10.22235/cp.v17i2.2891

O núcleo da tríade sombria prediz o ambientalismo por meio da orientação à dominância social

The core of the dark triad predict environmentalism through social dominance orientation

El núcleo de la tríada oscura predice el ambientalismo a través de la orientación de dominancia social

Renan P. Monteiro1, ORCID 0000-0002-5745-3751

Lucas Queiroz da Cunha2, ORCID 0000-0001-7938-0170

Gleidson Diego Lopes Loureto3, ORCID 0000-0002-0889-6097

Iara Caroline Henrique Araújo4, ORCID 0000-0003-1406-0058

Carlos Eduardo Pimentel5, ORCID 0000-0003-3894-5790

1 Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Brasil, [email protected]

2 Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso, Brasil

3 Universidade Federal de Roraima, Brasil

4 Centro Universitário de Patos, Brasil

5 Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Brasil

Resumo:

O presente estudo objetivou verificar o papel mediador da orientação à dominância social na relação entre o núcleo da tríade sombria da personalidade e o ambientalismo. Participaram 305 pessoas com idades entre 18 e 77 anos (Midade = 26,4; DPidade = 11,25; 59,7 % mulheres). Os resultados indicaram que entre os 8 traços de personalidade analisados, considerando os modelos dos Cinco Grandes Fatores e da Tríade Sombria, apenas a psicopatia se correlacionou com ambientalismo, sendo que este se correlacionou moderadamente com a orientação à dominância social. Considerando que os três traços sombrios são talhados por déficits empáticos, baixa amabilidade e honestidade/humildade, testou-se o efeito do núcleo da tríade sombria da personalidade para a predição do ambientalismo, observando-se efeitos diretos. Contudo, tais efeitos diretos não se mantiveram estatisticamente significativos com a inclusão da orientação à dominância social, configurando uma mediação completa, posto que o núcleo da tríade sombria predisse indiretamente o ambientalismo. Logo, observa-se que a orientação à dominância social funciona como um mecanismo que possibilita pessoas com traços sombrios não se preocuparem com o meio ambiente, explorando-o em benefício próprio.

Palavras-chave: ambientalismo; personalidade; tríade sombria; orientação à dominância social.

Abstract:

The present study aimed to verify the mediating role of social dominance orientation in the relationship between the core of the dark triad and environmentalism. Participants were 305 people aged between 18 and 77 years old (Mage = 26.4; SDage = 11.25; 59.7 % women). The results indicated that among the 8 personality traits analyzed, considering the Big Five and Dark Triad models, only psychopathy was correlated with environmentalism, which was moderately correlated with social dominance orientation. Considering that the three dark traits shared empathic deficits, low agreeableness and honesty/humility, the effect of the dark triad core was tested for the prediction of environmentalism, observing direct effects. However, such direct effects did not remain statistically significant with the inclusion of social dominance orientation, configuring a complete mediation, since the dark core indirectly predicted environmentalism. Therefore, it is observed that social dominance orientation works as a mechanism that allows people with dark traits not to worry about the environment, exploiting it for their own benefit.

Keywords: environmentalism; personality; dark triad; social dominance orientation.

Resumen:

El presente estudio tuvo como objetivo verificar el papel mediador de la orientación a la dominancia social en la relación entre el núcleo de la tríada oscura y el ambientalismo. Participaron 305 personas con edades comprendidas entre 18 y 77 años (Medad = 26,4; DEedad = 11,25; 59,7 % mujeres). Los resultados indicaron que, entre los 8 rasgos de personalidad analizados considerando los modelos Big Five y Dark Triad, solo la psicopatía se correlacionó con el ambientalismo, que se correlacionó moderadamente con la orientación a la dominancia social. Considerando que los tres rasgos oscuros comparten déficits empáticos, baja amabilidad y honestidad/humildad, se probó el efecto del núcleo de la tríada oscura para la predicción del ambientalismo y se observaron efectos directos. Sin embargo, tales efectos directos no fueron estadísticamente significativos con la inclusión de la orientación a la dominancia social, configurando una mediación completa, ya que el núcleo oscuro predice indirectamente el ambientalismo. Por lo tanto, se observa que la dominancia social funciona como un mecanismo que permite a las personas con rasgos oscuros no preocuparse por el medio ambiente y explotarlo en beneficio propio.

Palabras clave: ambientalismo; personalidad; tríada oscura; orientación a la dominancia social.

Recebido: 30/04/2022

Aceito: 13/10/2023

As ações humanas causam um desequilíbrio ao meio-ambiente e isso consequentemente acaba trazendo implicações para os próprios seres humanos. Por exemplo, os incêndios florestais no Brasil estão relacionados ao aumento de hospitalizações por doenças respiratórias (Rocha, 2016). Na Colômbia, a exposição ao mercúrio, descartado em rios, está relacionado a um decréscimo em habilidades neurocognitivas em crianças e adolescentes (De la Ossa, 2021). Eventos relacionados a mudanças climáticas têm afetado a saúde mental das pessoas, especialmente aquelas que vivem em países em desenvolvimento (Palinkas & Wong, 2020), como o Brasil. Portanto, é necessário identificar predisposições individuais que podem explicar em alguma medida comportamentos pró e antiambientais.

Dentro deste contexto, a psicologia possui um papel central, de modo que a diminuição da crise ambiental depende de mudanças a nível individual (Zelezny & Schultz, 2000). Para propor intervenções que promovam ações pró-ambientais é necessário conhecer os preditores sociopsicológicos de tais comportamentos e das atitudes em relação ao meio-ambiente (Baldwin & Lammers, 2016). Nesta direção, Milfont (2021) indica que os traços de personalidade e as atitudes socioideológicas formariam as bases sociopsicológicas do ambientalismo.

Ambientalismo, traços de personalidade e atitudes socioideológicas

De forma geral, o ambientalismo pode ser conceituado como processos associados com ações que objetivem diminuir os impactos do homem na natureza (Zelezny & Schultz, 2000). Considerando o modelo dos Cinco Grandes Fatores de personalidade (CGF), amabilidade, conscienciosidade e abertura tem predito consistentemente o ambientalismo (Hirsh & Dolderman; 2007; Milfont & Sibley, 2012). Outro modelo de personalidade utilizado para o entendimento do ambientalismo é o HEXACO, tendo o fator honestidade/humildade como o preditor mais consistente (Milfont, 2021). Ademais, traços de personalidade explicam diferenças de sexo no ambientalismo, pois as mulheres são mais empáticas (Milfont & Sibley, 2016), amáveis, conscienciosas, honestas e humildes em comparação aos homens (Desrochers et al., 2019), tendo, consequentemente, mais atitudes e comportamentos pró-ambientais.

Apesar do papel importante dos CGF e do HEXACO para a compreensão do ambientalismo, cabe destacar os efeitos destrutivos que os seres humanos causam a natureza. Neste contexto, é fundamental explorar o papel que o lado sombrio da personalidade pode ter para explicar baixos níveis de ambientalismo. Na literatura, um modelo que cobre esse lado aversivo da personalidade humana é a Tríade Sombria, formada por maquiavelismo e pelas variações subclínicas de psicopatia e narcisismo (Paulhus & Williams, 2002). De acordo com esses autores, esses traços são marcados por tendências para a autopromoção, frieza emocional e agressividade, descrevendo pessoas que tem comportamento explorador e usam os demais em benefício próprio. Ademais, o núcleo da tríade sombria da personalidade é marcado por baixos níveis de amabilidade (Gouveia et al., 2016) e honestidade/humildade (Book et al., 2015), além de déficits na empatia afetiva (Wai & Tiliopoulos, 2012).

Recentemente, autores verificaram que a psicopatia e o maquiavelismo se associam negativamente ao apego ao lugar e a atitudes pró-ambientais (Huang et al., 2018). Observou-se, ainda, que a psicopatia medeia a relação entre sexo e ambientalismo, sendo que homens tem menor nível de ambientalismo por apresentarem escores mais elevados em psicopatia (Mertens et al., 2021). Ademais, tais traços sombrios estão negativamente relacionados a uma orientação empreendedora sustentável (Wu et al., 2019), a pouca priorização de valores biosféricos (e.g., priorizar o respeito à terra e a harmonia entre as espécies) e, consequentemente, não agindo em prol do meio ambiente (Ucar et al., 2023). Logo, observa-se que a falta de empatia, frieza emocional e tendência para explorar os demais em benefício próprio, que caracterizam o núcleo da tríade sombria da personalidade, podem ter um papel importante para o entendimento de comportamentos e atitudes em relação ao meio ambiente. Cabe ressaltar que a personalidade é uma variável distal em relação ao comportamento, havendo variáveis mais proximais ao ambientalismo que podem atuar como mediadores, a exemplo das atitudes socioideológicas (Milfont, 2021).

Especificamente, a Orientação à Dominância Social (ODS) é uma atitude socioideológica que descreve a extensão na qual um indivíduo aprova a ideia de uma sociedade hierarquizada e apoia as desigualdades sociais (Ho et al., 2015). A ODS se estende para além das relações sociais, sendo também uma barreira ideológica para o engajamento ambiental (Stanley et al., 2021). Pessoas com elevados níveis de ODS se veem hierarquicamente superiores ao meio ambiente, legitimando mitos sobre a dominação do homem sobre a natureza (Milfont et al., 2017), o que asseguraria a manutenção das hierarquias sociais, garantindo que grupos de maior status explorem e utilizem os recursos naturais, relegando aos grupos com status mais baixo as consequências dos desastres ambientais (Milfont & Sibley, 2014). Portanto, pessoas com elevada ODS usam o ambiente como um meio para manter a hierarquia e perpetuar as desigualdades sociais (Stanley et al., 2021), indicando que esta é uma variável central para entender ações e atitudes em relação ao meio ambiente, sendo uma ligação entre a personalidade sombria e o ambientalismo.

A ODS é uma atitude voltada para a competição, expressando valores como dominação, poder e superioridade, envolvendo uma percepção do mundo como uma selva competitiva (Duckitt, 2001; Duckitt & Sibley, 2016). Essa atitude socioideológica é relativamente estável e predita por certos traços básicos da personalidade, a exemplo dos traços que formam a Tríade Sombria (Lee et al., 2013; Perry & Sibley, 2012). Os traços sombrios se desenvolvem em resposta a um contexto com elevada competitividade e recursos escassos, sendo que características como manipulação, egoísmo e comportamento explorador, podem ser vantajosos, facilitando a obtenção de recursos em contextos restritos (Jonason et al., 2019). Portanto, a ODS seria um mecanismo que levaria pessoas com traços sombrios da personalidade a ter pouca preocupação com o meio ambiente, explorando-o em benefício próprio.

Método

Participantes

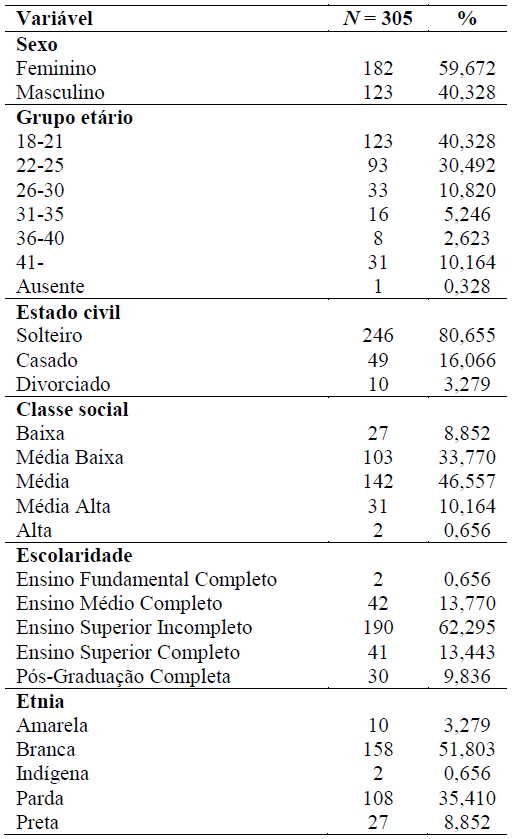

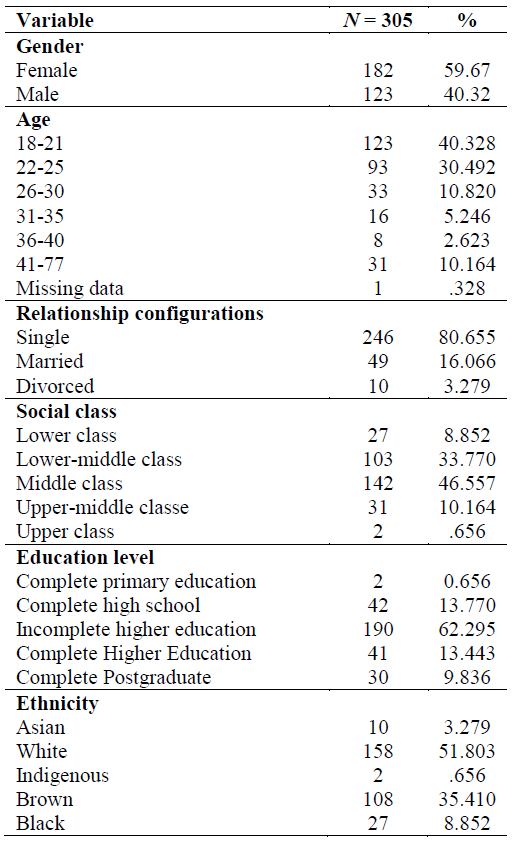

Participaram 305 pessoas com idades variando entre 18 e 77 anos (Midade = 26,4; DPidade = 11,25). Ademais, os participantes foram em maioria do sexo feminino (59,7 %) que se autodeclararam solteiros (78,4 %), brancos (51,8 %), de classe social média (46,6 %) e com ensino superior incompleto (61,6 %). Detalhes sobre o perfil sociodemográfico da amostra se encontram na Tabela 1.

Em relação ao tamanho da amostra, utilizou-se a calculadora online de Soper (2023) para estimar o número mínimo da amostra necessária para testar o modelo via Modelagem por Equações Estruturais. No caso, considerando que o modelo possui três variáveis latentes e 11 variáveis observadas, estimou-se o número mínimo de participantes para se obter um poder de 0,80, um tamanho de efeito grande (> 0,5) e um alfa igual ou menor do que 0,05. Os resultados indicaram que o mínimo de amostra recomendada seria de 123 participantes, logo, os 305 participantes do presente estudo são suficientes para a realização das análises planejadas.

Tabela 1: Características sociodemográficas

Instrumentos

New Ecological Paradigm Scale (NEP; Dunlap et al., 2000). Medida adaptada para o Brasil por Pires et al. (2016), é composto por 15 itens (ω = 0,70) que avaliam o grau de endosso em relação a uma visão de mundo ecológica. Os participantes são orientados a indicar em uma escala de cinco pontos (1: Discordo Fortemente; 5: Concordo Fortemente) o quanto os itens o descrevem, a exemplo de “Quando humanos interferem na natureza, isso frequentemente produz consequências desastrosas” e “Plantas e animais têm o mesmo direito de existir que humanos”. Ademais, foram incluídos dois itens relacionados a atitudes frente a mudança climática: “A mudança climática é real” e “A mudança climática é causada pelos seres humanos”.

Two Dimensional MACH-IV (TDM-IV; Monaghan et al., 2016). Medida adaptada para o Brasil por Monteiro et al. (2022), formada por 10 itens que avaliam tanto visões (ω = 0,59) quanto táticas (ω = 0,74) maquiavélicas. Os participantes são orientados a indicar o seu nível de concordância (1: Discordo Fortemente; 5: Concordo Fortemente) a itens como “Quem confia completamente em alguém está pedindo para ter problemas” e “É difícil ter sucesso sem pegar atalhos”.

Narcissistic Personality Inventory-13 (NPI-13; Gentile et al., 2013). Os itens desta medida foram traduzidos por Monteiro (2017), sendo que esta versão da NPI é formada por 13 itens (ω = 0,81), tendo como objetivo mensurar o nível de narcisismo dos indivíduos. Os participantes são orientados a indicar a sua concordância (1: Discordo Fortemente; 5: Concordo Fortemente) a itens como “Eu gosto de me olhar no espelho” e “Usualmente tento me exibir quando tenho a oportunidade”.

Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy (Levenson et al., 1995). Medida adaptada para o Brasil por Hauck-Filho e Teixeira (2014), sendo formada por 26 itens (ω = 0,82), os quais são respondidos em escala de quatro pontos, sendo os participantes orientados a indicar a sua concordância (1: Discordo Totalmente; 4: Concordo Totalmente) a itens como “Fazer dinheiro é minha meta mais importante” e “Eu não planejo nada com muita antecedência”.

Big Five Inventory-20 (Veloso Gouveia et al., 2021). Esse instrumento é formado por 20 itens, tendo como objetivo captar a autopercepção do indivíduo sobre os cinco grandes fatores de personalidade. No caso, os participantes devem indicar em que medida concordam (1: Discordo Totalmente; 5: Concordo Totalmente) com cada item descrevendo a sua personalidade, a exemplo de “Gosta de cooperar com os outros” (Amabilidade; ω = 0,70), “É temperamental, muda de humor com frequência” (Neuroticismo; ω = 0,77), “Gosta de refletir, brincar com as ideias” (Abertura; ω = 0,75), “Gera muito entusiasmo” (Extroversão; ω = 0,81) e “Faz as coisas com eficiência” (Conscienciosidade; ω = 0,74).

Social Dominance Orientation 7 Scale (SDO7; Ho et al., 2015). Adaptada para o Brasil por Vilanova et al. (2022), sendo formada por 16 itens (ω = 0,89), aos quais os participantes devem indicar seu nível de concordância (1: Discordo Fortemente; 7: Concordo Fortemente) a itens como “Nenhum grupo deveria dominar na sociedade” e “Alguns grupos são simplesmente inferiores aos outros”.

Procedimento

Os dados foram coletados por meio de um questionário online utilizando-se do procedimento de amostragem bola de neve, sendo o link da pesquisa divulgado nas redes sociais. Prévio ao preenchimento dos instrumentos, os participantes deveriam ler e concordar com o Termo de Consentimento Livre e Esclarecido, no qual eram informados sobre os objetivos do estudo, o caráter anônimo e voluntário da participação e que poderiam declinar da pesquisa a qualquer momento, sem acarretar prejuízos. Assevera-se que o presente estudo seguiu a Resolução 510/16, que orienta as pesquisas nas ciências humanas e sociais, tendo parecer favorável do comitê de ética em pesquisa (CAAE 31360920.1.0000.5181).

Análise de dados

Os dados foram tabulados e analisados por meio do SPSS e AMOS. Com o primeiro, foram calculadas análises descritivas (média, desvio padrão) e inferenciais, especificamente análise de correlação de Pearson para conhecer o padrão geral de associação entre as variáveis. Com o segundo software, foi realizada uma Modelagem por Equações Estruturais (estimador Maximum Likelihood), testando um modelo mediacional. Para atestar a qualidade do modelo, tiveram-se em conta os seguintes indicadores de ajuste do modelo aos dados (entre parênteses valores para um modelo aceitável Hair et al., 2015): χ²/gl, Comparative Fit Index (acima de 0,90), Tucker-Lewis Index (acima de 0,90) e Root Mean Error of Approximation (abaixo de 0,08).

Resultados

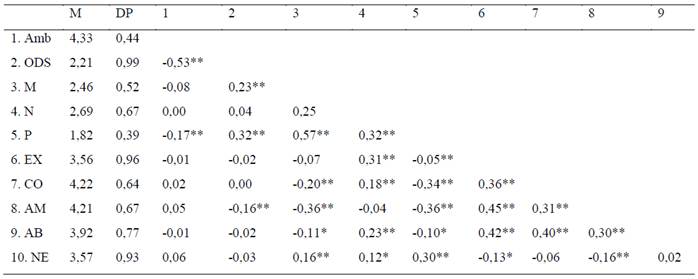

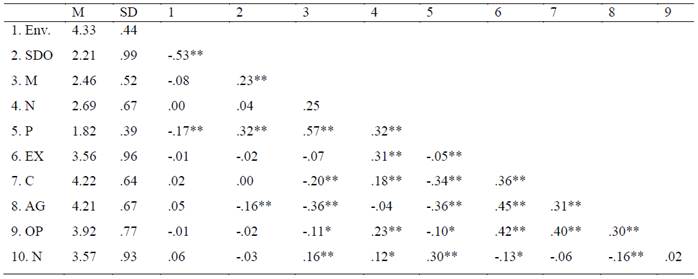

Inicialmente, foram calculadas análises de correlação de Pearson para conhecer o padrão geral de relação entre as variáveis. No caso, entre os oito traços de personalidade, apenas a psicopatia (r = -0,17; p < 0,01) se correlacionou de forma significativa com o ambientalismo (cômputo da NEP e dos itens sobre mudança climática). Verificou-se, ainda, que a ODS apresentou correlação moderada com o ambientalismo (r = -0,53; p < 0,001). Na Tabela 2 é possível observar em mais detalhes as relações entre todas as variáveis.

Tabela 2: Relações entre ambientalismo, orientação à dominância e personalidade

Nota: Identificação das variáveis: Amb: Ambientalismo;

ODS: Orientação à Dominância Social; M: Maquiavelismo; N: Narcisismo; P:

Psicopatia; EX: Extroversão; CO: Conscienciosidade; AM: Amabilidade; AB:

Abertura; NE: Neuroticismo.

*p < 0,05; **p

< 0,001 (teste unicaudal)

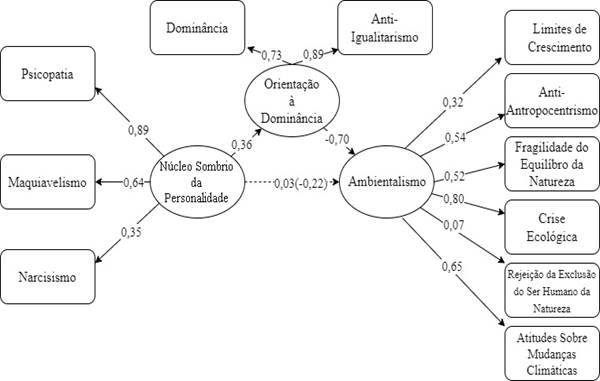

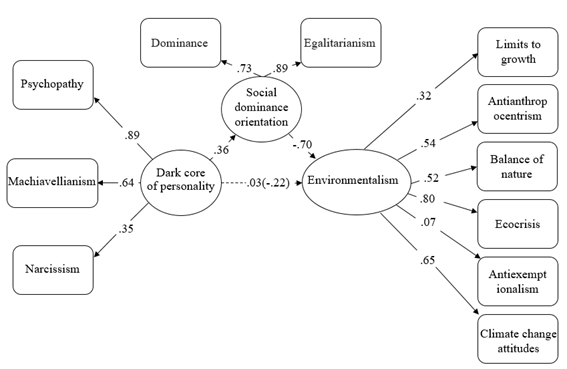

O passo seguinte foi testar os efeitos diretos e indiretos dos traços sombrios de personalidade e das atitudes socioideológicas para a predição do ambientalismo (Figura 1). Considerando que os três traços sombrios têm em comum uma tendência para a manipulação, insensibilidade e comportamento explorador, modelou-se uma variável latente tendo os três traços como variáveis observáveis, formando assim o núcleo da personalidade sombria, predizendo a orientação à dominância, modelada por meio de duas variáveis observadas (Dominância e Anti-igualitarismo), explicando diretamente o Ambientalismo, modelada pelas cinco facetas da escala NEP, mais dois itens avaliando atitudes em relação à mudança climática. Cabe ressaltar que o modelo CGF foi considerado na presente pesquisa para efeitos de controle, contudo, nenhum dos traços deste modelo se correlacionou com o ambientalismo, optamos por não o incluir na testagem do modelo.

Por meio de bootstrap com 5.000 reamostragens, verificaram-se inicialmente efeitos diretos da personalidade sombria no ambientalismo (λ = -0,22; IC90% = ‑0,33/‑0,10, p < 0,05). Após a inserção da ODS como mediadora, verificaram-se efeitos indiretos dos traços sombrios no ambientalismo (λ = -0,25; IC90% = ‑0,36/‑0,17, p < 0,001), sendo essa mediação completa, posto que os efeitos diretos da personalidade sombria no ambientalismo deixaram de ser estatisticamente significativos (λ = 0,03, IC 90% = -0,08/0,16, p = 0,65) com a inclusão da ODS, que predisse diretamente o desfecho (λ = 0,36, IC 90% = 0,25/0,48, p < 0,001). Finalmente, o modelo testado apresentou indicadores de ajuste aceitáveis (χ²/gl = 1,87, CFI = 0,95, TLI = 0,93, RMSEA = 0,054).

Figura 1: Modelo de mediação testado

|

Discussão

O problema das mudanças climáticas e das ações antiambientais no Brasil é uma questão ainda em aberto. O país ainda possui pouco tratamento de esgoto, além de ter parte de sua rica biodiversidade seriamente ameaçada por conta da ação humana (Feng et al., 2021; Tomas et al., 2021). Compreender as bases sociopsicológicas dos comportamentos e atitudes em relação ao meio ambiente é crucial, de modo que a diminuição dos problemas ambientais perpassa por mudanças a nível individual (Zelezny & Schultz, 2000). No presente estudo, aportamos com evidências acerca da influência direta de atitudes socioideológicas e indiretas do núcleo da tríade sombria da personalidade sobre o ambientalismo.

Apesar do enfoque que a literatura dá ao modelo CGF (Hirsh & Dolderman; 2007; Milfont & Sibley, 2012), observou-se que nenhum dos cinco fatores se relacionou com o ambientalismo. Por outro lado, no modelo de regressão, verificou-se o efeito direto do núcleo da tríade sombria de personalidade na predição do ambientalismo, o que sugere que traços aversivos da personalidade são prejudiciais não apenas nas relações interpessoais, mas também para as relações pessoa-ambiente. A propósito, tais evidências somam-se a dados prévios da literatura (Huang et al., 2018; Ucar et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2019), denotando que pessoas com traços sombrios não se preocupam com o meio-ambiente, explorando-o em benefício próprio sem se preocupar com sua reposição/preservação. Os traços que formam o lado sombrio da personalidade humana apresentam em comum baixos níveis de amabilidade (Gouveia et al., 2016) e honestidade/humildade (Book et al., 2015), além de déficits empáticos (Wai & Tiliopoulos, 2012), sendo que esses aspectos compartilhados são preditores do ambientalismo (Hirsh & Dolderman; 2007; Milfont & Sibley, 2012, 2016).

Portanto, em razão dos aspectos que caracterizam o núcleo da tríade sombria da personalidade, percebe-se que pessoas com elevados níveis nesse agrupamento de traços não conseguem se preocupar com o ambiente natural e com os outros animais. Questões relativas à preservação do meio ambiente são vistas como sem importância por pessoas com escores elevados no núcleo da tríade sombria (Ucar et al., 2023). Não obstante, cabe ressaltar que a magnitude das relações entre personalidade e ambientalismo é menor em comparação as atitudes socioideológicas em razão da natureza distal da personalidade. A propósito, quando a ODS é incluída no modelo, a personalidade sombria deixa de predizer diretamente o ambientalismo, tendo efeitos indiretos, atestando a mediação completa da ODS, confirmando o papel que esta variável tem como preditor direto do ambientalismo, em linha com estudos prévios (Milfont et al., 2017; Stanley et al., 2021).

Nesse ponto, cabe destacar que a ODS funciona como um mecanismo que possibilita pessoas com personalidade sombria a adotar atitudes e comportamentos antiambientais. No caso, os traços sombrios são úteis em contextos de escassez e alta competitividade, tornando o indivíduo mais apto a extrair recursos em contextos restritos (Jonason et al., 2019). Isso leva pessoas com esse perfil de personalidade a terem uma maior orientação à dominância social, caracterizada como uma atitude socioideológica que envolve a percepção do mundo como uma selva competitiva, expressando valores como dominação, poder e superioridade (Duckitt, 2001; Duckitt & Sibley, 2016), resultando em menores níveis de ambientalismo, vendo-se superior a natureza e no direito de dominá-la e utilizá-la em benefício próprio (Milfont et al., 2013; Milfont & Sibley, 2014).

Percebe-se que a ODS funcionaria como um mecanismo que possibilitaria pessoas com traços sombrios dominarem a natureza e a explorarem para a obtenção de recursos. Cabe ressaltar, ainda, que por se enxergarem como superiores a natureza, aliado a serem extremamente individualistas (Paulhus & Williams, 2002), pessoas com traços sombrios optam por não modificarem sua rotina diária (e.g., economizar água e energia, reduzir o uso dos veículos) em prol do meio ambiente.

Apesar dos resultados promissores, é importante analisá-los com cautela. Algumas limitações do estudo são a amostra não probabilística, formada majoritariamente por universitários, além da desejabilidade social. Em estudos futuros é importante contar com amostras maiores e mais heterogêneas (e.g., distribuição mais equitativa em relação ao nível de escolaridade, etnia e classe socioeconômica), além de testar o papel de outros traços aversivos da personalidade (e.g., sadismo, ganância, despeito) e utilizar medidas comportamentais para aferir o comportamento pró/antiambiental. Portanto, percebe-se que as possibilidades de estudo não se esgotam aqui, havendo uma ampla possibilidade de pesquisas para predizer comportamentos e atitudes em relação ao meio ambiente e, a partir do mapeamento dos preditores, propor estratégias de intervenção visando a promoção do ambientalismo.

Referencias:

Baldwin, M., & Lammers, J. (2016). Past-focused environmental comparisons promote proenvironmental outcomes for conservatives. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113, 14953-14957. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1610834113

Book, A., Visser, B. A., & Volk, A. A. (2015). Unpacking “evil”: Claiming the core of the Dark Triad. Personality and Individual Differences, 73, 29-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.09.016

De la Ossa, C. T. A. (2021). Habilidades intelectuais e suas interfaces neurocognitivas em crianças e adolescentes expostos ao mercúrio [Dissertação de Mestrado não publicada]. Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso.

Desrochers, J. E., Albert, G., Milfont, T. L., Kelly, B., & Arnocky, S. (2019). Does personality mediate the relationship between sex and environmentalism? Personality and Individual Differences, 147, 204-213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.04.026

Duckitt, J. (2001). A dual-process cognitive-motivational theory of ideology and prejudice. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 33, 41-113. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(01)80004-6

Duckitt, J., & Sibley, C. G. (2016). Personality, ideological attitudes, and group identity as predictors of political behavior in majority and minority ethnic groups. Political Psychology, 37, 109-124. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12222

Dunlap, R. E., Van Liere, K. D., Merting, A. G., & Jones, R. E. (2000). Measuring endorsement of the New Ecological Paradigm: A revised NEP Scale. Journal of Social Issues, 56, 425-442. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00176

Feng, X., Merow, C., Liu, Z., Park, D. S., Roehrdanz, P. R., Maitner, B., Newman, E. A., Boyle, B. L., Lien, A., Burger, J. R., Pires, M. M., Brando, P. M., Bush, M. B., McMichael, C. N. H., Neves, D. M., Nikolopoulos, E. I., Saleska, S. R., Hannah, L., Breshears, D. D., … Enquist, B. J. (2021). How deregulation, drought and increasing fire impact Amazonian biodiversity. Nature, 597(7877), 516-521. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03876-7

Gentile, B., Miller, J. D., Hoffman, B. J., Reidy, D. E., Zeichner, A., & Campbell, W. K. (2013). A Test of Two Brief Measures of Grandiose Narcissism: The Narcissistic Personality Inventory-13 and the Narcissistic Personality Inventory-16. Psychological Assessment, 25, 1120-1136. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033192

Gouveia, V. V., Monteiro, R. P., Gouveia, R. S. V., Athayde, R. A. A., & Cavalcanti, T. M. (2016). Assessing the dark side of personality: Psychometric evidences of the dark triad dirty dozen. Revista Interamericana de Psicología, 50(3), 420-432. https://doi.org/10.30849/rip/ijp.v50i3.126

Hair, J. F. Jr., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2015). Multivariate Data Analysis (7ª ed.). Prentice Hall.

Hauck-Filho, N., & Teixeira, M. A. P. (2014). Revisiting the psychometric properties of the Levenson Self-Report Psycopathy Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 96, 459-464. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2013.865196

Hirsh, J. B., & Dolderman, D. (2007). Personality predictors of consumerism and environmentalism: A preliminary study. Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 1583-1593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.04.015

Ho, A. K., Sidanius, J., Kteily, N., Sheehy-Skeffington, J., Pratto, F., Henkel, K. E., Foels, R., & Stewart, A. L. (2015). The nature of social dominance orientation: Theorizing and measuring preferences for intergroup inequality using the new SDO₇ scale. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(6), 1003–1028. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000033

Huang, N., Zuo, S., Wang, F., Cai, P., & Wang, F. (2019). Environmental attitudes in China: The roles of the Dark Triad, future orientation and place attachment. International Journal of Psychology, 54, 563-572. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12518

Jonason, P. K., Okan, C., & Özsoy, E. (2019). The dark triad traits in Australia and Turkey. Personality and Individual Differences, 149, 123-127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.05.058

Lee, K., Ashton, M. C., Wiltshire, J., Bourdage, J. S., Visser, B. A., & Gallucci, A. (2013). Sex, power, and money: Prediction from the Dark Triad and Honesty-Humility. European Journal of Personality, 27, 169-184. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.1860

Levenson, M. R., Kiehl, K. A., & Fitzpatrick, C. M. (1995). Assessing psychopathic attributes in a noninstitutionalized population. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 151-158. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.1.151

Mertens, A., von Krause, M., Denk, A., & Heitz, T. (2021). Gender differences in eating behavior and environmental attitudes-The mediating role of the Dark Triad. Personality and Individual Differences, 168, 110359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110359

Milfont, T. L. (2021). Where does pro-environmental tendencies fit within a taxonomy of personality traits? Em A. Frazen & S. Mader (Eds.), Handbook of Environmental Sociology (pp. 97-115). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Milfont, T. L., & Sibley, C. G. (2012). The big five personality traits and environmental engagement: Associations at the individual and societal level. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 32, 187-195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2011.12.006

Milfont, T. L., & Sibley, C. G. (2014). The hierarchy enforcement hypothesis of environmental exploitation: A social dominance perspective. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 55, 188-193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2014.07.006

Milfont, T. L., & Sibley, C. G. (2016). Empathic and social dominance orientations help explain gender differences in environmentalism: A one-year Bayesian mediation analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 90, 85-88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.10.044

Milfont, T. L., Bain, P. G., Kashima, Y., Corral-Verdugo, V., Pasquali, C., Johansson, L.-O., Guan, Y., Gouveia, V. V., Garðarsdóttir, R. B., Doron, G., Bilewicz, M., Utsugi, A., Aragones, J. I., Steg, L., Soland, M., Park, J., Otto, S., Demarque, C., Wagner, C., … Einarsdóttir, G. (2017). On the relation between social dominance orientation and environmentalism. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 9(7), 802-814. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617722832

Milfont, T. L., Richter, I., Sibley, C. G., Wilson, M. S., & Fischer, R. (2013). Environmental consequences of the desire to dominate and be superior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39, https://doi.org/1127-1138. 10.1177/0146167213490805

Monaghan, C., Bizumic, B., & Sellbom, M. (2016). The role of Machiavellian views and tactics in psychopathology. Personality and Individual Differences, 94, 72-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.01.002

Monteiro, R. P. (2017). Tríade sombria da personalidade: conceitos, medição e correlatos [Tese de Doutorado]. Universidade Federal da Paraíba.

Monteiro, R. P., Coelho, G. L. H., Cavalcanti, T. M., Grangeiro, A. S. M., & Gouveia, V. V. (2022). The ends justify the means? Psychometric parameters of the MACH-IV, the two-dimensional MACH-IV and the trimmed MACH in Brazil. Current Psychology, 41, 4088-4098. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00892-0

Palinkas, L. A., & Wong, M. (2020). Global climate change and mental health. Current Opinion in Psychology, 32, 12-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.06.023

Paulhus, D. L., & Williams, K. M. (2002). The Dark Triad of personality: narcissism, machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 36, 556-563. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00505-6

Perry, R., & Sibley, C. G. (2012). Big-Five personality prospectively predicts social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(1), 3-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.08.009

Pires, P., Ribas Junior, R. C., Hora, G., Filgueiras, A. & Lopes, D. (2016). Psychometric properties for the Brazilian version of the New Ecological Paradigm revised. Temas em Psicologia, 24, 1407-1419. https://dx.doi.org/10.9788/TP2016.4-12

Rocha, L. R. L. (2016). A correlação entre doenças respiratórias e o incremento das queimadas em Alta Floresta e Peixoto de Azevedo norte do Mato Grosso-Amazônia Legal. Revista Brasileira de Políticas Públicas, 6, 246-254. https://doi.org/10.5102/rbpp.v6i1.3484

Soper, D. (2023, outubro 12). Free Statistics Calculators (version 4.0). Statistics Calculators. https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc/calculator.aspx?id=89

Stanley, S. K., Wilson, M. S., & Milfont, T. L. (2021). Social dominance as an ideological barrier to environmental engagement: Qualitative and quantitative insights. Global Environmental Change, 67, 102223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102223

Tomas, W. M., Berlinck, C. N., Chiaravalloti, R. M., Faggioni, G. P., Strüssmann, C., Libonati, R., Abrahão, C. R., do Valle Alvarenga, G., de Faria Bacellar, A. E., de Queiroz Batista, F. R., Bornato, T. S., Camilo, A. R., Castedo, J., Fernando, A. M. E., de Freitas, G. O., Garcia, C. M., Gonçalves, H. S., de Freitas Guilherme, M. B., Layme, V. M. G., … Morato, R. (2021). Distance sampling surveys reveal 17 million vertebrates directly killed by the 2020’s wildfires in the Pantanal, Brazil. Scientific Reports, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-02844-5

Ucar, G. K., Malatyalı, M. K., Planalı, G. Ö., & Kanik, B. (2023). Personality and pro-environmental engagements: the role of the Dark Triad, the Light Triad, and value orientations. Personality and Individual Differences, 203, 112036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.112036

Veloso Gouveia, V., de Carvalho Rodrigues Araújo, R., Vasconcelos de Oliveira, I. C., Pereira Gonçalves, M., Milfont, T., Lins de Holanda Coelho, G., Santos, W., De Medeiros, E. D., Silva Soares, A. K., Pereira Monteiro, R., Moura de Andrade, J., Medeiros Cavalcanti, T., Da Silva Nascimento, B., & Gouveia, R. (2021). A short version of the Big Five Inventory (BFI-20): evidence on construct validity. Revista Interamericana de Psicología/Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 55(1), e1312. https://doi.org/10.30849/ripijp.v55i1.1312

Vilanova, F., Soares, D., de Quadros Duarte, M., & Costa, Â. B. (2022). Evidências de Validade da Escala de Orientação à Dominância Social no Brasil. Psico-USF, 27(3). https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-82712024270303

Wai, M., & Tiliopoulos, N. (2012). The affective and cognitive empathic nature of the dark triad of personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 794-799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.01.008

Wu, W., Wang, H., Lee, H.-Y., Lin, Y.-T., & Guo, F. (2019). How Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and narcissism affect sustainable entrepreneurial orientation: The moderating effect of psychological resilience. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 779. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00779

Zelezny, L. C., & Schultz, P. W. (2000). Psychology of promoting environmentalism: promoting environmentalism. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 365-371. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00172

Disponibilidade de dados: O conjunto de dados que embasa os resultados deste estudo não está disponível.

Como citar: Monteiro, R. P., da Cunha, L. Q., Loureto, G. D. L., Araújo, I. C. H., & Pimentel, C. E. (2023). O núcleo da tríade sombria prediz o ambientalismo por meio da orientação à dominância social. Ciencias Psicológicas, 17(2), e-2891. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i2.2891

Participação dos autores: a) Planejamento e concepção do trabalho; b) Coleta de dados; c) Análise e interpretação de dados; d) Redação do manuscrito; e) Revisão crítica do manuscrito.

R. P. M. contribuiu em a, b, c, d, e; L. C. Q. em a, b, d, e; G. D. L. L. em a, b, d, e; I. C. H. A. em a, b, d, e; C. E. P. em c, d, e.

Editora científica responsável: Dra. Cecilia Cracco.

10.22235/cp.v17i2.2891

Original Articles

The core of the dark triad predict environmentalism through social dominance orientation

O núcleo da tríade sombria prediz o ambientalismo por meio da orientação à dominância social

El núcleo de la tríada oscura predice el ambientalismo a través de la orientación de dominancia social

Renan P. Monteiro1, ORCID 0000-0002-5745-3751

Lucas Queiroz da Cunha2, ORCID 0000-0001-7938-0170

Gleidson Diego Lopes Loureto3, ORCID 0000-0002-0889-6097

Iara Caroline Henrique Araújo4, ORCID 0000-0003-1406-0058

Carlos Eduardo Pimentel5, ORCID 0000-0003-3894-5790

1 Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Brazil, [email protected]

2 Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso, Brazil

3 Universidade Federal de Roraima, Brazil

4 Centro Universitário de Patos, Brazil

5 Universidade Federal da Paraíba, Brazil

Abstract:

The present study aimed to verify the mediating role of social dominance orientation in the relationship between the core of the dark triad and environmentalism. Participants were 305 people aged between 18 and 77 years old (Mage = 26.4; SDage = 11.25; 59.7 % women). The results indicated that among the 8 personality traits analyzed, considering the Big Five and Dark Triad models, only psychopathy was correlated with environmentalism, which was moderately correlated with social dominance orientation. Considering that the three dark traits shared empathic deficits, low agreeableness and honesty/humility, the effect of the dark triad core was tested for the prediction of environmentalism, observing direct effects. However, such direct effects did not remain statistically significant with the inclusion of social dominance orientation, configuring a complete mediation, since the dark core indirectly predicted environmentalism. Therefore, it is observed that social dominance orientation works as a mechanism that allows people with dark traits not to worry about the environment, exploiting it for their own benefit.

Keywords: environmentalism; personality; dark triad; social dominance orientation.

Resumo:

O presente estudo objetivou verificar o papel mediador da orientação à dominância social na relação entre o núcleo da tríade sombria da personalidade e o ambientalismo. Participaram 305 pessoas com idades entre 18 e 77 anos (Midade = 26,4; DPidade = 11,25; 59,7 % mulheres). Os resultados indicaram que entre os 8 traços de personalidade analisados, considerando os modelos dos Cinco Grandes Fatores e da Tríade Sombria, apenas a psicopatia se correlacionou com ambientalismo, sendo que este se correlacionou moderadamente com a orientação à dominância social. Considerando que os três traços sombrios são talhados por déficits empáticos, baixa amabilidade e honestidade/humildade, testou-se o efeito do núcleo da tríade sombria da personalidade para a predição do ambientalismo, observando-se efeitos diretos. Contudo, tais efeitos diretos não se mantiveram estatisticamente significativos com a inclusão da orientação à dominância social, configurando uma mediação completa, posto que o núcleo da tríade sombria predisse indiretamente o ambientalismo. Logo, observa-se que a orientação à dominância social funciona como um mecanismo que possibilita pessoas com traços sombrios não se preocuparem com o meio ambiente, explorando-o em benefício próprio.

Palavras-chave: ambientalismo; personalidade; tríade sombria; orientação à dominância social.

Resumen:

El presente estudio tuvo como objetivo verificar el papel mediador de la orientación a la dominancia social en la relación entre el núcleo de la tríada oscura y el ambientalismo. Participaron 305 personas con edades comprendidas entre 18 y 77 años (Medad = 26,4; DEedad = 11,25; 59,7 % mujeres). Los resultados indicaron que, entre los 8 rasgos de personalidad analizados considerando los modelos Big Five y Dark Triad, solo la psicopatía se correlacionó con el ambientalismo, que se correlacionó moderadamente con la orientación a la dominancia social. Considerando que los tres rasgos oscuros comparten déficits empáticos, baja amabilidad y honestidad/humildad, se probó el efecto del núcleo de la tríada oscura para la predicción del ambientalismo y se observaron efectos directos. Sin embargo, tales efectos directos no fueron estadísticamente significativos con la inclusión de la orientación a la dominancia social, configurando una mediación completa, ya que el núcleo oscuro predice indirectamente el ambientalismo. Por lo tanto, se observa que la dominancia social funciona como un mecanismo que permite a las personas con rasgos oscuros no preocuparse por el medio ambiente y explotarlo en beneficio propio.

Palabras clave: ambientalismo; personalidad; tríada oscura; orientación a la dominancia social.

Received: 30/04/2022

Accepted: 13/10/2023

A few examples of the devastating consequences that people can have on the environment include forest fires, rising global temperatures, melting polar ice caps, pollution of rivers and oceans, and the possibility of the extinction of many animal species. Brazilian biodiversity is seriously at danger due to human activity. In the Brazilian Amazonia, for example, the data shows that between 77.3 % and 85.2 % of species at risk of extinction have their habitat affected by fires (Feng et al., 2021). Yet in Brazil, for the Pantanal biome, in 2020, the largest fires in its history were recorded, with 26 % of the biome destroyed and 17 million vertebrates killed (Tomas et al., 2021). In addition, recent environmental disasters in Brazil, such as those in Brumadinho and Mariana, increase the alarming environmental issue in Brazil, which has been configured as a scenario marked by impunity against environmental crimes.

Human actions provoke environmental imbalances that, in turn, are followed by numerous problems for humans themselves. For instance, hospitalizations for respiratory illnesses are associated with forest fires in Brazil (Rocha, 2016). Data from Colombia showed that exposure to mercury discharged into rivers is related to a decrease in neurocognitive abilities in children and adolescents (De la Ossa, 2021). Events related to climate change have affected people’s mental health, especially those living in developing countries (Palinkas & Wong, 2020), such as Brazil. Therefore, it is necessary to identify individual predispositions that can explain, to some extent, pro- and anti-environmental actions and behaviors.

Within this context, psychology plays a central role, so reducing the environmental crisis depends on changes at the individual level (Zelezny & Schultz, 2000). In order to promote pro-environmental actions, it is necessary to map the sociopsychological predictors of such behaviors and attitudes related to the environment. Thus, Milfont (2021) showed that personality traits and socio-ideological attitudes would be the sociopsychological bases of environmentalism.

Environmentalism, personality traits and socio-ideological attitudes

Environmentalism can generally be understood as a set of procedures linked to actions aimed at reducing human impact on the natural world (Zelezny & Schultz, 2000). Taking into account the Five Factor Model (FFM), agreeableness, conscientiousness, and openness have consistently predicted environmentalism (Hirsh & Dolderman; 2007; Milfont & Sibley, 2012). Another personality model used to understand environmentalism is HEXACO, with the honesty/humility factor as the most consistent predictor (Milfont, 2021). Furthermore, personality traits explain sex differences in environmentalism, as women are more empathetic (Milfont & Sibley, 2016), kind, conscientious, honest, and humble compared to men (Desrochers et al., 2019), consequently having more pro-environmental attitudes and behaviors.

Despite the critical role of FFM and HEXACO in understanding environmentalism, it is worth highlighting the destructive effects that human beings have on nature. In this context, it is essential to explore the role of the dark side of personality in explaining low levels of environmentalism. The Dark Triad, which is composed of subclinical forms of narcissism and psychopathy as well as Machiavellianism, is a model that addresses this unpleasant aspect of the human psyche in the literature (Paulhus & Williams, 2002). According to these authors, these traits are marked by characteristics such as aggressiveness, emotional detachedness, and self-promotional inclinations that characterize people who take advantage of others and behave exploitatively. Furthermore, the core of the dark triad of personality is marked by low levels of agreeableness (Gouveia et al., 2016) and honesty/humility (Book et al., 2015), in addition to deficits in affective empathy (Wai & Tiliopoulos, 2012).

Recently, some studies found that psychopathy and Machiavellianism are negatively associated with place attachment and pro-environmental attitudes (Huang et al., 2018). Psychopathy was also found to play a role in the association between gender and environmentalism. Men have a lower environmentalism score due to higher psychopathy scores (Mertens et al., 2021). In addition, these dark attributes are associated with a “sustainable business model” (Wu et al., 2019), a low focus on biospheric values (“respect for the earth” and “harmony between species”) and, as a result, not acting in for the environment (Ucar et al., 2023). Therefore, it is observed that the empathy deficit, the emotional coldness, and the need to take advantage of others for personal gain, which are at the core of a dark triad personality type, can play a significant role in understanding behavior and attitudes toward the environment. It is worth noting that personality is a distal variable in relation to behavior, with variables more proximal to environmentalism that can act as mediators, such as socio-ideological attitudes (Milfont, 2021).

Specifically, Social Dominance Orientation (SDO) is a socio-ideological attitude that describes how an individual approves of a hierarchical society and supports social inequalities (Ho et al., 2015). Social Dominance Orientation extends beyond social relationships and is also an ideological barrier to environmental engagement (Stanley et al., 2021). People with high levels of SDO see themselves as hierarchically superior to the environment, legitimizing myths about man’s domination over nature (Milfont et al., 2017), which would ensure the maintenance of social hierarchies, ensuring that higher status groups explore and use natural resources, transferring the consequences of environmental disasters to groups with lower status (Milfont & Sibley, 2014). Therefore, people scoring higher on SDO use the environment to maintain hierarchy and perpetuate social inequalities (Stanley et al., 2021), indicating that this is a central variable for understanding actions and attitudes towards the environment, linking dark personality and environmentalism.

The SDO is conceived as attitudes related to competition encompassing values such as domination, power, and superiority, which involve a perception of the world as a competitive jungle (Duckitt, 2001; Duckitt & Sibley, 2016). This socio-ideological attitude is relatively stable and predicted by certain basic personality traits, such as the traits that form the Dark Triad (Lee et al., 2013; Perry & Sibley, 2012). In sum, dark traits are developed in response to a context with high competitiveness and scarce resources, and characteristics such as manipulation, selfishness, and exploitative behavior can be advantageous, facilitating the obtaining of resources in restricted contexts (Jonason et al., 2019). Therefore, the SDO would be a mechanism that would lead people with dark personality traits to have little concern for the environment, exploiting it for their own benefit.

Considering the previously mentioned, the current study aims to verify the mediating role of SDO in the relationship between the core of the dark triad of personality and environmentalism. It is hypothesized that the core of the dark triad will indirectly predict environmentalism, doing so through SDO; the latter variable will directly predict environmentalism.

Method

Participants

Participants were 305 from the general population, ranging in age from 18 to 77 years old (Mage = 26.4; SDage = 11.25). Most of them were female (59.7 %), single (78.4 %), white (51.8 %), from a middle-class background (46.6 %), and undergraduate students (61.6 %). Details about the sociodemographic profile of the sample are found in Table 1.

Regarding sample size, we used the online calculator of Soper (2023) to estimate the minimum necessary number to test the mediation model through the Structural Equation Modeling (SEM). Taking into account that the current model encompasses three latent variables and eleven observed variables, the minimum number of participants in order to reach a level of power of .80 to detect such effects by applying the following parameters: α < .05, and strong effect size (> .5). The results indicated that the minimum recommended number would be 123 participants; therefore, the 305 participants in the current study are sufficient to carry out the planned analyses.

Table 1: Sociodemographic characteristics

Measures

New Ecological Paradigm Scale (NEP; Dunlap et al., 2000). This measure was adapted for Brazil by Pires et al. (2016), consisting of 15 items (ω = .70) that assess the degree of endorsement concerning an ecological worldview. Participants are instructed to indicate on a five-point scale (1: Strongly Disagree to 5: Strongly Agree) how much they agree with the items (e.g., “When humans interfere with nature it often produces disastrous consequences”; “Plants and animals have as much right as humans to exist”). Furthermore, two items related to attitudes towards climate change were included: “Climate change is real” and “Climate change is caused by human beings”.

Two-Dimensional MACH-IV (TDM-IV; Monaghan et al., 2016). Measure adapted for Brazil by Monteiro et al. (2022), consists of 10 items that assess both Machiavellian views (ω = .59) and tactics (ω = .74). Participants are instructed to indicate their level of agreement (1: Strongly Disagree; 5: Strongly Agree) to items such as “Anyone who completely trusts anyone else is asking for trouble” and “It is hard to get ahead without cutting corners here and there”.

Narcissistic Personality Inventory-13 (NPI-13; Gentile et al., 2013). The items of this measure were translated by Monteiro (2017), and this version of the NPI consists of 13 items (ω = .81), aiming to measure individuals' narcissism level. Participants are instructed to indicate their agreement (1: Strongly Disagree; 5: Strongly Agree) to items such as “I like to look at myself in the mirror” and “I will usually show off if I get the chance”.

Levenson Self-Report Psychopathy (Levenson et al., 1995). Measure adapted for Brazil by Hauck-Filho and Teixeira (2014), consisting of 26 items (ω = .82), which are answered on a four-point scale, with participants instructed to indicate their agreement (1: Strongly Disagree; 4: Strongly Agree) to items such as “Making a lot of money is my most important goal” and “I don’t plan anything very far in advance”.

Big Five Inventory-20 (BFI-20; Gouveia et al., 2021). This instrument consists of 20 items, aiming to capture the individual’s self-perception of the five major personality factors. In this case, participants indicated to what extent they agree (1: Totally Disagree; 5: Totally Agree) with each item describing their personality, such as “Likes to cooperate with others” (Agreeableness; ω =.70), “Can be moody” (Neuroticism; ω =.77), “Has an active imagination” (Openness; ω = .75), “Generates a lot of enthusiasm” (Extraversion; ω = .81) and “Does things efficiently” (Conscientiousness; ω = .74).

Social Dominance Orientation 7 Scale (SDO7; Ho et al., 2015). Adapted to Brazil by Vilanova et al. (2022), consisting of 16 items (ω = .89). The participants indicated their level of agreement (1: Strongly Disagree; 7: Strongly Agree) to items such as “No group should dominate in society” and “Some groups are simply inferior to others groups”.

Procedure

Data were collected through an online questionnaire using the snowball sampling procedure, and all the participants were recruited through social networks. Before completing the instruments, participants were required to read and agree to the Free and Informed Consent, in which they were informed about the study's objectives, the anonymous and voluntary nature of participation, and that they could decline the research at any time without incurring losses. Finally, the prerogatives provided for in Resolution No. 510/16 of the Brazilian National Health Council regarding regulating research with human beings were respected. The Ethics Committee of a higher education institution in the Northeast Region of Brazil approved this study (CAAE 31360920.1.0000.5181).

Data analysis

The data were analyzed using SPSS and AMOS programs. The first was used to generate descriptive (e.g., mean, standard deviation) and inferential analyses, specifically Pearson correlation analysis, to understand the general pattern of association among the variables. The second software was used to run Structural Equation Modeling (Maximum Likelihood estimator) in order to test a mediational model. To attest to the quality of the model, the following indicators of model fit to the data were followed (values for an acceptable model in parentheses, Hair et al., 2015): χ²/df, Comparative Fit Index (above .90), Tucker-Lewis Index (above .90), and Root Mean Error of Approximation (below .08).

Results

Firstly, correlations were calculated in order to investigate the general patterns of relations among the variables. Concerning the eight personality traits, only psychopathy (r = -.17; p <.01) was significantly correlated with environmentalism (i.e., the composite score of the NEP items and climate change items). Furthermore, the SDO was significantly correlated with environmentalism (moderate correlation: r = -.53; p <.001). All the results of the correlation analysis can be found in detail in Table 2.

Table 2: Relationships between environmentalism, dominance orientation, and personality

Notes: Env.: Environmentalism; SDO: Social Dominance Orientation;

M: Machiavellianism; N: Narcissism; P: Psychopathy; EX: Extraversion;

CO: Conscientiousness; AG: Agreeableness; OP: Openness; NE:

Neuroticism.

*p < .05; **p

< .001 (one-tailed).

Further, we tested the direct and indirect effects of dark personality traits and socio-ideological attitudes in predicting environmentalism (Figure 1). Considering that the three dark traits have in common a tendency towards manipulation, insensitivity and exploitative behavior, a latent variable was modeled with the three traits as observable variables, thus forming the core of the dark personality (independent variable). Thus, the dark core of personality was modeled to predict the SDO (formed by two observed variables: dominance and anti-egalitarianism facets), which in turn directly explain environmentalism (modeled by the five facets of the NEP scale and two items assessing attitudes towards climate change). It is worth noting that the FFM was considered in the current study for control purposes. As none of the personality traits of this model correlated with environmentalism, we chose not to include it in the model testing.

Using bootstraps with 5.000 resamples, direct effects of dark personality on environmentalism were initially observed (λ = -.22; 90%CI = -.33/-.10, p <.05). After inserting the SDO as a mediator, we observed indirect effects of dark traits on environmentalism (λ = -.25; 90%CI = -.36/-.17, p <.001). The mediation was full rather than partial, given that the direct effect of dark personality on environmentalism was no longer statistically significant (λ = .03, 90%CI = -.08/.16, p = .65) with the inclusion of SDO, which directly predicted the outcome (λ = .36, 90%CI =.25/.48, p < .001). Finally, the tested model showed acceptable fit indicators (χ²/df = 1.87, CFI = .95, TLI = .93, RMSEA = .054).

Figure 1: Mediation model for environmentalism

Discussion

The climate change and anti-environmental actions in Brazil are still an open question. Brazil still has little sewage treatment, and some of its rich biodiversity is seriously threatened due to human action (Feng et al., 2021; Tomas et al., 2021). It is essential to understand the social and psychological underpinnings of behavior and attitudes toward the environment to reduce environmental issues on an individual level (see Zelezny & Schulz, 2000). In the current study, we showed evidence of the direct influence of socio-ideological attitudes and the indirect effects of the dark core of personality on environmentalism.

Even though the BPF model has been extensively discussed in the literature (Hirsh & Dolderman, 2007; Milfont et al., 2012), none of these five factors were found to be relevant to environmentalism. On the other hand, in the regression model, the direct effect of the dark triad personality's core on environmentalism prediction was verified, suggesting that aversive personality traits are harmful in interpersonal relationships and person-environment relationships. Such evidence adds to previous data in the literature (Huang et al., 2018; Ucar et al., 2023; Wu et al., 2019), indicating that people with dark traits do not care about the environment, exploiting it for their own benefit without worrying about its preservation. The traits that form the dark side of the human personality have in common low levels of agreeableness (Gouveia et al., 2016) and honesty/humility (Book et al., 2015), as well as empathetic deficits (Wai & Tiliopoulos, 2012); these shared aspects are predictors of environmentalism (Hirsh & Dolderman; 2007; Milfont & Sibley, 2012, 2016).

Therefore, due to the aspects that describe the core of the dark triad of personality, it is clear that people with high levels of this set of traits cannot care about the natural environment and other animals. However, it is worth highlighting that the magnitude of the relationships between personality and environmentalism is smaller than socio-ideological attitudes due to the distal nature of personality. Thus, when SDO is included in the model, dark personality no longer directly predicts environmentalism, having indirect effects, attesting to the complete mediation of SDO, confirming the role that this variable has as a direct predictor of environmentalism, in line with previous studies (Milfont et al., 2017; Stanley et al., 2021).

As observed, it is worth noting that the SDO consisted of an underlying mechanism that enables people with a dark personality to adopt anti-environmental attitudes and behaviors. Here, dark traits are useful in contexts of scarcity and high competitiveness, enabling the individual to extract resources in restricted contexts (Jonason et al., 2019). This mechanism leads people with this personality profile to have a greater orientation towards social dominance, characterized as a socio-ideological attitude that involves perceiving the world as a competitive jungle and expressing values such as domination, power, and superiority (Duckitt, 2001; Duckitt & Sibley, 2016). This pattern of elements, in turn, results in lower levels of environmentalism, seeing nature as superior and having the right to dominate it and use it for one's own benefit (Milfont et al., 2013; Milfont & Sibley, 2014).

Thus, it is clear that the SDO would play a role as a mechanism that would enable people with dark traits to dominate nature and exploit it to obtain resources. It is also worth noting that because they see themselves as superior to nature, combined with being extremely individualistic (Paulhus & Williams, 2002), people with dark traits choose not to change their daily routine (e.g., saving water and energy, reducing the use of vehicles) in favor of the environment.

It is important to highlight some potential limitations in this study. Firstly, we relied on Brazilian convenience samples (mostly of university students), which restricted the generalizability of the current findings. Second, we did not control the effects of social desirability. For future studies, it is important to include larger and more heterogeneous samples (e.g., a more equitable distribution about education level, ethnicity, and socioeconomic class), in addition to testing the role of other aversive personality traits (e.g., sadism, greed, spitefulness) and using behavioral measures to assess pro/anti-environmental behavior. Therefore, it is clear that the possibilities for study were not exhausted here, with a broad possibility of research to predict behaviors and attitudes towards the environment and, based on the mapping of predictors, propose intervention strategies to promote environmentalism.

References:

Baldwin, M., & Lammers, J. (2016). Past-focused environmental comparisons promote proenvironmental outcomes for conservatives. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 113, 14953-14957. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1610834113

Book, A., Visser, B. A., & Volk, A. A. (2015). Unpacking “evil”: Claiming the core of the Dark Triad. Personality and Individual Differences, 73, 29-38. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.09.016

De la Ossa, C. T. A. (2021). Habilidades intelectuais e suas interfaces neurocognitivas em crianças e adolescentes expostos ao mercúrio [Unpublished Master's Thesis]. Universidade Federal de Mato Grosso.

Desrochers, J. E., Albert, G., Milfont, T. L., Kelly, B., & Arnocky, S. (2019). Does personality mediate the relationship between sex and environmentalism? Personality and Individual Differences, 147, 204-213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.04.026

Duckitt, J. (2001). A dual-process cognitive-motivational theory of ideology and prejudice. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, 33, 41-113. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0065-2601(01)80004-6

Duckitt, J., & Sibley, C. G. (2016). Personality, ideological attitudes, and group identity as predictors of political behavior in majority and minority ethnic groups. Political Psychology, 37, 109-124. https://doi.org/10.1111/pops.12222

Dunlap, R. E., Van Liere, K. D., Merting, A. G., & Jones, R. E. (2000). Measuring endorsement of the New Ecological Paradigm: A revised NEP Scale. Journal of Social Issues, 56, 425-442. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00176

Feng, X., Merow, C., Liu, Z., Park, D. S., Roehrdanz, P. R., Maitner, B., Newman, E. A., Boyle, B. L., Lien, A., Burger, J. R., Pires, M. M., Brando, P. M., Bush, M. B., McMichael, C. N. H., Neves, D. M., Nikolopoulos, E. I., Saleska, S. R., Hannah, L., Breshears, D. D., … Enquist, B. J. (2021). How deregulation, drought and increasing fire impact Amazonian biodiversity. Nature, 597(7877), 516–521. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-021-03876-7

Gentile, B., Miller, J. D., Hoffman, B. J., Reidy, D. E., Zeichner, A., & Campbell, W. K. (2013). A Test of Two Brief Measures of Grandiose Narcissism: The Narcissistic Personality Inventory-13 and the Narcissistic Personality Inventory-16. Psychological Assessment, 25, 1120-1136. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0033192

Gouveia, V. V., Monteiro, R. P., Gouveia, R. S. V., Athayde, R. A. A., & Cavalcanti, T. M. (2016). Assessing the dark side of personality: Psychometric evidences of the dark triad dirty dozen. Revista Interamericana de Psicología, 50(3), 420-432. https://doi.org/10.30849/rip/ijp.v50i3.126

Hair, J. F. Jr., Black, W. C., Babin, B. J., & Anderson, R. E. (2015). Multivariate Data Analysis (7th ed.). Prentice Hall.

Hauck-Filho, N., & Teixeira, M. A. P. (2014). Revisiting the psychometric properties of the Levenson Self-Report Psycopathy Scale. Journal of Personality Assessment, 96, 459-464. https://doi.org/10.1080/00223891.2013.865196

Hirsh, J. B., & Dolderman, D. (2007). Personality predictors of consumerism and environmentalism: A preliminary study. Personality and Individual Differences, 43, 1583-1593. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2007.04.015

Ho, A. K., Sidanius, J., Kteily, N., Sheehy-Skeffington, J., Pratto, F., Henkel, K. E., Foels, R., & Stewart, A. L. (2015). The nature of social dominance orientation: Theorizing and measuring preferences for intergroup inequality using the new SDO₇ scale. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 109(6), 1003-1028. https://doi.org/10.1037/pspi0000033

Huang, N., Zuo, S., Wang, F., Cai, P., & Wang, F. (2019). Environmental attitudes in China: The roles of the Dark Triad, future orientation and place attachment. International Journal of Psychology, 54, 563-572. http://dx.doi.org/10.1002/ijop.12518

Jonason, P. K., Okan, C., & Özsoy, E. (2019). The dark triad traits in Australia and Turkey. Personality and Individual Differences, 149, 123-127. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2019.05.058

Lee, K., Ashton, M. C., Wiltshire, J., Bourdage, J. S., Visser, B. A., & Gallucci, A. (2013). Sex, power, and money: Prediction from the Dark Triad and Honesty-Humility. European Journal of Personality, 27, 169-184. https://doi.org/10.1002/per.1860

Levenson, M. R., Kiehl, K. A., & Fitzpatrick, C. M. (1995). Assessing psychopathic attributes in a noninstitutionalized population. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 68, 151-158. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.68.1.151

Mertens, A., von Krause, M., Denk, A., & Heitz, T. (2021). Gender differences in eating behavior and environmental attitudes-The mediating role of the Dark Triad. Personality and Individual Differences, 168, 110359. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2020.110359

Milfont, T. L. (2021). Where does pro-environmental tendencies fit within a taxonomy of personality traits? In A. Frazen & S. Mader (Eds.), Handbook of Environmental Sociology (pp. 97-115). Edward Elgar Publishing.

Milfont, T. L., & Sibley, C. G. (2012). The big five personality traits and environmental engagement: Associations at the individual and societal level. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 32, 187-195. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2011.12.006

Milfont, T. L., & Sibley, C. G. (2014). The hierarchy enforcement hypothesis of environmental exploitation: A social dominance perspective. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 55, 188-193. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jesp.2014.07.006

Milfont, T. L., & Sibley, C. G. (2016). Empathic and social dominance orientations help explain gender differences in environmentalism: A one-year Bayesian mediation analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 90, 85-88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2015.10.044

Milfont, T. L., Bain, P. G., Kashima, Y., Corral-Verdugo, V., Pasquali, C., Johansson, L.-O., Guan, Y., Gouveia, V. V., Garðarsdóttir, R. B., Doron, G., Bilewicz, M., Utsugi, A., Aragones, J. I., Steg, L., Soland, M., Park, J., Otto, S., Demarque, C., Wagner, C., … Einarsdóttir, G. (2017). On the relation between social dominance orientation and environmentalism. Social Psychological and Personality Science, 9(7), 802-814. https://doi.org/10.1177/1948550617722832

Milfont, T. L., Richter, I., Sibley, C. G., Wilson, M. S., & Fischer, R. (2013). Environmental consequences of the desire to dominate and be superior. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 39, https://doi.org/1127-1138. 10.1177/0146167213490805

Monaghan, C., Bizumic, B., & Sellbom, M. (2016). The role of Machiavellian views and tactics in psychopathology. Personality and Individual Differences, 94, 72-81. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2016.01.002

Monteiro, R. P. (2017). Tríade sombria da personalidade: conceitos, medição e correlatos [Doctoral Dissertation]. Universidade Federal da Paraíba.

Monteiro, R. P., Coelho, G. L. H., Cavalcanti, T. M., Grangeiro, A. S. M., & Gouveia, V. V. (2022). The ends justify the means? Psychometric parameters of the MACH-IV, the two-dimensional MACH-IV and the trimmed MACH in Brazil. Current Psychology, 41, 4088-4098. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00892-0

Palinkas, L. A., & Wong, M. (2020). Global climate change and mental health. Current Opinion in Psychology, 32, 12-16. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.copsyc.2019.06.023

Paulhus, D. L., & Williams, K. M. (2002). The Dark Triad of personality: narcissism, machiavellianism, and psychopathy. Journal of Research in Personality, 36, 556-563. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0092-6566(02)00505-6

Perry, R., & Sibley, C. G. (2012). Big-Five personality prospectively predicts social dominance orientation and right-wing authoritarianism. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(1), 3-8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.08.009

Pires, P., Ribas Junior, R. C., Hora, G., Filgueiras, A. & Lopes, D. (2016). Psychometric properties for the Brazilian version of the New Ecological Paradigm revised. Temas em Psicologia, 24, 1407-1419. https://dx.doi.org/10.9788/TP2016.4-12

Rocha, L. R. L. (2016). A correlação entre doenças respiratórias e o incremento das queimadas em Alta Floresta e Peixoto de Azevedo norte do Mato Grosso-Amazônia Legal. Revista Brasileira de Políticas Públicas, 6, 246-254. https://doi.org/10.5102/rbpp.v6i1.3484

Soper, D. (2023, outubro 12). Free Statistics Calculators (version 4.0). Statistics Calculators. https://www.danielsoper.com/statcalc/calculator.aspx?id=89

Stanley, S. K., Wilson, M. S., & Milfont, T. L. (2021). Social dominance as an ideological barrier to environmental engagement: Qualitative and quantitative insights. Global Environmental Change, 67, 102223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2021.102223

Tomas, W. M., Berlinck, C. N., Chiaravalloti, R. M., Faggioni, G. P., Strüssmann, C., Libonati, R., Abrahão, C. R., do Valle Alvarenga, G., de Faria Bacellar, A. E., de Queiroz Batista, F. R., Bornato, T. S., Camilo, A. R., Castedo, J., Fernando, A. M. E., de Freitas, G. O., Garcia, C. M., Gonçalves, H. S., de Freitas Guilherme, M. B., Layme, V. M. G., … Morato, R. (2021). Distance sampling surveys reveal 17 million vertebrates directly killed by the 2020’s wildfires in the Pantanal, Brazil. Scientific Reports, 11(1). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41598-021-02844-5

Ucar, G. K., Malatyalı, M. K., Planalı, G. Ö., & Kanik, B. (2023). Personality and pro-environmental engagements: the role of the Dark Triad, the Light Triad, and value orientations. Personality and Individual Differences, 203, 112036. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2022.112036

Veloso Gouveia, V., de Carvalho Rodrigues Araújo, R., Vasconcelos de Oliveira, I. C., Pereira Gonçalves, M., Milfont, T., Lins de Holanda Coelho, G., Santos, W., De Medeiros, E. D., Silva Soares, A. K., Pereira Monteiro, R., Moura de Andrade, J., Medeiros Cavalcanti, T., Da Silva Nascimento, B., & Gouveia, R. (2021). A short version of the Big Five Inventory (BFI-20): evidence on construct validity. Revista Interamericana de Psicología/Interamerican Journal of Psychology, 55(1), e1312. https://doi.org/10.30849/ripijp.v55i1.1312

Vilanova, F., Soares, D., de Quadros Duarte, M., & Costa, Â. B. (2022). Evidências de Validade da Escala de Orientação à Dominância Social no Brasil. Psico-USF, 27(3). https://doi.org/10.1590/1413-82712024270303

Wai, M., & Tiliopoulos, N. (2012). The affective and cognitive empathic nature of the dark triad of personality. Personality and Individual Differences, 52, 794-799. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2012.01.008

Wu, W., Wang, H., Lee, H.-Y., Lin, Y.-T., & Guo, F. (2019). How Machiavellianism, psychopathy, and narcissism affect sustainable entrepreneurial orientation: The moderating effect of psychological resilience. Frontiers in Psychology, 10, 779. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2019.00779

Zelezny, L. C., & Schultz, P. W. (2000). Psychology of promoting environmentalism: promoting environmentalism. Journal of Social Issues, 56(3), 365-371. https://doi.org/10.1111/0022-4537.00172

Data availability: The dataset supporting the results of this study is not available.

How to cite: Monteiro, R. P., da Cunha, L. Q., Loureto, G. D. L., Araújo, I. C. H., & Pimentel, C. E. (2023). The core of the dark triad predict environmentalism through social dominance orientation. Ciencias Psicológicas, 17(2), e-2891. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i2.2891

Authors’ participation: a) Conception and design of the work; b) Data acquisition; c) Analysis and interpretation of data; d) Writing of the manuscript; e) Critical review of the manuscript.

R. P. M. has contributed in a, b, c, d, e; L. C. Q. in a, b, d, e; G. D. L. L. in a, b, d, e; I. C. H. A. in a, b, d, e; C. E. P. in c, d, e.

Scientific editor in-charge: Dra. Cecilia Cracco.