10.22235/cp.v17i1.2872

Propiedades psicométricas del Cuestionario Revisado de Bullying/Victimización de Olweus para Niños en español

Psychometric properties of the Revised Olweus Bully/Bullied Questionnaire for Children in Spanish

Propriedades psicométricas do Questionário Revisado de Bullying/Vitimização de Olweus para Crianças em español

Santiago Resett1, ORCID 0000-0001-7337-0617

Lucas Marcelo Rodríguez2, ORCID 0000-0001-5525-1155

José Eduardo Moreno3, ORCID 0000-0002-9613-0664

1 Universidad Argentina de la Empresa, Conicet, Argentina, [email protected]

2 Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina, Conicet, Argentina

3 Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina, Conicet, Argentina

Resumen:

El bullying es un importante factor de riesgo para la salud mental de niños y adolescentes, ya que las víctimas presentan mayores niveles de problemas emocionales; mientras que los acosadores muestran mayores problemas de conducta. A pesar de su relevancia, existen pocos instrumentos para su medición en niños de edad escolar. El presente estudio buscó evaluar las propiedades psicométricas del Cuestionario Revisado de Bullying/Victimización de Olweus en una muestra de habla hispana, con la particularidad de ser el primer análisis de habla hispana en niños. Se realizó un estudio instrumental, implementando AFE, AFC y correlaciones de Pearson. Una muestra intencional de 670 niños argentinos, varones (48 %) y mujeres (52 %), de 10 a 12 años (edad media = 10.80; DE = .72) contestaron el cuestionario, la Escala de Calidad de la Amistad y el Inventario de Depresión de Kovacs. Los resultados indicaron una estructura factorial de dos dimensiones: victimización y bullying, que coincidieron con las postuladas por el autor del cuestionario. Los valores de los coeficientes alfas de Cronbach y de omega de McDonald fueron satisfactorios. Se confirmó la evidencia de validez concurrente con la percepción de la calidad de la amistad y la depresión. El cuestionario presentó adecuadas propiedades psicométricas en su adaptación al español argentino.

Palabras clave: acoso escolar; niños; propiedades psicométricas; bullying; victimización.

Abstract:

Bullying is an important risk factor for the mental health of children and adolescents, since victims’ present higher levels of emotional problems while those who carry it out show greater behavioural problems. Despite its relevance, few instruments exist for its measurement in school-age children. The present study sought to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire in a Spanish-speaking sample, with the particularity of being the first analysis of Spanish-speaking children. A quantitative study was carried out, implementing AFE, AFC, and Spearman's correlations. An intentional sample of 670 Argentinian children, male (48 %) and female (52 %), from 10 to 12 years old (mean age= 10.80; SD = 0.72) answered this test, such as the Friendship Quality Scale and the Kovacs Depression Inventory. The results indicated a factorial structure of two dimensions called victimization and bullying that coincided with those postulated by the author of the questionnaire. Cronbach's and Omega's alphas were satisfactory. The evidence of concurrent validity with the perception of the quality of friendship and depression was confirmed. The results indicated that this questionnaire presented adequate psychometric properties in its adaptation to Argentinian Spanish.

Keywords: bullying; children; psychometric properties; bully; bullied.

Resumo:

O bullying é um importante fator de risco para a saúde mental de crianças e adolescentes, uma vez que as vítimas apresentam maiores níveis de problemas emocionais enquanto aqueles que o praticam apresentam maiores problemas comportamentais. Apesar de sua relevância, existem poucos instrumentos para sua mensuração em crianças em idade escolar. O presente estudo procurou avaliar as propriedades psicométricas do Questionário Revisado de Bullying/ Vitimização de Olweus em uma amostra de língua espanhol, com a particularidade de ser a primeira análise em língua espanhola em crianças. Foi realizado um estudo instrumental, implementando AFE, AFC e correlações de Pearson. Uma amostra intencional de 670 crianças argentinas, meninos (48 %) e meninas (52 %), com idades de 10 a 12 anos (média de idade = 10,80; DP = 0,72) responderam ao questionário, a Escala de Qualidade da Amizade e o Inventário de Depressão de Kovacs. Os resultados indicaram uma estrutura fatorial de duas dimensões denominadas vitimização e bullying, que coincidiram com as postuladas pelo autor do questionário. Os valores dos coeficientes alfas de Cronbach e Omega de McDonald foram satisfatórios. Foi confirmada a evidência de validade concorrente com a qualidade percebida da amizade e a depressão. O questionário apresentou propriedades psicométricas adequadas em sua adaptação ao espanhol argentino.

Palavras-chave: assédio escolar; crianças; propriedades psicométricas; bullying; vitimização.

Recibido: 4/5/2022

Aceptado: 24/3/2023

El bullying puede ser llevado a cabo de distintas formas: verbales (poner apodos, burlas, insultos, etc.), físicas (golpes, patadas, empujones, etc.) e indirectamente, esto es, sin usar contacto físico o verbal directo con la víctima (Resett, 2021; Rigby et al., 2004), por ejemplo, esparcir rumores o excluir.

Tanto el ser víctima del acoso escolar como el llevarlo a cabo son factores de riesgo para la psicopatología del desarrollo (Espelage & Swearer, 2003; Nansel et al., 2004). Las víctimas generalmente presentan mayores niveles de problemas emocionales, como depresión, ansiedad, baja autoestima (Olweus, 2013; Roh et al., 2015) e ideación suicida (Quintero-Jurado et al., 2021); mientras que los acosadores presentan un patrón de problemas de conducta, tales como conducta antisocial, consumo de sustancias tóxicas, entre otros (Farrington & Ttofi, 2011; Nansel et al., 2004). Las víctimas serían propensas a sufrir problemas internalizantes; y los agresores serían propensos a sufrir problemáticas externalizantes (Olweus, 1993, 2013). Según el modelo de problemáticas internalizantes y externalizantes, las primeras afectan el mundo interno de la persona, con un modo desadaptativo de resolver conflictos, siendo esta resolución de nivel interno como angustia, depresión, ideación suicida, etc. Por su parte, las segundas afectarían el mundo externo de la persona, con expresión de conflictos emocionales hacia afuera, con descarga impulsiva y exteriorización de la agresión (Achenbach, 2008; Arnett, 2020; Caballero et al., 2018; Luk et al., 2016; Steinberg, 2018). Un metaanálisis a partir de 18 estudios con escolares detectó la asociación entre la victimización con los problemas emocionales, de conducta e interpersonales. Por otro lado, se reporta una asociación entre el bullying y los problemas externalizantes, los interpersonales y un pobre rendimiento escolar (Kljakovic & Hunt, 2016).

En general, las víctimas y los agresores tienen mayor riesgo de presentar un peor ajuste psicosocial. Estudios previos muestran que niveles de calidad de amistad en niños y adolescentes se relacionan negativamente con ser víctima o victimario de bullying (Rodriguez et al., 2015; Rodriguez et al, 2021). Debido a que tanto las víctimas como quienes llevan a cabo el acoso presentan este mayor riesgo, es vital desarrollar, emplear y adaptar instrumentos con sólidas bondades psicométricas para identificarlos. Existen numerosas técnicas para medir este problema: observaciones estructuradas, entrevistas, nominaciones de docentes y alumnos, autoinformes, entre otras (Hartung et al., 2011). Los autoinformes presentan la ventaja de que son técnicas de fácil aplicación, interpretación, con bajos costos económicos y que pueden aplicarse en múltiples ocasiones para ver cómo evoluciona el fenómeno. Si bien existen numerosas escalas de medición de bullying, no todas tienen una definición exacta del mismo o presentan sus particularidades, como el desequilibrio de poder, repetición, entre otros (Vivolo-Kantor et al., 2014).

El Cuestionario Revisado de Bullying/Victimización (The Revised Olweus Bully/Bullied Questionnaire; Olweus, 1996) para niños y adolescentes es uno de los instrumentos utilizados en el mundo para medir esta problemática (Cornell & Bandyopadhyay, 2010). Según Olweus (1993), las ventajas de este cuestionario son: brindar a los estudiantes una clara definición sobre qué se entiende por acoso, preguntar sobre el acoso ocurrido en los últimos meses y presentar una frecuencia temporal de respuesta. Las dos principales dimensiones que mide el cuestionario son: realizar el bullying y ser victimizado (Olweus, 1994). Este cuestionario ha sido empleado en numerosos estudios de distintos países y las virtudes psicométricas del mismo fueron sólidamente comprobadas, tanto con respecto a su consistencia interna, con alfas de Cronbach muy aceptables y fluctuando entre .80 a .90 en numerosos estudios extranjeros tanto para la dimensión victimización como para la de bullying (Olweus, 2013), como en lo referente a su validez y a la propiedad de diferenciar entre los estudiantes involucrados en la agresión y en el ser victimizados (Solberg & Olweus, 2003). Se adaptó y tradujo en numerosos países, como Países Bajos, Japón, Estados Unidos, entre otros (Cornell & Bandyopadhyay, 2010; Gaete et al., 2021; Kyriakides et al., 2006; Lee & Cornell, 2009; Resett, 2018). Las investigaciones del autor del test indicaron que presenta una adecuada confiabilidad (Olweus, 2013). Con respecto a su validez concurrente, se demostró una asociación lineal de la victimización con los problemas emocionales (depresión, ansiedad y baja autoestima) y de los acosadores con los problemas de conducta (conducta antisocial, agresividad y consumo de sustancias tóxicas) (Olweus, 2013; Resett, 2018).

Si bien el bullying adquiere mayor prevalencia en los años adolescentes, es de crucial importancia identificar a las potenciales víctimas y agresores tempranamente, ya que en la adolescencia las intervenciones para prevenir y disminuir el acoso son menos efectivas que en la niñez (Resett & Mesurado, 2021). Además, si bien los estudios empíricos son más escasos en la niñez que en la adolescencia, reportan niveles similares de prevalencia de ser victimizado y realizar el bullying en ambas etapas de ciclo vital. A nivel global, se señala que uno de cada tres niños sufrió de bullying en los últimos 30 días (Armitage, 2021). Un estudio con niños y adolescentes en 16 países de la América Latina encontró que Argentina era el país que ostentaba los niveles más elevados de acoso físico (Román & Murillo, 2011). En la Argentina, específicamente, se halló un 13 % de víctimas, 10 % de acosadores y 5 % de ambos en muestras infantiles (Resett, 2021). Investigaciones en España hallaron un 9 % de víctimas, 1 % de acosadores y 1 % de ambos grupos en muestran infantiles (Babarro et al., 2020). Aunque las propiedades psicométricas de dicho cuestionario se examinaron en muestras de adolescentes argentinos e indicaron adecuada estructura factorial, consistencia interna y validez concurrente (Resett, 2011, 2018), no existen estudios de habla hispana que hayan examinado sus propiedades en muestras de niños de edad escolar.

En la Argentina, como en tantos otros países de la región, la mayoría de los estudios que se han llevado a cabo sobre bullying son de naturaleza teórica y existen escasos datos científico-empíricos a este respecto y, menos aún, con instrumentos de reconocidas propiedades psicométricas. A pesar de este hecho, en los últimos años se han realizado investigaciones en adolescentes (Gaete et al., 2021; Resett, 2011, 2018) y niños (Gaete et al., 2021; Resett, 2021).

En este contexto, es de vital importancia examinar en un país latinoamericano y de una tradición cultural diferente al de las naciones nórdicas y de Estados Unidos las propiedades psicométricas del instrumento desarrollado por Olweus. De este modo, la fortaleza del presente estudio es ser el primero en evaluar las propiedades psicométricas en una muestra de niños de habla hispana. Al ser el cuestionario de Olweus un instrumento muy utilizado a nivel mundial, su adaptación permitirá una comparación de los niveles del bullying reportado a nivel internacional y una pronta identificación de la problemática.

Objetivos

Explorar evidencias de estructura factorial del Cuestionario Revisado de Bullying/Victimización de Olweus en niños y la consistencia interna de dicho cuestionario. Examinar evidencia de validez concurrente con respecto a la sintomatología depresiva y la calidad de la amistad.

Método

Participantes

Participaron en esta investigación 670 niños seleccionados de modo no probabilístico, 48 % de sexo masculino y 52 % de sexo femenino, con edades entre 10 y 12 años (M = 10.80; DE = 0.72) de nivel socioeconómico medio. Los mismos pertenecen a 7 escuelas de nivel primario de gestión privada (5 escuelas) y pública (2 escuelas), de la ciudad de Paraná, provincia de Entre Ríos, Argentina, que cursaban quinto y sexto grado de dicho nivel educativo. El criterio de inclusión era tener entre 10 y 12 años, residir en Paraná, asistir a la escolaridad primaria en nivel privado o público y cursar quinto o sexto grado.

Instrumentos

Acoso y victimización. Cuestionario Revisado de Bullying/Victimización de Olweus (1996). Consiste de 38 preguntas para medir los problemas con relación al bullying en niños y adolescentes. En primer lugar, este instrumento da una definición a los estudiantes sobre el bullying, ya que este puede ser confundido por los alumnos con otros tipos de conflicto entre pares (Phillips & Cornell, 2012). Luego viene la pregunta global sobre si se fue victimizado —en otra sección del cuestionario se inquiere sobre si se acosó a otros alumnos—: “Desde que empezaron las clases ¿cuántas veces fuiste acosado en la escuela?”. Para hacer la medición más precisa y sensible al cambio, el cuestionario pregunta sobre estos comportamientos en los últimos meses. A continuación los alumnos son interrogados sobre los distintos tipos de acoso que experimentaron —o que llevaron a cabo en la otra parte del cuestionario—, a partir de nueve preguntas sobre la frecuencia de las distintas formas de acosar: golpear, sacar o romper cosas, poner sobrenombres, burlas sobre el aspecto físico, burlas sexuales, amenazar, excluir, mentir, acosar por SMS o internet u otras formas de acoso; esto es, físico (dos preguntas), verbal (cuatro), indirecta o relacional (dos) y ciberbullying [ciberacoso] (una). Las nueve preguntas sobre ser acosado y acosar pueden sumarse o promediarse para confeccionar un puntaje global, ya que constituyen las dos grandes dimensiones evaluadas por este cuestionario (Kyriakides et al., 2006; Olweus, 1994, 2013). Ejemplos de ítems son: “Me pusieron sobrenombres feos, me hicieron cargadas pesadas, o se burlaron de mí” (ser victimizado). El cuestionario emplea las siguientes alternativas de respuesta: nunca, una o dos veces, dos o tres veces al mes, más o menos una vez por semana y varias veces por semana. Las respuestas son codificadas generalmente como 0 (nunca) a 4 (varias veces por semana).

En el presente estudio se tomó la versión en español empleada por estudios anteriores en adolescentes argentinos que demostró buenas propiedades psicométricas, como validez de constructo, confiabilidad interna y validez concurrente (Resett, 2011, 2018). El autor del test señala que la versión en español usada en adolescentes se puede aplicar en niños mayores de 10 años (Olweus, 1996). La versión en español argentino y la original es similar con la única diferencia de que la primera en el ítem de bullying verbal por la raza o etnia fue cambiada por “color de piel”, ya que en su proceso de traducción y adaptación jueces independiente sugirieron dicho cambio para su validez ecológica (Resett, 2018). Dicha cuestión es lo novedoso del presente estudio, dado que se evalúan las propiedades psicométricas en una muestra de niños y los restantes estudios en el país fueron en muestras de adolescentes. Este trabajo solamente informar sobre las preguntas de las escalas de victimización y bullying, los restantes ítems no forman parte de estas.

Escala de Calidad de la Amistad para Niños (Resett et al., 2013; Rodriguez et al., 2015), versión en español de la Friendship Qualities Scale version 4.1 de Bukowski et al. (1994). Los niños deben mencionar el nombre de su mejor amigo, el género y si asiste al mismo curso, y luego contestar 33 ítems que describen cualidades de la amistad, indicando el grado de acuerdo con estas. Este cuestionario comprende 6 subescalas o dimensiones de la amistad: compañerismo, cantidad de tiempo voluntario que los amigos comparten o pasan juntos; balance, balance en la reciprocidad, si en el vínculo de amistad uno de los sujetos se brinda más que el otro; conflicto, peleas o discusiones dentro de la relación de amistad, los desacuerdos en la misma; ayuda, ayuda mutua y la asistencia, así como la ayuda frente a situaciones conflictivas que pueden vivirse con otros compañeros; seguridad, creencia de que en el momento en que lo necesite el amigo es fiable y puede tener confianza en él (alianza confiable); y proximidad, sentimientos de afecto o sentirse especial dentro del vínculo de amistad el uno con el otro, así como la unión del vínculo. El cuestionario presenta 4 alternativas de respuesta: 1 (totalmente en desacuerdo) hasta 4 (totalmente de acuerdo). Con relación a los estudios psicométricos preliminares en la Argentina, la Escala de Calidad de la Amistad ha mostrado índices de confiabilidad interna aceptables para cada una de sus subescalas, con los siguientes coeficientes alfa de Cronbach: compañerismo (.61), ayuda (.80), seguridad (.70), proximidad (.81), conflicto (.80) y balance (.65). La versión final comprende 7 ítems de la dimensión proximidad, 6 ítems de conflicto, 3 ítems de balance, 5 ítems de compañerismo, 7 ítems de ayuda y 5 ítems de seguridad. Presenta buenas propiedades psicométricas en español, como consistencia interna (Rodriguez et al., 2015) y validez concurrente con las relaciones familiares (Rodriguez et al., 2021). En el presente estudio las alfas de Cronbach fueron adecuadas con .82 para proximidad; .68 para conflicto; .61 para balance; .81 para ayuda; .65 para compañerismo y .58 para seguridad.

Inventario de Depresión para Niños de Kovacs (1992). Este cuestionario mide el síndrome depresivo en niños y adolescentes de 7 a 17 años. Consta de 27 ítems de 3 alternativas cada uno. Puntajes más altos implican mayor depresión. Sus virtudes psicométricas están bien establecidas en muestras argentinas, con valores de consistencia interna alrededor de .84 y validez concurrente con las relaciones interpersonales y los problemas de conducta (Facio et al., 2006). El alfa de Cronbach de dicho inventario fue de .83 en la presente muestra.

Procedimiento

En primer lugar se contactó a los directores de las escuelas con el fin de solicitar la autorización. Una vez lograda la autorización de los directivos, se mandó una nota en el cuaderno de comunicaciones de los alumnos con el fin de pedir la autorización parental. Se aseguró el anonimato, la confidencialidad y la participación voluntaria.

La recolección de los datos se realizó en horario de clases, dentro de las aulas y a nivel grupal, con autoinformes presentados en formato papel. Durante la administración siempre estuvieron presentes dos investigadores del proyecto para ayudar a los niños en el caso en que se presentara alguna dificultad para la comprensión de las consignas.

El proyecto fue aprobado por un comité de la universidad que financió la investigación.

Análisis de datos

Los datos se analizaron en el programa Paquete Estadísticos para las Ciencias Sociales SPSS versión 23 para sacar estadísticos descriptivos (porcentajes, medias, desvíos, etc.) e inferenciales (alfas de Cronbach, correlaciones de Spearman, etc.). Se realizaron análisis paramétricos; los valores de la escala de bullying presentaron asimetría de 1.71 a 4.75 y curtosis de 2.08 a 7.18. Valores mayores a 3 para los primeros y mayores a 8 para los segundos son considerados extremos (Boomsma & Hoogland, 2001), mientras que otros autores postulan valores de 10 o más como extremos (Kline, 2015; Weston & Gore, 2006). Aunque el formato de respuestas es ordinal, como en muchos otros tests psicológicos, su distribución amerita que se traten los datos de forma continua como indican otras investigaciones (Schmidt et al., 2008) y como se hizo en muestras adolescentes con dicho instrumento (Resett, 2011, 2018). Para las restantes variables los valores eran 0.08 y 2.45 y 0.05 y 6.00, respectivamente.

En primer lugar se dividió aleatoriamente la muestra en dos grupos de 300 y 370, respectivamente. Con el primer grupo se llevó a cabo un análisis factorial exploratorio (estudio de calibración) con el método de máxima verosimilitud pidiendo autovalores mayores a 1 y con rotación oblimin —para factores relacionados—, debido a que el análisis de componentes principales se desaconseja en la actualidad (Lloret-Segura et al., 2014). Para determinar la retención de factores, se empleó el método de implementación clásico de Horn (1965). Para la retención, se compararon los autovalores empíricos con los autovalores (medias) aleatorios, luego se seleccionaron los que se encontraban por encima de la media aleatoria (O'Connor, 2000). Se usó un número de replicaciones igual a 100 y percentil de representación de simulaciones igual a .95.

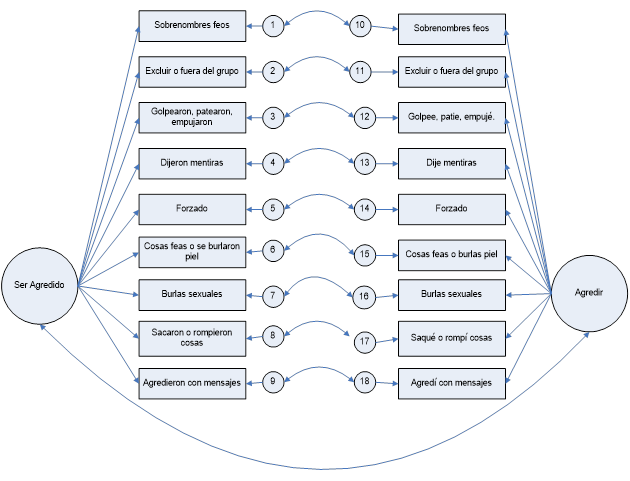

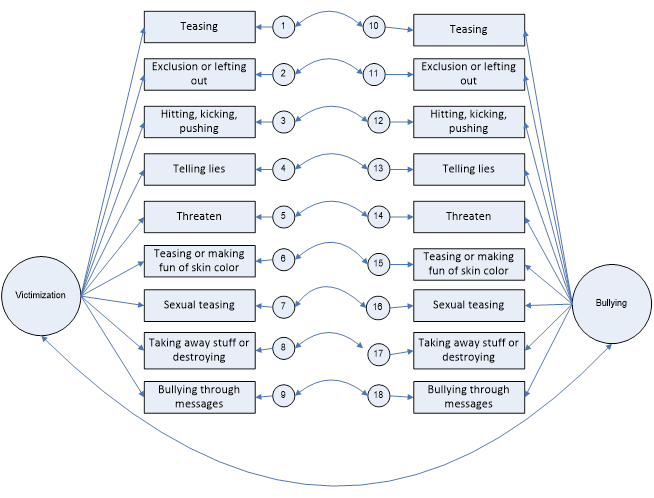

Con la segunda muestra se llevó a cabo un análisis factorial confirmatorio (estudio de replicación) con el programa MPLUS versión 6 para poner a prueba el modelo de dos factores postulados por el autor del test (Olweus, 2013; Solberg & Olweus, 2003) y también comprobado en estudios del cuestionario en adolescentes (Resett, 2018), como se muestra en la Figura 1. Se optó por este enfoque basados en los datos —primero un análisis exploratorio y luego un confirmatorio—, porque las estructuras factoriales de un instrumento pueden variar de un estudio a otro o cuando se está en un proceso de adaptación de un test (Fehm & Hoyer, 2004; Wells & Davies, 1994). Si en el análisis factorial emergía un modelo diferente, este se pondría a prueba también para comparar su ajuste. También se puso a prueba uno de dos factores independientes o no relacionados. Se empleó el método Weighted Least Squares (WLSMV) debido a que las respuestas de los ítems eran ordinales con cinco opciones de respuestas, como se sugiere (Brown, 2006; Li, 2016; Lloret-Segura et al., 2014).

Figura 1: Modelo a poner a prueba del Cuestionario de Agresores-Víctimas de Olweus para niños

Para considerar si el modelo era aceptable, se tuvieron en cuenta el Índice Comparativo de Ajuste (CFI), el Tucker-Lewis Índex (TLI) y el promedio de los residuales estandarizados al cuadrado (RMSEA), ya que el estadístico c2 es muy sensible al tamaño de la muestra (Byrne, 2010, 2012). Se consideran valores de CFI y TLI por encima de .90 y RMSEA por debajo de .10 como adecuados (Bentler, 1992; Byrne, 2010). También hay criterios más exigentes con más de .95 y menos de .05, respectivamente (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

Para el análisis de consistencia interna, además del alfa de Cronbach, se usó el omega, debido a la naturaleza categórica de las alternativas que se extrajo con el programa Jamovi 2.2.5.

Resultados

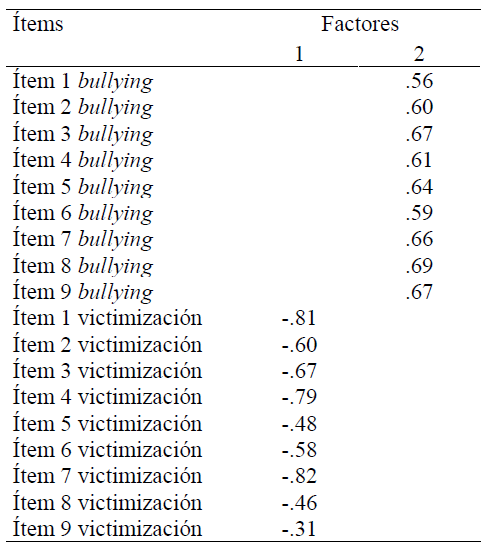

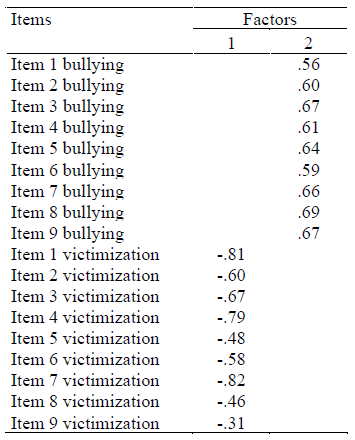

Para evaluar la estructura factorial del cuestionario de Olweus para niños, primeramente se llevó a cabo un análisis factorial exploratorio. El índice KMO = .88; c2(153) = 4046,04; p < .001 indicaba que era apropiado llevarlo a cabo. En la Tabla 1 se presentan los resultados del análisis. Como se muestra, emergen dos factores: uno se denomina victimización y el otro bullying. Al comparar los autovalores empíricos con los autovalores (medias) aleatorios, el análisis mostró que era indicado retener dos que eran los que puntuaban por encima de los autovalores aleatorios, ya que los dos primeros valores empíricos eran 5.83 2.04 y los aleatorios puntuaban 1.29 y 1.23, con los restantes valores del análisis empírico hallándose por debajo. Todos los ítems cargaron en su respectiva dimensión sin cargas cruzadas mayores a .30. Como se muestra en la Tabla 1, emergieron dos factores que explicaban una varianza de 23 % y 19 %, respectivamente.

Tabla 1: Cargas factoriales para el análisis factorial exploratorio del cuestionario de Olweus en niños

Nota. Solamente se presentan las cargas superiores a .30.

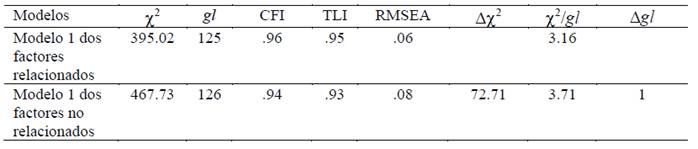

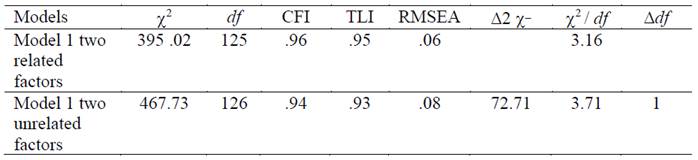

A continuación, se llevó a cabo el análisis factorial confirmatorio. También se puso a prueba un modelo de dos factores no asociados (Tabla 2). El modelo de dos factores asociados arrojó un ajuste más adecuado que el de dos factores no relacionados, como lo indican valores más elevados de CFI, TLI y RMSEA menores, respectivamente.

Tabla 2: Índice de ajuste de los modelos del cuestionario de Olweus en niños

Nota. gl: grados de libertad; CFI: Índice de Corrección Comparativa; TLI: Índice de Tucker-Lewis; RMSEA: raíz del residuo cuadrático promedio; SRMR: residuales estandarizados al cuadrado; c2/gl valor de c2 dividido por los grados de libertad; ∆c2 diferencia de c2 entre los modelos; ∆gl diferencia entre los grados de libertad de los modelos.

Las cargas factoriales del modelo de dos factores relacionados eran todas significativas y se hallaban entre .41 y .94. La correlación entre ambas dimensiones fue .43; p < .001. El alfa de Cronbach fue de .74 para la escala de ser victimizado y de .81 para la de bullying. El coeficiente de omega fue de .75 y .83, respectivamente.

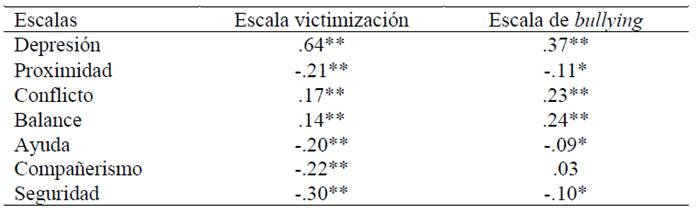

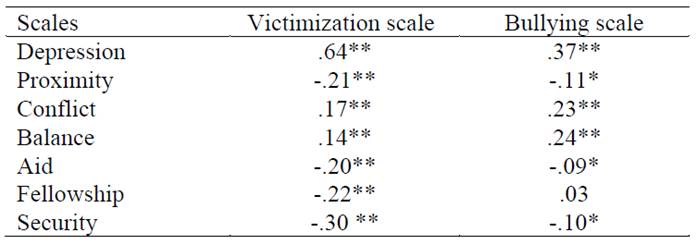

Para observar la validez concurrente de la escala victimización y bullying, se llevaron a cabo correlaciones de Spearman entre éstas y la escala de depresión de Kovacs y las escalas de amistad de Bukowski et al. (Tabla 3).

Tabla 3: Correlaciones de Spearman entre las escalas de victimización y bullying de Olweus, la escala de depresión y la escala de amistad

* p < .05 ** p < .01

Como se muestra en la Tabla 3, tanto la escala de victimización y bullying correlacionaba significativamente con los puntajes de depresión; la escala de victimización correlacionaba negativamente con proximidad, ayuda, compañerismo y seguridad y positivamente con conflicto y balance. La escala de bullying se asociaba positivamente con los puntajes de conflicto y balance, mientras que lo hacía negativamente con proximidad, ayuda y seguridad.

Discusión

La importancia de esta investigación radica en evaluar por primera vez la estructura factorial del cuestionario de Olweus en una muestra de niños de Argentina para medir un fenómeno de gran actualidad y de una notable relevancia psicológica, como lo es el bullying. Las propiedades psicométricas del test fueron evaluadas en adolescentes argentinos, pero no en niños, por este motivo la investigación reviste gran relevancia.

Con respecto al análisis factorial exploratorio, los resultados arrojaron un modelo de dos factores relacionados que podían ser denominado victimización y llevar a cabo el bullying, sin cargas cruzadas y cargando todas en su respectivo factor. Esto puede deberse a su infrecuencia en la presente muestra. Estas dos dimensiones son las postuladas por el autor del test (Olweus, 1996, 2013) y los dos factores medidos por el test. Estos resultados también coinciden con estudios en adolescentes de Argentina (Resett, 2011, 2018). Las dos dimensiones mencionadas demostraron su asociación con los problemas internalizantes y externalizantes en numerosos estudios (Olweus, 2013; Resett, 2018).

En lo referente al análisis factorial confirmatorio, el modelo de medición de dos factores relacionadas —ser victimizado y realizar bullying— también mostró un ajuste adecuado con CFI mayor a .90 y SRMR, menor a .08, simultáneamente (Bentler, 1992). También el ajuste fue cercano a criterios estadísticos de CFI y SRMR mayores a .95 y menores a .05, respectivamente (Hu & Bentler, 1999). Este modelo fue mucho más adecuado que un modelo de dos factores con las dos dimensiones no asociadas. De este modo, los resultados sugerirían que también en la Argentina para los niños escolarizados dicho instrumento tiene una estructura factorial similar a la detectada en países anglosajones y europeos: una dimensión de victimización y otra de llevar a cabo el bullying (Olweus, 1994, 1996). Estudios extranjeros (Hartung et al., 2011; Kyriakides et al., 2006) arribaron a las mismas conclusiones, lo cual brinda cierta evidencia de la solidez psicométrica del instrumento al mantener su estructura factorial en muestras de distintas culturas, especialmente teniendo en cuenta que Argentina es una nación latina, con un menor desarrollo social y económico, y culturalmente distinta a las naciones anglosajonas y nórdicas.

Las consistencias internas (alfa de Cronbach de .74 para la victimización y de .81 para bullying, coeficiente de Omega con .75 y .83 respectivamente) fueron adecuadas (DeVellis, 2012; Kaplan & Saccuzzo, 2006). Estos resultados fueron similares a los aportados por diferentes estudios de distintos países de Europa y Estados Unidos (Hartung et al., 2011; Kyriakides et al., 2006), los cuales hallaron, con alfas de Cronbach o teorías de la respuesta al ítem, unos coeficientes de entre .80-.90. Del mismo modo, estudios recientes de Olweus en grandes muestras noruegas de casi 50.000 alumnos encontraron valores semejantes (Breivik & Olweus, 2012).

En lo relativo a la validez concurrente de ambas escalas, se detectó que la escala de victimización y de bullying correlacionaban significativamente con los puntajes de depresión. Está bien establecido que las víctimas de bullying presentan más depresión y dicha sintomatología es una de las más asociadas a este problema (Olweus, 2013; Resett, 2018). Algunos estudios indican que los acosadores también pueden sufrir más depresión (Luk et al., 2016). Un posible mecanismo es que sus problemas de conductas o externalizantes con el tiempo podrían llevarlos también a tener problemas internalizantes mediante un efecto “cascada”, esto es, el fallo en una tarea del desarrollo (relaciones saludables con los pares) puede conllevar a otra dificultad (los problemas internalizantes), como sugieren muchos académicos (por ejemplo, Masten & Cicchetti, 2010).

Por otra parte, la escala de victimización correlacionó negativamente con proximidad, ayuda, compañerismo y seguridad, y positivamente con conflicto y balance con respecto a la calidad de la amistad. La escala de bullying se asoció positivamente con los puntajes de conflicto y balance. Está bien establecido que tanto las víctimas como quienes hacen bullying presentan una mayor dificultad con los pares y carecen de habilidades sociales (Olweus, 1996). La competencia social de las víctimas se ve afectada por ser sujetos tímidos o inhibidos, mientras que la de los agresores se ve deteriorada por su patrón externalizante, dominante y agresivo. Sin embargo, la competencia social en el área amistosa de las víctimas era peor que quienes lo realizan, lo cual coincide con otros estudios que indicaron que los correlatos psicosociales de las víctimas es peor que el de los agresores (Book et al., 2012) Está establecido que quienes llevan a cabo el bullying no son sujetos solitarios, sino que pueden tener amigos y afiliarse con pares antisociales que, a su vez, refuerzan su agresión (Olweus, 1993). Incluso algunos estudios señalan que quienes hacen bullying evalúan su calidad de la amistad íntima tan satisfactoriamente como la de los alumnos no involucrados en el bullying y más elevada que la de las víctimas (Resett et al., 2014).

En Argentina se han realizado estudios de comportamiento agresivos evaluando su relación con habilidades sociales en adolescentes, los cuales han mostrado una relación significativa entre el comportamiento agresivo y el déficit en las habilidades sociales. Se evaluaron correlaciones negativas entre la agresividad y la consideración de los demás, así como correlaciones negativas entre el autocontrol y el retraimiento (Caballero et al., 2018). Teniendo en cuenta que el bullying es un comportamiento agresivo específico, y que las habilidades sociales son fundamentales para las relaciones de pares (Contini, 2015) y puntualmente para las relaciones de amistad, estos hallazgos podrían dar una vía de comprensión para las correlaciones negativas significativas halladas entre bullying y las dimensiones positivas de la amistad (proximidad, ayuda y seguridad), y las correlaciones positivas significativas halladas entre bullying y las dimensiones negativas de la amistad (conflicto y balance).

Estos resultados sobre su validez concurrente están en la línea de hallazgos que muestran a la amistad en la niñez y la adolescencia como un factor protector en la socialización (Rodriguez et al., 2021). Dicho factor protector se asociaba negativamente con ser acosado o acosar en estudios previos en niños argentinos (Rodriguez et al., 2015). Hay que destacar que las asociaciones detectadas son de tamaño mediano y pequeño, según Cohen (1988); con excepción de la asociación entre victimización y sintomatología depresiva, en donde era de tamaño grande, lo cual no es llamativo ya que uno de los correlatos más significativos de la victimización es con respecto a dicha sintomatología. Este resultado se encontró hace 20 años en revisiones metaanáliticas (Hawker & Boulton, 2000, 2003), como en estudios nacionales (Resett, 2018). No obstante, dichos tamaños del efecto son los que se hallan normalmente en psicología, debido a que los fenómenos son multicausales. Por otra parte, solamente en la dimensión compañerismo no se detectó correlación con respecto a hacer el bullying, lo cual debe ser objeto de análisis en futuros estudios.

Por todo lo dicho, estos hallazgos sugerirían que este instrumento también mantendría su bondad psicométrica en una muestra de niños argentinos escolarizados. La presente investigación representa un aporte para el estudio y diagnóstico de bullying en niños, en el marco del preocupante aumento de manifestaciones de agresividad en niños y adolescentes como un emergente social que hay que abordar desde una mirada multifactorial de la agresividad, teniendo en cuenta factores personales, familiares, educativos y sociales en interacción (Contini, 2015).

Entre las limitaciones del presente estudio podemos mencionar que solo se evaluaron las variables con medidas de autorreporte, lo cual deja fuera una mirada externa del fenómeno, como podría ser la mirada del docente o los padres, que en este tema puede ocultar información para dar respuestas socialmente deseables. Por otra parte, el evaluar todas las variables con la misma técnica de recolección de datos aumenta la correlación de las variables por la varianza compartida (Richardson et al., 2009). Otra limitación comprende el origen de la muestra, la cual es de una sola ciudad de Argentina y seleccionada de un modo no aleatorio, lo que puede sesgar la representatividad para la generalización de los resultados. Por otra parte, está comprobado que la estructura factorial de un test puede verse afectada por la composición demográfica de la muestra y su heterogeneidad a este respeto (Tabachnick & Fidell, 2013). Aunque aquí se detectó una estructura similar a la informada por los autores del instrumento, futuros estudios deberían tomar muestras de diversas zonas del país de forma aleatoria para poder generalizar los resultados y, por otra parte, medir las restantes variables con otras técnicas, además del autorreporte. Asimismo, futuras líneas de investigación podrían trabajar una variable clave en la interacción entre el acoso escolar y la relación de pares y de amistad como son las habilidades sociales. También se debería avanzar en la prevención de la problemática considerando la calidad de la amistad como un factor protector, dado que la amistad puede ser un factor protector tanto contra la victimización como contra sus correlatos emocionales negativos (Bernasco et al., 2022).

Referencias:

Achenbach, T. (2008). Assessment, diagnosis, nosology, and taxonomy of child and adolescent psychopathology. En M. Hersen & A. Gross (Eds.), Handbook of clinical psychology (pp. 429-457). John Wiley & Sons Inc.

Armitage, R. (2021). Bullying in children: impact on child health. BMJ Paediatrics Open, 5, e000939. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjpo-2020-000939

Arnett, J. J. (2020). Adolescencia y adultez emergente. Un enfoque cultural. Pearson.

Babarro, I., Andiarena, A., Fano, E., Lertxundi, N., Vrijheid, M., Julvez, J., Barreto FB, Fossati S. & Ibarluzea J. (2020). Risk and protective factors for bullying at 11 years of age in a Spanish birth cohort study. International journal of environmental research and public health, 17(12), 28-44. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17124428

Bentler, P. (1992). On the fit of models to covariances and methodology. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 400-404. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.112.3.400

Bernasco, E. L., van der Graaff, J., Meeus, W. H. J., & Branje, S. (2022). Peer victimization, internalizing problems, and the buffering role of friendship quality: disaggregating between- and within-person associations. Journal of Youth Adolescence, 51, 1653-1666. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10964-022-01619-z

Book, A.S., Volk, A. A. & Hosker, A. (2012). Adolescent bullying and personality: An adaptive approach. Personality and Individual Differences, 52(2), 218-223. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2011.10.028

Boomsma, A. & Hoogland, J. J. (2001). The robustness of LISREL modeling revisited. En R. Cudeck, S. du Toit & D. Sörbom (Eds.), Structural equation models: present and future. A festschrift in honor of Karl Jöreskog (pp. 139-168). Scientific Software International.

Breivik, K. & Olweus, D. (2012). An Item Response Theory Analysis of the Olweus Bullying Scale. Universidad de Bergen.

Brown, T. A. (2006). Confirmatory factor analysis for applied research. Guilford Press.

Bukowski, W. M., Hoza, B., & Boivin, M. (1994). Measuring friendship quality during pre- and early adolescence: The development and psychometrics of the Friendship Qualities Scale. Journal of Social and Personal Relationships, 11, 471-485.

Byrne, B. (2010). Structural equation modeling with AMOS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Routledge.

Byrne, B. (2012). Structural equation modeling with MPLUS: Basic concepts, applications, and programming. Routledge.

Caballero, S. V., Contini de González, N., Lacunza, A. B., Mejail, S., & Coronel, P. (2018). Habilidades sociales, comportamiento agresivo y contexto socioeconómico: Un estudio comparativo con adolescentes de Tucumán (Argentina). Cuadernos de la Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias Sociales. Universidad Nacional de Jujuy, (53), 183-203.

Card, N. A. & Hodges, E. V. (2008) Peer victimization among school children: correlations, causes, consequences, and considerations in assessment and intervention. School Psychology Quarterly, 23, 451-461. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0012769

Card, N. A., Isaacs, J. & Hodges, E. (2007). Correlates of school victimization: Recommendations for prevention and intervention. En J. E. Zins, M. J. Elias & C. A. Maher (Eds.), Bullying, victimization, and peer harassment: A handbook of prevention and intervention (pp. 339-366). Haworth Press.

Cohen, J. (1988). Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences (2a ed.). Academic Press.

Contini, E. N. (2015). Agresividad y habilidades sociales en la adolescencia. Una aproximación conceptual. Psicodebate, 15(2), 31-54. https://doi.org/10.18682/pd.v15i2.533

Cornell, D. G. & Bandyopadhyay, S. (2010). The assessment of bullying. En S. Jimerson, S. Swearer & D. Espelage (Eds.), Handbook of Bullying in Schools: An International Perspective (pp. 265- 276). Routledge.

DeVellis, R. F. (2012). Scale development: Theory and applications. SAGE Publications.

Espelage, D. & Swearer, S. (2003). Research on school bullying and victimization: What have we learned and where do we go from here? School Psychology Review, 32, 365-383. https://doi.org/10.1080/02796015.2003.12086206

Facio, A., Resett, S., Mistrorigo, C., & Micocci, F. (2006). Los adolescentes argentinos. Cómo piensan y sienten. Lugar.

Farrington, D. P. & Ttofi, M. M. (2011). Bullying as a predictor of offending, violence and later life outcomes. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health, 21, 90-98. https://doi.org/10.1002/ cbm.801

Fehm, L. & Hoyer, J. (2004). Measuring thought control strategies: The thought control questionnaire and a look beyond. Cognitive Therapy and Research, 28(1), 105-117. https://org. doi/10.1023/B:COTR.0000016933.41653.dc

Gaete, J., Valenzuela, D., Godoy, M.I., Rojas-Barahona, C.A., Salmivalli, C. & Araya, R. (2021). Validation of the Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire (OBVQ-R) Among Adolescents in Chile. Frontires in Psychology, 12, 578-661. https://org. doi/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.578661

Hartung, C., Little, C., S., Allen, E., K., & Page, M. (2011). A psychometric comparison of two self-report measures of bullying and victimization: Differences by sex and grade. School Mental Health, 3, 44-57. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579410000222

Hawker, D. S. J. & Boulton, M. J. (2000) Twenty Years’ Research on Peer Victimization and Psychosocial Maladjustment: A Meta-Analytic Review of Cross-Sectional Studies. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 41, 441-455. https://doi.org/10.1111/1469-7610.00629

Hawker, D. S. J. & Boulton, M. J. (2003). Twenty years' research on peer victimization and psychosocial maladjustment: A meta-analytic review of cross-sectional studies. En M. E. Hertzig & E. A. Farber (Eds.), Annual progress in child psychiatry and child development: 2000-2001 (pp. 505-534). Brunner-Routledge.

Horn, J. L. (1965). A Rationale and test for the number of factors in factor analysis. Psychometrika, 30, 179-185. https://doi.org/10.1007/bf02289447

Hu, L. & Bentler, P. (1999). Cutoff criteria for fit indexes in covariance structure analysis: Conventional criteria versus new alternatives. Structural Equation Modeling, 6, 1-55. https://doi.org/10.1080/10705519909540118

Kaplan, R. M. & Saccuzzo, D. P. (2006). Pruebas psicológicas: principios, aplicaciones y temas (6a ed). International Thomson.

Kline, R. B. (2015). Principles and practice of structural equation modeling (4a ed.). Guilford.

Kljakovic, M. & Hunt, C. (2016). A meta-analysis of predictors of bullying and victimization in adolescence. Journal of Adolescence, 49, 134-145. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.adolescence.2016.03.002

Kovacs, M. (1992). Children’s Depression Inventory Manual. Multi-Health Systems.

Kyriakides, L., Kaloyirou, C. & Lindsay, G. (2006). An analysis of the Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire using the Rasch measurement model. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(4), 781-801. https://doi.org/10.1348/000709905X53499

Lee, T. & Cornell, D. (2009). Concurrent validity of the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. Journal of School Violence, 9(1), 56-73. 10.1080/15388220903185613

Li, C. H. (2016). Confirmatory factor analysis with ordinal data: Comparing robust maximum likelihood and diagonally weighted least squares. Behaviour Research Method, 48, 936-949. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-015-0619-7

Lloret-Segura, S., Ferreres-Traver, A., Hernández-Baeza, A. & Tomás-Marco, I. (2014). El análisis factorial exploratorio de los ítems: una guía práctica, revisada y actualizada. Anales de Psicología, 30(3), 1151-1169. http://dx.doi.org/10.6018/analesps.30.3.199361

Luk, J. W., Patock-Peckham, J. A., Medina, M., Terrell, N., Belton, D. & King, K. M. (2016). Bullying perpetration and victimization as externalizing and internalizing pathways: a retrospective study linking parenting styles and self-esteem to depression, alcohol use, and alcohol-related problems. Substance use and misuse, 51(1), 113-125. https://doi.org/10.3109/10826084.2015.1090453

Masten, A. S. & Cicchetti, D. (2010). Developmental cascades. Development and Psychopathology, 22(3), 491-495. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0954579410000222

Nansel, T., Craig, W., Overbeck, M., Saluja, G., & Ruan, W. (2004). Cross-national consistency in the relationship between bullying behaviours and psychosocial adjustment. Paediatric and Adolescent Medicine, 158(8), 730-736. https://doi.org/10.1001/archpedi.158.8.730

O'Connor, B. P. (2000). SPSS and SAS Programs for Determining the Number of Components Using Parallel Analysis and Velicer's MAP Test. Behavior Research Methods, Instrumentation, and Computers, 32, 396-402. https://doi.org/10.3758/bf03200807

Olweus D. (1996). The Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. HEMIL, Universidad de Bergen.

Olweus, D. (1993). Bullying at school: What we know and what we can do. Blackwell.

Olweus, D. (1994). Annotation: Bullying at school: Basic facts and effects of a school based intervention program. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry and Allied Disciplines, 35, 1171-1190.

Olweus, D. (2013). School bullying: development and some important challenges. Annual Review of Clinical Psychology, 9, 751-780. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-clinpsy-050212-185516

Phillips, V. & Cornell, D. (2012). Identifying victims of bullying: Use of counselor interviews to confirm peer nominations. Professional School Counseling, 15, 123-131. https://doi.org/10.5330/PSC.n.2012-15.123

Quintero-Jurado, J., Moratto-Vásquez, N., Caicedo-Velasquez, B., Cárdenas-Zuluaga, N. & Espelage, D. L. (2021). Association Between School Bullying, Suicidal Ideation, and Eating Disorders Among School-Aged Children from Antioquia, Colombia. Trends in Psychology, 1, 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1007/s43076-021-00101-2

Resett, S. (2018). Análisis psicométrico del Cuestionario de Agresores/Víctimas de Olweus en español. Revista de Psicología de la Pontificia Universidad Católica del Perú, 36(2), 576-602. https://doi.org/10.18800/psico.201802.007

Resett, S. (2021). ¿Aulas peligrosas? Qué es el bullying, el cyberbullying y qué podemos hacer. Logos.

Resett, S., & Mesurado, B. (2021). Bullying and cyberbullying in adolescents: a meta-analysis on the effectiveness of interventions. En P. A. Gargiulo (Ed.), Psychiatry and Neuroscience (vol. 32; pp. 445-458). Springer.

Resett, S., Oñate, M. E., Hillairet, A., Furlán, M., & Jacobo, C. (2014). Victimización, agresión y autoconcepto en adolescentes de escuelas medias. Investigaciones en Psicología, 19(2), 103-118.

Resett, S., Rodriguez, L., & Moreno, J. E. (2013). Evaluación de la calidad de la amistad en niños argentinos. Psiquiátrica y Psicológica de la América Latina, 59(2), 94-102.

Resett. S. (2011). Aplicación del cuestionario de agresores/víctimas de Olweus a una muestra de adolescentes argentinos. Revista de Psicología de la Universidad Católica Argentina, 13(7), 27-44.

Richardson, H. A., Simmering, M. J., & Sturman, M. C. (2009). A tale of three perspectives: Examining post hoc statistical techniques for detection and correction of common method variance. Organizational Research Methods, 12(4), 762-800. https://doi.org/10.1177/1094428109332834

Rigby, K., Smith, P., & Pepler, D. (2004). Working to prevent school bullying: Key issues. En P. Smith, D. Pepler & K. Rigby (Eds.), Bullying in schools: How successful can interventions be? (pp. 1-12). Cambridge.

Rodriguez, L., Moreno, J. E., & Mesurado, B. (2021). Friendship Relationships in Children and Adolescents: Positive Development and Prevention of Mental Health Problems. En P. A. Gargiulo (Ed.), Psychiatry and Neuroscience (vol. 32; pp. 433-443). Springer.

Rodriguez, L., Resett, S., Grinóvero, M., & Moreno, J. E. (2015). Propiedades psicométricas de la Escala de Calidad de la Amistad para niños en español. Anuario de Psicología, 45(2), 219-234.

Roh, B. R., Yoon, Y., Kwon, A., Oh, S., Lee, S. I., Ha, K., Shin, Y., Song, J., Park, E., Yoo, H., & Hong, H. (2015). The structure of co-occurring bullying experiences and associations with suicidal behaviors in Korean adolescents. PloS one, 10, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0143517

Román, M. & Murillo, J. (2011). América Latina: violencia entre estudiantes y desempeño escolar. Revista CEPAL, 104, 37-54. https://doi.org/10.18356/8d74b985-es

Schmidt, R. E., Gay, P., d’Acremont, M., & Van der Linden, M. (2008). A German adaptation of the UPPS Impulsive Behavior Scale: Psychometric properties and factor structure. Swiss Journal of Psychology, 67(2), 107. https://doi.org/10.1024/1421-0185.67.2.10

Solberg, M. & Olweus, D. (2003). Prevalence estimation of school bullying with the Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire. Aggressive Behavior, 29, 239-268. https://doi.org/10.1002/ab.10047

Steinberg, L. (2018). Adolescence. Mc Graw-Hill.

Swearer, S. & Hymel, S. (2015). Understanding the Psychology of Bullying: moving toward a social-ecological diathesis stress model. American Psychologist, 70, 344-353. https://doi.org/10.1037/ a0038929

Tabachnick, B. G. & Fidell, L. S. (2013). Using multivariate statistics (6a ed.). Allyn & Bacon/Pearson Education.

Vivolo-Kantor, A. M., Martell, B. N., Holland, K. M., & Westby, R. (2014). A systematic review and content analysis of bullying and cyberbullying measurement strategies. Aggression and Violent Behavior, 19(4), 423-434. http://doi.org/10.1016/j.avb.2014.06.008

Wells, A. & Davies, M. I. (1994). The Thought Control Questionnaire: a measure of individual differences in the control of unwanted thoughts. Behavior Research and Therapy, 32(8), 871-878. https://doi. org/10.1016/0005-7967(94)90168-6

Weston, R. & Gore Jr, P. A. (2006). A brief guide to structural equation modeling. The Counseling Psychologist, 34(5), 719-751. https://doi.org/10.1177/0011000006286345

Cómo citar: Resett, S., Rodríguez, L. M., & Moreno, J. E. (2023). Propiedades psicométricas del Cuestionario Revisado de Bullying/Victimización de Olweus para Niños en español. Ciencias Psicológicas, 17(1), e-2872. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i1.2872

Contribución de los autores: a) Concepción y diseño del trabajo; b) Adquisición de datos; c) Análisis e interpretación de datos; d) Redacción del manuscrito; e) revisión crítica del manuscrito.

S. R. ha contribuido con a, b, c, d, e; L. M. R. con a, b, c, d, e; J. E. M. con a, d, e.

Editora científica responsable: Dra. Cecilia Cracco.

10.22235/cp.v17i1.2872

Original Articles

Psychometric properties of the Revised Olweus Bully/Bullied Questionnaire for Children in Spanish

Propiedades psicométricas del Cuestionario Revisado de Bullying/Victimización de Olweus para Niños en español

Propriedades psicométricas do Questionário Revisado de Bullying/Vitimização de Olweus para Crianças em español

Santiago Resett1, ORCID 0000-0001-7337-0617

Lucas Marcelo Rodríguez2, ORCID 0000-0001-5525-1155

José Eduardo Moreno3, ORCID 0000-0002-9613-0664

1 Universidad Argentina de la Empresa, Conicet, Argentina, [email protected]

2 Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina, Conicet, Argentina

3 Pontificia Universidad Católica Argentina, Conicet, Argentina

Abstract:

Bullying is an important risk factor for the mental health of children and adolescents, since victims’ present higher levels of emotional problems while those who carry it out show greater behavioural problems. Despite its relevance, few instruments exist for its measurement in school-age children. The present study sought to evaluate the psychometric properties of the Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire in a Spanish-speaking sample, with the particularity of being the first analysis of Spanish-speaking children. A quantitative study was carried out, implementing AFE, AFC, and Spearman's correlations. An intentional sample of 670 Argentinian children, male (48 %) and female (52 %), from 10 to 12 years old (mean age= 10.80; SD = 0.72) answered this test, such as the Friendship Quality Scale and the Kovacs Depression Inventory. The results indicated a factorial structure of two dimensions called victimization and bullying that coincided with those postulated by the author of the questionnaire. Cronbach's and Omega's alphas were satisfactory. The evidence of concurrent validity with the perception of the quality of friendship and depression was confirmed. The results indicated that this questionnaire presented adequate psychometric properties in its adaptation to Argentinian Spanish.

Keywords: bullying; children; psychometric properties; bully; bullied.

Resumen:

El bullying es un importante factor de riesgo para la salud mental de niños y adolescentes, ya que las víctimas presentan mayores niveles de problemas emocionales; mientras que los acosadores muestran mayores problemas de conducta. A pesar de su relevancia, existen pocos instrumentos para su medición en niños de edad escolar. El presente estudio buscó evaluar las propiedades psicométricas del Cuestionario Revisado de Bullying/Victimización de Olweus en una muestra de habla hispana, con la particularidad de ser el primer análisis de habla hispana en niños. Se realizó un estudio instrumental, implementando AFE, AFC y correlaciones de Pearson. Una muestra intencional de 670 niños argentinos, varones (48 %) y mujeres (52 %), de 10 a 12 años (edad media = 10.80; DE = .72) contestaron el cuestionario, la Escala de Calidad de la Amistad y el Inventario de Depresión de Kovacs. Los resultados indicaron una estructura factorial de dos dimensiones: victimización y bullying, que coincidieron con las postuladas por el autor del cuestionario. Los valores de los coeficientes alfas de Cronbach y de omega de McDonald fueron satisfactorios. Se confirmó la evidencia de validez concurrente con la percepción de la calidad de la amistad y la depresión. El cuestionario presentó adecuadas propiedades psicométricas en su adaptación al español argentino.

Palabras clave: acoso escolar; niños; propiedades psicométricas; bullying; victimización.

Resumo:

O bullying é um importante fator de risco para a saúde mental de crianças e adolescentes, uma vez que as vítimas apresentam maiores níveis de problemas emocionais enquanto aqueles que o praticam apresentam maiores problemas comportamentais. Apesar de sua relevância, existem poucos instrumentos para sua mensuração em crianças em idade escolar. O presente estudo procurou avaliar as propriedades psicométricas do Questionário Revisado de Bullying/ Vitimização de Olweus em uma amostra de língua espanhol, com a particularidade de ser a primeira análise em língua espanhola em crianças. Foi realizado um estudo instrumental, implementando AFE, AFC e correlações de Pearson. Uma amostra intencional de 670 crianças argentinas, meninos (48 %) e meninas (52 %), com idades de 10 a 12 anos (média de idade = 10,80; DP = 0,72) responderam ao questionário, a Escala de Qualidade da Amizade e o Inventário de Depressão de Kovacs. Os resultados indicaram uma estrutura fatorial de duas dimensões denominadas vitimização e bullying, que coincidiram com as postuladas pelo autor do questionário. Os valores dos coeficientes alfas de Cronbach e Omega de McDonald foram satisfatórios. Foi confirmada a evidência de validade concorrente com a qualidade percebida da amizade e a depressão. O questionário apresentou propriedades psicométricas adequadas em sua adaptação ao espanhol argentino.

Palavras-chave: assédio escolar; crianças; propriedades psicométricas; bullying; vitimização.

Received: 5/4/2022

Accepted: 3/24/2023

Bullying by peers is considered an important risk factor for the mental health of children and adolescents (Barbarro et al., 2020; Card & Hodges, 2008; Card et al., 2007; Nansel et al., 2004; Swearer & Hymel, 2015).

Bullying can be carried out in different ways: verbal (calling names, teasing, insults, etc.), physical (hitting, kicking, shoving, etc.), and indirectly, that is, without using direct physical or verbal contact with the victim (Resett, 2021; Rigby et al., 2004): spread rumours or exclude.

Both being a victim of bullying and carrying it out are risk factors for developmental psychopathology (Espelage & Swearer, 2003; Nansel et al., 2004). Victims generally present higher levels of emotional problems, such as depression, anxiety, low self-esteem (Olweus, 2013; Roth et al., 2015) and suicidal ideation (Quintero-Jurado et al., 2021), while those who commit it present a pattern of behaviour problems, such as antisocial behaviour, consumption of toxic substances, among others (Farrington & Ttofi, 2011; Nansel et al., 2004). It could be said that the victims would be prone to internalizing problems, while the aggressors would be prone to externalizing problems (Olweus, 1993, 2013). According to the model of externalizing and internalizing problems, the former affect the internal world of the person, with a maladaptive way of resolving conflicts, this resolution being internal level such as anguish, depression, suicidal ideation, etc. For their part, the latter would affect the external world of the person, with expression of emotional conflicts outwards, with impulsive discharge and externalization of aggression (Achenbach, 2008; Arnett, 2020; Caballero et al., 2018; Luk et al., 2016; Steinberg, 2018) A meta-analysis of 18 studies with schoolchildren detected an association between victimization with emotional, behavioural, and interpersonal problems. On the other hand, an association has been reported between bullying and externalizing problems, interpersonal problems, and poor school performance (Klajakovic & Hunt, 2016).

In general, the victims and perpetrators of bullying have a higher risk of presenting a worse psychosocial adjustment. Previous studies show that levels of friendship quality in children and adolescents are negatively related to being a victim or perpetrator of bullying (Rodriguez et al., 2015; Rodriguez et al, 2021). Since both the victims and those who carry out the bullying present this greater risk, it is vital to develop, use and adapt instruments with solid psychometric benefits to identify them. There are numerous techniques to measure this problem: structured observations, interviews, teacher and student nominations, self-reports, among others (Hartung et al., 2011). Self-reports, like questionnaires, have the advantage that they are techniques that are easy to apply and interpret, with low economic costs, and that can be applied on multiple occasions to see how the phenomenon evolves. Although there are numerous bullying measurement scales, not all of them have an exact definition of it or present its particularities such as power imbalance, repetition, among others (Vivolo-Kantor et al., 2014). The Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire, (Olweus, 1996) for children and adolescents is one of the instruments used in the world to measure this problem (Cornell & Bandyopadhyay, 2010). According to Olweus (1993), the advantages of this questionnaire are: to provide students with a clear definition of what is meant by bullying, to ask about bullying that has occurred in the last few months, and to present a time frequency of responses. The two main dimensions measured by the questionnaire are: bullying and being victimized (Olweus, 1994). This questionnaire has been used in numerous studies in different countries and its psychometric virtues were solidly proven, both with respect to its internal consistency, with very acceptable Cronbach's alphas fluctuating between .80 and .90 in numerous foreign studies both for the victimization dimension as for bullying (Olweus, 2013), as well as in relation to its validity and the property of differentiating between the students involved in the aggression and in being victimized (Solberg & Olweus, 2003). It has been adapted and translated in many countries and languages, such as the Netherlands, Japan, the United States, among others (Cornell & Bandyopadhyay, 2010; Gaete et al., 2021; Kyriakides et al., 2006; Lee & Cornell, 2009; Resett, 2018). The studies of the author of the test indicated that it presents adequate reliability and concurrent validity (Olweus, 2013). Regarding its concurrent validity, a linear association of victimization with emotional problems (depression, anxiety, and low self-esteem) and bullying with behavioural problems (antisocial behaviour, aggressiveness, and consumption of toxic substances) was demonstrated (Olweus, 2013; Resett, 2018).

Although bullying becomes more prevalent in the adolescent years, it is crucially important to identify potential victims and aggressors early, since in adolescence interventions to prevent and reduce bullying are less effective than in childhood (Resett & Mesurado, 2021). Furthermore, although empirical studies are scarcer in childhood than in adolescence, they show similar levels of prevalence of being victimized and bullying in both stages of the life cycle. Globally, it is noted that one in three children suffered from bullying in the last 30 days (Armitage, 2021). A study with children and adolescents in 16 Latin American countries found that Argentina was the country with the highest levels of physical bullying (Román & Murillo, 2011). In Argentina, specifically, 13% of victims, 10% of harassers and 5% of both were found in child samples (Resett, 2021). Research in Spain found 9% victims, 1% bullies, and 1% of both groups in children's shows (Babarro et al., 2020). Although the psychometric properties of said questionnaire were examined in samples of Argentinian adolescents, indicating adequate factorial structure, internal consistency, and concurrent validity (Resett, 2011, 2018), there are no studies in that country, as in Spanish-speaking nations, that have examined its properties in samples of school-age children.

In Argentina, as in many other countries in the region, most of the studies that have been carried out on bullying are of a theoretical nature and there is little scientific-empirical data in this regard and, even less, using instruments of recognized properties. Despite this fact, in recent years, research has been conducted on adolescents (Gaete et al., 2021; Resett, 2011, 2018) and children (Gaete et al., 2021; Resett, 2021).

Thus, it is vitally important to examine in a Latin American country and a cultural tradition different from that of the Nordic nations and North America if the instrument developed by Olweus retains its good psychometric properties. Thus, the strength of this study is that it is the first to evaluate the psychometric properties in a sample of Spanish-speaking children. As the Olweus questionnaire is an instrument widely used worldwide, its adaptation would allow a comparison of the levels of bullying reported internationally and a prompt identification of the problem.

Aims

To explore evidence of the factorial structure of the Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire in children and the internal consistency of this questionnaire.

To examine evidence of concurrent validity regarding depressive symptomatology and friendship quality.

Method

Participants

670 children selected in a non-probabilistic way participated in this research, males (48 %) and females (52 %), from 10 to 12 years old, with a mean age of 10.80 years (SD = 0.72) of average socioeconomic level. They belonged to 7 private (5 schools) and public (2 schools) primary level schools in the city of Paraná, province of Entre Ríos, Argentina, who were in the fifth and sixth grade of said educational levels. The inclusion criteria were to be between 10 and 12 years old, reside in Paraná, attend private or public primary school, and attend fifth or sixth grade.

Instruments

Bullying and victimization. Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire (Olweus, 1996). It consists of 38 questions to measure problems related to bullying in children and adolescents. In the first place, this instrument gives students a definition of what is to be understood by bullying, since bullying is a complex phenomenon and can be confused by students with other types of conflict between peers (Phillips & Cornell, 2012). Then comes the global question about whether they were victimized -in another section of the questionnaire they inquire about whether other students were bullied-: “Since classes started, how many times have you been harassed at school?” To make the measurement more precise and sensitive to change, the questionnaire asks about these behaviours in recent months. Next, the students are questioned about the different types of bullying they experienced -or that they carried out in the other part of the questionnaire-, based on nine questions about the frequency of the different forms of bullying: hitting, taking or breaking things, name calling, body teasing, sexual teasing, threats, excluding, lying, SMS or Internet bullying or other forms of being harassed or harassed; that is, physical (two questions), verbal (four), indirect or relational (two) and cyberbullying (one). The nine questions about being victimized and bullying can be added or averaged to make a scale, since they constitute the two large dimensions evaluated by this questionnaire (Kyriakides et al., 2006; Olweus, 1994, 2013). Examples of items are: “I was called ugly names, hit hard, or made fun of” (being victimized).

The Olweus Questionnaire uses the following response alternatives: Never, Once or twice, Two or three times a month, More or less once a week, and Several times a week. Responses are generally coded as 0 (Never) to 4 (Several times a week). In the present study, the Spanish version used by previous studies in Argentinian adolescents was used, which demonstrated good properties, such as construct validity, internal reliability, and concurrent validity (Resett, 2011, 2018). The author of the test points out that the version used in adolescents can be applied to children older than 10 years (Olweus, 1996). The version in Argentinian Spanish and the original are similar with the only difference that the first in the item verbal bullying by race or ethnicity was changed to "skin colour", since in its translation and adaptation process independent judges suggested said change for its ecological validity (Resett, 2018). The novelty of the present study is that the psychometric properties are evaluated in a sample of children, since the remaining studies in that country were in samples of adolescents. In this paper, only the questions of the victimization and bullying scales will be reported, since the remaining items are not part of these scales.

Friendship Quality Scale for children (Resett et al., 2013; Rodriguez et al., 2015), Spanish version of the Friendship qualities Scale version 4.1 from Bukowski et al. (1994). The children must mention the name of their best friend, the gender and if they attend the same course and then answer 33 items that describe qualities of friendship, indicating the degree of agreement with them. This questionnaire comprises six subscales or dimensions of friendship. They are: Fellowship: amount of volunteer time that friends share or spend together; Balance: balance in reciprocity, if in the friendship bond one of the subjects offers more than the other; Conflict: fights or arguments within the friendship relationship, disagreements in it; Help: mutual help and assistance, as well as help in conflict situations that can be experienced with other colleagues; Security: belief that when you need it, the friend is reliable and you can trust him or her (reliable alliance); y Proximity: feelings of affection or feeling special within the bond of friendship with each other, as well as the union of the bond. The questionnaire presents 4 alternatives responses: 1 (Totally disagree) to 4 (Totally agree). Regarding preliminary psychometric studies in Argentina, the Friendship Quality Scale has shown acceptable internal reliability indices for each of its subscales, with the following Cronbach's alpha coefficients: Companionship (.61), Help (.80), Safety (.70), Proximity (.81), Conflict (.80) and Balance (.65). The final version includes 7 items from the proximity dimension, 6 conflict items, 3 balance items, 5 companionship items, 7 help items, and 5 security items, that is, a total of 33 items. It presents good psychometric properties in Spanish, such as internal consistency (Rodriguez, 2015) and concurrent validity with family relationships (Rodriguez et al., 2021). In the present study, Cronbach's alphas were adequate with .82 for Closeness, .68 for Conflict, .61 for Balance, .81 for Help, .65 for Companionship, and .58 for Safety.

Kovacs Depression Inventory for Children (Kovacs, 1992). This questionnaire, one of the most widely used in the world, measures depressive syndrome in children and adolescents from 7 to 17 years of age. It consists of 27 items of three alternatives each. Higher scores imply greater depression. Its psychometric virtues are well established in Argentine samples, as adequate internal consistency, with values around .84 and concurrent validity with interpersonal relationships and behaviour problems (Facio et al., 2006). Cronbach's alpha of said inventory was .83 in the present sample.

Data collection

In the first place, principals of the schools were contacted in order to request authorization. Once the authorization of the directors was obtained, a note was sent in the student's communication notebook in order to request parental authorization. Anonymity, confidentiality and voluntary participation were ensured.

Data collection was carried out during class hours, within the classrooms and at the group level, with self-reports presented in paper format. During the sessions, two researchers from the project were always present to help the children in the event that there was any difficulty in understanding the instructions. The project was approved by a committee at the university that funded the research.

Data analysis

The data were analyzed in the SPSS version 23 Statistical Package for the Social Sciences program to obtain descriptive statistics (percentages, means, deviations, etc.) and inferential statistics (Cronbach's alphas, Spearman correlations, etc.). Parametric analyzes were performed because the bullying scale values had a relatively normal distribution: asymmetry ranged from 1.71 to 4.75 and kurtosis ranged from 2.08 to 7.18, since values greater than 3 for the former and greater than 8 for the latter are considered extreme (Boomsma & Hoogland, 2001), while other authors postulate values of 10 or more as extreme (Kline, 2015; Weston & Gore, 2006). Although the response format is ordinal, as in many other psychological tests, its distribution warrants that the data be treated continuously as indicated by other investigations (Schmidt et al., 2008) and as was done in adolescent samples with said instrument (Resett, 2011, 2018). For the remaining variables the values were .08 and 2.45 and .05 and 6.00, respectively.

First, the sample was randomly divided into two groups of 300 and 370, respectively. An exploratory factorial analysis (calibration study) was carried out with the first group using the maximum likelihood method, asking for eigenvalues greater than 1 and with Oblimin rotation -for related factors-, because principal component analysis is currently not recommended (Lloret-Segura et al., 2014). To determine factor retention, the classical implementation method of Horn (1965) was used. For retention, empirical eigenvalues were compared with random eigenvalues (means), then those above the random mean were selected (O'Connor, 2000). A number of replications equal to 100 and percentile representation of simulations equal to .95 were used.

With the second sample, a confirmatory factor analysis (replication study) was carried out with the MPLUS version 6 program to test the two-factor model postulated by the author of the test (Olweus, 2013; Solberg & Olweus, 2003) and also verified in studies of the questionnaire in adolescents (Resett, 2018), as shown in Figure 1. This approach was chosen based on the data -first an exploratory analysis and then a confirmatory one- because it is known that the factorial structures of an instrument may vary from one study to another or when a test is being adapted (Fehm & Hoyer, 2004; Wells & Davies, 1994). If a different model emerged from the factor analysis, this would also be tested to compare its fit. One of two independent or unrelated factors was also tested. Diagonally Weighted Least Squares (WLSMV) because the responses to the items were ordinal with five response options, as suggested (Brown, 2006, Li, 2016; Lloret -Segura et al., 2014).

Figure 1: Model of the Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire in Children to Be Tested

To consider whether the model was acceptable, the Comparative Fit Index (CFI), the Tucker-Lewis Index (TLI) and the average of the squared standardized residuals (RMSEA) were taken into account, since c2 statistic is very sensitive to sample size (Byrne, 2010, 2012). CFI and TLI values above .90 and RMSEA below .10 are considered adequate (Bentler, 1992; Byrne, 2010). There are also more demanding criteria with more than .95 and less than .05, respectively (Hu & Bentler, 1999).

For the analysis of internal consistency, in addition to Cronbach's alpha, the Omega was used due to the categorical nature of the alternatives that was extracted with the Jamovi 2.2.5 program.

Results

In order to evaluate the factor structure of the Olweus Questionnaire in children, an exploratory factor analysis was first carried out with the victimization and bullying items. The KMO index = .88, c2 (153) = 4046.04 p < .001 indicated that it was adequate to carry it out. Table 1 presents the results of the analysis. As shown in this table, two factors emerged: one is called victimization and the other bullying. When comparing the empirical eigenvalues with the random eigenvalues (means), the analysis indicated that it was appropriate to retain two that scored above the random eigenvalues, since the first two empirical values were 5.83 2.04 and the random ones scored 1.29 and 1.23, with the remaining values of the empirical analysis being below. All items loaded in their respective dimension with no cross-loads greater than .30.

Table 1: Factor Loadings for Exploratory Factor Analysis of the Revised Olweus Questionnaire in Children

Note. Only loads greater than .30 are presented.

As shown in Table 1, these two factors emerged, explaining a variance of 23 % and 19 %, respectively.

Confirmatory factor analysis was then carried out. A two-unrelated-factor model was also tested.

Regarding the confirmatory factor analysis, Table 2 shows the results of the analysis. As shown in that table, the two-associated-factor model yielded a better fit than the two-unrelated-factor model, as indicated by higher CFI, lower TLI, and RMSEA values, respectively.

Table 2: Fit Indices of the Revised Olweus Questionnaire Models in Children

Notes. df:

degrees of freedom; CFI: Comparative Fixed Index; TLI: Tucker-Lewis Index;

RMSEA: root mean square residual; c2/df value of c2

divided by the degrees of

freedom; ∆c2 difference of c2 between the models; ∆df difference

between the degrees of freedom of the models.

The factor loadings of the two related factors model were all significant and ranged from .41-.94. The correlation between both dimensions was .43, p < .001

When calculating Cronbach's alpha, it was .74 for the scale of being victimized and .81 for the bullying scale. The Omega coefficient was .75 and .83, respectively.

To observe the concurrent validity of the victimization and bullying scale, Spearman correlations were carried out between them and the Kovacs depression scale and the friendship scales of Bukowski et al. Table 3 shows the results of this analysis.

Table 3: Correlations between Olweus Victimization and Bullying Scales and Depression Scale and Friendship Scales

* p < .05 ** p < .01

As shown in Table 3, both the victimization and bullying scales correlated significantly with depression scores; the victimization scale was negatively correlated with proximity, help, companionship, and safety, and positively correlated with conflict and balance. The bullying scale was positively associated with conflict and balance scores, while it was negatively associated with proximity, helpfulness, and safety.

Discussion

The importance of this research lay in evaluating for the first time the factorial structure of the Revised Olweus Bully/Victim Questionnaire in a sample of children from Argentina to measure a highly topical phenomenon of notable psychological relevance, such as bullying. The psychometric properties of this test were evaluated in adolescents from that country, but not in children, for this reason the research was of great relevance.

Regarding the exploratory factorial analysis, the results yielded a model of two related factors that could be called victimization and bullying, without cross-loading and loading all in their respective factor. These two dimensions are those postulated by the author of the test (Olweus, 1996, 2013) and the two factors measured by the test. These results also coincide with studies on adolescents in Argentina (Resett, 2011, 2018). The two aforementioned dimensions have been shown to be associated with internalizing and externalizing problems in numerous studies (Olweus, 2013; Resett, 2018).

Regarding confirmatory factor analysis, the two-factor measurement model related -being victimized and bullying- also showed an adequate fit. For the fit to be acceptable, the CFI must be greater than .90 and the RMSEA less than .08 simultaneously (Bentler, 1992), which was the case for the present analysis. The adjustment was also close to the statistical criteria of CFI and RMSEA greater than .95 and less than .05, respectively (Hu & Blentler, 1999). Thus, the fit presented by the model was satisfactory. Such a model was much more suitable than a two-factor model with the two not associated dimensions. In this way, the results would suggest that also in Argentina, for school children, this instrument has a factorial structure similar to that detected in Anglo-Saxon and European countries: a dimension of victimization and another of carrying out bullying (Olweus, 1994, 1996). Foreign studies (Hartung et al., 2011; Kyriakides et al., 2006) reached the same conclusions, which provides some evidence of the psychometric robustness of the instrument by maintaining its factorial structure in samples from different cultures. Mainly taking into account that Argentina is a Latin nation, with less social and economic development and culturally different from that of the Anglo-Saxon and Nordic nations.