cv.2022.1.965

Donnellan, M. B., & Rakhshani, A. (2023). How does the number of response options impact the psychometric properties of the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale? Assessment, 30(6), 1737-1749. https://doi.org/10.1177/10731911221119532

Ekwunife-Orakwue, K. C., & Teng, T. L. (2014). The impact of transactional distance dialogic interactions on student learning outcomes in online and blended environments. Computers & Education, 78, 414-427. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.06.011

Eryilmaz, M. (2015). The effectiveness of blended learning environments. Contemporary Issues in Education Research, 8(4), 251-256. https://doi.org/10.19030/cier.v8i4.9433

Etikan, I. (2016). Comparison of Convenience Sampling and Purposive Sampling. American Journal of Theoretical and Applied Statistics, 5(1), 1. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ajtas.20160501.11

Gignac, G. E., Bates, T. C., & Jang, K. (2007). Implications relevant to CFA model misfit, reliability, and the Five Factor Model as measured by the NEO-FFI. Personality and Individual Differences, 43(5), 1051-1062. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.02.024

Gravetter, F., & Wallnau, L. (2014). Essentials of Statistics for the Behavioral Sciences. Wadsworth.

Gravini-Donado, M. L., Mercado-Peñaloza, M., & Dominguez-Lara, S. (2021). College Adaptation Among Colombian Freshmen Students: Internal Structure of the Student Adaptation to College Questionnaire (SACQ). Journal of New Approaches in Educational Research, 10(2), 251-263. http://doi.org/ 10.7821/naer.2021.7.657

Hanna, D. E., Glowacki-Dudka, M., & Runlee, S. (2000). 147 practical tips for teaching online groups. Atwood.

Hanson, J., Bangert, A., & Ruff, W. (2016). A validation study of the what’s my school mindset? Survey. Journal of Educational Issues, 2(2), 244-266.

Hunsley, J., & Marsh, E. J. (2008). Developing criteria for evidence-based assessment: An introduction to assessment that work. En J. Hunsley & E. J. Marsh (Eds.), A guide to assessments that work (pp. 3-14). Oxford University Press.

Jan, S. K. (2015). The relationships between academic self-efficacy, computer self-efficacy, prior experience, and satisfaction with online learning. American Journal of Distance Education, 29(1), 30-40. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2015.994366

Kang, D., & Park, M. J. (2022). Interaction and online courses for satisfactory university learning during the COVID-19 pandemic. The International Journal of Management Education, 20(3), 100678. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2022.100678

Khan, J., & Iqbal, M. J. (2016). Relationship between student satisfaction and academic achievement in distance education: a case study of AIOU Islamabad. FWU Journal of Social Sciences, 10(2), 137-145.

Kong, S. C., Looi, C. K., Chan, T. W., & Huang, R. (2017). Teacher development in Singapore, Hong Kong, Taiwan, and Beijing for e-learning in school education. Journal of Computers in Education, 4(1), 5-25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40692-016-0062-5

Kuo, Y. C. (2014). Accelerated online learning: Perceptions of interaction and learning outcomes among African American students. American Journal of Distance Education, 28(4), 241–252. https://doi.org/10.1080/08923647.2014.959334

Kuo, Y. C., Belland, B. R., Schroder, K. E., & Walker, A. E. (2014). K-12 teachers’ perceptions of and their satisfaction with interaction type in blended learning environments. Distance Education, 35(3), 360-381. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2015.955265

Kuo, Y. C., Walker, A. E., Belland, B. R., & Schroder, K. E. E. (2013). A predictive study of student satisfaction in online education programs. International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 14(1), 16-39. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v14i1.1338

Lara, L., Monje, M. F., Fuster-Villaseca, J., & Dominguez-Lara, S. (2021). Adaptación y validación del Big Five Inventory para estudiantes universitarios chilenos. Revista Mexicana de Psicología, 38(2), 83-94.

Larson, R. B. (2018). Controlling social desirability bias. International Journal of Market Research, 61(5), 534-547. http://doi.org/10.1177/1470785318805305

Li, C. (2016a). Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behavioral Research Methods, 48, 936-949. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-015-0619-7

Li, C. (2016b). The performance of ML, DWLS, and ULS estimation with robust corrections in structural equation models with ordinal variables. Psychological Methods, 21(3), 369-387. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000093

Lloret-Segura, S., Ferreres-Traver, A., Hernández-Baeza, A., & Tomás-Marco, I. (2014). El análisis factorial exploratorio de los ítems: una guía práctica, revisada y actualizada. Anales de psicología, 30(3), 1151-1169. http://doi.org/10.6018/analesps.30.3.199361

Luo, N., Zhang, M., & Qi, D. (2017). Effects of different interactions on students’ sense of community in e-learning environment. Computers & Education, 115, 153-160. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2017.08.006

Magadán-Díaz, M., & Rivas-García, J. I. (2022). Gamificación del aula en la enseñanza superior online: el uso de Kahoot. Campus Virtuales, 11(1), 137-152. https://doi.org/10.54988/cv.2022.1.978

Marsh, H. W., Morin, A. J. S., Parker, P. D., & Kaur, G. (2014). Exploratory structural equation modeling: An integration of the best features of exploratory and confirmatory factor analysis. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 10(1), 85-110. http://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-032813-153700

Martín-Rodríguez, Ó., Fernández-Molina, J. C., Montero-Alonso, M. Á., & González-Gómez, F. (2015). The main components of satisfaction with e-learning. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 24(2), 267-277. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939X.2014.888370

Mbwesa, J. K. (2014). Transactional distance as a predictor of perceived learner satisfaction in distance learning courses: A case study of bachelor of education arts program, University of Nairobi, Kenya. Journal of Education and Training Studies, 2(2), 176-188. https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v2i2.291

McDonald, R. P., & Ho, M.-H. R. (2002). Principles and practice in reporting structural equation analyses. Psychological Methods, 7(1), 64-82. https://doi.org10.1037/1082-989X.7.1.64

Mohamed, E., Ghaleb, A., & Abokresha, S. (2021). Satisfaction with online learning among Sohag University students. Journal of High Institute of Public Health, 51(2), 84-89. https://doi.org/10.21608/jhiph.2021.193888

Moore, M. (1993). Three types of interaction. En K. Harry, M. John & D. Keegan (Eds.), Distance education theory (pp. 19-24). Routledge.

Moore, M. G. (1997). Theory of transactional distance. En D. Keegan (Ed.), Theoretical Principles of Distance Education (pp. 22-38). Routledge.

Moore, M. G. (2007). Theory of transactional distance. En M. G. Moore (Ed.). Handbook of distance education (pp. 89-101). Lawrence Erlbaum.

Moore, M., & Kearsley, G. (2005). Distance education: A system view. Thomson-Wadsworth.

Moreta-Herrera, R., Vaca-Quintana, D., Quistgaard-Álvarez, A., Merlyn-Sacoto, M.-F., & Dominguez-Lara, S. (2022). Análisis psicométrico de la Escala de Cansancio Emocional en estudiantes universitarios ecuatorianos durante el brote de COVID-19. Ciencias Psicológicas, 16(1), e-2755. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v16i1.2755

Muñiz, J. (2003). Teoría clásica de los tests. Pirámide.

Muñiz, J., Elosua, P., & Hambleton, R. K. (2013). Directrices para la traducción y adaptación de los test: segunda edición. Psicothema, 25(2), 151-157. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2013.24

Muthén, L. K., & Muthén, B.O. (1998-2015). Mplus User’s Guide. Muthén & Muthén.

Nortvig, A. M., Petersen, A. K., & Balle, S. H. (2018). A Literature review of the factors influencing e‑learning and blended learning in relation to learning outcome, student satisfaction and engagement. Electronic Journal of E-learning, 16(1), 46-55.

Oliver, R. L. (1980). A cognitive model of the antecedents and consequences of satisfaction decision. Journal of Marketing Research, 17(4), 460-469. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378001700405

Onditi, E. O., & Wechuli, T. W. (2017). Service quality and student satisfaction in higher education institutions: A review of literature. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 7(7), 328-335.

Palloff, R. M., & Pratt, K. (2001). Lessons from the cyberspace classroom. The realities of online teaching. Jossey-Bass.

Palmer, S. R., & Holt, D. M. (2009). Examining student satisfaction with wholly online learning. Journal of Computer Assisted Learning, 25(2), 101-113. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2008.00294.x

Pérez-Gil, J. A., Chacón, S. & Moreno, R. (2000). Validez de constructo: el uso de análisis factorial exploratorio-confirmatorio para obtener evidencias de validez. Psicothema, 12, 442-446.

Pham, L., Limbu, Y. B., Bui, T. K., Nguyen, H. T., & Pham, H. T. (2019). Does e-learning service quality influence e-learning student satisfaction and loyalty? Evidence from Vietnam. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 16(1), 1-26. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41239-019-0136-3

Ponterotto, J., & Charter, R. (2009). Statistical extensions of Ponterotto and Ruckdeschel’s (2007) reliability matrix for estimating the adequacy of internal consistency coefficients. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 108(3), 878-886. https://doi.org/10.2466/PMS.108.3.878-886

Ramo, N. L., Lin, M. A., Hald, E. S., & Huang-Saad, A. (2021). Synchronous vs. asynchronous vs. blended remote delivery of introduction to biomechanics course. Biomedical Engineering Education, 1, 61-66. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43683-020-00009-w

Rubia, J. M. (2019). Revisión de los criterios para validez convergente estimada a través de la VarianRubiaza Media Extraída. Psychologia, 13(2), 25-41. https://doi.org/10.21500/19002386.4119

Sánchez-González, M., & Castro-Higueras, A. (2022). Mentorías para profesorado universitario ante la Covid-19: evaluación de un caso. Campus Virtuales, 11(1), 181-200. https://doi.org/10.54988/cv.2022.1.1000

Shackelford, J. L., & Maxwell, M. (2012). Sense of community in graduate online education: Contribution of learner to learner interaction. The International Review of Research in Open and Distributed Learning, 13(4), 228-249. https://doi.org/10.19173/irrodl.v13i4.1339

Strachota, E. (2003). Student satisfaction in online course: An analysis of the impact of learner-content, learner-instructor, learner-learner and learner-technology interaction (Disertación doctoral). University of Wisconsin- Milwaukee.

Strachota, E. (2006). The use of survey research to measure student satisfaction in online courses. University of Missouri-St. Louis.

Teo, T. (2010). A structural equation modelling of factors influencing student teachers’ satisfaction with e-learning. British Journal of Educational Technology, 41(6), 150-152. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2010.01110.x

Thurmond, V., & Wambach, K. (2004). Understanding interactions in distance education: A review of the literature. International Journal of Instructional Technology and Distance Learning, 1(1), 9-26.

Torrado, M., & Blanca, M. J. (2022). Assessing satisfaction with online courses: Spanish version of the Learner Satisfaction Survey. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 875929. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.875929

Vásquez-Pajuelo, L. (2019). Aprendizaje online: satisfacción de los universitarios con experiencia laboral. Review of Global Management, 5(2), 28-43. https://doi.org/10.19083/rgm.v5i2.1234

Vergara-Morales, J., Rodríguez-Vera, M., & Del Valle, M. (2022). Evaluación de las propiedades psicométricas del Cuestionario de Autorregulación Académica (SRQ-A) en estudiantes universitarios chilenos. Ciencias Psicológicas, 16(2), e-2837. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v16i2.2837

Watermeyer, R., Crick, T., Knight, C., & Goodall, J. (2020). COVID-19 and digital disruption in UK universities: afflictions and affordances of emergency online migration. Higher Education, 81(3), 623-641. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00561-y

Waters, S., & Russell, W. (2016). Virtually ready? Pre-service teachers’ perceptions of a virtual internship experience. Research in Social Sciences and Technology, 1(1), 1-23.

Wei, H. C., Peng, H., & Chou, C. (2015). Can more interactivity improve learning achievement in an online course? Effects of college students’ perception and actual use of a course-management system on their learning achievement. Computers & Education, 83, 10-21. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2014.12.013

West, S. G., Taylor, A. B., & Wu, W. (2012). Model fit and model selection in structural equation modeling. En R. H. Hoyle (Ed.), Handbook of Structural Equation Modeling (pp. 209-231). Guilford.

Ye, J-H., Lee, Y-S., & He, Z. (2022). The relationship among expectancy belief, course satisfaction, learning effectiveness, and continuance intention in online courses of vocational-technical teachers college students. Frontiers in Psychology, 13, 904319. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.904319

Yılmaz, A., & Karataş, S. (2017). Development and validation of perceptions of online interaction scale. Interactive Learning Environments, 26(3), 337-354. http://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2017.1333009

Disponibilidad de datos: El conjunto de datos que apoya los resultados de este estudio no se encuentra disponible.

Cómo citar: Manrique-Millones, D., Lingán-Huamán, S. K., & Dominguez-Lara, S. (2023). Satisfacción con la enseñanza online en estudiantes universitarios: análisis estructural de una escala. Ciencias Psicológicas, 17(2), e-3193. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i2.3193

Contribución de los autores: a) Concepción y diseño del trabajo; b) Adquisición de datos; c) Análisis e interpretación de datos; d) Redacción del manuscrito; e) revisión crítica del manuscrito.

D. M. M. ha contribuido con a, b, d, e; S. K. L. H. con a, c, d, e; S. D. L. con a, b, c, d, e.

Editora científica responsable: Dra. Cecilia Cracco.

10.22235/cp.v17i2.3193

Original Articles

Satisfaction with online teaching in university students: Structural analysis of a scale

Satisfacción con la enseñanza online en estudiantes universitarios: análisis estructural de una escala

Satisfação com o ensino online em universitários: Análise estrutural de uma escala

Denisse Manrique-Millones1, ORCID 0000-0003-4602-5396

Susana K. Lingán-Huamán2, ORCID 0000-0003-4587-7853

Sergio Dominguez-Lara3, ORCID 0000-0002-2083-4278

1 Universidad Científica del Sur, Peru

2 Universidad San Ignacio de Loyola, Peru

3 Universidad Privada Norbert Wiener, Peru, [email protected]

Abstract:

The aim of this research study was to analyze the internal structure and reliability of the Student Satisfaction Survey (SSS) in Peruvian university students. A total of 458 students participated (women = 69.9 %; Mage = 27.76 years; SDage = 4.41 years). The SSS was studied under confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM). Regard the results, the original five-dimensional model obtained favorable fit indexes with ESEM, but the dimensions student-teacher interactions and student-student interactions overlap each other, so it was valued as a four-dimensional model that presented better psychometric evidence. Regarding reliability, an acceptable order of magnitudes was observed, both at the level of scores and construct. It can be concluded that the SSS has adequate psychometric properties.

Keywords: satisfaction with online teaching; higher education; distance education; validity; reliability.

Resumen:

El objetivo de esta investigación fue analizar la estructura interna y confiabilidad de la Student Satisfaction Survey (SSS) en estudiantes universitarios peruanos. Participaron 458 estudiantes (mujeres = 69.9 %; Medad = 27.76 años; DEedad = 4.41 años). La SSS se estudió bajo el análisis factorial confirmatorio (AFC) y el modelamiento exploratorio de ecuaciones estructurales (ESEM). Respecto a los resultados, el modelo original de cinco dimensiones obtuvo índices de ajuste favorables con ESEM, pero las dimensiones interacciones alumno-profesor e interacciones alumno-alumno se superponen entre sí, por lo que se valoró un modelo de cuatro dimensiones que presentó mejores evidencias psicométricas. La confiabilidad de las puntuaciones y de constructo presenta magnitudes aceptables. Se concluye que el SSS cuenta con propiedades psicométricas adecuadas.

Palabras clave: internacionalización; movilidad estudiantil; adultez emergente; identidad profesional.

Resumo:

O objetivo deste estudo foi analisar a estrutura interna e a confiabilidade da Student Satisfaction Survey (SSS) em estudantes universitários peruanos. Participaram 458 estudantes (mulheres = 69,9 %; Midade = 27,76 anos; DPidade = 4,41 anos). O SSS foi estudado por meio de análise fatorial confirmatória (CFA) e modelação exploratória de equações estruturais (ESEM). Quanto aos resultados, o modelo original de cinco dimensões obteve índices de ajuste favoráveis com ESEM, mas as interações entre as dimensões aluno-professor e aluno-aluno se sobrepõem, por isso, foi analisado um modelo quatro dimensões que apresentou melhor evidência psicométrica. A confiabilidade das pontuações e de construto apresentaram magnitudes aceitáveis. Conclui-se que o SSS possui propriedades psicométricas adequadas.

Palavras-chave: satisfação com ensino online; ensino superior; educação a distância; validade; confiabilidade.

Received: 31/01/2023

Accepted: 04/10/2023

The COVID-19 pandemic introduced abrupt changes in different areas of people's lives, and one of those that suffered the direct impact was the field of education. In this sense, the managers of educational institutions had to quickly adapt to the new demands to provide alternatives that guarantee the continuity of the educational processes. In this way, the online teaching modality was adopted by universities and all educational and administrative processes migrated to a digital interface.

Even before the pandemic, online teaching had already gradually gained greater prominence in the panorama of Peruvian higher education, in line with new pedagogical trends linked to the integration of information and communications technologies (TIC, in Spanish; Dominguez-Lara et al., 2022). However, doubts about the quality of the educational processes in online teaching were expressed through the results of the licensing and accreditation process of educational quality by the National Superintendence of Higher Education (SUNEDU, in Spanish), which is the governing body of evaluation of universities within the framework of the university reform in Peru. As a product of the aforementioned process, the operating license was denied to 48 out of the 140 universities that submitted to the evaluation process because they failed to demonstrate compliance with basic quality conditions (Benites, 2021), and many of these universities offered online teaching programs. In this way, the effects of the pandemic in the Peruvian educational field emerged in a context in which the university reform was underway and revealed a series of institutional problems, where online teaching was not a priority for higher education institutions.

In this scenario, universities faced many challenges for developing online education during the State of Health Emergency, and after it. Thus, some of the obstacles were related to the lack of access to technological devices or a stable internet connection by students and professors (Álvarez et al., 2020), while other limitations were associated with the skills required to the educational actors. On the one hand, the students were required to assume a more active and autonomous role in their own learning process, which, combined with the stress of a pandemic context, made them more emotionally vulnerable (Moreta-Herrera et al., 2022); and on the other hand, professors were forced to use and master TIC quickly, integrating them into their instructional activities after a brief training, and sometimes intuitively.

Despite these drawbacks, the effects of the pandemic made it possible to reflect on new ways of learning and teaching, in line with technological advances, and identifying a valuable opportunity for pedagogical reinvention and modernization of the university (Watermeyer et al., 2020). All this because many university students prefer online education motivated by the facilities it offers when articulating academic, work and family life (Waters & Russell, 2016), being an effective mechanism to shorten the gaps in access to higher education. (Kong et al., 2017). Therefore, universities must generate quality online education proposals and prepare students and their professors for a world integrated with technology (Sánchez-González & Castro-Higueras, 2022), given that blended learning (b-learning) combines both aspects, that is, face-to-face and online activities (Eryilmaz, 2015).

In this scenario, it is important to know the perspective of the university students since it has been shown that the success of an online education program is associated with their satisfaction (Kang & Park, 2022; Pham et al., 2019; Teo, 2010). This aspect is crucial to effective learning and is directly related to academic performance, retention, motivation and commitment to learning (Basith et al., 2020; Pham et al., 2019; Teo, 2010; Ye et al., 2022), aspects which, in turn, are associated with greater student autonomy (Vergara-Morales et al., 2022). For this reason, educational managers have the obligation to systematically evaluate learners’ satisfaction with educational processes as it is known that the university is an environment that generates various challenges for the student, whether at an academic, social, emotional and institutional level (Gravini-Donado et al., 2021).

From a classical perspective, user satisfaction is defined as an indicator of the distance between a comparison standard and the perceived performance of the good or service being evaluated (Oliver, 1980). In the academic field, student satisfaction refers to the value judgment about the fulfillment of their expectations, needs and demands during their educational experience (Bernard et al., 2009), although it has also been defined as the short-term attitude that is produced by the evaluation of your experience with the educational service received (Onditi & Wechuli, 2017).

Therefore, the study of student satisfaction in online learning environments is of growing interest because it influences the effectiveness of teaching and the development of instructional materials (Khan & Iqbal, 2016), mainly because its dynamics are different from that of face-to-face learning and must be valued according to those characteristics. Considering this will allow us to have useful information to design new online subjects and guide the improvement of teaching performance, as well as the learning content and the general quality of academic programs. This is relevant because, despite the advantages of online teaching (elimination of physical distances, time flexibility, among others), some limitations were identified (interpersonal communication problems, little cooperation from professors or virtual tutors, absence of direct contact, among others) that make it difficult for students to adapt (Díaz et al., 2013) and, consequently, harm academic performance and encourage dropout.

Similarly to face-to-face education, online education, is based on the interactive processes between participants. Thus, Moore and Kearsley (2005) point out that the effectiveness of teaching-learning will depend on the nature of this interaction and how it could be favored through a technological means (Moore, 2007). In this way, Moore (1993, 1997) describes a set of relations that also appear in online education when students and professors are distanced by space and time, highlighting three types of interactions for effective learning.

The first interaction is learner-content, referring to the students’ relations with the contents of the modules or learning units, the lessons and learning activities of the subjects, including readings, projects, videos, websites, among others, which lead to changes in understanding, perception and cognitive structure and significantly influence satisfaction with online teaching (Kuo, 2014).

The second interaction is learner-instructor, which implies a bidirectional relation between the student and the instructor whose function is to receive and give feedback, clarifying content and clearing doubts through fluid communication that facilitates and motivates learning (Yılmaz & Karataş, 2017), and is a significant predictor of satisfaction in synchronous classes (Kuo et al., 2014).

The third interaction is learner-learner, which refers to the bidirectional relation between students in order to share and learn cooperatively through different means such as discussion forums, emails or social networks, thus creating a collaboration between peers (Moore, 1993). This interaction is cognitive and social in nature and is important because it creates a sense of community (Shackelford & Maxwell, 2012) and enhances learning.

A fourth type of interaction is the so-called learner-technology interaction, proposed after the original three (Hanna et al., 2000; Palloff & Pratt, 2001), and refers to the communication between the student and the learning virtual environment, which implies knowing how to use virtual tools, as well as having the appropriate technological skills. This type of interaction focuses on the student's relations with the technological means and devices necessary to develop the educational program, considering aspects like the comfort and functionality of tools such as laptops, Internet, software or educational platforms, among others (Strachota, 2003).

The available evidence indicates that these types of interaction are relevant to student satisfaction and performance (Alqurashi, 2019; Basith et al., 2020; Kuo et al., 2013), highlighting some aspects associated with online teaching, such as: the design and content of the subjects, information accessibility on the virtual platform, the ease of interaction with the professor (Martín-Rodríguez et al., 2015), the interactions between students, administrative management and academic activities related to the procedural contents of the subjects (Nortvig et al., 2018). Furthermore, different studies emphasize students' preference for the synchronous modality of class delivery, which provides the opportunity to ask questions, debate and reflect in real time, complemented by asynchronous access to subject information and to the class recordings (Amir et al., 2020; Chung et al., 2020; Ramo et al., 2021).

According to the panorama presented, the evaluation of interactions in online learning environments and satisfaction with them is important, although the measurement instruments available present some flaws or methodological limitations that prevent valid and reliable use in certain aspects. For example, some instruments present only reliability reports (e.g., Baturay, 2011) and in other works this indicator is complemented only with expert opinion (e.g., Wei et al., 2015), but do not have an analysis of the internal structure of the instrument that allows the constructs to be differentiated from a factor-analytical perspective.

There are other instruments that do not present the procedural omissions of the previously mentioned studies. For example, a recently created scale (Yılmaz & Karataş, 2017) bases its hypothetical internal structure on Moore's approach (1993), but the methodological decisions in its construction are questionable since the use of principal components analysis overestimates the magnitude of factor loadings and deciding the number of factors using the Eigen value greater than unity criterion suggests extracting a greater than optimal number of factors (Lloret-Segura et al., 2014). Furthermore, the use of the same sample for both exploratory and confirmatory analysis is a not recommended practice because it provides inconclusive results (Pérez-Gil et al., 2000).

Another instrument available is the Student Satisfaction Survey (SSS; Strachota, 2003, 2006), which evaluates the dialogic components of interactions in the teaching-learning process based on the approaches of Moore and Kearsley (2005), complemented with the interaction between the learner and the technology and a dimension of general satisfaction. Among the advantages offered by the use of the SSS is that it can be applicable to all educational levels of higher education from a multidimensional theoretical perspective without including a large number of items. The SSS presents adequate psychometric properties, including validity evidence based on item content and an analysis of its internal structure through factor analysis, although under an exploratory approach.

Numerous works have used the SSS to directly measure dialogic interactions based on student satisfaction, both in online learning environments and in mixed environments (Mbwesa, 2014; Mohamed, 2021; Torrado & Blanca, 2022). For example, in research conducted with a university population in online and blended learning, it was measured how interactions in blended and online learning environments affected learning outcomes measured by student satisfaction and grades. The findings showed that the interaction that affected the learning results was the learner-content dyad, and the importance of the learner-instructor and learner-learner interaction in online learning environments was also highlighted (Ekwunife-Orakwue & Teng, 2014). In another study, the relations between academic self-efficacy, computer self-efficacy, previous experience and satisfaction with online learning were investigated, and a significant direct relation was found between academic self-efficacy and satisfaction with online learning (Jan, 2015). On the other hand, the influence of transactional dialogic interaction on learners’ satisfaction in a multi-institutional mixed learning environment was analyzed, and significantly positive effects of transactional interaction on satisfaction in mixed learning environments were found (Best & Conceição, 2017).

In this sense, the purpose of this work was to analyze the psychometric properties of the SSS in Peruvian university students in an online teaching context. On the one hand, the internal structure was examined using the exploratory structural equation modeling (ESEM) and on the other hand, the internal consistency of the scale was studied. This study is justified at a theoretical level because it will help understand the satisfaction structure with online teaching in Peruvian students given that the approach to this construct is emerging in Peru, and despite the fact that there are some pre-pandemic studies (e.g., Vásquez -Pajuelo, 2019), the psychometric properties of the instruments used are not clearly presented, which it does not allow satisfactory conclusions to be obtained. Likewise, at a practical level, institutions will be provided with an instrument that evaluates the dialogic interactions involved in the online teaching-learning process and that provides useful information on the areas that need to be improved through the design of learning environments that allow taking advantage of the available resources (Hanson et al., 2016; Magadán-Díaz & Rivas-García, 2022).

Finally, at a methodological level, although the validity evidence obtained in pioneering studies under an exploratory approach represents a good starting point (Strachota, 2003, 2006), it is necessary to analyze the scale under contemporary approaches that provide more information such as the ESEM (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2009). The ESEM provides the usual fit indices to evaluate the model in a similar way to the confirmatory factor analysis, but it also provides a complete estimate of the factor loadings (main and secondary ones) in the same way as the exploratory factor analysis, in addition to providing a more accurate estimate of the interfactor correlations (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2009), which would improve the understanding of this construct. However, although some works use confirmatory analysis (e.g., Yılmaz & Karataş, 2017), this approach assumes that the items only receive influence from their theoretical factor, leaving aside the other factors involved in the measurement model, which would represent an inconvenience when carrying out the analyzes (Marsh et al., 2014), since measures of complex constructs (such as satisfaction) usually have items with cross-loadings on other factors, and if they are not specified, even insignificant factor loadings (≈ .10) will negatively affect the model (Asparouhov et al., 2015).

Method

Design

This is an instrumental design (Ato et al., 2013) oriented to the analysis of psychometric properties of the Student Satisfaction Survey (Strachota, 2006).

Participants

458 Peruvian university students (69.9 % women; 31.1 % men) from various university degree courses of private institutions participated. The age ranged between 17 and 56 years old (M = 27.76; SD = 4.41), the majority were single (90.6 %), and more than half used the Internet more than 20 hours a week (52.2 %), while only 4.4 % did it less than five hours a week. The type of sampling was chosen for convenience since it considered accessibility and availability at a given time or the willingness to participate (Etikan, 2016) given the restrictions in force in Peru due to confinement during a health emergency.

Instrument

Student Satisfaction Survey (SSS; Strachota, 2006). This is a 25-item self-report scale with four response options (from completely disagree to completely agree) that evaluates general satisfaction with online teaching (e.g., “I would like to take other courses with the same learning environment”), as well as with different dimensions of interaction within that teaching context such as learner-content interactions (e.g., “The assignments or projects in those courses have facilitated my learning”), learner-instructor interactions (e.g., “I have received timely comments from my professors”) , learner-learner interactions (e.g., “In the courses I have been able to share my point of view with other students”), and learner-technology interactions (e.g., “Computers are of great help for learning”).

Procedure

The data was collected within the framework of a project focused on satisfaction with online education during the COVID-19 pandemic and was developed according to ethical recommendations of the American Psychological Association and the Declaration of Helsinki.

Authorization was requested from the creator to translate the instrument, which was done based on specialized literature (Muñiz et al., 2013). The first stage consisted of the translation from English to Spanish. It was then given to ten psychology students who assessed the clarity of the items and there were no problems understanding their content.

A Google forms link was sent to students between June and August 2021. The form contained the informed consent that had the title and description of the study, as well as the voluntary and anonymous nature of participation, which could be withdrawn whenever they wanted, and the confidential treatment of the data.

Data analysis

The five-factor original structure was analyzed using confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) and ESEM (Asparouhov & Muthén, 2009) because there are no studies that provide other measurement models. The analysis was carried out with the Mplus version 7 program (Muthén & Muthén, 1998-2015).

Skewness and kurtosis values between -2 and +2 would indicate a distribution approximate to the univariate normality of the items (Gravetter & Wallnau, 2014), and the multivariate normality with the Mardia coefficient (G2 < 70). Regarding the structural analysis, the WLSMV estimation method was used since it is oriented to ordinal items (Li, 2016a, 2016b), and based on the polychoric matrix correlation. The model analyzed with CFA and ESEM was assessed with the CFI (> .90; McDonald & Ho, 2002), the RMSEA (< .08; Browne & Cudeck, 1993), also considering the upper limit of its confidence interval (<. 10; West et al., 2012), and the WRMR (< 1; DiStefano et al., 2018). In the same way, in both the CFA and the ESEM, the convergent internal validity was analyzed with the average variance extracted (AVE > .37; Rubia, 2019) and with the magnitude of the factor loadings (λ >. 60; Dominguez-Lara, 2018a), as well as the discriminant internal validity if the square root of the AVE (√AVE) is greater than the interfactor correlation (ϕ) between two dimensions.

Regarding the CFA, interfactor correlations greater than .90 suggest factor redundancy (Brown, 2015). In relation to the ESEM, the oblique target rotation (ε = .05; Asparouhov & Muthén, 2009) was used, which freely estimates the main and secondary factor loadings, which were specified as close to zero (~0), to finally calculate the factor simplicity index (FSI) to assess its relevance. In that sense, an FSI above .70 is expected, which means that the item is influenced by a single factor (Lara et al., 2021).

On the other hand, the reliability of the scores (α > .70; Ponterotto & Charter, 2009) and of the construct (ω > .70; Hunsley & Marsh, 2008) was estimated, and whether the difference between coefficients is less than |. 06| (Δω-α) is not considered significant (Gignac et al., 2007). In this way, and given that it is desirable that the results of the SSS be configured as a profile, the reliability of the difference between two scores (ρd) was analyzed, which examines the degree to which the difference between two scores is explained more by the true variance than the error variance, so acceptable values (> .70) would indicate that the profile configuration provides relevant information (Dominguez-Lara, 2018b; Muñiz, 2003).

Results

The items present a magnitude of skewness and kurtosis that allow a reasonable approximation to univariate normality (Table 1), but not to multivariate normality (G2 = 291.775).

Table 1: Descriptive statistics of the items of the Student Satisfaction Survey

Note: M: Mean; SD: Standard Deviation; g1: skewness; g2: kurtosis.