10.22235/cp.v17i2.3053

Adaptação e evidências de validade da Escala de Experiências de Microagressões LGBT no Trabalho para o Brasil

Adaptation and validity evidence of LGBT Microaggression Experiences at Work Scale in Brazil

Adaptación y evidencias de validez de la Escala de Experiencias de Microagresiones LGBT en el Trabajo para Brasil

Pricila de Sousa Zarife1, ORCID 0000-0002-0187-0425

Catarina Ribeiro2, ORCID 0000-0001-9682-9339

1 Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, Brasil, [email protected]

2 Santo Caos Consultoria em Publicidade, Brasil

Resumo:

Esta pesquisa buscou adaptar e obter evidências de validade de estrutura interna da Escala de Experiências de Microagressões LGBT no Trabalho (EEM-LGBT) para o contexto brasileiro. Participaram 226 profissionais que se identificaram como LGBT, com idade média de 28,5 anos (DP = 7,19) que responderam à EEM-LGBT e um questionário sociodemográfico. O processo de adaptação da EEM-LGBT seguiu as etapas de tradução, síntese, avaliação por experts, avaliação pelo público-alvo e tradução reversa. Para avaliar a plausibilidade da estrutura tridimensional (valores no local de trabalho, suposições heteronormativas e cultura cisnormativa) foi realizada análise fatorial confirmatória. A versão em português apresentou IVC adequado, segundo juízes experts. A estrutura tridimensional proposta apresentou um ótimo ajuste aos dados (χ2/gl = 1,22; CFI = 0,994; TLI = 0,993; SRMR = 0,076; RMSEA = 0,031) e bons índices de confiabilidade (alfa de Cronbach e confiabilidade composta ≥ 0,84). A versão adaptada da EEM-LGBT apresentou qualidade satisfatória, tornando-se o primeiro instrumento no contexto brasileiro destinado a investigar experiências de microagressões LGBT no trabalho.

Palavras-chave: discriminação no trabalho; microagressões; diversidade nas organizações; minorias sexuais e de gênero; validade.

Abstract:

This research aimed to adapt and obtain validity evidence of the internal structure of the LGBT Microaggression Experiences at Work Scale (LGBT-MEWS) for the Brazilian context. The sample consisted of 226 professionals who identified themselves as LGBT, with a mean age of 28.5 years (SD = 7.19) who answered the LGBT-MEWS and a sociodemographic questionnaire. The LGBT-MEWS adaptation process followed the stages of translation, synthesis, evaluation by expert judges, evaluation by the target population, and back translation. Confirmatory factor analysis was performed to assess the plausibility of the three-dimensional structure (workplace values, heteronormative assumptions, and cisnormative culture). The Brazilian version presented adequate CVI, according to expert judges. The proposed three-dimensional structure presented an excellent fit to the data (χ2/df = 1.22; CFI = .994; TLI = .993; SRMR = .076; RMSEA = .031), and good reliability indices (Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability ≥ .84). The adapted version of the LGBT-MEWS presented satisfactory quality, making it the first instrument in the Brazilian context to investigate experiences of LGBT microaggressions at work.

Keywords: discrimination at work; microaggressions; diversity in organizations; sexual and gender minorities; validity.

Resumen:

Esta investigación buscó adaptar y obtener evidencias de validez de la estructura interna de la Escala de Experiencias de Microagresiones LGBT en el Trabajo (EEM-LGBT) para el contexto brasileño. Participaron 226 profesionales que se identificaron como LGBT, con una edad media de 28.5 años (DE = 7.19), que respondieron el EEM-LGBT y un cuestionario sociodemográfico. El proceso de adaptación de EEM-LGBT siguió las etapas de traducción, síntesis, evaluación de expertos, evaluación de la audiencia objetivo y retrotraducción. Para evaluar la plausibilidad de la estructura tridimensional, se realizó un análisis factorial confirmatorio. La versión portuguesa presentó CVI adecuado, según los jueces expertos. La estructura tridimensional propuesta presentó un excelente ajuste a los datos (χ2/gl = 1.22; CFI = .994; TLI = .993; SRMR = .076; RMSEA = .031) y buenos índices de confiabilidad (alfa de Cronbach y confiabilidad compuesta ≥ .84). La versión adaptada del EEM-LGBT fue de calidad satisfactoria, lo que lo convierte en el primer instrumento en el contexto brasileño para investigar experiencias de microagresiones LGBT en el trabajo.

Palabras clave: discriminación en el trabajo; microagresiones; diversidad en las organizaciones; minorías sexuales y de género; validez.

Recebido: 20/09/2022

Aceito: 26/10/2023

Mesmo em contextos com legislações protetivas, pessoas LGBT continuam sendo estigmatizadas, especialmente em países com culturas conservadoras (Redcay et al., 2019). Ainda, violências tidas como silenciosas ou sutis têm se tornado cada vez mais frequentes, por não serem denunciadas ou consideradas nos termos da lei (Souza et al., 2017). Dentre as violências sutis estão as microagressões, definidas como abjeções verbais, comportamentais ou ambientais, que transmitem desprezos e insultos e são direcionadas a grupos minorizados, como as pessoas LGBT (Resnick & Galupo, 2019). Mesmo que sutis e breves, elas impactam negativamente suas vítimas, causando baixa autoestima, depressão, traumas (Nadal, 2019), tristeza, afastamento de atividades regulares e ideação ou tentativa de suicídio (Parr & Howe, 2019).

As discriminações sutis contra pessoas LGBT no trabalho costumam ser menos percebidas do que atos de violência física ou sexual (Souza et al., 2017). Todavia, elas podem impactar em sua inserção e permanência no mercado de trabalho, aliadas à negligência de direitos básicos e a vulnerabilidade social. A pessoas transgênero enfrentam ainda mais dificuldades, como altas taxas de desemprego, subemprego e insatisfação no trabalho, além de serem direcionadas a trabalhos informais, autônomos e prostituição (Costa et al., 2020).

Diante de microagressões sofridas no trabalho, pessoas LGBT costumam empregar diferentes estratégias de enfrentamento, como permanecerem passivas diante da agressão (não reagindo e ignorando os comentários negativos, mesmo sendo afetadas negativamente), confrontarem a pessoa agressora (reagindo ativamente e desafiando-a) ou emitindo comportamentos de autoproteção (agirem cautelosamente para garantir sua segurança física, como manter-se atentas ao ambiente) (Nadal et al., 2011; Papadaki et al., 2021). Acerca das possíveis reações cognitivas a tais eventos, elas tendem a aceitar que tais agressões fazem parte da vida de uma pessoa LGB, a buscar se empoderar para responder às pessoas agressoras, ou a assumir sua orientação sexual, caso ainda não o tenham feito (Papadaki et al., 2021).

A literatura que aborda essas discriminações a pessoas LGBT no trabalho e seu impacto ainda é relativamente incipiente (Richard, 2021), mais ainda em se tratando de instrumentos de medida voltados para investigar explicitamente as microagressões direcionadas a esta parcela da população. Os poucos estudos quantitativos tendem a realizar alterações na redação de medidas que investigam discriminação racial, para que possam ser aplicadas às pessoas LGBT (Medina, 2022). Considerando que é de suma importância investigar ocorrência e impacto de tais experiências nas pessoas LGBT, tem-se que os instrumentos de medida especificamente construídos para elas podem constituir uma importante estratégia de investigação.

A Escala de Experiências de Microagressões LGBT no Trabalho/EEM-LGBT (LGBT Microaggression Experiences at Work Scale, LGBT-MEWS) é um instrumento de medida desenvolvido nos Estados Unidos para investigar este tipo de discriminação. Diferentes estratégias foram adotadas em sua elaboração: revisão de literatura, relatos de pessoas LGBT que sofreram microagressões no local de trabalho e análise de instrumentos que investigavam experiências heterossexistas, envolvendo estratégias tanto indutivas quanto dedutivas (Resnick & Galupo, 2019).

Inicialmente, 64 itens foram elaborados e submetidos a investigação de evidências de validade baseadas no conteúdo e de estrutura interna, por meio de análises fatoriais exploratória (AFE) e confirmatória (AFC). A versão final é composta por 27 itens distribuídos em três dimensões com os seguintes índices de índices de ajuste χ2 (321) = 1226,30; p < 0,001; CFI = 0,76; SRMR = 0,08; RMSEA = 0,09; 90 % (0,091, 0,102) e de confiabilidade (alfa de Cronbach) entre 0,82 e 0,93. Apesar de o CFI (Índice de ajuste comparativo) estar abaixo do recomendado, com o SRMR (Raiz quadrada padronizada da média residual), RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) e o intervalo de confiança abaixo de 0,10, houve rejeição do teste de inadequação, indicando o uso do instrumento (Resnick & Galupo, 2019).

O modelo tridimensional oriundo da construção da medida é composto por: (1) valores no local de trabalho, (2) suposições heteronormativas, e (3) cultura cisnormativa. A dimensão valores no local de trabalho está relacionada ao sistema de valores gerais de uma organização, envolvendo as interações interpessoais dos trabalhadores LGBT com seus colegas (como piadas depreciativas e insultos), além de seu status no trabalho relacionado à contratação, promoção, escala de pagamento e segurança no emprego (Resnick & Galupo, 2019). A dimensão suposições heteronormativas descreve o heterossexismo cotidiano no trabalho que invalida a experiência e a identidade dos profissionais LGBT, como pressuposição de que a pessoa é heterossexual e afirmações para marginalizar, invalidar ou desprestigiar suas experiências enquanto pessoa LGBT (Resnick & Galupo, 2019). Vale destacar que, tradicionalmente, tem-se que algumas organizações podem apresentar uma cultura mais heteronormativa do que outros espaços sociais, especialmente quando compostas predominantemente por homens cis heterossexuais (Palo & Jha, 2020). A dimensão cultura cisnormativa está relacionada ao desrespeito à identidade e/ou expressão de gênero da pessoa e como ela é vivenciada no trabalho, reforçando que as pessoas se identificam com o sexo atribuído no nascimento, desconsiderando a multiplicidade de identidades e expressões de gênero. Isto envolve ausência de políticas inclusivas relacionadas com a utilização da banheiros, linguagem neutra e código de vestimenta. Para o modelo, essa separação entre dimensões é de suma importância para reforçar que há diferenças nas microagressões sofridas por pessoas transgênero (Resnick & Galupo, 2019).

Uma pesquisa quantitativa realizada com 325 profissionais LGBT americanos, utilizando a EEM-LGBT, identificou que microagressões predisseram positivamente estresse no trabalho (b = 0,23, p < 0,001), sintomas de estresse (b = 0,05, p < 0,001), de depressão (b = 0,05, p < 0,001) e de ansiedade (b = 0,06, p < 0,001), bem como predisseram negativamente satisfação no trabalho (b = -0,17, p < 0,01). Os resultados também evidenciaram que mesmo as pessoas que não se identificam abertamente como LGBT podem também sofrer discriminação (Richard, 2021).

Outra pesquisa também quantitativa com 88 profissionais americanos cisgêneros e LGB, adotou a EEM-LGBT, identificou as variáveis preocupações com a aceitação (b = 0,24; p = 0,034) e motivação para ocultação da orientação sexual (β = 0,49; p < 0,001) como preditoras de microagressões (F(2, 85) = 9,97; p < 0,001; R2 = 0,19). Ainda, microagressões não predisseram significativamente a satisfação com o relacionamento amoroso (Medina, 2022). Por fim, outra pesquisa quantitativa, realizada com 314 profissionais LGBT residentes no Canadá (66 %) e nos Estados Unidos (34 %) e adotando a EEM-LGBT, identificou alta correlação entre incivilidade (comportamento rude e desrespeitoso) e microagressões (r = 0,64; p < 0,001). Os resultados indicaram que a relação entre microagressões e engajamento no trabalho (b = -0,10; p < 0,05) foi considerada significativa apenas quando em conjunto com outness (grau em que uma pessoa revela sua orientação sexual e/ou identidade de gênero) como uma potencial variável moderadora (Sooknanan, 2023).

Apesar de as pessoas LGBT serem um dos grupos mais marginalizados nas organizações brasileiras, há carência de pesquisas sobre suas vivências no ambiente de trabalho (Zanin, 2019). Quanto às microagressões a pessoas LGBT no trabalho, não há instrumento de medida para investigar sua ocorrência no Brasil, dificultando a identificação da sua ocorrência, os seus impactos e o desenvolvimento de estratégias para impedi-las. Diante de tais lacunas, visando fomentar novos estudos e auxiliar as organizações na gestão da diversidade, esta pesquisa buscou adaptar e obter evidências de validade de estrutura interna da EEM-LGBT para o contexto brasileiro.

A opção pela adaptação de um instrumento internacional foi embasada nas vantagens de tal procedimento em comparação com o desenvolvimento de uma nova medida. Dentre elas, a possibilidade de comparar dados coletados com a mesma medida em amostras de diferentes contextos e populações, tornando a avaliação mais equivalente, e maior capacidade de generalizar dos resultados (Borsa et al., 2012).

Método

Esta seção foi seccionada em duas partes. A primeira delas corresponde ao processo de tradução e adaptação transcultural do instrumento para o contexto brasileiro. A segunda delas corresponde ao processo de busca das evidências de validade de estrutura interna.

Parte 1: Tradução e adaptação transcultural da escala

Autoras da versão original da EEM-LGBT foram consultadas e autorizaram a realização da pesquisa. A adaptação seguiu as seguintes etapas: tradução do instrumento para o novo idioma, síntese das versões traduzidas, avaliação por experts, avaliação pelo público-alvo e tradução reversa (Bandeira & Hutz, 2020; Borsa et al., 2012).

A tradução do instrumento do inglês para o português brasileiro foi realizada por três pessoas nativas em português e fluentes em inglês, estudiosas da área de Psicologia e pertencentes ao público-alvo da pesquisa (dois homens cisgênero gays e uma mulher cisgênero lésbica), selecionadas de forma intencional pela equipe de pesquisa, em decorrência das características supracitadas, e contatadas por e-mail. Posteriormente, a equipe analisou as três versões traduzidas para obtenção de uma única versão, avaliando as discrepâncias semânticas, linguísticas, contextuais e conceituais.

Um comitê de juízes experts avaliou individualmente a equivalência entre a versão traduzida e o instrumento original quanto à equivalência semântica, idiomática, experimental e conceitual. O comitê foi composto por quatro pesquisadores da área de Psicologia (três docentes com doutorado e um mestrando), experientes em construção e adaptação de instrumentos, sendo que dois deles faziam parte do público-alvo da pesquisa, cuja seleção também foi intencional e o contato por e-mail. Os apontamentos foram analisados pela equipe de pesquisa, considerando a equivalência conceitual com a versão original e a proporção de concordância dos juízes, calculada pelo Índice de Validade de Conteúdo (IVC). A interpretação considerou desejável o IVC acima de 0,80 (Alexandre & Coluci, 2011).

Em seguida, quatro pessoas do público-alvo avaliaram a compreensão da versão oriunda da etapa anterior, sendo elas um homem cisgênero gay pós-graduado em Marketing, um homem cisgênero bissexual graduando em Engenharia Mecânica, uma mulher cisgênera lésbica graduanda em Medicina Veterinária e uma mulher transgênero heterossexual com ensino médio completo, cuja amostragem se deu por bola de neve e o contato por e-mail. Elas foram entrevistadas individualmente, lendo em voz alta cada tópico do instrumento e explicando sua compreensão dele. Quando informaram problemas na compreensão, foram solicitadas a sugerir sinônimos e alterações a nível semântico. Ao final, as sugestões foram avaliadas pela equipe de pesquisa considerando clareza, equivalência à versão original e frequência de sugestões de alterações.

Por fim, o instrumento foi traduzido de português para inglês por uma tradutora profissional, nativa em português brasileiro e com nível superior em Psicologia. A versão retrotraduzida foi analisada pela equipe de pesquisa e enviada para as autoras do instrumento original, para identificar inconsistências e erros conceituais entre as versões.

Parte 2: Investigação das evidências de validade de estrutura interna e confiabilidade da EEM-LGBT para o contexto brasileiro

Participantes

Participaram desta pesquisa 226 profissionais LGBT, de 18 a 56 anos (M = 28,50; DP = 7,13), sendo 57,40 % do gênero masculino (n = 128), 38,56 % feminino (n = 86) e 4,04 % não binário (n = 9). Pessoas transgênero ou travestis constituíram 11,95 % (n = 27) da amostra, sendo que 6,64 % (n = 15) delas afirmaram possuir um nome social.

Os(a) participantes se identificaram como gays (51,35 %; n = 114), bissexuais (22,98 %; n = 51), lésbicas (20,72 %; n = 46), pessoas (transgênero) heterossexuais (3,15%; n = 7), assexuais (1,35 %; n = 3), e pansexuais (0,45 %; n = 1). A maioria se declarou branca (61,50 %; n = 139), seguido de parda (25,22 %, n = 57), negra/preta (10,62 %; n = 24), amarela (2,22 %; n = 5) e indígena (0,44 %; n = 1). A maioria residia na região sudeste (80,97 %; n = 183), seguido de sul (7,08%; n = 16), nordeste (5,31 %; N = 12), centro-oeste (4,43 %; n = 10) e norte (2,21 %; n =5), predominantemente em cidades do interior (53,78%; n = 121).

A maioria era solteira (69,91 %; n = 158), vivia com companheiro(a), era casado(a) ou em união estável (28,32 %; n = 64) e separado(a) ou divorciado(a) ou viúvo(a) (1,77 %; n = 4). Predominaram pessoas com ensino superior completo (30,63 %; n = 68), seguido de superior incompleto (27,03 %; n = 60), pós-graduação completa (23,87 %; n = 53), pós-graduação incompleta (11,26 %; n = 25), médio completo (5,86 %; n = 13), médio incompleto (0,90 %; n = 2) e fundamental incompleto (0,45 %; n = 1). Quanto ao tempo de empresa, possuíam de 4 meses a 32 anos (M = 3,16; DP = 4,99).

Instrumento

Escala de Experiências de Microagressões LGBT no Trabalho (EEM-LGBT, LGBT Microaggression Experiences at Work Scale, LGBT-MEWS; Resnick & Galupo, 2019). Instrumento composto por 27 itens distribuídos em três dimensões: valores no local de trabalho (12 itens), suposições heteronormativas (9 itens) e cultura cisnormativa (6 itens). As respostas foram assinaladas em uma escala do tipo Likert de 1 (nunca) a 5 (muito frequente).

Questionário de dados sociodemográficos. Perguntas sobre idade, região do país, cidade, cor da pele, estado civil, escolaridade, tempo de empresa, identidade de gênero, nome social e orientação sexual.

Procedimentos éticos e de coleta de dados

A pesquisa foi realizada respeitando as exigências contempladas na Resolução 510/2016, do Conselho Nacional de Saúde (CNS), que trata da realização de pesquisas envolvendo seres humanos. A coleta de dados foi iniciada após aprovação pelo Comitê de Ética em Pesquisa com Seres Humanos da Universidade Federal de Uberlândia (CAEE: 39232120.2.0000.5152).

Os critérios de inclusão envolviam se identificar como uma pessoa LGBT, ser maior de idade e possuir experiência profissional de, no mínimo, 3 meses. Não foram incluídas pessoas que sem acesso à internet e que se declarassem analfabetas ou com algum comprometimento que impedisse o entendimento do instrumento.

O instrumento foi disponibilizado via internet, por meio de um link virtual (Google Forms) que deu acesso a um formulário online, contendo o Termo de Consentimento Livre e Esclarecido (TCLE), com o objetivo geral da pesquisa, a confidencialidade dos dados e condições para participação, e o questionário da pesquisa. O link foi compartilhado em mídias sociais (Facebook, Instagram e LinkedIn) e enviado a grupos e organizações não governamentais (ONGs) voltados a pessoas LGBT, utilizando o método bola de neve. A coleta de dados ocorreu entre junho e agosto de 2021.

Ao abrir o link, o(a) participante teve acesso à versão online do TCLE. Após a leitura do documento, era necessário assinar a opção obrigatória “Li, compreendi e tenho interesse em participar da pesquisa”, para ter acesso ao questionário. Caso não aceitasse participar, receberia uma mensagem de agradecimento, encerrando sua participação.

Procedimentos de análise de dados

Os dados coletados foram tabulados e analisados no software JASP, versão 0.16. Para avaliar a plausibilidade da estrutura tridimensional, foi realizada análise fatorial confirmatória (AFC). A adoção do método de estimação Robust Diagonally Weighted Least Squares (RDWLS) se deu por sua adequação para dados categóricos (Li, 2016).

Os índices de ajuste e seus valores de referência investigados foram: c2 (não significativo); c2/gl < 3; Comparative Fit Index (CFI > 0,95); Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI > 0,95); Standardized Root Mean Residual (SRMR < 0,08) e Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA < 0,06, com intervalo de confiança (limite superior) < 0,10) (Brown, 2015). A confiabilidade da medida foi investigada pelo alfa de Cronbach e fidedignidade composta, sendo aceitáveis valores acima de 0,70 (Valentini & Damásio, 2016).

Resultados

Parte 1: Tradução e adaptação transcultural da escala

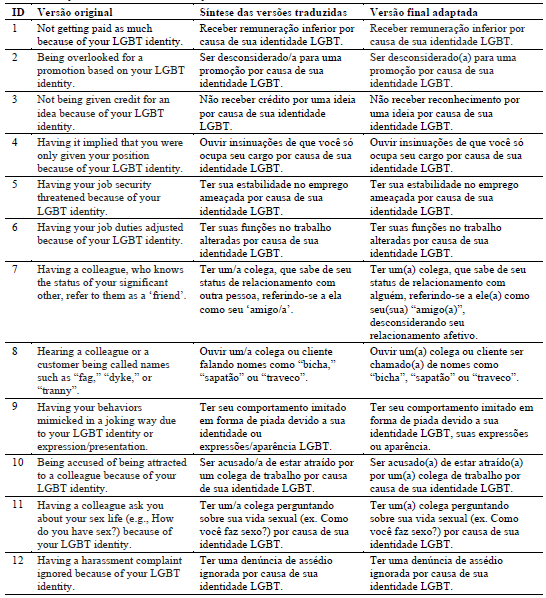

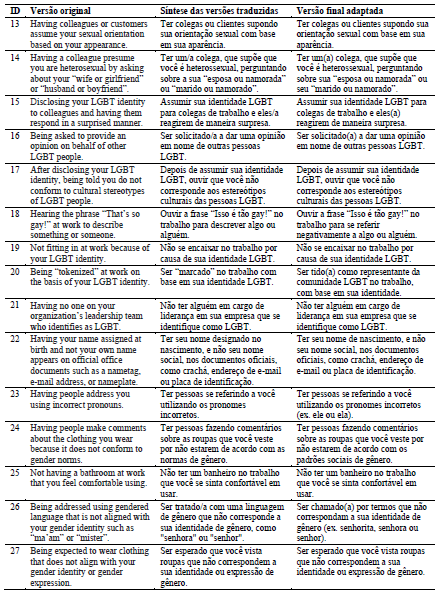

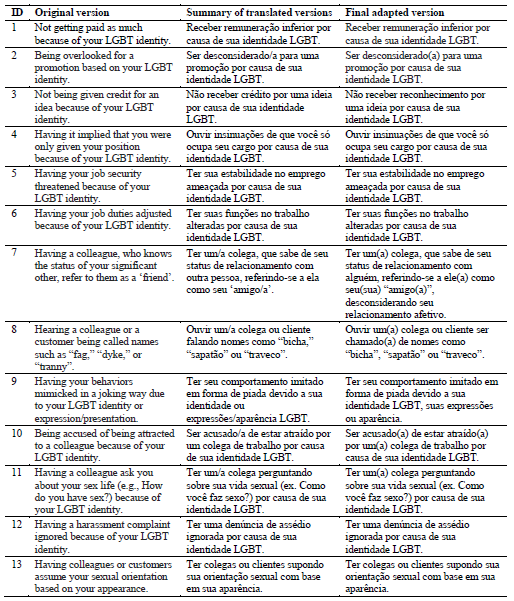

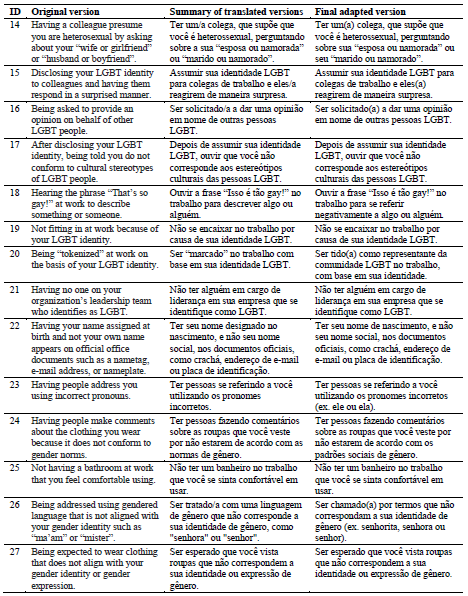

A versão original da EEM-LGBT consta na Tabela 1. Na tradução do inglês para o português, destaca-se que os(a) tradutores(a) apontaram necessidade de buscar uma tradução equivalente para o termo tokenized, no item 20 (Being “tokenized” at work on the basis of your LGBT identity), pois sua tradução direta seria tokenizado, uma palavra pouco usual no Brasil. Na síntese das versões traduzidas, optou-se pela adoção do rotulado para substituir tokenizado. Nos demais itens, houve a necessidade de acrescentar flexões de gêneros (ex. a/o) ou termos neutros (ex. alguém) na versão em português brasileiro, pois o idioma original do instrumento apresenta uma linguagem neutra (ex. a ou an).

Na análise de juízes experts, os resultados do IVC foram adequados: instruções (1), escala de resposta (1), dimensão valores no local de trabalho (0,98), dimensão suposições heteronormativas (0,94) e dimensão cultura cisnormativa (1). A avaliação qualitativa das sugestões dos juízes culminou em alterações na escala de resposta e nos itens 20 e 22. Na escala de resposta, houve uma alteração de às vezes para ocasionalmente, possibilitando o entendimento de uma intensidade moderada.

No item 20 (Ser ‘rotulado’ no trabalho com base em sua identidade LGBT), considerando o termo original tokenized, a sugestão dos juízes culminou na modificação para “Ser tido/a como representante da comunidade LGBT no trabalho, com base em sua identidade”. No item 22 (Ter seu nome designado no nascimento, e não seu nome social, nos documentos oficiais, como crachá, endereço de e-mail ou placa de identificação), foi retirado o termo designado no nascimento e substituído por nome de nascimento. As alterações foram realizadas e compiladas em uma única versão (Tabela 1).

Na avaliação pelo público-alvo, os itens 3, 7, 9, 18, 23, 24 e 26 foram alterados. No item 3 (Não receber crédito por uma ideia por causa de sua identidade LGBT), o termo crédito foi alterado para reconhecimento. No item 7 (Ter um/a colega, que sabe de seu status de relacionamento com outra pessoa, referindo-se a ela como seu ‘amigo/a’), o trecho “desconsiderando seu relacionamento afetivo” foi incluído, enfatizando que é uma forma de minimizar o relacionamento. No item 9 (Ter seu comportamento imitado em forma de piada devido a sua identidade ou expressões/aparência LGBT), o final foi alterado para “identidade LGBT, suas expressões ou aparência”, facilitando a compreensão. No item 18 (Ouvir a frase “Isso é tão gay!” no trabalho para descrever algo ou alguém), o trecho “para se referir negativamente a” foi incluído, enfatizando a visão negativa. No item 23 (Ter pessoas se referindo a você utilizando os pronomes incorretos), exemplos “(ex. ele ou ela)” foram adicionados ao final da frase, facilitando o entendimento. No item 24 (Ter pessoas fazendo comentários sobre as roupas que você veste por não estarem de acordo com as normas de gênero), o termo normas foi alterado para padrões sociais, destacando que trata de questões sociais. O item 26 (Ser tratado/a com uma linguagem de gênero que não corresponde a sua identidade de gênero, como “senhora” ou “senhor”) foi alterado para “Ser chamado(a) por termos que não correspondam a sua identidade de gênero (ex. senhorita, senhora ou senhor)”, utilizando linguagem mais clara e acrescentando mais um exemplo. Quanto às flexões de gênero dos itens 2, 7, 8, 10,11, 14, 16, 20 e 26, barras foram substituídas por parênteses, melhorando a compreensão. A versão do público-alvo, correspondente à versão final adaptada, consta na Tabela 1.

Tal versão foi submetida à tradução reversa e enviada para as autoras do instrumento original. Para elas, a versão estava adequada, mas houve uma alteração na escala de resposta (de sempre para muito frequentemente), já que seria menos provável de alguém assinalar o primeiro, por indicar que a situação aconteceria todas as vezes. Após esta alteração, a versão final foi aprovada pelas autoras.

Tabela 1: Descrição da síntese das traduções da EEM-LGBT

Nota: Distribuição dos itens por fator: valores no trabalho (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12), suposições heteronormativas (13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21) e cultura cisnormativa (22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27).

Parte 2: Investigação das Evidências de Validade de Estrutura Interna e Confiabilidade da EEM-LGBT para o contexto brasileiro

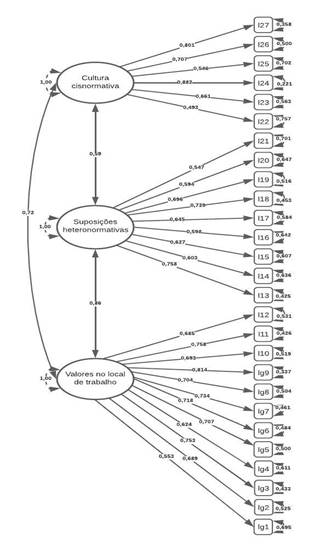

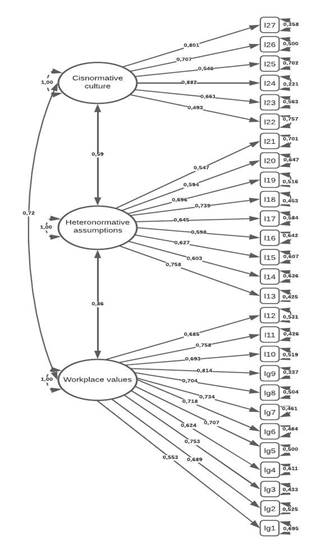

Considerando a estrutura original do EEM-LGBT, o modelo de primeira ordem com três dimensões independentes (valores do local de trabalho, suposições heteronormativas e cultura cisnormativa) foi testado neste estudo. Os resultados da AFC indicaram um excelente ajuste do modelo aos dados: χ2/gl = 1,22; CFI = 0,994; TLI = 0,993; SRMR = 0,076; RMSEA = 0,031 (IC 90%, 0,018 – 0,041), sugerindo sua plausibilidade. Os resultados da estrutura do modelo estão sumarizados na Figura 1.

Após a AFC, análises de confiabilidade foram executadas. Os resultados indicaram alfas de Cronbach adequados: valores do local de trabalho (0,92), suposições heteronormativas (0,86) e cultura cisnormativa (0,86). A confiabilidade composta também foi adequada: 0,92, 0,86 e 0,84, respectivamente.

Figura 1: Estrutura do modelo tridimensional da EEM-LGBT

Discussão

Esta pesquisa buscou adaptar e obter evidências de validade de estrutura interna da EEM-LGBT para o contexto brasileiro. A primeira parte da pesquisa, referente à adaptação para o contexto brasileiro, seguiu as seis etapas propostas por Borsa et al. (2012) e Bandeira e Hutz (2020). A escolha por este modelo de adaptação foi embasada no fato de, diferentemente de outros modelos, incluir importantes aspectos, como a avaliação itens do instrumento pelo público-alvo e o diálogo com autoras do instrumento original, verificando possíveis ajustes na versão final.

Na etapa de síntese, uma importante informação foi considerada: a necessidade de adição das flexões de gênero ou termos neutros. Na língua portuguesa, a flexão masculina era tradicionalmente tida como um termo neutro/genérico, mas é excludente especialmente em se tratando de pessoas LGBT (Covas & Bergamini, 2021). Assim, essa alteração buscou tornar o instrumento mais inclusivo.

Na análise de juízes, o IVC foi utilizado para calcular o nível de concordância, apresentando resultados satisfatórios. Este é o método o mais utilizado para investigar evidências de validade de conteúdo, pois possibilita analisar os índices de cada item e do instrumento como um todo (Alexandre & Coluci, 2011; Kovacic, 2019). A versão sintetizada neste estudo apresentou equivalência semântica, idiomática e conceitual em comparação à sua versão original, sofrendo poucas alterações, indicativo de qualidade.

A análise pelo público-alvo indicou alterações importantes, como acréscimo de exemplos, modificações de termos e adoção de parênteses nas flexões de gênero. Tais alterações estão em conformidade com a literatura que aponta a importância desta etapa para assegurar um instrumento acessível e compreensível ao público-alvo (Bandeira & Hutz, 2020; Borsa et al., 2012).

A versão foi traduzida para o idioma original e submetida a análise das autoras do instrumento, culminando na alteração da escala de resposta. Tal verificação se faz importante para indicar possíveis inconsistências e erros conceituais entre as versões. Vale destacar que esta etapa é pouco presente em outros modelos de adaptação de medidas, apesar da importância (Borsa et al., 2012).

A segunda parte da pesquisa, referente à investigação de evidências de validade baseadas na estrutura interna, visou garantir a aplicabilidade do instrumento no contexto brasileiro. A partir da adoção da AFC foi possível investigar se a teoria subjacente (modelo investigado) se ajustava aos dados obtidos no contexto brasileiro. Considerando o modelo de primeira ordem com três dimensões (valores no local de trabalho, suposições heteronormativas e cultura cisnormativa), os resultados indicaram um excelente ajuste aos dados, mostrando-se superior aos resultados preliminares obtidos no estudo original. Isto porque, no caso da presente pesquisa, todos os indicadores investigados apresentaram resultados adequados considerando os valores de referência adotados. Por sua vez, o estudo original apresentou CFI abaixo do indicado, apesar do RMSEA e SRMR dentro do esperado, o que indicaria sua utilização (Resnick & Galupo, 2019).

Acerca da confiabilidade da versão brasileira da EEM-LGBT, esta pesquisa adotou dois indicadores: alfa de Cronbach e confiabilidade composta. O alfa de Cronbach é o índice mais empregado para avaliar a confiabilidade de instrumentos (Valentini & Damásio, 2016), tendo sido empregado no estudo original da EEM-LGBT e apresentado valores dentro do indicado pela literatura. Os resultados encontrados na presente pesquisa mostraram-se adequados e equivalentes aos resultados do estudo original (Resnick & Galupo, 2019), indicativo da robustez do instrumento em diferentes populações.

Apesar da ampla utilização, a literatura tem contraindicado a adoção deste indicador, pois ele pressupõe que todos os itens apresentam a mesma importância para sua dimensão, o que poucas vezes ocorre. Diante disso, há forte tônica para a adoção da confiabilidade composta, um indicador mais robusto e que considera as cargas fatoriais como passíveis de variação (Valentini & Damásio, 2016). Os valores de confiabilidade composta apresentados neste estudo atenderam ao recomendado pela literatura, indicando sua precisão.

Os resultados encontrados evidenciaram que o processo de adaptação e busca de evidências de validade de estrutura interna da EEM-LGBT para o contexto brasileiro apresentou boa qualidade, alcançando os objetivos definidos neste trabalho e indicando sua adoção em outras pesquisas e o tornando o primeiro instrumento a investigar experiências de microagressões LGBT no contexto brasileiro. Sua utilização pode auxiliar as organizações a diagnosticar e gerir diversidade. Ademais, pode ser usada para fomentar pesquisas na área e auxiliar na maior compreensão do fenômeno e da vivência de profissionais LGBT no ambiente de trabalho, diante da lacuna de publicações no Brasil.

Entretanto, a coleta de dados online e nos formatos intencional e de bola de neve foram limitações do estudo. As pessoas respondentes foram compostas majoritariamente de profissionais brancos(a) e com níveis de escolaridade alta, divergindo da população geral brasileira. Ademais, cerca da metade dos participantes se autodeclarou homem cis gay. De acordo com a literatura, eles representam a maioria dos participantes das pesquisas com pessoas LGBT nas organizações (Silva et al., 2021). Essa participação desproporcional de profissionais da sigla LGBT pode repercutir nas políticas de diversidade nas organizações, tornando-as predominantemente voltadas a este recorte, em detrimento das demais orientações sexuais, identidades e expressões de gênero.

Houve também baixa participação de pessoas transgêneros e travestis, situação semelhante às pesquisas anteriores na área (Resnick & Galupo, 2019; Richard, 2021). O mercado de trabalho é particularmente mais difícil para esta parcela da população, que apresenta as maiores taxas de desemprego e tende a ser direcionada a trabalhos informais e autônomos (Costa et al., 2020), o que pode refletir em sua baixa participação nas pesquisas.

O tema de microagressões no Brasil ainda é um assunto pouco explorado, mas de suma relevância para as empresas e profissionais LGBT. Diante das boas qualidades psicométricas da EEM-LGBT no contexto brasileiro e do caráter pioneiro para investigar o construto no país, é importante que sejam realizadas pesquisas com vistas a buscar mais evidências de validade baseadas na estrutura interna, por meio de análises de invariância da medida, bem como buscar evidências de validade com variáveis externas, como estresse no trabalho, depressão, ansiedade, satisfação no trabalho, incivilidade, outness, autoestima, bem-estar, engajamento no trabalho, intenção de rotatividade, produtividade e suporte organizacional, além de considerar amostras mais amplas e homogêneas.

Referencias:

Alexandre, N. M. C., & Coluci, M. Z. O. (2011). Validade de conteúdo nos processos de construção e adaptação de instrumentos de medidas. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 16(7), 3061-3068. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232011000800006

Bandeira, D. R., & Hutz, C. S. (2020). Elaboração ou adaptação de instrumentos de avaliação psicológica para o contexto organizacional e do trabalho: Cuidados psicométricos. Em C. S. Hutz, D. R. Bandeira, C. M. Trentini, & A. C. S. Vazquez (Orgs.), Avaliação psicológica no contexto organizacional e do trabalho (pp. 13-18). Artmed.

Borsa, J. C., Damásio, B. F., & Bandeira, D. R. (2012). Adaptação e validação de instrumentos psicológicos entre culturas: Algumas considerações. Paidéia, 22(53), 423-432. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-43272253201314

Brown, T. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford.

Costa, A. B., Brum, G. M., Zoltowski, A. P. C., Dutra-Thomé, L., Lobato, M. I. R., Nardi, H. C., & Koller, S. H. (2020). Experiences of discrimination and inclusion of Brazilian transgender people in the labor market. Revista Psicologia: Organização & Trabalho, 20(2), 1040-1046. https://doi.org/10.17652/rpot/2020.2.18204

Covas, F. S. N., & Bergamini, L. M. (2021). Análise crítica da linguagem neutra como instrumento de reconhecimento de direitos das pessoas LGBTQIA+. Brazilian Journal of Development, 7(6), 54892-54913. https://doi.org/10.34117/bjdv7n6-067

Kovacic, D. (2019). Using the content validity index to determine content validity of an instrument assessing health care providers’ general knowledge of human trafficking. Journal of Human Trafficking, 4(4), 327-335. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2017.1364905

Li, C. H. (2016). Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behavior Research Methods, 48(3), 936-949. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-015-0619-7

Medina, A. (2022). The impact workplace microaggressions have on those who identify as lesbian, gay and bisexual (Dissertação de doutorado). National Louis University. https://digitalcommons.nl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1764&context=diss

Mendes, W. G., & Silva, C. M. F. P. (2020). Homicídios da população de lésbicas, gays, bissexuais, travestis, transexuais ou transgêneros (LGBT) no Brasil: Uma análise espacial. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 25(5), 1709-1722. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232020255.33672019

Nadal, K. L. (2019). A decade of microaggression research and LGBTQ communities: An introduction to the special issue. Journal of Homosexuality, 66(10), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1539582

Nadal, K. L., Wong, Y., Issa, M., Meterko, V., Leon, J., & Wideman, M. (2011). Sexual orientation microaggressions: Processes and coping mechanisms for lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 5(1), 21-46. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2011.554606

Palo, S., & Jha, K. K. (2020). Queer at work. Palgrave Macmillan.

Papadaki, V., Papadaki, E., & Giannou, D. (2021). Microaggression experiences in the workplace among Greek LGB social workers. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 33(4), 512-532. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2021.1892560

Parr, N. J., & Howe, B. G. (2019). Heterogeneity of transgender identity nonaffirmation microaggressions and their association with depression symptoms and suicidality among transgender persons. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 6(4), 461-474. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000347

Redcay, A., Luquet, W., & Huggin, M.E. (2019). Immigration and asylum for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals. Journal of Human Rights and Social Work, 4, 248-256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41134-019-00092-2

Resnick, C. A., & Galupo, M. P. (2019). Assessing experiences with LGBT microaggressions in the workplace: Development and validation of the microaggression experiences at work scale. Journal of Homosexuality, 66(10), 1380-1403. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1542207

Richard, D. (2021). Workplace microaggressions experienced by sexual minorities: Relationships to workplace attitudes, mental health, and the role of emotional distress tolerance (Dissertação de doutorado). University of Southern Mississippi. https://aquila.usm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2929&context=dissertations

Salgado, A. G. A. T., Araújo, L. F., Santos, J. V. O., Jesus, L. A., Fonseca, L. K. S., & Sampaio, D. S. (2017). LGBT old age: An analysis of the social representations among Brazilian elderly people. Ciencias Psicológicas, 11(2), 155-163. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v11i2.1487

Silva, D. W. G., Castro, G. H. C., & Siqueira, M. V. S. (2021). Ativismo LGBT organizacional: Debate e agenda de pesquisa. Revista Eletrônica de Ciência Administrativa, 20(3), 434-462. https://doi.org/10.21529/RECADM.2021015

Sooknanan, V. (2023). An investigation of LGBTQ+-specific workplace microaggressions: Their impact on job engagement and the buffering effects of organizational trust and identity disclosure (Dissertação de mestrado). Western University. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/9409/

Souza, E. R., Ispas, D., & Weselman, E. D. (2017). Workplace discrimination against sexual minorities: Subtle and not-so-subtle. Canadian Jornal of Administrative Sciences, 34(2), 121-132. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjas.1438

Supremo Tribunal Federal. (2019). STF enquadra homofobia e transfobia como crimes de racismo ao reconhecer omissão legislativa. Jusbrasil. https://stf.jusbrasil.com.br/noticias/721650294/stf-enquadra-homofobia-e-transfobia-como-crimes-de-racismo-ao-reconhecer-omissao-legislativa

Valentini, F., & Damásio, B. F. (2016). Variância média extraída e confiabilidade composta: Indicadores de precisão. Psicologia: Teoria e Pesquisa, 32(2). https://doi.org/10.1590/0102-3772e322225

Zanin, H. S. (2019). Fomento à economia pelas políticas públicas e o respeito aos direitos fundamentais: Acesso ao trabalho pelas minorias sexuais e de gênero. Revista Contribuciones a la Economía, 2019(2), 1-9.

Disponibilidade de dados: O conjunto de dados que embasa os resultados deste estudo não está disponível.

Como citar: de Sousa Zarife, P., & Ribeiro, C. (2023). Adaptação e evidências de validade da Escala de Experiências de Microagressões LGBT no Trabalho para o Brasil. Ciencias Psicológicas, 17(2), e-3053. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i2.3053

Participação dos autores: a) Planejamento e concepção do trabalho; b) Coleta de dados; c) Análise e interpretação de dados; d) Redação do manuscrito; e) Revisão crítica do manuscrito.

P. S. Z. contribuiu em a, b, c, d, e; C. R. em a, b, c, d.

Editora científica responsável: Dra. Cecilia Cracco.

10.22235/cp.v17i2.3053

Original Articles

Adaptation and validity evidence of LGBT Microaggression Experiences at Work Scale in Brazil

Adaptação e evidências de validade da Escala de Experiências de Microagressões LGBT no Trabalho para o Brasil

Adaptación y evidencias de validez de la Escala de Experiencias de Microagresiones LGBT en el Trabajo para Brasil

Pricila de Sousa Zarife1, ORCID 0000-0002-0187-0425

Catarina Ribeiro2, ORCID 0000-0001-9682-9339

1 Universidade Federal de Uberlândia, Brazil, [email protected]

2 Santo Caos Consultoria em Publicidade, Brazil

Abstract:

This research aimed to adapt and obtain validity evidence of the internal structure of the LGBT Microaggression Experiences at Work Scale (LGBT-MEWS) for the Brazilian context. The sample consisted of 226 professionals who identified themselves as LGBT, with a mean age of 28.5 years (SD = 7.19) who answered the LGBT-MEWS and a sociodemographic questionnaire. The LGBT-MEWS adaptation process followed the stages of translation, synthesis, evaluation by expert judges, evaluation by the target population, and back translation. Confirmatory factor analysis was performed to assess the plausibility of the three-dimensional structure (workplace values, heteronormative assumptions, and cisnormative culture). The Brazilian version presented adequate CVI, according to expert judges. The proposed three-dimensional structure presented an excellent fit to the data (χ2/df = 1.22; CFI = .994; TLI = .993; SRMR = .076; RMSEA = .031), and good reliability indices (Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability ≥ .84). The adapted version of the LGBT-MEWS presented satisfactory quality, making it the first instrument in the Brazilian context to investigate experiences of LGBT microaggressions at work.

Keywords: discrimination at work; microaggressions; diversity in organizations; sexual and gender minorities; validity.

Resumo:

Esta pesquisa buscou adaptar e obter evidências de validade de estrutura interna da Escala de Experiências de Microagressões LGBT no Trabalho (EEM-LGBT) para o contexto brasileiro. Participaram 226 profissionais que se identificaram como LGBT, com idade média de 28,5 anos (DP = 7,19) que responderam à EEM-LGBT e um questionário sociodemográfico. O processo de adaptação da EEM-LGBT seguiu as etapas de tradução, síntese, avaliação por experts, avaliação pelo público-alvo e tradução reversa. Para avaliar a plausibilidade da estrutura tridimensional (valores no local de trabalho, suposições heteronormativas e cultura cisnormativa) foi realizada análise fatorial confirmatória. A versão em português apresentou IVC adequado, segundo juízes experts. A estrutura tridimensional proposta apresentou um ótimo ajuste aos dados (χ2/gl = 1,22; CFI = 0,994; TLI = 0,993; SRMR = 0,076; RMSEA = 0,031) e bons índices de confiabilidade (alfa de Cronbach e confiabilidade composta ≥ 0,84). A versão adaptada da EEM-LGBT apresentou qualidade satisfatória, tornando-se o primeiro instrumento no contexto brasileiro destinado a investigar experiências de microagressões LGBT no trabalho.

Palavras-chave: discriminação no trabalho; microagressões; diversidade nas organizações; minorias sexuais e de gênero; validade.

Resumen:

Esta investigación buscó adaptar y obtener evidencias de validez de la estructura interna de la Escala de Experiencias de Microagresiones LGBT en el Trabajo (EEM-LGBT) para el contexto brasileño. Participaron 226 profesionales que se identificaron como LGBT, con una edad media de 28.5 años (DE = 7.19), que respondieron el EEM-LGBT y un cuestionario sociodemográfico. El proceso de adaptación de EEM-LGBT siguió las etapas de traducción, síntesis, evaluación de expertos, evaluación de la audiencia objetivo y retrotraducción. Para evaluar la plausibilidad de la estructura tridimensional, se realizó un análisis factorial confirmatorio. La versión portuguesa presentó CVI adecuado, según los jueces expertos. La estructura tridimensional propuesta presentó un excelente ajuste a los datos (χ2/gl = 1.22; CFI = .994; TLI = .993; SRMR = .076; RMSEA = .031) y buenos índices de confiabilidad (alfa de Cronbach y confiabilidad compuesta ≥ .84). La versión adaptada del EEM-LGBT fue de calidad satisfactoria, lo que lo convierte en el primer instrumento en el contexto brasileño para investigar experiencias de microagresiones LGBT en el trabajo.

Palabras clave: discriminación en el trabajo; microagresiones; diversidad en las organizaciones; minorías sexuales y de género; validez.

Received: 20/09/2022

Accepted: 26/10/2023

In many parts of the world, identifying as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or transvestite (LGBT) can result in a loss of rights, violence, and even the risk of death (Redcay et al., 2019). Such intolerance can occur in different spheres, such as organizations, family, religious, educational, and health institutions (Salgado et al., 2017). In Brazil, the country with the highest rate of lethal crimes against LGBT people (Mendes & Silva, 2020), the Federal Supreme Court (2019) established homophobia and transphobia as crimes equivalent to acts of racism.

Even in contexts with protective legislation, LGBT people continue to be stigmatized, especially in countries with conservative cultures (Redcay et al., 2019). In addition, violence considered to be silent or subtle has become increasingly frequent, as it is not reported or considered under the terms of the law (Souza et al., 2017). Among subtle violence are microaggressions, defined as verbal, behavioral, or environmental abjections that convey contempt and insults and are directed at minority groups, such as LGBT people (Resnick & Galupo, 2019). Even if subtle and brief, they negatively impact their victims, causing low self-esteem, depression, trauma (Nadal, 2019), sadness, withdrawal from regular activities, and suicidal ideation or attempts (Parr & Howe, 2019).

Subtle discrimination against LGBT people at work is usually less noticeable than acts of physical or sexual violence (Souza et al., 2017). However, they can have an impact on their entry and permanence in the job market, combined with the neglect of basic rights and social vulnerability. Transgender people face even more difficulties, such as high rates of unemployment, underemployment, and job dissatisfaction, as well as being directed to informal jobs, self-employment, and prostitution (Costa et al., 2020).

In the face of microaggressions suffered at work, LGBT people often employ different coping strategies, such as remaining passive in the face of aggression (not reacting and ignoring negative comments, even though they are negatively affected), confronting the aggressor (reacting actively and challenging them) or emitting self-protective behaviors (acting cautiously to ensure their physical safety, such as keeping an eye on their surroundings) (Nadal et al., 2011; Papadaki et al., 2021). Regarding possible cognitive reactions to such events, they tend to accept that such aggression is part of life as an LGB person, seek to empower themselves to respond to aggressors, or come out about their sexual orientation, if they have not already done so (Papadaki et al., 2021).

The literature dealing with discrimination against LGBT people at work and its impact is still relatively incipient (Richard, 2021), even more so when it comes to measuring instruments aimed at explicitly investigating microaggressions directed at this section of the population. The few quantitative studies tend to make changes to the wording of measures that investigate racial discrimination, so that they can be applied to LGBT people (Medina, 2022). Considering that it is of the utmost importance to investigate the occurrence and impact of such experiences on LGBT people, measuring instruments specifically designed for them can be an important research strategy.

The LGBT Microaggression Experiences at Work Scale (LGBT-MEWS, Escala de Experiências de Microagressões LGBT no Trabalho/EEM-LGBT) is a measurement instrument developed in the United States to investigate this type of discrimination. Different strategies were adopted in its development: literature review, reports of LGBT people who have suffered microaggressions in the workplace and analysis of instruments that investigated heterosexist experiences, involving both inductive and deductive strategies (Resnick & Galupo, 2019).

Initially, 64 items were developed and subjected to investigation of validity evidence based on content and internal structure, by means of exploratory factor analysis (EFA) and confirmatory factor analysis (CFA). The final version consists of 27 items distributed in three dimensions with the following fit indices χ2 (321) = 1226.30; p < .001, CFI = .76; SRMR = .08; RMSEA = .09; 90 % (.091, .102) and reliability (Cronbach's alpha) between .82 and .93. Although the CFI (Comparative Fit Index) was lower than recommended, with the SRMR (Standardized Root Mean Square Residuals), RMSEA (Root Mean Square Error of Approximation) and confidence interval below .10, the inadequacy test was rejected, indicating the use of the instrument (Resnick & Galupo, 2019).

The three-dimensional model derived from the construction of the measure is composed of (1) workplace values, (2) heteronormative assumptions, and (3) cisnormative culture. The workplace values dimension is related to the general value system of an organization, involving LGBT workers' interpersonal interactions with their colleagues (such as derogatory jokes and insults), as well as their status at work related to hiring, promotion, pay scale, and job security (Resnick & Galupo, 2019). The heteronormative assumptions dimension describes everyday heterosexism at work that invalidates the experience and identity of LGBT professionals, such as the assumption that the person is heterosexual and statements to marginalize, invalidate or discredit their experiences as an LGBT person (Resnick & Galupo, 2019). It is worth noting that, traditionally, some organizations may have a more heteronormative culture than other social spaces, especially when they are predominantly made up of cis heterosexual men (Palo & Jha, 2020). The cisnormative culture dimension is related to disrespect for a person's gender identity and/or expression and how it is experienced at work, reinforcing that people identify with the sex assigned at birth, disregarding the multiplicity of gender identities and expressions. This involves the absence of inclusive policies relating to the use of toilets, neutral language, and dress code. For the model, this separation between dimensions is of paramount importance to reinforce that there are differences in the microaggressions suffered by transgender people (Resnick & Galupo, 2019).

A quantitative survey of 325 American LGBT professionals using the LGBT-MEWS found that microaggressions positively predicted stress at work (b = .23; p < .001), symptoms of stress (b = .05; p < .001), depression (b = .05; p < .001) and anxiety (b = .06; p < .001), symptoms of stress (b = .05; p < .001), depression (b = .05; p < .001) and anxiety (b = .06; p < .001), as well as negatively predicting job satisfaction (b = -.17; p < .01). The results also showed that even people who do not openly identify as LGBT can also suffer discrimination (Richard, 2021).

Another quantitative study with 88 cisgender and LGB American professionals, which adopted the LGBT-MEWS, identified the variables concerns about acceptance (b = .24; p = .034) and motivation to hide sexual orientation (β = .49; p < .001) as predictors of microaggressions (F(2, 85) = 9.97; p < .001; R2 = .19). Furthermore, microaggressions did not significantly predict satisfaction with the romantic relationship (Medina, 2022). Finally, another quantitative survey, conducted with 314 LGBT professionals living in Canada (66 %) and the United States (34 %) and adopting the LGBT-MEWS, identified a high correlation between incivility (rude and disrespectful behavior) and microaggressions (r = .64; p < .001). The results indicated that the relationship between microaggressions and work engagement (b = -.10; p < .05) was considered significant only when combined with outness (the degree to which a person reveals their sexual orientation and/or gender identity) as a potential moderating variable (Sooknanan, 2023).

Although LGBT people are one of the most marginalized groups in Brazilian organizations, there is a lack of research on their experiences in the workplace (Zanin, 2019). As for microaggressions against LGBT people at work, there is no measuring instrument to investigate their occurrence in Brazil, making it difficult to identify their occurrence, their impacts, and the development of strategies to prevent them. Given these gaps, with the aim of fostering new studies and helping organizations manage diversity, this research sought to adapt and obtain validity evidence of the internal structure of the LGBT-MEWS for the Brazilian context.

The choice to adapt an international instrument was based on the advantages of this procedure compared to developing a new measure. These include the possibility of comparing data collected with the same measure in samples from different contexts and populations, making the assessment more equivalent, and greater ability to generalize the results (Borsa et al., 2012).

Method

This section is divided into two parts. The first corresponds to the process of translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the instrument for the Brazilian context. The second corresponds to the process of finding validity evidence of the internal structure.

Part 1: Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the scale

The authors of the original version of the LGBT-MEWS were consulted and authorized the research. The adaptation followed the following steps: translation of the instrument into the new language, synthesis of the translated versions, evaluation by experts judges, evaluation by the target population, and back translation (Bandeira & Hutz, 2020; Borsa et al., 2012).

The instrument was translated from English into Brazilian Portuguese by three people who were native speakers of Portuguese and fluent in English, studying Psychology and belonging to the research's target population (two cisgender gay men and one cisgender lesbian woman), who were intentionally selected by the research team based on the aforementioned characteristics, and contacted by e-mail. The team then analyzed the three translated versions to obtain a single version, evaluating the semantic, linguistic, contextual, and conceptual discrepancies.

A committee of expert judges individually evaluated the equivalence between the translated version and the original instrument in terms of semantic, idiomatic, experimental, and conceptual equivalence. The committee was made up of four researchers in the field of Psychology (three professors with a doctorate and one with a master's degree), experienced in the construction and adaptation of instruments, two of whom were part of the target population of the research, whose selection was also intentional, and contact was made by e-mail. The notes were analyzed by the research team, considering the conceptual equivalence with the original version and the proportion of agreement between the judges, calculated by the Content Validity Index (CVI). The interpretation considered a CVI above .80 to be desirable (Alexandre & Coluci, 2011).

Next, four people from the target population evaluated their understanding of the version from the previous stage: a cisgender gay man with a postgraduate degree in Marketing, a cisgender bisexual man with a degree in Mechanical Engineering, a cisgender lesbian woman with a degree in Veterinary Medicine and a heterosexual transgender woman with completed high school, who were sampled by snowball and contacted by e-mail. They were interviewed individually, reading aloud each topic of the instrument and explaining their understanding of it. When they reported problems understanding, they were asked to suggest synonyms and semantic changes. In the end, the suggestions were evaluated by the research team based on clarity, equivalence to the original version, and frequency of suggested changes.

Finally, the instrument was translated from Portuguese into English by a professional translator who is a native speaker of Brazilian Portuguese and has a degree in Psychology. The back-translated version was analyzed by the research team and sent to the authors of the original instrument to identify inconsistencies and conceptual errors between the versions.

Part 2: Investigation of the validity evidence of the internal structure and reliability of the EEM-LGBT for the Brazilian context

Participants

The sample consisted of 226 LGBT professionals, aged between 18 and 56 (M = 28.50; SD = 7.13), 57.40 % of whom were male (n = 128), 38.56 % female (n = 86) and 4.04 % non-binary (n = 9). Transgender or transvestite people made up 11.95 % (n = 27) of the sample, 6.64 % (n = 15) of whom said they had a social name.

The participants identified themselves as gay (51.35 %; n = 114), bisexual (22.98 %; n = 51), lesbian (20.72 %; n = 46), heterosexual (transgender) (3.15 %; n = 7), asexual (1.35 %; n = 3), and pansexual (.45 %; n = 1). The majority declared themselves to be white (61.50 %; n = 139), followed by brown (25.22 %; n = 57), black (10.62 %; n = 24), yellow (2.22 %; n = 5) and indigenous (.44 %; n = 1). The majority lived in the southeast (80.97 %; n = 183), followed by the south (7.08 %; n = 16), northeast (5.31 %; n = 12), midwest (4.43 %; n = 10) and north (2.21 %; n = 5), predominantly in inland cities (53.78 %; n = 121).

The majority were single (69.91 %; n = 158), living with a partner, married or in a stable union (28.32 %; n = 64), and separated or divorced or widowed (1.77 %; n = 4). There was a predominance of people with complete higher education (30.63 %; n = 68), followed by incomplete higher education (27.03 %; n = 60), complete postgraduate degrees (23.87 %; n = 53), incomplete postgraduate degrees (11.26 %; n = 25), complete secondary education (5.86 %; n = 13), incomplete secondary education (.90 %; n = 2), and incomplete primary education (.45 %; n = 1). As for the length of time they had worked for the company, they had been working for between 4 months and 32 years (M = 3.16; SD = 4.99).

Instrument

Escala de Experiências de Microagressões LGBT no Trabalho (EEM-LGBT, LGBT Microaggression Experiences at Work Scale/LGBT-MEWS; Resnick & Galupo, 2019). The instrument consists of 27 items, divided into three dimensions: workplace values (12 items), heteronormative assumptions (9 items), and cisnormative culture (6 items). The answers were marked on a Likert scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very often).

Socio-demographic data questionnaire. Questions about age, region of the country, city, skin color, marital status, schooling, length of time in the company, gender identity, social name, and sexual orientation.

Ethical and data collection procedures

The research was carried out in compliance with the requirements of Resolution 510/2016 of the National Health Council (CNS), which deals with research involving human beings. Data collection began after approval by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Uberlândia (CAEE: 39232120.2.0000.5152).

The inclusion criteria involved identifying as an LGBT person, being of legal age, and having at least three months of professional experience. People without access to the internet and who declared themselves illiterate or with some impairment that prevented them from understanding the instrument were not included.

The instrument was made available online via a virtual link (Google Forms) which gave access to an online form containing the Informed Consent Form (ICF), with the general objective of the research, confidentiality of data and conditions for participation, and the survey questionnaire. The link was shared on social media (Facebook, Instagram, and LinkedIn) and sent to groups and non-governmental organizations (NGOs) aimed at LGBT people, using the snowball method. Data collection took place between June and August 2021.

On opening the link, the participant had access to the online version of the ICF. After reading the document, they had to sign the mandatory "I have read, understood, and am interested in participating in the research" option in order to access the questionnaire. If they did not agree to take part, they would receive a thank you message, ending their participation.

Data analysis procedures

The data collected was tabulated and analyzed using JASP software, version 0.16. Confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) was performed to evaluate the plausibility of the three-dimensional structure. The Robust Diagonally Weighted Least Squares (RDWLS) estimation method was adopted due to its suitability for categorical data (Li, 2016).

The fit indices and their reference values investigated were: c2 (not significant);c2/df < 3; Comparative Fit Index (CFI > .95); Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI > .95); Standardized Root Mean Residual (SRMR < .08) and Root Mean Square Error of Approximation (RMSEA < .06, with confidence interval (upper limit) < .10) (Brown, 2015). The reliability of the measure was investigated by Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability, with values above .70 being acceptable (Valentini & Damásio, 2016).

Results

Part 1: Translation and cross-cultural adaptation of the scale

The original version of the LGBT-MEWS is shown in Table 1. In the translation from English to Portuguese, it should be noted that the translators pointed out the need to find an equivalent translation for the term tokenized in item 20 (Being “tokenized” at work on the basis of your LGBT identity), as its direct translation would be "tokenizado", an unusual word in Brazil. In the synthesis of the translated versions, we opted to use labeled to replace tokenized. In the other items, it was necessary to add gender inflections (e.g. a/o) or neutral terms (e.g. someone) in the Brazilian Portuguese version, as the original language of the instrument has a neutral language (e.g. a or an).

In the expert judges' analysis, the CVI results were adequate: instructions (1), response scale (1), workplace values dimension (.98), heteronormative assumptions dimension (.94), and cisnormative culture dimension (1). The qualitative evaluation of the judges' suggestions resulted in changes to the response scale and items 20 and 22. On the response scale, there was a change from sometimes to occasionally, making it possible to understand a moderate intensity.

In item 20 (Being “tokenized” at work on the basis of your LGBT identity), considering the original term tokenized, the judges' suggestion culminated in the modification to “Being seen as a representative of the LGBT community at work, on the basis of your identity”. In item 22 (Having your name assigned at birth, and not your social name, on official documents such as a badge, e-mail address, or nameplate), the term assigned at birth was removed and replaced with birth name. The changes were made and compiled into a single version (Table 1).

In the evaluation by the target population, items 3, 7, 9, 18, 23, 24, and 26 were changed. In item 3 (Not receiving credit for an idea because of your LGBT identity), the term credit has been changed to recognition. In item 7 (Having a colleague, who knows about your relationship status with another person, refer to them as your 'friend'), the phrase “disregarding your emotional relationship” has been included, emphasizing that it is a way of minimizing the relationship. In item 9 (Having your behavior imitated as a joke due to your LGBT identity or expressions/appearance), the ending has been changed to “LGBT identity, its expressions or appearance”, making it easier to understand. In item 18 (Hearing the phrase “That's so gay!” at work to describe something or someone), the phrase "to refer negatively to" has been included, emphasizing the negative view. In item 23 (Having people refer to you using the incorrect pronouns), examples “(e.g. he or she)” have been added to the end of the sentence, making it easier to understand. In item 24 (Having people make comments about the clothes you wear because they don't conform to gender norms), the term norms has been changed to social standards, highlighting that it deals with social issues. Item 26 (Being addressed with gendered language that doesn't correspond to your gender identity, such as “ma'am” or “sir”) has been changed to “Being called by terms that don't correspond to your gender identity (e.g. miss, ma'am or sir)”, using clearer language and adding another example. As for the gender inflections in items 2, 7, 8, 10, 11, 14, 16, 20, and 26, bars have been replaced by brackets, improving comprehension. The target population version, corresponding to the final adapted version, is shown in Table 1.

This version was back-translated and sent to the authors of the original instrument. For them, the version was adequate, but there was a change in the response scale (from always to very often), since it would be less likely for someone to tick the first one, as it would indicate that the situation would happen every time. After this change, the final version was approved by the authors.

Table 1: Description of the summary of the EEM-LGBT translations

Note: Distribution of items by factor: values at work (1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12), heteronormative assumptions (13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21) and cisnormative culture (22, 23, 24, 25, 26, 27).

Part 2: Investigation of the Validity Evidence of the Internal Structure and Reliability of the EEM-LGBT for the Brazilian context

Considering the original structure of the EEM-LGBT, the first-order model with three independent dimensions (workplace values, heteronormative assumptions and cisnormative culture) was tested in this study. The results of the CFA indicated an excellent fit of the model to the data: χ2 /df = 1.22; CFI = .994; TLI = .993; SRMR = .076; RMSEA = .031 (90% CI, .018 - .041), suggesting its plausibility. The results of the model structure are summarized in Figure 1.

After the CFA, reliability analyses were carried out. The results indicated adequate Cronbach's alphas: workplace values (.92), heteronormative assumptions (.86), and cisnormative culture (.86). The composite reliability was also adequate: .92, .86, and .84, respectively.

Figure 1: Structure of the EEM-LGBT three-dimensional model

Discussion

This research sought to adapt and obtain validity evidence of the internal structure of the EEM-LGBT for the Brazilian context. The first part of the research, referring to adaptation to the Brazilian context, followed the six stages proposed by Borsa et al. (2012) and Bandeira and Hutz (2020). The choice of this adaptation model was because, unlike other models, it included important aspects, such as the evaluation of the instrument's items by the target population and dialog with the authors of the original instrument, verifying possible adjustments to the final version.

In the synthesis stage, an important piece of information was considered: the need to add gender inflections or neutral terms. In the Portuguese language, masculine inflection was traditionally considered a neutral/generic term, but it is exclusionary, especially when it comes to LGBT people (Covas & Bergamini, 2021). Thus, this change sought to make the instrument more inclusive.

In the judges' analysis, the CVI was used to calculate the level of agreement, with satisfactory results. This is the method most commonly used to investigate evidence of content validity, as it makes it possible to analyze the indices of each item and the instrument as a whole (Alexandre & Coluci, 2011; Kovacic, 2019). The version synthesized in this study showed semantic, idiomatic, and conceptual equivalence compared to its original version, with few changes, indicative of quality.

The analysis by the target population indicated important changes, such as the addition of examples, modifications to terms, and the adoption of parentheses in gender inflections. These changes are in line with the literature, which points out the importance of this stage to ensure that the instrument is accessible and understandable to the target population (Bandeira & Hutz, 2020; Borsa et al., 2012).

The version was translated into the original language and submitted for analysis by the authors of the instrument, culminating in a change to the response scale. This check is important to indicate possible inconsistencies and conceptual errors between the versions. It is worth noting that this stage is rarely present in other models for adapting measures, despite its importance (Borsa et al., 2012).

The second part of the research, relating to the investigation of validity evidence based on the internal structure, aimed to guarantee the applicability of the instrument in the Brazilian context. By adopting CFA, it was possible to investigate whether the underlying theory (model investigated) fitted the data obtained in the Brazilian context. Considering the first-order model with three dimensions (workplace values, heteronormative assumptions, and cisnormative culture), the results indicated an excellent fit to the data, proving superior to the preliminary results obtained in the original study. This is because, in the case of this study, all the indicators investigated showed adequate results considering the reference values adopted. On the other hand, the original study presented a CFI below that indicated, despite the RMSEA and SRMR being within the expected range, which would indicate its use (Resnick & Galupo, 2019).

Regarding the reliability of the Brazilian version of the EEM-LGBT, this research adopted two indicators: Cronbach's alpha and composite reliability. Cronbach's alpha is the index most commonly used to assess the reliability of instruments (Valentini & Damásio, 2016), and it was used in the original study of the EEM-LGBT and showed values within the range indicated by the literature. The results found in this study were adequate and equivalent to the results of the original study (Resnick & Galupo, 2019), indicating the robustness of the instrument in different populations.

Despite its widespread use, the literature has argued against the adoption of this indicator, as it assumes that all items have the same importance for their dimension, which is rarely the case. In view of this, there is a strong emphasis on the adoption of composite reliability, a more robust indicator that considers factor loadings as subject to variation (Valentini & Damásio, 2016). The composite reliability values presented in this study met those recommended in the literature, indicating their accuracy.

The results showed that the process of adapting and finding validity evidence of the internal structure of the EEM-LGBT for the Brazilian context was of good quality, achieving the objectives defined in this work and indicating its adoption in other research and making it the first instrument to investigate LGBT microaggression experiences in the Brazilian context. Its use can help organizations diagnose and manage diversity. In addition, it can be used to encourage research in the area and help provide a better understanding of the phenomenon and the experience of LGBT professionals in the workplace, given the lack of publications in Brazil.

However, the study's limitations were the collection of data online and in intentional and snowball formats. The majority of respondents were white professionals with high levels of education, diverging from the general Brazilian population. In addition, around half of the participants declared themselves to be cisgender gay men. According to the literature, they represent the majority of participants in surveys with LGBT people in organizations (Silva et al., 2021). This disproportionate participation of LGBT professionals can have repercussions on diversity policies in organizations, making them predominantly focused on this group, to the detriment of other sexual orientations, identities, and gender expressions.

There was also low participation from transgender people and transvestites, a situation similar to previous research in the area (Resnick & Galupo, 2019; Richard, 2021). The job market is particularly difficult for this section of the population, which has the highest unemployment rates and tends to be directed towards informal and self-employed work (Costa et al., 2020), which may reflect in their low participation in surveys.

The topic of microaggressions in Brazil is still little explored, but it is extremely relevant for LGBT companies and professionals. Given the good psychometric qualities of the EEM-LGBT in the Brazilian context and the pioneering nature of investigating the construct in the country, it is important that research is carried out to seek further validity evidence based on the internal structure, through analyses of measurement invariance, as well as seeking validity evidence with external variables, such as work stress, depression, anxiety, job satisfaction, incivility, outness, self-esteem, well-being, work engagement, turnover intention, productivity and organizational support, in addition to considering larger and more homogeneous samples.

References:

Alexandre, N. M. C., & Coluci, M. Z. O. (2011). Validade de conteúdo nos processos de construção e adaptação de instrumentos de medidas. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 16(7), 3061-3068. https://doi.org/10.1590/S1413-81232011000800006

Bandeira, D. R., & Hutz, C. S. (2020). Elaboração ou adaptação de instrumentos de avaliação psicológica para o contexto organizacional e do trabalho: Cuidados psicométricos. In C. S. Hutz, D. R. Bandeira, C. M. Trentini, & A. C. S. Vazquez (Orgs.), Avaliação psicológica no contexto organizacional e do trabalho (pp. 13-18). Artmed.

Borsa, J. C., Damásio, B. F., & Bandeira, D. R. (2012). Adaptação e validação de instrumentos psicológicos entre culturas: Algumas considerações. Paidéia, 22(53), 423-432. https://doi.org/10.1590/1982-43272253201314

Brown, T. (2015). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford.

Costa, A. B., Brum, G. M., Zoltowski, A. P. C., Dutra-Thomé, L., Lobato, M. I. R., Nardi, H. C., & Koller, S. H. (2020). Experiences of discrimination and inclusion of Brazilian transgender people in the labor market. Revista Psicologia: Organização & Trabalho, 20(2), 1040-1046. https://doi.org/10.17652/rpot/2020.2.18204

Covas, F. S. N., & Bergamini, L. M. (2021). Análise crítica da linguagem neutra como instrumento de reconhecimento de direitos das pessoas LGBTQIA+. Brazilian Journal of Development, 7(6), 54892-54913. https://doi.org/10.34117/bjdv7n6-067

Kovacic, D. (2019). Using the content validity index to determine content validity of an instrument assessing health care providers’ general knowledge of human trafficking. Journal of Human Trafficking, 4(4), 327-335. https://doi.org/10.1080/23322705.2017.1364905

Li, C. H. (2016). Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behavior Research Methods, 48(3), 936-949. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-015-0619-7

Medina, A. (2022). The impact workplace microaggressions have on those who identify as lesbian, gay and bisexual (Doctoral dissertation). National Louis University. https://digitalcommons.nl.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1764&context=diss

Mendes, W. G., & Silva, C. M. F. P. (2020). Homicídios da população de lésbicas, gays, bissexuais, travestis, transexuais ou transgêneros (LGBT) no Brasil: Uma análise espacial. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 25(5), 1709-1722. https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-81232020255.33672019

Nadal, K. L. (2019). A decade of microaggression research and LGBTQ communities: An introduction to the special issue. Journal of Homosexuality, 66(10), 1-8. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1539582

Nadal, K. L., Wong, Y., Issa, M., Meterko, V., Leon, J., & Wideman, M. (2011). Sexual orientation microaggressions: Processes and coping mechanisms for lesbian, gay, and bisexual individuals. Journal of LGBT Issues in Counseling, 5(1), 21-46. https://doi.org/10.1080/15538605.2011.554606

Palo, S., & Jha, K. K. (2020). Queer at work. Palgrave Macmillan.

Papadaki, V., Papadaki, E., & Giannou, D. (2021). Microaggression experiences in the workplace among Greek LGB social workers. Journal of Gay & Lesbian Social Services, 33(4), 512-532. https://doi.org/10.1080/10538720.2021.1892560

Parr, N. J., & Howe, B. G. (2019). Heterogeneity of transgender identity nonaffirmation microaggressions and their association with depression symptoms and suicidality among transgender persons. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity, 6(4), 461-474. https://doi.org/10.1037/sgd0000347

Redcay, A., Luquet, W., & Huggin, M.E. (2019). Immigration and asylum for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender individuals. Journal of Human Rights and Social Work, 4, 248-256. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41134-019-00092-2

Resnick, C. A., & Galupo, M. P. (2019). Assessing experiences with LGBT microaggressions in the workplace: Development and validation of the microaggression experiences at work scale. Journal of Homosexuality, 66(10), 1380-1403. https://doi.org/10.1080/00918369.2018.1542207

Richard, D. (2021). Workplace microaggressions experienced by sexual minorities: Relationships to workplace attitudes, mental health, and the role of emotional distress tolerance (Doctoral dissertation). University of Southern Mississippi. https://aquila.usm.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=2929&context=dissertations

Salgado, A. G. A. T., Araújo, L. F., Santos, J. V. O., Jesus, L. A., Fonseca, L. K. S., & Sampaio, D. S. (2017). LGBT old age: An analysis of the social representations among Brazilian elderly people. Ciencias Psicológicas, 11(2), 155-163. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v11i2.1487

Silva, D. W. G., Castro, G. H. C., & Siqueira, M. V. S. (2021). Ativismo LGBT organizacional: Debate e agenda de pesquisa. Revista Eletrônica de Ciência Administrativa, 20(3), 434-462. https://doi.org/10.21529/RECADM.2021015

Sooknanan, V. (2023). An investigation of LGBTQ+-specific workplace microaggressions: Their impact on job engagement and the buffering effects of organizational trust and identity disclosure (Master dissertation). Western University. https://ir.lib.uwo.ca/etd/9409/

Souza, E. R., Ispas, D., & Weselman, E. D. (2017). Workplace discrimination against sexual minorities: Subtle and not-so-subtle. Canadian Jornal of Administrative Sciences, 34(2), 121-132. https://doi.org/10.1002/cjas.1438