10.22235/cp.v18i1.3103

Centralidad y asociaciones entre la tríada oscura, inteligencia emocional rasgo y distancia social durante la pandemia de COVID-19 en Perú: un análisis de redes

Centrality and associations between the dark triad, trait emotional intelligence and social distancing during COVID-19 pandemic in Peru: a network analysis

Centralidade e associações entre a tríade sombria, traço de inteligência emocional e distância social durante a pandemia de COVID-19 no Peru: uma análise de redes

Dennis Calle1 ORCID 0000-0001-9859-3446

Cristian Ramos-Vera2 ORCID 0000-0002-3417-5701

Antonio Serpa-Barrientos3 ORCID 0000-0002-7997-2464

1 Universidad Cesar Vallejo, Perú, [email protected]

2 Universidad Cesar Vallejo, Perú

3 Sociedad Peruana de Psicometría; Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Perú

Resumen:

Pocos estudios en Sudamérica han examinado rasgos de personalidad que tuvieron impacto a nivel individual y social durante la pandemia. El objetivo del estudio fue identificar las variables centrales y asociaciones parciales en una red entre la tríada oscura, inteligencia emocional rasgo y distancia social durante la pandemia, y variables demográficas. Se hipotetizó a la edad como posible variable central en la red, y la relación negativa entre la tríada oscura con la distancia social y la inteligencia emocional rasgo, excepto el narcisismo. Se utilizó un muestreo no probabilístico donde participaron 311 adultos (M = 33.95 años, 65 % mujeres). Mediante encuestas en línea, se aplicaron las escalas Dirty Dozen Dark Triad, Trait Meta-Mood Scale y datos demográficos. La atención emocional fue clave al conectar la tríada oscura y la inteligencia emocional. Además, favoreció la adherencia a la distancia social, mientras lo inverso sucedió con el maquiavelismo. Los dominios de la tríada oscura e inteligencia emocional tuvieron asociación negativa, excepto por el narcisismo, que mostró una conexión positiva con la atención emocional. En síntesis, durante la pandemia, la evaluación de la atención a las emociones fue crucial para entender las motivaciones aversivas sociales y promover la adhesión al distanciamiento social. En contraste, debe investigarse más el maquiavelismo, que se asoció a los jóvenes, y no contribuyó a la normativa social de salud pública.

Palabras clave: tríada oscura; inteligencia emocional rasgo; distancia social; Perú; análisis de red.

Abstract:

Few studies in South America have examined personality traits that had an impact at an individual and social level during the pandemic. The aim of the study was to identify the most central variables and partial associations in a network among the dark triad, trait emotional intelligence, social distancing during the pandemic, and demographic variables. Age was hypothesized as a possible central variable in the network, and a negative relationship was found between the dark triad and social distancing and trait emotional intelligence, except for narcissism. A non-probabilistic sampling method was used, with 311 adults (M = 33.95 years, 65 % women). Online surveys as the Dirty Dozen Dark Triad, Trait Meta-Mood Scale, and demographic data were used. Emotional attention played a key role in linking the dark triad and emotional intelligence. Moreover, it favored adherence to social distancing, while the reverse was observed with Machiavellianism. Finally, dark triad and emotional intelligence domains showed a negative association, except for narcissism, which had a positive connection with emotional attention. In summary, during the pandemic, assessing emotional attention was crucial to comprehend social aversive motivations and promote adherence to social distancing. In contrast, Machiavellianism, associated with the youth, needs further investigation and did not contribute to public health social norms.

Keywords: dark triad; trait emotional intelligence; social distancing; Peru; network analysis.

Resumo:

Poucos estudos na América do Sul examinaram os traços de personalidade que foram impactados a nível individual e social durante a pandemia. O objetivo do estudo foi identificar as variáveis centrais e associações parciais em uma rede entre a tríade sombria, o traço de inteligência emocional, o distanciamento social durante a pandemia e variáveis demográficas. As hipóteses foram de que a idade era uma possível variável central na rede, e de que havia uma relação negativa entre a tríade sombria e o distanciamento social e o traço de inteligência emocional, exceto para o narcisismo. Foi utilizado um método de amostragem não probabilístico, com a participação de 311 adultos (M = 33,95 anos, 65 % mulheres). Por meio de pesquisas online, foram aplicadas as escalas Dirty Dozen Dark Triad, Trait Meta-Mood Scale e dados demográficos. A atenção emocional foi fundamental ao conectar a tríade sombria e a inteligência emocional. Além disso, favoreceu a adesão ao distanciamento social, enquanto o inverso foi observado com o maquiavelismo. Os domínios da tríade sombria e da inteligência emocional tiveram associação negativa, exceto pelo narcisismo, que apresentou uma conexão positiva com a atenção emocional. Em resumo, durante a pandemia, a avaliação da atenção às emoções foi crucial para compreender as motivações sociais aversivas e promover a adesão ao distanciamento social. Em contraste, é necessário investigar mais o maquiavelismo, que se associou aos jovens, e não contribuiu para as normativas sociais de saúde pública.

Palavras-chave: tríade sombria; traço de inteligência emocional; distanciamento social; Peru; análise de rede.

Recibido: 20/10/2022

Aceptado: 20/12/2023

La exploración de la personalidad es una práctica fundamental en el ámbito psicológico, pues revela una sinergia de patrones comportamentales, afectivos, motivacionales, y otros, con un propósito definido (Roberts & Woodman, 2017). Entre estas tendencias, se ha reportado un aumento de aquellas con orientación hacia la manipulación e insensibilidad, no necesariamente patológicas, pero que a menudo no reciben la debida atención a pesar de su posible impacto en contextos que requieren interacciones sociales constructivas (Zettler et al., 2021). En particular, en el contexto de pandemia por COVID-19 surgió la necesidad de detectar y evaluar tendencias interpersonales de baja respuesta a diversas medidas preventivas de salud pública (Ścigała et al., 2021). En esta situación de crisis e incertidumbre, muchas personas no actuaron con empatía frente a las necesidades de otros. Esto fue especialmente relevante en el caso de Perú, que en tal periodo tuvo altas tasas de contagio, mortalidad y organización sanitaria deficiente (Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe (CEPAL), 2022). Incluso, hubo cierta predisposición de beneficiarse de productos médicos esenciales a expensas de otros e incumplir normas sanitarias para frenar la propagación del virus (Cuba, 2021; Ministerio del Interior, 2021). Muchos de estos comportamientos pueden obstaculizar aún más la recuperación en materia de economía y salud pública asociadas a la COVID-19 (Nemexis, 2020; Ścigała et al., 2021).

Al respecto, se ha reportado que los rasgos maquiavélicos, psicopáticos y narcisistas pueden ser claves para predecir una baja adherencia a medidas sanitarias (Doerfler et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2021; Ścigała et al., 2021). Este conjunto de rasgos engloba un modelo teórico denominado “tríada oscura de personalidad”, el cual surgió al integrar en la literatura las tendencias con características aversivas interpersonales y baja empatía en situaciones cotidianas (Rogoza & Cieciuch, 2020). No obstante, estos rasgos no implican necesariamente la presencia de un trastorno o psicopatología, pues se manifiestan a lo largo de un continuo en la vida (Muris et al., 2017; Paulhus & Williams, 2002).

El maquiavelismo engloba una disposición interpersonal de manipulación a largo plazo, cierto desapego emocional y desafío a las normas sociales con la finalidad de obtener beneficios o ventajas sobre otros (Götz et al., 2020). Dadas estas características, se ha sugerido que este rasgo es uno de los más transgresores de normas durante la pandemia, tales como el incumplimiento de la distancia social, la falta de higiene de manos, estafas a personas enfermas y la resistencia a seguir mensajes preventivos relacionados con la COVID-19 (Blagov, 2021; Huang et al., 2021; Triberti et al., 2021). La psicopatía primaria implica comportamientos insensibles, manipuladores, relaciones superficiales, ausencia de miedo y ansiedad ante situaciones de riesgo (Del Gaizo & Falkenbach, 2008). Este rasgo no se limita a contextos criminales, sino que se observan en entornos financieros y políticos donde las personas tienden a ocultar sus motivaciones personales de manera efectiva (LeBreton et al., 2006). Durante la pandemia, la psicopatía se ha implicado en el desinterés por la vida de los afectados, menor adhesión a medidas como el confinamiento y distanciamiento social (Blagov, 2021; Carvalho & Machado, 2020; Doerfler et al., 2021). Por otra parte, el perfil narcisista subclínico se caracteriza por arrogancia, necesidad de admiración, atención y éxito (Ash et al., 2023). Por ello, demuestra un mayor deseo de contacto social, lo que puede generar una impresión inicial de carisma (Malkin et al., 2013). Estudios previos sugieren que individuos narcisistas promovieron teorías conspirativas sobre la COVID-19 y mostraron menos adherencia al distanciamiento social. Sin embargo, priorizaron los protocolos de higiene y uso de mascarillas, lo que sugiere mayor importancia al propio bienestar que al cuidado de los demás (Grubbs et al., 2022; Sternisko et al., 2021).

Debido a las características de estilo de vida oportunista de estos rasgos, es más probable que se expresen principalmente en entornos donde existe cierta inestabilidad e impredecibilidad (Jonason et al., 2020). Este puede ser el caso de Perú, un país con bajas expectativas de cambio social frente a la desigualdad en la población y gran desconfianza hacia las autoridades por temas de inseguridad ciudadana y corrupción política constantes (Instituto Nacional de Estadística (INEI), 2020a). Esto puede fomentar motivaciones para ignorar normas y derechos de los demás, ya que las exigencias de supervivencia de un individuo o grupos con intereses comunes (familias, amigos, instituciones, etc.) prevalecen sobre las reglas que se han establecido para toda una sociedad (Villegas, 2011; Zitek & Schlund, 2021). En ese sentido, los rasgos de tríada oscura pueden persistir en contextos donde los beneficios de obtener ventajas de otros superen a los riesgos percibidos, de modo que es importante evaluarlos en función del entorno (Brito-Costa et al., 2021).

En contraste, durante la crisis de COVID-19, es crucial analizar qué disposiciones afectivas pueden promover comportamientos más empáticos y considerados. En ese sentido, es relevante investigar las bases de autoconocimiento emocional, ya que actúan como antecedentes de la empatía. En diversos estudios, las disposiciones de autoevaluación emocional suelen predecir significativamente mayor perspectiva y preocupación empática (Fernández-Abascal & Martín-Díaz, 2019; Jiménez Ballester et al., 2022; Pacheco & Berrocal, 2004). Esto es coherente, ya que estar dispuestos a reflexionar sobre las propias emociones es el primer paso para comprender cómo otros pueden reaccionar ante experiencias similares. En esa línea, la inteligencia emocional promueve el bienestar psicológico y las relaciones interpersonales (Fernández-Berrocal et al., 2012). Desde la perspectiva de rasgos de Salovey et al. (1995), la inteligencia emocional rasgo son patrones afectivos de naturaleza intrapersonal, es decir, percibir, comprender y manejar las propias emociones de forma efectiva. La atención emocional es la autoevaluación, conciencia de la intensidad y el primer paso para usar la información emocional de manera útil (Salovey et al., 1995). La claridad emocional engloba creerse capaz de diferenciar y precisar los motivos de los cambios de los estados afectivos (Boden & Thompson, 2017). Por último, la reparación emocional es la disposición de abordar las emociones de manera constructiva tras experimentar situaciones conflictivas o eventos que generan malestar (Fernández-Berrocal et al., 2004).

Durante la pandemia hubo reportes de la importancia de evaluar la atención emocional. Por ejemplo, se incrementó a comparación de periodos anteriores al surgimiento de la COVID-19, y fue proporcional a los altos niveles de ansiedad durante este período (Castro & Dueñas, 2022; Panayiotou et al., 2021). Además, tal atención a la propia experiencia afectiva favoreció una mayor inclinación a buscar apoyo emocional en los demás (Prentice et al., 2020). En contraposición, menor predisposición para identificar y regular las emociones se ha vinculado con una reducción de la calidad de vida durante esta crisis sanitaria (Pallotto et al., 2021; Panayiotou et al., 2021). Aunque no se ha examinado explícitamente la relación entre la inteligencia emocional y el cumplimiento de medidas de salud a excepción de otros años (Sánchez López et al., 2018), los trabajos anteriores sugieren que las personas más conscientes de sus experiencias emocionales tienden a reflexionar más sobre sus acciones y decisiones, lo que posiblemente incida en mayor adherencia con las medidas señaladas.

Respecto a la exploración conjunta entre los rasgos de tríada oscura con las puntuaciones totales de inteligencia emocional rasgo, existen dos metaanálisis donde se informa que el maquiavelismo y la psicopatía tienen relación negativa con tal dominio emocional general, mientras el narcisismo tiene asociación nula o positiva (Miao et al., 2019; Michels & Schulze, 2021). No obstante, cuando se profundizan estas asociaciones por cada componente, se obtiene información más diferenciada. Por ejemplo, los individuos con mayor tendencia al maquiavelismo parecen no tener problemas con percibir las propias emociones, sin embargo, tienen dificultades para discernir entre ellas y regular las emociones negativas (Al Aïn et al., 2013; Bonfá-Araujo & Hauck Filho, 2023; García et al., 2015). Los individuos con altas puntuaciones de psicopatía parecen presentar dificultades más notables, ya que aparte de no regular emociones negativas, tampoco suelen atender o diferenciar las propias emociones (Malterer et al., 2008; Newman & Lorenz, 2003). Adicionalmente, la evidencia es mixta en aquellos con tendencias narcisistas grandiosas, pues se han relacionado con autopercepciones emocionales positivas (Casale et al., 2019; Petrides, 2011; Ruiz et al, 2012), pero una revisión metaanalítica sugiere que las asociaciones con los rasgos emocionales son nulas (Miao et al., 2019). En general, se requiere evaluar componentes emocionales por separado para observar qué atributos emocionales están más asociados a cada dominio de tríada oscura.

La edad y el sexo también son variables importantes para comprender las conexiones entre los rasgos de personalidad, ya que influyen en el desarrollo biopsicosocial de las personas (Goldberg et al., 1998). Entre las dos variables, la edad parece condicionar más consistentemente la expresión de cada rasgo examinado, ya que en estudios longitudinales se ha asociado tanto con una mayor manifestación de rasgos oscuros en jóvenes (Hartung et al., 2022) y con una mejor disposición para evaluar, discernir y mejorar los estados emocionales a mayor edad (Parker et al., 2021). En cuanto al sexo, los varones tienden a tener puntajes más altos en rasgos de tríada oscura en comparación con las mujeres, pero las diferencias de sexo en inteligencia emocional no son claras, excepto en la atención emocional, expresado más en mujeres (Sánchez Núñez et al., 2008). Respecto a otros estudios, un metaanálisis reciente señala que la relación entre la psicopatía y la inteligencia emocional es más fuerte cuando hay menos participantes mujeres, y que el vínculo negativo entre el maquiavelismo y la inteligencia emocional es más alto en grupos de menor edad (Michels & Schulze, 2021). Así, estos hallazgos sugieren la necesidad de considerar las variables sociodemográficas en investigaciones sobre rasgos emocionales y antagonistas.

En conjunto, existen razones para sugerir que la inteligencia emocional rasgo y la tríada oscura pueden examinarse en un modelo con un origen común y no como variables aisladas. En la literatura se reporta que la inteligencia emocional, evaluada como rasgo, presenta correlaciones más robustas con la extraversión y el neuroticismo del modelo Big Five, a comparación del modelo de inteligencia como habilidad emocional (Sánchez-García et al., 2016). En ese contexto, la inteligencia emocional rasgo parece orientarse hacia el éxito de las interacciones sociales, al mismo tiempo que fomenta una tendencia hacia la autoconciencia y la gestión efectiva de la emocionalidad negativa (Alegre et al., 2019). Paralelamente, los rasgos antagonistas también tienen asociaciones significativas con rasgos del Big Five como baja amabilidad y conciencia (Muris et al., 2017). Estos hallazgos sugieren que la inteligencia emocional rasgo y tríada oscura tienen una base subyacente de otras manifestaciones de rasgos de personalidad y es plausible integrarlas al mismo nivel. Así, es posible evaluar un sistema de relaciones múltiples constituido por rasgos de personalidad aversivos interpersonales (tríada oscura) y emocionales (inteligencia emocional rasgo) al mismo nivel de organización (Cramer et al., 2012).

Esta perspectiva es viable a través del análisis de redes, que permite examinar variables psicológicas complejos que abarcan relaciones simultáneas entre comportamiento, afecto, cognición y otros aspectos que conforman la personalidad. Algunas ventajas de este modelo incluyen asociaciones parciales que controlan la varianza compartida entre variables psicológicas, demográficas y nominales (Epskamp & Fried, 2018), además de identificar los dominios más relevantes, según la fuerza y número de conexiones en la red, útiles para sugerir acciones preventivas o de intervención (Jones et al., 2021). Complementariamente, cuando se añaden variables demográficas, se puede abordar un sistema de interacción desde el modelo socioecológico de Bronferbrenner (Crawford, 2020). En el contexto del presente estudio, se examina tal modelo como la interacción compleja entre factores individuales (sexo, edad, personalidad), relaciones cercanas y comunitarias (interacciones sociales constructivas o perjudiciales), y factores sociales más amplios (normas sociales y pautas sanitarias ante la COVID-19) para comprender interacciones entre subsistemas.

Objetivos e hipótesis del presente estudio

Dado que la literatura mencionada sugiere que la edad tiene asociaciones significativas tanto con la expresión de rasgos de tríada oscura, así como de inteligencia emocional, se plantea a la edad, incluso durante la pandemia, como una de las variables más centrales (más conexiones y magnitud de relaciones) en toda la red. Esta hipótesis parece más probable de confirmar que otras, pues la mayoría de los estudios no relacionan componentes específicos de inteligencia emocional, lo que dificulta encontrar un patrón emocional consistente con todos los rasgos aversivos. No obstante, en esa línea, sí existe concordancia en la literatura entre la dirección de las asociaciones entre rasgos aversivos y emocionales, y es posible plantear una segunda hipótesis: vale decir, que principalmente la psicopatía, además del maquiavelismo, tienen relación negativa con los componentes de inteligencia emocional rasgo, a excepción del narcisismo.

Por tanto, el primer objetivo del presente estudio fue identificar las variables con mayor centralidad durante la pandemia en un modelo de relaciones de red que incluyen la tríada oscura, inteligencia emocional rasgo, la adherencia al distanciamiento social, la edad y el sexo. El segundo objetivo fue ampliar el conocimiento existente sobre la relación entre la tríada oscura, los componentes de inteligencia emocional rasgo, el cumplimiento de medidas como la distancia social y datos demográficos como la edad y el sexo.

Método

Participantes

Los participantes fueron seleccionados a través de muestreo no probabilístico intencional. Los criterios de selección incluyeron la recolección de datos de ciudadanos peruanos mayores de 18 años que residían en Lima durante el período de la pandemia de 2021. Se determinó el tamaño de la muestra teniendo en cuenta un nivel de significancia de .05, con una potencia estadística de .95, un efecto mínimo de tamaño de 0.2 (Ramos-Vera, 2021), que resultó en un mínimo de 200 participantes. No obstante, en el presente estudio se amplió tal número con información previamente analizada sobre rasgos antagonistas de personalidad y rasgos emocionales (Ramos-Vera et al., 2023), esta vez con énfasis en un contexto de pandemia en el Perú. Inicialmente, se contó con un total de 316 participantes; sin embargo, se identificó que 5 tuvieron tendencias lineales en las respuestas, por lo que fueron excluidos del conjunto de datos. Finalmente, 311 adultos peruanos (M = 33.95; DE = 11.6) formaron parte del presente estudio, de los cuales el 65 % fueron mujeres (204) y el 35 % hombres (107). Las edades de los participantes oscilaron entre los 18 a más de 65 años; mientras el grado de instrucción mayoritario fue educación universitaria, con 62 % (194) de los encuestados a comparación de la educación secundaria (38 %, 117).

Instrumentos

Dirty Dozen Dark Triad (DDDT; Jonason & Webster, 2010). Mide tres rasgos de personalidad como el maquiavelismo (tendencias de manipulación, engaño, explotación a otros), psicopatía subclínica (insensibilidad, amoralidad, cinismo y ausencia de remordimiento) y narcisismo subclínico (necesidad de admiración, prestigio, trato especial de otros). La versión del cuestionario adaptada en el medio peruano por Lonzoy et al. (2020) presenta 12 ítems y cinco opciones de respuesta (1: nunca a 5: casi siempre) en formato Likert. La confiabilidad mediante el coeficiente omega en este estudio fue de .82 para el maquiavelismo, .60 en psicopatía subclínica y .80 para narcisismo subclínico. El ajuste del modelo de tres factores con el estimador DWLS que no asume supuestos de normalidad, demostró valores adecuados de CFI = .98, TLI = .98, RMSEA = .06 y SRMR = .06.

Trait Meta Mood Scale (TMMS-24; Fernández-Berrocal et al., 2004). Esta es una escala de 24 ítems en castellano que mide la inteligencia emocional como rasgo mediante 24 ítems en escala Likert (1: nada de acuerdo a 5: totalmente de acuerdo). Se basa en los dominios de atención (grado de atención y reconocimiento de las propias emociones), claridad (grado de comprensión y diferenciación de las emociones) y reparación emocional (cambiar estados emocionales negativos y prolongar los positivos) (Salovey et al., 1995). En este estudio, la confiabilidad de las puntuaciones mediante el coeficiente omega tuvo coeficientes de .83 para atención; .86 en claridad y .81 para reparación emocional. El ajuste del modelo de tres factores con el estimador ya mencionado tuvo índices de ajuste CFI = .96, TLI = .96, RMSEA = .09 y error cuadrático medio (RMR) = .08.

Cuestionario de datos sociodemográficos. Se realizó un cuestionario con datos básicos como la edad, el sexo, el grado de instrucción y el cumplimiento o no de distancia social en los últimos 30 días.

Procedimientos

En el transcurso del segundo semestre del año 2021 se llevó a cabo la presente investigación mediante la utilización de un formulario virtual, distribuido en comunidades de adultos a través de plataformas de redes sociales como Facebook y WhatsApp. Este formulario presentaba información sobre los objetivos del estudio, proporcionando detalles acerca del proceso de recolección de datos confidenciales y anónimos. Tras la finalización de las encuestas, se procedió a depurar y organizar los datos para su posterior análisis estadístico.

Consideraciones éticas

El presente estudio se llevó a cabo siguiendo los lineamientos y aprobación del Comité de Ética de la Universidad César Vallejo (Registro de proyecto I2020120110491919D – 54132). Esto incluye prácticas para garantizar el bienestar, la dignidad y autonomía de los participantes, que incluye la privacidad y la confidencialidad de la información recopilada. Además, se aseguró que la participación era voluntaria y que podían retirarse en cualquier momento sin consecuencias. Los procedimientos mencionados se realizaron de acuerdo con los lineamientos de la Declaración de Helsinki de 1964 y el artículo número 27 del código de ética profesional del Colegio de Psicólogos del Perú.

Análisis de datos

Los análisis se realizaron con el programa R versión 4.2.2 (R Core Team, 2013), y los paquetes estadísticos qgraph (Epskamp et al., 2012), bootnet (Epskamp & Fried, 2023), huge (Jiang et al., 2019), psych (Revelle, 2017), networktools (Jones, 2020) y Clique-Percolation (Lange, 2021). Los datos siguieron una distribución no normal, de modo que se utilizaron estadísticos no paramétricos, como el paquete huge. Se estimó una red que integró las variables de personalidad, el acatamiento de la distancia social durante la pandemia, así como variables demográficas influyentes en la tríada oscura y la inteligencia emocional-rasgo, tales como la edad y el sexo (Fernández-Berrocal et al., 2012; Michels & Schulze, 2021).

En este modelo gráfico, cada elemento se representa por “nodos” (círculos: variables), unidos por “bordes” (líneas: relaciones). Los bordes indican correlaciones parciales regularizadas entre las variables psicológicas, es decir, se controlan las relaciones con otros componentes de la red, lo que evita asociaciones espurias entre ellos (Epskamp & Fried, 2018; Waldorp & Marsman, 2021). Para identificar aquellos dominios con mayor número y magnitud de conexiones que influyen en otras comunidades de la red, se reportaron las medidas de influencia esperada puente (Jones et al., 2021; Ramos-Vera & Serpa-Barrientos, 2022). Igualmente, para reforzar los hallazgos de nodos relevantes en la red, utilizamos el método de Clique-Percolation, que detecta aquellos nodos que pertenecen a varios grupos o comunidades simultáneamente (Lange, 2021). Para ello, se utilizaron los parámetros k = 3, es decir tres o más nodos fuertemente conectados; y el valor I = 0.15, que indica la magnitud de la conexión mínima entre todos los nodos mayores a tres. Por otra parte, el índice de predictibilidad se representa mediante un anillo sobre los nodos, e indica qué variable es más predicha por las restantes (Haslbeck & Waldorp, 2018). Finalmente, las pruebas de bootstrap son análisis post-hoc que se aplicaron para evidenciar la estabilidad de las relaciones, con al menos 1700 muestras de réplicas de relaciones.

Resultados

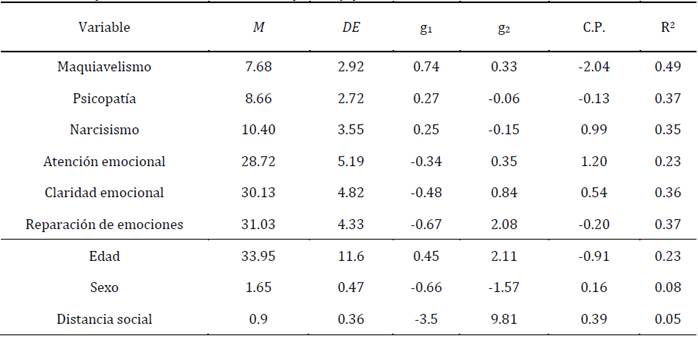

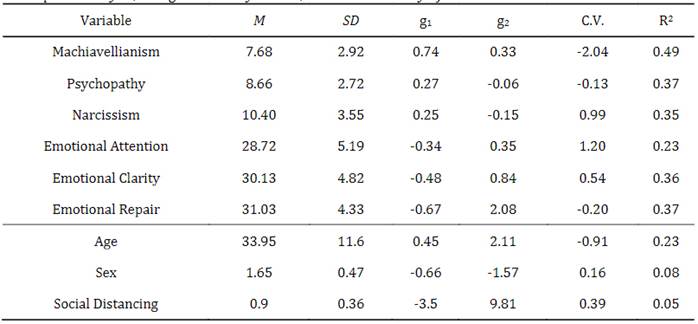

En la Tabla 1 se observan los estadísticos descriptivos de las respuestas de los participantes según las medidas utilizadas en la red estimada. Entre los rasgos de tríada oscura, el narcisismo tuvo la mayor media (10.40), mientras que la reparación emocional tuvo mayor media (31.03) en la inteligencia emocional intrapersonal. El dominio que presentó valores más altos de centralidad puente fue la atención emocional (1.20), seguido por el narcisismo (0.99) y la claridad emocional (0.54). Respecto a la predictibilidad, es decir, los nodos más predichos por otros nodos (R2), el dominio de maquiavelismo tuvo el mayor valor del índice mencionado (49 %), seguido por la psicopatía y reparación emocional (ambos 37 %). En cuanto a la centralidad (influencia esperada puente), se observaron valores superiores de este índice en el componente de la atención emocional (1.20).

Tabla 1: Análisis descriptivos, valores de centralidad puente y predictibilidad de la red

Nota: DE: desviación estándar; g1: asimetría, g2: curtosis, C.P: centralidad puente (bridge expected influence), R2: predictibilidad. Sexo: 1 = hombres, 2 = mujeres

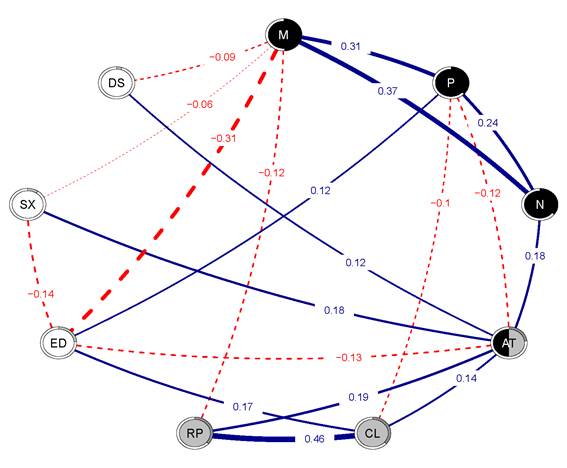

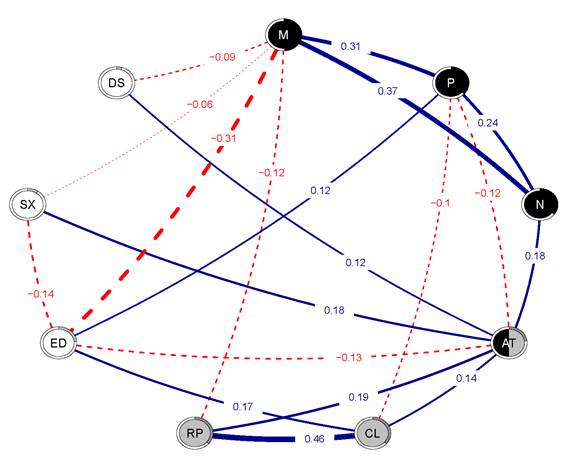

En la Figura 1 se observa la estructura de red de correlaciones parciales entre los rasgos de personalidad ya mencionados, la distancia social y variables demográficas. Resaltan las correlaciones parciales negativas entre la psicopatía subclínica con atención emocional (r = -.12, p < .05) y claridad emocional (r = -.10; p < .05), y positiva con la edad (r= 0.12; p < .05). El maquiavelismo se asoció negativamente con la reparación emocional (r =- .12; p < .05), la edad (r=-0.31; p < .05) y la adherencia a la distancia social (r= -0.09; p < .05); mientras que el narcisismo subclínico tuvo relación positiva con la atención emocional (r = .18; p < .05). Igualmente, se reportan asociaciones positivas entre los rasgos de tríada oscura (r = .24 a .37; p < .05) y entre dimensiones de inteligencia emocional rasgo (r = .14 a .46; p < .05). Por otro lado, la atención emocional se relacionó positivamente con el acatamiento de distancia social (r = .12; p < .05), con el sexo (mujeres, r =.18; p < .05), y negativamente con la edad (r = -0.13; p < .05). Complementariamente, el método Clique-Percolation detectó que la atención emocional perteneció simultáneamente a la agrupación de tríada oscura e inteligencia emocional rasgo.

Figura 1: Asociaciones parciales de red según dimensiones y variables demográficas

Nota: Las líneas continuas representan relaciones positivas, y las líneas cortadas son asociaciones negativas. Los anillos representan el grado de predictibilidad. Nodos negros: tríada oscura; nodos grises: inteligencia emocional rasgo; nodos blancos: variables demográficas y distancia social. M: maquiavelismo, P: psicopatía, N: narcisismo, AT: atención emocional, CL: claridad emocional, RP: reparación emocional, ED: edad, SX: sexo (1: hombre, 2: mujer), DS: adherencia a la distancia social. El nodo gris y negro indica que el nodo de atención emocional está superpuesto a los grupos de tríada oscura e inteligencia emocional.

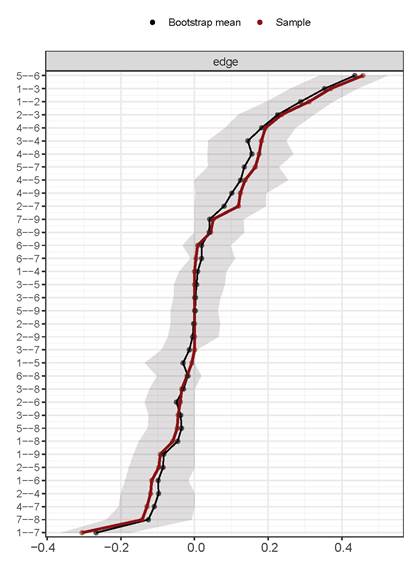

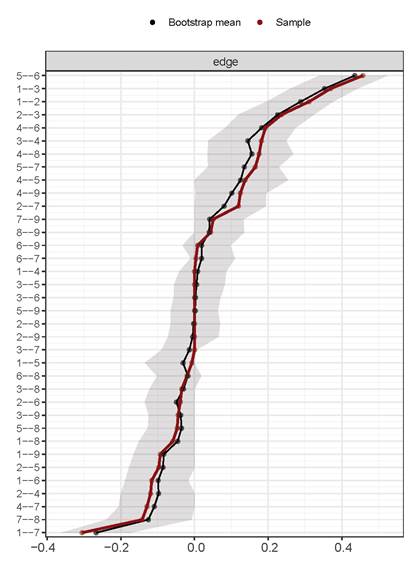

La Figura 2 demuestra la precisión de las asociaciones de red mediante bootstrapping, donde las estimaciones de la muestra del estudio (línea más ancha) coincide con aquellas del remuestreo con 1500 muestras (línea delgada).

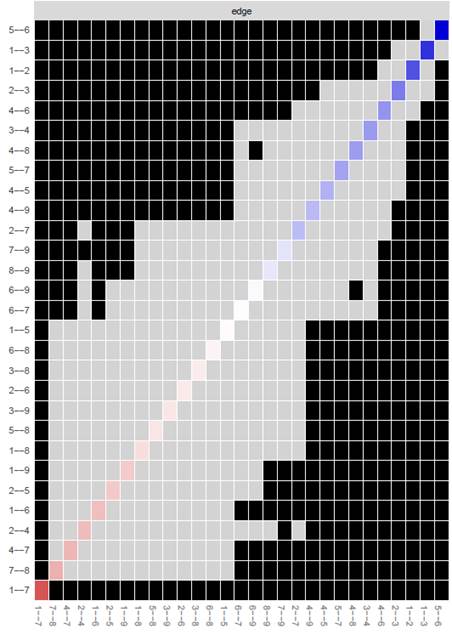

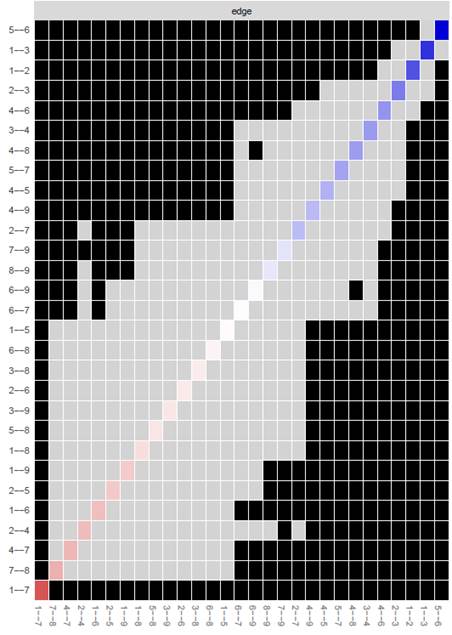

Por último, la Figura 3 indica en las esquinas superiores e inferiores que la conexión positiva significativamente más alta fue entre la claridad y reparación emocional (cuadrado en la esquina superior derecha), y la más alta negativa fue ente el maquiavelismo y edad (cuadrada en la esquina inferior izquierda).

Figura 2: Precisión y estabilidad de las asociaciones de la red estimada

Nota: Precisión de las conexiones en la red. 1: maquiavelismo, 2: psicopatía subclínica, 3: narcisismo subclínico, 4: atención emocional, 5: claridad emocional, 6: reparación emocional, 7: edad, 8: sexo, 9: distancia social. Edge = borde o asociación.

Figura 3: Diferencias de asociaciones en la red

Nota: Diferencias de centralidad de los bordes de la red. 1: maquiavelismo, 2: psicopatía subclínica, 3: narcisismo subclínico, 4: atención emocional, 5: claridad emocional, 6: reparación emocional, 7: edad, 8: sexo, 9: distancia social.

Discusión

El presente estudio tuvo como primer objetivo evaluar las métricas de centralidad en un modelo sistémico de relaciones de red. Esto se aplicó principalmente para identificar cuál es el interconector más relevante en una red compuesta por variables de personalidad como la tríada oscura e inteligencia emocional rasgo y otras variables sociodemográficas. Este enfoque se justifica debido a la compleja naturaleza de las interacciones socioemocionales y su variabilidad en situaciones de crisis, como la pandemia por COVID-19 (Brito-Costa et al., 2021). Dicho análisis es relevante especialmente en un país sudamericano que ha enfrentado considerables desafíos para contener la propagación del virus y experimentó tasas de mortalidad significativamente elevadas incluso a nivel mundial (CEPAL, 2022).

Desde una perspectiva sistémica, entre las variables más importantes que sostuvieron a toda la red mediante sus conexiones, destacamos que no fue solo la edad, como se había planteado, sino que el dominio atención emocional de inteligencia emocional rasgo tuvo el mayor número de conexiones (7 de 8 posibles) con las demás variables en toda la red. A la vez, el método Clique-Percolation detectó que la atención emocional tuvo características superpuestas con el grupo de tríada oscura e inteligencia emocional rasgo. La atención a las emociones implica al menos tres claras características: una orientación hacia la autoevaluación de los procesos emocionales, tomar conciencia de la intensidad de las señales afectivas y representa la fase inicial adaptativa de la información emocional, que repercute en la percepción general de bienestar intrapersonal e interpersonal (Boden & Thompson, 2017).

En ese sentido, la atención emocional funcionó como un “puente” entre los dominios de tríada oscura e inteligencia emocional rasgo, pero también favoreció la adherencia a las medidas de distanciamiento social, así como una mejor predisposición a evaluar las propias emociones en mujeres y en participantes más jóvenes. En primer lugar, esto sugiere que ambas agrupaciones compuestas por rasgos de personalidad tienen características en común con la atención emocional. Por ejemplo, en el presente estudio, el rasgo de autoevaluación o atención intrapersonal tendió un nexo común hacia el narcisismo, ya que este último implica atención prioritaria en la propia imagen y autoevaluación para mantener una percepción positiva de sí mismos ante los demás (Grijalva & Zhang, 2016). Por ello, son plausibles los hallazgos donde se reportan correlaciones positivas entre estas variables en trabajos previos (Ash et al., 2023; Ruiz et al., 2012). En contraste, una menor conciencia de los procesos afectivos internos puede ser una característica distintiva de individuos con niveles elevados de psicopatía, lo que no favorece una adecuada regulación emocional, tal como indican investigaciones previas (Blair & Mitchell, 2009; Malterer et al., 2008).

En segundo lugar, la atención emocional fue importante en el contexto peruano de pandemia, ya que favoreció la adherencia a las medidas de distanciamiento social. En el Perú, el temor al contagio de COVID-19 aumentó proporcionalmente al número de familiares o conocidos afectados y la constante difusión de noticias al respecto (Santa-Cruz-Espinoza et al., 2022). Esto pudo llevar a que las personas más conscientes tanto de su bienestar físico como emocional mostraran una mayor disposición a seguir las medidas de distanciamiento social. De esta manera, no solo buscaban proteger su propio bienestar, sino también el de personas cercanas más vulnerables (Panayiotou et al., 2021). Por otro lado, la atención a las emociones también tuvo conexión negativa con la edad y positiva con el sexo (grupo de mujeres). Con la experiencia, las personas suelen tener mejor autopercepción de las habilidades emocionales, y pueden ser más selectivas en qué preocuparse, en contraste con los jóvenes, quienes tienden a ser más reactivos emocionalmente (Kunzmann et al., 2014). En cuanto a las mujeres, tal asociación podría deberse a la socialización temprana de valorar la expresión emocional más que los hombres, por lo que tendrían más contacto con sus experiencias afectivas. A la vez, esto se refleja en hallazgos en mujeres peruanas sobre mayor atención a emociones negativas durante la pandemia (Fischer & LaFrance, 2015; Pedraz-Petrozzi et al., 2021).

Como segundo objetivo se propuso evaluar las relaciones entre las variables de personalidad mencionadas, el cumplimiento del distanciamiento social y otras medidas sociodemográficas como la edad y el sexo, lo que proporciona una comprensión de las asociaciones más contextualizada con la crisis sanitaria y con factores biosociales subyacentes. Uno de los hallazgos más resaltantes fue que el maquiavelismo se asoció negativamente con acatar la restricción de cercanía social para prevenir la propagación del virus. Si bien tal conexión fue una de las más bajas en toda la red, concuerda con estudios previos donde individuos con altas puntuaciones de maquiavelismo buscan saltarse medidas sanitarias como la distancia social o uso de mascarillas (Chávez-Ventura et al., 2022; Triberti et al., 2021). Estos comportamientos también se han reportado en el contexto peruano donde jóvenes asistían a reuniones sociales clandestinas a pesar de los controles sanitarios (Ministerio del Interior, 2021). Esto último también tiene relevancia con la asociación hallada entre el maquiavelismo y menor edad, pues la transición hacia la adultez puede evidenciar cierta inmadurez al utilizar la manipulación como la forma más fácil para obtener lo que desean sin considerar el riesgo de salud hacia uno mismo y los demás (Götz et al., 2020).

En los hallazgos de asociaciones entre tríada oscura e inteligencia emocional se destaca que los maquiavélicos exhibieron escasos recursos para regular sus emociones negativas. Esto coincide con hallazgos que sugieren que estos individuos utilizan estos estados para reforzar más control y manipulación sobre otros (Abell et al., 2016). Por otra parte, existe evidencia de individuos más maquiavélicos que afrontaron emociones negativas de forma desadaptativa durante la pandemia (Mojsa-Kaja et al., 2021). En tal sentido, utilizaron tácticas como exagerar sus estados afectivos para obtener ventajas económicas de personas vulnerables y así obtener beneficios sin importar la situación de crisis (Hardin et al., 2021). Igualmente, es probable que los rasgos manipuladores hayan desempeñado un papel crucial en la ocurrencia de alta violencia psicológica en Perú durante la pandemia, superando incluso los niveles de violencia física (INEI, 2022b).

En cuanto a los individuos con más prevalencia de rasgos psicopáticos, se asociaron a menor atención emocional y menor claridad emocional. Esto puede evidenciar una orientación hacia la búsqueda de beneficios rápidos que otorgan sensaciones intensas, que es reforzado cuando se ignora la intensidad y el entendimiento de los propios estados afectivos (Malterer et al., 2008; Newman & Lorenz, 2003).

Por último, los individuos narcisistas reportaron mayor atención emocional, en contraste con los demás rasgos aversivos. Esto respalda algunos estudios anteriores que también encontraron esta asociación positiva (Casale et al., 2019; Ruiz et al., 2012), que es coherente con las motivaciones egoístas de atender las propias necesidades (Grijalva & Zhang, 2016), incluso los estados emocionales, sean positivos o negativos. Por tanto, como sugieren otros estudios, cuando la salud está en riesgo, los individuos narcisistas se sienten más amenazados, de modo que priorizan el autocuidado, incluso si es necesario llegar al conflicto con otros o defender creencias conspirativas sobre el origen del virus y su propagación (Grubbs et al., 2022; Hardin et al., 2021; Sternisko et al., 2021).

En cuanto a las limitaciones, los hallazgos no son generalizables a toda la población de estudio, dado el tipo de muestreo y el número de participantes utilizado. En cuanto a la recolección de datos, se basó en un número de participantes de estudios previos de personalidad (Ramos-Vera et al., 2023) y se realizó online por las restricciones de salud en el país. Posteriores estudios deben comprobar si se obtienen los mismos resultados por medios tradicionales como lápiz y papel y en otras muestras. En cuanto a la medida de atención emocional, esta no diferenció en la evaluación de respuestas afectivas positivas o negativas, a fin de una mejor explicación con cada variable. Finalmente, aunque la relación entre el maquiavelismo y la baja adherencia al distanciamiento social fue significativa estadísticamente, las respuestas de cumplimiento a tal medida predominan, así que futuros estudios deben explorar en mayor detalle esa asociación. El presente estudio también es un aporte importante en la literatura de rasgos de personalidad especialmente en el contexto de Hispanoamérica y en pandemia, ya que hasta donde conocemos, existen muy pocos estudios que examinan rasgos dañinos interpersonales y características emocionales.

Conclusión

Los resultados sugieren que la atención emocional fue un componente crucial durante la pandemia en el contexto peruano, que debe explorarse para reducir tendencias manipuladoras e insensibles, y promover el autocuidado en las personas mediante la distancia social, a comparación del maquiavelismo. Sin embargo, también parece haber favorecido tendencias narcisistas para mayor foco en las propias necesidades. En conjunto, parece que es necesario explorar la inteligencia emocional rasgo a través de sus componentes, pues esto ofrece información detallada de cuáles rasgos emocionales pueden prevenir o reforzar tanto los rasgos antagonistas de personalidad, así como las medidas de salud pública durante la pandemia. Por tanto, futuras investigaciones deben profundizar en qué rasgos específicos podría ser más efectivo fomentar las bondades de la autoevaluación emocional. Esto pueden ser útil en nuevos periodos críticos de salud u otros contextos (académicos, laborales, políticos, etc.) para disminuir motivaciones con fines de beneficio personal, tanto en interacciones cara a cara o virtuales.

Referencias

Abell, L., Brewer, G., Qualter, P., & Austin, E. (2016). Machiavellianism, emotional manipulation, and friendship functions in women’s friendships. Personality and Individual Differences, 88, 108-113. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.09.001

Al Aïn, S., Carré, A., Fantini-Hauwel, C., Baudouin, J.-Y., & Besche-Richard, C. (2013). What is the emotional core of the multidimensional Machiavellian personality trait? Frontiers in Psychology, 4. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2013.00454

Alegre, A., Pérez-Escoda, N., & López-Cassá, E. (2019). The relationship between trait emotional intelligence and personality. Is trait EI really anchored within the big five, big two and big one frameworks? Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 866. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00866

Ash, S., Greenwood, D., & Keenan, J. P. (2023). The Neural Correlates of Narcissism: Is There a Connection with Desire for Fame and Celebrity Worship? Brain Sciences, 13(10), 1499. https://doi.org/10.3390/brainsci13101499

Blair, R., & Mitchell, D. (2009). Psychopathy, attention and emotion. Psychological Medicine, 39(4), 543-555. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291708003991

Blagov, P. S. (2021). Adaptive and Dark Personality in the COVID-19 Pandemic: Predicting Health-Behavior Endorsement and the Appeal of Public-Health Messages. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 12(5), 697-707. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550620936439

Boden, M. T., & Thompson, R. J. (2017). Meta-Analysis of the Association Between Emotional Clarity and Attention to Emotions. Emotion Review, 9(1), 79-85. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073915610640

Bonfá-Araujo, B., & Hauck Filho, N. (2023). La capacidad explicativa de la personalidad oscura sobre el rasgo de inteligencia emocional. Revista de Psicología (PUCP), 41(1), 9-29. https://doi.org/10.18800/psico.202301.001

Brito-Costa, S., Jonason, P. K., Tosi, M., Antunes, R., Silva, S., & Castro, F. (2021). COVID-19 and their outcomes: how personality, place, and sex of people play a role in the psychology of COVID-19 beliefs. The European Journal of Public Health, 31(Suppl 2), ckab120.010. https://doi.org/10.1093/eurpub/ckab120.010

Calle, D. (2024, 26 de febrero). Dark triad, trait emotional intelligence and social distancing during COVID-19 pandemic in Peru: A network analysis [Conjunto de datos]. Repositorio OSF. https://osf.io/akzjy/?view_only=1a9f19d885864504af8a711a92a2f3b9

Carvalho, L. D. F., & Machado, G. M. (2020). Differences in adherence to COVID-19 pandemic containment measures: psychopathy traits, empathy, and sex. Trends in Psychiatry and Psychotherapy, 42, 389-392. https://doi.org/10.1590/2237-6089-2020-0055

Casale, S., Rugai, L., Giangrasso, B., & Fioravanti, G. (2019). Trait-emotional intelligence and the tendency to emotionally manipulate others among grandiose and vulnerable narcissists. The Journal of Psychology, 153(4), 402-413. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223980.2018.1564229

Castro, R., & Dueñas, C. (2022). Inteligencia Emocional y Ansiedad en tiempos de pandemia: Un estudio sobre sus relaciones en jóvenes adultos. Revista Ansiedad y Estrés, 28(2), 122-130. https://doi.org/10.5093/anyes2022a14

Chávez-Ventura, G., Santa-Cruz-Espinoza, H., Domínguez-Vergara, J., & Negreiros-Mora, N. (2022). Moral Disengagement, Dark Triad and Face Mask Wearing during the COVID-19 Pandemic. European Journal of Investigation in Health, Psychology and Education, 12(9), 1300-1310. https://doi.org/10.3390/ejihpe12090090

Comisión Económica para América Latina y el Caribe. (2022). Los impactos sociodemográficos de la pandemia de COVID-19 en América Latina y el Caribe (LC/CRPD.4/3). https://www.cepal.org/es/publicaciones/47922-impactos-sociodemograficos-la-pandemia-covid-19-america-latina-caribe

Cramer, A. O. J., Van Der Sluis, S., Noordhof, A., Wichers, M., Geschwind, N., Aggen, S. H., Kendler, K. S., & Borsboom, D. (2012). Dimensions of Normal Personality as Networks in Search of Equilibrium: You Can’t like Parties if you Don’t like People. European Journal of Personality, 26(4), 414-431. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.1866

Crawford, M. (2020). Ecological Systems theory: Exploring the development of the theoretical framework as conceived by Bronfenbrenner. Journal of Public Health Issues and Practices, 4(2), 170. https://doi.org/10.33790/jphip1100170

Cuba, H. (2021). La pandemia en el Perú. Acciones, impactos y consecuencias del Covid-19. Fondo Editorial Comunicacional. https://www.cmp.org.pe/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/La-Pandemia-CUBA-corregida-vale.pdf

Del Gaizo, A. L., & Falkenbach, D. M. (2008). Primary and secondary psychopathic-traits and their relationship to perception and experience of emotion. Personality and Individual Differences, 45(3), 206-212. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2008.03.019

Doerfler, S. M., Tajmirriyahi, M., Dhaliwal, A., Bradetich, A. J., Ickes, W., & Levine, D. S. (2021). The dark triad trait of psychopathy and message framing predict risky decision‐making during the COVID‐19 pandemic. International Journal of Psychology, 56(4), 623-631. https://doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12766

Epskamp, S., Cramer, A. O. J., Waldorp, L. J., Schmittmann, V. D., & Borsboom, D. (2012). qgraph: Network Visualizations of Relationships in Psychometric Data. Journal of Statistical Software, 48, 1-18. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v048.i04

Epskamp, S., & Fried, E. I. (2018). A tutorial on regularized partial correlation networks. Psychological Methods, 23(4), 617-634. https://doi.org/10.1037/met0000167

Epskamp, S., & Fried, E. I. (2023). Package ‘bootnet’. https://mirror.las.iastate.edu/CRAN/web/packages/bootnet/bootnet.pdf

Fernández-Abascal, E. G., & Martín-Díaz, M. D. (2019). Relations between dimensions of emotional intelligence, specific aspects of empathy, and non-verbal sensitivity. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 1066. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.01066

Fernández-Berrocal, P., Berrios-Martos, M. P., Extremera, N., & Augusto, J. M. (2012). Inteligencia emocional: 22 años de avances empíricos. Behavioral Psychology/Psicologia Conductual, 20(1), 5-14.

Fernández-Berrocal, P., Extremera, N., & Ramos, N. (2004). Validity and Reliability of the Spanish Modified Version of the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. Psychological Reports, 94(3), 751-755. https://doi.org/10.2466/pr0.94.3.751-755

Fischer, A., & LaFrance, M. (2015). What drives the smile and the tear: Why women are more emotionally expressive than men. Emotion Review, 7(1), 22-29. https://doi.org/10.1177/1754073914544406

García, D., Adrianson, L., Archer, T., & Rosenberg, P. (2015). The Dark Side of the Affective Profiles: Differences and Similarities in Psychopathy, Machiavellianism, and Narcissism. SAGE Open, 5(4), 2158244015615167. https://doi.org/10.1177/2158244015615167

Goldberg, L. R., Sweeney, D., Merenda, P. F., & Hughes Jr, J. E. (1998). Demographic variables and personality: The effects of gender, age, education, and ethnic/racial status on self-descriptions of personality attributes. Personality and Individual Differences, 24(3), 393-403. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-8869(97)00110-4

Götz, F. M., Bleidorn, W., & Rentfrow, P. J. (2020). Age differences in Machiavellianism across the life span: Evidence from a large‐scale cross‐sectional study. Journal of Personality, 88(5), 978-992. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12545

Grijalva, E., & Zhang, L. (2016). Narcissism and Self-Insight: A Review and Meta-Analysis of Narcissists’ Self-Enhancement Tendencies. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 42(1), 3-24. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167215611636

Grubbs, J. B., James, A. S., Warmke, B., & Tosi, J. (2022). Moral grandstanding, narcissism, and self-reported responses to the COVID-19 crisis. Journal of Research in Personality, 97, 104187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2021.104187

Hardin, B. S., Smith, C. V., & Jordan, L. N. (2021). Is the COVID-19 pandemic even darker for some? Examining dark personality and affective, cognitive, and behavioral responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. Personality and Individual Differences, 171, 110504. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110504

Hartung, J., Bader, M., Moshagen, M., & Wilhelm, O. (2022). Age and gender differences in socially aversive (“dark”) personality traits. European Journal of Personality, 36(1), 3-23. https://doi.org/10.1177/0890207020988435

Haslbeck, J. M., & Waldorp, L. J. (2018). How well do network models predict observations? On the importance of predictability in network models. Behavior Research Methods, 50, 853-861. https://doi.org/10.18637/jss.v093.i08

Huang, Y., Yang, S., & Dai, J. (2021). Self- versus other-directed outcomes, Machiavellianism, and hypothetical distance in COVID-19 antipandemic messages. Social Behavior and Personality: An International Journal, 49(3), 1-13. https://doi.org/10.2224/sbp.10109

Instituto Nacional de Estadística. (2020a, mayo). Informe Técnico. Perú: Percepción ciudadana sobre gobernabilidad, democracia y confianza en las instituciones. http://m.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/boletines/informe_de_gobernabilidad_may2020.pdf

Instituto Nacional de Estadística (2022b, diciembre). Perú: Feminicidio y violencia contra la mujer 2015-2021. https://www.inei.gob.pe/media/MenuRecursivo/publicaciones_digitales/Est/Lib1876/libro.pdf

Jiang, H., Fei, X., Liu, H., Roeder, K., Lafferty, J., & Wasserman, L. (2019). Huge: High-dimensional undirected graph estimation (R package version 1.3.2).

Jiménez Ballester, A. M., de la Barrera, U., Schoeps, K., & Montoya-Castilla, I. (2022). Emotional factors that mediate the relationship between emotional intelligence and psychological problems in emerging adults. Behavioral Psychology/Psicologia Conductual, 30(1). https://doi.org/10.51668/bp.8322113n

Jonason, P. K., & Webster, G. D. (2010). The dirty dozen: A concise measure of the dark triad. Psychological Assessment, 22(2), 420-432. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019265

Jonason, P. K., Żemojtel‐Piotrowska, M., Piotrowski, J., Sedikides, C., Campbell, W. K., Gebauer, J. E., Maltby, J., Adamovic, M., Adams, B. G., Kadiyono, A. L., Atitsogbe, K. A., Bundhoo, H. Y., Bălțătescu, S., Bilić, S., Brulin, J. G., Chobthamkit, P., Dominguez, A. D. C., Dragova‐Koleva, S., El‐Astal, S.,… Yahiiaev, I. (2020). Country-level correlates of the Dark Triad traits in 49 countries. Journal of Personality, 88(6), 1252-1267. https://doi.org/10.1111/jopy.12569

Jones, P. J. (2020). Package ‘networktools’. https://cran.r-project.org/web/packages/networktools/networktools.pdf

Jones, P. J., Ma, R., & McNally, R. J. (2021). Bridge centrality: A network approach to understanding comorbidity. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 56(2), 353-367. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2019.1614898

Kunzmann, U., Kappes, C., & Wrosch, C. (2014). Emotional aging: A discrete emotions perspective. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, 380. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00380

Lange, J. (2021). CliquePercolation: An R Package for conducting and visualizing results of the clique percolation network community detection algorithm. Journal of Open Source Software, 6, 3210. https://doi.org/10.21105/joss.03210

LeBreton, J. M., Binning, J. F., & Adorno, A. J. (2006). Subclinical Psychopaths. En J. C. Thomas, D. L. Segal, & M. Hersen (Eds.), Comprehensive Handbook of Personality and Psychopathology, Vol. 1: Personality and Everyday Functioning (pp. 388-411). John Wiley & Sons.

Lonzoy, A. C., Dominguez-Lara, S., & Merino-Soto, C. (2020). ¿Inestabilidad en el lado oscuro? Estructura factorial, invarianza de medición y fiabilidad de la Dirty Dozen Dark Triad en población general de Lima. Revista de Psicopatología y Psicología Clínica, 24(3), Art. 3. https://doi.org/10.5944/rppc.24335

Malkin, M. L., Zeigler‐Hill, V., Barry, C. T., & Southard, A. C. (2013). The view from the looking glass: How are narcissistic individuals perceived by others? Journal of Personality, 81(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-6494.2013.00780.x

Malterer, M. B., Glass, S. J., & Newman, J. P. (2008). Psychopathy and trait emotional intelligence. Personality and Individual Differences, 44(3), 735-745. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.10.007

Miao, C., Humphrey, R. H., Qian, S., & Pollack, J. M. (2019). The relationship between emotional intelligence and the dark triad personality traits: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Research in Personality, 78, 189-197. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2018.12.004

Michels, M., & Schulze, R. (2021). Emotional intelligence and the dark triad: A meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 18. 110961. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.110961

Ministerio del Interior (2021, 23 de abril). Más de 13 000 personas fueron detenidas por la PNP en “fiestas covid” a nivel nacional. https://www.gob.pe/institucion/mininter/noticias/484441-mas-de-13-000-personas-fueron-detenidas-por-la-pnp-en-fiestas-covid-a-nivel-nacional

Mojsa-Kaja, J., Szklarczyk, K., González-Yubero, S., & Palomera, R. (2021). Cognitive emotion regulation strategies mediate the relationships between Dark Triad traits and negative emotional states experienced during the COVID-19 pandemic. Personality and Individual Differences, 181, 111018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2021.111018

Muris, P., Merckelbach, H., Otgaar, H., & Meijer, E. (2017). The malevolent side of human nature: A meta-analysis and critical review of the literature on the Dark Triad (Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and Psychopathy). Perspectives on Psychological Science, 12(2), 183-204. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745691616666070

Nemexis. (2020). Fraud's impact on healthcare during COVID-19. Global survey on fraud and corruption affecting healthcare systems during COVID-19 in April 2020. https://nemexis.de/wp-content/uploads/2020/05/NMXS-Survey-Covid-19.pdf

Newman, J. P., & Lorenz, A. R. (2003). Response modulation and emotion processing: Implications for psychopathy and other dysregulatory psychopathology. En R. J. Davidson, K. R. Scherer, & H. H. Goldsmith (Eds.), Handbook of Affective sciences (pp. 904–929). Oxford University Press.

Pacheco, N. E., & Berrocal, P. F. (2004). Inteligencia emocional, calidad de las relaciones interpersonales y empatía en estudiantes universitarios. Clínica y Salud, 15(2), 117-137.

Pallotto, N. J., De Grandis, M. C., & Gago Galvagno, L. G. (2021). Inteligencia emocional y calidad de vida en período de aislamiento social, preventivo y obligatorio durante la pandemia por COVID-19. Acción Psicológica, 18(1), 45-56. https://doi.org/10.5944/ap.18.1.29221

Panayiotou, G., Panteli, M., & Leonidou, C. (2021). Coping with the invisible enemy: The role of emotion regulation and awareness in quality of life during the COVID-19 pandemic. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 19, 17-27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.11.002

Parker, J. D., Summerfeldt, L. J., Walmsley, C., O'Byrne, R., Dave, H. P., & Crane, A. G. (2021). Trait emotional intelligence and interpersonal relationships: Results from a 15-year longitudinal study. Personality and Individual Differences, 169, 110013. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110013

Paulhus, D. L., & Williams, K. M. (2002). The Dark Triad of personality: Narcissism, Machiavellianism, and Psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 36(6), 556-563. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00505-6

Pedraz-Petrozzi, B., Krüger-Malpartida, H., Arevalo-Flores, M., Salmavides-Cuba, F., Anculle-Arauco, V., & Dancuart-Mendoza, M. (2021). Emotional impact on health personnel, medical students, and general population samples during the COVID-19 pandemic in Lima, Peru. Revista Colombiana de Psiquiatría, 50(3), 189-198. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.rcp.2021.04.006

Petrides K. V. (2011). Ability and trait emotional intelligence. En T. Chamorro-Premuzic, S. von Stumm, & A. Furnham (Eds.), The Wiley-Blackwell handbooks of personality and individual differences (pp. 656–678). Wiley Blackwell.

Prentice, C., Zeidan, S., & Wang, X. (2020). Personality, trait EI and coping with COVID 19 measures. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction, 51, 101789. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijdrr.2020.101789

R Core Team. (2013). R: A language and environment for statistical computing (4.0.2). R Foundation for Statistical Computing.

Ramos-Vera, C. (2021). Un método de cálculo de tamaño muestral de análisis de potencia a priori en modelos de ecuaciones estructurales. Revista del Cuerpo Médico Hospital Nacional Almanzor Aguinaga Asenjo, 14(1), 104-105. https://doi.org/10.35434/rcmhnaaa.2021.141.909

Ramos-Vera, C., Calle, D., Calizaya-Milla, Y. E., & Saintila, J. (2023). Network analysis of dark triad traits and emotional intelligence in Peruvian adults. Psychology Research and Behavior Management, 16, 4043-4056. https://doi.org/10.2147/PRBM.S417541

Ramos-Vera, C. & Serpa-Barrientos, A. (2022). El análisis de redes en la investigación clínica. Revista de la Facultad de Medicina, 70(1), e94407. https://doi.org/10.15446/revfacmed.v70n1.94407

Revelle, W. (2017). psych: Procedures for Personality and Psychological Research. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=psych

Roberts, R., & Woodman, T. (2017). Personality and performance: Moving beyond the Big 5. Current Opinion in Psychology, 16, 104-108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2017.03.033

Rogoza, R. & Cieciuch, J. (2020). Dark Triad traits and their structure: An empirical approach. Current Psychology, 39, 1287-1302. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-018-9834-6

Ruiz, E., Salazar, I. C., & Caballo, V. E. (2012). Inteligencia emocional, regulación emocional y estilos/trastornos de personalidad. Behavioral Psychology/Psicología Conductual, 20(2), 281-304.

Salovey, P., Mayer, J. D., Goldman, S. L., Turvey, C., & Palfai, T. P. (1995). Emotional attention, clarity, and repair: Exploring emotional intelligence using the Trait Meta-Mood Scale. En J. W. Pennebaker (Ed.), Emotion, Disclosure, & Health (pp. 125-154). American Psychological Association. https://doi.org/10.1037/10182-006

Sánchez-García, M., Extremera, N., & Fernández-Berrocal, P. (2016). The factor structure and psychometric properties of the Spanish version of the Mayer-Salovey-Caruso Emotional Intelligence Test. Psychological Assessment, 28(11), 1404. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/pas0000269

Sánchez López, M. T., Megías Robles, A., Gómez Leal, R., Gutiérrez Cobo, M. J., & Fernández Berrocal, P. (2018). Relación entre la inteligencia emocional percibida y el comportamiento de riesgo en el ámbito de la salud. Escritos de Psicología (Internet), 11(3), 115-123. https://doi.org/10.5231/psy.writ.2018.2712

Sánchez Núñez, M. T., Fernández-Berrocal, P., Montañés, J. & Latorre, J. M. (2008). Does emotional intelligence depend on gender? The socialization of emotional competencies in men and women and its implications. Electronic Journal of Research in Educational Psychology, 15(6), 455-474.

Santa-Cruz-Espinoza, H., Chávez-Ventura, G., Domínguez-Vergara, J., Araujo-Robles, E. D., Aguilar-Armas, H. M., & Vera-Calmet, V. (2022). El miedo al contagio de covid-19, como mediador entre la exposición a las noticias y la salud mental, en población peruana. Enfermería Global, 21(65), 271-294. https://doi.org/10.6018/eglobal.489671

Ścigała, K. A., Schild, C., Moshagen, M., Lilleholt, L., Zettler, I., Stückler, A., & Pfattheicher, S. (2021). Aversive personality and COVID-19: A first review and meta-analysis. European Psychologist, 26(4), 348-358. https://doi.org/10.1027/1016-9040/a000456

Sternisko, A., Cichocka, A., Cislak, A., & Van Bavel, J. J. (2021). National narcissism predicts the belief in and the dissemination of conspiracy theories during the COVID-19 pandemic: Evidence from 56 countries. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 49(1), 48-65. https://doi.org/10.1177/01461672211054947

Triberti, S., Durosini, I., & Pravettoni, G. (2021). Social distancing is the right thing to do: Dark Triad behavioral correlates in the COVID-19 quarantine. Personality and Individual Differences, 170, 110453. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110453

Villegas, M. G. (2011). Disobeying the law: The culture of non-compliance with rules in Latin America. Wisconsin International Law Journal, 29, 263.

Waldorp, L., & Marsman, M. (2021). Relations between networks, regression, partial correlation, and the latent variable model. Multivariate Behavioral Research, 57(6), 994-1006. https://doi.org/10.1080/00273171.2021.1938959

Zettler, I., Schild, C., Lilleholt, L., Kroencke, L., Utesch, T., Moshagen, M., Böhm, R., Back, M. D., & Geukes, K. (2021). The role of personality in COVID-19-related perceptions, evaluations, and behaviors: Findings across five samples, nine Traits, and 17 criteria. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 13(1), 299-310. https://doi.org/10.1177/19485506211001680

Zitek, E. M., & Schlund, R. J. (2021). Psychological entitlement predicts noncompliance with the health guidelines of the COVID-19 pandemic. Personality and Individual Differences, 171, 110491. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110491

Disponibilidad de datos: El conjunto de datos que apoya los resultados de este estudio se encuentra disponible en el repositorio OSF: https://osf.io/akzjy/?view_only=1a9f19d885864504af8a711a92a2f3b9

Cómo citar: Calle, D., Ramos-Vera, C., & Serpa-Barrientos, A. (2024). Centralidad y asociaciones entre la tríada oscura, inteligencia emocional rasgo y distancia social durante la pandemia de COVID-19 en Perú: un análisis de redes. Ciencias Psicológicas, 18(1), e-3103. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v18i1.3103

Contribución de los autores (Taxonomía CRediT): 1. Conceptualización; 2. Curación de datos; 3. Análisis formal; 4. Adquisición de fondos; 5. Investigación; 6. Metodología; 7. Administración de proyecto; 8. Recursos; 9. Software; 10. Supervisión; 11. Validación; 12. Visualización; 13. Redacción: borrador original; 14. Redacción: revisión y edición.

D. C. ha contribuido en 1, 3, 5, 13, 14; C. R. V. en 6, 10, 13; A. S. B. en 6, 3, 12.

Editora científica responsable: Dra. Cecilia Cracco.

10.22235/cp.v18i1.3103

Original Articles

Centrality and associations between the dark triad, trait emotional intelligence and social distancing during COVID-19 pandemic in Peru: a network analysis

Centralidad y asociaciones entre la tríada oscura, inteligencia emocional rasgo y distancia social durante la pandemia de COVID-19 en Perú: un análisis de redes

Centralidade e associações entre a tríade sombria, traço de inteligência emocional e distância social durante a pandemia de COVID-19 no Peru: uma análise de redes

Dennis Calle1 ORCID 0000-0001-9859-3446

Cristian Ramos-Vera2 ORCID 0000-0002-3417-5701

Antonio Serpa-Barrientos3 ORCID 0000-0002-7997-2464

1 Universidad Cesar Vallejo, Peru, [email protected]

2 Universidad Cesar Vallejo, Peru

3 Sociedad Peruana de Psicometría; Universidad Nacional Mayor de San Marcos, Peru

Abstract:

Few studies in South America have examined personality traits that had an impact at an individual and social level during the pandemic. The aim of the study was to identify the most central variables and partial associations in a network among the dark triad, trait emotional intelligence, social distancing during the pandemic, and demographic variables. Age was hypothesized as a possible central variable in the network, and a negative relationship was found between the dark triad and social distancing and trait emotional intelligence, except for narcissism. A non-probabilistic sampling method was used, with 311 adults (M = 33.95 years, 65 % women). Online surveys as the Dirty Dozen Dark Triad, Trait Meta-Mood Scale, and demographic data were used. Emotional attention played a key role in linking the dark triad and emotional intelligence. Moreover, it favored adherence to social distancing, while the reverse was observed with Machiavellianism. Finally, dark triad and emotional intelligence domains showed a negative association, except for narcissism, which had a positive connection with emotional attention. In summary, during the pandemic, assessing emotional attention was crucial to comprehend social aversive motivations and promote adherence to social distancing. In contrast, Machiavellianism, associated with the youth, needs further investigation and did not contribute to public health social norms.

Keywords: dark triad; trait emotional intelligence; social distancing; Peru; network analysis.

Resumen:

Pocos estudios en Sudamérica han examinado rasgos de personalidad que tuvieron impacto a nivel individual y social durante la pandemia. El objetivo del estudio fue identificar las variables centrales y asociaciones parciales en una red entre la tríada oscura, inteligencia emocional rasgo y distancia social durante la pandemia, y variables demográficas. Se hipotetizó a la edad como posible variable central en la red, y la relación negativa entre la tríada oscura con la distancia social y la inteligencia emocional rasgo, excepto el narcisismo. Se utilizó un muestreo no probabilístico donde participaron 311 adultos (M = 33.95 años, 65 % mujeres). Mediante encuestas en línea, se aplicaron las escalas Dirty Dozen Dark Triad, Trait Meta-Mood Scale y datos demográficos. La atención emocional fue clave al conectar la tríada oscura y la inteligencia emocional. Además, favoreció la adherencia a la distancia social, mientras lo inverso sucedió con el maquiavelismo. Los dominios de la tríada oscura e inteligencia emocional tuvieron asociación negativa, excepto por el narcisismo, que mostró una conexión positiva con la atención emocional. En síntesis, durante la pandemia, la evaluación de la atención a las emociones fue crucial para entender las motivaciones aversivas sociales y promover la adhesión al distanciamiento social. En contraste, debe investigarse más el maquiavelismo, que se asoció a los jóvenes, y no contribuyó a la normativa social de salud pública.

Palabras clave: tríada oscura; inteligencia emocional rasgo; distancia social; Perú; análisis de red.

Resumo:

Poucos estudos na América do Sul examinaram os traços de personalidade que foram impactados a nível individual e social durante a pandemia. O objetivo do estudo foi identificar as variáveis centrais e associações parciais em uma rede entre a tríade sombria, o traço de inteligência emocional, o distanciamento social durante a pandemia e variáveis demográficas. As hipóteses foram de que a idade era uma possível variável central na rede, e de que havia uma relação negativa entre a tríade sombria e o distanciamento social e o traço de inteligência emocional, exceto para o narcisismo. Foi utilizado um método de amostragem não probabilístico, com a participação de 311 adultos (M = 33,95 anos, 65 % mulheres). Por meio de pesquisas online, foram aplicadas as escalas Dirty Dozen Dark Triad, Trait Meta-Mood Scale e dados demográficos. A atenção emocional foi fundamental ao conectar a tríade sombria e a inteligência emocional. Além disso, favoreceu a adesão ao distanciamento social, enquanto o inverso foi observado com o maquiavelismo. Os domínios da tríade sombria e da inteligência emocional tiveram associação negativa, exceto pelo narcisismo, que apresentou uma conexão positiva com a atenção emocional. Em resumo, durante a pandemia, a avaliação da atenção às emoções foi crucial para compreender as motivações sociais aversivas e promover a adesão ao distanciamento social. Em contraste, é necessário investigar mais o maquiavelismo, que se associou aos jovens, e não contribuiu para as normativas sociais de saúde pública.

Palavras-chave: tríade sombria; traço de inteligência emocional; distanciamento social; Peru; análise de rede.

Received: 20/10/2022

Accepted: 20/12/2023

The exploration of personality is a fundamental practice in the psychological field, revealing a synergy of behavioral, affective, motivational, and other patterns with a defined purpose (Roberts & Woodman, 2017). Among these trends, an increase in non-pathological tendencies towards manipulation and insensitivity has been reported, often overlooked despite their potential impact on contexts requiring constructive social interactions (Zettler et al., 2021). Particularly, during the COVID-19 pandemic, there was a need to detect and evaluate interpersonal trends characterized by a low response to various public health preventive measures (Ścigała et al., 2021). In this situation of crisis and uncertainty, many individuals did not act with empathy towards the needs of others. This was particularly relevant in the case of Peru, which, during that period, experienced high infection and mortality rates alongside deficient healthcare organization (Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC), 2022). Furthermore, there was a certain inclination to benefit from essential medical products at the expense of others and disregard health regulations to curb the virus spread (Cuba, 2021; Ministry of Interior, 2021). Many of these behaviors may further hinder the recovery in terms of the economy and public health associated with COVID-19 (Nemexis, 2020; Ścigała et al., 2021).

In this regard, it has been reported that Machiavellian, psychopathic, and narcissistic traits may be crucial in predicting low adherence to health measures (Doerfler et al., 2021; Huang et al., 2021; Ścigała et al., 2021). This set of traits encompasses a theoretical model known as the Dark Triad of personality, which emerged by integrating tendencies with interpersonal aversive characteristics and low empathy in everyday situations into the literature (Rogoza & Cieciuch, 2020). However, they do not necessarily imply the presence of a disorder or psychopathology, as they manifest along a continuum throughout life (Muris et al., 2017; Paulhus & Williams, 2002).

Machiavellianism encompasses an interpersonal disposition of long-term manipulation, emotional detachment, and defiance of social norms to gain benefits or advantages over others (Götz et al., 2020). Given these characteristics, it has been suggested that this trait is one of the most norm-violating during the pandemic, such as non-compliance with social distancing, lack of hand hygiene, frauds targeting individuals who are ill and resistance to preventive messages related to COVID-19 (Blagov, 2021; Huang et al., 2021; Triberti et al., 2021). Primary psychopathy involves insensitive behaviors, manipulative tendencies, superficial relationships, and a lack of fear and anxiety in risky situations (Del Gaizo & Falkenbach, 2008). This trait is not confined to criminal contexts but is observed in financial and political environments where individuals tend to effectively conceal their personal motivations (LeBreton et al., 2006). During the pandemic, psychopathy has been implicated in the disregard for the lives of those affected, lower adherence to measures such as lockdowns, and social distancing (Blagov, 2021; Carvalho & Machado, 2020; Doerfler et al., 2021). On the other hand, subclinical narcissistic profiles are characterized by arrogance, a need for admiration, attention, and success (Ash et al., 2023). Consequently, they demonstrate a greater desire for social contact, potentially creating an initial impression of charisma (Malkin et al., 2013). Previous studies suggest that narcissistic individuals promoted conspiracy theories about COVID-19 and showed less adherence to social distancing. However, they prioritized hygiene protocols and mask use, suggesting a greater emphasis on their own well-being than caring for others (Grubbs et al., 2022; Sternisko et al., 2021).

Due to the opportunistic lifestyle characteristics of these traits, they are more likely to be expressed primarily in environments characterized by certain instability and unpredictability (Jonason et al., 2020). This may be the case in Peru, a country with low expectations of social change in the face of inequality in the population and significant distrust towards authorities due to constant issues of citizen insecurity and political corruption (National Institute of Statistics (INEI), 2020a). This can foster motivations to ignore norms and the rights of others, as the survival demands of an individual or groups with common interests (families, friends, institutions, etc.) prevail over the rules established for an entire society (Villegas, 2011; Zitek & Schlund, 2021). In this sense, dark triad traits may persist in contexts where the benefits of gaining advantages over others outweigh perceived risks, emphasizing the importance of evaluating them in the context (Brito-Costa et al., 2021).

In contrast, during the COVID-19 crisis, it is crucial to analyze which affective dispositions can promote more empathetic and considerate behaviors. In this regard, investigating the foundations of emotional self-awareness is relevant, as they act as antecedents to empathy. In various studies, emotional self-assessment dispositions often significantly predict greater empathetic perspective and concern (Fernández-Abascal & Martín-Díaz, 2019; Jiménez Ballester et al., 2022; Pacheco & Berrocal, 2004). This is consistent since being willing to reflect on one's own emotions is the first step to understanding how others may react to similar experiences. In that line, emotional intelligence promotes psychological well-being and interpersonal relationships (Fernández-Berrocal et al., 2012). From the perspective of Salovey et al. (1995), trait emotional intelligence consists of affective patterns of an intrapersonal nature, i.e., perceiving, understanding, and effectively managing one's own emotions. Emotional attention is self-assessment, awareness of intensity, and the first step to using emotional information effectively (Salovey et al., 1995). Emotional clarity involves believing in the ability to differentiate and specify the reasons for changes in affective states (Boden & Thompson, 2017). Finally, emotional repair is the disposition to address emotions constructively after experiencing conflicting situations or events that generate discomfort (Fernández-Berrocal et al., 2004).

During the pandemic, there were reports highlighting the importance of assessing emotional attention. For instance, it increased compared to periods before the emergence of COVID-19 and was proportionate to high levels of anxiety during this period (Castro & Dueñas, 2022; Panayiotou et al., 2021). Moreover, such attention to one's affective experience favored a greater inclination to seek emotional support from others (Prentice et al., 2020). In contrast, a lower predisposition to identify and regulate emotions has been linked to a reduction in the quality of life during this health crisis (Pallotto et al., 2021; Panayiotou et al., 2021). Although the explicit relationship between emotional intelligence and compliance with health measures has not been explicitly examined, apart from previous years (Sánchez López et al., 2018), previous works suggest that individuals more aware of their emotional experiences tend to reflect more on their actions and decisions, possibly influencing greater adherence to the mentioned measures.

Regarding the joint exploration of dark triad traits with total scores of trait emotional intelligence, two meta-analyses report that Machiavellianism and psychopathy have a negative relationship with this overall emotional domain, while narcissism has a null or positive association (Miao et al., 2019; Michels & Schulze, 2021). However, when these associations are deepened for each component, more differentiated information is obtained. For example, individuals with a higher tendency toward Machiavellianism seem to have no issues perceiving their own emotions; however, they struggle to discern between them and regulate negative emotions (Al Aïn et al., 2013; Bonfá-Araujo & Hauck Filho, 2023; García et al., 2015). Individuals with high psychopathy scores appear to present more notable difficulties, as apart from not regulating negative emotions, they also tend not to attend or differentiate their own emotions (Malterer et al., 2008; Newman & Lorenz, 2003). Additionally, the evidence is mixed for those with grandiose narcissistic tendencies, as they have been linked to positive emotional self-perceptions (Casale et al., 2019; Petrides, 2011; Ruiz et al., 2012), but a meta-analytic review suggests that associations with emotional traits are null (Miao et al., 2019). In general, it is necessary to assess emotional components separately to observe which emotional attributes are more associated with each dark triad domain.

Age and sex are also important variables in understanding connections between personality traits as they influence the biopsychosocial development of individuals (Goldberg et al., 1998). Between the two variables, age consistently appears to condition the expression of each examined trait, as longitudinal studies have associated it with both a higher manifestation of dark traits in young individuals (Hartung et al., 2022) and a better disposition to assess, discern, and improve emotional states at older ages (Parker et al., 2021). Concerning sex, men tend to have higher scores in dark triad traits compared to women, but sex differences in emotional intelligence are not clear, except for emotional attention, expressed more in women (Sánchez Núñez et al., 2008). In line with other studies, a recent meta-analysis points out that the relationship between psychopathy and emotional intelligence is stronger when there are fewer female participants, and the negative link between Machiavellianism and emotional intelligence is higher in younger age groups (Michels et al., 2021). Thus, these findings suggest the need to consider sociodemographic variables in research on emotional and antagonistic traits.