10.22235/cp.v18i1.3178

Instrumentos para avaliação da agressividade de torcedores esportivos: uma revisão sistemática

Instruments for evaluation of aggressiveness in sports fans: a systematic review

Instrumentos

para evaluar la agresividad de los aficionados al deporte:

una revisión sistemática

Geovani Garcia Zeferino1, ORCID 0000-0002-8245-668X

Anna Clara Santos da Silva2, ORCID 0000-0002-0831-6793

Marcela Mansur-Alves3, ORCID 0000-0002-3961-3475

1 Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Brasil, [email protected]

2 Universidade Federal de São João del-Rei, Brasil

3 Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Brasil

Resumo:

O objetivo do estudo foi identificar instrumentos utilizados para avaliar a agressividade de torcedores esportivos e descrever suas características operacionais e psicométricas. Foi realizada uma revisão sistemática na literatura, seguindo diretrizes do PRISMA, nas bases de dados BVS, PsycINFO, PubMed/MedLine, Science Direct, Scopus e Web of Science, utilizando os descritores e operadores booleanos: scale OR test OR inventory OR questionnaire AND aggression OR violence OR aggressiveness AND spectators OR fans. Foram encontrados 198 estudos e após critérios de exclusão, restaram 15. Nesses estudos, foram identificados 11 instrumentos. Esses instrumentos, apresentaram diferenças em bases teóricas, número e conteúdo das dimensões, modo de administração e tipo de resposta. No intuito de verificar a robustez dos instrumentos, as evidências psicométricas foram pontuadas. As descobertas da presente revisão evidenciaram carência de instrumentos específicos para avaliar agressividade de torcedores e poderão auxiliar pesquisadores em possíveis criações de medidas com essa finalidade.

Palavras-chave: agressividade; torcedores; instrumentos de medida; avaliação; esportivos.

Abstract:

The aim of the study was to identify instruments used to assess the aggressiveness of sports fans and describe their operational and psychometric characteristics. A systematic literature review was carried out, following PRISMA guidelines, in the BVS, PsycINFO, PubMed/MedLine, Science Direct, Scopus and Web of Science databases, using the Boolean descriptors and operators: scale OR test OR inventory OR questionnaire AND aggression OR violence OR aggressiveness AND spectators OR fans. 198 studies were found and, after exclusion criteria, 15 remained. In these studies, 11 instruments were identified. These instruments showed differences in theoretical bases, number and content of dimensions, administration method and type of response. In order to verify the robustness of the instruments, the psychometric evidences were scored. The findings of the present review showed the lack of specific instruments to assess the aggressiveness of fans, which can help researchers in the potential creation of measures for this purpose.

Keywords: aggressiveness; fans; measurement instruments; assessment; sports.

Resumen:

El objetivo del estudio fue identificar instrumentos utilizados para evaluar la agresividad de los aficionados al deporte y describir sus características operativas y psicométricas. Se realizó una revisión sistemática de la literatura, siguiendo las pautas PRISMA, en las bases de datos BVS, PsycINFO, PubMed/MedLine, Science Direct, Scopus y Web of Science, utilizando los descriptores y operadores booleanos: escala OR test OR inventario OR cuestionario Y agresión OR violencia OR agresividad OR espectadores OR aficionados. Fueron encontrados 198 estudios y después de los criterios de exclusión quedaron 15. En ellos se identificados 11 instrumentos. Estos instrumentos mostraron diferencias en las bases teóricas, número y contenido de dimensiones, modo de administración y tipo de respuesta. Para verificar la robustez de los instrumentos, se puntuaron las evidencias psicométricas. Los hallazgos de la presente revisión mostraron la falta de instrumentos específicos para evaluar la agresividad de los fanáticos, que pueden ayudar a los investigadores en la posible creación de medidas para este propósito.

Palabras clave: agresividad; aficionados; instrumentos de medición; evaluación; deporte.

Recebido: 12/01/2023

Aceito: 21/12/2023

Especificamente no esporte, as agressões têm ocorrido em competições profissionais, amadoras, universitárias e juvenis (Lake, 2020) e em várias modalidades (Turğut et al., 2018). A agressividade é um construto que apresenta algumas definições distintas. De maneira geral, pode ser entendida como uma ação intencional que objetiva gerar dano a outra pessoa ou a si mesmo (Allen & Anderson, 2017), podendo ser manifestada de forma física, verbal, psicológica, dentre outras (Anderson & Huesmann, 2003). No contexto esportivo, a agressividade de torcedores é um fenômeno que ocorre no mundo todo (Brandão et al., 2020) e tem se tornado um fenômeno preocupante por gerar diversos prejuízos e consequências negativas (Murad, 2017).

Dentre os prejuízos e consequências mais citados, destacam-se os milhares óbitos e ferimentos, devido às brigas dos torcedores (Lake, 2020; Murad, 2017). Referente aos ferimentos, é constatado que há impactos na economia do Estado, pois os hospitais asseguram o atendimento necessário e medicamentos aos feridos, gerando despesas adicionais (Maciel et al., 2016). Além disso, na segurança pública, segundo Murad (2017), há policiais que também agem de forma agressiva, causando confrontos com torcedores. Sendo assim, os agentes também se ferem, são levados para hospitais públicos e, em alguns casos, são afastados de suas funções.

Outros impactos são vistos no lazer de alguns torcedores, que não vão ou reduziram as idas aos locais de competições (estádios, arenas, dentre outros) devido às confusões. Sendo assim, os clubes são prejudicados por diminuírem as vendas de ingressos (Toder-Alon et al., 2018). Ademais, atletas também são afetados, pois a pressão, cobrança excessiva e agressividade dos torcedores têm gerado redução no rendimento e, em alguns casos, transtornos mentais comuns, em decorrência dos altos níveis de ansiedade e estresse (Albino & Conde, 2019).

Diante do exposto, ressalta-se que a agressividade de torcedores tem gerado consequências negativas para os clubes, demais torcedores e sociedade (Lake, 2020; Murad, 2017). Assim sendo, instrumentos para avaliar a agressividade de torcedores são de extrema importância para identificar perfis agressivos e, posteriormente, pensar e promover alternativas para amenizar atos agressivos. Nesse sentido, Zeferino et al. (2021) destacaram a urgência de se discutir estratégias para reduzir essa agressividade, porém os autores alertaram a dificuldade em se mensurar a agressividade de torcedores, devido à carência de instrumentos específicos.

Ainda com relação aos instrumentos específicos para avaliar a agressividade de torcedores, vários estudos (Carriedo et al., 2020; Moore et al., 2007; Turğut et al., 2018; Zeferino et al., 2021) utilizaram instrumentos sem o foco em torcedores, como o Buss and Perry Aggression Questionnaire (Buss & Perry, 1992) e o Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (Buss & Durkee, 1957). Entretanto, isso se tornou uma preocupação, pelo fato de o uso generalizado de instrumentos desconsiderar as especificidades do esporte (Carriedo et al., 2020; Zeferino et al., 2021). Além disso, pontua-se a extrema importância de se utilizar instrumentos específicos e com normas para a população-alvo para eliminar vieses, devido às várias diferenças (p. ex.: culturais, de linguagem, dentre outras) que podem afetar os resultados (American Educational Research Association (AERA) et al., 2014), e desconsiderar as especificidades, comportamentos e realidade do contexto esportivo (Wachelke et al., 2008).

Diante do exposto, os objetivos deste estudo foram identificar, por meio de uma revisão sistemática, instrumentos utilizados para mensurar a agressividade de torcedores esportivos e analisar suas bases teóricas, características operacionais (p. ex.: quantidade e conteúdo das dimensões, população, número de itens e tipo de resposta) e evidências psicométricas.

Método

Foi realizada uma revisão sistemática da literatura seguindo diretrizes do Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA Statement; Moher et al., 2015) para sistematizar a revisão, objetivando reduzir vieses e aumentar a qualidade metodológica. Foram avaliadas características operacionais e psicométricas dos instrumentos revisados, baseado no estudo de Silva et al. (2018).

Busca e seleção dos instrumentos

As buscas foram realizadas nos indexadores BVS, PsycINFO, PubMed/MedLine, Science Direct, Scopus e Web of Science, com a seguinte combinação de descritores (apenas no idioma inglês) e operadores booleanos: scale OR test OR inventory OR questionnaire AND aggression OR violence OR aggressiveness AND spectators OR fans. Visando assegurar o rigor metodológico, houve uma consulta nos estudos dessa temática e em índices de palavras-chave, a saber: Descritores em Ciências da Saúde (DeCS) e Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) para a seleção dos descritores. Para cada uma das bases, a busca dos artigos foi realizada por dois pesquisadores de forma independente. Ademais, os pesquisadores fizeram o gerenciamento das referências por meio do EndNote Web®, disponível no site https://www.myendnoteweb.com.

Essas buscas ocorreram no dia 28 de dezembro de 2021, visando identificar estudos que utilizaram escalas, inventários, questionários, ou outras medidas para avaliar a agressividade de torcedores. Vale ressaltar que não foi delimitado o período de publicação dos estudos, visando aumentar o alcance. Houve, também, um rastreamento das sessões de referências dos artigos que preencheram os critérios de elegibilidade da revisão para identificar estudos adicionais que se encaixassem nos objetivos propostos e a inserção de critérios de inclusão e exclusão.

Diante disso, destaca-se que, os critérios de inclusão foram: (1) artigos empíricos e (2) artigos que utilizaram instrumentos para avaliar a agressividade de torcedores. Os critérios de exclusão foram: (1) artigos publicados em outros idiomas além do português, inglês, espanhol e francês; (2) estudo com instrumento não psicométrico; e (3) estudos que apresentaram instrumentos sem possibilidade de acesso do texto completo. Os artigos selecionados foram lidos na íntegra e agrupados de acordo com as categorias de interesse (p. ex.: teoria que embasa o instrumento, dimensionalidade, tipo de escala de respostas, tipo de aplicação, dentre outras).

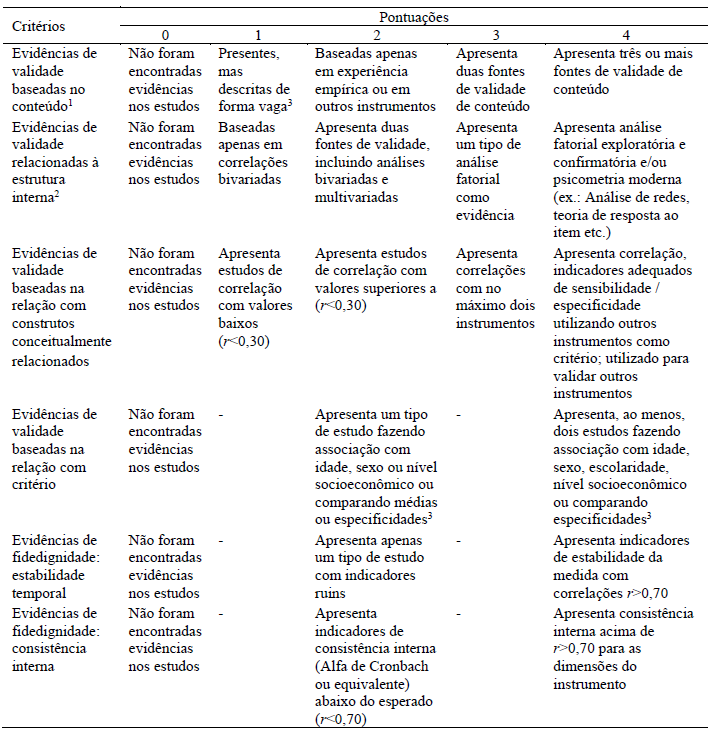

Definição dos critérios de avaliação da qualidade psicométrica

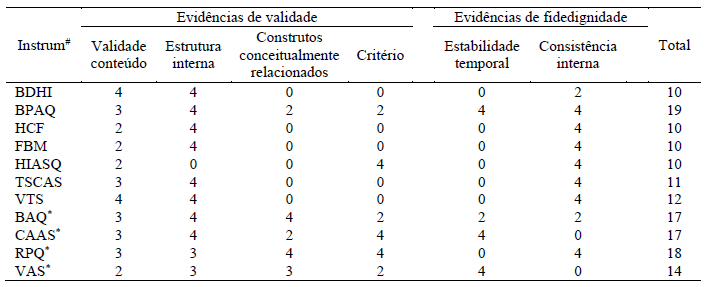

No intuito de identificar a qualidade psicométrica dos instrumentos encontrados, foram elaborados critérios de pontuação, seguindo recomendações dos American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association e National Council on Measurement in Education (AERA et al., 2014). Esses critérios classificaram os instrumentos conforme os tipos de validade e fidedignidade. Para isso, utilizou-se uma escala de pontuação (variando de zero a quatro pontos) em ordem progressiva de qualidade. Desse modo, a pontuação zero indicava inexistência de evidências psicométricas e quatro apontava instrumentos mais robustos quanto à sua validade ou fidedignidade, ou seja, que utilizaram métodos e análises estatísticas mais modernas, avançadas e rigorosas. Especificamente, na avaliação da validade baseada na relação com critério e na fidedignidade (estabilidade temporal e consistência interna), adotou-se apenas três possibilidades de pontuação (0, 2 e 4). As descrições empregadas na classificação dos instrumentos estão detalhadas na Tabela 1.

Tabela 1: Definição dos critérios para pontuação

das características psicométricas dos instrumentos analisados

na revisão

Fonte: Baseado no estudo de Silva et al. (2018).

Notas:

1Fontes de validade de conteúdo: base teórica consistente, uso de

itens validados em outros instrumentos, análise do instrumento por experts,

estudo piloto, análise semântica dos itens; 2Dimensionalidade e

relações entre escores ou subescores do mesmo inventário; 3Especificidades:

modalidade esportiva, pertencer a grupos de torcedores.

Resultados

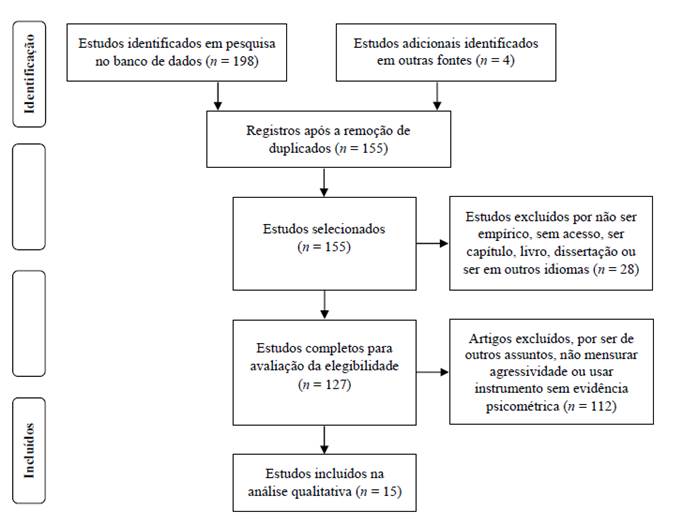

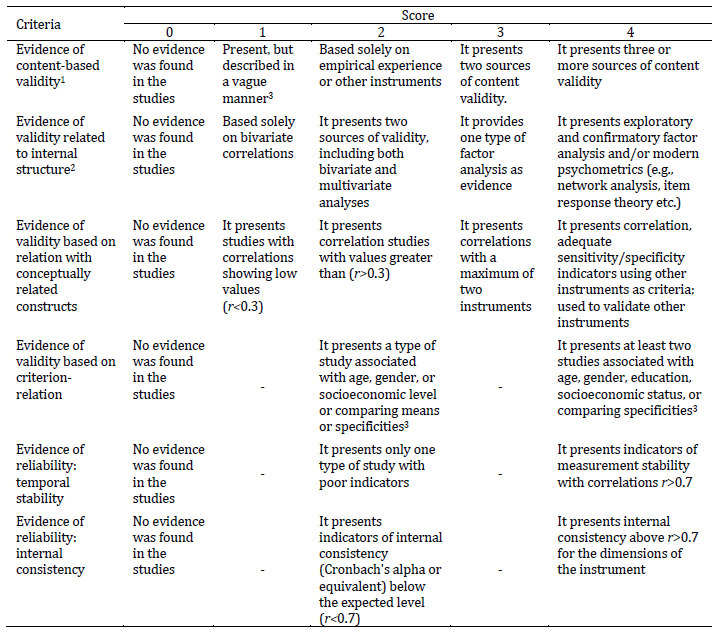

Acerca dos artigos encontrados, houve acordo total (100 %) entre os dois pesquisadores. Com os descritores e critérios operacionais delimitados foram identificados 198 estudos. Após a remoção dos duplicados, restaram 155, dos quais 140 foram excluídos por que: (a) não eram artigos empíricos (n = 3); (b) não havia acesso ao instrumento (n = 1); (c) eram livros ou capítulos (n = 17); (d) dissertação ou tese (n = 2); (e) publicados em idiomas diferentes de português, inglês, espanhol ou francês (n = 5); (f) abordaram outros assuntos (n = 74); (g) o instrumento utilizado foi criado apenas para o estudo e/ou não relatou o uso de pelo menos um instrumento psicométrico que avaliou a agressividade (n = 10); ou (h) não mensuraram a agressividade (n = 28). No total, 15 estudos preencheram os critérios de inclusão (Figura 1).

Figura 1: Fluxograma do processo de busca sistemática (PRISMA)

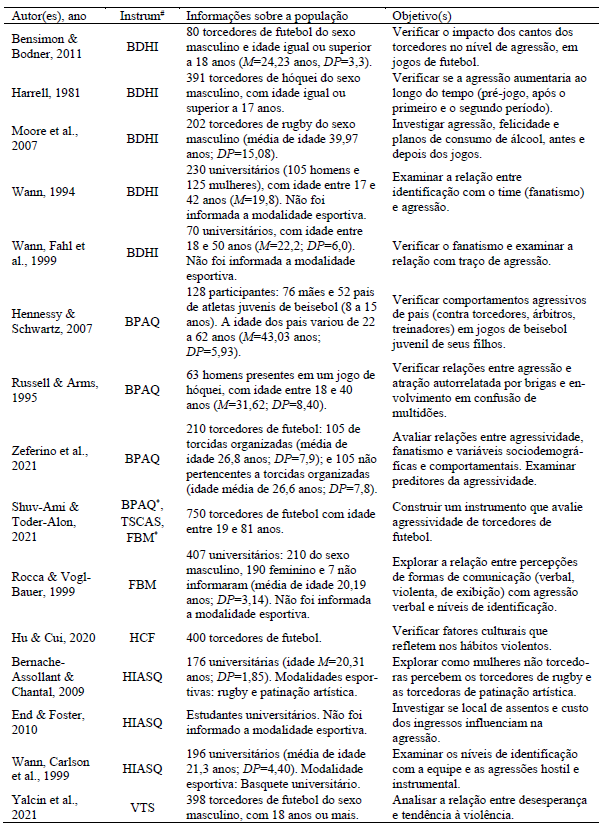

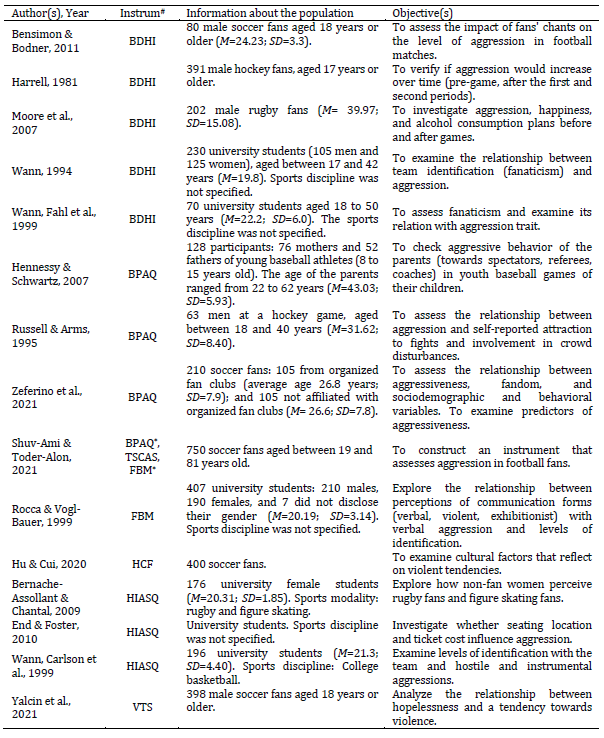

Os métodos dos 15 artigos foram lidos para identificar e contabilizar os instrumentos de medida utilizados para avaliar a agressividade e verificar as evidências psicométricas reportadas. Foram identificados sete instrumentos, a saber: (1) Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (BDHI, Buss & Durkee, 1957) (f = 5); (2) Buss and Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ, Buss & Perry, 1992) (f = 4); (3) Habitus of Chinese Football (HCF, Hu & Cui, 2020) (f = 1); (4) Fan Behavior Measure (FBM, Rocca & Vogl‐Bauer, 1999) (f = 2); (5) Hostile and Instrumental Aggression of Spectators Questionnaire (HIASQ, Wann, Fahl et al., 1999) (f = 3); (6) Team Sport Club Aggression Scale (TSCAS, Shuv-Ami & Toder-Alon, 2021) (f = 1); e (7) Violence Tendency Scale (VTS, Yalcin et al., 2021) (f = 1). Além disso, destaca-se que, no estudo de Shuv-Ami e Toder-Alon (2021) havia três instrumentos. A Tabela 2 apresenta a descrição dos estudos.

Tabela 2: Descrição dos estudos em que os instrumentos foram encontrados inicialmente

Nota: Instrum#: Instrumento; BDHI: Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory; BPAQ: Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire; HCF: Habitus of Chinese Football; FBM: Fan Behavior Mensure; HIASQ: Hostile and Instrumental Aggression Spectators Questionnaire; TSCAS: Team Sport Club Aggression Scale; VTS: Violence Tendency Scale; *Auxiliou na elaboração de itens (agressão física e verbal) para construção de novo instrumento.

Além disso, foram encontrados mais quatro instrumentos adicionais por outras fontes de informação (seção de referências dos estudos incluídos), a saber: (1) Brief Aggression Questionnaire (BAQ, Vitoratou et al., 2009); (2) Competitive Aggressiveness and Anger Scale (CAAS, Maxwell & Moores, 2007); (3) The Reactive-Proactive Questionnaire (RPQ, Raine et al., 2006); e (4) The Verbal Aggression Scale (VAS, Infante & Wigley, 1986). Diante disso, 11 instrumentos foram selecionados para análise qualitativa de suas características descritivas e psicométricas.

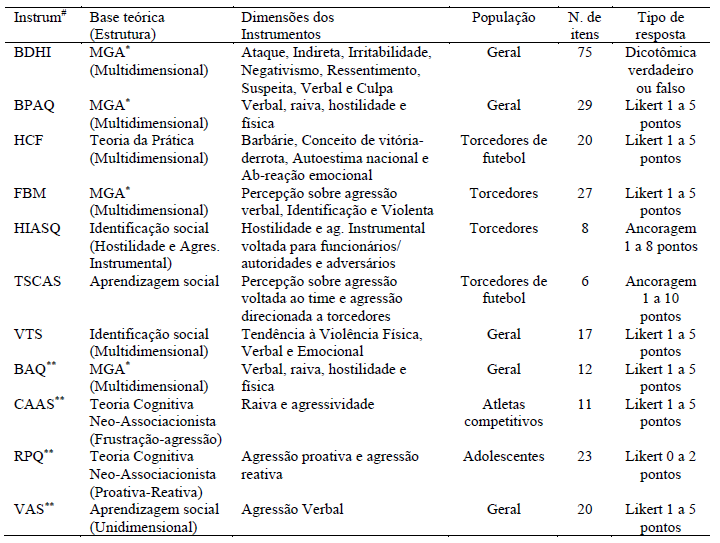

Características operacionais dos instrumentos

Acerca das bases teóricas, o Modelo Geral de Agressão (MGA) (Anderson & Bushman, 2002) foi o referencial mais utilizado. Outros modelos como a Aprendizagem Social, Teoria Cognitiva Neo-Associacionista, Identificação Social e Teoria da Prática também foram utilizados. A dimensionalidade também variou, porém o formato multidimensional foi o mais empregado, sendo utilizado em seis instrumentos. Dentre os instrumentos multidimensionais, três deles Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (Buss & Durkee, 1957), Buss and Perry Aggression Questionnaire (Buss & Perry, 1992) e Brief Aggression Questionnaire (Vitoratou et al., 2009) são versões “progressistas”, ou seja, versões revisadas e reduzidas da versão original.

As dimensões mais empregadas nos instrumentos foram: agressão verbal (f = 5, correspondente a 45% dos instrumentos) e agressão física, raiva e hostilidade (f = 2, equivalente a 18% dos instrumentos). Outras formas de manifestações da agressividade também foram mensuradas nos instrumentos, porém em menor frequência. Em alguns casos, a medida foi mais generalista (p. ex.: subescala avaliando a agressividade, sem nenhuma diferenciação e a agressão voltada ao time e aos torcedores, sendo nesses dois casos, sem relatar o tipo de comportamento). Houve, ainda, medidas/subescalas avaliando outras especificidades (p. ex.: irritabilidade, ressentimento, reação emocional, culpa, negativismo, tendências, a partir da identificação com o time, da reação em vitórias e derrotas, etc.).

Referente às populações dos estudos, sete estudos tinham como foco específico torcedores esportivos, sendo cinco de futebol (Bensimon & Bodner, 2011; Hu & Cui, 2020; Shuv-Ami & Toder-Alon, 2021; Yalcin et al., 2021; Zeferino et al., 2021), um de hóquei (Harrell, 1981) e um de rugby (Moore et al., 2007). Seis focaram em estudantes universitários (Bernache-Assollant & Chantal, 2009; End & Foster, 2010; Rocca & Vogl‐Bauer, 1999; Wann, 1994; Wann, Carlson et al., 1999; Wann, Fahl et al., 1999).

Houve, também, estudo com população de homens presentes em uma partida de hóquei (Russell & Arms, 1995), com estudantes torcedores de basquete universitário (Wann, Carlson et al., 1999) e pais de atletas juvenis de beisebol (Hennessy & Schwartz, 2007). Referente aos instrumentos adicionais (encontrados por outras fontes de informação), um investigou atletas competitivos (CAAS, Maxwell & Moores, 2007), dois a população geral (BAQ, Vitoratou et al., 2009; VAS, Infante & Wigley, 1986) e outro adolescentes (RPQ, Raine et al., 2006). Consequentemente, nesses casos em que não abordavam o contexto esportivo os itens dos instrumentos de medida podem ter sido respondidos com a presença de vieses de resposta. Ainda referente aos itens, a quantidade variou de seis a 75, tendo a maioria compreendidos entre 20 e 29.

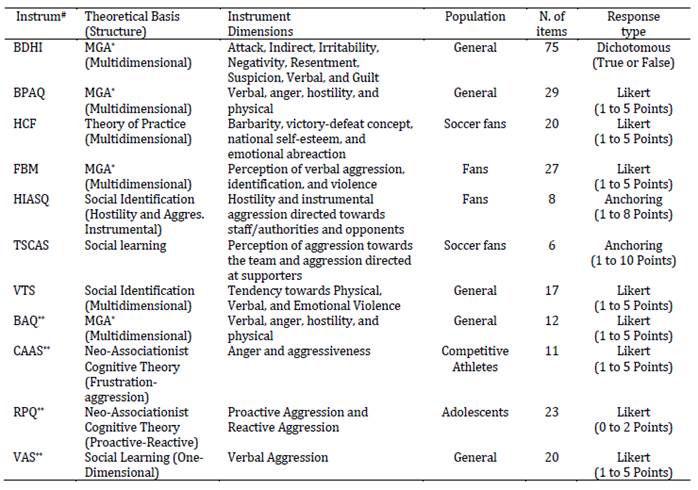

Concernente ao formato de aplicação, todos os instrumentos são autoaplicáveis. O tipo de resposta variou, sendo a maioria do tipo Likert (f=8). Desses oito, em apenas um as opções de respostas foram de zero a dois pontos e nos demais, foram de um a cinco pontos. Em dois instrumentos as opções de respostas foram dadas em ancoragem (em um deles, entre 1 e 8 pontos e, em outro, entre 1 e 10 pontos) e em um estudo as respostas eram dicotômicas (em que o respondente assinalava verdadeiro ou falso para os itens). A Tabela 3 apresenta a descrição operacional dos instrumentos de medida de agressividade analisados nesta revisão.

Tabela 3: Características descritivas e operacionais dos instrumentos analisados na revisão

Nota: Instrum#: Instrumento; BDHI: Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory; BPAQ: Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire; HCF: Habitus of Chinese Football; FBM: Fan Behavior Mensure; HIASQ: Hostile and Instrumental Aggression Spectators Questionnaire; TSCAS: Team Sport Club Aggression Scale; VTS: Violence Tendency Scale; BAQ: Brief Aggression Questionnaire; CAAS: Competitive Aggressiveness and Anger Scale; RPQ: Reactive-Proactive Questionnaire; VAS: Verbal Aggression Scale; *MGA: Modelo Geral da Agressão; ** Instrumentos extras, incluídos por outros fontes (a partir da sessão de referências dos estudos incluídos inicialmente).

Qualidades psicométricas

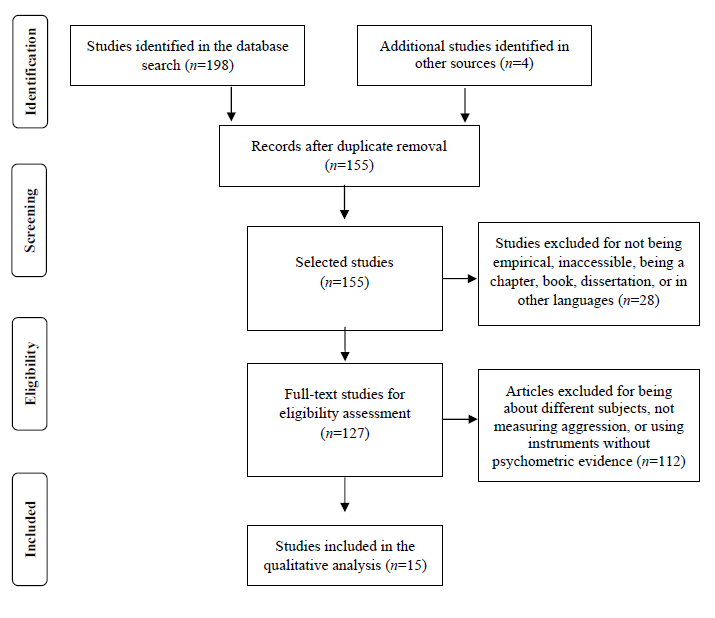

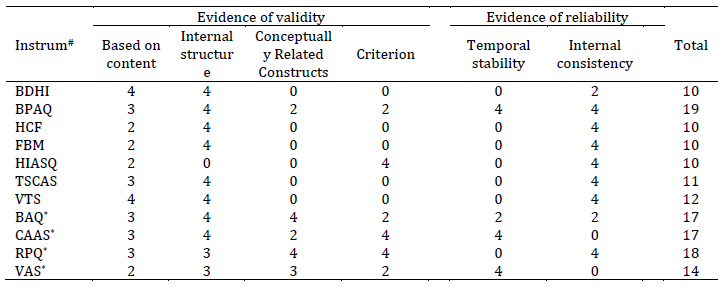

As qualidades psicométricas receberam pontuações para verificar a acurácia e robustez dos instrumentos incluídos nesta revisão. A análise demonstrou que nenhum dos onze instrumentos atingiu a pontuação máxima (24 pontos). As pontuações mais altas foram 19 pontos no Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (Buss & Perry, 1992), 18 pontos no The Reactive-Proactive Questionnaire (Raine et al., 2006) e 17 pontos no Brief Aggression Questionnaire (Vitoratou et al., 2009) e na Competitive Aggressiveness and Anger Scale (Maxwell & Moores, 2007). A Verbal Aggression Scale (Infante & Wigley, 1986) obteve 14 pontos e os demais instrumentos apresentaram evidências psicométricas insatisfatórias (pontuação de 12 pontos ou menos), principalmente, nas validades de construto e critério e fidedignidade em relação à estabilidade temporal.

No que se refere às evidências de validade baseadas no conteúdo, cinco instrumentos Brief Aggression Questionnaire (Vitoratou et al., 2009), Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (Buss & Perry, 1992), Competitive Aggressiveness and Anger Scale (Maxwell & Moores, 2007), Team Sport Club Aggression Scale (Shuv-Ami & Toder-Alon, 2021) e The Reactive-Proactive Questionnaire (Raine et al., 2006) obtiveram três pontos, por apresentarem as bases teóricas empregadas e utilizarem itens já testados em instrumentos anteriores. Além dessas duas evidências, o Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (Buss & Durkee, 1957) e a Violence Tendency Scale (Yalcin et al., 2021) apresentaram outros tipos de evidências (análise semântica dos itens e análise do instrumento por experts) e alcançaram a pontuação total (4 pontos). Os outros instrumentos obtiveram 2 pontos.

Nas evidências de estrutura interna, apenas um instrumento (HIASQ, Wann, Carlson et al., 1999) não pontuou, dois (RPQ, Raine et al., 2006; VAS, Infante & Wigley, 1986) obtiveram três pontos. Os outros oito, alcançaram a pontuação total. Três instrumentos (BDHI, Buss & Durkee, 1957; HCF, Hu & Cui, 2020; FBM, Rocca & Vogl‐Bauer, 1999) pontuaram por realizarem análise fatorial exploratória e outros três (BAQ, Vitoratou et al., 2009; RPQ, Raine et al., 2006; VAS, Infante & Wigley, 1986) por terem realizado análise fatorial confirmatória. Houve, ainda, quatro casos (BPAQ, Buss & Perry, 1992; CAAS, Maxwell & Moores, 2007; TSCAS, Shuv-Ami & Toder-Alon, 2021; VTS, Yalcin et al., 2021) em que se empregou tanto análise fatorial exploratória, quanto confirmatória. Além disso, no Brief Aggression Questionnaire (Vitoratou et al., 2009) foi empregado a Teoria de Resposta ao Item (TRI) e na Team Sport Club Aggression Scale (Shuv-Ami & Toder-Alon, 2021) rede nomológica. Ademais, a modelagem de equações estruturais, foi utilizada em duas escalas (CAAS, Maxwell & Moores, 2007; TSCAS, Shuv-Ami & Toder-Alon, 2021).

Referente às evidências de validade com base na relação de construtos conceitualmente relacionados, apenas dois instrumentos (BAQ, Vitoratou et al., 2009; RPQ, Raine et al., 2006) receberam pontuação máxima (quatro pontos) por apresentarem correlações significativas com outros instrumentos e devido à utilização para validação de outros instrumentos. Outros três instrumentos também pontuaram nessa evidência de validade, sendo a The Verbal Aggression Scale (Infante & Wigley, 1986) por apresentar correlação com dois instrumentos de medida (três pontos) e o Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (Buss & Perry, 1992) e a Competitive Aggressiveness and Anger Scale (Maxwell & Moores, 2007) por apresentar correlação com um instrumento (dois pontos). Ademais, seis instrumentos não receberam pontuação, por não apresentarem nenhum tipo de evidência nessa validade.

Nas evidências de validade baseadas na relação com critério, somente a Competitive Aggressiveness and Anger Scale (Maxwell & Moores, 2007) e o The Reactive-Proactive Questionnaire (Raine et al., 2006) alcançaram a pontuação total. Nesses dois instrumentos foram realizadas análises comparativas de especificidades esportivas e associações com idade, sexo, escolaridade e/ou nível socioeconômico). Os questionários Brief Aggression (Vitoratou et al., 2009) e Buss-Perry Aggression (Buss & Perry, 1992) e a escala The Verbal Aggression (Infante & Wigley, 1986) receberam dois pontos, devido as comparações de médias e entre os sexos dos respondentes. Os outros seis instrumentos não pontuaram nessa evidência de validade.

As evidências de fidedignidade, foram verificadas por dois métodos: estabilidade temporal e consistência interna. Referente ao primeiro, três instrumentos (BPAQ, Buss & Perry, 1992; CAAS, Maxwell & Moores, 2007; VAS, Infante & Wigley, 1986) atingiram a pontuação máxima, por apresentarem indicadores satisfatórios conforme esperado (correlação acima de 0,7). O Brief Aggression Questionnaire (Vitoratou et al., 2009) também pontuou nessa evidência de fidedignidade, porém os valores foram abaixo de 0,7, obtendo apenas dois pontos. Os demais instrumentos não pontuaram. Já no segundo método (consistência interna), dois instrumentos (CAAS, Maxwell & Moores, 2007; VAS, Infante & Wigley, 1986) não pontuaram e dois estudos (BDHI, Buss & Durkee, 1957; BAQ, Vitoratou et al., 2009) apresentaram valores abaixo de 0,7, obtendo dois pontos. Os outros sete instrumentos tiveram a pontuação total (quatro pontos), por apresentarem consistência interna acima de 0,7 para as dimensões do instrumento. A Tabela 4 apresenta as pontuações (parcial e total) de cada instrumento analisado.

Tabela 4: Pontuação das evidências psicométricas dos instrumentos presentes na revisão

Nota: Instrum #; BDHI: Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory; BPAQ: Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire; HCF: Habitus of Chinese Football; FBM: Fan Behavior Mensure; HIASQ: Hostile and Instrumental Aggression Spectators Questionnaire; TSCAS: Team Sport Club Aggression Scale; VTS: Violence Tendency Scale; BAQ: Brief Aggression Questionnaire; CAAS: Competitive Aggressiveness and Anger Scale; RPQ: Reactive-Proactive Questionnaire; VAS: Verbal Aggression Scale; *Instrumentos incluídos após critérios de inclusão.

Em resumo, constatou-se que, a maior parte dos instrumentos apresentou evidências de validade de conteúdo por meio de base teórica consistente e experiência empírica, utilizando itens já testados em outros instrumentos. Além disso, alguns estudos utilizaram técnicas como análise semântica dos itens e análise de juízes especialistas. Na análise da estrutura interna dos instrumentos, verificou-se que, a análise fatorial (exploratória e/ou confirmatória) foi a técnica mais utilizada, aparecendo em dez dos onze instrumentos e, em alguns casos, com estudos de psicometria moderna (teoria de resposta ao item e rede nomológica). Referente às evidências de validade de construto conceitualmente relacionados e critério, foi observado baixo engajamento dos autores para essas análises, tendo sido realizadas em apenas cinco instrumentos. No que tange às evidências de fidedignidade, apenas quatro instrumentos verificaram a estabilidade temporal (teste-reteste), porém na consistência interna, apenas um estudo não verificou essa evidência.

Discussão

Este estudo teve como objetivo realizar uma revisão sistemática da literatura em relação aos instrumentos empregados na avaliação da agressividade de torcedores esportivos. No que se refere às buscas, não foi estabelecido período, pois visou-se, também, o acúmulo de informações sobre os instrumentos. Sendo assim, foi possível conhecer as bases teóricas, características operacionais e psicométricas dessas medidas para discutir, teórica e psicometricamente, os instrumentos, com o intuito de embasar a criação de um instrumento específico.

Foram encontrados onze instrumentos que avaliaram a agressividade de torcedores. Entretanto, apenas quatro (HCF, Hu & Cui, 2020; FBM, Rocca & Vogl‐Bauer, 1999; HIASQ, Wann, Carlson et al., 1999; TSCAS, Shuv-Ami & Toder-Alon, 2021) são específicos para a população de torcedores. Além disso, em uma escala (CAAS, Maxwell & Moores, 2007) a população foi composta por atletas. O baixo número de instrumentos específicos encontrados para avaliar a agressividade de torcedores corroborou com o que tinha sido exposto por Zeferino et al. (2021).

Nos instrumentos específicos, verificou-se diferenças no foco de investigação: em um caso (HCF, Hu & Cui, 2020), foi mensurada a agressividade na forma mais cruel/brutal e as manifestações após vitória ou derrota de seu time, desconsiderando outras formas; em outro (TSCAS, Shuv-Ami & Toder-Alon, 2021), o respondente não relatava sobre si, os itens eram direcionados para o comportamento de outros torcedores. Além disso, dois estudos (FBM, Rocca & Vogl‐Bauer, 1999; HIASQ, Wann, Carlson et al., 1999) avaliaram a agressividade direcionada a funcionários/autoridades e adversários. Tal fato corrobora com autores da área ao destacarem que alguns estudos ignoram fatores e contextos importantes para o entendimento dessas manifestações dos torcedores (Brandão et al., 2020; Murad, 2017; Zeferino et al., 2021) e há uma forte tendência da Psicologia a se restringir ao contexto clínico (Tertuliano & Machado, 2019). Além disso, destaca-se a limitação em captar com maior precisão os detalhes, comportamentos e realidade dos torcedores (Zeferino et al., 2021).

Acerca das bases teóricas, o MGA de Anderson e Bushman (2002) foi o mais usado. O MGA parte de uma perspectiva interativa entre elementos biológicos, psicológicos, sociais e culturais considerando que o entendimento da agressividade deve ser multidimensional. Ademais, é preciso destacar que, esse modelo não desconsidera os outros, a proposta dos autores foi ampliar, teoricamente, a compreensão da agressividade, contemplando alguns aspectos de outras teorias, (p. ex.: Aprendizagem Social, Cognitiva Neo-Associacionista, dentre outras). Sendo assim, autores da área (Allen & Anderson, 2017; Bushman & Anderson 2020) destacaram que o modelo é o mais completo e aceito devido à essa ampliação teórica e por reduzir concepções fragmentadas e/ou reducionistas. Diante disso, acredita-se que o MGA seria o mais indicado para a criação de um novo instrumento com essa finalidade.

No que se refere à estrutura dos instrumentos, dois estudos verificaram a percepção do respondente em relação ao comportamento de outros torcedores (TSCAS, Shuv-Ami & Toder-Alon, 2021; FBM, Rocca & Vogl‐Bauer, 1999), outro adotou uma estrutura unidimensional (VAS, Infante & Wigley, 1986) e quatro bidimensional (RPQ, Raine et al., 2006; CAAS, Maxwell & Moores, 2007; TSCAS, Shuv-Ami & Toder-Alon, 2021; HIASQ, Wann, Carlson et al., 1999). Esses instrumentos foram considerados limitados, pois a agressividade de torcedores é um fenômeno multidimensional (Brandão et al., 2020; Moore et al., 2007) e composta por componentes que se relacionam (Buss & Perry, 1992). Para esses autores, a agressividade envolve um estímulo, que é recebido pelo componente cognitivo (hostilidade), desencadeando uma reação emocional (raiva) e essa reação é capaz de produzir um componente instrumental ou motor do comportamento (agressão física ou verbal).

Acerca da dimensionalidade dos instrumentos, foi identificada uma variedade na quantidade e conteúdo das dimensões. Esse fato pode estar expondo a natureza extensiva acerca do conceito de agressividade e, ao mesmo tempo, justificando a separação em conjuntos de itens (dimensões) para diluir a complexidade do objeto de estudo e obter um melhor entendimento (Tay & Jebb, 2017), ou seja, contribuir para a avaliação e entendimento da agressividade e suas manifestações. Na análise feita foi constatado que, hostilidade, raiva e, principalmente, agressões verbais e físicas são as dimensões mais avaliadas nos instrumentos. Porém, em alguns casos, não é especificado o tipo de agressividade (seja por meio de uma tendência ou ato concreto), em outros, verificou-se a identificação social ou com o time (fanatismo) e, ainda, houve casos em que as dimensões avaliaram formas de agressividade, como: indireta, direcionada (para funcionários, autoridades e adversários), proativa-reativa e frustração-agressão.

Em relação às propriedades psicométricas, seis dos onze instrumentos analisados não apresentaram índices satisfatórios, considerando as recomendações de AERA et al. (2014). Desses seis, estão os únicos quatro específicos à população de torcedores (HCF, Hu & Cui, 2020; FBM, Rocca & Vogl‐Bauer, 1999; HIASQ, Wann, Carlson et al., 1999; TSCAS, Shuv-Ami & Toder-Alon, 2021). Em todos esses casos, as pontuações foram zero nas evidências de validades de construtos conceitualmente relacionados e a evidência de fidedignidade por estabilidade temporal.

Dos instrumentos específicos ao contexto de torcedores, todos apresentaram pontuações baixas (12 pontos (que corresponde à metade da pontuação) ou menos) acerca de suas evidências psicométrica. Ademais, o Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (Buss & Durkee, 1957), um dos instrumentos com pontuação mais baixa (10 pontos), foi o mais utilizado. A The Verbal Aggression Scale (Infante & Wigley, 1986) apresentou pontuação considerada média (14 pontos). Por meio dos resultados constatou-se, também, que quatro instrumentos de medida avaliados (BPAQ, Buss & Perry, 1992; BAQ, Vitoratou et al., 2009; CAAS, Maxwell & Moores, 2007; RPQ, Raine et al., 2006) são considerados satisfatórios, ou seja, apresentaram maior concordância com a literatura da área (DeVellis, 2003; Pasquali, 2010; Tay & Jebb, 2017), sendo elaborados e analisados psicometricamente com mais rigor teórico e metodológico.

Acerca da frequência de uso dos instrumentos, o Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (f = 5) e o Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (f = 4) foram os mais utilizados. Porém, como salientado por Maxwell e Moores (2007), o uso desses dois instrumentos no esporte é problemático, por não possuírem itens específicos e aplicáveis para o contexto em questão. Tal fato também reforça a necessidade de criação de um instrumento específico, pois na ausência dessa medida, os autores acabam recorrendo a instrumentos que apontaram limitações para o uso no esporte.

No que se refere às evidências de validade de conteúdo, seis dos onze instrumentos foram elaborados a partir da literatura da área, seguindo teorias de agressividade e outros instrumentos. Apenas o Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (BDHI; Buss & Durkee, 1957) e a Violence Tendency Scale (VTS; Yalcin et al., 2021) obtiveram pontuação máxima, por terem outros tipos de evidências, como análise semântica dos itens, para conferir se os itens estavam claros para membros da população-alvo de menor nível de escolaridade, conforme recomenda Pasquali (2010). Ademais, a VTS teve análise de juízes especialistas. Essa técnica é indicada por contemplar as considerações de estudiosos da área para verificar a pertinência do item à teoria, se os itens estão sendo capazes de representar o construto avaliado e o quão claro está a redação (AERA et al., 2014; DeVellis, 2003).

A partir da escolha dos itens, é necessário determinar a dimensionalidade, comumente verificada pela estrutura interna (Muñiz & Fonseca-Pedrero, 2019). Dez dos 11 instrumentos realizaram algum tipo de análise fatorial. Em três, utilizou-se exploratória, por não ter uma base teórica consistente ou evidências empíricas apontando a maneira dos itens serem retidos e avaliados (Damásio, 2012). Em outros três, confirmatória, em que os itens foram testados em um modelo teórico já definido. Ademais, os outros quatro utilizaram os dois métodos. Segundo DeVellis (2003), a combinação entre esses dois tipos de análise fatorial gera resultados psicométricos mais robustos. Os resultados encontrados discordaram de Morgado et al. (2017) ao afirmarem predomínio de análise fatorial exploratória no desenvolvimento de instrumentos.

Acerca das evidências de validade baseadas na relação com construtos conceitualmente relacionados, apenas dois questionários Brief Aggression (Vitoratou et al., 2009) e The Reactive-Proactive (Raine et al., 2006) atingiram a pontuação total. Eles foram ao encontro de Muñiz e Fonseca-Pedrero (2019), evidenciando que a escolha apropriada de variáveis externas pode agregar diferentes tipos de evidências e gerar interpretações mais adequadas dos escores na utilização do instrumento. Por outro lado, seis instrumentos (BDHI, Buss & Durkee, 1957; HCF, Hu & Cui, 2020; FBM, Rocca & Vogl‐Bauer, 1999; HIASQ, Wann, Carlson et al., 1999; TSCAS, Shuv-Ami & Toder-Alon, 2021; VTS, Yalcin et al., 2021) não pontuaram por não apresentarem esse tipo de evidência. Tal fato sinaliza limitações, pois como salientaram Tay e Jebb (2017), uma medida relacionada empiricamente com outras confirma os pressupostos teóricos e oferece importantes evidências de validade.

Na validade baseada na relação com critério, somente os questionários Hostile and Instrumental Aggression (Wann, Carlson et al., 1999) e Reactive-Proactive (Raine et al., 2006) e a escala Competitive Aggressiveness and Anger (Maxwell & Moores, 2007) atingiram a pontuação total. Eles continham análises comparativas com tipo de esporte e gravidade da delinquência e variáveis como sexo, idade, status socioeconômico e etnia. A escolha dos grupos/variáveis a serem usadas para avaliar a validade de critério é de suma importância e propicia mais confiança na interpretação do instrumento (Muñiz & Fonseca-Pedrero, 2019).

No que se refere às evidências de fidedignidade, apenas quatro instrumentos pontuaram em estabilidade temporal. Os outros sete não analisaram esse tipo de evidência, contrariando autores da área (DeVellis, 2003; Morgado, et al., 2017), ao afirmarem que essa é uma das evidências mais investigadas em desenvolvimento de instrumentos. Desses sete instrumentos, com exceção do The Reactive-Proactive Questionnaire (Raine et al., 2006), todos obtiveram pontuação total baixa (menos da metade, ou seja, 12 pontos). Já em consistência interna, a maioria dos instrumentos (nove) realizaram a análise pelo coeficiente alfa de Cronbach. Segundo Hair et al. (2009), esse é o procedimento estatístico mais empregado nesse tipo de evidência.

Esta revisão buscou, principalmente, verificar instrumentos que mensurem a agressividade e analisar suas bases teóricas e características operacionais e evidências psicométricas. Entretanto, apresenta algumas limitações. A primeira, diz respeito a não inclusão de instrumentos que podem ter sido publicados apenas via literatura cinzenta (teses, dissertações, congressos, etc.). A segunda se refere aos descritores, acredita-se que a temática não se esgota apenas com esses termos. Visando contornar essa limitação os descritores foram escolhidos a partir de buscas em índices de palavras-chave e em artigos relacionados a temática, conforme sugere Clark e Watson (1995). A terceira limitação, por não ter sido feita uma avaliação do fator de impacto dos periódicos em que os estudos foram publicados e por não ter avaliado a qualidade metodológica dos artigos. Em quarto lugar, pela escolha de idiomas (português, inglês, espanhol e francês) que pode não ter incluído instrumentos relevantes para as análises e discussões.

A partir dos achados desta revisão, destaca-se a carência de instrumentos específicos que avaliam a agressividade de torcedores, conforme relatado por Zeferino et al. (2021). Esse fato torna visível a urgência de maior investimento em pesquisas que visam a construção e validação de instrumentos com essa finalidade. Mesmo diante de limitações, acredita-se que, esta revisão apresenta contribuições relevantes para uma melhor compreensão dos instrumentos psicométricos que avaliaram a agressividade de torcedores esportivos e, principalmente, apresenta as bases teóricas e psicométricas para a criação de um instrumento específico que contorne essa carência. Entretanto, entende-se que a avaliação da agressividade não se restringe a esses aspectos, pois outras variáveis podem influenciar na manifestação deste construto.

Considerações Finais

A avaliação da agressividade de torcedores é de suma importância para administradores dos esportes, pesquisadores, governantes/políticos, pessoas envolvidas diretamente com o esporte (funcionários, técnicos, atletas, torcedores, dentre outros) e sociedade, de maneira geral. É evidente a necessidade de criação e validação de instrumentos com embasamento teórico e metodológico para avaliar a agressividade dessa população em diversas modalidades e grupos.

Acredita-se que, um instrumento com essa finalidade poderia auxiliar no mapeamento da agressividade, facilitar a identificação de perfis agressivos e, principalmente, conhecer os níveis de agressividade desses torcedores. Sendo assim, será possível criar e articular medidas no ambiente das torcidas, locais de competições, saúde e segurança pública e rendimento e saúde mental dos atletas, para favorecer o esporte, investidores e sociedade (Murad, 2017; Zeferino et al., 2021).

Diante dessa revisão, acredita-se que o desenvolvimento de um instrumento multidimensional seria o mais indicado para suprir essa carência de instrumentos, pelo fato de a agressividade ter várias facetas. Ademais, é notável a necessidade de instrumentos específicos para avaliar a agressividade de torcedores e com evidências psicométricas adequadas, para suprir as falhas metodológicas identificadas nos instrumentos analisados nesta revisão. Além disso, estimula-se novos estudos para compreender outras variáveis (p. ex.: fanatismo, anonimato em meio à multidão, traços de personalidade, desejabilidade social, escolaridade, sexo, idade, estado civil, dentre outras) capazes de afetar a manifestação agressiva dessa população (Bandeira & Ramos, 2020; Fanti et al., 2019; Hennessy & Schwartz, 2007; Zeferino et al., 2021).

Referencias:

Albino, I., & Conde, E. (2019). Revisão sistemática: instrumentos para avaliação do estresse e ansiedade em jogadores de futebol. Revista Brasileira de Psicologia do Esporte, 9(1), 12-31. http://doi.org/10.31501/rbpe.v9i1.9706

Allen, J. J., & Anderson, C. A. (2017). General Aggression Model. The International Encyclopedia of Media Effects, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781118783764.wbieme0078

American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association & National Council for Measurement in Education. (2014). The Standards for Educational and Psychological Testing.

Anderson, C. A., & Bushman, B. J. (2002). Human Aggression. Annual Review of Psychology, 53(1), 27-51. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev.psych.53.100901.135231

Anderson, C. A., & Huesmann, L. R. (2003). Human aggression: A social-cognitive view. Em M. A. Hogg & J. Cooper (Eds.), The Sage Handbook of Social Psychology (pp. 296-323). Sage.

Bandeira, V. de F., & Ramos, D. G. (2020). Aspectos sociodemográficos relacionados à agressividade e ao fanatismo em uma torcida de futebol. Psicologia Revista, 29(1), 246-272. https://doi.org/10.23925/2594-3871.2020v29i1p246-272

Bensimon, M., & Bodner, E. (2011). Playing With Fire: The Impact of Football Game Chanting on Level of Aggression. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41(10), 2421-2433. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1559-1816.2011.00819.x

Bernache‐Assollant, I., & Chantal, Y. (2009). Perceptions of sport fans: An exploratory investigation based on aggressive and cheating propensities. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 7(1), 32-45. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2009.9671891

Brandão, T., Murad, M., Belmont, R., & Santos, R. F. D. (2020). Álcool e violência: Torcidas organizadas de futebol no Brasil. Movimento, 26. https://doi.org/10.22456/1982-8918.90431

Budevici-Puiu, L., Manolachi, V., & Manolachi, V. (2020). Specific Elements of Good Governance in Sport, as Important Factors in Ensuring the Management. Revista Romaneasca pentru Educatie Multidimensionala, 12(4), 328-337. https://doi.org/10.18662/rrem/12.4/348

Bushman, B. J., & Anderson, C. A. (2020). General Aggression Model. The International Encyclopedia of Media Psychology, 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1002/9781119011071.iemp0154

Buss, A. H., & Durkee, A. (1957). An inventory for assessing different kinds of hostility. Journal of Consulting Psychology, 21(4), 343-349. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0046900

Buss, A. H., & Perry, M. (1992). The Aggression Questionnaire. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 63(3), 452-459. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.63.3.452

Carriedo, A., Cecchini, J. A., & González, C. (2020). Soccer spectators’ moral functioning and aggressive tendencies in life and when watching soccer matches. Ethics & Behavior, 31(2), 136-150. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508422.2020.1715801

Clark, L. A., & Watson, D. (1995). Constructing Validity: Basic Issues in Objective Scale Development. Psychological Assessment, 7(3), 309-319. https://doi.org/10.1037/1040-3590.7.3.309

Damásio, B. F. (2012). Uso da análise fatorial exploratória em psicologia. Avaliação Psicológica: Interamerican Journal of Psychological Assessment, 11(2), 213-228. https://www.redalyc.org/pdf/3350/335027501007.pdf

DeVellis, R. F. (2003). Scale development: Theory and applications (2a ed.). Sage.

End, C. M., & Foster, N. J. (2010). The Effects of Seat Location, Ticket Cost, and Team Identification on Sport Fans' Instrumental and Hostile Aggression. North American Journal of Psychology, 12(3).

Fanti, K. A., Phylactou, E., & Georgiou, G. (2019). Who is the hooligan? The role of psychopathic traits. Deviant Behavior, 42(4), 492-502. https://doi.org/10.1080/01639625.2019.1695466

Hair, J. F., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., Anderson, R. E., & Tatham, R, L. (2009). Análise multivariada de dados (6a ed.). Bookman.

Harrell, W. A. (1981). Verbal aggressiveness in spectators at professional hockey games: The effects of tolerance of violence and amount of exposure to hockey. Human Relations, 34(8), 643-655. https://doi.org/10.1177/001872678103400

Hennessy, D. A., & Schwartz, S. (2007). Personal Predictors of Spectator Aggression at Little League Baseball Games. Violence and Victims, 22(2), 205-215. https://doi.org/10.1891/088667007780477384

Hu, J., & Cui, G. (2020). Elements of the Habitus of Chinese Football Hooli-fans and Countermeasures to Address Inappropriate Behaviour. The International Journal of the History of Sport, 37(sup1), 41-59. https://doi.org/10.1080/09523367.2020.1742701

Infante, D. A., & Wigley III, C. J. (1986). Verbal aggressiveness: An interpersonal model and measure. Communications Monographs, 53(1), 61-69. https://doi.org/10.1080/03637758609376126

Lake, Y. A. (2020). Political causes of sport related violence and aggression: A systematic review. Iconic Research and Engineering Journals, 3(7), 50-53.

Maciel, P. R., Souza, M. R. D., & Rosso, C. F. W. (2016). Estudo descritivo do perfil das vítimas com ferimentos por projéteis de arma de fogo e dos custos assistenciais em um hospital da Rede Viva Sentinela. Epidemiologia e Serviços de Saúde, 25, 607-616. https://doi.org/10.5123/S1679-49742016000300016

Maxwell, J. P., & Moores, E. (2007). The development of a short scale measuring aggressiveness and anger in competitive athletes. Psychology of Sport and Exercise, 8(2), 179-193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychsport.2006.03.002

Moher, D., Shamseer, L., Clarke, M., Ghersi, D., Liberati, A., Petticrew, M., Shekelle, P., & Stewart, L. A., (2015). Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis Protocols (PRISMA-P) 2015 Statement. Systematic Reviews, 4(1), 1-9. https://doi.org/10.1186/2046-4053-4-1

Moore, S. C., Shepherd, J. P., Eden, S., & Sivarajasingam, V. (2007). The effect of rugby match outcome on spectator aggression and intention to drink alcohol. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 17(2), 118-127. https://doi.org/10.1002/cbm.647

Morgado, F., Meireles, J., Neves, C., Amaral, A., & Ferreira, M. (2017). Scale development: Ten main limitations and recommendations to improve future research practices. Psicologia: Reflexão e Crítica, 30(1), 1-20. https://doi.org/10.1186/s41155-016-0057-1

Muñiz, J., & Fonseca-Pedrero, E. (2019). Diez pasos para la construcción de un test. Psicothema, 31(1), 7-16. https://doi.org/10.7334/psicothema2018.291

Murad, M. (2017). A violência no futebol: novas pesquisas, novas ideias novas propostas (2a ed.). Benvirá.

Pasquali, L. (2010). Testes referentes a Construto: teoria e modelo de construção. Em L. Pasquali (Ed.), Instrumentação Psicológica: fundamentos e práticas (pp. 37-71). Artmed.

Raine, A., Dodge, K., Loeber, R., Gatzke‐Kopp, L., Lynam, D., Reynolds, C., Stouthamer-Loeber, M., & Liu, J. (2006). The reactive-proactive aggression questionnaire: Differential correlates of reactive and proactive aggression in adolescent boys. Aggressive Behavior: Official Journal of the International Society for Research on Aggression, 32(2), 159-171. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.20115

Ranjan, M., & Muraleedharan, S. (2021). Sports Fandom in Fredrerick Exley’sa Fans Notes. Annals of the Romanian Society for Cell Biology, 25(6), 9074-9078. https://www.annalsofrscb.ro/index.php/journal/article/view/7152/5348

Rocca, K. A., & Vogl‐Bauer, S. (1999). Trait Verbal Aggression, Sports Fan Identification, and Perceptions of Appropriate Sports Fan Communication. Communication Research Reports, 16(3), 239-248. https://doi.org/10.1080/08824099909388723

Rubio, K., & Camilo, J. D. O. (2019). Por quê uma Psicologia Social do Esporte. Em K. Rubio e J. A. de O. Camilo (Orgs.), Psicologia Social do Esporte (pp. 9-18). Képos.

Russell, G. W., & Arms, R. L. (1995). False consensus effect, physical aggression, anger, and a willingness to escalate a disturbance. Aggressive Behavior, 21(5), 381-386. https://doi.org/10.1002/1098-2337(1995)21:5<381::AID-AB2480210507>3.0.CO;2-L

Shuv-Ami, A., & Toder-Alon, A. (2021). A new team sport club aggression scale and its relationship with fans’ hatred, depression, self-reported aggression, and acceptance of aggression. International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology, 1-21. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2021.1979076

Silva, M. A., Mendonça Filho, E. J., Mônego, B. G., & Bandeira, D. R. (2018). Instruments for multidimensional assessment of child development: a systematic review. Early Child Development and Care, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2018.1528243

Tay, L., & Jebb, A. (2017). Scale Development. In S. Rogelberg (Ed.), The SAGE Encyclopedia of Industrial and Organizational Psychology (2a ed., pp. 1381-1384). Sage.

Tertuliano, I. W., & Machado, A. A. (2019). Psicologia do Esporte no Brasil: conceituação e o estado da arte. Pensar a Prática, 22. https://doi.org/10.5216/rpp.v22.53382

Toder-Alon, A., Icekson, T., & Shuv-Ami, A. (2018). Team identification and sports fandom as predictors of fan aggression: The moderating role of ageing. Sport Management Review, 22(2), 194-208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.smr.2018.02.002

Turğut, M., Yaşar, O. M., Sunay, H., Özgen, C., & Beşler, H. K. (2018). Evaluating Aggression Levels of Sport Spectators. European Journal of Physical Education and Sport Science, 4(3). https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1196665

Vitoratou, S., Ntzoufras, I., Smyrnis, N., & Stefanis, N. C. (2009). Factorial composition of the Aggression Questionnaire: a multi-sample study in Greek adults. Psychiatry Research, 168(1), 32-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psychres.2008.01.016

Wachelke, J. F., Andrade, A. L. D., Tavares, L., & Neves, J. R. (2008). Mensuração da identificação com times de futebol: evidências de validade fatorial e consistência interna de duas escalas. Arquivos Brasileiros de Psicologia, 60(1), 96-111. http://www.redalyc.org/pdf/2290/229017544009.pdf

Wann, D. L. (1994). The “noble” sports fan: The relationships between team identification, self-esteem, and aggression. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 78(3), 864-866. https://doi.org/10.1177/00315125940780

Wann, D. L., Carlson, J. D., & Schrader, M. P. (1999). The impact of team identification on the hostile and instrumental verbal aggression of sport spectators. Journal of Social Behavior and Personality, 14(2), 279-286. https://home.csulb.edu/~jmiles/psy100/wann.pdf

Wann, D. L., Fahl, C. L., Erdmann, J. B., & Littleton, J. D. (1999). Relationship between identification with the role of sport fan and trait aggression. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 88(3_suppl), 1296-1298. https://doi.org/10.2466/pms.1999.88.3c.1296

Yalcin, İ., Ekinci, N. E., & Ayhan, C. (2021). The effect of hopelessness on violence tendency: Turkish football fans. Physical Culture and Sport Studies and Research, 91(1), 13-20. https://doi.org/10.2478/pcssr-2021-0015

Zeferino, G. G., Silva, M. A., & Alvarenga, M. A. S. (2021). Associations between sociodemographic and behavioural variables, fanaticism and aggressiveness of soccer fans. Ciencias Psicológicas, 15(2), e-2390. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v15i2.2390

Disponibilidade de dados: O conjunto de dados que embasa os resultados deste estudo não está disponível.

Como citar: Zeferino, G. G., Da Silva, A. C. S., & Mansur-Alves, M. (2024). Instrumentos para avaliação da agressividade de torcedores esportivos: uma revisão sistemática. Ciencias Psicológicas, 18(1), e-3178. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v18i1.3178

Contribuição de autores (Taxonomia CRediT): 1. Conceitualização; 2. Curadoria de dados; 3. Análise formal;

4. Aquisição de financiamento; 5. Pesquisa; 6. Metodologia; 7. Administração do

projeto; 8. Recursos; 9. Software; 10. Supervisão; 11. Validação; 12.

Visualização; 13. Redação: esboço original; 14. Redação: revisão e edição.

G.G.Z. contribuiu em 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 11, 12, 13, 14; A. C. S. S.

em 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 8, 9, 12, 13;

M. M. A. em 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14.

Editora científica responsável: Dra. Cecilia Cracco.

10.22235/cp.v18i1.3178

Original Articles

Instruments for evaluation of aggressiveness in sports fans: a systematic review

Instrumentos para avaliação da agressividade de torcedores esportivos: uma revisão sistemática

Instrumentos

para evaluar la agresividad de los aficionados al deporte:

una revisión sistemática

Geovani Garcia Zeferino1, ORCID 0000-0002-8245-668X

Anna Clara Santos da Silva2, ORCID 0000-0002-0831-6793

Marcela Mansur-Alves3, ORCID 0000-0002-3961-3475

1 Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Brazil, [email protected]

2 Universidade Federal de São João del-Rei, Brazil

3 Universidade Federal de Minas Gerais, Brazil

Abstract:

The aim of the study was to identify instruments used to assess the aggressiveness of sports fans and describe their operational and psychometric characteristics. A systematic literature review was carried out, following PRISMA guidelines, in the BVS, PsycINFO, PubMed/MedLine, Science Direct, Scopus and Web of Science databases, using the Boolean descriptors and operators: scale OR test OR inventory OR questionnaire AND aggression OR violence OR aggressiveness AND spectators OR fans. 198 studies were found and, after exclusion criteria, 15 remained. In these studies, 11 instruments were identified. These instruments showed differences in theoretical bases, number and content of dimensions, administration method and type of response. In order to verify the robustness of the instruments, the psychometric evidences were scored. The findings of the present review showed the lack of specific instruments to assess the aggressiveness of fans, which can help researchers in the potential creation of measures for this purpose.

Keywords: aggressiveness; fans; measurement instruments; assessment; sports.

Resumo:

O objetivo do estudo foi identificar instrumentos utilizados para avaliar a agressividade de torcedores esportivos e descrever suas características operacionais e psicométricas. Foi realizada uma revisão sistemática na literatura, seguindo diretrizes do PRISMA, nas bases de dados BVS, PsycINFO, PubMed/MedLine, Science Direct, Scopus e Web of Science, utilizando os descritores e operadores booleanos: scale OR test OR inventory OR questionnaire AND aggression OR violence OR aggressiveness AND spectators OR fans. Foram encontrados 198 estudos e após critérios de exclusão, restaram 15. Nesses estudos, foram identificados 11 instrumentos. Esses instrumentos, apresentaram diferenças em bases teóricas, número e conteúdo das dimensões, modo de administração e tipo de resposta. No intuito de verificar a robustez dos instrumentos, as evidências psicométricas foram pontuadas. As descobertas da presente revisão evidenciaram carência de instrumentos específicos para avaliar agressividade de torcedores e poderão auxiliar pesquisadores em possíveis criações de medidas com essa finalidade.

Palavras-chave: agressividade; torcedores; instrumentos de medida; avaliação; esportivos.

Resumen:

El objetivo del estudio fue identificar instrumentos utilizados para evaluar la agresividad de los aficionados al deporte y describir sus características operativas y psicométricas. Se realizó una revisión sistemática de la literatura, siguiendo las pautas PRISMA, en las bases de datos BVS, PsycINFO, PubMed/MedLine, Science Direct, Scopus y Web of Science, utilizando los descriptores y operadores booleanos: escala OR test OR inventario OR cuestionario Y agresión OR violencia OR agresividad OR espectadores OR aficionados. Fueron encontrados 198 estudios y después de los criterios de exclusión quedaron 15. En ellos se identificados 11 instrumentos. Estos instrumentos mostraron diferencias en las bases teóricas, número y contenido de dimensiones, modo de administración y tipo de respuesta. Para verificar la robustez de los instrumentos, se puntuaron las evidencias psicométricas. Los hallazgos de la presente revisión mostraron la falta de instrumentos específicos para evaluar la agresividad de los fanáticos, que pueden ayudar a los investigadores en la posible creación de medidas para este propósito.

Palabras clave: agresividad; aficionados; instrumentos de medición; evaluación; deporte.

Received: 12/01/2023

Accepted: 21/12/2023

Sport is undoubtedly the cultural expression that has strengthened the most in recent decades (Rubio & Camilo, 2019), currently boasting billions of fans worldwide (Budevici-Puiu et al., 2020). Fans are those individuals motivated to regularly follow sports competitions, whether in person or through media (Ranjan & Muraleedharan, 2021). Sports events, on the other hand, are occasions that elicit various feelings and manifestations among their fans. While these competitions provide joy and positive emotions (Budevici-Puiu et al., 2020), they also replicate the aggression seen in the social everyday life of many individuals (Murad, 2017).

Specifically in sports, aggressions have occurred in professional, amateur, university, and youth competitions (Lake, 2020), spanning various disciplines (Turğut et al., 2018). Aggressiveness is a construct that presents several distinct definitions. Generally, it can be understood as an intentional action aimed at causing harm to another person or oneself (Allen & Anderson, 2017), which can be expressed physically, verbally, psychologically, among other forms (Anderson & Huesmann, 2003). In sports context, aggression by fans is a phenomenon that occurs worldwide (Brandão et al., 2020) and has become a concerning issue due to its various detrimental effects and negative consequences (Murad, 2017).

Among the most cited damages and consequences are the thousands of deaths and injuries resulting from fights involving fans (Lake, 2020; Murad, 2017). Concerning injuries, it is noted that there are impacts on the economy of the state, as hospitals provide necessary treatment and medicine to the injured, incurring additional expenses (Maciel et al., 2016). Moreover, in public security, according to Murad (2017), there are instances of aggressive behavior by police officers too, leading to clashes with fans. Consequently, the security staff get injured as well, are taken to public hospitals, and in some cases, are relieved of their duties.

Other impacts are observed in leisure activities of some fans, who refrain from or reduce their attendance at competition venues (stadiums, arenas, among others) due to these disturbances. Consequently, clubs experience reduction in ticket sales (Toder-Alon et al., 2018). Furthermore, athletes are also affected, as pressure, excessive demands, and aggression by fans have led to decreased performance and, in some cases, common mental disorders due to high levels of anxiety and stress (Albino & Conde, 2019).

In the light of the foregoing, it is emphasized that aggression by fans has led to negative consequences for clubs, other fans, and society at large (Lake, 2020; Murad, 2017). Therefore, tools to assess aggression by fans are of utmost importance to identify aggressive profiles and subsequently consider and promote alternatives to mitigate aggressive behavior. In this regard, Zeferino et al. (2021) highlighted the urgency of discussing strategies to reduce aggression. However, the authors mentioned the difficulty in measuring aggression by fans due to the lack of specific instruments.

Furthermore, concerning specific instruments for assessing aggression by fans, several studies (Carriedo et al., 2020; Turğut et al., 2018; Moore et al., 2007; Zeferino et al., 2021) used instruments without a focus on fans, such as the Buss and Perry Aggression Questionnaire (Buss & Perry, 1992) and the Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (Buss & Durkee, 1957). Meanwhile, this has become a concern because the widespread use of instruments that disregard the specificities of sports (Carriedo et al., 2020; Zeferino et al., 2021). Additionally, it is crucial to use specific instruments to the target population with norms to eliminate biases due to various differences (e.g., cultural, linguistic, among others) that can affect results (American Educational Research Association (AERA) et al., 2014), and disregard the specificities, behaviors, and reality of the sports context (Wachelke et al., 2008).

In light of the above, the aim of this study was to identify, through a systematic review, instruments used to measure the aggression by sports fans and analyze their theoretical bases, operational characteristics (e.g., quantity and content of dimensions, population, number of items, and type of response), and psychometric evidence.

Method

A systematic literature review was conducted following the guidelines of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA Statement; Moher et al., 2015) to systematize the review, but reducing biases and enhancing methodological quality. Operational and psychometric characteristics of the reviewed instruments were evaluated based on the study by Silva et al. (2018).

Search and Selection of Instruments

Search was conducted in the following databases, namely, BVS, PsycINFO, PubMed/MedLine, Science Direct, Scopus, and Web of Science, using the following combination of descriptors (only in English) and Boolean operators: scale OR test OR inventory OR questionnaire AND aggression OR violence OR aggressiveness AND spectators OR fans. To ensure methodological rigor, there was a consultation of studies on this topic and keyword indexes as Health Sciences Descriptors (DeCS) and Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) for the selection of descriptors. For each database, article search was conducted independently by two researchers. Additionally, they managed references using EndNote Web®, available at https://www.myendnoteweb.com.

The search was done on December 28, 2021, aiming to identify studies that used scales, inventories, questionnaires, or other measures to assess aggressiveness by fans. It's worth noting that no publication period for studies was delimited to broaden the scope. Furthermore, there was an article reference section tracking that met the eligibility criteria for the review to identify additional studies that were aligned with the proposed objective, the insertion of the inclusion and exclusion criteria.

It is highlighted that the inclusion criteria were: (1) empirical articles and (2) articles that used instruments to assess aggressiveness by fans. The exclusion criteria were: (1) articles published in languages other than Portuguese, English, Spanish, and French; (2) studies with non-psychometric instruments; and (3) studies that presented instruments without the possibility of accessing the full text. The selected articles were read in full and grouped according to the categories of interest (e.g., theory underlying the instrument, dimensionality, target population, type of response scale, type of application, among others).

Definition of Criteria for Psychometric Quality Assessment

In order to identify the psychometric quality of the instruments that were found, scoring criteria were developed following recommendations from the American Educational Research Association, American Psychological Association, and National Council on Measurement in Education (AERA et al., 2014). These criteria classified the instruments according to types of validity and reliability. To accomplish this, a scoring scale (ranging from zero to four points) was used, progressing in quality order. Therefore, the score zero indicated a lack of psychometric evidence, while the score four denoted more robust instruments concerning their validity or reliability. In other words, these instruments employed more modern, advanced, and rigorous statistical methods and analyses. Specifically, in evaluating criterion-related validity and reliability (temporal stability and internal consistency), only three scoring possibilities were adopted (0, 2, and 4). The descriptions used for the instrument classification are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Criteria Definition for Psychometric Characteristics Scoring for the Instruments Analyzed in the Review

Source: Based on the study by Silva et al. (2018)

Notes: 1 Content validity

sources: consistent theoretical basis, use of items validated in other

instruments, instrument analysis by experts, pilot study, semantic analysis of

items; 2Dimensionality and relationships between scores or subscores

of the same inventory; 3Specificities: sports discipline, belonging

to groups of fans.

Results

Regarding the articles that were found, there was total agreement (100%) between the two researchers. With the defined descriptors and operational criteria, 198 studies were identified. After removing duplicates, 155 remained, of which 140 were excluded because: (a) they were not empirical articles (n = 3); (b) there was no access to the instrument (n = 1); (c) they were books or chapters (n = 17); (d) dissertations or theses (n = 2); (e) published in languages other than Portuguese, English, Spanish, or French (n = 5); (f) they addressed other subjects (n = 74); (g) the instrument used was created only for the study and/or did not report the use of at least one psychometric instrument that assessed aggression (n = 10); or (h) they did not measure aggression (n = 28). In total, 15 studies met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1).

Figure 1: Flowchart of the systematic search process (PRISMA)

The methods in the 15 articles were read to identify and count the measurement instruments used to assess aggression and verify the reported psychometric evidence. Seven instruments were identified, namely: (1) Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (BDHI; Buss & Durkee, 1957) (f = 5); (2) Buss and Perry Aggression Questionnaire (BPAQ; Buss & Perry, 1992) (f = 4); (3) Habitus of Chinese Football (HCF; Hu & Cui, 2020) (f = 1); (4) Fan Behavior Measure (FBM; Rocca & Vogl‐Bauer, 1999) (f = 2); (5) Hostile and Instrumental Aggression of Spectators Questionnaire (HIASQ; Wann, Fahl, et al., 1999) (f = 3); (6) Team Sport Club Aggression Scale (TSCAS; Shuv-Ami & Toder-Alon, 2021) (f = 1); and (7) Violence Tendency Scale (VTS; Yalcin et al., 2021) (f = 1). Furthermore, it is noteworthy that in the study by Shuv-Ami and Toder-Alon (2021), three instruments were used. Table 2 presents the study descriptions.

Table 2: Description of studies in which the instruments were initially found

Note: Instrum#: Instrument; BDHI: Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory; BPAQ: Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire; HCF: Habitus of Chinese Football; FBM: Fan Behavior Measure; HIASQ: Hostile and Instrumental Aggression Spectators Questionnaire; TSCAS: Team Sport Club Aggression Scale; VTS: Violence Tendency Scale; * Contributed to the development of items (physical and verbal aggression) for the construction of a new instrument; M; average age; SD: standard deviation.

Additionally, four more instruments were found in other information sources (reference sections of the included studies), namely: (1) Brief Aggression Questionnaire (BAQ; Vitoratou et al., 2009); (2) Competitive Aggressiveness and Anger Scale (CAAS; Maxwell & Moores, 2007); (3) The Reactive-Proactive Questionnaire (RPQ; Raine et al., 2006); and (4) The Verbal Aggression Scale (VAS; Infante & Wigley, 1986). Therefore, a total of 11 instruments was selected for a qualitative analysis of their descriptive and psychometric characteristics.

Operational characteristics of the instruments

Regarding the theoretical foundations, the General Aggression Model (GAM; Anderson & Bushman, 2002) was the most used reference point. Other models such as Social Learning, Neo-Associationist Cognitive Theory, Social Identification, and Practice Theory were also employed. The dimensionality varied; however, the multidimensional format was the most prevalent, and used in six instruments. Among the multidimensional instruments, three of them, Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (Buss & Durkee, 1957), Buss and Perry Aggression Questionnaire (Buss & Perry, 1992), and Brief Aggression Questionnaire (Vitoratou et al., 2009), are "progressive" versions, meaning revised and reduced versions of the original instrument.

The most employed dimensions in the instruments were verbal aggression (f = 5, representing 45% of the instruments) and physical aggression, anger, and hostility (f = 2, equivalent to 18 % of the instruments). Other forms of aggression were also measured by the instruments, but less frequently. In some cases, the measures were more general (e.g., subscales evaluating aggression without differentiation, aggression towards the team and fans, in these cases without reporting the type of behavior). There were also measures/subscales assessing other specificities (e.g., irritability, resentment, emotional reaction, guilt, negativism, tendency, based on the identification with the team, reactions during victories and defeats, etc.).

Regarding the study populations, seven studies specifically focused on sports fans, five of them in soccer (Bensimon & Bodner, 2011; Hu & Cui, 2020; Shuv-Ami & Toder-Alon, 2021; Yalcin et al., 2021; Zeferino et al., 2021), one in hockey (Harrell, 1981), and one in rugby (Moore et al., 2007). Six studies focused on university students (Bernache-Assollant & Chantal, 2009; End & Foster, 2010; Rocca & Vogl‐Bauer, 1999; Wann, 1994; Wann, Carlson et al., 1999; Wann, Fahl, et al., 1999).

There was also a study with a population of men attending a hockey match (Russell & Arms, 1995), students who are supporters of a university basketball (Wann, Carlson, et al., 1999), and parents of young baseball athletes (Hennessy & Schwartz, 2007). Concerning additional instruments (found through other sources of information), one of them investigated competitive athletes (CAAS; Maxwell & Moores, 2007), two of them were about general population (BAQ; Vitoratou et al., 2009; VAS; Infante & Wigley, 1986), and another one was about teenagers (RPQ; Raine et al., 2006). Consequently, those cases in which the sports context was not addressed, the item responses in the measurement instruments might have been influenced by response biases. Also related to the items, the quantity varied from 6 to 75, with the majority of them ranging from 20 to 29.

Regarding the mode of application, all instruments are self-administered. Regarding the type of response, there was some variation, most of them in Likert format (f = 8). Within these eight instruments, in only one of them the answer options ranged from zero to two points, while in the others, they ranged from one to five points. In two instruments, the answer options were scored on an anchoring scale (in one of them, from 1 to 8 points, and in another, from 1 to 10 points), while in one study the answers were dichotomous (where the respondent indicated true or false for the items). Table 3 contains an operational description of the aggressiveness measurement instruments analyzed in this review.

Table 3: Descriptive and operational characteristics of the instruments analyzed in the review

Note: Instrum#: Instrument; BDHI: Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory; BPAQ: Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire; HCF: Habitus of Chinese Football; FBM: Fan Behavior Measure; HIASQ: Hostile and Instrumental Aggression Spectators Questionnaire; TSCAS: Team Sport Club Aggression Scale; VTS: Violence Tendency Scale; BAQ: Brief Aggression Questionnaire; CAAS: Competitive Aggressiveness and Anger Scale; RPQ: Reactive-Proactive Questionnaire; VAS: Verbal Aggression Scale; *MGA: General Aggression Model; * Extra instruments, included by other sources (from the reference section of the initially included studies).

Psychometric Qualities

Psychometric qualities were assessed to determine the accuracy and robustness of the instruments included in this review. The analysis indicated that none of the eleven instruments reached the maximum score (24 points). The highest scores were obtained by the Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (Buss & Perry, 1992), with 19 points, followed by The Reactive-Proactive Questionnaire (Raine et al., 2006) and the Brief Aggression Questionnaire (Vitoratou et al., 2009), both with 18 points. The Competitive Aggressiveness and Anger Scale (Maxwell & Moores, 2007) also scored 17 points. The Verbal Aggression Scale (Infante & Wigley, 1986) received 14 points, while the other instruments presented unsatisfactory psychometric evidence (12 points or less), mainly in construct and criterion validities, as well as reliability in relation to temporal stability.

As for content-based validity evidence, five instruments —Brief Aggression Questionnaire (Vitoratou et al., 2009), Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (Buss & Perry, 1992), Competitive Aggressiveness and Anger Scale (Maxwell & Moores, 2007), Team Sport Club Aggression Scale (Shuv-Ami & Toder-Alon, 2021), and The Reactive-Proactive Questionnaire (Raine et al., 2006)— obtained 3 points, as they presented theoretical bases and used previously tested items. In addition to these instruments, the Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory (Buss & Durkee, 1957) and the Violence Tendency Scale (Yalcin et al., 2021) presented other types of evidence, such as semantic analysis of the items and evaluation by experts, achieving the maximum score, 4 points. The remaining instruments obtained 2 points.

Regarding the evidence of internal structure, only one instrument (HIASQ; Wann, Carlson et al., 1999) did not score, two of them (RPQ; Raine et al., 2006 and VAS; Infante & Wigley, 1986) obtained three points. The other eight reached the full score. Three instruments (BDHI; Buss & Durkee, 1957, HCF; Hu & Cui, 2020 and FBM; Rocca & Vogl‐Bauer, 1999) scored for performing exploratory factor analysis, and three of the, (BAQ; Vitoratou et al., 2009, RPQ; Raine et al., 2006 and VAS; Infante & Wigley, 1986) for conducting confirmatory factor analysis. Four instruments (BPAQ; Buss & Perry, 1992, CAAS; Maxwell & Moores, 2007, TSCAS; Shuv-Ami & Toder-Alon, 2021 and Yalcin et al., 2021) employed both factor analysis methods. In addition, the Brief Aggression Questionnaire (Vitoratou et al., 2009) used Item Response Theory (IRT), and the Team Sport Club Aggression Scale (Shuv-Ami & Toder-Alon, 2021) employed nomological network. Structural equation modeling was applied at two scales (CAAS; Maxwell & Moores, 2007 and TSCAS; Shuv-Ami & Toder-Alon, 2021).

As for the validity evidence based on the relation to conceptually related constructs, only two instruments (BAQ; Vitoratou et al., 2009 and RPQ; Raine et al., 2006) received the maximum score (four points) because they showed significant correlations with other instruments and were used to validate others. Three other instruments also scored, with The Verbal Aggression Scale (Infante & Wigley, 1986) showing correlations with two measurement instruments (three points), and the Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire (Buss & Perry, 1992) and the Competitive Aggressiveness and Anger Scale (Maxwell & Moores, 2007) having correlations with one instrument (two points). Six instruments were not scored in this evidence of validity.

In the validity analyses based on the relation to the criterion, only the Competitive Aggressiveness and Anger Scale (Maxwell & Moores, 2007) and The Reactive-Proactive Questionnaire (Raine et al., 2006) achieved the maximum score. These two instruments were subjected to comparative analyses of sports specificities and associations with variables such as age, gender, education and/or socioeconomic status. The Brief Aggression (Vitoratou et al., 2009) and Buss-Perry Aggression (Buss & Perry, 1992) questionnaires, as well as The Verbal Aggression Scale (Infante & Wigley, 1986), received two points due to comparisons of respondents' means and gender differences. The other six instruments did not score in this evidence of validity.

Evidence of reliability was assessed by two methods: temporal stability and internal consistency. Regarding temporal stability, three instruments (BPAQ; Buss & Perry, 1992, CAAS; Maxwell & Moores, 2007 and VAS; Infante & Wigley, 1986) achieved the maximum score, presenting satisfactory indicators as expected (correlation above 0.7). The Brief Aggression Questionnaire (Vitoratou et al., 2009) also scored on this evidence, but its values were below 0.7, obtaining only 2 points. The other instruments did not score. In the second method (internal consistency), two instruments (CAAS; Maxwell & Moores, 2007 and VAS; Infante & Wigley, 1986) did not receive scores, and two studies (BDHI; Buss & Durkee, 1957 and BAQ; Vitoratou et al., 2009) presented values below 0.7, obtaining 2 points. The other seven instruments reached the total score (four points), as they demonstrated internal consistency above 0.7 for the dimensions of the instrument. Table 4 shows the scores (partial and total) of each instrument analyzed.

Table 4: Score of the psychometric evidence of the instruments present in the review

Notes: Instrum #; BDHI: Buss-Durkee Hostility Inventory; BPAQ: Buss-Perry Aggression Questionnaire; HCF: Habitus of Chinese Football; FBM: Fan Behavior Measure; HIASQ: Hostile and Instrumental Aggression Spectators Questionnaire; TSCAS: Team Sport Club Aggression Scale; VTS: Violence Tendency Scale; BAQ: Brief Aggression Questionnaire; CAAS: Competitive Aggressiveness and Anger Scale; RPQ: Reactive-Proactive Questionnaire; VAS: Verbal Aggression Scale; *Instruments included after inclusion criteria.