10.22235/cp.v17i1.2841

Escuela multinivel en contexto indígena: fortalezas, limitaciones y desafíos

desde la perspectiva de los profesores en La Araucanía

Multilevel schools in an indigenous context: strengths, limitations and challenges from the perspective of teachers in La Araucanía

Escola multinível em um contexto indígena: fortalezas, limitações e desafíos na perspectiva de professores em La Araucanía

Katerin Arias-Ortega1, ORCID 0000-0001-8099-0670

Natalia Díaz Alvarado2, ORCID 0000-0001-6838-8345

Daniela Catrimilla Castillo3, ORCID 0000-0002-3783-811X

María José Saldías Soto4, ORCID 0000-0002-1198-6421

1 Universidad Católica de Temuco, Chile, [email protected]

2 Universidad Católica de Temuco, Chile

3 Universidad Católica de Temuco, Chile

4 Universidad Católica de Temuco, Chile

Resumen:

El artículo expone las principales fortalezas, limitaciones y desafíos de la escuela multinivel en contexto indígena, desde las voces de los profesores en La Araucanía (Chile). La metodología es cualitativa, se aplicaron seis entrevistas semiestructuradas a profesores; la técnica de análisis de la información es el análisis de contenido en complementariedad con la teoría fundamentada. Los resultados revelan la persistencia de prejuicios hacia la familia indígena, el desconocimiento de los profesores sobre los saberes locales y la carencia de competencias para desarrollar una educación en perspectiva intercultural. Se concluye la necesidad de vinculación y diálogo entre escuela-familia-comunidad, lo que permita la revitalización de la identidad sociocultural en los procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje.

Palabras clave: cultura indígena; educación escolar; enseñanza y aprendizaje; pueblos indígenas y tribales; educación intercultural.

Abstract:

The article presents the main strengths, limitations and challenges of multilevel schools in an indigenous context, from the voices of teachers in La Araucanía, Chile. The methodology is qualitative and involved six semi-structured interviews with teachers. The technique for analyzing the information is content analysis in conjunction with grounded theory. The results reveal the persistence of prejudices towards indigenous families, the teachers’ lack of knowledge about local ways of knowing and the lack of competencies to develop education in an intercultural perspective. We conclude that there is a need for engagement and dialogue between the school, family and community, which would enable a revitalization of the socio-cultural identity in the teaching and learning processes.

Keywords: indigenous culture; school education; teaching and learning; indigenous and tribal people; intercultural education.

Resumo:

O artigo expõe as principais fortalezas, limitações e desafios da escola multinível em um contexto indígena, a partir das vozes de professores em La Araucanía, Chile. A metodologia é qualitativa, foram aplicadas seis entrevistas semiestruturadas, a técnica de análise da informação é a análise de conteúdo em complementaridade com a teoria fundamentada. Os resultados revelam a persistência de preconceitos em relação à família indígena, o desconhecimento dos professores sobre os saberes locais e a carência de competências para desenvolver uma educação com perspectiva intercultural. Concluímos sobre a necessidade de articulação e diálogo entre escola-família-comunidade, que permita a revitalização da identidade sociocultural nos processos de ensino e aprendizagem.

Palavras-chave: cultura indígena; educação escolar; ensino e aprendizagem; povos indígenas e tribais; educação intercultural.

Recibido: 1/3/2022

Aceptado: 2/3/2023

En contexto indígena, la escuela se caracteriza por ser multinivel en la que un solo profesor atiende en una misma sala de clases a todos los estudiantes desde primer a sexto año de Educación Básica (Arias-Ortega, 2020). Históricamente, este tipo de escuela se instaló en territorio indígena, principalmente, para avanzar en el proceso de evangelización de los niños indígenas y en el caso de La Araucanía de los niños y jóvenes mapuches. Sin embargo, con el devenir de los años las escuelas multinivel quedaron arraigadas en territorio indígena colonizado y hoy se caracterizan por una estructura inadecuada para ofrecer un proceso de enseñanza y aprendizaje que asegure el éxito escolar y educativo de los niños indígenas (Matengu et al., 2019). Asimismo, son escuelas que históricamente obtienen bajos resultados en las pruebas estandarizadas a nivel nacional (Arias-Ortega & Quintriqueo, 2021). Además, se distinguen porque albergan a las poblaciones rurales e indígenas quienes presentan contextos territoriales con mayores índices de vulnerabilidad social a nivel país.

El objetivo del artículo es dar cuenta de las fortalezas, limitaciones y desafíos de la escuela multinivel en contexto indígena desde las voces de los profesores en La Araucanía (Chile).

La escuela en contexto indígena una mirada global y local

Una mirada global y local en países como Canadá, Nueva Zelanda, México, Colombia, Bolivia, Ecuador, Perú y Chile permite constatar en las escuelas en contextos indígenas experiencias similares asociadas a: 1) la existencia de políticas educativas asimilacionistas para formar al indígena desde la lógica de la sociedad dominante. Así a los niños indígenas en la educación escolar, históricamente, se les daba un trato humillante enfrentándose a situaciones de violencia psicológica, castigos, abuso sexual y físico, que promovía el “genocidio cultural” (Commission de Vérité et Réconciliation du Canada, 2015; Dillon et al., 2022). 2) La enseñanza de contenidos escolares que minorizan e invisibilizan la historia propia, transmitiendo contenidos escolares que no permiten a los estudiantes indígenas identificarse con la historia de su pueblo (Harcourt, 2020; Manning & Harrison, 2018). 3) Relaciones educativas tensionadas entre profesores y estudiantes indígenas producto del desconocimiento de la historia local, cultural y los principios de educación indígena, lo que limita sus aprendizajes y genera a su vez un conocimiento disciplinario monocultural y aumenta el prejuicio al asumir al indígena como carente cognitivamente (Arias-Ortega & Ortiz, 2022; EagleWoman, 2022). 4) Las prácticas pedagógicas se sustentan en un pensamiento deficitario hacia sus estudiantes, generando relaciones e interacciones negativas, frustración e ira entre los involucrados. Así, se asume al indígena como alguien incapaz de avanzar al mismo ritmo de aprendizaje que el no indígena, producto de la falta de capital cultural (Sukhbaatar & Tarkó, 2022). 5) La escuela no ha logrado responder a las necesidades educativas, sociales, culturales y lingüísticas de la población que atiende, en cambio ofrece procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje descontextualizados, que no se ajustan a las necesidades socioculturales y territoriales de la familia y comunidad en la cual se sitúa (Milne & Wotherspoon, 2022). 6) La población indígena y en particular los estudiantes hablantes de lengua indígena exponen significativos rezagos en comparación con estudiantes no indígenas (Manning & Harrison, 2018; Matengu et al., 2019). 7) El desarraigo de la escuela con la realidad de las comunidades indígenas genera una escasa valoración de lo indígena, la falta de respeto hacia las autoridades tradicionales, el silencio y negación de la lengua dentro de la sala de clases y el autoritarismo de los profesores (Barrios, 2019; Meghan, 2022). 8) La escuela perpetúa la dominación simbólica y cultural de la población indígena para despojar a los estudiantes de sus marcos sociales, culturales y espirituales propios (Arias-Ortega & Quintriqueo, 2021; Delprato, 2019). 9) La existencia de altos índices de vulnerabilidad social y económica, acompañado del estigma social que genera la poca valoración de las diferencias culturales (Mallick et al., 2022).

En relación a los antecedentes mencionados cabe preguntarse ¿cuáles son las principales fortalezas, limitaciones y desafíos de las escuelas multinivel en contexto mapuche desde las voces de los profesores en La Araucanía (Chile)?

Método

Se utilizó una metodología cualitativa que permite comprender fenómenos educativos y sociales para transformar las prácticas y escenarios socioeducativos de la escuela multinivel en contexto indígena desde los significados, percepciones, intenciones y acciones atribuidos por los profesores de La Araucanía (Chile). Esto permite un doble proceso de interpretación: el primero respecto a la relación investigador-participante, debido a qué implica la manera en que los participantes interpretan la realidad que construyen socialmente; el segundo, la forma en que los investigadores sociales comprenden cómo los participantes construyen socialmente sus realidades (Archibald et al., 2019).

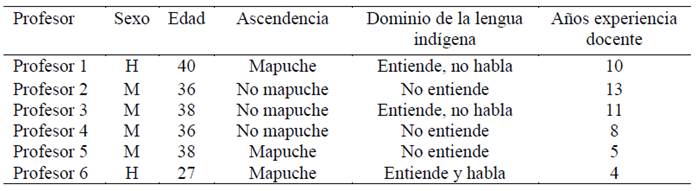

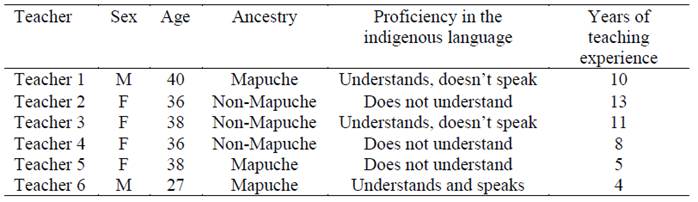

El contexto del estudio se sitúa en La Araucanía en escuelas multinivel situadas en comunidades mapuches rurales de Padre Las Casas (Arias-Ortega, 2020). Los participantes del estudio son seis profesores, descritos en la Tabla 1.

Tabla 1: Descripción de los participantes

Los criterios de inclusión son: 1) escuelas municipales o particulares subvencionados con cursos multinivel que presenten una matrícula de estudiantes con ascendencia mapuche y no mapuche; 2) escuelas situadas en comunidades mapuches rurales con más de 20 años de existencia en el territorio; 3) profesores mapuche y no mapuche con una experiencia de al menos 3 años desempeñándose en el sistema educativo escolar. La técnica para seleccionar a los participantes es intencional, no probabilística, donde los sujetos son seleccionados como casos típicos, con base en los criterios de edad, pertenencia étnica, género, escolaridad e identidad territorial (Arias-Ortega, 2020).

El instrumento de recolección de información es la entrevista semidirigida, que consultó sobre: 1) el sentido de la escuela y la educación escolar; 2) la experiencia de escolarización y cómo esta incide en la construcción del sentido de la escuela y la educación escolar en contexto indígena; y 3) los patrones recurrentes en la instalación de la escuela y la educación escolar en contexto mapuche (Arias-Ortega, 2020).

La técnica de análisis de la información es el análisis de contenido en complementariedad con la teoría fundamentada (Denzin et al., 2008). El análisis de contenidos permite formular inferencias de manera sistemática y objetiva según las características específicas del texto (Archibald et al., 2019). La teoría fundamentada permite descubrir teorías y proposiciones en relación directa con los datos a través de una codificación abierta y axial (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018).

La codificación abierta implicó generar códigos que emergen del análisis del testimonio de los profesores con base en la subjetividad del investigador según las expresiones y el lenguaje de los participantes encontrados en las frases literales que utilizaron durante la entrevista (Archibald et al., 2019). La codificación axial involucró la comparación de los códigos, búsqueda activa y sistemática de la relación que guardan los datos, los que se triangulan con los datos emergentes del análisis de contenido hasta llegar a la saturación teórica.

Para la comprensión de las citas extraídas de las entrevistas se utiliza la siguiente nomenclatura “(P8-HI(8:33))” donde P corresponde a profesor, 8 al número del documento de la entrevista, H si es hombre o M si es mujer, I para identificar si el profesor es indígena y los números entre corchete corresponden a la línea en que se ubica la cita mencionada en la unidad hermenéutica de Atlas Ti.

Los criterios de rigor científico considerados son la fiabilidad, que permite asegurar que los resultados representan algo verdadero e inequívoco, en el que las respuestas de los participantes son independientes de las circunstancias de la investigación (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018). La credibilidad que relaciona los hallazgos con base en las interpretaciones dadas por los participantes al objeto de estudio. Y la confiabilidad que alude a la posibilidad de encontrar resultados similares en el caso de que la metodología de investigación se replique en contextos educativos similares (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018). Además, los resultados obtenidos se triangulan con los antecedentes teóricos, lo que permite dar cuenta de la validez de estos. Los resguardos éticos consideraron el consentimiento informado, que estipula la voluntariedad de los participantes en la investigación.

Resultados

Los resultados se organizan en relación con una categoría central denominada escuela en contexto indígena y tres subcategorías asociadas a fortalezas, limitaciones y desafíos de la escuela multinivel en contexto indígena.

Fortalezas de la escuela multinivel en contexto indígena

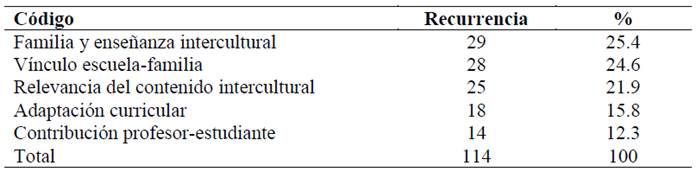

Esta subcategoría se relaciona con las características positivas que se desarrollan en el contexto educativo, que beneficia los procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje en contexto de escuelas situadas en comunidades mapuche en La Araucanía. Dicha subcategoría obtiene una frecuencia de 57 % de un total de 200 recurrencias y se compone de cinco códigos (Tabla 2).

Tabla 2: Fortaleza de la escuela multinivel en contexto indígena

El código familia y enseñanza intercultural refiere a la contribución de las familias y comunidades mapuches para la incorporación de conocimientos indígenas en las prácticas pedagógicas del profesorado, con la finalidad de promover una educación intercultural para todos los niños que asisten a la escuela, sean indígenas o no.

Una fortaleza de la escuela multinivel se relaciona con la posibilidad de incorporar los conocimientos locales y mapuches presentes en la memoria social de la familia y comunidad a los procesos educativos escolares con la implicación directa de la familia. Esto permite contextualizar y ofrecer procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje que respondan las necesidades propias del territorio, como lo es la revitalización de la identidad sociocultural mapuche de las nuevas generaciones, que no ocurre necesariamente en las escuelas urbanas. Ya que estas priorizan mayoritariamente una enseñanza hegemónica y monocultural que desconoce los conocimientos locales y propios como elementos relevantes para ofrecer aprendizajes significativos y con pertinencia cultural. Asimismo, son escuelas que, además, cuentan con una baja implicación de la familia y comunidad mapuche, al considerarla un factor que incide, en ocasiones, negativamente en los procesos educativos, producto de su baja escolaridad. En ese sentido, desde las voces del profesorado se reconoce como fortaleza que en sus escuelas multinivel existe una apertura para la enseñanza intercultural, lo que se refleja en la incorporación de un referente en tradiciones en la sala de clases, quien enseña los conocimientos de prácticas socioreligiosas a los estudiantes, lo que les permite ir más allá de lo académico e incorporar el aspecto espiritual propio de los niños indígenas.

Un testimonio señala que: “El colegio trabaja con la machi (autoridad espiritual mapuche), él enseña su cultura (en el aula) a los niños, y de esa forma se ha logrado integrar a la comunidad, (en la escuela, el machi celebra) ceremonias y rogativas (en las que participa la familia)” (P6-HI(6:35)). El testimonio da cuenta de cómo en la escuela multinivel se promueve la implicación con la familia y comunidad mapuche a través de la incorporación de prácticas epistémicas indígenas al espacio educativo como una forma de descolonización progresiva de los saberes aceptados en el medio escolar. Así se propician espacios para desarrollar procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje con pertinencia local que otorguen validez epistémica al saber mapuche en la educación escolar.

Desde la mirada del profesor indígena, la incorporación de los miembros de la comunidad mapuche, quienes dominan los saberes y conocimientos propios, facilita la asimilación de contenidos mapuches a los procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje. Asimismo, permite la valoración de lo indígena en el espacio aúlico, históricamente negado y que presenta rechazo en varios sectores urbanos de la población, al asumir que son conocimientos necesarios solo para el mapuche. De esta manera, incorporar dichos saberes en compañía de la familia y comunidad en las escuelas multinivel es una oportunidad y fortaleza, puesto que este tipo de escuelas no solo atiende a niños indígenas, sino también a campesinos y niños que se trasladan del sector urbano. Así a través de las prácticas pedagógicas en la escuela multinivel se avanza progresivamente en la sensibilización de indígenas y no indígenas en la educación escolar para formar ciudadanos interculturales respetuosos de la diversidad característica de un mundo globalizado, pero con pertinencia social, cultural y territorial.

Respecto al código vínculo escuela-familia, el profesorado expresa que existe participación de los apoderados en las escuelas porque ellos han generado e insistido en la necesidad de que los padres se impliquen en los procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje de sus hijos, consejo que le transmiten constantemente en las reuniones de padres y apoderados. Así, un profesor mapuche señala que: “Cada vez se acerca más la familia-escuela, los mismos apoderados presentan algún reclamo con cargos superiores, cada vez se va familiarizando más la escuela con la familia” (P1-HI(8:33)). El testimonio del profesor indígena releva que una relación escuela-familia permite dar cuenta de los resultados de aprendizaje de los niños. Se asume que la vinculación con la familia, aun cuando sea solo para quejas, se constituye en un avance y oportunidad de derribar la desconfianza y baja implicación de los padres en los procesos educativos. Desde el profesorado se explicita que es una fortaleza puesto que progresivamente los padres comienzan a llegar a la escuela para manifestar su malestar o preocupación por el proceso de enseñanza y aprendizaje de sus hijos. Sin embargo, se constata que esta concepción de vinculación familia-escuela viene dada desde una mirada funcionalista de la escuela y con base en aspectos más bien administrativos en la lógica de rendición de cuentas. Se sostiene que esta forma de vinculación es recurrente en contextos urbanos, pero se acrecienta en contextos rurales, producto del miedo y vergüenza étnica que expresan los padres al tener bajos niveles educativos, lo que les hace sentir que no tienen la autoridad para apoyar en los procesos escolares de sus hijos, asociados principalmente al contenido educativo monocultural. Desde esta perspectiva, la vinculación familia-escuela, al no considerar las necesidades y factores externos e internos (por ejemplo, la baja escolaridad y autoestima) que pueden estar incidiendo en el trabajo colaborativo entre ambas instituciones, podría incidir negativamente en el aprendizaje de los niños tanto en lo académico como en lo afectivo. Esta forma de vinculación daría cuenta de una carencia en la implicación de la escuela-familia en el acto educativo más allá de lo académico, en el que aspectos como el desarrollo espiritual, emocional, físico y cognitivo no necesariamente se estarían abordando. Esto plantea la urgencia de generar un trabajo mancomunado en pos de lograr el éxito escolar y educativo de manera integral en la formación de los niños y jóvenes. La vinculación familia-escuela termina asumiéndose desde un rol pasivo en la concepción de la educación de sus hijos respecto a las normas, valores y contenidos que reciben en su proceso de escolarización.

En relación con el código relevancia del contenido intercultural, este refiere a la importancia brindada por las escuelas multinivel a los contenidos indígenas durante los procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje. Los profesores relevan la importancia de incorporar contenidos indígenas en el aula como una forma de revitalización de la identidad sociocultural de los estudiantes para formar sujetos emocionalmente fuertes, con respeto y valoración hacia su origen, lo que les permita desenvolverse pertinentemente tanto en el contexto sociocultural propio como hegemónico. Al respecto, un profesor señala: “La importancia va radicada en que conocerán sus orígenes, es importante conocer la cultura de la cual uno proviene, nos haría más partícipes (...) empaparnos de la cultura, nos haría valorar más lo que tenemos y proyectarnos” (P4-M(4:34)).

Desde el testimonio del profesorado, sea indígena o no, se reconoce que en las escuelas multinivel desarrollar y fortalecer la identidad sociocultural de los estudiantes mapuches es relevante para desarrollar un sentido de pertenencia respecto a su cultura. Así, se asume un compromiso epistémico tanto con sus raíces y costumbres como también para profundizar en sus problemáticas y constituirse como un actor relevante que se compromete con las necesidades de la familia y comunidad mapuche. Desde el profesorado de las escuelas multinivel se releva que esta realidad de compromiso no necesariamente se expresa en contextos urbanos, debido a la gran cantidad de personas que componen las comunidades educativas, generando procesos educativos más despersonalizados. Mientras que en las escuelas multinivel la enseñanza y aprendizaje se da en un contexto más comunitario, con menor cantidad de niños, permite la personalización de la educación escolar desde un enfoque socioculturalmente pertinente, lo que contribuye al desarrollo emocional de los niños y jóvenes, favoreciendo su incorporación a una sociedad global.

En relación con el código adaptación curricular, este refiere a cómo los profesores en sus procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje articulan los contenidos indígenas y escolares en las prácticas pedagógicas para responder a las necesidades educativas de los estudiantes desde la lógica de la pertinencia social, cultural y territorial. Un testimonio señala que: “Se integra la lengua mapudungun como una asignatura que tiene varias horas contempladas por parte del Ministerio” (P4-M(4:66)). A partir del testimonio se puede dar cuenta de que la articulación del conocimiento indígena y escolar está asociado principalmente a la enseñanza de la lengua y cultura mapuche en el aula, que viene dada por obligatoriedad del Ministerio de Educación de Chile. De esta manera, en la escuela multinivel en contexto indígena el que se incorpore y reconozca el saber mapuche en los procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje constituye una fortaleza porque permite ofrecer procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje que valoren y tomen en consideración los saberes y conocimientos propios y previos que traen los estudiantes para ofrecer una educación contextualizada en el territorio.

Respecto al código contribución profesor-estudiante, este refiere al vínculo que se genera en la interacción entre ambos actores en el contexto educativo. Implica el aporte tanto escolar como de acompañamiento socioemocional del profesor hacia sus estudiantes a partir de su vocación profesional. Un profesor señala: “Tenemos muchas conversaciones dentro de las clases, de repente nos salimos del contenido y nos dedicamos más a lo que es de piel. Conversaciones del cómo están (...), cómo se sienten, se van sintiendo más familiarizados y con más confianza con uno” (P5-MI(5:43)). El testimonio evidencia que dada la menor cantidad de estudiantes que asisten a las escuelas multinivel es posible generar redes de mayor apego y trabajo más personalizado con los estudiantes y sus familias, lo que se expresa en un trato horizontal, mediante el acompañamiento socioemocional. Este aspecto de la relación entre profesor-estudiante permite tener una sana convivencia escolar y disminuir la deserción escolar de los estudiantes indígenas.

Limitaciones de la escuela multinivel en contexto indígena

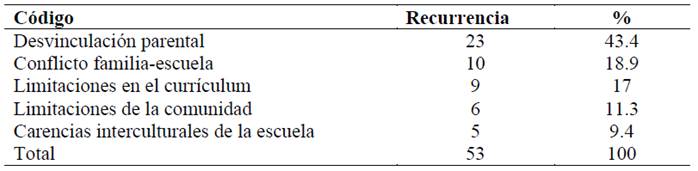

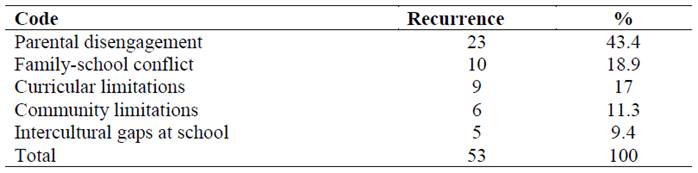

La subcategoría limitaciones de la escuela multinivel en contexto indígena refiere a los obstaculizadores que interfieren en el desarrollo de los procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje. Esta subcategoría obtiene una frecuencia de 26.5 % de un total de 200 recurrencias y se compone de cinco códigos (Tabla 3).

Tabla 3: Limitaciones de la escuela multinivel en contexto indígena

En relación al código de desvinculación parental, este alude a la falta de compromiso y preocupación de los padres por la educación escolar de sus hijos. Desde las voces de los profesores, esto se expresa en la responsabilidad que se le atribuye al profesorado como únicos responsables de la educación de los estudiantes. Respecto a esto un testimonio señala que “Se supone que la enseñanza es (...) cincuenta (por ciento) en la escuela, cincuenta en la casa, pero los niños solo estudian en el colegio, en la casa los papás muchas veces no le revisan ni siquiera la mochila” (P5- MI(5:33)). En contextos de escuelas multinivel esta percepción de abandono de las responsabilidades parentales pudiese explicarse debido a que los padres se asumen como incapaces de colaborar en el proceso escolar de sus hijos, principalmente por el desconocimiento de los contenidos escolares. Esto genera molestia en el profesorado, puesto que se sienten los únicos responsables de esa labor, lo que reconocen no es así, dado que la vinculación de la familia debiera ir más allá de lo académico. Asimismo, los profesores perciben que los padres delegan otras actividades y responsabilidades a los estudiantes (por ejemplo, cuidado de los animales), lo que incide en su proceso de enseñanza y aprendizaje en la escuela. Un testimonio señala que: “Los niños ayudan, (...) les desligan otras responsabilidades, menos las tareas, las tareas al último, hay muchos niños que van con la misma ropa que fueron el día anterior al colegio” (P4-M(5:35)). Dentro de las limitaciones de la escuela multinivel, se releva el prejuicio del profesorado hacia los niños y sus familias indígenas, al mencionar que los estudiantes asisten a clases con la misma ropa del día anterior. De este modo, no se cuestionan que esto pudiese generarse producto de necesidades económicas de la familia y no específicamente a la despreocupación de los padres por los cuidados de sus hijos. Esto plantea en las escuelas multinivel tomar consciencia de la población que atiende, ya que históricamente este tipo de escuelas se caracterizan por la vulnerabilidad económica y social de los niños que allí asisten, siendo los sectores con mayores índices de pobreza del país. Así, les plantea el desafío de ser estratégicos al abordar los contenidos de aprendizaje para promover una formación integral en el que se vinculen los aprendizajes adquiridos en el hogar con los contenidos pedagógicos y se favorezca la vinculación familia-escuela.

Respecto al código conflicto familia-escuela, este refiere a situaciones problemáticas o de tensión entre ambos actores. Un testimonio señala que: “Hay familias que no se meten ni por la mala, ni por la buena, no quiero generalizar, (...) papás que (...) en vez de facilitarle a sus hijos, les hacen la tarea para que (...) una como profesora vea que «su hijo cumplió»” (P4-M(4:42)). El testimonio da cuenta de los conflictos y malestar que genera en los profesores la actitud de los padres respecto de la colaboración en la educación de sus hijos, en el que más allá de implicarse en las actividades de aprendizaje, se avanza de manera rápida haciendo ellos mismos la actividad. Esto no permite que los estudiantes adquieran y desarrollen sus habilidades y conocimientos, puesto que no toman consciencia en relación con el saber que están aprendiendo. Asimismo, este testimonio podría dar cuenta de relaciones de poder y prejuicios que existen hacia la familia, en el que desde la percepción de la profesora se asume de manera unidireccional y sin evidencia que los padres les hacen la tarea a sus hijos. Más aún, si se consideran los bajos niveles educativos de los padres en territorios indígenas, quienes reconocen que su implicación en la enseñanza se ve limitada por el desconocimiento del contenido escolar. Así, se asume implícitamente que los niños indígenas “no serían capaces” de realizar las actividades por sí solos, lo que en escuelas multinivel aumentaría las relaciones de poder y prejuicios hacia lo mapuche.

Respecto al código limitaciones del currículum escolar, este alude a la escasa incorporación de contenidos indígenas a las distintas asignaturas de enseñanza, lo que no favorece una adecuada contextualización de los contenidos escolares con la cultura mapuche tanto a nivel nacional como regional. Esta problemática se dificulta aún más en escuelas multinivel que deben luchar además con una enseñanza en salas multigrado, en las que niños de distintos niveles etarios comparten el espacio áulico. Así, las limitaciones del currículum, si bien es cierto son generales a nivel nacional, se acrecientan en escuelas multinivel sorteando carencias económicas, una enseñanza multigrado, mala infraestructura, carencia de personal docente, entre otros. Además, estas limitaciones del currículum monocultural se conjugan con un desconocimiento de los profesores respecto del conocimiento indígena producto de su formación inicial docente de corte eurocéntrico occidental, que niega la validez epistémica del saber indígena. Un testimonio señala que: “Cambiar el currículum, enfocarse más en las culturas (...) ¿cómo vas a integrar, por ejemplo, a un niño aimara, mapuche o rapa nui, si el niño habla su idioma y tú no?… No sabes de qué se trata su cultura” (P5-MI(6:68)). Este relato permite inferir que existe una escasa formación de los profesores respecto de los contenidos indígenas de la zona en que se desarrollan las prácticas educativas, lo que limita ofrecer una educación pertinente y contextualizada. Asimismo, la rigidez del currículum escolar obstaculiza la transversalización del saber indígena en otras áreas disciplinares en el aula.

El código limitaciones de la comunidad refiere a los obstaculizadores por parte de las comunidades mapuches que dificultan las relaciones entre la escuela y la comunidad. Desde los relatos de los profesores, esto se manifiesta en la desconfianza de los padres hacia la escuela, lo que se expresa en la negación de las familias y comunidades mapuches por aportar saberes, prácticas y costumbres propias de la cultura para enriquecer los procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje. Un profesor señala: “(Celosos) me refiero a que ellos quieren mantener solamente sus aprendizajes, su cultura, sus costumbres y dejarla en ese núcleo, que no se mezclen con lo wigka” (P1-M(8:56)). De acuerdo al relato, existe recelo por parte de las comunidades mapuches en relación con la transmisión de las costumbres y tradiciones culturales. Esto se traduce en una limitación en el desarrollo del aprendizaje intercultural tanto de parte de los estudiantes como de la comunidad educativa en general. Asimismo, esto se pudiese explicar desde la perspectiva de los padres, quienes han construido históricamente una relación de desconfianza con la escuela, producto de la historia de esta institución en el territorio indígena, la que ha dejado huellas en padres y ancianos indígenas que vivieron prácticas de castigo físico, discriminación y racismo desde los actores educativos, que buscó un genocidio cultural del saber indígena en sus espacios. Estas limitaciones de la comunidad dejan en evidencia la resistencia recíproca que hay entre ambas instituciones para establecer un verdadero diálogo intercultural en pos de lograr el éxito escolar y educativo en todos los estudiantes.

El código carencias interculturales de la escuela se relaciona con las limitaciones del personal capacitado para la implementación de una educación intercultural. Un testimonio señala que: “Nos falta cultura en general y el único encargado de enseñar esa cultura es el profesor de mapudungun o el profesor hablante” (P2-M(4:33)). Este relato visualiza la falta de profesionales que posean competencias interculturales, como el dominio de la lengua mapuche, lo que se transforma en un obstáculo para la enseñanza y preservación de los marcos culturales en la escuela. Esto afecta la formación de las nuevas generaciones, repercute en el bienestar psicológico de los estudiantes indígenas e influye en la construcción de su identidad sociocultural. Esta problemática debiera abordarse de manera urgente en las escuelas multinivel, ya que tienen la oportunidad de implicar a la familia y sabios indígenas en las prácticas de enseñanza al estar insertas en comunidades mapuches donde el saber indígena sigue vivo. Por lo que la familia y la comunidad debieran constituirse en un laboratorio vivo de los saberes y conocimientos epistémicos propios para descolonizar la educación escolar desde abajo hacia arriba; es decir, desde la familia y la comunidad para permear en el sistema escolar.

Desafíos de la escuela multinivel en contexto indígena

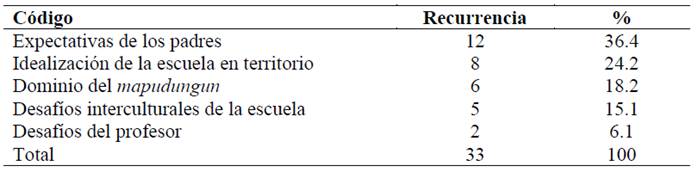

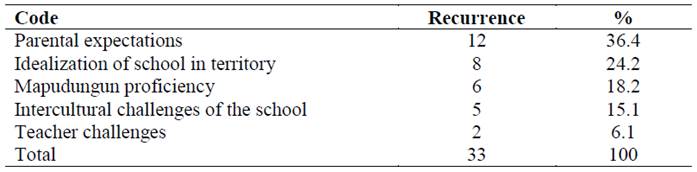

La subcategoría desafíos de la escuela en contexto indígena se relaciona con los aspectos a mejorar en los procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje. Esta obtiene una frecuencia de 16.5 % de un total de 200 recurrencias y se compone de cinco códigos (Tabla 4).

Tabla 4: Desafíos de la escuela multinivel en contexto indígena

En relación con el código expectativas de los padres, este se asocia con la proyección hacia el futuro que tienen los padres respecto a la educación escolar de sus hijos. Un profesor relata: “Algunos (padres) quieren que sus hijos logren llegar a la universidad (...), para varios es un sueño que sus hijos sean profesionales porque en sus familias no hay ningún (profesional)” (P5-MI(4:25)). El testimonio da cuenta de que los padres demuestran interés por la educación y la continuidad de los estudios de sus hijos y proyectan en ellos un nivel educativo que ellos mismos no alcanzaron. En otros casos, los profesores señalan que: “Ellos se conforman con que sus hijos sepan leer y escribir para que los puedan ayudar en los trabajos” (P4-M(4:26)). A partir de este relato se infiere que en contextos indígenas existen aspectos que condicionan las expectativas de los padres por la continuidad de los estudios de sus hijos, por ejemplo, lo económico, el nivel de alfabetismo de la familia, en el que se conforman con que sus hijos aprendan a leer o escribir porque les permitirá contribuir en la economía doméstica de manera inmediata, sin ver las posibilidades que podría traer para él y su familia la continuidad de estudios y adquisición de un título profesional.

El código idealización de la escuela en territorio indígena alude al ideal de escuela de acuerdo a la perspectiva de los profesores. Esta incorpora características interculturales tales como: símbolos propios de la cultura y un currículum escolar que responda a las necesidades de las comunidades mapuches. Un testimonio señala que “La escuela tendría que tener espacios, como dos banderas, la nacional y la de ellos, porque están insertos en la cultura mapuche; tendría que estar enfocada en las tradiciones de ellos, en las celebraciones de sus tradiciones” (P5-MI(5:40)). Esto releva que la escuela multinivel en el territorio indígena debiera incorporar símbolos y celebraciones asociados a la cultura mapuche que promuevan el sentido de pertenencia para que los estudiantes, familias y comunidades se sientan identificados con la escuela y su territorio. Otro testimonio agrega que “El currículum escolar sea intercultural, que vaya enfocado a varias culturas, no solo al currículum tradicional que tenemos ahora” (P6-HI(6:66)). Se puede inferir el desafío de incorporar un currículum escolar intercultural atingente que se conecte con las necesidades reales de la zona en la que se encuentre inmersa la escuela para poder entregar una educación de calidad y con pertinencia cultural.

El código dominio del mapudungun hace referencia al dominio de la lengua vernácula por parte de profesores que trabajan en el contexto indígena. Al respecto, un testimonio menciona que: “Para mí es desconocido, porque yo nunca tuve clases de mapudungun, entonces muchas cosas no sé cómo se pronuncian, (...) te puedo decir un par de palabras, pero llevarlas a contexto y utilizarlas en el diario vivir, no, no lo utilizo” (P3-M(4:31)). Se evidencia que existe un bajo dominio del mapudungun que se transforma en una barrera para la preservación de la lengua indígena, como también es un impedimento para comprender la cosmovisión de la cultura de los estudiantes. Asimismo, se constituye en un obstáculo en la relación que establecen con los miembros de la familia y la comunidad, puesto que no se lograría una comunicación en la que realmente se entienda lo que se transmite.

El código desafíos interculturales de la escuela hace referencia a propuestas realizadas desde la comunidad educativa con la finalidad de mejorar la educación intercultural, tanto en los contenidos escolares como en la inclusión de nuevas asignaturas. Un profesor señala que “El lenguaje también tiene que ver con la espiritualidad y con el cuidado del medio ambiente, sobre todo la cultura indígena cuida su entorno” (P6-HI(6:279). El relato manifiesta la importancia de considerar elementos de la cosmovisión mapuche, como la relevancia del medio ambiente. Se constata el reto de los profesores por involucrarse en la cultura mapuche, ya que por lo general no pertenecen al territorio y tienen una comprensión limitada de los elementos culturales, lo que se convierte en un desafío para la relación con los estudiantes, familias y la comunidad.

Finalmente, el código desafíos del profesor refiere al compromiso de los profesores por mejorar las competencias profesionales con el fin de entregar una educación de calidad y actualizada a los estudiantes. Respecto a este código, un testimonio plantea que “Como profesor es siempre aprender, siempre hacer más cursos, siempre estar aprendiendo, yo creo que uno muere y nunca termina de aprender” (P1-HI(1:93)). Se puede apreciar que existe un compromiso por parte de los profesores respecto a su propia formación y aprendizaje continuo para favorecer su desarrollo profesional, así como para la adquisición de herramientas que respondan a las necesidades de la realidad educativa y cultural del territorio en que se sitúa la escuela para ofrecer una educación en perspectiva intercultural.

Discusión y conclusiones

Los resultados de investigación nos permiten constatar que la escuela en general y la escuela multinivel en particular situada en contexto indígena no han logrado establecer una verdadera vinculación con la familia-comunidad mapuche. Esta relación queda relegada a aspectos administrativos, más allá de una implicación en el proceso de enseñanza y aprendizaje de los contenidos escolares e indígenas. Esta realidad es coherente con las dificultades de vinculación que se presentan en otros territorios indígenas, como es el caso de Nueva Zelanda, México y Colombia, donde se releva que existe una relación lejana y hasta hostil entre familia-escuela en contexto indígena (Archibald et al., 2019; Delprato, 2019; Harcourt, 2020). Esto pudiese explicarse por la desconfianza que tienen las familias hacia la escuela multinivel que es la misma que se instaló en sus territorios y en la que vivenciaron sus propias prácticas de escolarización, lo que ha dejado en ellos traumas psicológicos basados en el racismo sistémico hacia lo indígena. En general, las escuelas multinivel instaladas en territorios indígenas, desde la colonia hasta la actualidad, no han abandonado esta lógica de homogeneización de los niños, asumiéndolos desde enfoques paternalistas como carentes de capacidad cognitiva y ejerciendo un poder implícito hacia las familias y comunidades indígenas que se les ha atribuido producto de su formación profesional.

Aun cuando los profesores expresan buenas intenciones y disposición para favorecer relaciones de confianza con los padres para asegurar el éxito escolar y educativo de los estudiantes, en las prácticas de enseñanza y aprendizaje esto no se materializa. Así, por ejemplo, los prejuicios hacia lo indígena emergen recurrentemente en el discurso del profesorado no indígena, quienes sostienen que existe un desinterés de la familia mapuche por la educación de sus hijos, así como prácticas de descuido personal de los niños indígenas. Esta mirada prejuiciada se contradice con la postura del profesor indígena, quien afirma que las familias tratan de implicarse en los procesos educativos de sus hijos, reconociendo que factores como la pobreza o baja escolarización podrían incidir en una adecuada relación educativa. Algunos testimonios incluso justifican que estos vínculos familia-escuela podrían estar tensionados por las huellas que la escuela dejó en los padres y abuelos cuando vivieron su proceso de escolarización formal.

Desde las voces de los profesores indígenas y no indígenas es de vital importancia que la familia y la comunidad mapuche se implique en los procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje intercultural en la educación escolar. Así, la escuela debiera incorporar saberes y conocimientos indígenas en articulación con el currículum escolar para ofrecer una educación escolar pertinente social y culturalmente. Esto permitiría revertir las características históricas de la escuela en territorio indígena que sistemáticamente ha invisibilizado los saberes y conocimientos indígenas en los procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje (Arias-Ortega & Ortiz, 2022; Denzin & Lincoln, 2018; Dillon et al., 2022). De acuerdo con Meghan (2022), la escuela en contexto indígena debe contribuir a una convivencia intercultural entre personas y comunidades que reconocen sus diferencias en un diálogo sin prejuicios ni exclusiones para coconstruir un espacio educativo con sentido para la familia-comunidad. Así es posible revertir el prejuicio que se visibiliza por parte de los profesores hacia las familias y comunidades indígenas, quienes les atribuyen un sentido de desapego y responsabilidad con el proceso de enseñanza y aprendizaje de sus hijos.

En ese sentido, la escuela multinivel en territorio indígena tiene la posibilidad y oportunidad de fortalecer la identidad sociocultural de los niños mapuches al estar situada en el territorio que mantiene viva la cosmovisión y cosmogonía propia, lo que implicaría avanzar en una educación intercultural para la formación de las nuevas generaciones de niños indígenas y no indígenas (Mallick et al., 2022). No obstante, este no es un proceso pedagógico fácil, puesto que el currículum escolar tradicional se sitúa desde un marco normativo que excluye los contenidos interculturales con pertinencia local. Sin embargo, en las escuelas multinivel es más factible la contextualización de la enseñanza, debido a los laboratorios vivos de saberes y conocimientos indígenas en el territorio, a diferencia de lo que ocurre en los contextos urbanos. Se sostiene que el desconocimiento de los saberes indígenas de los profesores limita su incorporación en el aula y afecta la relación con el medio familiar y comunitario, producto de la desconexión de las necesidades y finalidades educativas de la escuela y la familia (Arias-Ortega, 2020). La escuela multinivel en contexto mapuche debería propiciar los espacios con el fin de lograr una mayor vinculación con los actores del medio familiar y comunitario para fortalecer la incorporación de conocimientos indígenas en los procesos escolares. Además, esta relación familia-escuela-comunidad permitiría la formación de sujetos fuertes emocionalmente y con un alto grado de pertenencia sociocultural, lo que contribuye además al desarrollo del bienestar individual y colectivo de la familia y comunidad mapuche. Desde esa perspectiva, la escuela en contexto indígena debiera favorecer instancias que permitan una sana relación y convivencia entre la comunidad, la familia y la escuela para disminuir la desconfianza entre familia-escuela-comunidad. Esta realidad plantea la necesidad y urgencia de generar espacios para la vinculación y diálogo entre los actores de la escuela, la familia y la comunidad de los estudiantes que asisten a ella. Asimismo, se sostiene que es urgente que la escuela se comprometa con la revitalización de la identidad sociocultural de los estudiantes indígenas y no indígenas en los procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje para formar sujetos fuertes emocionalmente con un alto autoconcepto, favoreciendo su éxito escolar y educativo en su proceso de escolarización formal. Esto permitiría propiciar el desarrollo de un currículum escolar que se adapte a las necesidades de la escuela situada en contexto mapuche para ofrecer procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje con adaptación territorial y cultural que resulten significativos para los estudiantes y sus familias; así como mejorar las competencias interculturales de los profesores para atender la diversidad de los estudiantes indígenas y no indígenas.

References:

Archibald, J., Lee-Morga, J. B. J., & De Santolo, J. (Eds.). (2019). Decolonizing Research Indigenous Storywork as Methodology. Zed Books.

Arias-Ortega, K. & Ortiz, E. (2022). Intervenciones educativas interculturales en contextos indígenas: aportes a la descolonización de la educación escolar. Revista Meta: Avaliação, 14(42), 193-217.

Arias-Ortega, K. & Quintriqueo, S. (2021). Relación educativa entre profesor y educador tradicional en la Educación Intercultural Bilingüe. Revista electrónica de investigación educativa, 23, 1-14. https://doi.org/10.24320/redie.2021.23.e05.2847

Arias-Ortega, K. (2020). Sentido de la escuela y la educación escolar en contexto indígena. Bases para una relación educativa intercultural. Proyecto Fondecyt de Iniciación 2020-2023.

Barrios, B. (2019). Educación intercultural: ¿Un espacio de encuentro o un campo de luchas? Revista Nuestra América, 7(14), 102-127.

Commission de Vérité et Réconciliation du Canada. (2015). Honorer la vérité, réconcilier pour l’avenir: Sommaire du rapport final de la Commission de vérité et réconciliation du Canada. McGill-Queen's Press-MQUP.

Delprato, M. (2019). Parental education expectations and achievement for Indigenous students in Latin America: Evidence from TERCE learning survey. International Journal of Educational Development, 65, 10-25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2018.12.004

Denzin, N. & Lincoln, Y. (2018). The SAGE Handbook of Qualitative Research. SAGE.

Denzin, N., Lincoln Y., & Smith, L. (2008). Handbook of critical indigenous methodologies. SAGE.

Dillon, A., Craven, R., Guo, J., Yeung, A., Mooney, J., Franklin, A., & Brockman, R. (2022). Boarding schools: A longitudinal examination of Australian Indigenous and non-Indigenous boarders’ and non-boarders’ wellbeing. British Educational Research Journal, 48(4), 751-770. https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3792

EagleWoman, A., Terry, D. J., Petrulo, L., Clarkson, G., Levasseur, A., Sixkiller, L. R., & Rice, J. (2022). Storytelling and Truth-Telling: Personal Reflections on the Native American Experience in Law Schools. Mitchell Hamline Law Review, 48(3), 1-9.

Harcourt, M. (2020). Teaching and learning New Zealand's difficult history of colonisation in secondary school contexts (Tesis de doctoral, Victoria University of Wellington). http://hdl.handle.net/10063/9109

Mallick, B., Popy, F. B., & Yesmin, F. (2022). Awareness of Tribal Parents for Enrolling Their Children in Primary Education: Chittagong Hill Tracks. Advances in Social Sciences Research Journal, 9(3), 101-109. https://doi.org/10.14738/assrj.93.11905

Manning, R. & Harrison, N. (2018). Narrativas de lugar y tierra: enseñanza de historias indígenas en la formación de profesores de Australia y Nueva Zelanda. Revista Australiana de Formación del Profesorado, 43(9). http://dx.doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2018v43n9.4

Matengu, M., Korkeamäki, R., & Cleghorn, A. (2019). Conceptualizing meaningful education: The voices of indigenous parents of young children. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 22, 100242. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lcsi.2018.05.007

Meghan, S. (2022) Deficit discourses and teachers’ work: the case of an early career teacher in a remote Indigenous school. Critical Studies in Education, 63(1), 64-79. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2019.1650383

Milne, E. & Wotherspoon T. (2022). Student, parent, and teacher perspectives on reconciliation-related school reforms. Diaspora, Indigenous, and Minority Education, 17(1), 54-67. https://doi.org/10.1080/15595692.2022.2042803

Sabzalian, L. (2019). Indigenous Children´s Survivance in Public Schoools. Routledge.

Sukhbaatar, B. & Tarkó, K. (2022). Teachers’ experiences in communicating with pastoralist parents in rural Mongolia: implications for teacher education and school policy. Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education, 50(1), 34-50, https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866x.2020.1818056

Financiamiento: Esta investigación fue posible gracias al proyecto Fondecyt de Iniciación n.° 11200306, financiado por la Agencia Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo de Chile.

Cómo citar: Arias-Ortega, K., Díaz Alvarado, N., Catrimilla Castillo, D., & Saldías Soto, M. J. (2023). Escuela multinivel en contexto indígena: fortalezas, limitaciones y desafíos desde la perspectiva de los profesores en La Araucanía. Ciencias Psicológicas, 17(1), e-2841. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v17i1.2841

Contribución de los autores: a) Concepción y diseño del trabajo; b) Adquisición de datos; c) Análisis e interpretación de datos; d) Redacción del manuscrito; e) revisión crítica del manuscrito.

K. A.-O. ha contribuido con a, b, c, d, e; N. D. A. con a, b, c, d; D. C. C. con a, b, c, d; M. J. S. S. con a, b, c, d.

Editora científica responsable: Dra. Cecilia Cracco.

10.22235/cp.v17i1.2841

Original Articles

Multilevel schools in an indigenous context: strengths, limitations and challenges from the perspective of teachers in La Araucanía

Escuela multinivel en contexto indígena: fortalezas, limitaciones y desafíos

desde la perspectiva de los profesores en La Araucanía

Escola multinível em um contexto indígena: fortalezas, limitações e desafíos na perspectiva de professores em La Araucanía

Katerin Arias-Ortega1, ORCID 0000-0001-8099-0670

Natalia Díaz Alvarado2, ORCID 0000-0001-6838-8345

Daniela Catrimilla Castillo3, ORCID 0000-0002-3783-811X

María José Saldías Soto4, ORCID 0000-0002-1198-6421

1 Universidad Católica de Temuco, Chile, [email protected]

2 Universidad Católica de Temuco, Chile

3 Universidad Católica de Temuco, Chile

4 Universidad Católica de Temuco, Chile

Abstract:

The article presents the main strengths, limitations and challenges of multilevel schools in an indigenous context, from the voices of teachers in La Araucanía, Chile. The methodology is qualitative and involved six semi-structured interviews with teachers. The technique for analyzing the information is content analysis in conjunction with grounded theory. The results reveal the persistence of prejudices towards indigenous families, the teachers’ lack of knowledge about local ways of knowing and the lack of competencies to develop education in an intercultural perspective. We conclude that there is a need for engagement and dialogue between the school, family and community, which would enable a revitalization of the socio-cultural identity in the teaching and learning processes.

Keywords: indigenous culture; school education; teaching and learning; indigenous and tribal people; intercultural education.

Resumen:

El artículo expone las principales fortalezas, limitaciones y desafíos de la escuela multinivel en contexto indígena, desde las voces de los profesores en La Araucanía (Chile). La metodología es cualitativa, se aplicaron seis entrevistas semiestructuradas a profesores; la técnica de análisis de la información es el análisis de contenido en complementariedad con la teoría fundamentada. Los resultados revelan la persistencia de prejuicios hacia la familia indígena, el desconocimiento de los profesores sobre los saberes locales y la carencia de competencias para desarrollar una educación en perspectiva intercultural. Se concluye la necesidad de vinculación y diálogo entre escuela-familia-comunidad, lo que permita la revitalización de la identidad sociocultural en los procesos de enseñanza y aprendizaje.

Palabras clave: cultura indígena; educación escolar; enseñanza y aprendizaje; pueblos indígenas y tribales; educación intercultural.

Resumo:

O artigo expõe as principais fortalezas, limitações e desafios da escola multinível em um contexto indígena, a partir das vozes de professores em La Araucanía, Chile. A metodologia é qualitativa, foram aplicadas seis entrevistas semiestruturadas, a técnica de análise da informação é a análise de conteúdo em complementaridade com a teoria fundamentada. Os resultados revelam a persistência de preconceitos em relação à família indígena, o desconhecimento dos professores sobre os saberes locais e a carência de competências para desenvolver uma educação com perspectiva intercultural. Concluímos sobre a necessidade de articulação e diálogo entre escola-família-comunidade, que permita a revitalização da identidade sociocultural nos processos de ensino e aprendizagem.

Palavras-chave: cultura indígena; educação escolar; ensino e aprendizagem; povos indígenas e tribais; educação intercultural.

Received: 1/3/2022

Accepted: 2/3/2023

The school is conceived of as an institution recognized by the State for the transmission of Chile’s socio-cultural heritage to new generations, from the logic of the dominant society (Arias-Ortega & Ortiz, 2022). In indigenous educational contexts, the school should respond to and address the social, cultural and linguistic diversity of the students present in the teaching and learning processes. This would result in a school education with social, cultural, linguistic and territorial relevance, contributing to the cultural and psychosocial development of ethnic groups in their formal schooling process (Sabzalian, 2019).

In an indigenous context, the school is characterized as multilevel, which means that a single elementary school teacher teaches all students from first through sixth grade in a single classroom (Arias-Ortega, 2020). Historically, this type of school was installed in indigenous territory, mainly to push forward the evangelization process of indigenous children and, in the case of La Araucanía, of Mapuche children and youth. However, over the years, multilevel schools became deep-rooted in colonized indigenous territory and today are characterized by an inadequate structure that fails to offer a teaching and learning process that ensures the schooling and educational success of indigenous children (Matengu et al., 2019). Likewise, these schools historically have low scores in standardized tests on a national level (Arias-Ortega & Quintriqueo, 2021). Furthermore, these schools are notable as being home to rural and indigenous populations with territorial contexts that include the highest rates of social vulnerability in the country.

The purpose of the article is to provide an account of the strengths, limitations and challenges of multilevel schools in an indigenous context, as told by teachers in La Araucanía, Chile.

The school in an indigenous context: a global and local perspective

A global and local look at countries such as Canada, New Zealand, Mexico, Colombia, Bolivia, Ecuador, Peru and Chile reveals similar experiences in schools in indigenous contexts: 1) the existence of assimilationist educational policies, used to educate indigenous people in keeping with the logic of the dominant society. Historically, indigenous children in school education have been humiliated and forced to endure psychological violence, punishment, and sexual and physical abuse, promoting “cultural genocide” (Commission de Vérité et Réconciliation du Canada, 2015; Dillon et al., 2022); 2) the teaching of educational content that minimizes and erases their own history, transmitting educational content that prevents indigenous students from identifying with the history of their people (Harcourt, 2020; Manning & Harrison, 2018); 3) strained educational relationships between teachers and indigenous students, as a consequence of the lack of knowledge of local and cultural history and the principles behind indigenous education. This limits their learning and in turn generates monocultural disciplinary knowledge and increases prejudice by assuming that indigenous people are cognitively lacking (Arias-Ortega & Ortiz, 2022; EagleWoman, 2022); 4) pedagogical practices are based on degrading thinking towards their students, generating negative relationships and interactions, frustration and anger among those involved. In this setting, the indigenous person is assumed to be incapable of moving forward at the same pace of learning as the non-indigenous person, a consequence of the lack of cultural capital (Sukhbaatar & Tarkó, 2022); 5) the school has failed to respond to the educational, social, cultural and linguistic needs of the population it serves, offering decontextualized teaching and learning processes that do not adjust to the socio-cultural and territorial needs of the family and community in which it is located (Milne & Wotherspoon, 2022); 6) the indigenous population and in particular indigenous language-speaking students fall significantly behind non-indigenous students (Manning & Harrison, 2018; Matengu et al., 2019); 7) the alienation of the school from the reality of the indigenous communities shows a low value placed on indigenous people, a lack of respect for traditional authorities, a silencing and negation of the language in the classroom, and the authoritarianism of teachers (Barrios, 2019; Meghan, 2022); 8) the school perpetuates a symbolic and cultural domination of the indigenous population that strips students of their own social, cultural and spiritual frameworks (Arias-Ortega & Quintriqueo, 2021; Delprato, 2019); and 9) the existence of high rates of social and economic vulnerability, accompanied by the social stigma generated by the low value placed on cultural differences (Mallick et al., 2022).

In relation to the above, the question that emerges is: What are the main strengths, limitations and challenges of multilevel schools in a Mapuche context from the voices of teachers in La Araucanía, Chile?

Method

The methodology is qualitative, which makes it possible to understand educational and social phenomena, to transform the socio-educational scenarios and practices of multilevel schools in an indigenous context, from the meanings, perceptions, intentions and actions attributed by teachers in La Araucanía, Chile. This enables a twofold process of interpretation. The first involves the researcher-participant relationship because it involves the way in which participants interpret the reality that they socially construct. The second involves the way in which social researchers understand how participants socially construct their realities (Archibald et al., 2019).

The study context is La Araucanía, Chile, specifically multilevel schools located in the rural Mapuche communities of Padre Las Casas (Arias-Ortega, 2020). The study participants are six teachers, who are described in Table 1.

Table 1: Description of participants

Inclusion criteria are: 1) municipal and/or private subsidized schools with multilevel classrooms and an enrollment of students with Mapuche and non-Mapuche ancestry; 2) schools located in rural Mapuche communities with more than 20 years of existence in the territory; 3) Mapuche and non-Mapuche teachers with at least 3 years of experience working in the school education system. The participant selection technique is intentional and non-probabilistic, where subjects are selected as typical cases, based on criteria of age, ethnicity, gender, schooling and territorial identity (Arias-Ortega, 2020).

The data collection instrument is the semi-directed interview, which inquired about: 1) the meaning of school and school education; 2) the schooling experience and how this affects the construction of the meaning of school and school education in an indigenous context; and 3) recurrent patterns in the installation of school and school education in a Mapuche context (Arias-Ortega, 2020).

The data analysis technique is content analysis in conjunction with grounded theory (Denzin et al., 2008). Content analysis makes it possible to formulate inferences systematically and objectively, based on specific characteristics of the text (Archibald et al., 2019). Grounded theory allows for the discovery of theories and proposals in direct relationship with the data, through open and axial coding (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018).

Open coding involved generating codes that emerge from the analysis of the teachers’ testimony based on the subjectivity of the researcher, according to the expressions and language of the participants found in the literal sentences they used during the interview (Archibald et al., 2019). The axial coding involved a comparison of the codes, an active and systematic search for the relationship between the data, which was triangulated with the data emerging from content analysis until reaching theoretical saturation.

The following nomenclature is used to understand the direct quotes from the interviews: “(P8-MI(8:33))” where P is the teacher, 8 is the number assigned to the interview document, M if male or F if female, I identifies if the teacher is indigenous and the numbers in brackets correspond to the line in which the mentioned quote is located in the hermeneutic unit of Atlas Ti.

The scientific rigor criteria considered are: 1) dependability, which ensures that the results represent something true and unambiguous, in which the participants’ responses are independent from the circumstances of the research (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018); 2) the credibility that connects the findings based on the interpretations given by the participants to the study object; and 3) reliability, which alludes to the possibility of finding similar results in the event that the research methodology is replicated in similar educational contexts (Denzin & Lincoln, 2018). The results obtained are also triangulated with the theoretical background, which enables us to ensure its validity. The ethical safeguards considered informed consent, which stipulates that research participants are participating voluntarily.

Results

The results are organized around a main category called school in an indigenous context and three subcategories associated with the strengths, limitations and challenges of multilevel schools in an indigenous context.

Strengths of the multilevel school in an indigenous context

The strengths of the school in an indigenous context subcategory refers to the positive characteristics that are developed in the educational context and that benefit the teaching and learning processes in the context of schools located in Mapuche communities in La Araucanía. This subcategory has a frequency of 57% of a total of 200 recurrences and is composed of five codes (Table 2).

Table 2: Strength of the multilevel school in an indigenous context

The family and intercultural education code refers to the contribution of Mapuche families and communities to the incorporation of indigenous knowledge in the pedagogical practices of teachers, with the aim of promoting intercultural education for all children attending school, regardless of whether or not they are indigenous.

One strength of the multilevel school is the possibility of incorporating local and Mapuche knowledge that is present in the social memory of the family and community into the school’s educational processes with the direct involvement of the family. This makes it possible to contextualize and offer teaching and learning processes that respond to the needs of the territory, such as the revitalization of the Mapuche sociocultural identity among new generations, which does not necessarily occur in urban schools. The majority of these schools prioritize hegemonic and monocultural teaching that overlooks specific local knowledge as relevant elements to offer meaningful and culturally relevant learning. Likewise, these schools are notable for the low involvement of the Mapuche family and community, considered a factor that sometimes has a negative impact on the educational processes, due to their low level of schooling. The teachers recognize that it is a strength that in their multilevel schools there is an openness to intercultural teaching. This is reflected in the incorporation of a tutor of traditions in the classroom, who teaches knowledge of socio-religious practices to students, which enables them to go beyond academics and incorporate the spiritual aspect of indigenous children.

One testimony indicates “The school works with the machi (Mapuche spiritual authority), he teaches his culture (in the classroom) to the children, which has made it possible to integrate the community (in the school, the machi celebrates), ceremonies and prayers (in which the family participates)” (P6-MI(6:35)). The testimony shows how the multilevel school promotes involvement with the Mapuche family and community through the incorporation of indigenous epistemic practices into the educational space as a form of progressive decolonization of the ways of knowing accepted in the school environment. This thereby creates spaces to develop teaching and learning processes with local relevance, which grant epistemic validity to Mapuche knowledge in school education.

From the indigenous teacher’s point of view, the incorporation of members of the Mapuche community, who are proficient in their own ways of knowing and knowledge, facilitates the incorporation of Mapuche content into the teaching and learning processes. Likewise, it places value on indigenous aspects in the classroom, which was historically denied in schools and rejected in several urban sectors of the population, as it was assumed that this knowledge is only necessary for the Mapuche person. Incorporating this knowledge together with the family and community in multilevel schools is an opportunity and a strength, since this type of school not only serves indigenous children, but also rural children and children who move from the urban sector. Thus, pedagogical practices in the multilevel school can lead to a greater sensitization of indigenous and non-indigenous people in school education to form intercultural citizens who are respectful of the diversity that characterizes a globalized world, but with social, cultural and territorial relevance.

Regarding the school-family engagement code, teachers indicate that parents participate in the schools, because they have generated and insisted on the need for parents to be involved in the teaching and learning processes of their children, advice that is constantly transmitted to them in parent-teacher meetings. A Mapuche teacher says, “The school and family are getting closer and closer. Parents have even brought up issues with management, the school is becoming more and more familiar with the family” (P1‑MI(8:33)). The testimony of the indigenous teacher shows that a school-family engagement helps to draw attention to children’s learning results. It is assumed that the engagement with the family, even if only for complaints, constitutes progress and an opportunity to tear down the mistrust and low involvement of parents in the educational processes. The teachers explain that this is a strength since parents are gradually beginning to come to the school to express their discomfort or concern about their children’s teaching and learning process. However, we note that this conception of school-family engagement comes from a functionalist viewpoint from the school and is based on more administrative aspects in the logic of accountability. We maintain that this functionalist form of engagement is recurrent in urban contexts, but it increases in rural contexts, as a result of the fear and ethnic shame expressed by parents who have low educational levels, which makes them feel that they do not have the authority to support their children’s schooling processes, mainly associated with monocultural educational content. From this perspective, by not considering external and internal factors and needs (for example, low schooling and self-esteem) that may be affecting the collaborative work between both institutions, the school-family engagement could have a negative impact on children’s learning on both an academic and emotional level. This form of engagement would therefore indicate a lack of school-family involvement in the educational act beyond mere academics, in which aspects such as spiritual, emotional, physical and cognitive development are not necessarily being addressed. This raises the urgency of generating joint efforts to integrally achieve school and educational success in the formation of children and youth. School-family engagement ends up taking on a passive role in the conception of their children’s education with respect to the norms, values and contents they receive in their schooling process.

In relation to the relevance of intercultural content code, this refers to the importance given by multilevel schools to indigenous content during the teaching and learning process. The teachers stress the importance of incorporating indigenous content into the classroom as a way of revitalizing the sociocultural identity of the students, to form emotionally strong subjects, with respect and appreciation for their origin, which will allow them to develop in a way that is pertinent to both their own sociocultural context and the hegemonic context. In this regard, a teacher says, “The importance lies in knowing their origins. It is important to know one’s culture, it makes us more involved (...) immersing ourselves in our culture makes us value what we have more and also helps us to project ourselves into the future” (P4-F(4:34)).

The testimony of both indigenous and non-indigenous teachers recognizes that in multilevel schools, developing and strengthening the sociocultural identity of Mapuche students is relevant in developing a sense of belonging to their culture. This assumes an epistemic commitment to both their roots and customs and a further look into their issues to become a relevant actor committed to the needs of the Mapuche family and community. The multilevel school teachers note that this reality of commitment is not necessarily expressed in urban contexts, due to the large number of people in the educational communities, resulting in more depersonalized educational processes. Whereas in multilevel schools, teaching and learning take place in more of a community setting with fewer children. This makes it possible to customize the school education with a socioculturally relevant approach, which contributes to the emotional development of children and young people, favoring their incorporation into global society.

In relation to the curricular adaptation code, this refers to how in their teaching and learning processes, teachers articulate indigenous and school contents in pedagogical practices to respond to the educational needs of students, from a logic of social, cultural and territorial relevance. One testimony says that “the Mapudungun language is integrated as a subject and the Ministry contemplates several hours of its instruction” (P4‑F(4:66)). The testimony shows that the articulation of indigenous and school knowledge is mainly associated with the teaching of Mapuche language and culture in the classroom, which is mandatory by the Chilean Ministry of Education. Thus, in the multilevel school in an indigenous context, the incorporation and recognition of Mapuche knowledge in the teaching and learning processes is a strength, because it enables teaching and learning processes that value and consider the ways of knowing and knowledge that students bring with them, in order to offer an education that is contextualized for the territory.

The teacher-student contribution code refers to the engagement between both actors in the educational context. It implies the teachers’ role in both the educational contribution and socioemotional mentoring of their students based on their professional vocation. A teacher says, “We have a lot of conversations in class. Sometimes we stray away from the content and get more into what is under the surface. Conversations about how they are (...), how they feel, they start feeling more comfortable and confident with you” (P5-FI(5:43)). The testimony shows that given the smaller number of students attending multilevel schools, it is possible to generate networks with greater attachment and more tailored work with students and their families, which is expressed in a horizontal treatment, through socioemotional mentoring. This aspect of the teacher-student relationship enables a healthy school coexistence and decreases the dropout rate of indigenous students.

Limitations of the multilevel school in an indigenous context

Table 3: Limitations of the multilevel school in an indigenous context

The parental disengagement code refers to the lack of parental commitment and concern for their children’s school education. In the teachers’ words, this is expressed in the responsibility parents attribute to the faculty as solely responsible for the education of students. In this regard, one testimony stated that “teaching is supposed to be (...) fifty (percent) at school, fifty at home, but children only study at school. At home parents often don’t even check their backpacks” (P5-FI(5:33)). In multilevel school contexts, this perception of abandonment of parental responsibilities could be explained by the fact that parents assume that they are incapable of collaborating with their children’s school process, mainly due to their lack of knowledge of the school content. This generates discomfort among teachers, who then feel that they are the only ones responsible for this task, which they recognize is not the case, since family engagement should go beyond academics. Likewise, teachers perceive that parents delegate other activities and responsibilities to students (e.g., animal care), which interferes with their teaching and learning process at school. One testimony indicates, “Children help, (...) they are given other responsibilities, anything but homework, homework is the last priority. Many children go to school with the same clothes they wore the day before” (P4-F(5:35)) The limitations of the multilevel school also notably include the teachers’ prejudice towards indigenous children and their families, by mentioning that students attend classes with the same clothes from the previous day. They do not stop to ask whether this could be the result of the family’s economic needs and not specifically the parents’ lack of concern for the care of their children. This raises the need for multilevel schools to be aware of the population they serve, since historically these types of schools are characterized by the economic and social vulnerability of the children who attend them, as these are the sectors with the highest poverty rates in the country. It challenges them to be strategic in approaching the learning contents, promoting a comprehensive formation in which the learning acquired at home is linked to pedagogical contents, thus favoring family-school engagement.

The family-school conflict code refers to problematic situations and/or tension between both educational actors. One testimony indicates, “There are families that don’t interfere one way or another, I don’t want to generalize (...) there are parents who (...) instead of making it easier for their children to do their homework, they do it for them so that (...) the teacher can see that «my child did their homework»” (P4-F(4:42)). The testimony shows the conflicts and unease that the parents’ attitude generates in the teachers in terms of collaboration in their children’s education, wherein rather than getting involved in the learning activities, the parents find it faster to just do the activity themselves. This prevents students from acquiring and developing skills and knowledge, since they have no awareness of the knowledge they are learning. Likewise, this testimony reveals the power relations and prejudices that exist towards the family, where the teacher’s perception is to unidirectionally assume without evidence that parents do their children’s homework. This is further exacerbated if we consider the low educational levels of parents in indigenous territories, who recognize that their involvement in teaching is limited by their lack of knowledge of school content. Therefore, there is an implicit assumption that indigenous children ‘would not be able’ to undertake the activities on their own, which in multilevel schools would increase power relations and prejudices towards the Mapuche people.

The curricular limitations code refers to the scarce incorporation of indigenous content in the different teaching subjects, which does not promote an adequate contextualization of school contents with the Mapuche culture on both a national and regional level. This problem is further exacerbated in multilevel schools that must also struggle with multigrade teaching, where children of different ages share a classroom. Although there are general limitations on a national level, the curricular limitations are even greater in multilevel schools that have to overcome economic shortages, multigrade teaching, poor infrastructure, lack of teaching staff, among others. In addition, these limitations of the monocultural curriculum are combined with a lack of knowledge among teachers regarding indigenous knowledge as a result of their western Eurocentric pre-service teacher education, which denies the epistemic validity of indigenous knowledge. One testimony indicates “change the curriculum, focus more on cultures (...). For example, how are you going to integrate an Aymara, Mapuche or Rapa Nui child, if the child speaks their language and you don’t... you don’t know anything about their culture” (P5-FI(6:68)). From this account we can infer that there is little teacher training with respect to the indigenous contents of the area in which they develop educational practices, which limits the ability to provide a relevant and contextualized education. Likewise, the rigidity of the school curriculum hinders the mainstreaming of indigenous knowledge in other disciplinary areas in the classroom.