Ciencias Psicológicas v16n2

julho-dezembro 2022

10.22235/cp.v16i2.2250

Artigos Originais

Adaptation for online implementation of a Positive Psychology intervention for health promotion

Adaptación para la implementación online de una intervención en Psicología Positiva para la promoción de la salud

Helen Bedinoto Durgante1, ORCID 0000-0002-2044-6865

Débora Dalbosco Dell’Aglio2, ORCID 0000-0003-0149-6450

1 Universidade Federal de Pelotas, Brasil, [email protected]

2 Universidade La Salle e Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil

Resumo:

Este estudo descreve a adaptação online de uma intervenção em Psicologia Positiva para promoção de saúde. Como diretriz metodológica, utilizou-se o The Formative Method for Adapting Psychotherapy e o Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research, nos eixos: características da intervenção; dos indivíduos; contextos interno e externo; processo de implementação. A intervenção consistiu em 6 encontros grupais online, com 10 integrantes da equipe de gestão em saúde de uma associação de aposentados do RS, Brasil, média de idade 43,6 anos (DP = 15,86). Um questionário de avaliação foi preenchido ao final das atividades e estatísticas descritivas revelaram satisfação dos participantes com a intervenção e com o moderador, assim como generalização dos conteúdos. Foram sugeridas alterações, especialmente aumento da carga horária das sessões. Sugere-se a sistematização dos processos utilizados neste estudo para embasar pesquisas de implementação e adaptação de intervenções online para diferentes contextos e público-alvo.

Palavras-chave: psicologia positiva; promoção de saúde; adaptação online.

Abstract:

This study describes the online adaptation of a Positive Psychology intervention for health promotion. The methodological guidelines used were The Formative Method for Adapting Psychotherapy and the Consolidated Framework for Implementation, based on: characteristics of the intervention; of the individuals; internal and external contexts; implementation process. The intervention consisted of 6 online group sessions, with 10 staff members from the health management team of a retiree association in RS/Brazil, mean age 43.6 years (SD = 15.86). An evaluation questionnaire was completed at the end of the activities and descriptive statistics revealed participants' satisfaction with the intervention and with the moderator, as well as generalization of the contents. Changes were suggested specially to increase the duration of the sessions. We suggest the systematization the processes used in this study to support research on the implementation and adaptation of online interventions for different contexts and populations.

Keywords: positive psychology; health promotion; online adaptation.

Resumen:

Este estudio describe la adaptación online de una intervención en Psicología Positiva para la promoción de la salud. Como guía metodológico se utilizó el The Formative Method for Adapting Psychotherapy y Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research en: características de la intervención; de individuos; contextos internos y externos; proceso de implementación. La intervención consistió en 6 reuniones grupales con 10 miembros del equipo de gestión de salud de una asociación de jubilados en RS (Brasil), con una edad promedio de 43.6 años (DE = 15.86). Se completó un cuestionario de evaluación al final de las actividades y las estadísticas descriptivas revelaron la satisfacción de los participantes con la intervención, con el moderador y generalización de los contenidos. Se sugirieron cambios, especialmente aumento en la carga de trabajo de las sesiones. Sugerimos sistematizar los procesos utilizados en este estudio para apoyar la investigación sobre la implementación y adaptación de intervenciones para diferentes contextos y públicos.

Palabras clave: psicología positiva; promoción de la salud; adaptación online.

Recebido: 27/08/2020

Aceito: 14/06/2022

O ano de 2020 iniciou como marco de mudança na história da humanidade, após ter sido anunciada pandemia, pela Organização Mundial da Saúde (World Health Organization [WHO], 2020a, 2020b), como emergência de saúde pública. Detectada pela primeira vez em Wuhan, na China, a doença COVID-19 é caracterizada como uma síndrome respiratória aguda grave, causada pelo novo betacoronavirus 2 –SARS-CoV2– denominada novo corona vírus (Huang et al., 2020; Spina et al., 2020). Além da rápida progressão para casos graves da doença, outro diferencial da COVID-19 quando comparado a outros quadros infecciosos é o elevado índice de contágio entre indivíduos/grupos, ou, contágio por até mesmo horas posteriores a partir da exposição às superfícies contaminadas com o vírus (Duan et al., 2020). Embora os índices finais de mortalidade pela COVID-19 ainda não possam ser contabilizados devido à rápida progressão da doença nos países, taxas de letalidade têm sido consideradas altas quando comparados às crises anteriores do Século XXI, causadas por coronavírus SARS-CoV e MERS-CoV, uma vez que, atualmente, há subnotificação de casos devido à escassez de amostras, reagentes e equipamentos para testagens e estabelecimento de diagnóstico mundialmente (Driggin et al., 2020; Watkins, 2020).

Em termos de saúde mental e física de indivíduos, tanto devido ao risco iminente de contágio pelo vírus quanto devido ao distanciamento/isolamento físico e quebra na rotina de vida, é possível enfatizar fatores intervenientes à pandemia que deflagram incerteza sobre o futuro e crises psicológicas. Além disso, há baixa percepção de controle, insegurança quanto ao aporte fornecido por instituições sociais para atenuar problemas socioeconômicos provenientes da perda de empregos, redução ou inexistência de trabalhos e renda, no caso de trabalhadores informais, provedores de serviços, empresas, entre outros. Somado a estes, falta de políticas públicas e investimentos que supram necessidades básicas para o enfrentamento da pandemia são estressores que agregam riscos à saúde mental da população. Ainda há o despreparo dos gestores e incoerência no fornecimento de informações sobre procedimentos de segurança para a população, por parte dos níveis e órgão de poderes públicos, o que tende a gerar ainda mais sintomatologia ansiogênica e depressogênica para a população e, principalmente, àqueles que são considerados grupo de risco (WHO, 2020a, 2020b).

Para lidar com questões tão complexas relativas à saúde mental, estratégias de promoção de saúde e prevenção de doenças estão entre as principais práticas sugeridas. Estas servem não somente para atender aos casos pré-clínicos, subdiagnosticados e/ou sintomas clínicos e prevenir a reocorrência de problemas de saúde, mas também como medida para compilar evidências que norteiem e embasem a elaboração de políticas públicas e sustentabilidade da rede de saúde (WHO, 2020a, 2020b).

Em diversos países, intervenções para promoção de saúde vêm sendo implementadas em formato online/virtual (também chamadas eHealth/mHealth interventions) para maior capilaridade de acesso para grupos de risco, devido ao baixo custo das intervenções (Welch et al., 2016) e por serem mais eficazes para mudanças de comportamento tendo em vista seu caráter interativo, quando comparadas a websites motivacionais ou puramente informativos (Mouton & Cloes, 2013). Alguns exemplos de intervenções implementadas de forma online para promoção de saúde de adultos e idosos são práticas direcionadas a cuidadores informais (familiares) que incluem componentes de apoio profissional e social, instruções para mudança de comportamento e resolução de problemas (Richard et al., 2019); para pacientes com câncer e seus respectivos cuidadores (Northouse et al., 2014); intervenções autodirigidas para vários quadros de saúde mental (estresse pós-traumático, depressão, ansiedade, fobias) e física (dieta e atividade física) (Rogers et al., 2017). Entre os benefícios mais expressivos para saúde mental identificados após participação em intervenções online, dados de revisões indicam redução de depressão em intervenções por aplicativos com enfoque na promoção de saúde, comparados aos aplicativos de treinos cognitivos (Firth et al., 2017) e ganhos quanto à prevenção de depressão (Ebert et al., 2017).

No Brasil também há normativas vigentes para regulamentação da atuação de psicólogos por meios de tecnologias da informação e da comunicação (TICs) para acesso remoto dos participantes de intervenções, tais como: a Resolução nº 11, de 11 de maio de 2018, que regulamenta a prestação de serviços psicológicos realizados por meios de TICs; a resolução nº 11/2018, que regulamenta a prática de Avaliação Psicológica; a Nota Técnica nº 07/2019, que orienta sobre o uso de testes psicológicos em serviços realizados através de TICs; a resolução nº 04, de 26 de março de 2020, que dispõe sobre regulamentação de serviços psicológicos prestados por meio de TICs durante a pandemia do COVID-19 e auxilia no cadastramento de psicólogos para serviços on-line (Marasca et al., 2020).

Assim, considerando que, neste momento de grave necessidade há impossibilidade de se atuar com intervenções grupais em caráter presencial devido às medidas restritivas dos países para promover distanciamento físico da população geral e contenção da transmissão da COVID-19; considerando que, não há prazo definido para a normalização dos procedimentos padrões para assistência e fornecimento de serviços de saúde; considerando que, é fundamental que haja adaptação dos serviços e intervenções para promoção de saúde, a partir do uso de TICs para acesso à distância/remoto; este estudo tem como objetivo descrever o processo de adaptação de uma intervenção em Psicologia Positiva para a promoção de saúde com implementação em caráter online – Programa Vem Ser.

Descrição da intervenção: O Programa Vem Ser

Intervenções Psicológicas Positivas (IPPs) vêm sendo implantadas mundialmente para a promoção de saúde física e mental. Este modelo de intervenção inclui abordagens quanto às experiências subjetivas positivas, traços considerados força, as quais constituem virtudes de caráter, e também contextos institucionais positivos, de modo a favorecer melhor funcionamento psicológico e de saúde (Durgante, 2017; Magyar-Moe et al., 2015; Proyer et al., 2014; Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009).

IPPs têm demonstrado eficácia para melhora no bem-estar e indicadores de qualidade de vida tanto em casos de indivíduos com diagnóstico clínico quanto em casos não-clínicos (Bolier et al., 2013; Durgante & Dell’Aglio, 2019; Nikrahan et al., 2016), melhor resposta a tratamentos e reabilitação (Reppold et al., 2015), melhor recuperação de efeitos psicofisiológicos negativos como reatividade cardiovascular, processos inflamatórios e imunossupressão, os quais tendem a ser agravados em situações estressoras (Cohn & Fredrickson, 2010).

Assim, com base na literatura científica sobre IPPs grupais (Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009) em a Terapia Cognitivo-Comportamental (Knapp & Beck, 2008), foi desenvolvido o Programa Vem Ser. O programa é composto por seis sessões semanais (2 h cada) grupais presenciais e se propõe a intervir nas seguintes forças: Valores e autocuidado/prudência, otimismo, empatia, gratidão, perdão, significado de vida e trabalho. A versão inicial do programa, implementada de forma presencial, passou por estudo piloto (Durgante et al., 2020a), estudo de viabilidade (Durgante et al., 2019b) e ensaio de eficácia (Durgante & Dell’Aglio, 2019), com amostra de mais de uma centena de aposentados do sul do Brasil. Resultados quantitativos indicaram efeitos principais do programa para melhoras em indicadores de satisfação com a vida, resiliência, sintomas de estresse percebido, depressão e ansiedade no grupo interventivo, além de efeitos de interação para melhoras no otimismo, empatia, sintomas de depressão e ansiedade no grupo experimental quando comparado ao grupo controle. Os efeitos e impactos contatados para satisfação com a vida, sintomas de depressão e ansiedade se mantiveram três meses após o término do programa (Durgante et al., 2020b). Contudo, visto a atual situação pandêmica e necessidade de adaptar serviços em caráter remoto para todas as populações e níveis de atenção em saúde, a versão online do programa foi adaptada para realização de intervenções direcionadas ao público em geral (Durgante et al., 2019a).

Método

Delineamento

Para implementação e avaliação da versão online do Programa Vem Ser, foi desenvolvido um estudo longitudinal misto (qualitativo/quantitativo), com avaliação de resultados pré (T1- na semana anterior ao início da intervenção) e pós-intervenção (T2-na semana do término das sessões), com base no método The Formative Method for Adapting Psychotherapy (Hwang, 2009), em 5 fases: I. Gerar conhecimento e colaboração com stakeholders (partes interessadas); II. Integrar as informações geradas com teoria e conhecimento empírico e clínico; III. Revisar e iniciar a intervenção no formato adaptado com os stakeholders/público-alvo; IV. Conduzir testes preliminares com a versão adaptada da intervenção; V. Finalizar a versão culturalmente adaptada da intervenção. Como diretriz metodológica utilizada para consideração de ajustes/adequações necessárias para adaptação da intervenção ao novo contexto/organização/instituição de saúde e formato online, foi utilizado o Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research, (CFIR; Damschroder et al., 2009), que leva em consideração 29 critérios subdivididos nos seguintes eixos de avaliação: Características da intervenção; contextos interno e externo; características dos indivíduos envolvidos; processo de implementação. Os dados quantitativos foram avaliados a partir de estatísticas descritivas; os dados qualitativos foram avaliados a partir de Análise de Conteúdo do tipo Temática (Saldaña, 2009), com os eixos e critérios estabelecidos no CFIR (Damschroder et al., 2009).

Participantes

Participaram por conveniência e voluntariamente 10 (Feminino = 9) integrantes da equipe de gestão em saúde de uma associação de aposentados do Estado do Rio Grande do Sul, Brasil. Entre os profissionais que compuseram a amostra estão enfermeira, fisioterapeuta, biomédica, assistentes sociais, estagiárias de Serviço Social, médico e diretora social, conforme critérios de inclusão previamente definidos: 1) ser profissional das áreas de saúde/educação/assistência; 2) ter disponibilidade para participar das sessões e avaliações do programa; 3) ter acesso a internet, computador/celular/tablete ou algum dispositivo que permita acesso às sessões do programa em caráter online. A média de idade dos participantes foi 43,6 anos (DP = 15,86), com mínimo 20 e máximo 62 anos de idade. A média de tempo total de trabalho na vida funcional/laboral foi 15,4 anos (DP = 13,5) com variação de 01-34 anos de serviço, sendo em média 2,48 anos no cargo atual (DP = 2,73). Seis participantes eram casados ou tinham união estável, quatro tinham filho(s), dois participantes moravam sozinhos. Três participantes eram aposentados (por idade, por tempo de contribuição, e especial) e uma estava em processo de preparação para aposentadoria. Três participantes eram cuidadores de pessoas de seu convívio próximo. Nove participantes relataram ser vivido algum tipo de acontecimento significativo/impactante de vida no último ano e também nove identificaram pelo menos uma fonte (pessoa/instituição) como rede de apoio. Seis participantes tinham algum tipo de crença ou religião, cinco relataram ter algum problema crônico de saúde física ou mental (ansiedade com e sem crises de pânico, depressão, dor de estômago, câncer). Três participantes relataram estar passando por luto. Todos os participantes tinham algum tipo de atividade de lazer, entre elas: ler/estudar (4), praticar atividades físicas (4) (caminhada (1), pilates (1), academia (1), corrida (1)), assistir filmes/séries (3), ficar com a família (2), viajar (2), dançar (1), trabalho voluntário (1), assistir programas de decoração (1) escutar música (1), ir ao cinema (1), sair com amigos (1), passear ao ar livre (1), comer (1).

Instrumentos

Foram utilizados os seguintes instrumentos:

Questionário de dados sociodemográficos (T1): Contendo questões sobre idade, sexo, aspectos laborais, nível educacional, composição familiar.

Ficha de Avaliação do Programa (T2): Contém 12 questões objetivas de autorrelato com respostas que variam de 1-insatisfeito; 4-muito satisfeito, sendo: 6 questões que avaliam a satisfação com o programa, com o moderador, com o horário e tempo de duração das sessões, e as aprendizagens advindas do programa; duas questões sobre clareza e compreensão 2 conteúdos abordados e 4 questões sobre generalização (aplicação na vida) dos conteúdos abordados no programa. Além disso, o instrumento também inclui duas questões descritivas que solicitam exemplos de conteúdo do programa utilizados e sugestões/feedbacks para melhorias no programa (Durgante et al., 2019b).

Diário de campo do moderador: Utilizado para registros ao longo e ao término das sessões, com base nos critérios do protocolo CRIF (Damschroder et al., 2009) para qualidade metodológica na avaliação de processo de implementação do programa.

Procedimentos

A pesquisa teve aprovação do Comitê de Ética da Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul-UFRGS sob parecer nº 4.143.219. Inicialmente foram feitos contatos com a equipe diretiva da associação de aposentados para divulgação do programa. Foi utilizada uma perspectiva Bottom-Up, a partir do envolvimento direto e colaboração com stakeholders em todas as fases da pesquisa. Foram conduzidas três reuniões (2.30 h - 3 h cada) com a equipe diretiva (N = 5) para viabilizar a proposta junto aos profissionais da associação. As diferentes fases dos procedimentos (fases I, II, III e IV), que incluem a preparação do programa e sua implementação, resultados e discussão dos dados (fase V) estão descritas a seguir.

Fase I. Geração de conhecimento e colaboração com stakeholders

Com base no eixo ‘Características da intervenção’ (Intervention characteristics) do protocolo CFIR, algumas questões foram debatidas quanto aos seguintes critérios: evidências sobre forças e qualidades da intervenção (Evidence strength and quality) com dados sobre estudos conduzidos, resultados obtidos e apresentação do manual de implementação do programa; problematização sobre vantagens de implementar a intervenção versos alguma solução alternativa (Relative advantage) e sobre o potencial de adaptabilidade (Adaptability) da intervenção, das atividades propostas, dinâmicas, horários, abordagem das temáticas para público-alvo diferenciado (profissionais) da versão original do programa (idosos/aposentados); foi discutida a possibilidade de se conduzir um estudo para grupo reduzido –equipe diretiva e de gestão em saúde– em ambiente controlado, permitindo incluir a percepção dos participantes no processo de adaptação e implementação da intervenção (Trialability); foi discutido o potencial da intervenção prejudicar práticas da rotina de trabalho da instituição e ações necessárias para que a equipe de gestão em saúde pudesse participar do programa (Complexity). Este critério permitiu flexibilizar o acesso, de modo que a própria equipe diretiva, em decisão conjunta com a equipe de gestão em saúde, optou por alocar horário/turno de trabalho para que os profissionais pudessem participar do programa, sem comprometer suas tarefas laborais. O turno e horário para a implementação do programa foram escolhidos pelos próprios participantes. Quanto ao critério ‘Design quality and packaging’, foi elaborado projeto estruturado do programa, contendo introdução sobre questões de promoção de saúde e literatura de relevância, estrutura, método, e resultados obtidos. Também foi apresentado o manual do programa e uma breve discussão com a equipe diretiva sobre como o programa poderia ser implementado junto à associação.

Fase II. Integrar as informações geradas com teoria, conhecimento empírico e clínico

Nesta fase, foram discutidos com a equipe diretiva critérios do eixo ‘Contexto externo’ (outer setting), contendo questões sobre a necessidade de apoio/suporte psicológico para a equipe diante de demandas crescentes em saúde, tanto dos associados, quanto da própria equipe em face à pandemia e possíveis temáticas a serem abordadas no programa, relevantes aos profissionais e com base na literatura científica, tais como: esgotamento físico e mental, irritabilidade, disfunção do sono/ansiedade, sobrecarga de serviços/longas horas de trabalho, percepção de impotência diante do atual quadro de saúde (Patient needs and resources).

Com relação ao ‘Contexto interno’ (inner setting), as reuniões abordaram questões da equipe sobre o quanto a intervenção estava de acordo com a cultura organizacional (Culture) e clima de implementação (Implementation climate), uma vez que o programa poderia ser útil, apoiado e reconhecido como aporte para saúde mental dos profissionais (compatilbility) eos quais não dispunham de proposta estruturada para promoção de sua própria saúde. Foi enfatizada necessidade de se perceber a receptividade e priorização (relative priority), por parte do público-alvo após divulgação do programa, para se ter uma idéia sobre a demanda por este tipo de serviço neste contexto específico. Vale ressaltar que houve apoio e incentivo por parte da equipe diretiva para participação dos profissionais (organization incentives and rewards), o que favoreceu posterior implementação do programa.

Quanto ao eixo 'Características dos Indivíduos', após as reuniões iniciais com a equipe diretiva, esta se percebeu com maior conhecimento para divulgar o programa para a equipe de gestão em saúde (Knowledge and beliefs about the intervention).

Fase III. Revisar e iniciar a intervenção no formato adaptado com os stakeholders/público-alvo

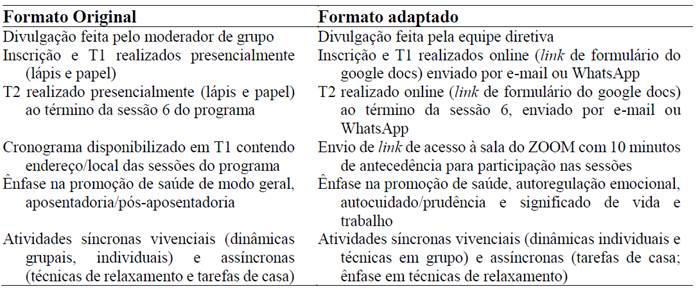

A partir dos eixos e critérios avaliados nas fases iniciais, com base na percepção da equipe diretiva, foi possível introduzir adaptações iniciais no processo (Eixo: Processo, critério: planning) de seleção dos participantes e temas de interesse para o público-alvo, devido ao momento histórico no qual o programa foi implementado, quando o Brasil se encontrava como um dos epicentros mundiais da pandemia de COVID-19. As adaptações incluídas contemplam o processo de sistematização das atividades pré e durante o programa para implementação online e também revisões e ênfase em temas de interesse relatados pela equipe de gestão em saúde. A tabela 1 apresenta as alterações inicialmente incluídas para implementação online do programa.

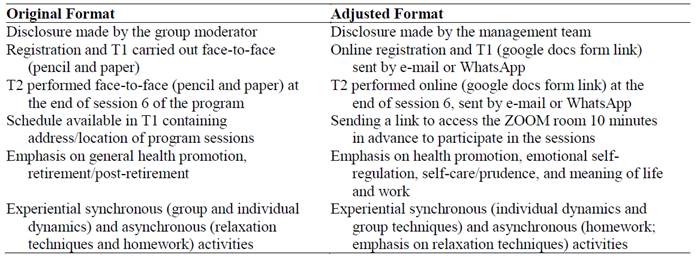

Tabela 1: Alterações iniciais incluídas para implementação do Programa Vem Ser online

Fase IV. Conduzir testes preliminares com a versão adaptada da intervenção

Após os ajustes iniciais na estrutura do programa, foi conduzido grupo com a versão adaptada do Programa Vem Ser junto à equipe diretiva para avaliar a funcionalidade dos componentes adaptados do programa e alguns critérios de viabilidade, como avaliação preliminar desta modalidade de intervenção. As sessões online foram implementadas durante seis quartas-feiras consecutivas, com início às 10h. A média de tempo de duração das sessões foi 2 h 17 (DP = 0,11), sendo a Sessão 5 (Tema: Perdão) a mais curta, com duração de 2 h 08 e a Sessão 6 (Tema Significado de Vida e Trabalho) a mais longa, com duração de 2 h 37, incluindo a avaliação de T2. Houve apenas uma falta (Sessão 3: Empatia), o que configura 98,3 % de frequência do grupo. Todos os participantes (N = 10) concluíram o programa e T2.

Os indicadores de resultados avaliados seguiram os critérios SMART (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, timely), propostos no eixo ‘Processo’ (reflecting and evaluating) (Damschroder et al., 2009). A demandafoi considerada satisfatória, uma vez que houve unanimidade na percepção de necessidade desta modalidade de intervenção, neste momento histórico e contexto específico, tanto por parte da equipe diretiva quanto da equipe de gestão em saúde. Todos os profissionais da equipe optaram por participar voluntariamente do programa. Foi elaborada lista de espera para os demais profissionais interessados, bem como manifesto interesse e solicitação por parte da equipe diretiva para oferta do programa aos membros da associação (aposentados) em momento futuro.

Fase V. Finalizar a versão culturalmente adaptada da intervenção

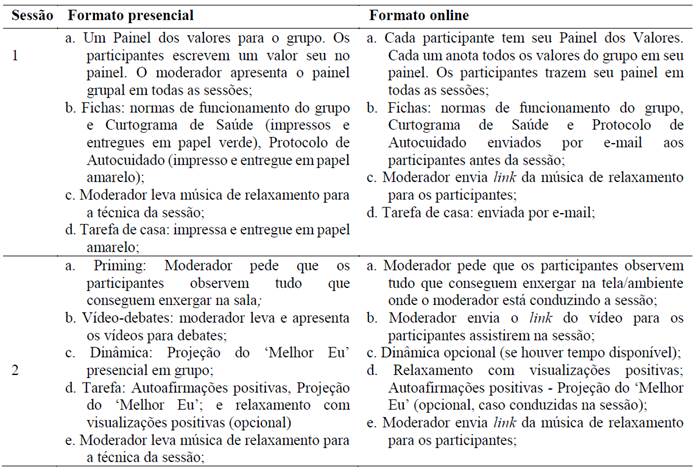

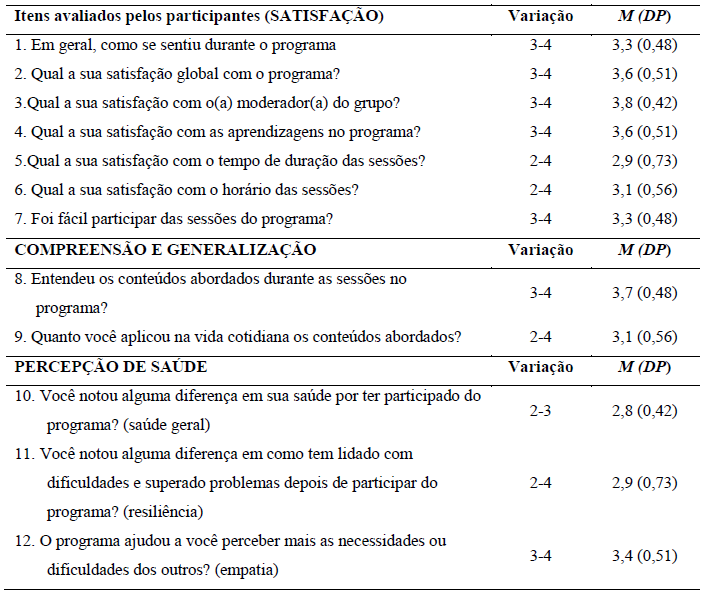

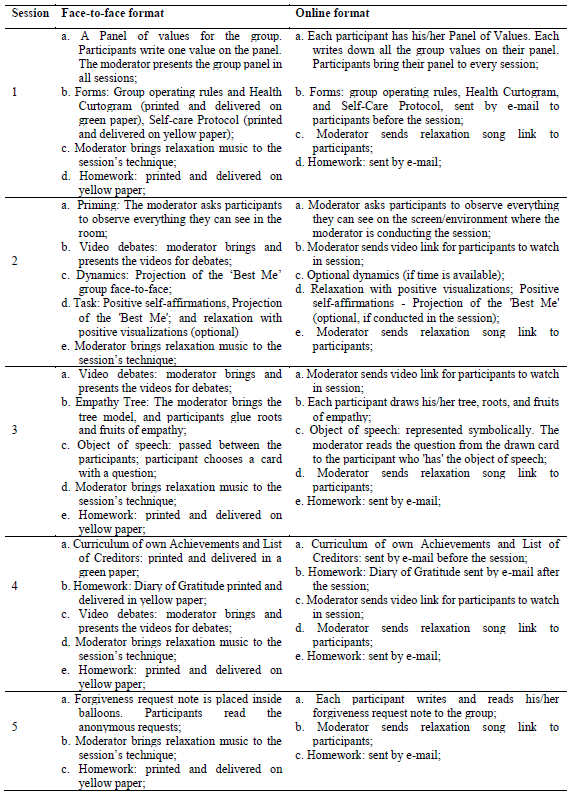

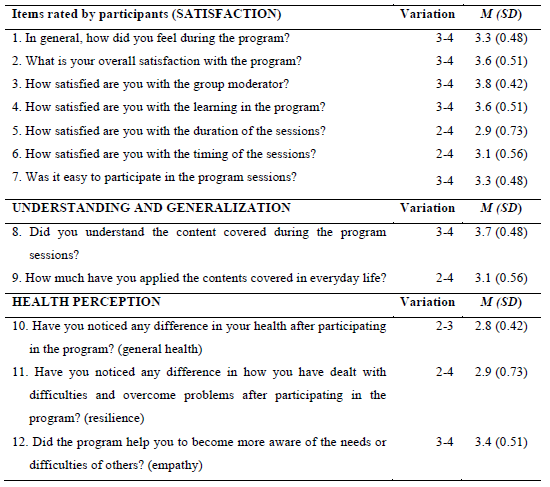

A partir da avaliação de processo, conforme registros do diário de campo do moderador, foram introduzidas mudanças na estrutura, em dinâmicas e materiais utilizados nas sessões, de modo a viabilizar a implementação online, conforme ilustrado na tabela 2.

Tabela 2: Alterações na estrutura do Programa Vem Ser para implementação online

Resultados e discussão

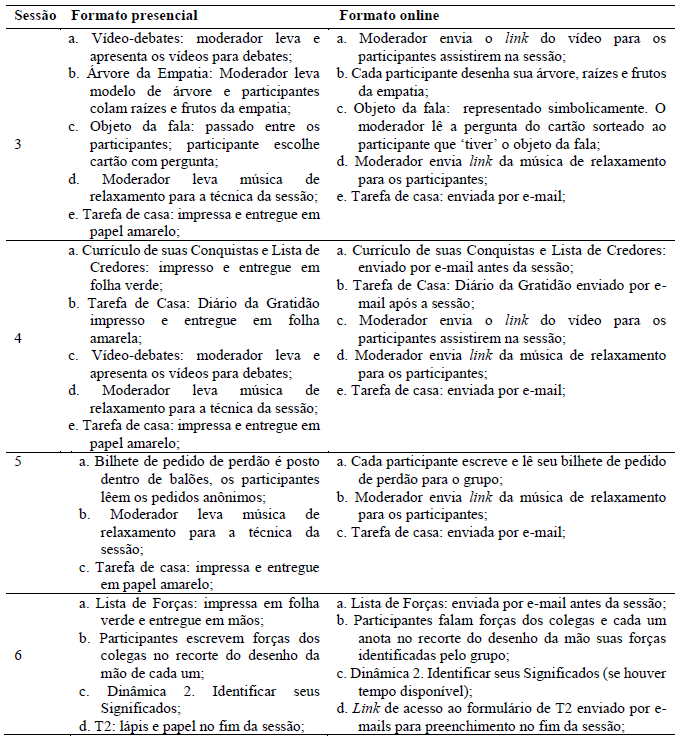

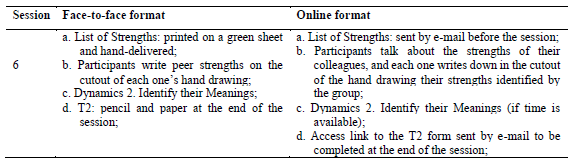

A tabela 3 apresenta variações de escores (entre 1 e 4), médias (M) e desvio padrão (PD), das questões objetivas das avaliações dos participantes quanto à satisfação com o programa e com moderador, compreensão e generalização dos conteúdos abordados no programa e questões de saúde, conforme autorelato dos participantes.

Tabela 3: Resultados das avaliações dos participantes com relação ao programa

A média geral de satisfação dos participantes com o programa foi 3,37 (DP = 0,38), itens de 1-7, com variação de resultados de 2-4 em uma escala de 1 a 4 pontos, a exemplo dos comentários: “O programa em sua versão EAD foi excelente. Funcionou perfeitamente e, a meu ver, poderá ser colocado em prática imediatamente” (participante, 59 anos); “Experiência maravilhosa que me fez refletir sobre coisas práticas do dia-a-dia” (participante, 36 anos); “Gostei muito do programa. Acho que foi um espaço muito rico de debate, na qual pudemos enxergar o outro de forma mais ‘humana’ e tratar assuntos que muitas vezes evitamos pensar, mas que não deixam de ser necessários para o nosso amadurecimento e crescimento pessoal” (participante, 22 anos); “Foi ótimo participar pois o tempo todo notei a melhora nas sessões, poder voltar a momentos que ainda estavam me fazendo mal e entender a necessidade de buscar um tratamento. Iniciei a terapia semana passada, junto com as sessões está me fazendo quase ser outra pessoa, mais leve, menos triste, menos preocupada e ansiosa” (participante, 20 anos).

O item melhor avaliado tem relação à satisfação dos participantes com o moderador de grupo (M = 3,8; DP = 0,42). O item menos bem avaliado foi quanto a satisfação dos participantes com o tempo de duração das sessões (M = 2,9, DP = 0,73), “como sugestão, acredito que sessões em grupo menores otimizariam o tempo e seriam ainda mais produtivas” (participante, 36 anos). Esses resultados seguem padrão já identificado em estudo de viabilidade na versão presencial do programa (Durgante et al., 2019b). Contudo, tendo em vista dados da literatura quanto ao tempo de duração de intervenções nestes moldes (Bolier et al., 2013; Durgante, 2017; Durgante et al., 2019a), em caráter psicoeducativo grupal, com abordagem da Terapia Cognitivo-Comportamental (Neufeld & Rangé, 2017), sugere-se o tempo máximo de duração das sessões de 2 horas, podendo o moderador dividir as atividades das sessões em duas (dois encontros com a mesma temática). Alternativamente, é possível reduzir o número de participantes nos grupos para que todos tenham tempo hábil de expor e compartilhar suas vivências, conforme sugestão de uma participante “sessões com mais tempo de duração ou grupo menor para possibilitar mais espaço de fala” (participante, 32 anos).

Para generalização dos conteúdos, a média foi 3,4 (DP = 0,39) e variações entre 2-4. Os conteúdos utilizados na vida, conforme relato dos participantes, formam: Gratidão, “Utilizei bastante a dinâmica do diário da gratidão, faço diariamente e já sinto melhoras em relação a minha ansiedade” (participante, 22 anos), “Passei a olhar mais para o meu dia a dia, observando e agradecendo pelas pequenas coisas” (participante, 59 anos); Empatia, “Nas relações com minha filha” (participante, 38 anos),“ Passei a observar mais o olhar do outro” (participante, 59 anos), “Um momento que briguei com uma pessoa próxima e quando estava sendo uma pessoa difícil de conviver em casa. Com o exercício da empatia, pude entender os motivos das pessoas para estarem tristes e pensando nos conflitos que tive com as mesmas me fez entender que o meu comportamento estava causando aquilo e sendo ruim, eu estava botando uma carga nas pessoas e exigindo perfeição. Foi muito bom porque o relacionamento com elas mudou totalmente” (participante, 20 anos); Perdão e autoperdão, “Refleti sobre coisas no meu passado que precisava comungar comigo mesma em me perdoar para encerrá-las” (participante, 59 anos); “Auto-perdão, entender minhas limitações e que não preciso agradar a todos” (participante, 32 anos). Além de sugestões sobre aumentar o tempo de duração das sessões, ou reduzir o número de participantes, houve sugestão de incluir mais dinâmicas de grupo,“Amei o programa; gostaria que fosse utilizado para reflexão mais dinâmicas de grupo” (participante, 57 anos).

Barreiras e facilitadores identificados no processo de implementação

Enquanto barreiras identificadas no processo de implementação, no eixo Características dos indivíduos envolvidos (Characteristics of individuals), foi possível identificar disputa por ‘espaço’ e reconhecimento de conhecimento específico por parte de um participante, o que dificultou o andamento de algumas atividades das sessões, a exemplo da sessão 2 (tema: Otimismo). Neste caso, houve contestação e não aceitação da definição operacional sobre as forças trabalhadas em cada sessão com base na literatura empírica da área, crítica sobre a frase quebra-gelo da sessão 1 (tema: valores e autocuidado) e intervenções que menosprezavam a importância dos conteúdos e dinâmicas abordadas nas sessões. Isso tudo prolongou debates sobre conceitos e sobre o modelo teórico utilizado, o que ocasionou demora/atraso na conclusão das sessões. Foi possível detectar discrepância e choque paradigmático entre o modelo biomédico-curativo-hospitalocêntrico de produção de saúde e o modelo de promoção de saúde adotado no Programa Vem Ser, com base na Psicologia Positiva e prisma de Saúde Pública–Saúde Coletiva (Campos, 2000), o que pode ter ocasionado tensão e resistência por parte deste participante em seus questionamentos e reflexões (Other personal attributes). Também houve resistência por parte deste mesmo participante para respeitar o tempo de tolerância de atraso no começo das sessões, critério este estabelecido pelos membros do grupo colaborativamente na sessão 1, como norma para o bom funcionamento de trabalhos grupais (Neufeld & Rangé, 2017). Este impasse foi mitigado a partir da sessão 3, quando não foi permitida a entrada do participante na sessão após ter excedido o tempo de tolerância de atraso, pela terceira vez consecutiva.

Por outro lado, com relação ao eixo ‘Contexto Interno’ de implementação (Inner setting), quanto ao critério Networks and communications, foi possível observar fluidez e coesão grupal para a disseminação de informações através de redes (grupos de WhatsApp e e-mail institucional), o que facilitou a organização e processo de implementação, uma vez que links para acesso de vídeos e materiais eram enviados durante as sessão e redirecionados simultaneamente por colegas aos demais participantes que estavam utilizando celulares para acesso às sessões. Ter um profissional de referência como ponto de contato para as divulgações e também um profissional que auxiliou com contatos aos membros da equipe de gestão em saúde durante as sessões, acelerou a velocidade da comunicação e repasse de informações. Neste sentido, pesquisas apontam que a relação estabelecida entre membros em instituições, em termos colaborativos e de cooperação, se torna mais importante que atributos individuais (Wierenga et al., 2013), o que auxilia com senso de equipe/comunidade e facilita o processo de implementação de intervenções de saúde nestes contextos. Portanto, fortalecer senso coletivo e coesão grupal podem ser considerados facilitadores para o processo de implementação de intervenções para promoção de saúde em contextos organizacionais e de trabalho.

Com relação aos custos, eixo: Intervention characteristics; critério: Cost (ano base: 2020), vale lembrar que esta foi a primeira proposta de intervenção online com o programa após o início da pandemia e, por este motivo, houve investimentos considerados emergenciais para aquisição de materiais. Houve investimento financeiro para custear a mensalidade de plataforma online e materiais para uso nas sessões. No entanto, estes servirão para futuras pesquisas com o programa e subsequente implementação online em diferentes grupos. Portanto, os custos associados à implementação podem ser interpretados como investimentos que darão suporte à continuidade das pesquisas e assistência à população de modo geral. Esperamos que estas experiências possam auxiliar na otimização de investimentos em pesquisas e práticas de saúde diante da gravidade da situação pandêmica em que o país se encontra.

Considerações Finais

Este é o primeiro estudo nacional que tem como base dois protocolos internacionalmente reconhecidos para adaptação de intervenções para diferentes contextos e populações. O uso de protocolos guia para adaptação de intervenções para outros contextos e culturas é prática fundamental, porém, pouco observada em pesquisas de implementação (Damschroder et al., 2009; Hwang, 2009). Muitas intervenções com potencial inovador, as quais poderiam servir como fortes recursos para saúde, falham em sua utilidade clínica devido, principalmente, à baixa qualidade metodológica e ausência de emprego de critérios e estratégias cientificamente fundamentadas para adaptação das intervenções para outros contextos e populações.

Vale lembrar que, existem diferentes protocolos para adaptação de intervenções e cabe ao pesquisador identificar qual é mais indicado para sua proposta, contexto, cultura, momento histórico-social e população alvo, cuja intervenção é direcionada (Stoner et al., 2020). A partir da análise de custos, é possível sugerirmos possibilidades para otimização de recursos associados à implementação. Por se tratar de intervenção online, custos com deslocamento de equipe e dos participantes, aquisição de materiais impressos como protocolo de avaliação, fichas das sessões e para tarefas de casa, foram inexistentes, o que configura esta modalidade de intervenção do Programa Vem Ser como sendo de baixo custo. Este critério é pouco avaliado e relatado, uma vez que está associado à eficiência e, muitas vezes, o foco das avaliações são voltados a critérios de eficácia e efetividade das intervenções.

Como limitações deste estudo ressaltamos não ter sido possível avaliar alguns critérios do CFIR, como Cosmopolitanism, Peer pressure, External policies and incentives, do eixo ‘Contexto Externo’; Individual identification with organization, Individual stage of change, Self-efficacy, do eixo ‘Características dos Indivíduos’. Estes dados permanecem para serem investigados em futuros estudos de viabilidade da intervenção na sua versão online. Também há especificidade do contexto no qual a intervenção foi adaptada, por se tratar de uma associação de funcionários aposentados, o que inibe a possibilidade de generalização dos resultados obtidos para demais contextos. Isso nos direciona para o seguimento das pesquisas com a intervenção no formato online, incluindo diferentes amostras, grupo controle e diferentes moderadores de grupos, assim como verificação de critérios de eficácia para a promoção de saúde de modo mais amplo.

Contudo, através do rigor e sistematização utilizada no processo de adaptação do Programa Vem Ser para versão online descrita neste artigo, é esperado que este esforço possa favorecer novas práticas interventivas em contexto nacional, tendo em vista a cientificidade necessária para adaptações e ajustes de intervenções e maior probabilidade de eficácia das mesmas em contextos e para populações diversas.

Referências:

Bolier, L., Haverman, M., Westerhof, G. J., Riper, H., Smit, F., & Bohlmeijer, E. (2013). Positive psychology interventions: A meta-analysis of randomized controlled studies. BMC Public Health, 13, 119. doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-119

Campos, G. W. de S. (2000). Saúde pública e saúde coletiva: campo e núcleo de saberes e práticas. Ciência & Saúde Coletiva, 5(2), 219–230. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1413-81232000000200002

Cohn, M. A., & Fredrickson, B. L. (2010). In search of durable positive psychology interventions: Predictors and consequences of long-term positive behavior change. Journal of Positive Psychology, 5(5), 355-366. https://doi.org/10.1080/17439760.2010.508883

Damschroder, L. J., Aron, D. C., Keith, R. E., Kirsh, S. R., Alexander, J. A., & Lowery, J. C. (2009). Fostering implementation of health services research findings into practice: a consolidated framework for advancing implementation science. Implementation Science, 4(1), 50. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-4-50

Driggin, E., Madhavan, M. V., Bikdeli, B., Chuich, T., Laracy, J., Bondi-Zoccai, G., Brown, T. S., Der Nigoghossian, C., Zidar, D. A., Haythe, J., Brodie, D., Beckman, J. A., Kirtane, A. J., Stone, G. W., Krumholz, H. M., & Parikh, S. A. (2020). Cardiovascular Considerations for Patients, Health Care Workers, and Health Systems during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic. Journal of the American College of Cardiology, 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jacc.2020.03.031

Duan, Y., Zhu, H.-L., & Zhou, C. (2020). Advance of promising targets and agents against 2019-nCoV in China. Drug Discovery Today, 00(00), 10-12. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.drudis.2020.02.011

Durgante, H. B. (2017). Qualidade metodológica de programas de intervenção baseados em fortalezas na América Latina: uma revisão sistemática da literatura. Contextos Clínicos, 10(1), 2-22. https://doi.org/10.4013/ctc.2017.101.01

Durgante, H. & Dell’Aglio, D. D. (2019). Multicomponent positive psychology intervention for health promotion of Brazilian retirees: a quasi-experimental study. Psicologia: Reflexão e Critica, 32(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s41155-019-0119-2

Durgante, H., Mezejewski, L. W., Sá, C. N., & Dell’Aglio, D. D. (2019a). Intervenciones psicológicas positivas para adultos mayores en Brasil. Ciencias Psicológicas, 13(1), 106-118. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v13i1.1813

Durgante, H., Naveire, C., & Dell’Aglio, D. (2019b). Psicologia positiva para promoção de saúde em aposentados: estudo de viabilidade. Avances En Psicología Latinoamericana, 37(2), 269-281. https://doi.org/ 10.12804/revistas.urosario.edu.co/apl/a.6375

Durgante, H., Mezejewski, L.W., & Dell’Aglio, D.D. (2020a). Desenvolvimento de um Programa de Psicologia Positiva para promoção de saúde de aposentados. Programa Vem Ser. Em C. H. Giacomoni & F. Scorsolini-Comin (Eds.), Temas especiais em Psicologia Positiva (pp. 188-202). Editora Vozes.

Durgante, H. B., Tomasi, L. M. B., Pedroso de Lima, M. M., & Dell’Aglio, D. D. (2020b). Long-term effects and impact of a positive psychology intervention for Brazilian retirees. Current Psychology, 41, 1504-1515. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12144-020-00683-7

Ebert, D. D., Cuijpers, P., Muñoz, R. F., & Baumeister, H. (2017). Prevention of mental health disorders using internet- and mobile-based interventions: A narrative review and recommendations for future research. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8(AUG). https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00116

Firth, J., Torous, J., Nicholas, J., Carney, R., Pratap, A., Rosenbaum, S., & Sarris, J. (2017). The efficacy of smartphone-based mental health interventions for depressive symptoms: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. World Psychiatry, 16(3), 287-298. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20472

Huang, C., Wang, Y., Li, X., Ren, L., Zhao, J., Hu, Y., Zhang, L., Fan, G., Xu, J., Gu, X., Cheng, Z., Yu, T., Xia, J., Wei, Y., Wu, W., Xie, X., Yin, W., Li, H., Liu, M., Xiao, Y., … Cao, B. (2020). Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. The Lancet, 395(10223), 497-506. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5

Hwang, W. C. (2009). The Formative Method for Adapting Psychotherapy (FMAP): A community-based developmental approach to culturally adapting therapy. Prof Professional Psychology Research and Practice, 40(4), 369-377. https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/20625458/

Knapp, P. & Beck, A. T.

(2008). Cognitive therapy: foundations, conceptual

models,applications and research. Revista Brasileira

de Psiquiatria, 30(Suppl II), 54-64.

Magyar-Moe, J. L., Owens, R. L., & Conoley, C. W. (2015). Positive Psychological Interventions in Counseling: What Every Counseling Psychologist Should Know. The Counseling Psychologist, 43(4).

Marasca, A. R., Yates, D. B., Schneider, A. M. de A., Feijó, L. P., & Bandeira, D. R. (2020). Avaliação Psicológica On-line: considerações a partir da pandemia do novo coronavírus (Covid-19) para a prática e o ensino no contexto à distância. Revista Estudos Em Psicologia (Campinas), Pré-print, 1-24. https://doi.org/10.1590/SciELOPreprints.492

Mouton, A. & Cloes, M. (2013). Web-based interventions to promote physical activity by older adults: promising perspectives for a public health challenge. Arch Public Health, 71(16). https://doi.org/10.1186/0778-7367-71-16

Neufeld, C. B. & Rangé, B. P. (2017). Terapia cognitivo-comportamental em grupos: das evidências à prática. Artmed.

Nikrahan, G. R., Suarez, L., Asgari, K., Beach, S. R., Celano, C. M., Kalantari, M., Abedi, M. R., Etesampour, A., Abbas, R., & Huffman, J. C. (2016). Positive Psychology interventions for patients with heart disease: a preliminary randomized trial. Psychosomatics, 57(4), 348-358. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psym.2016.03.003

Northouse, L., Schafenacker, A., Barr, K. L. C., Katapodi, M., Yoon, H., Brittain, K., Song, L., Ronis, D. L., An, L. (2014). A Tailored Web-Based Psychoeducational Intervention for Cancer Patients and Their Family Caregivers. Cancer Nursing, 37(5), 321-330. https://doi.org/10.1097/ncc.0000000000000159

Proyer, R. T., Gander, F., Wellenzohn, S., & Ruch, W. (2014). Positive psychology interventions in people aged 50-79 years: long-term effects of placebo-controlled online interventions on well-being and depression. Aging and Mental Health, 18(8), 997-1005. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2014.899978

Reppold, C. T., Gurgel, L. G., & Schiavon, C. C. (2015). Research in positive psychology: a systematic literature review. Psico USF, 20(2), 275-285.

Richard, E., Moll van Charante, E. P., Hoevenaar-Blom, M. P., Coley, N., Barbera, M., Van der Groep, A., Meiller, Y., Mangialasche, F., Beishuizen, C. B., Jongstra, S., Van Middelaar, T., Van Wanrooij, L. L., Ngandu, T., Guillemont, J., Andrieu, S., Brayne, C., Kivipelto, M., Soininen, H., Van Gool, W. A. (2019). Healthy ageing through internet counselling in the elderly (HATICE): a multinational, randomised controlled trial. The Lancet Digital Health, 1(8), e424-e434. https://doi.org/10.1016/S2589-7500(19)30153-0

Rogers, M. A. M., Lemmen, K., Kramer, R., Mann, J., & Chopra, V. (2017). Internet-delivered health interventions that work: Systematic review of meta-analyses and evaluation of website availability. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 19(3), 1-28. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7111

Saldaña, J. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Sage

Sin, N. L. & Lyubomirsky, S. (2009). Enhancing well-being and alleviating depressive symptoms with positive psychology interventions: a practice-friendly meta-analysis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 65(5), 467-487. https://doi.org/10.1002/jclp.20593

Spina, S., Marrazzo, F., Migliari, M., Stucchi, R., Sforza, A., & Fumagalli, R. (2020). The response of Milan’s Emergency Medical System to the COVID-19 outbreak in Italy. The Lancet, 395(10227), e49-e50. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30493-1

Stoner, C. R., Chandra, M., Bertrand, E., Du, B., Durgante, H., Klaptocz, J., Krishna, M., Lakshminarayanan, M,, Mkenda, S., Mograbi, D. C., Orrell, M., Paddick, S-M., Vaitheswaran, S., Spector, A. (2020). A New Approach for Developing “Implementation Plans” for Cognitive Stimulation Therapy (CST) in Low and Middle-Income Countries: Results From the CST-International Study. Frontiers in Public Health, 8(July), 1–11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2020.00342

Watkins, J. (2020). Preventing a covid-19 pandemic. The BMJ, 368. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.m810

Welch, V., Petkovic, J., Pardo Pardo, J., Rader, T., & Tugwell, P. (2016). Interactive social media interventions to promote health equity: An overview of reviews. Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada, 36(4), 63-75. https://doi.org/10.24095/hpcdp.36.4.01

Wierenga, D., Engbers, L. H., Van Empelen, P., Duijts, S., Hildebrandt, V. H., & Van Mechelen, W. (2013). What is actually measured in process evaluations for worksite health promotion programs: A systematic review. BMC Public Health, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2458-13-1190

World Health Organization. (2020a). Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19 - 11 March 2020. https://www.who.int/director-general/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19-26-march-2021

World Health Organization. (2020b). Mental health and psychosocial considerations during COVID-19 outbreak. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/mental-health-considerations.pdf

Como citar: Durgante, H. B. & Dell’Aglio, D. D. (2022). Adaptação para implementação online de uma intervenção em Psicologia Positiva para a promoção de saúde. Ciencias Psicológicas, 16(2), e-2250. https://doi.org/10.22235/cp.v16i2.2250

Participação dos autores: Participação dos autores: a) Planejamento e concepção do trabalho; b) Coleta de dados; c) Análise e interpretação de dados; d) Redação do manuscrito; e) Revisão crítica do manuscrito.

H. B. D. contribuiu em a, b, c, d, e; D. D. DA. em a, c, e.

Editora científica responsável: Dra. Cecilia Cracco.

Ciencias Psicológicas v16n2

julho-dezembro 2022

10.22235/cp.v16i2.2250

Ciencias Psicológicas, v16n2

July-December

10.22235/cp.v16i2.2250

Original Articles

Adaptation for online implementation of a Positive Psychology intervention for health promotion

Adaptação para implementação online de uma intervenção em Psicologia Positiva para a promoção de saúde

Adaptación para la implementación online de una intervención en Psicología Positiva para la promoción de la salud

Helen Bedinoto Durgante1, ORCID 0000-0002-2044-6865

Débora Dalbosco Dell’Aglio2, ORCID 0000-0003-0149-6450

1 Universidade Federal de Pelotas, Brazil, [email protected]

2 Universidade La Salle and Universidade Federal do Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil

Abstract:

This study describes the online adaptation of a Positive Psychology intervention for health promotion. The methodological guidelines used were The Formative Method for Adapting Psychotherapy and the Consolidated Framework for Implementation, based on: characteristics of the intervention; of the individuals; internal and external contexts; implementation process. The intervention consisted of 6 online group sessions, with 10 staff members from the health management team of a retiree association in RS/Brazil, mean age 43.6 years (SD = 15.86). An evaluation questionnaire was completed at the end of the activities and descriptive statistics revealed participants' satisfaction with the intervention and with the moderator, as well as generalization of the contents. Changes were suggested specially to increase the duration of the sessions. We suggest the systematization the processes used in this study to support research on the implementation and adaptation of online interventions for different contexts and populations.

Keywords: positive psychology; health promotion; online adaptation.

Resumo:

Este estudo descreve a adaptação online de uma intervenção em Psicologia Positiva para promoção de saúde. Como diretriz metodológica, utilizou-se o The Formative Method for Adapting Psychotherapy e o Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research, nos eixos: características da intervenção; dos indivíduos; contextos interno e externo; processo de implementação. A intervenção consistiu em 6 encontros grupais online, com 10 integrantes da equipe de gestão em saúde de uma associação de aposentados do RS, Brasil, média de idade 43,6 anos (DP = 15,86). Um questionário de avaliação foi preenchido ao final das atividades e estatísticas descritivas revelaram satisfação dos participantes com a intervenção e com o moderador, assim como generalização dos conteúdos. Foram sugeridas alterações, especialmente aumento da carga horária das sessões. Sugere-se a sistematização dos processos utilizados neste estudo para embasar pesquisas de implementação e adaptação de intervenções online para diferentes contextos e público-alvo.

Palavras-chave: psicologia positiva; promoção de saúde; adaptação online.

Resumen:

Este estudio describe la adaptación online de una intervención en Psicología Positiva para la promoción de la salud. Como guía metodológico se utilizó el The Formative Method for Adapting Psychotherapy y Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research en: características de la intervención; de individuos; contextos internos y externos; proceso de implementación. La intervención consistió en 6 reuniones grupales con 10 miembros del equipo de gestión de salud de una asociación de jubilados en RS (Brasil), con una edad promedio de 43.6 años (DE = 15.86). Se completó un cuestionario de evaluación al final de las actividades y las estadísticas descriptivas revelaron la satisfacción de los participantes con la intervención, con el moderador y generalización de los contenidos. Se sugirieron cambios, especialmente aumento en la carga de trabajo de las sesiones. Sugerimos sistematizar los procesos utilizados en este estudio para apoyar la investigación sobre la implementación y adaptación de intervenciones para diferentes contextos y públicos.

Palabras clave: psicología positiva; promoción de la salud; adaptación online.

Received: 27/08/2020

Accepted: 14/06/2022

The year 2020 was a turning point in human history after the World Health Organization (WHO, 2020a, 2020b) announced a pandemic as a public health emergency. First detected in Wuhan, China, COVID-19 is a severe acute respiratory syndrome caused by the new Betacoronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV2), called new coronavirus (Huang et al., 2020; Spina et al., 2020). Besides the rapid progression to severe cases of the disease, another difference of COVID-19 vis-à-vis other infectious conditions is the high contagion rate between individuals/groups, or prolonged contagion after the exposure to virus-contaminated surfaces (Duan et al., 2020). Although the final death rates from COVID-19 cannot yet be ascertained due to the rapid progression of the disease in several countries, case fatality rates have been higher than previous crises of the 21st century caused by SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV coronaviruses. Currently, cases have been underreported due to the shortage of samples, reagents and equipment for testing and diagnostic establishment worldwide (Driggin et al., 2020; Watkins, 2020).

Concerning individuals’ mental and physical health due to the imminent risk of infection by the virus and physical distancing/isolation and break in the life routine, we highlight factors intervening in the pandemic that trigger uncertainty about the future and psychological crises. Moreover, there is a low perception of control and insecurity regarding the support provided by social institutions to mitigate socioeconomic problems arising from job losses, reduction or non-existence of jobs and income, in the case of informal workers, service providers, and companies. In addition, the lack of public policies and investments to meet the basic needs to face the pandemic is a stressor attaching risks to people’s mental health. We also witness a lack of managers’ preparedness and the inconsistent provision of information on safety procedures to the population by public authority levels and bodies, which tends to generate even more anxiogenic and depressogenic symptoms for the population and, mainly, those included in a risk group (WHO, 2020a, 2020b).

Health promotion and disease prevention strategies are the primary interventions suggested addressing such complex mental health issues. They serve to treat pre-clinical, underdiagnosed cases or clinical symptoms and prevent the recurrence of health problems and as a measure to compile evidence to guide and support the elaboration of public policies and sustainability of the health network (WHO, 2020a, 2020b).

Health promotion interventions have been implemented in several countries in online/virtual format (also called eHealth/mHealth interventions) for greater capillarity of access for risk groups due to their low cost (Welch et al., 2016) and because they are more effective for behavioral changes, given their interactive nature, when compared to motivational or purely informative websites (Mouton & Cloes, 2013).

Some examples of interventions implemented online to promote the health of adults and older adults are geared to informal caregivers (family members) that include professional and social support components, instructions for behavioral change, and problem-solving (Richard et al., 2019); cancer patients and their caregivers (Northouse et al., 2014); self-directed interventions for several mental health conditions (post-traumatic stress, depression, anxiety, and phobia) and physical health (diet and physical activity) (Rogers et al., 2017). Among the most significant benefits to mental health identified after participating in online interventions, review data indicate a lower depressive level in interventions by apps focused on health promotion than cognitive training apps (Firth et al., 2017) and gains in the prevention of depression (Ebert et al., 2017).

In Brazil, some regulations are also in force to regulate the work of psychologists through information and communication technologies (ICTs) for remote access of intervention participants, such as Resolution No. 11, of May 11, 2018, which regulates the provision of psychological services performed through ICTs. Resolution No. 11/2018 regulates the Psychological Assessment practice. Technical Note No. 07/2019 guides on the use of psychological tests in services performed through ICTs. Resolution Nº 04, of March 26, 2020, provides for the regulation of psychological services provided through ICTs during the COVID-19 pandemic and assists in the registration of psychologists for online services (Marasca et al., 2020).

Thus, at this time of grave need, it is impossible to act with group face-to-face interventions due to the restrictive measures in several countries to promote physical distance from the general population and contain COVID-19 transmission. Whereas there is no defined deadline for the normalization of standard procedures for assistance and provision of health services; whereas it is essential to adapt services and interventions for health promotion, based on the use of ICTs for distance/remote access. This study aims to describe the process of adapting an intervention in Positive Psychology for health promotion with online implementation Vem Ser Program.

Description of the intervention: The Vem Ser Program

Positive Psychological Interventions (PPIs) have been implemented worldwide to promote physical and mental health. This intervention model includes approaches to positive subjective experiences, traits that are strengths, which constitutes character virtues, and positive institutional contexts to favor better psychological and health functioning (Durgante, 2017; Magyar-Moe et al., 2015; Proyer et al., 2014; Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009).

PPIs have been effective in improving well-being and quality of life indicators in clinically and non-clinically diagnosed individuals (Boiler et al., 2013; Durgante & Dell’Aglio, 2019; Nikrahan et al., 2016), providing better response to treatments and rehabilitation (Reppold et al., 2015), better recovery from adverse psychophysiological effects, such as cardiovascular reactivity, inflammatory processes, and immunosuppression, which tend to be aggravated in stressing situations (Cohn & Fredrickson, 2010).

Thus, the Vem Ser Program was developed based on the scientific literature on group PPIs (Sin & Lyubomirsky, 2009) and Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (Knapp & Beck, 2008). The program consists of 6 weekly (2 h each) face-to-face group sessions and aims to intervene in the following forces: values and self-care/prudence, optimism, empathy, gratitude, forgiveness, the meaning of life, and work. The initial version of the program, implemented face-to-face, underwent a pilot study (Durgante et al., 2020a), a feasibility study (Durgante et al., 2019b), and an efficacy trial (Durgante & Dell’Aglio, 2019), with a sample of more than a hundred southern Brazilian retirees. Quantitative results indicated the main effects of the program for improved indicators of life satisfaction, resilience, symptoms of perceived stress, depression, and anxiety in the intervention group, besides interaction effects for improved optimism, empathy, symptoms of depression and anxiety in the experimental group compared to the control group. The effects and impacts on life satisfaction, depression, and anxiety symptoms remained three months after the end of the program (Durgante et al., 2020b). However, given the current pandemic situation and the need to adapt services remotely for all populations and health care levels, the online version of the program was adapted to conduct interventions aimed at the general public (Durgante et al., 2019a).

Methods

Design

A mixed qualitative-quantitative longitudinal study was developed to implement and evaluate the online version of the Vem Ser Program, with pre (T1- in the week before the onset of the intervention) and post-intervention (T2- in the week of the end of sessions). This was based on the Formative Method for Adapting Psychotherapy (Hwang, 2009), in five stages: I. Generating knowledge and collaboration with stakeholders; II. Integrating the information generated with theory and empirical and clinical knowledge; III. Reviewing and initiating the intervention in the adapted format with the stakeholders/target audience; IV. Conducting preliminary tests with the adapted version of the intervention; V. Finalizing the culturally adapted version of the intervention. We employed the Consolidated Framework for Implementation Research (CFIR) (Damschroder et al., 2009), as a methodological guideline used to consider the necessary adjustments/adequacies to adapt the intervention to the new health context/organization/institution and online format. It considers 29 criteria subdivided into the following assessment axes: intervention characteristics; internal and external contexts; characteristics of the individuals involved; implementation process. We evaluated quantitative data by descriptive statistics and qualitative data by the Thematic Content Analysis (Saldaña, 2009), with the axes and criteria established in the CFIR (Damschroder et al., 2009).

Participants

Ten health management team members of an association of retirees in the State of Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil, of which nine were females, participated by convenience and voluntarily. The sample consisted of a nurse, a physiotherapist, a biomedical professional, social workers, Social Work interns, a doctor, and a social director, per previously defined inclusion criteria:

1) Be a professional in health/education/assistance; 2) Be available to participate in program sessions and evaluations; 3) Have access to the internet, computer/cell phone/tablet, or any device that allows access to the program sessions online. The mean age of the participants was 43.6 years (SD = 15.86), with a minimum of 20 and a maximum of 62 years. The mean total working time in the functional/working life was 15.4 years (SD = 13.5) with a variation of 01-34 years of service, with a mean of 2.48 years in the current position (SD = 2.73). Six participants were married or in a common-law marriage, four had children, and two lived alone. Three participants were retired (due to age, contribution time, and particular case), and one was preparing for retirement. Three participants were caregivers of people they were close to. Nine participants reported experiencing some significant/impacting life event in the last year, and nine identified at least one source (person/institution) as a support network. Six participants had some type of belief or religion; five reported having chronic physical or mental health problems (anxiety with and without panic attacks, depression, stomach pain, cancer). Three participants reported that they were currently grieving a personal loss. All participants had some type of leisure activity, including reading/studying (4), engaging in physical activities (4) (walking (1), Pilates (1), gym (1), running (1)), watching movies/series (3), staying with family (2), traveling (2), dancing (1), volunteer work (1), watching decorating programs (1) listening to music (1), going to the movies (1), going out with friends (1), walking outdoors (1), eating (1).

Tools

We employed the following tools:

Sociodemographic data questionnaire (T1): Containing questions about age, sex, work aspects, schooling level, and family composition.

Program Evaluation Sheet (T2): Containing 12 objective self-reporting questions with answers ranging from 1-dissatisfied to 4-very satisfied, consisting of 6 questions that assess satisfaction with the program, the moderator, the schedule, the duration of the sessions, and the lessons learned from the program; 2 questions about clarity and understanding of the contents covered and 4 questions about generalization (application in life) of the contents covered in the program. Moreover, the instrument includes two descriptive questions asking for examples of program content used and suggestions/feedback for program improvements (Durgante et al., 2019b).

Moderator’s field diary: Used for records during and at the end of the sessions, based on the CRIF protocol’s criteria (Damschroder et al., 2009) for methodological quality in evaluating the program implementation process.

Procedures

The Ethics Committee of the Federal University of Rio Grande do Sul-UFRGS approved the research under Opinion N° 4.143.219. Initially, we contacted the management team of the retirees’ association to publicize the program. We adopted a bottom-up perspective based on direct involvement and collaboration with stakeholders at all stages of the research. Three meetings were held (2.30-3 h each) with the management team (N = 5) to make the proposal feasible with the association’s professionals. The different phases of the procedures (phase I, II, III, and IV), which include the preparation of the program and its implementation, results, and data discussion (phase V), are described below.

Phase I: Knowledge generation and collaboration with stakeholders

Based on the Intervention characteristics axis of the CFIR protocol, some questions were debated regarding the following criteria: evidence on the strength and quality of the intervention, with data on studies conducted, results obtained, and presentation of the program implementation manual; discussion about the advantages of implementing the intervention versus any alternative solution (Relative advantage) and about the potential adaptability of the intervention, the proposed activities, dynamics, schedules, approach to the themes for a differentiated target audience (professionals) of the original version of the program (older adults/retired); discussion about the possibility of conducting a study for a small group –directive and health management team– in a controlled environment, including the participants’ perception in the adaptation and implementation of the intervention (Trialability); discussion about the potential of the intervention to impair the institution’s routine work practices and actions necessary for the health management team to participate in the program (Complexity). This criterion relaxed access and in a joint decision with the health management team, the management team opted to allocate work hours/shifts so that professionals could participate in the program without compromising their work tasks. The participants themselves chose the shift and time for implementing the program. As for the Design quality and packaging criterion, we prepared a structured program project containing an introduction on health promotion issues and relevant literature, structure, method, and results. We presented the program manual and briefly discussed with the management team how the program could be implemented with the association.

Phase II: Integrating the information generated with theory and empirical and clinical knowledge

In this phase, Outer setting criteria were discussed with the management team, containing questions about the need for psychological support for the team in the face of growing health demands from the associates and the team, given the pandemic and possible topics to be addressed in the program, relevant to professionals and grounded on scientific literature, such as physical and mental exhaustion, irritability, sleep dysfunction/anxiety, service overload/long working hours, perception of impotence given the current health situation (patient needs and resources).

Regarding the Inner setting, the meetings addressed team issues about how much the intervention was as per the organizational culture (Culture) and Implementation climate since the program could be helpful, supported, and recognized as an input to the mental health of professionals (compatibility) who did not have a structured proposal to promote their health. The need to understand the receptivity and prioritization (relative priority) of the target audience after the program was announced was emphasized to have an idea about the demand for this type of service in this specific context. It is worth mentioning that the management team supported and encouraged the participation of professionals (organization incentives and rewards), which favored the subsequent implementation of the program.

After the initial meetings with the management team, the Characteristics of Individuals axis was perceived with greater knowledge to disseminate the program to the health management team (Knowledge and beliefs about the intervention).

Phase III: Reviewing and initiating the intervention in the adapted format with the stakeholders/target audience

From the axes and criteria evaluated in the initial phases, based on the perception of the management team, we could introduce initial adaptations in the process (Axis: Process, criterion: planning) of selecting participants and topics of interest to the target audience, due to the historical moment of program implementation, when Brazil was one of the world epicenters of the COVID-19 pandemic. The adaptations include systematizing the activities before and during the program for online implementation and reviews and emphasis on topics of interest reported by the health management team. Table 1 presents the changes initially included for the online implementation of the program.

Table 1: Initial changes included for the implementation of the Vem Ser online Program

Phase IV: Conducting preliminary tests with the adapted version of the intervention

After the initial adjustments in the program’s structure, we conducted a group with the adapted version of the Vem Ser Program with the management team to evaluate the functionality of the adapted components of the program and some feasibility criteria as a preliminary assessment of this type of intervention. The online sessions were implemented on six consecutive Wednesdays, starting at 10 am. The mean duration of the sessions was 2.17 h (SD = 0.11). Session 5 (Theme: Forgiveness) was the shortest, lasting 2.08 h, and Session 6 (Theme: Meaning of Life and Work) was the most protracted, lasting 2.37 h , including the assessment of T2. Only one absence was recorded (Session 3: Empathy), which represents 98.3 % of attendance in the group. All participants (N = 10) completed the program and T2.

The outcome indicators evaluated followed the SMART criteria (specific, measurable, attainable, relevant, timely), proposed in the Process axis (reflecting and evaluating) (Damschroder et al., 2009). The demand was satisfactory since we observed a unanimous perception of the need for this type of intervention at this historical moment and specific context by the directive team and the health management team. All team professionals participated in the program voluntarily. A waiting list was prepared for other interested professionals, and the management team manifested interest and requested to offer the program to the association’s members (retired) in the future.

Phase V: Finalizing the culturally adapted version of the intervention

Changes were introduced in the structure, dynamics, and materials used in the sessions based on the process evaluation, per the moderator’s field diary, to enable online implementation, as illustrated in Table 2.

Table 2: Changes in the structure of the Vem Ser Program for online implementation

Results and Discussion

Table 3 shows variations in scores (between 1 and 4), means (M), and standard deviation (SD) of the objective questions of the participants’ evaluations regarding satisfaction with the program and the moderator, understanding, and generalization of the contents covered in the program and health issues, per the participants’ self-report.

Table 3: Results of participant evaluations regarding the program

The overall mean of participants’ satisfaction with the program was 3.37 (SD = 0.38), items from 1-7, with results ranging from 2 to 4 on a scale of 1 to 4 points, as in the comments: “The Distance Learning (DL) version of the program version was excellent. It worked perfectly, and I believe that can be put into practice immediately” (participant, 59 years old). “A wonderful experience that made me reflect on practical everyday things” (participant, 36 years old). “I really enjoyed the program. I think it was a vibrant space for debate, in which could see the other in a more “humane” way and address issues that we often avoid thinking about, but that are still necessary for our maturation and personal growth” (participant, 22 years old). “It was great to participate because I noticed the improvement in the sessions at all times. I could go back to moments still hurting me and understand the need to seek treatment. I started therapy last week, along with the sessions. It is making me almost become someone else: lighter, and less sad, worried and anxious” (participant, 20 years old).

The best-evaluated item relates to the participant’s satisfaction with the group moderator (M = 3.8; SD = 0.42). The least well-rated item was the participant’s satisfaction with the duration of the sessions (M = 2.9; SD = 0.73), “as a suggestion, I believe that smaller group sessions would streamline time and be even more productive” (participant, 36 years old). These results follow a pattern already identified in a feasibility study in the face-to-face version of the program (Durgante et al., 2019b). However, given the literature on the duration of interventions along these lines (Bolier et al., 2013; Durgante, 2017; Durgante et al., 2019a), in a group psychoeducational approach, with Cognitive-Behavioral Therapy (Neufeld & Rangé, 2017) approach, a maximum duration of 2 hours is suggested, and the moderator could divide the activities of the sessions into two (two meetings with the same theme). Alternatively, it is possible to reduce the number of participants in the groups so that all can present and share their experiences, as suggested by one participant... “sessions with a longer duration or smaller group to allow more space for speech” (participant, 32 years old).

The content generalization mean was 3.4 (SD = 0.39), ranging from 2 to 4. The contents used in life, as reported by the participants are: gratitude, “I used the gratitude diary a lot. I do it daily, and I already feel improvements concerning my anxiety” (participant, 22 years old); “I started to look more at my day to day, observing and thanking for all the little things” (participant, 59 years old). Empathy, “In the relationships with my daughter” (participant, 38 years old); “I started to observe the other’s perspective more” (participant, 59 years old); “A time when I fought with a close person and when I was a difficult person to live with at home. With empathy, I could understand people’s reasons for being sad. Thinking about the conflicts I had with them made me understand that my behavior was causing that, and being bad, I was putting a load on people and demanding perfection. It was excellent because the relationship with them totally changed” (participant, 20 years old). Forgiveness and self-forgiveness, “I reflected on things about my past that I needed to share with myself in forgiving myself in order to achieve closure” (participant, 59 years old); “Self-forgiveness, understanding my limitations and that I don’t need to please everyone” (participant, 32 years old). We also had suggestions about increasing the duration of the sessions or reducing the number of participants. People suggested including more group dynamics, “I loved the program; I would like it to be used for more dynamic group reflection” (participant, 57 years old).

Barriers and facilitators identified in the implementation process

As barriers identified in the implementation process, in the Characteristics of individuals axis, we could identify a dispute for ‘space’ and recognition of specific knowledge by a participant, which hindered the progress of some activities in the sessions, as in Session 2 (theme: Optimism). In this case, there was contestation and non-acceptance of the operational definition of the forces worked on in each session based on the empirical literature in the area, criticized Session 1 icebreaking sentence (theme: values and self-care), and some interventions underestimated the importance of contents and dynamics addressed in the sessions, which prolonged debates on concepts and the theoretical model used, which delayed the conclusion of the sessions. We could detect a discrepancy and paradigmatic clash between the biomedical-curative-hospital-centered model of health production and the health promotion model adopted in the Vem Ser Program, based on the Positive Psychology and Public Health-Collective Health prism (Campos, 2000), which may have triggered tension and resistance by this participant in his questions and reflections (other personal attributes). There was also resistance by this same participant to respect the delay tolerance time at the onset of the sessions, a criterion established by the group members collaboratively in Session 1 as a norm for the proper functioning of group work (Neufeld & Rangé, 2017). This impasse was mitigated from Session 3 onwards when the participant was not allowed to enter the session after exceeding the delay tolerance time for the third consecutive time.

On the other hand, regarding the Inner Context axis of implementation (Inner setting), regarding the Networks and communications criterion, we could observe group fluidity and cohesion for the dissemination of information through networks (WhatsApp groups and institutional e-mail), which facilitated the organization and implementation process, since links to access videos and materials were sent during the session and simultaneously redirected by colleagues to other participants who were using cell phones to access the sessions. Having a reference professional as a point of contact for the dissemination and a professional who helped with contacts with the health management team members during the sessions accelerated the speed of communication and information transfer. In this sense, research indicates that the relationship established between members in institutions regarding collaboration and cooperation becomes more important than individual attributes (Wierenga et al., 2013), which helps with a sense of team/community and facilitates the process of implementing health interventions in these settings. Thus, strengthening collective sense and group cohesion can facilitate health promotion interventions in organizational and work contexts.

Regarding costs, axis: Intervention characteristics; criterion: Cost (base year: 2020), we should remember that this was the first online intervention proposal with the program after the onset of the pandemic and, for this reason, we had emergency investments for the acquisition of materials. We had a financial investment to cover the monthly fee for the online platform and materials for use in the sessions. However, these will serve for future research with the program and subsequent online implementation in different groups. Therefore, the costs associated with the implementation can be interpreted as investments that will support the continuity of research and assistance to the population in general. Given the problematic pandemic situation, we hope these experiences can help streamline research and health work investments.

Final considerations

This is the first national study based on two internationally recognized protocols for adapting interventions to different settings and populations. Using guide protocols for adapting interventions to other contexts and cultures is a fundamental practice. However, it has been barely observed in implementation research (Damschroder et al., 2009; Hwang, 2009). Many interventions with innovative potential, which could serve as robust resources for health, fail in their clinical usefulness, mainly due to low methodological quality and lack of use of scientifically based criteria and strategies for adapting interventions to other contexts and populations.